ABSTRACT

Why is the EU cooperating more on migration issues with some third countries than others? What explains this variation? In recent years, the EU has intensified its institutionalised cooperation with third countries in the area of migration, although to different degrees. The extent of migration cooperation is measured in this article by conducting a fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. It looks at the conditions that have triggered more or less cooperation in 23 countries of the Eastern and Southern EU neighbourhood up to 2015, a key moment in the external relations. Theoretically, the article draws on five factors to explain the different levels of cooperation: (1) migration flows; (2) the state of democracy in the partner country; (3) existing relations with the EU; (4) economic dependence of the partner country on the EU; (5) administrative capacities of the partner country. The article advances the argument that a third country’s existing relations with the EU or the state of democracy in combination with a high level of economic dependence on the EU are the key factors for understanding why some third countries cooperate more. The number of migrants originating from or transiting through a third country is only of secondary importance.

Introduction

Migration cooperation with third countries has become a key priority of the European Union (EU), notably since the ‘migration crisis’Footnote1 of 2015 and 2016. This is not to say that migration cooperation is a new phenomenon. Communitarised since the Treaty of Amsterdam, migration policy has been an element of EU foreign policy since 1999 (Niemann Citation2008). The EU has sought to intensify relations and cooperation with many third countries and to develop a comprehensive external migration policy (European Commission Citation2011a, 2; see also: Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015; Betts Citation2010). It has now a multitude of political, legal and operational instruments and tools at its disposal, especially with the neighbouring countries of the EU (Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015; for a detailed account on the evolution of these tools, see Niemann and Zaun Citation2023). Examples are EU readmission agreements, visa facilitation agreements, Frontex working arrangements, or legal migration clauses in association agreements. This article considers these instruments as the basis for cooperation given that they are instances of formalised cooperation between the EU and the third country.

However, the EU applies the agreements and tools of cooperation with neighbouring countries diversely. The article comparatively elaborates on the factors that may determine the cooperation of neighbouring states with the EU in the field of migration. This lens will contribute to our understanding of the variance of cooperation. Previous studies have already explained the diverse migration tools that the EU employs in its external relations (e.g. Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015), or their exact geographical use (Carrera, Radescu, and Reslow Citation2015), yet a more analytical analysis on the factors leading to cooperation, notably from a larger-N perspective, is still missing.

The EU has a minimum level of cooperation with almost all countries in the world (Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015; cf. Betts Citation2010). However, the degree of cooperation is different both between regions but also between countries from the same region, especially in the area of migration (Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015; Lavenex and Uçarer Citation2004; Weinar Citation2011). Looking at this variance, the article investigates which conditions explain broad EU migration cooperation with third countries in the EU neighbourhood.Footnote2

This question is of relevance as ‘(…) enhanced cooperation with countries of origin, transit and destination with a well-managed migration and mobility policy (…)’ was considered the basis to respond to the ‘crises’ that emerged around migration (European Commission Citation2016, 2). This policy is touching all areas of migration cooperation. Against the backdrop of increased migration cooperation even before these ‘crises’ and the failure of the EU Agenda on Migration (Scipioni Citation2018), the variance in cooperation scope is puzzling. It is unclear whether the EU approach is either too diverse and/or not inclusive enough when cooperating with third countries. On the one hand, the EU may pursue its interests more unilaterally and without taking into account the interests of the cooperation partners. This can, for instance, be seen with regard to the EU’s readmission policy and the importance of migration management in the EU Trust Fund for Africa (e.g. Adepoju, van Noorloos, and Zoomers Citation2010; Oxfam Citation2020). On the other hand, the EU approach can differ much between countries and regions as some incentives that the EU is willing to offer to some third countries are not available to others; this refers, e.g. to visa liberalisation (European Commission Citation2011b). These determinants for the EU’s cooperation approach can create the basis for the variance under investigation.

Cooperation is understood as a process of policy coordination between actors to realise their objectives. The scope or extensity of cooperation is measured by the amount of different migration policy instruments between the EU and a third country. The article conducts a fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) with 24 accession and EU neighbouring countries in 2015 to identify necessary and sufficient conditions for extensive migration cooperation. By looking at cooperation until 2015 the article elucidates this watershed moment of EU migration policy – a cooperation which has increased for years up unto that point, only to result in the ‘migration crisis’ of 2015/2016.

The article proceeds by discussing the literature and explaining the concept of cooperation extensity. The method, data, operationalisation and research design prepare the ground for the fsQCA analysis. It is argued that the existing relations with the EU are key for understanding the level of cooperation. More democratic and at the same time economically dependent states are more likely to engage as well. These results highlight that the EU’s cooperation efforts are targeted towards a particular set of countries, namely those with which the EU has close ties or over which it has strong leverage. Also, broad cooperation with countries where migration pressure is high, seems to be harder to achieve.

Migration policy tools: why they are applied differently

The questions of why and how actors cooperate has been of interest for many scholars. I follow Keohane’s (Citation1984, 51f.) definition of cooperation. ‘Cooperation takes place when the policies actually followed by one government are regarded by its partners as facilitating realisation of their own objectives, as the result of a process of policy coordination’. One actor’s policies are regarded as obstructive to the policies of another actor and, consequently, there are attempts between the actors to adjust their policies, so that policies between actors become compatible and ‘adverse consequences (…) are avoided, reduced, or counterbalanced or overweighed’ (Lindblom Citation1965, 227). Keohane also highlights the importance of different issue areas in which states act to make cooperation possible (Keohane Citation1984, 60f.). In a similar vein, Sandra Lavenex (Citation2011) contends that cooperation can differ in scope to allow for policy coordination on different issues. Hence, the extensity or the scope of cooperation make a difference and are depending on contextual and environmental factors. The EU tries to cooperate broadly with the expectation to influence the policy of third countries as much as possible. Cooperation on a wider range of migration issues is in the EU’s interest: A fair and balanced cooperation on eye level is regarded beneficial for both partners (Collett and Ahad Citation2017; European Commission Citation2011a).

This article focuses on the extensity of the migration cooperation understood in terms of numbers of issue areas covered and forms of institutionalised cooperation (the QCA outcome is also named ‘SCOPE’ in the analysis). The broader and more institutionalised a cooperation is, the more intense it can be regarded. QCA can examine each aspect of the cooperation and each EU-third country instrument. The analysis of the cooperation tools can help us understanding cooperation and what induces it (Trauner and Wolff Citation2014), and the areas of the EU’s external migration cooperation are well-established (cf. Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015; cf. Carrera, Radescu, and Reslow Citation2015). The EU defines them as the reduction of irregular migration; borders and prevention of irregular migration; visas; legal migration and work-related migration; and administrative and financial aspects (European Commission Citation2011a, Citation2013, Citation2015). Each of these categories rely on specific instruments such as readmission agreements; Frontex working arrangements; visa facilitation agreements and waivers; Mobility Partnerships and clauses in Association and Partnership Agreements; Regional (Development and) Partnership Programmes; commitments in European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) Action Plans; EASO support; and financial programmes that have been set up as reaction to the ‘migration crisis’ in 2015. This article has carefully examined in each of the chosen cases whether and how many of these instruments have been agreed upon and the number of issue areas covered by these instruments constitutes the outcome.

Why cooperate on migration

This section looks at explanations in the literature as to why third countries cooperate with the EU. There is a vast body of literature that focuses on the European neighbourhood looking into how policy change comes about and how it is induced (e.g. Börzel and Risse Citation2012; Kelley Citation2006). This serves as basis for the theoretical framework as cooperation can be considered as an instance of policy change (cf. Guérin Citation2018). Broad migration cooperation comes along with changes in the third country and alters the relationship between the EU and third countries – which explains the focus on macro conditions.

The EU’s cooperation on migration is considered to be rational and interest-driven (Boswell Citation2003). Therefore, the EU can be expected to seek more cooperation, unless some other considerations interfere (e.g. prohibitive high costs or a desire not to cooperate with autocracies). The premise is that migration cooperation both explicitly and implicitly serves as a means to control irregular migration to the EU, and thus focuses on ‘remote control’ (see introduction to this special issue). Building upon existing knowledge, this article suggests that the extensity of the EU’s cooperation with third countries depends on five conditions: (1) the flow of migration between the EU and a third country; (2) the administrative capacities of the third country; (3) its political relations with the EU; (4) the state of democracy and (5) the economic dependence on the EU. It is important to note that the focus is not on how the EU initiates the cooperation or negotiates the instruments (see e.g. Carrera, den Hertog, and Parkin Citation2012; Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015, 18ff.; Trauner and Wolff Citation2014; Reslow and Vink Citation2015 in this regard). Through QCA, this article looks at the conditions under which the cooperation actually takes place.

Regarding the identification of theoretical expectations for the QCA analysis, I draw in particular from external Europeanisation literature as well as from studies on the externalisation of EU migration policy. Schimmelfennig (Citation2015, 7f.,) suggests that the ways in which the EU may exercise influence over third countries primarily relate to the logics of consequences and appropriateness. From this follows that third countries either cooperate because it maximises their utility, in other words it is in their benefit to do so as the EU provides incentives for cooperation, or there is a power asymmetry through which non-cooperation with the EU would incur (immaterial or material) costs (cf. Boswell Citation2003). Or, with regard to the logic of appropriateness, third countries are cooperating with the EU on migration issues as it is in line with their social rules and norms, for instance when a third country seeks membership or shares democratic values (Börzel and Risse Citation2012; Schimmelfennig Citation2015, 7).

The influence of conditionality, by which the EU tries to influence cost–benefit calculations of third countries by providing positive and negative incentives, has been a backdrop for many cooperation efforts from the very beginning of the cooperation with ENP countries (Börzel and Risse Citation2012; Lavenex and Uçarer Citation2004; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Citation2004). Aside from conditionality, cooperation can also be induced by socialisation, e.g. through soft diplomacy like persuasion or shaming. It has however become clear that conditionality could not be applied too strictly or without limits as the third country would not comply (Kelley Citation2006). The same holds for socialisation, as both rhetorical and procedural ‘entrapments’ might emerge if the EU is promising membership prospects that will never realise (Sasse Citation2008). These strategies explain how cooperation with third countries occurs. But this should not be considered as unidirectional, as both strategies can strengthen and weaken policy change (cf. Sasse Citation2008). It has further been noted that third countries lacking the membership incentive comply with EU demands for migration cooperation if it fits their preferences to (re-)gain political power. The importance of membership aspirations, in relation to the success of conditionality, has also been discussed (Ademmer and Börzel Citation2013; cf. Langbein and Börzel Citation2013).

According to Lavenex and Schimmelfennig (Citation2009, 805–807), the EU’s external governance in neighbouring countries mainly works in a non-hierarchical way. The adoption and the implementation of the Acquis Communautaire would not be a priority, rather the sectional rapprochement to EU norms and practices (see also Lavenex Citation2004; Lavenex and Uçarer Citation2004). Nonetheless, a selective rule transfer has been identified as not all countries in the neighbourhood have adopted EU rules uniformly or to a similar extent. Especially for ENP countries, this can be attributed to whether a third country deems the ENP useful for their domestic agendas or actively seeks legitimacy from the EU for their policies (Casier Citation2011, 46f.). The ENP, being an ‘undefined political process’, allows for differentiated policies that are influenced by strong links with individual member states and an absence of benchmarks (Casier Citation2011, 48). Investigating migration cooperation traces this selective cooperation and explains the variance in the field. Börzel and Risse (Citation2012, 14) have identified scope conditions that affect domestic change and that can facilitate or prevent policy diffusion when cooperating with third countries: domestic incentives, degrees of statehood, democratic quality and power asymmetries. These scope conditions come into play when identifying the conditions.

These conditions are not to be understood as direct causal mechanisms; rather it is evaluated if conditions are sufficient or necessary to induce an outcome (cf. Mahoney, Kimball, and Koivu Citation2009). Thus, the conditions are identified based on previously discussed (assumed) relationships with (migration) cooperation (e.g. Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015), or established connections through case studies. Yet the added-value of the QCA is to contextualise them with one another, as QCA is in constant ‘dialogue with the case’ (Rihoux and De Meur Citation2009, 48). Its focus on investigating set relations (with ‘conjunctural causation’, see below) allows for greater generalisation and broader understanding, both of the interactions between the conditions and the outcome and of the empirical situation at large. How do the different conditions relate to each other when broad migration cooperation is in place?

Furthermore, these conditions relate to the macro level in the third country and refer to the cooperation relationship between the third country and the EU. In this comparative study, domestic factors are only appreciated if they might pose an influence on the migration cooperation in the five areas. The QCA shows under which constellations they can induce the outcome.

Condition 1: migration flow

The EU is keen to cooperate with countries of migrants’ transit or origin to reduce (predominantly irregular) migration inflows (cf. Council of the EU Citation2002; Lavenex and Uçarer Citation2004; Geddes Citation2005). Migratory pressure has been identified as conducive to migration cooperation (Guérin Citation2018). Additionally, if there are many asylum seekers coming from a third country, the EU may engage particularly to reduce the number of irregular migrants and illegal border crossings due to mixed migration flows (Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015). This can take the form of a particular focus on the ‘root causes of migration’ (EU Commission Citation2015), but might also be considered as maintaining an existing power asymmetry (cf. Börzel and Risse Citation2012). At the same time, the EU may want to adopt a readmission agreement or informal return deal particularly with this kind of countries (Adepoju, van Noorloos, and Zoomers Citation2010; Cassarino Citation2010; Geddes Citation2005). A high migration inflow is hence expected to increase EU cooperation efforts with countries of origin and transit on a broad basis as migration flows are mixed and diverse and broad migration cooperation is addressing these multiple areas.

Condition 2: administrative effectiveness

The cooperation of third countries may also strongly relate to the administrative capacities (Lavenex and Uçarer Citation2004). State capacities can serve as precondition ‘(…) to adopt and adapt to EU demands for domestic institutional change' (Börzel and Risse Citation2012, 11). If administrations are effective and capable, the external cooperation may be more stable and comprehensive (Hille and Knill Citation2006; Lavenex and Uçarer Citation2004; Weinar Citation2011). This implies that a lower level of administrative misfit between EU- und third country-governance might be more conducive to cooperation due to lower adaption costs (Schimmelfennig Citation2015, 22). Intra-state administrative structures and capacities in third countries are closely linked (Wunderlich Citation2012, 1426). An analysis of ENP Action Plans showed that third countries do have influence when cooperating with the EU. If there were reform activities prior to the EU getting involved with the third country or the country showed willingness to reform and cooperate, the design of ENP Action Plans was to a large degree determined by the third country (Guérin and Rittberger Citation2020, 10). This is an important finding as third countries are not only recipients but active actors in the cooperation. Given the benefits of cooperating more broadly on migration issues (rather than, e.g. only cooperating on readmission), higher administrative capacities and more effective administrative structures lead to the expectation of broader migration cooperation as the third country is able to deal with more issues at the same time and develop own interests rather than complying with EU preferences (cf. Guérin and Rittberger Citation2020).

Condition 3: existing relations

Close political relationships between a third country and the EU may foster the migration cooperation (Hamood Citation2008; Lavenex and Schimmelfennig Citation2009; Lavenex and Uçarer Citation2004). This concerns in particular neighbouring states. The status of a candidate country for EU membership has a significant impact on the cooperation (cf. Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015). One reason for this is conditionality (Lavenex and Schimmelfennig Citation2009; Lavenex and Uçarer Citation2004; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Citation2004; Trauner and Kruse Citation2008). Conditionality can also influence existing relations between the EU and a third country – although ‘the EU’s impact is differential across countries and issues’ (Freyburg et al. Citation2009; Sedelmeier Citation2006, 17). Furthermore, conditionality’s impact increases with the existing ties to the EU, having most potential impact with accession candidates (Schimmelfennig Citation2015). In absence of membership aspirations, selective cooperation can still be expected over time if preferences align (Casier Citation2011). Following the logic of appropriateness, countries with closer established ties to the EU are more likely to share mutual values (Börzel and Risse Citation2012). The condition combines EU leverage with institutionalised and close relations which allows for broader migration cooperation.

Condition 4: democracy

‘Democracy’ is understood as the level of democratic credentials that are adhered to by a third country. A broad definition of democracy is applied, based on the methodology of Freedom House, in which both civil liberties and political rights are assessed.Footnote3 This is useful as – even though migration cooperation is not directly connected to all aspects of democracy – this research is driven by the question of how the EU cooperates on the contentious field of migration policy with countries of migrants’ origin that have different levels of democratic credentials. In addition, migration cooperation operates in an area of tension between third countries that do not want to cooperate on migration (esp. on return due to public pressure, see Cham and Adam Citation2021) and legal restraints like the principle of non-refoulement (e.g. Hailbronner Citation1997), and self-proclaimed values, e.g. that the EU favours cooperation with countries that are democratic or at least not autocratic (Freyburg et al. Citation2009; Lavenex and Schimmelfennig Citation2011). This may hold particularly true for the field of asylum and migration, although the EU does cooperate with non-democratic states. Börzel and Risse (Citation2012, 12) contend that the adaption costs for domestic change (here: cooperation) are higher for authoritarian regimes because they hold power over society and economy and having to comply with EU demands threatens this status. However, this cooperation tends to cause fierce public debates. Examples thereof have been the EU readmission agreement recently signed with Belarus (Bosse and Viera Citation2018, 24) or EU border control cooperation with Libya (Müller and Slominski Citation2020).

The condition also relates to democracy promotion, as cooperation with the EU can come on the precondition that democratic values are adhered to. On the other hand, if the level of democratic quality is higher, also more cooperation can take place (Youngs Citation2009). The condition allows for investigating the extent of cooperation (especially on irregular migration) with countries where fundamental rights and liberal democratic values are infringed. What is more, Lavenex and Schimmelfennig (Citation2011) claim that incentives by the EU and a pre-existing civil society in the third country are supporting factors (this positive relationship between democracy and cooperation and the impact of conditionality have also been established by e.g. Freyburg et al. Citation2009).Footnote4

Condition 5: economic dependence

Economic dependence can lead to closer cooperation with the EU even though such a cooperation might not be a preference of the third country. At times, it may even infringe upon their own interests (Wunderlich Citation2012; cf. Boswell Citation2003; cf. Collyer Citation2011). Furthermore, this condition does not only relate to EU pressure, it also describes an interdependent economic relationship. Such a relationship can allow a third country to develop its own cooperation preferences (cf. Ademmer and Börzel Citation2013) and lead to trade-offs when it comes to migration cooperation. More dependence might mean that a third country is cooperating with the EU only on aspects that follow EU interests, while more interdependence might lead to migration cooperation on eye level.

The theoretical expectations are depicted in .

Table 1. Conditions and theoretical expectations.

Research design and data

When conducting fsQCA (combinations of) necessary and sufficient conditions leading to a specific outcome will be identified on the basis of qualitative and quantitative data (Ragin Citation1989, Citation2000, Citation2008; Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012). A condition is sufficient if it leads to the investigated result (here: extensive cooperation). To conduct fsQCA, raw data for each condition and the outcome are collected and then transformed into values between 0 and 1. This is called calibration. Scores bigger than 0.5 denote the presence of the case in the set for the condition/outcome, while scores below 0.5 denote that the cases are absent. 0.5 hence becomes the crossover point. A summary of operationalisation and calibration of the data is presented in .

Table 2. Overview of operationalisation, data and calibration of the conditionsTable Footnotea.

The reasons for conducting fsQCA are that not one single condition is likely to explain the EU’s cooperation with third countries and different paths are likely able to explain the outcome (respectively, ‘conjunctural causation’ and ‘equifinality’, Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012, 6f.). Against this backdrop, the objective is to connect the results of the QCA in terms of necessary and sufficient combinations of conditions to empirically shed light on the complex causal relationships (Ragin Citation2008, 54; Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012, 89f.). QCA operates in a way that is very sensitive to empirical contexts and allows to account for qualitative and quantitative differences. Being able to evaluate these differences and contextualise them with a larger number of cases is an advantage of QCA and valuable in the contentious and politicised field of EU migration cooperation. On a more technical level, the use of QCA is endorsed by the number of cases. The set contains 24 cases, which is a medium number (cf. Ragin Citation2008, 9; Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012, 153). The cases are: Albania, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Turkey; (2) potential candidate countries from the Balkans: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo; (3) ENP countries: Algeria, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Egypt, Georgia, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Moldova, Morocco, Palestinian Authorities, Syria, Tunisia, Ukraine and Russia.Footnote5

The year 2015 has been chosen as a key moment in time for this investigation. The year 2015 was a ‘crisis’ situation for the EU and there was an increase in the EU’s cooperation already in the years leading up to it, bringing into question the efforts that had been made. This cooperation has further intensified and broadened in 2015 and also resulted in the proposals for the new Pact on Migration in 2020. Yet, the proposals are made without fully understanding the dynamics of the ‘migration crisis’ of 2015/2016 and they suffer from a lack of involvement of actors from third countries (cf. Guild Citation2020). This study furthers the understanding of what happened until the crucial years of 2015 and 2016 and serve as a basis for further analysis of what happened since then, in order to evaluate the most recent policy proposals more adequately. The year 2015 was hence a watershed moment. Several of the conditions (such as economic dependence, existing relations and even state of democracy) do not tend to quickly change over time, so the results are still relevant for the recent proposals of 2020.

Conducting the fsQCA and discussion of results

The fsQCA identifies the necessary and then sufficient conditions (or a combination thereof) both for the presence and the absence of the outcome. The analysis has shown that no necessary condition can be identified for the migration cooperation (all consistency values are below the established mark of 0.9; Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012, 143). The closest condition to this threshold is ‘Existing Relations’ with 0.79 – which is unsurprising, having been identified as single sufficient condition.Footnote6 Other than that, the consistency values are all low. This is no surprise: Migration cooperation is complex and organised differently in the EU’s external relations (some may also say unsystematic, see e.g. European Parliament Citation2020).

The analysis of sufficiency is based on the truth table. It displays all logical combinations of conditions and the outcome, and shows the number of cases for each combination and the consistency in each row (). While the generally recommended minimum level of consistency is 0.75 (Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012, 128), I opted for a level of 0.9. This ensures that only very empirically consistent conditions are taken into account when the results are calculated. In addition, there is an empirical gap in the consistency scores between 0.86 and 0.96. Calibrating the scores with a 0.90 allows for separating these configurations (cf. Ragin Citation2008).

Table 3. Truth Table without Logical Remainders.

This truth table is minimised by Boolean algebra with the Quine-McClusky algorithm (with the software R, see Dusa Citation2019 and Oana and Schneider Citation2018). There are three different solution possibilities in QCA. I analyse the intermediate solution which is based on the inclusion of logical remainders (Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012, 169ff.). There are 18 possible configurations that are not present in reality (see Table 9 in supplement material). The results are presented in .

Table 4. Intermediate solution for presence of the outcomeTable Footnotea.

According to the fsQCA, the migration cooperation is extensive when either ‘existing relations’ are calibrated as high or a country is both more democratic and economically dependent on the EU. These results are consistent (both on their own and the solution as a whole). The two explanatory paths, that I respectively named close ties and strong leverage paths, cover a very satisfactory part of the outcome. It is noteworthy that ‘existing relations’ are measured by the status as (potential) candidate country and the closeness of existing relationships is identified as a sufficient condition on its own. Democratic standards (measured by Freedom House data) and economic dependence on the EU (measured by import, export, FDI and ODA) impact the outcome only in combination. These combinations are present for the following cases: Albania, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Turkey, Bosnia–Herzegovina, Kosovo, Moldova, Ukraine (both solution terms); Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Russia (only close ties), Tunisia (only strong leverage). The presence of cooperation can thus be explained for 14 cases out of the 24. The theoretical expectations for these terms are verified.

Solution path 1: close ties

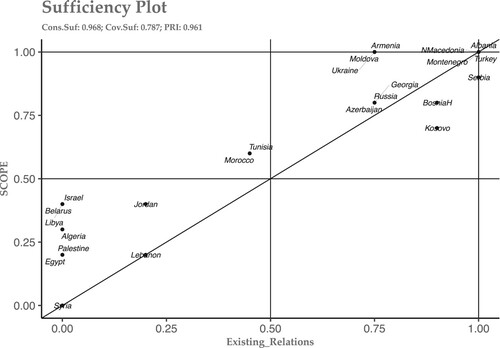

‘Existing relations’ is an individually sufficient condition. It shows the importance of close ties between the EU and a third country for migration cooperation. When looking at the XY-Plot (), only three cases are below the diagonal. They are all above 0.5 for migration cooperation so they are no real outliers (hence the high consistency score). These cases are Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia – all have close relations with the EU but not a broad cooperation on migration issues. In the case of Kosovo, this can be attributed to the fact that five EU member states still contest the independence of Kosovo which might stand in the way of becoming an accession candidate (hence the case has been calibrated with a lower score).

Figure 1. XY-plot for scope and existing relations. Note: ‘SCOPE’ is the abbreviation for the outcome ‘Migration Cooperation Extensity’.

For this reason, the condition holds the most explanatory power. It shows that the EU is first and foremost concerned with broadening migration cooperation with countries that have pre-existing close ties. The QCA proves this empirically by revealing this relationship for all countries in the Balkans and the Eastern neighbourhood. If this serves as a blueprint for broad cooperation, then migration cooperation can only be broadened if the EU applies this approach to other third countries, instead of excluding countries that are farther away from broad cooperation by focussing on fewer aspects of migration (which is mostly return). This mechanism is likely to be contingent on accession prospects that are not available outside these regions. Yet, close ties and incentives for cooperation seem to be relevant factors to improve the migration cooperation relationship. Given the absence of finality and the politicalness of rule transfer in the EU neighbourhood, the selective cooperation can change over time (cf. Ademmer and Börzel Citation2013; Casier Citation2011).

This result is consistent with the expectations of several authors (e.g. Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015, 48; cf. Schimmelfennig Citation2015). It confirms the nexus between migration cooperation and accession conditionality or the comparatively close relations with (particularly) Eastern neighbourhood countries. This may not be surprising, but it is interesting to show up so distinctly in a comparative research design. The EU’s prime objective to reduce irregular migration is easier to achieve with accession candidates, for instance when it comes to concluding EU readmission agreements (Cassarino Citation2010; Trauner and Kruse Citation2008). This has also political implications as close ties cannot be improved retroactively. However, the relations between the EU and third countries can be enhanced and upgraded to establish a meaningful relationship with the European neighbourhood, especially for the protection of refugees, as both the EU and several scholars contend (Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015; Tsourdi and De Bruycker Citation2016). This is not limited to the Eastern neighbourhood, as migration pressure in the year 2015 was originating from other regions, namely Syria and Afghanistan, but also West and North Africa, as acknowledged in the ‘Partnership Framework’ (European Commission Citation2016). The lack of involvement of third countries in drafting the 2020 Pact on Migration shows that furthering broad external relations might not have changed substantially since 2015, especially with those countries that have no full membership in the outcome cooperation extensity, e.g. Maghreb-countries (see also Guild Citation2020).

The close ties should however not be reduced to a division between accession candidates or the Eastern neighbourhood and the Southern neighbourhood. This simplification undermines cooperation efforts made since 2015, is unable to provide refugees with better protection and third countries with more support. As mentioned, not all countries (can) become accession candidates and further enlargement might still be a long way. Therefore, broad migration cooperation could be generally increased, also beyond the neighbouring countries, by devoting more effort into the relations, and not simply readmission (cf. Adam et al. Citation2020). Existing relations and accession candidacy should also not only be regarded as EU-leverage upon cooperating partners. Even though conditionality and ‘more for more’-programmes might follow such a logic, cooperation can be seen as more than just the EU influencing neighbouring states. The cases in the Eastern neighbourhood display very well that a broad scope of migration cooperation is possible. Notwithstanding, the reason why this might be a bit down the road can be found in the second part of the term.

Solution path 2: strong leverage

The combination of the conditions ‘Democracy’ and ‘Economic Dependence’ emphasises the strong leverage the EU has on third countries. The QCA shows that such a leverage is a relevant factor to explain the variation in migration cooperation. The result is partially surprising, as strong leverage could be assumed to only lead to migration cooperation in areas that are most relevant for the EU (again, mostly return). The reason for this might be that exerting strong leverage in a contentious field like migration needs to come along with incentives or services in return. The tools under investigation can be seen as policies of remote control for which incentives can become important. The lack of willingness to provide these incentives concomitant with applying strong leverage might explain the variance in migration cooperation extensity. The EU needs to avoid new rhetorical and procedural ‘entrapments’ that might result from promises the EU does not intend to keep that might be made in relation to its leverage (cf. Sasse Citation2008).

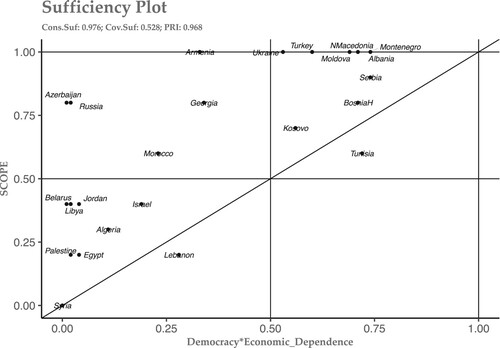

The XY-Plot combined for the two conditions is displayed in . Only the case Tunisia is below the diagonal and decreases the consistency for sufficiency, thus making it an outlier. The combination of conditions means that they need to be analysed simultaneously. On their own, democratic standards do not automatically imply a broad migration cooperation with the EU. The condition is, however, consistent for the outcome in combination with economic dependence. Still, the result that democracy is a relevant factor is consistent with the data. It is easier for the EU to cooperate with third countries that are democracies, especially in the sensitive field of migration. For instance, a readmission agreement is difficult to negotiate with countries in which human rights violations are widespread (cf. Cassarino Citation2010).

Figure 2. XY-plot for scope and democracy AND economic dependence. Note: ‘SCOPE’ is the abbreviation for the outcome ‘Migration Cooperation Extensity’.

This plot is also more scattered. Again, economic dependence on its own is unable to explain a country’s cooperation with the EU. Due to less intense trade relations with the EU, countries in the Southern neighbourhood are not as dependent on the EU as countries in the Balkans or the Eastern neighbourhood. Economic dependence should still not only be captured as dependence from a partner but also interdependence when it comes to trade relations. One possibility to engage in this area would be legal migration cooperation, which is not exclusive to the Eastern neighbourhood and could improve relations with the Southern neighbourhood. An integrative approach would benefit all parties – the EU, third countries and migrants (cf. Tsourdi and De Bruycker Citation2016). An EU focus on closer trade relations, also with non-democratic countries, and democracy promotion that brings more openness, trade and closer relationships have been discussed before (cf. Freyburg et al. Citation2009; Lavenex and Schimmelfennig Citation2009). The figure shows that countries that are both dependent on the EU and democracies are cooperating more with the EU. This result supports the previous finding that cooperation is likely to be more comprehensive with countries of the Eastern neighbourhood; in this region, there are mostly more democratic states with close economic relations to the EU.

Explaining the absence of migration cooperationFootnote7

Close ties and strong leverage have led to migration cooperation in the Balkans and the Eastern neighbourhood. This confirms the theoretical assumptions put forward by scholars using a Europeanisation or external governance lenses. The EU’s repeated claims of focusing on fighting the ‘root causes of migration’ seems to be only tenuously confirmed in the data. With Syria, there has been no cooperation at all. Back in 2015, the EU-Libyan cooperation was also weakly institutionalised, a fact that has changed however (Müller and Slominski Citation2020). Looking at the factors for the absence of cooperation, the outcome reveals two important findings. First, almost all conditions need to be absent so there is no migration cooperation (which emphasises the positive relationship between the conditions and the outcome). This shows that a minimum level of cooperation might always be in place (and to have a higher level thereof, a combination of conditions needs to be present). Second, the findings suggest that ‘migration flow’ from countries in the neighbourhood seems to have very limited impact on the extensity of cooperation, and only in the cases of Syria and Libya a high ‘migration flow’ in combination with the absence of all ‘administrative effectiveness’, ‘democracy’ and ‘existing relations’ leads to the absence of migration cooperation. This describes a set of cases where civil war and human rights abuses are prevalent which lead to a high number of people fleeing to Europe and explains the variation with regard to these cases. With the increase of asylum seekers in 2015 and 2016, also from the Western Balkans, we can see that migration cooperation extensity does not really impact asylum flows in turn either. This result, against the backdrop of e.g. the efforts of the EU to cooperate with the Libyan coastguard, shows that the situation in third countries might be of secondary interest (and can be considered ‘failing forward’, Cusumano and Riddervold (Citation2023), who argue that path dependency and stickiness can explain the EU’s backsliding into pre-existing institutional arrangements). In other words: If ‘migration flow’ has an impact, it might impede broader cooperation rather than broad cooperation making a difference for asylum seekers in the third countries – which in and of itself is actually undermined by EU action in recent years as the example with Libya shows.

This lends support to the conclusion that the EU is self-interested in its policymaking and cooperation efforts but also points to difficulties the EU has in establishing broad migration cooperation. A change in the cooperation-relationship did not come along with the increased cooperation up to 2015 (cf. Hampshire Citation2016). If the EU does not take this into account, recent migration cooperation efforts might not lead to the desired results but rather to a superficial and not sustainable relationship with third countries. The results point to the fact that changing existing cooperation patterns might be crucial, as the countries where ‘root causes’ for migration are more prevalent are situated in the Southern neighbourhood (and beyond). Here the level of democracy is often lower than in the Eastern neighbourhood, economic (inter)dependence is low and the existing relations are difficult to change retroactively (and cannot easily be imposed by conditionality). For broader migration cooperation with third countries, it is important to improve and strengthen overall cooperation relations, combined with democracy promotion and better and fairer trade relations and more general financial support, like the funding possibilities that are e.g. now available under the EU Trust Fund for Africa (cf. Garcia Andrade and Martin Citation2015, 100ff.; albeit for criticism see Oxfam Citation2020).

Conclusion

This article has sought to determine the conditions that explain a variance of third countries’ migration cooperation with the EU. The fsQCA shows that there is no necessary condition for migration cooperation. This may point to a rather diversified approach of the EU vis-à-vis third countries. The analysis of sufficient conditions demonstrates that either ‘existing relations’ or a combination of ‘democracy’ and ‘economic dependence’ can explain the level of cooperation. This shows that different paths and a combination of factors are needed to explain the EU’s migration cooperation with neighbouring states.

The condition ‘existing relations’ (measured by the closeness of a third country’s political relations) is sufficient on its own. In simple terms, if a country seeks closer ties if not full membership, the country is also likely to have broad cooperation with the EU in the migration domain. This confirms existing theoretical assumptions (e.g. Lavenex Citation2004). The other findings are more innovative in terms of contributing to the state of the art. Strong leverage, as combination of ‘democracy’ and ‘economic dependence’, explains broad migration cooperation with the EU. The EU hence tends to cooperate with third countries that are democratic and economically closely intertwined with the EU. This path has been particularly visible in Eastern Europe and Western Balkan states. Both solution paths mostly cover the same set of cases; this shows that the EU might seize political opportunities when it comes to the cooperation with third countries rather than focusing on ‘fighting root causes of migration’.

This interesting finding is echoed by the lack of relevance of the condition ‘Migration Flow’, notably pre-2015. The condition is neither included for the presence of the outcome nor mostly its absence, only in the cases of Syria and Libya it makes a difference (due to the conflicts in the countries). This points to the fact that the opportunity structure for having a cooperation may have outweighed factors relating to the actual need of cooperation (such as migration flows). The migration situation in the third countries may have been rather of secondary interest for the EU in terms of institutionalising migration cooperation (at least by 2015).

Avenues for future research based on these results are manifold, given the timely character of the topic. To shed light on the causal mechanisms of the identified paths and to look into regional intricacies, case studies and process tracing would be needed, also to support and contextualise the results. The study could be further complemented by considering domestic factors and decision-making processes in third countries (see e.g. Tittel-Mosser Citation2023, on the role of epistemic communities; Vaagland Citation2023, on the importance of moral arguments in negotiations). Updating the data to account for the EU migration cooperation efforts since 2016 is, furthermore, a viable endeavour.

Notwithstanding, the QCA results point to an EU that is self-interested in the cooperation efforts, but also show the difficulties of the EU in broadly cooperating with third countries (cf. Hampshire Citation2016). Taking this fully into account would be a necessary step to improve relations with third countries beyond repeating policy proposals that seem to remain on surface level for countries outside of accession candidates and the Eastern neighbourhood.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (297.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewer and the guest editors of this special issue for their constructive and very useful comments. Feedback by participants of the workshop ‘Europe’s Role in Global Migration Governance’ in Mainz 2019 and by Florian Trauner on earlier versions of this article is gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 For a discussion on terminology regarding the ‘migration crisis’, see Niemann and Zaun (Citation2018).

2 QCA-terminology is used here and has implications for the phrasing of the research question. I test conditions that lead to a specific outcome and refrain from using the terms ‘dependent’ and ‘independent variable\ (cf. Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012).

3 Freedom House data is used to measure the condition democracy, as is explained in the online supplement material.

4 The inversion of the argument, in other words that the EU advocates a solely value-bound policy, that precludes the EU from cooperation with autocratic third countries, can be excluded, also due to the success of conditionality (Lavenex and Schimmelfennig Citation2011; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Citation2004; Trauner and Kruse Citation2008).

5 The case selection is explained further in the online supplement material.

6 Additionally, the absence of close ‘Existing Relations’, has been identified as necessary condition for the absence of migration cooperation extensity. This emphasises the importance of the condition (see supplement material).

7 When conducting a QCA, the conditions are also analysed for the absence of the outcome, to investigate the paths under which the outcome is not present (see supplement material, table 12).

References

- Adam, Ilke, Florian Trauner, Leonie Jegen, and Christof Roos. 2020. “West African Interests in (EU) Migration Policy: Balancing Domestic Priorities with External Incentives.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (15): 3101–3118. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1750354

- Ademmer, Esther, and Tanja Börzel. 2013. “Migration, Energy and Good Governance in the EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood.” Europe-Asia Studies 65 (4): 581–608. doi:10.1080/09668136.2013.766038

- Adepoju Aderanti, Femke van Noorloos, and Annelies Zoomers. 2010. “Europe's Migration Agreements with Migrant-Sending Countries in the Global South. A Critical Review.” International Migration 48 (3): 42–75. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00529.x

- Betts, Alexander. 2010. “Migration Governance. In: International Organization for Migration, Background Paper WMR 2010, IOM, Geneva.”

- Börzel, Tanja, and Thomas Risse. 2012. “From Europeanisation to Diffusion: Introduction.” West European Politics 35 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/01402382.2012.631310

- Bosse, Giselle, and Alena Viera. 2018. “Human Rights in Belarus: The EU’s Role Since 2016.” European Parliament, Policy Department for External Relations. PE 603.870, June 2018.

- Boswell, Christina. 2003. “The 'External Dimension' of EU Immigration and Asylum Policy.” International Affairs 73 (3): 619–638. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.00326

- Carrera, Sergio, Leonhard den Hertog, and Joanna Parkin. 2012. “EU Migration Policy in the wake of the Arab Spring. What prospects for EU-Southern Mediterranean Relations?” In: MEDPRO Technical Report No. 15/August 2012.

- Carrera, Sergio, Raluca Radescu, and Natasja Reslow. 2015. “EU External Migration Policies. A Preliminary Mapping of the Instruments, the Actors and their Prioritiesof Temporary Mobility of People.” EURA-net project report with CEPS.

- Casier, Tom. 2011. “To Adopt or Not to Adopt: Explaining Selective Rule Transfer Under the European Neighbourhood Policy.” Journal of European Integration 33 (1): 37–53. doi:10.1080/07036337.2010.526709

- Cassarino, Jean-Pierre. 2010. “Readmission Policy in the European Union.” European Parliament, Policy Department for Internal Policies. PE 425.632, September 2010.

- Cham, Omar, and Ilke Adam. 2021. “Only the Politicisation and Framing of EU Migration Cooperation in The Gambia. Transition to Democracy as a Game Changer?” Territory, Politics, Goverance, 1–20. doi:10.1080/21622671.2021.1990790.

- Collett, Elizabeth, and Aliyyah Ahad. 2017. “EU Migration Partnerships: A Work in Progress”. Brussels: Migration Policy Institute.

- Collyer, Michael. 2011. “The Development Challenges and the EU.” In: EUI Cadmus Research Report 2011:8.

- Cusumano, Eugenio, and Marianne Riddervold. 2023. “Failing through: European Migration Governance Across the Central Mediterranean.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (12): 3024–3042. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2193713.

- Dusa, Adrian. 2019. QCA with R. A Comprehensive Resource. Wiesbaden: Springer International Publishing.

- European Commission. 2011a. “The Global Approach to Migration and Mobility”, EU COM (2011) 743 final, Brussels, November 18, 2011.

- European Commission. 2011b. “Evaluation of EU Readmission Agreements”, EU COM (2011) 76 final, Brussels, January 23, 2011.

- European Commission. 2013. “Thematic Programme ‘Cooperation with Third Countries in the areas of Migration and Asylum’: 2011-2013 Multi-Annual Strategy Paper”. European Commission, Brussels, December 31, 2013.

- European Commission. 2015. “A European Agenda on Migration”, EU COM (2015) 240 final, Brussels, May 13, 2015.

- European Commission. 2016. “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council and the European Investment Bank on establishing a new Partnership Framework with Third Countries under the European Agenda on Migration”. EU COM 2016 385 final, Strasburg, June 7, 2016.

- European Council. 2002. “Criteria for the identification of third countries with which new readmission agreements need to be negotiated.” Council of the EU, EU 7990/02, Brussels, April 15, 2002.

- European Parliament. 2020. EU External Migration Policy and the Protection of Human Rights. Policy Department for External Relations, PE 603.512, September 2020.

- Freyburg, Tina, Sandra Lavenex, Frank Schimmelfennig, Tatiana Skripka, and Anne Wetzel. 2009. “EU Promotion of Democratic Governance in the Neighbourhood.” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (6): 916–934. doi:10.1080/13501760903088405

- Garcia Andrade, Paula, and Ivan Martin. 2015. EU Cooperation with Third Countries in the Field of Migration. European Parliament, Policy Department for Internal Policies. PE 536.469, October 2015.

- Geddes, Andrew. 2005. “Europe’s Border Relationships and International Migration Relations.” Journal of Common Market Studies 43 (4): 787–806. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2005.00596.x

- Guérin, Nina. 2018. “One Wave of Reforms, Many Outputs: The Diffusion of European Asylum Policies Beyond Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (7): 1068–1087. doi:10.1080/13501763.2018.1425476

- Guérin, Nina, and Berthold Rittberger. 2020. “Are Third States Pulling the Strings? The Impact of Domestic Policy Change on EU-Third State Cooperation.” Journal of European Integration 42 (7): 991–1008. doi:10.1080/07036337.2019.1705801

- Guild, Elspeth. 2020. “Negotiating with Third Countries under the New Pact: Carrots and Sticks?” December 2, 2020, http://eumigrationlawblog.eu/negotiating-with-third-countries-under-the-new-pact-carrots-and-sticks.

- Hailbronner, Kai. 1997. “Readmission Agreements and the Obligation of States Under Public International Law to Readmit Their Own and Foreign Nationals.” Zeitschrift für Ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht 57 (1): 1–50. https://www.zaoerv.de/57_1997/57_1997_1_a_1_50.pdf.

- Hamood, Sara. 2008. “EU-Libya Cooperation on Migration: A Raw Deal for Refugees and Migrants?” Journal of Refugee Studies 21 (1): 19–42. doi:10.1093/jrs/fem040

- Hampshire, James. 2016. “Speaking with one Voice?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (4): 571–586. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1103036

- Hille, Peter, and Christoph Knill. 2006. “‘It’s the Bureaucracy, Stupid.’ The Implementation of the Acquis Communautaire in EU Candidate Countries, 1999–2003.” European Union Politics 7 (4): 531–552. doi:10.1177/1465116506069442

- Kelley, Judith. 2006. “New Wine in Old Wineskins: Promoting Political Reforms Through the New European Neighbourhood Policy.” Journal of Common Market Studies 44 (1): 29–55. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2006.00613.x

- Keohane, Robert. 1984. After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. New Jersey: Princeton.

- Langbein, Julia, and Tanja Börzel. 2013. “Introduction: Explaining Policy Change in the European Union’s Eastern Neighbourhood.” Europe-Asia Studies 65 (4): 571–580. doi:10.1080/09668136.2013.766042

- Lavenex, Sandra. 2004. “EU External Governance in Wider Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 11 (4): 680–700. doi:10.1080/1350176042000248098

- Lavenex, Sandra, and Frank Schimmelfennig. 2009. “EU Rules Beyond EU Borders: Theorizing External Governance in European Politics.” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (6): 791–812. doi:10.1080/13501760903087696

- Lavenex, Sandra, and Frank Schimmelfennig. 2011. “EU Democracy Promotion in the Neighbourhood: From Leverage to Governance?” Democratization 18 (4): 885–909. doi:10.1080/13510347.2011.584730

- Lavenex, Sandra, and Emek Uçarer. 2004. “The External Dimension of Europeanization: The Case of Immigration Policies.” Cooperation and Conflict 39: 417–443. doi:10.1177/0010836704047582

- Lindblom, Charles. 1965. The Intelligence of Democracy. New York: The Free Press.

- Mahoney, James, Eric Kimball, and Kendra L. Koivu. 2009. “The Logic of Historical Explanation in the Social Sciences.” Comparative Political Studies 42 (1): 114–146. doi:10.1177/0010414008325433

- Müller, Patrick, and Peter Slominski. 2020. “Breaking the Legal Link but not the law? The Externalization of EU Migration Control Through Orchestration in the Central Mediterranean.” Journal of European Public Policy, 28 (6): 801–820. DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2020.1751243.

- Niemann, Arne. 2008. “Dynamics and Countervailing Pressures of Visa, Asylum and Immigration Policy Treaty Revision.” Journal of Common Market Studies 46 (3): 559–591. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2008.00791.x

- Niemann, Arne, and Natascha Zaun. 2018. “EU Refugee Policies and Politics in Times of Crisis: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1111/jcms.12650

- Niemann, Arne, and Natascha Zaun. 2023. “EU External Migration Policy and EU Migration Governance: Introduction.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (12): 2965–2985. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2193710.

- Oana, Ioana-Elena, and Carsten Q Schneider. 2018. “SetMethods: An Add-on Package for Advanced QCA.” The R Journal 10 (1): 507–533. https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2018/RJ-2018-031/index.html.

- Oxfam. 2020, , January. The EU Trust Fund for Africa: Trapped Between aid Policy and Migration Politics. Oxafm Briefing Paper. doi:10.21201/2020.5532.

- Ragin, Charles C. 1989. The Comparative Method. Moving Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies. Los Angeles, Berkley: University of California Press.

- Ragin, Charles. 2000. Fuzzyset Social Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ragin, Charles. 2008. Redesigning Social Inquiry. Fuzzy Sets and Beyond. London, Chicago: University Press of Chicago.

- Reslow, Natasja, and Maarten Vink. 2015. “Three-Level Games in EU External Migration Policy: Negotiating Mobility Partnerships in West Africa.” Journal of Common Market Studies 53 (4): 857–874. doi:10.1111/jcms.12233

- Rihoux, Benoit, and Gisele De Meur. 2009. “Crisp-Set Qualitative Comparative Analisis (csQCA).” In Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques, edited by Benoit Rihux, and Charles Ragin, 33–68. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Sasse, Gwendolyn. 2008. “The European Neighbourhood Policy: Conditionality Revisited for the EU’s Eastern Neighbours.” Europe-Asia Studies 60 (2): 295–316. doi:10.1080/09668130701820150

- Schimmelfennig, Frank. 2015. “Europeanization beyond Europe.” Living Reviews in European Governance 10 (1). doi:10.14629/lreg-2015-1.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank, and Ulrich Sedelmeier. 2004. “Governance by Conditionality: Eu rule Transfer to the Candidate Countries of Central and Eastern Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 11 (4): 669–687. doi:10.1080/1350176042000248089.

- Schneider, Carsten, and Claudius Wagemann. 2012. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences. A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Scipioni, Marco. 2018. “Failing Forward in EU Migration Policy? EU Integration After the 2015 Asylum and Migration Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (9): 1357–1375. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1325920

- Sedelmeier, Ulrich. 2006. “Europeanisation in New Member and Candidate States.” Living Reviews in European Governance 1: 3. doi:10.12942/lreg-2006-3.

- Tittel-Mosser, Fanny. 2023. “Legal and Policy Relevance of EU Mobility Partnerships in Morocco and Cape Verde: the Role of Epistemic Communities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (12): 3043–3059. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2193714.

- Trauner, Florian, and Imke Kruse. 2008. “EC Visa Facilitation and Readmission Agreements: Implementing a New EU Security Approach in the Neighbourhood”. In: CEPS Working Document No. 290, April 2008. Online: www.ceps.eu/ceps/dld/1475/pdf.

- Trauner, Florian, and Sarah Wolff. 2014. “The Negotiation and Contestation of EU Migration Policy Instruments.” European Journal of Migration and Law 16 (1), 1–18. doi:10.1163/15718166-00002046

- Tsourdi, Evangelia, and Philippe De Bruycker. 2016. “Building the Common European Asylum System Beyond Legislative Harmonisation: Practical Cooperation, Solidarity and External Dimension.” In Reforming the Common European Asylum System, edited by Vincent Chetail, Philippe De Bruycker, and Francesco Maiani, 471–538. Leiden: Brill.

- Vaagland, Karin. 2023. “How Strategies of Refugee Host States are Perceived by Donor States: EU Interpretations of Jordanian Migration Diplomacy.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (12): 3085–3100. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2193715.

- Weinar, Agnieszka. 2011. "EU Cooperation Challenges in External Migration Policy". In: Research Paper-Background Report EU-US Immigration Systems 2011/2012, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute, Florence.

- Wunderlich, Daniel. 2012. “The Limits of External Governance: Implementing EU External Migration Policy.” Journal of European Public Policy 19 (9): 1414–1433. doi:10.1080/13501763.2012.672106

- Youngs, Richard. 2009. “Democracy Promotion as External Governance?” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (6): 895–915. doi:10.1080/13501760903088272