?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In the present research ‘factorial survey experiment’ method is applied to examine and compare the differential impact of immigrants’ characteristics on anti-immigrant sentiment among the majority and minority populations in Israel. Potential immigrants were described by six characteristics (gender, continent of birth, education, religion, level of religiosity and reason for migration) in a fractionalised sample of 252 vignettes (organised in 42 decks of 6 vignettes each). They were presented to two national representative samples of the Jewish (majority) and of the Arab (minority) populations in Israel. Respondents were asked to express attitudes toward admission and allocation of rights to hypothetical immigrants. The analysis reveals that Arabs are more supportive of immigrants than Jews, and that the most influential characteristic on formation of attitudes is immigrants’ religious origin, with Jews preferring Jewish immigrants but objecting non-Jews (especially Muslims) and Arabs favouring non-Jews (especially Muslims) immigrants. Discussion of the findings in light of theory leads to the conclusion that sentiments toward immigrants are shaped, first and foremost, by preferences regarding the ethnic and cultural homogeneity of society; much more than by threat of economic competition.

Introduction

The ever-growing body of research on attitudes toward immigrants has reached a three-fold conclusion. First, anti-immigrant sentiment and opposition to immigration are associated with fear of economic competition, and with the perceived threat that immigration purportedly poses to cultural values and the homogeneity of the population (e.g. QuillianCitation1995; Scheepers, Gijsberts, and Coenders Citation2002; Semyonov, Raijman, and Gorodzeisky Citation2006, Citation2008). Second, anti-immigrant sentiment tends to be more pronounced among socioeconomically vulnerable individuals, and among people holding conservative values (e.g. Scheepers, Gijsberts, and Coenders Citation2002; Semyonov, Raijman, and Gorodzeisky Citation2006, Citation2008). Third, anti-immigrant sentiment tends to be more pronounced in places where the flow of the immigrant population is large, where economic conditions are depressed, and where rightwing nationalist parties enjoy broad support (e.g. Quillian Citation1995; Scheepers, Gijsberts, and Coenders Citation2002; McLaren Citation2003; Lahav Citation2004; Semyonov, Raijman, and Gorodzeisky Citation2006, Citation2008).

In addition, a series of recent studies have begun underscoring the role played by immigrants’ characteristics in shaping attitudes toward immigrants and ethnic discrimination in the labour market. For example, through meta-analysis, Heath and Di Stasio (Citation2019) reported considerable evidence for racial discrimination against non-white immigrants in the British labour market. Yemane (Citation2020) detected convincing evidence for hiring discrimination against non-white and Muslims in the US labour market and Veit and her colleagues (Citation2022) found that non-European origin is likely to result in greater risk of hiring discrimination in European countries. Likewise, field experiments conducted by Di Stasio and her colleagues (Citation2021) in Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain and the UK reveal ‘alarming’ levels of hiring discrimination toward visible male immigrants and against Muslims. Koopmans, Veit, and Yemane (Citation2019) suggest that ethnic, racial and religious groups whose values are distant from the German average are at a greater risk of labour market discrimination and Helbling and Traunmüller (Citation2020) argue that opposition to Muslim immigrants in Britain is based, first and foremost, on fear of religious fundamentalism. Notwithstanding the contribution of these recent studies to a better understanding of the sources for anti-immigrant sentiment and ethnic discrimination, we know very little about whether the impact of immigrants’ attributes on attitudes varies across sub-populations within the host society. In other words, to the best of our knowledge there is no study to date that has systematically investigated the differential impact of immigrants’ attributes on the formation of attitudes toward immigrants across sub-groups of the host population.

Therefore, in the present research, we seek to contribute to the literature on formation of attitudes toward immigrants by exploring, comparing and discussing, within the context of Israeli society, the differential impact of immigrants’ characteristics on anti-immigrant sentiment among Jews (the dominant majority population) and Arabs (the ethnic minority population). To achieve our goal, we implemented an experimental factorial survey designed specifically for the present research. Because the study was carried out in the context of Israel, we begin by outlining the nature of immigration and ethnic stratification in Israel. We then present theoretical considerations and previous research on the topic, and from this literature we formulate theoretical expectations. These are followed by a description of the experimental design adopted here, and by the statistical analysis. Finally, we present and discuss the findings and their meaning.

The setting: ethnicity and immigration in Israel

Israel is a multi-ethnic society with a population of more than nine million people. About 75 percent of the Israeli population is Jewish; about 20 percent are Arabs, the overwhelming majority Muslims. Most of the Jewish population of Israel is either immigrants or offspring of immigrants. These immigrants came to Israel from a wide variety of countries, in a series of immigration flows between the turn of the twentieth century and the present day (e.g. Semyonov and Gorodzeisky Citation2012). It should be emphasised however, that Jewish immigration to Israel is viewed as a ‘returning Diaspora,’ and thus differs from traditional immigration societies. In fact, Israel is considered the homeland of the Jewish people; according to the Law of Return and the Law of Nationality, every JewFootnote1 and his/her children have the right to be granted Israeli citizenship upon arrival (repatriate status). Following a 1970 reform, the rights conferred by the Law of Return were extended to the grandchildren of Jews and their nuclear families – even if they are not Jewish.Footnote2 It should be also noted that, unlike other immigrant societies, the State of Israel provides immigrants entering under the Law of Return with generous financial and institutional support during their first years in the country, an act intended to ease and facilitate their integration into society. In other words, the State of Israel and the Israeli public are committed to the successful integration of Jewish immigrants into society.

In contrast to the Jewish immigrants, Arabs have lived in the region for generations and can be viewed as an indigenous minority population. Despite some ethnic disparities within the Jewish population, the most meaningful ethnic split in Israel is between the Jewish majority and the Arab minority, with Arabs being disadvantaged in every aspect of socioeconomic status. The status of Arabs in Israel should be understood within the unique historical circumstances associated with the establishment of the state and the nature of the regional Israeli-Arab conflict. In fact, at the time that Jews began immigrating to Palestine (at the turn of the twentieth century) Arabs constituted a numerical majority both in the region and in Palestine. However, after the establishment of the state in 1948, and the subsequent War of Independence, Palestinian Arabs were cut from the Arab world, becoming an ‘involuntary national minority’ – not only in terms of size, but also in terms of social, economic and political standing. Arabs and Jews are spatially and socially segregated, with an over-concentration of Arabs in villages and small towns in peripheral regions of the country, where employment opportunities are limited (e.g. Lewin-Epstein and Semyonov Citation1994). Consequently, many Arabs have to search for employment outside their place of residence, and hence compete with Jews for economic opportunities. Under such conditions, Arabs are at a disadvantaged position in society in general, and in the Israeli labour market in particular (e.g. Lewin-Epstein and Semyonov Citation1994; Khattab and Miaari Citation2013).

In recent decades, Israel has become a destination for two additional major groups of non-Jewish immigrants: labour migrants and asylum seekers/refugees. Whereas the Jewish and Arab populations are all citizens of the state, labour migrants, asylum seekers and refugees (the latter group mostly from African countries) are not citizens of the state. Nor can they become citizens of Israel, or even permanent residents. Overseas labour migration became a significant feature of Israeli society in the middle of the 1990s, when a managed migration scheme for low-skilled foreign workers was enacted to replace Palestinian commuters from the Occupied Territories in the secondary labour market (Kemp and Raijman Citation2008). The majority of labour migrants in Israel are currently employed in three main sectors: care-giving (57%), agriculture (22%) and construction (13%). According to the Population and Immigration Authority (PIBA Citation2020), 119,476 migrant workers resided in Israel at the end of 2019; only around 85 percent of them had work permits. Many labour migrants who entered the country with work permits leave their legal employers to work without a permit, or do not depart at the end of their contracts, thus rendering their presence in Israel illegal. Labour migrants arrive in Israel from a range of impoverished countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe. They are a source of cheap labour for the low-paying, manual and menial jobs that the local population is reluctant to take up. Nevertheless, the local population tends to hold negative sentiments toward such workers (e.g. Raijman and Semyonov Citation2004; Raijman Citation2013; Gorodzeisky Citation2013).

The presence of refugees and asylum seekers in Israel is associated with the recent political violence in African countries. Specifically, the African asylum seekers escaped war-ravaged areas, mostly in Sudan and Eritrea, to find refuge in Israel by crossing the Egypt-Israel border. By the end of 2019, the total number of asylum seekers residing in Israel was estimated to be circa 30,000 people. Although the Israeli government has granted Sudanese and Eritrean asylum seekers temporary ‘group protection’ status that is liable to be ended at any time. Furthermore, the state has enacted several practices aimed at excluding asylum seekers from Israeli society and deterring new ones from coming. The practices and restrictions include policies of border control, new legislation initiatives and the construction of detention centres and a fence along the country’s border with Egypt. Moreover, the state only grants asylum seekers a meagre legal status and a very limited set of social rights. Subsequently, the public discourse on the place of asylum seekers in Israel has become highly politicised, with asylum seekers often being referred to as ‘infiltrators’ – a term with clear negative connotations. In such a context of reception, public attitudes toward asylum seekers in Israel have become quite negative (e.g. Hercowitz-Amir, Raijman, and Davidov Citation2017; Hochman and Hercowitz-Amir Citation2017; Ariely Citation2021).

In general, Israeli immigration policy can be characterised as a double standard regime: total inclusion of Jewish immigrants versus extreme exclusion of non-Jewish immigrants. That is, whereas Israel adopted a policy of absolute ‘acceptance-encouragement’ for Jewish immigrants, the Israeli immigration regime is highly restrictive – in fact, exclusionary – for non-Jewish immigrants. Unsurprisingly, Israel’s policy toward immigrants is reflected in public views; studies consistently show that the overwhelming majority of Jews in Israel strongly support the entry of Jewish immigrants but strongly oppose the admission of non-Jewish immigrants, regardless of citizenship status or their motive for migration (e.g. Hochman and Hercowicz-Amir Citation2017; Raijman, Hochman, and Davidov Citation2022). By way of comparison, opposition on the part of Israeli Arabs to non-Jewish immigrants was found to be less extreme, with Arabs being more tolerant of non-Jewish migration than Jews (e.g. Raijman and Semyonov Citation2004; Hochman Citation2017).

Previous studies on attitudes toward immigrants in Israel have, to date, focused on the impact of respondents’ characteristics on attitudes toward various groups of immigrants. Curiously, however, no researchers have explored the differential impact of immigrants’ characteristics on attitudes across members of the majority (i.e. Jewish) and the minority (i.e. Arab) populations. In the present research, thus, we shift the focus from the impact of respondents’ attributes to the impact of immigrants’ characteristics on attitudes toward immigrants among Arabs and Jews. We do so by implementing the Factorial Survey Method to disentangle the unique impacts of different immigrant attributes on anti-immigrant attitudes among Israeli Jews and Arabs. We contend that the Israeli context provides a unique opportunity to examine whether immigrants’ characteristics differentially affect attitudes toward admission and allocation of rights to immigrants among members of the majority and minority populations.

Theory and previous research

Researchers studying the formation of attitudes toward immigrants have long shared the view that anti-immigrant sentiment can be understood as a defensive reaction toward threats and challenges (whether real or perceived) posed by immigrants to the exclusive superiority of the dominant population with respect to access to resources and privileges (see e.g. Quillian Citation1995; Scheepers, Gijsberts, and Coenders Citation2002; Semyonov, Raijman, and Gorodzeisky Citation2006, Citation2008; Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2009). The central tenet of the ‘competition’ model contends that attitudes toward out-group populations are shaped by group identification, and by the struggle between groups over power, resources, rewards and collective identity. According to the model fear of competition is likely to prompt opposition to immigration and engender a rise in anti-immigrant sentiment.

Most studies on the determinants of anti-immigrant sentiment lend support to the ‘competitive threat’ theoretical model, suggesting that immigrants are viewed by large portions of the domestic population not only as ‘outsiders’ but also as a threat to economic well-being, cultural values and homogeneity of the national population (e.g. Lahav Citation2004; Semyonov, Raijman, and Gorodzeisky Citation2006, Citation2008). Indeed, consistent with the ‘competitive threat’ theoretical logic, researchers have repeatedly observed that anti-immigrant sentiments and opposition to immigration tend to be more pronounced among socioeconomically vulnerable populations on the one hand, and among individuals holding conservative views on the other hand.

Even though studies on the issue have uniformly observed that anti-immigrants sentiments are more pronounced among socioeconomically vulnerable and conservative respondents, several researchers contend that attitudes toward immigrants are also influenced by the attributes of the immigrant, with a tendency to be more negative toward ethnic minorities and members of religious denominations which differ from that of the host society. More specifically, studies in the European context have found that the local population is especially hostile toward Muslim, Roma and immigrants from racial or ethnic groups that differ from the local population (e.g. Strabac and Listhaug Citation2008; Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2009, Citation2019; Ford Citation2011; Ben-Nun Bloom, Arikan, and Lahav Citation2015a; Ben-Nun Bloom, Arikan, and Courtemanche Citation2015b). Likewise, an emerging body of research based on survey experiments underscores the role that a variety of immigrants’ attributes play in shaping attitudes toward immigrants. More specifically, these studies found that characteristics such as an immigrant’s reason(s) for migration (e.g. Findor et al. Citation2021), education, professional skills and economic prospects (e.g. Helbling and Kriesi Citation2014; Iyengar, Aarts, and van Gerven Citation2015; Turper et al. Citation2015), country of origin, race, ethnicity, religion and skin colour (e.g. Hellwig and Sinno Citation2017; Iyengar, Aarts, and van Gerven Citation2015) all exert significant influence on the host population’s attitudes toward immigration and immigrants.

Theoretical expectations

Notwithstanding growing support for the thesis that immigrants’ attributes shape attitudes toward immigration, it remains unclear whether the impact of immigrants’ attributes on attitudes is uniform across the population, or whether it varies across sub-groups – specifically between ethnic minority and majority groups. While alternative theoretical models may lead to different and even conflicting expectations regarding the ways in which immigrants’ attributes impact attitudes, they all lead to the expectation that the impact would vary between members of the ethnic minority and members of the majority population.

More specifically, the logic embodied in the ‘competitive threat’ theoretical model leads us to expect that members of the ethnic minority group (i.e. Arabs in Israel) would object more than members of the majority population (i.e. Jews in Israel) to immigrants, and especially to immigrants of low and subordinate socioeconomic status. The greater objection to immigrants among members of the ethnic minority group can be attributed to their vulnerable status, and hence to the greater threat of competition for social and economic resources that immigrants pose. However, theoretical explanations, which trace the roots of hostility toward out-group populations to threats to national identity, cultural values and the homogeneity of the population (e.g. Fetzer Citation2000; Castles, de Haas, and Miller Citation2014), lead us to expect that the presence of immigrants (especially immigrants of different ethnic origin, or who subscribe to a different religion than the majority population) will be perceived as a threat, especially among members of the dominant-majority population, but not necessarily by members of the minority population. In fact, it is reasonable to expect that members of the minority population would not view change in the ethnic and cultural homogeneity of a given society in negative terms. In other words, whereas members of the majority population may perceive the presence of immigrants of a different ethnicity or religion as a severe threat to national identity, cultural values and the homogeneity of the population, members of minority ethnic populations may not view such a threat in negative terms.

The ‘in-group favouritism’ view contends that people tend to evaluate members of their own group in more positive terms than members of outgroups. According to this view, people tend to embrace and reward members of the in-group more than members of out-group populations (e.g. Allport Citation1954; Brewer Citation1979; Tajfel et al. Citation1971; Balliet, Wu, and De Dreu Citation2014; Mustafa and Richards Citation2019). While ‘in-group favouritism’ may create strong and well-functioning in-groups in a society, it may also lead to intergroup tension, especially in multi-ethnic societies (e.g. Balliet, Wu, and De Dreu Citation2014). In highly divided multi-ethnic societies, such as Israel, the majority and minority populations are likely to differently perceive, and thus, to embrace or reject in-group and out-group migrants.

A somewhat different view to formation of attitudes is offered by the cultural ‘marginality’ model (Fetzer Citation2000). According to the logic embodied in the ‘marginality’ model, members of subordinate minority groups (as a marginal population) are more likely than members of the majority population to identify and sympathise with marginalised and vulnerable populations (i.e. immigrants). Therefore, members of ethnic minority groups are more likely to support and embrace immigrants in general, and immigrants with a religious and /or ethnic background that differs from that of the majority population in particular. This is so because members of minority population groups are also subject to discrimination and subordination.

In line with the theoretical considerations, a series of alternative and even conflicting expectations regarding the ways that immigrants’ attributes influence Jews’ and Arabs’ attitudes toward admission of immigrants to the country and allocation of equal rights to migrants can be derived from the various models. According to the ‘economic competition-threat’ model, we expect Arabs to object more than Jews to all types of immigrants – whether asylum seekers, labour migrants, or Jewish immigrants – because Arabs (as members of an ethnic minority group) are more threatened by the competition generated by immigrants than Jews. According to this logic, we expect Arab respondents to especially object to labour migrants than to other types of immigrants. Likewise, we expect all respondents, whether Jews or Arabs, with low level of education to object more to immigrants with low levels of education.

According to the ‘cultural competition-threat’ model, we expect opposition to immigration to be more pronounced among Jews than among Arabs for all types of immigrants other than two groups (i.e. Jewish immigrants and repatriates). In fact, alongside this logic, we expect Jewish respondents to be more supportive and embracing of repatriates and Jewish immigrants than Arab respondents. Likewise, we expect Arab respondents to embrace and support Muslim and non-European immigrants, but to object to Jewish immigrants.

The in-group favouritism view leads to the expectation that Jewish respondents would be more supportive of Jewish immigrants and that Arab respondents would be most supportive of Muslim or Christian immigrants. We also expect the Jewish respondents (being largely repatriates or descendants of repatriates) to express more positive attitudes toward repatriates than toward other migrants’ groups. Along the same logic, we expect women (both Jews and Arabs) to be more supportive of women migrants than of men migrants and religious people (both Jews and Arabs) to be more supportive of religious migrants than of secular ones.

The rationale of the ‘marginality’ theoretical model leads us to expect opposition to immigration to be less pronounced among Arabs than among Jews, for all types of immigrants. We expect Arabs’ opposition to immigration to be especially low toward Muslim immigrants, toward migrants of non-European origin and toward asylum seekers, the latter viewed as the most vulnerable and disadvantaged group of immigrants.

In what follows, thus, we seek to bridge the gap in the literature by testing the hypotheses and expectations regarding the differential impact of immigrants’ characteristics on attitudes toward admission and the allocation of rights to immigrants, among Arabs and Jews in Israel. More specifically, we examine the ways in which six immigrants’ characteristics (i.e. reason for migration, religion and level of education, regional origin, gender and level of religiosity) differentially shape attitudes toward various groups of immigrants among Jews and Arabs.

Method, data source and variables

Research design

The methodology adopted here for estimating the impact of immigrants’ attributes on anti-immigrant sentiment among Jews and Arabs is Factorial Survey Experiment Design (Auspurg and Hinz Citation2014; Auspurg, Hinz, and Walzenbach Citation2019). Factorial survey experiments are designed to evaluate multi-dimensional descriptions of situations within which researchers can examine the comparable relevance of each dimension (i.e. immigrants’ characteristics) with regard to the dependent variables (in the present study: attitudes towards admission and granting equal rights to immigrants). Therefore, Factorial Survey Experiment design can be viewed as the most suitable method for the research question being addressed here.

The hypothetical migrants that were presented to the respondents possessed a mix of six different characteristics associated with immigrants: gender (man/woman); continent of origin (Asia/Africa/Europe); education (with academic education/without academic education); religion (Jewish/Muslim/Christian); religiosity level (secular/somewhat religious/extremely religious); and reason for migration (repatriate under the Law of Return/labour migrant/asylum seeker).Footnote3 To estimate the relative impact of each of the six characteristics, a fractional sample of 252 vignettes was drawn out of the vignette universe.Footnote4 The 252 vignettes were randomly distributed across 42 decks of 6 vignettes each. The decks were assigned at random to respondents, with a random variation of vignette order. Detailed checks confirmed the random assignment of decks to the respondents. Each of the 252 vignettes was evaluated a minimum of 11 times and a maximum of 17 times. Each vignette (presented to the respondents) was cast in the following sentence: ‘A man (or woman) from Africa (or Asia or Europe) with academic degree (no degree), extremely religious (or somewhat religious or secular) Muslim (or Christian or Jew), fleeing from war or political persecution and seeking refuge in Israel (or wants to come to Israel as a labour migrant, or is entitled to come to Israel under the Law of Return).’

After being introduced to the vignettes, the respondents were asked to respond to the following two questions: ‘To what extent do you agree or disagree that Israel should allow him/her to come and live here’ (answers on 11-point scale, ranging from 0 ‘strongly disagree’ to 10 ‘strongly agree’; and ‘To what extent do you agree or disagree that immigrants should be granted with equal rights’ (answers on 11-point scale, ranging from 0 ‘strongly disagree’ to 10 ‘strongly agree’). We contend that the responses to the two attitudes questions capture the degree of anti-immigrant sentiment (the lower the score, the stronger the anti-immigrant sentiment). Although the two questions capture some form of anti-immigrant sentiment and are somewhat interrelated, each represents a distinct dimension of exclusionary attitudes (Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2009). The first question pertains to exclusion from the country, the latter to exclusion from access to equal rights.

Data source

The data for the analysis were obtained from a national representative sample of the Israeli population aged 21–70.Footnote5 The sampling procedure was based on a multi-stage stratified random sampling frame from all geographical regions in Israel, yielding 600 Jewish respondents and 308 Arab respondents (with response rates 51% for the Jewish sample and 65% for the Arab sample).Footnote6 The survey mode that was used for data collection was CAPI (computer-assisted personal interview), with the questionnaires handed to the respondents on tablets by the interviewers. The questionnaire was completed by the respondent, with interviewers present to assist in the event of problems or clarifications. Questionnaires to the Jewish sub-sample were presented in Hebrew, and to the Arab sub-sample in Arabic. Respondents within the households were selected based on ‘last birthday method’—the last person in the household to celebrate their birthday. Data collection took place during the month of December 2020, amid the Coronavirus pandemic. For respondents who were sceptical about giving the interviewer access to their home, tablets were handed over to the target person while the interviewer waited outside. In addition to the vignette module, the survey contained a few additional questions regarding attitudes, and socio-demographic information about the respondent.

Because the present study is intended to compare the Jewish and the Arab populations of Israel, the vignette evaluations of the 600 Jewish respondents and 308 Arab respondents were analysed separately. As mentioned earlier, each respondent was presented with six vignettes. Therefore, the procedure yielded a total of 3595 vignettes in the Jewish sample, and 1842 vignettes in the Arab sample.Footnote7 Detailed checks confirmed the random assignment of decks to participants in both groups. Correlation matrix of vignette dimensions in the realised sample indicates coefficients close to zero – with the exception of reason for migration and religion (r = .398), these two dimensions being correlated by design.

Variables and measurements

The variables were classified into three categories: (1) characteristics of the immigrants (derived from the vignettes), (2) socio-demographic attributes of the respondents; and (3) two vignette evaluation scales, i.e. respondents’ attitudes toward admission of immigrants and toward allocation of equal rights to immigrants (as indicators of anti-immigrant sentiment or exclusionary attitudes). The three categories of variables were designed to enable an analysis within the framework of the Factorial Survey Experiment, in which the attributes of the immigrants serve as the independent variables, the socio-demographic attributes of respondents (for both ethnic groups) as control variables, and the evaluation scales of the vignettes (attitudinal variables) as the dependent variables.

The two 11-point scales measuring attitudes toward admission of immigrants to the country and toward allocation of equal rights to immigrants were described in detail in the ‘research design’ section. They constitute the dependent variables. The characteristics of the immigrants (obtained from the vignettes as described in details in the ‘research design’ section) include: immigrant’s education (as a proxy of human resources with academic education = 1), religion (dummy variables distinguishing Muslims, Christians and Jews); reason for migration (dummy variables distinguishing asylum seekers, labour migrants, and repatriates); continent of origin (captured by dummy variables that can serve as a proxy of race), level of religiosity (as an indicator of conservatism) and gender (female = 1). Respondents’ characteristics were included to adjust for compositional effects of the minority and majority groups. The socio-demographic attributes of the Jewish and Arab respondents include: gender (female = 1), age (in years), formal schooling (in years), level of religiosity (based on self-definition measured on a 5-point scale ranging from secular = 1 to highly religious/orthodox = 5) as a proxy for conservatism, and satisfaction with household income (which is a distinction between those who are very comfortable with the family income versus all others, coded 0/1). A detailed description of the variables, their definitions and measurements are provided in Appendix.

The analytical model

In order to arrive at accurate estimates of the net effects of immigrants’ attributes on attitudes toward immigrants, we estimated linear regression equations with cluster-robust standard errors to account for the nested structure of vignettes within respondents (see Cameron and Miller Citation2015). The model can be formally presented by the following notation:

where Yir is attitudes toward admission to the country or attitudes toward allocation of equal rights to an immigrant i, given by respondent r; X is a vector of six immigrant characteristics and b is a vector of its coefficients; Z is a vector of respondents’ characteristics and c is a vector of its coefficient of their characteristics; eir is the cluster-robust error term. We estimated the model for the two dependent variables (attitudes towards granting entry to the country, and attitudes towards granting rights to the immigrants living in the country) across both groups (Jews and Arabs). In order to compare group differences between minority and majority groups, we followed the straightforward procedure of the Chow Test, pooling the data from both groups and fully interacting all variables with the group dummy (Chow Citation1960). Thus, statistical significance of group differences can be reported (for the complete models and for each single coefficient).

Analysis and findings

Descriptive overview

Before presenting the results of the analysis, we display in , for a descriptive overview, the characteristics (mean or percentage) of the majority (Jews) and the minority (Arabs) populations. We also present in the table the mean values of attitudes (measured on an 11-point scale) toward the admission of immigrants to the country, and toward granting them equal rights, among the Arab and Jewish populations.

Table 1. Mean values (or proportions) of the characteristics of the Jewish and Arab respondents included in the analysis.

Consistent with previous studies on Jewish-Arab differences in Israel, the data reveal meaningful and significant differences in the socio-demographic characteristics of the two sub-populations. More specifically, the data reveal that Arabs are younger than Jews; they have a lower level of formal education; and they are more conservative than Jews, as indicated by level of religiosity. Arab respondents were less satisfied than Jewish respondents with their household income.

The data also reveal meaningful differences between Arab and Jewish respondents in their attitudes toward immigrants, with Arabs being more tolerant than Jews with regard to both entry and allocation of rights to immigrants. More specifically, when considering the value 5 as the point of neutrality on the attitude scale, it appears that the average scores among Jewish respondents toward ‘admission’ and ‘granting rights’ to immigrants ( = 6.1 and

= 5.6, respectively), although somewhat positive, are significantly lower than the average attitudes expressed by Arabs for the same items (

= 6.3 and

= 6.3).

Immigrants’ characteristics and attitudes toward admission

While the descriptive statistics displayed in provide illuminating and interesting information, what is not clear from the data is the extent to which specific characteristics of immigrants differentially affect attitudes of Jews and Arabs. Therefore, and in order to arrive at accurate estimates of the net effect of immigrants’ attributes on attitudes toward immigrants among Jews and Arabs, we estimated a series of linear regression equations in which vignettes describing the immigrants’ profiles were nested in respondents, thus adjusting the standard errors. According to the analytical model described above, in each equation, we let attitudes toward the admission of immigrants be a function of attributes of the immigrants (i.e. level of education, religion, reason for migration, gender, origin and religiosity), while controlling for socio-demographic attributes of the respondents. The equations were estimated separately for the Jewish and Arab respondents, and pooled analysis was used to test for the statistical significance of the differences between the groups.

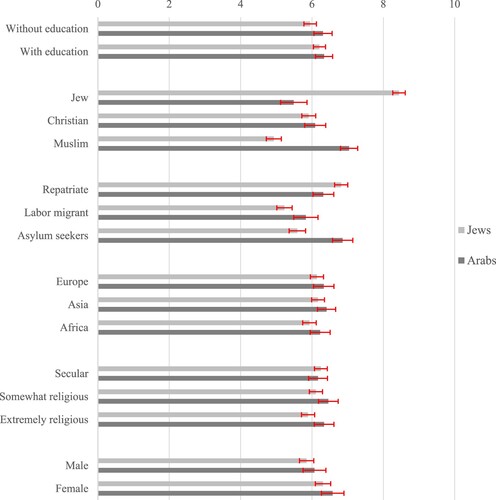

The first question the research sought to answer is whether attitudes toward acceptance of immigrants to the country are influenced by the characteristics of the immigrants; and the second, whether the impact of the characteristics on attitudes differed for Jews and Arabs. The estimated coefficients of the equations are displayed in columns of Appendix Table A2 (admitting migrants to Israel) and A3 (granting equal rights to immigrants); the predicted values of the mean attitudes by each characteristic (obtained from the regression equations) are visually illustrated in for admitting migrants to Israel – separately for Jewish and Arab respondents. Additionally, 95% confidence intervals are displayed.

Figure 1. Predicted values (with 95% CI in red) of support for admitting migrants to Israel, by immigrant’s characteristics (separately for Jewish and Arab respondents)a. Evaluation task: ‘To what extent do you agree or disagree that Israel should allow her/him to come and live here?’ Scale from 0 ‘strongly disagree’ to 10 ‘strongly agree’. Predictions for each vignette level calculated while all other variables are held at means (N = 3553 in Jewish majority; N = 1788 in Arab minority).

Results presented in (and Appendix A2) point to a straightforward twofold conclusion. First, attitudes toward admission of immigrants are strongly influenced by the characteristics of the immigrants. That is, different characteristics do matter, as they differentially shape attitudes toward admission. Second, immigrants’ characteristics differentially affect the attitudes of Arabs and Jews, with some characteristics mattering more than others. More specifically, a comparison between the Jewish respondents and the Arab respondents underscores substantial and meaningful differences between the two populations with regard to the type of immigrants that members of each group favour or oppose admitting to the country. First and foremost, whereas Jewish respondents strongly support the admission of Jewish immigrants ( = 8.44), they object to the entry of non-Jewish immigrants, especially Muslim immigrants (

= 4.93). By contrast, Arab respondents prefer the admission of non-Jewish immigrants over Jewish immigrants. The preference among Arabs is most pronounced with regard to Muslim immigrants (

= 7.04) and least evident with regard to Jewish immigrants (

= 5.49). Attitudes of Arabs toward the admission of Christian immigrants (

= 6.09) are somewhat in between the mean attitudes toward the admission of Jewish and Muslim immigrants.

Differences between Arabs and Jews in attitudes toward the admission of immigrants are also evident with regard to the reason for migration (or legal status). Jewish respondents express strong support for the admission of repatriates to the country, as evidenced by the mean value = 6.82 on the attitudes scale. However, they are less likely to support the entry of either asylum seekers (b = −1.23 in column 3 of Table B1) or labour migrants (b = −1.59), as compared to repatriates. By way of contrast, Arab respondents are more likely to support the admission of asylum seekers (

= 6.86), but less likely to support the admission of labour migrants or repatriates.

Immigrant’s education (as a proxy for human-capital resources) does not affect attitudes among Arabs toward the admission of immigrants (as implied by the negligible size of the coefficient for education in Equation (2)). Indeed, among Arab respondents, the mean of the respondents’ attitudes toward the admission of academically educated immigrants ( = 6.34) is identical, for all practical purposes, to the mean attitudes toward the admission of immigrants without academic credentials (

= 6.31). Jews, however, prefer immigrants with an academic education over those without academic training, as indicated by the positive and statistically significant coefficient for academic education (b = .263 in column 3 of Appendix Table A1).

The impact of immigrant’s gender and continent of origin on attitudes toward admission is relatively moderate (as compared to the impact of religion and reason for migration) and similar among the Jewish and Arab respondents. More specifically, both Jews and Arabs are more likely to favour admission of women (over men) and to oppose admission of African immigrants (over Europeans or Asians), though the coefficient for Arabs is not significant. Immigrant’s level of religiosity, however, plays a different role in shaping attitudes toward admission of immigrants among Jews and Arabs, with Jews being more supportive of admitting secular immigrants and Arabs being more supportive of religious immigrants. The difference may be a result of differential views regarding conservative values and populations among Arabs and Jews.

The coefficients (displayed in Appendix A2) reveal, consistent with previous studies on the issue, that attitudes toward admission of immigrants are also associated with characteristics of the respondents, with women and highly educated respondents, whether Jews or Arabs, being more supportive of admission of immigrants. In addition, support for admission tends to decline with age and level of religiosity and to increase with level of household income (though the effects are significant only among the Jewish respondents).

Regression results displayed in online Appendix A1–A2 include a series of interaction terms estimated to test the extent to which selected characteristics of respondents differentially affect attitudes toward specific types of immigrants.Footnote8 Contrary to the hypotheses, the data reveal (both among the Jewish and the Arab respondents) that neither respondent's level of education nor level of religiosity, nor respondent’s gender, interact, respectively, with immigrant's education, religiosity and gender to produce divergent levels of support for admission to the country.

Immigrants’ characteristics and attitudes toward allocation of rights

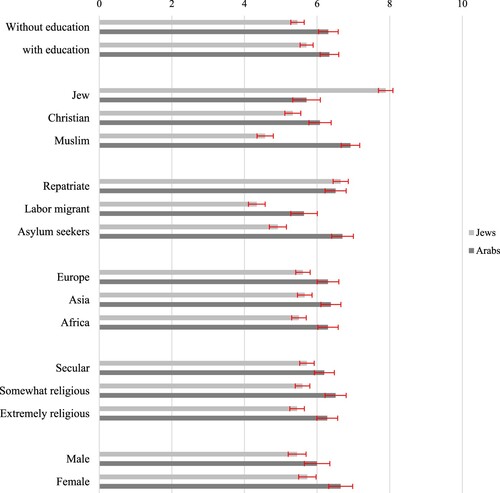

Attitudes toward the admission of immigrants to the country constitute only one dimension of anti-immigrant sentiment; attitudes toward granting equal rights to immigrants can serve as another dimension of anti-immigrant sentiment. Therefore, in the analysis that follows, we estimated regression equations predicting the extent to which attitudes toward the allocation of equal rights to immigrants are affected by the characteristics of the immigrants and by respondents’ characteristics. The regression equations are estimated separately for the Jewish and Arab respondents (columns 1–4 of Appendix Table A3). The predicted mean attitudes, by characteristic of the immigrants, for Arabs and Jews (as obtained from the equations) are presented graphically in for a visual illustration.

Figure 2. Predicted values (with 95% CI in red) of support for granting rights to immigrants, by immigrant’s characteristics (separately for Jewish and Arab respondents)a. Evaluation task: ‘ If this person comes to live in Israel, to what extent do you agree or disagree that she/he should have the same social rights (such as social services and health services) as Israeli citizens?’ Scale from 0 ‘strongly disagree’ to 10 ‘strongly agree’. Predictions for each vignette level calculated while all other variables are held at means (N = 3457 in Jewish majority; N = 1776 in Arab minority).

The findings regarding allocation of rights are, with a few minor exceptions, almost a mirror image of the findings reported in the previous section regarding attitudes toward admission of immigrants. First, similar to the findings regarding admission to the country, Jews tend to oppose the allocation of equal rights to non-Jewish immigrants, and especially to Muslim immigrants ( = 4.57). Arabs, by contrast, are more likely to support allocation of equal rights to non-Jewish immigrants, especially to immigrants of the Muslim faith (

= 6.92). Curiously, the positive attitudes of Arabs (who are mostly Muslim) toward granting equal rights to Christian immigrants are also quite substantial (

= 6.08) and more positive than their attitudes toward Jewish immigrants (

= 5.71).

Second, similar to attitudes toward admission, Jewish respondents are less likely to support the allocation of equal rights to either labour migrants or asylum seekers than to repatriates ( = 6.65 for repatriates). Furthermore, the data reveal that the Jewish respondents are, on average, more likely to oppose than support the allocation of equal rights to either labour migrants (

= 4.34) and asylum seekers (

= 4.91). By way of contrast, Arab respondents are less likely to support allocation of equal rights to labour migrants (

= 5.63) than to either repatriates (

= 6.51) or asylum seekers (

= 6.69). Yet, it should be noted that on average, Arabs are more likely to support than oppose the allocation of equal rights to all groups of immigrants.

Third, and similar to the findings reported for attitudes toward admission, level of education of the immigrant (as a proxy for human-capital resources) does not impact Arabs’ attitudes toward the allocation of rights to immigrants (the coefficient is negligible in size). By contrast, Jews are more likely to support granting equal rights to immigrants with an academic education (b = .248 in column 3 of Appendix Table A3) than to other immigrants.

Fourth, neither immigrant’s gender nor immigrant’s continent of origin affects attitudes toward allocation of equal rights to immigrants of either Jews or Arabs. The coefficients of these variables are small and below levels of statistical tests of significance. Immigrant’s level of religiosity, however, exerts some curious effects on attitudes toward allocation of rights, with Jewish respondents expressing greater opposition to granting such rights to ‘extremely religious’ immigrants (b = −.268 in Equation (3)), and Arabs greater support for allocation of such rights to ‘somewhat religious’ immigrants (b = .312 in column 4). We have no clear and straightforward explanation for the differences between the two groups.

Similar to previous studies and similar to the results regarding attitudes toward admission, respondents’ characteristics are also associated with attitudes toward granting equal rights to immigrants. First, women, whether Jewish or Arabs, are more supportive than men of allocation of equal rights to immigrants. Second, support for allocation of equal rights tends to decline with age and with level of religiosity (but the effects are significant only for Jewish respondents) and tends to increase with level of education and family income (with the effect for education being significant only for Arabs and for family income only for Jews).

In the online Appendix Tables A3 and A4, we present a series of interaction terms to examine whether selected characteristics of respondents differentially affect attitudes toward granting equal rights to specific types of immigrants. Specifically, we estimated the respective effects of the interactions between respondent’s gender, education and religiosity and immigrants’ gender, education and religiosity on attitudes toward granting equal rights to immigrants.Footnote9 The data reveal that, except for one coefficient (i.e. the interaction between respondent’s education and immigrant’s education in the Arab sample), all interaction terms are small and not statistically significant. Apparently, due to fear of economic competition, opposition to allocation of equal rights to immigrants without academic education is more extreme among Arabs with lower levels of education (the most vulnerable sub-population) as compared to Arabs with higher levels of education.

Conclusions and discussion

The findings presented here reveal that characteristics of immigrants take on different meaning for members of minority and majority populations; thus, immigrants’ attributes differentially shape attitudes toward immigrants among the majority and the minority populations of the host society. In general, attitudes toward the admission of immigrants and granting immigrants with equal rights were, on average, more positive and supportive than negative and hostile. Yet, the tendency to express positive-supportive, rather than negative attitudes toward immigrants was more evident among members of the minority population (Arabs) than among members of the majority population (Jews). The more supportive views expressed by members of the minority population lend stronger support to the marginality thesis than to the economic competition-threat thesis.

Further analysis reveals that attitudes toward immigrants (whether among the majority population or the minority population) are highly influenced by the ethno-religious characteristics of the immigrant providing firm support to expectations derived from the ‘in group favouritism’ and the ‘cultural threat’ theoretical views. The data show that members of the majority population (Jews) prefer Jewish immigrants and repatriates but object to admission and allocation of rights to non-Jewish immigrants, asylum seekers and labour migrants. At the same time, members of the minority population (Arabs) are more likely to express strong support for admission and allocation of rights to non-Jewish immigrants, especially Muslim immigrants. Indeed, sentiments toward immigrants are influenced, first and foremost, by in-group favouritism and by preferences regarding the homogeneity of the population and societal culture – much more so than by fears and threats of economic competition.

Despite the major role played by ethno-religious characteristics of the immigrants in shaping anti-immigrant sentiment, we cannot flatly refute the economic competition threat thesis. The competitive threat model leads us to expect that those who are more threatened by social and economic competition (prompted by the presence of immigrants) are more likely to express greater opposition toward immigrants. Consistent with this expectation, the findings reveal that individuals of vulnerable socioeconomic status, whether Jews or Arabs, are less supportive of the admission of, and allocation of rights to immigrants. Likewise, and consistent with the economic competition thesis, Arabs (the disadvantaged ethnic minority), as compared to Jews, expressed less supportive attitudes toward labour migrants i.e. those more likely to be a source of economic competition against Arabs.

In the present paper, then, we contribute to the literature on anti-immigrant sentiment by focusing on the differential impact of immigrants’ characteristics on attitudes toward immigrants in the majority and minority populations of Israel. We suggest that the more sympathetic attitudes and stronger support toward immigrants expressed by Arabs imply that members of the disadvantaged minority population (as a marginal population) are more likely to identify and embrace minority populations than members of the majority population. The extreme preference expressed by Jews toward the admission of Jewish immigrants and repatriates and Arabs’ strong preference of Muslim immigrants imply that sentiments toward immigrants are shaped by in-group favouritism. The objection of Jews to non-Jewish immigrants implies that attitudes are also driven by fears and sentiments regarding the homogeneity of the population and cultural values, especially among member of the majority population. Indeed, sentiments regarding the composition of the population play a major and more important role than fears and threats of economic competition in shaping attitudes toward immigrants. Although the study was carried out in the context of Israeli society, we believe that the findings reported here have theoretical implications that extend beyond the borders of Israeli society. It is our hope, indeed, that the issues discussed here will be further examined in future research in other contemporary societies and in other social contexts.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (57 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Shir Caller for assistance in preparation, organisation and careful analysis of the data and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 According to halakha (Jewish religious law), a Jew is a person who was born to a Jewish mother or has converted to Judaism, and is not a member of another religion.

2 For example, a Christian or a Muslim can enter the country under the auspices of the Law of Return only if s/he is married to a Jew.

3 Note that there were two illogical combinations excluded: a Jewish immigrant coming to Israel as either a labour migrant or an asylum seeker. For all practical purposes, being Jewish awards one the legal status of ‘repatriate’, regardless of all other attributes.

4 As suggested by Auspurg and Hinz (Citation2014), we employed the SAS (Statistical Analysis Software) program %MktEx provided by Kuhfeld (Citation2010) to draw a D-efficient design of 252 vignettes out of the vignette universe of all 756 logically possible combinations of vignette levels (D-efficiency of 91.8). One-way and two-way interactions of vignette dimensions have been taken into consideration to avoid confounding. Important to note again that implausible cases of Jewish immigrants coming to Israel as labour migrants or as asylum seekers were excluded.

5 The survey was conducted by Geocartography a leading Israeli company specialising in public opinion research. A total number of 55 interviewers participated in the survey: 35 Jews and 20 Arabs. Arab interviewers usually were from the residential area where the interviews were conducted.

6 The sampling unit is defined as a residential building in urban areas or 5 apartments (after skipping) in rural areas. In each apartment in the sampling unit, the interviewer tried to conduct an interview, and if it was not possible, s/he continued with the skipping method until all the relevant apartments in the sampling unit are skipped. If no interview was possible in any of these apartments, the interviewer returned to the apartments selected in the sampling unit up to two more times on different occasions, until an interview is conducted, or until a refusal to conduct an interview or there is an impediment to conduct the interview.

7 16 respondents (1.8%) provided no variation in their evaluations for the first scale (granting entry), while 34 respondents (3.7%) did so for the second scale (granting rights). We excluded these cases from regression analyses because the experimental variation did not work with these respondents.

8 Estimated equations with all possible interaction terms between respondent attributes and immigrants’ characteristics are displayed in online Appendix B1–B4.

9 Estimated equations with all possible interaction terms between respondent attributes and immigrants’ characteristics are displayed in online Appendix Tables C1–C4.

References

- Allport, W. Gordon. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. New York. Perseus Books.

- Ariely, G. 2021. “Collective Memory and Attitudes Toward Asylum Seekers: Evidence from Israel.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (5): 1084–1102. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1572499.

- Auspurg, K., and T. Hinz. 2014. Factorial Survey Experiments, Vol. 175. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Auspurg, K., T. Hinz, and S. Walzenbach. 2019. “Are Factorial Survey Experiments Prone to Survey Mode Effects?” In Experimental Methods in Survey Research, edited by P. Lavrakas, M. Traugott, C. Kennedy, A. Holbrook, E. de Leeuw, and B. West, 371–392. Hoboken: Wileys. doi:10.1002/9781119083771.ch19.

- Balliet, Daniel, J. Wu, and C. K. De Dreu. 2014. “Ingroup Favoritism in Cooperation: A Meta-Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 140 (6): 1556–1581. doi:10.1037/a0037737.

- Ben-Nun Bloom, P., G. Arikan, and M. Courtemanche. 2015b. “Religious Social Identity, Religious Belief, and Anti-Immigration Sentiment.” American Political Science Review 109 (2): 203–221. doi:10.1017/S0003055415000143.

- Ben-Nun Bloom, P., G. Arikan, and G. Lahav. 2015a. “The Effect of Perceived Cultural and Material Threats on Ethnic Preferences in Immigration Attitudes.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (10): 1760–1778. doi:10.1080/01419870.2015.1015581.

- Brewer, M. B. 1979. “In-group Bias in the Minimal Intergroup Situation: A Cognitive-Motivational Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 86 (2): 307–324. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.307.

- Cameron, A. C., and D. L. Miller. 2015. “A Practitioner’s Guide to Cluster-Robust Inference.” Journal of Human Resources 50 (2): 317–372. doi:10.3368/jhr.50.2.317.

- Castles, S., H. de Haas, and M. J. Miller. 2014. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. 5th ed. New York: Guilford Press.

- Chow, G. C. 1960. “Tests of Equality Between Sets of Coefficients in Two Linear Regressions.” Econometrica 28 (3): 591–605. doi:10.2307/1910133.

- Di Stasio, V., B. Lancee, S. Veit, and R. Yemane. 2021. “Muslim by Default or Religious Discrimination? Results from a Set of Harmonized Field Experiments.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (6): 1305–1326. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1622826.

- Fetzer, J. S. 2000. “Economic Self-Interest or Cultural Marginality? Anti-Immigration Sentiment and Nativist Political Movements in France, Germany and the USA.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 26 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1080/136918300115615

- Findor, A., M. Hruška, P. Jankovská, and M. Pobudová. 2021. “Re-examining Public Opinion Preferences for Migrant Categorizations.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 80: 262–273. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.12.004

- Ford, R. 2011. “Acceptable and Unacceptable Immigrants: How Opposition to Immigration in Britain is Affected by Migrants’ Region of Origin.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (7): 1017–1037. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2011.572423

- Gorodzeisky, A. 2013. “Mechanisms of Exclusion: Attitudes Toward Allocation of Social Rights to Out-Group Population.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (5): 795–817. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.631740

- Gorodzeisky, A., and M. Semyonov. 2009. “Terms of Exclusion: Public Views Towards Admission and Allocation of Rights to Immigrants in European Countries.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (3): 401–423. doi:10.1080/01419870802245851

- Gorodzeisky, A., and M. Semyonov. 2019. “Unwelcome Immigrants: Sources of Opposition to Different Immigrant Groups among Europeans.” Frontiers in Sociology 4: 24. doi:10.3389/fsoc.2019.00024

- Heath, A. F., and V. Di Stasio. 2019. “Racial Discrimination in Britain, 1969–2017: A Meta-Analysis of Field Experiments on Racial Discrimination in the British Labour Market.” The British Journal of Sociology 70 (5): 1774–1798. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12676

- Helbling, M., and H. Kriesi. 2014. “Why Citizens Prefer High-Over Low-Skilled Immigrants: Labor Market Competition, Welfare State, and Deservingness.” European Sociological Review 30 (5): 595–614. doi:10.1093/esr/jcu061

- Helbling, M., and R. Traunmüller. 2020. “What is Islamophobia? Disentangling Citizens’ Feelings Toward Ethnicity, Religion and Religiosity Using a Survey Experiment.” British Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 811–828. doi:10.1017/S0007123418000054

- Hellwig, T., and A. Sinno. 2017. “Different Groups, Different Threats: Public Attitudes Towards Immigrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (3): 339–358. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2016.1202749

- Hercowitz-Amir, A., R. Raijman, and E. Davidov. 2017. “Host or Hostile? Attitudes Towards Asylum Seekers in Israel and in Denmark.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 58 (5): 416–439. doi:10.1177/0020715217722039

- Hochman, O. 2017. “Perceived threat, social distance and exclusion of asylum seekers from Sudan and Eritrea in Israel.” Hagira 7: 45–66. (in Hebrew).

- Hochman, O., and A. Hercowitz-Amir. 2017. “(Dis) Agreement with the Implementation of Humanitarian Policy Measures Towards Asylum Seekers in Israel: Does the Frame Matter?” Journal of International Migration and Integration 18 (3): 897–916. doi:10.1007/s12134-016-0510-0

- Iyengar, S., K. Aarts, and M. van Gerven. 2015. “Who is Less Welcome?: The Impact of Individuating Cues on Attitudes Towards Immigrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (2): 239–259. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2014.912941

- Kemp, A., and R. Raijman. 2008. Migrants and Workers: The Political Economy of Labor Migration in Israel. Jerusalem: Van Leer Institute and Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House.

- Khattab, N., and S. Miaari, eds. 2013. Palestinians in the Israeli Labor Market: A Multi-disciplinary Approach. New York. Springer.

- Koopmans, R., S. Veit, and R. Yemane. 2019. “Taste or Statistics? A Correspondence Study of Ethnic, Racial and Religious Labour-Market Discrimination in Germany.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (16): S. 233–S. 252. doi:10.1080/01419870.2019.1654114

- Kuhfeld, W. F. 2010. Marketing Research Methods in SAS. Experimental Design, Choice, Conjoint and Graphical Techniques. Cary, N.C.: SAS Institute.

- Lahav, G. 2004. “Public Opinion Toward Immigration in the European Union: Does It Matter?” Comparative Political Studies 37 (10): 1151–1183. doi:10.1177/0010414004269826

- Lewin-Epstein, N., and M. Semyonov. 1994. “Sheltered Labor Markets, Public Sector Employment, and Socioeconomic Returns to Education of Arabs in Israel.” American Journal of Sociology 100 (3): 622–651. doi:10.1086/230576

- McLaren, L. M. 2003. “Anti-immigrant Prejudice in Europe: Contact, Threat Perception, and Preferences for the Exclusion of Migrants.” Social Forces 81 (3): 909–936. doi:10.1353/sof.2003.0038

- Mustafa, A., and L. Richards. 2019. “Immigration Attitudes Amongst European Muslims: Social Identity, Economic Threat and Familiar Experiences.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (7): 1050–1069. doi:10.1080/01419870.2018.1472387

- PIBA (Population and Immigration Authority). 2020. Data on Foreigners in Israel 2019. Population and Immigration Authority. https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/foreign_workers_stats/he/sum_2019.pdf.

- Quillian, L. 1995. “Prejudice as a Response to Perceived Group Threat: Population Composition and Anti-immigrant and Racial Prejudice in Europe.” American Sociological Review 60: 586–611. doi:10.2307/2096296

- Raijman, R. 2013. “Foreigners and Outsiders: Exclusionist Attitudes Towards Labor Migrants in Israel.” International Migration 51 (1): 136–151. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2011.00719.x

- Raijman, R., O. Hochman, and E. Davidov. 2022. “Ethnic Majority Attitudes Toward Jewish and non-Jewish Migrants in Israel: The Role of Perceptions of Threat, Collective Vulnerability, and Human Values.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 20 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1080/15562948.2021.1889850

- Raijman, R., and M. Semyonov. 2004. “Perceived Threat and Exclusionary Attitudes Towards Foreign Workers in Israel.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 27 (5): 780–799. doi:10.1080/0141987042000246345

- Scheepers, P., M. Gijsberts, and M. Coenders. 2002. “Ethnic Exclusionism in European Countries: Public Opposition to Civil Rights for Legal Migrants as a Response to Perceived Ethnic Threat.” European Sociological Review 18 (1): 17–34. doi:10.1093/esr/18.1.17

- Semyonov, M., and A. Gorodzeisky. 2012. “Israel: An Immigrant Society.” In International Perspectives: Integration and Inclusion, edited by J. S. Frideres and J. Biles, 147–165. Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Semyonov, M., R. Raijman, and A. Gorodzeisky. 2006. “The Rise of Anti-Foreigner Sentiment in European Societies: A Cross-National Multi-Level Analysis.” American Sociological Review 71 (3): 426–449. doi:10.1177/000312240607100304

- Semyonov, M., R. Raijman, and A. Gorodzeisky. 2008. “Foreigners’ Impact on European Societies: Public Views and Perceptions in a Cross-National Comparative Perspective.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 49: 5–29. doi:10.1177/0020715207088585

- Strabac, Z., and O. Listhaug. 2008. “Anti-Muslim Prejudice in Europe: A Multilevel Analysis of Survey Data from 30 Countries.” Social Science Research 37 (1): 268–286. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.02.004

- Tajfel, H., M. G. Billig, R. P. Bundy, and C. Flament. 1971. “Social Categorization and Intergroup Behavior.” European Journal of Social Psychology 1 (2): 149–178. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420010202.

- Turper, S., S. Iyengar, K. Aarts, and M. van Gerven. 2015. “Who is Less Welcome?: The Impact of Individuating Cues on Attitudes Towards Immigrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (2): 239–259. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2014.912941

- Veit, S., H. Arnu, V. Di Stasio, R. Yemane, and M. Coenders. 2022. “The “Big Two” in Hiring Discrimination: Evidence from a Cross-National Field Experiment.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 48 (2): 167–182. doi:10.1177/0146167220982900

- Yemane, R. 2020. “Cumulative disadvantage? The Role of Race Compared to Ethnicity, Religion, and Non-White Phenotype in Explaining Hiring Discrimination in the US Labour Market.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 69: 100552.

Appendices

Appendix Table A1: The variables, their operational definition, and mean (or proportion)

Appendix Table A2: Coefficients of OLS equations predicting support for admitting migrants to Israel by immigrant’s characteristics and respondent’s attributes (for Jewish majority and Arab minority in Israel)

Table

Appendix Table A3: Coefficients of OLS equations predicting support for granting migrants with equal rights, by immigrant’s characteristics and respondent’s attributes (for Jewish majority and Arab minority in Israel)

Table