ABSTRACT

This study looks at how ordinary Kurdish refugees and asylum seekers set up self-governing formations to organise their life in border cities on the periphery of European societies. The Kurdish immigrants organise themselves into social communities that serve as autonomous social spaces in which they form and exercise self-governance, navigate through bureaucratic and structural obstacles, and regulate their cultural and social affairs. In this paper, I argue that contextual Kurdish identities and the immigrants’ capacity to respond are the fundamental components of four different models of immigrant self-governing establishments. Ideological agendas, kinship relationships, and shared spatial origins are significant contextual elements of collective identities that they use to construct three models of self-governance, whereas their responses to common concerns drive them to form a fate-based model of self-governance. Based on ethnographic field research and 76 in-depth interviews with Kurdish refugees and asylum seekers in bordering cities in Northern, Southern, and Western Europe, the article illuminates four self-governing models of ordinary Kurdish immigrants, their various patterns and identities, as well as internal dynamics. It sheds light on how these self-governing models of the marginalised Kurdish immigrants arise from below to produce and regulate social life without interference from state authorities.

Introduction

Multiple Middle Eastern crises, notably the Syrian War, pro-Turkish jihadist attacks in Syria and Iraq, and the collapse of the so-called peace process between the Turkish government and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in the mid-2010s, resulted in waves of forced Kurdish immigrants seeking asylum in Europe. The European recipient governments confronted significant political and social challenges in registering, receiving, accommodating, and subsequently integrating large numbers of Kurdish and non-Kurdish asylum seekers from the Middle East region (Joensen and Taylor Citation2021). While failing to appropriately address the bulk of the cultural and social requirements of these newly-arrived forced immigrants, European governments allocated most of them to border regions inside their national territories and restricted their movement. Some Kurdish asylum seekers, primarily from Syria, were granted refugee status instantly, while others from Turkey and Iraq endured a lengthy asylum process. Refugees were obliged to settle in their cities of arrival and adapt to their hosts’ cultural and social structures, as well as the labour market. The paperwork, housing, new language, employment, welfare, education, and cultural and social demands of refugees all posed structural challenges during settlement and integration processes. Those still waiting for a decision on their asylum claims have been denied access to fundamental legal, social, and structural support services, including resident permits, adequate housings in refugee camps, and translation services. The forced Kurdish immigrants are in a vulnerable and marginalised situation due to their varied legal statuses and cultural and social challenges. They dwell on the margins of European societies, where they are physically visible but are culturally and socially marginalised. Nonetheless, they endeavour to govern themselves in a variety of ways to meet their requirements in the absence of local and national authorities. How do forced Kurdish immigrants exercise self-governance to manage their lives across cultural, legal, social, and structural domains?

This article explores how forced Kurdish immigrants, inspired by identities from their home countries and newly emerging situations in host cities, organise themselves into social communities, creating autonomous social spaces, and build a variety of self-governance models. These models of self-government do not develop in a vacuum; they are shaped by contextual identities and responsive factors. Contextual identities are anchored in the communal, traditional, and spatial practices of Kurdish society in their countries of origin, whereas responsive factors are generated by immigrants’ everyday demands in new environments. Their varied identities are not necessarily novel inventions in receiving cities but rather originate from the hybrid structures of Kurdish society, which trace back to multiple dialects, faiths, classes, countries of origin – Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria – and the hegemonic influence of major political actors in Kurdish regions. These identities shape immigrants’ self-governing model formations, which are composed of bottom-up, horizontally organised, and autonomous networks, committees, joint initiatives, and assemblies. The self-governance structures aid immigrant communities in tackling structural, legal, and bureaucratic challenges such as a lack of resident permits, host language requirements, employment obligations, and paperwork management in settlement and integration processes and empower them through self-management, self-services, and self-help in settlement cities and beyond.

The migration governance literature, whose key players and institutions include subnational and supranational government agencies, international organisations, local and global advocacy groups, academics, and state-sponsored formal immigrant and diaspora associations, barely captures the self-established governance formations of forced immigrants (Betts Citation2011; Gamlen Citation2014; Pries Citation2019; Mencütek Citation2019). The fields and strategies of migration governance are controlled by non-refugee actors, laws, and settings, which standardise immigrant concerns to separate them from native citizens and treat them as regulatory objects (Ashutosh and Mountz Citation2011). Yet, some studies examine the formal, hierarchical, and macro-level associations and agencies of immigrants and pay attention to the forms, patterns, and practices of refugee-led organisations (RLOs). These were especially vocal during the COVID-19 pandemic as a result of their exclusion from COVID-related aid following lockdown (Betts, Easton-Calabria, and Pincock Citation2021; Benson et al. Citation2022). RLOs are commonly described in this literature as established marginalised associational structures that operate as advocacy organisations and service providers in urban regions (Pincock, Betts, and Easton-Calabria Citation2020; Benson Citation2019; Montaser Citation2019; Pascucci Citation2017; Mainwaring Citation2016). However, RLOs’ formations, operations, and patterns generally lack contextual analyses of their ethnic, tribal, spatial, and political identities, which are vital to their self-motivation and ability to rule themselves.

The absence of self-governing models among immigrants in migration governance literature, along with a lack of attention to their context, create a gap that obscures our understanding of how they establish self-governing formations and what pushes them to gain and assert power over their lives. This study addresses the gap in migration governance literature by examining the context of forced Kurdish immigrants in self-governing processes and self-organized behaviours that affect their patterns, problem fields, and coping strategies. Thus, the article highlights the blind spot regarding the undermined reality of immigrants’ self-governance beyond the state sectors, which is influenced by distinct non-immigrant ideological goals and institutional discourses (McConnachie Citation2014; Morsut and Ivar-Kruke Citation2018; Cronin Citation2008). Drawing on self-governance, autonomy and space theories, this article discusses self-governance of ordinary immigrants in autonomous social spaces living on the margins of dominant societies, where they produce their social life in and across settlement cities. In what follows, I discuss the conceptual and theoretical approach to self-governance and move on to discuss the methods for data collection in the following section. Then I describe the context and evolution of Kurdish self-governance. The final sections analyse empirically the domains of problems, practices, and coping strategies of self-governance of Kurdish immigrants.

Conceptualisation of self-governance in autonomous social space

Several studies examined immigrants’ collective agency to organise, represent, and provide self-services. In refugee camps in the global south, displaced refugees build collective agency to produce social life, govern it autonomously, and challenge state sovereignty (Küçükkele Citation2022; Reichert Citation2014; Hanafi and Long Citation2010). Self-governing formations in refugee camps attempt to compete with states and serve their communities’ everyday social needs by exercising cultural and political autonomy. These subjectivities regard their collective displacement as a result of their homeland's liberation struggle for political legitimacy and self-determination (Küçükkele Citation2022; Reichert Citation2014; Sayigh Citation2011). By developing autonomous perspective and collective agency, refugees not only perceive camps as protecting reservoirs but also convert them into social and humanitarian spaces (Krause Citation2018; Kassa Citation2019).

Other studies pay attention to immigrants’ non-political agency, although they participate in political actions. Immigrants’ self-organising activities are tied to their capacity and self-motivation rather than political and ideological struggles or homeland agendas to form their own states or self-determination. The actions of immigrants to autonomously respond to their everyday material and non-material demands, as well as provide self-service, result in their collective agency (Montaser Citation2019; Papadopoulos and Tsianos Citation2013). It allows them to experience cultural and social sovereignty after governmental authorities fail to offer resources for their settlement and integration or meet their cultural demands. In other circumstances, refugees in the global South self-organized through ‘community’ construction and ‘self-reliance’ (Pascucci Citation2017). Communities, as ‘informal’ and ‘precarious’ social networks, are venues of ‘self-reliance’ that are autonomous and serve as the bedrock of social ties in the form of social capital for self-assistance, empowerment, and resilience. Community-based self-governance in forced migration is not only limited to collective agency in camps in the global South, which become autonomous spaces for self-organisation, self-reliance, and empowerment, but is also exercised by forced immigrants outside refugee camps in the global North. Forced immigrants form most formal and informal RLOs to gain agency, impact their rights and situations, and provide self-services through activism (Jong and Ataç Citation2017). Refugees in the global north are forming autonomous self-support organisations to express solidarity after being victimised and objectified by natural, political, and social crises, including Europe's refugee crisis or the COVOID pandemic (Benson et al. Citation2022; Betts, Easton-Calabria, and Pincock Citation2021; Picozza Citation2021; Benson Citation2019; Fontanari and Ambrosini Citation2018; Gateley Citation2014).

The vast migration literature covers forced immigrant self-governance through collective agency and autonomous spaces in many circumstances and regions. These self-governing formations have been critical components in overcoming hurdles and changing the political agendas, discourses, and actors impacting their lives. Self-governance in the context of Kurdish immigrants involves a combination of networked communities and autonomous social spaces. Their self-governing formations are the result of collective membership in identity-based communities that operate and interact in autonomous social spaces. To address this process holistically, I will briefly explain the relationship between self-governance, a community-based approach, and autonomous social spaces.

The concept of ‘community’ has been studied from philosophical, sociological, and anthropological perspectives and has multiple definitions. The community concept, according to Elisabeth Frazer, is a structural and functional entity on the one hand and a collection of constructive and social subjectivities on the other (Citation1999, 66). In relation to the former, the community is ‘an entity or group of individuals, an institution or series of institutions’ (ibid).This communitarian concept includes formal and informal institutional ties in networks or organisations that serve their constituents. However, Frazer's second constructive and social definition of community—‘a particular kind of relation between persons’ based on ‘shared principles, laws, meanings, goods, goals; a shared centre; shared life’—is illuminating (ibid.). As a result, a community can be defined as a networked group of people who form social relationships and share ideals to elicit mutual commitment and collective consciousness. According to Anthony Cohen, communities are a matter of collective consciousness, forming boundaries through beliefs and symbols in the view of their members (Citation1985, 13). These members feel a sense of belonging to cultural, ethnic, kinship, political, or social communities; they build their collective structures and interact in autonomous spaces where they produce social life through social relationships, the negotiation of informal citizenship, and the provision of autonomous cultural, economic, and social service practices.

The autonomous social spaces are inspired by ‘autonomous geographies,’ which have been applied in studies of social movements and indigenous communities. ‘Autonomous geographies’ are, in the words of Pickerill and Chatterton, ‘those spaces where people desire to constitute non-capitalist, egalitarian, and solidaristic forms of political, social, and economic organization.’ These spaces should be established ‘through a combination of resistance and creation’ (Citation2006, 730). To confront neoliberal governance, its power, dominant laws, and normative patterns, the authors suggest autonomous and collective democratic politics, group citizenship, identity, and economic independence (Dinerstein Citation2015; Pickerill and Chatterton Citation2006; Chatterton Citation2004). However, this concept is overloaded with political and ideological premises, and subjectivities pursue nurturing ambitions to seise institutional power to contest political sovereignty (Dinerstein Citation2015). In contrast, autonomous social spaces in relation to immigrants are not a political or geographical landscape for immigrants to seise power and confront state authorities, but rather a kind of communal social production, where ideas are generated, communication and social interactions are constructed, and social practices are established. In a nutshell, ‘social space’ denotes the production of a community's social life (Lefebvre Citation1991, 33–36). Lefebvre defined social space as ‘social actions,’ both individual and collective actions of subjects (ibid.). The social space is where people interact. Social spaces are autonomous, where subjects operate with impunity in relation to objects to produce social life, according to Lefebvre (ibid.:102). Pickerill and Chatterton (Citation2006, 732) defined autonomy as a socio-spatial characteristic that connects ‘complex networks and relations,’ including many ‘autonomous projects across time and space, with potential for translocal solidarity networks.’ Thus, individuals and their interactions are not limited to refugee camps, villages, towns, or countries, nor to certain affairs or actions, depending on some actors. In autonomous social spaces, immigrants participate in cultural and social activities outside of state authorities, laws, and trajectories. Kurdish immigrants’ self-governing models engage in autonomous social spaces for collective and social actions.

Research design and methods

This study examines Kurdish immigrants’ self-governance in many European countries using diverse methods that comprise a number of data collection and analysis approaches deployed through ethnographic fieldwork in eight locations: Bari, Nice, Antipas, Landshut, the Danish Island of Bornholm, Salzburg, Malmo, and Lund between February and October 2019 through 76 semi-structured and in-depth interviews, participant observations, and focus groups. These cities were chosen because of their proximity to neighbouring countries, their role as epicentres for the reception of newly-arrived asylum seekers, and the absence of diasporic and refugee-led organisations. Kurdish asylum seekers who requested asylum in these countries were allocated to these cities by national authorities. Most Kurds I interviewed told me that they were arrested and fingerprinted in these locations while travelling to neighbouring countries. They were placed in refugee camps near these cities after applying for asylum.

As a basis for in-depth interviews and participant observations, I used snowball sampling to contact Kurdish refugee shop owners in these cities, where they run teahouses, mini-supermarkets, and restaurants, serving as gathering points for fellow Kurdish immigrants. Following personal encounters, I visited their shops, homes, or refugee camps and joined their conversations and social gatherings. Finally, I conducted group and in-depth interviews with Kurdish immigrants in Sorani, Kurmanji, and Turkish. The vast majority of these interviewees were men who had left their spouses and families in Kurdish regions. However, the women and children are legally reunited with their male spouses, who have been granted refugee status. The interviewees in Landshut and Salzburg claimed that men are frequently the first to flee in order to save women from perilous journeys. They implied that this treatment of women is linked to cultural and traditional practices within Kurdish society. These practices limit women to the domestic domain and place them under the jurisdiction of families and close relatives as social institutions, providing them with safety and protection against vulnerability, maltreatment, and exploitation.

There were no naturalised citizens or permanent residents among those interviewed; refugees had one-to-three-year residency permits, while asylum applicants had been granted permission for a few weeks to three months. The majority of refugees in Malmo, Landshut, Bornholm, and Salzburg were unemployed and took language courses, but those in southern France mostly worked on construction sites. Asylum seekers in Sweden, Denmark, Austria, and France were not permitted to work, although those in Germany and Italy were allowed to work three months after their asylum applications. In Austria, Denmark, Germany, and Sweden, asylum seekers were accommodated in refugee camps, but in France and Italy, they lived undocumented in self-rented flats, self-built makeshift shacks, or were homeless.

I adopted the interpretive approach to analyse the conditions, practices, and strategies of Kurdish immigrant formations within the cultural and historical context of their native countries. Following my interactions with Kurdish immigrants, I developed a comprehensive understanding of their self-governance process based on constructed knowledge derived from their perspectives and experiences (Tracy Citation2013, 40–42). My personal experience as a former Kurdish refugee, both insider and outsider, was informative, but as a naturalised citizen, I placed myself critically on the outside through my insider knowledge. However, numerous Kurdish immigrants told me that they were delighted to meet me and shared their views because of our shared Kurdish and refugee backgrounds. They expressed the hope that I could articulate their opinions, disseminate their ignored dilemma, and mediate between them and European policymakers to draw attention to their precarious conditions.

The context of Kurdish refugee self-governance

The hybrid segments and various tribes of Kurdish society have historically established self-governance formations as basic components of their desired autonomous structures. These formations were inspired by the common understanding and values of their traditions, rituals, and kinship relationships that led to their local collective actions (Özok-Gündoğan Citation2022; Klein Citation2011; McDowall Citation2007). The struggle of a few Kurdish tribes for territorial autonomy has a long history of preserving their self-governance in relation to economic independence, self-legislation, and self-administration (Ates Citation2021; Van-Bruinessen Citation1992, 158–175). While some Kurdish tribes opposed the centralisation of ruling authorities outside of Kurdish groups, others collaborated with Ottoman rulers for locally confined self-interests (Ates Citation2021; Bajalan Citation2021; Klein Citation2011; McDowall Citation2007). Nevertheless, under Ottoman rule, self-governing Kurdish models and practices existed within the anthropological, cultural, and sociological architecture of the Kurdish tribes. Dominated by sheikhs and tribal chiefs, Kurds enjoyed semi-independent living arrangements and often avoided complying with Ottoman rules (Yadirgi Citation2017; Olson Citation1991). For instance, they organised local federations and regional tribal confederations to respond to collective challenges posed not only by the Ottoman rulers but also by Arab and Turkmen tribes (Bajalan Citation2021; McDowall Citation2007). They also handled their own socioeconomic needs and settled intra-Kurdish conflicts on their own (Yadirgi Citation2017; Tas Citation2014). Although Ottoman authorities sought to regulate and abolish Kurdish self-governing structures in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Kurdish tribes and movements revolted to retain their autonomous traditions (Bajalan Citation2021; Soleimani Citation2021; Olson Citation1991).

Self-governing Kurdish structures and practices persisted inside the nation-state system following the Ottoman collapse (Özok-Gündoğan Citation2022). However, subsequent governing authorities’ interference and colonising policies have encroached on Kurdish autonomy and self-governance. So, the Kurds have not been allowed to maintain many important elements of their socio-cultural traditions or customs in newly constituted Turkey, Iraq, and Syria (Özok-Gündoğan Citation2022; Bajalan Citation2021; Soleimani Citation2021; Izady Citation1992; Tejel Citation2009; Yeğen Citation2007). Some customs, however, such as the board of aldermen for conflict settlement, the trading of socio-economic products between peasants and businesses outside state jurisdiction, and the provision of alternative medicine, have continued to exist in Kurdish regions (Tas Citation2014). It is worth emphasising that this Kurdish self-governing model has been and continues to be targeted for eradication under the guise of modernisation and civilisation. Turkish institutions, for example, continue to label Kurdish traditions, cultures, and customs as ‘backward,’ ‘tribal,’ and ‘pre-modern,’ while presenting the imposed Turkish culture and way of life as ‘civilised’ and ‘modern’ (Yeğen Citation2007, Citation2021; Gambetti and Jongerden Citation2015; Gündogan Citation2015). Due to ethnic and national distinctions between Kurds, Arabs, and Persians, Kurds in Syria, Iraq, and Iran have faced comparable colonial policies (Olson Citation1991). Shared confessional affiliations (such as Sunni or Shia) with Turks, Persians, and Arabs have not aided Kurds in achieving self-governance legitimacy (Leezenberg Citation2021; Soleimani Citation2021; Olson Citation1991). Kurdish refugees have brought these self-governing traditions into European cities and deployed them to organise themselves, create mutual solidarity, and negotiate their informal group citizenship based on shared cultural, economic, and social concerns.

Problem areas of Kurdish immigrants

Kurdish immigrants in the cities in question encounter four main concerns: protracted asylum procedures; settlement and adaptation; assimilation and alienation; and homeland politics consequences. These domains affect their living conditions in host cities, home countries, and daily lives (Jacobsen Citation2019). The first concern is the prolonged asylum procedure, which usually produces uncertainty and discrimination among asylum seekers. This could be part of a legal framework that restricts Kurdish asylum seekers’ mobility, employment, and settlement rights. They fail to achieve recognition and are thus driven into liminality. Immigration agencies in Northern and Western Europe tend to adopt similar procedures to prolong asylum rulings for years. Applicants claim that the authorities’ delay in ruling on their cases is deliberate, as their cases are highly political and involve geopolitical interests.Footnote1 One recent example is when Turkey withheld its support for Finland and Sweden joining NATO until it secured political concessions from European states regarding its repressive Kurdish policy. Therefore, the Swedish, Finnish, and Turkish governments signed a trilateral memorandum to resolve Turkish ‘security concerns.’ Sweden and Finland confirmed their commitment to scrutinise and extradite certain Kurdish asylum seekers to Turkey (Milne, Foy, and Pitel Citation2022). This interstate pact reveals how European geopolitics affect Kurdish asylum seekers.

Kurdish refugees in Malmö and Salzburg indicated that authorities view their integration into host cultures as troublesome due to concerns that their legal status may stimulate political activism, endangering the state-to-state relationship with Turkey. The majority of Kurdish asylum seekers believe that authorities implicitly force them to choose between voluntary departure and returning home. This invisibilizes refugees’ concerns and diminishes their protection. The remark of Mêrxas, a Kurdish asylum seeker in Salzburg from Turkey, is insightful in terms of humanising these persons and comprehending the mental toll resulting from such severe restrictions. After four years without refugee rights in Austria, he considers returning to Turkey and serving three years in prison. He noted that his children in Turkey are also impacted by his asylum case because they cannot join him through family reunion. He blamed his protracted asylum case for most of his problems.Footnote2 Similarly, obstacles stemming from asylum procedures hamper Kurdish immigrants’ integration into new social situations since they lack recognition in receiving societies and are pushed to the periphery of host cities. These constraints put them in more precarious situations that affect their families back home (Wilmer Citation2018).

The second concern is Kurdish immigrants’ settlement and adaptation processes. These include obstacles with housing, employment, bureaucracy, and orientation in receiving societies. Authorities fail to recognise immigrants’ qualifications, education, training, and language skills. Kendal, a Kurdish refugee from Syria, remarked that the Swedish authorities complicate their lives by refusing them acceptable employment despite having the required qualifications and experience, as well as Swedish language abilities. Swedish authorities do not recognise immigrants’ foreign qualifications unless they are trained in Sweden.Footnote3 Failure to recognise refugees’ rupture with their social and geographical homelands creates social and structural barriers and prejudices that prevent immigrants from regulating their fundamental requirements as national citizens. Immigrants in Salzburg claimed, for instance, that landlords do not conceal their bias against immigrants and thus refuse to rent their properties to them. Jiyan, a Syrian refugee, stated that he and his fellow refugees have significant housing challenges since Austrian landlords are unwilling to rent to them despite the availability of several apartments. He noted that these landlords distrust refugees since they assume that they receive social benefits and fail to pay their rent on their own. He complained about this approach and felt discriminated against when immigrants are denied renting appropriate flats due to their refugee status and landlords’ suspicion.Footnote4 To support their families and cover basic expenses, many asylum seekers in all cities reported working illegally because they lack legal papers and language abilities. Consequently, they are exposed to abuse and discrimination because they work longer hours for less than the minimum wage and have no legal rights against exploitation.

Concerns about immigrants’ assimilation and alienation are addressed in the third problem domain. Kurds are being pressured to renounce their linguistic, cultural, and moral values, which have formed their social relationships and cultural identity (Yadirgi Citation2017; Yeğen Citation2007). These assimilation programmes take various forms in exile, with authorities requiring refugees to relinquish their ethnicity, culture, language, and values since they are incompatible with those of the host culture (FitzGerald and Arar Citation2018; Algan et al. Citation2012). Many Kurdish immigrants claimed that authorities in Landshut, Salzburg, Bornholm, and Malmö encouraged their assimilation by demanding that they give up their traditional way of life and sever links with their Kurdish homeland, culture and identity. They claimed that not developing cultural, historical, ancestral, and societal values alienates them from their reality.Footnote5 The policies they escaped are so pervasive in their new countries of residence that they are essentially identical to the ones they fled.

The final concern is the continuous oppression and violence experienced by Kurds in Turkey, Iraq, and Syria as a result of authoritarian state policies (Eliassi Citation2021). Many Kurdish immigrants fled to Europe as refugees while remaining embroiled in homeland affairs. Murdem, a refugee, emphasised his predicament, noting that he does not distinguish between his life in Salzburg and Turkey's and Syria's restrictive policies towards his Kurdish compatriots. He left Turkey because he was not treated equally, yet he remains connected to his people and conflicts that are more significant than his life abroad. He references the indefinite hunger strike of his compatriots and Kurdish prisoners. He showed his estranged feelings by withdrawing from his normal social life.Footnote6 Thus, violence and oppressive political events in the homeland concern refugees, whose compatriots are regularly threatened with death and prison. These events worsen refugees’ predicament and mental states.

Typologies of self-governing formations of Kurdish immigrants

Based on common ideals, causes, affinities, and concerns, Kurdish immigrants build local and transnational networks, initiatives, committees, and people assemblies to identify their needs, make decisions, organise, and find solutions without government interference. Rezan, a Kurdish asylum seeker in Malmö, emphasised common values, ideologies, and concerns with other Kurdish immigrants. He and other co-nationals addressed their shared concerns regarding the asylum application processes, as well as economic and social restraints, via the social communities they create, driven by collective elements.Footnote7 Although Kurdish immigrants address shared components that lead to the formation of collective identities as the foundation of self-governing institutions, they may not place equal emphasis on the same elements that may play a major role in establishing a stronger feeling of belonging and collective identities only among some groups. For instance, many immigrants share ideological, homeland, and kinship characteristics simultaneously, while the relative importance of these elements can fluctuate to greater or lesser degrees. This inconsistency is not surprising, as identities are intersectional and not fixed (Yuval-Davis Citation2011). Like ideological and national movements, Kurdish kinship relations and tribes create alternative identities too (Belge Citation2011). These collective identities thus interact to generate autonomous spaces for self-governing formations and operations.

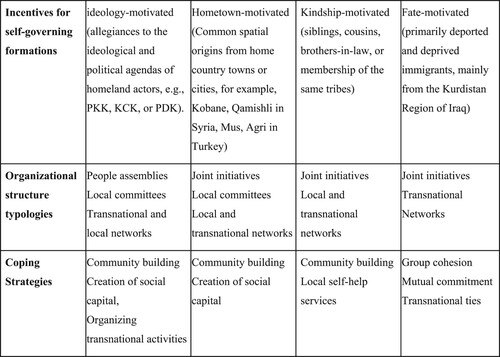

After my interactions and interviews with various categories of Kurdish immigrants, I identified four main features that push diverse Kurdish immigrants in the same cities to contribute to self-governing formations, self-organising practices, and group citizenship in autonomous spaces to rule their daily affairs and promote one another with economic, material, and mental support. These characteristics revolve around ideological allegiances to Kurdish political actors, shared origins from the same villages and towns, kinship relationships, and common concerns identified by refugees as their ‘fate’ (). These diverse models are influenced by numerous characteristics, yet they share similar autonomous, horizontal, and bottom-up structures in the form of self-organising assemblies, committees, joint initiatives, and non-hierarchical networks. These typologies of Kurdish immigrants’ self-government models are not confined to a particular city but regularly interact in all cities. However, contextual identities dictate the qualities of these formations.

The ideology-motivated self-governing model, seen primarily in Malmö and Salzburg but also in Southern France, is shaped by immigrants’ allegiances to the common ideological and political agendas of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), Kurdistan Democratic Party (PDK), Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), Democratic Union Party (PYD), or Kurdistan National Council (KNC), whereas the hometown-motivated model in Bornholm, Landshut, and Malmö arose as a result of the common spatial origins of the same Kurdish towns and cities. The kinship-motivated model in southern France, Malmo, and Landshut is influenced by ties between Kurdish tribes and extended families. Finally, the fate-motivated self-governing model in Bari and, to a lesser extent, in Salzburg is based on common concerns over the precarious situations of immigrants. The characteristics of each self-governing model serve as a driving force behind the construction of social communities, which are organised in an autonomous pattern without the control or interference of any governmental agencies or non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Therefore, immigrant self-governance formations are independent of official mediation and foreign non-state actors. Kurdish immigrants, as ordinary members of self-governing establishments, recognise their plights and demands and use diverse strategies to address them. In different cities, they adopt similar approaches to tackle asylum and integration practices, sociocultural interests, and homeland matters (Ife Citation2009; Pierre-Lous Citation2006). Collective communities are autonomous social spaces where problems are discussed and handled via shared responsibility, social interaction, and collective actions in Malmö/Salzburg, Bornholm/Landshut, and Southern France. They organise self-initiated committees in these autonomous spaces to provide mutual resources and services, such as housing and employment advice, as well as those geared towards socio-cultural demands (Darling Citation2017). In addition, self-governing formation bolsters group cohesion and solidarity in Bari, which are crucial to handle vulnerability, uncertainty, and survival, particularly when it comes to basic necessities like shelter and health care. I'll analyse each self-governance model's incentives, structural formations, and coping strategies below.

Ideology-motivated self-governing model

Inspired by shared ideologies, Kurdish immigrants, primarily from the Kurdish regions of Turkey and Syria, organise in social communities to form self-governing people assemblies, committees, and networks. Members of these segments, who are mostly located in Malmö, Nice, and Salzburg, are already embedded in politicised transnational networks with predetermined ideological agendas of actors in the Kurdish regions. According to Aref, a Kurdish asylum seeker from Turkey currently residing in Malmö, Kurdish immigrants retain their collective identities from the Kurdish region. They create this kind of self-governing formations and establish self-organized practices in line with the KCK's ideological model.Footnote8 They mostly adhere to the political and ideological principles of KCK-related objectives, such as ‘democratic confederalism,’ which was inspired by Abdullah Öcalan, the imprisoned leader of the PKK (Saeed Citation2016). Its fundamental formations include the people's assemblies, which are comprised of numerous committees employing a wide range of immigrant-serving strategies. These committees respond to the cultural and socioeconomic requirements of Kurdish immigrant families and individuals based on their expertise. Their offerings include Kurdish and host-language classes, national holiday and anniversary celebrations, and the promotion of peace and reconciliation amongst Kurdish families and businesses through conflict resolution mechanisms (Tas Citation2014; Jacobsen Citation2019). Aref described Kurdish cultural celebrations such as Newroz and International Workers’ Day on May 1st, emphasising that these celebrations foster connection and interaction among the Kurdish immigrants.Footnote9

The self-organized activities of these self-governing committees provide social capital to assist Kurdish immigrants in overcoming social isolation and coping with insecurity, uncertainty, and typical bureaucratic obstacles (Pupavac Citation2005). Their social capital plays a crucial role in supplying details about how Kurdish immigrants behave in their settings and acting as a forum for social and political interactions. Additionally, it helps dispersed Kurdish immigrants communicate and network while boosting their self-esteem. These organisations also encourage Kurdish immigrants to engage in transnational politics by holding demonstrations, seminars, and fund-raising for their homeland's compatriots (Ambrosini Citation2018). Kurdish immigrants view their homeland as crucial to their survival because it permeates all aspects of their social interactions and daily lives, serves as a source of shared values and collective identities, and forms the basis of both local and international solidarity (Jacobsen Citation2019; Cronin Citation2008; Griffiths Citation2002). This self-governing model is regularly entrenched in homeland financial and political affairs. They collect donations for their compatriots back home and raise public awareness of the plight of the Kurds in their home countries through contentious actions such as protests and rallies. Along with political decision-makers, they seek to influence representatives of civil society organisations, including pressure groups and trade unions. These establishments are constantly organising political workshops, cultural events, and seminars, as well as street protests. In this way, they urge Kurdish immigrants to converge at these events and express solidarity with their compatriots for their political goals in Kurdistan.

Hometown-motivated self-governing model

The hometown-motivated self-governing model is informed by the common spatial origins of Kurdish immigrants from towns, cities, and villages, notably those from Qamishli and Kobane in Northern Syria. These segments’ formations are composed of committees and initiatives, and they are well established in Bornholm, Landshut, and Malmö, but they have also been noticed in other cities. Many immigrants find solace and solidarity in developing a sense of community around their shared township roots. Serhildan from Qamishli remarked that he was surrounded by Arabs upon his arrival in Bornholm and longed to meet Kurdish immigrants. When several Kurds from his hometown of Qamishli arrived in Bornholm, he felt relieved and less alone. They then worked together to organise a social community where they interact with one another every day. They visit each other at least once a week, each time at someone else's house with their spouses and children. During these meetings, they talk about their worries and concerns with orientation and settlement, and they help each other figure out how to deal with the problems they face every day. During their visits, they discuss homeland politics and organise the collection and distribution of donations to impoverished individuals in their villages in Rojava.Footnote10

Kurdish immigrants in Bornholm and Landshut adopt identical strategies by transforming their spatially rooted relationships into social community, an autonomous social space where they form joint initiatives and committees involved in collective actions to nurture solutions to their local matters such as housing, resident permits, welfare services, employment, education, and paperwork. For instance, during the settlement and integration phases, these formations aid in satisfying the social needs of newly arrived families by welcoming them and guiding them to the appropriate agencies. Furthermore, these initiatives offer cultural and social support to single male immigrants who marry Kurdish women from Rojava (in north-eastern Syria). They assist immigrant men in dealing with the paperwork of their future spouses, who intend to move to Germany to join their male partners. Mehmoud from Qamisli described their joint efforts to connect Kurdish couples. He has received a few requests for help from immigrants who are Kurdish and have been cut off from their families in Syria. Mahmoud stated that he contacted various Kurdish immigrants in Landshut and Munich to assist those immigrants who were seeking financial assistance or loans to organise their weddings. Their initiatives arrange social events and bring immigrants together to raise wedding funds.Footnote11 The development of autonomous social spaces through community building also aids Kurdish families in resisting language-related assimilation and promoting mutual cultural services. For example, Kurdish parents encourage their children to play together and speak Kurdish. Finally, these collaborative initiatives link newly arrived forced immigrants with established immigrants in order to obtain translation and support services to help them overcome bureaucratic barriers. Thus, the self-governing model enables advisory services in areas where governments fail to address cultural and language barriers or provide legal, social, and psychological information. The self-governing formation helps to eliminate structural barriers that obstruct refugees’ integration and well-being while also enhancing their living conditions, cultural identity, and language skills.

Kinship-motivated self-governing model

The kinship-motivated self-governing model in southern France maintains pre-determined ties to Kurdish tribes and extended families, mainly from Van and Mus in Turkey's Kurdish region. These links can be depicted within the framework of the Ibn Khaldounian concept Assabiyyah, which refers to social groups such as families and tribes that engage in collective actions as a result of the development of ‘ a strong sense of group feeling and internal solidarity’ or ‘kinship spirit’ (Khayati Citation2008; Spickard Citation2001). As a result of kinship links, forced Kurdish immigrants develop feelings of belonging akin to collective identities, which play a significant role in the formation of committees and cooperative initiatives inside enclosed kinship communities (Decimo and Gribaldo Citation2017). Using these self-governing entities, immigrant networks respond to political, social, and structural obstacles posed by their pending asylum claims and integration processes. Apo, a Kurdish refugee in Antipas, stressed the importance of family ties, which urge individuals to serve one another. He claimed that Kurdish immigrants cannot simply leave their hometowns of Mus and Van to immigrate and find connection in the absence of prior family bonds and ties. He added that every immigrant has family and kin links, which play an important role in receiving newly arrived asylum seekers, displaying internal solidarity, and managing their livelihoods. This internal solidarity is unwavering, regardless of their legal status.Footnote12 Many immigrants stressed the importance of Kurdish family structures and culture in their sense of belonging to kinship networks that predate the nation-state system. These robust kinship ties form a self-governing paradigm that strengthens connectedness and mutual commitments (Griffiths Citation2002).

The kinship-motivated self-governing approach is built on immigrants’ collective initiatives to address political and structural barriers faced by their relatives. These formations are involved in the welcoming, accommodation, and employment of fellow immigrants, supplying newly-arrived asylum seekers with address information, aiding them in registering for asylum claims with the French Refugee Protection Agency (OFPRA), and assisting them in opening bank accounts. Pre-established immigrants running local businesses such as kebab shops or construction firms generate employment for undocumented immigrants and rent apartments in their names to prevent their homelessness. Serhat from Turkey described these actions, highlighting how they assist recently arrived immigrants and handle their paperwork. They accompany them to their appointments and arrange for acquaintances who speak French to volunteer to translate for them. Serhat asserted that there are numerous shared apartments in his name for recently arrived immigrants who lack legal documents in their immigrant community. He claimed that aside from certain papers bearing their names and pictures, French authorities do not provide asylum seekers with essential resources like housing or other welfare services. These government programmes do not help immigrants tackle their issues; instead, they must rely on their own resources and develop their own network of self-help services.Footnote13 However, employment and housing possibilities still continue to exploit newly-arriving immigrants, who are provided with inadequate housing and low pay. Many immigrants who arrived in Southern France told me they were forced to put up with these circumstances in order to maintain themselves and their families in the homeland. They are subjected to these discriminatory conditions because they feel they will be unable to obtain employment in non-Kurdish and French businesses due to a lack of documents and French language abilities. Nevertheless, these internal solidarity patterns that expose long-term immigrants to risk and exploit recently arrived immigrants reveal that immigrants engage in self-governing behaviours by offering their own support services to manage their lives in the absence of authorities.

Fate-motivated self-governing model

The subjects of the fate-motivated self-governing model in Beri are primarily immigrants from the Kurdistan Region of Iraq who are ‘impoverished’ and ‘abandoned.’ They have no ties to a particular political party, a town network or a tribe. They were detained and fingerprinted while travelling through Italy to countries in northern and western Europe. They became de-jure asylum seekers as soon as their forced fingerprints were obtained. After seeking asylum in North and West Europe, they were deported to Italy under the Dublin Regulation.Footnote14 Like refugees in Greece, these immigrants rarely consider Italy their permanent home, preferring to live in a ‘liminal zone,’ taking each day as it comes (Arvanitis, Yelland, and Kiprianos Citation2019). This group of Kurdish immigrants shares a collective crisis on the edge of Italian society, including precarity, impoverishment, abandonment, and marginalisation in Bari, as a result of a lack of welfare services, limited living prospects, and unsuccessful integration into Italian society. Most of these Kurdish immigrants are frequently compelled to travel and work illegally in Western Europe in order to escape the appalling conditions in Italy. There, they live clandestinely without access to social security or other government services. However, when they are caught in other EU member states, they are returned to Italy. They therefore perceive their predicament as grave and consider it to be their fate. They are powerless to change it, but they can lessen it by connecting with immigrants in other countries and fostering mutual solidarity.

This group of immigrants empowers itself through self-reliance, self-management, mutual commitment, and group cohesion based on their shared concerns. Bawer remarked that refugees’ mutual devotion helps him tackle challenging circumstances in the absence of government and diaspora organisations. He relies on fellow immigrants who share his fate to help him and each other meet their basic needs. They share modest apartments, registration addresses, and essential resources.Footnote15 To witness their living conditions, many refugees invited me to their apartments, which were without legal documentation and in poor condition, yet they paid each between 150 and 200 euros every month in rent. However, transnational networks and activities help solve their dilemmas. Xizan stated that he and his countrymen create their own services for basic needs. He highlighted that they travel to Western Europe and work illegally for a few months before squandering their funds in Italy.Footnote16 Due to poor integration prospects, many immigrants are granted asylum in Italy but work illegally in other European countries. Immigrants must travel to Bari to renew their passports and resident permits. While doing so, they donate to Bari's destitute immigrants for housing and living expenses. Transnational solidarity from below, via donations from fellow immigrants, helps immigrants promote self-organisation and self-sufficiency (Smith and Guarnizo Citation1998). Thus, transnational network linkages empower Bari immigrants.

Conclusion

In this article, I examined the relationship between collective identities, community development, and autonomous social spaces to explain the process of self-governance of Kurdish immigrants on the periphery of European societies. My findings revealed that Kurdish immigrants, including refugees and asylum seekers, construct multiple models of self-governance resulting from a variety of collective identities. They adopt viable coping strategies in community spaces where people autonomously negotiate their relationships, interact, and nurture solutions to their multiple challenges in settlement cities. The research illustrated that Kurdish immigrant self-governance models are not always political, although some segments are involved in political actions. They are the outcome of immigrant context, capacity and a reaction to the institutional, social, and cultural constraints that immigrants confront on a daily basis (Papadopoulos and Tsianos Citation2013). In other words, all models, including the ideologically driven groups of Kurdish immigrants, aim to improve immigrants’ situations and fill the void left by the government, not to dismantle neoliberal orders and go against the government in their settlement cities.

Immigrant identities and structural formations constitute the foundation of self-governance in their communities, which allows them to satisfy the needs of immigrants without government interference or control. In other words, as compatriots, countrymen and women, relatives, partners, and neighbours, they negotiate their group citizenship and engage in economic, cultural, and social practices and collective actions outside of national laws and state regulations. The establishment and operation of such self-governing bodies are linked to specific strategies through which immigrants express themselves and their realities, resulting in empowerment and enhanced collective agency (Shinozaki Citation2015; Mainwaring Citation2016). They assert who they are, why they became forced immigrants, and how they cope with their circumstances. They become subjects and objects of self-governing cultural, historical, and social orders. Their narratives imply a ‘site of epistemic orientation’ that embodies their reality in relation to history, social lifestyle, and marginalisation due to Kurdish statelessness and non-European subjectivities (Eliassi Citation2021). However, additional empirical and comparative research is required to assess how statelessness affects the self-governance models of immigrant communities.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Fiona B. Adamson, Professor Maurizio Ambrosini, Dr. Christiane Fröhlich, Professor Lennart Olsson for their invaluable comments on the final draft of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

‘The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Dr. Veysi Dag. The data are not publicly available due to [restrictions e.g. their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants].’ The research participants are politically-persecuted refugees and asylum seekers whose asylum claims in host countries are still in process and whose family members still live in the Kurdish regions in Turkey, Syria and Iraq. The data are publicly not available in order to avoid endangering the research participants or their family members.

Research Ethics Panel (REP), SOAS University of London, on 26. June 2019.

Approval number: the SOAS approval code: 107-vREP-(MAGYC)- 0619.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Veysi Dag

Veysi Dag is a DFG research fellow at the Rothberg International School of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He is also an ISRF Associated Academic and a research associate at SOAS, University of London. Studies of migration and diaspora; governance, social movements, and transnationalism; comparative politics with a focus on refugee and migration policies in Europe; peace-building and conflict transformation; and regional policy analysis with a focus on Middle Eastern politics and the Kurdish-Turkish conflict are among his research interests. Dag was a visiting researcher at SOAS in 2014 and the International Migration Institute (IMI) of Oxford University in 2015. He holds a Ph.D. from the Free University of Berlin.

Notes

1 Focus group interview with a group of Kurdish asylum seekers conducted by the author in Malmö on May 3, 2019.

2 Interview with Merxas conducted by the author in Salzburg on May 22, 2019.

3 Interview with Kendal conducted by the author in Malmö on May 1, 2019.

4 Interview with Jiyan conducted by the author in Salzburg on May 21, 2019.

5 Interviews with groups of Kurdish refugees conducted by the author in Malmö on May 3, 2019, and in Landshut on May 14, 2019.

6 Interview with Murdem conducted by the author in Salzburg on May 23, 2019.

7 Interview with Rezan conducted by the author in Malmö on May 2, 2019.

8 Interview with Aref conducted by the author in Malmö on May 1, 2019.

9 Ibid.

10 Interview with Serhildan conducted by the author in Bornholm on May 4, 2019.

11 Interview with Mahmoud conducted by the author in Landshut on May 13, 2019.

12 Interview with Apo conducted by the author in Antipas on July 3, 2019.

13 Interview with Serhat conducted by the author in Antipas, July 3, 2019.

14 The Dublin Regulation clarifies the responsibility of EU member states for asylum seekers’ applications. The member state where asylum seekers first arrive must accept and decide on their asylum application. Asylum seekers are prohibited from claiming asylum in a second EU country. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02013R0604-20130629 (last accessed 14 February 2023).

15 Interview with Bawer conducted by the author in Bari on July 29, 2019.

16 Interview with Xizan conducted by the author in Bari on July 27, 2019.

References

- Algan, Y., A. Bisin, A. Manning, and T. Verdier. 2012. “Introduction: Perspectives on Cultural Integration of Immigrants.” In Cultural Integration of Immigrants in Europe, edited by Y. Algan, A. Bisin, A. Manning, and T. Verdier, 1–48. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ambrosini, M. 2018. Irregular Immigration in Southern Europe: Actors, Dynamics and Governance. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Arvanitis, E., J. N. Yelland, and P. Kiprianos. 2019. “Liminal Spaces of Temporary Dwellings: Transitioning to New Lives in Times of Crisis.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education 33 (1): 134–144. doi:10.1080/02568543.2018.1531451.

- Ashutosh, I., and A. Mountz. 2011. “Migration Management for the Benefit of Whom? Interrogating the Work of the International Organization for Migration.” Citizenship Studies 15 (01): 21–38. doi:10.1080/13621025.2011.534914.

- Ates, S. 2021. “The End of Kurdish Autonomy: The Destruction of the Kurdish Emirates in the Ottoman Empire.” In the Cambridge History of the Kurds, edited by H. Bozarslan, S. Gunes, and C. Yadirgi, 73–103. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne and New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- Bajalan, D. R. 2021. “The Kurdish Movement and the End of the Ottoman Empire.” In the Cambridge History of the Kurds, edited by H. Bozarslan, S. Gunes, and C. Yadirgi, 104–137. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne and New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- Belge, C. 2011. “State Building and the Limits of Legibility: Kinship Networks and Kurdish Resistance in Turkey.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 43: 95–114. doi:10.1017/S0020743810001212.

- Benson, G. O. 2019. “Refugee-Run Grassroots Organizations: Responsive Assistance Beyond the Constraints of US Resettlement Policy.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (2): 2124–2141. doi:10.1093/jrs/feaa010.

- Benson, O. G., I. Routte, A. P. P. Walker, M. Yoshihima, and A. Kelly. 2022. “Refugee-Led Organizations’ Crisis Response During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Canada's Journal on Refugees 38 (1): 63–77. doi:10.25071/1920-7336.40879.

- Betts, A. 2011. Global Migration Governance. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Betts, A., E. Easton-Calabria, and K. Pincock. 2021. “Localizing Public Health: Refugee-led Organizations as First and Last Responders in COVID-19.” World Development 139: 2–6. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105311.

- Chatterton, P. 2004. “Making Autonomous Geographies: Argentina’s Popular Uprising and the ‘Movimiento de Trabajadores Desocupados’ (Unemployed Workers Movement).” Geoforum 36 (5): 545–561. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2004.10.004.

- Cohen, A. P. 1985. Symbolic Construction of Community. Manchester: Ellis Horwood Limited.

- Cronin, S. 2008. Subaltern and Social Protest: History from Below in the Middle East and North Africa. London and New York: Routledge.

- Darling, J. 2017. “Forced Migration and the City: Irregularity, Informality, and the Politics of Presence.” Progress in Human Geography 41 (2): 178–198. doi:10.1177/0309132516629004.

- Decimo, F., and A. Gribaldo. 2017. Boundaries Within: Nation, Kinship and Identity Among Migrants and Minorities. Cham: Springer.

- Dinerstein, A. C. 2015. The Politics of Autonomy in Latin America. Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillian.

- Eliassi, B. 2021. Narratives of Statelessness and Political Otherness: Kurdish and Palestinian Experiences. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- FitzGerald, D. S., and R. Arar. 2018. “The Sociology of Refugee Migration.” Annual Review of Sociology 44: 387–406. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041204.

- Fontanari, E., and M. Ambrosini. 2018. “Into the Interstices: Everyday Practices of Refugees and Their Supporters in Europe’s Migration ‘Crisis’.” Sociology 52 (3): 587. doi:10.1177/0038038518759458.

- Frazer, E. 1999. The Problems of Communitarian Politics: Unity and Conflict. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gambetti, Z., and J. Jongerden. 2015. The Kurdish Issue in Turkey: A Spatial Perspective, 1–24. London and New York: Routledge.

- Gamlen, A. 2014. “Diaspora Institutions and Diaspora Governance.” International Migration Review 48 (S1): 180–217. doi:10.1111/imre.12136.

- Gateley, D. E. 2014. “Becoming Actors of their Lives: A Relational Autonomy Approach to Employment and Education Choices of Refugee Young People in London, UK.” Social Work and Society 12 (2): 1–14.

- Griffiths, J. D. 2002. Somali and Kurdish Refugees in London: New Identities in the Diaspora. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Guarnizo, L. E., and M. P. Smith. 1998. “The Locations of Transnationalism.” In Transnational from Below, edited by M. P. Smith and L. E. Guarnizo, 3–31. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Gündogan, Z. A. 2015. “Space, State-Making and Contentious Kurdish Politics in the East of Turkey: The Case of Eastern Meetings, 1967.” In The Kurdish Issue in Turkey: A Spatial Perspective, edited by Z. Gambetti, and J. Jongerden, 27–62. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hanafi, S., and T. Long. 2010. “Governance, Governmentalities, and the State of Exception in the Palestinian Refugee Camps of Lebanon.” Journal of Refugee Studies 23 (2): 134–139. doi:10.1093/jrs/feq014.

- Ife, J. 2009. Human Rights from Below: Achieving Rights Through Community Development. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo: Cambridge University Press.

- Izady, R. M. 1992. A Concise Handbook: The Kurds. New York and London: Routledge.

- Jacobsen, K. 2019. “Durable Solutions and the Political Action of Refugees.” In Refugees’ Roles in Resolving Displacement and Building Peace: Beyond Beneficiaries, edited by M. Bradley, J. Milner, and B. Peruniak, 23–38. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Joensen, T., and I. Taylor. 2021. Small States and the European Migrant Crisis: Politics of Governance. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jong, S. D., and I. Ataç. 2017. “Demand and Deliver: Refugee Support Organisations in Austria.” Social Inclusion 5 (3): 28–37. doi:10.17645/si.v5i3.1003.

- Kassa, D. G. 2019. Refugee Spaces and Urban Citizenship in Nairobi: Africa’s Sanctuary City. Lanham, Boulder, New York and London: Lexington Books.

- Khayati, K. 2008. “From Victim Diaspora to Transborder Citizenship?: Diaspora Formation and Transnational Relations among Kurds in France and Sweden.” PhD. thesis. Linköping.

- Klein, J. 2011. The Margin of Empire: Kurdish Militias in the Ottoman Tribal Zone. Stanford and California: Stanford university press.

- Krause, U. 2018. “Protection, Victimisation, Agency? Gender-Sensitive Perspectives on Present-day Refugee Camps.” Zeitgeschichte 45 (4): 483–506. doi:10.14220/zsch.2018.45.4.483.

- Küçükkele, M. 2022. “Exception Beyond the Sovereign State: Makhmour Refugee Camp Between Statism and Autonomy.” Political Geography 95: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102572.

- Leezenberg, M. 2021. “Religion in Kurdistan.” In The Cambridge History of the Kurds, edited by H. Bozarslan, S. Gunes, and C. Yadirgi, 477–505. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne and New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford and Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Mainwaring, C. 2016. “Migrant Agency: Negotiating Borders and Migration Controls.” Migration Studies 4 (3): 239–308. doi:10.1093/migration/mnw013.

- McConnachie, K. 2014. Governing Refugees: Justice, Order and Legal Pluralism. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

- McDowall, D. 2007. A Modern History of the Kurds. London and New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Mencütek, Z. 2019. Refugee Governance, State and Politics in the Middle East. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

- Milne, R., H. Foy, and L. Pitel. 2022. “Finland and Sweden hold talks with Turkey to push Nato bid.” Financial Times. (online). Accessed February 5, 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/957b7696-9079-452a-809f-9c6fecc351dd. (Created 30 August 2022).

- Montaser, M. S. 2019. “Investigating Self–settled Syrian Refugees’ Agency and Informality in Southern Cities Greater Cairo: A Case Study.” Review of Economics and Political Science. Accessed February 5, 2023. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108REPS-10-2019-0137/full/html.

- Morsut, C., and B. Ivar-Kruke. 2018. “Crisis Governance of the Refugee and Migrant Influx into Europe in 2015: A Tale of Disintegration.” Journal of European Integration 40 (2): 145–159. doi:10.1080/07036337.2017.1404055.

- Olson, R. 1991. “Five Stages of Kurdish Nationalism: 1880–1980.” Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs Journal 12 (2): 391–409. doi:10.1080/02666959108716214.

- Özok-Gündoğan, N. 2022. The Kurdish Nobility in the Ottoman Empire: Loyalty, Autonomy and Privilege. Edinburg: Edinburgh University Press.

- Papadopoulos, D., and V. S. Tsianos. 2013. “After Citizenship: Autonomy of Migration.” Citizenship Studies 17/2: 178–196. doi:10.1080/13621025.2013.780736.

- Pascucci, E. 2017. “Community Infrastructures: Shelter, Self-Reliance and Polymorphic Borders in Urban Refugee Governance.” Territory, Politics, Governance 5 (3): 332–345. doi:10.1080/21622671.2017.1297252.

- Pickerill, J., and P. Chatterton. 2006. “Notes Towards Autonomous Geographies: Creation, Resistance and Self-Management as Survival Tactics.” Progress in Human Geography 30 (6): 730–746. doi:10.1177/0309132506071516.

- Picozza, F. 2021. The Coloniality of Asylum: Mobility, Autonomy and Solidarity in the Wake of Europe’s Refugee Crisis. Lanham, Boulder, New York and London: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Pierre-Lous, F. 2006. Haitians in New York City: Transnationalism and Hometown Associations. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Pincock, K., A. Betts, and E. Easton-Calabria. 2020. “The Rhetoric and Reality of Localisation: Refugee-Led Organisations in Humanitarian Governance.” The Journal of Development Studies 57 (5): 1–16. doi:10.1080/00220388.2020.1802010.

- Pries, L. 2019. “Introduction: Civil Society and Volunteering in the So-Called Refugee Crisis of 2015- Ambiguities and Structural Tensions.” In Refugee Protection and Civil Society in Europe, edited by M. Feischmidt, L. Pries, and C. Cantat, 1–24. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pupavac, V. 2005. “Human Security and the Rise of Global Therapeutic Governance.” Conflict, Security and Development 5 (2): 161–181. doi:10.1080/14678800500170076.

- Reichert, A. S. 2014. “Self-Governance in Contested Territory: Legitimate Agency and the Value of Local Knowledge in Qalandia.” St Antony’s International Review 10 (1): 64–81.

- Saeed, S. 2016. Kurdish Politics in Turkey: From the PKK to the KCK. New York and London: Routledge.

- Sayigh, R. 2011. “Palestinian Camp Refugee Identifications: A New Look at the ‘Local’.” In Palestinian Refugees Identity, Space and Place in the Levant, edited by A. Knudsen, and S. Hanafi, 50–64. London and New York: Routledge.

- Shinozaki, K. 2015. Migrant Citizenship from Below Family, Domestic Work, and Social Activism in Irregular Migration. New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Soleimani, K. 2021. “Religious Narrations of the Kurdish Nation during the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries.” In the Cambridge History of the Kurds, edited by H. Bozarslan, S. Gunes, and C. Yadirgi, 138–165. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne and New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- Spickard, J. 2001. “Tribes and Cities: Towards an Islamic Sociology of Religion.” Social Compass 48 (1): 103–116. doi:10.1177/003776801048001009.

- Tas, L. 2014. Legal Pluralism in Action: Dispute Resolution and the Kurdish Peace Committee. Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate.

- Tejel, J. 2009. Syria’s Kurds: History, Politics and Society. London and New York: Routledge.

- Tracy, S. J. 2013. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact. Hoboken and Medford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Van-Bruinessen, M. 1992. Agha, Shaikh and State: The Social and Political Structures of Kurdistan. London and New Jersey: Zed Books Ltd.

- Wilmer, S. E. 2018. Performing Statelessness in Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Yadirgi, V. 2017. The Political Economy of the Kurds of Turkey: From the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne and Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- Yeğen, M. 2007. “Turkish Nationalism and the Kurdish Question.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (1): 119–151. doi:10.1080/01419870601006603.

- Yeğen, M. 2021. “Kurdish Nationalism in Turkey, 1898–2018.” In the Cambridge History of the Kurds, edited by H. Bozarslan, S. Gunes, and C. Yadirgi, 311–332. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne and New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2011. “Beyond the Recognition and Re-Distribution Dichotomy: Intersectionality and Stratification.” In Framing Intersectionality: Debates on a Multi-Faceted Concept in Gender Studies, edited by H. Lutz, M. T. H. Vivar, and L. Supik, 155–170. Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate.