ABSTRACT

For asylum route refugees, the existence and persistence of structural barriers to navigating statutory systems are well-documented. Even when initial barriers are overcome, further transitions may disrupt refugees’ lives. One such is the arrival in the UK of family members from whom they had been separated during their flight from persecution. This paper draws upon data gathered using a Social Connections Mapping Tool methodology with reunited refugee families to make three contributions to the field of refugee studies. Firstly, families’ accounts of navigating statutory systems confirm the multi-directionality of integration. Refugees’ efforts to build and leverage social links proceed differentially across key statutory domains and cannot alone overcome systems barriers that require adaptation on the part of public services. Secondly, our findings contribute to scholarship that critiques the division of social relationships into categories of bonds, bridges and links, and the distinctions made between these based on ethnicity or nationality. Rather, refugees’ social relationships are more appropriately understood as a fluid continuum, with their nature and purpose subject to change. Finally, refugee families’ descriptions of settling in the UK highlight the influence of time on integration and the importance to refugees of re-building independence in a new country context.

Introduction

Immigration and asylum is a highly contested social policy arena. Since the 1990s, there has been a drive towards increasingly restrictive policies across Europe and the Global North that aim to limit the numbers of people who can exercise their right to seek asylum in those territories (Zetter Citation2015; Mountz Citation2020). In the UK this has taken shape as an officially sanctioned ‘hostile environment’ for certain migrants. Hostile measures include: a private-sector led immigration detention estate with no time limit on the deprivation of liberty; excluding people seeking asylum from mainstream welfare systems; and the use of destitution as a policy tool (Mayblin, Wake, and Kazemi Citation2020).

Within this context, refugee integration is one migration-related policy realm where governments have been willing to invest resources. Significant energy has been expended to understand and support integration in high-income contexts, with increasing recognition of its multi-dimensional, multi-directional nature (Ndofor-Tah et al. Citation2019). However, while the concept of integration has been adopted not only by academics but by policy makers and service providers (Phillimore Citation2021), it is subject to fluid and sometimes conflicting interpretations (Spencer and Charlsey Citation2021). The linkage between diminished societal integration and the arrival of new migrants (especially those from the Global South) dominant in policy discourse, assumes that receiving communities are themselves integrated and culturally and economically cohesive. This ignores intersectional (dis)advantage rooted not in ethnicity or nationality but in, amongst other factors, social class, economic prosperity and gender (Schinkel Citation2013). While some researchers have, as a result, called for the concept itself to be set aside as part of a wider effort to de-colonise migration studies (Schinkel Citation2013), others have sought to retain and rehabilitate the concept. This has included efforts to clearly delineate integration as a process rather than a series of pre-determined outcomes (Penninx Citation2019), which takes place differentially, over time and across inter-linked dimensions (Spencer and Charlsey Citation2021). This paper adopts the latter approach to integration, with a focus on an under-explored transition point in refugees’ lives – family reunion. Refugees’ explanations of how they build and leverage social relationships to overcome barriers imposed by statutory systems exemplifies the interplay between the social and structural dimensions identified by Spencer and Charsley. We begin by outlining relevant elements of these dimensions, before presenting thematic findings that expand our knowledge of the experiences of refugee families after the point of reunion.

Social context

A processual understanding of integration encompasses economic, spatial and, most importantly for this paper, social elements (Kearns and Whitley Citation2015; Bloch Citation2008; Spicer Citation2008; Ager and Strang Citation2008). At an individual level, integration can be positioned as a relational process whereby people mix with others, bringing their distinct social identities and histories to the relationship (Berry Citation1997). The resulting relationships play multiple roles in individuals’ lives. These can be primarily transactional, in that the connections facilitate the exchange of material or informational resources or lead towards tangible outcomes such as paid employment (Ager and Strang Citation2008). Emotionally, positive connections with others can contribute to people’s sense of belonging in a new country context (Wessendorf and Phillimore Citation2019), while being unable to build new connections can lead to feelings of loneliness and isolation (Strang and Quinn Citation2021).

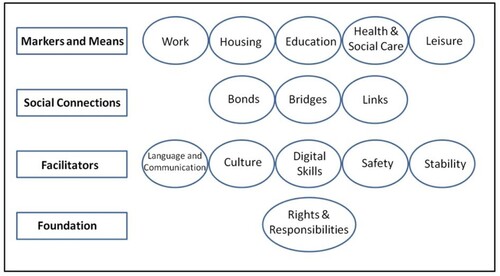

At the outset of the project, the research team aimed to explore the role of social connections in refugee integration, using the Indicators of Integration as the underpinning conceptual framework (Ndofor-Tah et al. Citation2019). The framework is explicitly normative, having initially been developed to provide a set of measurable indicators against which service providers, policy makers and individuals could assess and understand the complex processes at work in integration (Ager and Strang Citation2008). However, its influence on research, particularly that conducted in applied contexts such as the practice-research engagement discussed in this paper (Brown et al. Citation2003), is undeniable. Our work then sits ineluctably within the social connections layer of the framework, which, we suggest, positions us ideally to develop and critique its content. This layer, and indeed the original framework, was developed based on data collected with refugees and longer-term residents in two UK cities. Both groups agreed that building relationships was crucial to the integration process (Ager and Strang Citation2008). This resulted in three social connections domains that sit at the centre of the original, and more recent iteration, of the Indicators of Integration framework, shown in . These group social connections by type according to their form: the characteristics of who is connecting; and function: what resources flow through them. This elision between form and function will be explored later in the paper.

Figure 1. Indicators of Integration Framework (Ndofor-Tah et al. Citation2019, 15).

Bridging connections

Strang and Ager (Citation2010; see also Ager and Strang Citation2008), Spencer and Charsley (Citation2016) and the most recent iteration of the Indicators of Integration Framework (Ndofor-Tah et al. Citation2019) all place significant importance on social bridges. Drawing on the work of Granovetter (Citation1973, Citation1983) and Putnam (Citation2000), social bridges are relationships with actors outside of our own social circles or, in other words, with people different to us. Whilst typically understood to be weaker than social bonds in terms of levels of trust, bridging ties between those who occupy different social spaces can facilitate the flow of information and other resources through diverse social groups, leading for example to greater job opportunities for each of the groups (Granovetter Citation1973, Citation1983). In the context of migration, positive social encounters between different groups are also seen as crucial in terms of avoiding social segregation between people of different ethnicities or nationalities (Allport Citation1954) and enabling new residents to feel that they belong in local areas (Spicer Citation2008; Strang and Quinn Citation2021).

Bonding connections

If the notion of social bridges stems from an approach in which difference is valued, similarity is one of the distinguishing features of social bonds. Coleman’s (Citation1988) and Putnam’s (Citation2000) work defines social bonds as relationships with those in whom we trust, often because they are similar to us. These relationships can provide a social, emotional and material safety net for the members of tightly bonded social networks. Indeed, people living in conditions of relative socioeconomic disadvantage may have to rely on strong ties of friendship and kinship for material, informational or emotional resources as they lack connections to the state or to other social groups (Granovetter Citation1983). Refugees’ prioritisation of reunification with their families (Connell et al. Citation2010; Scottish Refugee Council/Refugee Council/UNHCR Citation2018) and consequent discussions around their social isolation (Beswick Citation2015), speak to the difficulties that present themselves when forging new (bridging) relationships in the absence of existing trusting (bonding) relationships. Ryan’s (Citation2018) research on Polish migrants in London and Nunn et al.’s (Citation2016) engagement with young refugees in Australia demonstrate the important role trust and strong or bonding relationships play in creating a stable basis from which migrants feel able to build the bridging relationships with people from different social circles.

Linking connections

The Indicators of Integration Framework defines links as being ‘vertical relationships between people and the institutions of the society in which they live’ (Ndofor-Tah et al. Citation2019, 17; drawing from Szreter and Woolcock Citation2004). These ties may be of particular importance for economically and socially marginalised communities, for whom statutory services are their only access points to vital resources such as housing and financial support. As with other aspects of integration, links require both parties to be receptive to building a positive and productive relationship. This can present challenges to local and national government agencies charged with ensuring that public services are able to accommodate the needs of more diverse societies (Benton, McCarthy, and Collett Citation2015). Refugees themselves may actively seek to free themselves from certain linking connections in order to regain independence after the enforced dependency of the asylum process (Strang, Baillot, and Mignard Citation2018).

Between form and function?

In the context of international migration, and in application of the framework itself, there has been a tendency to conflate the form and function of these social relationships. There can be an assumption that bonding and bridging ties are primarily differentiated by the identity of the person or organisation with whom refugees are connecting. Within this restrictive gaze, social bonds have been differentiated from bridges simply on the basis of ethnicity or national origin, rather than more empirical measures such as the frequency and reciprocity of the relationship or measures of its function – whether it connects people to social or material resources. The assumption is that bridging ties are more valuable because they connect new migrants to longer-term residents who can enable new refugees to get ahead (Woolcock Citation1998). They are also assumed to improve social cohesion in the face of increasing ethnic and religious diversity (Demireva Citation2019; Casey Citation2016).

This ranking of importance, and indeed the distinctions made between the three types of connection are increasingly contested. Wessendorf and Phillimore’s (Citation2019) exploration of the social relations that underpin new migrants’ settlement challenges the assumption that it is only relationships forged with members of an imagined majority white local community that facilitate the flow of bridging social capital. Their analysis of social relations in superdiverse localities instead confirms that new residents, including refugees, are often settling into contexts where binary distinctions based on ethnicity are increasingly blurred, which in turn undermines assumptions about the relative value to social cohesion of certain types of social relationship (Wessendorf and Phillimore Citation2019). Similarly, Strang and Quinn’s (Citation2021, 1) work with single refugee men living in Glasgow questions the ‘binary distinction’ made by scholars such as Putnam between bonding and bridging relationships, arguing that this ignores the more fluid realities of many of the social relationships refugees recount as being important to them. Moreover, people’s access to the social capital, or resources, generated by connections can be unequal and determined by factors such as gender, social class or ethnic group or affiliation (Anthias Citation2007). Recognition of the heterogeneity of refugee communities, and of the local communities where they have settled, is therefore fundamental to any study of integration.

Structural dimensions: reunited refugee families

Phillimore calls for more attention to be paid to the opportunity structures that shape integration, a call that places the burden of integration across society rather than solely on the shoulders of refugees (Phillimore Citation2021). In this section we outline two of the opportunity structures that influence integration at the point of the family reunion. The first is the immigration policy context around refugee family reunion; the second is the service provision available to sponsors and their family members after this occurs.

Refugees who seek asylum without their family members may well experience increased access to rights after being recognised as refugees and granted leave to remain by the UK Home Office. However, ongoing separation from close family members can leave them ‘paralysed’ in other areas of their lives (Scottish Refugee Council/Refugee Council/UNHCR Citation2018, 26; see also Connell et al. Citation2010; Refugee Council/Oxfam Citation2018). Bringing family members over and re-establishing family bonds is therefore a precursor for the sponsor’s continuing integration across other domains (Pittaway, Bartolomei, and Doney Citation2016). In contrast to other family migration routes, the refugee family reunion visa is free of charge, the sponsor does not need to prove they are able to financially support the family, and family members do not have to be proficient in English. However, significant barriers remain (Beswick Citation2015), including complex evidential requirements, logistical difficulties, and restrictions on legal aid (Gower and McGuinness Citation2020). As a result, family members overseas may experience further displacement, violence and isolation whilst separated from the sponsor, giving lie to the idea that family reunion constitutes a safe route to protection (British Red Cross Citation2020).

Even once these hurdles have been overcome, the moment of family reunion is not straightforward (Rousseau et al. Citation2004; Marsden and Harris Citation2015). When family members arrive, a refugee sponsor’s circumstances change from a single person to one with dependants. This has implications for welfare benefits and can result in the family experiencing destitution (Marsden and Harris Citation2015). Simultaneously, the arrival of dependants usually prompts a need to find a larger home. Families can initially find themselves in overcrowded accommodation and then wait for a considerable time before alternative accommodation becomes available. As during the transition from asylum support, these house moves can disrupt social networks, placing strain on the family unit (Beswick Citation2015), and interrupting children’s schooling (Bourgonje Citation2010, 39). The moment of family reunion then illustrates the interplay between structural constraints – navigating Home Office policy and statutory systems; and the social domain – practical and bureaucratic transitions impacting upon families’ abilities to re-form and re-build a family life together. This interplay underpins the remainder of the article.

Materials and methods

This paper reports on findings from a mixed methods study conducted from 2019–2020 with people who were accessing a family reunion integration service provided by two third sector organisations. The service provided support both to the sponsor refugee – the person who had first come, usually alone, to claim asylum; and their arriving spouse and any dependent children. The terms sponsor and spouse are used throughout the remainder of the paper to differentiate participants. The service was explicitly designed to deliver interventions across the domains of the Indicators of Integration framework (Ndofor-Tah et al. Citation2019). This included work to support families to re-build bonds between them, and to foster bridging connections with local communities (Baillot et al. Citation2021).

Workshops

The research team conducted eight workshops, one in each of eight cities across the UK. A total of 61 adult family members from 35 families, and from 10 different nationalities participated, as shown in .

Table 1. Workshop participants.

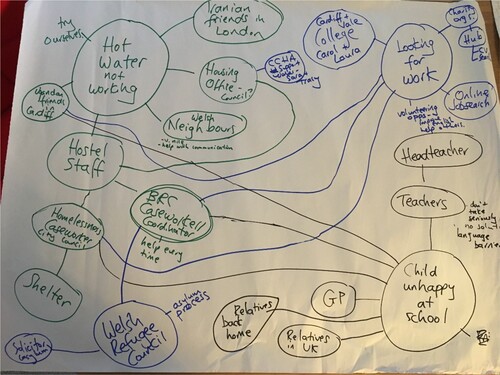

Using the Social Connections Mapping Tool methodology (Strang and Quinn Citation2021; Strang et al. Citation2020), researchers facilitated discussions with workshop participants around three hypothetical scenarios. These were chosen to elicit connections across the categories of social bonds, bridges and links. The scenarios were explored sequentially and framed as follows: to whom would you or someone in your community speak to or go to for help if (a) the hot water in their home wasn’t working (b) their child was unhappy at school and (c)they were looking for work? Having established whom, if anyone, participants would speak to in the first instance, researchers probed for second-level connections asking whom participants might approach if the problem was not initially resolved. These discussions were visually represented in connection maps produced during these workshops, an example of which is reproduced at . Together with field notes gathered by facilitators during the workshop, these comprised the data from this phase of the work.

In the second phase, remote interviews were conducted with a total of 29 individuals from 13 families living in Glasgow and Birmingham. Their demographic profile is outlined in . This paper focuses on interview data gathered from the 21 adult family members, alongside qualitative data gathered from the 61 participants in the workshops. The experiences of the children who took part are the subject of a separate article. These locations were selected in agreement with practice partners as the families in these sites were being supported by family project workers to whom interviewers could pass on any concerns for safety and wellbeing. No such concerns were recorded. Due to logistical restrictions imposed by Covid-19 lockdown, interviews were conducted by phone or online video calling services. Professional interpreters were provided if requested. The research team originally envisaged speaking to each family member separately. However, seven of the eleven couples interviewed chose to speak with the team jointly. In the four other families, adults took part in separate interviews.

Table 2. Interview participants.

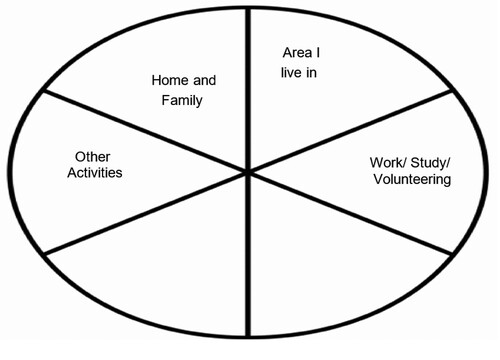

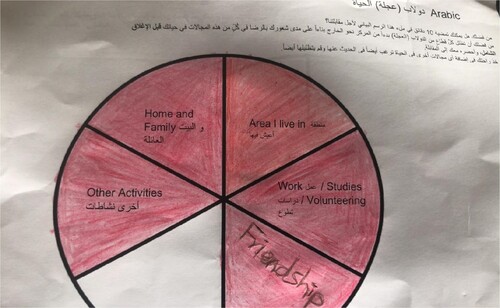

Interviews were semi-structured, using an interview schedule alongside an adapted ‘Wheel of Life’ visual tool reproduced at .Footnote1 Paper copies of the wheel were posted to participants prior to interview, with a child-specific wheel provided for any children aged 12 or over. Translated written instructions encouraged participants to shade the diagram prior to the interview to indicate how fulfilled they felt in various areas of their lives. Participants interpreted this instruction in different ways. Some chose to colour code the segments as shown in , where participants explained ‘they had selected red as it was a bright colour that reflected how positively they were living before lockdown’. Their completed version of the diagram then served as a guide for discussion in the subsequent interview.

In both phases, informed consent was explained verbally before the activity and translated information sheets, including a child-friendly version for remote interviews, were provided. In workshops, participants signed consent forms to confirm their agreement. In remote interviews, verbal consent was obtained at the outset. Ethical approval for both phases of the study was granted by the Queen Margaret University Ethics Committee (phase one: REP 0190, phase two: REP 0222).

Limitations & positionality

Interviews were conducted with a small sample of reunited families, and so findings cannot be taken as fully representative of people arriving on Family Reunion visas in the UK. Participants in the second phase were all receiving support from two third sector organisations. Families who had chosen not to engage with this specialist service, or lived in areas where it was not available, might have different experiences of navigating statutory systems without the support of an allocated caseworker. The team are aware of the power dynamics that can influence interviewee participation, and of the potential effect of two team members’ profile as white, British-born researchers (Mackenzie, McDowell, and Pittaway Citation2007). While the use of interpreters, translated information and a two-stage informed consent process mitigated this, there is a risk that participants did not feel able to discuss all aspects of their experiences in the UK.

Analysis

Collation and analysis of data from the workshops occurred in two stages. Field notes and visual diagrams were reviewed immediately after each workshop by the team. This produced a set of emerging themes, which was added to as each workshop was completed. These were then used by the researchers to manually code the full set of diagrams and notes once this research phase was complete. Data from the remote interviews were analysed using an interpretive phenomenology approach (Matua and Van Der Wal Citation2015; Noon Citation2018). All transcripts or notes relating to each family were analysed in turn, firstly by each individual researcher and then jointly with the two other fieldwork researchers and the Principal Investigator. In this way, data gathered from each family was reviewed as a distinct phenomenon or case. After this initial analysis the team proceeded to a more traditional inductive coding phase. Each researcher manually coded an agreed sample of interview notes and transcripts. The team then met to compare their coding schemes before proceeding to a second manual coding phase using the agreed coding framework.

Results

Three themes emerged from our analysis: the differential experiences of refugees when building social links with the education and housing systems; the role of third sector organisations and longer-established co-nationals in brokering families’ contact with public services; and refugees’ acceptance that they would have to navigate limited public services for some time before moving toward independence.

Social links: a mixed picture

Reunion for the families in our cohort had been relatively recent. While sponsors’ time in the UK ranged from 14 months to 9.5 years (see ), in all but one of the families, arriving spouses and children had been in the UK for less than a year. Every family member who participated spoke of the importance of having been reunited. Being together as a family was perhaps the single most important supportive factor in participants’ lives (Baillot et al. Citation2021). However, against the backdrop of this moment of joy, the structural demands of integrating as a family placed new stressors onto people’s lives. Only one family in the interview cohort were living in sustainable, suitable accommodation at the time of the interviews, and 15 children of the 36 who were old enough to be in education were not yet formally registered in school or college. Most workshop participants were living in temporary accommodation and had not yet managed to get their children into schooling, with school registration appearing to be more problematic in some cities than in others. Thus, sponsors and their arriving family members were, often – after a period of relative stability post asylum decision – once again thrust into the rigours of navigating the statutory homelessness, social housing allocation and education systems.

Families’ direct relationships with these systems would certainly seem to conform to Szreter and Woolcock’s definition of social links as being relationships that connect people to public services which may be their only pathway to meeting essential needs such as shelter and food (Szreter and Woolcock Citation2004). Our data suggests that families’ experiences of forming and mobilising links of this sort were qualitatively different when engaging with the statutory housing sector as compared with the education system. The housing allocation system emerged as being relatively inflexible in both Glasgow and Birmingham. Several family interviewees recounted being told that they had to accept offers of housing that in some cases were unsuitable or unsustainable, and had not felt empowered to challenge this:

I’ve got no choice. If I have my way, I don’t know, anywhere they give me because we can’t dictate, we can’t say. Like when I got this house, you can’t say no to your house. Whatever they give you, you have to just take it like that, you know. (G10, female sponsor)

In contrast, where families were concerned or dissatisfied with the school allocation process, there were examples of people having some success in actively pursuing school registration or challenging decisions as to school allocations. Two of the families interviewed in Glasgow had challenged decisions to enrol their children at schools that were either too far from their homes or resulted in siblings being separated; two more families recounted pursuing their children’s school registration through direct contact with schools, and in one case, registering them only after satisfied that the schools in question had been rated ‘outstanding’. The mother of one family in Glasgow approached the school directly several times and was repeatedly advised to apply online. It was only after she pushed back against this advice that she finally obtained the assistance she needed.

they took the information and they filled the application form for me and they submitted it […] they accepted it, they put all the information and I got my daughter enrolled in the same school. (G13, female spouse)

Actually, I’ll be honest with you, I don’t think that if I request like that they will change for me […] I don’t think that they will listen to me. (B4, male sponsor)

Mediating connections

As beneficiaries of a third sector integration support service, it is perhaps unsurprising that families’ connections with third sector organisations emerged as important facilitators of contact with statutory systems. The role of the refugee voluntary sector in the UK in providing a safety net for those who are excluded from statutory systems has already been documented (Mayblin and James Citation2019) and resonates with the increasing emphasis across society for individuals to engage in acts of care that compensate for failures in state provision (Caduff Citation2019, 788). With only two exceptions in the interview cohort, these organisations constituted a vital connection that mediated families’ contacts with agencies of the state. These connections with specialist charities had been central to successfully exercising their rights to family reunion – the precursor for family members’ arrival in the UK. They had also enabled them to navigate some of the difficulties and barriers outlined above. As a refugee sponsor explained:

I got all the help and support from the [project partner], since even before my family arrived, because they helped me with the family reunion, they booked the tickets for them, and then after they arrived they helped me with the forms. [they] also helped me to settle in the first hotel until I get this house. (B5, male sponsor)

There was a bit of mess […] we shared that with the housing officer […] they told us we have to pay and we just received, it’s like a tribunal or a court just as a warning if we don’t clear the debt […] they just referred us to another lady who wasn’t very helpful. But, at the end, we shared it with the [third sector organisation] and you know, at the end it was sorted. (G7, male sponsor)

Missing links?

Two families in the interview cohort appeared to be without any strong connection that could help with the moment of transition post-reunion. Both were living in Birmingham and, while in one of these families, children were registered in school, in another neither their housing nor schooling seemed to be in place. Indeed, that family’s housing was so poor that they were living in unsanitary conditions at the time of interview, with a rat infestation and no hot water. The experience of trying to register their daughters in school provides a counterpoint to the examples above. Despite trying to build and leverage linking connections with three different institutions – the school, the Council and a third sector organisation – the interviewee found that language had proven an insurmountable barrier that resulted in her daughters missing a full year of education:

Registering the kids at school has been really difficult. We have had lots of problems with the school, it hasn’t been easy at all […] We tried to speak to the council about this but they said to follow up with the schools […] As there is a language barrier there, we weren’t able to follow this up properly with the school. Both of my daughters have because of this missed out on a year of school. (B12, female spouse)

I already told my housing officer about the overcrowding […] from the beginning, they told me, ‘You are going to stay for a while in this house or in this flat, because we don’t have many places with five bedrooms’. (G8, male sponsor)

when we came, we just want to – they want just to see their father, so we didn’t care that we are all – me and him and all of us – six people in one room, we didn’t feel that bad … Now thanks God, he give us flat, we’re having separate kitchen like that, so it’s step-by-step. (B4, female spouse)

So, if I have the job for civil engineer I believe I can just look after myself without any depending on Universal Credit so that will be so amazing for me. (G9, male sponsor)

Discussion

Contested categories

Grouping the social relationships formed and utilised by refugee families to navigate statutory systems in the UK into neat categories is far from easy. The above findings tend to confirm the blurring of distinctions between bonds, bridges and links in a post-migration context (Strang and Quinn Citation2021; Wessendorf and Phillimore Citation2019; Ryan Citation2018). Many families were reliant upon, and successfully mobilised, relationships with co-nationals to access informational and material resources as well as to feel more settled and supported in their new lives. Thus, co-nationals and extended family members played a role that brokered recent arrivals’ access to, and connection with statutory services.

This study also highlighted ambiguities in families’ descriptions of their relationships with third sector organisations. Many of the third sector organisations referenced by families were themselves large, national institutions. There is growing recognition that the voluntary sector in the UK has taken on many of the roles and remits of statutory services for marginalised communities including asylum seekers and refugees (Mayblin and James Citation2019). It could be argued that connections between these organisations and their beneficiaries are most akin to the social links described by Szreter and Woolcock (Citation2004), with the power differential between them being inherently more vertical than horizontal in nature. Yet, in this study, families often described their relationships with voluntary sector organisations not in terms of the formal institution itself, but rather through descriptions of close and trusted connections with named workers, with some going so far as to describe these named workers as being like family members. This may reflect the circumstances of rupture experienced by refugees. As Pittaway and colleagues explain, refugees almost by definition find themselves far from their usual trusted social networks. It is precisely because of this rupture in social connections that service providers become crucially important in the early stages of settlement and may have to substitute for previously dense networks of support that refugees have had to leave behind (Pittaway, Bartolomei, and Doney Citation2016).

While these relationships may then be broadly positive, this can raise the spectre of potential over-dependence on service providers. One family for example, described a worker from one of the project partners as being ‘like parents’. This implied a relationship of dependency that echoes Greene’s suggestion that strong and trusted relationships with settlement services might indicate greater emotional distress amongst refugees and so not necessarily correlate with the development of social capital by and amongst refugees (Greene Citation2019).

More fundamentally, the blurring of distinctions between the form and function of connections speaks to the importance of considering the impact of time upon integration and the social relationships that enable it. In the snapshot of time represented by the cohort in this study, we can see that a relationship with the same person can be both defined by similarity (we both come from the same country) and difference (I have only just arrived, but you have been here a while). In this way, the form of the relationship can have some of the quality of a bond, yet in certain – but importantly not all – ways, can function as a bridge. Relationships with third sector settlement services may provide a vital sense of security and support in the early stages of a family’s life in the UK, when there are a multitude of complex systems to navigate. However, over time such relationships may lose some of the closeness of a bond and become more of a formal link as the family reduce their reliance on voluntary sector support. This points to the potential for further research to explore the interplay between social connection and the passage of time.

Confirming the role of time in moving towards independence

There is increasing awareness of the risks and inaccuracies inherent in depicting refugees as hapless victims of circumstance, passive in the face of the obstacles ahead of them (Pupavac Citation2008; Rainbird Citation2012). An over-emphasis on systems barriers can reinforce images of refugee vulnerability. The current study instead demonstrates that some refugees, in certain circumstances, are ready and willing not only to challenge decisions they feel are incorrect, but to independently pursue solutions. Even families’ acceptance of system limitations can be understood not as a manifestation of helplessness but instead of their active role in ‘finding productive paths through a maze of ups and downs’ (Lenette, Brough, and Cox Citation2013: 648). As in previous studies (Strang, Baillot, and Mignard Citation2018), refugees themselves, emphasised their desire not only to successfully navigate systems but to then move on towards ever greater independence. Having to rely upon and build connections with public services may be a necessary step in pathways to refugees’ own goals, but these – paradoxically – are connections that refugees would rather not have in the longer term. This longer-term view of integration as a process that depends on time and must be taken ‘step by step’ was strongly expressed by this research cohort. Families had already survived long periods of separation. New challenges that occurred could be tackled because the family unit being back together was more important by far than any temporary difficulties families might face.

Multi-directionality

Despite the clear evidence of refugees’ desire and ability to build and leverage their own connections, it remains clear that this alone cannot always overcome the structural confines of statutory systems. As families’ divergent experiences of the housing and education systems illustrate, strong links in one realm do not necessarily translate to other domains, especially where systems are not receptive to connection. In line with Szreter and Woolcock’s original formulation of social links, the response of those who hold is the power is as important as the efforts of those who, from positions of relative disadvantage, seek to connect with public services to access their rights (Szreter and Woolcock Citation2004).

The findings from this small cohort of interviewees suggest that it is in the realm of statutory housing provision that most change may be required before refugees can effectively access their rights to safe and suitable accommodation that ‘provides the conditions in which positive social connections and networks … can flourish’ (Pittaway, Bartolomei, and Doney Citation2016, 411). This reminds us of the multi-directionality of integration itself (see Ndofor-Tah et al. Citation2019). An analysis of the role of social connections in navigating statutory systems cannot solely focus on refugees’ social labour in forming and leveraging connections. Agencies too, particularly those that control access to services such as education and housing, must be open to adaptation to meet the needs not just of refugees but of the increasingly socially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse communities that they are designed to serve (Benton, McCarthy, and Collett Citation2015). If they fail to do so, it appears that refugees can continue to face incomprehension if not hostility when they seek to exert their rights.

Conclusion

Reunited refugee families are called upon to navigate not only the emotions that come with reunion after significant periods of separation, but also the complexities of statutory systems. Their experiences confirm the crucial and various roles played by family, friends and third sector organisations in advocating for, and enabling refugees to access their rights. They also demonstrate inconsistencies in the ways that policy and research draw boundaries between social relationships based on ethnicity and nationality rather than on a consideration of the value of each relationship to refugees themselves. We, therefore, argue for a shift in focus away from implicit assumptions about the types or identities of the people with whom refugees develop relationships. Instead, future research should seek to explore the relational and structural factors that refugees themselves report have helped or hindered their integration pathways. Integration will be promoted most effectively by tailoring support to enable crucial relationships and remove structural barriers.

Moreover, the study provides further evidence that the social labour of forming positive relationships does not sit solely on the shoulders of refugees and other migrants. Integration is, as the UK Home Office has itself repeatedly confirmed, a shared responsibility. It is not just new residents but also the statutory systems that control their access to resources that must change and adapt if all members of communities are to be able to fulfil their potential. This paper suggests that while some statutory systems such as education have to some extent adapted to the new realities of a mobile and diverse society, others – most prominently the statutory homeless and housing systems – continue to require significant investment if they are to be truly responsive to those who are entitled to its assistance.

These findings point to the need to critically analyse the function as well as the form of refugees’ social connections. Recognising the changing function that social relationships play over time, for example with service providers or longer established co-national friends and acquaintances, unlocks important routes whereby refugees can access rights and opportunities and establish independent lives.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families who participated in the study, whose generous sharing of experiences made our research possible. Our project partners provided invaluable assistance in recruiting participants. We are grateful to Professor Alastair Ager for his comments on an initial version of this article, and to our colleague Bryony Nisbet for her work during the extension of the Family Reunion project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This tool was adapted from commonly used life-coaching tools, for example: https://www.kingstowncollege.ie/coaching-tool-the-wheel-of-life/

References

- Ager, A., and A. Strang. 2008. “Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Refugee Studies 21 (2): 166–191. doi:10.1093/jrs/fen016.

- Allport, G. W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Anthias, F. 2007. “Ethnic Ties: Social Capital and the Question of Mobilisability.” The Sociological Review 55 (4): 788–805. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2007.00752.x.

- Askins, K. 2015. “Being Together: Everyday Geographies and the Quiet Politics of Belonging.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 14 (2): 470–478. Accessed January 16, 2023. https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/1175.

- Baillot, H., L. Kerlaff, A. Dakessian, and A. Strang. 2021. Pathways and Potentialities: The Role of Social Connections in the Integration of Reunited Refugee Families [Project Report]. Musselburgh: Queen Margaret University.

- Benton, M., H. McCarthy, and E. Collett. 2015. Into the Mainstream: Rethinking Public Services for Diverse and Mainstream Populations. Brussels: Migration Policy Institute Europe.

- Berry, J. W. 1997. “Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation.” Applied Psychology 46 (1): 5–34. doi:10.1080/026999497378467.

- Beswick, J. 2015. Not So Straightforward: The Need for Qualified Legal Support in Refugee Family Reunion. London: British Red Cross.

- Bloch, A. 2008. “Refugees in the UK Labour Market: The Conflict Between Economic Integration and Policy-led Labour Market Restriction.” Journal of Social Policy 37 (1): 21–36. doi:10.1017/S004727940700147X.

- Bourgonje, P. 2010. Education for Refugee and Asylum Seeking Children in OECD Countries: Case Studies from Australia, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Brussels: Education International.

- British Red Cross. 2020. The Long Road to Reunion. Accessed December 14, 2022. https://www.redcross.org.uk/about-us/what-we-do/we-speak-up-for-change/improving-the-lives-of-refugees/refugee-family-reunion

- Brown, L. D., G. Bammer, S. Batliwala, and F. Kunreuther. 2003. “Framing Practice-Research Engagement for Democratizing Knowledge.” Action Research 1 (1): 81–102. doi:10.1177/14767503030011006.

- Caduff, C. 2019. “Hot Chocolate.” Critical Inquiry 45 (3). doi:10.1086/702591.

- Casey, L. 2016. The Casey Review: A Review into Opportunity and Integration. London: Crown Office.

- Coleman, J. S. 1988. “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital.” American Journal of Sociology 94: S95–S120. doi:10.1086/228943.

- Connell, J., G. Mulvey, J. Brady, and G. Christie. 2010. One Day we Will be Reunited: Experiences of Refugee Family Reunion in the UK. Glasgow: Scottish Refugee Council.

- Demireva, N. 2019. Immigration, Diversity and Social Cohesion Migration Observatory Briefing. Oxford: COMPAS, University of Oxford.

- Gower, M., and T. McGuinness. 2020. The UK’s Family Reunion Rules: a comprehensive framework? (House of Commons Briefing Paper 07511).

- Granovetter, M. S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78: 1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469.

- Granovetter, M. S. 1983. “The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited.” Sociological Theory 1: 201–233. doi:10.2307/202051.

- Greene, R. N. 2019. “Kinship, Friendship and Service Provider Social Ties and How They Influence Wellbeing among Newly Resettled Refugees.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 5: 237802311989619–11. doi:10.1177/2378023119896192.

- Kearns, A., and E. Whitley. 2015. “Getting There? The Effects of Functional Factors, Time and Place on the Social Integration of Migrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (13): 2105–2129. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1030374.

- Lenette, C., M. Brough, and L. Cox. 2013. “Everyday Resilience: Narratives of Single Refugee Women with Children.” Qualitative Social Work 12 (5): 637–653. doi:10.1177/1473325012449684.

- Mackenzie, C., C. McDowell, and E. Pittaway. 2007. “Beyond 'Do No Harm': The Challenge of Constructing Ethical Relationships in Refugee Research.” Journal of Refugee Studies 20 (2): 299–319. doi:10.1093/jrs/fem008.

- Marsden, R., and C. Harris. 2015. “We Started Life Again”: Integration Experiences of Refugee Families Reuniting in Glasgow. Glasgow: British Red Cross.

- Matua, A., and D. M. Van Der Wal. 2015. “Differentiating Between Descriptive and Interpretive Phenomenological Research Approaches.” Nurse Researcher 22 (6): 22–27. doi:10.7748/nr.22.6.22.e1344.

- Mayblin, L., and P. James. 2019. “Asylum and Refugee Support in the UK: Civil Society Filling the Gaps?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (3): 375–394. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1466695.

- Mayblin, L., M. Wake, and M. Kazemi. 2020. “Necropolitics and the Slow Violence of the Everyday: Asylum Seeker Welfare in the Postcolonial Present.” Sociology 54 (1): 107–123. doi:10.1177/0038038519862124.

- Morrice, L., L. Tip, R. Brown, and M. Collyer. 2020. “Resettled Refugee Youth and Education: Aspiration and Reality.” Journal of Youth Studies 23 (3): 388–405. doi:10.1080/13676261.2019.1612047.

- Mountz, A. 2020. The Death of Asylum: Hidden Geographies of the Enforcement Archipelago. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ndofor-Tah, C., A. Strang, J. Phillimore, L. Morrice, L. Michael, P. Wood, and J. Simmons. 2019. Home Office Indicators of Integration Framework 2019: third edition. [Online]. Accessed 2 November 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/835573/home-office-indicators-of-integration-framework-2019-horr109.pdf

- Noon, E. 2018. “Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis: An Appropriate Methodology for Educational Research?” Journal of Perspectives Applied Academic Practice 6: 75–83. doi:10.14297/jpaap.v6i1.304.

- Nunn, C., C. McMichael, S. M. Gifford, and I. Correa-Velez. 2016. “Mobility and Security: The Perceived Benefits of Citizenship for Resettled Young People from Refugee Backgrounds.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (3): 382–399. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1086633.

- Penninx, R. 2019. “Problems of and Solutions for the Study of Immigrant Integration.” Comparative Migrant Studies 7 (13). doi:10.1186/s40878-019-0122-x.

- Phillimore, J. 2021. “Refugee-Integration-Opportunity Structures: Shifting the Focus from Refugees to Context.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (2): 1946–1966. doi:10.1093/jrs/feaa012.

- Pittaway, E., L. Bartolomei, and G. Doney. 2016. Community Development Journal 51 (3): 401–418. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsv023.

- Pupavac, V. 2008. “Refugee Advocacy, Traumatic Representations and Political Disenchantment.” Government and Opposition 43 (2): 270–292. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2008.00255.x.

- Putnam, R. D. 2000. “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital.” In Culture and Politics: A Reader, edited by L. Crothers, and C. Lockhart, 223–234. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rainbird, S. 2012. “Asylum Seeker 'vulnerability': The Official Explanation of Service Providers and the Emotive Responses of Asylum Seekers.” Community Development Journal 47 (3): 405–422. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsr044.

- Refugee Council/ Oxfam. 2018. Safe but Not Settled: The Impact of Family Separation on Refugees in the UK. London: Refugee Council / Oxfam.

- Rousseau, C., M.-C. Rufagari, D. Bagilishya, and T. Measham. 2004. “Remaking Family Life: Strategies for re-Establishing Continuity among Congolese Refugees During the Family Reunification Process.” Social Science & Medicine 59: 1095–1108. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.011.

- Ryan, L. 2018. “Differentiated Embedding: Polish Migrants in London Negotiating Belonging Over Time.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (2): 233–251. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341710.

- Schinkel, W. 2013. “The Imagination of ‘Society’ in Measurements of Immigrant Integration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (7): 1142–1161. doi:10.1080/01419870.2013.783709.

- Scottish Refugee Council, Refugee Council and UNHCR. 2018. A Journey Towards Safety: A Report on the Experiences of Eritrean Refugees in the UK. [Online]. Accessed 16 September 2021. https://www.unhcr.org/uk/protection/integration/5b8fe8694/a-journey-towards-safety-a-report-on-the-experiences-of-eritrean-refugees.html

- Spencer, S., and K. Charlsey. 2021. “Reframing Integration: Acknowledging and Addressing Five Core Critiques.” Comparative Migration Studies 9 (18). doi:10.1186/s40878-021-00226-4.

- Spencer, S., and K. Charsley. 2016. “Conceptualising Integration: A Framework for Empirical Research, Taking Marriage Migration as a Case Study.” Comparative Migration Studies 4 (18). doi:10.1186/s40878-016-0035-x.

- Spicer, D. N. 2008. “Places of Exclusion and Inclusion: Asylum-Seeker and Refugee Experiences of Neighbourhoods in the UK.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34 (3): 491–510. doi:10.1080/13691830701880350.

- Strang, A., and A. Ager. 2010. “Refugee Integration: Emerging Trends and Remaining Agendas.” Journal of Refugee Studies 23 (4): 589–607. doi:10.1093/jrs/feq046.

- Strang, A., H. Baillot, and E. Mignard. 2018. “‘I Want to Participate.’ Transition Experiences of new Refugees in Glasgow.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (2): 197–214. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341717.

- Strang, A., O. O’Brien, M. Sandliands, and R. Horn. 2020. Help-seeking, Trust and Intimate Partner Violence: Social Connections Amongst Displaced and Non-displaced Yezidi Women and Men in the Kurdistan Region of Northern Iraq. Conflict and Health 14, Article 61.

- Strang, A. B., and N. Quinn. 2021. “Integration or Isolation? Refugees’ Social Connections and Wellbeing.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (1): 328–353. doi:10.1093/jrs/fez040.

- Szreter, S., and M. Woolcock. 2004. “Health by Association? Social Capital, Social Theory, and the Political Economy of Public Health.” International Journal of Epidemiology 33 (4): 650–667. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh013.

- Wessendorf, S., and J. Phillimore. 2019. “New Migrants’ Social Integration.” Embedding and Emplacement in Superdiverse Contexts Sociology 53 (1): 123–138. doi:10.1177/0038038518771843.

- Wilson, W., and C. Barton. 2021. Tackling the Under-supply of Housing in England. House of Commons Library Briefing Paper 07671. Accessed September 21, 2021. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7671/CBP-7671.pdf

- Woolcock, M. 1998. “Social Capital and Economic Development: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis and Policy Framework.” Theory and Society 27: 151–208.doi:10.1023/A:1006884930135.

- Zetter, R. 2015. Protection in Crisis: Forced Migration and Protection in a Global Era. Washington DC: Migration Policy Institute. Accessed January 16, 2023. Research: Protection in Crisis: Forced Migration a.. | migrationpolicy.org.