ABSTRACT

At the extremes of the transnational cleavage in Western European democracies, voters for far-right and green parties tend to hold polarising immigration attitudes. Yet, the extent to which immigration concerns divide mainstream left and right voters, and drive vote-choice at the ballot box for mainstream parties, is under-researched. In this article, I disentangle both immigration attitudes and mainstream electorates to answer these questions. I show that immigration issues divide electorates within the mainstream left and right along educational lines. Yet, the divide between low-educated and highly-educated voters, in particular regarding their cultural immigration concerns, is larger for the mainstream left. Secondly, turning to the drivers of vote choice, I find that cultural immigration issues explain voting for the mainstream right, particularly for lower educated voters, whereas economic concerns are associated with voting for the mainstream left, despite education level. The paper contributes to ongoing debates about immigration issues and voting by recalibrating the academic focus towards mainstream party electorates and internal divisions therein.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

The politicisation of ‘immigration’ in recent years across western European democracies has proliferated itself most visibly in the party system (Grande, Schwarzbözl, and Fatke Citation2018). This politicisation has been associated with and illustrated by the soaring popularity of parties at either side of the ‘socio-cultural’ dimension of political conflict, also referred to as the ‘transnational cleavage’: On the ‘far right’, populist radical right parties (henceforth PRRPs) espouse nativist, anti-immigration politics, and on the ‘new left’ parties such as the Greens promote cosmopolitanism and an openness to immigration and multiculturalism (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018). In turn, those voters with strong policy preferences either for or against immigration have been associated with voting for one of these parties (Inglehart and Norris Citation2016; Kriesi et al. Citation2012).

However, we know less about the extent to which voters’ preferences towards immigration align with their choice at the ballot box for mainstream left and right parties: Some scholars argue that mainstream left (social democratic parties) electorates are more pro-immigration than their mainstream-right (Conservative or Christian democratic) counterparts (Lutz Citation2019; Natter, Czaika, and de Haas Citation2020), whilst others hold that the immigration issue divides party family electorates internally, and thus no clear divide between mainstream parties exists (Alonso and Claro da Fonseca Citation2012). Given evidence that immigration has become a ‘hot topic’ in party manifestos and debated at elections (Dancygier and Margalit Citation2019); that the mainstream left and right remain the most popular party families in Europe in terms of vote share (Hadj Abdou, Bale, and Geddes Citation2022; Hobolt and de Vries Citation2020, 24); the relationship between immigration and voting are of high importance to understand this critical area of political competition.

In this paper, I shed light on the ambiguous results of previous studies and seek to untangle the puzzle of immigration and mainstream voters, by asking two related questions: To what extent do immigration concerns (a) divide mainstream voters, and (b) drive vote choice for the mainstream left and right? I develop a theoretical framework for both questions with two main tools. Firstly, rather than being a homogenous ‘hot topic’, individuals hold subjective considerations about ‘cultural’ and ‘economic’ aspects of immigration (henceforth: ‘concerns’) (Lucassen and Lubbers Citation2012). Secondly, I turn to the extensive empirical literature which emphasises the role of education in reducing anti-immigration attitudes, to argue that education matters differently for these two immigration concerns. Across mainstream electorates, high education levels are associated with fewer immigration concerns. However, in line with ongoing research into the ‘progressive’s dilemma’ on the left, I posit that the educational divide is more prominent in the mainstream left than for the mainstream right, because of the divided electorate between socio-cultural professionals and blue-collar and routine workers (Gingrich and Häusermann Citation2015). In the second half of the empirical section, I turn to the question of whether immigration attitudes drive vote choice. Again, I argue that education level is crucial, but that it is non-uniform across the different electoral constituencies and types of concerns.

I test both the conceptual distinction between cultural and economic immigration concerns and these hypotheses using data from the European Social Survey (2014), firstly employing confirmatory factor analysis to show that differentiating between these two dimensions is analytically useful, and secondly using regression analysis to (a) assess divisions in the electorate and (b) analyse immigration concerns as the drivers of vote choice. Divides between higher and lower-educated voters are larger in the electorate of the mainstream left. Economic concerns appear to drive vote choice for the left more than the right, and cultural concerns drive vote choice for the right, but only for higher educated voters. Overall, this paper contributes to the literature by proposing a more granular approach to understanding the relationship between immigration attitudes and vote choice, which shouldenable patterns to be found at the mainstream too, beyond the extremes of the political spectrum.

2. Mainstream voters and immigration preferences

The relationship between immigration preferences and voting has been most prominently researched by scholars interested in PRRPs in Western Europe. These parties often mobilise voters on an anti-immigration platform (Kitschelt and McGann Citation1997), and their voters tend to hold strong anti-immigrant attitudes (Ivarsflaten Citation2008). This finding is corroborated by proponents of neo-cleavage theory, who argue that immigration is part of a new ‘socio-cultural’ dimension of political conflict which runs orthogonal to the economic left-right (also GAL-TAN or ‘transnational cleavage’, see Hooghe, Marks, and Wilson Citation2002, Citation2018). This dimension comprises authoritarian and traditional values on the one hand and libertarian and progressive ones on the other (Kriesi et al. Citation2012; Van Der Brug and Van Spanje Citation2009). Older, working-class voters with lower-education levels are more likely to host culturally authoritarian attitudes and younger, middle class progressive voters with higher-education levels are more likely to host liberal attitudes towards globalisation, immigration and traditional values (Häusermann and Kriesi Citation2015; Mau and Mewes Citation2012). The success of PRRPs on the one hand and ‘New Left’ parties on the other is in part due to the increased importance of this cleavage and the issues within the new socio-cultural dimensions for a large segment of the electorate.

Regarding mainstream (left and right) voters in Western Europe, the relationship between voters’ immigration attitudes and their partisan allegiances are less clear. Contrary to far-right and new-Left parties, mainstream right and left mobilise votes predominantly through other policy fields, such as left-right economic policiesFootnote1 (Cusack et al. Citation2006). Thus, individuals with pro-welfare state, pro-redistribution and taxation ideologies are more likely to vote for the mainstream left, with those preferring low state-intervention, less taxation and smaller welfare states voting for the mainstream right. Individuals with different incomes and education levels support these ideological standpoints (see Attewell 2021 for the heterogenous group of redistribution supporters).

This matters, because immigration preferences have been shown to be stratified along educational and class lines, and therefore mainstream electorates are internally divided on immigration issues. First and foremost, education level has been shown to reliably predict immigration attitudes, with higher educated individuals supporting open immigration policies and vice-versa (Bornschier et al. Citation2019; Hooghe and Marks Citation2018). However, both mainstream right and mainstream left parties rely on voters with mixed education backgrounds, thus potentially ‘cross-pressuring’ party elites on the issue of immigration. For social democratic parties, this cross-pressure comes from the blue-collar working-class constituency on the one hand and middle-class, higher-educated socio-cultural professionals on the other. The former are more likely to hold anti-immigration preferences (Achterberg and Houtman Citation2006), whereas, the latter are more progressive (Gingrich and Häusermann Citation2015). Similarly, a trade-off exists for the mainstream right, as their voter-base is divided between lower-educated petit-bourgeoisie with more culturally conservative views, and management classes with a more cosmopolitan outlook towards economically viable migrants (Bale Citation2008; Odmalm and Bale Citation2014).

2.1. Does immigration divide the mainstream electorate?

The first research question in this paper in light of the literature on the importance of educational divides for immigration issues, has a ready working hypothesis; Immigration divides voters within party electorates, such that high educated voters for left and right are more pro-immigration than lower-educated voters. Yet, it may be that certain immigration issues divide party electorates more than others and differently for the mainstream left and right.

To develop this point, recent advancements in the distinction between ‘cultural’ and ‘economic’ concerns of voters of PRRPs (Fetzer Citation2000; Rydgren Citation2008). Halikiopoulou and Vlandas (Citation2020) illustrate that a core group of PRRP voters host strong fears of ‘cultural differentialism’ (Swank and Betz Citation2003), such as how ethnic heterogeneity changes communities and fear of cultural outsiders. Yet, a larger group of potential voters are more concerned with the economic consequences of immigration (Citation2020, 8). The success of PRRPs is thus better explained by the perceived economic threat of immigrants to core and peripheral voters, than ‘cultural backlash’ alone (Rydgren Citation2008). Although contributing to scholarship of PRRP party behaviour, Halikiopoulou and Vlandas (Citation2020) do not directly consider the implications of dissecting immigration issues for other party electorates.

I propose that for mainstream voters, too, economic concerns are shared across different groups more than cultural concerns. This is because ego-centric (self-regarding) and socio-tropic (other-regarding) motivations are shared across educational groups. Ego-centric concerns about the economic impact of immigration include the personal impact of immigration on competition for jobs, driving down wages and competition for welfare payments (Kinder and Kiewiet Citation1981). Studies have shown that not only the lower educated (Hainmueller and Hiscox Citation2010), but also middle and highly educated individuals (Finseraas, Røed, and Schøne Citation2017) may perceive immigrants as a threat to their labour market stability, for instance. Higher-educated voters may work in skill-specific occupations, and thus feel vulnerable to changes in immigrant labour supply (Pardos-Prado and Xena, Citation2019). Other studies suggest that contextual factors such as high inequality (Magni Citation2021) and economic crises (Pecoraro and Ruedin Citation2016) can increase fears of highly-skilled individuals vis-à-vis their labour market security. Secondly, socio-tropic concerns, regarding the state’s capacity to sustain institutions and services, may be shared across educational groups, too. Helbling and Kriesi (Citation2014) and Valentino et al. (Citation2019) show that both high and low-educated natives are concerned about low-skilled immigrants, because they perceive that such immigrants will become a ‘burden’ on public finances, by paying fewer taxes and or becoming unemployed (Bansak, Hainmueller, and Hangartner Citation2016; Hainmueller and Hiscox Citation2010), reducing their deservingness to welfare benefits, as well (Helbling and Kriesi Citation2014, 597).

On the other hand, hosting cultural concerns about immigration have been shown to be driven primarily by socio-tropic drivers – namely, about worries about the effect of immigration on the national culture, community and tradition. Previous literature has highlighted that such concerns are more closely associated with socio-economic characteristics, in particular education level. Low education level is associated with xenophobia (how individuals feel about outsiders living in their communities, marrying into their family or being their boss) and socio-tropic concerns about the impact of immigrants on national culture (Hainmueller and Hiscox Citation2010). Conversely, higher-educated citizens are less likely to hold cultural fears about the cultural homogeneity of the nation state. Social psychologists have explained this association due to the increased cultural capital and appreciation of difference that is transferred through education (Valentino et al. Citation2019). In sum, whereas the literature on economic concerns illustrates that both high and low education groups share motivations to host concerns, cultural concerns are more divided along education lines. Thus, although high education is likely to predict support for immigration in general, and it is more associated with fewer concerns for cultural rather than economic concerns about immigration.

H1a: High education level is more negatively associated with cultural immigration concerns than for economic concerns about immigration.

As previously mentioned, mainstream right and left electorates include both high and low educated individuals. Therefore, one could assume that the effect of H1A holds across both electorates,

H1b: Higher educated mainstream left and right voters are less likely to hold cultural concerns than economic concerns about education.

On the other hand, it seems plausible to question whether the effect of high education on immigration attitudes is uniform across voters for mainstream right and left parties. In the hypotheses above, lower-educated voters are most likely to hold both cultural and economic concerns. Non-uniform effects are therefore best derived from considering whether certain sub-groups of higher-educated voters are also likely to be concerned about immigration.

Beginning with cultural concerns, these may be held by a sub-set of higher educated voters who are socialised into more culturally authoritarian and traditional values through the workplace: Here, they are ‘exposed to experiences of autonomy and control, and to a specific set of social interactions with superiors, colleagues, clients, patients or pupils’ (Oesch and Rennwald Citation2018, 4). Higher educated occupational groups that either impose authority on others, such as managers or large employers, are shown to value strong national identity, security and toughness on crime – typical culturally-authoritarian attitudes – more than socio-cultural professionals, the other high-education occupational group (Oesch and Rennwald Citation2018). This may suggest they harbour cultural concerns about immigration (Kitschelt and Rehm Citation2014). However, given their higher economic status, they are unlikely to perceive immigrants as a threat personally, and research shows that indeed many business owners and managers are likely to perceive at least labour migration as a net-economic positive (Walter Citation2010). Paradoxically, higher-educated voters with an interpersonal work logic – the socio-cultural professionals – who have a similar level of education but a lower income than managers (Engler and Zohlnhöfer Citation2018), are more likely to perceive immigration as a positive enhancement to society both culturally and economically, and relish the richness of multiculturalism and globalised societies (Breznau and Eger Citation2016; Häusermann and Kriesi Citation2015).

The literature on class and voting demonstrates, of the upper-educated, managers and employers are more likely to vote for the right, and socio-cultural professionals to vote for the left. Thus, a counter-hypothesis to H1B should be introduced regarding the extent that cultural and economic immigration issues divide voters. On the mainstream left, the educational divide in immigration attitudes between socio-cultural professionals and blue/white collar working classes is more likely to be stronger than for the mainstream right, where the managers and business owners are likely to meet lower-educated co-electorates with anti-immigration views. However, given that managers and business owners may perceive immigration as an economic positive, this difference will not hold for economic concerns. Therefore, I introduce a counter hypothesis for H1B just for cultural concerns;

H1C: The mainstream left electorate is divided internally along educational lines over cultural concerns more so than in the mainstream right electorate.

2.2. From divides to drivers

Regardless of how divisive immigration is for the mainstream electorate, to what extent do immigration concerns actually drive vote choice at the mainstream – if at all? As explored above, individuals whose vote choice is informed primarily by their immigration or cultural preferences are more likely to vote at the extremes of the socio-cultural dimension, and choose PRRP or Green parties (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018). At the mainstream, on the other hand, evidence suggests that the state-market dimension of political competition informs left-right vote-choice: Those voting for the mainstream left are more concerned about larger social spending, state control of the market and poverty, and for the right share beliefs in economic liberalism, low taxation and state intervention (Meltzer and Richard Citation1981). Following this line of argument, immigration concerns should not be significant drivers of vote choice at the mainstream. The above discussion suggests that immigration is likely to divide electorates and thus cancel out any predictive power of immigration concerns for vote choice. Hypothesis 2A thus reflects this null hypothesis:

H2A: Immigration attitudes do not explain vote choice for mainstream parties.

However, by differentiating between cultural and economic issues, and between different educational groups, a competing picture emerges. Firstly, it is well established that as an individual’s cultural concerns about immigration increase, they are likely to vote for parties on the radical right. Yet, this argument holds better for lower educated voters, as shown in recent studies of vote choice for PRRPs (Finseraas Citation2011; Gidron Citation2022), and non-voting (Evans et al. Citation2017). For higher educated voters, as theorised above, the explanatory power of immigration concerns may differ between mainstream left and right. Higher-educated voters with cultural concerns are more likely to vote right than left, given the association between cultural conservatism and mainstream right, but not left parties (Gidron Citation2022).

H2B: For lower educated voters, higher cultural concerns reduce the likelihood of voting for the mainstream left and mainstream right compared to other parties.

H2C: For higher educated voters, higher cultural concerns reduce the likelihood of voting for the mainstream left, but increase the likelihood of voting for the mainstream right compared to other parties.

I theorise a similar, yet reversed pattern, when it comes to economic concerns. Lower educated voters are the most likely to perceive immigration as a threat to their labour market status (Helbling and Kriesi Citation2014) and also to demand economic policies vis-à-vis immigrants such as welfare chauvinism, or the notion that immigrants should be excluded from the welfare state (Careja and Harris Citation2022). These policies are particularly popular among PRRPs, and thus I expect that higher individual economic concerns for lower-educated voters reduces their likelihood of voting in the mainstream (they may not vote at all, see Evans et al. Citation2017). On the other hand, higher-educated voters with economic concerns about immigration are less likely to vote for the mainstream right, because mainstream right parties are economically conservative and unlikely to offset any concerns regarding individual economic security. It is plausible that higher-educated individuals with economic concerns about immigration are concerned about their financial security, too, or that of their fellow citizens, and therefore, would continue to vote for the mainstream left to support expansive economic policies. Thus, the final two hypotheses are;

H2D: For lower educated voters, higher economic concerns reduce the likelihood for voting for both the mainstream left and mainstream right.

H2E: For higher educated voters, higher economic concerns increase the likelihood of voting for the mainstream left and decreases the likelihood of voting for the mainstream right.

3. Data, methods and estimation strategy

The empirical part of this paper, as the theoretical, is divided into two parts which nonetheless relate to one another. In both parts I use data from round seven of the European Social Survey (ESS Citation2018) to measure the key independent and dependent variables. This dataset enables thirteen western European states to be compared; Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. Other countries in the dataset were omitted because it was essential to be able to compare parties broadly in terms of important cleavages (economic, religious, cultural), social structures and political systems, which are differently construed in eastern and Central Europe (Rovny Citation2014). I chose this wave of the ESS due to the ‘immigration’ module and to tackle the theoretical expectations regarding PRRPs, who have gained popularity since 2010 across the countries in the sample.

In the statistical analyses, I exclude individuals not able to vote and those that did not vote from the analysis. Following row-wise exclusion of missing values, the final sample is of 17,102 individuals across the fourteen countries.

3.1. Immigration concerns

In the first section, the dependent variable is immigration concerns, which are divided into two – cultural and economic – and thereby the analysis is conducted on the two separately. In the second section, these concerns become independent variables. Previous studies have used just one survey item to measure these differing immigration attitude dimensions – most prominently the following ESS items which is in each round from 2002 to 2018. Cultural concerns are measured using the item (a) is your country’s cultural undermined (0) or enriched (10) by immigration, and to measure economic concerns, the following; (b) is immigration bad (0) or good (10) for your country’s economy (Lucassen and Lubbers Citation2012; Rydgren Citation2008). They are positively correlated (0.63) across ESS 2002–2008 (Halikiopoulou and Vlandas Citation2020). Lucassen and Lubbers (Citation2012, p. 559) showed that the cultural concerns item also loaded on the ‘economic’ concerns dimension for the ESS1 wave, suggesting caution when only using one measure of economic and one measure of cultural concern.

Given the first aim of this paper – to demonstrate the analytical leverage of two-dimensional immigration concerns – I choose to work with the 2014 wave of the ESS which includes more questions on immigration, so as to construct a more robust measure of cultural and economic concerns. As a first step, I theoretically considered which items in the ESS survey would fit into ‘cultural’ and ‘economic’ concerns. I conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of covariance between the items to generate the latent variables to be used in the regression analysis.Footnote2 The final model with loadings and measure-of-fit indices are shown in . All the variables were scaled similarly from 0 to 10 such that 0 is ‘no concerns’, and 10 ‘very concerned’. Following the factor analysis, I create two latent, continuous measures for cultural and economic concerns respectively, using the ‘predict’ function in the R package ‘Lavaan’ to generate loadings for each voter.

Table 1. Confirmatory factor analysis results.

3.2. Vote choice

In the first section, voting behaviour is used as one of the independent variables to explore the divisions within electorates around cultural and economic immigration concerns, principally for mainstream-right or mainstream-left party electorates. I measure vote behaviour using the ESS item which indicates which party they voted for at the last election, using party-family categorisations from the ParlGov dataset (Döring and Manow Citation2017).Footnote3 The party categories possible from this coding exercise are PRRP and Green or ‘New Left’ parties on the extremes of the transnational cleavage, as well as other left parties (socialist or communist) and the mainstream parties of the centre right (Conservative and Christian Democrat) along with Liberals and, finally, the centre-left Social Democrats. As my research question and theoretical framework focus on the centre-right and left, in part one, I construct a categorical variable between voting for the mainstream left, mainstream right and other parties. In part two, where vote choice is the dependent variable, I am interested in predicting voting for one party compared to all others, and thus create two dummy variables; voting for the mainstream left (1/0) and right (1/0).

3.3. Class and education

Following other studies, I measure higher education by using a dummy variable for those who have completed upper secondary education (either academic or vocational) and those who have not. In the first section, the final measure is a dummy variable for lower education, given the theoretical expectation that education is negatively related to immigration concerns, and in the second section, the dummy variable is for upper secondary (1) or no upper secondary (0). Furthermore, occupational class is used to differentiate within education groups further. I measure occupational class by adopting Oesch’s 8-class scheme which divides voters into the following groups; manual and routine (clerks) working class, technical (semi) professionals, socio-cultural professionals, managers and small/large employers (see Engler and Zohlnhöfer Citation2018, see online appendix Table OA3B).

Further control variables for the regression include age and gender and subjective income self-assessment. Since the 1980s, women have increasingly voted for the mainstream left (Emmenegger and Manow Citation2014) and are more likely to be open to immigrants, whereas age is positively related to immigration concerns (Lancaster Citation2022) and voting mainstream right (Hadj Abdou, Bale, and Geddes Citation2022). I include a self-reported measure of economic insecurity provided in the ESS, which asks ‘how do you feel about your households’ income nowadays’? Respondents then select from ‘Living comfortably’, ‘coping’, difficult’, or ‘very difficult’, to assess whether perceived risk of economic insecurity explains cultural or economic immigration concerns. I insert a dummy variable for trade union membership (also historical) and unemployed status in the last five years in the analysis in section one to assess whether these factors play a role in divisions between and within electorates. Online appendix Table OA3 shows the summary statistics.

4. Analysis

4.1. Part 1: how divisive is immigration for mainstream voters?

In the first empirical section, I test hypotheses 1A-C using OLS regressions of education, class and vote choice on two dependent variables, (a) Cultural and (b) Economic immigration concerns. Given that these two concern variables are latent factor loadings on a continuous scale, the analyses are completed using OLS estimators in a number of models which introduce the variables stepwise. presents the results of these OLS regressions, reporting heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors, country dummies and standardised coefficients.

Table 2. The effect of education on cultural and economic concerns.

For each dependent variable (cultural and economic concerns), the table presents standardised coefficients of three models. Model 1 and 4 present full models without country fixed effects. Models 2 and 5 present the full models including country fixed effects. Models 3 and 6 present the fully models with interaction effects between education and vote-choice, and country fixed effects.

Turning to H1A, I expected that education level explained much of divisions in the general population over immigration concerns, but that economic concerns were less divided than cultural concerns. Comparing the standardised coefficients in models 2 and 5, moving from upper to lower education increases the cultural concerns by 0.523, compared to 0.480 on the economic concerns scale (both significant to 99% confidence level). This supports H1a, and the finding is shown to be robust in a number of alternative specifications shown in the online appendix, including using multilevel-modelling instead of country dummies to account for cross-country variation (OA5-6) and using single item measures for cultural and economic immigration concerns rather than factor loadings (OA7-8).

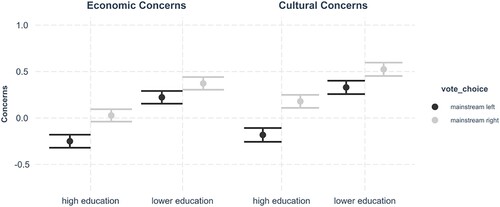

Next, I introduced two competing hypotheses regarding the effect of education on immigration attitudes within electorates, to assess whether the divisive effect of education has is uniform (H1B), or (H1C) that education explains more polarisation over cultural concerns within the mainstream left electorate than within the mainstream right electorate. To test these hypotheses, I turn to models 3 and 6 which include interaction terms between education and voting behaviour. For both cultural (model 3) and economic (model 6) concerns, the interaction effects for voting mainstream right are significant and strongly negative, suggesting that the effect of low education on immigration concerns is lower for the mainstream right for both economic and cultural concerns. Low education level increases cultural concerns by 0.346 and economic concerns by 0.345 for mainstream right voters. For the mainstream left, the education effect is larger, as low education increases cultural concerns by 0.512 and economic concerns by 0.473. This means that the effect of education does vary across electorates and we can reject H1B and at least partially supports H1C, which is shown figuratively in (a,b) which presents the marginal effects of education by left and right mainstream voters for cultural and economic immigration concerns in turn.

Figure 1. (a) The effect of education on economic concern by vote choice (mainstream left and right). Marginal Effects plotted from coefficients taken from model 3 in . (b) The effect of education on cultural immigration concerns by vote choice. Marginal effects plotted from coefficients in model 6 in .

These plots show that, indeed, mainstream left voters are the most divided over immigration concerns: the highly educated within the mainstream left are the only group consistently below 0 and thus with the lowest concerns (more positive attitudes) towards immigrants for both cultural and economic concerns, which contrasts with the blue- and white-collar workers who vote for the mainstream left. In general, mainstream right voters are less divided in terms of education. Other interesting patterns are shown – namely that whereas mainstream left voters appear more negative in terms of economic concerns, mainstream right voters are more negative in terms of cultural concerns. The coefficient for economic concerns for highly educated mainstream right voters crosses 0 and thus suggests that these individuals harbour potentially positive views regarding economic migration, perhaps driven by their perception of the net-positive benefit of labour migration for businesses. Lower educated mainstream right voters are also less likely to perceive immigrants as a threat to their economic security, as their choice to vote for the right rather than left signifies that they are more interested in economic liberal policies. This suggests that the divisions between voters on the mainstream right is driven by both higher cultural concerns from the higher educated as well as lower economic concerns from both education groups.

The theoretical framework expected that these differences in attitudes were driven by occupational class. To check this, I conduct similar regression analysis, using the Oesch-8 occupational class categories instead of education to observe differences across class groups. The results of these regressions are printed in the appendix Tables OA15 and OA16.

There are a number expected and surprising findings from the class-based anlaysis. Firstly, as expected, middle-class voters (socio-cultural professionals and managers) for the mainstream Left are significantly less likely than the blue collar and routine working classes to hold both cultural and economic concerns. This reflects the literature on the ‘trade-off’ that social democratic parties face between different class groups on the socio-cultural dimension (Kymlicka Citation2015). Often under-researched, this divide is also seen for the mainstream right – as middle-class voters here (socio-cultural professionals and managers) also have fewer concerns than small employers and working-class groups. The finding above – that economic concerns are less troubling for both low and high educated groups within the mainstream right – is matched here: Managers and socio-cultural professionals confidence intervals lap 0, whereas for cultural concerns they are positive.

However, despite previous research suggesting otherwise, there are residual, unexplained differences within the class groups, too – such that socio-cultural professionals voting for the mainstream right are more concerned about immigration, all else held equal, than the mainstream left socio-cultural professionals. Even controlling for subjective income perception, given that the socio-cultural professionals voting for mainstream left parties have lower incomes, the act of voting for the left rather than right seems decisive. Although the space needed to discuss this is not available in this paper, this poses an interesting research avenue in the future, particularly regarding the size of the relative class groups within electorates. Overall, the divisions between leftist socio-cultural professionals and working classes regarding cultural concerns support the theoretical underpinning of H1C. It should also be added that these groups compose a larger segment of the electorate than in the mainstream right, and thus their polarising attitudes have more implications for the electoral cross-pressures facing political parties.Footnote4

4.2. Part 2: does immigration drive vote choice?

The purpose of part one was to unpick the relationship between education and immigration attitudes between mainstream left and mainstream right electorates. In part two, the analysis tests the hypotheses of how well immigration concerns explain vote choice.

To do so, I employ linear probability models to regress immigration preferences on vote choice vote choice dummy variables, which has been used extensively in recent and similar studies (Czymara and Dochow Citation2018; Gidron Citation2022; Gidron and Mijs Citation2019). Particularly when fixed-effects models and interaction effects are involved, the interpretation of logistic coefficients are very difficult, particularly regarding their standard errors (Emmenegger and Manow Citation2014, 178), which has led scholars to choose linear probability models where appropriate (Ai and Norton Citation2003). To verify the main effects found in the analysis below, I conduct a number of robustness checks on different samples and with different constructions of the dependent variable. Furthermore, I present findings for alternative estimation strategies (mixed-effects models with random slopes and intercepts, logistic regression). All robustness checks and alternative models are found in the online appendix Tables OA9-OA16.

OA4 in the online appendix presents the findings of the regression analysis. The models all include heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors and country fixed effects. Interaction effects are introduced for the latter two models for each vote-choice dependent variable (mainstream left and mainstream right).

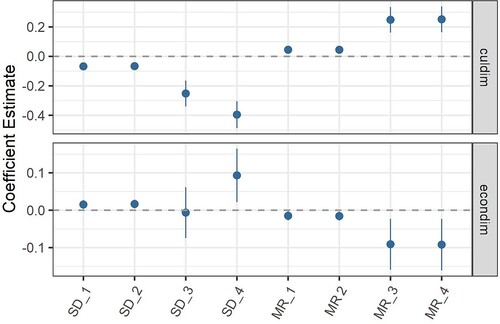

Hypotheses H2A-H2B can be approached in turn. shows a coefficient plot for the main models and a number of the different specifications discussed above, and presents the coefficients for the relationship between immigration attitudes and vote choice. Firstly, contrary to H2A, immigration attitudes do relate to vote choice at the mainstream. Indeed, all else held equal (SD_1 and MR_1 in , cultural concerns panel), a one standard-deviation increase in cultural concerns reduces the likelihood of voting for the mainstream left by 6.7%, and increases the likelihood of voting for the mainstream right by 4.5%. The picture is less telling for economic concerns (SD_1 and SD_2, economic concerns panel) – but in general one standard deviation increase in economic concerns increases the likelihood of voting for social democrats by 1.7% and reduces the likelihood of voting for the mainstream right by 1.6%. Although these coefficients are small, they are significant and all conventional levels. These findings imply that a sub-set of mainstream left voters hold stronger concerns about the economic effects of immigration than others, all else held equal, and within the mainstream right there are more prominent cultural concerns about immigration (Hainmueller and Hiscox Citation2010).

Figure 2. Robustness checks, Multiple coefficient plots from a mixture of models. 1 = country fixed effects (OA4), _2 = multilevel model (OA5-6), _3 = logistic (OA9), _4 = multilevel logistic (OA10).

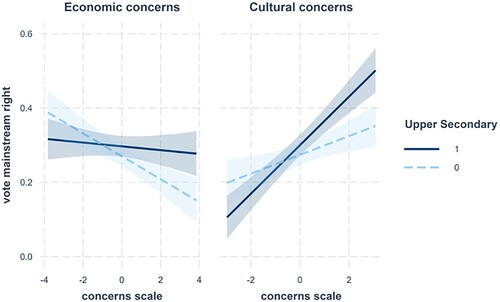

Hypotheses 2B-2E to shed more light on whether immigration attitudes have non-uniform effects on voting behaviour along educational lines. Firstly, turning to cultural concerns, H2B posited that lower-educated voters shift away from the mainstream right and left, the higher their cultural concerns about immigration are, and that for highly-educated voters, cultural concerns increase their likelihood to vote for mainstream right (H2C). The findings of the interaction effects presented in models 2 and 5 (from table OA and shown graphically in figure OA1) offer partial evidence to support these hypotheses. The negative direction of the coefficient for cultural concerns on voting social democrat holds across both low and highly-educated voters, as shown by the non-significant interaction effect. Both of these groups are less likely to vote social democrat with strong cultural concerns. However, as shown in (a) below, the positive effect of cultural concerns on voting mainstream right holds across both high and lower education groups, albeit in higher educational groups the effect is much larger, particularly at the higher end of the cultural concerns scale it is significantly different from that of the lower educated (<0.9). This suggests that H2B can only by partially supported, as lower educated voters with cultural concerns may stick to the mainstream right but not the mainstream left. Conversely, this finding supports H2C, that higher educated voters stick to mainstream right parties if they hold cultural immigration concerns.

Regarding economic concerns, H2D expected that individuals with low education and economic concerns are less likely to vote for the mainstream left and right, for similar reasons as for cultural concerns: Namely, lower educated voters are more likely to shift to vote for the radical right or not to vote at all. This can only be partly-confirmed: (b) presents the significant and negative interaction effect between holding economic concerns and voting mainstream right for lower-educated individuals, offering support for H2D. However, as shown in Figure OA1, economic concerns are positively related to voting for mainstream left parties despite education level: Both high and low educated voters with economic concerns are more likely to vote for the mainstream left. This means that H2D can only be confirmed for the mainstream right. This then, conversely, offers support for part of H2E, which expected highly educated voters with economic concerns to vote for the mainstream left, and not for the mainstream right. Regarding the latter, their likelihood to vote for the mainstream right seems unaffected by economic immigration concerns – as shown by the flat curve in (b).

Figure 3. (a) The effect of economic immigration concerns on voting mainstream right, by higher/lower education. Interaction effects plotted from the OA4 model 6. (b) The effect of cultural immigration concerns on voting mainstream right, by higher/lower education. Interaction effects plotted from the OA4 model 5.

Overall, these findings suggest that holding cultural concerns is positively associated with voting for the mainstream right for both high and low-educated voters, and negatively for the mainstream left for both groups (although this association is not significant). Holding economic concerns, conversely, are negatively related to voting for the mainstream right for lower educated voters and positively related to voting for the mainstream left for both low and high educated individuals.

One can extrapolate that working-class voters stick to the mainstream Left regardless of their economic concerns about immigration, as a function of their continued support for the promise of economic protection in the face of globalisation and immigration – the so-called ‘compensation thesis’ (Rodrik Citation2018). On the other hand, should they hold strong cultural concerns about immigration, they are unlikely to vote for the mainstream left and rather vote either for the radical or, as shown here, mainstream right. Among highly-educated groups, higher economic concerns about immigration are positively associated with voting for the left, which implies potentially that ego-centric concerns about their own economic security drive both voting for the left and holding economic concerns, although this remains to be tested empirically. Cultural concerns are positively related with voting for mainstream right, and negatively with the mainstream left for higher-educated, however. Those groups of the middle classes, such as some managers and socio-cultural professionals with more traditional views, are more likely to vote to the mainstream right if they are concerned about the cultural effects of immigration. Yet, as suggested in the theoretical section, their likelihood to vote mainstream right is not affected by economic concern – likely because, they are neither materially likely to benefit from reduced labour market competition or increased welfare spending on natives, nor do they support restrictions on immigration – if anything, labour migration of high skilled immigrants is preferred by this group (Hainmueller and Hiscox Citation2010).

To come briefly to the robustness checks, I ran different regression models and used different iterations of the dependent variable to corroborate my findings. As shown in figure 3, apart from the logistic regression on voting social democrat, the models all show uniformity in direction and significance of the effect of immigration attitudes on vote choice. Firstly, instead of using country-fixed effects, critics may argue for incorporating the homogeneity within country context using hierarchical models, in which individuals are nested in level-2 units. Online appendix Tables OA11 and OA12 present the results of mixed effects regression models, including both random slopes for countries and random-intercepts for cultural and economic concerns for the social democrat (OA11) and mainstream right (OA12), which confirm the results found in the main text here. Secondly, a number of critics of linear probability modelling argue that binary outcome variables require estimating logistic regression models. Online appendix Tables OA9 and OA10 demonstrate that the use of logistic models does not change the direction of the coefficient, although for the economic dimension it becomes insignificant.

5. Conclusion

This paper tackled the question of whether immigration attitudes, so-often the focus of studies of extreme right and left parties in western Europe, are associated with voting for mainstream left and mainstream right parties, too. I first investigated whether immigration issues divide constituencies of voters within and between parties at the mainstream. Here, I followed the assumption that parties are ‘cross-pressured’ – such that that lower-educated voters for both party families are more sceptical towards immigrants, whereas higher-educated voters are less so. I find that the size and extent of the cross-pressure is the strongest for mainstream left parties and cultural concerns about immigration. Higher-educated voters for the mainstream right also tend to harbour cultural (and some economic) concerns about immigration, which makes the divides within the right smaller than the left.

In the second section, I asked whether immigration attitudes drive vote choice. I find that higher educated voters with cultural concerns are more likely to vote for the right and less likely to vote for the left, although with economic concerns the reverse is true. I find partial support for the hypotheses that lower-educated voters with higher concerns choose to vote elsewhere: For the Left, this holds for cultural concerns, yet, lower educated voters remain loyal to the left despite high economic immigration concerns. This implies that despite immigration, other issues (such as welfare or economic policies) motivate lower-educated to stick with mainstream-left parties, countering Gidron’s findings that it only takes one right-wing position to incentivise a move to the right (Citation2022). For the mainstream right, this holds for economic concerns, but not for cultural concerns – where a positive relationship between concerns and voting mainstream right is shown. This is likely to reflect that for the petit-bourgeoisie – a core, low-educated group of voters for the mainstream right – are economically more secure than the corner stone low educated voters for the social democrats, the blue collar and routine workers (Oesch and Rennwald Citation2018). However, a more detailed exploration of these findings is beyond the scope of this paper.

There are a number of limitations to this study. The first, is that due to data availability, it is impossible to approximate whether immigration issues drive or shape voting intentions, or whether these positions are rather secondary to other issues such as welfare, economic spending or the environment. Future studies or experimental designs could incorporate a measure of salience into the survey, which would enable scholars to approximate whether immigration attitudes are priorities for voters of left and right centre parties, not only their positions (Häusermann et al. Citation2020). Secondly, I was unable to extend the analysis across waves and to more countries in the ESS, due to the number of questions needed to construct the latent factors. This would have enabled a more advanced approach to estimating vote switching between elections suggested by the interaction effects.

These conclusions have clear ramifications for research into parties and their immigration politics. For one, the results suggest that immigration issues do not belong solely to the ‘cultural’ sphere of political conflict. Economic and cultural issues clearly have different electoral repercussions, and by separating them, scholars of parties and voters can draw conclusions about which arguments lead to electoral success. Secondly, middle class voters for both sides of the centre are important, and drive the polarisation of cultural concerns in particular. Echoing findings by Oesch and Rennwald (Citation2018), richer, higher educated, manager voters of the mainstream right are likely to hold less culturally liberal attitudes than similar skilled individuals voting mainstream left. However, they are more ambivalent when it comes to economic issues. Thirdly, the finding that the voters of mainstream right parties are, on average, more suspicious of cultural benefits of immigration is in line with recent scholarship on the party ‘supply’ side. Both left and right-wing parties, following an economic logic, overlap in their positions towards setting up controls on labour migration. Yet, the integration of asylum seekers and other migrants into society has a whole has been shown to divide left and right parties in their manifestos and policy agendas (Akkerman Citation2015; Lutz Citation2019). Thus, the jury remains out on whether electoral demands play out in the electoral arena of party politics, and future studies could link survey and party positional data to explore such avenues.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (818.5 KB)Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of the paper profited from the close reading and comments of Nate Breznau, Romana Careja, Jakob Henninger, Philip Manow, Elias Naumann, Friederike Römer and Arndt Wonka. Thanks to the participants of the members of the socio-cultural diversity group at the MPI-MMG, the Political Economy working group 2021 at University of Bremen, the Methods and Design Workshop at UNC Chapel Hill in 2020 and ECPR General Conference 2020 participants for their comments on previous drafts and ideas. All mistakes and omissions are my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 There are exceptions to this rule of course, such as the Danish Social Democrats among others who have used immigration as a key issue in recent elections.

2 CFA was useful to confirm the divides made in immigration items based on their belonging to economic or cultural dimensions, i.e. labour market issues are theoretically economic, whereas religious issues area cultural.

3 A full list of parties can be found in the online appendix Table OA3.

4 In the online appendix figure OA2, the real (weighted) class compositions of the electorates show that socio-cutlural professionals make up 27% (ML) and 24% (MR), and small employers make up 6% (ML) and 15% (MR). The combined working class (routine and blue collar) make up over 40% of the ML and only 29% of the MR electorate.

References

- Achterberg, P., and D. Houtman. 2006. “Why Do So Many People Vote “Unnaturally”? A Cultural Explanation for Voting Behaviour.” European Journal of Political Research 45 (1): 75–92.

- Ai, C., and E. C. Norton. 2003. “Interaction Terms in Logit and Probit Models.” Economics Letters 80 (1): 123–129.

- Akkerman, T. 2015. “Immigration Policy and Electoral Competition in Western Europe: A Fine-Grained Analysis of Party Positions Over the Past Two Decades.” Party Politics 21 (1): 54–67.

- Alonso, S., and S. Claro da Fonseca. 2012. “Immigration, Left and Right.” Party Politics 18 (6): 865–884.

- Attewell, D. 2021. “Redistribution Attitudes and Vote Choice Across the Educational Divide.” European Journal of Political Research.

- Bale, T. 2008. “Turning Round the Telescope. Centre-Right Parties and Immigration and Integration Policy in Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 15 (3): 315–330.

- Bansak, K., J. Hainmueller, and D. Hangartner. 2016. “How Economic, Humanitarian, and Religious Concerns Shpae European Atttitudes Toward Asylum Seekers.” Science 534 (6309): 217–229.

- Bornschier, S., C. Colombo, S. Häusermann, and D. Zollinger. 2019. “How ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ Relates to Voting Behavior – Social Structure and Social Identities in Swiss Electoral Politics.” In Working Paper (Issue June).

- Breznau, N., and M. A. Eger. 2016. “Immigrant Presence, Group Boundaries, and Support for the Welfare State in Western European Societies.” Acta Sociologica (United Kingdom) 59 (3): 195–214.

- Careja, R., and E. Harris. 2022. “Thirty Years of Welfare Chauvinism Research: Findings and Challenges.” Journal of European Social Policy 32 (2): 212–224.

- Cusack, Thomas, T. Iversen, and P. Rehm. 2006. “Risks at Work: The Demand and Supply of Government Redistribution.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 22 (3.

- Czymara, C. S., and S. Dochow. 2018. “Mass Media and Concerns About Immigration in Germany in the 21st Century: Individual-Level Evidence Over 15 Years.” European Sociological Review 34 (4): 381–401.

- Dancygier, R., and Y. Margalit. 2019. “The Evolution of the Immigration Debate: Evidence from a New Dataset of Party Positions Over the Last Half-Century.” Comparative Political Studies 53 (5): 734–774.

- Döring, H., and P. Manow. 2017. “Is Proportional Representation More Favourable to the Left? Electoral Rules and Their Impact on Elections, Parliaments and the Formation of Cabinets.” British Journal of Political Science 47 (1): 149–164.

- Emmenegger, P., and P. Manow. 2014. “Religion and the Gender Vote Gap: Women’s Changed Political Preferences from the 1970s to 2010.” Politics and Society 42 (2): 166–193.

- Engler, F., and R. Zohlnhöfer. 2018. “Left Parties, Voter Preferences, and Economic Policy-Making in Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 0 (0): 1–19.

- European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure, (ESS ERIC). 2018. “ESS7 - Integrated File, Edition 2.2 [Data set].” Sikt - Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. doi:10.21338/ESS7E02_2.

- Evans, G., J. Tilley, G. Evans, and J. Tilley. 2017. The New Politics of Class: The Political Exclusion of the British Working Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fetzer, J. S. 2000. “Economic Self-Interest or Cultural Marginality? Anti-Immigration Sentiment and Nativist Political Movements in France, Germany and the USA.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 26 (1): 5–23.

- Finseraas, H. 2011. “Anti-Immigration Attitudes, Support for Redistribution and Party Choice in Europe.” Changing Social Equality: The Nordic Welfare Model in the 21st Century, 23–44.

- Finseraas, H., M. Røed, and P. Schøne. 2017. “Labor Market Competition with Immigrants and Political Polarization.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 12 (3): 347–373.

- Gidron, N. 2022. “Many Ways to be Right: Cross-Pressured Voters in Western Europe.” British Journal of Political Science 52 (1): 146–161.

- Gidron, N., and J. J. B. Mijs. 2019. “Do Changes in Material Circumstances Drive Support for Populist Radical Parties? Panel Data Evidence from the Netherlands During the Great Recession, 2007–2015.” European Sociological Review 35 (5): 637–650.

- Gingrich, J., and S. Häusermann. 2015. “The Decline of the Working-Class Vote, the Reconfiguration of the Welfare Support Coalition and Consequences for the Welfare State.” Journal of European Social Policy 25 (1): 50–75.

- Grande, E., T. Schwarzbözl, and M. Fatke. 2018. “Politicizing Immigration in Western Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 0 (0): 1–20.

- Hadj Abdou, L., T. Bale, and A. P. Geddes. 2022. “Centre-Right Parties and Immigration in an Era of Politicisation.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (2): 327–340.

- Hainmueller, J., and M. J. Hiscox. 2010. “Attitudes Toward Highly Skilled and Low-Skilled Immigration: Evidence from a Survey Experiment.” American Political Science Review 104 (1): 61–84.

- Halikiopoulou, D., and T. Vlandas. 2020. “When Economic and Cultural Interests Align: The Anti-Immigration Voter Coalitions Driving Far Right Party Success in Europe.” European Political Science Review. 7, 12 (4): 427–448.

- Häusermann, S., M. Ares, M. Enggist, and M. Pinggera. 2020. Mass Public Attitudes on Social Policy Priorities and Reforms in Western Europe. Welfare Priorities Dataset 2020. (Issue June).

- Häusermann, S., and H. Kriesi. 2015. What do Voters Want? In The Politics of Advanced Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Helbling, M., and H. Kriesi. 2014. “Why Citizens Prefer High-over Low-skilled Immigrants. Labor Market Competition, Welfare State, and Deservingness.” European Sociological Review 30 (5): 595–614.

- Hobolt, S. B., and C. de Vries. 2020. Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2018. “Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (1): 109–135.

- Hooghe, L., G. Marks, and C. J. Wilson. 2002. “Does Left/Right Structure Party Positions on European Integration?” Comparative Political Studies 35 (8): 965–989.

- Inglehart, R., and P. Norris. 2016. “Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash.” SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Ivarsflaten, E. 2008. “What Unites Right-Wing Populists in Western Europe?” Comparative Political Studies 41 (1): 3–23.

- Kinder, D. R., and R. D. Kiewiet. 1981. “Sociotropic Politics: The American Case.” British Journal of Political Science 11 (2): 129–161.

- Kitschelt, H., and A. J. McGann. 1997. The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Kitschelt, H., and P. Rehm. 2014. “Occupations as a Site of Political Preference Formation.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (12): 1670–1706.

- Kriesi, H., E. Grande, M. Dolezal, M. Helbling, D. Hoeglinger, S. Hutter, and B. Wuest. 2012. Political Conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kymlicka, W. 2015. “Solidarity in Diverse Societies: Beyond Neoliberal Multiculturalism and Welfare Chauvinism.” Comparative Migration Studies 3 (1): 17.

- Lancaster, C. 2022. “Value Shift: Immigration Attitudes and the Sociocultural Divide.” British Journal of Political Science (52): 1–20.

- Lucassen, G., and M. Lubbers. 2012. “Who Fears What? Explaining Far-Right-Wing Preference in Europe by Distinguishing Perceived Cultural and Economic Ethnic Threats.” Comparative Political Studies 45 (5): 547–574.

- Lucassen, G., and M. Lubbers. 2012. “Who Fears What? Explaining Far-right-wing Preference in Europe by Distinguishing Perceived Cultural and Economic Ethnic Threats.” Comparative Political Studies 45 (5): 547–574.

- Lutz, P. 2019. “Variation in Policy Success: Radical Right Populism and Migration Policy.” West European Politics 42: 3.

- Magni, G. 2021. “Economic Inequality, Immigrants and Selective Solidarity: From Perceived Lack of Opportunity to in-group Favoritism.” British Journal of Political Science 51 (4): 1357–1380.

- Mau, S., and J. Mewes. 2012. “Unraveling Working-Class Welfare Chauvinism.” In Contesting Welfare States: Welfare Attitudes in Europe and Beyond, edited by S. Svallford, 119–157. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Meltzer, A. H., and S. F. Richard. 1981. “A Rational Theory of the Size of Government.” Journal of Political Economy 89 (5): 914–927.

- Natter, K., M. Czaika, and H. de Haas. 2020. “Political Party Ideology and Immigration Policy Reform: An Empirical Enquiry.” Political Research Exchange 2 (1): 1735255.

- Odmalm, P., and T. Bale. 2014. “Immigration into the Mainstream: Conflicting Ideological Streams, Strategic Reasoning and Party Competition.” Acta Politica 50 (4): 1–14.

- Oesch, D., and L. Rennwald. 2018. “Electoral Competition in Europe’s New Tripolar Political Space: Class Voting for the Left, Centre-Right and Radical Right.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (4): 783–807.

- Pardos-Prado, S., and C. Xena. 2019. “Skill Specificity and Attitudes Toward Immigration.” American Journal of Political Science 63 (2): 286–304.

- Pecoraro, M., and D. Ruedin. 2016. “A Foreigner Who Does not Steal my Job: The Role of Unemployment Risk and Values in Attitudes toward Equal Opportunities.” International Migration Review 50 (3): 628–666.

- Rodrik, D. 2018. “Populism and the Economics of Globalization.” Journal of International Business Policy 1 (1–2): 34–43.

- Rovny, J. 2014. “Communism, Federalism, and Ethnic Minorities: Explaining Party Competition Patterns in Eastern Europe.” World Politics 66 (4): 669–708.

- Rydgren, J. 2008. “Immigration Sceptics, Xenophobes or Racists? Radical Right-Wing Voting in Six West European Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 47 (6): 737–765.

- Swank, D., and H. Betz. 2003. “Globalization, the Welfare State and Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe.” Socio-Economic Review 1 (2): 215–245.

- Valentino, N. A., S. N. Soroka, S. Iyengar, T. Aalberg, R. Duch, M. Fraile, K. S. Hahn, et al. 2019. “Economic and Cultural Drivers of Immigrant Support Worldwide.” British Journal of Political Science 49 (4): 1201–1226.

- Van Der Brug, W., and J. Van Spanje. 2009. “Immigration, Europe and the “New” Cultural Dimension.” European Journal of Political Research 48 (3): 309–334.

- Walter, S. 2010. “Globalization and the Welfare State : Testing the Micro-Foundations of the Compensation Hypothesis.” International Studies Quarterly 54 (2): 403–426.