ABSTRACT

Both today and under Gaddafi’s authoritarian rule, externalised migration controls have played a crucial role in EUropean irregular mobility governance across the Central Mediterranean. Offloading migration management on Tripoli is puzzling due to the fragility of its institutions, the ill-preparedness of its security forces, and widespread abuse against migrants. Why have European member states and EU institutions relapsed to relying on Libyan forces to govern irregular migration? In this paper, we argue that the EU has failed through the migration crisis in the Central Mediterranean by drawing on already established albeit ineffective and contentious policy tools. The collapse of Libya’s state apparatus, European Court of Human Rights’ censure of Italy’s illegal pushbacks and public opinion pressure temporarily displaced but did not fundamentally change EUrope’s restrictive approach to irregular mobility governance. While some new and less restrictive border enforcement policies were developed in response to the soaring death toll, this humanitarian turn was short-lived. By combining the mechanism of failing forward with institutionalist insights, our concept of failing through explains why the EU and its member states soon backslid into pre-existing institutional arrangements like bilateral agreements with Libyan authorities notwithstanding their problematic legal, ethical and political implications.

1. Introduction

The 2008 Treaty on Friendship, Partnership and Cooperation (TFPC) between Italy and Libya committed the two parties to cooperate in curbing irregular maritime migration through the joint patrolling of Libyan waters and Rome’s provision of boats and surveillance equipment to autocrat Muhammar Gaddafi’s security forces. The TFCP was vocally denounced by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and questioned by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which sanctioned Italy for violating the non-refoulement principle by pushing back asylum seekers where their fundamental rights would be threatened (Moreno-Lax Citation2018; Bialasiewicz Citation2012).

Ten years later, Italy signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Tripoli’s Government of National Accord (GNA), obtaining its support in preventing migrants from crossing the Mediterranean in exchange for financial aid (Giuffré Citation2020; Maccanico Citation2020; Liguori Citation2019). Those leaving Tripoli’s coast would be intercepted and returned ashore by a newly-formed Libyan Coast Guard and Navy (LCGN), trained by Italian security forces and the European Union (EU) mission EUNAVFOR Med (Muller and Slominski Citation2020; Cusumano Citation2019). LCGN operations have been widely criticised as ‘pullbacks’ (Pijnenburg Citation2020), ‘border control by proxy’ (Panebianco Citation2021, Moreno-Lax Citation2018) or even ‘kidnappings’ (Tazzioli and De Genova Citation2020), and identified as a factor increasing the deadliness of irregular crossings (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020a). Notwithstanding evidence of widespread abuse against migrants in detention camps and connections between LCGN officials and human smugglers (Zandonini Citation2021; Maccanico Citation2020; UN Mission to Libya Citation2018), European training of, funding for, and political support to Tripoli’s onshore containment and maritime interdiction operations have continued to the present day.

This relapse to externalised migration controls is puzzling since the EU often prides itself as a defender of international law and a ‘normative power’ (Manners Citation2002), and European leaders have repeatedly declared their firm commitment to tackle the humanitarian crisis in the Central Mediterranean. The 2014 Lampedusa tragedy, for instance, was denounced by then European Parliament President Schulz as ‘a stain on our European conscience’ (Bosilca, Stenberg and Riddervold Citation2020). More recently, EU Commission President Von der Leyen has called for a ‘human and humane’ approach to migration, stressing that ‘we must preserve the right to asylum and improve the situation of refugees’ (EEAS Citation2020). Besides contradicting the EU’s own commitments and being both ethically questionable and at risk of judicial review by the ECtHR, externalisation is also potentially ineffective due to the volatility of the political situation in Libya and the weakness of the GNA, which can hardly serve as an effective partner in bilateral migration governance. Why, then, have EU institutions and member state governments (hereinafter EUrope) consistently relied on Libyan forces to manage irregular migration?

As noted by Niemann and Zaun in the introduction (Niemann and Zaun Citation2023), EU external migration governance has witnessed a formidable acceleration after the ‘refugee crisis’. Czaika, Erdal, and Talleraas (Citation2023), conceptualise EU migration governance as a policy mix bound together by spatial, categorical and temporal interdependencies between external migration-relevant policies both within member states and the EU. In the EU, migration governance is increasingly conducted in parallel through the EU Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) and Area of Freedom, Security, and Justice, two policy areas that feature growing institutional interactions (Bergmann and Müller Citation2023).

In this article, we explain EUrope’s relapse to externalisation through a mechanism we refer to as ‘failing through’. In developing this new concept, we combine insights from Jones, Keleman, and Meunier’s (Citation2016) notion of ‘failing forward’ with institutionalist mechanisms linked to organisations’ path dependent behaviour (Ansell Citation2021). While the collapse of Libya’s state institutions, the European Court of Human Rights’ censure of Italy’s illegal pushbacks and public opinion pressure to stop casualties at sea temporarily prompted more permissive border enforcement policies, these events did not fundamentally change European irregular mobility governance. Instead, due to institutional stickiness and path dependency, EUrope soon backslid into pre-existing institutional arrangements like bilateral agreements with Libyan authorities despite their problematic legal, ethical and political implications.

This resort to Libyan security forces to curb irregular migration reflects EUrope’s tendency to ‘muddle through crisis through path-dependent incremental responses building on pre-existing institutional architectures’ and develop policy solutions ‘extrapolated from and mediated by pre-established institutional frameworks’ (Riddervold, Trondal, and Newsome Citation2021, 9–10). We innovate on this argument by showing that, in the case of irregular migration from Libya, EUrope has not only muddled through, but in fact failed through, enacting a short-lived humanitarian turn before relapsing to pre-existing migration governance tools. By tying access to the EU common market and financial support to cooperation in curbing irregular flows, the EU has effectively co-opted countries at its Southern and Eastern borders into an externalised migration control regime (Bialasiewicz Citation2012). Over the past decades, externalisation has consolidated as the default instrument of EUropean irregular mobility governance. Consequently, the disruptions caused by the overthrow of Gaddafi’s regime, the ECtHR Hirsi decision, and the humanitarian crisis at sea only temporarily displaced but did not fundamentally alter the predominance of the externalisation paradigm, which was soon extended to Libya’s GNA. Consistent with institutionalist expectations, entrenched governance frameworks and policy responses like externalised migration management across the Mediterranean have proven resilient to external shocks.

According to Stutz, EUropean external migration governance is shaped primarily by the state of democracy in third countries and their existing relations and economic dependence with the EU (Stutz Citation2023). These findings confirm that Libya is arguably a least likely case for effective externalisation to take place. As a post-authoritarian country fraught with civil strife that has not signed the 1953 Refugee Convention, Tripoli offers no opportunities to apply for international protection, and even criminalises irregular migration with unlimited detention in camps where human rights violations are systematic (Giuffré Citation2020; Liguori Citation2019; Moreno-Lax Citation2018). Arrangements aimed at withholding or returning migrants to Libya have been denounced by various international organisations, including the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), as well as the ECtHR. Moreover, unlike Turkey or Morocco, Tripoli's GNA lacks the capabilities to serve as a reliable partner in migration governance, as it controls only a parcel of Libya’s territory and long appeared doomed to lose the ongoing civil war (Baldwin-Edwards and Lutterbeck Citation2019; Strazzari and Grandi Citation2019). These normative, legal, and strategic considerations make Tripoli an especially ill-suited candidate for the externalisation of irregular mobility management.

Several studies have examined migration governance across the Central Mediterranean. Most existing literature has concentrated on irregular maritime crossings after the Arab Uprisings and their legal, political, and humanitarian implications (Baldwin-Edwards and Lutterbeck Citation2019; McMahon and Sigona Citation2018). Scholars have investigated a wide array of initiatives, ranging from the maritime missions launched by the EU (Bosilca, Stenberg, and Riddervold Citation2020; Cusumano Citation2019) and NGOs (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020b; Cuttitta Citation2020, Stierl Citation2018) to attempts at combatting human smuggling (Perkowski and Squire Citation2019) and reforming the EU asylum system (Scipioni Citation2018; Servent and Trauner Citation2014). Recent literature has identified Europe’s externalised migration governance as a form of ‘orchestration’ (Muller and Slominski Citation2020), framing reliance on Libyan forces as a novel expedient for Italy, Malta and the EU at large to circumvent legal constraints and escape ECtHR jurisdiction (Pijnenburg Citation2020; Panebianco Citation2021; Moreno-Lax Citation2018). While some scholars brought history back in by forcefully highlighting similarities with European countries’ colonial past (Mainwaring and De Bono Citation2020), fewer studies systematically examine change and continuity in the institutional arrangements underlying mobility management across the Central Mediterranean over the last decades.

By focusing on the 2000–2020 timeframe, our study provides a novel contribution to the existing debate. Specifically, we highlight the existence of a failing through mechanism, whereby functionally insufficient, lowest common denominator attempts at solving contemporary challenges (failing forward) interact with path dependency in explaining the enduring prominence of externalisation. In doing this, our work simultaneously contributes to migration studies and the debate on how phenomena widely perceived as ‘crises’ affect EU integration. By highlighting the tendency of sticky modes of governance to relapse to business as usual after being temporarily disrupted by external shocks, our findings highlight the need to combine various theoretical approaches to organisational continuity and change to understand the evolution of European government structures. Moreover, externalising migration control on Libyan authorities has likely worsened the death toll of irregular crossings (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020a; McMahon and Sigona Citation2018) and exacerbated the human rights violations faced by those returned to or withheld in detention camps (IOM Citationundated; UN Mission to Libya Citation2018). Consequently, examining EUropean migration governance across the Central Mediterranean and its resilience to major disruptions also carries important policy and normative implications.

The article is divided as follows. Section two outlines our theoretical and methodological approach. We then examine European irregular mobility governance across the Central Mediterranean from 2000-2020, identifying three different phases. In line with Niemann and Zaun’s Introduction to this special issue (Citation2023), by migration policy, we mean ‘any policy that aims to manage migration outside the territory of EU member states.’ Focusing on the EUrope’s agreements with Libya, we moreover explore formal instruments that are adopted to regulate migration by engaging ‘third parties in the enforcement of EU borders’ (Niemann and Zaun Citation2023). To that end, section three describes the inception of the externalisation agreements culminated into the 2008 TFPC between Italy and Gaddafi’s Libya. Section four illustrates how this externalised migration governance regime collapsed, identifying the overthrow of Gaddafi’s rule, the ECtHR Hirsi decision and the outcry caused by deaths at sea as the three crucial shocks temporarily disrupting the externalisation paradigm in favour of a less restrictive approach. As shown by section five, however, this humanitarian turn was quickly sidelined by renewed attempts to offload the burden of containing migratory flows onto Libyan authorities. Section six and the ensuing conclusions examine the findings against the backdrop of our argument and outline some avenues for future research.

2. Theoretical Framework and methods: Failing through and European migration governance

The many ‘crises’ Europe faced in recent years prompted a scholarly debate on how turbulence affects EU integration and organisational change and continuity more broadly. To systematize these discussions, Riddervold, Trondal, and Newsome (Citation2021) distinguished three ways in which crises affect EU integration, each underpinned by different mechanisms; ‘breaking down’, ‘heading forward’, and ‘muddling through’. They argue that, over time, EU response to crises has showcased occasional integration spurts. Overall, however, the EU often muddles through crisis through ‘path-dependent incremental responses building on pre-existing institutional architectures’ and develops policy solutions ‘extrapolated from and mediated by pre-established institutional frameworks’ (Riddervold, Trondal, and Newsome Citation2021, 9–10).

In the following, we add to this literature by arguing that none of these mechanisms can fully capture continuity and change in European irregular migration governance across the Central Mediterranean. The fact that EUrope reverted to the externalisation paradigm after a short humanitarian turn, we argue, can neither be seen as heading forward nor as a form of muddling through. This pattern can only be captured by a two-step failing through mechanism, whereby functionally insufficient, lowest common denominator attempts at solving contemporary challenges linked to member states’ interests (failing forward) interact with path dependency in explaining the enduring prominence of externalisation. In the domain of irregular migration governance, the EU has not merely incrementally muddled through, but also failed through crisis: it temporarily developed new policies in response to particular events, but, due to path dependencies, it soon reverted to established externalised migration governance tools despite the well-known legal, ethical, and practical challenges attached to this approach.

Our argument combines the institutionalist idea of path dependency with insights from Jones, Keleman and Meunier’s (Citation2016) concept of failing forward. Institutionalist perspectives have traditionally focused on how behavioural patterns within institutions are reproduced over time. A key assumption is that institutions are ‘sticky’ or inertial due to path dependency and through feedback effects, forms of self-reinforcing equilibrium, or ‘“taken for granted” cognitive scripts’ (Ansell Citation2021, 139). This does not mean that institutions determine actors’ behaviour, but only that once institutions are established, actors’ responses and choices will be influenced by prior norms and practices (Pierson Citation2000). Institutionalised path dependencies influence the options perceived as available and will thus ‘favor some decisions and exclude others, eventually, shaping the political outcome’ (Juncos and Pomorska Citation2021, 555). The main factor introduced to explain change from one path to another is the concept of critical junctures, defined as ‘relatively short periods of time during which there is a substantially heightened probability that agents’ choices will affect the outcome of interest’ (Capoccia and Kelemen Citation2007, 348). Although there is a tendency in the literature to see critical junctures as conducive to change, a shock may only lead to minor incremental amendments in institutional structures, or prompt existing institutions to draw on already established patterns in order to deal with an ongoing challenge (Ansell Citation2021). Combining the concepts of critical junctures and path dependency, scholars have also found that even when crises prompt the establishment of new institutions, these are often ‘inspired by structures that had been created before’ (Verdun Citation2015, 231) and copying from previous policies (Bosilca, Stenberg, and Riddervold Citation2020).

Although these patterns of continuity and change are evident in EUropean migration governance, they cannot explain why the EU and its member states relapsed to externalisation-based policy arrangements despite widespread knowledge that these tools are challenging both from a practical and ethical perspective (Cusumano Citation2019; Riddervold Citation2018). To capture these developments, we therefore add insights from Jones, Keleman and Meunier’s (Citation2016) argument that a key way in which the EU deals with crisis is to ‘fail forward’. Building on liberal intergovernmentalism and neo-functionalism, failing forward processes describe the EU’s tendency to gradually integrate further in response to crises. Unlike the institutional perspectives discussed above, Jones et al suggest that interest-maximizing member states tend to agree to new but often insufficient lowest common denominator reforms when seeking to solve a crisis. These lowest common denominator solutions, however, often create functional problems, which therefore create preconditions for a new crisis, yet another insufficient common response, and so forth. In other words, the EU keeps failing forward. Various studies have engaged with the concept of failing forward in different policy domains, including asylum policies (Scipioni Citation2018). What we find, however, is that the EU has only briefly established new policies before relapsing to only slightly revised, ‘failed’ pre-existing ways of governing migration. In other words, the EU did not simply copy old templates, as the concept of path dependence suggest. In the case of irregular migration governance across the Central Mediterranean, the EU did not head forward with new and more long-lasting policies following particular critical junctures, but it did not fail forward in a continuous circle of insufficient integration either.

With our failing through argument, we therefore make a novel contribution to the existing EU integration and governance literature by specifying the mechanisms by which the EU responds to crisis. By exploring continuity and change in EU external migration policies over time we show that, in certain cases, the policy tools introduced in response to perceived crises may be only temporary. Indeed, EUrope has moved forward with some new policy instruments to deal with irregular migration across the Central Mediterranean, not least in the form of naval missions rescuing migrants in danger at sea. However, rather than permanently adapting its approach to the new situation in Libya, EUrope has soon returned to pre-existing, dysfunctional governance tools. Due to path-dependency, the system has in other words not been reformed in a functional way. Instead, in contrast to most accounts in the historical institutionalist tradition, we show how stickiness and path-dependency can also lead to backsliding into pre-existing institutional arrangements rather than locking the EU in paths towards further integration.

To substantiate this argument, we rely on process tracing to diachronically examine EU migration governance in the Central Mediterranean between 2000 and 2020. By helping investigate whether the succession and timing of specific events and decisions coincide with prior theoretically derived expectations, process tracing is vital to study how institutional architectures shape decision-making processes and policy solutions (Beach and Pedersen Citation2013). Specifically, we identify a sequence of three different phases: the inception of an externalised migration governance regime before Gaddafi’s demise, the collapse of this regime in the wake of the Arab Uprisings, the Hirsi decision, as well as public pressure to tackle the humanitarian crisis at sea at sea, and the relapse to only slightly revised externalisation arrangements.

We combine process tracing with content analysis of policy documents, 30 semi-structured interviews with EU officials, Italian Navy and Coast Guard officers, and NGO representatives, as well as the observation of four SHared Awareness and DEconfliction in the Mediterranean (SHADE Med) conferences, organised by the EU and Italy to gather all the key stakeholders involved in migration governance off the coast of Libya.

3. The inception of the externalisation paradigm in the Central Mediterranean

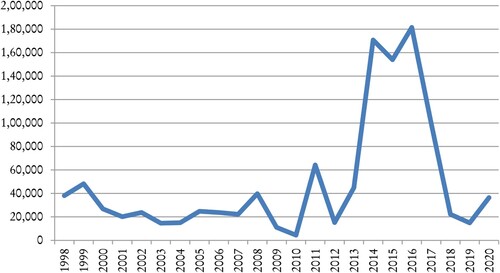

Up until 2001, maritime departures towards Italy mainly occurred from Albania through the Adriatic Sea. Between 1997 and 2008, as illustrated by below, northbound flows from Libya and Tunisia hovered between around 20,000 and 40,000 people each year (Baldwin-Edwards and Lutterbeck Citation2019; Fargues Citation2017).

Figure 1. Irregular seaborne arrivals to Italy and Malta, 1998–2020. Source: International Organization for Migration, UNHCR and Italian and Maltese governments.

Italy’s attempts to co-opt its Southern neighbours in externalised border control efforts date back to the agreements reached with Tunisia in 2003 and 2009 and Libya in 2000, 2003 and 2006 (Liguori Citation2019; Paoletti and Pastore Citation2010). Cooperation with Libya consolidated with the 2008 TFPC signed by Italian Prime Minister Berlusconi and Libya’s autocratic leader Muhammar Gaddafi. In exchange for financial reparations for Italy’s colonial past, Libya accepted cooperating on various issues, including migration governance. Building on the 2006 memorandum, the TFPC committed the two parties to jointly patrolling Libyan territorial waters with boats and surveillance equipment provided by Italy (Liguori Citation2019; Paoletti and Pastore Citation2010). Provisions along these lines were hardly unique to Libya, but were also foreseen in Italian cooperation with Tunisia, as well as the agreements between Spain, Morocco, and Senegal. Tripoli’s entrenched authoritarianism and abysmal human rights record, however, made Italy’s policy especially contentious (Bialasiewicz Citation2012; Paoletti and Pastore Citation2010). Notwithstanding legal dilemmas and evidence of abuses against migrants, the TFPC was widely portrayed as a success and remained in place until the start of Libya’s civil war (Giuffré Citation2020; Liguori Citation2019).

The first joint initiatives developed by the EU at its Southern maritime borders reflect the prevalence of a restrictive approach to irregular mobility. Frontex operation Hermes is a case in point. First deployed in 2007, Hermes was designed as a solidarity mechanism towards the EU member states most affected by migratory flows, but remained focused on ‘coordinated sea border activities to control illegal migration flows from Tunisia towards South of Italy’ (Frontex Citation2011). Due to its narrow mandate, Hermes came under criticism for its inability to conduct search and rescue (SAR) operations (Moreno-Lax Citation2018, 124). SAR was conducted on an occasional basis by Italian security forces, which coordinated with their Libyan counterparts to curb irregular flows. However, as we explain below, one of these operations was eventually condemned by the ECtHR.

4. Externalisation under stress: Europe’s humanitarian turn

In the 2012 decision Hirsi Jamaa and Others vs. Italy, the ECtHR found that Italy had violated article three and four of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) by handing over to Libyan authorities a group of asylum seekers rescued in international waters in 2009. By construing Italian security forces’ action as an illegal pushback, the ECtHR problematised a key aspect of Rome’s externalisation strategy (Giuffré Citation2020; Liguori Citation2019, Moreno-Lax Citation2018). The Italian cabinet then led by Mario Monti committed to revising Italian border control policies accordingly. Rome’s pledge to relinquish illegal pushback ultimately translated into a de facto acceptance of the principle that all those rescued at sea by Italian security forces had to be disembarked on Italian territory to safeguard their right to apply for protection (Cuttitta Citation2020; Cusumano Citation2019).

Irregular migration from Libya did not immediately skyrocket after the 2011 uprisings. Up until 2013, migrants mainly sought to reach Italy from Tunisia. Departures from Libya only gained momentum by mid-2013, when the power vacuum created by the civil war allowed smuggling networks to consolidate their business (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020a; Baldwin-Edwards and Lutterbeck Citation2019). The Hirsi decision and the collapse of Libyan state institutions, however, prevented the immediate re-establishment of an externalised border control regime. In the words of a EU official in DG Home, ‘we tried to apply it to post-Gaddafi Libya, but in 2013 we soon realised that things had blown up, that that there was no government to talk to: the whole strategy had to be reformulated’ (Zandonini Citation2021, authors’ interviews).

In parallel with soaring irregular departures, deaths at sea started to increase as well. The perception of an ongoing humanitarian disaster peaked after two large shipwrecks occurred off Lampedusa in October 2013, forcefully denounced by the pope and other opinion leaders. In response, the cabinet led by Enrico Letta initiated operation Mare Nostrum, an Italian Navy and Coast Guard mission simultaneously seeking to arrest human smugglers, intercept irregular arrivals and conduct proactive rescue operations. In one year of operations, Rome’s Navy and Coast Guard rescued and disembarked in Italy over 150,000 migrants (Cusumano Citation2019).

Italy’s compliance with the Hirsi decision, the power vacuum in Libya and the widespread outcry caused by deaths at sea marked the beginning of a more permissive approach to irregular border crossing. This ‘humanitarian turn’ (Cuttitta Citation2020), however, soon became contentious in both Rome and Brussels. The Italian government hoped to leverage the upcoming European Council presidency to obtain more EU-wide burden sharing. Far from backing Italy, however, other EU members criticised Mare Nostrum as an ‘unintended pull factor encouraging more migrants to attempt the dangerous sea’ (House of Lords Citation2016, 18; Bosilca, Stenberg, and Riddervold Citation2020; Cusumano Citation2019). The compromise reached by the Council led to a suspension of the Italian Navy mission, to be followed by a smaller-scale operation conducted by Frontex, named Triton. In the spring of 2015, Italy obtained the launch of another EU operation – the CSDP military mission EUNAVFOR Med ‘Sophia’ – focused on disrupting human smuggling networks (Bosilca, Stenberg, and Riddervold Citation2020; Riddervold Citation2018; Cusumano Citation2019).

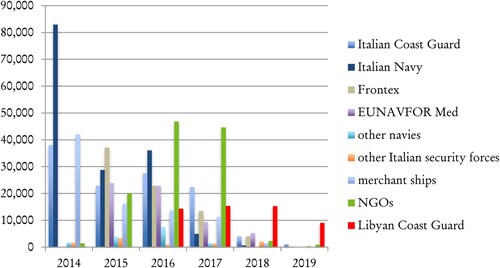

Even if neither missions included SAR in their mandate, Triton and EUNAVFOR Med duly complied with the duty to assist people in distress at sea. As illustrated by and explained more at length in the next section, however, both operations exhibited growing resistance to becoming involved in SAR on a day-to-day basis, fearing that proactive rescue operations would serve as a pull factor of migration. As a result, both Frontex and European navies gradually disengaged from the Southern Mediterranean, withdrawing their assets away from Libyan waters (Cusumano Citation2019; Moreno-Lax Citation2018). The ensuing gap in rescue capabilities was filled by several NGOs, which effectively coordinated with Italian authorities and assisted over 110,000 migrants (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020a, Cuttitta Citation2020; Stierl Citation2018). By 2017, however, non-governmental SAR started to be seen as an obstacle to the attempt to curb migratory flows, increasingly predicated upon Tripoli’s forces maritime interdiction operations.

5. Externalisation Redux: the 2017 MoU, the disengagement of EU missions, and the criminalisation of NGOs

2017 marked the turning point in the EU’s relapse to externalisation, which occurred even if the legal and humanitarian externalities of this approach were known to EU policy makers (authors’ interviews 2016, 2017; Cusumano Citation2019; Riddervold Citation2018). The attempt to offload migration controls on Libyan authority was buttressed by four interrelated developments: the agreement between Italy’s and Libya’s GNA and militias, EUropean security forces’ disengagement from the Mediterranean and increasing focus on capacity building for the LCGN, and the criminalisation of NGOs, stigmatised as a pull factor of irregular migration. This section examines each of these trends in detail.

In January 2017, Marco Minniti – Italy’s Democratic Party politician serving as interior minister in the Gentiloni cabinet – visited Tripoli to sign an agreement with the GNA president Fayez al Sarraj. Italian foreign policy towards Libya can be characterised by de facto bipartisanship and substantial continuity over time (Strazzari and Grandi Citation2019; Caponio and Cappiali Citation2018). The agreement signed in 2017 is a case in point. By Minniti’s own admission, the text of the MoU was ‘grafted onto the TFFP’, incorporating and expanding the commitments already made by the two parties in the 2008 TFPC (Zandonini Citation2021; Giuffré Citation2020; Liguori Citation2019).

Both the 2017 MoU and the 2008 TFPC cover various subjects, including anti-terrorism cooperation, Libya’s stabilisation and development, and migration governance. Tripoli authorities’ support in curbing irregular migration, however, features very prominently in both. Like the 2008 TFPC, where Italy committed to building infrastructure and providing aid for 500 million dollars, the 2017 MoU ties Tripoli’s authorities’ support in curbing irregular migration to Rome’s financial aid and technical support. As already stated in the first article of the MoU, Italy pledged to deliver development aid to infrastructures and renewable energy production to provide Libya’s local communities with economic alternatives to human smuggling. As funding has been directed to the same tribe leaders who previously engaged in the smuggling business, critics have stigmatised this approach as an attempt to co-opt criminals and militias into detaining migrants (Zandonini Citation2021; Maccanico Citation2020, Schatz and Branco Citation2019). Neither the MoU nor any other unclassified documents provide details on the projects supported and the amounts disbursed by Italy. Funding has been provided mainly through the Italian ‘Fondo Africa’ (African Fund), although article 5 of the MoU also mentions ‘making use of available EU funds’ from the EU Trust Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF) (Loschi and Russo Citation2020; Zandonini Citation2021, Spikjerboer and Steyger Citation2019).

Moreover, technical support to Libyan authorities’ patrolling activities is also envisaged. Here, the MoU is slightly more specific, mentioning boats and border control technologies like the same satellite detection system to monitor Libya’s Southern borders already foreseen in Art. 19 of the TFPC. Italy has also pledged to funding migrant reception centres, equipping them with medical equipment and supporting repatriation programmes. Article 5 of the MoU commits the parties to interpreting the agreement in light of international law and human rights obligations. Like the 2008 TFPC, however, the 2017 MoU appears very problematic from a human rights standpoint due to its failure to distinguish between economic migrants and refugees (Giuffré Citation2020; Liguori Citation2019). Although the MoU does not specify what Tripoli’s authorities are to do with migrants, its reference to the patrolling of Libyan waters and reception centres suggests that all, including asylym seekers, are to be interdicted, forcibly returned and detained until their repatriation (Loschi and Russo Citation2020; Palm Citation2020). As Libya is not a signatory to the 1953 Refugee Convention and does not provide any opportunities to apply for asylum, refugees are therefore deprived of the right to obtain international protection (Giuffré Citation2020; Liguori Citation2019; Moreno-Lax Citation2018). Although human rights organisations have vocally denounced the incompatibility between the TFPC and the refugee protection regime, the same arrangements have been uncritically replicated in the 2017 MoU. As of June 2021, this failing has not yet been redressed despite Italian government’s commitment to revise the MoU with a view to better protecting migrants’ rights (Zandonini Citation2021; Maccanico Citation2020). The agreements negotiated in the 2000s and the 2017 MoU are similar not only in their content, but only in terms of negotiating procedure and institutional actors involved. In both cases, a pivotal role was played by Rome’s Ministry of Interior rather than Foreign Affairs, an institutional configuration that helps explain the tendency to frame irregular migration as a crime and pay insufficient attention to Italy’s international obligations under the refugee protection regime.

While no less problematic from a human rights standpoint, the MoU proved even more effective than the 2008 TFPC in curbing departures from Libya. As shown in , seaborne migration across the Central Mediterranean plummeted after July 2017, when the MoU entered into force. In 2020, Malta too drafted a MoU with Tripoli’s forces, signed in July by Valletta’s Prime Minister Abela and then GNA president Al Serraj. This agreement closely mirrors the MoU previously signed by Italy, committing the two parties to cooperating against illegal immigration. To that end, Valletta commits to providing ‘all necessary technology for border control and protection as well as in the dismantling and following up of human trafficking networks, and curtailing the operations of organized crime.’ Moreover, Malta pledged to increase EU finding for Tripoli’s security forces and commits to providing all necessary interception assets ‘in cooperation with the European Union’ (Statewatch Citation2020). Like its 2017 predecessor signed by Italy, the 2020 MoU between Valletta and Tripoli acknowledges that the agreement ‘shall not contravene with obligations under other legal conventions signed by either party’, but does not mention migrants’ fundamental rights or foresees any possibility to obtain protection (Statewatch Citation2020; Mainwaring and De Bono Citation2020). The way these MoUs were negotiated and the vagueness of their content make the MoU a textbook example of the importance of ‘informal informality’ in migration governance (Cardwell and Dickson Citation2023).

While both Italy and Malta’s MoUs extensively focus on maritime interception, the drop in irregular arrivals to Europe occurred since 2017 was mainly the result of militias’ involvement in a policy of onshore containment. In a context of shrinking departures, however, the activities conducted by the LCGN acquired new significance as well. Although interceptions at sea remained stable between 2016 and 2019, the relative significance of these operations increased enormously, and by 2019 over 90 per cent of migrants were intercepted or rescued by the LCGN (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020a). These activities were facilitated by different policies and operational decisions taken at the EUropean level that de facto turned Tripoli’s ships into the largest or sole provider of maritime rescue.

EU institutions have played a direct role in training and equipping Libya’s maritime security forces. The European Council of 22–23 June 2017 pledged that ‘cooperation with countries of origin and transit shall be reinforced’, specifically mentioning that training and equipping the Libyan Coast Guard is ‘a key component of the EU approach and should be speeded up’ (EUTFC Citation2020, 2). Accordingly, operation EUNAVFOR Med ‘Sophia’ completed the training of the first cohort of Libyan officers already in 2016 (Bosilca, Stenberg, Riddervold Citation2020). As anticipated in the 2017 MoU, part of the funding for Libyan security forces directly came from the EU budget, and specifically the EUTF. Like the two other emergency funds (those for Syria and for refugees in Turkey), the EUTF has become an important migration governance instrument, used by the EU to depoliticise irregular migration by reframing it as a technocratic problem requiring the use of development aid to address its root causes (Zaun and Nantermoz Citation2023). As of June 2021, the EU has pumped around €455 million into Libya. At least 60 millions were allocated for ‘Support to Integrated border and migration management in Libya’ (Nielsen Citation2021). Concretely, EU funding would be used to supply new SAR vessels and establishing a mobile Libyan Maritime Rescue Centre (MRCC) under the authority of the Ministry of Communications (EUTF Citation2020, 4–5). This newly-formed MRCC was initially hosted aboard an Italian Navy ship docked in the port of Tripoli. Rome also provided six speedboats, surveillance equipment, prompting a situation where ‘Italian funds support and integrate with programs by the European Union and other member states’ (Zandonini Citation2021; Maccanico Citation2020).

As the training of the LCGN developed, European missions reduced their presence at sea, disengaging from the Southern Mediterranean. As acknowledged in a confidential EUNAVFOR MED document leaked in August 2019, since mid-2017 EU forces would ‘gradually assume a “second line” posture’ to ‘force the LCGN to become the prime actor and progressively take full ownership of their area of responsibility’ (EEAS Citation2019, 4). By 2017, EUNAVFOR Med assets and personnel reduced their involvement in SAR operations, shifting their focus towards activities that are more in line with CSDP missions’ traditional mandates, including the enforcement of the UN arms embargo on Libya and capacity-building for the LCGN. Despite being loaded with new tasks, EUNAVFOR MED saw its direct presence at sea decreased to only two ships. In 2018, after failing to convince other countries to serve as place of disembarkation for the migrants rescued by EU assets, the Italian government withdrew its support for the operation, which remained formally active but was reduced to air surveillance and capacity building. In March 2021, ‘Sophia’ was replaced by EUNAFVOR Med ‘Irini’. The new mission has an exclusive focus on the implementation of the UN arms embargo on Libya, the training of the LCGN, and the disruption of human smuggling networks through information gathering and air patrolling. As stressed by the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Borrell, ‘I want to put all the importance to the fact that this is not [Operation] Sophia bis. It is a completely different operation … the mission is not devoted to look for people and to rescue them’ (EEAS Citation2020). In February 2018, Frontex operation Triton was also scaled down and replaced by Themis, a mission with ‘enhanced law enforcement focus while continuing to include search and rescue as a crucial component’. Themis had a larger scope than its predecessor, covering drugs and weapons smuggling as well as illegal fishing, and a wider operational area, covering illicit maritime activities from Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Turkey and Albania. Neither Frontex nor EUNAVFOR assets have reportedly conducted any rescue operations since 2018. This disengagement of EU assets from the Southern Mediterranean epitomises EU’s relapse to its pre-2013 approach to maritime border monitoring, characterised by little to no direct involvement in SAR off the coat of Libya.

As mentioned in the previous section, NGOs’ presence started shrinking in 2017, in parallel with the growing role played by the LCGN. From 2017 on, however, non-governmental SAR has been considered at cross-purposes with the interdiction of migrants by Libyan forces and restricted accordingly. Since then, some Italian politicians and attorneys have explicitly criminalised non-governmental sea rescuers, which have even been accused of operating in collusion with human smugglers. While no humanitarian worker to date has been sentenced, investigations by courts and inspections by port authorities caused many ships to be impounded for several months and deterred several NGOs from continuing SAR operations. This criminalisation process culminated in 2018, when Italy’s then Interior Minister Salvini declared Italian ports closed to foreign-flagged vessels carrying migrants and imposed heavy fines on those entering Italian waters (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020b; Strazzari and Grandi Citation2019). While this policy was later discontinued, the fact that information on boats in distress is no longer shared with NGO ships, which have continued to be impounded on administrative grounds for the alleged violation of maritime safety and environmental standards, has severely hindered non-governmental sea rescue (Cuttitta Citation2020). Maltese authorities have restrained NGOs’ activities as well, authorising disembarkation only in very sporadic occasions and impounding the rescue ship Lifeline in 2018 (Mainwaring and De Bono Citation2020). Owing to these restrictions, as illustrated by , NGOs rescued less than 2,000 migrants in total between 2019 and 2020 (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020b).

Although criticised at times by EU bodies like the Fundamental Rights Agency and Parliament, the policing of NGOs was endorsed in various occasion by the Council and the Commission, which supported the restrictions on non-governmental sea rescue envisaged in a 2017 Italian Code of Conduct (Rettman Citation2017). An especially prominent role in questioning NGOs’ work has been played by Frontex. During an interview in December 2016, Frontex director criticised NGOs for serving as a pull factor of irregular migration. This concern was also mentioned in Frontex’s 2017 and 2020 Risk Analysis as well as several European leaders’ meetings like the September 2019 Valletta summit (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020b; Frontex Citation2020; Frontex Citation2016).

6. Failing through and Europe’s relapse to externalisation: an analysis

EUrope’s approach to irregular migration across the Central Mediterranean has backslidden into a restrictive border control regime predicated upon externalisation. This strategy has been buttressed by four interrelated policies and processes: the 2017 MoU between Italy and Libya, followed by the 2020 Malta-Libya MoU; the funding and training of Tripoli’s security forces; the disengagement of European naval assets from the conduct of SAR in the Southern Mediterranean; and the criminalisation of NGOs. The mechanism of failing through provides important insight into each of these processes, shedding new light on the EU’s relapse to externalisation.

First, the 2017 MoU between Italy and Libya displays striking similarities with the 2008 TFPC, which – by Italian authorities’ own admission, served as a template for the new agreement. Like previous agreements with Gaddafi’s Libya, the MoU was negotiated by the Minister of Interior rather than Foreign Affairs, is predicated upon the offer of both financial incentives and technical assistance, and fails to distinguish between economic migrants and refugees, using the overarching derogatory label of ‘illegal immigration’. The bilateral agreements reached by Spain with Morocco, Mauritania and Senegal, explicitly presented by Madrid as the outcome of ‘a European management model, reproducible in other contexts’, have arguably served as a template as well. Like the externalisation of migration management to Libya, these agreements were built around the creation of new border patrol forces through a combination of Spanish and EU funding and training, as well as direct and indirect support for containing migrants in detention centres (Zandonini Citation2021). To a lesser extent, the MoU is also built on the example of the March 2016 EU-Turkey deal, uncritically reapplied to the Libyan context despite the GNA’s chronic fragility and their inability or unwillingness to provide asylum seekers with access to international protection. For this reason, scholars have referred to the 2017 Italy-Libya Memorandum as a ‘poor replication’ of the EU-Turkey deal (Palm Citation2020: 2). Several aspects of the 2017 MoU, in turn, were mirrored by the 2020 agreements between Libya and Malta, which also committed to funding Tripoli’s security forces to combat ‘illegal immigration’ and ‘human trafficking’. Unlike the EU-Turkey deal, the two MoUs examined here were instances of bilateral cooperation between Rome, Valletta, and Tripoli. However, both agreements refer to the support of the EU at large, which is explicitly mentioned as the source of part of the funding. Both funding for and direct training to the LCGN have indeed been directly provided by the EU through the EUTF and operation EUNAVFOR Med. Together, Italy, Malta, and the EU have engaged in the ‘reinvention of the Libyan Coast Guard’ (Schatz and Branco Citation2019, 211).

By allowing us to capture both continuity and change in EU migration policies, the concept of failing through we proposed in this article is particularly helpful for understanding this process. Elements of failing forward can be found in how Europe initially dealt with the upsurge of irregular migration from Libya, when new policies were introduced. At the same time, however, path dependency can be found in how the EU has organised its broader, long-term migration policies. An example is the mandate, structure and operational behaviour of EUNAVFOR Med and the other EU maritime missions. As noted by Bosilca, Stenberg, and Riddervold (Citation2020), operation EUNAVFOR Med has built heavily on the model provided by the only other EU maritime mission that preceded it – anti-piracy operation EUNAVFOR Atalanta. Over the years, EUNAVFOR Med has gradually relinquished SAR operations to concentrate on EU military missions’ most typical activities, such as capacity-building and enforcing arms embargoes. The rebranding of the mission from Sophia – a baby born on an EU frigate after a rescue operation – to Irini – Greek word for peace – clearly epitomises this shift. A tendency to rely on pre-established institutional frameworks and standard operating procedures has also characterised Frontex border control missions. Various scholars have considered the functioning of Frontex today and the agency’s focus on curbing irregular mobility as depending on the conditions under which it was set up (Perkowski Citation2019). The missions in the Mediterranean are a case in point. The enhancement of Frontex operational presence in the Mediterranean occurred in April 2014, when Triton’s assets and the size of its operational area were tripled, was short-lived and stymied by a strong institutional resistance to engage in proactive SAR, seen as a pull factor of migration. By 2018, Triton had been replaced by Themis, whose mandate resembles traditional border control missions and whose limited resources and large operational area minimised the involvement of Frontex assets in migrant rescue missions (Cuttitta Citation2020; Cusumano Citation2019).

The decision to criminalise those assisting migrants at sea is also far from new, but appears to be a relapse to Italian and Maltese courts’ long-standing tendency to investigate civilian ships conducting SAR, facilitated by Frontex and internal security experts’ tendency to problematise sea rescue as facilitating illegal immigration. While the number of non-governmental SAR missions occurred between 2015 and 2017 was unprecedented, attempts to criminalise NGOs’ involvement in SAR in the Southern Mediterranean date back to at least 2005, when the indictment of the German organisation Cap Anamur for prosecuted for aiding and abetting illegal immigration. Already then, the risk of indictment served as a deterrent to engage in rescue operations (Basaran Citation2015).

This relapse to externalisation can be explained by the mechanisms of path dependency that have been widely documented by historical institutionalist scholarship. When facing situations framed as crises, decision-makers are especially likely to copy previous solutions, even if those solutions are not suitable or appropriate for the new problems at hand. Italy and Malta’s framing of irregular migration as an internal security problem to be dealt with by law enforcement agencies, as well as their attempts to replicate with Tripoli’s GNA the same type of cooperation enshrined by the EU-Turkey Deal and the 2008 MoU with Gaddafi’s Libya, are a case in point. Institutional stickiness and path-dependent behaviour prompted both national European leaders and EU officials to relapse to previous institutional frameworks predicated on the externalisation of migration governance despite mounting evidence of its problematic consequences.

7. Conclusions

By suggesting that the EU has failed through in its migration governance across the Mediterranean, our findings have important implications for the scholarship and policy debates on migration governance, historical institutionalism, and European integration.

Scholars have long criticised European decision-makers’ persisting willingness to pursue models of mobility management predicated upon very restrictive border policies despite widespread evidence that these policies fail to deliver the expected results, thereby creating an ‘implementation gap’ (Caponio and Cappiali Citation2018). In the case of the Central Mediterranean in particular, a wealth of studies have demonstrated the incompatibility between the 2017 MoU and the refugee protection regime (Giuffré Citation2020; Palm Citation2020; Moreno-Lax Citation2018), the humanitarian externalities and negligible effects of EUropean decision-makers’ crusade against human smugglers (Perkowski and Squire Citation2019; McMahon and Sigona Citation2018) and the lack of any correlation between NGOs’ sea rescue operations and the size of irregular migratory flows (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020a). Institutional stickiness and path dependency help explain decision-makers’ resistance to depart from established policy paradigms even if those are often predicated upon ‘pseudocausal narratives’ unsupported by existing evidence (Zaun and Nantermoz Citation2020).

The trajectory of migration governance across the Central Mediterranean also has implications for institutionalist EU scholarship. Previous studies have conceptualised the 2015 Lampedusa shipwreck as a critical juncture in EU policy (Bosilca, Stenberg, and Riddervold Citation2020). In our study too, we have noted that widely publicised tragedies at sea, in combination with the ECtHR Hirsi decision and the collapse of Gaddafi’s regime, have disrupted EU irregular migration governance. The relapse to externalisation that occurred after 2017, however, suggests that entrenched policy frameworks like EUrope’s restrictive border regime have been resilient to external shocks, and tend to be restored without major changes. Consequently, even shocks that look like critical junctures may only temporarily disrupt existing policy paradigms. Future research should investigate more in-depth what the factors underlying the resilience of existing policy paradigms are in order to gauge their ability to absorb different types of external shocks like ECHR decisions and humanitarian crises unfolding at EU borders.

A November 2017 confrontation between the LCGN and the NGO Sea-Watch which resulted in the death of several migrants and the return of many asylum seekers to Libya was brought to the ECtHR, which will have to assess whether Italy can be held responsible for these fundamental rights violations (Maccanico Citation2020). A request to investigate the EU for war crimes was also filed to the International Criminal Court (Schatz and Branco Citation2019). In the meantime, the ongoing civil war in Libya and the fragility of the GNA continues to cast doubts over Tripoli’s ability to consistently curb departures to Europe in the aftermath of the covid-19 pandemic. While our findings suggest that externalisation is set to remain the dominant paradigm of EU migration management, additional research should assess how and to what extent institutional stickiness and path dependency will continue to characterise EUrope’s irregular migration governance. For instance, future scholarship may assess whether criticism of Frontex due its involvement in push-back operations in the Aegean Sea will lead to any meaningful reform of the European border agency. Future research should also place the Central Mediterranean in a more explicit comparative perspective, expanding the analysis to other migratory routes to Europe and other regions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ansell, C. 2021. “Institutionalism.” In The Palgrave Handbook of EU Crises, edited by M. Riddervold, J. Trondal, and A. Newsome, 135–152. Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Baldwin-Edwards, M., and D. Lutterbeck. 2019. “Coping with the Libyan Migration Crisis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (12): 2241–2257.

- Basaran, T. 2015. “The Saved and the Drowned: Governing Indifference in the Name of Security.” Security Dialogue 46 (3): 205–20.

- Beach, D., and R. B. Pedersen. 2013. Process-Tracing Methods. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Bergmann, J., and P. Müller. 2023. “Spillover Dynamics and Inter-Institutional Interactions Between CSDP and AFSJ: Moving Towards a More Joined-up EU External Migration Policy?.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (12): 3005–3023. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2193712.

- Bialasiewicz, L. 2012. “Off-shoring and Out-sourcing the Borders of EUrope: Libya and EU Border Work in the Mediterranean.” Geopolitics 17 (4): 843–866.

- Bosilca, R., M. Stenberg, and M. Riddervold. 2020. “Copying in EU Security and Defence Policies: The Case of EUNAVFOR MED Operation Sophia.” European Security, DOI: 10.1080/09662839.2020.1845657.

- Capoccia, G., and R. D. Kelemen. 2007. “The Study of Critical Junctures: Theory, Narrative, and Counterfactuals in Historical Institutionalism.” World Politics 59 (3): 341–369.

- Caponio, T., and C. Cappiali. 2018. “Italian Migration Policies in Times of Crisis: The Policy Gap Reconsidered.” South European Politics and Society 23 (1): 115–132.

- Cardwell, P. W., and R. Dickson. 2023. “‘Formal Informality’ in EU External Migration Governance: the Case of Mobility Partnerships.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (12): 3121–3139. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2193743.

- Cusumano, E. 2019. “Migrant Rescue as Organized Hypocrisy: EU Maritime Missions Offshore Libya Between Humanitarianism and Border Control.” Cooperation and Conflict 54 (1): 3–24.

- Cusumano, E., and M. Villa. 2020a. “Over Troubled Waters. Maritime Rescue Operations in the Central Mediterranean.” In Migration in the Central Mediterranean Route and Beyond: Safety, Support and Solutions, edited by R. International Organization for Migration. Geneva: IOM.

- Cusumano, E., and M. Villa. 2020b. “From “Angels” to “Vice Smugglers”: the Criminalization of Sea Rescue NGOs in Italy.” European Journal of Criminal Policy and Research, doi:10.1007/s10610-020-09464-1.

- Cuttitta, P. 2020. “Search and rescue at sea, non-governmental organisations and the principles of the EUs external action.” In 20 years Anniversary of the Tampere Programme: Europeanisation Dynamics of the EU Area of Freedom, Security and Justice, edited by S. Carrera, D. Curtin, and A. Geddes, 123–144. Florence: EUI.

- Czaika, M., M. B. Erdal, Talleraas, C. 2023. “Exploring Europe’s External Migration Policy Mix: On the Interactions of Visa, Readmission, and Resettlement Policies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (12): 3140–3161. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2198363.

- EEAS – European External Action Service. 2019. EUNAVFOR Med Op Sophia – Six Monthly Report 1 DEC 2018 - 31 MAY 2019. https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/6294327/EUNAVFOR-MED-Op-SOPHIA-Six-Monthly-Report.pdf.

- EEAS – European External Action Service. 2020. Operation IRINI: Remarks by High Representative/Vice-President Joseph Borrell following the launch of the operation. https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/76832/operation-irini-remarks-high-representativevice-president-josep-borrell-following-launch_en.

- EUTF – EU Trust Fund for Africa. 2020. Action Document. The Emergency Trust Fund for Stability and Addressing the Root Causes of Irregular Migration and Displaced Persons in Africa. https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/sites/euetfa/files/t05-eutf-noa-ly-07.pdf.

- Fargues, P. 2017. Four Decades of Cross-Mediterranean Undocumented Migration to Europe. A Review of the Evidence. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

- Frontex. 2011. Hermes 2011 Running. https://frontex.europa.eu/media-centre/news/news-release/hermes-2011-running-T7bJgL.

- Frontex. 2016. Risk analysis for 2017. https://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Annual_Risk_Analysis_2017.pdf.

- Frontex. 2020. Risk analysis for 2020. https://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Risk_Analysis/Annual_Risk_Analysis_2020.pdf.

- Giuffré, M. 2020. The Readmission of Asylum Seekers under International Law. Oxford: Hart.

- House of Lords. 2016. Operation Sophia, the EU’s naval mission in the Mediterranean: an impossible challenge. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201516/ldselect/ldeucom/144/14406.html.

- International Organization for Migration. undated. Missing Migrants Project. https://missingmigrants.iom.int/.

- Jones, E., R. D. Kelemen, and S. Meunier. 2016. “Failing Forward? The Euro Crisis and the Incomplete Nature of European Integration.” Comparative Political Studies 49 (7): 1010–1034.

- Juncos, A., and K. Pomorska. 2021. “The EU’s Response to the Ukraine Crisis.” In The Palgrave Handbook of EU Crises, edited by M. Riddervold, J. Trondal, and A. Newsome, 553–568. Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Liguori, A. 2019. Migration Law and the Externalization of Border Controls: European State Responsibility. London: Routledge.

- Loschi, C., and A. Russo. 2020. Whose Enemy at the Gates? Border Management in the Context of EU Crisis Response in Libya and Ukraine.” Geopolitics, DOI: 10.1080/14650045.2020.1716739.

- Maccanico, Y. 2020. Anti-migration cooperation between the EU, Italy and Libya: some truths. Statewatch. https://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/analyses/no-356-some-truths-about-libya.pdf.

- Mainwaring, Ċ, and D. De Bono. 2020. “Criminalizing Solidarity: Search and Rescue in a Neo-Colonial Sea.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, doi: 10.1177/2399654420979314.

- Manners, I. 2002. “Normative Power: A Contradiction in Terms.” Journal of Common Market Studies 40 (2): 235–258.

- McMahon, S., and N. Sigona. 2018. “Navigating the Central Mediterranean in a Time of ‘Crisis’: Disentangling Migration Governance and Migrant Journeys.” Sociology, doi: 10.1177/0038038518762082.

- Moreno-Lax, V. 2018. “The EU Humanitarian Border and the Securitization of Human Rights: The “Rescue-through-Interdiction/Rescue without Protection” Paradigm’.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1): 119–140.

- Muller, P., and P. Slominski. 2020. “Breaking the Legal Link but Not the Law? The Externalization of EU Migration Control Through Orchestration in the Central Mediterranean.” Journal of European Public Policy, doi: 10.1080/13501763.2020.1751243.

- Nielsen, N. 2021. Libyan detention centres must end, EU says. EUobserver. https://euobserver.com/migration/152215.

- Niemann, A., and N. Zaun. 2023. “EU External Migration Policy and EU Migration Governance: Introduction.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (12): 2965–2985. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2193710.

- Palm, A. 2020. The Italy-Libya Memorandum of Understanding: The baseline of a policy approach aimed at closing all doors to Europe. Italian Institute of International Affairs. https://www.iai.it/it/pubblicazioni/italy-libya-memorandum-understanding-baseline-policy-approach-aimed-closing-all-doors.

- Panebianco, S. 2021. “The EU and Migration in the Mediterranean: EU borders’ Control by Proxy.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (6): 1398–1416. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1851468.

- Paoletti, E., and S. Pastore. 2010. Sharing the dirty job on the southern front? Italian–Libyan relations on migration and their impact on the European Union. International Migration Institute Paper 29.

- Perkowksy, N. 2019. “There Are Voices in Every Direction’: Organizational Decoupling in Frontex.” Journal of Common Market Studies, doi:10.1111/jcms.12897.

- Perkowski, N., and V. Squire. 2019. “The Anti-Policy of European Anti-Smuggling as a Site of Contestation in the Mediterranean Migration ‘Crisis’.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (12): 2167–2184.

- Pierson, P. 2000. “The Limits of Design: Explaining Institutional Origins and Change.” Governance 13: 475–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00142.

- Pijnenburg, A. 2020. “From Italian Pushbacks to Libyan Pullbacks: Is Hirsi 2.0 in the Making in Strasbourg?” European Journal of Migration and Law 20 (4): 396–426.

- Rettman, A. 2017. EU backs Italy on NGO rescues. EU Observer. https://euobserver.com/migration/138540.

- Riddervold, M. 2018. “A Humanitarian Mission in Line with Human Rights? Assessing Sophia, the EU’s Naval Response to the Migration Crisis.” European security 27 (2): 158–174.

- Riddervold, M., J. Trondal, A. Newsome, eds. 2021. “European Union Crisis. An Introduction.” In The Palgrave Handbook of EU Crises, 3–47. Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Schatz, O., and J. Branco. 2019. Communication to the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court Pursuant to the Article 15 of the Rome Statute.

- Scipioni, M. 2018. “Failing Forward in EU Migration Policy? EU Integration after the 2015 Asylum and Migration Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (9): 1357–1375.

- Servent, Ripoll A., and F. Trauner. 2014. “Do Supranational EU Institutions Make a Difference? EU Asylum Law Before and After ‘Communitarization’.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (8): 1142–1162. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2014.906905.

- Spikjerboer, T., and E. Steyger. 2019. “European External Migration Funds and Public Procurement Law.” European Papers 4 (2): 493–521.

- Statewatch. 2020. Memorandum of Understanding Between the Government of National Accord of the State of Libya and The Government of The Republic of Malta in the Field of Combatting Illegal Immigration. https://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/news/2020/jun/malta-libya-mou-immigration.pdf.

- Stierl, M. 2018. “A Fleet of Mediterranean Border Humanitarians.” Antipode 50 (3): 704–724.

- Strazzari, F., and M. Grandi. 2019. “Government Policy and the Migrant Crisis in the Mediterranean and African Arenas.” Contemporary Italian Politics 11 (3): 336–354. doi: 10.1080/23248823.2019.1644833.

- Stutz, P. 2023. “Political Opportunities, not Migration Flows: Why the EU Cooperates more Broadly on Migration with some Neighbouring States.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (12): 3101–3120. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2193716.

- Tazzioli, M., and N. De Genova. 2020. “Kidnapping Migrants as a Tactic of Border Enforcement.” EPD: Society and Space, doi 10.1177/0263775820925492.

- UN - United Nations Mission to Libya. 2018. Desperate and Dangerous: Report on the human rights situation of migrants and refugees in Libya. https://unsmil.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/libya-migration-report-18dec2018.pdf.

- Verdun, A. 2015. “A Historical Institutionalist Explanation of the EU’s Responses to the Euro Area Financial Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 22 (2): 219–237.

- Zandonini, G. 2021. The Big Wall. ActionAid, https://thebigwall.org/en/?fbclid=IwAR06S_VRwhTqbyNqF3CwkG98ETvDQsuSXYukB40kjwYR4YhtWG5n_Zdljzg.

- Zaun, N., and O. Nantermoz. 2020. “The use of Pseudo-Causal Narratives in EU Policies: The Case of the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa.” Journal of European Public Policy, doi: 10.1080/13501763.2021.1881583.

- Zaun, N., and O. Nantermoz. 2023. “Depoliticising EU Migration Policies: the EUTF Africa and the politicisation of Development Aid.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (12): 2986–3004. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2193711.