ABSTRACT

Financial inclusion (that is, access by individuals to the services provided by financial institutions such as banks, insurance, and investment firms) is a key condition for economic development, and forms one of the principal policy instruments in China for the promotion of rural-urban integration. Using data from the China Household Financial Studies (2013), this paper investigates the determinants of financial inclusion at the household level in China. Focused on the role of the Chinese household registration system (hukou), this paper proposes a new hukou typology to investigate the composite index of financial inclusion as well as the six indicators. Multilevel estimates reveal substantial differences of financial inclusion among different hukou holders; significant cross-level associations between hukou and economic development is also found, revealing the complex and non-linear relationship between hukou and financial inclusion. These findings shed light on the potential for market failures and two types of discrimination based on hukou system, which deny access to financial services to groups of people. Research implications on how to increase financial inclusion are mentioned and discussed.

Research background

Being financially included means having full access to and effective use of a range of financial services. Financial inclusion can help launch businesses, create job opportunities and increase employment, thus diminishing social poverty and inequality (Grimm and Paffhausen Citation2015; Mugo and Kilonzo Citation2017; Ajide Citation2020). However, financial activities may also significantly increase economic and social inequalities (Mugo and Kilonzo Citation2017; Ajide Citation2020; Stein and Yannelis Citation2020) due to its profit-driven nature (Finke and Huston Citation2003; Yao and Xu Citation2015). Today, financial markets and financial activities have gradually become part of ordinary people’s daily lives (Fligstein and Goldstein Citation2015; Van der Zwan Citation2014). Individuals and families are becoming increasingly responsible for their financial security (Langley Citation2008), with their health and wellbeing strongly tied to financial security (Berry Citation2015).

The relationship between financial inclusion and citizenship entitlement for migrants is becoming increasingly evident in large cities in China. Local governments in large cities, such as Shanghai, Guangzhou, and other tier-one cities have incorporated hukou system as an indispensable part of economic development and distribution (Du Citation2004; Li, Li, and Chen Citation2010). Entitlement of citizenship in cities requires urban and local hukou; thus, hukou conversion is highly desired. However, housing ownership is the primary condition for hukou conversion and full citizenship. Housing prices in megacities have increased by more than 100% since 2010 (The Economist Citation2021), yet despite this, it has not deterred migrants from finding employment urban areas. Indeed, megacities and large cities are the most preferred by migrant workers because of job opportunities and social services in large cities (Chen and Fan Citation2016).

The tangled relationship between hukou, citizenship, and housing has made it apparent that financial inclusion is essential in citizenship attainment for migrants and their offspring. According to Wang (Citation2006), urbanisation in China is city-oriented, family-based, multigenerational, and heavily conditioned on the households’ material resources and financial capacity. Urbanisation for a rural household is a multigenerational project, beginning with the parental generation being employed in a city to accumulate financial capital for the offspring and invest in education, hoping that the younger generation from rural households can achieve urban citizenship via either finding a permanent job or purchasing a house in a city.

Since the early 2000s, the Chinese central government has advocated improvements to financial inclusion and social integration (Barth, Caprio, and Phumiwasana Citation2009), however, the hinderances of hukou are apparent. The existing literature suggests that financial inclusion in China is still unequal and limited to certain social groups. Based on the World Bank Findex database (2012), Fungáčová and Weill (Citation2015) reported that although formal account ownership and formal saving in China outweighed those in other BRICS countries, the use of formal credit was much less widespread. Earlier in 2004, Wu (Citation2004) reported that rural hukou holders were considerably less involved in bank loans and housing mortgages. Furthermore, using data from 2011 China Household Financial studies, Chen and Jin (Citation2017) reported that although more than 50% of households used credit, less than 20% used formal credit. Based on the same dataset, Li and Qian (Citation2018) found less than 15% of the households owned stocks, consistent with the figure (14%) reported by Yao and Xu (Citation2015) based on the Survey of Chinese Consumer Finance and Investor Education 2008.

Due to the economic mobilisation ability of financial inclusion, it has become more and more crucial for rural-urban integration in China. Meanwhile, rural-urban integration has become more vertically stratified, city-oriented, and province-based, the rural discrimination and non-native discrimination are strengthened and deepened against the decentralisation of central government on fiscal expenditure and hukou policy. Consequently, the current rural-urban divide has become less efficient in studying hukou due to the increasing large-scale migration. However, little is known about how the current diversified and stratified hukou shapes financial inclusion; neither has there been sufficient research on how city development modifies how hukou impacts financial inclusion. This paper aims to study how the new hukou typology and economic development impact household financial inclusion by taking two macro-level factors – city and province development – into the consideration.

Migration and the diversified hukou system in urban China

For decades, the distribution of social services and welfare based on hukou has prioritised cities and urban citizens over that of rural populations. The distribution of benefits from hukou has been progressively strengthened and enlarged, making hukou perhaps the most crucial foundation for social and spatial stratification in China (Afridi, Li, and Ren Citation2015), resulting in a kind of rural-urban ‘apartheid’.

Over the years, the hukou system has undergone several changes (Solinger Citation1999). Most importantly, the latest policy measures on the integration of migrants has clearly shown the stratified hukou conversion based on the development of cities:

Fully removing hukou barriers for migrants to settle in medium and small cities (of no more than 3 million permanent residents), gradually removing restrictions in large cities (of more than 3 million, but beneath 8 million permanent residents), and strictly controlling hukou conversion in megacities (of more than 8 million permanent residents) by cancelling the hukou conversion policy which previously supported rural migrants who had been living and working for more than five years. Their family members followed them while only allowing hukou conversion in the outskirts of megacities. (The CPC Central Committee and the State Council Citation2014)

Following Fan (Citation2008)), this paper distinguishes between permanent migrants to cities (i.e. those who converted their hukou and now hold urban hukou status, and temporary migrants who have not (yet) been granted urban hukou status. The recent changes made to the hukou system, and new dimensions of inequality that have emerged from those changes, are analysed later in this paper. I define a five-categorical hukou typology based on dual-classification of hukou attributes – the type of registration and place of registration as follows:

Urban natives, who currently live in a city where they were born and registered.

Urban migrants, who currently live in a city different from where they were born and registered.

Rural migrants, who hold rural hukou registration but now live in a city where is not the registered place of their hukou.

Rural citizens, who live in rural areas where they were born and their hukou were registered.

Neo-urbans, who currently hold an urban hukou registration from the city where they live, but who have obtained this via a hukou conversion process. Conversion is only available after moving to the city in question.

Dividing urban hukou holders into native or migrant is in line with the literature on ‘local citizenship’, which is at the heart of social redistribution in China (Smart and Smart Citation2001). This typology also includes rural citizens in rural areas to provide a comprehensive view of financial inclusion in China, although this research focuses on financial integration in urban areas.

Financial inclusion and hukou

Hukou, is an important institution in social inclusion in China (Afridi, Li, and Ren Citation2015); its social division function has also been found to stretch into financial inclusion, especially under the global trend of financialisation. The mechanisms of how the hukou system shapes financial inclusion are two-fold as it shapes social inclusion, rural discrimination, and non-native discrimination, which in turn derives from the dual-classification of hukou attributes, hukou type (urban vs. rural) and hukou locality (native vs. non-native).

Although the hukou system has become more flexible and has enabled the migration of large population flows towards cities and developed areas, rural-to-urban or intra-urban, rural migrants are still excluded from the social benefits of the hukou system (Wu and Treiman Citation2007). Many studies have documented that non-local hukou holders in large Chinese cities experience multiple sources of discrimination (Zhang et al. Citation2009). This includes: having no or little access to welfare benefits from the local government (Song Citation2014; Wang, Guo, and Cheng Citation2015; Y. Huang and Guo Citation2017); experiencing labour market discrimination, especially in high-wage industries (Song Citation2014); being turned down from job applications; or being paid less than the average (L. Z. Chen et al. Citation2018).

The institutional inclusion/exclusion of social resources based on hukou has extended to financial institutions not only for rural migrants but also for non-natives. For both types of migrants, barriers have been established to prevent them from opening bank accounts or obtaining loans, among other things. For non-natives, discrimination is subtler, as it develops when citizens internalise hukou segregation and the reinforced value of hukou locality. The rural-urban division has led to general social discrimination against the ‘outsider’ (exemplified, for instance, by a non-native accent(s) and/or cheap attire) (Wang Citation2005, Citation2010; Lin et al., Citation2011). The hukou system has become such a social marker that it is even possible to suggest that hukou resembles race in the sense that, like race, hukou functions as a basis for social discrimination and exclusion. These resemblances are based on two main characteristics. First, hukou is passed down from parents to children, and hukou conversion is very difficult and rare (Li, Li, and Chen Citation2010). Second, hukou is not only registered in an official document but is also identified through individuals’ symbolic characteristics such as lifestyles, tastes, and language (Yan Citation2008; Qian, Qian, and Zhu Citation2012), which have been distinctively different between urban and rural citizens after decades of (dis)advantaged accumulation.

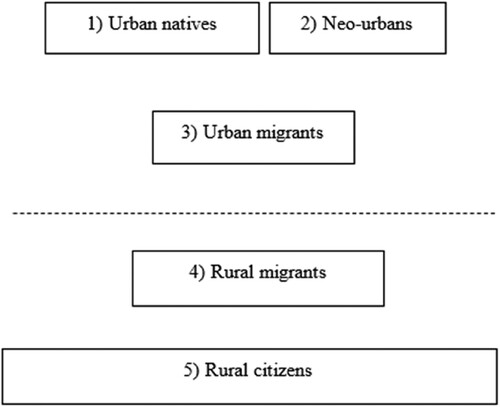

Based on the literature above, the hierarchical structure of hukou is plotted as displayed in . As shown, urban natives are the most institutionally advantaged; neo-urban hukou holders may possibly face one or two instances of discrimination before their hukou conversion and should then be theoretically equally included as urban natives. Urban migrants come second in the rank as they could face non-native discrimination, followed by rural migrants in the cities and rural citizens in the rural areas. The dashed line represents the rural-urban division based on hukou, the institutional barrier, which, however, is 'permeable'.

Two mechanisms of hukou barriers, rural discrimination and non-native discrimination, shape how different hukou holders are financially included, and is in line with the structure of the new hukou typology. Hence, this chapter assumes that rural natives are better off than rural migrants because they have only experienced rural discrimination. In contrast, rural migrants bear dual impediments – being neither urban nor native, and therefore, rural migrants are at the lowest tier of financial inclusion in cities. Thus, the following research hypothesis is posited:

Hypothesis 1: The level of financial inclusion is determined by the hukou hierarchy via institutional barriers and non-native discrimination mechanisms.

This hypothesis suggests that, after controlling for other covariates, neo-urban dwelling households are more likely to enjoy the same financial inclusion level compared to urban native households in a specific area. In contrast, urban migrant families are less included, followed by rural native households, and rural migrants as the least included.

Hukou, city and province development, and financial inclusion

Decentralisation has been reported to be highly beneficial for economic growth in China (Feltenstein and Iwata Citation2005). Local governments gain more power and freedom with their own fiscal expenditure, leading to more diversified economies and relatively self-interested local accountability and regional disparities (Tsui and Wang Citation2008). However, more diversified economic development at the city and province levels has strengthened the instrumental function of hukou in social stratification (i.e. the value of the registered place of hukou) (Tian, Qian, and Qian Citation2018). Simultaneously and parallelly, the Chinese hukou system has experienced institutional changes.

City-oriented development strategies and decentralisation of central government have stratified the value of hukou. Wang (Citation2005) categorised this development as such: hukou in the municipal and capital cities at the top, followed by those in large cities in other provinces, then the county-level ones, and the rural regions at the bottom. Likewise, Gong (Citation2005) argues that the hukou system can be portrayed in the shape of a pyramid, with rural hukou at the bottom, urban hukou from megacities at the top, and other urban hukou from large cities in between. This more stratified hukou system makes rural-urban integration even harder. Migrant populations in Chinese cities, especially in large cities, confront the most stringent barrier to entry and settling down requirements (Wang Citation2005). In another word, hukou as a discriminative social marker has strengthened in large cities.

Empirical evidence finds that migrants prefer large cities over small ones for two main reasons. First, from an economic perspective, large cities offer better job opportunities, infrastructure, and facilities than small cities (Wang Citation2005). Second, from a cultural perspective, for migrants, large cities represent a higher level of modernity and prosperity than small cities (Liu, Deng, and Song Citation2018). However, the latest hukou policies do not the needs of migrants. According the latest migration policy mentioned above – hukou has become more accessible in medium-sized and small cities whereas more difficult in large cities, leaving the disparity between the supply and demand of job opportunities and social services untackled (Chen and Fan Citation2016).

The concentration of migrants in large cities, especially in prefectural cities, can directly lead to a decreased share of public services for all hukou citizens, directly increasing the tensions between the urban and the migrant population (Chen Citation2013; Deng and Law Citation2020). Indeed, scholars have found that migrants in large cities have reported stronger resistance and discrimination from settled citizens (Song Citation2014; Wang, Guo, and Cheng Citation2015; Y. Huang and Guo Citation2017). Meanwhile, to maximise economic development brought by migrant labours and to minimise costs on social services for migrant labours, local governments, especially in large cities, have actually decreased the quota of hukou conversion, using stricter conditions making the process for hukou conversion longer (Chan Citation2010), especially for those who are not highly educated, or so wealthy, or so skilled. This is consistent with Turner’s concerns (Citation1999, Citation2012) – Nation-states no longer adequately provide citizenship for their members and instead we have a growing war of megacities and mega-economies against each other (p.274).

That financial markets mature with economic development, thereby becoming more inclusive and open might not be the case in China. Hukou is a strong determinant for financial inclusion, and how hukou is associated with financial inclusion is modified by economic development, with moderating effects consistent with hukou hierarchy. Although more financial services and better consumer protections are provided in more developed cities and areas (Wong et al. Citation2021), socially less included individuals and households, migrants and especially rural migrants in China, can find it more challenging to be financially included in large cities. Based on this, this paper proposes the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Although economic development at the province and city level can increase financial inclusion, not all hukou holders can benefit from economic development.

Data and research methods

Data

The data for research is from the 2013 China Household Financial Studies (CHFS), carried out by the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics in China and sponsored by China Bank. As a nationally representative survey and ground-breaking project, the information spans from housing and financial assets, household income and wealth, liabilities, and credit restraints, to participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, attitudes, and experiences of financial participation.

Based on CHFS 2013, the analytical sample includes households that are active in financial participation, including having a bank account from a legal bank or organisation; having savings; having financial investments; having ever purchased commercial insurance; and having access to formal credits. The final analytical sample is 24,034 households whose household heads were above 18. This age group is selected because 18 is the minimum age to apply for a bank card. Restricted by the survey, financial activities are measured on the household level, the hukou type of a household is defined by the hukou status of the household head.

Variables

Dependent variables

As financial inclusion is determined by both the demand and the supply side, how much a household is financially included is measured by three aspects: access – the supply of financial services, awareness – financial literacy and willingness of households, and use – the consumption of the exact financial services. This study focuses on the use of financial services, with awareness measured as financial literacy controlled in the research models. Access is not included in the survey; however, socio-economic development of cities and provinces can work as indicators. This is one of the reasons to use multilevel modelling.

Use of financial inclusion is captured as six binary indicators: first, having a bank account (formal account); second, having savings in formal financial institutes (formal saving); and third, financial activities involvement (financial investment). This indicator is restricted to the secondary capital market in this study which included: stocks, bonds, funds, financial derivatives, and other profit-generating products. If the household claimed to have participated in at least one of the listed items, financial investment was coded as 1, and 0 otherwise. As studies reported, social insurance was insufficient to alleviate financial risks (Dou, Wang, and Ying Citation2018), and commercial insurance could supplement social protection schemes against financial risks (Choi et al., Citation2018). Commercial insurance engagement (commercial insurance) is here included as the fourth indicator. It is captured as a binary variable if households have one of the listed items: life insurance, health insurance, pension insurance, and property insurance. In the survey, households were asked whether they possessed any activated credit cards or loans from bank/formal financial institutions for business, agricultural production, housing, cars, education, and medical treatments. If any list items were mentioned, inclusion of formal credit was coded 1 and 0 otherwise. If households had borrowed money from their social networks for any of the listed purposes, informal credit is coded as 1 and 0 otherwise. As informal financial inclusion plays an important role in China (Chai et al. Citation2019), formal credit and informal credit, two sides of the same coin, can better reveal credit use when simultaneously analysed.

The composite index of financial inclusion. A composite index of financial inclusion (financial inclusion hereafter) is created based on Cronbach’s Alfa (alpha value = 0.65) of the first five indicators of household financial inclusion. Loadings of the five components and the alpha values are displayed in . The Cronbach’s alpha of the five items is lower than 0.80, indicating that the composite index is far from ideal. But using a composite index has its merit: it provides an overview of household financial inclusion and related factors.

Table 1. Cronbach alpha and loadings of components measuring financial inclusion.

Categorisation of the independent variables

Hukou hierarchy. It is captured by the household head’s current hukou, presented as five categories as displayed in : urban natives, neo-urbans, urban migrants, rural migrants in urban areas and rural citizens who are rural hukou holders in the rural areas. I included the last hukou type into the studies so as to provide an overall view to the hukou types in China and to compare the financial inclusion between the hukou holders in urban and in rural areas.

City and province development. The mean of the household assets of a city within a province is used as a proxy measure of city development since households in more economically developed cities are more likely to be wealthier. The rationale to use household wealth as the proxy is due to the CHFS survey team withholding information beneath the province level. The ID of the cities are invented ones, which cannot be used to pin down economic development of cities by merging census data. To create city development involves two steps: first, a three-categorial city development based on household wealth is created. Second, cross-tabulation is used to investigate whether it is statistically reasonable to keep the measure as a three-scale variable. As no statistical significance is found between the second and third rank, city development is further coded into binary, with large cities referring to cities at the 1st rank and small cities referring to the rest. Similarly, province development based on GNP per capita in 2013 from China Census is coded as a binary variable, with large provinces (1st - 10th) coded as 1 and small provinces (11th - 29th) as 0.

Covariates

Financial literacy. It measures the awareness of financial inclusion. Studies have shown that financial literacy play essential roles in shaping individuals’ and households’ financial participation, losses and gains (Calvet, Campbell, and Sodini Citation2009; Van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie Citation2011; Yao and Xu Citation2015). Following Zhang and Yin (Citation2016), who have used the CHFS dataset to study financial literacy and financial exclusion in China, I also use seven items available in the CHFS2013 questionnaire as the components to measure financial literacy. Detailed information and coding are displayed in below. After rotation, the total proportion of variance of financial literacy explained by these two factors is 94%. With the KMO value on each item larger than 0.6 as illustrated in , the data is suited to factor analysis (Kaiser Citation1974). Factor 1 is used as a measure of financial literacy as most item loadings on Factor 2 are smaller than 0.3.

Table 2. The seven questions on financial literacy and the coding.

Table 3. Iterated principal-factor analysis of financial literacy.

Household demographic and SES factors. Except for household structure, household demographics are measured at the level of household head, including gender, age and age square, marital status, employment status, and political party membership. From the perspective of demand, wealthy households are more capable to engage in financial activities (Langley Citation2008), controlling the financial status of households can produce better estimations of the association between financial inclusion and hukou hierarchy and city development. Household ownership, equivalised annual household income (in logarithm) (Paris: OECD Citation2008), total household assets (in logarithm), and kinship ties (Chai et al. Citation2019) in the current residential city are captured as household SES.

Analytic strategies

In this chapter, I apply multilevel modelling to estimate the joint impact of the hukou hierarchy and city development on household financial inclusion, including two higher-level indicators: city development and province development. There are two outstanding benefits of using modelling higher-level effects. First, the endogeneity of data can be avoided, and second, the issues of spatial heterogeneity can be addressed through the random effects approach (Snijders and Bosker Citation1999).

As for the analysing stage, firstly, I use the composite index of financial inclusion (based on five indicators) as the dependent variable in the multilevel linear modelling to provide an initial insight into the factors influencing financial inclusion. Secondly, I use multilevel logistic regression to investigate the association between hukou hierarchy and each of six indicators of financial inclusion. Thirdly, I apply interactions to investigate the cross-level association between hukou hierarchy and city and province. Original weights of the household drawn at the community level are compressed by its mean, with values larger than 2.5 and smaller than 0.5, and then included in the regressions. The total cases trimmed occupy less than 6% of the sample.

Empirical results

Descriptive results

displays the descriptive statistics of the independent variables by hukou hierarchy. As shown, household financial inclusion in urban areas overarchingly exceeds that in rural regions on each indicator of financial inclusion, and financial inclusion is neither widespread nor equally distributed among the different hukou holders in cities. Meanwhile, like two sides of a coin, the pattern between rural and urban areas on formal and informal credit inclusion also reveals a relatively low level of financial inclusion in rural areas.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of key variables by hukou hierarchy and the urban-rural divide.

According to the descriptive statistics of the research sample, it is urban migrants who are the most financially included based on the composite index of financial inclusion as well regarding other inclusion indicators, except financial investment. Compared to urban natives, neo-urbans are apparently less included on formal account and financial investment, with gaps ranging between 6% and 9%. Their inclusion of formal saving and formal credit is close, but neo-urbans are more reliant on informal credit. Rural migrants are the least financially included on all the indicators in urban areas, but they outweigh their rural counterparts in rural regions on all the measures and are less reliant on informal credit. Based on the descriptive analysis, the inclusion hierarchy based on hukou are urban migrants, urban natives, neo-urbans, rural migrants, and rural citizens. This descriptive analysis, however, is without the control of demographics and SES indicators.

The residential distribution of rural hukou holders is apparent outstanding at both the city and province levels, which is in line with research findings that megacities and developed areas are the most preferred by migrants. In this sample, the developed provinces (10/31) hosted approximately 90% of the urban migrants and more than 50% of the rural migrants, which are also the main destinations of the neo-urbans who have converted their hukou registration.

Household demographics and SES characteristics differentiate among different hukou holders. The two types of migrant households are younger than other hukou holders. Urban migrants were more educated, with a higher financial literacy, followed by urban natives and neo-urbans. Urban natives and neo-urbans stand out on party membership, followed by urban migrants. The two rural hukou holders were the least educated, with the least amount of financial literacy, although rural migrants were slightly better off. Regarding employment, more household heads of the three urban hukou types were employed, whereas urban and rural migrant households stand out for being self-employed. Other household SES characteristics suggest that urban migrants can be wealthier than urban natives, given their family income is higher than urban natives, with very similar scores on household assets. Rural migrants reported higher levels of kinship ties than urban migrants (60.3%) in cities, as rural migrants are more reliant on social networks (L. Zhang Citation2001).

Multilevel linear regressions predicting the composite index of financial inclusion

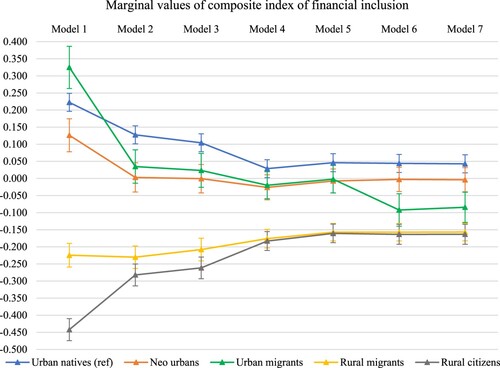

The investigation of hukou hierarchy and financial inclusion starts from the multilevel linear regressions in , using the composite financial inclusion index as the dependent variable. Model (1) is the base model, with the hukou hierarchy variable only; Model (2) adds demographics and SES indicators measured by the household heads, including age, gender, marital status, household structure, educational attainment, job type, and party membership. Model (3) includes financial literacy; Model (4) includes SES factors measured on the household level, including kinship networks, house ownership, household income, and total household assets. In Model (5), city and province development are included. Interactions between hukou and economic development are added to Model (6) and Model (7) in turn.

Table 5. Linear regressions predicting financial inclusion (standardised composite index).

The nested models allow the investigation of trends and dynamics of the variables of interest. To provide a tangible way to understand the association between financial inclusion and hukou, hierarchy marginal values (Average Marginal Effects) of inclusion index by hukou hierarchy are plotted in . As illustrated from Model (1) to Model (2), the inclusion disparity among hukou holders has largely decreased when demographics and SES indicators measured at the household head level are included. The inclusion of financial literacy in Model (3) has further decreased the disparity; one unit increase in financial literacy can significantly lead to a 32.8% increase in the SD of the inclusion index, as displayed in . This suggests the significant association between financial literacy and financial inclusion, and also financial literacy as a strong factor for financial inclusion. Still, inclusion disparity based on hukou remains. As other household SES indicators are included in Model (4), the disparity between urban hukou holders has disappeared, and although the disparity between rural and urban has fanned in, it remains significant. This indicates that financial inclusion variation can be largely explained by the variation in demographics, financial literacy, and household SES indicators.

Table 6. Multi-level logistic regression predicting financial inclusion by each indicator.

Model (5) and Model (6) together reveal that although human capital and household wealth can explain the disparity of financial inclusion based on hukou hierarchy, the distinctive effects of hukou remain. The inclusion of city and province development (in Model (5)) does not modify the disparity between different hukou holders, as the coefficients of the hukou hierarchy in remain nearly unchanged. Nevertheless, living in large or small cities matters, as the marginal value of inclusion index in Model (6) has dropped about 10% as shown in the figure. Urban migrants living in large cities are about 26.4% of an SD more financially included than their peers in small cities as displayed in . Also, estimates suggest that urban migrants, rural migrants, and rural citizens are about 28.3%, 19.4%, and 19.4% of an SD lower of the inclusion index than urban natives. Also, it is worth noting that rural migrants are no more included than their peers in rural areas, supporting the fact that migration may not directly benefit migrants (Li, Li, and Chen Citation2010).

These findings remain almost unchanged in Model (7). Changes in the inclusion index by hukou hierarchy from Model (1) to Model (7) suggest that there are four sources of financial inclusion disparity: demographics, financial literacy, SES indicators, and the hukou division. Results in the full model suggest that financial inclusion is in line with the hukou hierarchy hypothesised by the literature displayed in : urban natives are the most included, followed by neo-urbans and urban migrants, with the two rural hukou holders at the bottom. Based on the investigation of the index of financial inclusion, Hypothesis 1, that financial inclusion varies according to the hierarchical hukou typology cannot be rejected, and the statistics suggest that the mechanism to explain the inclusion distinctions between different hukou types are due to both rural discrimination and the non-local discrimination. Hypothesis 2 is partly rejected, given that city development is significantly associated with financial inclusion but not province development.

Household demographics and SES variables, especially education, employment, party membership, kinship networks, household income and assets, are significantly correlated with financial inclusion. Two macro levels can explain the variation in household financial inclusion given the significance of the random effects; a smaller AIC from the multilevel regression than the AIC from OLS regression also suggests multilevel modelling is a better choice.

Multilevel logistic regressions predicting financial inclusion

displays the results of multilevel logistic regression on each indicator of financial inclusion, based on the same modelling setting of Model (7) predicting the composite index, as the composite index of financial inclusion does not suggest a very high level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha <0.70).

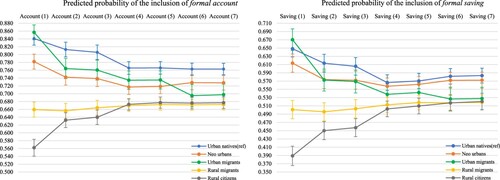

As shown in , statistics from multilevel logistic regressions suggest that compared to urban natives, other hukou holders are less financially included, although it varies by the specific aspect of financial inclusion. For formal account, estimates suggest that rural hukou holders are less included, regardless of whether they are migrants or not. As shown when covariates are controlled, the odds of neo-urbans (OR = 0.982, P > 0.05), urban migrants (OR = 0.442, P < 0.05), rural migrants (OR = 0.615, P < 0.05), and rural residents (OR = 0.637, P < 0.05) are all smaller than that of urban natives, but only rural households show statistically significant differences on this aspect. A similar pattern is also found in formal saving, whereas the two urban hukou holders, regardless of being migrants or having obtained the native hukou, display no statistical differences when compared to the urban natives.

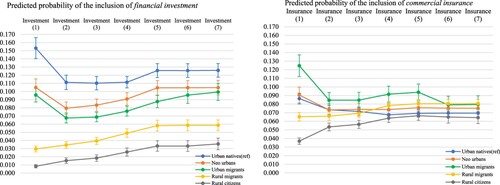

For financial investment, rural migrants, and rural citizens are found to be approximately 26%, 66%, and 82% – significantly lower than urban natives regarding the odds of being engaged. Urban migrants demonstrate about 20% higher in the odds of being included than urban natives, which however, is not statistically significant. This suggests that the differences between rural and urban are more apparent than being a native or migrant. For commercial insurance, none of the hukou types display any significant difference with urban natives, although the statistics suggest that except for rural migrants, the rest three hukou holders are slightly less included regarding commercial insurance. The plausible explanation could be that the insurance system in China is still underdeveloped, although the demand is high (Akhter, Pappas, and Khan Citation2020).

Compared to urban natives, other hukou holders all display lower odds of inclusion in formal credit, which is only significant for urban migrants (OR = 0.570, P < 0.01) and rural migrants (OR = 0.811, P < 0.05). Whereas for informal credit, except urban migrants, the other hukou holders are statistically more included than urban natives.

Both city and province development impose significant influence on household inclusion. Specifically, compared with households living in small cities, households in large cities are more likely to be included and less reliant on informal credit. The increased odds in being included to formal account, financial investment, and formal credit are about 43%, 82%, and 37%, respectively. The decreased reliance on informal credit (about 34%) is in line with the inclusion of increased inclusion of formal credit in large cities. Households in more economically developed provinces are more included, especially on financial investment (OR = 1.373, P < 0.05) and formal credit (OR = 1.381, P < 0.05), and less reliant on informal credit (OR = 0.753, P < 0.05). Random effects coefficients on province and city development are systematically significant on the six financial inclusion indicators, suggesting that the variations of financial inclusion on each aspect can also be explained by the development difference of the two macro factors, especially the city.

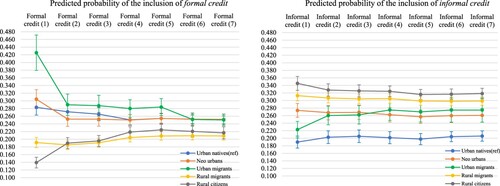

Trends and dynamics of the predicted probability of inclusion on each indicator is also provided to make it visually comparable to the composite index. As shown in , trends of the predicted probability of formal account and formal saving are the closest to that of the composite index: gaps between hukou holders gradually fan in with the inclusion of demographics, financial literacy, and SES indicators, and stabilised with the inclusion of macro-level development indicators. The disparity among hukou holders becomes much smaller in the full model, but hukou is still significant in explaining the disparity, especially for formal account.

For financial investment and commercial insurance (in ), the patterns differ from each other and the inclusion index. For financial investment, both rural-urban and native-non-native divides are significant, which also remains significant with the inclusion of city and province development. But the disparity in commercial insurance among hukou holders has largely disappeared with the inclusion of demographics and SES measured at the household head level. Lastly, for formal credit and informal credit (in ), the gap of formal credit between urban hukou holders has largely diminished once demographics and SES indicators are included, and urban migrants are no longer the most included once city development is included. The disparity between the urban and rural remains on formal credit, which, however, is small. The reliance on informal credit among the five hukou holders is the opposite of their reliance on formal credit.

Above all, the significance of the main effects of hukou hierarchy on formal account, formal saving, financial investment, and informal credit suggest that Hypothesis 1 cannot be rejected. Given that both city development and province development can increase the level of inclusion of financial investment and formal credit while decreasing the reliance on informal credit, Hypothesis 2 cannot be entirely rejected.

Inspecting the cross-level effects on financial inclusion

Estimates in the multilevel logistic regressions () suggest that all types of hukou holders living in large cities are more included, and the modifying effect varies by hukou types as well as financial inclusion indicators. To provide a tangible way to approach the cross-level effects, figures of the predicted probability of inclusion of the six indicators are displayed from to .

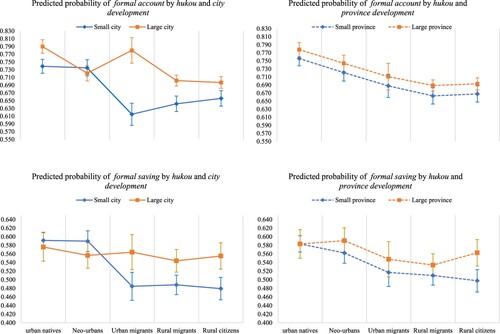

Figure 6. Cross-level effects of hukou, city and province development on formal account and formal saving.

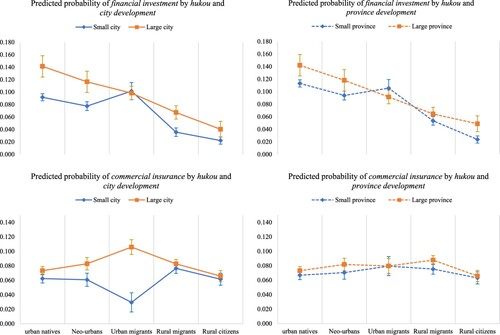

Figure 7. Cross-level effects of hukou, city and province development on financial investment and commercial insurance.

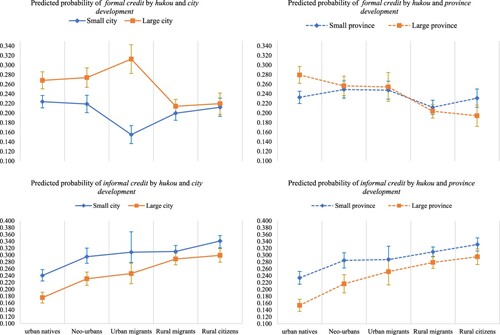

Figure 8. Cross-level effects of hukou, city and province development on formal credit and informal credit.

Starting from the two traditional measures of financial inclusion, as shown in , urban natives, urban migrants, and rural migrants when living in large cities and rural citizens living in rural areas administrated by large cities, their inclusion of formal account is significantly higher than their peers in small cities. The positive modifying effects of city development are the most significant for urban migrants; that is, urban migrants benefit the most from living in large cities regarding the inclusion of formal account. By contrast, living in large cities does not lead to higher inclusion for neo-urbans; instead, they are relatively less included than the other two urban hukou holders, sharing no significant difference with rural migrants or rural citizens in rural areas. However, the modifying effect of city development on formal saving is different. The inclusion of formal saving has been significantly increased for the two migrant households and rural citizens; the disparity on formal saving between local hukou holders and those do not disappear in large cities. No significant modifying effects of province development is found on formal account; only positive modifying effect is found on rural citizens regarding formal saving.

Regarding the inclusion of financial investment and commercial insurance, the two indicators requiring a certain amount of financial literacy, the modifying effects of city and province development also vary by hukou. As displayed in , the two macro-level factors work very much alike as moderators: except urban migrants, other types of hukou holders are relatively more engaged in financial investment in large cities and provinces; also, the inclusion differences between different hukou holders are primarily in line with the hukou hierarchy. City development can significantly increase the inclusion of commercial insurance for urban migrants, but not for urban natives, rural migrants, and rural citizens; positive but not significant modifying effect of province development is found.

Both city and province development impose significant moderating effects on formal credit and informal credit, as shown in . The three urban hukou holders, especially the urban migrants, are relatively more included with city development than the two rural hukou holders, leading to the increased disparity between the rural and urban. Province development also enlarges the inclusion disparity to formal credit between the most socially included and the least socially included hukou holders--the urban natives and the rural citizens. Province development has pretty small and insignificant effects on formal credit for neo-urbans, urban and rural migrants. For informal credit, the main effects of hukou hierarchy are overwhelmingly larger than the modifying effects of two macro-level factors. However, the rural hukou holders are relatively more reliant on informal credit than other hukou holders in large provinces, and are less included on formal credit.

The modifying effects of the two macro factors, especially city development, have implied both the Matthew effect – the already included become more included – and the spill-over effect of economic development. Urban native households living in large cities, their inclusion level on formal account, financial investment, and formal credit are significantly higher than their peers living in small cities. Urban migrants and rural migrants are more included on formal account and formal saving; however, the disparity of the inclusion level on commercial insurance and formal credit between these two migrants are relatively increased with the development of cities. Thus, Hypothesis 1 (Financial inclusion is stratified by hukou hierarchy via institutional barriers and non-local discrimination mechanism) is not rejected. But it’s worth noting that the pattern of distinction is not as exact as the hukou hierarchy proposed and illustrated in . Hypothesis 2 (economic development at the province and city level moderates how hukou hierarchy impacts financial inclusion) cannot be rejected, either, because city and province development moderate the effects of hukou on financial inclusion, with moderating effects varying across different indicators of financial inclusion.

Conclusions and discussion

Based on the new typology of hukou, this paper uses 24,034 households from China Household Financial Studies 2013 to investigate the determinants for household financial inclusion as well as the modifying effects of economic development. The conclusions drawn are as follows.

First, financial inclusion disparity derives from the rural-urban divide as well as from the division between being native and non-native. Predicted values of the composite index of financial inclusion suggest that except for the neo-urbans, urban migrants, and rural migrants have all significantly reported a lower level of financial inclusion. This is supported by the logistic estimates on account ownership and savings, in addition to being partly supported by estimates on financial investment engagement. Second, these disparities based on hukou can be accentuated by economic development, especially between rural and urban hukou holders. Neither demographics, household SES, financial literacy, nor human capital can fully explain the inclusion disparity.

The modifying effect of economic development is also significant: although account ownership, financial investment participation, and formal credit use are significantly increased in large cities while saving disparity decreased between the rural and urban, the inclusion gap between the two migrant categories on account ownership, commercial insurance purchase, and formal credit use. Similarly, province development can significantly increase the inclusion of financial investment and formal credit and diminish the saving disparity between the urban areas and rural areas. Yet, it can also increase the disparity in the inclusion to formal credit. Urban migrants’ inclusion to formal account, purchases of commercial insurance, and inclusion to formal credit can be significantly increased, although estimates show that they do not enjoy the same advantage in financial investment. Rural migrants can only increase savings and are more reliant on informal credit on more developed provinces.

These findings provide several implications for improving household financial inclusion in China, especially under the global trend of ‘financialisation’. First, reforms to the hukou system should be one of the priorities of the government’s work on social justice. The disparity in financial inclusion between the rural and urban hukou holders further reflects the disparity in social justice and equality between the rural and urban economic development caused by hukou division. In the 1950s, the extreme socioeconomic circumstances can establish the rationale of rural-urban division via hukou (Krueger Citation1996). However, today, it is in gradual hukou reforms – separating welfare provisions from hukou (Peng, Zhao, and Guo Citation2009) – that is essential for the government to guarantee the steady success of the social and economic transition in China (Cai, Du, and Wang Citation2001). Furthermore, this can also diminish the time spent by migrants on the ‘floating’ or ‘circular migration’, increasing the efficiency of 'semi-urbanisation' (Xia and He Citation2017) and accelerating rural-urban integration.

Secondly, economic development is still a priority of the Chinese government. Since financial inclusion is generally higher in the more developed provinces and cities, integrating different economic belts in the east and west of China can help improve financial inclusion. For instance, providing more fiscal investment for less developed provinces and small cities, where the habitats and hometowns of migrant individuals and households are located. This is in line to the hukou policy – making the medium and small cities more accessible for migrants. Third, policies to alleviate discriminations caused by hukou division is needed, especially in large cities. Better consumer protection and regulations of the financial services markets to deal with discriminations against migrants and neo-urbans and will help build up consumers’ trust and confidence, which empowers consumers to equally benefit from financial inclusion (Benston Citation2000; Malady Citation2016). Fourth, as human capital and financial literacy can largely diminish the inclusion disparities based on hukou, the government should improve the educational opportunities and resources in rural and less developed areas.

However, this research has two main limitations. First, the criterion of city and province development might not be able to measure multifaceted economic development. Studies combining more detailed community characteristics, such as per capita GNP, employment rate, education, and medical health resources, could better capture city and province development. Second, the association between financial inclusion and hukou hierarchy could be reversed; that is, financial inclusion can increase the rise of hukou hierarchy. Further research investigating the dynamics between hukou hierarchy and financial inclusion could be insightful.

Despite these limitations, this research has done two firsts. It is the first paper to propose an updated hukou typology to satisfy the academic need for more complex measures of hukou development. Also, it is the first to investigate how macro-level factors can moderate how hukou division affects financial inclusion at the household level. Both these two firsts align with the diversified economies and relatively self-sufficient and self-interested local accountability and regional disparities in China. This paper also contributes to the literature on rural-urban integration and social inclusion and (in)equality from the perspective of financial inclusion, which has become increasingly important in modern societies.

Availability of data and material

This paper uses data from the China Household Financial Survey, and this data is publicly available.

Acknowledgement

The author wants to express appreciation to the two anonymous reviewers for the constructive comments, and to Professor Maria Iacovou, Dr Jacques Wels, Professor Yang Hu, Dr Rob Gruijters, and Kevan Kenney for the very help suggestions for drafting this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Afridi, F., S. X. Li, and Y. F. Ren. 2015. “Social Identity and Inequality: The Impact of China’s hukou System.” Journal of Public Economics 123: 17–29. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.12.011.

- Ajide, F. M. 2020. “Financial Inclusion in Africa: Does it Promote Entrepreneurship?” Journal of Financial Economic Policy 12 (4): 687–706. doi:10.1108/JFEP-08-2019-0159.

- Akhter, W., V. Pappas, and S. U. Khan. 2020. “Insurance Demand in Emerging Asian and OECD Countries: A Comparative Perspective.” International Journal of Social Economics 47 (3): 350–364. doi:10.1108/IJSE-08-2019-0523.

- Barth, J. R., G. Caprio, and T. Phumiwasana. 2009. “The Transformation of China from an Emerging Economy to a Global Powerhouse.” In China’s Emerging Financial Markets, edited by J. R. Barth, J. A. Tatom, and G. Yago, 73–110. New York: Springer.

- Benston, G. J. 2000. “Consumer Protection as Justification for Regulating Financial-Services Firms and Products.” Journal of Financial Services Research 17 (3): 277–301. doi:10.1023/A:1008154820305.

- Berry, C. 2015. “Citizenship in a Financialised Society: Financial Inclusion and the State Before and After the Crash.” Policy and Politics 43 (4): 509–525. doi:10.1332/030557315X14246197892963.

- Cai, F., Y. Du, and M. Wang. 2001. “Hukou Institution and Labour Market Protection [Huji zhidu yu laodongli shichang baohu].” Economic Studies 12 (4): 13–15. http://www.cesgw.cn/cn/gwqk.aspx?m=20100918141426890802.

- Calvet, L. E., J. Y. Campbell, and P. Sodini. 2009. “Measuring the Financial Sophistication of Households.” American Economic Review 99 (2): 393–398. doi:10.1257/aer.99.2.393.

- Chai, S., Y. Chen, B. Huang, and D. Ye. 2019. “Social Networks and Informal Financial Inclusion in China.” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 36 (2): 529–563. doi:10.1007/s10490-017-9557-5.

- Chan, K. W. 2010. “The Household Registration System and Migrant Labor in China: Notes on a Debate.” Population and Development Review 36 (2): 357–364. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00333.x.

- Chan, K. W., and W. Buckingham. 2008. “Is China Abolishing the hukou System?” The China Quarterly 195: 582–606. doi:10.1017/S0305741008000787.

- Chen, J. 2013. “Perceived Discrimination and Subjective Well-being among Rural-to-urban Migrants in China.” Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 40(1), 131–156. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/jrlsasw40&i=131.

- Chen, C., and C. C. Fan. 2016. “China’s hukou Puzzle: Why Don’t Rural Migrants Want Urban hukou?” China Review 16 (3): 9–39. http://muse.jhu.edu/article/634713.

- Chen, L. Z., W. M. Hu, R. Szulga, and X. Zhou. 2018. “Demographics, Gender and Local Knowledge — Price Discrimination in China’s car Market.” Economics Letters 163: 172–174. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2017.11.026

- Chen, Z., and M. Jin. 2017. “Financial Inclusion in China: Use of Credit.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 38 (4): 528–540. doi:10.1007/s10834-017-9531-x

- Choi, W. I., H. Shi, Y. Bian, and H. Hu. 2018. “Development of Commercial Health Insurance in China: A Systematic Literature Review.” BioMed Research International 2018: 1–18. doi:10.1155/2018/3163746.

- The CPC Central Committee and the State Council. 2014. National Plan on New Urbanization (2014–2020) [Guojia xinxing cheng-shihua guihua (2014–2020 nian].

- Deng, Z. H., and Y. W. Law. 2020. “Rural-to-urban Migration, Discrimination Experience, and Health in China: Evidence from Propensity Score Analysis.” PLOS ONE 15 (12): 1–20. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0244441.

- Dou, G., Q. Wang, and X. Ying. 2018. “Reducing the Medical Economic Burden of Health Insurance in China: Achievements and Challenges.” Bioscience Trends 12 (3): 215–219. doi:10.5582/bst.2018.01054

- Du, L. J. 2004. “Qianxi Shanghai shi jinnian lai dui wailai liudong renkou de zhengce bianqian [An Analysis of the Changes in Shanghai’s Policies Against Floating Populaiton in Past Decade].” Nanfang Renkou (South China Population) 19 (4): 30–38. http://www.cqvip.com/qk/82549x/200404/11431026.html.

- The Economist. 2021. Can China’s Long Property Boom Hold? The Economist. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2021/01/25/can-chinas-long-property-boom-hold.

- Fan, C. C. 2008. “Migration, Hukou, and the City.” In China Urbanizes: Consequences, Strategies, and Policies, edited by S. Yusuf and A. Saich, 65–89. Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

- Feltenstein, A., and S. Iwata. 2005. “Decentralisation and Macroeconomic Performance in China: Regional Autonomy has its Costs.” Journal of Development Economics 76 (2): 481–501. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2004.01.004

- Finke, M. S., and S. J. Huston. 2003. “The Brighter Side of Financial Risk: Financial Risk Tolerance and Wealth.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 24: 233–256. doi:10.1023/A:1025443204681

- Fligstein, N., and A. Goldstein. 2015. “The Emergence of a Finance Culture in American Households, 1989–2007.” Socio-Economic Review 13 (3): 575–601. doi:10.1093/ser/mwu035.

- Fungáčová, Z., and L. Weill. 2015. “Understanding Financial Inclusion in China.” China Economic Review 34: 196–206. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2014.12.004.

- Gong, X. 2005. Diminishing the Function of hukou in Social Distribution. China Economic Paper.

- Grimm, M., and A. L. Paffhausen. 2015. “Do Interventions Targeted at Micro-Entrepreneurs and Small and Medium-Sized Firms Create Jobs? A Systematic Review of the Evidence for low and Middle Income Countries.” Labour Economics 32: 67–85. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2015.01.003.

- Huang, Y. Q., and F. Guo. 2017. “Welfare Programme Participation and the Wellbeing of Non-Local Rural Migrants in Metropolitan China: A Social Exclusion Perspective.” Social Indicators Research 132 (1): 63–85. doi:10.1007/s11205-016-1329-y.

- Kaiser, H. F. 1974. “An Index of Factorial Simplicity.” Psychometrika 39 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1007/BF02291575.

- Krueger, A. O. 1996. “Political Economy of Agricultural Policy.” Public Choice 87 (1–2): 163–175. doi:10.1007/BF00151734.

- Langley, P.. 2008. The Everyday Life of Global Finance: Saving and Borrowing in Anglo-America. Oxford: Oxford university press.

- Li, L., S. Li, and Y. Chen. 2010. “Better City, Better Life, but for Whom?: The hukou and Resident Card System and the Consequential Citizenship Stratification in Shanghai.” City, Culture and Society 1 (3): 145–154. doi:10.1016/j.ccs.2010.09.003.

- Li, N., and Y. Qian. 2018. “The Impact of Educational Pairing and Urban Residency on Household Financial Investments in Urban China.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 39 (4): 551–565. doi:10.1007/s10834-018-9579-2.

- Lin, D., X. Li, B. Wang, Y. Hong, X. Fang, X. Qin, and B. Stanton. 2011. “Discrimination, Perceived Social Inequity, and Mental Health among Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China.” Community Mental Health Journal 47 (2): 171–180. doi:10.1007/s10597-009-9278-4.

- Liu, Y., W. Deng, and X. Song. 2018. “Influence Factor Analysis of Migrants’ Settlement Intention: Considering the Characteristic of City.” Applied Geography 96: 130–140. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2018.05.014.

- Malady, L. 2016. “Consumer Protection Issues for Digital Financial Services in Emerging Markets.” Banking & Finance Law Review 31 (2): 389–401. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3028371.

- Mugo, M., and E. Kilonzo. 2017. “Community–Level Impacts of Financial Inclusion in Kenya with Particular Focus on Poverty Eradication and Employment Creation.” Central Bank of Kenya (13): 1–7. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2017/04/Matu-Mugo-and-Evelyne-Kilonzo-UN-SDGs-Paper5May2017-Kenya-Financial-Inclusion.pdf.

- OECD. 2008. Growing Unequal ? Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries.

- Peng, X., D. Zhao, and X. Guo. 2009. “The Reform of China’s Household Registration System: A Political Economic View [Huji zhidu gaige de zhengzhi jingjixue sikao].” Fudan Journal (Social Sciences Edition) 3 (1): 1–11. doi:10.3969/j.issn.0257-0289.2009.03.001.

- Qian, J., L. Qian, and H. Zhu. 2012. “Representing the Imagined City: Place and the Politics of Difference During Guangzhou’s 2010 Language Conflict.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 43 (5): 905–915. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.04.004.

- Smart, A., and J. Smart. 2001. “Local Citizenship: Welfare Reform Urban/Rural Status, and Exclusion in China.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 33 (10): 1853–1869. doi:10.1068/a3454.

- Snijders, T. A. B., and R. J. Bosker. 1999. An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. London: Sage.

- Solinger, D. J. 1999. “Citizenship Issues in China’s Internal Migration: Comparisons with Germany and Japan.” Political Science Quarterly 114 (3): 455–478. doi:10.2307/2658206.

- Song, Y. 2014. “What Should Economists Know About the Current Chinese hukou System?” China Economic Review 29: 200–212. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2014.04.012.

- Stein, L. C. D., and C. Yannelis. 2020. “Financial Inclusion, Human Capital, and Wealth Accumulation: Evidence from the Freedman’s Savings Bank.” The Review of Financial Studies 33: 5333–5377. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhaa013.

- Tian, F. F., Y. Qian, and Z. C. Qian. 2018. “Hukou Locality and Intermarriages in Two Chinese Cities: Shanghai and Shenzhen.” Research In Social Stratification And Mobility 56: 12–20. doi:10.1016/j.rssm.2018.06.001.

- Tsui, K.-Y., and Y. Wang. 2008. “Decentralisation with Political Trump: Vertical Control, Local Accountability and Regional Disparities in China.” China Economic Review 19 (1): 18–31. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2006.12.003.

- Turner, B. 1999. “The Sociology of Citizenship.” In Classical Sociology, edited by B. Turner, 262–275. Sage. doi:10.4135/9781446219485.

- Turner, B. 2012. “The Sociology of Citizenship.” In Classical Sociology, 262–275. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Van der Zwan, N. 2014. “Making Sense of Financialisation.” Socio-Economic Review 12 (1): 99–129. doi:10.1093/ser/mwt020.

- Van Rooij, M., A. Lusardi, and R. Alessie. 2011. “Financial Literacy and Stock Market Participation.” Journal of Financial Economics 101 (2): 449–472. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.03.006.

- Wang, F.-L.. 2005. Organising Through Division and Exclusion: China’s hukou. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- Wang, C. 2006. “A Study of Floating Rural People’s “Semi-Urbanization [Nongcun liuong renkou de “banchengshihua” wenti yanjiu].” Sociological Studies (5): 107–122. http://www.cqvip.com/QK/80772X/20065/23017871.html.

- Wang, F.-L.. 2010. “Conflict, Resistance and the Transformation of the hukou System.” In Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance. 3rd ed., Vol. 80, edited by E. Perry and M. Selden, 80–100. Routledge.

- Wang, H., F. Guo, and Z. Cheng. 2015. “Discrimination in Migrant Workers’ Welfare Entitlements and Benefits in Urban Labour Market: Findings from a Four-City Study in China.” Population, Space and Place 21 (2): 124–139. doi:10.1002/psp.1810.

- Wong, Z., R. Li, Y. Zhang, Q. Kong, and M. Cai. 2021. “Financial Services, Spatial Agglomeration, and the Quality of Urban Economic Growth–Based on an Empirical Analysis of 268 Cities in China.” Finance Research Letters 43, doi:10.1016/j.frl.2021.101993.

- Wu, W. 2004. “Sources of Migrant Housing Disadvantage in Urban China.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 36 (7): 1285–1304. doi:10.1068/a36193.

- Wu, X., and D. J. Treiman. 2007. “Inequality and Equality Under Chinese Socialism: The hukou System and Intergenerational Occupational Mobility.” American Journal of Sociology 113 (2): 415–445. doi:10.1086/518905.

- Xia, Z., and X. He. 2017. “China’s Semi-Industrial, Semi-Agricultural Mode and Incremental Urbanization [Bangong bangeng yu zhongguo jianjin chengshihua moshi].” Chinese Social Sciences 12: 117–137. http://www.cqvip.com/qk/81908x/201712/674264877.html.

- Yan, H. 2008. New Masters, New Servants: Migration, Development, and Women Workers in China. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Yao, R., and Y. Xu. 2015. “Chinese Urban Households’ Security Market Participation: Does Investment Knowledge and Having a Long-Term Plan Help?” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 36 (3): 328–339. doi:10.1007/s10834-015-9455-2.

- Zhang, L. 2001. Strangers in the City: Reconfigurations of Space, Power, and Social Networks Within China’s Floating Population. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Zhang, J., X. Li, X. Fang, and Q. Xiong. 2009. “Discrimination Experience and Quality of Life among Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China: The Mediation Effect of Expectation-Reality Discrepancy.” Quality of Life Research 18 (3): 291–300. doi:10.1007/s11136-009-9454-6.

- Zhang, H., and Z. Yin. 2016. “Financial Literacy and Household’s Financial Exclusion in China: Evidence from CHFS Data [Jinrong zhishi he zhongguo jiating de jinrong paichi——jiyu CHFS shuju de shizheng yanjiu].” Financial Studies 433(7): 80–95. http://www.cqvip.com/qk/97926x/201607/669770190.html.