ABSTRACT

Our contribution to this special issue brings the theoretical and empirical orientations of the Becoming a Minority (BaM) project into dialogue with the complex and charged post-Brexit geography of the North of England. We present findings from the UK ESRC funded project Northern Exposure: Race, Nation and Disaffection in ‘Ordinary’ Towns and Cities after Brexit, drawing upon a period of co-productive and ethnographic work with local authority stakeholders, voluntary sector practitioners and community actors in two urban locations in the English North: Halifax and Wakefield. We report on how shifting patterns of diversity and population change interlock with deindustrialised economies, fiscal austerity, the coronavirus crisis, and the predations of ethno-nationalist politics and policy. Amid these dislocations and risks, we find delicate, differentiated, and predominantly informal infrastructures of community governance and intervention attempting to build alliances and resolve tensions: a grounded, local-view that belies the kind of image of the North established in mainstream national understandings of the dramatic politics of Brexit and after. Taking a productive cue from the BaM study, we offer some fine-grained reflections on localised dynamics of diversity experience and the negotiation of inter-ethnic relations albeit in a sprawling urban region beyond the West-European metropolitan core.

Introduction

In June 2016, a narrow majority of the British electorate voted to exit the European Union, backing a Leave campaign that had successfully conflated and inflamed questions of ‘immigration’ and racial diversity in relation to UK membership (Favell Citation2020). Seven days before the vote, on the same day UK Independence Party (UKIP) leader Nigel Farage launched the notorious ‘Breaking Point’ poster – blaming the EU for uncontrollable flows of asylum seekers to the country – a young Labour Party Member of Parliament – Jo Cox – was murdered in Birtstall in West Yorkshire in the North of England, by a neo-fascist fanatic, Thomas Mair. He had targeted her as a race ‘traitor’ and ‘collaborator’, linked to her support for remaining in the EU. Cox was also known as a vocal advocate of a more generous approach to asylum seekers, a question on which Britain had lagged behind many of its neighbours.

When the referendum results came through, a decisive majority of people across the North of England preferred to leave the EU, including in many constituencies such as Cox's that had historically been Labour Party strongholds. The Leave campaign mantra of ‘taking back control’, repeated on Farage's poster, had ricocheted across the region, apparently galvanising people to support a vote that not only took the UK out of the EU, but put into question the multi-racial settlement that had been a hallmark of British approaches to diversity in the post-war period (Favell Citation1998). For many mainstream analysts and pundits, these events appeared to confirm the long-debated demise of the British commitment to multiculturalism (as defended, i.e. by Parekh et al. Citation2000), representing an indelible ‘white shift’ in British politics, to echo the controversial analysis of Eric Kaufmann (Citation2018). This kind of conclusion – and the incendiary race politics it reflects and forecasts – needs close interrogation. To date, though, the most influential analyses of these tumultuous politics in Britain have been quantitative, driven by public opinion, and quite insular in their focus on the dynamics of British politics and society (e.g. Ford and Goodwin Citation2017; Curtice Citation2017). Where they refer to anything comparative, it is to the USA, the politics of Trump and the pattern of ‘cultural wars’ that contaminate US politics (Kaufmann Citation2018; Sobolewska and Ford Citation2019). Yet Britain remains a European society, and a more relevant comparison ought to be its closest geographical neighbours. Hence, in this special edition, we bring our work into dialogue with the Becoming a Minority project (BaM), thereby looking at patterns of conviviality and/or conflict in the North of England, in the context of increasingly ‘superdiverse’ neighbourhoods of Northwest European cities (see Crul et al. Citation2023 in this volume).

After a first section setting the scene – which introduces our large-scale project, Northern Exposure: Race, Nation and Disaffection in ‘Ordinary’ Towns and Cities after Brexit (2019-2022) – we discuss our operationalisation of some of BaM's concerns. Like BaM, we zoom in on local neighbourhood contexts (e.g. Schut and Waldring Citation2023 in this volume), to restate the importance of understanding these ‘multicultural’ dynamics amid extremely challenging economic and political conditions. In our findings, we present co-productive work with local stakeholders in two of our mid-sized urban case studies in the North of England: Halifax and Wakefield. We report on how, amid variable structures of community representation, the hollowing out of local welfare states, capricious national funding programmes, and entrenched but diffuse patterns of urban deprivation, individuals and groups attempt to build alliances and resolve tensions through the creation of lively yet delicate infrastructures of community intervention. Our account of these imperfect yet resilient multicultural politics in the North is very different to the one now established in mainstream analyses of Brexit, and its politically shattering effects on the region. We reject the discursive flattening of inter-ethnic dynamics in Northern England and the over-statement of White British and so-called ‘White working class’ resentment, all of which is being used to buttress shallow agendas of economic and social protectionism. Our paper is positioned to not only tease out some comparative synergies with the BaM study, but to stand in alignment with emerging scholarship in the UK that has addressed the complex, intersecting politics of race, class and place that cohere in English Northern towns and regions, but which have been mischaracterised in mainstream political discourses (see Miah et al Citation2020; Maikin-Waite Citation2021).

Race, nation and disaffection in Brexit England

During her maiden parliamentary speech, a year before her death, Jo Cox spoke of her pride in representing a constituency – Batley and Spen – where she was ‘born and bred’. She described it thus:

A gathering of typically independent, no-nonsense and proud Yorkshire towns and villages. Our communities have been deeply enhanced by immigration, be it of Irish Catholics … or of Muslims from Gujarat in India or from Pakistan, principally from Kashmir. While we celebrate our diversity, what surprises me time and time again as I travel around the constituency is that we are far more united and have far more in common than that which divides us (Hansard Citation2015).

Undergirding this consensus was an emergent eco-system of journalists, academics and popular intellectuals gripped by the storytelling potential of the ‘left-behind’. Fixated on the possibilities of social media, news voxpop and online clickbait, ostensibly academic and/or commentariat figures such as Matthew Goodwin, David Goodhart – and the aforementioned Kaufmann – found a new lurid currency dabbling in an alt-right playbook: berating the ‘woke’ indulgences of mobile cosmopolitan elites (Kaufmann Citation2020) and multi-ethnic millennials attracted to the urban ‘bubble’ of Corbynism (Eatwell and Goodwill Citation2018). Time and again, it was the imputed values and resentments of ‘native’, assumably ‘white’, working class populations with attachments to ‘place’ and ‘community’ (Goodhart Citation2017) who were invoked to indict these out of touch, ‘elite’ and ‘metropolitan’ ‘Remainers’ for trying to overturn the Brexit vote. Their most visible outputs took the form of incendiary articles, controversial airport lounge books, endless aggressive tweets, and snap opinion polls (Survey Monkey is a favourite methodology of Kaufmann; Goodwin's most famous analytical figure was a word cloud of public opinion on Brexit in which ‘immigration’ overwhelms every other term as the keyword voiced by voters). These interventions were effectively glib but effective stylisations of more substantial research also underlining the polarisation in economic or cultural terms of English society (Jennings and Stoker Citation2016; Hobolt Citation2017; Sobolewska and Ford Citation2020), the betrayal of the working class by ‘third way’ New Labour (Evans and Tilley Citation2017), the regional inequities of globalised capitalism (e.g. Rodríguez-Pose Citation2017), and the (again, coded ‘white’) working class identity and representation crises found in alienated rustbelts across Europe and the US (e.g. Guilluy Citation2014; Gest Citation2016; Hochschild Citation2016; McQuarrie Citation2017). They also found a hospitable welcome in Westminster think tanks where, post-Brexit, Goodhart and Kaufmann took up sinecures at centre-right Policy Exchange, and Goodwin at the pro-Brexit Legatum Institute. More generally, their prominent voices reflected the ‘faith, flag and family’ tendencies ascendent after Brexit within both the Labour and Conservative Parties; with these intellectual influences finding expression in ‘Blue Labour’ or ‘Red Tory’ think tanks, such as the Centre for Towns and Onward. At a policy level, all of this was funnelled into tightened border and immigration regimes and a new pork-barrel regeneration agenda – labelled ‘levelling up’ – designed to future proof the Conservative electoral breakthrough in Northern constituencies (MacLeod and Jones Citation2018). Investment via a national funding stream called the ‘Towns Fund’ has been notoriously biased towards Conservative constituencies (Hanretty Citation2021), but is ringfenced for capital spending only and pales in comparison with the decade of fiscal austerity meted out to those towns newly in political favour (Gray and Barford Citation2018).

Amid this onslaught, Northern Exposure fashioned a project in and for the small cities and towns of the North of England embedded in the social geography that Jo Cox articulated in her speech. It avoids reproducing stylised and stereotyped understandings of the region, instead designed in line with Bhambra’s (Citation2017) critique of the ‘methodological whiteness’ which frames ‘the North’ as an undifferentiated landscape of polarisation and angry white working class ‘concerns’ being voiced ‘legitimately’ about immigration and multiculturalism, and in which regeneration agendas allegedly should be anchored (see also Benson Citation2019). Our distinctive approach was to shift to a comparative local scale, and prioritise an extensive, grounded sociological engagement with the conditions and geographies of places that have existed on the fringes of British cultural, community and critical race studies alike. We challenge racially homogenised accounts of the ‘North’ and complicate simplistic readings of disaffection. Our approach was also inspired by potential cross-national comparisons and dissatisfaction with emergent studies of majority population political disaffection in Western Europe (i.e. Koopmans and Orgad Citation2020), which leads to our affinity with BaM.

Becoming a minority in the UK?

The BaM study offers a congenial model of empirical investigation that overlaps significantly with the sociological focus of Northern Exposure on shifting inter-ethnic neighbourhood relations within contemporary Europe. For BaM, the context is the fast-changing ‘superdiversity’ of cities in North-west Europe foregrounds the politics and experiences of those populations ‘without a migration background’ living amid urban diversity (see Kraus Citation2023 in this volume), without over-stating their resentment – as mainstream research in the UK has. It teases out what drives attitudes and practices to differentiate and track different sorts of conflictual or convivial outcomes (see Gilroy Citation2004) – against familiar backdrops of everyday racism, rising populism, and the in-built ‘methodological nationalism’ of national scale policy and political thinking on immigration and integration. Our common emphasis on post-industrial historical trajectories as a determinant aspect of contemporary relations is another important focus, as is the emphasis on grounded local work with actors and institutions, and the use of mixed methods, with in-depth interviews at the core (see Schut and Waldring Citation2023 in this volume). Like BaM, Northern Exposure has a concern with the management of inter-ethnic relations and the possibilities of positive negotiation, interaction and engagement at local urban scales. At the same time, certain creative differences with BaM have also proven helpful to position Northern Exposure comparatively and explicate its distinctive methodology.

Most obvious is the social and economic geography of the respective cases. BaM focuses on wealthy, cosmopolitan cities with large, diverse migrant populations and powerful local governments that carry significant weight in their national political contexts. Northern Exposure, by contrast, focuses on second tier large towns and small cities in Northern England. These are places that have struggled to recover from post-industrial decline and in some cases are even losing populations. The project is centred on four case studies: Preston, Halifax, Wakefield, and Middlesbrough. Each has a distinct history within the narrative of English industrial modernity and remains populated by a ‘majority’ of White British, albeit with firmly embedded, usually spatially concentrated ‘minority’ populations and some growing ‘superdiversity’ in parts owing to EU migration and UK asylum-seeker ‘dispersal’ policies at the national level, first introduced by New Labour in 2001 (compare also Rogaly Citation2020 on Peterborough). These towns and cities are lesser nodes in a regional urban sprawl of the North of England that is akin to the Randstad or Ruhr Valley. The agglomeration here is comprised of ‘core’ cities, old mill and market towns, peripheral mining villages and an epic rural expanse, cut through with motorways and logistics distribution sheds, and mainly south to north high speed train lines. Only 200 km wide between Liverpool in the west and Hull on the east, but including the north-east centred on Newcastle, ‘the North’ as it is referred to is home to around a quarter of the UK population. The east and west coasts are dotted with faded resorts and struggling ports. Whilst two of these will become post-Brexit ‘freeports’ in late 2021 (one of these is Middlesbrough), in centre-periphery globalisation terms, these locations pose a backdrop of diversity distinct to global nodes of transportation such as Antwerpen, Rotterdam, Hamburg or Malmö. Within this broader geography, the two places we focus on here – Halifax (town) and Wakefield (city and district) – are found in the orbit of Leeds and the greater West Yorkshire conurbation. Despite these differences, there is a common link with BaM regarding the intensity of far-right mobilisation. The British National Party and UKIP have each had success at a local government scale in Northern towns since the early 2000s (Ford and Goodwin Citation2014), and fascist organisations the English Defence League and Britain First attempt to hold regular marches across the region. These formations may have been absorbed by Boris Johnson's Conservative Party or stilled by the consolations of Brexit, but it is notable that West Yorkshire recorded the most race hate crimes nationally in the country in 2020, in which religious and race hate crimes have risen since 2015, including spikes during the referendum and Black Lives Matter protests (House of Commons Library Citation2020).

Methodologically, where BaM is focused on intensely mixed neighbourhoods within prominent cities and focuses on the attitudes and behaviours of people ‘without a migration background’, Northern Exposure explores a broader range of neighbourhood types within each case befitting the typical social geography of Northern towns. This includes districts with significant deprivation and racial minority or ethnic migrant diversity, homogenous white lower-middle class suburbs, and largely mono-ethnic (White British) peripheral housing estates. This variation is important because it belies the stereotypical social geographies assumed by much of the ‘red wall’ and ‘levelling up’ literature, rooted in outdated, monolithic notions of the industrial North (The Economist Citation2021). It also underlines some of the complexity in managing inter-ethnic relations within such a diffuse landscape.

In each of these locations, we collected quantitative, qualitative and ethnographic data to map patterns of local (sometimes ‘super’) diversity, probed at lived intersections of race, class and place across a sample of sub-locations and populations, and established if and how infrastructures of support emerge in the face of inter-ethnic tension and widespread economic precarity. Our main output is the creation of a large archive of around 160 oral history interviews in specific localities within the case studies.Footnote1 To prepare this work, we engaged in a long exploratory phase, which is what we report upon here. In this, we consulted, interviewed, and developed partnerships with local government, local statutory actors such as the Police, voluntary sector organisations and community activists, to understand the context of governance in which histories, landscapes and experiences of tension, diversity and inclusion/exclusion are managed in each case (an approach which parallels Jones Citation2015). The research design of the wider project and its implementation reflected our involvement in local policy discussions about deprivation, disaffection and community conflicts. The findings here are thus presented as a work of co-production, with a central goal of articulating local authority and third sector viewpoints on governance, in the face of often insensitive and ill-informed national government initiatives.

Northern towns and cities

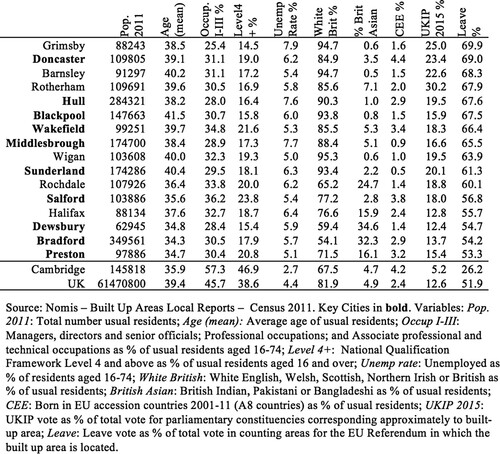

Northern Exposure purposefully avoided the large (majority Remain supporting) metropolitan centres of Leeds, Manchester and Newcastle. Facing a choice of potential research sites across the North, data for 16 typical locations in the category of large town / small city was compiled, including population data, some basic socio-economic indicators, and key voting patterns (most reflecting data still reliant on the 2011 census). Some of these locations are part of a national network of second tier ‘Key Cities’ that have organised to counterbalance the influence of ‘core’ (i.e. major) cities; all are archetypally ‘northern’. Here, they are referenced against Cambridge, one of the most affluent and highest ‘Remain’ voting locations in the south-east of the country (see ).

Figure 1. Demographic and political patterns in 16 English towns and small cities. Reproduced from Barbulescu et al. (Citation2019). With thanks to our Northern Exposure colleague Albert Varela who compiled the data for this report, which anchors our overall project design.

From these, Northern Exposure selected four archetypal post-industrial locations that captured different political-economic trajectories and urbanisation patterns whilst enabling rich comparability. Here, we focus on two: Halifax and Wakefield.

Halifax (pop. 88,000) is a handsome but downtrodden town, located amid steep banks and rolling hills midway between Leeds and Manchester. It was once a thriving textiles and banking centre and has a rich migration history with pockets of inner-urban super-diversity. These are especially concentrated around the deprived Park ward, west of the town centre, made up of concentrated Victorian terraced housing blocks and inhabited mainly by a South Asian Pakistani community alongside older white residents, but also now East Europeans and new refugee settlers. This area contrasts with the 1960s and 1970s housing estates and tower blocks isolated in valleys and hills in the equally deprived periphery to the north – notably, the predominantly White British districts of Ovenden and Mixenden. The comparative interest here is thus that Park ward is physically and visibly very different, yet posts very similar deprivation ratings to the other, poor white areas. At the same time, central Halifax has undergone a degree of high-profile cultural regeneration based around arts and media. To this extent, it stands in some alignment with those parts of Calderdale – a long, urbanised valley of small towns – which harbour highly value-diverse middle-class populations (nearby Hebden Bridge is renowned as a queer ‘capital’ of the UK, whilst Todmorden is world famous for its ‘incredible edible’ home grown farming movement). The hinterland politics are thus quite particular: the Calderdale valley is, on the one hand, oriented to the red-green left with some anchoring in industrial-era cooperative movements, and on the other, to deep Tory blue instincts in more rural areas. Electorally, this translated recently into a rare, unexpected hold for Labour in 2019 in Halifax, where a young woman MP close in her politics to Jo Cox was elected (with a reduced vote share) whilst the more divided Calder Valley elected a right-wing Conservative businessman.

Wakefield in contrast is a more sprawling peri-urban mass lying just a few miles to the south of Leeds. It lies only 15 miles from Halifax, along the A638 road which passes through the heart of Jo Cox's constituency in the neighbouring district of Kirklees. At its heart is the city of Wakefield (pop 99,000). Like Halifax, it had a grand past as a medieval regional centre, then as a centre of the coal and textiles industries. It is now the administrative centre of the sprawling Wakefield metropolitan district (pop. 345,000) comprised of rural dormitories, proud small towns, and ‘pit villages’ indelibly linked to former coal mines. The last coal mine to close in the UK – Kellingley (in 2015) – was in Knottingley, one of the ‘five towns’ that comprise the north-eastern corner of the district. This expanse of flatland is criss-crossed by motorways and railway lines and is now a major warehouse and logistics back-office region for large retail firms. Wakefield city itself still has some tertiary public sector functions (West Yorkshire Police is based here), but it is perhaps better known as being the largest city in the UK without a university or a professional football team. A White British population dominates the district, including in most of its poorest and most peripheral towns, although there are South Asian, mainly British Pakistani, inner-urban enclaves in Wakefield city and there is a significant if disparate Polish community across the district. The largest asylum seeker ‘reception centre’ in the UK – Urban House – is also based in Wakefield city. It has space for around 300 asylum seekers who stay for varying periods, sometimes months, whilst their initial asylum claims are lodged. Many more are accommodated in nearby hotels and bed and breakfast lodgings (Grayson Citation2020). If they are ‘dispersed’ into the city, asylum seekers are accommodated in contracted housing, including on one large housing estate, Eastmoor. If approved, they are given 28 days to find accommodation in the often-dilapidated local private rental housing sector. Wakefield city has its own cultural regeneration programme and has a significant arts and museum scene which often stands in strained relation with local deprived and isolated communities. Politically, Wakefield was key to the 2019 Conservative electoral strategy of winning over Labour ‘leave’ voters to flip parliamentary seats that historically have rarely voted blue. Sure enough, Wakefield – which was for decades an old left stronghold reflecting mining traditions and charismatic local strongman leadership – was captured in 2019 by a Johnsonian politician of British Asian heritage. This victory capitalised on a damaging split between the sitting MP, an important New Labour figure who had been part of a wave of new young women MPs in the 2000s, and the more traditionalist Labour leader of the Council, a prominent local Brexiteer. Soon after, the new MP was embroiled in a sex scandal and resigned, leading to a by-election that received intense national attention as a key marginal, returning once again a Labour MP. In both Halifax and Wakefield, a significant majority of voters chose to leave the EU in 2016.

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated national lockdown policies placed intense strain on the municipal budgets of towns and cities across the North. The virus generated high caseloads, new vulnerabilities and disproportionate death rates. Local stakeholders scrambled to support community shielding, implement test and tracing regimes, enforce lockdown rules, and help populations at risk of unemployment, food poverty, mental health problems and rent arrears. At the same time, new relations between the public and third sector were forged in the name of community mobilisation and protection. It is here that the main focus of this paper lies: in understanding some of the ways that locally-specific forms of ‘inclusion’ and ‘cohesion’ that might still best described as ‘multicultural’ are practised and negotiated at a district or municipal scale. This is all in spite of deep austerity budget cuts since 2010, hostile national policy conversations around nation, race and empire, and the heavily racialised emergency of the UK's coronavirus pandemic. The local politics of the North, in these two places as in others, belie the image now inscribed in dominant national political and academic readings of the region, while revealing surprising developments that often run against archetypal portraits of disaffection and/or mobilisation. In our final section, then, we look at various dimensions of these local initiatives, identifying the mesh of governance and community infrastructures upholding racial diversity and fragile inter-ethnic relations. The strategy is to compare and contrast Halifax and Wakefield, while reducing neither to straightforwardly positive or negative assessments. We foreground these because they enrich our understanding of the particular urban geographies and social landscapes of the North. They demonstrate the ambivalences of performing and negotiating cohesion and development work in such charged and complex urban environments (again echoing Jones Citation2015). The following sections thus draw on our co-productive work with various stakeholders and local partners during the first two years of the research project. These took the form of local authority and community meetings, phone calls, Zoom chats, email exchanges, and interactive board meetings, all written up as extended research notes. We are necessarily guarded about specific personal identities, and stress their archetypal nature; however, the local knowledge presented here is of course place and person specific.

Bridges or walls? The human infrastructure of local governance

Local authorities and third sectors

The co-productive goals of Northern Exposure have been built on fostering warm relations between the academic research team and non-academic partners. Given the contexts we were entering our offer of (modest) research and networking capacity was widely welcomed. Local governments have found their own ability to take on data analysis and community engagement ravaged by austerity, while facing increases in street and online racism post-Brexit, ongoing extreme right mobilisation, and destabilised community relations because of the Windrush scandal (Cummings Citation2020). Officials in Halifax and Wakefield were happy to task us with mapping issues and populations locally, providing an ear to the ground for shifting disaffection, and staging dialogues between stakeholders. Regular meetings of our Commission on Diversity in the North provided a forum for sharing information and news, building on its initial report about class, race and inequality in the North (published with Runnymede Trust; see Barbulescu et al. Citation2019). At a critical moment when local authorities wanted and needed to be ‘on the ground’ addressing heightened tensions around race and deprivation they were often dependent on third and community sector spaces and on precarious funding streams for communication, outreach and intervention. The nature of this ‘dependence’ appears quite different in the two cases.

The heavily centralised Wakefield council is felt by some third sector respondents to be distant, unresponsive and paternalistic whilst community representation on the city's consultative bodies for minority ethnic and migrant populations has historically been limited. Given this tension and the changing political tides of the district, the election of the new Conservative MP in 2019 was followed, during the 2021 local government elections, by the election of an energetic younger Asian candidate for the Conservatives in the relatively superdiverse inner city Wakefield East ward. In more peripheral ex-mining areas in the east of the district, far-right voting and organisation has been a recurring feature but these have tended to be faced down by local trade union and Labour Party activists. What Wakefield does have is a network of community centres, often located within its social housing estates and staffed by a core of committed workers and volunteers, which can be called upon for local authority / third sector partnership. Funding for these centres is deeply uncertain but the COVID-19 crisis has seen the council re-establish direct subsidies to set them up as crisis hubs, community outreach, food banks and vaccination centres. Whilst these centres predominantly serve local White British populations, there is evidence as social housing estates diversify that they have been able to engage with new demographics. In one case, on the inner-urban Eastmoor estate, for example, where the local school now has a body of pupils speaking 31 languages, two centre staff members are Kosovan and another is Polish. Engagement with the long-established and kinship-driven South Asian community, has been more challenging for the centre.

The relationship between local authorities and third sectors in Wakefield is shaped by relative success in securing monies from central Government ministries and national social development-style agencies. However, where funding flows into localities, voluntary sector groups often lack the infrastructure for managing paperwork heavy systems of bidding, delivery, and audit monitoring of the regeneration potential they bring. The extent to which these initiatives meet minority needs or support inter-ethnic community relations is variable because, in locations like Wakefield, BME (Black and Minority Ethnic) third sector representation can be limited (in the UK, the controversial term ‘BME’ is often used synonymously with ‘BAME’, meaning the slightly different ‘Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic’). There are also ironies in what happens to national funding. Controversial Government schemes, such as the anti-radicalisation ‘Prevent’ programme and the darkly titled ‘Controlling Migration Fund’, are often channelled into projects that would have perhaps been labelled ‘multicultural’ or ‘cohesion’ projects in the past. Two such examples may be cited in Wakefield.

Firstly, there is the Community Harmony project (£400,000 awarded). A two-year programme funded four areas of fine-grained work in the relatively superdiverse Eastmoor: environmental volunteering, youth engagement, inspection of HMOs and landlords, and ESOL (English Speakers of Other Languages). In one sub-district, known for having transient residents and environmental issues such as excessive littering and ‘fly-tipping’ of large household items, the scheme was successful in bringing together a tenants and residents association from an adjacent (majority white) neighbourhood with a local South Asian group. Where they normally tend to work solely in their parallel communities, in this case, they came together to run neighbourhood ‘clean ups’ in their respective areas. In the area of youth inter-cultural engagement, under the same ‘Community Harmony’ rubric, this proved a much harder task with a lack of pre-existing and credible spaces and clubs for young people undermining attempts at ‘integration’.

A second example from this programme can be found in Wakefield city centre. The growing Polish community in the district has been helped by an English language and community centre that has become an important go-between for all aspects of community relations in the district. Funded in part by Controlling Migration Fund money, it has played a key role informing Polish residents of their rights during the post-Brexit confusion. English language teaching and learning enables some social life and relates to building confidence when isolated residents face struggles with funding, bureaucracy and complex, shift-based, working lives – often in remotely located logistics firms, factories or agriculture. The centre runs on a shoe-string budget but if it survives long-term will form a vital link with a Polish population that is beginning to use mainstream services like a local community leisure centre for volleyball, floorball and football but which still tends to ‘shrink back’ into their diasporic communities.

In general, ESOL funding is tight, precarious and sometimes linked with the convening of community cohesion activities. Wakefield was able to secure an ESOL for Integration project (£223,000) for a one-year programme in 2020. This was narrated by the local authority in micro-local integration terms: ‘Introducing learners to local culture and local dialect, including the local Wakefield Trinity rugby league team, the fantastic pantomime at the Theatre Royal Wakefield, the joys of Yorkshire Puddings and the secrets of the Rhubarb Triangle’. In the rugby example, development workers took an ethnically mixed group of 40 people to see a Wakefield Trinity match. In this case, people tended to sit in pre-established groups with little mixing, but they noted the general value in such projects in drawing new migrant families into future services and programmes. Attracting new learners to their ESOL projects involves ongoing outreach and in summer 2020 workers set up an information space in a local mall. In this environment it was not uncommon to hear challenging comments from White British shoppers (e.g. ‘Oh, of course that is what the council are spending our money on’). Equally, however, the ESOL space offered somewhere for people of all backgrounds to sit and chat and have a cup of tea or coffee when a lot of the mall cafes had closed down. It is clearly painstaking work to develop such projects within tight funding envelopes and in a landscape of limited representation, territorial division and new and shifting patterns of migrant settlement.

Over in Halifax, the council seeks to manage inter-ethnic tensions through long-standing networks of ‘old heads’ representing different community interests, and a strong and well-established concentration of South Asian representation in the city. It also has infrastructural strengths as a district that are rooted in the emergency networks (‘Civil Contingency Emergency Planning’ and the ‘Emergency Partner Network’), involving all kinds of key stakeholders and local representatives, developed as a response to serious flooding along the Calder Valley. Despite austerity, the Council has refused to cut local community teams of social workers or centralise operations as they are in Wakefield. The research team first met local authority stakeholders and other community organisers at a well-publicised ‘stop hate crime’ event in Park Ward, that was seeking to pre-empt certain fears about extreme right mobilisation. The local police were centrally involved, and in discussions with them, they have been unusually concerned with this kind of radicalisation rather than the normal obsessive focus of ‘Prevent’ on radical Islam (on this, see Kapoor Citation2018). There has thus been much attention to mobilising against far-right activists that have attempted to get a foothold in poor majority White British communities: for example when the English Defence League attempted to organise a march.

The positive side of these efforts can be seen in the visibly deprived but lively heart of Park ward, which offers a clear variety of northern superdiversity. At the bustling and colourfully painted community centre, a longstanding team of social workers have built a trusted go-to location for residents – including quite transient new migrant families – that helps build bridges between White and BME groups. A group of old ladies – South Asian Muslim and White British – join up weekly to chat, cook or knit. They organise food bank charity work for a local mosque. The informal infrastructure here extends up into the council and a network of key local partners, involved for many years in managing the otherwise often sharp and difficult race relations in the town. South Asian representation is deeply ensconced in the local Labour Party, which helps maintains its political grip.

The other side of this concentration, however, is also apparent elsewhere. A well-placed stakeholder familiar with the local housing system told us that there is an informal housing association practice of placing South Asian and asylum seeker families in Park and not in majority White British estates, something that has been observed historically in the UK (Henderson and Karn Citation1987; Jeffers and Hoggett Citation1995; Watt Citation2021). Resources and attention follow. Some of the council services on housing and social entrepreneurship have been outsourced to third sector organisations, which now occupy the intermediary space of civil society connection. Social workers note the difficulties within these structures in connecting with very isolated residents. There has been a focus on door-knocking to track older men living alone and invite them to weekly discussion groups. The complaint of uneven resources across these different, albeit comparably poor, areas of the town, is a familiar refrain among some of the local third sector stakeholder voices. Across the other side of the valley to the north, there is a different sense of spatial isolation from the main town, in the areas of Ovenden and especially Mixenden, where a BNP councillor was elected in 2003. Local identification with place here is often resolutely insular and may centre on one or two public community spaces – a child-care centre, allotments or a local garden – or even a cafe in a (rare) supermarket. Short of shops and public transport, they are disconnected geographically from the centre by steep hills. Outreach here has sometimes been less effective than with the local South Asian population. There have been attempts to bring together older residents from the church and mosque organisations, but it is not always easy to create ‘conviviality’ across other divides. In discussions at a local church, a local church leader recounted to us some of the difficulties faced in putting on this kind of event. Food-oriented events help break the ice, but there were also arguments sparked over typical moments of inter-community tension. Apparently, there are quite often disputes about costs and payment for taxi rides with the local cab companies, that are run and staffed by South Asian drivers. Perhaps because of this flashpoint, the Council and its third sector figures in the South Asian community have focused on taxi drivers for training in emergency response during the COVID crisis, seeking to promote better community relations and communication.

Religious figures and organisations

Reaching out to churches and religious figures or organisations is, of course, a longstanding feature of localised British multiculturalism. As the state has ceded its presence in the difficult spaces of society, it has called upon these kinds of actors, bringing with it the well-established pitfalls of voluntarism (for example, relying on a cast of neighbourhood ‘usual suspects’, which risks individual ‘burn out’ and reinforcing unequal participation capacities – e.g. excluding those with caring responsibilities; see Wallace Citation2010, Humphris Citation2018). The drift of national policy, from the religion-based initiatives of Tony Blair's governments to David Cameron's ‘big society’ have made these governance structures ever more important. What is striking, though, in both the Wakefield and Halifax contexts, is how religious-based social work working in cooperation with local authorities has often sought to compensate for the negative effects of national policies and attitudes.

In Wakefield, it is churches which pick up much of the needed infrastructural work, in places where the council most lacks resources or on the ground connections – particularly in relation to the question of asylum. One church, not far from the refugee and asylum seeker ‘reception centre’ located dismally in the shadow of a large prison, provides basic social hours, access to language classes, and arts/craft sessions for families – with tea and biscuits always available. Wakefield have active City of Sanctuary networks that connect together disparate churches and communities and which are resourced by committed volunteers who offer support, guidance and sometimes a temporary home for people waiting for their asylum claims and appeals. The work has helped maintain a more positive image of refugee reception in the town, at a time when national political currents and analyses are encouraging the use of ‘hostile environment’ type political campaigning for supposedly ‘anti-immigrant’ red wall voters. This remains extremely precarious in the light of the negative local and national media attention generated by the outbreaks of illness within the reception centre during the COVID crisis.

The council has attempted to focus on positive examples of transition into the community, building on the church's work. In March 2020, at the city hall, the Wakefield Migrant Access Project celebrated its first 18 ‘graduates’ from a skills and communication programme designed to strengthen the ‘integration’ of community groups. The asylum and COVID emergency has enabled the Council and third sector locally to shift its practices to be more inclusive of minority group representation. There is now more outreach to local figures and organisations, including the relatively left behind ‘older’ British minority South Asian population, as well as the hard to find, small and dispersed older Black British community. New African migrants in the city meanwhile have been very proactive in setting up their own church based local organisations. A new (in this case) ‘BAME’ representative forum is finally being established and a more integrated minority strategy formulated by the district council.

In Halifax, asylum reception has been built on the existing structures of representation and community services concentrated in the Park ward area of the town. The community centre there plays a vital role in communicating with the marginalised group of Roma origin settlers arriving predominantly from the Czech Republic. Over at the Minster, in the town centre, there has been a strong emphasis on building a multi-ethnic congregation focusing on inclusion and cohesion – ironically under a large English St. George flag that often flutters on the church tower. Both councils are undoubtedly reliant on the role of mosques, Islamic educational organisations, and key prominent figures in the Muslim community to provide elements of informal infrastructure in spaces the local authorities cannot reach. An example of its importance came when the community erupted in anger at the last-minute imposition of a ban on Eid celebrations during the summer of 2020 after a surge in COVID cases. With this move, national government clumsily singled out Muslim family practices, highlighting marginalised areas of concentrated population, many of which were in the North. The local response was to double down on communication efforts via local religious figures and organisations, defusing any kind of sense of blame or targeting. Notably, local police have ignored the hard-line rhetoric of the national government and have adapted their interventions to emphasise first information and negotiation rather than punishment – for example, when they were called in, as was frequently the case, by White British residents complaining about the behaviour of large Muslim neighbour families. The most difficult challenges, reported by the Councils, has been communication over these rules with Roma community families. These are dispersed within the central town in Halifax; in Wakefield, there is a site on the edge of the city. The solution, once local intermediaries are found, is cascading information through social media such as Instagram, as well as focusing diligently on language translation – very much in distinction to the national level strategies of assimilatory ‘integration’ of marginal communities emphasised by the Casey report (Citation2016).

Among these key community individuals in the largely Pakistani-origin South Asian community, there are exceptional retired public sector figures, now engaged in full-time voluntary work, as well as younger entrepreneurial figures who have put themselves forward in representative roles, sitting on boards and local community advisory groups. As everywhere, there are tensions within the community between generations, in getting more women to come forward, and differences in political and ethical visions of Islam. But overall, in the many communities stretched out in the towns and cities along the M62 corridor, the political and community engagement belies the kind of conflictual and segregated image particularly associated with South Asians in the North of England, promoted by government studies on the ‘failure of integration’, and of the media-led moral panic around ‘grooming’ (of White teenage girls for prostitution by Asian gangs). The established South Asian presence is as much a part of Northern England as its post-industrial heritage and famous sports teams.

Arts and culture

At first sight, both Halifax and Wakefield seem ripe for the standard critique of gentrification and illusions of urban regeneration through culture (see Hatherley Citation2010; Keskiner and Waldring Citation2023 in this volume). We found no shortage of sarcastic local commentary about the overblown architecture of the contemporary art museum in Wakefield or criticism of the exclusive and high-end tourist shops, bars and cafes which fill the renovated Halifax Piece Hall. However, there are other aspects of the ‘creative culture’ environment fostered in the two locations that do have effects. One constant source of informal community infrastructure emerges from arts professionals working in hard-pressed communities. We found multiple examples of political or social engagement whilst at art school or as a practicing artist being converted into forms of community work that plug gaps in austerity-hit social programmes. We found key individuals of this kind in both locations, not only working in the obvious space of multicultural communication, but also frequently providing arts and culture-based services to difficult to reach marginal White British communities.

At a Methodist church in another of Wakefield city's sprawling, utilitarian, low end suburban housing estates, this time on the West side, we met with some local art workers, engaged in motivating a dance class for a mixed set of elderly mentally ill patients. These art workers are not untypical in an environment where eking out a living as a trained artist has become exceptionally difficult with cuts to arts budgets, limited jobs in schools and universities, and an institutional environment that has shifted emphasis from cultural to economic priorities in recent years. Their response – which we have heard from art workers in various locations – is to consciously choose to locate their domestic lives in the same neighbourhoods where they are trying to develop social projects. In this case, it translated into a particular investment in Agbrigg, a marginal and intensely concentrated deprived South Asian neighbourhood the south nestling behind Wakefield's largest cemetery and near its famous rugby league ground. Here, inclusion issues include problematic generational dynamics, and a lack of female representation in the local community organisations, that are centred on a mosque in a converted terrace row. The art workers have engaged with local women to bring them into discussions and public spaces that have created new points of contact in the community. Wakefield has a number of similar initiatives, often linked to alumni of the now defunct arts and performance college, Bretton Hall. Halifax has a small independent cultural scene centred around the Square Chapel venue but is less obviously endowed with avant-garde arts. However, it does have a socially minded community radio station which provides an important focus, animated by local arts figures. Volunteer DJs come in from around the community, with an emphasis on including people who have been through personal hardships, such as homelessness. The station caters mainly for an older White British population, with a nostalgic and populist orientation. Yet within its programming it also emphasises a positive political message, defining Halifax in terms of diversity and civic spirit. It has included a series of programmes, for instance, promoting the Black Lives Matter ethos and championing forgotten local histories. That black American jazz pianist ‘Champion Jack’ Dupree lived in the peripheral Halifax district of Ovenden in the 1970s and 1980s is a favoured vignette.

The role of walking tours, oral histories and archival work undertaken to reframe local histories and cultures and draw diverse residents into a shared history was also striking. Notable examples were found in Wakefield where the local civic society is running a walking history project with Pakistani children and a South Asian oral history project is inviting young people to interview older people, mainly from Kashmir. Northern Exposure's oral history archive will contribute to this emerging body of localised cultural knowledge. More traditional, but still vital, municipal museums and libraries, particularly their local branches, are often also a key part of local community work. Curators engage actively in questions raised by debates on multicultural inclusion, voice and participation, often converging with the practices of the socially engaged artists we met. In Halifax and Wakefield, the municipal library, museum and archives provide living legacy work, that reflects industrial heritage but is acutely aware of needing to update and present these collections for diversifying populations.

Conclusion

Since 2016 and the Brexit outcome, the post-industrial towns of Northern England have found themselves centre-stage in English political discourse. They are considered to be populated with ‘left behind’ – coded ‘White working class’ – Britons whose needs and values have been neglected by metropolitan elites for too long, triggering a search across the political spectrum for policy formulas to secure their electoral support. In a national political environment hostile to both immigration and multiculturalism, the rights and identities of migrants and minorities, where they show up in these discourses, have been further destabilised. The summer 2020 Black Lives Matter protests heralded a mainstream breakthrough for post-colonial and ‘critical race theory’ arguments, but these were faced down directly by Government ministers (Trilling Citation2020). A recent Government commission then staggeringly declared the UK clear of institutional racism and a ‘model for other white majority countries’ (Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities Citation2021). Undergird all this with more than a decade of fiscal austerity, there was a grim inevitability regarding the classed and racialised impacts of the British COVID-19 pandemic and its mishandling by Government (Office for National Statistics Citation2020; Public Health England Citation2020).

Northern Exposure has been positioned intellectually, methodologically and geographically to challenge myths and lacunae woven through the emergent post-Brexit political and cultural landscape, as well as academic discourses that sustain the dominant politics of the country. Our findings highlight constructive affinities with the BaM study, adding to its fine-grained sociological research on the ongoing negotiation of shifting majority-minority relations in postcolonial and /or ‘superdiverse’ Western European societies (see Crul et al. Citation2023 in this volume). Here, we have foregrounded the delicate, variable, predominantly informal ways in which public and community actors at the local level struggle to keep alive notions of ‘inclusion’, ‘diversity’ and ‘cohesion’. It is striking how accumulations of experience and expertise can sediment in localised networks which then try to support both mobile populations and address entrenched inequalities, attitudes and lifestyles. These in turn have been sedimented by industrial histories, awkward topographies, catastrophic planning (e.g. poor housing and transport infrastructure), low skill, low pay economies, and trends of disinvestment. Local stakeholders try to balance mobilities and flows with fixities and fractures. This is all within often dislocated spatial contexts that impact on populations in different ways. Through its work of co-production, Northern Exposure has played a modest role in staging new dialogues between these networks.

These infrastructural initiatives are imperfect, of course, and sometimes fail or have perverse effects. But they do invite a tentative hypothesis: that liberal democratic, postcolonial societies such as the UK have – via legacies of welfare provision and accumulated organising around waves of migration – and need – in order to build relations and resolve tensions – some vital social and human resources that have cohered over time. This establishes grounds for a normative policy agenda: that these local infrastructures should be supported by public resources, not just left to twist in the voluntarist wind. This, in turn, invites the obvious question of how such projects might be enhanced and actively defended. Such local infrastructures and interventions must in the UK contend with heavily centralised policy architecture and shrinking budgets, not to mention the ideological chauvinisms and boosterist agendas wrought by austerity and Brexit. In the meantime, if they are lucky, some of these locations and networks might secure a piece of the ‘levelling up’ pie. Without an honest, differentiated and multicultural account, however, this agenda will flounder and reproduce raced and classed inequalities within and across the North.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the UKRI ESRC funding ES/S007717/1, the Governance after Brexit programme led by Dan Wincott, and the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Leeds, for their support of the ‘Northern Exposure’ project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 These interviews gather the voices of elderly British South Asians, Black British Afro-Caribbeans, and White British residents of varied socio-economic background in specific localities within each town or city, together with other research on East European and refugee-migrant origin residents. The testimonies are cast in the long tradition of British oral history and social mobility research (e.g. Savage Citation2010; Lawrence Citation2019), reflecting both post-colonial diversity in the UK and recent worker migration flows (other inspirations include Miah et al Citation2020; Rogaly Citation2020). The residents narrate their lives and perceptions of long term social and urban change against the backdrop of ‘place’ and ‘locality’.

References

- Bagguley, P., and Y. Hussain. 2008. Riotous Citizens: Ethnic Conflict in Multicultural Britain. London: Routledge.

- Barbulescu, R., A. Favell, O. Khan, C. Paraschivescu, R. Samuel, and A. Varela. 2019. Class, Race and Inequality in Northern Towns. London: Runnymede Trust.

- Benson, M. 2019. Class, Race, Brexit. Discover Society. October 2. https://discoversociety.org/2019/10/02/focus-class-race-brexit/?fbc.

- Bhambra, G. 2017. “Brexit, Trump, and ‘Methodological Whiteness’ on the Misrecognition of Race and Class.” British Journal of Sociology 68 (1): 214–232. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12317.

- Cantle, T. 2001. Community Cohesion: A Report of the Independent Review Team (the Cantle Report). London: HMSO.

- Casey, L. 2016. The Casey Review: A Review into Opportunity and Integration. London: Department for Communities and Local Government.

- Commission on Racism and Ethnic Disparities. 2021. The Report of the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-report-of-the-commission-on-race-and-ethnic-disparities.

- Crul, M., F. Lelie, E. Keskiner, L. Michon, and I. Waldring. 2023. “How do People Without Migration Background Experience and Impact Today’s Superdiverse Cities?” Journal of Ethnic of Migration Studies 49 (8): 1937–1956. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2182548.

- Cummings, R. 2020. “‘Ain’t No Black in the (Brexit) Union Jack? Race and Empire in the era of Brexit and the Windrush Scandal’.” Journal of Postcolonial Writing 56 (5): 593–606. doi:10.1080/17449855.2020.1815972.

- Curtice, J. 2017. “Why Leave won the UK’s EU Referendum.” Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (Annual Review): 19–37. doi:10.1111/jcms.12613.

- Eatwell, R., and M. Goodwin. 2018. National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy. London: Pelican.

- The Economist. 2021. "The Red wall Reconsidered: The Truth Behind the Tories’ Northern Strongholds." 3 April.

- Evans, G., and J. Tilley. 2017. The New Politics of Class: The Political Exclusion of the British Working Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Favell, A. 1998. Philosophies of Integration: Immigration and the Idea of Citizenship in France and Britain. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Favell, A. 2020. “Crossing the Race Line: ‘No Polish, No Blacks, No Dogs’ in Brexit Britain? Or, the Great British Brexit Swindle.” Research in Political Sociology 27: 103–130. doi:10.1108/S0895-993520200000027012.

- Ford, R., and M. Goodwin. 2014. Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support for the Radical Right in Britain. London: Routledge.

- Ford, R., and M. Goodwin. 2017. “A Nation Divided.” Journal of Democracy 28 (1): 17–30. doi:10.1353/jod.2017.0002.

- Gest, J. 2016. The New Minority: White Working Class Politics in an Age of Immigration and Inequality. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gilroy, P. 2004. After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture. London: Routledge.

- Goodhart, D. 2017. The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics. London: Hurst.

- Gray, M., and A. Barford. 2018. “The Depths of the Cuts: The Uneven Geography of Local Government Austerity.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (3): 541–563. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsy019.

- Grayson, J. 2020. Like a Prison: Discussions with People Inside Urban House Initial Accommodation Centre, Wakefield. https://irr.org.uk/article/like-a-prison-discussions-with-people-inside-urban-house-initial-accommodation-centre-wakefield/.

- Guilluy, C. 2014. La France périphérique: comment on a sacrifié les classes populaires. Paris: Flammarion.

- Hanretty, C. 2021. “The Pork Barrel Politics of the Towns Fund.” Political Quarterly 92 (1): 7–13. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.12970.

- Hansard. 2015. “Devolution and Growth across Britain.” Record of Debate. Vol. 596, Weds 3 June 2015. https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2015-06-03/debates/15060324000002/DevolutionAndGrowthAcrossBritain [Jo Cox speech transcribed at 5:35 pm].

- Hatherley, O. 2010. A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain. London: Verso.

- Henderson, J., and V. Karn. 1987. Race, Class and State Housing: Inequality and the Allocation of Public Housing in Britain. Aldershot: Gower.

- Hobolt, S. 2017. “The Brexit Vote: A Divided Nation, a Divided Continent.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (9): 1259–1277. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785.

- Hochschild, A. 2016. Strangers in Their Own Land. New York: The New Press.

- House of Commons Library. 2020. Hate Crime Statistics. UK Parliament. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8537/.

- Humphris, R. 2018. “Mutating Faces of the State? Austerity, Migration and Faith-Based Volunteers in a UK Downscaled Urban Context.” The Sociological Review 67 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1177/0038026118793035.

- Jeffers, S., and P. Hoggett. 1995. “Like Counting Deckchairs on the Titanic: A Study of Institutional Racism and Housing Allocations in Haringey and Lambeth.” Housing Studies 10 (3): 325–344. doi:10.1080/02673039508720824.

- Jennings, W., and G. Stoker. 2016. “The Bifurcation of Politics: Two Englands.” The Political Quarterly 87 (3): 372–382. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.12228.

- Jones, H. 2015. Negotiating Cohesion, Inequality and Change: Uncomfortable Positions in Local Government. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Jones, H. 2019. “More in Common: The Domestication of Misogynist White Supremacy and the Assassination of Jo Cox.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (14): 2431–2449. doi:10.1080/01419870.2019.1577474.

- Kapoor, N. 2018. Deport, Deprive, Extradite: On Twenty-First Century State Extremism. London: Verso.

- Kaufmann, E. 2018. Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities. London: Allen Lane.

- Kaufmann, E. 2020. “The Great Awokening and the Second American Revolution.” Quillette [online], 22 June. https://quillette.com/2020/06/22/toward-a-new-cultural-nationalism/.

- Keskiner, E., and I. Waldring. 2023. “Revisiting the Established-Outsider Constellation in a Gentrifying Majority-Minority Neighbourhood.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (8): 2052–2069. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2182554.

- Koopmans, R., and L. Orgad. 2020. “Majority-Minority Constellations: Towards a Group Differentiated Approach.” Discussion Paper SP VI 2020–104. Berlin: WZB.

- Kraus, L. 2023. “Beyond Appreciation and Rejection: Reactions of Europeans Without a Migration Background to Being an Ethnic Minority.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (8): 1957–1976. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2182549.

- Lawrence, J. 2019. Me, Me, Me: The Search for Community in Post-war England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- MacLeod, G., and M. Jones. 2018. “Explaining ‘Brexit Capital’: Uneven Development and the Austerity State.” Space and Polity 18 (2): 111–136. doi:10.1080/13562576.2018.1535272.

- Maikin-Waite, M. 2021. On Burnley Road. Class, Race and Politics in a Northern English Town. Chadwell Heath: Lawrence and Wishart.

- McQuarrie, M. 2017. “The Revolt of the Rust Belt: Place and Politics in the age of Anger.” British Journal of Sociology 68 (S1): 120–152. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12328.

- Miah, S., P. Sanderson, and P. Thomas. 2020. ‘Race,’ Space and Multiculturalism in Northern England. London: Palgrave.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). 2020. Coronavirus and the Social Impacts on Different Ethnic Groups in the UK: 2020. London: ONS.

- Parekh, B., et al. 2000. Report of the Commission on the Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain (the Parekh Report). London: Runnymede Foundation.

- Public Health England. 2020. Disparities in the Risk and Outcomes of COVID-19. London: PHE Publications.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2017. “The Revenge of the Places That Don’t Matter (and What to do About It).” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (1): 189–209. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx024.

- Rogaly, B. 2020. Stories from a Migrant City: Living and Working Together in the Shadow of Brexit. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Savage, M. 2010. Identities and Social Change in Britain Since 1940. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schut, J., and I. Waldring. 2023. “Micro Labour, Ambivalence and Discomfort: How People Without a Migration Background Strategically Engage with Difference in a Majority–Minority Neighbourhood.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (8): 2034–2051. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2182553.

- Sobolewska, M., and R. Ford. 2019. “British Culture Wars? Brexit and the Future Politics of Immigration and Ethnic Diversity.” Political Quarterly 90 (S2): 142–154. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.12646.

- Sobolewska, M., and R. Ford. 2020. Brexitland: Identity, Diversity and the Reshaping of British Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Trilling, D. 2020. Why is the UK Government Suddenly Targeting ‘Critical Race Theory’? https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/oct/23/uk-critical-race-theory-trump-conservatives-structural-inequality.

- Wallace, A. 2010. Remaking Community? Abingdon: Routledge.

- Watt, P. 2021. Estate Regeneration and its Discontents. Bristol: Policy Press.