?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Previous literature has intensively examined gender differences in housework hours among couples. However, analyses on immigrant couples are rare, despite the highly uneven division of their household labor. By testing competing theoretical explanations, this study focused on the impact of immigrant wives’ labor market integration on couples’ division of housework time. Using longitudinal representative data for Germany from 1995–2019, we applied fixed effects estimations to examine the effect of immigrant and native-born wives’ income and labor market entry on the housework time of both wives and husbands. Immigrant wives barely adjusted their housework times due to relative or absolute income changes, which can be explained by immigrant couples’ traditional orientation together with their lower social and labor market integration. Among native-born wives, increasing housework time with increasing relative income – a behavior also possibly determined by traditional gender values – was observed only when they earned more than 60 percent of the couples’ total income. Furthermore, the high gender differences in housework time gave immigrant husbands flexibility to respond to their wives’ labor market integration, as proposed by the relative resources perspective.

Introduction

Compared to native-born individuals, immigrants face greater challenges in labor markets in most industrial countries (OECD Citation2019). In particular, immigrant women usually perform worse in the labor market than both immigrant men and native-born women (Hayfron Citation2002). The migration literature has explained these ‘double disadvantages’ of female immigrants with the fact that women are more likely to be tied movers (Mincer Citation1978; Shauman and Noonan Citation2007). The main argument of this literature is that women most often have a secondary role in family migration decisions, resulting in their lower human capital and earning potential in the destination country (e.g. Cooke et al. Citation2009). The double disadvantage of female immigrants was particularly pronounced among married couples due to female immigrants’ greater focus on nonmarket work (Donato, Piya, and Jacobs Citation2014; Grönlund and Fairbrother Citation2022).

In fact, however, less is known about the nonmarket time allocation of immigrants (Ribar Citation2013), the examination of which is likely crucial for understanding the integration process, especially that of female immigrants (e.g. Zaiceva and Zimmermann Citation2014). This is because the relation of housework and economic integration works both ways. According to Becker’s (Citation1985) theoretical elaborations, women engaged in housework tasksFootnote1 exert less effort on each hour of work in the labor market. Negative effects of housework on labor market performance may also result from employer discrimination against women, as discussed among others by Browne and Misra (Citation2003). However, the more challenging the female labor market integration is, the more uneven the couple’s division of housework may become (Shelton and John Citation1996), which can further promote the couple’s uneven division of paid working time. Furthermore, following Hochschild and Machung (Citation1989), many studies emphasise women’s ‘second shift’ stressing their duties to care for household and children after they come home from work. Accordingly, we seek to understand whether and how the allocation of housework differs between native-born and immigrant couples due to their economic integration.

By comparing immigrant and native-born couples, we aim to understand whether standard theoretical models predict immigrant wives’ housework time similar to native-born wives’ housework time as well as the linkage to economic integration. The literature on household division of labor mostly relied on economic approaches, particularly the ‘relative resources’ perspective, to comprehend the role of uneven access to economic resources on decision-making power in couples (Bittman et al. Citation2003). Additionally, the ‘autonomy perspective’ emphasises the autonomous adjustment of housework in relation to wives’ absolute levels of income (Gupta Citation2007). Both the relative resources perspective and the autonomy perspective suggest that there is a decrease in wives’ housework time with an increase in their absolute or relative earnings, which should hold for both immigrant and native-born couples. However, the observation that women are still doing more housework when they earn more than their husbands stresses that economic-based explanations may in some cases fail to explain the division of time spent on housework within the couple. This phenomenon was explained in terms of a ‘doing gender’ perspective that has linked females’ larger share of housework to the work’s ‘feminine’ nature and spouses’ gender identity in the marriage (West and Zimmerman Citation1987). Couples’ housework may be inelastic to their earnings because gender norms prevent them from deviating from the traditional gender division of labor or they may even use housework to achieve gender accountability when violating the traditional couple structure. This ‘reaction’ of wives may differ between immigrants and native-born wives given that immigrants tend to arrive as tied movers (Mincer Citation1978; Shauman and Noonan Citation2007) and often have been shown to have a more traditional gendered division of labor (Blau et al. Citation2020).

The literature on the determinants of housework division among immigrant couples is rather scant. For instance, qualitative studies of Haddad and Lam (Citation1994) and Ng and Ramirez (Citation1981) described a very uneven division of paid and unpaid work among immigrant couples and that the wives’ dependencies on their husbands highly increased due to tied migration. Blau et al. (Citation2020, for the US) and Frank and Hou (Citation2015, for Canada) showed that the extent of gender equality of the source country influences the division of housework tasks among immigrant couples. Cross-national literature further revealed that apart from individual factors, macrolevel determinants such as the countries’ female labor force participation, social policies or gender norms influence the housework distribution between spouses in the expected way (Fortin Citation2005; Fuwa Citation2004; Kan, Sullivan, and Gershuny Citation2011; Mandel, Lazarus, and Shaby Citation2021). In line with the findings in this literature, we recognise the importance of considering the heterogeneity of immigrants’ source countries when comparing the allocation of housework patterns between native-born and immigrant couples.

We studied the role of spouses’ economic contribution – in absolute and relative terms – for the allocation of housework between native-born and immigrant couples in Germany. Specifically, we examined the effect of wives’ absolute and relative earnings as well as their labor market entry resulting in a change in absolute and relative earnings. We explored whether their financial resources influence immigrant wives’ bargaining power concerning time spent on housework (washing, cooking and cleaning) when controlling for mechanical time constraints. We used data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (v36; SOEP Group Citation2021) and two integrated studies, the IAB-SOEP Migration Sample (Brücker et al. Citation2014) and the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees (Brücker, Rother, and Schupp Citation2017), and enriched it with the country-of-origin-specific ratio of female to male labor force participation rates in the year before immigrant wives in our sample from the corresponding country were interviewed for the first time (FMR-LFP; The World Bank Citation2021). We compared immigrant wives coming from countries with an FMR-LFP below 50 percent, between 50 and 75 percent, above 75 percent and native-born wives. The FMR-LFP shapes immigrant wives’ labor force participation (Blau et al. Citation2020) and can be understood as a proxy for cultural determinants. As a moderator effect, it may influence the impact of individual income on housework (Fuwa Citation2004). The analyses applied fixed effects (FE) estimations to take into account individual- and couple-specific factors that may influence earnings, paid work and housework time as well as their interrelation.

Our study contributes to the previous literature in several ways. Most previous studies interested in cultural determinants of nonmarket time allocation compare couples’ behavior in a cross-national way (Fortin Citation2005; Fuwa Citation2004; Kan, Sullivan, and Gershuny Citation2011; Mandel, Lazarus, and Shaby Citation2021). Instead, we compare immigrant couples from different countries with native-born couples in Germany. Comparable studies for the US (Blau et al. Citation2020) and Canada (Frank and Hou Citation2015) rely on Ordinary Linear Regression (OLS); in contrast, we rely on longitudinal data and methods to control for unobserved time-invariance heterogeneity. Recognising the heterogeneity of immigrants’ source countries, we compare the allocation of housework patterns between immigrant couples originating from countries with high, medium and low female labor supply and native-born couples. We also test the robustness of our results with those using other groupings, such as another indicator of gender inequality, a division in geographic regions or one by migration motive. We also contribute to the flourishing literature that has empirically tested competing hypotheses about who within a couple is doing the housework, why, and what this division conveys (Becker Citation1985; Bianchi et al. Citation2000; Gupta Citation2007; Hook Citation2017; Killewald and Gough Citation2010). By comparing immigrant and native-born couples’ allocation of housework time, we apply and retest the existing theories to immigrant couples. Our results point to the insufficiency of the existing theories to address immigrants’ couples’ division of housework labor necessity for additional explanations. While our main analyses focused on routine housework (such as cooking, washing and cleaning), our conclusions hold when also considering childcare and tasks that are more flexible in rescheduling and are more often performed by men than by women, such as garden work or repair tasks.

Before presenting the hypotheses about how theoretical perspectives may differently apply to different population groups, we describe the German context and why the country is an appropriate case study.

The German case

The German female labor force participation was 56 percent (of the female population aged 15+, compared to the male labor force participation of 67 percent) in 2019, comparable to other EU or high-income countries (The World Bank Citation2021). This also applies to the female participation rate relative to men’s with 83 percent in 2019. Within Germany, the female participation rate has always been and still is lower in the western region. In the former German Democratic Republic, it was expected that mothers would return to work soon after they gave birth, whereas in the Western region, it was more common for mothers to stay at home for a longer period after giving birth, which also led to high regional differences in the supply of childcare slots. The German government has therefore heavily expanded day care in recent years and introduced in 2013 a legal claim for public childcare for children aged one or two years (Müller and Wrohlich Citation2016).

Apart from differences between East and West Germany, there are also large differences in female labor force participation between native-born and immigrant women (Sprengholz et al. Citation2021). Many studies have emphasised the relevance of integration policy for their integration success. While denying being an immigration country for many years, Germany started to introduce different integration policy measures since 1998 (Geißler Citation2014) and liberalised its immigration law for third country immigrants after 1999. Nevertheless, as shown in this study, the division of paid and unpaid work in 2019 in Germany is still much more uneven between immigrants than between native-born men and women, which may have been highly influenced by their integration.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Most studies on the effect of economic resources on the housework division within a couple take resources as given, although some studies do analyze the effect of changes in employment due to promotion and termination (Foster and Stratton Citation2018; Gershuny, Bittman, and Brice Citation2005; Voßemer and Heyne Citation2019). Three theoretical approaches, the relative resources, gender, and autonomy perspectives, assume different effects of wives’ earnings or their labor market entry on their own and their spouse’s housework time. Our theoretical elaborations about how these perspectives may differently apply to different population groups are organised around three main hypotheses.

Relative resources perspective

As a leading theoretical construct, the relative resources perspective suggests that the spouse holding more power from economic resources can minimise his or her participation in undesirable activities such as housework or childcare. Brines (Citation1994) explained the possibility of minimising housework time – usually that of husbands – with the dependency of married women due to their lower income. However, formally, the perspective is gender neutral: spouses take responsibility for housework because they are economically dependent and cannot bargain out (Voßemer and Heyne Citation2019). The same applies to migration background, although the dependency on husbands’ income can on average be assumed to be higher among immigrant wives who often arrive as tied movers than among native-born wives (Mincer Citation1978; Shauman and Noonan Citation2007).

Hypothesis 1: Independent of their migration status, wives’ relative income shares and their labor market entry (changing their income share) decrease their own and increase their husbands’ housework hours.

Gender perspective

Many studies have found evidence for the relative resources perspective up to the point where both spouses contribute equally to income. Among the small share of couples where women outperform men in terms of household income, some studies have revealed that husbands (Brines Citation1994) or both husbands and wives (Bittman et al. Citation2003; Evertsson and Nermo Citation2004; Greenstein Citation2000) act to neutralise nonnormative provider roles when they do housework. West and Zimmermann (Citation1987) discussed how housework may be a symbolic enactment that helps women and men define and express gender relations within households.

Attitudes in line with the gender perspective highly depend on norms and values, which are, for immigrants, a much and for decades debated aspect. According to the classical view, immigrants will adapt the destination country’s culture, which then supports their economic and social integration. However, systematic empirical evidence about immigrants’ values and changes in values over time after migration is rare. Kalmijn and Kraakamp (Citation2018) emphasised that norms and values in Muslim countries – where many immigrants of European countries come from – are generally more traditional than in the Western world. Khattab, Johnston and Manley (Citation2018) assumed that Islam restricts women’s activities but also that the way different people interpret Islam may restrict their engagement in paid work. Nevertheless, norms and values can still highly differ within the Western or non-Western home country groups. Cultural values and how individual income influences housework can also differ within regions. To reduce the risk of an arbitrary grouping of countries with respect to cultural values, which in our analysis is assumed to be a moderator effect between individual income and housework, we differentiate immigrant wives by the women’s labor force participation shares relative to that of men of a specific country (FMR-LFP). Female labor force participation can influence not only wives’ labor force participation in the destination country but also how strong gender ideologies encourage a traditional division of labor (Blau et al. Citation2020; Fuwa Citation2004). It can also be shown that there is a high correlation for most countries between the FMR-LFP and a gender inequality index from Human Development (UNDP) considering the three dimensions of reproductive health, empowerment and the labor market. Comparable studies on this issue used such an index to proxy cultural values and to examine its effect on housework (Blau et al. Citation2020; Fuwa Citation2004; Mandel, Lazarus, and Shaby Citation2021).

In sum, following the gender perspective, we expect that the impact of earnings on housework is low or even has a counterintuitive impact, meaning that women increase their housework time when they earn a lot. We further expect that the gender perspective applies differently to native-born and immigrant couples and that among immigrants, cultural factors, proxied by the FMR-LFP, function as moderators concerning the relevance of the gender perspective:

Hypothesis 2: Wives’ relative income shares and their labor market entry (changing their income share) have minor to no impact on the couples’ housework division or even increase housework engagement, especially among immigrant wives and among those from countries with a low FMR-LFP.

Autonomy perspective

Despite their differing predictions, both of the above presented theories are grounded on the notion that wives’ relative earnings decisively affect their share of housework. More recent studies, however, have cast doubt on the suitability of wives’ relative earnings for examining the division of housework time within a couple (Hook, Citation2017; Killewald & Gough, Citation2010). Alternatively, Gupta (Citation2007) emphasised women’s autonomous agency not only in terms of time spent on housework but also, as other studies found, in terms of expenses for outsourced tasks such as housekeeping services and eating out. The author showed that women’s relative earnings have little explanatory value for housework hours when women’s absolute earnings are also accounted for. For weekdays, Hook (Citation2017) found a negative but diminishing effect of women’s earnings and employment hours on their housework hours. Furthermore, the autonomy perspective – like the relative resources perspective – is formally gender blind, assuming an independent relationship between individuals’ earnings and the time they spend on housework. This formal blindness also applies to the migration status.

Hypothesis 3: Independent of migration status, wives’ own absolute income has a greater effect on their time spent on housework than their relative income (as a share of the couple sum).

Gupta (Citation2007) further criticised the relative resources and gender perspective for their failure to consider differences between high- and low-income couples. Women’s housework adjustments may be lower when they earn more than their husbands because they belong disproportionately to poorer couples or because, as Killewald and Gough (Citation2010) concluded, high-income households may have already outsourced housework tasks as much as possible. The possibility of outsourcing housework tasks may also be lower for immigrants with low social integration and fewer so-called ‘weak ties’ (see Granovetter Citation1973) to the local community.

Data and methods

Data and sample

For our empirical analyses, we rely on data from the German Socio Economic Panel (v36; SOEP Group Citation2021) and two integrated studies, the IAB-SOEP Migration Sample (Brücker et al. Citation2014) and the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees (Brücker, Rother, and Schupp Citation2017). SOEP is an ongoing representative yearly panel survey of private households in Germany launched in 1984 in West Germany and enlarged to include East Germany after 1990. The SOEP oversampled immigrants of Turkish, Greek, Italian, Spanish, and ex-Yugoslavian origin (in 1984; Sample B) and immigrants who arrived in Germany after 1984 mainly from Eastern Europe and from other developing countries (in 1994–1995; Sample D). The IAB-SOEP Migration Sample is a joint project of the Institute for Employment Research (IAB) and the SOEP. The data were launched in 2013, and the targeted population consists of individuals who immigrated to Germany between 1995 and 2013 and of second-generation individuals born after 1976 (Samples M1 and M2). The IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees is a joint project of the IAB, the Research Centre on Migration, Integration, and Asylum of the Federal Office of Migration and Refugees (BAMF-FZ) and the SOEP. The data were launched in 2016 to represent the refugee migration arrived in Germany between 2013 and 2016 (Samples M3-M5). The remarkably large SOEP sample together with integrated studies allow the investigation of different migrant groups and the linkage of information of spouses who live together in one household. The survey contains yearly information about time spent on primary daily activities, employment behavior and sociodemographic variables (for more information, see SOEP Group Citation2021).

For our analyses, we use data from 1995 to 2019. To incorporate partners’ information, our analytical sample considers only women living in a household together with their legally married or cohabiting male partner, who also participated in the personal interview. We did not distinguish between legally married and cohabiting partners, and for brevity, we used the terms ‘wives’ and ‘husbands’ for both types of couples. Given our focus on labor market integration, we restricted our sample to wives aged between 20 and 64 years. We excluded second-generation migrants, native-born women with an immigrant husband and immigrant women with a native-born husband, as well as couples where wives’ or husbands’ country of origin was missing. Couples with missing information on housework hours (our main outcome of interest) were also excluded.Footnote2 Finally, we confined our sample to couples observed at least twice in the panel. explains the sample restrictions in more detail.

Table 1. Information about cases excluded from the original data.

It is questionable whether we should include nonemployed wives (34 percent of observed wives in the analytical sample are not employed) and wives with nonemployed husbands (applicable to 22 percent of the observed wives). For instance, Hook (Citation2017) emphasised that breadwinner households may display compensatory gender behavior, although those households complicate the analysis. Theoretically, choosing not to work (or actively searching for a job) or having a low income relative to their husband may have different implications. Thus, the main analysis of this study included nonemployed wives and wives with nonemployed husbands, coding for them as having an economic resource score of zero, whereas a robustness check restricted the sample to couples where both spouses are participating in the labor market. Following Brines (Citation1994), we additionally conducted a robustness check, excluding women with a disabled husband or a husband of pensioner age. After all restrictions, our analytical sample contained 113,531 observations of 15,602 wives in couples (see ).Footnote3

In our analyses, we differentiated between native and immigrant wives originating from countries with an (1) FMR-LFP below 50 percent, (2) an FMR-LFP between 50 and 75 percent, (3) an FMR-LFP above 75 percent and (4) native-born wives. To create a consistent indicator across the sample and assuming cultural factors as inert, we consider the FMR-LFP in the year before immigrant wives from the specific country were first observed in the data (The World Bank Citation2021).Footnote4 For instance, immigrant wives from Italy were first surveyed in 1994. Hence, all immigrant wives from Italy were assigned to the FMR-LFP group between 50 and 75 percent based on the value of 1994. Zooming on source country composition within groups, we observe that many Arabic countries, such as Afghanistan, Iran and Syria, have FMR-LFPs below 50 percent, and India, Kosovo, Sudan and Turkey also belong to this group. The second group with FMR-LFP between 50 and 75 percent contains Central and Southern American countries (e.g. Argentina, Brazil and Cuba), some European countries (e.g. Belgium, Croatia, Greece) and some African countries (e.g. Nicaragua, Niger and Trinidad). Finally, many other high-income and EU countries have an FMR-LFP above 75 percent. At the same time, this group also includes African countries, such as Ghana, Kenya and South Africa. For the country grouping based on the FMR-LFP, see Table S1 in the Supporting Information.Footnote5

Measures

Dependent variable

For our analyses, we defined four dependent variables: wives’ and husbands’ hours spent on housework and wives’ and husbands’ change in housework hours between two survey waves. Using absolute hours is standard practice in the literature evaluating theoretical perspectives about the division of housework time among couples (Bianchi et al. Citation2000; Bittman et al. Citation2003; Evertsson and Nermo Citation2004; Gupta Citation2007; Hook Citation2017; Voßemer and Heyne Citation2019). The reason is that the relative time of each partner spent on housework conflates the time of each spouse. The wives’ share can increase because they do more housework, their husbands do less, or both. To define the variables on housework hours, we rely on self-reported information about time spent on housework (washing, cooking and cleaning), i.e. primary tasks that constitute a daily routine and may compromise labor market performance. Note that the SOEP questionnaire also surveyed time spent per working day on other housework-related activities such as childcare, repairs, garden work and errands. We do not consider childcare in the main analyses but as a robustness check because (1) it is less comparable to other housework tasks for a couple’s bargaining process; (2) it produces an emotionally laden public good (Foster and Stratton Citation2018); (3) in contrast to housework, at least some of its aspects are perceived as rewarding and enjoyable (Sullivan Citation2013); and (4) it can, to a certain degree, be performed simultaneously with other tasks. Nevertheless, childcare represents a relevant area for doing gender (Hook Citation2017; West and Zimmerman Citation1987). Repair and garden work may be an important area of housework that men spend more time on than women, although these tasks can easily be performed in the evening or postponed to more suitable times and are, therefore, less compromising for labor market performance. In robustness checks, we also report findings for the wives’ time spent on childcare and their husbands’ time spent on the sum of washing, cooking, cleaning and repair/garden work (refer to Online Supporting Information, Tables S7–S8). Finally, we did not consider errand activities because trips to government agencies correlate with the migration background or other migration-relevant issues, such as duration of stay.

Independent variables

To test the explanatory power of the suggested theories, we proceeded as follows. First, we focused on the impact of wives’ financial resources on their and their husbands’ hours spent on housework. Second, we examined the impact of wives’ labor market entry on their and their husbands’ change in housework hours.

In both analytical steps, we tested whether economic factors (Hypotheses 1 or 3) or gender values (Hypothesis 2) determined the housework time of wives and husbands. Accordingly, to measure absolute earnings, we considered the net monthly income, top coded to the 99th percentile and adjusted to inflation based on the consumer price index of 2015. In the estimation, we measured the income in 100 Euro. The incomes of the nonemployed were coded to zero. We measured relative income in terms of the individual shares of the couples’ total income from labor (see, e.g. Bianchi et al. Citation2000).

Various authors have argued that autonomy, relative resources, and gender arguments do not equally apply for every part of the absolute or relative income distribution (Hook, Citation2017; Killewald and Gough, Citation2010; Greenstein, Citation2000; Evertsson and Nermo, Citation2004 and Bittman et al., Citation2003). We considered absolute net income and the relative income share additionally to the linear term in nonlinear terms by including the squared variables in case the resulting significant effects indicated a nonlinear effect on housework time.Footnote6

Wives’ labor market entry is an indicator variable equal to one for wives who were full- or part-time employed at the time of the survey but were not employed the year before. Note that vocational education was considered full-time employment, whereas marginal or irregular employment was considered nonemployment.

Control variables

Fixed-effect models eliminate the problem of omitted variable bias due to time-constant unobserved heterogeneity, which excludes the possibility of controlling for time-constant variables such as country of origin. To alleviate time-varying unobserved heterogeneity, we considered the following control variables in our analyses. The gender gap in paid labor time is a common explanation for the gender gap in housework time (Bianchi et al. Citation2000; Bittman et al. Citation2003; Evertsson and Nermo Citation2004). Hence, to distinguish the effects of time and financial resources (Killewald and Gough Citation2010), we considered the individual and spouse time availability as the discrete (wives’/husbands’) actual weekly working hours top coded to the 99th percentile, with a maximum of 70 hours for both wives and husbands. The working hours of nonemployed individuals are correspondingly equal to zero. In the analyses of labor market entry resulting in changes in absolute housework hours, we considered the change in weekly working hours between the current and previous waves. In the models on wives’ housework time, we used her information for the individual-specific control variables, whereas in those on husbands’ housework time, we used his information.

Family income may have negative effects on housework time because the greater financial resources of the household increase the probability of using domestic services, and lower-class couples may be less egalitarian in their values (Brines, Citation1994). However, since housework income is influenced by individual income, it is problematic to control for both variables in the models examining the effect of income on housework. Therefore, we controlled in all specifications for other household (hh) income, measured as monthly net income from all sources for all household members (after deductions for taxes and social security) subtracting both spouses’ individual income. The total household income is top coded to the 99th percentile, adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index of 2015 and divided by 100 to account for small effects.

We further considered common controls used in prior empirical studies on the household division of labor (e.g. Brines Citation1994; Evertsson and Nermo Citation2004; Hook Citation2017; Voßemer and Heyne Citation2019). Specifically, we controlled for wives’ or husbands’ age, wives’ or husbands’ health (self-evaluated in five categories) and size of the housing in square meters, divided by 10 to consider small effects. We used indicator variables for wives’ or husbands’ being currently in education and for using domestic services. Kühhirt (Citation2012) showed that parenthood leads to a long-term increase in women’s housework time. We considered the age of the youngest child in the household (distinguishing between 0–2, 3–5, 6–17, 18 or more years), the household size (number of persons living in the household) and to control for those who are not working and unemployed for shorter than one year or who have to top up their income with social benefit, we included an indicator variable about wives’ or husbands’ receiving German unemployment benefit (section one, ALG1). For the analyses on labor market entry resulting in a change in absolute housework hours, we controlled for wives’ and husbands’ changes in working hours instead of absolute working hours, for a change in the number of persons in the household (distinguishing between increased, decreased, no change, and missing values) instead of household size and additionally for husbands being employed. To account for regional disparities in labor market conditions, we included in all specifications German federal state fixed effects. Furthermore, survey year fixed effects account for common time trends.

See for the distribution of the dependent, independent and control variables in the pooled sample, differentiating between the three FMR-LFP-based immigrant wives’ groups and native-born wives.

Table 2. Unweighted descriptive statistics, Source: SOEP, 1995–2019.

Analytical strategy

The following empirical analyses are conducted separately for the three groups of immigrant and native-born wives. As presented in the section on Data and Sample, we distinguished immigrant groups based on the FMR-LFP in the source country with (1) the FMR-LFP below 50, (2) the FMR-LFP between 50 and 75 and (3) the FMR-LFP above 75 percent.

We applied FE estimations to control for individual-specific factors, which possibly influence earnings, paid work and housework time as well as their interrelation. OLS estimation may lead to biased and inconsistent coefficients due to the endogeneity of the earning variable resulting from unobservable factors such as skills, norms or values. Furthermore, simultaneity between earnings and housework (as discussed in the introduction) may lead to biased and inconsistent coefficients.

Due to a considerable share of zeros, especially among the housework hours of female partners, one could also apply a Tobit model to account for the missing conditional normal distribution of housework, leading to inference with only asymptotic justification and negative predicted values for housework. Stewart (Citation2013) nevertheless demonstrated that estimated marginal effects from Tobit models based on time-use data are biased in contrast to ordinary least squares estimates and that the extent of the bias varies with the fraction of zero-value observations.

We estimated a regression model including a dummy variable for each wife i in the model. That is,

(1)

(1) with

measuring for the first part of the multivariate analysis wife i’s own housework hours or those of her husband in year t.

represents a vector of independent and control variables, which are assumed to be all independent of all

because of the inclusion of the wives’ fixed effects

.

For the second part of the multivariate analysis on the effects of labor market entry, we used the same model as presented in (1), but in this case, equaled the difference in housework time between t and t-1, and instead of income in t, the explanatory variable was an indicator of wives’ labor market entry.

To address item nonresponse, we applied multiple imputation using chained equations (van Buuren Citation2012). We estimated 10 imputed datasets with complete information. Following Rubin’s (Citation1987) approach, we then combined the results of the analyses of each dataset.

Results

Average differences in wives’ and husbands’ allocation of housework time

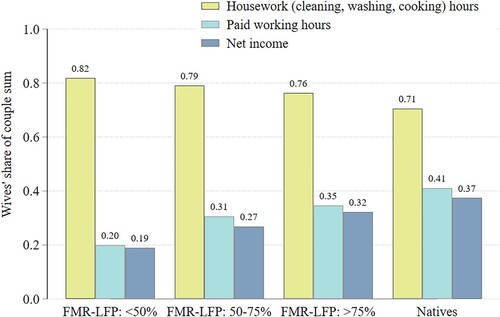

We start with baseline analyses of the differences in wives’ and husbands’ time spent on unpaid and paid work as well as their net income across the four defined population groups. depicts the wives’ share of the total time the couple spends on housework per working day, of the paid weekly working hours and of the couple’s monthly net income for 2019.

Figure 1. Share of couples’ total time spent on housework and on paid work and share of couples’ total net income from labor, 2019 (weighted results).

Overall, we observed that wives accounted for the majority of the couples’ total time spent on housework and correspondingly spent less time on paid work and earned less of the couples’ total income. This was particularly true for immigrant couples with wives born in countries with a low FMR-LFP (below 50%). Hence, there appears to be a link between a traditional division of paid and unpaid work among couples and the FMR-LFP of the wives’ country of origin. In the group of wives from countries with the lowest relative participation rates, wives accounted for 82 percent of the couples’ total time spent on housework, 20 percent of time spent on paid work and earned 19 percent of the couples’ monthly income. The share of paid working hours is 10–15 percentage points higher for wives from countries with a higher FMR-LFP and is 21 percentage points higher for native-born wives. Similarly, the share of income increased with the source country’s FMR-LFP and for natives. In turn, these wives spent with 71–79 percent less time on housework.

The impact of wives’ earnings on their allocation of housework time

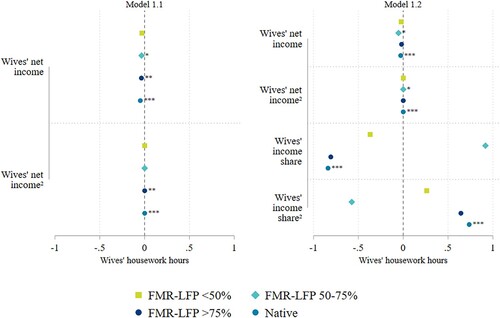

displays the estimation results for the effect of wives’ financial resources on their absolute housework. The full results are reported in Table S2a and S2b in the Supporting Information. Whereas Table S2a contains Model 1.1 and Model 1.2, Table S2b contains the results of two specifications estimating as robustness checks the effects of absolute (Model 1.3) or relative income (Model 1.4) in linear splines.

Figure 2. Fixed effects regression of wives’ housework time on their absolute and relative resources. The full results are reported in Supporting Information Table S2. Note: Significance level: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

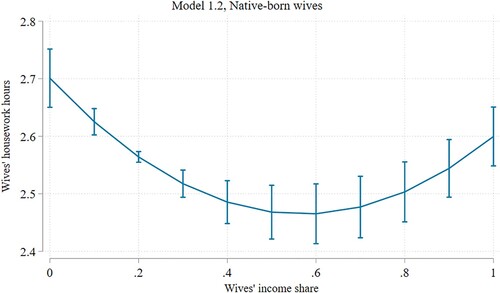

Whereas Model 1.1 considers only the absolute log net income (squared), resulting in significant but very low effects on housework time for all four groups, Model 1.2 additionally considers relative income, measured as the share of the couples’ total income from labor (including both a linear and a quadratic term). Showing higher significant effects of relative income, we infer that Model 1.2 best describes the relationship between wives’ financial resources and housework time. Relative income showed, however, only a significant effect for native-born wives. The nonlinear relationship is visualised in , showing that native-born wives decreased their housework hours with their relative income with a decreasing slope until the income share equaled 60 percent of couples’ income. When wives’ income shares increased, for example, from approximately 20–30 percent of couples’ income, their housework hours per average working day decreased from approximately 2.55–2.51 hours. The wives whose earnings exceeded 60 percent of the couples’ total income from labor increased their housework time, as suggested by the gender perspective.

Figure 3. Prediction of the nonlinear marginal effect of relative income on native-born wives’ housework time (average marginal effects were insignificant for immigrant wives).

Killewald and Gough (Citation2010) showed that the consideration of wives’ absolute earnings differentiated in separate parts of the income distribution revealed a spurious nonlinear relationship between relative income and housework hours. Model 1.3 (displayed in Table S2b) replaced absolute income with linear splines to analyze the effect separately for the 1–49th percentile, 50–89th percentile and 90th-99th percentile. Coefficients of relative income in this case hardly changed. Additionally, when measuring the relative income in linear splines, estimated effects suggested that the effect of relative income was only significant for native-born wives and that a higher negative effect resulted for those earning less relative to the husband than those earning more relative to their husbands.

Note that we controlled for wives’ and husbands’ time availability in terms of working hours to clarify the effect on bargaining power from one of the time constraints. In all models, wives’ working hours negatively affected their housework hours. In turn, significant coefficients of husbands’ working hours were positive but less important predictors (see Table S2a and S2b in the Supporting Information).

To elaborate on these findings in light of our hypotheses, we find that among native-born wives, the effect of income on housework time followed the relative resources perspective (H1); however, only up to the point the wives earned 60 percent of the couple’s total income from labor. For those who earned more than 60 percent, the gender perspective also applied (H2). In turn, immigrant wives’ housework hours did not significantly differ by income. This inelastic housework time followed the gender perspective (H2). Other than economic factors – as suggested by the relative resources (H1) or autonomy perspective (H3) – cultural factors appear to determine immigrant couples’ division in housework time. We turn to this issue in the final section.

The impact of wives’ earnings on husbands’ allocation of housework time

replicates the same models of the effects of wives’ financial resources presented in on husbands’ housework time. The full results are shown in Table S3a and S3b in the Supporting Information.

Figure 4. Fixed effects regression of husbands’ housework time on wives’ absolute and relative resources. The full results are reported in Supporting Information Table S3. Note: Significance level: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

As shown in , wives’ absolute income did not or only marginally affected husbands’ housework time (see Model 2.1), whereas relative income had a low significant positive effect on housework time for immigrant couples with an FMR-LFP below 50% or above 75% as for native-born couples (see Model 2.2). Comparable to the models on wives’ housework time, we therefore assume that Model 2.2 best describes the relationship between wives’ financial resources and husbands’ housework time. When wives’ income share increased by one percent, their husbands increased housework by 0.3–0.4 hours per working day.

The relationship of absolute as relative income was strongly linear for immigrant wives’ husbands; therefore, we excluded – in contrast to Model 1.1–1.4 – the squared term of the income variables for all four groups. The results only marginally changed when differentiating between wives of different parts of the absolute or relative income distribution (see Models 2.3 and 2.4 in Table S3b in the Supporting Information). The ladder additional Model 2.4 showed especially significant effects of husbands’ housework time for immigrant and native-born wives who earned (almost) the full household income.

Turning to our hypotheses, in contrast to immigrant wives’ own housework, we found husbands of immigrant wives (except those with an FMR-LFP between 50% and 75%) similar to husbands of native-born wives to spend more time on housework the higher their wives’ income share was, a behavior described by the relative resources (H1) rather than by the gender (H2) or autonomy perspective (H3).

The impact of wives’ labor market entry on couples’ allocation of housework time

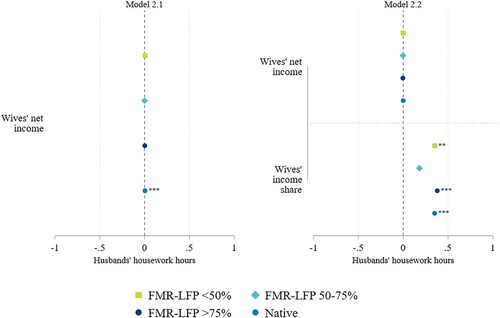

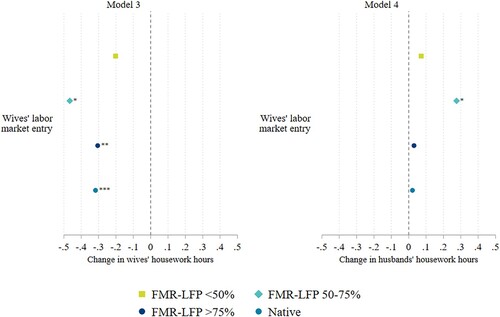

depicts the results from the analyses of the effect of wives’ labor market entry on their own (Model 3) or on their husbands’ housework hours (Model 4).

Figure 5. Fixed effects regression of wives’/husbands’ housework time on wives’ labor market entry. The full results are reported in Supporting Information Table S4. Note: Significance level: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

For immigrant wives who come from countries with an FMR-LFP above 49 percent, as for native-born wives, their labor market entry was associated with a reduction in time spent on housework by approximately 0.3–0.4 hours per average working day. For wives who came from countries with an FMR-LFP below 50 percent, the effect was insignificant (Model 3). Because we also controlled for the log change in wives’ and husbands’ working hours and whether the husband was employed, this effect did not indicate a pure change in time availability but rather a change in wives’ bargaining power due to changes in their employment and earning situations (for the full results see Tables S4 in the Supporting Information). In contrast, only for immigrant wives from countries with an FMR-LFP between 50 and 75 percent did their labor market entry shape husbands’ housework time (Model 4).

The results of Model 3 provide for most groups evidence for the relative resources as well as for the autonomy perspective (H1 and H3) because the improved earning situation resulted in a reduction in wives’ housework time. The insignificant effect for the group of women from countries with an FMR-LFP below 50 percent alludes to the gender perspective (H2), assuming no effect of a change in economic resources on housework for wives from countries with a very traditional gender division of work. The same applies to Model 4, conforming to the gender perspective (H2) in terms of an inelastic response of husbands’ housework time due to wives increasing earnings, with the exception of wives from countries with an FMR-LFP between 50 and 75 percent. Here, as in Model 3, husbands’ behavior contradicts the gender perspective.

Robustness check

One can argue that the results are strongly influenced by breadwinner households or by a spouse who is not able or only with a reduced amount able to participate in paid work due to age or disability. However, when excluding those couples, the effects of income in Model 1.2 (which we assumed best represents the relationship between wives’ financial resources and their housework time) remained, in most cases, insignificant for immigrant wives. The nonlinear effect of relative income increased for the group of native-born wives among couples with both spouses being employed or with husbands being below the age of 65 and having no disability status (see Tables S6 in the Supporting Information).

As an additional robustness check showed, the effects of wives’ relative earnings on their time spent on childcare were higher for native-born wives, whereas they were still insignificant for immigrant wives (see Table S7 in the Supporting Information). Hence, compared to the routine housework tasks (cooking, washing and cleaning), childcare appears to be more elastic with respect to economic resources the spouses contribute to the household income, although mostly still among native-born couples. Emphasising the investment facet, former studies have shown that the trend for time spent on childcare contrasts with the trend for time spent on other housework tasks as earnings increase (Kimmel and Connelly Citation2007).

The effects of wives’ earnings on husbands’ time spent on the sum of cleaning, cooking, washing and doing garden/repair work were also similar to the effects of Model 2.2 (which we believed was the most suitable model) on husbands’ time spent only on cooking, washing and cleaning. In addition to the insignificant effect for the FMR-LFP group 50–75 percent, the effect was insignificant for the FMR-LFP group above 75 percent. (see Table S8 in the Supporting Information). One explanation for the significant effects of immigrant husbands’ housework time on their wives’ earnings is that husbands have more flexibility for adjustment due to their primary very low participation in housework. This seems to apply to a lesser extent for immigrant husbands from less tradition-oriented countries (with a high FMR-LFP) when additionally considering more male housework tasks.

While our descriptive and regression findings suggest that cultural factors approximated by the source country’s FMR-LFP may contribute to the uneven division of housework between immigrant and native-born couples, the question of how to explain these differences has not been conclusively answered. To gain insights into this question, we explored the contribution of compositional differences between native-born and immigrant wives to the difference in their housework time allocation using Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition (Blinder, Citation1973; Oaxaca, Citation1973). In addition to the control variables used in the former regression analysis, we considered wives’ educational attainment (aggregated into no professional degree, professional degree, and college degree) and a continuous measure of source country’s FMR-LFP. Our findings imply that compositional differences in endowments explained 80 percent of the gap (the ‘endowments effect’; refer to Online Supporting Information, Table S9). Zooming on the explained part of the gap, we found that the highest contribution was attributed to the differences in working hours (35 percent), followed by the differences in household size (28 percent), wives’ absolute income (11 percent), source country’s FMR-LFP (9 percent) and educational attainment (8 percent). In turn, 20 percent of the immigrant–native-born wives’ housework gap could not be explained. This unexplained part may result from differences in the coefficients (i.e. different effects of the same endowments in both groups) or unobserved differences in important characteristics shaping immigrants’ economic and social integration (e.g. German language proficiency, transferability of foreign educational degrees) – these factors cannot be compared between immigrant and native-born wives in our analyses.

Discussion

The labor market participation of female immigrants is vital for immigrants’ economic and societal integration process. Following the relative resource perspective, the division of paid work among couples may also influence the division of their unpaid housework. Accordingly, unpaid labor activities might shape the labor market integration of female immigrants (e.g. Zaiceva and Zimmermann Citation2014) and could be particularly relevant among couples with a more traditional value orientation (e.g. Bielby and Bielby Citation1992). The highly uneven division of time spent on housework duties observed among immigrant couples, which may indicate a more traditional value orientation than among native-born couples, was expected to hinder the labor market integration of female immigrants in Western economies. We took on this perspective and examined the relationship between wives’ economic dependency and the allocation of couples’ housework time as well as variation in this relationship across immigrant and native-born wives using data from the German SOEP for the years 1995–2019 and two integrated studies, the IAB-SOEP Migration Sample and the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees, and fixed-effect models.

We relied on three prominent theories – relative resources, doing gender and autonomy – aimed at explaining the relationship between labor market performance and housework time. Numerous studies have empirically tested these theoretical mechanisms (e.g. Bianchi et al. Citation2000; Gupta Citation2007; Hook Citation2017; Killewald and Gough Citation2010), whereas empirical evidence for immigrants is scarce. The relative resources and autonomy perspective are formally neutral regarding gender and migration status and imply no differences between immigrants and native-born individuals. In turn, we hypothesize that the gender perspective applies more to immigrant than to native-born couples. Descriptively, we show that unpaid and paid working time is distributed more unequally the lower the wives’ home country FMR-LFP is. Our multivariate findings from the models on wives’ labor market entry further revealed a significant effect on housework only for immigrant wives whose FMR-LFP is larger than 50 percent. However, the effects of income on housework were insignificant for all immigrant wives. Since many countries had a similar FMR-LFP in the observation period as in Germany (The World Bank Citation2021), the insignificant effects of income on housework for immigrant wives cannot fully be explained by more traditional values approximated by the source country’s female labor force participation.

Among native-born wives, increasing housework time with increasing relative income – a behavior possibly determined by traditional gender values – was observed only if they earned more than 60 percent of the couples’ total income. Furthermore, the high gender differences in housework time gave immigrant husbands flexibility to respond to their wives’ labor market integration, as proposed by the relative resources perspective. However, as shown in a robustness check, these responses were predominantly observed for husbands who earned less than their wives. In sum, our results imply that the standard theoretical models predict immigrant wives’ housework time in a way that a similar process applies to immigrant wives as to native-born wives, although at different levels.

To this end, migration literature focusing on labor market gender differences attempts to explain immigrant women’s double disadvantage, i.e. the labor market disadvantages attributed to gender and immigrant status. Our analyses contribute to this debate by showing that the wife’s relative earnings influence her own housework time only among native couples, whereas the immigrant wife’s housework time does not vary by her relative earnings. In other words, unlike native women, immigrant women are not able to leverage their improved relative economic situation by reducing their relative contribution to household work. Measured with the source countries’ female labor force participation, we cannot explain differences between immigrant and native-born wives purely by cultural factors: The inelastic housework response applies in most models to immigrant wives independent of their source country female labor force participation.

The integration challenges of both immigrant wives and their husbands are likely to be an additional reason for the inelastic response of immigrant wives. Using decomposition analyses, we shed light on possible explanations for the immigrant–native-born differences in couples’ housework division. Our results indicate that the difference in housework hours between immigrant and native-born wives can mainly be explained by immigrant wives’ fewer hours of paid work, larger household sizes and lower bargaining power due to a lower labor income of immigrant wives but also from a lower FMR-LFP in the source country. Differences in the type of jobs immigrant and native men and women have access to could provide an explanation for these patterns. Immigrants’ occupational opportunities are often restricted to secondary labor market segments and labor-intensive sectors (Gundert, Kosyakova, and Fendel Citation2020; Kogan Citation2011; Wilson and Portes Citation1980). Such jobs are usually worse paid, belong to the lower part of the occupational hierarchy, are stressful and are characterised by poor working conditions. At the same time, women, mothers in particular, more often select jobs promising a better reconciliation of family and work (e.g. more flexibility and shorter working hours arrangements) and a less stressful job environment (Hakim Citation2006; Polachek Citation1981). Accordingly, immigrant women who manage to enter such jobs and independent of the income relative to that of their husbands might be more willing to take over housework tasks, and this is more so when the husband’s jobs are very stressful and tiring. Nevertheless, since immigrant women are more likely to end up on lower levels of occupational hierarchies than native women, the double burden of market and nonmarket work coupled with lower incomes may reinforce integration barriers of female immigrants and their social exclusion.

Several limitations of our research are important to mention. First, when analyzing the labor market entry of immigrant wives, we looked at adjustments in the year that labor market entry occurred. One important remaining question is how the adjustments have developed over time. Gershuny et al. (Citation2005) showed that women greatly adjust their housework time immediately after entering full-time paid work, whereas men showed increases only in successive years. Second, further differentiation across origin countries could provide insight into the determinants of the division of housework among immigrant couples. To control for time-invariant source country groups or their characteristics is, however, not possible within the fixed effects estimations we applied. Our method, which washed out all gender- and couple-specific time-invariant factors, was the best way to control for unobserved factors shaping the allocation of market and nonmarket work (such as motivations, productivity or preferences). Third, fixed effects estimation methods alleviate any estimation bias due to time-constant heterogeneity in reports on housework hours due to over- or underreporting (see Gough and Killewald Citation2011; Voßemer and Heyne Citation2019). Although previous studies found that estimates based on time-use data are similar in sign and statistical significance to those of diary data (Kan and Pudney Citation2008), many studies have noted that time-use data are less accurate than diary methods. Therefore, the integration of time-diary data in large panel datasets could improve the quality of future research on this topic.

Our findings are important from a policy perspective. The multivariate results revealed that – in contrast to native-born wives – immigrant wives do not adjust their housework time as their earnings change. The immigrant wives’ inelastic response was in most models observed to be independent of the source country female labor force participation, which may primarily result from integration challenges the couples face. This inelasticity in housework time seems to drive the observed unequal division of housework among immigrant couples and may reinforce the economic and social integration barriers of female immigrants. From this perspective, policy interventions aiming to improve immigrant women’s structural integration could ensure a better comparability of work and family, for example, via the supply of accessible, affordable and quality external services.

Availability of data and material

The data from the German Socio-Economic Panel and two integrated studies, the IAB-SOEP Migration Sample and the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees, used in this study are part of an anonymized dataset; the data user is not able to trace information back to individual participants. The personal data are processed in such a way that the rights of the subjects to the confidentiality and integrity of their data are not affected. Nevertheless, due to data security obligations, we are not permitted to publish the data underlying the study. Researchers can however apply for data access via the FDZ of the IAB or SOEP-FDZ at DIW. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to https://fdz.iab.de/en/FDZ_Individual_Data.aspx. The computer code for data preparation and analyses and the Supporting Information are available at https://osf.io/t5sgb/.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (85 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Statham and other editors of the Journal for Ethinc and Migration Studies and two referees for helpful and constructive comments. We further thank Silvia Salazar and Maye Ehab for providing helpful advice on earlier versions of this paper and all those who commented on the earlier presentations of this work at the following events: the Australian Gender Economics Workshop, the Workshop on Labour Economics of the Institute for Labour Law and Industrial Relations in the European Union at the University Trier, the Meeting of the Gender Working Group of the Institute for Employment Research, the Women on the Move – Current Perspectives on Female Migration Workshop of the German Institute for Economic Research and the Academy of Sociology, the yearly meeting of the Verein für Socialpolitik and the Conference of the European Sociological Association. This study design and analysis were not preregistered.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The literature on the domestic division of labor reveals that wives usually perform the majority of the housework (Bianchi et al. Citation2000).

2 To test the selectivity of our sample due to having missing information on housework hours, we regressed the probability of having missing information on the explanatory variables relying on random effect models. Our findings imply that having missing information on housework hours of wives or husbands is negatively related to wives’ higher income share, ALGI benefits receipt, arriving from a country with greater female–male employment ratio, and to partner’s employment. It is positively related to own health and partners’ working hours. Factors such as wives’ or partners’ age, wives’ or partners’ education, wives’ employment and working hours, household size, age of youngest child in household, size of housing, and use of domestic service are not significantly related to the sample selection. In sum, considering that only six percent of the wives in the sample have missing information on housework hours, our findings indicate only a slightly positive selection into the sample based on observables.

3 Note that considering only coupled women does not lead to an uneven selection by migration background. In the SOEP 1995–2019, among women aged 20–64 years, the share of women living with a partner observed in the data are 67–69 percent among immigrant and native-born wives.

4 There is no data available for Kosovo before 2002. Between 2002 and 2018, the FMR-LFP varied between 29–47 percent (see The World Bank Citation2021). Hence, for immigrant wives from Kosovo first surveyed before 2002, we considered 2002 values.

5 In a robustness check, we tested results of the model, which we assumed best represents the relationship between wives’ financial resources and her housework time, using three alternative group compositions of immigrant wives: First, we used the Gender inequality index in 2019 from Human Development (UNDP). Considering the three dimensions, reproductive health, empowerment and the labor market, the index is therefore a broader measure of gender equality than the FMR-LFP. Second, we differentiated wives geographically from Non-Western versus Western countries with the Western country group including all EU countries, other high-income countries and countries from the former Soviet Union and former Yugoslavia and all other countries belonging to the Non-Western group. A third differentiation was based on immigrant wives’ migration intention (economic migrant, family migrant or refugee). Other aspects of gender equality, the geographical differentiation as well as the migration intention may influence the division of housework between a couple, however, the results hardly differed to those presented in the main results section. For details, refer to Online Supporting Information, Table S5.

6 In robustness checks we estimated effects of income divided in linear splines. Following Hook (Citation2017), we differentiated between wives belonging to the 1st-49th, 50th-89th or 90th-99th percentile of all women’s absolute income. Furthermore, we differentiated between wives with a relative income-share of 1–49 percent, 50–89 percent and 90–100 percent; for instance, breadwinners earn 90–100 percent of the couple’s income. For details, refer to Online Supporting Information, Table S2 Model 1.3 and Model 1.4 and Table S3 Model 2.3 and Model 2.4.

References

- Becker, Gary S. 1985. “Human Capital, Effort, and the Sexual Division of Labor.” Journal of Labor Economics 3 (1): S33–S58. doi:10.1086/298075.

- Bianchi, Suzanne M., Melissa A. Milkie, Liana C. Sayer, and John P. Robinson. 2000. “Is Anyone Doing the Housework? Trends in the Gender Division of Household Labor.” Social Forces 79 (1): 191–228. doi:10.2307/2675569.

- Bielby, William T., and Denise D. Bielby. 1992. “I Will Follow Him: Family Ties, Gender-Role Beliefs, and Reluctance to Relocate for a Better Job.” American Journal of Sociology 97 (5): 1241–1267. doi:10.1086/229901.

- Bittman, Michael, Paula England, Liana Sayer, Nancy Folbre, and George Matheson. 2003. “When Does Gender Trump Money? Bargaining and Time in Household Work.” American Journal of Sociology 109 (1): 186–214. doi:10.1086/378341.

- Blau, Francine D., Lawrence M. Kahn, Matthew Comey, Amanda Eng, Pamela Meyerhofer, and Alexander Willén. 2020. “Culture and Gender Allocation of Tasks: Source Country Characteristics and the Division of non-Market Work among US Immigrants.” Review of Economics of the Household 18 (4): 907–958. doi:10.1007/s11150-020-09501-2.

- Blinder, Alan S. 1973. “Wage Discrimination: Reduced Form and Structural Estimates.” The Journal of Human Resources 8 (4): 436. doi:10.2307/144855.

- Brines, Julie. 1994. “Economic Dependency, Gender, and the Division of Labor at Home.” American Journal of Sociology 100 (3): 652–688. doi:10.1086/230577.

- Browne, Irene, and Joya Misra. 2003. “The Intersection of Gender and Race in the Labor Market.” Annual Review of Sociology 29 (1997): 487–513. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100016.

- Brücker, Herbert, Martin Kroh, Simone Bartsch, Jan Goebel, Simon Kühne, Elisabeth Liebau, Parvati Trübswetter, Ingrid Tucci, and Jürgen Schupp. 2014. The New IAB-SOEP Migration Sample: An Introduction Into the Methodology and the Contents.” SOEP Survey Papers 216: Series C. Berlin: DIW/SOEP.

- Brücker, Herbert, Nina Rother, and Jürgen Schupp. 2017. IAB-BAMF-SOEP-Befragung von Gefluechteten 2016: Studiendesign, Feldergebnisse Sowie Analysen Zu Schulischer Wie Beruflicher Qualifikation, Sprachkenntnissen Sowie Kognitiven Potenzialen. IAB-Forschungsbericht, 13/2017. Berlin: DIW/SOEP.

- Buuren, Stef van. 2012. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

- Cooke, Thomas J., Paul Boyle, Kenneth Couch, and Peteke Feijten. 2009. “A Longitudinal Analysis of Family Migration and the Gender Gap in Earnings in the United States and Great Britain.” Demography 46 (1): 147–167. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0036.

- Donato, Katharine M., Bhumika Piya, and Anna Jacobs. 2014. “The Double Disadvantage Reconsidered: Gender, Immigration, Marital Status, and Global Labor Force Participation in the 21st Century.” International Migration Review 48 (s1): 335–376. doi:10.1111/imre.12142.

- Evertsson, Marie, and Magnus Nermo. 2004. “Dependence Within Families and the Division of Labor: Comparing Sweden and the United States.” Journal of Marriage and Family 66 (5): 1272–1286. doi:10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00092.x.

- Fortin, Nicole M. 2005. “Gender Role Attitudes and the Labour-Market Outcomes of Women Across OECD Countries.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 21 (3): 416–438. doi:10.1093/oxrep/gri024.

- Foster, Gigi, and Leslie S. Stratton. 2018. “Do Significant Labor Market Events Change Who Does the Chores? Paid Work, Housework, and Power in Mixed-Gender Australian Households.” Journal of Population Economics 31 (2): 483–519. doi:10.1007/s00148-017-0667-7.

- Frank, Kristyn, and Feng Hou. 2015. “Source-Country Gender Roles and the Division of Labor Within Immigrant Families.” Journal of Marriage and Family 77 (2): 557–574. doi:10.1111/jomf.12171.

- Fuwa, Makiko. 2004. “Macro-Level Gender Inequality and the Division of Household Labor in 22 Countries.” American Sociological Review 69 (6): 751–767. doi:10.1177/000312240406900601.

- Geißler, R. 2014. Die Sozialstruktur Deutschlands. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Gershuny, Jonathan, Michael Bittman, and John Brice. 2005. “Exit, Voice, and Suffering: Do Couples Adapt to Changing Employment Patterns?” Journal of Marriage and Family 67 (3): 656–665. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00160.x.

- Gough, Margaret, and Alexandra Killewald. 2011. “Unemployment in Families: The Case of Housework.” Journal of Marriage and Family 73 (5): 1085–1100. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00867.x.

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469.

- Greenstein, Theodore N. 2000. “Economic Dependence, Gender, and the Division of Labor in the Home: A Replication and Extension.” Journal of Marriage and Family 62 (2): 322–335. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00322.x.

- Grönlund, Anne, and Malcolm Fairbrother. 2022. “No Escape from Tradition? Source Country Culture and Gendered Employment Patterns among Immigrants in Sweden.” International Journal of Sociology 52 (0): 49–77. doi:10.1080/00207659.2021.1978192.

- Gundert, Stefanie, Yuliya Kosyakova, and Tanja Fendel. 2020. “Migrantinnen Und Migranten Am Deutschen Arbeitsmarkt: Qualität Der Arbeitsplätze Als Wichtiger Gradmesser Einer Gelungenen Integration.” IAB Kurzbericht 25/2020.

- Gupta, Sanjiv. 2007. “Autonomy, Dependence, or Display? The Relationship Between Married Women?s Earnings and Housework.” Journal of Marriage and Family 69 (2): 399–417. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00373.x.

- Haddad, T., and L. Lam. 1994. “The Impact of Migration on the Sexual Division of Family Work: A Case Study of Italian Immigrant Couples.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 25 (2): 167–182. doi:10.3138/jcfs.25.2.167.

- Hakim, Catherine. 2006. “Women, Careers, and Work-Life Preferences.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 34 (3): 279–294. doi:10.1080/03069880600769118.

- Hayfron, John E. 2002. “Panel Estimates of the Earnings Gap in Norway: Do Female Immigrants Experience a Double Earnings Penalty?” Applied Economics 34 (11): 1441–1452. doi:10.1080/00036840110101429.

- Hochschild, Arlie, and Anne Machung. 1989. Working Parents and the Revolution at Home. New York: Viking.

- Hook, Jennifer L. 2017. “Women’s Housework: New Tests of Time and Money.” Journal of Marriage and Family 79 (1): 179–198. doi:10.1111/jomf.12351.

- Kalmijn, Matthijs, and Gerbert Kraaykamp. 2018. “Determinants of Cultural Assimilation in the Second Generation. A Longitudinal Analysis of Values About Marriage and Sexuality among Moroccan and Turkish Migrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (5): 697–717. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1363644.

- Kan, Man Yee, and Stephen Pudney. 2008. “2. Measurement Error in Stylized and Diary Data on Time Use.” Sociological Methodology 38 (1): 101–132. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9531.2008.00197.x.

- Kan, Man Yee, Oriel Sullivan, and Jonathan Gershuny. 2011. “Gender Convergence in Domestic Work: Discerning the Effects of Interactional and Institutional Barriers from Large-Scale Data.” Sociology 45 (2): 234–251. doi:10.1177/0038038510394014.

- Khattab, Nabil, Ron Johnston, and David Manley. 2018. “Human Capital, Family Structure and Religiosity Shaping British Muslim Women’s Labour Market Participation.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (9): 1541–1559. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1334541.

- Killewald, Alexandra, and Margaret Gough. 2010. “Money Isn’t Everything: Wives’ Earnings and Housework Time.” Social Science Research 39 (6): 987–1003. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.08.005.

- Kimmel, Jean, and Rachel Connelly. 2007. “Mothers’ Time Choices.” Journal of Human Resources XLII (3): 643–681. doi:10.3368/jhr.XLII.3.643.

- Kogan, Irena. 2011. “The Price of Being an Outsider: Labour Market Flexibility and Immigrants’ Employment Paths in Germany.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 52 (4): 264–283. doi:10.1177/0020715211412113.

- Kühhirt, Michael. 2012. “Childbirth and the Long-Term Division of Labour Within Couples: How Do Substitution, Bargaining Power, and Norms Affect Parents’ Time Allocation in West Germany?” European Sociological Review 28 (5): 565–582. doi:10.1093/esr/jcr026.

- Mandel, Hadas, Amit Lazarus, and Maayan Shaby. 2021. “Economic Exchange or Gender Identities? Housework Division and Wives’ Economic Dependency in Different Contexts.” European Sociological Review 36 (6): 831–851. doi:10.1093/esr/jcaa023.

- Mincer, Jacob. 1978. “Family Migration Decisions.” Journal of Political Economy 86 (5): 749–773. doi:10.1086/260710.

- Müller, Kai-Uwe, and Katharina Wrohlich. 2016. “Two Steps Forward—One Step Back? Evaluating Contradicting Child Care Policies in Germany.” CESifo Economic Studies 62 (4): 672–698. doi:10.1093/cesifo/ifv020.

- Ng, R., and J. Ramirez. 1981. Immigrant Housewives in Canada. Toronto: Booklet.

- Oaxaca, Ronald. 1973. “Male-Female Wage Differentials in Urban Labor Markets.” International Economic Review 14 (3): 693. doi:10.2307/2525981.

- OECD. 2019. International Migration Outlook 2019. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Polachek, Solomon William. 1981. “Occupational Self-Selection: A Human Capital Approach to Sex Differences in Occupational Structure.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 63 (1): 60–69. doi:10.2307/1924218.

- Ribar, David C. 2013. “Immigrants’ Time Use: A Survey of Methods and Evidence.” In International Handbook on the Economics of Migration, 373–392. City: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Rubin, Donald B. 1987. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley.

- Shauman, Kimberlee A., and Mary C. Noonan. 2007. “Family Migration and Labor Force Outcomes: Sex Differences in Occupational Context.” Social Forces 85 (4): 1735–1764. doi:10.1353/sof.2007.0079.

- Shelton, Beth Anne, and Daphne John. 1996. “The Division of Household Labor.” Annual Review of Sociology 22 (1): 299–322. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.299.

- SOEP Group. 2021. “Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), Data for Years 1984-2019, SOEP-Core V36, EU Edition, 2021.” doi:10.5684/soep.core.v36eu

- Sprengholz, Maximilian, Claudia Diehl, Johannes Giesecke, and Michaela Kreyenfeld. 2021. “From "Guest Workers" to EU Migrants: A Gendered View on the Labour Market Integration of Different Arrival Cohorts in Germany.” Journal of Family Research 33 (2): 252–283. doi:10.20377/jfr-492.

- Stewart, Jay. 2013. “Tobit or Not Tobit?” Journal of Economic and Social Measurement 38 (3): 263–290. doi:10.3233/JEM-130376.

- Sullivan, Oriel. 2013. “What Do We Learn About Gender by Analyzing Housework Separately from Child Care? Some Considerations from Time-Use Evidence.” Journal of Family Theory & Review 5 (2): 72–84. doi:10.1111/jftr.12007.

- Voßemer, Jonas, and Stefanie Heyne. 2019. “Unemployment and Housework in Couples: Task-Specific Differences and Dynamics Over Time.” Journal of Marriage and Family 81 (5): 1074–1090. doi:10.1111/jomf.12602.

- West, Candace, and Don H. Zimmerman. 1987. “Doing Gender.” Gender & Society 1 (2): 125–151. doi:10.1177/0891243287001002002.

- Wilson, Kenneth L., and Alejandro Portes. 1980. “Immigrant Enclaves: An Analysis of the Labor Market Experiences of Cubans in Miami.” American Journal of Sociology 86 (2): 295–319. doi:10.1086/227240.

- The World Bank. 2021. “Ratio of Female to Male Labor Force Participation Rate (%) (National Estimate).” World Development Indicators. 2021. https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=SL.TLF.CACT.FM.NE.ZS&country=.

- Zaiceva, Anzelika, and Klaus F. Zimmermann. 2014. “Children, Kitchen, Church: Does Ethnicity Matter?” Review of Economics of the Household 12 (1): 83–103. doi:10.1007/s11150-013-9178-9.