ABSTRACT

Over 220,000 asylum seekers and refugees (ASR) lived in the United Kingdom in 2021. Traumatic experiences lived during the different phases of the migration process make people seeking asylum vulnerable to mental health conditions, including post-traumatic stress and depression. Assessments conducted by various local authorities since 2016 stress the need to improve ASR’s access to appropriate mental health support, but lack clarity on how to achieve this. This article explores perceptions of mental health support needs for ASR, and contrasts them to service provision. Data were collected via semi-structured interviews with nine ASR and six individuals who provide wellbeing support to ASR living in Brighton and Hove, and were analysed via thematic analysis using NVivo. Three main themes emerged, relating to the need for holistic mental health support for ASR, the disjunctive between perceived needs and the available support, and the barriers to accessing existing services. Findings highlight the need for holistic, specialised, culturally sensitive and sustainable mental health support for ASR, and illustrate how training healthcare receptionists on the rights and entitlements of ASR and greater support services coordination can help strengthen ASR’s access to the available support services and their mental wellbeing.

1. Introduction

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees there were 89.3 million forcibly displaced people worldwide at the end of 2021 as a result of persecution, conflict, violence and human rights violations, 4.6 million of which were seeking asylum globally (UNHCR Citation2022a). 48,540 applications for asylum were placed in the United Kingdom (UK) for the same year, 63% more than the previous year, and the highest level since 2003 (Home Office Citation2022). The top six countries of nationality for asylum applications in the UK were Iran, Iraq, Eritrea, Albania, Syria and Afghanistan.

In the UK, individuals can apply for asylum once they have entered the country regardless of how they entered. People often seek asylum in the UK because of linguistic links, the presence of family in the country and the perception of the UK as a safe and politically stable country (Crawley and Hagen-Zanker Citation2019). However, many have no choice over their destination and are transported to the UK by agents and facilitators (Crawley Citation2010). While their claim is being processed by the Home Office, asylum seekersFootnote1 are not allowed to work and are instead entitled to receive financial support. The standardised amount for adults in 2022 is £40.85 per week for clothing, food and toiletries.Footnote2 During this time, people seeking asylum can also live free of charge in accommodation provided by the Home Office, which could place them anywhere in the UK (UK Government Citation2022a). These benefits stop 28 days after a successful asylum decision, meaning that once recognised as refugees they have 28 days to find somewhere to live, open a bank account, obtain a National Insurance Number, and either start working or setup a Universal Credit claim (Citizens Advice Citation2022). If their application is unsuccessful, they will become destitute with no recourse to public funds, be asked to leave the UK, and may be deported to their home countries. The refusal rate in 2019 was 49% (Home Office Citation2022).

Research worldwide illustrates how each one of the three phases of migration lived by people seeking asylum (pre-migratory, migratory, and post-migratory) is associated with traumatic experiences that can severely harm their mental health and wellbeing in the short and long run (see for instance Kirmayer et al. Citation2011; Dangmann et al. Citation2020; Dowling, Kunin, and Russell Citation2020). Besides the trauma, stress, and anxiety that often relate to the socio-political, economic, or environmental drivers of the movements, migration and displacement also tend to contribute to reduced mental health through the gradual fragmentation of identity, belonging, and perceptions around one’s social value (Ayeb-Karlsson, Kniveton, and Cannon Citation2020; Morrice et al. Citation2021). Some scholars argue that post-migratory stressors pose the greatest mental health impacts (Schweitzer et al. Citation2011; Aragona et al. Citation2012), although most acknowledge that all phases contribute to the worsening of the mental wellbeing of migrants (Carswell, Blackburn, and Barker Citation2011; Rowley, Morant, and Katona Citation2020). During the resettlement phase migrants are often pushed into precarious living and working conditions that increase their exposure to injuries, crimes, exploitation, substance abuse and other social risks (Malm et al. Citation2020; Ayeb-Karlsson Citation2021).

In the UK, research indicates that a number of adversities inherent to the asylum-seeking process contribute to poor mental health, including feelings of isolation, the threat of removal from the place of resettlement, and concerns over asylum decisions (Rowley, Morant, and Katona Citation2020). In turn, personal agency, legal security, developing a sense of belonging, and social cohesion are key for refugees’ post-resettlement quality of life (Van der Boor, Dowrick, and White Citation2020). The hostile discourses about migrants in recent domestic politics and in the media are likely to obstruct this, negatively impacting the mental health of both asylum seekers and refugees. Reports of offshoring asylum seekers (BBC Citation2021; Syal and Badshah Citation2022) or relocating them in barracks (Taylor Citation2021), threats of violence (Murray Citation2020) and of jeopardised claims if they ‘misbehave’ (Townsend Citation2021), and associated feelings of rejection from the host population certainly add to the stresses, uncertainties, and adversities faced by people seeking asylum in the UK.

Over 135,000 refugees and 83,000 asylum seekers lived in the UK in mid-2021 (UNHCR Citation2022b). The city of Brighton and Hove is not currently a Home Office dispersal area for asylum seekers, but it has been part of various governmental resettlement schemes for years and has an established diaspora from Egypt, Sudan, Iran, Afghanistan and other countries from which people have had to flee persecution (Sanctuary on Sea Citation2022). The city however has insufficient designated accommodation for asylum seekers, and therefore most are dependent for accommodation and support on foster carers and members of their diaspora, and may seek to live in this city because of them (Brighton and Hove City Council Citation2017). In 2018, a Brighton and Hove City Council’s Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) estimated that 200 asylum seekers lived in the city at any one time, and most found accommodation via their personal networks (Condon, Hill, and Bryson Citation2018). The aim of the JSNA is to investigate health, social care and wellbeing needs of the local population to inform the commissioning and delivery of local services. This JSNA investigated international migrants’ needs within the city, including ASR. Recommendations included improving access to appropriate mental health services, but lacked clarity on ways to achieve this (Condon, Hill, and Bryson Citation2018), echoing the challenges reported by several other local governments across the country (e.g. Caldeldale Council Citation2016; Leicester City Council Citation2016; Cumbria City Council Citation2017; Welsh Government Citation2019).

As in the rest of the UK, refugees and asylum seekers with an active application or appeal living in Brighton and Hove are entitled to receive publicly funded healthcare through the National Health Service (NHS). The NHS offers support to ASR for a variety of mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, psychosis, and post-traumatic stress. However, as in the rest of the country, healthcare engagement among ASR in Brighton and Hove is significantly lower than that of the local population (Brighton and Hove City Council Citation2017; NHS England Citation2018). Immigration status is known to be one of the most important factors affecting both an individual's ability to seek out healthcare and their experiences when trying to access healthcare (Campbell et al. Citation2014). Individuals having fled persecution for instance are known to be fearful of seeking help and support from governmental officials, public authorities and health services due to traumatic experiences leading to their move or fear of being deported (Larchanché Citation2012). According to Fassil and Burnett (Citation2015), community organisations may be best placed to provide appropriate support tailored to the needs of ASR. However, little is known about the non-statutory support services that are available, who in particular offers them, where and when. This study responds to this call by exploring what exact mental health services are available to ASR in Brighton and Hove and what services are used and/or perceived as necessary. We aimed to understand whether current mental health support meets ASR needs, and to identify avenues for strengthening the available support. With this purpose we have explored the needs as perceived by asylum seekers, those who have gained refugee status in the past five years, and individuals who provide mental health care to ASR, and compared these to the existing services available. This research provides important insights into the mental health needs of ASR, highlights gaps in service provision, and informs strategies to strengthen existing mental health support services.

2. Methods

Data were collected between June and July 2018 after obtaining ethical approval from the Research Governance and Ethics Committee of the Brighton and Sussex Medical School (approval ER/BSMS9745/1).

Asylum seekers, refugees, and individuals providing them with mental health support (support workers) were recruited using a combination of purposive sampling and snowballing. The Clinical Director of Brighton Exile/Refugee Trauma Service (BERTS), a Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) offering free counselling and psychotherapy to refugees, asylum seekers and destitute migrants in Sussex, acted as initial gatekeeper. The Clinical Director was ideally placed to suggest appropriate institutions and initial key contacts, facilitating the initial recruitment of research participants. Recruitment was then expanded through snowballing by asking informants to suggest other suitable participants.

To recruit research participants, 16 publicly advertised organisations providing support to ASR were also approached via email and asked to display a recruitment poster and disseminate the research project information among ASR and support workers. ASR often lack access to internet and emails. Interviews with interested ASR were therefore organised by these organisations: ASR were contacted via their relevant organisations for telephone discussions with TA prior to meetings, and participant information sheets were given to them on first meeting. Support workers received participant information sheets via email, before interviews. For both groups, any questions were answered both prior to and on first meeting, and informed consent was sought prior to interview.

Due to the authors’ language limitations and lack of financial resources all recruitment materials were in English language only, as we were unable to interview individuals with very low English language proficiency. Inclusion criteria are described in .

Table 1. Participant inclusion criteria.

All data were collected via semi-structured interviews to allow researchers and participants to equally address issues of concern (Silverman Citation2009). A carefully prepared topic guide was developed by AT and MT to keep interviews on course and to probe relevant issues such as services provided and services used. The topic guide enabled participants to speak freely about experiences, thoughts, and feelings that were important to them (Denzin and Lincoln Citation1998). Face to face, semi-structured interviews were undertaken with both participant groups in a private room at the University of Brighton and at the Voices in Exile premises. Interviews were undertaken in English by TA and voice recorded with participants consent. ASR were asked to comment on their mental health needs, barriers to accessing support, and what they feel would help support their needs. Support workers were asked for their views on ASR’s mental health needs, on service provision strengths and challenges, barriers to accessing support, and what they felt was needed to better support ASR’s mental wellbeing.

All interviews were transcribed and anonymised by TA and shared with MT for analysis. NVivo was used as a coding tool and supported accurate, detailed, iterative coding into nodes, resulting in themes which were then categorised (Saldaña Citation2015). The thematic analysis allowed the exploration of barriers to accessing mental health support services, and contrasting ASR’s perceived mental health needs with how they are met by existing support services. We had planned to discontinue recruitment once data saturation had been clearly obtained. Eight support workers agreed to interviews and data saturation was reached after six. Thirteen ASR expressed interest in participating but only nine could be interviewed. Data saturation was not fully achieved after nine interviews, but due to time and financial constraints we were unable to recruit more ASR participants. Upon completion of data analysis, a 2-page lay summary of findings was emailed to participants when possible. This summary was also displayed within various organisations providing support services for ASR, and printed copies were made available to ASR and support workers via these organisations.

3. Results

Fifteen research participants were interviewed: nine ASR and six support workers. Seven (77.78%) ASR had achieved refugee status. Regarding support workers, two worked in primary care statutory services and four in non-statutory services. ASR were predominantly male (66.67%) with age range from 17 to 30. Their countries of origin were Afghanistan (44.5%), Syria (44.5%), and Sudan (11%). Support workers were predominantly female (83.33%) with a median time in role of three and a half years (range 1–9 years) ().

Table 2. Research informants.

Three main themes emerged from thematic analysis: ASR’s need for holistic mental health support, the disjunctive between perceived mental health support needs and the available support, and barriers to accessing existing support services. Across these themes, findings also illustrate the various ways in which the UK’s hostile environment towards migrants damages the mental health and wellbeing of both ASR and the individuals trying to support them.

3.1. ASR’s need for holistic mental health support

All interviewed workers emphasised the importance of supporting ASR mental health. In their experience, those turning to them for support were commonly diagnosed with post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and psychosis, and also suffered from sleep or eating disorders, poor concentration, and memory problems. Mental health problems often manifested as physical symptoms, such as digestive problems and backache, which could be difficult to diagnose and manage. All respondents agreed that combined pre-migratory (experiences in their home country), migratory (experiences during their journey), and post-migratory experiences (once in the UK) negatively impacted upon ASR mental health and wellbeing. As put by an 18-year-old asylum seeker called Mohammadi: ‘Everything in my life worries me’. Sarah emphatically described how the multiple uncertainties caused by post-migratory experiences are only one part of the traumatic experiences encountered by ASR:

There’s a whole other world of pain once people actually get here … frustration, anxiety, being forced to live in limbo, not knowing what’s going to happen, being angry at the way they’re treated by the Home Office and other agencies, not being believed, not being able to get help … depression as a result of not being able to use skills, not being able to train, not being able to learn, not being able to work, not having the money to do anything, sitting around in the shitty Home Office accommodation all day … not being able to eat properly … That’s got to drive you crazy! and it does! It’s heart-breaking to watch … and very often that’s on top of all of the original [pre-migration] stuff and then I think there’s an expectation from people who go through the asylum process that at the point they’re granted status everything will be ok and it isn’t … Just at the moment when you might expect to be celebrating you’re suddenly chucked out of your NASS [The National Asylum Support Service] accommodation, chucked off asylum support and not allowed any money … left alone to manage your own money … You’re suddenly expected to go and sign on at the job centre, sort your own council housing out … It’s a nightmare that whole transitional period.. You’ve got 28 days, and then I’d say anywhere between a year and two years after being granted status, sometimes less.. sometimes longer but.. what I’ve noticed with a lot of people is that they then wonder why they’re not happy and guilt starts to kick in because they’ve survived and their family didn’t and all that stuff that they’ve been containing in order to survive because they couldn’t afford to fall apart while they were still precarious suddenly starts leaking out and people don’t understand why … and they feel like they should be getting jobs and this and that, and they actually just fall to pieces and there is a real spike in sort of mental health needs at about that point. [Sarah, non-statutory worker]

Yasmin also explained the health-damaging effects of the UK’s intense asylum screening process:

What happened back home and in the journey is horrible and is where trauma and the PTSD come from, but what makes them [asylum seekers] more anxious and what makes them want to finish with their life is coming here where they thought they’re going to have a place and they’re going to find safety and people are going to care about them and going to look after them and [instead] they find this system that they don’t understand and they have to be in interviews that last for hours … being questioned.. even children being questioned for hours, when you feel the person who is questioning you is in uniform and is just trying to find you’re a liar, and having all these experiences and having to disclose them to someone you can truly say is not believing what you say. This is what makes them think this isn’t worth it, living isn’t worth it anymore. [Yasmin, non-statutory worker]

Michael emphatically explained how these long waits trigger feelings of stress and anxiety among asylum seekers, especially among those fearing that a rejected claim would put their lives at risk:

There are asylum seekers who feel they’re on death row.. because if they are put on a plane, they’ll have a plane journey, will disembark, go through passport control, somebody will look at their passport … make a phone call … and they’ll be taken to a place of execution. This isn’t paranoia or wild imagination. That’s happened, it’s what happened to members of some of my families [clients] when they were sent back to where they came from (…). I know people who’s been waiting for a [Home Office] decision about leave to remain for 11 years and every day they either want that envelope to come through that letterbox or they don’t … It’s either going to say here are your papers or here’s your plane ticket … It’s just such a long time to live in limbo for! It’s disgraceful and it’s torture … It’s not surprising that they’ve got mental health problems, it’s not surprising they’re anxious, that they run when they see the policeman … It could be their last day here, it could be the last few days that they’re alive … I don’t know how much people understand what goes on … . [Michael, statutory worker]

While all support workers agreed that ASR need specialised mental health support, five (83.33%) felt that referring people to general support services which often lack specialist understanding about their situations could be detrimental to their wellbeing. In particular, support workers emphasised that the mental health needs of ASR are complex and multidimensional and cannot be effectively addressed via generic mental health provisions that overlook broader triggers of mental ill-health:

With the levels of trauma and the complex issues that they face … not just about their mental health … about this whole system which is almost against refugees … It’s so complex that you have to have an in-depth understanding of post-traumatic stress, their journeys, the refugee situation as well as legal matters and stuff like that … it [requires] really specialist knowledge and not a lot of services hold that within their teams … this isn’t something that you can just refer into generic services, it has to be somebody who’s a professional in that. (Rachael, non-statutory worker)

This [ASR mental health needs] is a big issue for us but we are not mental health professionals … so we try … We try to refer as carefully as we can. We no longer simply signpost people to services that may or may not be appropriate … I’ve been trying to figure out [who does what] … trying to meet up with key agencies, statutory and non-statutory to see who does what and what their approach is, what their resources are … whether they have interpreters, whether they are up to speed on the practical issues that are important for asylum seekers and refugees … . (Sarah, non-statutory worker)

There’s a Syrian family I’m working with now … she lost her eight year old when his school was bombed, and later on she was pregnant and was running because a bomb went off … and she had a miscarriage … something went wrong and she lost the baby at eight months … Over here [the UK] she, her husband and her daughter who’s nine now they’ve one bedroom which they share, the daughter has to do her homework on a suitcase perched on the bed so I’m trying to get the housing people to give them somewhere nice to live. The housing people say they haven’t got anywhere but I contact anybody and everybody … . (Michael, statutory worker)

3.2. The disjunctive between perceived mental health support needs and the available support

Primary mental health care in Brighton and Hove is offered through the city’s Wellbeing Service, whilst second and tertiary care is offered through specialist services. ASR living in Brighton and Hove can also access mental health support offered by NGOs. Some NGOs are specifically targeting ASR and focus on their specific needs. For example, BERTS, formerly known as the Sanctuary Project, offers free specialist trauma counselling and psychotherapy to asylum seekers, refugees, and destitute migrants. BERTS is the only non-statutory organisation offering professional mental health support to ASR, while all other community organisations offer non-professional support, spanning a range of support groups and services across the city. In 2017 the Brighton and Hove City Council and the NGO Sanctuary on Sea issued a listing of support services available to migrants in the city, updated in 2022 (see Brighton and Hove and Sanctuary on Sea Citation2022). Written entirely in English language only, this list is not specific to the needs of ASR, and offers details for over 100 different organisations. Clear information on the specific services offered to ASR by particular organisations is lacking, which adds to the traumas of ASR and limits support workers’ ability to support them.

Nineteen local organisations offering statutory and non-statutory services that help support ASR’s mental health and wellbeing were identified by research participants. Not all services were free, nor specifically aimed at supporting mental health, nor specifically for ASR ().

Table 3. Support services available, recommended, and used by informants.

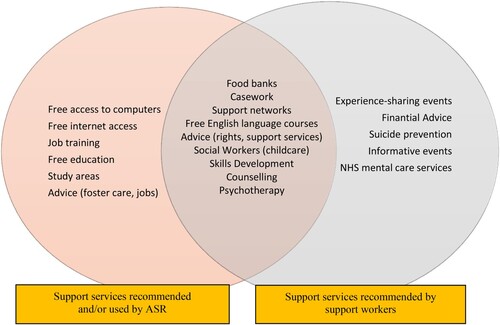

Interestingly, support worker recommendations were not always used by ASR and, conversely, some of the forms of mental wellbeing support described as helpful by ASR were not mentioned by support workers. illustrates the disjunctive between the services recommended and accessed by the different participants.

Although all ASR accessed at least one service, the majority (88.88%) were still struggling with unpleasant feelings. ASR suggested various types of services that they felt would support their mental health. Activities extended beyond formal mental health support, including particularly services focused on preventing feelings of isolation, such as networking events, and those that addressed their need to learn and improve English language and other skills needed for them to build their new lives in the UK:

A better way to support people is to help with knowledge, they [ASR] aren’t good in English language, not good in maths … they go to school or college and they fail and then the next year they don’t want to continue … it’s better to support more in the knowledge. (Abed, 17-year-old refugee)

We [my husband and I] are lonely all the time … my little daughter doesn’t speak [English] because we don’t see any people. (Aisha, 22-year-old refugee)

I think if they make like a meeting … like meeting new family and all together here, like party or something so people know [each other] and children play together … is good to know people … . (Tahir, 25-year-old refugee)

Support workers also reflected on service provision gaps, and mentioned additional services needed to better support the mental health needs of ASR. For instance, two support workers felt that if all service providers understood ASR’s complex situations and their mental health needs, they would have the ability to identify when extra support is required and refer onto appropriate specialist services. They also mentioned the need for interpreters. However, they also admitted that some existing services were not supportive of developing specialist [ASR] knowledge due to cost, additional work, and lack of requirement from the UK government. Support workers described effective mental health support for ASR as requiring a multifaceted and holistic approach requiring multidisciplinary collaborations across organisations, although admitted that previous efforts had been obstructed by services that had closed, moved, or were underfunded.

Most support workers (83.33%) also raised concerns about the suitability of existing mental health support for ASR, with current services considered inadequate. In particular, they criticised that the Brighton and Hove statutory mental health service offers only six 60-min therapy sessions despite the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends eight to twelve 90-min trauma-focused sessions for individuals who have been exposed to one traumatic event, and extending beyond this for those who have multiple traumatic experiences. Interviewed support workers agreed that ASR need well beyond six sessions: ‘I’ve always been told to operate with the six-session model, which isn’t enough’ (Natalie, statutory worker).

Support workers also lamented that the current NHS counselling focus on psycho-education and learning effective techniques for improved management of everyday life difficulties fall short in supporting disempowered ASR who have lived multiple traumatic events that are beyond their control. For them, ASR’s mental ill-health struggles are more complex than the generic life difficulties (e.g. coping with a long-term condition, chronic pain, addictions, fertility problems) NHS counsellors are generally trained for.

3.3. Barriers to accessing existing mental health support

Whilst research participants highlighted that existing services did not fully meet the mental health needs of ASR, they also mentioned factors that impeded ASR access to existing services. The main barriers to access were the complex (often unclear) referral processes, communication difficulties, stigma and prejudice from ASR communities and some healthcare workers, the location of support services, and economic limitations that constrain service provision quality and rapidly change the support landscape.

3.3.1. Complex, unclear, and uncoordinated referral processes

ASR access mental health support through formal referral processes and informal signposting. Whilst access to statutory services relies on often lengthy referral procedures and pre-booked appointments, most non-statutory services work informally, through word of mouth, with ASR able to show up with no prior warning. Statutory and non-statutory support workers across Brighton and Hove receive and send daily referrals from multiple organisations and individuals. Interviewed support workers expressed their preference for simple referral processes found mainly among non-statutory services as they felt it helped timely mental health support. Informal ways of working can however make things difficult for them, and whilst some organisations work on a drop-in basis, other increasingly prefer a referral form to be completed in advance. The information on what services need a referral or accept drop-ins is however not clear and is rapidly changing, which causes confusion and feelings of frustration among support workers and ASR alike. Also, since no clear information exists on what organisations provide what support services accessible to ASR, support workers refer ASR to the organisations they know, whilst various other organisations offering support to ASR are not being used or known by ASR. In addition, since various of the well-known organisations offer the same services (e.g. social support, advice), referral duplicates are commonly used to try to accelerate support access. This, however, often causes support delays:

With the last referral we made the waiting list was quite lengthy, I can’t remember how long … I don’t think the last client that we referred eight weeks ago has managed to get through. (Sarah, non-statutory worker)

There’s less bureaucracy [between non-statutory services] … they [ASR] don’t have to go through as many systems and assessments.. cos we work together in an informal way … a very quick referral and a phone call and a kind of handover of information before it’s taken on which helps … . (Rachael, non-statutory worker)

I mainly [refer] to General Practitioners, but we also have support workers, the housing trust … anybody who works with asylum seekers and refugees like Voices in Exile … BMECP isn’t really working the way that it used to … who else … yeah just anybody who has contact with Black, Minority and Ethnic people ... secondary care of course to the Hove Polyclinic and East Brighton Hospital. (Michael, statutory worker)

3.3.2. Communication difficulties

Most information about the support services available to ASR was written only in English. All research participants admitted that their limited ability to speak other languages negatively affected ASR’s access to existing support services. Language limitations and the associated communication challenges were frequently mentioned as source of stress among both groups of participants. When possible, support workers employed face to face or telephone interpreters, but they admitted that the use of interpreters involved other complications, such as financial costs in the case of non-statutory services. Maria for instance confessed how she often felt that the only thing she could do to communicate with ASR was to ‘speak at a slower pace’.

Statutory and non-statutory support workers admitted that waiting for an interpreter often caused treatment and support delays. They also described how the use of interpreters had occasionally triggered difficult situations, especially due to differing political views between interpreters and ASR, or when the use of interpreters from local diaspora had compromised ASR's privacy and confidentiality. Five (55%) ASR confessed having had problems when using interpreters, often related to lack of mutual understanding due to linguistic variations and to inaccurate translations:

Sometimes because my language Arabic [is] different from country to country, I think sometimes they [interpreters] can’t understand me … Maybe I am better, I can understand them but they can’t understand me … I think a Syrian interpreter its better … . (Jaliyah, 27-year-old refugee)

3.3.3. Stigma, prejudice and mistrust

Although this was not mentioned by ASR, five (83.88%) support workers felt that access to mental health support was also negatively impacted on by stigma, in particular regarding beliefs around mental ill-health.

Mental health is hugely stigmatised … Certain communities stigmatise it more than others but it’s generally difficult to seek help, and depending on what it is that you’ve been through it might be difficult to say that in the first place because of shame … sexual violence in general for women but also for men … . (Sarah, non-statutory worker)

Mental health support access is also obstructed by prejudice from healthcare workers. Michael for instance described instances where asylum seekers were denied mental health support because they lacked leave to remain despite their legal entitlement to healthcare. Support workers highlighted that advocating for ASR rights and educating the public on these rights is vital for improving ASR’s access to statutory service provision. According to informants, this prejudice towards ASR is heavily influenced by negative portrayal of migrants in the media and by the current hostile political agendas:

There’s something to say about the general [public] perception which has unfortunately been made quite toxic by politicians … things around the NHS and [healthcare] access … who should and shouldn’t be allowed access to healthcare and mental health care … I think it would be good not just for refugees and asylum seekers but also [for] the local population to change this … people not to feel like they should be barriers or gatekeepers to the health system … there are often receptionists, doctors, people with their own personal opinions of whether refugees should be here or not and they then, their opinion impacts on people’s health seeking behaviour or what they get … they check passports at reception, things like that … . (Maria, non-statutory worker)

People feel silenced. They [ASR] don’t stand up because they fear being deported, and they think if they stand up and say what their issues are someone would hear them and they would get rejected from the country and would have to go home. (Rachael, non-statutory worker)

Together with the confusing referral process mentioned earlier, these situations reinforce ASR’s mistrust towards support services, which in turn constitutes an important barrier to mental health support access:

Sometimes even if I refer them and assure that they’re entitled to receive support they won’t go … they are scared … and what’s my agenda, and what would happen if they went, how would they [support workers] treat them … and would it count against them and their [asylum] applications if they went … . (Michael, statutory worker)

3.3.4. Service location and public transport affordability

In Brighton and Hove ASR frequently find accommodation through personal networks and are unable to choose where to live. Statutory support workers work within clearly defined geographical boundaries, whereas non-statutory services offering support to ASR are located within the city centre. The need to travel to services, such as to attend counselling sessions, English courses, or social networking events, was reported as a support access barrier by both participant groups. Young ASR like Isaad and Abed had a bus pass, which young Brighton and Hove residents can obtain for free, but older ASR had difficulties accessing support services because of unaffordable transport costs. For instance, Kaled, who was studying English at the University of Sussex, stopped because he could not afford to pay for the bus fares. Some foster carers and support workers try to cover travel costs, but this reduces service provision funding:

People are living on the edges of the city and often the services that they need are all the way on the other side … Fair enough, there are buses, but can they afford it? are they eligible for a bus pass? (Natalie, statutory worker).

We go [by bus] every one and a half month because we already take [have used our] benefit and we can’t pay … My daughter when she sees a bus she’s so happy and she wants to go up, we say not today, not today … . (Aisha, 22-year-old refugee)

We don’t have specific funding to pay those expenses [travel fares] but people make regular donations for client hardship and we use that where it would be a barrier otherwise. (Sarah, non-statutory worker)

3.3.5. Economic sustainability and support uncertainty

Mental health provision in the UK is underfunded, stretched, and unable to meet demands, which negatively impacts upon the specialist care available and its quality:

I don’t think the statutory services meet the need for any client group, they are under so much pressure … they’re at breaking point, just like the rest of the NHS and the rest of social care … But you can’t do a good job when your workload is excessive … How can you give the right time to that client? As good-willed and skilled as anyone can be it’s impossible to do your best when you’ve got too many clients on your books. (Rachael, non-statutory worker)

Facing service reductions and closures due to austerity measures in the UK, Michael reported his feelings that vulnerable ASR are ‘easy targets’ for government cuts:

The very bad news is that they are effectively shutting us down … I don’t know why, I haven’t been told anything, except that the service as a whole is oversubscribed and they need to prune people away … you know … the people I work with [ASR] don’t have a vote, they don’t complain, they don’t know what their rights are and they very often feel that if they speak up or raise objections that’ll be used to ship them back to where they came from so they’re an easy target. (Michael, statutory worker)

Non-statutory services rely mainly on donations and fundraising, with volunteers running their services. Such services are often short-lived, and various research participants mentioned services which no longer exist. Funding uncertainty negatively impacts on service provision, as well as on the quality of the services offered, to whom, and at what frequency. As Michael points out, it also negatively impacts on service provision in that the lack of sustainable funds for supporting the mental health needs of ASR not only causes damaging uncertainties regarding the available support but also obstructs coordinated action that is necessary for making the most of the available resources:

There are lots of organisations sort of offering services for them [ASR], the Sanctuary Project, Refugee Radio, the Centre for Developing Communities … and we get a kind of meeting to know everybody … there’s a kind of overarching body but it’s not coherent enough to pull the funds and resources and I think that’s really what’s needed. The City of Sanctuary should have been that, but the problem is that you need money … you need a lot of people full time, pulling [efforts] together and working together. (Michael, statutory worker)

4. Discussion

ASR have complex mental health needs associated with multiple levels of trauma from pre-migratory, migratory, and post-migratory experiences. They are at increased risk of mental health problems compared to the general population, and these often manifest as physical symptoms. Interviewed support workers however admit that these are difficult to diagnose and treat appropriately, mostly due to due to a general lack of knowledge about the underlying association with trauma among healthcare workers and to the scarce resources allocated to vulnerable migrant populations and to mental health more generally.

Post-migratory factors, including the uncertainties associated with a hostile and complex asylum-seeking process, social isolation, and housing issues detrimentally affect ASR’s physical and mental health. This was reported by all research participants, supporting UK and overseas literature (Carswell, Blackburn, and Barker Citation2011; Aragona et al. Citation2012; Morgan, Melluish, and Welham Citation2017; Dangmann et al. Citation2020; Pollard and Howard Citation2021). The longest wait for an asylum decision mentioned by informants was 11 years, significantly longer than the Home Office target of 6 months (UK Government Citation2022b). Precarious living conditions are a key post-migratory stressor, with asylum seekers often placed in undesirable, ‘hard to let’, or unwanted accommodation: a mental health-damaging practice also reported in various other contexts globally (WHO Citation2019). In line with our findings, existing literature indicates that asylum seekers’ mental wellbeing is interlinked with immigration policy, employment prospects, access to adequate support, healthcare, housing, economic assets, social support networks, and contact with relatives (Whittaker, Hardy, and Lewis Citation2005; Misra, Connolly, and Majeed Citation2006; Palmer and Ward Citation2007; Majumder et al. Citation2015; Collyer et al. Citation2017). There is no consensus on whether their mental health improves once refugee status is gained. Toar, O'Brien, and Fahey (Citation2009) found that in Ireland the mental health of asylum seekers improved once they had gained refugee status, but our research indicates that often mental health problems continue. A 2016 study with male refugees living in the UK found an increase in mental health needs after gaining asylum (Vitale and Ryde Citation2016). Our research indicates that sustainable funding for multifaceted support services is needed to prevent this. As shown, ASR mental health support needs extend beyond the standards models of care used within the NHS (Cox and Webb Citation2015; Morgan, Melluish, and Welham Citation2017). Ensuring timely application outcomes and relaxing hostile environment policies so that siblings and other close family members are not separated by housing officers will also help (Hafford Citation2010; Amnesty International, The Refugee Council, and Safe the Children Citation2019).

Extensive counselling sessions can help improve ASR wellbeing (Northwood et al. Citation2020). However, only six NHS sessions seem to be available to ASR living in Brighton and Hove. Reasons offered for reduced provision for ASR included service saturation, lack of funding, and staff shortages. Only one non-statutory organisation in Brighton and Hove, BERTS, provides professional mental health support, but had at the time of the research a long waiting list, leaving little options for professional, culturally sensitive, specific trauma-focussed mental health counselling available to ASR. Access to regular counselling sessions must be enabled, conducted by people trained on the particular struggles faced by this vulnerable group and independent from the general system of mental health support.

ASR have higher mental health needs compared to local populations but underutilise mental health services (Burnett and Peel Citation2001; NHS England Citation2018). Researchers attribute this underutilisation to many of the barriers to access identified in our study. Kiselev et al. (Citation2020) for instance found that the main obstacles to accessing mental health support encountered by Syrian ASR living in Switzerland included language issues and lack of interpreters, complex referral processes, underfunded services, stigma, and disparity in perceived needs between service providers and asylum seekers. Satinsky et al.’s (Citation2019) review on ASR mental health support needs in Europe highlighted similar issues, and research conducted in the USA shows that asylum seekers face similar barriers to accessing care, including cultural communication, logistics, and finance (Derr Citation2015; Gilmer Citation2018). Areas identified for further research and action in the existing literature include policy reform, upskilling existing services so they can identify mental health care needs, increase in funding for services, increase cultural awareness, and the development of specialist services (Kiselev et al. Citation2020; Satinsky et al. Citation2019; Derr Citation2015; Gilmer Citation2018; Pollard and Howard Citation2021). There are indeed important cross-context commonalities in the mental health support barriers experienced by ASR, and further research is needed to better understand how best to prevent and mitigate these.

Our research also exposes other important barriers that ASR face when trying to access existing support services, associated mainly with communication difficulties, housing location, stigma, ASR's mistrust towards support services, prejudice from statutory healthcare workers, poor service provision coordination, and the volatile economic assets of the services provided. Communication difficulties and issues associated with accessing appropriate independent professional interpretation are well-described in the healthcare literature (e.g. MacFarlane et al. Citation2020; Morrice et al. Citation2021). Our research findings suggest that employing refugees as support workers could help with this, but they should receive tailored confidentiality and professional ethics training. Mental health stigma resulting from cultural norms is also known to obstruct help-seeking behaviours (Kiselev et al. Citation2020), and structural violence and stigma are known to obstruct access to mental health support (Whittaker, Hardy, and Lewis Citation2005; Larchanché Citation2012). Interviewed support workers admitted that stigma related to cultural perceptions of mental health inhibited some ASR from seeking appropriate support. Perhaps more importantly, our research also indicates that statutory health workers had refused care to ASR despite their legal entitlement. The current hostile environment towards migrants in the UK politics and media plays an important role in this. Prejudice and other structural sigma issues towards ASR affecting access rights can be addressed through advocacy, education, and job training.

Clearer information on the support services available to ASR and the associated referral processes is also needed. Interviewed support workers struggled to identify services that they felt could be beneficial. They also feared signposting ASR to unfamiliar services in case of negative impact on their mental health. Despite having a directory of services, provision and referral processes are complex and rapidly changing, and this negatively affects the mental health of ASR. The development of an adequately funded, statutory, umbrella agency able to coordinate and channel all requests for support and available services may be the way forward.

5. Study limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. Qualitative researchers operate with small samples in order to achieve the in-depth case-oriented analysis fundamental to inductive inquiry. Our sample was large enough for no new themes to emerge among interviewed support workers, but data saturation was not clearly achieved with ASR. In addition, lack of financial resources and the authors’ language limitations restricted the study insights to those shared by individuals who were relatively fluent in English. None of the ASR who demonstrated an interest in participating in this research were excluded on language proficiency grounds, but it is possible that some ASR did not contact us because of this. We recognise that English language inclusion criteria may have limited some individuals from participating and may have impacted results.

We have interviewed predominantly young, male, middle-eastern ASR, mostly with refugee status, accessing support services provided in Brighton and Hove. The countries of origin of interviewed ASR reflect the main diasporas present in Brighton and Hove, and the most frequent countries of nationality for asylum applications in the UK. Findings in this study may however not align with the mental health support provision available in other areas of the UK. Brighton and Hove has a reputation of having a generally welcoming attitude to migrants, and of nurturing and looking after its population’s mental health. Although the city participates in various government resettlement schemes, it is not a Home Office dispersal town. The issues and pressures found by support workers and ASR may, therefore, differ from other UK contexts. It is not the aim of qualitative research to generalise findings beyond the study context and population. Instead, we stress how several participant quotes reflect and expand on what has been shown in qualitative studies with ASR in the UK, Europe, and other contexts, including issues related to communication difficulties and with accessing appropriate interpretation, and the health-damaging effects of the UK’s asylum screening process. Research results are based on research in Brighton and Hove, but commonalities with the UK and beyond have been found and described.

6. Conclusions

The wellbeing and mental health needs of ASR are complex and multifaceted. They face multiple levels of trauma relating to pre-migratory, migratory, and post-migratory stressors, which persists after they obtain the refugee status. Their mental wellbeing is negatively impacted upon by the hostile UK asylum process and associated precarious living conditions, unmet educational needs, poor employment opportunities, and feelings of stigma, immobility, uncertainty, and socio-economic isolation. There are, however, important gaps in mental health support for ASR living in the UK. Adequate support must holistically embrace ASR’s multifaceted and complex needs via specialised and sustainable interventions. Barriers in accessing existing mental health support include lengthy waiting times, location of services, language issues, fear and mistrust, insufficient and variable funding, and prejudice and unawareness of the entitlements of ASR by statutory healthcare receptionists. In addition, the provision is difficult to navigate. More resources need to be allocated to adequately support the health and wellbeing of this vulnerable group, and optimising the coordination and transparency of existing support services must follow. Further research will be required to design and develop appropriate mental health services, and to understand why some Brighton and Hove ASR were denied access to services despite having access rights and how often this happens. This article has proved the urgency and immediate need to turn around and start moving in a more positive direction, in light of the current more restrictive and hostile migrant narratives in the UK surrounding asylum seekers, refugees, and all people on the move.

Author's contributions

TA and MT conceptualised and designed the study; TA collected data and conducted preliminary analysis; MT supervised data collection and preliminary analysis. TA wrote the first draft with input from MT and SAK. MT conducted final data analysis with input from TA and SAK. MT rewrote the final manuscript and lead the revisions with input from all authors.

Acknowledgements

We thank all informants for taking the time to participate in this study making this research possible. We also thank Prof. Sally Munt from BERTS and Ms. Mel Steel from Voices in Exile for their assistance with the initial recruitment of research participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All relevant data are within the paper. Due to the nature of this research, further data will not be publicly shared.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 In this paper, the term asylum seeker refers to any person seeking asylum who has applied to become a refugee, and the term refugee is used to refer to an individual who has had a successful outcome on their asylum application. We are using the acronym ASR (Asylum Seekers and Refugees) to jointly refer to individuals seeking asylum, as defined above, and individuals whose claim for asylum was accepted and asylum was granted.

2 Women who are pregnant receive £3 extra a week, and those with a baby under the age of 1 receive £5 extra a week (UK Government Citation2022a).

References

- Amnesty International, The Refugee Council, and Safe the Children. 2019. Without My Family: The Impact of Family Separation on Child Refugees in the UK. London: Amnesty International UK, the Refugee Council and Save the Children.

- Aragona, M., D. Pucci, M. Mazzetti, and S. Geraci. 2012. “Post-migration Living Difficulties as a Significant Risk Factor for PTSD in Immigrants: A Primary Care Study.” Italian Journal of Public Health 9 (3): 67–74. doi:10.2427/7525.

- Ayeb-Karlsson, S. 2021. “‘When We Were Children We Had Dreams, Then We Came to Dhaka to Survive’: Urban Stories Connecting Loss of Wellbeing, Displacement and (Im)mobility.” Climate and Development 13 (4): 348–359. doi:10.1080/17565529.2020.1777078

- Ayeb-Karlsson, S., D. Kniveton, and T. Cannon. 2020. “Trapped in the Prison of the Mind: Notions of Climate-induced (Im)mobility Decision-making and Wellbeing from an Urban Informal Settlement in Bangladesh.” Palgrave Communication 6 (62): 1–15. doi:10.1057/s41599-020-0443-2.

- BBC. 2021. UK to Consider Sending Asylum Seekers Abroad. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-56439093.

- Brighton and Hove and Sanctuary on Sea. 2022. Local Resources: Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Migrants Directory. https://brighton-and-hove.cityofsanctuary.org/local-resources.

- Brighton and Hove City Council. 2017. Joint Strategic Needs Assessment. Vulnerable Migrants. http://www.bhconnected.org.uk/content/needs-assessments.

- Burnett, A., and M. Peel. 2001. “Health Needs of Asylum Seekers and Refugees.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 322 (7285): 544. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7285.544

- Calderdale Council. 2016. Joint Strategic Needs Assessment. Refugees and Asylum Seekers. https://www.calderdale.gov.uk/v2/residents/health-and-social-care/joint-strategic-needs-assessment/inequalities/refugees-and-asylum#item-3761-629.

- Campbell, R. M., A. G. Klei, B. D. Hodges, D. Fisman, and S. Kitto. 2014. “A Comparison of Health Access between Permanent Residents, Undocumented Immigrants and Refugee Claimants in Toronto, Canada.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 16 (1): 165–176. doi:10.1007/s10903-012-9740-1

- Carswell, K., P. Blackburn, and C. Barker. 2011. “The Relationship Between Trauma, Post-Migration Problems and the Psychological Well-Being of Refugees and Asylum Seekers.” International Journal of Social Psychiatry 57 (2): 107–119. doi:10.1177/0020764009105699

- Citizens Advice. 2022. After You Get Refugee Status. https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/immigration/asylum-and-refugees/after-you-get-refugee-status/.

- Collyer, M., R. Brown, L. Morrice, and L. Tip. 2017. “Putting Refugees at the Centre of Resettlement in the UK.” Forced Migration Review 54: 16–19. ISSN 1460-9819.

- Condon, R., A. Hill, and L. Bryson. 2018. International Migrants in Brighton and Hove. Brighton: Brighton and Hove City Council.

- Cox, N., and L. Webb. 2015. “Poles Apart: Does the Export of Mental Health Expertise from the Global North to the Global South Represent a Neutral Relocation of Knowledge and Practice?” Sociology of Health & Illness 37 (5): 683–697. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12230

- Crawley, H. 2010. Chance or Choice? Understanding Why Asylum Seekers Come to the UK. London: Refugee Council.

- Crawley, H., and J. Hagen-Zanker. 2019. “Deciding Where to Go: Policies, People and Perceptions Shaping Destination Preferences.” International Migration 57 (1): 20–35. doi:10.1111/imig.12537.

- Cumbria City Council. 2017. Refugees. Joint Strategic Needs Assessment. https://www.cumbriaobservatory.org.uk.

- Dangmann, C. R., Ø Solberg, A. K. Steffenak, S. Høye, and P. N. Andersen. 2020. “Health-related Quality of Life in Young Syrian Refugees Recently Resettled in Norway.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 48 (7): 688–698. doi:10.1177/1403494820929833

- Denzin, N., and Y. Lincoln. 1998. Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials. London: Sage.

- Derr, A. S. 2015. “Mental Health Service Use Among Immigrants in the United States: A Systematic Review.” Psychiatric Services 67 (3): 265–274. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201500004

- Dowling, A., M. Kunin, and G. Russell. 2020. “The Impact of Migration Upon the Perceived Health of Adult Refugees Resettling in Australia: A Phenomenological Study.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48(7): 1536–1553. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1771173.

- Fassil, Y., and A. Burnett. 2015. Commissioning Mental Health Services for Vulnerable Adult Migrants – Guidance for Commissioners. London: Mind.

- Gilmer, C. 2018. “Assessing Perceived Barriers to Healthcare Access for Resettled Refugees in the Western United States.” Thesis and Dissertations, Harvard University. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37945656.

- Hafford, C. 2010. “Sibling Caretaking in Immigrant Families: Understanding Cultural Practices to Inform Child Welfare Practice and Evaluation.” Evaluation and Program Planning 33 (3): 294–302. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.05.003

- Home Office. 2022. Immigration Statistics, Year Ending December 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/immigration-statistics-year-ending-december-2021/summary-of-latest-statistics.

- Kirmayer, L. J., M. Munoz, M. Rashid, A. G. Ryder, J. Guzder, C. Rousseau, and K. Pottie. 2011. “Common Mental Health Problems in Immigrants and Refugees: General Approach in Primary Care.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 183 (12): 959–967. doi:10.1503/cmaj.090292

- Kiselev, N., M. Pfaltz, F. Hass, M. Schick, M. Kappen, and M. Sijbrandij. 2020. “Structural and Socio-cultural Barriers to Accessing Mental Healthcare Among Syrian Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Switzerland.” European Journal of Psychotraumatology 11 (1): 1717825. doi:10.1080/20008198.2020.1717825

- Larchanché, S. 2012. “Intangible Obstacles: Health Implications of Stigmatization, Structural Violence, and Fear among Undocumented Immigrants in France.” Social Science & Medicine 74 (6): 858–863. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.016

- Leicester City Council. 2016. Rapid Health Needs Assessment: The Health Care Needs of Asylum Seekers in Leicester. https://www.leicester.gov.uk/public-health/jsnals.

- MacFarlane, A., S. Huschke, K. Pottie, F. R. Hauck, K. Griswold, and M. F. Harris. 2020. “Barriers to the Use of Trained Interpreters in Consultations with Refugees in Four Resettlement Countries: A Qualitative Analysis using Normalisation Process Theory.” BMC Family Practice 21 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1186/s12875-019-1070-0

- Majumder, P., M. O'Reilly, K. Karim, and P. Vostanis. 2015. “This Doctor, I Not Trust Him, I'm Not Safe': The Perceptions of Mental Health and Services by Unaccompanied Refugee Adolescents.” International Journal Social Psychiatry 61 (2): 129–136. doi:10.1177/0020764014537236

- Malm, A., P. Tinghög, J. Narusyte, and F. Saboonchi. 2020. “The Refugee Post-Migration Stress Scale (RPMS) – Development and Validation among Refugees from Syria Recently Resettled in Sweden.” Conflict and Health 14 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1186/s13031-019-0246-5

- Misra, T., A. M. Connolly, N. Klynman, and A. Majeed. 2006. “Addressing Mental Health Needs of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in a London Borough: Epidemiological and User Perspectives.” Primary Health Care Research & Development 7 (3): 249–256. doi:10.1191/1463423606pc294oa.

- Morgan, G., S. Melluish, and A. Welham. 2017. “Exploring the Relationship Between Postmigratory Stressors and Mental Health for Asylum Seekers and Refused Asylum Seekers in the UK.” Transcultural Psychiatry 54 (5–6): 653–674. doi:10.1177/1363461517737188

- Morrice, L., L. K. Tipp, M. Collyer, and R. Brown. 2021. “‘You Can’t Have a Good Integration When You Don’t Have a Good Communication’: English Language Learning among Resettled Refugees in the UK.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (1): 681–699. doi:10.1093/jrs/fez023

- Murray, J. 2020. Folkestone Charities Fear Far Right Will Target Asylum Seeker Base. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/sep/21/folkestone-charities-fear-far-right-will-target-asylum-seeker-base.

- NHS England. 2018. Improving access for All: reducing Inequalities in Access to General Practice Services: A Resource for General Practice Providers and Commissioners. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/inequalities-resource-sep-2018.pdf.

- Northwood, A. K., M. M. Vukovich, A. Beckman, J. P. Walter, N. Josiah, L. Hudak, K. O’Donnell Burrows, J. P. Letts, and C. C. Danner. 2020. “Intensive Psychotherapy and Case Management for Karen Refugees with Major Depression in Primary Care: A Pragmatic Randomized Control Trial.” BMC Family Practice 21 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1186/s12875-020-1090-9

- Palmer, D., and K. Ward. 2007. “Lost: Listening to the Voices and Mental Health Needs of Forced Migrants in London.” Medicine, Conflict and Survival 23 (3): 198–212. doi:10.1080/13623690701417345

- Pollard, T., and N. Howard. 2021. “Mental Healthcare for Asylum-Seekers and Refugees Residing in the United Kingdom: A Scoping Review of Policies, Barriers, and Enablers.” International Journal of Mental Health Systems 15: 60. doi:10.1186/s13033-021-00473-z

- Rowley, L., N. Morant, and C. Katona. 2020. “Refugees Who Have Experienced Extreme Cruelty: A Qualitative Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing After Being Granted Leave to Remain in the UK.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 18 (4): 357–374. doi:10.1080/15562948.2019.1677974

- Saldaña, J. 2015. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: Sage.

- Sanctuary on Sea. 2022. What Makes Brighton and Hove a City of Sanctuary? https://brighton-and-hove.cityofsanctuary.org/2015/06/10/what-makes-brighton-hove-a-city-of-sanctuary.

- Satinsky, E., D. C. Fuhr, A. Woodward, E. Sondorp, and B. Roberts. 2019. “Mental Health Care Utilisation and Access among Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Europe: A Systematic Review.” Health Policy 123 (9): 851–863. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.02.007

- Schweitzer, R. D., M. Brough, L. Vromans, and M. Asic-Kobe. 2011. “Mental Health of Newly Arrived Burmese Refugees in Australia: Contributions of Pre-migration and Post-Migration Experience.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 45 (4): 299–307. doi:10.3109/00048674.2010.543412

- Silverman, D. 2009. Doing Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

- Syal, R., and N. Badshah. 2022. UK to Send Asylum Seekers to Rwanda for Processing. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/apr/13/priti-patel-finalises-plan-to-send-asylum-seekers-to-rwanda.

- Taylor, D. 2021. Calls to Close Napier Barracks after Asylum Seekers Win Legal Case. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/jun/03/napier-barracks-asylum-seekers-win-legal-challenge-against-government.

- Toar, M., K. K. O'Brien, and T. Fahey. 2009. “Comparison of Self-Reported Health & Healthcare Utilisation Between Asylum Seekers and Refugees: An Observational Study.” BMC Public Health 30 (9): 214. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-214

- Townsend, M. 2021. UK Asylum Seekers told Claims at Risk If They ‘Misbehave’. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/jan/23/uk-asylum-seekers-told-claims-at-risk-if-they-misbehave?fbclid=IwAR0LSa5UgUiGPQxdO8NDHrRNcfu4FQJU1Hfw8GADuxInsPSNTXoXYp7yOv8.

- UK Government. 2022a. Asylum Support. https://www.gov.uk/asylum-support/what-youll-get.

- UK Government. 2022b. Claim Asylum in the UK. https://www.gov.uk/claim-asylum/screening.

- UNHCR. 2022a. Figures at a Glance. https://www.unhcr.org/uk/figures-at-a-glance.html.

- UNHCR. 2022b. Asylum in the UK. https://www.unhcr.org/uk/asylum-in-the-uk.html.

- Van der Boor, C. F., C. Dowrick, and R. G. White. 2020. “‘Good Life is First of All Security, Not to Live in Fear’: A Qualitative Exploration of Female Refugees’ Quality of Life in the United Kingdom.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (3): 710–731. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1852074.

- Vitale, A., and J. Ryde. 2016. “Promoting Male Refugees’ Mental Health After They Have Been Granted Leave to Remain (Refugee Status).” International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 18 (2): 106–125. doi:10.1080/14623730.2016.1167102

- Welsh Government. 2019. Refugee and Asylum Seeker Plan. https://gov.wales/refugee-and-asylum-seeker-plan-nation-sanctuary.

- Whittaker, S., G. Hardy, and K. Lewis. 2005. “An Exploration of Psychological Well-Being with Young Somali Refugee and Asylum-seeker Women.” Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry 10 (2): 177–196. doi:10.1177/1359104505051210

- WHO. 2019. Health Diplomacy: Spotlight on Refugees and Migrants. Copenhagen: WHO Europe.