ABSTRACT

Previous research concerned with the reactions of ethnic majority members to becoming a minority has often portrayed these responses as being polarised. On the one side, there is a group which supports ethnic diversity, on the other side, a group which rejects ethnic diversity. But our data shows that the reactions to ethnic diversity are more nuanced. This research has developed an empirically grounded typology of reaction patterns to being an ethnic minority through a k-means cluster analysis. When operationalised as appreciation of ethnic diversity and inter-ethnic contact, five distinct reactions emerged in the sample: (i) segregated sceptics (low appreciation of diversity with little inter-ethnic contact), (ii) integrated enthusiasts (high appreciation of diversity with a lot of inter-ethnic contact), (iii) integrated sceptics (low appreciation of diversity with a lot of interethnic contact), (iv) moderates (moderate appreciation and moderate inter-ethnic contact) and (v) segregated enthusiasts (high appreciation of diversity with little inter-ethnic contact). This article further explains why some people without a migration background are more open towards embracing majority-minority developments than others by scrutinising the role of socio-economic status, previous exposure to diversity and feeling like a minority.

Introduction

International migration has changed the socio-demographic make-up of larger Western European cities to a significant degree. In many of these cities, the former ethnic majority has become a minority, numerically speaking. This so-called majority-minority context, whereby the national ethnic majority is a minority at the local level (e.g. Craig, Rucker, and Richeson Citation2018; Outten et al. Citation2012) is no longer limited to highly-segregated neighbourhoods but is nowadays found across entire cities and federal states. For example, in Amsterdam, Malmö and Vienna, 54%Footnote1 of the population has a migration background. When we look at the generation of children aged 15 years and younger, these numbers increase to two-thirds, suggesting that this will be a lasting phenomenon. This development can be interpreted as one of the most significant metropolitan transformations of our time (Crul and Lelie Citation2019). As Fiske et al. (Citation2016) argue, it is important to investigate what this shift in numerical power effectively does to individuals living in ethnically diverse contexts. With this article I contribute to the study of changes in social hierarchies and explore the former majority’s responses to the hierarchy upheavals that majority-minority contexts entail (cf. Introduction, this issue). It is crucial to understand this, as learning about the effects of the demographic changes confronting today’s societies will help us to reduce intergroup conflict (Fiske et al. Citation2016, 46).

In their article White Americans, the New Minority?, Warren and Twine (Citation1997) opened the discussion on Whites becoming another minority in the United States as far back as the 1990s. Since then, several experiments have been conducted by a number of researchers in order to gain an understanding of the attitudes of White people to becoming a numerical minority. These experiments predominantly examine the majority’s reactions to anticipated demographic changes in the United States, in particular, the prospect of White people becoming a minority at the national level (Craig and Richeson Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Danbold and Huo Citation2015; Outten et al. Citation2012). These experiments provide a fundamental first indication of possible reactions to becoming a minority in line with group threat theory (Blalock Citation1967; Blumer Citation1999), which predicts the larger the out-group, the larger the perceived threat. Based on these experiments (Craig and Richeson Citation2014b), the authors conclude that ‘rather than ushering in a more tolerant future, the increasing diversity of the nation may actually yield more intergroup hostility’ (758). As Mepschen (Citation2016) shows in his study of a majority-minority neighbourhood in Amsterdam, for some people without a migration background increasing ethnic diversity goes hand-in-hand with an unwanted social transformation. Ethnic diversity can be perceived as something undesirable, leading to feelings of displacement and decreased belonging (Mepschen Citation2016). This social transformation causes some people to regard ‘native cultures as threatened entities that must be protected against the allegedly deviant mores and moralities of minoritized and racialized outsiders’ (Mepschen Citation2019; 73 and cf. Alba and Duyvendak Citation2019).

In strong contrast, findings of research at the neighbourhood level on members of the former ethnic majority living in ethnically diverse neighbourhoods show that reactions to living in such contexts are not always negative but can also play out in positive ways. Often, the inhabitants of ethnically diverse areas perceive the ethnic diversity in their neighbourhood as something to be appreciated or considered as ‘normal’ (e.g. Wessendorf Citation2013, Citation2014b) and attitudes towards this situation are generally found to be optimistic (Wessendorf Citation2014c). Over time, the normalisation of diversity can play a key role in producing more positive reactions to increasing ethnic diversity (Coenders and Scheepers Citation2008; Kaufmann and Harris Citation2015; Oosterlynck et al. Citation2017).

These diverging results ask for a deeper understanding of the reactions of inhabitants without a migration backgroundFootnote2 to being a minority in majority-minority contexts. The discussion around increasing ethnic diversity is often portrayed as being polarised. On the one side, there is a group which supports ethnic diversity, on the other side, a group which rejects diversity. The discussion of this two-dimensional polarisation is also reflected in academic discourses. Theories tend to lean towards either pessimistic (Craig and Richeson Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Danbold and Huo Citation2015; Outten et al. Citation2012) or optimistic (Wessendorf Citation2013, Citation2014b, Citation2014c) reactions towards ethnic diversity. In addition, as already pointed out in the Introduction by Crul et al. (Citation2023), existing frameworks usually do not make any differentiation between attitude and practice of people without a migration background despite the fact that both impact the social world around them in which they live together with people with a migration background. Furthermore, the emphasis is often placed on increasing ethnic diversity and the way in which socio-demographic change is adding to the anxiety of people without a migration background.

In alignment with Crul et al. (Citation2023), I argue that limiting focus to either positive or negative reactions to ethnic diversity is too simplistic an approach, one that ignores more ambivalent positions in which attitudes and practices do not align. As will be shown in the empirical part of this article, sizeable groups of people occupy these more ambivalent positions and despite feeling like a minority in their neighbourhood, some people still appreciate ethnic diversity. I will describe these more nuanced positions in the following paragraph.

The integration matrix: attitudes and behaviour toward being an ethnic minority

A large stream of literature identifies discrepancies between attitudes and behaviour in a variety of fields, such as environmental studies (Barr Citation2004), computer and privacy studies (Kokolakis Citation2017) and consumer studies (Moraes, Carrigan, and Szmigin Citation2012). In migration studies in particular, Blokland and van Eijk (Citation2010) find that people who have a preference for a diverse neighbourhood do not translate this attitude into practices as they do not have increased inter-ethnic contact. Using social network data collected in a highly diverse neighbourhood in the Dutch city of Rotterdam, Blokland and van Eijk (Citation2010) show that people without a migration background have fairly homogeneous networks in their neighbourhood consisting of people from the same ethnic background, even if one of their reasons for moving to that neighbourhood was a pronounced appreciation of its diversity. Further, Blokland and van Eijk empirically tested whether a desire for diversity manifests itself outside the neighbourhood, for instance, by developing inter-ethnic ties in the workspace, sport associations or other social organisations. Once more, they were unable to substantiate this claim, as regardless of whether or not their respondents said that they ‘like’ ethnic diversity, the social networks of people without a migration background are rather homogeneous, both inside and outside the neighbourhood. Hence, Blokland and van Eijk conclude that ‘a desire for diversity does not affect the likelihood of having network diversity, in the neighbourhood or elsewhere’ (Citation2010, 326).

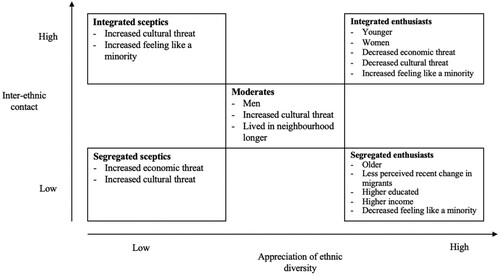

Blokland and van Eijk’s (Citation2010) study shows that it is vital to disentangle both dimensions and to approach reactions to being a numerical ethnic minority in a nuanced manner. One such approach, which takes the attitude-behaviour inconsistency into account is offered by Crul and Lelie’s (Citation2019) Integration Matrix. The Integration Matrix provides a theoretical approach to illustrate reactions to being a numerical ethnic minority in a systematic manner and distinguishes reactions to being a numerical ethnic minority on two dimensions: attitude and behaviour. In their taxonomy, Crul and Lelie make a distinction between accepting and rejecting attitudes towards ethnic diversity and integrated and segregated behaviour in ethnically diverse environments. More specifically, integrated/segregated behaviour refers to the amount of inter-ethnic contact had by people without a migration background. Accordingly, reactions can play out in four ways ().

Figure 1. Integration Matrix (Crul and Lelie Citation2019): potential types of responses of people without a migration background to being a minority in majority-minority contexts.

Crul and Lelie (Citation2017) outline the quadrants in the following way. Quadrant A, living in a segregated way and rejecting diversity, refers to people without a migration background who have comparably little inter-ethnic contact in majority-minority contexts and draw sharp symbolic boundaries between themselves and people with a migration background. On the other hand, it is possible that members of the former majority live in an integrated way, i.e. they have many inter-ethnic contacts and positive feelings towards the ethnically diverse situation they find themselves living in (C). In this instance, people without a migration background display an optimistic attitude towards increased ethnic diversity and support this attitude by behaving accordingly. It is also possible that a person’s attitude towards ethnic diversity does not correspond to their behaviour. Quadrant B describes former majority members who live in majority-minority contexts and have a great deal of contact with migrants but pessimistic attitudes towards ethnic diversity. Quadrant D describes the opposite of quadrant B – people without a migration background who are conceptually in favour of ethnic diversity but do not reflect this in their behaviour as they do not have much, if any, inter-ethnic contact.

Whereas Crul and Lelie’s (Citation2017) theory is designed in general terms without specifying the level of analysis (neighbourhood, city or national level), this study focuses on exploring reactions towards being a minority in actual majority-minority contexts, which is the case in many European cities at the neighbourhood level. Accordingly, I define attitude as the attitude towards the ethnic diversity in the neighbourhood in which people without a migration background are living. Behaviour is consequently understood as how much inter-ethnic contact people without a migration background have in this same neighbourhood.

Explaining attitudes and behaviour towards ethnic diversity

Whereas previous studies have investigated different types of reactions to becoming a numerical ethnic minority (e.g. Craig and Richeson Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Outten et al. Citation2012), these studies neglect to examine the characteristics that explain these reactions. Yet, if we want to develop a thorough understanding of the effects of global migration, it is crucial to understand why some people without a migration background react differently to being a numerical ethnic minority than others. The existing literature allows us to infer what determinants generally influence attitudes and behaviour regarding ethnic diversity of people without a migration background. In the coming sections I will focus on these determinants and discuss three sets of predictors of attitudes towards ethnic diversity and inter-ethnic contact: socio-economic status, exposure to diversity and feeling like a minority.

Socio-economic status

Socio-economic status, understood here as the level of income and education, has been extensively researched in relation to attitudes and behaviour towards increasing ethnic diversity. People in lower income strata are usually found to have more pessimistic attitudes towards ethnic diversity since they may perceive people with a migration background as a threat over resources (e.g. Zick, Küpper, and Hövermann Citation2011). At the same time, lower income White people do not necessarily live in homogeneous families and communities (Beider, Harwood, and Chahal Citation2017). Due to their economically weaker position, lower income individuals without a migration background have contact with more people with a migration background in the neighbourhood as their structural meeting opportunities are higher (for instance, they might share common interests in leisure time activities (Blau Citation1960; Bourdieu Citation1984)). At the same time, people without a migration background who have a relatively higher income are less exposed to ethnic diversity (Boterman and Musterd Citation2016).

Apart from economic position, the level of education has been shown to influence both attitudes towards diversity and inter-ethnic contact. A higher level of education is related to greater ethnic tolerance and more optimistic attitudes towards issues related to ethnic diversity. In fact, the effect of education is a highly consistent finding (Breugelmans and van de Vijver Citation2004; Citrin et al. Citation1997; Coenders and Scheepers Citation1998; Hainmueller and Hiscox Citation2010; Scheepers, Felling, and Peters Citation1989; van der Waal et al. Citation2010). At the same time, studies show that the higher the level of education, the less inter-ethnic contact people without a migration background have (Martinović Citation2013). The higher educated tend to live more segregated lives than the lower educated in ethnically diverse neighbourhoods (Blokland and van Eijk Citation2010) as they might have fewer structural opportunities to meet (Blau Citation1977).

H1: The higher the socio-economic position, the more positive the attitudes towards ethnic diversity and the lower the amount of inter-ethnic contact.

Exposure to diversity

Previous research in ethnically diverse contexts has shown that ethnic diversity can become the norm and is not constantly perceived as threatening after a period of acclimatisation. For instance, the concept of commonplace diversity (Wessendorf Citation2013, Citation2014b) refers to cultural diversity being perceived as ordinary by inhabitants of ethnically diverse neighbourhoods. Ethnic diversity is, so to speak, a normal part of everyday social life. Wessendorf (Citation2013) finds that one way of enacting the notion of commonplace diversity is acting with ‘civility towards diversity’, that is ‘while diversity is acknowledged and sometimes talked about, actual engagement with difference remains limited and people rarely explore cultural differences more deeply’ (Wessendorf Citation2014a, 394).

The concept of commonplace diversity is no recent phenomenon and has its roots in the works of Simmel (Citation1950). Simmel argued that constant exposure to overstimulation results in an indifference to this stimulation (blasé attitude). Commonplace diversity may therefore be a psychological coping mechanism, required to manage the ‘diversities’ of everyday city life. This mechanism might make it easier for people without a migration background to form inter-ethnic contact and hold more positive attitudes towards diversity as they have ‘got used to’ ethnic diversity over time.

In this way, diverse settings can become the norm and are no longer constantly perceived as threatening after a period of acclimatisation. This argument is also supported by Oosterlynck et al.’s (Citation2017) empirical work. They show that long-term residents of neighbourhoods who witnessed a large influx of foreigners were pessimistic about this at first. These negative feelings, however, evened out for most inhabitants over the course of time as they became acquainted with the new situation. Hence, people who have lived in diverse neighbourhoods or in the city for longer might be more likely to hold rather positive attitudes towards ethnic diversity and have comparably more inter-ethnic contact.

H2: The longer residents have lived in ethnically diverse contexts the more positive their attitudes towards ethnic diversity and the more inter-ethnic contact they have.

Feeling like a minority – irrespective of numerical facts

To date, numerous experiments have been conducted to gain an understanding of the attitudes of White people to becoming a numerical minority in the United States. These experiments show, for instance, that White Americans who generally do not show any political preference, tend to favour the Republican Party and express greater political conservatism after being confronted with the prospect of becoming a numerical minority in the future (Craig and Richeson Citation2014a). Furthermore, after being exposed to majority-minority shifts, White Americans support more conservative policies (Craig and Richeson Citation2014a); tend to show greater support for assimilation practices and lower endorsement of diversity in general (Danbold and Huo Citation2015); and display increased feelings of anger and fear directed towards minorities (Outten et al. Citation2012). Demographic shifts can also impact inter-ethnic relations. Craig and Richeson (Citation2014b) find that becoming a minority may evoke greater explicit and implicit racial bias and their respondents indicate a preference for interacting with their own ethnic group.

As mentioned earlier, these experiments effectively describe theoretical mechanisms of group threat theory (Blalock Citation1967; Blumer Citation1999), which proclaims the larger the out-group, the larger the perceived threat. Often, people estimate the relative power of a group based on its numerical size. In majority-minority contexts, the group size of people without a migration background is decreasing, which could promote the feeling that the in-group’s power in general is under threat. Priming respondents with a decrease in their group-size leads to more antagonistic attitudes.

In his book White Nation (2000), Hage explores how multiculturalism is experienced within the dominant White culture in Australia. Whereas Hage is not predominantly concerned with the factual numbers of becoming a minority, he aims to investigate the feeling of the White majority that it is losing status in different realms in society. Feeling that the Other is becoming ‘too many’ (32) ignites feelings among some Whites that their Anglo-Saxon cultural heritage is being lost. The perception of reverse racism has taken hold in mainstream Australia to such an extent that some argue that ‘the most downtrodden person in this country is the white Anglo-Saxon male’ (182).

According to Hage (Citation2000), this perceived loss of power is not merely political rhetoric but is also observed by individuals in their everyday lives. This apparent loss of privilege can be felt, for instance, if non-Anglo-Australians form ethnically exclusionary groups in the workplace. White Australians feel that they face a greater struggle in the labour market, a perception fed by their impression that employers of Asian descent favour employees from their own ethnic group at their expense. Similarly, Hochschild (Citation2017) finds that some White Americans experience a feeling of injustice when they encounter successful Black Americans. These White Americans believe that the success of Black Americans is rooted in undeserved preferential treatment, for instance, through affirmative action plans (cf. the Deep Story in Hochschild Citation2017, 136–140). This feeling of losing privilege is rooted in the idea that their power is being challenged by people with a migration background, despite the fact that public positions of power are still predominantly occupied by Anglo-Whites (Hage Citation2000).

Overall this shows that the former majority may feel like a minority irrespective of factual numerical status and this may influence their attitude and behaviour towards ethnic diversity. To summarise, on the one hand, being confronted with a decrease in factual group size gives rise to pessimistic attitudes. On the other hand, even when people without a migration background have not lost their numerical status, they may still feel that they have done so, and this perception also generates both pessimistic attitudes towards ethnic diversity and a tendency to avoid contact with people with a migration background.

H3: The more people feel like a minority the more negative their attitudes towards ethnic diversity and the lower the amount of inter-ethnic contact.

Method and data

To empirically examine the attitudes and behaviour of people without a migration background to being a numerical ethnic minority, I used data from the Becoming a Minority (BaM) project. The objective of the BaM project is to investigate how people without a migration background respond to becoming a minority in majority-minority city contexts. BaM data was collected in 2019 in five different European cities: Amsterdam, Antwerp, Malmö, Rotterdam and Vienna. In total, 2457 responses from people without a migration background, defined as being born in and having both parents born in the country of survey, were collected in 166 majority-minority neighbourhoods (see Appendix A for the distribution of neighbourhoods per city). The respondents of the BaM survey are between the ages of 25 and 45 (M = 34.51, SD = 6.06) and 53.7% of the sample are female.

Cluster analysis

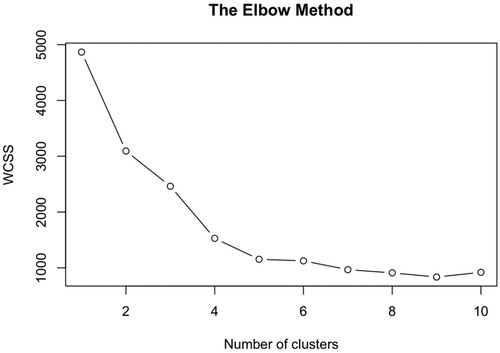

In the first step, I applied a k-means cluster analysis (cf. Lloyd Citation1982), which makes it possible to test whether the reactions outlined in Crul and Lelie's (Citation2019) Integration Matrix are empirically observable in majority-minority contexts. Clustering is an exploratory method extensively used to find groups of observations which share similar characteristics (Wu Citation2012). In k-means cluster analysis, responses to certain variables are as similar as possible within a cluster and as different as possible between clusters. In other words, respondents who score similarly on particular variables are clustered together. In the case of this research, this means that residents who have a similar amount of inter-ethnic contact and a similar attitude towards ethnic diversity are grouped together in the same cluster. The optimal number of clusters was determined by comparing the percentage of variance explained, known as the elbow method (Hothorn and Everitt Citation2014). The two dimensions of the Integration Matrix are operationalised as follows:

Integration/segregation. The behaviour of residents without a migration background was measured by the amount of contact the respondents have with neighbours with a migration background. Here, the question of how many of their contacts in the neighbourhood have a migration background, ranging from (1) almost none, (2) some, (3) about half, (4) the majority to (5) almost all (see Appendix B, for distributions), was used (M = 2.83, SD = 1.07).

Appreciation/rejection of ethnic diversity. The item ‘It is an enrichment to learn more about people from other cultures in the neighbourhood’ was used to measure attitudes towards ethnic diversity in the neighbourhood (M = 3.82, SD = 1.00). Respondents could indicate whether they agreed or disagreed with the statements on a scale from (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) neither disagree nor agree, (4) agree to (5) strongly agree (see Appendix B, for distributions).

Predicting cluster membership

In the second step, I examined whether cluster membership is related to individual characteristics in systematic ways. To do so, I used hierarchical generalised linear modelling as the analytical method. This method makes it possible to account for the structure of the data, that is the dependence of observations at the neighbourhood (n = 166) and city level (n = 5). The clusters extracted in the previous step serve as the categorical dependent variable. Following Engbersen et al. (Citation2013), the members of a particular cluster are compared with all other respondents. To allow the comparisons of effects across groups, average marginal effects (AME) are reported (Mood Citation2010).

In the analysis I included net household income and education to measure socio-economic status. Average net household income is 3.15 measured on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘low’ to ‘high’ (SD = 1.20)Footnote3 and the average education level is 5.69 (SD = 1.54)Footnote4 measured on a 7-point scale. Exposure to diversity was operationalised as neighbourhood tenure (years of residence in the current neighbourhood) and city tenure (years of residence in the city of survey). I operationalised the feeling of being a minority in the neighbourhood with the categorical variable ‘do you feel like a minority in your neighbourhood?’ no is (0) yes is (1).

To account for spuriousness, I controlled for variables related to both socio-economic status and attitude towards ethnic diversity. Hence, gender (54.1% female) and age (M = 34.4, SD = 6.0) (cf. e.g. Zick, Küpper, and Hövermann Citation2011) is included in the analysis. Further, I controlled for the feeling that there had been a recent increase in people with a migration background, which was measured on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘strongly decreased’ (1), ‘decreased’ (2), ‘remained the same’ (3), ‘increased’ (4) to ‘strongly increased’ (5) as this feeling also leads to a more pessimistic attitude towards immigration (Coenders and Scheepers Citation2008; Kaufmann and Harris Citation2015). As the feeling of being a minority in one’s neighbourhood may be a proxy of perceived threat, I controlled for economic threat (Cronbach’s Alpha = .894, M = 5.48, SD = 2.42) and cultural threat (Cronbach’s Alpha = .840, M = 5.30, SD = 2.07). Both scales are based on the means of three items each (see Appendix D, Tables A5 and A6), measured on 11-point scales.

All continuous predictors are mean-centred and missing values are deleted listwise.

Results

The analysis shows that a five-cluster-solution is the best fit to cluster responses to being a minority (see Appendix E Figure A1 for elbow graph). The emerging clusters make theoretical sense and the cluster sizes are appropriate. contains the cluster sizes and cluster centroids of each cluster.

Table 1. Five-cluster solution cluster analysis, cluster centres and distribution (n = 2267).

The quadrants of the Integration Matrix (Crul and Lelie Citation2019) can be identified as cluster 1 corresponding with quadrant A (segregate/reject), cluster 2 with quadrant C (integrate/accept), cluster 3 with quadrant B (integrate/reject) and cluster 5 with quadrant D (segregate/accept). Further, a fifth cluster can be identified which is not represented in the Integration Matrix. Relative to the other clusters, cluster 4 captures a group scoring moderately on attitude towards diversity and the amount of inter-ethnic contact.

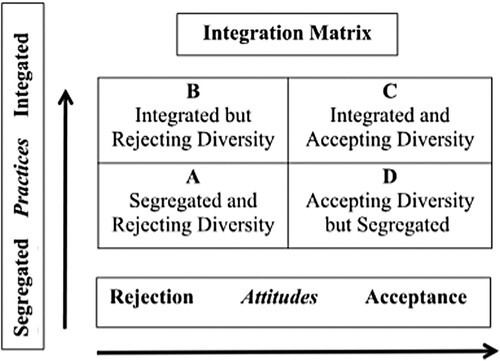

As shown in , I have named the observed clusters as follows: segregated sceptics (cluster 1, n = 101), integrated enthusiasts (cluster 2, n = 949), integrated sceptics (cluster 3, n = 86), moderates (cluster 4, n = 258) and segregated enthusiasts (cluster 5, n = 873).

Explaining reactions to being a minority: predicting cluster membership

As we can see from ,Footnote5 segregated sceptics do not differ significantly from other residents in the neighbourhood except for their increased perceptions of economic (b = .32, p < .010) and cultural (b = .45, p < .000) threat. Integrated enthusiasts are significantly younger (b = −.05 p < .000) women (b = −.44, p < .000) who are more likely to feel that they are a minority (b = .69 p < .000). Integrated sceptics are more likely to feel like a minority in the neighbourhood (b = 1.96, p < .000). Moderates are more likely to be men (b = .38, p < .050) who have lived in the neighbourhood comparably longer (b = .04, p < .010). Segregated enthusiasts are more likely to be older (b = .04, p < .010), higher educated (b = .15, p < .010), from a higher income household (b = .16, p < .010) and less likely to feel like a minority (b = −1.32, p < .000). presents a summary of the regression findings.

Table 2. Determinants of cluster membership: five multi-level logistic regression models (n = 1458, five cities, 164 neighbourhoods).

It can be concluded that H1, predicting the higher the socio-economic position, the more positive the attitudes towards ethnic diversity and the lower the amount of inter-ethnic contact, is partially confirmed. The segregated enthusiasts are higher educated and live in a higher income household. This is in line with previous research findings, showing that the more highly-educated people without a migration background are, the fewer inter-ethnic contacts they maintain (Martinović Citation2013). On the one hand, higher education increases people’s conceptual openness towards ethnic diversity (Citrin et al. Citation1997; Coenders and Scheepers Citation1998; Hainmueller and Hiscox Citation2010; Scheepers, Felling, and Peters Citation1989; van der Waal et al. Citation2010), but on the other hand, their higher socio-economic position provides them with fewer structural opportunities to meet people with a migration background (Boterman and Musterd Citation2016). Yet, H1 can only be partially confirmed as the integrated sceptics do not have a significantly lower socio-economic status. Whereas the expectation was that integrated sceptics would have more structural opportunities to meet people with a migration background due to their lower economic position, the reactions of the integrated sceptics do not seem to be determined by socio-economic factors.

H2, predicting that the longer residents have lived in ethnically diverse contexts the more positive their attitudes towards ethnic diversity and the more inter-ethnic contact they have was not confirmed. Segregated sceptics and integrated enthusiasts have not lived in the neighbourhood and city comparably longer than other respondents. However, moderates have lived in the neighbourhood comparably longer. Yet, rather than being overly positive, the moderates’ attitudes and practices are relatively neutral.

H3, predicting that the more people feel like they are a minority, the more negative their attitudes towards ethnic diversity and the lower the amount of inter-ethnic contact, was not confirmed. Segregated sceptics are not more likely to feel like a minority and, contrary to expectations, integrated enthusiasts are more likely to feel like a minority in their neighbourhood.

Discussion and conclusion

This article applied a nuanced approach to analysing the reactions of people without a migration background to being a numerical ethnic minority. In addition to studying attitudes, which include both positive and negative feelings about living in a more diverse context, this research also looked at people’s practices regarding inter-ethnic contact to scrutinise whether they align with their attitudes. I empirically tested this by making use of Crul and Lelie's (Citation2019) Integration Matrix.

Five types of reaction patterns were observed in the data: (i) segregated sceptics, (ii) integrated enthusiasts, (iii) integrated sceptics, (iv) moderates, (v) segregated enthusiasts. The identified groups should not be understood as static types but rather as a snapshot of reactions to living in a majority-minority neighbourhood and the move between clusters is possible as integration is commonly understood as a process (Berry Citation1997). The outcome of the analysis points to the fact that reactions to being a minority go beyond either appreciation or rejection of ethnic diversity. It demonstrates that reactions are not always clear cut and that there may be discrepancies between attitudes and behaviour. In addition to the four reactions presented in the Integration Matrix (Crul and Lelie Citation2019), there exists a fifth type of reaction: the moderates. Rather than being overly polarised in their attitudes and practices, the moderates’ attitudes towards ethnic diversity and inter-ethnic networks in the neighbourhood seem to have reached the state of ‘commonplace diversity’ (Wessendorf Citation2013).

Integrated enthusiasts make up the largest group, while segregated sceptics form the second smallest group out of the five reactions to being a numerical ethnic minority. This is an unexpected outcome, as the literature on reactions of Whites to becoming a minority at the national level predominantly reports negative reactions (e.g. Craig and Richeson Citation2014b). Most people without a migration background have positive attitudes towards the ethnic diversity in their neighbourhood and they maintain comparably high levels of contact with neighbours of a different ethnic background. Yet, this outcome cannot be uncritically taken at face value. Even if people without a migration background have inter-ethnic contact in the neighbourhood and perceive it as positive, Keskiner and Waldring (Citation2023) demonstrate that inter-ethnic relationships are power relations and thus subject to the effects of privilege. So, despite most people without a migration background having positive attitudes with comparably much inter-ethnic contact, it is important to pay further attention to the qualitative nature and consequences of such contact for both groups as done by Keskiner and Waldring (Citation2023).

Furthermore, ambivalent positions were identified in the data. Previous literature has identified segregated enthusiasts and shown that middle-class residents of diverse neighbourhoods often appreciate the diversity in their neighbourhood but their engagement does not go beyond appreciation (Butler Citation2003). This research has again confirmed that social class plays an important role in identifying segregated enthusiasts. To enrich this insight by adding another explanation to the reaction pattern of segregated enthusiasts, I would like to draw from Schut and Waldring’s work (this issue). Schut and Waldring (Citation2023) demonstrate that it requires (micro) labour to live together in majority-minority neighbourhoods. To make inter-ethnic interactions work, strategic labour is required by residents. Showing that, Schut and Waldring (Citation2023) thus offer another explanation for why a positive attitude does not automatically lead to inter-ethnic contact.

In contrast to the segregated enthusiasts, integrated sceptics have received less attention from researchers. The particular interplay of negative attitudes and a relatively high degree of inter-ethnic contact has so far been neglected in existing studies. As Noble (Citation2013, 166) points out, ethnically diverse neighbourhoods are characterised by inevitable conflict. In order to negotiate such conflict in everyday life, people employ ‘convivial labour’ (Wise Citation2016). This might be especially true for the integrated sceptics, as they have a relatively high degree of contact with people with a migration background but do not appreciate the ethnic diversity in their neighbourhood. This gives rise to questions concerning the tension between having a more negative attitude and relatively high levels of inter-ethnic contact, such as: ‘how do integrated sceptics negotiate their attitude in public encounters?’, ‘do they act up on their pessimistic attitudes?’ or ‘do they put in convivial labour to maintain “civility towards diversity?”’ (Wessendorf Citation2014a).

The analysis has further shown that feeling like a minority is an important determinant for integrated enthusiasts, integrated sceptics and segregated enthusiasts. However, the outcome of the analysis prompts us to question the role of feeling like a minority as a reaction determinant. Whereas previous literature on the feeling of being a minority leads to the expectation that it is a predictor of responses to being a numerical minority, the outcomes of this study point to the fact that feeling like a minority is partly the result of the (perceived) amount of inter-ethnic contact (cf. Lazëri, Citation2023). This is plausible because people with an integrated lifestyle experience situations in which they are more often an actual ethnic minority. The more contact one has with people with a migration background the more likely one is to feel like a minority (cf. integrated sceptics and integrated enthusiasts).

What is striking is that integrated enthusiasts tend to feel more like a minority than other respondents. So far, the focus in the public discourse on ‘becoming a minority’ has mainly been on people who are sceptical of ethnic diversity, portrayed in relation to right-wing populist ideologies. Yet, the analysis shows that people who live an integrated life and support the ethnic diversity in their neighbourhood also feel like a minority. It seems that some inhabitants of majority-minority neighbourhoods accept the reality of being a numerical minority but do not feel threatened by it. This phenomenon challenges to some extent the theoretical foundation of group threat theory. People can feel like a minority in their neighbourhood, while also being likely to appreciate the diversity they live in. This is an important observation, as Hjerm (Citation2007) points out that group threat theory has indirectly influenced European policy-making as legislators fear that an increasing number of people with a migration background in a country threatens ‘the stability needed for a functional democracy’ (1271). In line with Hjerm (Citation2007), who shows that higher numbers of people with a migration background at the country level do not lead to more antagonistic attitudes towards migration, this research supplies evidence that a decrease in in-group size at the neighbourhood level might not directly spark antagonistic attitudes towards people with a migration background.

This study differs from previous studies which refer to becoming a minority at the national level (e.g. Outten et al. Citation2012). The respondents of the BaM survey are the ethnic majority at the country level, which limits the comparability of this research with previous studies. The finding that the segregated sceptics are the second least sizable group whereas the two largest clusters are rather enthusiastic about ethnic diversity needs to be considered in perspective, namely that the respondents of the BaM survey are between 25 and 45 years old and rather highly educated. At the same time, the findings of this study may not be bound to majority-minority contexts but potentially replicable in other contexts that are ethnically diverse but do not classify as ‘majority-minority’. In particular, feeling like a minority does not seem to be rooted in the factual demographic make-up of the neighbourhood, but rather in the extent to which the residents engage in ethnic diversity in the form of inter-ethnic contact.

Further research will have to clarify two aspects. Firstly, future research should investigate to what extent country-level attitudes are influenced by being a local numerical ethnic minority and consider inter-ethnic networks maintained outside the neighbourhood. The current study aimed to empirically test the Integration Matrix (Crul and Lelie Citation2019) in majority-minority contexts and the socio-demographic realities of the neighbourhoods allowed for this. Considering the neighbourhood focus of the study, the labels ‘integrated’ and ‘segregated’ need to be understood as exclusively referring to the neighbourhood context. Yet, inter-ethnic ties are not confined to the borders of the neighbourhood. The neighbourhood is one of many social realms in which inter-ethnic contact can be maintained and respondents may maintain inter-ethnic ties outside their neighbourhood.

Secondly, for this research, migration background was defined for the first and second generation. The third generation, however, makes up an increasingly substantial proportion of the local population and it is probable that because of the migration history in their families, they are more likely to have inter-ethnic ties and a greater appreciation of diversity in general. Future research should investigate to what extent the amount of inter-ethnic contact and attitudes towards diversity differ between third-generation migrants and people without a migration background three generations or later. Both research suggestions could contribute to our understanding of the phenomenon of migration and its consequences for contemporary societies from the perspective of people without a migration background.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For Amsterdam and Malmö a migration background is defined as: born abroad or with at least one parent born abroad, source: www.ois.amsterdam.nl, www.scb.se. For Vienna: born abroad with or without Austrian nationality (34%), born in Austria with foreign nationality or born in Austria with at least one parent born abroad (20%), source: Stadt Wien MA 17 (Citation2017).

2 For this research, this is defined as the people in question and both of their parents being born in the country of survey. When the literature uses different terminology due to country/context specifics (e.g. “White” or “natives”), I adapt to this terminology.

3 To adjust for country-context, net household income was measured differently across countries. See Appendix C for exact categories and subsequent recoding.

4 Based on the International Standard Classification of Education 2011 (ISCED) education level ranges from (1) less than lower secondary (I), to (2) lower secondary (II), to (3) lower tier upper secondary (IIIb), to (4) upper tier upper secondary (IIIa), (5) advanced vocational training (IV), (6) lower tertiary education (VI), (7) higher tertiary education (VII).

5 Based on Rose, Carrasco, and Charboneau (Citation1998) I conducted sensitivity analyses in which I controlled for the main effect of ‘having children’ and an interaction effect of ‘having children’ with gender. These effects do not meaningfully impact the effects of socio-economic background, exposure to diversity or feeling like a minority.

References

- Alba, R., and J. W. Duyvendak. 2019. “What About the Mainstream? Assimilation in Super-Diverse Times.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (1): 105–124. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1406127.

- Barr, S. 2004. “Are we all Environmentalists now? Rhetoric and Reality in Environmental Action.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 35 (2): 231–249. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2003.08.009.

- Beider, H., S. Harwood, and K. Chahal. 2017. “The Other America”: White Working-Class Views on Belonging, Change, Identity, and Immigration.

- Berry, J. 1997. “Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaption.” In Applied Psychology: An International Review, edited by Richard W. Brislin, 5–68. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781483325392.n11

- Blalock, H. M. 1967. Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Blau, P. M. 1960. “Structural Effects.” American Sociological Review 25 (2): 178. doi:10.2307/2092624.

- Blau, P. M. 1977. Inequality and Heterogeneity. A Primitive Theory of Social Structure. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Blokland, T., and G. van Eijk. 2010. “Do People Who Like Diversity Practice Diversity in Neighbourhood Life? Neighbourhood Use and the Social Networks of ‘Diversity-Seekers’ in a Mixed Neighbourhood in the Netherlands.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (2): 313–332. doi:10.1080/13691830903387436.

- Blumer, H. 1999. “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position.” In Rethinking the Color Line: Readings in Race and Ethncity, edited by C. A. Gallagher, 99–105. Thousand Oaks, CA: Mayfield.

- Boterman, W. R., and S. Musterd. 2016. “Cocooning Urban Life : Exposure to Diversity in Neighbourhoods, Workplaces and Transport.” JCIT 59: 139–147. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2015.10.018.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Routledge & Kegan Paul. doi:10.1109/IMPACT.2010.5699514

- Breugelmans, S. M., and F. J. R. van de Vijver. 2004. “Antecedents and Components of Majority Attitudes Toward Multiculturalism in the Netherlands.” Applied Psychology 53 (3): 400–422. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00177.x.

- Butler, T. 2003. “Living in the Bubble: Gentrification and its “Others” in North London.” Urban Studies 40 (12): 2469–2486. doi:10.1080/0042098032000136165.

- Citrin, J., D. P. Green, C. Muste, and C. Wong. 1997. “Public Opinion Toward Immigration Reform: The Role of Economic Motivations.” The Journal of Politics 59 (3): 858–881. doi:10.2307/2998640.

- Coenders, M., and P. Scheepers. 1998. “Support for Ethnic Discrimination in the Netherlands 1979-1993: Effects of Period, Cohort, and Individual Characteristics.” European Sociological Review 14 (4): 405–422. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a018247.

- Coenders, M., and P. Scheepers. 2008. “Changes in Resistance to the Social Integration of Foreigners in Germany 1980-2000: Individual and Contextual Determinants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1080/13691830701708809.

- Craig, M. A., and J. A. Richeson. 2014a. “On the Precipice of a “Majority-Minority” America.” Psychological Science 25 (6): 1189–1197. doi:10.1177/0956797614527113.

- Craig, M. A., and J. A. Richeson. 2014b. “More Diverse Yet Less Tolerant? How the Increasingly Diverse Racial Landscape Affects White Americans’ Racial Attitudes.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40 (6): 750–761. doi:10.1177/0146167214524993.

- Craig, M. A., J. M. Rucker, and J. A. Richeson. 2018. “Racial and Political Dynamics of an Approaching “Majority-Minority” United States.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 677 (1): 204–214. doi:10.1177/0002716218766269.

- Crul, M., and F. Lelie. 2017. “De ‘integratie’ van mensen van Nederlandse afkomst in superdiverse wijken.” Tijdschrift Over Cultuur & Criminaliteit 7 (1): 39–56. doi:10.5553/TCC/221195072017007001003.

- Crul, M., and F. Lelie. 2019. The ‘Integration’ of People of Dutch Descent in Superdiverse Neighbourhoods, 191–207. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-96041-8_10

- Crul, M., F. Lelie, E. Keskiner, L. Michon, and I. Waldring. 2023. “How do People Without Migration Background Experience and Impact Today’s Superdiverse Cities?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (8): 1937–1956. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2182548.

- Danbold, F., and Y. J. Huo. 2015. “No Longer “All-American”? Whites’ Defensive Reactions to Their Numerical Decline.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 6 (2): 210–218. doi:10.1177/1948550614546355.

- Engbersen, G., A. Leerkes, I. Grabowska-Lusinska, E. Snel, and J. Burgers. 2013. “On the Differential Attachments of Migrants from Central and Eastern Europe: A Typology of Labour Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (6): 959–981. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2013.765663.

- Fiske, S. T., C. H. Dupree, G. Nicolas, and J. K. Swencionis. 2016. “Status, Power, and Intergroup Relations: The Personal is the Societal.” Current Opinion in Psychology 11: 44–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.012.

- Hage, G. 2000. White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hainmueller, J., and M. J. Hiscox. 2010. “Attitudes Toward Highly Skilled and low-Skilled Immigration: Evidence from a Survey Experiment.” American Political Science Review 104 (1): 61–84. doi:10.1017/S0003055409990372.

- Hjerm, M. 2007. “Do Numbers Really Count? Group Threat Theory Revisited.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33 (8): 1253–1275. doi:10.1080/13691830701614056.

- Hochschild, A. 2017. Strangers in Their own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. New York, NY: The New Press. doi:10.1007/s12115-017-0177-y

- Hothorn, T., and B. S. Everitt. 2014. Statistical Analyses Using R. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis.

- Kaufmann, E., and G. Harris. 2015. ““White Flight” or Positive Contact? Local Diversity and Attitudes to Immigration in Britain.” Comparative Political Studies 48 (12): 1563–1590. doi:10.1177/0010414015581684.

- Keskiner, E., and I. Waldring. 2023. “Revisiting the Established-Outsider Constellation in a Gentrifying Majority-Minority Neighbourhood.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (8): 2052–2069. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2182554.

- Kokolakis, S. 2017. “Privacy Attitudes and Privacy Behaviour: A Review of Current Research on the Privacy Paradox Phenomenon.” Computers & Security 64: 122–134. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2015.07.002.

- Lazëri, M. 2023. “Understanding Minority Feeling among People without a Migration Background: Evidence from Five Majority-minority European Cities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (8): 1977–1995. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2182550.

- Lloyd, S. 1982. “Least Squares Quantization in PCM.” IEEE Transactions in Information Theory 28 (2): 129–137. doi:10.1109/TIT.1982.1056489

- Martinović, B. 2013. “The Inter-Ethnic Contacts of Immigrants and Natives in the Netherlands: A Two-Sided Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (1): 69–85. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2013.723249.

- Mepschen, P. 2016. “The Culturalization of Citizenship.” In The Culturalization of Citizenship: Belonging and Polarization in a Globalizing World, edited by J. W. Duyvendak, P. Geschiere, and E. Tonkens, 1–231. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-53410-1

- Mepschen, P. 2019. “A Discourse of Displacement: Super-Diversity, Urban Citizenship, and the Politics of Autochthony in Amsterdam.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (1): 71–88. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1406967.

- Mood, C. 2010. “Logistic Regression: Why We Cannot Do What We Think We Can Do, and What We Can Do About It.” European Sociological Review 26 (1): 67–82. doi:10.1093/esr/jcp006.

- Moraes, C., M. Carrigan, and I. Szmigin. 2012. “The Coherence of Inconsistencies: Attitude–Behaviour Gaps and new Consumption Communities.” Journal of Marketing Management 28 (1–2): 103–128. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2011.615482.

- Noble, G. 2013. “Cosmopolitan Habits: The Capacities and Habitats of Intercultural Conviviality.” Body and Society 19 (2–3): 162–185. doi:10.1177/1357034X12474477.

- Oosterlynck, S., A. Saeys, Y. Albeda, N. van Puymbroeck, and G. Verschraegen. 2017. “Dealing with Urban Diversity: The Case of Antwerp.” Xerox. www.urbandivercities.eu.

- Outten, H. R., M. T. Schmitt, D. A. Miller, and A. L. Garcia. 2012. “Feeling Threatened About the Future: Whites’ Emotional Reactions to Anticipated Ethnic Demographic Changes.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 38 (1): 14–25. doi:10.1177/0146167211418531.

- Rose, D., P. Carrasco, and J. Charboneau. 1998. The Role of ‘weak ties’ in the Settlement Experiences of Immigrant Women with Young Children: The Case of Central Americans in Montréal.

- Scheepers, P., A. Felling, and J. Peters. 1989. “Ethnocentrism in The Netherlands: A Typological Analysis.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 12 (3): 289–308. doi:10.1080/01419870.1989.9993636.

- Schut, J., and I. Waldring. 2023. “Micro Labour, Ambivalence and Discomfort: How People Without a Migration Background Strategically Engage with Difference in a Majority–Minority Neighbourhood.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (8): 2034–2051. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2182553.

- Simmel, G. 1950. “The Metropolis and Mental Life.” In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, edited by K. H. Wolff, 409–424. New York: Free Press. doi:10.1353/nlh.2007.0002

- Stadt Wien MA 17. 2017. Monitoring Integration Diversität Wien 2013-2016.

- van der Waal, J., P. Achterberg, D. Houtman, W. de Koster, and K. Manevska. 2010. “‘Some are More Equal Than Others’: Economic Egalitarianism and Welfare Chauvinism in the Netherlands.” Journal of European Social Policy 20 (4): 350–363. doi:10.1177/0958928710374376.

- Warren, J. W., and F. W. Twine. 1997. “White Americans, The New Minority? Non-Blacks and the Ever-Expanding Boundaries of Whiteness.” Journal of Black Studies 28 (2): 200–2118. doi:10.1177/002193479702800204

- Wessendorf, S. 2013. “Commonplace Diversity and the ‘Ethos of Mixing’: Perceptions of Difference in a London Neighbourhood.” Identities 20 (4): 407–422. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2013.822374.

- Wessendorf, S. 2014a. ““Being Open, but Sometimes Closed”. Conviviality in a Super-Diverse London Neighbourhood.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 17 (4): 392–405. doi:10.1177/1367549413510415.

- Wessendorf, S. 2014b. Commonplace Diversity: Social Relations in a Super-Diverse Context. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wessendorf, S. 2014c. “The Ethos of Mixing.” In Commonplace Diversity: Social Relations in a Super-Diverse Context, 102–120. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/9781137033314_6

- Wise, A. 2016. “Convivial Labour and the ‘Joking Relationship’: Humour and Everyday Multiculturalism at Work.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 37 (5): 481–500. doi:10.1080/07256868.2016.1211628.

- Wu, J. 2012. Advances in K-Means Clustering. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-29807-3

- Zick, A., B. Küpper, and A. Hövermann. 2011. Intolerance, Prejudice and Discrimination: A European Report. Berlin, Germany: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Appendices

Appendix A: number of neighbourhoods per city

Table A1. Number of neighbourhoods per city.

Appendix B: distribution of cluster variables

Table A2. Distribution variable integrate/segregation.

Table A3. Distribution variable appreciation/rejection of ethnic diversity.

Appendix C: country-specific answer categories net household income

Table A4. Variable net household income with initial answer categories per country in parentheses.

Appendix D: items for the economic threat and cultural threat scales

Table A5. Items for the economic threat scale (Cronbach’s Alpha = .894).

Table A6. Items for the cultural threat scale (Cronbach’s Alpha = .840).