ABSTRACT

The fastest growing ethnoracial group in the United States, Asian Americans are the most highly educated, the highest earning, and the most likely to intermarry. Once deemed diseased, morally deviant, unfit for citizenship, and unassimilable, Asian Americans have attained unprecedented racial mobility, now boasting socioeconomic outcomes that surpass those of native-born Whites. Their attainment has led some social scientists to conclude that Asians are rapidly assimilating into American mainstream and remaking it in the process. While Asian American attainment defies theories of racial disadvantage, their experiences with xenophobia, racism, and anti-Asian violence vex theories of assimilation – pointing to an assimilation paradox. At no recent time has the paradox become more apparent than during COVID-19 pandemic. We maintain that the paradox reflects three tensions: the ahistorical nature of sociologists’ research on Asian American assimilation; the tautology of using educational attainment acquired from immigrants’ countries of origin as a measure of structural assimilation in their country of destination; and the disjuncture between the way sociologists normatively measure assimilation and the way ethnoracial minorities experience it. By integrating legacies of exclusion into theories of Asian American assimilation, addressing the tautology, and incorporating a subject-centered approach into empirical measures, we advance theory and research, and reclaim narratives of Asian American assimilation.

Introduction

The fastest growing ethnoracial racial group in the United States, Asian Americans increased from 0.6 percent of the county’s population in 1960 to 7.2 percent today. Between 2000 and 2019 alone, the U.S. Asian population grew by 81 percent (Shimkhada and Ponce Citation2022). Unlike other groups, including Hispanics, that are growing mainly through natural births, the U.S. Asian population is growing primarily through immigration (Lee and Ramakrishnan Citation2021). China and India have long surpassed Mexico as the leading sources of new immigrants to the United States, and by 2055, Asians will surpass Hispanics as the largest immigrant group in the country (Colby and Ortman Citation2015). Three in five Asians in the United States are immigrants – a figure that increases to four in five among adults – and nine in ten are either immigrants or the children of immigrants. The new face of U.S. immigration is Asian, making the study of Asian Americans essential to theory and research on assimilation.

Diversity is a hallmark of the U.S. Asian population whose origins span ‘the Far East, Southeast Asian, or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam’ (Office of Management and Budget Citation1997). Despite their diversity in origins, Asian Americans are, on average, the most highly educated, the highest earning, and the most likely to intermarry of all U.S. ethnoracial groups. More than one-quarter are interracially married, and among the U.S.-born, the share is nearly double that (Pew Research Center Citation2017). And at $101,481, their median household income surpasses that of non-Hispanic Whites ($77,999), Hispanics ($57,981), and Blacks ($48,297) (U.S. Census Bureau Citation2022). Based on normative measures, Asians have not only successfully assimilated into the American mainstream, but they are remaking it in the process (Alba and Nee Citation2003).

By assimilation, U.S. sociologists refer to a two-sided process by which the characteristics of members of immigrant groups and host societies come to resemble one another, marked by the decline of ethnoracial distinction. Sometimes described as integration or incorporation, the process of assimilation – which has both economic and sociocultural dimensions – begins with immigrants and continues through the second generation and beyond (Brown and Bean Citation2006). According to Alba (Citation2020), a key component of this process is ‘decategorization’ in which ethnoracial distinctions decline in significance such that individuals who come from different sides of an ethnoracial boundary – one majority, one minority – no longer commonly think about or treat each other based on their categorical memberships.

The socioeconomic attainment of Asian Americans in the twenty-first century is remarkable in light of their racial status in the nineteenth. Once deemed filthy, diseased, sub-human, and unassimilable, Asians were denied the rights of citizenship and endured a series of exclusion laws that choked immigration and the growth of the U.S. Asian population. When the United States finally abolished national origins quotas with the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, it opened the door to a new wave of Asian immigrants. By privileging the professionally skilled, the change in U.S. immigration law legally engineered a new stream of highly educated Asian immigrants into the United States, thereby elevating the racial status of Asian Americans from ‘unassimilable to exceptional’ (Lee Citation2021).

Today, the majority of contemporary Asian immigrants are doubly positively selected, or what Lee and Zhou (Citation2015) describe as hyper-selected: they are not only more likely to be college-educated than their non-migrant counterparts from their countries of origin, but they are also more highly educated than the U.S. mean. Their hyper-selectivity places them and their U.S.-born children at favourable starting points in the quest to get ahead (Hsin Citation2016; Hsin and Xie Citation2014; Lee and Zhou Citation2015, Citation2017; Tran, Lee, and Huang Citation2019, Citation2018). While their hyper-selectivity has advanced the status of Asian Americans, their racial mobility has not shielded them from the surge in anti-Asian violence and hate incidents that has touched one in six adults since the wake of COVID-19 (Lee and Ramakrishnan Citation2022; Wong and Ramakrishnan Citation2021).

Asian Americans’ racial mobility defies theories of racial disadvantage yet their experiences with xenophobia, racism, and anti-Asian violence vex theories of assimilation – pointing to an assimilation paradox. We address the paradox by making three distinct but interrelated arguments. The first is theoretical, and reflects the ahistorical nature of sociological research of Asian American assimilation. Because most contemporary studies of Asian immigration and ‘the new second generation’ focus on those who arrived after 1965, most sociologists begin with the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act as the legal foundation for Asian immigration to the United States.

Absent from the sociological corpus of research is the fraught history of Asians in the United States, including a legacy of exclusion, which began in the nineteenth century, extended into the twentieth, and continues to affect the experiences, sense of belonging, and group position among Asian Americans in the twenty-first. Most Americans are unfamiliar with the laws of exclusion that barred Asians from immigrating and denied them citizenship, yet the stereotypes that emerged from this legacy are very familiar: Asians are foreign and un-American, and in times of crisis, they should go back to where they came from – a racist, xenophobic taunt leveled at nearly one in three Asian American adults during the pandemic. Integrating the history of Asian America into theories of assimilation is foundational to addressing the paradox.

Second, because the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act became the legal foundation for research on contemporary Asian immigrants – who are, on average, highly educated and hyper-selected – social scientists failed to question the tautology of using educational attainment acquired from an immigrant’s country of origin as a measure of their structural assimilation in their country of destination (see Zeng and Xie Citation2004).

This brings us to our third point, which is empirical. The paradox also stems from the tendency of sociologists to rely almost exclusively on normative indicators to draw conclusions about assimilation. We address this bias by adopting a subject-centered approach that places the subjects’ experiences, sense of belonging, and views of their group position at the centre of our analyses (see also Fernández-Kelly Citation2020; Jimenez et al. Citation2021; Portes, Aparicio, and Haller Citation2016). Drawing on findings from nationally representative surveys of the U.S. Asian population fielded during the COVID-19 pandemic, we find that normative measures alone provide a skewed portrait of Asian American assimilation. By shifting the frame to privilege the voices of the populations we study (Duneier Citation1999, Citation1992; Lamont Citation2000), we learn that the overwhelming majority of Asian Americans do not feel that they completely belong and are accepted in the United States. Moreover, despite claims that Asian Americans are ‘honorary Whites’ to borrow Bonilla-Silva’s (Citation2004) term, the majority identify as people of colour, and view their status as more similar to people of colour than to Whites by a margin of three-to-one.

The project of Asian American assimilation has assumed a moral urgency during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has made anti-Asian violence more frequent, and anti-Asian racism more visible. Three in four Asian American adults worry at least sometimes about being victimised because of their race, and one in three has changed their daily routines because of the worry. By integrating the history of Asian America into theories of assimilation and incorporating a subject-centered approach in our empirical measures, we challenge oft-held assumptions and enable Asian Americans to reclaim their narratives.

A legacy of Asian exclusion

The national origin groups subsumed under the U.S. Asian category do not fully correspond with the geographic scope of Asia, nor do they share a common ethnicity, language, culture, or religion. What they do share, however, is legacy of exclusion (Lee and Ramakrishnan Citation2021). Highlighting key federal legal decisions, we show how this legacy has taken two distinct but interrelated forms in the United States: exclusion from citizenship and exclusion from immigration.

Racial difference and exclusion from citizenship

Birthright citizenship has been a right of U.S.-born free White men since the country’s founding, with the privilege extended to the foreign-born with the Naturalization Act of 1790. Accordingly, ‘any Alien being a free white person’ who had lived in the United States for two years and could prove he was ‘a person of good character’ would be granted the rights of citizenship. With the ratification of the fourteenth amendment in 1868, citizenship was extended to persons of African nativity and descent. Notably, persons of Asian nativity and descent were not included (Haney López Citation1996). Consequently, Asians in the United States were deprived of protections from the state, ineligible to vote, forbidden to testify in court, and, in many states, prohibited from owning property through alien land laws (Colbern and Ramakrishnan Citation2020).

Two landmark Supreme Court cases in the 1920s challenged the Naturalization Act: Ozawa v. United States in 1922; and United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind in 1923. In each, the appellants advanced different racial logics about why Asians should be eligible for naturalisation. In the first case, Japanese-born Takao Ozawa challenged the definition of a ‘free white person’ by arguing for its expansion. He offered socioeconomic indicators of his assimilation as justification. Having graduated from high school in Berkeley, Ozawa continued his education at the University of California for three years. Not only was he educated in the United States, but his U.S.-born children were too. He lived continuously in the United States for twenty years, his family spoke English at home, and they attended American – rather than Japanese – churches. Apart from these markers of assimilation, Ozawa argued that his skin colour was lighter than that of some Europeans such as those from Mediterranean countries (Haney López Citation1996; Sohoni Citation2007).

‘In name, I am not an American, but at heart I am a true American,’ Ozawa presented to the Court.

His markers of assimilation would become irrelevant, however. The Supreme Court did not dispute Ozawa’s good character, yet they ruled that he was ineligible for citizenship, nevertheless. Ozawa was Japanese, which was ‘clearly of a race which is not Caucasian’ and was therefore not ‘white’. Skin colour was an impractical test of Whiteness, the court added, given its variation even among people within the same race. Falling outside the racial borders of Whiteness, Ozawa fell outside the borders of citizenship (Carbado Citation2009).

In the following year, appellant Bhagat Singh Thind sought to naturalise after having served in the United States Army during World War I. Born in Punjab, Thind was Sikh, identified as Aryan, and argued that Aryans are part of the Caucasian race. In Thind’s case, the Supreme Court reasoned that regardless of scientific speculations, ‘free white persons’ and ‘Caucasian’ are words of common speech, to be interpreted in accordance with the understanding of the common man.

Describing Thind as Hindu in their documents, the court reasoned that, ‘It may be true that the blond Scandinavian and the brown Hindu have a common ancestor in the dim reaches of antiquity, but the average man knows perfectly well that there are unmistakable and profound differences between them today.’ Unlike the children of English, French, German, Italian, Scandinavian, and other European heritage who lose the hallmarks of their ancestry, the children of Hindu origin indefinitely retain evidence of theirs, thereby rendering them distinct from persons commonly recognised as White. Wary not to suggest that Hindus were racially inferior to Whites, the Supreme Court focused instead on their ‘racial difference’ from Whites, thereby arguing the impossibility of assimilation:

It is very far from our thought to suggest the slightest question of racial superiority or inferiority. What we suggest is merely racial difference, and it is of such character and extent that the great body of our people instinctively recognize it and reject the thought of assimilation.

Exclusion from citizenship was inextricably linked to exclusion from immigration. When Congress limited immigration from Asia in 1917 by creating an Asiatic Barred Zone that stretched from Korea to British India, this gave the Supreme Court yet another reason to deny Ozawa and Thind citizenship. How could the United States accept as its citizens the very people it had rejected as immigrants?

Immorality and exclusion from immigration

No federal laws existed to restrict immigration to the United States until March 3, 1875 when President Ulysses Grant signed the Page Act into law. Prohibiting the recruitment of labourers from ‘China, Japan or any Oriental country’ who were not brought to the United States of their own will or who were brought for ‘lewd and immoral purposes,’ the Page Act targeted Chinese women, in particular (Abrams Citation2005; Calavita Citation2006; Curry Citation2021; Luibhéid Citation2002). While immigration scholars often mark the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 as the first federally restrictive immigration law, this ignores the lesser known Page Act that became law seven years prior. In addition, by focusing on the presumed economic threat posed by Chinese male labourers, sociologists have paid scant attention to claims of the medical and moral threat posed by Chinese women (C. Lee Citation2010). The Page Act marked the beginning of decades of restrictive policies based on race, national origin, and immigrant selectivity that laid the blueprint for Asian exclusion, which would, in turn, define and redefine Asian America.

While approximately 250,000 Chinese immigrated to the United States when they first arrived during the Gold Rush from 1850 to 1882, Chinese women never comprised more than 7.2 percent of the U.S. Chinese population (Chan 1999; Hirata Citation1979). Despite their small numbers, they would be deemed medical and moral threats who needed to be expunged (Craddock Citation1999; Luibhéid Citation2002; Matsubara Citation2003; Risse Citation2015; Shah Citation2001; Trauner Citation1978). Singling out Chinese prostitutes, leading physicians in San Francisco painted them as vectors of a unique strain of syphilis that failed to respond to therapy. The ‘virus of the coolie’ or ‘Chinapox’ proved almost incurable, especially for young, White boys, they claimed.

For example, in his presidential address to the American Medical Association, J. Marion Sims warned about a ‘Chinese syphilis tocsin’ that reached epidemic proportions because of the ‘cheap’ sexual favours doled out by Chinese prostitutes to young White men – and alarmingly to White boys as young as ten and eight. Sims pronounced that young boys were being ‘spyhilized by these degraded wretches’ whose ‘presence breeds moral and physical pestilence.’ He drew on the testimony of the prominent San Francisco physician and member of the city’s Board of Health, Dr. Hugh H. Toland, who testified before the San Francisco legislature that he was treating half a dozen young boys a day. Nine-tenths of the cases were attributable to Chinese prostitutes, Toland claimed, further enumerating that ‘in nine cases out of ten it is the ruin of them.’ ‘The whole system becomes poisoned and debilitated,’ Toland elaborated, ‘that they cannot be cured.’

A master orator, Toland incited fear by not only racializing an incurable strain of syphilis, but also pointing to young White boys as innocent victims and to Chinese prostitutes as immoral vectors, ‘I have seen boys eight and ten years old with diseases they told me they contracted on Jackson Street. It is astonishing how soon they commence indulging in that passion. Some of the worst cases of syphilis I have ever seen in my life occur in children not more than ten or twelve years old.’ Linking disease with race, place, gender, and moral bankruptcy, Toland concluded,

I am satisfied, from my experience, that nearly all the boys in town, who have venereal disease, contracted it in Chinatown. They have no difficulty there, for the prices are so low that they can go whenever they please. The women there do not care how old the boys are, whether five years old or more, as long as they have money.

It is worth noting that physicians like Sims, Toland, and Shorb did not target prostitution per se since they recognised the function that it served for single male labourers in a port city like San Francisco. Nor did they focus on White prostitutes who far outnumbered their Chinese counterparts. According to the Chief of Police, ‘white women would not allow boys of ten, eleven, or fourteen years of age to enter their houses,’ unlike ‘Chinese prostitutes [who] … initiate [boys] into the ways of lewdness.’ The Chief of Police elaborated about White prostitutes, their ‘prices are higher and boys of that age will not take the liberties with white women that they do in Chinatown.’ According to their logic, the higher prices and higher morals – rather than the higher group position of White prostitutes that enabled them to charge higher prices – absolved White prostitutes from being medically deigned as the immoral, syphilitic prostitute.

Dr. Arthur B. Stout was a dissenter among those who testified before the legislature. White boys did visit Chinatown, Stout agreed, but most were hoodlums determined to cause mischief rather than seek cheap sexual favours. ‘The statement that the morality of our White boys is influenced by going among the Chinese is a gross exaggeration,’ reducing it to ‘nonsense.’ More realistically, Stout argued, blame should shift to White prostitutes who vastly outnumbered their Chinese counterparts. But Stout’s disconfirming testimony stood alone, while Toland’s became the master narrative, reaffirmed by his colleagues, and reproduced for decades.

By linking disease with sexuality, binding immorality with race, and then personifying these contagions into the bodies of Chinese women, science and medicine helped to justify the racial foundations for Chinese exclusion. When President Ulysses Grant called for legislation against Chinese women who are ‘brought for shameful purposes, to the disgrace of the communities where settled and to the great demoralisation of the youth of these localities,’ Representative Horace Page of California responded. Drawing on the poor immigrant selectivity of Chinese women, Page pronounced that because China ‘insist[ed] on sending here none but the lowest and most depraved of her subjects,’ America was becoming ‘her cesspool.’ Page declared that his bill would ‘place a dividing line between vice and virtue, and send the brazen harlot who openly flaunts her wickedness in the faces of our wives and daughters back to her native country.’

In an otherwise era of open borders, Chinese women had to submit ‘an official declaration of purpose in emigration and personal morality’ statement, and also had to endure a series of exhaustive and humiliating interrogations before they were permitted to board ship (Abrams Citation2005; Calavita Citation2006; Chan Citation2009; Luibhéid Citation2002). With little immigration from other Asian countries at the time, the Page Act effectively targeted Chinese women without expressly doing so by constructing what Park (Citation2019) describes as a ‘federal individual deportation system.’

The genius of the Page Act is that it placed the burden on Chinese women to prove a negative – that is, prove that they were not prostitutes. The success of the Page Act is reflected in the dramatic reduction of Chinese immigrant women from several hundred per month to about fifteen in three months (Peffer Citation1986), further skewing the gender ratio of Chinese men to women which was already 14 to 1 in 1870 before the Page Act, to 21 to 1 in 1880, and 27 to 1 by 1890.

Moreover, by excluding Chinese women, the Page Act suppressed not only the growth of the U.S. Chinese population, but also the birth of Chinese American population (Abrams Citation2005). While Chinese immigrants were denied citizenship, after the ruling of United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), the children of Chinese immigrants would be Americans citizens. Hence, by excluding Chinese women, the federal government severed Chinese reproduction and family formation, and stunted the growth of a Chinese American population. The consequences are still felt today: fewer than 10 percent of Chinese Americans can trace their lineage back three generations (Lew-Williams Citation2018).

The Page Act also created the precedent for decades of restrictive policies, including the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which was renewed and expanded in 1884, 1888, and 1892 (Curry Citation2021; E. Lee Citation2002, Citation2003; Lew-Williams Citation2018; Luibhéid Citation2002; Ngai Citation2004, Citation2021; Salyer Citation1995). These were followed by the Gentleman’s Agreement with Japan in 1907 which dramatically reduced immigration from Japan, and the Asiatic Barred Zone in 1917 that stretched from Korea to British India, thereby banning immigration from virtually all of Asia. When Congress amended the Immigration Act in 1924, it barred all ‘alien[s] ineligible for citizenship,’ thereby cementing the relationship between immigration and citizenship. And by establishing a national origins quota at 2 percent of the total number of individuals from each nationality that resided in the U.S. in 1890, the United States effectively sealed the door to Asian immigration.

Not until World War II when China became an ally to the United States was the Chinese Exclusion Act repealed, underscoring the role of geopolitics in extending rights to Asians in the United States. The Magnuson Act of 1943 allowed a small number of Chinese immigrants already residing in the United States to naturalise, with the Luce-Celler Act of 1946 lifting restrictions on Filipinos and Asian Indians (Lee and Ramakrishnan Citation2021). Naturalisation for all U.S. Asians would not come for nearly a decade later in 1952 when geopolitical incentives pushed the federal government to extend the right to naturalise for Asians in the United States (Wu Citation2014).

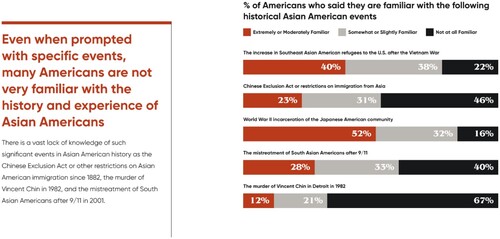

Most Americans are unfamiliar with the laws of exclusion that barred Asians from immigrating and denied them citizenship: 42 percent cannot think of a single policy or experience related to Asian Americans. Even when prompted, 46 percent admit that they do not know about the Chinese Exclusion Act or other restrictions on Asian immigration, as shows. While many Americans are unfamiliar with this history, the stereotypes that were born of it are very familiar: Asians are foreign, un-American, and alien. Integrating the history of Asian America into theories of assimilation is foundational to understanding the experiences of Asian Americans, and addressing the assimilation paradox.

The legal engineering of hyper-selectivity and a tautology

Against the backdrop of decades of exclusion and geopolitical exigencies, the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act was a watershed moment for Asian immigration. By abolishing the national origin quotas that had choked Asian immigration and suppressed the growth of the U.S. Asian population, the change in immigration law opened the door to a new wave of Asian newcomers. And by creating new preferences based on professional skills, it privileged the highly educated and highly skilled, including physicians, nurses, scientists, and engineers. Hence, the change in U.S. immigration law legally engineered Asian immigrant hyper-selectivity – that is, immigrants who are not only more likely to have graduated from college than their nonmigrant counterparts in their countries of origin but also more likely to hold a college degree than the U.S. mean (Lee and Zhou Citation2015).

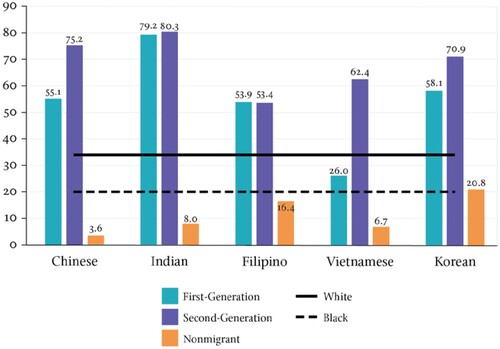

By illustration, as shows, of the five largest U.S. Asian groups that account for 83 percent of the Asian American population – Chinese, Indians, Filipinos, Vietnamese, and Koreans – all but Vietnamese are hyper-selected (Tran, Lee, and Huang Citation2019). Among Chinese – the largest U.S. Asian group – 55 percent of immigrants have a B.A. or higher compared to only 3.6 percent of China’s non-migration population, meaning that Chinese immigrants in the United States are 18 times more likely to have graduated from college than their non-migrant counterparts in China. The second largest U.S. Asian group, Indians are the most highly educated: 79 percent of Indian immigrants in the U.S. holds a B.A. or higher compared to only 8 percent of India’s population, indicating that U.S. Indian immigrants are 10 times more likely to be college-educated than their non-migrant counterparts in India. Among the top five Asian immigrant groups in the United States, all are more likely to have graduated from college compared to their non-migrant counterparts from their countries of origin. In addition, all but Vietnamese (the only refugee group among the top five) are also more highly educated than the general U.S. population.

Figure 2. Percent of First– and Second-Generation Asians and their Nonmigrant Counterparts to Graduate from College. Source: Van C. Tran, Jennifer Lee, and Tiffany J. Huang. ‘Revisiting the Asian Second-Generation Advantage.’ Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (13) (2019): 2248–2269.

Social scientists have pointed to the direct and spillover effects of Asian immigrant hyper-selectivity for both immigrants and the U.S.-born second generation (Fernández-Kelly Citation2016; Hsin Citation2016; Hsin and Xie Citation2014; Lee 2021; Lee and Zhou Citation2015; Tran, Lee, and Huang Citation2019; Warikoo Citation2022). That hyper-selected immigrants arrive in the U.S. armed with high levels of human capital from their countries of origin gives them and their U.S.-born children an edge over hypo-selected immigrant groups like Mexicans (Diaz and Lee Citation2020), as well as native-born Whites and Blacks in the domain of education (Drake Citation2022; Shi and Zhu Citation2023). Based on measures such as educational attainment, neo-assimilationists have argued that Asian Americans are not only entering the mainstream but also remaking it in the process.

Here, we make our second argument about the assimilation paradox by pointing to the flawed logic of using indicators like college degrees acquired from Asian immigrants’ countries of origin as a direct measure of their structural assimilation in their country of destination (Zeng and Xie Citation2004). Altogether absent is the recognition of the tautology, and how it, in turn, produces biased narratives of assimilation among hyper-selected Asian immigrant groups. The absence of the recognition stems, in part, from sociologists’ reliance on models built on the European immigrant experience of intergenerational mobility to explain the assimilation trajectories of contemporary U.S. immigrants who are largely non-European and racialized as non-White.

The epistemological gap between normative and subject-centered approaches to assimilation

Conceived of the Eurocentric project of U.S. nation building, Milton Gordon’s (Citation1964) model of assimilation laid out seven dimensions: cultural or behavioural (change of immigrant cultural patterns); structural (immigrants’ entrance into major institutions and social groups); marital (intermarriage); identificational (immigrant self-identification); attitude receptional (lack of native prejudice); behavioural receptional (lack of native discrimination); and civic (lack of intergroup conflict). While identifying discrete dimensions, Gordon stipulated that structural assimilation was a pre-condition to subsequent forms of assimilation. Greater institutional and social exposure across groups will lead to marital assimilation and multiracial offspring who, in turn, contribute to the blurring of group boundaries. The role of intermarriage, according to Gordon, lies in its transitional power to diminish the minority-distinctive characteristics through mixed-race descendants, thereby erasing racial differences. Although the process is linear, Gordon recognised that immigrants were not only changed by America’s ‘core culture’ but were also changing it in the process.

Neo-assimilation theories advanced by Alba and Nee (Citation2003) and Alba (Citation2020) similarly point to the decline of ethnoracial distinctions and their corollary waning of cultural and social differences as markers of assimilation. Positing that today’s immigrants and their children are assimilating much like the European immigrants of yore, neo-assimilations argue that immigrant newcomers are transforming and expanding the boundaries of the U.S. mainstream as European immigrants and their descendants have in the past. Where they diverge from Gordon is their concept of what constitutes America’s core culture or mainstream: Gordon points to White Protestant cultural dominance, whereas Alba (Citation2020) argues for an expanded mainstream that encompasses working– to upper-class Whites as well as middle– and upper-class Asians and Hispanics.

The assimilation of the latter groups occurs as highly skilled immigrants and their U.S.-born children gain entrée into the upper echelon of the professional labour market. Structural assimilation, in turn, paves the way for intermarriage and the growth of the multiracial population, yoking together ethnoracial boundaries until racial difference disappears. Absent from both Gordon’s (Citation1964) and Alba’s (Citation2020) reasoning, however, is that this logic rests on the obfuscation of racial difference rather than the insignificance of racial difference.

Yet another critique of the neo-assimilation model is the vague and expansive definition of the mainstream. ‘When ‘mainstream’ can signify anything from the upper-class to the minority poor, and assimilation may or may not happen across generations, there is little heuristic power left in the theory’ (Haller, Portes, and Lynch Citation2011, 736). According to Haller, Portes, and Lynch (Citation2011), the sheer ambiguity of who is included in the mainstream makes the very notion of it theoretically ineffective. More analytically useful, they contend, is assessing into which segment of U.S. society immigrants and their descendants are assimilating.

Observing the trajectories of the children of Haitian, Cuban and West Indian immigrants, Portes and Zhou (Citation1993) outlined bifurcated paths of assimilation. Noting that the post-1965 U.S. labour market is characterised by polarised skill levels and compensation, they maintain that the path of assimilation into the middle-class traveled by European immigrants is no longer the sole trajectory, but, rather, one of several (see also Haller, Portes, and Lynch Citation2011; Portes, Fernández-Kelly, and Haller Citation2005, Citation2009; Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001; Zhou Citation1997). While some achieve middle-class status, other immigrants and their descendants experience racialisation and assimilate downward into impoverished native groups (see also Telles and Ortiz Citation2009). A third possibility for the new second generation is selective acculturation, that is, retaining elements from their immigrant communities in order to maximise the prospect of upward mobility into the middle-class majority (Zhou and Bankston Citation1998).

But upward mobility need not be synonymous with converging into a White, middle class, as Neckerman, Carter, and Lee (Citation1999) astutely noted. They added to Portes and Zhou’s (Citation1993) menu of assimilation trajectories by positing that America’s newest immigrants from Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa may assimilate into a minority middle-class. As non-White, non-European immigrants, they may draw on unique strategies of mobility to combat structural discrimination and racial bias, turning to middle-class African Americans as mobility prototypes (see also Imoagene Citation2017; Vallejo Citation2012). Hence, rather than juxtaposing social mobility and racial disadvantage as extremes, the ‘minority culture of mobility’ illustrates how socioeconomic attainment can occur in tandem with and even in spite of racialization, akin to the experiences of highly educated, middle– and upper-middle class African Americans.

While racial status figures prominently in theories of segmented assimilation and the minority culture of mobility, it is absent in the latter stages of Gordon’s (Citation1964) model, which focused on European immigrants who were already White, despite the ethnic distinctions among them. Moreover, apart from the racial status of Black Americans for whom race remains significant, the racial status of newer immigrant groups, including Asians, disappears in neo-assimilation models. Once suspended, the focus of assimilation turned to the structural. As sociologists, we have used markers of structural assimilation as the linchpin of assimilation while suspending altogether or treating as secondary social psychological and cultural measures, including perceptions of belonging and group position. There appear to be two reasons for this. The first is that ‘hard’ measures such as educational attainment, median household income, intermarriage, and even multiracial identification are more easily quantified and compared relative to ‘softer’ measures like belonging and group position.

Second, we have privileged the former based on a Eurocentric model of U.S. nation building, in which the assumption is that all other types of assimilation will ‘naturally follow’ structural assimilation, as it did for European White ethnics such as Italians and Jews (Alba Citation2006; Citation1985). And because in the case of Asian Americans, high rates of intermarriage and a growing multiracial population do, indeed, follow structural assimilation, some social scientists conclude that Asians are following in the footsteps of their European predecessors, and assimilating into the American mainstream. But underlying this premise is that the ethnoracial boundaries around the Asian category are as permeable as they were for Americans of European descent. History has shown time and again that this has not been the case.

When we adopt a subject-centered approach that privileges the experiences, perceptions of belonging, and group position of the populations we study, how does this change canonical assumptions about assimilation? Allow us to offer a poignant example by drawing on Fernández-Kelly’s (Citation2020) study of undocumented Latino youth in New Jersey. She finds that the youth develop stronger identities, a more positive self-evaluation, and a greater sense of belonging in resource-poor Trenton than in resource-rich Princeton – in essence, challenging assumptions about the primary role of material resources and a welcoming community for immigrant assimilation. By adopting a subject-centered approach, Fernández-Kelly learns that the visible racial and class divides from Princeton’s residents are daily reminders for the undocumented Latino youth that they do not completely belong nor are accepted. In Princeton, the ‘yawning social distance vis-à-vis the surrounding population diminishes the potential effects of policies designed by the local government to boost the prospects of immigrants and their children’ (Fernández-Kelly Citation2020, 195).

The work of Portes, Aparicio, and Haller (Citation2016) in Spanish Legacies points to another pair of counterintuitive assimilation findings. On the question of belonging, they find that the second generation in Spain feel a greater sense of belonging compared to the U.S. second-generation, despite the longer history of migration in the United States. The former are more likely to identify as Spanish, and less likely to report that discrimination is a major problem compared to their counterparts in the United States. They reason that because Spain has not been a traditional destination for immigrants, it lacks the hardened policies and traditional narratives about how newcomers should assimilate. Flexible local policies lead immigrants and the second generation to feel a greater sense of belonging (Portes, Aparicio, and Haller Citation2016). Here, we add an additional insight: the cross national comparison between the U.S. and Spain also points to how legacies of immigrant exclusion – or the lack thereof – can affect perceptions of belonging among contemporary immigrants and their children.

We follow the footsteps of these scholars and take belonging seriously (see also Jimenez et al. Citation2021). We shift the frame from structural measures of assimilation to the subject-centered, and focus on experiences, perceptions of belonging, and sense of group position. In doing so, we highlight that which has been theoretically invisible: the epistemological gap between canonical assumptions about Asian American assimilation and the quotidian lived experiences of Asian Americans. At no recent time has this gap become more glaring than during the COVID-19 pandemic.

COVID-19 and the surge in anti-Asian violence

As fears and insecurities about the coronavirus mounted in the United States, so too did attacks on Asian Americans. They have been killed, stabbed, beaten, bullied, spit on, punched, pushed, verbally harassed, and vilified based on the false assumption that they are to blame for the origin and spread of COVID-19. The first widely reported attack occurred on February 2, 2020 in a New York City subway station. An Asian woman wearing a face mask was called ‘a diseased bitch’ by a man who then punched her in the head. A month later in March 11, 2020, a 23-year-old Asian woman was punched in the face by a stranger who screamed, ‘Where’s your fucking mask? You’ve got coronavirus, you Asian fuck!’ The female assailant and her friends surrounded the Asian woman and verbally harassed her before eventually fleeing the scene.

A few days later on March 14, 2020 at a Sam’s Club in Texas, a Burmese man and his 6-year-old son was stabbed by a man who believed they were Chinese and ‘from the country who started spreading that disease around.’ Grabbing a serrated steak knife in the store and then bending the blade around his knuckles with the sharp edge facing out so he could slash and punch in a single motion, the man began attacking the Burmese family. After punching the father and cutting his face, he saw the victim’s two children, 6 and 2, seated in the front basket of a shopping cart, and slashed open the older child’s face, coming millimeters from the child’s eye. A Sam Club’s employee came to the family’s defense, and suffered multiple cuts while subduing the assailant. While attacking the family, the man yelled, ‘Get out of America!’

In one fell swoop, the coronavirus – and former U.S. President Trump’s blithe description of it as the ‘Chinese virus,’ the ‘Wuhan virus’ and ‘kung flu’ – reanimated a centuries-old trope that Asians are contagious vectors of disease. By the summer of 2020, 76 percent of Asian Americans reported worrying at least sometimes about being a victim of a hate crime because of their race due to COVID-19, with 27 percent admitting that they worry very often (Lee and Ramakrishnan Citation2021).

While Asian Americans had been sounding the alarm about a surge in anti-Asian violence and hate crimes since the start of the pandemic, it took the mass murder of eight people in Atlanta, including six women of Asian descent, more than a year later to catapult anti-Asian violence onto a national platform. On March 16, 2021, a 21-year-old White man bought a gun and ammunition, and drove to an Asian-owned spa 30 miles north of Atlanta. He paid for and received a sexual favour, and then shot five people. He killed four of the five, including two Chinese women who worked at the spa, a White man and a White woman, and injured a Hispanic man. He then drove 27 miles south to another Asian-owned spa, and shot and killed three Korean women. Then, he headed across the street to a third Asian-owned spa, where he killed another Korean woman, bringing the death toll to eight. He was captured while driving to Florida where he planned to commit similar crimes.

The shooter denied harboring racial bias, and told officials that he carried out the massacre as a form of vengeance for his sexual addiction. Some took his words at face value. But let this sink in: he chose three Asian-owned spas, 27 miles apart, and targeted Asian women as the objects of his rage and lust (Cheng Citation2021). Moreover, he carried out the murders during a global pandemic, amidst a surge in anti-Asian violence and hate crimes.

Between 2019 and 2020, reported hate crimes decreased by 7 percent nationwide, but increased by 150 percent against Asians. In New York City, anti-Asian hate crimes spiked by 361 percent in 2021. Still reeling from the Atlanta massacre, Asian Americans did not find solace in 2022, which opened with the murder of Michelle Alyssa Go, who was pushed to her death in front of a subway at Times Square. A month later, Christina Yuna Lee was stalked to her Chinatown apartment, and died after being stabbed more than 40 times. Then in March, a 67-year-old Asian woman was punched in the face and head over 125 times during the course of a minute and 12 seconds. The attacker then stomped on her seven times and spat on her before walking away. The victim was hospitalised with broken bones in her face, bleeding in the brain, and cuts and bruises across her head. Before attacking her, the assailant called her an ‘Asian bitch!’

The details and motivations of each case may differ, but as social scientists, we recognise that an increase in violence and hate crimes merits – if not demands – study. Until recently, social scientists lacked nationally representative survey data to study the experiences, perceptions of belonging, and sense of group position of Asian Americans. Apart from the National Asian American Survey, most national surveys overlook the U.S. Asian population, collapse Asians into an ‘Other’ category, or contain too few cases of Asians for meaningful analyses. The Atlanta spa shootings in the spring of 2021 was a flashpoint for the pursuit of more equitable data collection on the U.S. Asian population.

Born of crises, several data collection efforts emerged to fill this void: the American Experiences with Discrimination SurveyFootnote1; the STAATUS Index (the Social Tracking of Asian Americans in the United States) that focuses on the national attitudes towards Asian AmericansFootnote2; the California Health Interview Survey’s (CHIS) COVID-19 ModuleFootnote3; and the Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP). Conceived and designed in response to the surge in violence, xenophobia, and hate crimes against Asian Americans, each survey filled an empirical void during an urgent time.Footnote4

Experiences and perceptions of Asian Americans during the pandemic

According to the American Experiences with Discrimination Survey, there has been an increase in anti-Asian hate crimes since the onset of COVID-19 in the United States: 1 in 6 (15 percent) Asian American adults reported experiencing a hate crime in 2021Footnote5, up from 1 in 8 in 2020. In the first three months of 2022, the figure had already reached one in twelve. By these estimates, about three million Asian Americans have been a victim of hate crime since March of 2020. Results from the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) COVID-19 module confirm the prevalence. In California – home to 1 in 6 Asian Americans – 10 percent Asian Americans and 12 percent of Chinese Americans experienced a hate crime or hate incident due to COVID-19 compared to only 2 percent of all Californians. In addition, 28 percent of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders either experienced or witnessed a hate incident during the pandemic (Shimkhada and Ponce Citation2022).

Apart experiencing hate crimes, Asian Americans have also experienced everyday acts of discrimination during the pandemic, as shows. For example, 11 percent of Asian American men and women have been coughed on or spit on; 29 percent of Asian American men and 31 percent of Asian American women have been the target of offensive physical gestures; 33 percent of men and 34 percent of women have been called names or insulted; and 31 percent of men 29 percent of women have been told to ‘go back to your country’ (American Experiences with Discrimination Survey Citation2022).

Table 1. Everyday Acts of Discrimination Experienced by Asian Americans by Gender

Not surprisingly, as a result of the increase in anti-Asian violence and racism, 3 in 4 Asian American adults worry at least sometimes about being victimised because of their race, and 1 in 3 have changed their daily routines due to the worry (Noe-Bustamante et al. Citation2022). Asian American women are especially likely to worry about being victimised with 1 in 7 reporting that they worry all the time, despite survey results showing that men and women have been equally likely to be a victim of a hate crime during the pandemic (Lee and Ramakrishnan Citation2021; Wong and Ramakrishnan Citation2021). To underscore, there are no gender differences in experiencing hate crimes and everyday acts of discrimination, yet Asian American women are more likely to worry, more likely to perceive an increase in hate crimes, less comfortable reporting a hate crime to authorities, less likely to believe that justice will be served if they report a hate crime, and more likely to believe they will be attacked again if they do so (Lee and Ramakrishnan Citation2022).

While anti-Asian racism is far from universal (Daniels et al. Citation2021), findings from the STAATUS Index point to an undeniable increase since the start of the pandemic. In 2022, 1 in 5 non-Asian Americans believed that Asian Americans are at least partly responsible for COVID-19, up from 1 in 10 in 2021. In 2022, non-Asian Americans were also more likely to believe that referring to the coronavirus as the ‘Chinese virus’ and ‘Wuhan virus’ was appropriate. And on the question of national loyalty, 1 in 3 believed that Asian Americans were more loyal to their country of origin than to the United States – up from 1 in 5 in 2021.

Anti-Asian racism, violence, and the fear of being victimised among Asian Americans have increased during the pandemic, yet one-third of Americans remain unaware of the rise. The invisibility of Asian Americans’ experiences reflects the invisibiliation of Asian Americans in the American imagination: 58 percent of Americans cannot think of a single prominent Asian American (STAATUS Index Citation2022). Among those who do, the most popular responses are Jackie Chan (who is not American) and Bruce Lee (who died half a century ago).

On belonging, identity, and group position

Given the surge in anti-Asian violence and hate incidents combined with the invisibilization of Asian Americans, perhaps it comes as little surprise that Asian Americans are the ethnoracial group that is least likely to feel that they completely belong and are accepted in the United States: only 29 percent report feeling that they completely belong compared to 33 percent of Black Americans, 42 percent of Latino Americans, and 61 percent of White Americans. The feeling of not belonging is especially acute among Asian American women – who are twice as likely to be interracially married than Asian American men – and young adults who are more likely to be U.S.-born and educated (STAATUS Index Citation2022).

On the question of identity, Asian Americans were asked whether they consider themselves a person of colour on the American Experiences with Discrimination Survey. Nearly two-thirds of Asian Americans (63 percent) identified as such – a finding that nearly mirrors that from Starr and Freeland’s (Citation2023) national survey in which 61 percent of Asian Americans identified as people of colour.

While we found no significant gender differences between Asian American men (61 percent) and women (64 percent), we discovered a significant intersectional difference. U.S.-born Asian men are only slightly less likely than foreign-born Asian men to consider themselves a person of colour (59 percent vs. 62 percent), while U.S.-born Asian women are significantly more likely to perceive themselves as a person of colour compared to their foreign-born counterparts (73 percent vs. 62 percent). That U.S.-born Asian women are more likely to identify as a person of colour than their foreign-born counterparts despite their higher rates of intermarriage and higher incomes underscores the relevance of the assimilation paradox among native-born Asian American women, in particular.

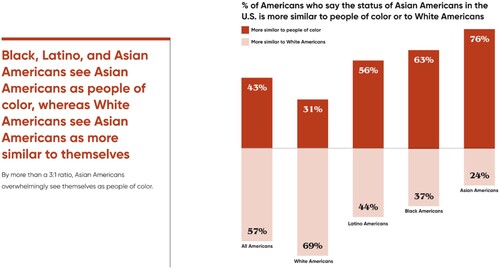

In a separate question on a different national survey, the 2022 STAATUS Index, Asian Americans were asked whether they perceive their status as closer to people of colour or to Whites. As shows, 76 percent reported that they view their status as closer to people of colour than to Whites. While 57 percent of all Americans view the status of Asians as closer to Whites, data disaggregation shows that this perception is driven, in large part, by the views of White Americans. The majority of Black Americans (63 percent) and Hispanic Americans (56 percent) perceive Asian Americans as closer to people of colour than to White Americans. By stark contrast, White Americans are the only group who are more likely to perceive the status of Asian Americans as closer to Whites (69 percent) than to people of colour.

Figure 3. Percent of Americans who say the status of Asian Americans in the U.S. is more similar to people of colour or to White Americans. Source: 2022 STAATUS Index.

Apart from these ethnoracial differences, we also find differences by age, gender, political leaning and affiliation – findings also confirmed by Starr and Freeland’s (Citation2023) research. Older Americans, men, politically conservative Americans, and Republicans are more likely to view the status of Asian Americans as more similar to Whites, whereas younger Americans, women, liberal Americans, and Democrats are more likely to perceive the status of Asian Americans as closer to people of colour. The disjuncture between the way that Asian Americans perceive their racial status compared to White Americans – especially those who are politically conservative and identify as Republican – is a compelling example of what we get wrong when we fail to adopt a subject-centered approach.

Conclusions: reclaiming narratives of Asian American assimilation

For many observers, the rise in anti-Asian racism and violence is a result of Trump’s repeated reference to the coronavirus as the ‘Chinese virus’, the ‘Wuhan virus’, and ‘kung flu’. Words have consequences. Non-Asian Americans exposed to the ‘China virus’ rhetoric for just three weeks in March of 2020 led politically conservative Americans to be more likely to perceive Asian Americans as foreign and un-American (Darling-Hammond et al. Citation2020). But it would be a mistake to reduce the increase in violence and racism to Trump’s dog whistle politics alone. Even before the pandemic, hate crimes against Asians under the Trump administration rose 31 percent between 2016 and 2018 (Massey Citation2021). And even under a new administration, hate crimes against Asians continue to increase despite President Biden’s signing the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act into law shortly after taking office. Moreover, the surge in violence and hate crimes against Asians is not unique to the United States. Canada, the UK, and France have also witnessed spikes in anti-Asian racism and hate crimes during the pandemic (Assemblée Nationale Citation2021; Baylon and Cecco Citation2021).

So how should we understand the rise in anti-Asian violence and racism since the onset of COVID-19, and what does this reveal about Asian American assimilation? First, we maintain that we cannot understand present without reckoning with the past, including an under-recognised legacy of exclusion that dates back more than 150 years. This includes incorporating the history of exclusion from citizenship and immigration into our theories of assimilation, as well as reckoning with the roles of science, medicine, and law in constructing Chinese women as medical and moral threats.

While there is a long history of linking immigrants with disease and framing anti-immigrant rhetoric in medical terms (Daniels et al. Citation2021; Markel and Stern Citation2002; Shah Citation2001; Trauner Citation1978), the scientific justification of Chinese women’s bodies as uniquely diseased, and their morals, deviant, helped to justify the racial foundations for Asian exclusion. Prohibiting the immigration of women from “China, Japan, or any Oriental country” brought for “lewd and immoral purposes”, the 1875 Page Act marked the beginning of decades of federal restrictive policies that choked Asian immigration and suppressed the Asian population to a mere 0.6 percent of the country’s total as late as 1960. The construct of Asian women as morally depraved and expendable has since been reinforced through wars in Asia that dehumanised Asians, and through images of Asian prostitutes that accompanied them, thereby reifying the notion that Asian life is cheap and disposable (M. Lee Citation2021). In times of crises, Asians should go back to where they came from – a taunt born from the architect of the Page Act.

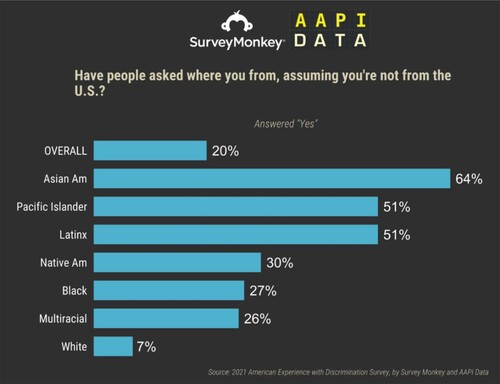

Most Americans – including Asian Americans – are unfamiliar with this legacy of exclusion, yet the stereotypes that were born of it are all-too familiar: Asians are foreign, alien, and un-American. The perceived foreignness of Asian Americans is reflected in how often they are asked, ‘Where are you from?’ with the assumption that they are not from the United States. As shows, nearly two-thirds of the Asian respondents (64 percent) reported having been asked this question with U.S.-born Asians just as likely to be asked as the foreign-born, indicating that nativity is no shield against perceived foreignness. To put this figure into perspective, Asians are nine times more likely than White Americans to have been asked this question. While seemingly innocuous to an outside observer, the question of where are you from, followed up by where are you really from, and where are your parents and grandparents from, is a reminder that Asians must be from elsewhere, that they could not possibly be from here. In times of crises, they do not belong here.

Figure 4. Percent of Americans who have been asked, Where are you from, assuming you’re not from the U.S. Source: 2021 American Experience with Discrimination Survey.

The change in U.S. immigration law in 1965 legally engineered Asian immigrant hyper-selectivity, that is, newcomers who arrived to the United States already armed with college degrees. Based on measures like educational attainment and median household income, neo-assimilationists have argued that Asian Americans are not only entering the mainstream but also remaking it in the process. Here, we make our second point by noting a flaw in this logic: the tautology of using indicators of socioeconomic attainment acquired from Asian immigrants’ countries of origin as measures of their structural assimilation in their country of destination (Zeng and Xie Citation2004).

Moreover, using socioeconomic attainment to compare the experiences of the post-1965 wave of Asian immigrants to that of European immigrants of yore is a false equivalency. Unlike the majority of contemporary Asian immigrants who are hyper-selected, the majority of European immigrants who arrived at the turn of the twentieth century were largely negatively or neutrally selected (Abramitzky and Boustan Citation2022). Hence, the socioeconomic attainment and intergenerational mobility of Americans of European descent are, indeed, indicative of their structural assimilation. This is not the case for contemporary Asian immigrants, the majority of whom already arrive with higher levels of human capital than the U.S.-born.

Finally, we urge scholars to shift the frame from focusing exclusively on normative indicators of assimilation to include subject-centered measures that privilege the voices of the populations we study. When we, as social scientists, rely solely on normative indicators to draw conclusions about assimilation, we must ask ourselves what are we missing, and what are we getting wrong? Studies of intermarriage and multiracial identification show that Asian Americans are more likely than Black Americans to intermarry with White Americans and also more likely to adopt a multiracial identification (Alba Citation2020; Lee and Bean Citation2010; Xie and Goyette Citation1997). And because younger, native-born Asians are significantly more likely to intermarry and claim a multiracial identification than their older, foreign-born counterparts, some social scientists conclude that Asians are following the footsteps of their European predecessors and assimilating into the American mainstream (Foner Citation2022; Kasinitz et al. Citation2009; Waters and Pineau Citation2015). But this process rests on two assumptions: first, the obfuscation of racial difference; and second, the boundaries around the Asian category will be as permeable and fluid as they were for European ethnics.

Even if we grant that the boundaries of Whiteness and Blackness as well as who counts as Asian, Hispanic, and as a person of colour are subject to change (Abascal Citation2020; Lee and Ramakrishnan Citation2020; Jimenez Citation2009; Mora Citation2014; Okamoto Citation2014; Pérez Citation2021; Starr and Freeland Citation2023; Zou and Cheryan Citation2017), that even East Asians who have been in the United States for generations continue to experience racial insults, perceived foreignness, and everyday acts of discrimination make the prospect ‘decategorization’ for Asian Americans seem implausible. At no recent time has this become more evident than in this current moment as the country continues to wrestle with the social, economic, and public health devastations wrought by COVID-19.

Questions about Asian American assimilation will not abate in the near future. They will become increasingly urgent as the U.S. Asian population continues to grow and diversify through immigration, consequently replenishing the meaning, content, and boundaries around the Asian category. Moreover, Asian American assimilation will be affected by not only the changes within the U.S. Asian population but also by domestic and international exigencies beyond it.

While some social scientists forecast an expanded U.S. mainstream (Alba and Nee Citation2003; Alba Citation2020), others point to signs of contraction. For example, research shows that White Americans respond to threats to their group’s status by contracting who counts as White. When confronted with their numeric decline, they choose to expel people of ambiguous origins from their ranks, and raise the bar to inclusion (Abascal Citation2020). For politically conservative White Americans, the perceived waning of their racial status and group position has strengthened White racial group consciousness – a consistent predictor of restricting immigration and immigration rights (Jardina Citation2019; Massey Citation2021; Wong Citation2018). In addition, priming White Americans about population change generates greater bias towards Blacks and Asians as well as stronger support for politically conservative policies (Craig and Richeson Citation2014a, Citation2014b). Real demographic changes, perceived threats to group status, and the nature of geopolitics – including the perceived threat of China – will continue to affect trends and patterns of Asian American assimilation. That the perceived threat of China stokes bias against not only Chinese nationals but also against Asian Americans among politically conservative Americans underscores this reality (He and Xie Citation2022; Lee Citation2022).

At this moment it may come as little surprise that the majority of Asian Americans do not feel they completely belong nor feel accepted in U.S. society, but it would be a mistake to reduce these sentiments to the spillover effects of COVID-19 alone. Even before the pandemic, 22 percent of Asian Americans in California reported having experienced a hate crime or hate incident. What COVID-19 did was make anti-Asian racism more blatant, and anti-Asian violence impossible to ignore. While new data collection efforts enabled researchers to assess the patterns and prevalence of anti-Asian hate incidents during the pandemic, it also enabled researchers to pay heed to subject-centered measures that focused on the social psychological and cultural dynamics of intergroup relations that are too often ignored in sociological research (Bobo Citation2011; Huang Citation2021; Lee Citation2002, Citation2021).

For the first time in a national survey, Asian Americans were asked whether they identify as a person of colour, and 63 percent reported they do. And for the first time in a separate survey, Asian Americans were asked whether they view their racial status as more similar to Whites or to people of colour, and 76 percent chose the latter. And when asked whether they feel like they completely belong in U.S. society, Asian Americans were the least likely ethnoracial group to report that they do. Hence, rather than drawing conclusions based exclusively on normative indicators, we enabled Asian Americans to craft their own narratives, while rejecting those that distort them. By placing the history, experiences, sense of belonging and group position at the centre of our analyses, we unveiled an assimilation paradox: high socioeconomic attainment coupled with low levels of perceived belonging and acceptance, and overwhelming identification as people of colour. Our results indicate that Asian Americans are not simply assimilating into the so-called American mainstream, but, rather, adopting a minority culture of mobility as they assimilate into a minority middle-class in which socioeconomic attainment occurs in tandem with and in spite of racialization as Neckerman, Carter, and Lee (Citation1999) presciently noted more than two decades ago.

We close by underscoring that addressing the Asian American assimilation paradox begins with integrating the fraught history of Asian America into sociological theories of assimilation. As Faulkner (Citation1951) long noted, ‘the past is never dead, it isn’t even past.’ While research from other disciplines – including History, Law, and Asian American Studies – has helped to fill this lacunae, we should not need to turn exclusively to other disciplines to help us inform our own. Second, we urge social scientists to acknowledge the tautology of some of our normative measures, and, third, to include subject-centered approaches into our theoretical frameworks and research designs. All are necessary steps to closing the gap between canonical assumptions and lived experiences in our understanding of assimiliation, as is making the study of Asian Americans central to the discourse on immigration and race.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge feedback from Mitchell Duneier, Didier Fassin, Patricia Fernández-Kelly, Alejandro Portes, Paul Starr, Yu Xie, the editors and reviewers of the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, the 2022-23 Members of the School of Social Science at the Institute for Advanced Study, and the participants of the Center for Migration and Development at Princeton University. For fellowship support, Jennifer Lee thanks the Institute for Advanced Study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The 2022 American Experiences with Discrimination Survey was conducted online by Momentive (formerly SurveyMonkey) March 2-9, 2022 among a total sample of 16,901 adults ages 18 and over, including 1,991 Asian or Asian Americans and 186 Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders living in the United States. It was a one-year follow up to 2021 American Experiences with Discrimination Survey conducted online March 18-25, 2021 among a total sample of 16,336 adults ages 18 and over, including 2,017 Asian or Asian Americans, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders living in the United States. The 2021 survey launched just two days after the Atlanta massacre.

Respondents for these surveys were selected from more than two million people who take surveys on the SurveyMonkey platform each day. SurveyMonkey used a third-party panel provider to obtain additional sample with quotas for Asian or Asian American and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander respondents. The modeled error estimate for the full sample is plus or minus 1.5 percentage points and for the following subgroups: Asian American or Pacific Islander +/-3.5 percentage points. Data have been weighted for age, race, sex, education, citizenship status, and geography using the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey to reflect the demographic composition of the United States age 18 and over.

2 The 2022 STAATUS Index – the Social Tracking of Asian Americans in the United States – is a national survey of 5,113 U.S. residents, age 18 and over, including 2,840 White Americans, 888 Black Americans, 1,023 Hispanic Americans, and 1,074 Asian Americans. The survey was conducted online in English between February 10 to February 28, 2022 by Savanta Research. Results are valid within +/-1.4% at the 95% confidence level. This margin of error increases with subgroup analyses. The sample was weighted using population parameters (race, age, gender, education, and region) from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey for adults 18 years of age or older. This weighting reflects the national population. The 2022 STAATUS Index was a follow-up to the 2021 STAATUS Index.

3 The California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) is the largest annual state-based population health survey in the United States and has facilitated the generation of population-based AANHPI subgroup estimates used in studies nationwide. The CHIS conducts interviews in Cantonese, Mandarin, Korean, Vietnamese, and Tagalog in addition to English and Spanish. The survey is limited to California, but California is home to the largest single-race NHPI and Asian population of any US state. In its annual continuous survey, CHIS randomly selects 1 adult to interview in a randomly sampled participating household. An address-based sample methodology is used to complete the random sampling, with multimode data collection done via Web or telephone. One of the primary goals of the sampling strategy is to produce statistics that reflect the state’s racial/ethnic diversity. The module was administered to CHIS adult respondents who reported “any mention” of “Asian” or “NHPI” for race, and thus both single-race and multiracial AANHPIs were included. The AANHPI COVID-19 module was developed in response to the rise of hate, racism, xenophobia, and discrimination targeting AANHPI communities.

4 While the data are weighted to represent the U.S. Asian population, the margin for error for Asian national origin groups prevents us from data disaggregating within the Asian American population.

5 Respondents were asked, “Have you ever been a victim of a hate crime? That is, have you ever had someone verbally or physically abuse you, or damage your property specifically because of your race or ethnicity?”

References

- Abascal, M. 2020. “Contraction as a Response to Group Threat: Demographic Decline and Whites’ Classification of People Who Are Ambiguously White.” American Sociological Review 85 (2): 298–322. doi:10.1177/0003122420905127.

- Abramitzky, R., and L. Boustan. 2022. Streets of Gold: America’s Untold Story of Immigrant Success. New York: Public Affairs.

- Abrams, K. 2005. “Polygamy, Prostitution, and the Federalization of Immigration Law.” Columbia Law Review 105 (3): 641–716.

- Alba, R. D. 1985. Italian Americans: Into the Twilight of Ethnicity. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

- Alba, R. D. 2006. “On the Sociological Significance of the American Jewish Experience: Boundary Blurring, Assimilation, and Pluralism.” Sociology of Religion 67 (4): 347–358. doi:10.1093/socrel/67.4.347.

- Alba, R. D. 2020. The Great Demographic Illusion: Majority, Minority, and the Expanding American Mainstream. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Alba, R. D., and V. Nee. 2003. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- American Experiences with Discrimination Survey. 2022. AAPI Data | Momentive Poll. https://momentive.ai/en/blog/aapi-data-2022/.

- Antonovich, J. D. 2018. Medical Frontiers: Women Physicians and the Politics and Practice of Medicine in the American West, 1870-1930. PhD Dissertation, Department of History, University of Michigan.

- Assemblée Nationale. Rapport d’Information. Paris (FR). 2021. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/15/rapports/racisme/l15b3969-ti_rapport-information#_Toc256000044.

- Baylon, J., and L. Cecco. 2021. Attacks make Vancouver ‘anti-Asian hate crime capital of North America’ | Canada. The Guardian. 2021, May 23. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/may/23/vancoucer-anti-asian-hate-crimes-increase.

- Bobo, L. 2011. “Racialization, Assimilation, and the Mexican American Experience.” Du Bois Review 8 (2): 497–510.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. 2004. “From bi-Racial to tri-Racial: Towards a new System of Racial Stratification in the USA.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 27 (6): 931–950. doi:10.1080/0141987042000268530.

- Brown, S. K., and F. D. Bean. 2006. Assimilation Models, Old and New: Explaining a Long-Term Process. Migration Policy Institute. 2006, Oct 1. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/assimilation-models-old-and-new-explaining-long-term-process.

- Calavita, K. 2006. “Gender, Migration, and Law: Crossing Borders and Bridging Disciplines.” International Migration Review 40 (1): 104–132. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2006.00005.x.

- Carbado, D. W. 2009. “Yellow by Law.” California Law Review 97 (3): 633–692.

- Chan, S. 2009. “The Exclusion of Chinese Women.” In Entry Denied: Exclusion and the Chinese Community in America, 1882-1943, edited by S. Chan, 94–146. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Chang, K. 2009. “Circulating Race and Empire: Transnational Labor Activism and the Politics of Anti-Asian Agitation in the Anglo-American Pacific World, 1880-1910.” Journal of American History 96 (3): 678–701. doi:10.1093/jahist/96.3.678.

- Cheng, A. 2021. The Dehumanizing Logic of All the ‘Happy Ending’ Jokes. The Atlantic. 2021, March 23. Accessed Feb 14, 2023. https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2021/03/atlanta-shootings-racist-hatred-doesnt-preclude-desire/618361/.

- Colbern, A., and K. Ramakrishnan. 2020. Citizenship Reimagined: A New Framework for State Rights in the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Colby, S. L., and J. M. Ortman. 2015. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Reports. P25-1143.

- Craddock, S. 1999. “Embodying Place: Pathologizing Chinese and Chinatown in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco.” Antipode 31 (4): 351–371. doi:10.1111/1467-8330.00109.

- Craig, M., and J. Richeson. 2014a. “More Diverse Yet Less Tolerant? How the Increasingly Diverse Racial Landscape Affects White Americans’ Racial Attitudes.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40 (6): 750–761. doi:10.1177/0146167214524993.

- Craig, M., and J. Richeson. 2014b. “On the Precipice of a “Majority-Minority” America.” Psychological Science 25 (6): 1189–1197. doi:10.1177/0956797614527113.

- Curry, L. 2021. “Sweep All These Pests from Our Midst”: The Anti-Chinese Prostitution Movement, the Criminalization of Chinese Women, and the First Federal Immigration Law.” West Virginia University Historical Review 2 (1), Article 3.

- Daniels, C., P. DiMaggio, G. C. Mora, and H. Shepherd. 2021. “Has Pandemic Threat Stoked Xenophobia? How COVID-19 Influences California Voters’ Attitudes Toward Diversity and Immigration.” Sociological Forum 36 (4): 889–915. doi:10.1111/socf.12750.

- Darling-Hammond, S., E. K. Michaels, A. M. Allen, D. H. Chae, M. D. Thomas, T. T. Nguyen, M. M. Mujahid, and R. C. Johnson. 2020. “After “The China Virus” Went Viral: Racially Charged Coronavirus Coverage and Trends in Bias Against Asian Americans.” Health Education & Behavior 47 (6): 870–879. doi:10.1177/1090198120957949.

- Diaz, E. B., and J. Lee. 2020. “Cultural Heterogeneity and the Diverse Success Frames of Second-Generation Mexicans.” Social Sciences 9 (12): 216. doi:10.3390/socsci9120216.

- Drake, S. 2022. Academic Apartheid. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Duneier, M. 1992. Slim’s Table. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Duneier, M. 1999. Sidewalk. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Faulkner, W. 1951. Requiem for a Nun. New York: Random House.

- Fernández-Kelly, P. 2016. “Fixing the Cultural Fallacy.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (13): 2372–2378. doi:10.1080/01419870.2016.1200744.

- Fernández-Kelly, P. 2020. “The Integration Paradox: Contrasting Patterns in Adaptation among Immigrant Children in Central New Jersey.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 43 (1): 180–198. doi:10.1080/01419870.2019.1667510.

- Foner, N. 2022. One Quarter of the Nation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gordon, M. 1964. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Haller, W., A. Portes, and S. M. Lynch. 2011. “Dreams Fulfilled, Dreams Shattered: Determinants of Segmented Assimilation in the Second Generation.” Social Forces 89 (3): 733–762. doi:10.1353/sof.2011.0003.

- Haney López, I. 1996. White by Law. New York: New York University Press.

- He, Q., and Y. Xie. 2022. “The Moral Filter of Patriotic Prejudice: How Americans View Chinese in the COVID-19 Era.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119 (47). doi:10.1073/pnas.2212183119.

- Hirata, L. C. 1979. “Free, Indentured, Enslaved: Chinese Prostitutes in Nineteenth-Century America.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 5 (1): 3–29. doi:10.1086/493680.

- Hsin, A. 2016. “How Selective Migration Enables Socioeconomic Mobility.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (13): 2379–2384. doi:10.1080/01419870.2016.1200742.

- Hsin, A., and Y. Xie. 2014. “Explaining Asian Americans’ Academic Advantage Over Whites.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (23): 8416–8421. doi:10.1073/pnas.1406402111.

- Huang, T. 2021. “Perceived Discrimination and Intergroup Commonality Among Asian Americans.” RSF: Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 7 (2): 180–200.

- Imoagene, O. 2017. Beyond Expectations: Second-Generation Nigerians in the United States and Britain. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Jardina, A. 2019. White Identity Politics. North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- Jimenez, T. 2009. Replenished Ethnicity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Jimenez, T., D. Schildkraut, Y. Huo, and J. Dovido. 2021. States of Belonging. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Kasinitz, P., M. Waters, J. Mollenkopf, and J. Holdaway. 2009. Inheriting the City: The Children of Immigrants Come of Age. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Lamont, M. 2000. The Dignity of Working Men. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lee, E. 2002. “The Chinese Exclusion Example: Race, Immigration, and American Gatekeeping, 1882-1924.” Journal of American Ethnic History 21 (3): 36–62. doi:10.2307/27502847.

- Lee, E. 2003. At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration During the Exclusion Era 1882-1945. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Lee, J. 2002. Civility in the City: Blacks, Jews, and Koreans in Urban America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lee, C. 2010. ““Where the Danger Lies”: Race, Gender, and Chinese and Japanese Exclusion in the United States, 1870-1924.” Sociological Forum 25 (2): 248–271. doi:10.1111/j.1573-7861.2010.01175.x.

- Lee, J. 2021. “Reckoning with Asian America and the New Culture War on Affirmative Action.” Sociological Forum 36 (4): 863–888. doi:10.1111/socf.12751.

- Lee, J. 2022. “When the Geopolitical Threat of China Stokes Bias Against Asian Americans.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119 (50), doi: 10.1073/pnas.2217950119.