?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic has a profound impact on the everyday lives of people around the world. This includes economic issues, social isolation and anxieties directly related to the coronavirus. Some of these phenomena relate to social disintegration, which in turn has been linked to negative outgroup sentiments. However, the tenuous connection between pandemic developments and international migration processes calls into question whether a link between pandemic concomitants and immigration-related attitudes exists empirically. Arguments based on political cues and media effects even suggest that the widespread focus on the COVID-19 pandemic suppresses the issue salience of immigration and negative immigration sentiments. To test these propositions, we employ data from a newly collected cross-sectional study carried out in November and December 2020 in 11 European countries. We distinguish between general migration-related threats and blaming the pandemic on immigration as outcome variables. The results suggest that pandemic-related concerns increase both threat perceptions and perceptions that immigration is driving the pandemic, but more clearly so for the latter. On the macro level, we find that where the pandemic is more severe, respondents are less likely to blame immigrants. This suggests that a country-level suppression of salience of immigration is indeed taking place.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has strongly affected many countries throughout the world. The effects on individuals have been both direct in the form of infections, hospitalisations and fatalities, but there are also widespread indirect effects: Due to repeated large-scale lockdowns and other restrictive interventions into the everyday lives of virtually everyone, there were significant economic, social and psychological costs for many persons around the world (Bhattacharjee and Acharya Citation2020; Naumann et al. Citation2020; Rossi et al. Citation2020; Shanahan et al. Citation2020). As the pandemic continuously enters new phases, it is likely that these issues also continue to evolve.

The magnitude of these processes suggests that pandemic strains may have a myriad of further attitudinal consequences, an issue that is beginning to receive more and more research attention (Boberg et al. Citation2020; Brubaker Citation2020; Hartman et al. Citation2021; Naumann et al. Citation2020; Politi et al. Citation2021; Wondreys and Mudde Citation2020). As such attitudinal consequences in turn can call into question social cohesion and solidarity between societal groups such as natives and immigrants (Borkowska and Laurence Citation2021; Federico et al. Citation2021; Gandenberger et al. Citation2022; Larsen and Schaeffer Citation2021; Schaeffer and Larsen Citation2022), these issues are of utmost urgency. E.g. for the Danish context, the findings of Larsen and Schaeffer indicate less solidarity with COVID-19 patients who recently immigrated (Larsen and Schaeffer Citation2021). For the Israeli context, Adler and colleagues show that exposure to COVID-19 predicts a lower willingness to aid outgroups that are perceived as related to COVID-19 threats (Adler et al. Citation2022). However, there are relatively few investigations into ethnic, racial or migration-related issues in conjunction with COVID-19 in Europe (Drouhot et al. Citation2021; Esses and Hamilton Citation2021; Fernández-i-Marín et al. Citation2021; Hartman et al. Citation2021; Larsen and Schaeffer Citation2021; Reeskens et al. Citation2021) with ambivalent results regarding the question whether COVID-19 has an influence on migration-related attitudes: Some studies on specific immigrant groups or that were conducted during the very early phase of the pandemic tend to imply no such relationship (Drouhot et al. Citation2021; Fernández-i-Marín et al. Citation2021) in contrast to findings based on data produced at later stages. A main focus of the literature so far has documented anti-Asian racism and discrimination in the US (Chen, Trinh, and Yang Citation2020; Schild et al. Citation2020; Wu, Qian, and Wilkes Citation2021) and elsewhere (Dollmann and Kogan Citation2021; Wang et al. Citation2021; Zagefka Citation2021), including xenophobia within China against Wuhan residents (She et al. Citation2022). However, there is further experimental evidence for similar dynamics for other groups, for example, Italian citizens in Italy in comparison to British citizens (Van Assche et al. Citation2020). Comparative research into COVID-19 and immigration attitudes is still scarce. Our contribution seeks to work towards closing this gap by focusing on attitudes towards immigration in Europe.

Employing unique cross-sectional data collected during the end of 2020 in 11 countries, we can approach this issue in a comparative manner. On the individual level, our primary theoretical arguments are focused on disintegration theory (Anhut and Heitmeyer Citation2000; Heitmeyer and Anhut Citation2008), which posits that a lack of social integration into various pertinent societal contexts can lead to negative outgroup sentiments. As we will show, the COVID-19 pandemic arguably had several such disintegrative effects. On the country level, our primary interest lies in investigating the relationship between the country’s pandemic extent and individual migration-related attitudes. Conventional theories of threat, conflict and other mechanisms based on scapegoating (Blalock Citation1967; Blumer Citation1958; Ceobanu and Escandell Citation2010) would suggest more negative attitudes towards immigrants where the pandemic is severe. However, we will argue that the weak link between COVID-19 and immigration and the pervasive dominance of COVID-19 as a public media issue can lead to the opposite relationship (Dennison and Geddes Citation2020): The pandemic appears to ‘crowd out’ the migration issue from mass media coverage and also from the broader public attention and individual-level opinion, which implies that a more severe situation regarding COVID-19 at the macro level is associated with less pronounced immigration concerns at the micro level.

We will approach these issues by looking at two outcome measures in our analyses: A general measure of perceived immigrant threat that is unrelated to the pandemic, and a specific item regarding immigration being a driver of the pandemic. Through this comparison we will get additional insights into how factors related to the pandemic are linked to attitudes towards immigration when these attitudes are (not) related to the pandemic itself.

Theoretical framework and state of the art

The pandemic continues to have a deep reach into the daily lives of many people, introducing economic but also social constraints on individual everyday routines and perspectives throughout the world. Therefore, we need to start with a theory that systematically specifies such constraints and the potential attitudinal consequences of them. The so-called disintegration theorem (Anhut and Heitmeyer Citation2000, Citation2009; Heitmeyer and Anhut Citation2008) appears particularly suited to the current pandemic developments, because it describes in detail the several types of social disintegration that are primary drivers of a variety of negative intergroup sentiments. This conceptual framework, therefore, allows us to approach diverse aspects of the pandemic in a more direct way than would be possible via more general conventional approaches such as self-interest or identity-related approaches (Ceobanu and Escandell Citation2010).

The primary domains of disintegration refer to (I) socio-economic, (II) political and (III) emotional integration processes. Socio-economic integration refers to an individual’s participation in the wealth of a society, whereas political integration refers to participation in the democratic political process. Finally, emotional integration can be seen as the establishment and maintenance of meaningful social relationships which entail socio-emotional support. It is therefore a very broad conceptualisation that covers a large part of Weberian Vergesellschaftung (socio-economic and political integration) and Vergemeinschaftung (emotional integration) (Anhut and Heitmeyer Citation2000, 47).

For each of these three domains, the authors diagnose a secular macro-level process of diminished societal integration capacities: First, long-term economic polarisation processes result in a structural crisis which threatens socio-economic integration. Second, the diminished capability of governments to counter these economic polarisations results in a regulatory crisis, which in turn threatens political integration by fostering apoliticism. Finally, starting from the Durkheimian concept of Anomie (Durkheim Citation2005), ambivalent processes of individualisation that weaken the social fabric of a society (Teymoori, Bastian, and Jetten Citation2017) and threaten traditional sources of integration also are at the core of these developments (Anhut and Heitmeyer Citation2000; Bohle et al. Citation1997). Less stable family ties, more occupational and residential mobility and the waning relevance of public associations such as clubs and labour unions exemplify these atomising processes. This diagnosis can be related to Putnam’s assertions on a purported decline of social capital in the United States (Putnam Citation2000). In sum, these developments call into question many traditional sources of integration. One result is an individualisation of economic and social risks, and there is a risk for a decline of institutions of civil society (Anhut and Heitmeyer Citation2000; Beck Citation1986).

As noted above, these macro-level processes threaten individual integration: First, for the economic dimension, socio-economic status differences and financial distress are most strongly affected by economic polarisation and widening inequalities. Second, political disintegration in the form of low government trust, low political interest and similar aspects of non-participation can be seen as a direct consequence of dwindling regulatory capacities and of political polarisations. Finally, the aforementioned decline of many traditional sources of emotional integration can increase individual risks for loneliness, alienation, low generalised trust and similar aspects. These aspects of disintegration in turn open the door for compensatory strategies such as ethnicisation and discrimination of outgroups (Anhut and Heitmeyer Citation2000, 50ff.).

This approach subsumes a number of dimensions that have received broad support in the empirical literature on anti-immigrant attitudes, although many of these studies have not explicitly based their arguments on social disintegration. Socio-economic factors of deprivation undoubtedly play a role in anti-immigrant attitudes (Ceobanu and Escandell Citation2010; Heizmann Citation2015, Citation2016; Heizmann and Huth Citation2021; Kunovich Citation2004; Ortega and Polavieja Citation2012; Schneider Citation2008), although this is not necessarily based on labour market competition (Hainmueller, Hiscox, and Margalit Citation2015). Political disintegration also was identified as meaningful (Heizmann Citation2015, Citation2016; Heizmann and Ziller Citation2020; Klein and Heitmeyer Citation2011; Macdonald Citation2020; Sides and Citrin Citation2007), while for the emotional part, measurements usually are scarce, but factors of social trust have also been found to be important predictors (Heizmann Citation2016; Sides and Citrin Citation2007; van der Linden et al. Citation2017).

The pandemic and its impact on individuals – consequences for immigration attitudes?

What can be said about the pandemic regarding these individual-level aspects? For each of these factors, one can observe that the pandemic quite clearly poses a strain on the respective domain of social integration. While we cannot empirically test these strains and merely employ them conceptually as bridge assumptions in our framework, the literatures referred to in the introduction and in the following paragraphs have exposed the broad impacts of the pandemic.

First, socio-economic hardships due to furloughs or firms shutting down are the most clearly visible aspect (Li and Mutchler Citation2020). Such factors also have been found relevant for individual well-being and the adherence to COVID-19-related policy measures (Kachanoff et al. Citation2021).

Second, the direct challenge the pandemic posits for political leadership may also lead to changes in political trust and related factors (Davies et al. Citation2021), not least because of the many contentious political decisions that need to be taken. However, there is some nuance to this: In some countries, a transitory ‘Rally round the flag’-effect has been observed (Kritzinger et al. Citation2021), which implies that government trust can benefit from the pandemic at least initially.

Finally, emotional disintegration can most clearly be exemplified by contact restrictions, mask mandates and other regulations that inhibit or weaken interactions with others, and the greatly reduced options for social contacts in one’s free time may also contribute to this socio-emotional strain (Rossi et al. Citation2020; Silveira et al. Citation2022).

In line with these arguments, there is also evidence for the importance of individual COVID-related attitudes for outgroup attitudes: Evidence from the UK and Ireland suggests that individual concerns about COVID-19 invigorate the authoritarian foundation of nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiments (Hartman et al. Citation2021). Similarly, Larsen and Schaeffer (Citation2021) show that there are chauvinistic tendencies regarding immigrants and their COVID-19-related healthcare access in a survey experiment in Denmark.

In sum, the pandemic can lead to numerous challenges for individual social integration and cohesion, and disintegration theory suggests that these challenges bear heavily on a range of outgroup attitudes, including immigration attitudes.Footnote1 In our view, the empirical record outlined above and the alignment of this concept to the pandemic’s consequences both underline the usefulness of this concept for our study. However, since immigration also is a macro-level phenomenon and a political issue, we must turn to the question of whether and how immigration and COVID-19 can be linked together. We therefore now turn to the comparative part of our study.

Immigration and COVID-19 – an ambivalent relationship

Although the pandemic and immigration are international phenomena, the relationship between the former and attitudes towards immigration is not straightforward. We start with conventional threat-based models and then turn to more recent arguments relating to immigration’s salience in media and public discourse, and recent empirical evidence regarding changes in policy agendas, public discourse and migration attitudes. As we shall see, both topics can be seen as competing for public, social and psychological attention.

A long tradition of research on contextual drivers of intergroup attitudes focuses on threat, conflict and scapegoating processes. For example, approaches like the group threat and realistic group conflict as well as the corresponding evidence (Blalock Citation1967; Blumer Citation1958; Ceobanu and Escandell Citation2010; LeVine and Campbell Citation1972; Quillian Citation1995; Scheepers, Gijsberts, and Coenders Citation2002; Schneider Citation2008; Semyonov, Raijman, and Gorodzeisky Citation2008) argue that crisis-like developments such as economic downturns and large-scale immigration have a threatening character that fosters negative outgroup attitudes.Footnote2 This suggests that in countries with a particularly severe pandemic, immigrants will become a target of derogation (Politi et al. Citation2021). Pandemic strength in our sense refers to COVID-19-related deaths in the country, which is continuously reported on and can therefore be assumed to have significant societal salience. Furthermore, based on these threat-based approaches, we also account for the immigrant presence within the countries.

However, based on the nascent literature on the pandemic and its societal and political framing, this supposed relationship is not self-evident. Although the virus itself appears to have propagated across national boundaries primarily through international travels, migration defined as long-term movements does not figure strongly as a causal driver of the pandemic in public debates, with the notable exception of arguments put forward by far-right parties (Wondreys and Mudde Citation2020).

A first point to note is that the extent of the pandemic should be much more present psychologically than immigration. This assertion derives from several theoretical approaches and some empirical evidence which suggest that immigration as a topic of public opinion depends to a considerable extent on its media coverage. It also derives from evidence that this topic is currently being overshadowed by the pandemic.

For example, due to their focus on the pandemic, the political arena and the media provide lower amounts of elite-based cueing regarding immigration (Hellwig and Kweon Citation2016; Steenbergen, Edwards, and de Vries Citation2007). This implies a crowding-out of the topic of immigration in politics, as Knill and Steinebach (Citation2022) have shown for the policy agenda in Germany. In this vein also, Dennison and Geddes (Citation2020) suggest that the implication of the pandemic for the topic of immigration may be ‘a period of ‘quieter’ immigration politics’ (Dennison and Geddes Citation2020, 1). There are similar arguments that COVID-19 has detrimental effects for far-right parties because of a decline in the salience of immigration as a political issue (Wondreys and Mudde Citation2020).

The importance of such public cueing is evident in the analyses by Schlueter and Davidov (Citation2011). They observe a close relationship between the presence of immigration as a news item and the development of negative migration-related sentiments, and there is similar evidence for Germany (Czymara and Dochow Citation2018). Media coverage also is reflected in individual social media sentiment expressions, as Menshikova and van Tubergen (Citation2022) show for Twitter users in the UK. Social media can therefore be seen to act as a multiplier.

As the space for issues in the public sphere is limited, whenever one topic such as COVID-19 gains strong salience, this will be at a cost for other topics like immigration, as exemplified by Boberg et al. (Citation2020) and Quandt et al. (Citation2020) who studied Facebook activity in Germany. They find immigration to be of comparatively lower salience (Boberg et al. Citation2020) or almost no salience (Quandt et al. Citation2020) due to a shift in focus towards the pandemic.

But also the psychological salience of the immigration issue appears to decline when new and complex crisis formations emerge. This is pertinent to our study, as immigration also is a complex issue that is not easily represented in citizens’ minds (Hellwig and Kweon Citation2016). For example, there are arguments and evidence for a limited capacity to simultaneously process several crisis phenomena (Sisco et al. Citation2022; Weber Citation2006). A study based on Dutch panel data corroborates this line of reasoning, finding that anti-immigrant prejudice was lower during the pandemic than before (Reeskens et al. Citation2021), while there are studies conducted in earlier phases or on specific immigrant groups such as EU immigrants that find no such changes (Drouhot et al. Citation2021; Fernández-i-Marín et al. Citation2021).

However, investigating regional-level factors across six countries instead of country-level factors, Freitag and Hofstetter (Citation2022) find that regional-level COVID deaths increase outgroup hostility. This is especially so for those reacting with anger, but for those reacting with fear, COVID deaths decrease outgroup hostility. While we cannot approach such psychological mechanisms, it is important to note that divergent geographic scales also imply divergent comparative perspectives and attendant within-country mechanisms. These in turn may well lead to divergent results when both perspectives are taken simultaneously (e.g. Weber Citation2015). Since we lack regional indicators, we can only speak to the country level of analysis. Nonetheless, our theoretical arguments and the attitudinal indicators we use are largely based on the national level, e.g. most of the media-based arguments presented above focus on the national frame rather than a regional or local one. Therefore, we argue that countries are an appropriate comparative focus for our research objectives.

In sum, the relationship between COVID-19 and migration-related attitudes has some ambiguities. As outlined above, conventional threat-based approaches lead us to the hypothesis that the severity of the pandemic is related positively to anti-immigrant attitudes, as we also expect for the individual-level factors of pandemic-related stressors. On the other hand, the unprecedented media presence of COVID-19 together with its rather tenuous direct relationship with immigration implies a sort of crowding-out of the immigration issue wherever the pandemic has a strong dynamic. The hypothesis that follows this rationale is that the severity of the pandemic is related negatively to anti-immigrant attitudes.Footnote3

Data and analytical approach

Data

The empirical analyses are based on an original cross-sectional online survey of the population in eleven European countries carried out between October and December 2020 (Katsanidou et al. Citation2021). The countries covered are Austria, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. The national field phase lengths vary from one to four weeks. A separate quota sample of 1000 respondents was drawn for each country based on a representative distribution for the characteristics age, gender and education. The data was collected by respondi.Footnote4

Due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, we do not investigate the effect of within-country developments on attitudes towards immigrants. Our analyses rather focus on how individual-level predictors and differences between countries relate to anti-immigrant attitudes.Footnote5

The survey is particularly well suited to address our research questions for three reasons. First, the survey was designed to cover the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the respondents’ opinions, feelings and various aspects of everyday life. It furthermore includes several types of attitudes towards immigrants and pandemic-related stressors. Second, the comparative nature of the data enables us to investigate between-country differences in addition to individual-level explanatories of anti-immigrant attitudes. Third, the net field phases of all countries comprised November and December 2020. Due to this short field phase across countries, the country samples are comparable regarding the global stage of the pandemic.

Country-level variables

On the country level, we take into account the extent of the COVID-19 pandemic and the foreign-population share. We operationalised the overall extent of the COVID-19 pandemic via the total of all deaths in the country up to shortly before the interview date by including the totals derived from the preceding Saturday. We took the average of the figures published by the WHOFootnote6 and Johns Hopkins University.Footnote7 We calculated the COVID-19 death rate per 100.000 persons and used the per-country mean over the respective field phase. This results in one value per country, i.e. a two-level data structure. However, as detailed in the robustness checks section below, we will also run additional three-level models that use the weekly values. The information of the national foreign-population share was provided by Eurostat.Footnote8 For better comparability, we min–max standardised both country-level variables to range from 0 to 1.Footnote9

Outcome variables

We have two dependent variables: the first refers to the general attitudes towards immigrants, the second variable refers to immigrant attitudes related to the current pandemic.

Our first dependent variable, perceived immigrant threat, was measured with three items asking respondents to rate to what extent they perceive immigrants as a cultural, economic or general threat. As an example, one question reads as follows: ‘In general, would you say it is good or bad for the [country]’s economy when immigrants come here to live?’ (answer categories range from 0 to 10). These three indicators mirror the respective measurements available in the European Social Survey.Footnote10 We combined the three items to one factor ranging from 0 to 10, with higher factor scores indicating a higher perceived immigrant threat. The Cronbach’s alpha of .9 indicates good reliability.

Our second dependent variable, blaming immigrants for the pandemic, was assessed by the question to what extent ‘the development of the COVID-19 pandemic in [country] is caused by immigrants’ (answer categories ranging from 0 ‘Not at all’ to 10 ‘Completely’). Table A1 in the appendix (see online supplementary material) presents the question wording and answer categories and Table A2 (see online supplementary material) the unweighted descriptive statistics for the employed variables. As we can see, the second outcome variable exhibits notable skewness. About one-third of the respondents chose ‘Not at all’ as the answer category, and 50 percent chose category two or below (i.e. including ‘Not at all’). However, all other categories are sufficiently populated. We dichotomise the variable at the median, which results in two similarly sized groups, but we also take several alternative approaches which are detailed in the robustness checks section below.

Explanatory variables

We include the pandemic’s perceived effect on the respondents’ socio-economic, political and emotional integration as predictors. Where feasible and expedient, we phrased the item in relation to the pandemic itself. For the socio-economic integration, respondents rated the pandemic threat for their financial situation on an 11-point Likert scale (0 ‘not threatening’ to 10 ‘very threatening’). The pandemic’s effect on the respondents’ emotional integration was measured with a question asking, ‘to what extent have you felt lonely in the last week?’ (1 ‘never or almost never’, 2 ‘sometimes’, 3 ‘mostly’, 4 ‘always or almost always’). For this, we furthermore asked whether this was ‘less often’, ‘equally often’ or ‘more often’ than before the pandemic.Footnote11 The respondents’ political integration was measured with a question asking about the respondents’ government trust (ranging from 1 ‘not at all’ to 7 ‘fully trust’) and political interest (1 ‘very interested’, 2 ‘quite interested’, 3 ‘not very interested’ and 4 ‘not interested at all’). The perceived adequacy of the region’s pandemic measures was measured with the question: Do you think the COVID-19 measures in your region are appropriate?' (1 ‘appropriate', 2 ‘somewhat appropriate', 3 ‘somewhat not appropriate', 4 ‘not at all appropriate’).

We also took several control indicators related to the pandemic into account: the perceived pandemic threat to health, and to the future national situation. For the health-related indicator, respondents answered whether they are concerned about their relatives’ health (0 ‘No’ and 1 ‘Yes’). The perceived national threat was measured on a 5-point Likert scale, answering the question ‘how much are you concerned about the future of [country] due to the COVID-19 pandemic?’.

Additionally, we controlled for the respondents’ age, gender, education, standard of living, political orientation and we excluded foreign-born respondents. Our final data set comprises 6.561 respondents in 11 countries. For the question wordings, answer categories and descriptive statistics, please refer to Tables A1 and A2 in the appendix (see online supplementary material).

Analytic strategy and robustness checks

To take the hierarchical structure of the data into account (respondents nested in countries), we employ multilevel models. Due to the relatively small number of countries, we keep the second level of our model parsimonious. For each dependent variable, we run one model with the COVID-19 death rate as the level-2 variable (models M1a and M1b) and another model with the foreign-population share included as the level-2 variable (models M2a and M2b). The analyses of the metric dependent variable, general attitudes towards immigrants, are carried out via Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) multilevel modelling with appropriate adjustments outlined by Elff et al. (Citation2020). The analyses of the binary dependent variable, blaming the pandemic on immigrants, are carried out in the REML-like multilevel binary logit framework (ibid.).

Due to the relatively small number of countries and the skewness of the second dependent variable, we performed several robustness checks. Please refer to the results section Robustness Checks for a detailed discussion of these additional checks. The findings of the additional checks are essentially the same as those of our main analyses presented below.

Empirical analyses

Descriptive results

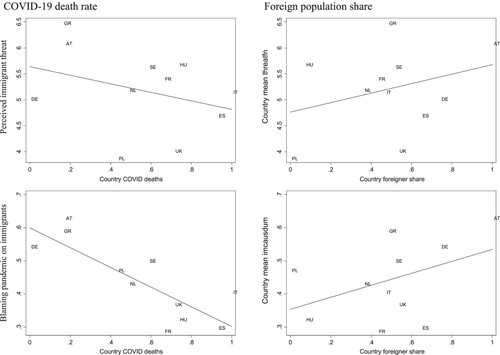

We begin our investigation with a series of scatterplots on the country level. The upper-left graph in shows that the population in countries that are more affected by COVID-19 tends to feel slightly less threatened by immigrants. The lower-left graph shows the country-mean association between blaming the pandemic on immigrants and the national COVID-19 situation. We can see that blaming the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrants is less pronounced in countries that are more affected by the pandemic. This could be a first indication for the crowding-out effect described above: Due to the pandemic’s severity, the migration issue is crowded out of the public debate and thus less salient.

Figure 1. Scatterplots of anti-immigrant attitudes, COVID-19 death rates and foreign-population share.

The graphs on the right-hand side show that the population in countries with a higher proportion of foreigners tends to more strongly perceive immigration as a threat and to blame immigrants for the pandemic, although both graphs suggest a less clear-cut relationship.

Multilevel results

We now turn to our findings based on the multilevel analyses. In columns 1 and 2 of , we show the models for perceived immigrant threat and in columns 3 and 4 for blaming the pandemic on immigrants. For better clarity and to focus on the key results, we show the results in in abbreviated form; Table A3 in the appendix (see online supplementary material) shows the results for the full models including all control variables.

Table 1. Multilevel results.

We first turn to the effects of the disintegration dimensions. Regarding political disintegration, the results confirm that higher political trust in the government is strongly associated with lower anti-immigrant attitudes (b = –.21, SE = .02), but we find no evidence for an effect on blaming the pandemic on immigrants (average marginal effect (AME) = .01, SE = .00). For the second item related to the political disintegration, the respondents’ political interest, we find statistically significant positive effects for both dependent variables. Thus, political disintegration in the sense of losing interest in the political situation predicts a higher perception of immigrants as threatening (e.g. not at all politically interested vs. very politically interested: b = 1.21, SE = .16) and blaming the pandemic on them (e.g. not at all politically interested vs. very politically interested: AME = .14, SE = .03). Furthermore, perceiving the regional measures as appropriate to control the COVID-19 pandemic predicts perceived immigrant threat. Greater discontent with the political measures is positively related to stronger anti-immigrant attitudes (e.g. COVID-19 measures are not at all appropriate vs. appropriate: b = .40, SE = .12). The high coefficients for the political integration predictors indicate a relatively strong impact, especially on perceived immigrant threat.

The coefficient estimates of the perceived emotional disintegration aspects are less clear. Whereas we find some evidence that feeling lonely predicts blaming immigrants for COVID-19, we find no or a reverse association with perceived immigrant threat. Further, people never and people always feeling lonely do not differ in their immigrant attitudes. We only find substantial differences in the middle categories. This finding may be explained by the fact that the group with the strongest loneliness is relatively small. There may also be further contravening social or psychological underpinnings of extensive loneliness and isolation that we cannot address with these data. These may explain why lonely persons are less likely to view immigration per se as a threat, while the same group is inclined to blame the pandemic on immigrants.

In a similar vein, we find that the perceived COVID-19 threat for one’s financial situation does not statistically significantly increase the perception of immigrant threat (b = –.02, SE = .01), but is positively associated with blaming the pandemic on immigrants (AME = .02, SE = .00). At the same time, anticipating negative consequences for the country’s future increases both immigrant threat (b = .17, SE = .03) and blaming (AME = .02, SE = .01).

In sum, the results regarding social disintegration suggest that primarily political (dis)integration is of high significance for immigration attitudes. However, issues of political and general trust are more relevant for general migration attitudes than for the blaming-immigrants item. Conversely, only the latter is decisively influenced by COVID-19’s threat to the personal financial situation, and the effect of loneliness also is more extensive here. Taken together, this suggests that blaming immigrants is more strongly related to individual risk-based mechanisms while general immigration threat is better explained by perceptions of collective societal and political aspects. Furthermore, one curious result is that persons deeming the regional COVID-19 measures to be ‘not at all appropriate’ do not appear to blame the pandemic on immigrants. A likely explanation is that these persons also may tend not to perceive the pandemic as a large problem per se, and therefore also tend not to blame it on immigrants.

To investigate differences in these anti-immigrant attitudes between countries, we now turn to the country-level results. First, we tested the impact of the foreign-population share on the perceived immigrant threat and blaming the pandemic on immigrants. However, this country-level effect on the two outcomes was not significant (see models M2a and M2b in for both outcomes). We also investigated the implications of the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic for national differences in anti-immigrant attitudes (see models M1a and M1b). Whereas our results imply a negative association between the pandemic’s severity and anti-immigrant attitudes for both outcomes (perceived immigrant threat: b = −1.12, SE = .77), the coefficient was only statistically significant for blaming the pandemic on immigrants (AME = −.35, SE = .06). This is in line with the graphical inspection of the scatter plots presented above, where this also was the most clear-cut relationship. However, in both cases, the negative coefficients speak strongly against the threat-based notion that the severity of COVID-19 as measured by us results in more negative attitudes towards immigration. Thus, our results suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic crowds out the immigration issue, rather than fostering negative public opinion on immigration.

Robustness checks

In addition to these analyses, we performed a series of robustness checks regarding the country-level variables. First, we made sure that our macro-level findings are not driven by a single country by re-running our models excluding one country at a time (Figures A1 to A4 in the appendix, see online supplementary material).Footnote12 While for all variants there are instances where the relationship turns statistically significant, it is only the relationship between COVID-19 deaths and ‘Blaming the pandemic on immigrants’ that is consistently statistically significant across all country subsamples. These additional analyses suggest that this relationship is not driven by a single country, but robust across the various subsamples of countries. It is also robust against including the foreign-population share (Model A4).

Furthermore, we check the robustness of the country-level effects using Bayesian multilevel modelling with weakly informative priors (Gelman et al. Citation2008) (see Tables A5 to A8 in the appendix, see online supplementary material). The country-level results of the Bayesian multilevel models are similar to our results presented above: the results indicate no association between the foreign-population share and the two dependent variables (M2a: = .14 Std. Dev = .09; M2b:

= .43 Std. Dev = .42). The model results again suggest that the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic is negatively associated with blaming the pandemic on immigrants (M1a:

= −.11 Std. Dev. = .10; M1b:

= −1.01 Std. Dev = .21). The aforementioned result for this indicator also is evident when looking at models based on extended quasi-likelihood (EQL) estimation presented in appendix Table A9 (see online supplementary material). Finally, for both the Bayesian and the EQL models, the finding for COVID-19 deaths also does not change substantially when excluding individual countries (Tables A10 and A11 in the appendix, see online supplementary material).

We also investigated the association between COVID-19 deaths and anti-immigrant attitudes using the weekly figures of the COVID-19 deaths and applying a three-level model (6561 respondents nested in 33 country-weeks nested in 11 countries). The findings are essentially the same, which can be explained by the strong correlation of .97 of the weekly values and their averages (Table A12 in the appendix, see online supplementary material).

We further run additional models to check the robustness of our findings across different strategies to address the skewness of the second dependent variable ‘blaming the pandemic on immigrants’. First, we used the log- and the square-root transformation to alleviate the non-normality issue (Tables A13 and A14 in the appendix, see online supplementary material). We employed REML multilevel models for these additional models. Second, we rerun the analyses with the untransformed dependent variable using negative binomial models, as suggested by one Reviewer. Treating the outcome variable as a count variable may be problematic, since the data-generating process behind this attitudinal dimension arguably does not follow a count process, and the distribution also is somewhat bimodal regarding the midpoint of the scale. Nonetheless, we included this robustness check in our analysis (Table A15 in the online appendix, see online supplementary material). The results presented for these models also do not change the focal implications of our primary analysis. For the other indicators, the only exception is that the indicators for assessing the regional COVID-19 measures as appropriate are less significant for these three models. In sum, these additional analyses further support our conclusion that a more severe pandemic on the country level is associated with less blame being put on immigrants.

Discussion and conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has left a considerable mark on the everyday lives of people across the world. While the pandemic itself has moved to a stage of partially being kept at bay through vaccinations, the continuous emergence of new virus variants suggests that the pandemic is not over in summer 2022. This underlines that research on the societal repercussions of the pandemic still is of high relevance, also because some data collected during the pandemic are not available yet. With our study we were able to make two primary contributions to the nascent literature on this topic: Firstly, we shed light on the potential consequences of individual pandemic perceptions for attitudes towards immigrants, and secondly, our comparative database and approach made it possible to investigate country-level factors of the pandemic severity alongside immigrant presence.

Regarding the indicator of the COVID-19 pandemic being caused by immigration, the first issue to note is its skewed distribution. This already hints at the fact that the attitude measured here is of a somewhat extreme nature, which is in line with previous arguments and evidence mentioned above that suggests a rather tenuous connection between migration and COVID-19. However, the multivariate results are more clearly in line with the theoretical arguments formulated than is the case for conventional migration-related attitudes. This suggests that this is a particularly prejudicial indicator that is well-explained by the individual-level model presented above. It also suggests that the pandemic may have notable consequences for pandemic-related immigration attitudes beyond the ones we covered, and potentially also for other types of intergroup attitudes or solidarities. Nevertheless, we demonstrated that several aspects of the pandemic also have an impact on the more general question of perceived immigrant threat.

On the individual level, there is clear evidence that pandemic-related perceptions and appraisals are associated with both outcome variables, but with important variations. While viewing the pandemic as a threat to the country’s future is important for both outcomes, issues of political and general trust are more important for general immigration threat perceptions. In contrast, individual aspects of emotional and socio-economic integration are only associated with blaming the pandemic on immigrants.

It thus appears that specific personal aspects of the pandemic activate a specific scapegoating mechanism of sorts, rather than resulting in an articulation of broad perceptions of threat. In contrast, the assessments of politics as embodied by political trust and of the general trustworthiness of society refer to more distal aspects, which appear to be foundational for the broader issue of perceived immigrant threat. Put differently, distal measures overall are more important for the more general outcome, while the more proximate issues are overall more important for pandemic-related outcome. This pattern of relationships exemplifies how such a comparison of outcome variables enables additional insights especially when the empirical background setting is as novel as is the case with this pandemic.

On the country level, we find that the extent of the pandemic is related negatively only to the indicator of blaming the pandemic on immigration. The direction contradicts conventional approaches related to macro-level threats. Instead, it is in line with arguments and evidence from previous research we presented above which show that immigration as a topic largely has been displaced by the pandemic: Where the pandemic situation is most dire, the pandemic itself becomes the salient field of political action. Because these attitudes have been shown to be strongly affected by political, public and social media discourses, such a shift of attention away from immigration leads to comparatively favourable attitudes towards immigrants. In contrast, where the pandemic was less pernicious, blaming the pandemic on immigrants is more common. This seemingly contradicts the individual-level findings for pandemic-related perceptions, but it is important to bear in mind both result sets come from different analytical levels: At the individual level, immediate threats and the socio-emotional underpinnings thereof appear to be a profound stressor that increases negative attitudes towards immigrants, while on the country level, the pandemic eclipses the topic of immigration as a focus of societal attention.

An immediate limitation of the survey data employed is that it only includes 11 countries at one point in time so that we cannot draw firm causal conclusions. All our results, therefore, indicate correlative relations only. However, we sought to circumvent the issue of the low number of countries by performing numerous robustness checks. Based on these models and the graphical evidence regarding the country-level factors, the results strongly point towards a negative relationship between pandemic severity and blaming the pandemic on immigrants. Moreover, even if one remains sceptical regarding this substantive conclusion, it still appears highly unlikely that COVID-19 death rates are actually driving anti-immigrant sentiments, i.e. that there really is a positive relationship instead of the negative one visible above for the eleven countries investigated here. We argue that even this reduced and more cautious interpretation is an important country-level implication of our study that applies to both outcome variables. Furthermore, we could not address the potential roles of differences in government compositions, political party positions and actual migration- or pandemic-related policies. We would argue that our controlling for the left-right-dimension at least captures a part of the country-level compositional variance of this dimension. Nonetheless, these factors clearly warrant a more direct approach in future research, once the respective macro-level data are available for a sufficient set of countries. Finally, with our data, we are not able to compare pre- and post-pandemic situations. This would be desirable in order to be on firmer ground regarding the causality of the reported individual-relationships and to investigate potential mediation mechanisms. It would also allow to separate more clearly long-term structural disintegration from situational pandemic-related changes in disintegration for all individual-level variables. We could only do this for a limited set of variables by asking about pandemic-related developments. However, as noted above, such an approach would entail additional conceptual and methodological challenges directly related to the pandemic situation, such as necessary item formulation deviations or divergent fieldwork procedures, or a pre-pandemic survey being incidentally pandemic-compatible while including the relevant items at all time points. To our knowledge, such a survey does not exist.

When taken together, the overall conclusion of our results is that the currently low salience of the immigration issue should not be taken as indicative of relaxed public opinion per se. On the country-level, there may well be a rebound once the pandemic is over or at least sufficiently contained. But even more urgent are the implications derived from our individual-level findings: It is evident that several pandemic-related factors are notably associated with negative attitudes towards immigrants despite the rather tenuous link between both. This exemplifies the divisive potential of the pandemic. This also constitutes a broad potential since it applies to individual perceptions in the form of economic fears, but also collective perspectives such as agreement to policies and worries about the future of the country. Future research should therefore apply a wide lens when it comes to societal consequences of the pandemic: It appears that marginalised groups can easily become scapegoats, and this may be true for many other social cleavages as well, as evidenced by the literature on the situation of Asian-Americans during the pandemic. A more policy-related implication is that officials should be keenly aware of the dangers inherent in the current situation, but also of the potentials of turning the collective threat of the pandemic into a collective source of inclusion (Vollhardt and Staub Citation2011). The pandemic created a stress test for social cohesion that must not be left unchecked even when the pandemic itself may have subsided.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (833.1 KB)Acknowledgements

This research was conducted in the context of the project ‘Change through Crisis? Solidarity and Desolidarization in Germany and Europe (Solikris)’ (https://www.gesis.org/en/projekte/solikris/home) work package 3 ‘Xenophobia vs. Tolerance’. It was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive criticisms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The raw survey data ‘Everyday Life in Germany and Europe 2020 (Solikris)’ that support the findings of this study are available at the GESIS Data Archive at doi:10.4232/1.13787, study number ZA7776, Data file Version 1.0.0.

The macro data of the COVID-19 death rate that support the findings of this study are available within the article’s supplementary materials. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-data-explorer and https://covid19.who.int/.

The macro data of the foreign-population share that support the findings of this study are available within the article’s supplementary materials. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00157/default/table?lang=en.

The STATA script JEMS_covid_imm_attitudes.do and the R script JEMS_covid_imm_attitudes_R_script.R for the data preparation and analyses that support the findings of this study are available within the article’s supplementary materials. The package is available at https://osf.io/xufmg/.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 It is important to note that our analysis is based primarily on concepts and arguments from sociology and political science and only to some extent social psychology. Our starting point is therefore focused on the broad consequences the pandemic has for individual-level everyday lives. In other disciplines such as public health, psychology, and related applied fields, concepts like germ aversion, pathogen avoidance, and various types of disease threats also provide useful starting points. However, these perspectives are focused more directly on the disease itself, rather than economic, social and emotional corollaries of interest to us (Ahorsu et al. Citation2020; Freitag and Hofstetter Citation2022; Green et al. Citation2010; Mertens et al. Citation2021). Given our focus and the lack of such measures in our data, we cannot incorporate these concepts into our study.

2 Regarding immigrant presence on the macro level, based on the contact hypothesis (Allport Citation1954; Pettigrew Citation1998; Pettigrew and Tropp Citation2006) one can posit that immigration can lead to more tolerant attitudes because of a familiarisation with and a normalisation of the migration issue. However, the occurrence of such an effect greatly depends on the analytical level (Weber Citation2015), and evidence for such an effect on the country level appears limited to specific types of immigrants and immigration-related attitudes (Ceobanu and Escandell Citation2010; Green Citation2009; Heizmann Citation2016).

3 One reviewer suggested to investigate the labour market presence of immigrants in the health and care sectors or to approach potentially divergent infection and mortality rates for immigrants when compared to natives. While these are undoubtedly of interest, we would argue that they would require another article: Both would require extensive additional theorising beyond our scope, and some of the required data may not be readily available.

5 Although it would be of interest to investigate how general attitudes towards immigrants changed due to the pandemic, comparing cross-sectional data surveyed before and during the pandemic is a difficult undertaking. Due to the pandemic, many repeated cross-sectional surveys face major organisational and methodological challenges in their fieldwork (e.g. changing from face-to-face data collection to telephone-based interviews or online self-completion questionnaires); For individual-level panel data the situation is similar, with the added potential complication of changing attrition and mortality patterns (for an overview see the special issue in the journal Survey Research Methods (Kohler Citation2020)). Finally, asking about the pandemic situation within the country would not make sense to respondents in pre-pandemic societies. Our second dependent variable and some predictor variables would therefore not be feasible to field in such a setting. While telephone surveys are less affected by the pandemic, we are not aware of a survey that provides the measures needed for our research questions while providing pre- and post-pandemic measurements (time points) across several countries.

8 https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00157/default/table?lang=en For the EU countries, we used the 2020 figures, whereas we used the 2019 figures for the UK.

9 It would also be worthwhile to also investigate the macro-economic situation. However, given the recency of the data and the wide-ranging political compensations for the affected economies, such a perspective cannot be feasibly integrated at the time of writing. For example, government programmes that counter immediate economic consequences may mask the real macro-economic consequences of this pandemic. These consequences will probably get visible only later on, so that we are currently not in a position to address this properly.

11 In theory, one could field such an additional retrospective item for virtually all aspects. Restrictions on questionnaire length led us to the approach taken here: We asked for the pandemic effects directly where feasible, with the exception of feeling lonely, where it seemed important to augment measuring current loneliness with the corresponding pre-pandemic tendencies.

12 To create the figures, we modified the Stata script for specification curves provided by Simonsohn, Simmons, and Nelson (Citation2020).

References

- Adler, Eli, Shira Hebel-Sela, Oded Adomi Leshem, Jonathan Levy, and Eran Halperin. 2022. “A Social Virus: Intergroup Dehumanization and Unwillingness to Aid Amidst COVID-19 − Who Are the Main Targets?⋆.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 86: 109–121. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.11.006.

- Ahorsu, Daniel Kwasi, Chung-Ying Lin, Vida Imani, Mohsen Saffari, Mark D. Griffiths, and Amir H. Pakpour. 2020. “The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation.” International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 20: 1537–1545. doi:10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8.

- Allport, Gordon. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Cambridge: Addison-Wesley.

- Anhut, Reimund, and Wilhelm Heitmeyer. 2000. “Desintegration, Konflikt Und Ethnisierung. Eine Problemanalyse Und Theoretische Rahmenkonzeption.” In Bedrohte Stadtgesellschaften. Gesellschaftliche Desintegrationsprozesse und ethnisch-kulturelle Konfliktdimensionen, edited by W. Heitmeyer, and R. Anhut, 17–75. Weinheim: Juventa.

- Anhut, Reimund, and Wilhelm Heitmeyer. 2009. “Desintegration, Anerkennungsbilanzen Und Die Rolle Sozialer Vergleichsprozesse Für Unterschiedliche Verarbeitungsmuster.” In Neuer Mensch und kollektive Identität in der Kommunikationsgesellschaft, edited by G. Preyer, 212–236. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Beck, Ulrich. 1986. Risikogesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Bhattacharjee, Barnali, and Tathagata Acharya. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Effect on Mental Health in USA – A Review with Some Coping Strategies.” Psychiatric Quarterly 91 (4): 1135–1145. doi:10.1007/s11126-020-09836-0.

- Blalock, Hubert M. 1967. Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations. New York: Wiley.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1958. “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position.” The Pacific Sociological Review 1 (1): 3–7.

- Boberg, Svenja, Thorsten Quandt, Tim Schatto-Eckrodt, and Lena Frischlich. 2020. “Pandemic Populism: Facebook Pages of Alternative News Media and the Corona Crisis - A Computational Content Analysis.” Preprint ArXiv:2004.02566.

- Bohle, Hans Hartwig, Wilhelm Heitmeyer, Wolfgang Kühnel, and Uwe Sander. 1997. “Anomie in Der Modernen Gesellschaft: Bestandsaufnahme Und Kritik Eines Klassischen Ansatzes Soziologischer Analyse.” In Was treibt die Gesellschaft auseinander?, edited by W. Heitmeyer. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Borkowska, Magda, and James Laurence. 2021. “Coming Together or Coming Apart? Changes in Social Cohesion During the Covid-19 Pandemic in England.” European Societies 23 (sup1): S618–S636. doi:10.1080/14616696.2020.1833067.

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2020. “Paradoxes of Populism During the Pandemic.” Thesis Eleven 164(1): 73–87. doi:10.1177/0725513620970804.

- Ceobanu, Alin M., and Xavier Escandell. 2010. “Comparative Analyses of Public Attitudes Toward Immigrants and Immigration Using Multinational Survey Data: A Review of Theories and Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 36 (1): 309–328. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102651.

- Chen, H. Alexander, Jessica Trinh, and George P. Yang. 2020. “Anti-Asian Sentiment in the United States–COVID-19 and History.” The American Journal of Surgery 220 (3): 556–557. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.05.020.

- Czymara, Christian S., and Stephan Dochow. 2018. “Mass Media and Concerns About Immigration in Germany in the 21st Century: Individual-Level Evidence Over 15 Years.” European Sociological Review 34 (4): 381–401. doi:10.1093/esr/jcy019.

- Davies, Ben, Fanny Lalot, Linus Peitz, Maria S. Heering, Hilal Ozkececi, Jacinta Babaian, Kaya Davies Hayon, Jo Broadwood, and Dominic Abrams. 2021. “Changes in Political Trust in Britain During the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020: Integrated Public Opinion Evidence and Implications.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8 (1): 166. doi:10.1057/s41599-021-00850-6.

- Dennison, James, and Andrew Geddes. 2020. “Why COVID-19 Does Not Necessarily Mean That Attitudes towards Immigration Will Become More Negative.” IOM Policy Paper, 2020, [Migration Policy Centre] - https://hdl.handle.net/1814/68055

- Dollmann, Jörg, and Irena Kogan. 2021. “COVID-19–Associated Discrimination in Germany.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 74: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.rssm.2021.100631.

- Drouhot, Lucas G., Sören Petermann, Karen Schönwälder, and Steven Vertovec. 2021. “Has the Covid-19 Pandemic Undermined Public Support for a Diverse Society? Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Germany.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (5): 877–892. doi:10.1080/01419870.2020.1832698.

- Durkheim, Emile. 2005. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. London: Routledge.

- Elff, Martin, Jan Paul Heisig, Merlin Schaeffer, and Susumu Shikano. 2020. “Multilevel Analysis with Few Clusters: Improving Likelihood-Based Methods to Provide Unbiased Estimates and Accurate Inference.” British Journal of Political Science 51 (1): 412–426. doi:10.1017/S0007123419000097.

- Esses, Victoria M., and Leah K. Hamilton. 2021. “Xenophobia and Anti-Immigrant Attitudes in the Time of COVID-19.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 24 (2): 253–259. doi:10.1177/1368430220983470.

- Federico, Christopher M., Agnieszka Golec de Zavala, Tomasz Baran, and Christopher M. Federico. 2021. “Collective Narcissism, In-Group Satisfaction, and Solidarity in the Face of COVID-19.” Social Psychological & Personality Science. 12(6):1071–1081. doi:10.1177/1948550620963655.

- Fernández-i-Marín, Xavier, Carolin H. Rapp, Christian Adam, Oliver James, and Anita Manatschal. 2021. “Discrimination Against Mobile European Union Citizens Before and During the First COVID-19 Lockdown: Evidence from a Conjoint Experiment in Germany.” European Union Politics 22 (4): 741–761. doi:10.1177/14651165211037208.

- Freitag, Markus, and Nathalie Hofstetter. 2022. “Pandemic Threat and Intergroup Relations: How Negative Emotions Associated with the Threat of Covid-19 Shape Attitudes Towards Immigrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (13): 2985–3004. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2031925.

- Gandenberger, Mia K., Carlo M. Knotz, Flavia Fossati, and Giuliano Bonoli. 2022. “Conditional Solidarity - Attitudes Towards Support for Others During the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Social Policy, 1–19. doi:10.1017/S0047279421001070.

- Gelman, Andrew, Aleks Jakulin, Maria Grazia Pittau, and Yu-Sung Su. 2008. “A Weakly Informative Default Prior Distribution for Logistic and Other Regression Models.” The Annals of Applied Statistics 2 (4): 1360–1383. doi:10.1214/08-AOAS191.

- Green, Eva G. T. 2009. “Who Can Enter? A Multilevel Analysis on Public Support for Immigration Criteria Across 20 European Countries.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 12 (1): 41–60. doi:10.1177/1368430208098776.

- Green, Eva G. T., Franciska Krings, Christian Staerklé, Adrian Bangerter, Alain Clémence, Pascal Wagner-Egger, and Thierry Bornand. 2010. “Keeping the Vermin out: Perceived Disease Threat and Ideological Orientations as Predictors of Exclusionary Immigration Attitudes.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 20 (4): 299–316. doi:10.1002/casp.1037.

- Hainmueller, Jens, Michael J. Hiscox, and Yotam Margalit. 2015. “Do Concerns About Labor Market Competition Shape Attitudes Toward Immigration? New Evidence.” Journal of International Economics 97 (1): 193–207. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2014.12.010.

- Hartman, Todd K., Thomas V. A. Stocks, Ryan McKay, Jilly Gibson-Miller, Liat Levita, Anton P. Martinez, Liam Mason, et al. 2021. “The Authoritarian Dynamic During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Effects on Nationalism and Anti-Immigrant Sentiment.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 12 (7): 1274–1285. doi:10.1177/1948550620978023.

- Heitmeyer, Wilhelm, and Reimund Anhut. 2008. “Disintegration, Recognition, and Violence: A Theoretical Perspective.” New Directions for Youth Development 2008 (119): 25–37. doi:10.1002/yd.271.

- Heizmann, Boris. 2015. “Social Policy and Perceived Immigrant Labor Market Competition in Europe: Is Prevention Better Than Cure?” Social Forces 93 (4): 1655–1685. doi:10.1093/sf/sou116.

- Heizmann, Boris. 2016. “Symbolic Boundaries, Incorporation Policies, and Anti-Immigrant Attitudes: What Drives Exclusionary Policy Preferences?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (10): 1791–1811. doi:10.1080/01419870.2015.1124128.

- Heizmann, Boris, and Nora Huth. 2021. “Economic Conditions and Perceptions of Immigrants as an Economic Threat in Europe: Temporal Dynamics and Mediating Processes.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 62 (1): 56–82. doi:10.1177/0020715221993529.

- Heizmann, Boris, and Conrad Ziller. 2020. “Who Is Willing to Share the Burden? Attitudes Towards the Allocation of Asylum Seekers in Comparative Perspective.” Social Forces 98 (3): 1026–1051. doi:10.1093/sf/soz030.

- Hellwig, Timothy, and Yesola Kweon. 2016. “Taking Cues on Multidimensional Issues: The Case of Attitudes Toward Immigration.” West European Politics 39 (4): 710–730. doi:10.1080/01402382.2015.1136491.

- Kachanoff, Frank J., Yochanan E. Bigman, Kyra Kapsaskis, and Kurt Gray. 2021. “Measuring Realistic and Symbolic Threats of COVID-19 and Their Unique Impacts on Well-Being and Adherence to Public Health Behaviors.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 12 (5): 603–616. doi:10.1177/1948550620931634.

- Katsanidou, Alexia, Heiko Giebler, Jale Tosun, Ann-Kathrin Reinl, Steffen Pötzschke, Christina Eder, Boris Heizmann, Bernhard Weßels, Nora Huth, Sandra Horvath, Anne-Marie Parth, Constanza Sanhueza, and Julia Weiß. 2021. “Everyday Life in Germany and Europe 2020 (Solikris). GESIS Datenarchiv, Köln. ZA7776 Dataset Version 1.0.0.” doi:10.4232/1.13787.

- Klein, Anna, and Wilhelm Heitmeyer. 2011. “Demokratieentleerung Und Ökonomisierung Des Sozialen: Ungleichwertigkeit Als Folge Verschobener Kontrollbilanzen.” Leviathan 39 (3): 361–383. doi:10.1007/s11578-011-0129-7.

- Knill, Christoph, and Yves Steinebach. 2022. “What Has Happened and What Has Not Happened Due to the Coronavirus Disease Pandemic: A Systemic Perspective on Policy Change.” Policy and Society 41 (1): 25–39. doi:10.1093/polsoc/puab008.

- Kohler, Ulrich. 2020. “Survey Research Methods During the COVID-19 Crisis.” Survey Research Methods 14: 2. doi:10.18148/srm/2020.v14i2.7769.

- Kritzinger, Sylvia, Martial Foucault, Romain Lachat, Julia Partheymüller, Carolina Plescia, and Sylvain Brouard. 2021. “‘Rally Round the Flag’: The COVID-19 Crisis and Trust in the National Government.” West European Politics 44 (5–6): 1205–1231. doi:10.1080/01402382.2021.1925017.

- Kunovich, Robert M. 2004. “Social Structural Position and Prejudice: An Exploration of Cross-National Differences in Regression Slopes.” Social Science Research 33 (1): 20–44. doi:10.1016/S0049-089X(03)00037-1.

- Larsen, Mikkel Haderup, and Merlin Schaeffer. 2021. “Healthcare Chauvinism During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (7): 1455–1473. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1860742.

- LeVine, Robert Alan, and Donald Thomas Campbell. 1972. Ethnocentrism: Theories of Conflict, Ethnic Attitudes and Group Behavior. New York: Wiley.

- Li, Yang, and Jan E. Mutchler. 2020. “Older Adults and the Economic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 32 (4–5): 477–487. doi:10.1080/08959420.2020.1773191.

- Macdonald, David. 2020. “Political Trust and Support for Immigration in the American Mass Public.” British Journal of Political Science 51 (4): 1402–1420. doi:10.1017/S0007123419000668.

- Menshikova, Anastasia, and Frank van Tubergen. 2022. “What Drives Anti-Immigrant Sentiments Online? A Novel Approach Using Twitter.” European Sociological Review 1–13. doi:10.1093/esr/jcac006.

- Mertens, Gaëtan, Stefanie Duijndam, Tom Smeets, and Paul Lodder. 2021. “The Latent and Item Structure of COVID-19 Fear: A Comparison of Four COVID-19 Fear Questionnaires Using SEM and Network Analyses.” Journal of Anxiety Disorders 81: 102415. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102415.

- Naumann, Elias, Katja Möhring, Maximiliane Reifenscheid, Alexander Wenz, Tobias Rettig, Roni Lehrer, Ulrich Krieger, et al. 2020. “COVID-19 Policies in Germany and Their Social, Political, and Psychological Consequences.” European Policy Analysis 6 (2): 191–202. doi:10.1002/epa2.1091.

- Ortega, Francesc, and Javier G. Polavieja. 2012. “Labor-Market Exposure as a Determinant of Attitudes Toward Immigration.” Labour Economics 19 (3): 298–311. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2012.02.004.

- Pettigrew, Thomas F. 1998. “Intergroup Contact Theory.” Annual Review of Psychology 49 (1): 65–85. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65.

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Linda R. Tropp. 2006. “A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (5): 751–783. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751.

- Politi, Emanuele, Adrian Lüders, Sindhuja Sankaran, Joel Anderson, Jasper Van Assche, Eva Spiritus-Beerden, Antoine Roblain, et al. 2021. “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Majority Population, Ethno-Racial Minorities, and Immigrants.” European Psychologist 26 (4): 298–309. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000460.

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Quandt, Thorsten, Svenja Boberg, Tim Schatto-Eckrodt, and Lena Frischlich. 2020. “Pandemic News: Facebook Pages of Mainstream News Media and the Coronavirus Crisis – A Computational Content Analysis.” Preprint, ArXiv:2005.13290. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2005.13290.

- Quillian, Lincoln. 1995. “Prejudice as a Response to Perceived Group Threat: Population Composition and Anti-Immigrant and Racial Prejudice in Europe.” American Sociological Review 60 (4): 586–611. doi:10.2307/2096296.

- Reeskens, Tim, Quita Muis, Inge Sieben, Leen Vandecasteele, Ruud Luijkx, and Loek Halman. 2021. “Stability or Change of Public Opinion and Values During the Coronavirus Crisis? Exploring Dutch Longitudinal Panel Data.” European Societies 23 (sup1): S153–S171. doi:10.1080/14616696.2020.1821075.

- Rossi, Alessandro, Anna Panzeri, Giada Pietrabissa, Gian Mauro Manzoni, Gianluca Castelnuovo, and Stefania Mannarini. 2020. “The Anxiety-Buffer Hypothesis in the Time of COVID-19: When Self-Esteem Protects from the Impact of Loneliness and Fear on Anxiety and Depression.” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 2177. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02177.

- Schaeffer, Merlin, and Mikkel Haderup Larsen. 2022. “Who Should Get Vaccinated First? Limits of Solidarity During the First Week of the Danish Vaccination Programme.” European Sociological Review 1–13. doi:10.1093/esr/jcac025.

- Scheepers, Peer, Merove Gijsberts, and Marcel Coenders. 2002. “Ethnic Exclusionism in European Countries. Public Opposition to Civil Rights for Legal Migrants as a Response to Perceived Ethnic Threat.” European Sociological Review 18 (1): 17–34. doi:10.1093/esr/18.1.17.

- Schild, Leonard, Chen Ling, Jeremy Blackburn, Gianluca Stringhini, Yang Zhang, and Savvas Zannettou. 2020. “‘ Go Eat a Bat, Chang!’: An Early Look on the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the Face of Covid-19.” Preprint, ArXiv:2004.04046. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2004.04046.

- Schlueter, Elmar, and Eldad Davidov. 2011. “Contextual Sources of Perceived Group Threat: Negative Immigration-Related News Reports, Immigrant Group Size and Their Interaction, Spain 1996-2007.” European Sociological Review 29 (2): 179–191. doi:10.1093/esr/jcr054.

- Schneider, Silke L. 2008. “Anti-Immigrant Attitudes in Europe: Outgroup Size and Perceived Ethnic Threat.” European Sociological Review 24 (1): 53–67. doi:10.1093/esr/jcm034.

- Semyonov, Moshe, Rebeca Raijman, and Anastasia Gorodzeisky. 2008. “Foreigners’ Impact on European Societies.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 49 (1): 5–29. doi:10.1177/0020715207088585.

- Shanahan, Lilly, Annekatrin Steinhoff, Laura Bechtiger, Aja L. Murray, Amy Nivette, Urs Hepp, Denis Ribeaud, and Manuel Eisner. 2020. “Emotional Distress in Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence of Risk and Resilience from a Longitudinal Cohort Study.” Psychological Medicine 52 (2): 824–833. doi:10.1017/S003329172000241X.

- She, Zhuang, Kok-Mun Ng, Xiangling Hou, and Juzhe Xi. 2022. “COVID-19 Threat and Xenophobia: A Moderated Mediation Model of Empathic Responding and Negative Emotions.” Journal of Social Issues 78 (1): 209–226. doi:10.1111/josi.12500.

- Sides, John, and Jack Citrin. 2007. “European Opinion About Immigration: The Role of Identities, Interests and Information.” British Journal of Political Science 37 (03): 477–504. doi:10.1017/S0007123407000257.

- Silveira, Sarita, Martin Hecht, Hannah Matthaeus, Mazda Adli, Manuel C. Voelkle, and Tania Singer. 2022. “Coping with the COVID-19 Pandemic: Perceived Changes in Psychological Vulnerability, Resilience and Social Cohesion Before, During and After Lockdown.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 6. doi:10.3390/ijerph19063290.

- Simonsohn, Uri, Joseph P. Simmons, and Leif D. Nelson. 2020. “Specification Curve Analysis.” Nature Human Behaviour 4 (11): 1208–1214. doi:10.1038/s41562-020-0912-z.

- Sisco, Matthew, Sara Constantino, Yu Gao, Massimo Tavoni, Alicia Cooperman, Valentina Bossetti, and Elke Weber. 2022. “A Finite Pool of Worry or a Finite Pool of Attention? Evidence and Qualifications.” Preprint available at Research Square 1–6. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-98481/v1.

- Steenbergen, Marco R., Erica E. Edwards, and Catherine E. de Vries. 2007. “Who’s Cueing Whom?” European Union Politics 8 (1): 13–35. doi:10.1177/1465116507073284.

- Teymoori, Ali, Brock Bastian, and Jolanda Jetten. 2017. “Towards a Psychological Analysis of Anomie.” Political Psychology 38 (6): 1009–1023. doi:10.1111/pops.12377.

- Van Assche, Jasper, Emanuele Politi, Pieter Van Dessel, and Karen Phalet. 2020. “To Punish or to Assist? Divergent Reactions to Ingroup and Outgroup Members Disobeying Social Distancing.” British Journal of Social Psychology 59 (3): 594–606. doi:10.1111/bjso.12395.

- Van der Linden, Meta, Marc Hooghe, Thomas de Vroome, and Colette Van Laar. 2017. “Extending Trust to Immigrants: Generalized Trust, Cross-Group Friendship and Anti-Immigrant Sentiments in 21 European Societies.” PLOS ONE 12 (5): e0177369. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177369.

- Vollhardt, Johanna R., and Ervin Staub. 2011. “Inclusive Altruism Born of Suffering: The Relationship Between Adversity and Prosocial Attitudes and Behavior Toward Disadvantaged Outgroups.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 81 (3): 307–315. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01099.x.

- Wang, Simeng, Xiabing Chen, Yong Li, Chloé Luu, Ran Yan, and Francesco Madrisotti. 2021. “‘I’m More Afraid of Racism Than of the Virus!’: Racism Awareness and Resistance among Chinese Migrants and Their Descendants in France During the Covid-19 Pandemic.” European Societies 23 (sup1): S721–S742. doi:10.1080/14616696.2020.1836384.

- Weber, Elke U. 2006. “Experience-Based and Description-Based Perceptions of Long-Term Risk: Why Global Warming Does Not Scare Us (Yet).” Climatic Change 77 (1): 103–120. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9060-3.

- Weber, Hannes. 2015. “National and Regional Proportion of Immigrants and Perceived Threat of Immigration: A Three-Level Analysis in Western Europe.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 56 (2): 116–140. doi:10.1177/0020715215571950.

- Wondreys, Jakub, and Cas Mudde. 2020. “Victims of the Pandemic? European Far-Right Parties and COVID-19.” Nationalities Papers 50 (1): 86–103. doi:10.1017/nps.2020.93.

- Wu, Cary, Yue Qian, and Rima Wilkes. 2021. “Anti-Asian Discrimination and the Asian-White Mental Health Gap During COVID-19.” Ethnic & Racial Studies 44 (5): 819–835. doi:10.1080/01419870.2020.1851739.

- Zagefka, Hanna. 2021. “Intergroup Helping During the Coronavirus Crisis: Effects of Group Identification, Ingroup Blame and Third Party Outgroup Blame.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 31 (1): 83–93. doi:10.1002/casp.2487.