ABSTRACT

Zimbabweans in the United Kingdom (UK) are currently a ‘silent subset’ of the broader migrant population, warranting further investigation into their experiences once settled in the UK. This study explored Zimbabwean migrant parents’ experiences of bearing and raising children in the UK and how they sustain their children’s health and wellbeing. The Silences Framework (TSF) offers a lens through which the Zimbabwean parents’ experiences are made visible in this study. Hermeneutic phenomenology was employed as a research methodology from van Manen's perspective and data was collected through in-depth interviews with 10 Zimbabwean parents settled in South Yorkshire, UK. Findings from this study show that parenting experiences in the UK are largely influenced by cultural background, religious beliefs and how the parents were raised. Parenting in a new culture requires parents to rely on an interdependent system of support. There is concern about the children's sense of belonging in the UK. Research findings help to increase knowledge on the Zimbabwean diaspora, add insight in the everyday life of migrant families and therefore influence policies, practices and future research. While some findings are specific to the Zimbabwean diaspora, others are concerns that migrant families have irrespective of place of origin.

Introduction

Child-rearing for Black families in the UK exists in a framework that encompasses British heritage and own cultural background; and this involves parents operating between two often contradicting cultures (Ochieng and Hylton Citation2010). The UK is increasingly diverse and this presents a varied context of experiences and different constructions of service systems which can lead to misunderstandings of appropriate actions to sustain children's health and wellbeing. Five percent of migrants granted settlement in the UK in 2015 were Zimbabweans (Migration Observatory Citation2017). There are several notable waves of migration from Zimbabwe, driven by push factors such as political instability, low wages and high unemployment rates (Tevera and Zinyama Citation2002); and pull factors such as the need for workforce in some UK sectors (Moriarty et al. Citation2008). Migration of the Zimbabwean population may suggest the intention to capitalise on the perceived supportive systems for family welfare. With most of the migrants being of reproductive ages, many children are born to migrant parents in the UK everyday (United Nations Population Fund Citation2019). Parenting experiences is thus a concerning theme in migration studies.

Kanchense (Citation2006) points out that the patriarchal values in family structure and some aspects of the Zimbabwean culture position women as primary caregivers of children. Thus, the notion of men being the breadwinner is still prevalent in most of some families today. Post-Independent Zimbabwe features transformed family institutions that are more nuclear such that the elite can employ a domestic helper, thus building new social and cultural scripts which reflect class differences (Gaidzanwa Citation2003). A recent review of literature shows that migrant parents might find parenting isolating because of loss of support from the extended family (Machaka et al. Citation2021). Most African family institutions are not only made up of biological connections but also include non-biological relations, extended family and kinship networks who function within a collective cultural space in supporting each other to raise children (Mugadza et al. Citation2019; Oheneba-Sakyi and Takyi Citation2006). The extended family is an important part in the Zimbabwean context which features responsibilities for those within it, such as ensuring family security.

A review by Mugadza et al. (Citation2019) based on Australian studies noted a rise in notifications to child protection services regarding suspected abuse and neglect by families from migrant backgrounds. This might indicate how the families are disempowered in navigating the socio-political environment. This study reveals that parents were cautious of child protection laws in the UK. Raffaetà (Citation2016) recognises the family as a site for negotiation between the role of parents and that of the state.

The way that society views and treats children especially as widely expressed in the media is of concern for most migrant parents (Manase Citation2013). Such views which result in marginalisation or racism against the participants affect their feelings of belonging or (un)belonging. However, there is some evidence that migrants are affected differently based on factors such as legal status or economic resources in the destination country (Powell and Rishbeth Citation2012). The differences and subjectivity in the context of migrant parents’ experiences may have an impact on their parenting journey. Previous migrant-related research has considered Black families as a homogeneous group not explaining differences in experiences according to ethnicities (Ochieng and Hylton Citation2010). It is possible that literature is more skewed towards professional interests and not to priority areas for the Black community. Silences are embedded in multiple factors; hence this study uses this lens to understand Zimbabwean migrants’ experiences.

Aim of the study

The aim of this research which I conducted as part of my PhD was to explore the Zimbabwean migrant parents’ experiences of bearing and raising children in the UK and their perspectives of how they sustain their children’s health and wellbeing. Ethical clearance to undertake this study was obtained from the University which I was affiliated with (ER6378305).

The specific questions of the research were:

What is Zimbabwean migrant parents’ experience of bearing and raising children in the UK?

How do Zimbabwean parents sustain their children’s health and wellbeing?

The silences framework

The study employed ‘The Silences framework’ (TSF) (Serrant-Green Citation2011) as the theoretical underpinning to guide this study from formulation of the research question to the outputs, following through four stages. The concept of ‘Screaming Silences’ from which TSF was derived was developed to reflect what was left unsaid (missing theme) by study participants from a study exploring ethnicity and sexual health decision-making (Serrant-Green Citation2004). ‘Screaming Silences’ are constructed by a listener (experiencing person or researcher) regarding their experiences and encompasses the personal and social context where the experience occurs. The ‘Screaming’ feature reflects the impact an experience has on the listener (screams out) while the ‘silences’ aspect refers to how these ‘screams’ which appear obvious to the experiencing person are not often widely shared in the society, thus they affect them in silence. The framework’s usefulness continues to be proved and enhanced in other contexts as exemplified by several completed studies (Nyashanu Citation2017; Eshareturi et al. Citation2015; Rossetto et al. Citation2018; Janes, Sque, and Serranto Citation2018). This is the first time that TSF was adopted to parenting studies in the migrant population.

‘The Screaming Silences’ conceptual approach is underpinned by aspects of feminism, criticalist and ethnicity-based approaches. These approaches accept that human beings in a particular context at a particular time point construct their reality in a social world (Gray Citation2018; Serrant-Green Citation2011). TSF recognises the central importance of individual or group interpretations of experiences in the construction of knowledge (Serrant-Green Citation2011). This enables voices embedded in subjective experiences which are distanced from dominant discourses, under researched or actively silenced to be brought to light (Serrant-Green Citation2011). This highlights the potential of the framework to be adapted in different research contexts on under researched issues (Davies Citation2015).

The current parenting discourse in the UK reveals the marginalised representation of Black people in research. The criticalist viewpoints maintained in TSF resonates with this study as they centralise personal experiences as critical strategies in freeing research from rigid adherence to dominant discourses.

Methods

The phenomenological approach was chosen to explore the Zimbabwean migrant parents’ experiences because it is more systematic and rigorous; and it studies phenomena, of experiences or events, in the everyday world from the viewpoint of experiencing person (Becker Citation1992). Methodological approaches such as this seek to tap into racial/ethnic attributes or meanings that are seen to be rising from the racialised subjectivity and experiences of minoritised research participants (Gunaratnam Citation2003). Therefore, this represents a powerful space to capitalise on raw experiences and reveal issues pertinent to the Zimbabwean migrants which are under-researched. This study followed through van Manen’s school of thought. van Manen (Citation1990, 28) defines hermeneutic phenomenology as a certain theoretical philosophical framework in the ‘pursuit of knowledge’. This methodology is based on the philosophical belief that:

The essence of the phenomenon is uncovered by gathering text from those living it and then interpreting this text (van Manen Citation1990, 7).

Researcher identity

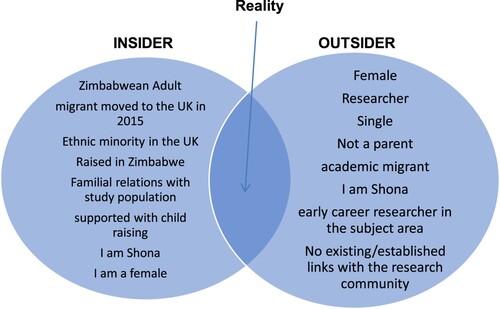

Confronting the researcher identity, as the vehicle through which silences are heard, identified and prioritised is a key element of TSF (Serrant-Green Citation2011). Many migration scholars hold the view that reflexivity should be an integral part of research, especially to challenge the nation and ethnicity-based epistemology that drives most of the migration research field (Dahinden Citation2016). As a migration researcher, my insider and outsider identities can function as a vital site for negotiating the reality in the research relationship (Borkert and De Tona Citation2006). The representation of research positionality as either insider or outsider only is not adequate to account for the diverse and complex experiences of researchers who don’t fit totally in either of the categories in relation to the participating population (Wiederhold Citation2015). Borkert and De Tona (Citation2006) have challenged this view because identity is ever shifting. Awareness of my positionality in negotiating the reality in the research relationship aided my attentiveness to issues of power, positionality and representation in designing the study. From this lens, I will reveal the multiple identities I bring to the research process (see ).

My identification as an insider within this study enabled me to have access to the research participants and have a level of trust and openness which could have been harder for the outsiders based on those identity markers. Confronting this controversial insider and outsider argument allowed me, from the outsider position to be cautious in the designing of the study and to be attentive to issues of power, positionality and representation while giving voice to the Zimbabwean migrant participants (Levy Citation2013).

Data collection

The sample for this study was Zimbabwean settled migrant parents (5 or more years in the UK) that were raised in Zimbabwe and started families in the UK, South Yorkshire. provides the demographic profile of the study participants. This study sampled for active parents, that is, including fathers who are usually excluded from the parenting discourse (Ochieng and Hylton Citation2010). Black fathers are deemed to be equal players in child-rearing decisions from within or outside the household (Ochieng and Hylton Citation2010). The silence of men as parents was addressed by purposive and snowball sampling. As established that the target population is minoritised, they were not highly visible from recruitment sites. Thus, snowball sampling widened the reach of inaccessible populations.

Table 1. General profile of participants.

This study used 10 In-depth interviews (including a visual element and field notes as part of the process) with five fathers and five mothers. TSF seeks to re-address power imbalances by recognising that, for silences to come out, power within the context of this study lies in the hands of the participants (Serrant-Green Citation2011). Participants were asked to spend time applying their creative way by drawing or gathering image/s which reflect their parenting experience prior to their interviews. This gave participants more time and a little less constraint in developing nuanced thoughts about their parenting experience (Johnson and Weller Citation2002). It was assumed that giving participants reflective time can help in stimulating a better conversation. The subject matter, parenting, is more personally meaningful and immediate for the participants; individual attention is crucial in the production of knowledge. Adler and Adler (Citation2005) highlighted that some participants may be resistant to open up about their experiences and such strategies can help in overcoming this. Interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim.

I wrote field notes to complement the interview recordings. These documented non-audio cues observed, my experiences or thoughts and general reflection of the process. Within hermeneutic phenomenology and TSF, reflexivity can possibly assist in and enrich data interpretations (Serrant-Green Citation2011; van Manen Citation1997). These notes helped to contextualise the interviews and highlighted the active parenting which I observed during the interviews. For example, the choice by participants to schedule the interview in between their seemingly busy schedules of managing work and childcare.

Data analysis

I engaged third party transcribers; this practice is advocated by Wilson (Citation2010) for allowing the researcher time to focus on other areas of the research as it is a time-consuming process. Each written transcript was read several times while listening to the corresponding audio tape to ensure accuracy of the transcribed tape and to further immerse myself in the data.

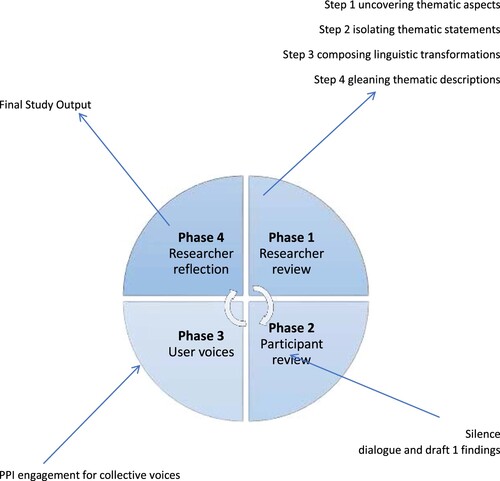

The analysis approach integrated four phases of TSF cyclic analysis (Serrant-Green Citation2011) and the thematic analysis process by van Manen (Minichiello et al. Citation1995). The process of analysis in TSF occurs as a cycle that follows through 4 phases until the inherent silences are revealed. Consistent with hermeneutic phenomenology, understanding of the parents’ experiences occur through a fusion of the pre- understandings of the research process, the interpretive framework and the sources of information (Laverty Citation2003). The analysis process is underpinned by the hermeneutic circle, which entails the process of moving back and forth between the parts and the whole in the process of understanding meaning and the development of a better interpretation (Laverty Citation2003).

As per , Phase one of the analysis represents the initial analysis of the data collected with reference to the research question by following through thematic analysis steps by van Manen (Minichiello et al. Citation1995). Phase two was the review of initial study findings by the participants drawn from phase one. This phase was developed to guarantee active user viewpoints in the research process and output; and not to further silence the marginalised participant's voices (Serrant-Green Citation2011). This aids in creating a dialogue to identify themes or aspects of themes that the researcher might have missed and in checking the validity of the conclusions from the ‘silenced’ participants’ perspective (Serrant-Green Citation2011). Undertaking this stage ‘silence dialogue’ was useful in approving, contesting or further contextualising the initial study themes. Feedback from the ‘silence dialogue’ fed into a more detailed secondary level analysis in producing draft one of the study findings. Phase three increases the scope of the user voices, therefore, I invited four individuals (See ) who share a cultural background with the participants and have an interest in issues related to the migration of Zimbabweans to comment on draft one of the findings. The collective voices were asked to reflect on the ‘silences’ they believe still exist or remain unchanged following this study. These reflections were useful in revising draft one findings to produce draft two findings.

Table 2. Profiles of four collective voices.

Phase four represents my final critical reflection in preparing the final study outputs. Moving between different levels of analysis improves the analysis and reflects the process of continually moving between the smaller and larger units of meaning. Consideration of the four lifeworld existentials by van Manen (Citation1997) (Lived space, lived time, lived body and lived other- See ) in the presentation and discussion of study findings enabled a holistic understanding of lived experiences. It allowed for visualisation of wider aspects of the lived reality and the interaction of the lifeworlds; hence there are some interactions across some themes presented. Themes identified as the final study outputs include Shared Worlds, Parenting in The UK System, The Parenting Journey and This Is Our Home Now. The data analysis process was critically discussed with my academic supervisors to ensure the appropriateness of the process and confirmed that the results were derived from the data.

Table 3. Lifeworld existentials/themes representation.

Results

This study explored the Zimbabwean participants’ lived experiences as parents in the UK which provided a lens for understanding the layers that structure their experiences.

Theme one: shared worlds

This theme describes Zimbabwean parents’ experience of a shared world which allowed them to adjust in a seemingly unfamiliar culture, empowering them to have better experiences and give their children better opportunities. Generally, the parents felt that UK values were insufficient to raise children who can adjust in most spaces around the world. The findings show that the parents employed aspects from Zimbabwean values and UK values which enabled them to accept and reject aspects of culture which they regard as superior or inferior. Completely rejecting Zimbabwean values and the dichotomous application of two cultural values raised issues about belonging for their children. It is likely that their inhabiting of the Zimbabwean and UK cultural spaces influences issues of belonging.

I’m working on and facing on, trying to mix the two cultures together: some of the things I negotiate and some of the things I use the Zimbabwe culture and tell them what to do … .. (Mutsa, mother)

I think it helps into moulding them into being very humble, respectful kids, because at church that’s what they’re being taught, how to respect not only their parents but everyone. How to live with others in the community, how to present themselves as good people. (Tsitsi, mother)

The findings reveal that although better support exists among those raising children as couples, poor parenting teamwork reinforced perspectives of a patriarchal system that emphasises nurturing children as a woman's role (As in theme three). Sharing the parenting journey is an important part of this theme, although sharing creates tensions whereby some Zimbabwean fathers are still silenced from active parenting.

Theme two: parenting in the UK system

This theme relates to the parents’ lived experience within the UK system including assumptions they can make about what is happening, what is expected of them and their reaction in appropriate ways by adjusting to the system to feel connected.

Power balanced relations between Zimbabwean born parents and their UK born children are dependent on multiple factors including meaning and societal expectations. Negotiating power in parent–child relations is based on accepting, without objection of perceived aspects of UK or Western parenting. The parents described a process which involved peeling back of old patterns that were integral to their upbringing when negotiating power in interactions with their children.

We felt like the power was becoming powerless so … there was a bit of like evening, like almost an even ground; even your daughter you are negotiating. (Ranga, father)

Essentially as parents we need to make decisions wisely. Black kids have a label already and we have to work extra hard for that label not to stick. Mashift akawandisa(Working a lot of shifts) leaving kids here there and everywhere should be avoided. We need to be there to protect these children. [Healthy lifestyle Advisor (Father)]

… the differences with the systems. And I think here they’re more, because I think it’s a bit of not understanding us as immigrants as well, where we’re coming from and where we’re going. Maybe they see our systems, like maybe they are not as thorough or they lack scrutiny, or because of that difference it takes you to explain to the people here that OK where I’m coming from we do one, two, three … … .. (Zuva, mother)

I learnt to accept that in UK you can actually be disowned and hearing stories; you know I hear stories about people’s kids who have left home and they reported them to Social Services. (Ranga, father)

Another dimension of protecting children is around their fears about exposing their children to technological devices and social media. These worries come at a time when it is fairly popular for children of all ages to engage with digital devices and explore social media. The parents felt the need to protect children from a perceived dangerous internet environment. In most narratives, parents would only be comfortable with internet use when their children have a better sense of protecting themselves.

Theme three: the parenting journey

These findings suggested the influence of the past, present or anticipated experiences on the parenting journey. The actualisation of the past and future expectations is what shapes the present experience as revealed in the following subthemes.

Subtheme 1: cultural transmission in an ever-changing world

The diaspora provides space where internalised cultural and social scripts are challenged as the parents raise their children in spaces that are inhabited by others from diverse cultures, which raises tensions when issues of belonging are considered.

For the participants in this study, transmitting aspects of Zimbabwean culture is a dynamic process. Participants draw on elements of the Zimbabwean culture from memories of how they were raised. With the growing Zimbabwean diaspora, there is hope that the community should be more organised to collectively transmit cultural elements to UK-born children. Maintenance of vernacular language and traditional foods were some key elements that parents referred to, especially comparing themselves to some established diaspora communities (For instance, Pakistanis and Indians) who have managed to transmit these cultural elements to their children.

I’ve noticed [Noah] has got a friend of his who’s from Pakistan, they go to their own community centres there being taught their languages. They get so much to learn there about their culture. Whereas us, because we don’t have time, always working. (Tsitsi, mother)

The busy lifestyle in this country hustling for shifts to better ourselves and feed our folks back home leaves little time to mould our children's lives. [Online group pioneer (Mother)]

Subtheme 2: altering gender roles

A common theme across their different professions (sample was over-represented in the health sector) was that taking on a lot of shift work is problematic amongst Zimbabweans in the UK because of how it impacts the quality of family life. The findings also revealed how change in gender roles was initially met with resistance along the parenting journey. Traditional aspects of gender roles are deeply rooted in Zimbabwean society such that the participants’ perception of mothers’ and fathers’ roles prove hard to challenge due to how the parents were socialised. Some resistance remains especially amongst women due to low confidence in man's nurturing ability, conformity to idealised womanhood and the negative perceptions of the extended family on men's involvement.

On the negative culturally, because culture is culture and we cannot deny it, there are instances where maybe an in-law visits and finds your husband is busy doing chores that are traditionally stigmatised or linked to be done by women, they don’t take it very well. (Zuva, mother)

Some women think that they are better than men, and they think that men cannot be responsible of their kids as well. We are capable, especially when it comes to this country … We can do, this country, like in their minds and it’s, we are all equal. What men can do women can do … . (Paul, father)

I had to accept that as a male parent and as a father, I had to change nappies. So I had to change it to maybe bath my daughter when she was young, which is something I would never do in Zimbabwe. I think my sister, my dad has never … . given a bath to any of us when I was growing up … . (Ranga, father)

It was like a lot of changes that took place, of which some took it negatively, some took it positively. Because with some men they appreciated, like my son and his dad. Because they had that bonding … .. (Zuva, mother)

It was evident that upon migration, parents are involved in a process of reconstruction of gender roles as they are confronted with different family values and more mothers are also employed. I suggest that the diaspora provides space where internalised cultural and social scripts are challenged as the parents raise their children in spaces that are inhabited by others from diverse cultures which raises tensions when issues of belonging are considered.

Theme four: this is our home now

This theme described the UK as a place where the parents could envision as, and have made their home. The felt-parenting environment helped parents to adapt to parenting in the UK to make it their home. Their perceived sense of belonging in the UK is also based on how parents navigate education spaces. The findings provide important insights into the perceived value of a good education and what that looks like to the parents. Migrant life is characterised with seeking out the best schools based on the potential for children's success and religious values. The lived space is one which offers choice in educational institutions.

Other participants perceived success-driven opportunities available to children solidify the UK as a home for their families. The parents prioritise safeguarding their children's future. They provide important insights into their collective ambitions for children and inadvertently signal a challenge to attain high levels of success given the lived realities of migrant life explored in previous themes.

Of course obviously you are an immigrant, and then you’re coming here, you want the best for your kids. (Ayanda, mother)

Parenting in UK has actually made it acceptable for most parents including myself to live here. Maybe on a permanent base, because I can't go back and live somebody who is still young and kind of a career to look forward to. (Ranga, father)

But a year after that we had stayed here we managed to sort of integrate into the Zimbabwean community. … … when we got into that community it was a lot easier, because you could actually leave the kids with friends sometimes, or they could stay at somebody’s house that we knew from church, and we would also do the same for them … . (Tafara, father)

Furthermore, parents describe an environment that can be potentially unhealthy without the helpful advice, modelling, financial and other input of the parent. In this way, they can be effective parents at maintaining their children's health and wellbeing in the UK.

When it comes to nutrition it’s a partnership. It’s a multi-sectoral partnership. You cannot say my child is doing well nutritionally because I’m giving him a healthy diet. You also get help. Because what I might call a healthy diet culturally like I was saying I can be giving sadza sadza without knowing what a balanced diet is. (Zuva, mother)

Discussion and conclusions: key silences

This study explored Zimbabwean participants’ lived experiences as parents in the UK which provided a lens for understanding the layers that structure their experiences as presented in the preceding themes. The silences arising from this study reflect and/or further extend the existing research in the study of migrant parenting experiences. While some silences are generic to parenting, there are some important aspects that embody the Zimbabwean migrants’ life. The pull of the past and the future is strong in the experiences of the parents. Anthias (Citation2012) has challenged migration scholars to consider the contextual factors which shape cultural identities and experiences. Hall (Citation1997a) further argues that cultural identities are constructed via the nexus of the past and the present. The parents in this study find themselves raising children and living in a cultural context that has many differences to Zimbabwe, which they must negotiate. Therefore, to understand the parents’ reconstructions of their cultural identities, it is important to consider how aspects of their upbringing in Zimbabwe have shaped their identities.

Participants mourn the loss of aspects of their Zimbabwean life where they had the support of domestic helpers and extended family in raising their children. This was a central way that some of the participants managed to balance work and meet their cultural gendered expectations in family life. The participants tended to contrast their gendered identities in the UK with how gender and parenthood are conceptualised in Zimbabwe. Unlike in Zimbabwe where mothers were responsible for the household and child-rearing, the parents in this study share responsibilities. These gender-household relations that structure the process of settlement have also been documented as silence for migrant Somali families in Sweden (Wiklund et al. Citation2000). The involvement of men in child-rearing was viewed as problematic by some men and women in this study. Similarly, Degni, Pöntinen, and Mölsä (Citation2006) in a study with Somali parents raising their children in Finland also found that men's involvement was regarded as a disruption of socio-cultural borders. Other women in this study internalised motherhood as their main identity and some were resistant to men's involvement. In a study with women in Harare (Zimbabwe), Shaw (Citation2015) found that women centred their identity around motherhood and religion which impacted their being in the world, and they did not challenge cultural beliefs and norms. This study illustrates the intersection of gender, religion and culture in reinforcing traditional gender roles. Fathers’ involvement in child-rearing has transformed and redefined mothering in the diaspora. The silences of Zimbabwean men parenting experiences in the UK have been changed by their participation in this study.

Children of foreign-born parents play the role of guiding parents with aspects of the UK cultural space. They are better positioned for this role as they participate in mainstream culture through attending school (Roland Citation1996). At the same time, parents hope to be in a place to teach their children aspects of Zimbabwean cultural values, traditions and language. Migrant communities use language as a cultural boundary marker that reinforces their sense of belonging and as a vehicle to transmit other aspects of their cultures and traditions (Edwards and Temple Citation2007; Hall Citation1997b). Furthermore, to maintain transnational and extended family relationships, migrants teach their children their languages (Farr et al. Citation2018). Intermarriage has reduced the ability of some participants to teach their children the Shona language (Zimbabwe’s main native language). Consistent with the assimilation theory, race or ethnic boundaries can be porous in these circumstances where identification with any side of the boundary is not clear cut (Kesler and Schwartzman Citation2015). This, therefore, represents an issue that is not confined to the Zimbabwean diaspora only. The parents believed that transmitting aspects of cultural practices serves to create distance between them and other diverse groups in the UK. Particularly, the participants’ comparison to the Pakistani community who have visibly managed to transmit aspects of their culture to their children. Shona customs, however, give the responsibility to teach children cultural values to the mothers (Bourdillon, Pfigu, and Chinodya Citation2006; Mbakogu Citation2014). Considering that most migrant mothers are not confined in their households, there is need to rethink the process. Teaching children Zimbabwean cultural values, beliefs and practices remain a silence even for the participants as they find it a challenging task. The integration of Zimbabwean and UK cultural aspects is common in this study. Accepting their mixed alignment to two cultural spaces can facilitate the parents’ ability to fully engage in enjoyable experiences of raising children (Akhtar Citation1999). However, other parents wanted their children to embrace the Zimbabwean culture and thus reinforce the Zimbabwean identity only. The findings presented correspond with the internal-external dialect of identification coined by Jenkins (Citation1996) whereby the identity of children is negotiated based on how parents identify their children, how they self-identify and how others see them. The socialisation process is therefore a key silence.

Parents in this study try to cultivate an element of belonging based on religion. Some studies on the Zimbabwean diaspora echoed that membership to a religious group created a sense of belonging, serves their spiritual needs and connects them to other Zimbabweans (Biri Citation2015; Machoko Citation2013; Pasura Citation2014). Interacting with other Zimbabweans in religious spaces also helped the participants to fulfil their parenting responsibilities and gave children elements of belonging.

Parents in this study noticed how opportunities available to their children expanded once settled in the UK. However, the participants and their children experience the racism embedded in different systems, institutions and social environments. Barley (Citation2019) captured how children in a primary school context were aware of racial differences, and further highlighted how they are then socialised to have perspectives about people from different racial backgrounds which perpetuate inequalities. Understandably, parents in this study fear that their children will be subject to these inequalities. Brown (Citation1998) argues that schools have been passive in tackling racism and suggested adopting an anti-discriminatory approach. This view is also supported by Au (Citation2009) and Barley (Citation2019) who reveal that this advice has not been heeded. This exposes the silences related to belonging and (un)belonging for children born to Zimbabwean parents in school spaces.

Return migration came up in discussions where parents perceived a lack of belonging and the need to immerse their children in Zimbabwean culture. Akhtar (Citation1999) discussed the ‘migrant's fantasy’ of returning to the home country out of fear of having created a distance from the country and its cultural values or practices by attaching to the destination country. In cases where parents envisioned opportunities for children in the UK, their notions of home were tied to a better life for their children and their attachment to the UK. This confirms that mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion in the destination country, emotional attachments and feeling at home form the concept of belonging (Anthias Citation2001; Davis, Ghorashi, and Smets Citation2018; Yuval-Davis Citation2006).

Parents in this study struggled to exercise authority in disciplining their children as they viewed State policies enforced by the Social Services as mechanisms that serve to empower children while disempowering them. Tettey and Puplampu (Citation2006) note that the modes of discipline commonly used by Africans such as smacking can be criminalised. This induced fear for some parents in this study, however, other participants did not agree with instilling discipline through spanking. This reflects on how well they feel the system suits their approach to child-rearing. While the parents may experience the seemingly heavy policing as an issue that affects them particularly as immigrants; other groups in society are likely to also feel controlled and policed in this way. Raffaetà (Citation2016), in a review on migration and parenting in the USA and the UK, argued that parenting practices vary even within ethnic groups. Therefore, labelling African ways of discipline abusive homogenises diverse cultures and families. This further marginalises the African diaspora families who might feel that the destination country's practices are deemed the good standard (Raffaetà Citation2016). I suggest that the participants in this study wanted to reserve some forms of discipline to preserve their cultural values in a diasporic space.

This study exposes the silence that transnational responsibilities in the form of remitting money to Zimbabwe and stresses related to migrant life affect parents’ experiences (Merry, Pelaez, and Edwards Citation2017; Mugadza et al. Citation2019). Some participants in this study feel pressured to take on extra work hours to meet up their transnational responsibilities, which limits the time they spend with children. McGregor (Citation2007) highlighted the long hours and ‘double shifts’ (combining day and night shifts) that Zimbabwean carers and others in low paid unskilled jobs normalised. Notably, Zimbabwean migrants’ work ethic likely shifts as they get settled in the UK, acquire professional qualifications and find space in the labour market. It is mportant to note that, despite their skill levels before migration, migrants from new African diaspora's become concentrated in low skilled jobs where they are required to work according to shift patterns (McGregor Citation2007). The economic challenges in Zimbabwe, therefore, impact the family life in the UK. The transnational burdens could be a silence for other migrant groups who have connections to their birth countries.

The use of language is key to silencing minoritised participants. I unearthed this during the recruitment process where I was asked questions such as ‘Would this be in English?’; and before interviews where other participants would highlight statements like ‘my English is not so good’. Although I gave them the opportunity to be heard in any language comfortable for them, some participants even paused before saying a Shona phrase. It is important to note that the historical ties and robust education policy soon after Zimbabwe's independence enabled many Black Zimbabweans to be proficient in English (Ndlovu Citation2010). I suggest that my outside positioning as a researcher posing the research questions in the English language might have been a barrier in the research process. This study has not addressed this silence around interview language which likely further compounds some silences harboured by Zimbabwean migrants.

This study has added to the growing body of knowledge on the Zimbabwean diaspora in the UK. It enabled a fuller picture of the migration journey from Zimbabwe and aspects that embody migrant life to be revealed. Previous studies have focused on a broader group of migrants and homogenised Zimbabweans under African migrants. This study also adds to the growing body of knowledge on migrant families. Families are predominantly perceived as nuclear, however, the way that the participants define families is broad. They function effectively as extended families, therefore the definition of families for different contexts needs to be accounted for in families’ research. By adding insight into migrants’ origin culture, this study has shown the nature of Zimbabwean families which impacts their experiences.

The use of TSF in this study proves that it can be a valuable framework in migrant family studies. Its emphasis on contextualising has shown the different ways participants are marginalised and the silences inherent to their status. This made me aware of how omission from the study could further marginalise the participants. Thus, I have included fathers as they have a valuable contribution to the parenting discourse. Other groups that could have been omitted included asylum seekers and refugees; engaging with TSF brings this to light. The flexibility allowed by the TSF challenges and allows for migration researchers to be creative in ways to explore experiences. Further studies which take the role of extended family in the migration context is an important gap to address since this study. The pull of the past demonstrated in this study calls for better generation of knowledge of transnational resources, and how these can be optimised to inform services towards supporting migrant families. Social workers, healthcare workers amongst others working closely with migrant families may then be better equipped to promote protective factors, mobilise untapped resources and support migrant families in dealing with their day-to-day life experiences. I demonstrated that migrant parents are not passive to their experiences, as they actively negotiate and renegotiate aspects of their being in the world.

Acknowledgements

I owe special thanks to my supervisors Laura Serrant, Ruth Barley, Margaret Dunham and Penny Furness for all their advice and critical discussions through this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Adler, P. A., and P. Adler. 2005. “The Reluctant Respondent.” In Inside Interviewing: New Lenses, new Concerns, edited by J. A. Holstein, and J. F. Gubrium, 515–536. London: Sage.

- Akhtar, S. 1999. Immigration and Identity: Turmoil, Treatment, and Transformation. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Anthias, F. A. 2001. “New Hybridities, Old Concepts: The Limits of “Culture”.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 24 (4): 619–641. doi:10.1080/01419870120049815

- Anthias, F. A. 2012. “Transnational Mobilities, Migration Research and Intersectionality.” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 2 (2): 102–110. doi:10.2478/v10202-011-0032-y

- Au, W. 2009. Rethinking Multicultural Education: Teaching for Racial and Cultural Justice. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Rethinking Schools.

- Barley, R. 2019. “Exploring Young Children’s Gendered Discourses About Skin Colour.” Ethnography and Education 14 (4): 465–481. doi:10.1080/17457823.2018.1485112

- Becker, C. S. 1992. Living and Relating: An Introduction to Phenomenology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- Biri, K. 2015. African Pentecostalism, the Bible, and Cultural Resilience: The Case of Zimbabwe Assemblies of God Africa. Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press.

- Bloch, A. 2008. “Zimbabweans in Britain: Transnational Activities and Capabilities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34 (2): 287–305. doi:10.1080/13691830701823822

- Borkert, M., and C. De Tona. 2006. Stories of HERMES: An Analysis of the Issues Faced by Young European Researchers in Migration and Ethnic Studies. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin. doi:10.17169/fqs-7.3.133

- Bourdillon, M., T. Pfigu, and J. Chinodya. 2006. Child Domestic Workers in Zimbabwe. Harare: Weaver Press.

- Brown, B. 1998. Unlearning Discrimination in the Early Years. Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books Limited.

- Chikwira, L. 2021. “Contested Narratives of Belonging: Zimbabwean Women Migrants in Britain.” Women's Studies International Forum 87: 102481. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2021.102481

- Chinouya, M., and E. O'Keefe. 2006. “Zimbabwean Cultural Traditions in England: Ubuntu Hunhu as a Human Rights Tool.” Diversity & Equality in Health and Care 3 (2): 89–98.

- Chogugudza, C. 2018. “Transferring Knowledge and Skills Across International Frontiers: The Experiences of Overseas Zimbabwean Social Workers in England.” Unpublished doctoral thesis. Royal Holloway, University of London, United Kingdom. https://pure.royalholloway.ac.uk/portal/files/29875911/Crisford_Chogugudza_PhD_Research_Final_Submision_January_2018.pdf

- Condon, L. J., and S. McClean. 2017. “Maintaining pre-School Children's Health and Wellbeing in the UK: A Qualitative Study of the Views of Migrant Parents.” Journal of Public Health (United Kingdom) 39 (3): 455–463. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdw083

- Crotty, M. 1996. Phenomenology and Nursing Research. South Melbourne: Churchill Livingstone.

- Dahinden, J. 2016. “A Plea for the ‘de-Migranticization’ of Research on Migration and Integration 1.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (13): 2207–2225. doi:10.1080/01419870.2015.1124129

- Davies, N. 2015. “Review: Silence of a Scream: Application of the Silences Framework to Provision of Nurse-led Interventions for ex-Offenders.” Journal of Research in Nursing 20 (3): 232–233. doi:10.1177/1744987115578054

- Davis, K., H. Ghorashi, and P. Smets. 2018. Contested Belonging: Spaces, Practices, Biographies. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

- Degni, F., S. Pöntinen, and M. Mölsä. 2006. “Somali Parents’ Experiences of Bringing up Children in Finland: Exploring Social-Cultural Change Within Migrant Households.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 7 (3). doi:10.17169/fqs-7.3.139

- Edwards, A. C. R., and B. Temple. 2007. “Contesting Cultural Communities: Language, Ethnicity, and Citizenship in Britain.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33 (5): 783–800. doi:10.1080/13691830701359223

- Eshareturi, C., L. Serrant, V. Galbraith, and M. Glynn. 2015. “Silence of a Scream: Application of the Silences Framework to Provision of Nurse-led Interventions for ex-Offenders.” Journal of Research in Nursing 20 (3): 218–231. doi:10.1177/1744987115577848

- Farr, J., L. Blenkiron, R. Harris, and J. A. Smith. 2018. ““It’s My Language, My Culture, AndIt’s Personal!” Migrant Mothers’ Experience of Language Use and Identity Change in Their Relationship with Their Children: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis’.” Journal of Family Issues 39 (11): 3029–3054. doi:10.1177/0192513X18764542

- Gaidzanwa, R.. 2003. “Gender and Race in the Empowerment Discourse in Zimbabwe.” In The Anthropology of Power: Empowerment and Disempowerment in Changing Structures, edited by Angela Cheater, 117–130. London: Routledge.

- Gray, D. E. 2018. Doing Research in the Real World. 4th ed. London: SAGE.

- Gunaratnam, Y. 2003. Researching ‘Race’and Ethnicity: Methods, Knowledge and Power. London: Sage Publications.

- Hall, S. 1997a. “The Local and the Global: Globalisation and Ethnicity.” In Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation and Post- Colonial Perspectives, edited by A. McClintock, A. Mufti, and E. Shohat, 173–187. London: University of Minnesota press.

- Hall, S. 1997b. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage publishers.

- Hana, R. 2010. “Zimbabwean Women and HIV Care Access Analysis of UK Immigration and Health Policies.” Unpublished doctoral thesis. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK. doi:10.17037/PUBS.00682429

- Janes, G., M. Sque, and L. Serranto. 2018. “Screaming Silences: Lessons from the Application of a new Research Framework.” Nurse Researcher 26 (2): 32–36. doi:10.7748/nr.2018.e1587

- Jenkins, R. 1996. Social Identity. London: Routledge.

- Johnson, J. C., and S. C. Weller. 2002. “Elicitation Techniques for Interviewing.” In Handbook of Interview Research Context and Method, edited by J. F. Gubrium, and J. A. Holstein, 491–514. London: Sage.

- Kanchense, J. H. M. 2006. “Holistic Self-Management Education and Support: A Proposed Public Health Model for Improving Women's Health in Zimbabwe.” Health Care for Women International 27 (7): 627–645. doi:10.1080/07399330600803774

- Kendrick, L. 2010. “Experiences of Cultural Bereavement Amongst Refugees from Zimbabwe Living in the UK.” Unpublished Doctoral Thesis. University of East Anglia, UK. https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/45677

- Kesler, C., and L. F. Schwartzman. 2015. “From Multiracial Subjects to Multicultural Citizens: Social Stratification and Ethnic and Racial Classification among Children of Immigrants in the United Kingdom.” International Migration Review 49 (3): 790–836. doi:10.1111/imre.12101

- Laverty, S. M. 2003. “Hermeneutic Phenomenology and Phenomenology: A Comparison of Historical and Methodological Considerations.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2 (3): 21–35. doi:10.1177/160940690300200303

- Levy, D. 2013. “On the Outside Looking in? The Experience of Being a Straight, Cisgender Qualitative Researcher.” Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services 25 (2): 197–209. doi:10.1080/10538720.2013.782833

- Machaka, R., R. Barley, L. Serrant, P. Furness, and M. Dunham. 2021. “Parenting among Settled Migrants from Southern Africa: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 30: 2264–2275. doi:10.1007/s10826-021-02013-2

- Machoko, C. G. 2013. “Religion and Interconnection with Zimbabwe: A Case Study of Zimbabwean Diasporic Canadians.” Journal of Black Studies 44 (5): 472–495. doi:10.1177/0021934713492174

- Madziva, R., S. McGrath, and J. Thondhlana. 2016. “Communicating Employability: The Role of Communicative Competence for Zimbabwean Highly Skilled Migrants in the UK.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 17 (1): 235–252. doi:10.1007/s12134-014-0403-z

- Madziva, R., and E. Zontini. 2012. “Transnational Mothering and Forced Migration: Understanding the Experiences of Zimbabwean Mothers in the UK.” European Journal of Women's Studies 19 (4): 428–443. doi:10.1177/1350506812466609

- Manase, I. 2013. “Zimbabwean Migrants in the United Kingdom, the new Media and Networks of Survival During the Period 2000-2007.” African Identities 11 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1080/14725843.2013.775839

- Mano, W., and W. Willems. 2008. “Emerging Communities, Emerging Media: The Case of a Zimbabwean Nurse in the British big Brother Show.” Critical Arts 22 (1): 101–128. doi:10.1080/02560040802166300

- Mbakogu, I. 2014. “Who Is the Parent and Who Is the Kid? The Changing Face of Parenting for African Parents in the Diaspora.” In Engaging the Diaspora: Engaging African Families, edited by A. Uwakweh, J. P. Rotich, and C. O. Okpala, 39–58. Plymouth: Lexington publishers.

- McGregor, J. 2007. “‘Joining the BBC (British Bottom Cleaners)': Zimbabwean Migrants and the UK Care Industry.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33 (5): 801–824. doi:10.1080/13691830701359249

- McGregor, J. 2008. “Children and ‘African Values’: Zimbabwean Professionals in Britain Reconfiguring Family Life.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 40 (3): 596–614. doi:10.1068/a38334

- McGregor, J. 2009. “Associational Links with Home among Zimbabweans in the UK: Reflections on Long-Distance Nationalisms.” Global Networks 9 (2): 185–208. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2009.00250.x

- Merry, L., S. Pelaez, and N. C. Edwards. 2017. “Refugees, Asylum-Seekers and Undocumented Migrants and the Experience of Parenthood: A Synthesis of the Qualitative Literature.” Globalization and Health 13 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1186/s12992-017-0299-4

- Migration Observatory. 2017. Settlement in the UK - Migration Observatory. Accessed 17 December 2017. http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/settlement-in-the-UK/

- Miller, H. 2010. Identity and Psychological Well-Being: Experiences of Zimbabwean Males Seeking Asylum in the UK. https://hdl.handle.net/2381/8594.

- Minichiello, V., R. Aroni, E. Timewell, and L. Alexander. 1995. In-Depth Interviewing: Principles, Techniques, Analysis. 2nd ed. Cheshire: Longman.

- Miriyoga, L. 2017. “The Fragmentation and Everydayness of Diasporic Citizenship: Experiences of Zimbabweans in South Africa and the United Kingdom (Year 2000 and Beyond).” Unpublished doctoral thesis. Royal Holloway, University of London, UK. https://pure.royalholloway.ac.uk/portal/files/29345196/2017MiriyogaLphd.pdf.pdf

- Moriarty, J., J. Manthorpe, S. Hussein, and M. Cornes. 2008. Staff Shortages and Immigration in the Social Care Sector. A Report Prepared for the Migration Advisory Committee. London: MAC.

- Mugadza, T., B. Mujeyi, B. Stout, N. Wali, and A. M. N. Renzaho. 2019. “Childrearing Practices Among Sub-Saharan African Migrants in Australia: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 28 (11): 2927–2941. doi:10.1007/s10826-019-01463-z

- Ndlovu, T. 2010. “Where is my Home? Rethinking Person, Family, Ethnicity and Home Under Increased Transnational Migration by Zimbabweans.” African Identities 8 (2): 117–130. doi:10.1080/14725841003629575

- Nyashanu, M. 2017. Beliefs and Perceptions in the Construction of HIV Stigma and Sexual Health Seeking Behaviour Among Black Sub-Sahara African (BSSA) Communities in Birmingham, UK. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Wolverhampton: University of Wolverhampton.

- Ochieng, B. M. N., and C. Hylton. 2010. Black Families in Britain as the Site of Struggle. 1st ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Oheneba-Sakyi, Y., and B. K. Takyi. 2006. African Families at the Turn of the 20th Century. California: Praeger publishing.

- Pasura, D. 2011. “Toward a Multi-Sited Ethnography of the Zimbabwean Diaspora in Britain.” Identities 18 (3): 250–272. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2011.635372

- Pasura, D. 2012. “A Fractured Transnational Diaspora: The Case of Zimbabweans in Britain.” International Migration 50 (1): 143–161. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00675.x

- Pasura, D. 2013. “Modes of Incorporation and Transnational Zimbabwean Migration to Britain.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (1): 199–218. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.626056

- Pasura, D. 2014. African Transnational Diasporas Fractured Communities and Plural Identities of Zimbabweans in Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Powell, M., and C. Rishbeth. 2012. “Flexibility in Place and Meanings of Place by First Generation Migrants.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 103 (1): 69–84. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2011.00675.x

- Raffaetà, R. 2016. “‘Migration and Parenting: Reviewing the Debate and Calling for Future Research’.” International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 12 (1): 38–50. doi:10.1108/IJMHSC-12-2014-0052

- Roland, A. 1996. Cultural Pluralism and Psychoanalysis: The Asian and North American Experience. New York: Routledge.

- Rossetto, M., ÉM Brand, L. B. Teixeira, D. L. L. C. D. Oliveira, and L. Serrant. 2018. “The Silences Framework: Method for Research of Sensitive Themes and Marginalized Health Perspectives.” Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem 26 (4). doi:10.1590/0104-07072017002910017

- Serrant-Green, L. 2004. “Black Caribbean Men, Sexual Health Decisions and Silences.” Doctoral dissertation. University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK.

- Serrant-Green, L. 2011. “The Sound of ‘Silence’: A Framework for Researching Sensitive Issues or Marginalised Perspectives in Health.” Journal of Research in Nursing 16 (4): 347–360. doi:10.1177/1744987110387741

- Shaw, C. M. 2015. Women and Power in Zimbabwe: Promises of Feminism. Baltimore, United States: University of Illinois Press.

- Tasosa, W. D. 2018. Ethno-epidemiology of Alcohol use among Zimbabwean Migrants Living in the UK. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Hallam University.

- Tettey, W. J., and K. P. Puplampu. 2006. The African Diaspora in Canada: Negotiating Identity and Belonging. Calgary: University of Calgary Press.

- Tevera, D., and L. Zinyama. 2002. Zimbabweans who Move: Perspectives on International Migration in Zimbabwe. Migration Policy Series no. 25, Cape Town: Southern African Migration Project.

- United Nations Population Fund. 2019. Migration. http://www.unfpa.org/migration.

- van Manen, M. 1990. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy. 1st ed. London: Althouse Press.

- van Manen, M. 1997. “From Meaning to Method.” Qualitative Health Research 7 (3): 345–369. doi:10.1177/104973239700700303

- Wiederhold, A. 2015. “Conducting Fieldwork at and Away from Home: Shifting Researcher Positionality with Mobile Interviewing Methods.” Qualitative Research 15 (5): 600–615. doi:10.1177/1468794114550440

- Wiklund, H., M. Wikman, U. Högberg, S. Aden Abdulaziz, and Lars Dahlgren. 2000. “Somalis Giving Birth in Sweden: A Challenge to Culture and Gender Specific Values and Behavior.” Midwifery 16 (2): 105–115. doi:10.1054/midw.1999.0197

- Wilson, J. 2010. Essentials of Business Research, a Guide to Doing Your Research Project. London: Sage.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2006. “Intersectionality and Feminist Politics.” European Journal of Women's Studies 13 (3): 193–209. doi:10.1177/1350506806065752