ABSTRACT

In today’s migration and refugee governance, refugees are increasingly required to demonstrate both vulnerability and assimilability to be considered deserving of protection and territorial access. This article advances the notion of ‘promising victimhood’ [Chauvin, Sébastien, and Blanca Garcés-Mascareñas. 2018. The Myth of Humanitarianism: Migrant Deservingness, Promising Victimhood, and Neoliberal Reason. Barcelona] as a fruitful concept to capture the contrasting demands refugees face: policies and practices that require refugees to demonstrate that they are currently vulnerable and at risk, yet willing and able to ‘overcome’ their vulnerability to become law-abiding, self-sufficient and culturally malleable members of their host societies in the future. Taking the example of selection practices in refugee resettlement to Europe, I show how ‘promising victimhood’ is characterised by tensions between vulnerability and three dimensions of assimilability: (1) security, (2) economic performance, and (3) cultural ‘fit’. The analysis highlights how social markers of inter alia nationhood/race/religion, gender, sexuality and age shape assessments of both vulnerability and assimilability and thereby, which groups get to be seen as more deserving of access than others. By further developing promising victimhood as a concept, the article advances a more comprehensive understanding of deservingness and of the complex – gendered, racialised and age-differentiated – boundaries of inclusion and exclusion refugees face in today’s protection regime.

Introduction

Recent refugee movements to the European Union (EU), such as in 2015 or from Ukraine in 2022, put questions of access and deservingness centre-stage: Who is most deserving of access to protection and to a state’s territory, resources and membership? Who should be given priority and on which grounds? Critical observers of EU member states’ overall welcoming responses towards Ukrainian refugees for instance, have poignantly highlighted that it is not only people’s protection entitlements and vulnerabilities but also their supposed ‘fit’ with receiving states’ security, economic and cultural norms that play a role in answering these questions (Fallon Citation2022). European heads of states, some of which were among the hardliners in 2015 when Syrian refugees sought protection in the EU, highlighted not only Ukrainians’ suffering and protection needs but also their high educational level, added value for the economy and presumed like-mindedness to European societies due to shared ethnic and religious roots (cf. Abdelaaty Citation2022). These reactions thus also highlight how both perceptions of people's needs and vulnerabilities on the one hand and of their assimilability or ‘fit’ with receiving states on the other hand are linked to inter alia nationality/race/religion or other social markers (Bonjour and Chauvin Citation2018; Welfens Citation2021).

What crystallises in these discourses are the contrasting deservingness requirements that refugees and other humanitarian migrants are confronted with in Europe’s contemporary protection regime. In principle, refugees’ access to protection and membership in another state should depend on their protection needs and human rights, or be assessed based on humanitarian grounds in a non-discriminatory fashion. However, as recent refugee movements powerfully illustrate, perceptions of who is ‘most deserving’ of protection in Europe do not only hinge on refugees’ protection needs but also on their supposed ‘integration potential’. Where these humanitarian and assimilability requirements come together a tension emerges: in order to be seen as deserving of protection – by law or societal standards – refugees have to demonstrate that they are at risk in their countries of origin or first countries of refuge, yet willing and able to ‘overcome’ their vulnerability to become law-abiding, self-sufficient and culturally malleable future members of their host societies.

To conceptually capture these contrasting demands, that refugees and other humanitarian migrants are confronted with in today’s migration governance, this article harvests and advances the notion of ‘promising victimhood’ (Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas Citation2018). Building on scholarly work in the context of illegality studies (Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas Citation2014; Chauvin, Garcés-Mascareñas, and Kraler Citation2013), promising victimhood offers a fruitful lens to capture the policies and practices that require refugees to simultaneously demonstrate that they are currently in need of protection and/or particularly vulnerable, yet able and willing to integrate into the receiving society in the future, and not pose a risk to its security, economy or cultural norms. Thereby, the concept allows to theoretically grasp how contrasting deservingness conceptions and their translation into policies and practices interact and co-construct the complex boundaries of inclusion and exclusion refugees or other humanitarian migrants have to navigate.

I further develop the notion of ‘promising victimhood’ by exploring it in in the context of selection practices in refugee resettlement to Europe. Through resettlement and humanitarian admission programmes states in the Global North admit limited numbers of ‘particularly vulnerable’ refugees from first countries of refuge in the Global South (UNHCR Citation2011). According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), as places are scarce, deservingness and access to these programmes should depend on refugees’ vulnerability. Yet, as such programmes are discretionary policies and not codified in international law, states can apply additional selection criteria that assess inter alia refugees’ ‘integration prospects’ (Garnier, Jubilut, and Sandvik Citation2018; Mourad and Norman Citation2020). As a hybrid between humanitarian policies with a declared focus on the ‘most vulnerable’ and discretionary immigration control that allows to pick and choose refugees, refugee admission programmes are particularly apt to illustrate and further develop the notion of ‘promising victimhood’.

Against this background, I ask: How do vulnerability and assimilability criteria interact in refugee selection and thereby determine who counts as deserving of protection and safe access? In answering this question, I tease out three tensions between vulnerability and assimilability-related requirements: (1) vulnerability and security; (2) vulnerability and economic performance; and (3) vulnerability and cultural ‘fit’. By adopting an intersectional approach (Crenshaw Citation1991; McCall Citation2005), I show how both vulnerability and assimilability assessments are gendered, racialised, and age-differentiated and thereby crucially shape which groups count as more or less ‘victimised’ and/or ‘promising’ than others.

I contend that refugee resettlement is a particularly relevant context to study deservingness perceptions and subsequent requirements towards refugees or other humanitarian migrants, because of resettlement’s discretionary character. As resettlement is – in contrast to asylum – not codified in international law, admission states are relatively free in deciding whether, where from and whom to resettle (de Boer and Zieck Citation2020). Although officially such programmes claim to target particularly vulnerable refugees, admission states can and do formulate additional selection criteria in line with their security, economic and cultural interests (Mourad and Norman Citation2020; Brekke et al. Citation2021). As admissions are voluntary additional commitments, admission states can enact their policies in highly discretionary and partly secretive ways, without having to justify their practices and decision-making to refugees or other actors (Sandvik Citation2009; Menetrier Citation2021). Thus, in the wider context of mobility governance, resettlement programmes offer an important case to explore how states prioritise among refugees when given the possibility to select at the border.

My analysis focusses on European and in particular Germany’s refugee admission programmes, and draws on extensive qualitative research conducted between 2017 and 2022: semi-structured interviews, document analyses and observations of admission practices and practitioners’ events. Within Europe’s resettlement landscape, Germany has taken a trend-setting and leadership role in recent years and substantially shaped wider European policy developments in that area. In 2013 it has been the first European country to set up a humanitarian admission programme for Syrian refugees, which inspired other European states to follow suit and coordinate admissions on the EU level (Engler Citation2015). Germany has also been one of the driving forces behind the EU Turkey statement of March 2016 and related refugee admissions from Turkey, as well as behind the Common EU Resettlement Framework which is still under negotiation (Welfens Citation2022). In comparison to other European admission countries, Germany is among those that prioritise refugees not only on humanitarian grounds but also explicitly selects based on ‘integration potential’ and has comparatively strict security requirements (Brekke et al. Citation2021; Welfens and Bekyol Citation2021). Therefore, Germany’s admission programmes are particularly well-suited to illustrate how a focus on ‘promising victimhood’ materialises in selection practices.

The article’s structure is as follows. I start by theoretically developing the concept of ‘promising victimhood’ for the context of refugee resettlement. I then synthesise how refugee resettlement works in practice and outline my research approach. The subsequent analysis highlights the tensions between vulnerability and assimilability requirements in the selection process and which social groups the combination prioritises and marginalises within refugee populations.

Theorising promising victimhood in the context of refugee resettlement

Scholarship on refugee and migrant deservingness has shown how discourses, policy and practices create hierarchies between and within groups of mobile populations and stratify people’s access to resources (Anderson Citation2013; Holmes and Castañeda Citation2016; Ratzman and Sahraoui Citation2021). In the context of refugee and migration governance, these can be material resources such as shelter or food, symbolic resources such as a particular migration status and the social ‘standing’ that comes with it, or emotional resources such as compassion or trust (Massey Citation2008; Mügge and van der Haar Citation2016). Scholarship has highlighted for instance how perceptions of deservingness shape access to mobility, protection and legal status, as well as reception and assistance practices for refugees or other migrants (Chauvin, Garcés-Mascareñas, and Kraler Citation2013; Ravn et al. Citation2020).

At its core, the question of refugees’ or migrants’ deservingness is a question about how or on which grounds to select when access is – supposedly or de facto – limited. In such settings, states or other actors enforcing migration control on their behalf, have to formulate categories to prioritise in policies and at the frontline, and justify their priorities vis-à-vis their constituencies or refugees and migrants. Therefore, policy categories and how they are put into practice at the frontline, such as in refugee selection for resettlement, provide insights into deservingness perceptions (Welfens Citation2022). Yet, deservingness perceptions and their enactment in policies are also always context-specific and can change over time. As Yanow and van der Haar (Citation2013, 232) remind us, categories are ‘created by people at particular moments in time and inscribed onto [the] world in order to make sense of or bring order to it’.

Research on migrant and refugee deservingness has identified different dimensions of deservingness. Scholars have shown how in particular refugees’ and other humanitarian migrants’ deservingness hinges on human rights or humanitarian deservingness frames or rationales. The former, human rights rationales, deem those particularly ‘worthy’ that fulfil certain legal requirements, such as the grounds that qualify someone for international protection as formulated in the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention. Humanitarianism in contrast rests on a ‘politics of compassion’ that orders based on people’s vulnerabilities and suffering (Fassin Citation2012). What connects human rights-based and humanitarian rationales is that deservingness depends on (would-be) refugees’ needs and (potential) harm they experienced in the past, or experience at present.

Focussing more squarely on migrants and immigration policies, scholarship has also identified ‘integration prospects’ as a key deservingness rationale (e.g. Bonjour and Duyvendak Citation2017). Integration, or assimilability, has two interrelated aspects to it: deservingness due to cultural ‘fit’ or cultural integration, and deservingness based on economic performance (Chauvin, Garcés-Mascareñas, and Kraler Citation2013; Bonjour and Chauvin Citation2018). The former deems particularly those migrants as worthy of membership – and in the context of resettlement, protection and territorial access – that demonstrate a (prospective) cultural fit with a state’s community and values. The latter, economic performance, prioritises those that live up to the ideals of today’s neoliberal markets: self-sufficient, hard-working employees of the formal economy. However, especially in contexts where work ethics are also seen as a central part of civic culture, cultural and economic performance becomes inseparable (Chauvin, Garcés-Mascareñas, and Kraler Citation2013; Bonjour and Chauvin Citation2018).

Another deservingness rationale, closely connected to integration, is security. The extensive literature on how migration has been ‘securitised’ in discourses and policies, has teased out different ways in which mobile populations can be perceived as more or less ‘risky’ and subsequently more or less ‘deserving’ of access (for an overview see Huysmans and Squire Citation2009). Migrants can be seen as a potential threat to public security (migrants as criminals or terrorists), the economy (migrants as competitors on the job market and illegitimate welfare recipients) and cultural order (migrants’ norms and practices being at odds with liberal norms) (Huysmans Citation2000; Fassin Citation2012). In essence, security concerns and integration expectations can be understood as two sides of the same coin: to not become a threat to a receiving state’s public, cultural and economic security, newcomers are expected to integrate well with regard to these three dimensions – to be law-abiding, economically self-sufficient and culturally malleable. To summarise integration and security related rationales I therefore use the term assimilability.

In today’s migration and refugee governance, what makes a person deserving and supposedly ‘worthy’ – of access, legal status or compassion – has become complex and multi-layered (Ravn et al. Citation2020). Scholarship has started to address this by highlighting that migrants and refugees can be confronted with multiple and sometimes contrasting requirements, such as vulnerability and civic integration demands (Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas 2014, 426):

On the one hand, in an era of increasing criminalization of migration, the good candidate for asylum has seemingly become the one who would have preferred not to migrate but has come or stayed due to exceptional circumstances associated with vulnerability. […] On the other hand, restrictionist policies have also tended to define deserving migrants as those who can demonstrate their integration and contributions as residents.

It is this specific combination of vulnerability and assimilability selection criteria that make resettlement programmes a fertile ground for the occurrence and illustration of the concept of ‘promising victimhood’ (Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas Citation2018). Embedded in the larger debate on migrant deservingness, the concept denotes the contrasting demands in policies and practices that require migrants to demonstrate that they are currently in a situation or state of suffering, vulnerability or victimisation, while at the same time being willing and/or able to ‘overcome’ their vulnerability to become active, self-reliant members of their host societies in the future.

Research on critical humanitarianism as well as on civic integration has shown how both of these dimensions – vulnerability and assimilability – are racialised, gendered, classed as well as age-differentiated. For instance, scholars of critical humanitarianism have shown how policy categories and frontline assessments operationalise vulnerability along the lines of inter alia gender, age, nationality, ethnicity, economic and legal status (Sözer Citation2019; Turner Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Welfens and Bonjour Citation2021). In such assessments, some groups – in particular ‘womenandchildren’ (Enloe Citation1990) but also elderly people for instance – are seen to be per se more vulnerable than others. Inversely, men – especially when they are (read as) young, able-bodied, single and heterosexual – are seen as per se not vulnerable (Turner Citation2019a, Palillo 2022). In a similar vein, scholarship on civic integration policies has highlighted how intersections of nationality, race, religion, gender and age matter to designate the target groups of civic integration policies, or to define whose integration performance counts as particularly problematic (Mügge and van der Haar Citation2016; Bonjour and Duyvendak Citation2017; Roggeband and van der Haar Citation2018).

Drawing on these insights, I adopt an intersectional understanding of the notion of promising victimhood. Originally developed by Black feminist theorists in the US (Crenshaw Citation1991; Hill Collins Citation1998), intersectionality describes the idea that different social markers such as gender, nationhood, race, age and social class do not operate in isolation but interact and create contingent positions of privilege and marginalisation. Applied to the notion of promising victimhood, intersectionality renders visible how its two central elements – vulnerability and assimilability – are shaped by intersecting identity makers. Thereby, an intersectional approach also highlights which groups count as more or less deserving in a given context and, in refugee resettlement, who gets access to safe pathways and protection. The following section will provide an overview of how refugee selection works in practice.

Setting the scene: selection practices in refugee resettlement

Refugee resettlement and similar active refugee admission programmes allow select individuals or groups to safely and legally transfer from a country of refuge (e.g. Turkey) to an admission country (e.g. Germany), where they receive temporary or permanent protection (UNHCR Citation2022b). According to the UNHCR (Citation2011), resettlement offers one of three durable solutions for refugees, besides integration and voluntary repatriation. Further, next to providing permanent or temporary protection to admitted refugees, resettlement and similar admission programmes aim to signal solidarity to first countries of refuge and, ideally, incentivise them to keep their borders open and/or to provide better support to refugees they already host (van Selm Citation2013; Schneider Citation2020).

In principle, as numbers are scarce, only ‘the most vulnerable’ refugees should be prioritised for resettlement. To this end, the UNHCR (Citation2011) has formulated ‘resettlement submission categories’, which it applies in its own assessments: legal and physical protection needs; survivors of torture and/or violence; medical needs; women and girls at risk; family reunification; children and adolescents at risk; lack of foreseeable alternative solutions. However, as resettlement is not a codified right but a discretionary extra commitment, admission states are free to define own selection criteria and discretionarily enact them at the frontline (Garnier, Jubilut, and Sandvik Citation2018).

This discretionary way of admitting refugees has gained considerable popularity among European states. While for a long time only four EU Member States resettled on a regular basis – the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark and Finland (Van Selm Citation2004), the number increased to nineteen EU countries in 2019. This also led to a significant increase in total resettlement arrivals to Europe from 11.175 in 2015 to 29.066 in 2019, right before admissions to Europe and globally were heavily disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic (UNHCR Citation2019). Due to significant cuts in US resettlement under the Trump administration, this increase in admission capacities to European states, made Europe an important resettlement actor who accounted for 40–55 percent of resettlement spots worldwide in the years between 2017 and 2020 (UNHCR Citation2020). Yet, European and other states’ resettlement efforts can only cover a tiny fraction of the global resettlement need, which UNHCR estimates to be over 2 million for 2023: of the 1,47 million people in need of resettlement in 2022, only around 63.000 could be resettled (UNHCR Citation2022a).

Within the European resettlement landscape, Germany as an admission country and Turkey as a country of first refuge are particularly relevant. With around 9500 refugee arrivals in 2019, Germany accounts for 28 percent of admission places in Europe and thereby – in absolute numbers – heads the list of European resettlement states (UNHCR Citation2019). As a consequence of the EU-Turkey statement of 2016, in which the EU promised to admit refugees via humanitarian admission programmes in exchange of Turkey stepping up its border control, European states shifted their resettlement efforts towards Turkey as a country of first refuge.

These admission programmes ‘made in Europe’ (Fratzke and Beirens Citation2020), which take inspiration from established resettlement countries like the US but also have their distinct features, have mostly been studied with a focus on policy making, such as states’ motivations to set up programmes (Beirens and Fratzke Citation2017; Armbruster Citation2019; Welfens Citation2022), or official selection criteria (Mourad and Norman Citation2020; Brekke et al. Citation2021). Less attention has been paid to how programmes are put into practice at the frontline, in particular with a view on the interaction between different resettlement actors – NGOs, UNHCR, admission countries and countries of first refuge – and their respective selection logics in the complex admission process (but see also Welfens and Bonjour Citation2021; Menetrier Citation2021).

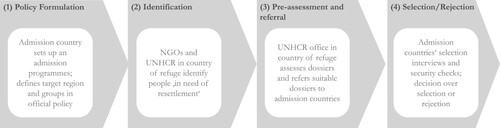

This process of selecting refugees for resettlement and related programmes can be conceptualised as a transnational ‘admission chain’ (Welfens Citation2021) with a variety of steps and actors involved, as illustrates. In reality, the process is usually less linear, dossiers travel back and forth, get stuck or drop out along the way.

Figure 1. Selection process in refugee admission programmes, based on Germany’s humanitarian admission prorgrammes from Turkey.

First, a state decides to set up an admission programme and formulates its policy and selection priorities, usually in coordination with UNHCR. This sets in motion the actual admission chain. To select refugees, admission states rely on the cooperation with UNHCR offices, UNHCR’s partner NGOs and – in some cases – state institutions in the country of refuge. Usually, it is UNHCR and NGOs in the country of refuge that identify vulnerable refugeesFootnote1 ‘in need of resettlement’, who are then referred to UNHCR’s resettlement unit. UNHCR further assesses people’s vulnerabilities and resettlement needs and submits a selection of dossiers it considers eligible to admission countries. State officials from admission countries in turn select from this pool of submissions either based on the dossier alone or an in-person interview. As part of their selection interviews or as a distinct step in the process admission states also run security screenings.

In this process, UNHCR strives to prioritise based on humanitarian principles, whereas admission states may also prioritise based on refugees’ assumed assimilability. Assimilability-based selection can be explicit in official admission policies, e.g. in the form of ‘integration-potential’ or ‘integration capacity’ selection criteria, or be a more implicit part of admission states’ practices (Mourad and Norman Citation2020; Brekke et al. Citation2021). As refugee selection remains the discretionary decision of admission states, UNHCR has to partly comply with or anticipate on admission states’ assimilability-based selection. In combination, as the following analysis will show, these two contrasting selection principles produce tensions and at times paradoxical requirements towards refugees.

Methods and research approach

The following analysis draws on in-depth qualitative research on refugee resettlement to Europe, conducted between 2017 and 2022. The research focussed on Germany’s humanitarian admission programmes from Lebanon (2013–2015) and from Turkey under the EU Turkey statement of March 2016 (since 2017) as part of a wider developing European resettlement landscape. Germany’s programmes are prime examples of refugee admissions in reaction to the Syrian war and subsequent displacement before and after Europe’s long summer of migration in 2015. The research aimed to study categorisation practices in official policies and frontline enactments along the entire ‘admission chain’, from refugee selection and pre-departure trainings in countries of refuge (Turkey and Lebanon in this case) to refugee reception in the admission country (here, Germany). To this end, I have used a triangulated methodology, including document analyses, over 80 semi-structured interviews with key resettlement actors and observations of frontline practices and practitioner events.

The analysis is based in particular on my interviews with UNHCR Lebanon and Turkey, interviews with German state representatives and frontline migration officers, as well as observations of practitioner events in Germany (2018–2022) and of frontline practices of UNHCR Turkey (November 2019). Secondary literature on selection practices in European programmes complements the analysis. The project as a whole has been reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the University of Amsterdam and for observations of UNHCR Turkey’s practices, refugees’ have been informed about who I am and asked for their oral consent.

Taking inspiration from interpretive policy analysis (e.g. Verloo Citation2005), I have analysed documents, interview transcripts and fieldwork notes with respect to four aspects: (1) what is seen to be the policy problem, e.g. too many people in ‘in need of resettlement’ for too few places; (2) what is seen to be an appropriate solution, e.g. prioritising based on humanitarian criteria/expected economic performance/cultural fit; (3) how do assessment practices draw on social markers such as gender, nationhood, religion, sexuality or age; and (4) which groups get to be seen as deserving or undeserving. The following analysis presents the results with a focus on Germany’s admission programmes from Turkey.

Analysis

Resettlement and humanitarian admission programmes claim to target ‘particularly vulnerable’ or ‘the most vulnerable refugees’. Indeed, UNHCR’s and NGOs’ vulnerability assessments at the beginning of the selection process are the key criterion to identify people who are ‘in need of resettlement’ because they continue to be at risk in the country of refuge or have needs that cannot be addressed there. However, as the following analysis highlights, in all subsequent steps along the process from UNHCR’s pre-assessment and submission to admission states’ selection interviews it is not only refugees’ vulnerability but also their assimilability – with regard to security, economic performance and cultural fit – that gets assessed in an anticipatory fashion. The combination of these contrasting and at times paradoxical requirements favours those deemed to be ‘promising victims’: people that are seen to be currently vulnerable yet willing and able to overcome their vulnerability and be self-sufficient, law-abiding, culturally malleable future members of their new host societies.

Vulnerability – security

The first tension between resettlement programmes’ declared focus on refugees’ vulnerability and admission states’ assimilability-based selection relates to security. As admissions are a discretionary and in principle additional commitment of admission states, they have a strong interest to make sure the persons they actively bring to their territory do not pose a threat to national security.

In the global refugee protection regime, as well as in resettlement, the baseline for security-related exclusion is Article 1F of the Geneva Refugee Convention. It states that the Refugee Convention should not apply to persons who have ‘committed a crime against peace, a war crime, or a crime against humanity’, a ‘serious non-political crime outside the country of refuge’, or have ‘been guilty of acts contrary to the purpose and principles of the United Nations’ (UNHCR Citation2003). Excluding these cases early on in the process is considered central to protect both admission countries against potential harm and UNHCR’s legitimacy as an international organisation (IO). The Resettlement Handbook states that ‘to protect the integrity of UNHCR’s resettlement procedures, it is essential that possible exclusion issues are carefully examined, and eligibility for international protection under the Office’s mandate is confirmed before an individual case is submitted for resettlement’ (UNHCR Citation2011, 101). In its more generic chapter on ‘The evolution of resettlement’ the handbook also notes that ‘[i]n response to concerns about terrorism, some States are interpreting and applying the definition of a refugee more restrictively, particularly with respect to the exclusion clauses’ (UNHCR Citation2011, 69). Identifying those who are at risk but not risky thus works to both protect UNHCR’s integrity and authority as the IO resettlement expert, and protect admission states from potentially dangerous individuals.

UNHCR tries to address or anticipate admission states’ security-related selection practices early on in the process and thereby partly goes beyond the Article 1F baseline for exclusions. Already during the pre-assessment frontline workers ask about the existence of documents such as identification documents, the family booklet, birth and death certificates, and the military booklet. Determining the family composition with the help of these documents – who belongs to the family, whether all family members are in Turkey and possess identification documents – not only serves UNHCR’s humanitarian aim to protect family unity, but also addresses admission states’ document requirements in an anticipatory fashion. For admission countries, establishing refugees’ identity and cross-checking it against European data-bases is one way to pre-empt that selected refugees do not pose a threat to admission countries’ security. In this logic, presence of identity documents and a cleared security profile with respect to the time in Syria and the country of refuge, work as a proxy for a promising attitude towards law-abiding behaviour in the admission country.

Such document requirements can be and often are in tension with the declared focus on ‘particularly vulnerable’ or ‘the most vulnerable’ refugees, when their absence amounts to a de-facto exclusion criterion. Germany’s requirements are particularly strict in this regard (Observations UNHCR Turkey Citation2018; Observations Resettlement Expert Meeting Citation2019). For its admissions from Turkey, Germany only accepts cases in which all family members above 15 provide a Syrian identity document, valid or expired. According to Syrian registration law, everyone above 15 is entitled to an ID card or passport. In principle, the latter is needed to cross the border between Syria and Turkey. Those refugees who did not take their documents with them, lost them, or turned 15 after their arrival to Turkey, would need to apply for documents at the Syrian consulate in Istanbul. However, this option is not available to everyone. For reasons of political persecution or just general fear of the encounter with Syrian state representatives, people might decide against obtaining their documents to have their resettlement case processed further. Others do not have the financial means to pay for repeated trips to Istanbul, the issuance fee, plus the fees for brokers who help to get an appointment (Enab Baladi Citation2018).

‘Promising victimhood’ here consists of the paradoxical requirement of being particularly vulnerable in order qualify for resettlement, including fears of persecution in the country of refuge, yet being financially and psychologically able to apply for new documents from the government people fled. This paradox has concrete implications for refugees’ access to protection. In Germany’s admission programmes from Turkey the duality of vulnerability and security-related document requirements leads to a situation in which UNHCR – forced to comply with Germany’s high document standards – cannot submit enough dossiers to fill the maximum monthly quota of 500 (Observations Resettlement Expert Meeting Citation2019).

However, refugee resettlement ‘candidates’ are not all subject to the same level of scrutiny, as security assessments are gendered and age-differentiated. Focusing predominantly on men around or above recruitment age, security practices rely on gendered assumptions, associating men with violence and the public sphere, and women with peace, family and the private sphere. In UNHCR Turkey’s pre-assessments via phone for instance, it is mainly the information contained in Syrian male applicants’ military booklet that can give reason to ‘de-prioritise’ a dossier early on in the process. A military booklet gives evidence about male applicants’ military activities, like the two-year military service that all Syrian men have to complete after high school. Everything that concerns the time before the beginning of the war in 2011 usually counts as unproblematic because it applies to almost everyone. Military activities in the time after March 2011 can lead to de-prioritisation of a case. UNHCR keeps the exact exclusion categories in a confidential ‘Syria de-prioritisation’ file. It is likely that the criteria resemble the ones that UNHCR Lebanon reports applying, i.e. higher-rank military active post-March 2011; members of paramilitary and militant groups like People’s Army, Free Syria Army, Islamic State, Jabhat Al-Nusra; informants, unless forced into it through torture; and staff working in detention facilities (UNHCR Lebanon 2015; Janmyr Citation2016). Also in the in-person interview security-related questions focus mostly on male applicants above or close to recruitment age, whereas the accounts of female family members mainly serve to confirm and triangulate this information.

Taken together, with regard to security refugees are seen as particularly ‘promising victims’ when they fulfil a dual requirement of riskiness: to be considered deserving and formally eligible for resettlement refugees have to demonstrate that they are vulnerable and at risk but at the same time ‘non-risky’ for European admission countries in the future (cf. Aradau Citation2004; Pallister-Wilkins Citation2015). The pre-emptive criteria and practices of European admission countries, such as Germany, can be particularly challenging for some of the most vulnerable groups, and target male refugees above recruitment age disproportionately. Yet, only those who fulfil this dual requirement of being vulnerable and ‘non-risky’ stand a chance to be selected.

Vulnerability – economic performance

Another combination of contrasting requirements towards resettlement candidates relates to their economic situation in the country of refuge and their economic prospects in admission countries.

In NGOs’ and UNHCR’s vulnerability assessments socio-economic criteria, including self-reliance, are key to identify people with a ‘resettlement need’. According to UNHCR’s resettlement handbook, where refugees’ income is ‘below the minimum wage of local daily labourers in the host country’ this indicates limited local integration prospects and where living conditions, including access to work, are worse ‘to those refugees in other countries within the region, resettlement should be maintained as an option’ (UNHCR Citation2011, 292). Related categorisation systems often rely on gendered pre-assumptions about male adults being the principal breadwinners while adult women count as economically dependent (Welfens and Bonjour Citation2021). In practice, for men and women, financial hardship alone often does not suffice to be considered for resettlement as it usually applies to too many refugees (Observations UNHCR Turkey Citation2018).

Whereas economic dependence and the absence of self-sufficiency in the country of refuge is a key criterion to count as vulnerable and potentially ‘in need of resettlement’ in the eyes of NGOs and UNHCR, some admission countries demand the opposite once refugees resettle. Refugees potential or capacity to become self-sufficient – inter alia through a pro-active attitude in their job search or learning the language – is one way for admission countries to assess refugees’ ‘integration potential’ (Brekke et al. Citation2021). A number of admission countries explicitly lists educational training, work experience and knowledge of the language in its admission policies (Mourad and Norman Citation2020). Germany for instance, uses education and work experience to operationalise the broad term of ‘integration potential’, which the country applies in its resettlement and humanitarian admission programmes. The policy lists ‘knowledge of the language’ next to ‘family ties’ as examples for ‘factors that facilitate integration’, including labour market integration. In previous admissions from Lebanon, Germany had used the priority criterion of ‘skills for reconstructing Syria after the end of the conflict’, which German state officials justified as a long-term humanitarian objective, whereas others saw it as a camouflaged attempt to target highly-skilled refugees (Welfens Citation2022).

Officially, as the global resettlement expert and watchdog over resettlement’s humanitarian objectives, UNHCR rejects ‘integration potential’ criteria in general (Garnier Citation2014), and skills, education, and work experience in particular. For instance, Volker Türk, at the time UNHCR’s Assistant High Commissioner for Protection, phrased his critique of skills-based integration criteria as follows (UNHCR Citation2017):

The critical protection and life-saving function of resettlement for the most vulnerable individuals risks giving way to pressures to resettle individuals with ‘integration potential’ – as if language, education, or professional skills make one more deserving than those who are at the greatest risk of harm. To guard against this slippage, resettlement programmes need to be anchored in protection and solutions strategies.

We also have requests for refugees who have capacity to work. We are asked for certain numbers of breadwinners within a refugee group and that puts additional pressure on us to identify cases because we are looking for protection needs.

The contrasting demands this produces make UNHCR’s task to preselect refugees often challenging and sometimes impossible. Norway for instance, requested in previous guidelines (2015–2020) ‘that in the selection of persons above the age of 18, those with education and vocational experience with relevance for the Norwegian labour market shall be given priority’ (Brekke et al. Citation2021). After UNHCR found it challenging to submit cases that fitted both the vulnerability and these integration criteria, the integration requirement was dropped for ‘families with children and women in a vulnerable situation’, yet not for single men (Brekke et al. Citation2021). Thus, also economic performance criteria draw on and reproduce gendered and age-differentiated inequalities. For refugee women and children their per se vulnerability ‘exempts’ them from employability considerations. Children in particular, as the next section shows, are seen to be ‘made employable’ and socialised into the ‘right’ work ethic once they are admitted. Refugee men, however, who are generally considered not vulnerable, need to ‘earn’ access to admission programmes through a promising employment profile. Like in civic integration policies more broadly, making access and belonging dependent on (some) refugees’ employability and work ethics, implicitly depicts European societies as ‘middle-class, hardworking, highly modern and progressive ‘communit[ies] of values’ (Anderson Citation2013)’ (Bonjour and Duyvendak Citation2017), supposedly in stark contrast to refugees’ places of origin and own culture.

In sum, in its economic dimension ‘promising victimhood’ relates to the dual requirement to be economically deprived in the country of refuge while showing ability and willingness to become self-reliant and employable once admitted to resettlement countries. To which extent this dual requirement applies differs by gender and age, a differentiation that also structures the cultural dimension of ‘promising victimhood’, which I examine in the next section.

Vulnerability – cultural fit

The third tension between resettlement’s declared focus on the ‘most vulnerable’ and assimilability relates to pre-emptive assessments of refugees’ cultural ‘fit’. Next to economic integration requirements, cultural integration criteria are usually part of what admission countries call ‘integration prospects’ or ‘integration capacity’ in their admission policy.

Officially, UNHCR has already for a long time rejected integration-related criteria, especially in their culturalised dimension. However, just like with other assimilability criteria that come to matter at the frontline of admission states, UNHCR has to partly anticipate on this selection criterion or applies similar criteria but for different reasons. Where UNHCR frontline workers deem refugees’ ‘integration prospects’ to be insufficient, they might decide against submission to an admission programme. This can be either because UNHCR workers expect the dossier to be excluded due to lack of ‘integration potential’ by admission states and therefore give priority to a dossier they anticipate to have higher chances. Or, if refugees too explicitly show their rejection of certain changes and norms UNHCR might also decide to not submit a dossier, claiming that ‘then it is better for both sides’ – meaning the refugee and the admission country. The examples frontline workers refer to for such an attitude are people who declare to not be willing to learn the language of admission states, to work, or to share accommodation with refugees of other nationalities (Observations UNHCR Turkey Citation2018). In both instances, UNHCR uses assimilability criteria in a pre-emptive way to ‘de-prioritise’ dossiers pre-selected for their vulnerability from the selection process.

While refugees’ assumed ‘best interest’ may be one reason for such practices, the probably more important one is admission states’ assessment of ‘integration potential’ in their selection interviews. As admissions are not regulated by international law and negative decisions do not have to be justified – vis-à-vis the refugee, UNHCR, or the interested public – admission states’ are free to define and implement such criteria in highly discretionary ways and the practices of most countries are not transparent.

However, the examples German state officials as well as officials from other admission states refer to as an illustration of how they assess ‘integration potential’ – even when it is not an official selection criterion – are questions about norms and values, especially in the realm of child rearing, gender equality and sexuality (Brekke et al. Citation2021; Welfens and Bonjour Citation2021). As a high-level official from the German Ministry of the Interior explains (Observations German Resettlement Expert Meeting Citation2018):

The most important criterion for us is the UNHCR-assessed resettlement need. And for everything that follows, we are in a situation where there is more need than capacity. So this poses the question whether you have additional criteria or not. […]. For us, this is about identifying whether there are people where we do not see any integration capacity at all. […]. To make it concrete: if there is for instance a family who thinks that girls should not be allowed to go to school, this would be a situation for us where we say, the demand is so high, we would rather take another family.

It is through these particular questions that the contrasting requirements of ‘promising victimhood’ (Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas Citation2018) materialise: refugees have to be vulnerable now, while at the same time showing a promising attitude with regard to their future integration and moral citizenship prospects. They need to prove to be vulnerable while at the same time willing and able to become the proactive and culturally open-minded newcomer Western states’ civic integration policies envisage (Joppke Citation2007; Bonjour and Duyvendak 2017). Similar to other ‘integration from abroad policies’, (FitzGerald et al. Citation2017), in Germany’s and other admission states’ selection practices, refugees’ cultural ‘fit’ is tested long before refugees actually reach admission states’ territories. Formal membership – access to admission programmes, temporary residency and in the long run permanent residency – becomes dependent on refugees’ anticipated prospects of moral membership, i.e. whether they can live up to the standards of what ‘a good citizen’ or a ‘good newcomer’ is and does (Schinkel and Van Houdt Citation2010).

Based on assumptions of patriarchal and archaic gender roles in Syria, or predominantly Muslim countries in general, the primary subject of cultural ‘integration capacity’-related questioning appears to be the family’s father. Questions about gender equality and child rearing suggest that admission countries seek to ensure that male refugees do not pose a threat to the national (gender) order. They align with a broader discourse on the sexually deviant racialised ‘other’, that allegedly poses a threat to women and children within their own and receiving societies (Yurdakul and Korteweg Citation2021). In such racialised assimilability assessments heterosexual young refugee men are seen as neither vulnerable nor particularly ‘promising’ with regard to assimilability.

Inversely, admission states’ official selection categories and frontline assessments suggest that some groups’ victimhood counts as per se more promising than others’. A relevant social marker in that regard is age in its intersection with nationality/race/religion, and gender. In vulnerability assessments of state and non-state actors just like in humanitarian policies more widely (Baughan Citation2021), displaced children count as a clearly vulnerable group and therefore as primary targets of admissions. As a German state representative of the Federal Ministry of the Interior explains (EKM Citation2014):

Especially children are part of the particularly vulnerable, because they are particularly affected by displacement and the consequences of the war. They do not only suffer psychologically and physically disproportionately, but also their educational biographies get interrupted, so that their humanitarian admission is worthwhile for a lifetime.

[Children are the group] to whom you can still offer a perspective when they are here. They go to childcare facilities, to schools, do their job training, study. […] With [children] you do not have integration problems; when they go to schools and kindergarten here, they grow up in this environment. Someone who is 50, 60, let’s say with grown traditions […], which are not compatible with our way of life, this is difficult. […] Children grow into this. If you could neutralise the children – in other words, ignore their physical appearance — nobody would know where they came from.

While children count as per se deserving and desirable from the viewpoint of admission states, the category of gender draws further intra-categorical divisions of deservingness within this group. Concretely, in the past, Germany as an admission country has shown a preference for unaccompanied girls over boys. In EU-internal relocations from the Greek islands, the German government sought to prioritise children, who either had urgent medical needs or were unaccompanied and below 14, ‘most of them girls’ (CDU Citation2020). In practice, however, this prioritisation could not be realised as only 7.5 percent of unaccompanied minors in Greece were below 14 and only a small fraction of them female (B-UMF Citation2020). The rationale of this gendered prioritisation among children is rarely made explicit by state representatives. However, it is likely that the same racialised and gendered stereotypes that make refugee women appear to be more deserving of admission, and refugee men to be a risk to admission states (gender) order also apply to minors to some extent (Yurdakul and Korteweg Citation2021).

Such racialised perceptions of refugee men are intrinsically connected with religion – another social marker that crucially shapes perceptions and assessments of refugees anticipated ‘promising victimhood’. In the context of Germany’s admissions from Turkey, ‘religion’ was until 2020 one of the criteria to define ‘integration potential’ in the official policy. Already at the time of Germany’s first admission programme for Syrians in 2013, then minister of the interior Hans-Peter Friedrich announced that the programmes would inter alia focus on ‘Christians’, as they were at particular risk of persecution. After intense criticism both in Germany and in Lebanon, the official admission policies spoke of ‘members of religious minorities with religion-specific persecution’ (Welfens Citation2022). Officially, the justification is that Christians are supposedly more at risk of persecution and violence in the respective conflicts, although human rights organisations and their reports do not support this claim. Only few make another justification for prioritising Christians explicit, namely the expectation that they will better integrate as their norms and values are supposedly more aligned with the receiving society (Patrick Citation2017).

In sum, despite UNHCR’s and other resettlement actors’ resistance, integration-based selection criteria and practices are a central element in assessing refugees’ deservingness and eligibility for admissions, with some groups counting as per se better able to integrate and adapt than others. The way in which assessments of vulnerability and cultural fit draw on inter alia gender, race/nationhood/religion and age makes women and children, especially girls, appear to be particularly ‘promising victims’, whereas refugee men – especially when read as Muslim, young, heterosexual and able-bodied count as neither vulnerable nor culturally assimilable.

Conclusion

This article aimed to conceptually grasp and empirically scrutinise the duality of vulnerability and assimilability demands towards refugees and the complex boundaries of inclusion and exclusion they produce.

Empirically, the article deployed the notion of promising victimhood (Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas Citation2018) in the context of refugee resettlement to highlight how refugees’ deservingness of admission to another state hinges on both vulnerability and the prospect of assimilability. The analysis has teased out the tension between vulnerability and three dimensions of assimilability – security, economy and cultural ‘fit’, while highlighting the interrelatedness of the three. In particular, considerations of economic and cultural ‘fit’ are closely intertwined as ‘employability’ of refugees is not only assessed based on formal qualifications but also racialised notions of work ethics and attitudes. The empirical focus on admissions to the German programme, with explicit integration-related and comparatively strict security criteria, makes a ‘promising victimhood’ selection rationale more likely, and some of the related tensions stronger than they might be in programmes that stick more to UNHCR’s humanitarian baseline. Exploring the concept of ‘promising victimhood’, including the relative importance of the three tensions described, in the context of other admission programmes and comparative work constitutes a promising avenue for future scholarly work.

The analysis has also highlighted which groups the contrasting requirements favour or marginalise in the selection process. Young, single refugee men generally count as not vulnerable and least ‘promising’ with respect to the different assimilability dimensions. In contrast, women and even more so children of young age are generally seen as clearly vulnerable – due to displacement and being ‘at risk’ within their own culture – and particularly ‘promising’ new members to admission states’ societies. Thus, some groups (supposedly) live up to the dual requirement of ‘promising victimhood’, while others are considered to be per se only vulnerable or assimilable, or neither nor. To scholarship on migrant deservingness in general and in refugee resettlement in particular, these findings contribute an intersectional understanding of deservingness that highlights the temporality of deservingness requirements. The intersectional lens makes visible how social markers of gender, nationhood/race/religion and age structure both assimilability and vulnerability assessments and thereby put some groups on the top of the hierarchy and others at the bottom. Highlighting the temporal dimension of contrasting deservingness requirements renders visible how refugees, while still being in the country of refuge, have to demonstrate their current victimisation but future potential to change their circumstances and/or norms and values.

On a theory level, the article has further advanced the notion of ‘promising victimhood’, coined by Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas (Citation2018), as a fruitful concept to capture the fusion of humanitarian and civic integration rationales and the resulting dual demands of vulnerability and assimilability towards refugees. The concept moves beyond a binary understanding of deservingness and subsequent access hinging on either vulnerability or assimilability, by showing that often it is the combination of both that constitutes deservingness in the eyes of admission states and institutions acting on their behalf: a verifiable or ostensible vulnerability at the moment of assessment combined with what admission states’ consider to be signs of low riskiness and good integration prospects. On the level of theory, this article has demonstrated that different deservingness rationales are promoted by different actors within the policy process and shaped by the power relations between these actors. In the context of resettlement, UNHCR and NGOs seek to prioritise and select based on vulnerability, whereas admission countries also select based on assimilability. In the context of a discretionary policy like resettlement, admission states relative power vis-à-vis UNHCR and their final say in the admission process crucially shape the dual-requirements refugees have to fulfil in order to stand a chance to be resettled.

For refugees themselves these dual requirements of ‘promising victimhood’ have important implications. The contrasting requirements – especially in a highly discretionary process with multiple actors involved, such as resettlement – create confusion for refugees as to how to ‘correctly’ reply and which narratives to foreground when. Whereas scholarship on resettlement has shown refugees’ strategies to navigate and ‘perform’ UNHCR’s vulnerability criteria (e.g. Jansen Citation2008; Menetrier Citation2021), the combination of vulnerability and assimilability criteria in a whole series of interviews makes it much more challenging for refugees nowadays: at the beginning of the selection process they need to foreground their dependency, precariousness and helplessness to be considered ‘in need of resettlement’; the closer they come to admission states’ frontline the more they also need to demonstrate capacities to become pro-active, independent and emancipated. How exactly refugees navigate the contrasting requirements in the selection process lies beyond the scope of this article, but offers a promising and critical avenue for future research.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the participants of the Interdisciplinary Seminar in Empirical Social Science (ISESS) of the University of Warsaw, the participants of the Hertie Centre for Fundamental Rights research colloquium, all RefMig team members as well as Saskia Bonjour and Sébastien Chauvin for their helpful and encouraging comments and suggestions. A special thanks goes to my writing group fellows Tasniem Anwar, Linet Durmuşoğlu, Anneroos Planqué-van Hardeveld and Anne Louise Schotel.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In admission programmes from Turkey, the Turkish Directorate General for Migration Management (DGMM) identifies refugees with 'resettlement needs' and checks all resettlement submissions to UNHCR. However, in this article the focus lies on UNHCR's and resettlement states' selection practices.

References

- Abdelaaty, Lamis. 2022. “European Countries are Welcoming Ukrainian Refugees. It was a Different Story in 2015.” Washington Post. Accessed 25 March 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/03/23/ukraine-refugees-welcome-europe/.

- Anderson, Bridget. 2013. Us and Them? The Dangerous Politics of Immigration Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Aradau, Claudia. 2004. “The Perverse Politics of Four-Letter Words: Risk and Pity in the Securitisation of Human Trafficking.” Millennium: Journal of International StudiesJournal of International Studies 33 (2): 251–277.

- Armbruster, Heidi. 2019. “‘It Was the Photograph of the Little Boy’: ‘Reflections on the Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Programme in the UK’.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 46 (16): 2680–2699.

- Baughan, Emily. 2021. Saving the Children. Humanitarianism, Internationalism, and Empire. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Beirens, Hanne, and Susan Fratzke. 2017. Taking Stock of Refugee Resettlement. Policy Objectives, Practical Tradeoffs, and the Evidence Base. Brussels.

- Boer, Tom de, and Marjoleine Zieck. 2020. “The Legal Abyss of Discretion in the Resettlement of Refugees.” International Journal of Refugee Law 32 (1): 54–85.

- Bonjour, Saskia, and Jan Willem Duyvendak. 2017. “The ‘Migrant with Poor Prospects’: Racialized Intersections of Class and Culture in Dutch Civic Integration Debates.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41 (5): 882–900.

- Bonjour, Saskia, and Sébastien Chauvin. 2018. “Social Class, Migration Policy and Migrant Strategies: An Introduction.” International Migration 56 (4): 5–18.

- Brekke, Jan-Paul, Erlend Paasche, Astrid Espegren, and Kristin Bergtora Sandvik. 2021. Selection Criteria in Refugee Resettlement. Balancing Vulnerbality and Future Integration in Eight Resettlement Countries. Instistut for Samfunnskorskning.

- B-UMF – Bundesfachverband unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge. 2020. Beschluss zur Aufnahme von geflüchteten Minderjöhrigen aus Griechendland nur eine Mogelpacking. 12 March 2020. Accessed 8 February 2022. https://b-umf.de/p/beschluss-zur-aufnahme-von-gefluechteten-minderjaehrigen-aus-griechenland-nur-eine-mogelpackung/.

- CDU. 2020. Ergebnisse des Koalitionsausschusses vom 8. März 2020. Accessed 7 February 2022. https://archiv.cdu.de/artikel/ergebnisse-des-koalitionsausschusses-vom-08-maerz-2020.

- Chauvin, Sébastien, and Blanca Garcés-Mascareñas. 2014. “Becoming Less Illegal: Deservingness Frames and Undocumented Migrant Incorporation.” Sociology Compass 8 (4): 422–432.

- Chauvin, Sébastien, and Blanca Garcés-Mascareñas. 2018. The Myth of Humanitarianism: Migrant Deservingness, Promising Victimhood, and Neoliberal Reason. Barcelona.

- Chauvin, Sébastien, Blanca Garcés-Mascareñas, and Albert Kraler. 2013. “Employment and Migrant Deservingness.” International Migration 51 (6): 80–85.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence Against Women of Colour.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299.

- EKM-Evangelische Kirche in Mitteldeutschland. 2014. “Aufnahmeprogramm Für Syrische Flüchtlinge in Deutschland.” 2014. Accessed 11 October 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = Mr43eRhTU3M&t = 2s.

- Enab Baladi. 2018. “Dealing in Official Documents at the Syrian Consulate in Istanbul … We Want to See the Citizen’s Face Every Morning.” Enab Baladi 2018. Accessed 14 January 2019. https://english.enabbaladi.net/archives/2018/06/dealing-in-official-documents-at-the-syrian-consulate-in-istanbul-we-want-to-see-the-citizens-face-every-morning/.

- Engler, Marcus. 2015. Sicherer Zugang. Die Humanitären Aufnahmeprogramme für Syrische Flüchtlinge in Deutschland. Berlin, Germany: Sachverständigenrat deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration.

- Enloe, Cynthia. 1990. Bananas, Beaches and Bases. Making Feminist Sense of International Politics. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Fallon, Katy. 2022. “Refugee Aid Workers Decry ‘Hypocrisy’ of European Governments.” Al Jazeeera. 16 March 2022. Accessed 25 March 2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/16/ngos-say-ukraine-refugee-crisis-easier-with-govt-support.

- Fassin, Didier. 2012. Humanitarian Reason. A Moral History of the Present. Humanitarian Reason: A Moral History of the Present. Los Angeles/London: University of California Press.

- FitzGerald, David S., David Cook-Martín, Angela S. García, and Rawan Arar. 2017. “Can You Become One of Us? A Historical Comparison of Legal Selection of ‘Assimilable’ Immigrants in Europe and the Americas.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (1): 1–21.

- Fratzke, Susan, and Hanne Beirens. 2020. The Future of Refugee Resettlement: Made in Europe?” 2020. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/future-refugee-resettlement-made-in-europe.

- Garnier, Adèle, Liliana Lyra Jubilut, and Kristin Bergtora Sandvik. 2018. Refugee Resettlement. Power, Politics and Humanitarian Governance. New York/Oxford: Berghahn.

- Garnier, Adèle. 2014. “Migration Management and Humanitarian Protection: The UNHCR’s ‘Resettlement Expansionism’ and Its Impact on Policy-Making in the EU and Australia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (6): 942–959.

- Hill Collins, Patricia. 1998. “It’s All In the Family: Intersections of Gender, Race, and Nation.” Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 13 (3): 62–82.

- Holmes, Seth M., and Heide Castañeda. 2016. “Representing the “European Refugee Crisis” in Germany and Beyond: Deservingness and Difference, Life and Death.” American Ethnologist 43 (1): 12–24.

- Huysmans, Jef. 2000. “The European Union and the Securitization of Migration.” Journal of Common Market Studies 38 (5): 751–777.

- Huysmans, Jeff, and Vicky Squire. 2009. “Migration and Security.” In Handbook of Security Studies, edited by Myriam Dunn Cavelty and Victor Mauer. London: Routledge.

- Janmyr, Maja. 2016. “Precarity in Exile : The Legal Status of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon.” Refugee Survey Quaterly 35 (4): 58–78.

- Jansen, Bram J. 2008. “Between Vulnerability and Assertiveness: Negotiating Resettlement in Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya.” African Affairs 107 (429): 569–587.

- Joppke, Christian. 2007. “Beyond National Models: Civic Integration Policies for Immigrants in Western Europe.” West European Politics 30 (1): 1–22.

- Massey, Douglas. 2008. Categorically Unequal. The American Stratification System. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- McCall, Leslie. 2005. “The Complexity of Intersectionality.” Signs 30 (3): 1771–1800.

- Menetrier, Agather. 2021. “Implementing and Interpreting Refugee Resettlement Through a Veil of Secrecy: A Case of LGBT Resettlement from Africa.” Frontiers in Human Dynamics. doi:10.3389/fhumd.2021.594214.

- Mourad, Lama, and Kelsey P. Norman. 2020. “Transforming Refugees Into Migrants: Institutional Change and the Politics of International Protection.” European Journal of International Relations 26 (3): 687–713.

- Mügge, Liza, and Marleen van der Haar. 2016. “Who Is an Immigrant and Who Requires Integration? Categorizing in European Policies.” In Integration Processes and Policies in Europe, IMISCOE Research Series, edited by Blanca Garcés-Mascareñas and Rinus Penninx, 31–55. Cham/Heidelberg/New York/Dordrecht/London: Springer.

- Pallister-Wilkins, Polly. 2015. “The Humanitarian Politics of European Border Policing: Frontex and Border Police in Evros.” International Political Sociology 9 (1): 53–69.

- Patrick, Odysseus. 2017. “Australia’s Immoral Preference for Christian Refugees”. The New York Times. Accessed 8 February 2022. 3 May 2017.

- Ratzman, Nora, and Nina Sahraoui. 2021. “State of the Art. Conceptualising the Role of Deservingness in Migrants’ Access to Social Services.” Social Policy & Society 20 (3): 440–451.

- Ravn, Stieve, Rilke Mathieu, Milena Belloni, and Christiane Timmerman. 2020. “Shaping the ‘Deserving Refugee’: Insights from a Local Reception Programme in Belgium.” In Geographies of Asylum in Europe and the Role of European Localities, edited by Birgit Glorius and Jeroen Doomernik. Cham: IMISCOE Research Series.

- Roggeband, Conny, and Marleen van der Haar. 2017. “‘Moroccan Youngsters’: Category Politics in the Netherlands.” International Migration 56 (4): 79–95.

- Sandvik, Kristin Bergtora. 2009. “The Physicality of Legal Consciousness: Suffering and the Production of Credibility on Refugee Resettlement.” In Humanitarianism and Suffering: The Mobilization of Empathy, edited by Richard Ashby Wilson and Richard D. Brown, 223–244. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schinkel, Willem, and Friso Van Houdt. 2010. “The Double Helix of Cultural Assimilationism and Neo-Liberalism: Citizenship in Contemporary Governmentality.” British Journal of Sociology 61 (4): 696–715.

- Schneider, Hanna. 2020. The Strategic Use of Resettlement: Lessons from the Syria Context. Amman: Durable Solutions Platform.

- Sözer, Hande. 2019. “Categories That Blind Us, Categories That Bind Them: The Deployment of Vulnerability Notion for Syrian Refugees in Turkey.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (3): 2775–2803.

- Turner, Lewis. 2019a. “Syrian Refugee Men as Objects of Humanitarian Care.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 21 (4): 595–616.

- Turner, Lewis. 2019b. “The Politics of Labeling Refugee Men as ‘Vulnerable’.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 28 (1): 1–23.

- UNHCR. 2003. Background Note on the Application of the Exclusion Clauses: Article 1F of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. Geneva: UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

- UNHCR. 2011. UNHCR Resettlement Handbook. Geneva.

- UNHCR. 2017. “Statement to the 68th Session of the Executive Committee of the High Commissioner’s Programme.” 5 October 2017. Accessed 21 October 2018. https://www.unhcr.org/admin/dipstatements/59d4b99d10/statement-68th-session-executive-committee-high-commissioners-programme.html.

- UNHCR. 2019. “Europe Resettlement.” Accessed 12 May 2022. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/77244.

- UNHCR. 2020. “Europe Resettlement.” Accessed 15 August 2022. https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/87968.

- UNHCR. 2022a. Projected Resettlement Needs 2023. Geneva: UNHCR.

- UNHCR. 2022b. What is Resettlement? https://www.unhcr.org/resettlement.html.

- Van Selm, Joanne. 2004. “The Strategic Use of Resettlement: Changing the Face of Protection?” Refuge 22 (1): 39–48.

- Van Selm, Joanne/UNHCR. 2013. Great expectations. A review of the strategic use of resettlement. August 2013. https://www.unhcr.org/520a3e559.pdf. (accessed 15 February 2018).

- Verloo, Mieke. 2005. “Mainstreaming Gender Equality in Europe. A Critical Frame Analysis Approach.” The Greek Review of Social Research 117 (B’): 11–34.

- Welfens, Natalie, and Saskia Bonjour. 2021. “Families First? The Mobilization of Family Norms in Refugee Resettlement.” International Political Sociology 15 (2): 212–231.

- Welfens, Natalie, and Yasemin Bekyol. 2021. “The Politics of Vulnerability in Refugee Admissions Under the EU Turkey Statement.” Frontiers in Human Dynamics. doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.622921.

- Welfens, Natalie. 2021. Categories on the Move. Governing Refugees in Transnational Admission Programmes to Germany. Doctoral Thesis. University of Amsterdam.

- Welfens, Natalie. 2022. “Whose (In)Security Counts in Crisis? Selection Categories in Germany’s Humanitarian Admission Programmes Before and After 2015.” International Politics 59: 505–524.

- Yanow, Dvora, and Marleen van der Haar. 2013. “People out of Place: Allochthony and Autochthony in the Netherlands’ Identity Discourse — Metaphors and Categories in Action.” Journal of International Relations and Development 16 (2): 227–261.

- Yurdakul, Gökce, and Anna Korteweg. 2021. “Boundary Regimes and the Gendered Racialized Production of Muslim Masculinities: Cases from Canada and Germany.” Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 19 (1): 39–54.

Primary data

- Interview former Minister of the Interior of a Southern German Federal Province. 2017. 5 December. Germany.

- Observations Resettlement Expert Meeting. 2018. 27–28 September 2018, Berlin, Germany.

- Observations Resettlement Expert Meeting. 2019. 13–14 May 2019, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

- Observations Resettlement Expert Meeting. 2020. 23 September 2020, online.

- Observations UNHCR Turkey, Resettlement Unit. 2018. 8–10 November 2018, Ankara, Turkey.