ABSTRACT

Can class help understand refugee camp dynamics? We mobilise the concepts of exploitation, life chances, and cultural and social capital to analyse socio-economic stratification and inequality in Nyarugusu refugee camp in Tanzania. The research draws from a longitudinal survey with Congolese and Burundian refugee households and over 200 qualitative interviews carried out in 2017–2020. We show that camp residents, especially repeat Burundian refugees, are mostly from the poorest classes of their home countries. Inside the camp, however, we find socio-economic inequalities, partially driven by incentive aid workers and refugee ration traders who accumulate higher social and cultural capital and maintain their positions through exploitative terms of trade. The members of the camp ‘upper class’ have better life chances which affects their wealth, spatial mobilities, and migration possibilities. It emerges that the restrictive and often punishing encampment policy of Tanzania over time, which includes ration cuts and market shutdowns, erratically ‘flattens’ class. Zooming out to include social classes in the wider Kigoma region, we argue that the shared and distinctive experience of ‘refugeedom’ and access to humanitarian capital make the whole refugee camp a class of its own.

Gloire lives in Nyarugusu refugee camp in north-western Tanzania. She was extremely poor in southern Burundi and remained so when we met her in 2017. Her neighbour, Jacques, fled to Tanzania from Burundi with substantial financial capital; he soon started a fish-selling business that was thriving until the camp economy collapsed in July 2018, when the government shut down the main market. At the other end of the camp, meet Dalia, a Congolese woman of wealth and status whose connections led her to buy and sell World Food Programme (WFP) rations, increasing her wealth substantially.

These vignettes above, and countless other stories, illustrate how socio-economic position in protracted refugee situations can be fluid for some, yet stubbornly calcified over time for the majority. To understand these socio-economic dynamics we follow Wright (Citation2005) and ask: ‘is class analytically productive to understand stratification and inequality [in a refugee camp setting]?’ We borrow elements from the theories of class of Marx, Weber, and Bourdieu and assemble them to analyse camp stratification as we observed it. We find that the costs to flee, particularly for those already poor in their countries of origin, initially causes a ‘flattening’ of economic strata. The visual metaphor of flattening, like a downward hydraulic compactor, is used to refer to external shocks imposed by the state and humanitarian system that prevent upward socio-economic mobility for most camp residents. Those in privileged positions, such as food-aid resellers or incentive workers are the closest to emerge as a distinct, albeit tenuous, social class. We observe different levels of wealth in Nyarugusu, which we group into three categories (‘ultra-poor’, ‘poor’, and ‘non-poor’) that correlate with measures of the ability to exploit lower classes (Marx), life chances (Weber), and social capital (Bourdieu). However, these embryonic classes do not solidify – cuts in food rations, the shutdown of refugee markets, and other shake-ups of the social order further flatten the camp residents’ livelihoods downward. Only a tiny number of camp residents weather these events by mobilising their higher socio-economic capital to leave the camp for a new exile or return to their country of origin with a landing softened by their wealth. Moreover, due to camp residents’ unique ‘refugeedom’ status (Riga, Langer, and Dakessian Citation2020), we contend that they constitute a ‘camped class’ vis-à-vis their Tanzanian neighbours.

While the study of refugee livelihoods has substantially grown recently (Betts et al. Citation2017), only a small strand of the refugee and migration studies literature has engaged with the idea that displaced people are also ‘classed’ (Van Hear Citation2014; Citation2004). Too often, there is an overemphasis on camp residents as all poor and coming from poor backgrounds (Hunkler et al. Citation2022), which obfuscates the possibility of seeing class as a driver, buffer, or obstacle to the spatial mobility of refugees living in camps (Faist Citation2013). In contrast, recent research in this issue by Rudolf (Citation2022), explores the sort of capital mobilised by refugees in urban Dar es Salaam in Tanzania; we explore the contours of class and socio-economic positioning in encamped life at the other end of the country.

After introducing our theoretical positioning and the refugee situation in Tanzania, we present our mixed-methods methodology. The core argument of the paper is developed over two parts: a section on class in the countries of origin and during flight and a more comprehensive section on class in Nyarugusu refugee camp between 2017 and 2020. The latter section is divided into four subsections: we present (1) socio-economic stratification in Nyarugusu and analyse how these are shaped by (2) livelihoods and economic activities, (3) government and humanitarian interventions, (4) and spatial mobility and migration.

Refugees and class: theoretical and empirical considerations

The theories of Marx, Weber, and Bourdieu are undoubtedly among the most influential in debates on class. However, their theories do not explicitly engage with either forced displacement or African contexts (marked by power and political mobilisations around ethnicity, religion, age, and gender, among others). Together with the editors of this issue (Hunkler et al. Citation2022) we contend that they can, nevertheless, constitute useful analytical tools, as discussed below.

Theories of class

As Karl Marx before him, Max Weber describes class as an economic interest group. ‘Class’, which often overlaps but is not similar to ‘status’, is a form of privilege affecting actors’ abilities to further their ‘life chances’ and find satisfaction (Lentz Citation2015). He ties it closely to socio-professional occupation, which can be seen with a few classed occupations in Nyarugusu. Should we infer there are no classes beyond the wealthy food-brokers and NGO incentive workers? The work of Pierre Bourdieu provides elements that paint a more nuanced picture. In brief, he describes class as being at the intersection of economic, cultural, and social forms of capital, as maintained over time via processes of distinction through habitus – people’s ingrained skills and dispositions (e.g. consumption). Classes and taste are closely related in dialectic connections between structure and agency, pushing us to also pay attention to consumption and other forms of ‘taste’.

In camps marked by substantial asymmetries of power, a nuanced reading of Marx can also be useful by situating his understanding of class alongside exploitation and the ownership or control of the means of production. Refugee economies do entail dynamics of exploitation – we develop below the case of the WFP food traders who exploit the rest of the camp’s precarious positions. However, neither higher classes nor other refugees in Nyarugusu have the freedom of mobility or have control over the means of production. Erik Olin Wright (Citation1985), building on Marx, points out that a group (and especially the ‘middle class’) can be both exploiter and exploited.

Forced migration and class

The most frequent use of class theory in forced migration studies is to understand migration outcomes or destination countries. Van Hear (Citation2014) utilises Bourdieusian theory to show that, in conflict contexts, economic, cultural, human and social capital are mobilised to flee and navigate increasingly restrictive international migration regimes. Lewis Turner (Citation2015) demonstrates that governments play a role in the production of encamped classes by arguing that encampment policies in Lebanon and Jordan are designed to exclude lower classes of Syrian refugees and satisfy labour market needs.

Omata’s (Citation2017) book, The Myth of Self Reliance, is one of the few projects to explore socio-economic class inside camps and is most directly analogous to our research. Using the case of Buduburam camp in Ghana, he historicises class throughout displacement by demonstrating the reproduction of class from Liberia to the camp. Omata identifies Americo-Liberians with long histories of monopolising resources and political power who have used social networks to migrate to the US for decades. Socio-economic stratification through Americo-Liberian exploitation over centuries in Liberia produced camp inequalities because transnational links to the US resulted in remittances being sent back to Buduburam. Unlike Americo-Liberians, remittances for other Liberian ethnic groups in the camp are not accessible without these longstanding migration patterns. Omata settles with a definition of social class most closely aligned to Bourdieu's (Citation1986) understanding of social capital, which ‘aimed to highlight how different social classes form and reproduce themselves in relation to one another, with corresponding implications for different types of privilege, inequality, and oppression’ (Omata Citation2017, 9).

While the present article takes cues from Omata’s research, there are contextual differences between Buduburam and Nyarugusu that invite caution. Nyarugusu is more rural, much bigger, and still received rations and substantial aid at the time of the research. Moreover, Omata concludes that the two highest economic strata he identified in Buduburam received remittances regularly or intermittently. While Congolese have been resettled from Nyarugusu since 2012 and send remittances back, our data show less prominence of income from remittances than in Buduburam, as we will soon explain in more depth.

In agreement with Omata’s work, the socio-economic situation of refugees in Tanzanian camps must also be understood in light of the histories of class and power in Congo and Burundi over the longue durée, although social stratification has been substantially disrupted through asylum politics in Tanzania since the 1990s. When considering class, Nyarugusu is best viewed as two camps within one: a Congolese and Burundian camp (Boeyink Citation2020). Burundian refugees are less established economically and are more discriminated against and exploited by nearby Tanzanians and the state (Boeyink Citation2020). To understand socio-economic stratification in the camps today, we must look at both Burundian and Congolese refugees’ permutations of class in countries of origin, during flight, and in camps.

Refugee camps of Tanzania

Located in north-western Tanzania, Kigoma is the poorest region in Tanzania and hosts the country’s three remaining refugee camps. We focus on the largest, oldest, and most diverse of them: Nyarugusu, which was established in 1996 to accommodate Congolese fleeing the First Congo War and subsequent conflicts in eastern DR Congo. The camp population, estimated at 60,000 in early 2015, doubled in the same year as Burundian refugees started to arrive. The protests, failed coup, government’s violent crackdowns and intimidation of those opposing President Pierre Nkurunziza’s stay in power led more than 400,000 Burundians to flee, primarily to Tanzania. Nyarugusu quickly filled to capacity and two camps first established in the 1990s, Nduta and Mtendeli, were resurrected to accommodate the new arrivals. As of March 2020 (UNHCR Data Portal), there were around 61,000 Congolese refugees and 162,000 Burundians in the three camps. The governments of Tanzania and Burundi have been warning since 2017 that refugees ‘are to return to their country of origin, whether voluntarily or not’. Congolese refugees have not received this same pressure to leave due to a long history of discrimination toward Burundians in Tanzania (Boeyink Citation2020).

Tanzania’s strict encampment policy, which includes no freedom of movement or employment outside the camps, sits on the most restrictive end of East Africa’s refugee-hosting countries: Uganda is seen as the most open, whereas Kenya is somewhere in the middle (Deardorff Miller Citation2017). The previous ‘open door’ era of refugee policy in Tanzania after independence offered a secure base to dissidents opposed to white settlers in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Angola, and Mozambique whereas Rwandan and Burundian refugees were provided land to cultivate the peripheries (Chaulia Citation2003). The 1965 refugee legislation was designed to contain and control refugees from Rwanda and Burundi. Refugee restrictions increased in the 1990s as the country received hundreds of thousands of Congolese, Burundian, and Rwandan refugees. The Tanzanian state, dismantled by structural adjustment policies, abdicated governance and management of the camp to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) but reserved the right to securitise and contain the population therein (Rutinwa Citation1996). This policy is codified in law and is still in force. In recent years the space of asylum has constricted even further through shutdowns of markets, humanitarian livelihood interventions, and more violent police presence under the late President John Magufuli’s nationalist rule (Boeyink Citation2019; Citation2020). This social exclusion due to policies enacted from above is intertwined with depoliticised humanitarian care, everyday exclusionary interactions with neighbouring Tanzanians, and refugees’ agency in navigating these overlapping subjectivities.

Refugeedom

This long history of segregation and exclusion in Tanzania fit’s what Riga, Langer, and Dakessian (Citation2020) conceptualise as ‘refugeedom’, which conceptualises the refugee as: (1) a rights-bearing juridical subject who makes political claims; (2) the suffering subject who has experienced trauma through war and/or displacement in need of humanitarian support; (3) the politicised, Othered, or racialised subject or political ‘(sub)altern’ excluded by host society (Citation2020, 736–737). While there are some levels of socio-economic stratification within the camps as demonstrated below, we argue that the surrounding Tanzanian society and the humanitarian assemblage caring for and controlling the camp should be included in the analysis. With their inclusion, we see the subjectification of refugees as the creation of a camped class.

Methodology

This article builds on independent fieldwork conducted by Boeyink from March until November 2017, with periodically recurring remote surveys carried out by camp resident research assistants in 2019-2020. Additionally, Boeyink and Falisse researched livelihood strategies with different research participants for UNHCR in February 2018.Footnote1

The independent fieldwork followed the methodology Collins et al. (Citation2009) laid out in Portfolios of the Poor. Boeyink and research assistants (RAs) met with 77 households split between Congolese and Burundians in Nyarugusu every two weeks between August 2017 and August 2018.Footnote2 This entailed recording information on their livelihoods and economic transactions. The RAs are camp residents, five male and one female, and worked with participants of their nationalities in their primary languages. Participants were recruited by RAs at cash distributions or by going to each zone in the camp. At the first baseline meeting, Boeyink explained and gained verbal rather than written consent due to inconsistent literacy rates of participants. Financial diaries were used to gain understandings of livelihoods and economic situations over time as households were affected by shocks and seasonal variation.

The frequent meetings of this approach allowed researchers to build relationships and close rapport with the households. They led to in-depth unstructured interviews that covered aspects extending beyond livelihoods, discussing economic and mobility histories, strategies, and perceptions of events in the camp and beyond; before and after displacement.

In contrast, the research initially carried out for the UNHCR report covered more individuals – more than 200 interviews and focus groups mostly with camp residents but also UNHCR, WFP, NGO partners, and Tanzanian government officials and neighbouring communities – but consisted in much shorter, semi-structured discussions focussed on livelihoods.

Households, are our unit of analysis, and the informants’ identities are guaranteed protection using pseudonyms and data protection practices. No household dropped out of the financial diaries and the interviews were with refugees living in the camp only (for an analysis of urban refugees in Tanzania, see Rudolf (Citation2022) in this issue).

Class in countries of origin and during flight

Ethnicity is often described as a key fault line in Burundian society and is associated with classes and hierarchies (Daley Citation1991). Burundi’s three ethnicities, the Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa, share ‘virtually the same culture, language, name, religion, and so forth’ (Isabirye and Mahmoudi Citation2000), and the extent to which Hutu and Tutsi groups were distinct groups before the colonial encounter is debated. What is clear is that the German and Belgian colonists injected a racialised and ethnicised hierarchy, giving the Tutsi – in Marxian terminology – control and ownership in all aspects of society including politics, education, and the economy (Daley Citation2006). Post-independence Tutsi rule maintained such privilege and ethnicity was a key, but not the only, fault line along which the 1993–2008 civil war was fought.

The mass displacement in 2015, which was triggered by a crisis that was not primarily ethnic in nature, caused movements along ethnic and class lines. Tutsi were mostly internally displaced and ‘entrenched’ or fled to Rwanda (Purdeková Citation2017). The wealthier among these settled into cities or further afield to places such as Europe or Canada. While there were some wealthier outliers, the lowest class in Burundi – poor, landless Hutus – fled to Tanzania as a fairly homogenous bloc (Schwartz Citation2018). It is estimated by the WFP that 60–80% of this population was in fact ‘re-displaced’ for the second or third time beginning with the civil war in the 1990s or the 1972 genocide (Purdeková Citation2017, 7). While some of these ‘repeat’ refugees managed to economically integrate in Tanzanian when first fleeing, the new displacement was to a new camp and our research suggests that past networks in Tanzania could not be revived. Schwartz (Citation2018) adds that many who fled in 2015 to Tanzania did so not entirely due to persecution or intimidation, but also because of the failure to economically and socially reintegrate following their repatriation to Burundi in the early 2000s and forced repatriation from Mtabila camp in 2012 (Falisse and Niyonkuru Citation2015). The returnees primarily lived along the bordering southern provinces of Burundi and often failed to access decent livings or protection. Many were embroiled in land disputes and unable to provide livelihoods, which blended with their fears of a rapid deterioration into conflict like in times past. This resonates with Jacqueline’s experience who explained in November 2017, that before displacement:

life was difficult. I tried to cultivate for others for money. I begged for a place to cultivate my own land. I saw the problems in my country. I saw it would be difficult to run later. I decided to leave before more difficulties came.

There was no security in the country, so we decided to leave. We took a bus from Rumonge to Nyanza-Lac, and from Nyanza-Lac to Tanzania, we walked because there were many security checkpoints, so we had to hide ourselves. We used 400,000 Burundian Francs [USD $218.33]. We had to pay for my whole family and had to pay for people who showed us the way around barriers. We had to pay a bribe even at Kabunga [the main Tanzanian transit centre].

Eastern Congo has also faced a complicated class history centred around ethnicity, land rights and land availability. Most Congolese refugees are from the neighbouring province of Sud Kivu. Van Acker (Citation2005) describes Kivu as a hierarchical society with customary kings or mwami to whom people paid tribute to access land. These dynamics started changing after independence when neighbouring Rwandan and Burundian migrants and refugees began settling in Kivu. In 1973, President Mobutu passed a law placing all lands in the hands of the state. Through this transition between customary and modern land rights, mwamis became the arbiters of class (Van Acker Citation2005): social mobility could be attained through social capital linked to the state (such as civil servants or the military) or through customary actors set increasingly along ethnic lines. The contestation of land continued past Mobutu’s fall in the 1990s and contributed to setting the Kivus up for violence. Three decades of war and violence curbed, but did not eliminate, the authority of the state and chiefs; substantial power and control now often resides between a vast constellation of (often armed) actors.

There is no extensive research on the socio-economic strata of the first arriving Congolese refugees to Tanzania – many arriving more than two decades ago. Informants have suggested that the few customary chiefs and low-level former state officials among the refugees do not play a key role in the camp. Olivier explained to us in May 2019 that the mwamis who live in the camp are only respected ‘the same way an old teacher would be’ but without material and political benefits.

Class in the camp

Most Congolese and Burundian refugees have struggled to economically establish themselves in the camps upon first arriving. For example, Honorée recalled in November 2017 that the 20,000 TZS (USD 8.69) she fled with from Burundi was quickly spent on treatment for cholera that infected many Burundians upon arrival in Tanzania. To start a business, she said the first three months she ‘kept [her] children hungry’ by consuming a small portion of food rations and selling the rest for capital to sell onions, a practice shared by many (Boeyink Citation2021). The stories recounted by the Congolese refugees who fled the First and Second Congo Wars of the 1990s were strikingly similar to the experiences of the 2015 Burundian refugees’ narrations. Since Burundians arrived in Nyarugusu, the Congolese have had clear advantages over Burundians: protracted exile in Tanzania had allowed them to embed themselves in the local economy of markets and agricultural systems near the camp and some have received remittances from resettled friends and family resettled to high-income countries. Remittances are not as accessible to Burundians who have far fewer resettled friends and family members. In this sense, the Congolese refugee experience resembled the economy of ‘protracted refugee camps’ in Uganda analysed in Refugee Economies by Betts et al. (Citation2017). With less time to integrate, the Burundian side of Nyarugusu camp seemed more akin to the limited temporality of Ugandan ‘emergency refugee camps’ still establishing economic networks in the region (Betts et al. Citation2017, 140). Moreover, Burundians have faced xenophobic discrimination from Tanzanians in the land rental systems surrounding the camp where Tanzanians report not trusting Burundians and charging more for rental or forcing Burundians to dangerously go further distances outside the camp to find willing renters (Boeyink Citation2020). The staggering disparities between Congolese and Burundians in Tanzanian camps were plainly visible in the Community Household and Surveillance (CHS) studies carried out in 2016: 19% of the Congolese refugees were ‘asset very poor’ versus 75% of the Burundians (WFP & UNHCR Citation2017).

Socio-economic stratification in Nyarugusu

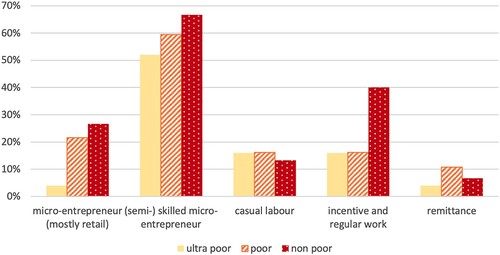

Similar to Omata’s (Citation2017) work on stratification in Buduburam camp, we analysed the current assets (cash, cattle, poultry, consumer goods, land) and consumption of the participants’ financial diaries. We use the Tanzanian poverty line (TZS 1,200 per day) to distinguish among three groups of refugees: (1) the ‘ultra-poor’ whose reported assets are worth less than a monthly wage; (2) the ‘poor’ whose assets are worth between one- and three-monthly wages; and (3) the ‘non-poor’ whose assets are worth more than three-monthly wages. Income, as we discuss later, is volatile and therefore less appropriate to define categories. Economic capital is the starting point of our investigation, which we think is warranted in a context of extreme poverty, but we soon discuss other dimensions of class. shows the extent of inequalities, with a vast majority of people owning next to nothing.

Figure 1. Distribution of the total value of assets per household (September 2017). Note: adjusted for household size (counting 0.5 per child/elderly).

In a follow-up survey, we asked whether people felt better off, worse off or in a similar situation to the rest of the camp. Only in the ‘non-poor’ group we found a majority who declared feeling better off.

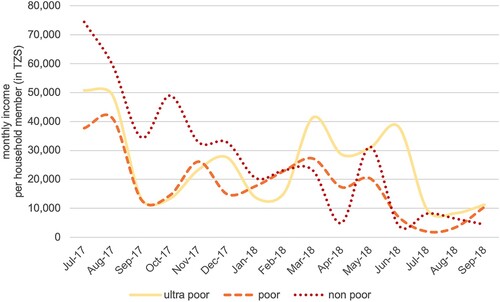

confirms the qualitative work. We analyse different aspects of class, comparing our economic strata and discussing results that are statistically significant at p < 0.1 (using Chi-Squared and Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests). Firstly, considering the cultural capital typically acquired pre-displacement, such as education or fluency in French or English, we find no major difference between groups. We develop this point in the next section where we show that better work opportunities in camp are not necessarily related to cultural capital in the country of origin. Secondly, social capital indicators show differences across categories: the ‘non-poor’ are more socially active. They are more likely to be head of an association, have more friends, and more people who they think would lend them money. We will not attempt to assess the causal relationship between social and economic capital, but this suggests the development of a class (the ‘non-poor’) that is not only defined in economic terms. Strong or multiple social ties are useful to absorb shocks through personal loans, but they also come with social liabilities: in a camp setting where many are poor, the pressure to share food, lend money, and contribute to funerals and social events has been described as a constant pressure. Being better-connected means, as our informants explained and the table shows, a complex ‘gift economy’ or ‘shared destitution’ emerges where people support relatives and friends (Omata Citation2017). Thirdly, there is an apparent relationship between the economic position of the households and the time spent in the camp: the ultra-poor had spent much less time in residence. However, this relationship is not linear (the non-poor spent less time in the camp than the poor) suggesting a complex story and probably other factors playing out such as economic shocks. It is useful to note that two years after the arrival of the Burundians, the difference between groups is less visible than in the 2016 Community Household and Surveillance survey mentioned earlier. Finally, while there are clear differences in terms of assets, the differences in terms of consumption and income are less pronounced. The ‘poor’ category reports a level of income that is not statistically different from the ‘ultra-poor’.

Table 1. Key characteristics across asset groups.

Refugee work

Beyond assets, professional activities and income derived from work are typical indicators of socio-economic classes. They should be considered carefully in the camp context: the ‘work’ refugees do is rarely stable, and the incomes and salaries they receive is not the main livelihood source for most. In 2017, 95% of all residents of Nyarugusu reported relying primarily on WFP food (WFP & UNHCR Citation2017). A third of the households of our portfolio reported having no source of income at all, while only 6.5% (5 out of 77) reported total income above the Tanzania poverty line of TSZ 1,200 per day per person. We highlight four categories of work: ‘micro-entrepreneurs’; trade and craft labourers; manual labourers working outside the camp; and ‘incentive workers’ and humanitarian brokers who come closest to an upper-class in the camp.

Consistent with the current atomised global refugee self-reliance strategy led by UNHCR, which focuses on individual and household ‘resilience’, many of those who can muster the capital to attain incomes in the camps are hailed as ‘micro-entrepreneurs’ (Easton-Calabria and Omata Citation2018). Running counter to Weber’s fixation on entrepreneurship as a privileged class in eighteenth-century Europe, camp entrepreneurship runs a wide gamut from children selling sugarcane for petty change, to the rare case of businesswomen like Dalia, who is wealthy enough to own cars (kept concealed outside of the camp). Dalia, and even more powerful ‘bosses’ as they are locally referred, act as brokers buying and selling WFP food rations that are shipped to markets across Tanzania and East Africa. The hub of these markets is the common market constructed by UNHCR and partner organisations near the entrances to the camps (within the 4-km perimeter where refugees are allowed to conduct business). Here Tanzanians and camp residents can operate retail and wholesale businesses. According to the Nyarugusu common market chairperson (interviewed in February 2018), there were more than 500 market shops registered to refugees and Tanzanians that year. A key issue faced by the ‘micro-entrepreneurs’ is start-up capital, which we found is typically raised through borrowing from friends and family, engaging in labour such as brick-making or illegal and precarious agriculture outside the camp or, more rarely, receiving remittances. In short, it requires social capital to start a business.

Among the micro-entrepreneurs (and their employees) are found a series of trade and craft professions: tailors, hairstylists and barbers, cooks and bakers, soap-makers, mechanics and electronic repair people, and construction labourers. People developed these skills both in the camps or countries of origin, through formal training programmes offered by NGOs, or informally from acquaintances or family. These training programmes are designed to be free and often target ‘vulnerable’ households. However, social or economic capital is often required. Many informants reported it takes personally knowing or paying a bribe to the recruiters to be admitted. Once people attain marketable skills, they can be employed by others at a low rate or start their own businesses – requiring difficult-to-obtain capital.

The third category of work consists of manual labourers who illegally work outside of the camp. There is an extensive agricultural system surrounding the camps where refugees can rent land from Tanzanians or work as labourers for Tanzanians or other refugee renters. Some do this for a few days intermittently, whereas others work six days a week during labour periods.Footnote3 It is also known that some women leave the camp for sex work in nearby towns and villages. Within the camp, there is low-paying work such as mud brick-making or bicycle transport services. Finally, there are significant amounts of unpaid household labour that often befalls women, which includes gathering firewood outside the camp, collecting WFP food rations, fetching water, or care work inside the home.

As shows, the ultra-poor, poor, and non-poor all engage in these activities, in relatively comparable proportions. The exception is micro-entrepreneurship, which is not accessible to the ultra-poor without start-up capital. In the Weberian sense, camp entrepreneurship precludes the ultra-poor but is not only a position of the highest class. Our survey shows that, whenever possible, households diversify economic strategies through multiple family members working or one member having multiple incomes. The non-poor especially can combine different strategies.

The final category of income, which most closely approaches an upper social class, are those who are bestowed with financial and social capital from the humanitarian apparatus, such as ‘incentive workers’, and those who co-opt and usurp it, such as WFP food-brokers or ‘bosses’ who employ smaller food-gatherers known as madalali.Footnote4 For this non-exhaustive upper-class list of professions, Bourdieu’s capitals theory offers productive explanatory power. Incentive workers are hired by UNHCR and aid partners, but are considered ‘voluntary’ and paid lower than Tanzanian minimum wage. Nevertheless, the pay remains well above the average income in the camp. Incentive work includes survey enumerators, language interpreters, social and health workers, teachers, cleaners, security officers, among others. Incentive workers often have a predictable monthly salary, which is precious as it can be channelled into other businesses run by household members. Rather than the incentive work per se, it is typically supplementary businesses that constitute the main household incomes. Incentive positions are desired because waged employment is rare and requires no start-up capital (apart from occasional bribes). To obtain these positions, refugees must be able to read, write, and speak English or Swahili well enough to complete an application and interview. In contrast, cleaner and security positions do not require the cultural capital of education and language skills and are not typically considered a privileged position, however, they are still highly sought after and often require social connections to attain.

Wealthy food resale bosses such as Dalia occupy the highest economic strata and were among the wealthiest households we met in Nyarugusu. She attained this position because she was already esteemed in the camp through marriage with a school headmaster. She gained the trust of a prominent boss she regularly sold baked goods to and was eventually given start-up capital and connections to wealthy Tanzanian traders who ship the wholesale food outside of the camp. According to one informant, this system sells more than an estimated 1,000 tonnes wholesale across Tanzania and East Africa monthly. Beyond possessing economic wealth, this small elite group is rich in social capital and are held in high esteem by some for bringing desperately needed liquidity to the cash-starved camp yet resented by others for the exploitative purchasing rates forced upon ration sellers. As (S. Turner Citation1999) points out, incentive workers and businesspeople like Dalia often become ‘big men’ in the camp and gain influence in their communities, overtaking elders and leaders who had substantial social and economic capital previously in their countries of origin. In addition to having greater ‘life chances’ in the Weberian sense of higher income and closer connections to humanitarian power and resources, this is the one group, which actively exploits fellow camp residents, a crucial component of Marxian theory. Although bosses are valued for the necessary access to capital, the food is sold to them at a heavy loss, which enriches bosses at the expense of food recipients’ wellbeing (Boeyink Citation2021). Of the different livelihood activities surveyed here, bosses are the closest to contribute to building a distinctive class in the camp by encompassing substantial components of Marxian, Weberian, and Bourdieusian theory of class.

Humanitarian and government interactions

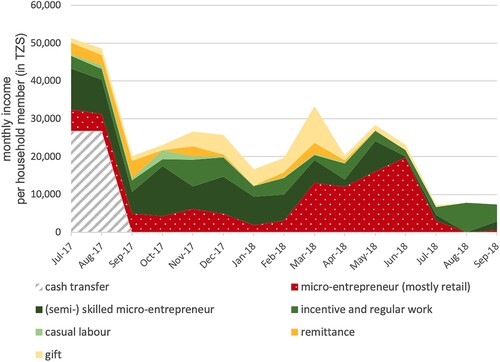

Refugee camps are subject to profound, yet erratic economic changes from humanitarian and governmental policies. Humanitarian aid innovations can greatly raise households’ economic prospects, which was the case of the cash transfer programme initiated by WFP as a substitute for in-kind food distribution. Refugees typically sell their WFP rations at a loss to madalali and bosses to purchase more enjoyable food or to meet other needs. All interlocutors welcomed the cash transfer programme pilot when it was introduced in December 2016. Selected households received 20,000 TZS (USD 8.69) per person each month instead of staple food items. This amounts to 2,500 TZS more than the average income per person we calculated during our baseline survey. The pilot cash transfer seemed to raise the floor of each economic class: the 2017 CHS survey reveals that those who received cash were able to purchase maize on average to last 24 days, whereas for non-cash recipients, maize only lasted for 17 days after distribution (WFP & UNHCR Citation2017, 27). The same survey suggests that cash was also used to acquire assets, which was confirmed by our participants. For instance, Bénédicte, a Burundian woman in Nyarugusu (interviewed February 2018), saved some of the WFP cash until she raised 86,000 TZS (USD 37.39), enough to start a business buying and selling food. This would have been nearly impossible on reduced food rations.

If international humanitarian aid gives, then the Tanzanian government has the power to shut down and take away, which has repeatedly been the case under President Magufuli. Two devastating shutdowns linked to humanitarian aid and government policy occurred during our research. First, in August 2017, the state abruptly ended the WFP cash transfer programme. Second, in July 2018, the government barred the use of common markets of the three camps, closed many wholesale businesses, and banned bicycles and motorcycles in the camp. Both shutdowns were governmental efforts to impel refugees to leave Tanzania without outright forcing them out. President Magufuli himself said these programmes incentivised refugees to remain in the country. A planned camp-wide food strike following the food-aid reductions and the cash transfer shutdown was swiftly squashed with the Tanzanian state by the threat of violence and shutdown of refugee resettlement opportunities (Boeyink Citation2020, 2021). The cash transfer shutdown came as a major financial shock to many cash recipients. As a Burundian woman, Victoria (interviewed February 2018), described:

since the shutdown, this has caused malnutrition for my family. Before I could vary my food, but now I can’t. I took out loans that I would pay back with the cash we received from cash from WFP [a TZS 55,000 (USD 23.92) loan]. Now I have to use capital from my business to pay.

[the shutdown] has affected my business so much. [With] the money I was receiving I was able to buy land to cultivate. When it stopped, I couldn’t rent as much land as before. I was farming two and a half acres but went down to one.

It affects my profit because instead of using [profit] for the future, I have to use it for household needs. People have bought less fish from my business than before. We must now reduce the price of fish because we will not have enough customers otherwise.

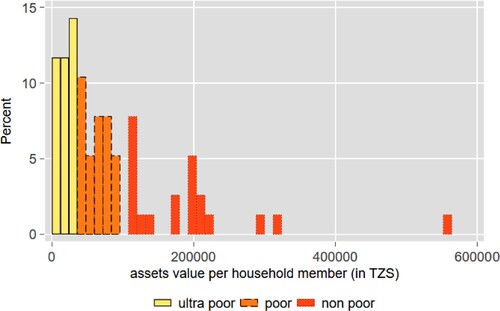

shows the sharp decrease in incomes after the August 2017 cash shutdown. It occurred simultaneously with large food ration cuts due to the ‘chronic underfunding’ of the Tanzanian refugee situation (UNHCR Citation2019). Between September and November 2017, WFP only provided 62% of 2,100 kcal per person. These cuts made the poor go hungry and forced households with livelihoods to divert capital from businesses to buy food (see ). Ration cuts also caused borrowing and debt. According to the CHS, those reporting borrowing money increased from 17.9% in 2016 to 26.8% in 2017. Those borrowing money to buy food rose from 79.3% to 91.5% due to the ration cuts in 2017 (WFP & UNHCR Citation2017). also shows the devastating effect of this second major shock: the closure of the common market in July 2018. Overall, sources of income appear volatile: casual labour and semi-skilled activities decrease over time as the conditions in the camp worsen. The main source of income left open is selling one’s own goods, including rations and other aid non-food items.

Figure 3. Monthly income per household. Note: 76 households (one wealthy outlier excluded), N varies slightly each month, and the figure should be considered as a general illustration.

Tracking the income of the groups labelled as ‘ultra-poor’, ‘poor’, and ‘non-poor’ over one year in , we find a similar erratic shape that reflects the significant camp income insecurity. The three groups seem to converge closer from January 2018, as less incentive and contract work became available to the ‘non-poor’. It was even the case for the richest household of the ‘non-poor’ group (one household was excluded from and because he was a severe outlier, repeatedly earning more than 2 million TZS monthly in incentive work and trade). In early 2018, some ‘ultra-poor’ households started earning more money by selling goods (mostly fish and beans) at the common market, however, such business crashed with the market closure. Income shocks do not translate into immediate changes in assets, but highlights the fragility of economic groups.

Spatial mobility, migration, and class

Tanzania’s encampment policy was designed to control and constrict refugee mobility, but people and goods still move in and out of the camp: 13.6% of the ultra-poor, 8.2% of the poor, and 12.3% of the non-poor reported leaving the camp. The dynamics are different between groups: the poorest are forced to be precariously mobile; missing out on economic opportunities by lacking the capital to seek markets outside the camp securely. In this section, we sketch a new research agenda, which we will develop in follow-up research. We argue that moving out of the camp–temporarily or through a longer-term migration–are determined by what Weber would call their ‘life chances’.

Short-term mobilities

Though legally circumscribed, the camp has no fencing or barriers and has many footpaths leading out to farms and neighbouring villages. As mentioned above, the poorest with little recourse to acquire capital, leave the camp to sell their labour on farms owned by Tanzanians or rented by fellow refugees. This is physically demanding labour and it comes at great risk. If caught by police, they must pay a bribe, which would take all their earnings or face a six-month prison sentence of hard labour and a fine. The same is true for those who cannot afford firewood or other cooking fuels. They must risk travelling increasingly further distances to collect their firewood illegally. They are stuck in a catch-22 situation demonstrating the incompatibility of self-reliance and encampment: they are provided food-aid in part because they are not allowed to work or leave the camp but must work or leave the camp to be able to cook such food.

For those in the ‘poor’ and ‘non-poor’ strata, short-term mobilities are also an option, but the terms are different. These refugees have enough money to rent land, sometimes pay labourers to cultivate, and pay the bribe necessary if caught by the police to evade prison. Other short-term mobilities, such as travelling to nearby towns and cities to buy cheaper wholesale products for camp businesses, receiving advanced medical care unavailable in the camp, or attending social events outside the camp are only available for those with the social and economic capital to do so. These mobile camp residents usually must attain a temporary pass from the camp commandant office through a bribe.

Long-term migrations

Migration aspirations and strategies to achieve them are classed affairs (Üstübici and Elçi Citation2022) and longer-term migrations of encamped refugees also occur along classed lines. Applying for resettlement through UNHCR requires economic, social, and cultural capital to navigate the system (Jansen Citation2008). This is true also for those leaving the camp on their own. In Nyarugusu, only those in the ‘non-poor’ category had any possibility of making arrangements to move to a safer third country when the asylum space in Tanzania started shrinking. This includes investment in land and businesses in Burundi for a ‘safer landing’ or attempts to make it in Dar es Salaam (Rudolf Citation2022). Self-resettling to Uganda, Kenya, Mozambique, or as far afield as South Africa was estimated to cost from TZS 200,000 to 5,000,000 (USD 86.96-2,173.98) depending on the distance, the costs of paying bribes to police and immigration officials, and the type of (often forged) identification documents required. Charles is a good example of such a privileged class. He made his wealth from being employed by an NGO as a skilled builder and from privately repairing homes for other refugees. To prepare for the eventual return, he purchased two acres of land in Burundi in September 2017 for BIF 2,600,000 (USD 1,384.46) and moved with his family there. Through his network he went alone to Juba, South Sudan where he makes a significant income as a builder. As of May 2022, he said plans to use his earnings and return to Burundi and start a large retail business near Bujumbura. Most refugees have far fewer options than Charles. For example, Jacques, the fish-seller introducing this article was on the cusp of moving his family to Uganda when we first met him in February 2017 but, by January 2022 the new camp policies described earlier in this paper had affected his once-lucrative business to the point where he could not afford the move and he remained in Nyarugusu.

Concluding remarks

This article describes the volatility of socio-economic groups in a Tanzanian refugee camp as they are caught in an interplay between humanitarian aid, government policy, and precarious camp economies. There are substantial debates about the usefulness of class theory in the African context (Kroeker, Scharrer, and O’Kane Citation2018), and our research invites caution when talking of social class in refugee camps, for two key reasons.

Firstly, the socio-economic stratification observed in the camp does not have the long-lasting nature of a social class that the classical theorists described. Burundian refugees arriving in 2015 primarily came as a singular class grouping of poor rural Hutus from the south and the journey often depleted them of most economic capital. The different levels of assets ownership and social connections that emerged in the camp are not calcified or lasting long enough to fit Marx, Weber, and Bourdieu’s analyses. Social capital, the major ‘class stratifier’ that Omata (Citation2017) described in Buduburam refugee camp, which was converted to remittances from resettled relatives and friends, plays a less significant role in Nyarugusu. Humanitarian and government actions further blur the lines between ephemeral socio-economic strata: cash transfers can aid class mobility and constitute start-up capital for establishing business ventures, but food ration cuts and host government assaults on markets have a profound flattening effect on embryonic classes as households’ economic buffers are depleted. Our research shows many ‘poor’ households, the potential ‘aspiring middle class’, ruthlessly pushed into precarious positions with a constantly reducing humanitarian safety net, as evidenced through Jacques’ case. The few socio-economic ‘elite’ groups we found were incentive workers and WFP food-aid traders. They are not enough to constitute an elite social class as even the availability of such a source of incomes fluctuates significantly.

Secondly, socio-economic stratification in the camp appears to include minimal explicit mechanisms of social distinction or a form of class consciousness that is core to Bourdieu’s theory (and something Marx deemed necessary for the proletariat to acquire). Those who are better off, in our ‘non-poor’ category, tend to occupy more exploitative positions (e.g. WFP food trading) but apart from a general sense of refugeedom consciousness, we found very few markers of class consciousness or active processes of social distinction over time within the camp. While Bourdieu’s social capitals theory, picked up by Van Hear (Citation2004) and Omata (Citation2017), is productive in explaining the stratification and weathering of shocks within the camp, we find less of Bourdieu’s distinction theory: refugees of all strata still live in the same place (though they have different amounts of assets), attend the same schools, associations, and churches, speak with the same accent, and spend the little money they have on similar items (albeit in different quantities). Some refugees occupy more enviable economic positions and have better ‘life chances’ through the market and spatial mobility opportunities (leaving the camp, temporarily or permanently) – however, it is unclear their status is any different from other camp residents, to use Weberian terms. The gift economy and mechanisms of ‘shared destitution’, coupled with a shared pre-displacement homogeneity in terms of ethnicity, socio-economic, and geographic profile, may explain this apparent lack of social distinction. This marks continuity with Scharrer and Suerbaum (Citation2022) who argue that changes in income-generating activities of Somali refugees in Nairobi do not allow class identity to form around work ethics.

Zooming out and considering the camp as a whole, ‘refugeedom’ class consciousness whereby camp residents attempt to assert their rights and their ‘worthiness’ as ‘suffering subjects’, does appear a useful lens. The policies of the Tanzanian state have placed refugees in a subaltern and excluded position (also see Hough (Citation2022) in this issue for a discussion of similar mechanisms in the very different context of South Korea). Moreover, the refugees we met also had a clear sense of being an exploited class due, reduced food rations and general camp welfare, the illegality of transgressing the camps’ borders, in combination with a surplus of potential labourers seeking employment. This results in refugees being a cheap source of labour, prime targets for bribes, and sellers of cheap humanitarian goods who cannot find alternative preferential markets (Boeyink Citation2020, 2021). When they protested their conditions after the cash transfer shutdown, they were squashed as a subaltern class by the Tanzanian state. This class consciousness is also shaped by the unique ‘life chances’ camp residents have through the access to a combination of social and economic capital – humanitarian capital – through welfarist (although diminishing) food-aid support, housing, and basic medical care, which most neighbouring Tanzanians cannot directly mobilise.

In our view, class analysis applied to a displacement situation depends on the broad class configurations before displacement, the national and international regimes of protection, and the political economy of aid. Even if a singular classical conceptualisation of class may have limitations and require splicing of multiple theories when applied to a camp like Nyarugusu, it is not a fruitless pursuit. For Liberians in Buduburam, class stratification was reproduced and calcified. For Nyarugusu residents, particularly Burundians, a mostly singular class fled together and experienced stratification once in the camp. State and (lack of) aid interventions have continually flattened downward such stratifications. Restrictive encampment as Nyarugusu demonstrates keeps the majority of people poor and dependent on aid. We invite future research to explore stratification and inequality in more depth through class theory concepts such as exploitation, consciousness, and distinction. Interesting comparative contexts could include a less restrictive asylum environment of Uganda, situations of greater longitudes of displacement such as the Palestinian situation, or in protracted internally displaced camps.

Acknowledgements

Our utmost thanks go to Kaskil Ibrahim, Dieudonne Makila, Upendo Upson, Safi Mgeni, Fredy Kaganga, Nibigiri Thamarie, and Niyokwizera Levis, their eagerness, expertise, and insights made this research possible. Special thanks to our UNHCR consultancy team, Juliana Masabo, Opportuna Kweka, Veronica Buchumi and Rosemary Msoka whom provided some of the inspiration for the present paper. Thanks to coordinators of this workshop and special issue, especially Tabea Sharrer and Christian Hunkler who provided many very helpful suggestions. Authors listed in alphabetical order (both authors contributed to drafting the different sections of the paper, as well as the subsequent revisions; see main text for data collection responsibilities; CB led the qualitative data analysis, JBF led the quantitative data analysis).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See Masabo et al. (Citation2018).

2 Note that not every household reported fortnightly, and the sample is not large enough to statistically represent the population of the camp.

3 For a more detailed account of farming see Boeyink (Citation2020).

4 See Boeyink (Citation2021) for a deeper analysis of this system of WFP food brokerage.

References

- Acker, Frank Van. 2005. “Where Did All the Land Go? Enclosure & Social Struggle in Kivu (DR Congo).” Review of African Political Economy 32 (103): 79–98. doi:10.1080/03056240500120984.

- Betts, Alexander, Louise Bloom, Josiah Kaplan, and Naohiko Omata. 2017. “Refugee Economies: Forced Displacement and Development.” In Refugee Economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198795681.003.0003.

- Boeyink, Clayton. 2019. “The “Worthy” Refugee: Cash as a Diagnostic of “Xeno-Racism” and “Bio-Legitimacy”.” Refuge 35 (1): 61–71.

- Boeyink, Clayton. 2020. “Sufficiently Visible/Invisibly Self-Sufficient: Recognition and Displacement Agriculture in Western Tanzania.” In Invisibility in African Displacements: From Marginalization to Strategies, edited by Jesper Bjarnesen, and Simon Turner, 66–84. London: ZED Books.

- Boeyink, Clayton. 2021. “On Broker Exploitation and Violence: From Madalali to Cartel Bosses in the Food Aid Resale Economy of Tanzanian Refugee Camps”. Development and Change.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson. New York: Greenwood Press. doi:10.4324/9780429494338.

- Chaulia, Sreeram Sundar. 2003. “The Politics of Refugee Hosting in Tanzania: From Open Door to Unsustainability, Insecurity and Receding Receptivity.” Journal of Refugee Studies 16 (2): 147–166. doi:10.1093/jrs/16.2.147.

- Collins, D., J. Morduch, S. Rutherford, and O. Ruthven. 2009. Portfolios of the Poor: How the World’s Poor Live on $2 a Day.

- Daley, Patricia. 1991. “Gender, Displacement and Social Reproduction: Settling Burundi Refugees in Western Tanzania.” Journal of Refugee Studies, doi:10.1093/jrs/4.3.248.

- Daley, Patricia. 2006. “Ethnicity and Political Violence in Africa: The Challenge to the Burundi State.” Political Geography 25 (6): 657–679. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2006.05.007.

- Deardorff Miller, Sarah. 2017. UNHCR as a Surrogate State: Protracted Refugee Situations. London: Routledge.

- Easton-Calabria, Evan, and Naohiko Omata. 2018. “Panacea for the Refugee Crisis? Rethinking the Promotion of “Self-Reliance” for Refugees.” Third World Quarterly 39 (8): 1458–1474. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1458301.

- Faist, Thomas. 2013. “The Mobility Turn: A New Paradigm for the Social Sciences?” Ethnic and Racial Studies, doi:10.1080/01419870.2013.812229.

- Falisse, Jean-Benoît, and René Claude Niyonkuru. 2015. “Social Engineering for Reintegration: Peace Villages for the “Uprooted” Returnees in Burundi.” Journal of Refugee Studies 28 (3): 388–411.

- Hear, Nicholas Van. 2004. “‘I Went as Far as My Money Would Take Me’: Conflict, Forced Migration and Class”. Centre on Migration, Policy and Society Working Paper, no. 6: 0–36.

- Hear, Nicholas Van. 2014. “Reconsidering Migration and Class.” International Migration Review 48 (s1): S100–S121. doi:10.1111/imre.12139.

- Hough, Jennifer. 2022. “The Contradictory Effects of South Korean Resettlement Policy on North Koreans in South Korea.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (20): 4922–4940. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2123436.

- Hunkler, Christian, Tabea Scharrer, Magdalena Suerbaum, and Zeynep Zanasmayan. 2022. “Spatial and Social Im/mobility in Forced Migration: Revisiting Class.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (20): 4829–4846. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2123431.

- Isabirye, Stephen B., and Kooros M. Mahmoudi. 2000. “Rwanda, Burundi, and Their ‘Ethnic’ Conflicts.” Ethnic Studies Review 23 (1): 62–80. doi:10.1525/esr.2000.23.1.62.

- Jansen, Bram. 2008. “Between Vulnerability and Assertiveness: Negotiating Resettlement in Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya.” African Affairs 107 (429): 569–587.

- Kroeker, Lena, Tabea Scharrer, and David O’Kane. 2018. Middle Classes in Africa: Changing Lives and Conceptual Challenges. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Lentz, Carola. 2015. “Elites or Middle Classes? Lessons from Transnational Research for the Study of Social Stratification in Africa”. 161. Working Papers of the Department of Anthropology and African Studies. Mainz.

- Masabo, Juliana, Opportuna Kweka, Clayton Boeyink, and Jean-Benoît Falisse. 2018. Socio-Economic Assessment in the Refugee Camps and Hosting Districts of Kigoma Region. Geneva: UNHCR.

- Omata, Naohiko. 2017. The Myth of Self-Reliance: Economic Lives Inside a Liberian Refugee Camp. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Purdeková, Andrea. 2017. “‘Barahunga Amahoro—They Are Fleeing Peace!’ The Politics of Re-Displacement and Entrenchment in Post-War Burundi.” Journal of Refugee Studies 30 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1093/jrs/few025.

- Riga, Liliana, Johannes Langer, and Arek Dakessian. 2020. “Theorizing Refugeedom: Becoming Young Political Subjects in Beirut.” Theory and Society 49 (4): 709–744.

- Rudolf, Markus. 2022. “Classified integration – Urban displaced persons in Dar es Salaam.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (20): 4905–4921. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2123435.

- Rutinwa, Bonaventure. 1996. “The Tanzanian Government’s Response to the Rwandan Emergency.” Journal of Refugee Studies 9 (3): 291–302. doi:10.1093/jrs/9.3.291.

- Scharrer, Tabea, and Magdalena Suerbaum. 2022. “Negotiating Class Positions in Proximate Places of Refuge: Syrians in Egypt and Somalians in Kenya.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (20): 4847–4864. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2123432.

- Schwartz, Stephanie. 2018. “Homeward Bound: Return Migration and Local Conflict After Civil War.” International Security 44 (2): 110–145.

- Turner, Simon. 1999. “Angry Young Men in Camps: Gender, Age and Class Relations among Burundian Refugees in Tanzania.” UNHCR Working Paper: New Issues in Refugee Research 9: 145–56.

- Turner, Lewis. 2015. “Explaining the (Non-)Encampment of Syrian Refugees: Security, Class and the Labour Market in Lebanon and Jordan.” Mediterranean Politics 20 (3): 386–404. doi:10.1080/13629395.2015.1078125.

- UNHCR. 2019. “Tanzania Country Refugee Response Plan.” Nairobi.

- Üstübici, Ayşen, and Ezgi Elçi. 2022. “Aspirations Among Young Refugees in Turkey: Social Class, Integration and Onward Migration in Forced Migration Contexts.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (20): 4865–4884. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2123433.

- WFP & UNHCR. 2017. Community Household and Surveillance (CHS) in North Western Tanzania.

- Wright, Erik Olin. 1985. Classes. London: Verso.

- Wright, Erik Olin. 2005. Approaches to Class Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.