ABSTRACT

This paper compares immigration reforms across democratic and autocratic states. Mobilising two large-scale datasets, it first challenges the prevailing notion that political regime types inherently dictate immigration policy outputs. The analysis shows that although immigration is central to political debates worldwide, reforms are not that frequent and, when enacted, their restrictiveness does not consistently differ by regime type. Instead, restrictions focus on border controls and openings on entry and integration policies regardless of the political regime in place. The paper then mobilises case studies from around the globe to delve into the policy dynamics underpinning immigration reforms across regimes. It shows that while all migration states grapple with the multifaceted challenges that immigration raises, autocratic politics offers a broader toolkit to resolve the trade-offs between cultural, rights-based, economic and security issues. This creates unexpected opportunities for open immigration reforms under autocratic politics, a dynamic I call the ‘illiberal paradox’ as a counterpart to the ‘liberal paradox’ observed under democratic politics. To advance theory-building across the democracy/autocracy divide, the paper concludes by arguing that the liberal and illiberal paradox concepts are not exclusive to democratic or autocratic regimes, respectively, but are valuable analytical tools to understand immigration politics across the political regime spectrum.

1. Introduction: immigration policy trade-offs across varieties of migration states

As part of its ‘reflexive turn’ (Dahinden, Fischer, and Menet Citation2021), migration studies has embarked upon a ‘decentering’ agenda to move beyond the Western-centrism of earlier works (Fiddian-Qasmiyeh Citation2020; Gazzotti, Mouthaan, and Natter Citation2023; Gisselquist and Tarp Citation2019; Nawyn Citation2016; Stock, Üstübici, and Schultz Citation2019). This entailed both the empirical exploration of ‘non-Western’ cases and the re-evaluation of theories and concepts emanating from research on migration politics in Western liberal democracies (Abdelaaty Citation2021; Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2020; Natter Citation2018; Stel Citation2021). The special issue that this article is part of advances this agenda by scrutinising the concept of the migration state and its applicability beyond ‘classical’ cases in Western Europe and North America (Adamson, Chung, and Hollifield Citation2024).

Introduced by Hollifield (Citation2004), the migration state concept points to the centrality of migration control as a core function of modern nation-states. In short, regulating human mobility through passports, visas and border controls ‘contribute[s] to constituting the very ‘state-ness’ of states’ (Torpey Citation1997: 240). However, migration by definition cuts across questions of security, culture, economy, and rights at national and international levels, and so migration states are inevitably faced with trade-offs when developing their migration policies (Hollifield and Foley Citation2022).

Studying liberal-democratic migration states, Hollifield (Citation1992) argued that governments face a liberal paradox when elaborating their immigration policies: While the dominant ideology of economic and rights-based liberalism would drive democracies to open up their labour markets to foreigners and to enshrine migrant rights, national identity and security concerns, as well as the political logic of electoral cycles would push them to restrict immigration. Because governments have to navigate this trade-off between economic openness and political closure, political discourses about immigration, which respond mainly to national audiences, tend to be more restrictive than ultimately enacted policies that also integrate the demands of employer lobbies or international norms. This liberal paradox in turn can explain why, despite the growing politicisation of immigration and popular calls for restrictions across Western liberal democracies, governments have continued to enact open immigration reforms over the 20th and 21st centuries (de Haas, Natter, and Vezzoli Citation2018).

Hollifield’s migration state concept and the associated liberal paradox thus offer a powerful analytical framework to grasp the often-contradictory economic and political interests democratic governments have to reconcile when managing migration and to analyze the inconsistencies between declared reform intentions, enacted policy measures and their ultimate implementation (Bonjour Citation2011; Hollifield et al. Citation2022; Czaika and de Haas Citation2013). However, to what extent these dynamics are shaped by the political regime in place, and thus to what extent the liberal paradox travels beyond the ideal-typical ‘liberal-democratic’ migration state, remains underexplored.

Building upon incipient work on this question (Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2020; Hollifield and Foley Citation2022), the special issue this paper is part of examines and theorises varieties of migration states across the globe. On the one hand, it complements scholarship on the classical ‘liberal-democratic’ migration state by introducing new ideal-types that take into consideration specific state-formation trajectories, such as the ‘imperial’ migration state (Klotz Citation2024), the ‘post-colonial’ migration state (Sadiq and Tsourapas Citation2024), ‘entangled’ migration states (Adamson Citation2024) or the ‘developmental’ migration state (Chung, Draudt, and Tian Citation2024). On the other hand, the special issue explores proto-typical examples of liberal and illiberal migration states more in-depth: In particular, analyses of Canada (Triadafilopoulos and Taylor Citation2024) and the Gulf states (Thiollet Citation2024) showcase how, at both sides of the political regime spectrum, states mobilise a combination of liberal and illiberal policy tools to resolve the dilemmas that immigration raises at the intersection of national and international policy spheres.

As part of this conceptual endeavour, but in contrast to other contributions in this special issue that mobilise in-depth single case studies to develop a more fine-grained typology of the migration state, this paper takes on a bird’s-eye view to compare immigration reforms across democratic and autocratic states. This, I argue, is necessary to better understand the extent to which political regimes matter (or don’t matter) for immigration policies and politics.Footnote1 Weaving together both quantitative and qualitative empirical material with conceptual discussions around migration states and policy trade-offs, the paper first explores broad trends in immigration policy reform across political regimes and then zooms into the dynamics of democratic and autocratic immigration politics.

The analysis in section 2, where I look at policy reform intentions and ultimately enacted reforms, offers two key findings: First, despite the intense politicisation of immigration across the globe, immigration reform overall remains a relatively rare event in a largely path-dependent policy field. Second, when reforms are enacted, the change in restrictiveness introduced does on average not substantially differ based on the type of political regime in place. Instead, there seem to be issue-specific trade-offs at play, with open reforms dominating entry and integration policies and restrictive reforms dominating border control policies across political regimes. This insight challenges the still-dominant assumption in the literature of an intrinsic link between political regimes and immigration policy outputs, i.e. that democracy would lead to open and autocracy to restrictive immigration reforms.

As political regime types (democracy/autocracy) per se seem to have little explanatory power for immigration reform restrictiveness, we need to look more closely at the policy processes underpinning these reforms. This is where political regimes matter – at least to some extent. In section 3 of the paper, I mobilise qualitative case-study insights from around the globe to show that autocratic politics offers decision-makers a wider range of policy tools to resolve the trade-offs between cultural, rights-based, economic and security aspects of immigration compared to democratic politics. In fact, while all migration states are subject to the international forces of economic and rights-based liberalism that drive immigration openness, autocratic politics is freer (though not entirely free) from potential popular anti-immigration sentiments, as well as from inter-institutional dynamics that tend to push for immigration closure in democratic contexts. Paradoxically, this means that autocratic politics creates more room for open immigration reforms compared to democratic politics if this suits the economic, foreign policy or domestic political priorities of the country’s leadership. Importantly, this does not imply that autocratic politics leads to overall more open immigration policy outputs, but only that it creates more leeway to enact them compared to democratic politics. I capture this feature of autocratic immigration politics – the clash between the repression of citizens’ political and human rights inherent to autocratic politics (Brooker Citation2014; Cassani and Tomini Citation2020) and the potential for expanding migrants’ entry, stay and integration rights – through the notion of the illiberal paradox, which I introduce as a counterpart to the liberal paradox in democratic politics.Footnote2

The paper concludes with a reflection on how to advance the scholarly debate on policy trade-offs around immigration across political regimes. I argue that the dynamics captured by the liberal and illiberal paradoxes are not limited to their ‘natural habitats’, i.e. the liberal paradox to democratic regimes and the illiberal paradox to autocratic regimes. In fact, autocracies also need to secure their domestic legitimacy and are not immune to popular demands, while democracies also have policy instruments at their disposal that allow them to take decisions free from parliamentary oversight or popular scrutiny. The liberal and illiberal paradox concepts thus offer fruitful analytical tools to explain immigration reforms across the political regime spectrum, as they capture dynamics inherent to democratic and autocratic politics and not democratic and autocratic regimes.

2. The restrictiveness of immigration reform across political regimes: a bird’s-eye view

2.1. The democracy/autocracy binary: a still-dominant divide in migration policy studies

Despite the burgeoning migration policy literature in recent years, debates around the role of political regimes have remained dominated by the assumption that there is an intrinsic link between the restrictiveness of immigration reforms and the type of political regime in place. As I have argued elsewhere (Natter Citation2023: 4–6), this assumption has its roots in empirical studies that showed how the structure and processes of liberal democracy can limit states’ possibilities to restrict immigration (Freeman Citation1995; Hampshire Citation2013; Sassen Citation1996a). Migration scholars have for instance argued that ‘accepting unwanted immigration is inherent in the liberalness of liberal states’ (Joppke Citation1998: 292). Also political theory work has suggested such a link, emphasising that safeguarding foreigners’ rights is the ultimate litmus test for liberal democracy (Abizadeh Citation2008; Carens Citation2013; Cole Citation2000).

More recently, critical migration and securitisation scholars have cast doubt on such claims by showcasing how consolidated democracies in Europe and elsewhere have enacted increasingly illiberal, rights-denying policies towards foreigners (Adamson, Triadafilopoulos, and Zolberg Citation2011; Guild, Groenendijk, and Carrera Citation2009; Huysmans Citation2009; Skleparis Citation2016). Also political theorists and post-colonial scholars have argued that exclusion is inherent to the democratic project and that, historically, the consolidation of Western liberal democracy has been built on the oppression of ‘underserving’ populations – be they colonial subjects, women, Black people or migrants (Miller Citation2016; Song Citation2019; Bhambra et al. Citation2020). This has challenged the assumed link between democracy and open immigration reforms.

In this debate on the role of political regimes in immigration policy, the other side of the coin – immigration policies and politics in autocracies – has long remained underexplored and undertheorized (Natter and Thiollet Citation2022; Natter Citation2023). This has been in part due to a tendency to view autocratic policymaking as centralised and devoid of negotiations dynamics – and thus of minor interest to scientific investigation – and due to a widespread belief that, apart from the wealthy Oil monarchies in the Gulf, few people migrate to autocracies, as these are usually places people want to leave. Numbers, of course, tell a different story, as eight in ten refugees and one in two migrants worldwide reside outside of liberal democracies (UNDESA Citation2019; UNHCR Citation2021). In recent years, as part of the decentring agenda in migration studies mentioned earlier, research on immigration politics in autocracies has flourished (Blair, Grossman, and Weinstein Citation2020; Filomeno and Vicino Citation2020; Milner Citation2009; Mirilovic Citation2010; Natter Citation2021; Ruhs and Martin Citation2008; Shin Citation2017; Thiollet Citation2022).Footnote3 However, empirical insights have so far remained largely region-specific and analytically separate from theory-building on liberal democracies, apart from a few notable exceptions (Abdelaaty Citation2021; Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2020; Garcés-Mascareñas Citation2012; Stel Citation2021; Natter Citation2023).

To scrutinise the assumption that immigration reforms are fundamentally different across the democracy/autocracy divide, we need to bridge research across regions and regimes by examining immigration policy in autocracies and democracies across the Global North and Global South simultaneously. The analysis in this section does so by drawing on two publicly available, large-scale datasets: (1) the UN World Population Policies Database, which provides insights into 197 governments’ self-declared reform intentions regarding legal immigration over the 1976–2015 period;Footnote4 and (2) the DEMIG POLICY database, which tracks 6,500 changes in migration policy restrictiveness of 45 countries between 1900 and 2014.Footnote5 Importantly, both datasets focus on the changes in restrictiveness introduced by immigration reforms, not on absolute levels of restrictiveness.Footnote6

Both datasets are complemented by information on countries’ political regimes as recorded by the Polity IV dataset (Marshall, Gurr, and Jaggers Citation2016: 14).Footnote7 While the UN World Population database offers global coverage, DEMIG POLICY is skewed towards democracies, with 83% of the recorded migration reforms enacted by democratic regimes and only 17% by autocratic or hybrid regimes.Footnote8 Nonetheless, it is to date the most comprehensive dataset on enacted migration reforms available (Scipioni and Urso Citation2017; Solano and Huddleston Citation2021) and as such can provide unique comparative insights.

The analysis below reveals two key insights: First, although immigration occupies a central place in political debates worldwide, immigration reforms seem to remain an exception in a largely path-dependent policy field. Second, when reforms are enacted, they do not systematically differ in their restrictiveness depending on the political regime in place. Instead, there seem to be issue-specific trade-offs at play depending on the policy area at stake, with open reforms dominating entry and integration policies and restrictive reforms dominating border control policies.

2.2. Immigration reform: a rare intention

With its global coverage, the UN World Population Policies database offers unprecedented insights into governments’ declared intentions on immigration across political regimes and world regions, even if it only captures government positions on legal immigration and not irregular migration or integration issues.

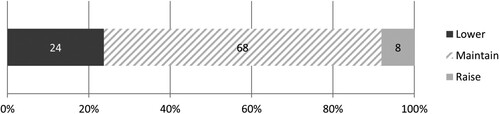

Descriptive analyses yield a surprising picture of global immigration policy intentions: Against the expectation that governments mainly seek to restrict immigration, since the mid-1970s, on average only 24% of governments worldwide declared their intention to reduce immigration, against 8% seeking to increase immigration (). Most notably, the large majority of governments (68%) declared their intention to maintain existing levels of legal immigration. This suggests that despite heated political debates around immigration – not only around irregular migration but also around (legal) family and labour migration – policy reform remains a rare goal in a strongly path-dependent policy field. While we cannot deduce further substantive insights on the absolute level of restrictiveness from such policy continuity – as ‘maintaining’ existing policies can apply to both open and restrictive policies in place – it is nonetheless striking that governments on average prefer to keep their current immigration policies in place rather than reform them.

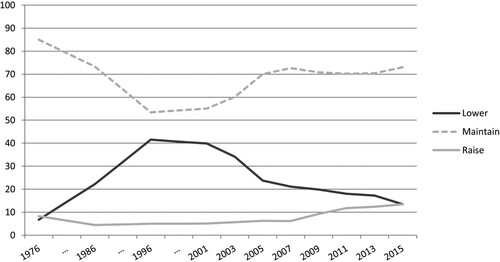

The analysis over time () shows that the number of governments seeking to reduce immigration peaked in the mid-1990s, which might be partly due to the end of the Cold War and its associated geopolitical shifts. In particular, the democratisation of many countries around the world (Boese, Lindberg, and Lührmann Citation2021) and the related ‘exit revolution’ (Zolberg Citation2007), i.e. the dismantling of emigration restrictions, boosted emigration worldwide. Growing migration, as well as the falling away of ideological reasons for hosting migrants and refugees from the ‘Eastern bloc’ after 1989, may have led to a backlash in Western destination countries, mirrored in more restrictive policy objectives. A second observation is that the share of countries seeking to increase immigration grew over time, from under 5% in the 1980s to over 13% in 2015. This could be due to the expansion of policies geared towards attracting skilled migrants to particular economic sectors in Europe and North America (Czaika Citation2018), but it might also reflect the industrialisation of Asian economies such as China, Thailand and South Korea, and their associated transition from emigration to immigration countries, particularly for migrant workers.

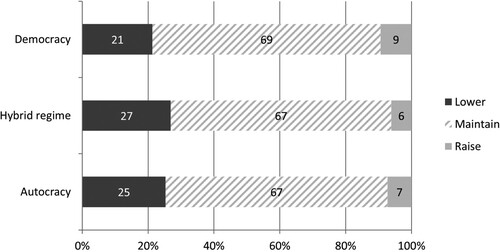

Crucially, distinguishing between regime types does not alter these global patterns (): At an aggregate level, governments classified as democracies, hybrid regimes or autocracies do not significantly differ in their declared immigration policy intentions, as about two-thirds of governments – regardless of regime type – intend to maintain their policies on legal immigration. This does not imply that there are not vast legal differences in how individual countries regulate immigration in terms of the numbers of migrants allowed in and the rights granted to them (Ruhs Citation2013), as the database only captures governments’ declared intentions to reform policy towards more or less restrictiveness – not countries’ absolute levels of immigration policy restrictiveness. Nonetheless, the absence of any systematic difference in declared policy intentions suggest that to understand the role of political regimes in immigration policy, a simple look at policy preferences across regime types is insufficient.

2.3. Enacted immigration reforms: issue-specific, not regime-specific patterns of restrictiveness

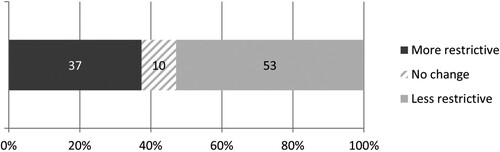

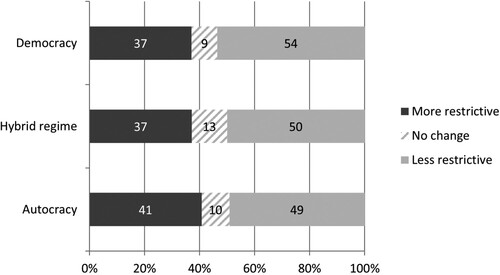

In the context of an immigration policy field characterised by path dependency and policy continuity, DEMIG POLICY allows us to zoom into the rare instances when governments have enacted measures to open or restrict migration. Taking all migration reforms recorded since 1900 across the 45 countries together,Footnote9 53% of reforms enacted open changes, 37% restrictive changes, and 10% led to no change in restrictiveness ().Footnote10

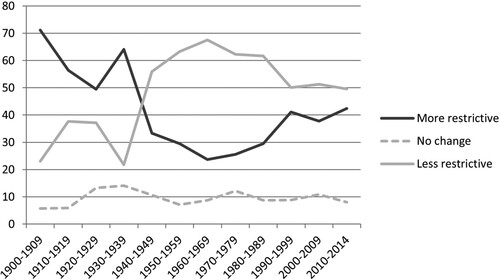

The analysis over time () shows that the restrictiveness of migration reforms developed in three phases: From 1900 until the end of WWII, restrictive changes prevailed, which is consistent with the broader trends of nationalism and protectionism that characterised the period in-between and during the two world wars (Timmer and Williams Citation1998). From the late 1940s to the late 1980s, open migration reforms dominated – a period of so-called ‘liberal interregnum’ (Hollifield Citation2022), when large-scale labour migration programmes and family reunification rights were expanded across Europe and North America, and progressive migration reforms were enacted worldwide in the wake of decolonisation and independence. Since the 1990s, the proportion of more and less restrictive changes converged. While open changes continue to outnumber restrictive ones on average, particularly when it comes to labour migration, we can observe a proliferation of restrictive changes related to the securitisation and technologization of border controls.Footnote11 As argued elsewhere (de Haas, Natter, and Vezzoli Citation2018), these patterns demonstrate the growing selectivity of migration policies.

Similar to the findings on declared policy intentions, disaggregating the data on enacted migration reforms along regime types does not change these patterns ():Footnote12 The proportion of more and less restrictive changes enacted by democracies, hybrid regimes and autocracies does not significantly differ, with about 50% of migration reforms across all regime types enacting changes towards more openness. This suggests that countries’ policy choices to open or restrict immigration are not regime-specific, i.e. not fundamentally linked to the nature of the political regime in place. Again, as DEMIG POLICY focusses on relative changes in restrictiveness introduced by reforms, this does not imply that there are no differences in absolute levels of restrictiveness across countries. However, political regime types per se seem to have little explanatory power for immigration reform restrictiveness. Instead, as shows, there seem to be issue-specific dynamics at play that shape governments’ reform choices on particular aspects of migration policy regardless of the political regime in place.Footnote13

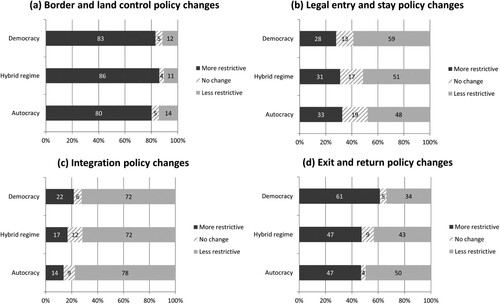

One crucial feature of the DEMIG POLICY database is that it allows to disaggregate migration reforms along four broad policy areas: border control, entry and stay, integration, and return policies. The analysis shows that while the share of more and less restrictive changes is comparable across regime types for each policy area, it varies significantly across the policy areas at stake. For instance, border control policies are overwhelmingly subject to restrictive reforms (a), while integration measures are overwhelmingly subject to open reforms (c), and these results hold across regime types. This latter result is surprising, as migrants’ integration rights are expected to be weaker in autocracies where citizens’ socio-political rights are by definition curtailed. Understanding this result requires a more in-depth look at policy processes underpinning reforms, which is what section 3 of the paper will focus on. The only policy area with substantial differences across regime types are exit and return policies which, on average, are characterised by more open reforms in autocracies (d). This might be explained by the fact that the autocracies included in DEMIG POLICY are often also important emigration countries,Footnote14 and so their exit policies target not only foreigners, but also their own emigrants via diaspora engagement policies. In contrast, the exit policies of democracies mostly capture (forced) return policies targeting the foreign-born.

To conclude: While the assumption of an intrinsic link between political regime type and immigration policy outputs still dominates the migration policy literature, which so far largely focused on either democracies or autocracies, the comparative analysis of democratic and autocratic contexts suggests that changes in immigration policy restrictiveness are not inherently regime-specific. Instead, there seem to be issue-specific trade-offs at play for each distinct migration policy area (see also Triadafilopoulos and Taylor Citation2024). To explain reform restrictiveness, we therefore need to go beyond static political regime categories and look more closely at politics, i.e. the policy tools available to governments to resolve trade-offs inherent to immigration reform. As the next section argues, this is where political regimes matter – at least to some extent.

3. Immigration reform dynamics under democratic and autocratic politics

3.1. Conceptualising the liberal and illiberal paradoxes

As introduced earlier, James Hollifield coined the term liberal paradox in 1992 to describe the trade-off that liberal democracies face when elaborating their immigration policies. As one of the most prominent concepts in migration studies (Acosta Arcarazo and Freier Citation2015; Bonjour Citation2011), the liberal paradox posits that immigration policymaking in liberal-democratic migration states is subject to two contradictory logics, whereby ‘the economic logic of liberalism is one of openness, but the political and legal logic is one of closure’ (Hollifield Citation2004: 886–7): On the one hand, so the argument goes, the dominant ideology of liberalism drives the globalisation of capitalist (labour) markets and the enshrinement of international human rights, and hereby provides the ground for open immigration reforms. On the other hand, the politics of democratic nation-states are dominated by electoral objectives, security concerns and national identity claims and therefore drive immigration restrictions.

In this context, scholarship has attributed pro-immigration reforms to the lobbying efforts of employers and advocacy groups, or to the limits human rights norms and courts impose on national policymaking; while anti-immigration reforms are explained mainly through electoral dynamics, party politics and public opinion (Boswell Citation2007; Freeman Citation1995; Hampshire Citation2013; Joppke Citation1998; Meyers Citation2000; Sassen Citation1996b). As a result of such dynamics, democratic politics around immigration often display ‘discursive gaps’ (Czaika and de Haas Citation2013; Hollifield et al. Citation2022), whereby discourses about immigration that mainly target national political audiences tend to be more restrictive than ultimately enacted policies that also integrate the demands of markets and international norms.

I argue that while all migration states face similar challenges with regards to the cultural, rights-based, economic and security issues that immigration inevitably raises, autocratic politics offers decision-makers a wider range of policy tools to resolve these trade-offs. Paradoxically, this means that autocratic politics creates more room for open immigration reforms compared to democratic politics if such opening suits the economic, foreign policy or domestic political priorities of the country’s leadership. This does not imply that autocratic politics leads to overall more open immigration policy outputs. Many autocracies have drastically restricted immigration and curtailed migrants’ rights in the past and continue to do so, and as section 2 has just shown, there is no substantial difference in terms of the average change of restrictiveness introduced by immigration reforms across political regimes. However, as I develop below, features inherent to autocratic politics offer more leeway to enact open immigration reforms, a dynamic that I term the illiberal paradox as a counterpart to the liberal paradox observed in democratic immigration politics.

I argue that, on the one hand, autocratic politics is subject to the same economic and normative drivers that underpin open immigration reform in democratic politics: Globalisation and trade liberalisation do not halt in front of autocratic leaders – who are equally pressured to open their (labour) markets to international flows than democratic leaders. Yet, immigration policy openness under autocratic politics is not solely driven by economic globalisation dynamics. As Hollifield (Citation1992: 587) already pointed out in his initial formulation of the liberal paradox, ‘respect for human (and civil) rights can compel liberal states (and some that are not so liberal […]) to exercise caution in dealing with migrants.’ And, as FitzGerald and Cook-Martín (Citation2014: 21) have shown in their work on the Americas, it can be crucial for autocratic leaders to perform rights-based liberalism, as ‘migration policies are dramaturgical acts aimed at national and world audiences’. In this sense, both economic and rights-based liberal ideological drivers remain key factors for open immigration reform under autocratic politics.

At the same time, however, I argue that autocratic politics is less constrained by potential popular anti-immigration sentiment among the electorate, as well as inter-institutional dynamics that tend to drive migration restrictions in democratic politics. For instance, for immigration reform to occur in democracies, elected officials need to ensure the compatibility of policy proposals with existing legal frameworks and to strike a compromise among different stakeholders and institutions, often only after lengthy negotiations. Although autocratic leaders also need to forge compromises and reconcile diverging interests with state and societal actors (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Citation2003; Kinne Citation2005; Purcell Citation1973), they have greater leeway to enact fundamental policy shifts and to choose which clients or constituencies to serve through their immigration policies – be they specific ethnic or political groups within society, political, bureaucratic or economic elites, or specific donors and diplomatic partners (Natter Citation2018; Abdelaaty Citation2021). As a consequence of their relative independence from electoral dynamics and institutional constraints, autocratic leaders can thus enact open immigration reforms more easily than democratic leaders, if they wish to do so.

The liberal paradox of democratic politics, i.e. the trade-off between liberal economic drivers for openness and democratic political drivers for closure towards immigration, is thus resolved in the context of autocratic politics. At its place moves the illiberal paradox, the fact that autocratic politics – characterised by non-competitive or un-contested leadership selection, a repressive and arbitrary exercise of political power, as well as limited or absent protection of civil liberties and political rights (Brooker Citation2014; Cassani and Tomini Citation2020) – offers unexpected opportunities for open immigration policies. It is this clash between the repression of citizens’ political and human rights inherent to autocratic politics on the one hand and the potential for expanding migrants’ entry, stay and integration rights on the other that lies at the heart of the illiberal paradox.

3.2. Global empirical evidence for the illiberal paradox

Empirical research on autocratic immigration politics offers both historical and contemporary evidence for the illiberal paradox. Writing about racial selection criteria in immigration policy across the Americas, for instance, FitzGerald and Cook-Martín (Citation2014) conclude that both in Mexico under the regime of Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911) and in Brazil under the Old Republic (1889-1930), governments’ open stance on racial equality was only possible because they were largely independent from anti-immigrant, racist sentiments within the population. This allowed the political leadership to pursue broader geopolitical and economic goals, respectively: In Mexico, ‘the impetus for change came from an elite foreign policy project to use anti-racism as a diplomatic tool to challenge the US and increase Mexico’s cultural influence in Latin America’ (FitzGerald and Cook-Martín Citation2014: 219), while in Brazil, ‘Asian exclusion ended after just two years because only oligarchs sat at the policymaking table [and] the preferences of Brazilian workers were irrelevant to the political process’ (FitzGerald and Cook-Martín Citation2014: 273).

Autocratic politics is also a central element to understand open immigration reforms towards regional labour migration across Central Asia and North Africa since the 2000s. In Kazakhstan for instance, immigration has been part and parcel of the regime’s economic development agenda and a declared goal to counteract demographic decline over the past two decades: In 2006, a one-time regularisation granted legal status to around 164,000 migrants from neighbouring countries (Laruelle Citation2008), and in 2014 and 2017, the regime of President Nazarbayev has enacted reforms to facilitate foreigners’ access to work permits and to liberalise the country’s travel visa regime (IOM Citation2018; Weitz Citation2014). Similarly, in Morocco, the geopolitical and economic priorities of King Mohamed VI have driven open immigration reforms, which shifted Morocco’s approach between 2013–2017 from a policy of expulsion and socio-economic exclusion of (irregular) migrants towards a human-rights based policy that entailed two regularisation campaigns and a set of integration measures (Cherti and Collyer Citation2015; Natter Citation2021; Norman Citation2016). These reforms pursued two goals: to consolidate Morocco’s economic and political leadership across Africa, and to enhance Morocco’s image as a progressive, liberal state and cooperation partner in Europe (see: Natter Citation2021; Norman Citation2020a).

Such illiberal paradox dynamics are, however, not only limited to labour immigration; they are also at play in asylum policy across major refugee-receiving countries in Africa. Since the mid-2000s, for instance, Uganda has adopted a vocally open reception and integration policy for refugees, who are granted freedom of movement and work, access to education and healthcare, as well as a plot of land to cultivate (Watera et al. Citation2017). This refugee policy has allowed President Museveni’s autocratic regime to improve its image at home and abroad, and has helped it to attract development aid and economic investments. As Betts (Citation2021: 243) highlights, ‘refugee policy has been used by Ugandan leaders to strengthen patronage and assert political authority within strategically important refugee-hosting hinterlands,’ such as the less developed, north-western parts of the country. In a similar vein, the adoption of refugee-friendly policies in Zambia since 2014 has gone hand in hand with a shift towards autocracy. In particular, President Lungu has been able to disregard popular calls for restriction and contestation from within the bureaucratic apparatus to enact an open refugee policy that would secure his regime international support. As Maple (Citation2018) writes, ‘the president personally intervened to develop the new Refugee Act, and he ignored ministerial departments’ demands that former refugees from Rwanda be repatriated. […] Lungu is free to implement programmes and initiatives based on self-interest and ideological commitments without being overly concerned about opposition parties or losing a re-election’.

These empirical examples of the illiberal paradox illustrate how autocratic politics decreases the weight of institutional path-dependency and gives priority to strategic interests over domestic public opinion, hereby facilitating open immigration reforms. However, the autocratic politics that underpin the illiberal paradox also have their in-built limitations. As I outline next, policy volatility, the fragile rule of law and the so-called ‘reverse discursive gap’ partly jeopardise what open immigration reforms under autocratic politics might mean for migrants on the ground.

3.3. The limits of the illiberal paradox

A first limitation of the illiberal paradox is that announcements of open immigration reforms might not always be followed through on paper. Mirroring the discursive gap in democratic politics, where politicians seek to please the electorate with their ‘tough talk’ on immigration while pursuing more open policies on paper (de Haas, Natter, and Vezzoli Citation2018), autocratic politics can lead to discursive openness and restrictiveness on paper. This ‘reverse discursive gap’ (see also: Acosta Arcarazo and Freier Citation2015) is related to the fact that welcoming discourses on immigration might first and foremost fulfil a symbolic role towards a specific (often international) audience. Morocco’s opening towards immigration since 2013, for instance, has remained partially discursive, as only certain measures were enacted (i.e. regularisation campaigns, migrants’ access to education), while others remained at the level of announcements (i.e. asylum law, access to health care) (Natter Citation2021). Also, as Thiollet (Citation2024) shows in her analysis, Gulf states have strategically announced migrant rights’ reforms or signed international agreements for reputational purposes in their diplomatic relations with Asian sending states, leading to a dynamic of ‘migrant rights washing’ that is not reflected in de jure policies or policy practices.

Second, while autocratic politics is less constrained by routinised inter-institutional dynamics than democratic politics, and decision-makers can therefore more easily announce and enact open immigration reforms, this also increases the reform’s vulnerability to sudden, restrictive backlashes. The fact that open immigration reforms often emerge out of executive decisions such as ministerial orders or decrees means that they can also be rapidly retracted or adjusted. Policy volatility is thus a distinct feature of autocratic immigration politics, and, as a result, immigration policy often fluctuates between progress and backlashes depending on the state’s strategic interests or changes in (inter)national contexts. Libya’s ‘politics of contradictions’ (Paoletti Citation2011: 221) towards African labour migrants under the regime of Colonel Gaddafi is exemplary for this: In the early 1990s, Gaddafi’s geopolitical shift from pan-Arabism to pan-Africanism was accompanied by the decision to open up the country to immigration, and several hundred thousand Sub-Saharan African migrants arrived to work in the booming rentier economy and oil industry (Paoletti Citation2011; Tsourapas Citation2017). Yet, when geopolitical and economic circumstances changed in the early 2000s, Gaddafi reversed his policy and ordered massive expulsions of migrant workers. Similarly, in Thailand, a major destination for labour migrants from Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos, immigration policy has fluctuated in conjunction with political leadership shifts: While the government administered regularisation campaigns in 1992 and 2009, granting legal status to nearly 1.3 million workers from neighbouring countries (Pracha Citation2010), in 2014 and 2017 massive crack-downs on irregular migrants took place and higher penalties for irregular stay and work were introduced – just to abolish them shortly afterwards in response to increased pressure from migrants and employers (Vigneswaran Citation2020).

Related to such policy volatility, the third limitation of the illiberal paradox stems from the fragile rule of law in autocratic contexts, as open immigration policies on paper do not necessarily offer legal protections in practice. In particular, the often-lacking independence of courts limits migrants’ ability to effectively claim rights through legal proceedings (WJP Citation2018). As research on Russia for instance shows, such weak legal protections turn (irregular) migrants into a resource for institutional or personal benefits of bureaucratic actors and local elites (Kubal Citation2019; Urinboyev Citation2021). Moreover, the fragile rule of law also means that the right to enter a country does not necessarily give rise to long-term residency, socio-economic or family rights, and therefore prevents the spill-over from immigration to integration rights characteristic of democratic immigration politics. This partly explains the large-scale labour immigration programmes across the Gulf, which aim at securing the benefits of oil revenue for the domestic population through importing a largely rights-less class of foreign workers (Fargues Citation2013; Thiollet Citation2022). Ultimately, this feature of autocratic immigration politics – whereby countries have more flexibility to allow migrants in precisely because they can limit their access to further rights (Breunig, Cao, and Luedtke Citation2012; Ruhs Citation2013; Shin Citation2017) – paradoxically gives rise to a situation in which it is de facto easier for many people around the world to migrate to autocracies than to democracies.

4. Conclusion: moving towards the study of autocratic immigration politics in democracies and democratic immigration politics in autocracies

To make sense of open immigration reforms in autocracies and to enlarge the theoretical toolbox available to scholars analyzing immigration policymaking worldwide, in this paper I introduced the illiberal paradox as a counterpart to the liberal paradox observed in democracies (Hollifield Citation1992; Citation2004). I argued that autocratic politics offers political leaders more opportunities to enact open immigration policies compared to democratic politics, if doing so suits the economic, foreign policy, or domestic priorities of the political leadership in place. The cases of Morocco, Uganda, Thailand, Kazakhstan or Mexico discussed earlier provide exemplary evidence for the prevalence of the illiberal paradox across the globe.

To stimulate more global theory-building of immigration policy, I would like to suggest that the dynamics captured by the liberal and illiberal paradox are not exclusively applicable to their ‘natural contexts’, i.e. the liberal paradox to democracies and the illiberal paradox to autocracies. Instead, they allow scholars to makes sense of democratic politics in autocratic regimes and autocratic politics in democratic regimes.

Indeed, autocratic regimes are not immune to public pressures, as they too have to secure their domestic legitimacy by taking into account economic lobbies, public opinion or specific societal groups’ interests in their decision-making – at least to some extent (Keck and Sikkink Citation1998; Natter Citation2014; Norman Citation2020b; Russell Citation1989). For instance, to prevent potential social unrest by the country’s unemployed youth, the Saudi government in 2011 not only increased the distribution of oil rent to the population, but also launched a series of restrictive changes towards immigrants, including highly symbolic measures such as mass deportations (Thiollet Citation2015). Another example is Ecuador, where President Correa’s competitive authoritarian regime faced a public backlash after it removed visa requirements for all nationalities in June 2008. According to Freier (Citation2013: 16), ‘Correa faced internal political pressure from within his administration, from the political opposition and the media to revoke universal visa freedom’. As a result, the open policy was partially reversed (Acosta Arcarazo and Freier Citation2015: 25). Thus, even in an autocratic regime, immigration policymaking has to integrate popular demands to safeguard domestic political legitimacy.

At the same time, democracies also have policy tools at their disposal that allow political leaders to take decisions behind closed doors or free from parliamentary oversight and popular scrutiny – not only to restrict but also to liberalize immigration. In particular, ministerial decrees and executive rule-making common to administrative law enable democratic leaders to enact open immigration reforms in isolation from the public or without being subjected to legal scrutiny (Slingenberg Citationforthcoming). Writing on Canada, FitzGerald and Cook-Martín (Citation2014: 183–4) have for instance shown how removing ethnic selection criteria in immigration policy in the 1960s became possible only through the use of orders-in-council that were safe from parliamentary debate and popular accountability. Travel visa requirements are another classic examples of executive decision-making that lack public control and can be mobilised to respond rapidly and easily to economic or diplomatic priorities without cumbersome legal procedures (de Haas, Natter, and Vezzoli Citation2018: 32). In the EU-context, Thielemann and Zaun (Citation2018) have shown how the delegation of competences on asylum to the supranational EU-level can shield policy-makers from populist pressures for further immigration restrictions and hereby enhance rights of asylum-seekers (see also Bonjour, Ripoll Servent, and Thielemann (Citation2018); Geddes (Citation2000)). Lastly, despite the politicisation of immigration across Europe, large parts of immigration policy – such as labour shortage lists or bilateral agreements – continue to be negotiated behind closed doors and through typical ‘client politics’ (Freeman Citation1995). Albeit often sector-specific and limited in terms of the number of migrants affected, such policy tools are exemplary for the ways in which decision-makers create opportunities for immigration despite their continuously tough rhetoric.

These examples of democratic pressures for immigration restrictions in autocracies and democracies’ reliance on autocratic policy tools to open up immigration policy suggest that the concepts of liberal and illiberal paradox offer fruitful analytical tools for explaining immigration policymaking across the political regime spectrum. This, in turn, invites migration scholarship to shift the analytical focus of migration policy studies from democratic/autocratic regimes to democratic/autocratic politics and hereby to move towards more global theory-building of policy dynamics across varieties of migration states.

Acknowledgement

Over the years, my work on this paper has benefitted from the thoughtful comments of many scholars who I would like to thank here, in particular the participants of the 2019 ECPR Joint Sessions Workshop (Authoritarianism Beyond the State), the 2019 IMISCOE Annual Conference, the 2020 Leiden Interdisciplinary Migration Seminar (LIMS) and 2020 Leiden Political Science Institute Lunch Seminar, as well as the workshop organised by the JEMS special issue convenors in early 2022. Individually, I would like to particularly thank James Hollifield, Lillian Frost, Gerasimos Tsourapas and the anonymous reviewer for their constructive feedback on my paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 I define immigration policies as outputs, i.e. laws, regulations or executive decrees that determine foreigners’ rights in a particular nation-state, relating to both immigrant admission (border controls; entry requirements; deportation policies) and immigrant rights (access to employment, health and welfare benefits or citizenship). I refer to immigration politics as the power relations between non-state and state actors at domestic and international levels that shape migration policies. This covers both the political processes underpinning decisions of how to govern and regulate the volume and rights of immigrants, as well as the policy tools that actors mobilize to resolve the trade-offs involved in migration control.

2 In this paper, the illiberal paradox refers to immigration policymaking. Tsourapas (Citation2022) has developed the idea of an illiberal paradox in relation to autocracies’ emigration policies.

3 In parallel, there is also a more consolidated body of work on autocracies’ emigration policies. See for instance: Alemán and Woods (Citation2014), Brand (Citation2006), Miller and Peters (Citation2020), Tsourapas (Citation2019), or Michel, Miller, and Peters (Citation2023).

4 The database captures governments’ responses to the question of whether they wish to reduce, maintain or raise legal immigration. Importantly, it does not entail governments’ take on irregular migration. For more details, see: https://esa.un.org/poppolicy/about_database.aspx.

5 Policy reforms are coded according to policy area (border controls, entry and stay, integration, and exit) and migrant groups targeted (for instance: low-skilled workers, high-skilled workers, family members, irregular migrants or refugee and asylum seekers). For more details, see: de Haas, Natter, and Vezzoli (Citation2015).

6 Other datasets have aimed at measuring absolute levels of restrictiveness (for an overview, see: Scipioni and Urso Citation2017; Solano and Huddleston Citation2021). However, these datasets almost exclusively focus on democracies of the Global North, and are therefore not suitable for the analysis in this paper. An exception is the dataset by Ruhs (Citation2013) covering 46 high and middle-income countries, but which focuses exclusively on labor migration policies.

7 Polity IV identifies democracies by a score of +6 to +10 points, autocracy by a score of -10 to -6 points, and hybrid regimes by a score of -5 to +5 points.

8 The 45 countries included in DEMIG POLICY (Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Czech Republic, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, German Democratic Republic, Greece, Hungary, Iceland India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, Morocco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States of America, Yugoslavia) are counted as democracy, autocracy or hybrid regime depending on the year in question.

9 The results do not change when limiting the analysis to the post-1950 period, with on average 54% liberal changes, 36% restrictive changes, and 10% of policy reforms introducing no significant change in restrictiveness.

10 ‘No change in restrictiveness’ refers to policy reforms that for instance introduce changes in the institutional set up governing migration, but that do not per se expand or limit migrants’ rights to enter or stay in the country.

11 As Czaika, Bohnet, and Zardo (Citation2021) have shown, this trend has continued over the 2015–2020 period.

12 Also here, results do not change when limiting the analysis to the post-1950 period. If at all, then the difference between autocracies and democracies is further reduced, with democracies showing on average 54% liberal changes, 36% restrictive changes, and 10% of policy reforms introducing no significant change and autocracies on average 54% liberal changes, 38% restrictive changes, and 8% of policy reforms introducing no significant change in restrictiveness after 1950. Only reforms enacted by hybrid regimes since 1950 (covering mainly Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Russia, Hungary, Indonesia, South Korea, Morocco, Turkey, South Africa) showcase a slightly different pattern (29/15/57), with a lower prevalence of restrictive changes and a higher prevalence of policies enacting no change in restrictiveness. Further qualitative research is needed to interpret these results.

13 For a more in-depth conceptualization of issue-specific vs. regime-specific policy dynamics around immigration across political regimes, see Natter (Citation2018; Citation2023).

14 Countries categorized as autocracies in DEMIG POLICY are mainly Latin American and Southern European countries in the 1970s and 1980s (Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Portugal, Greece, Spain), as well as China, Morocco, Russia, Yugoslavia and Indonesia. Gulf countries are not included in DEMIG POLICY; for an analysis of their immigration policies, see Shin (Citation2017), Ruhs (Citation2013) and Thiollet (Citation2015; Citation2022).

References

- Abdelaaty, L. E. 2021. Discrimination and Delegation. Explaining State Responses to Refugees. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Abizadeh, A. 2008. “Democratic Theory and Border Coercion.” Political Theory 36 (1): 37–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591707310090.

- Acosta Arcarazo, D., and L. F. Freier. 2015. “Turning the Immigration Policy Paradox Upside Down? Populist Liberalism and Discursive Gaps in South America.” International Migration Review 49 (3): 659–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12146.

- Adamson, F. B. 2024. “Entangled Migration States: Mobility and State-Building in France and Algeria.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (3): 597–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2269774.

- Adamson, F. B., E. A. Chung, and J. F. Hollifield. 2024. “Rethinking the Migration State: Historicizing, Decolonizing, and Disaggregating.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (3): 559–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2269769.

- Adamson, F. B., T. Triadafilopoulos, and A. R. Zolberg. 2011. “The Limits of the Liberal State: Migration, Identity and Belonging in Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (6): 843–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.576188.

- Adamson, F. B., and G. Tsourapas. 2020. “The Migration State in the Global South: Nationalizing, Developmental, and Neoliberal Models of Migration Management.” International Migration Review 54 (3): 853–882. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918319879057.

- Alemán, J., and D. Woods. 2014. “No way out: Travel Restrictions and Authoritarian Regimes.” Migration and Development 3 (2): 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2014.935089.

- Betts, A. 2021. “Refugees And Patronage: A Political History Of Uganda’s ‘Progressive’ Refugee Policies.” African Affairs 120 (479): 243–276. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adab012.

- Bhambra, G. K., Y. Bouka, R. B. Persaud, O. U. Rutazibwa, V. Thakur, D. Bell, K. Smith, T. Haastrup, and S. Adem. 2020. “Why Is Mainstream International Relations Blind to Racism?” Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/03/why-is-mainstream-international-relations-ir-blind-to-racism-colonialism/.

- Blair, C., G. Grossman, and J. M. Weinstein. 2020. Forced Displacement and Asylum Policy in the Developing World.

- Boese, V. A., S. I. Lindberg, and A. Lührmann. 2021. “Waves of Autocratization and Democratization: A Rejoinder.” Democratization 28 (6): 1202–1210. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1923006.

- Bonjour, S. 2011. “The Power and Morals of Policy Makers: Reassessing the Control Gap Debate.” International Migration Review 45 (1): 89–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2010.00840.x.

- Bonjour, S., A. Ripoll Servent, and E. Thielemann. 2018. “Beyond Venue Shopping and Liberal Constraint: A new Research Agenda for EU Migration Policies and Politics.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (3): 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1268640.

- Boswell, C. 2007. “Theorizing Migration Policy: Is There a Third Way?” International Migration Review 41 (1): 75–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00057.x.

- Brand, L. A. 2006. Citizens Abroad - Emigration and the State in the Middle East and North Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Breunig, C., X. Cao, and A. Luedtke. 2012. “Global Migration and Political Regime Type: A Democratic Disadvantage.” British Journal of Political Science 42: 825–854. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000051.

- Brooker, P. 2014. Non-Democratic Regimes: Theory, Government, and Politics. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bueno de Mesquita, B., A. Smith, R. M. Siverson, and J. D. Morrow. 2003. The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Carens, J. 2013. The Ethics of Immigration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cassani, A., and L. Tomini. 2020. “Reversing Regimes and Concepts: From Democratization to Autocratization.” European Political Science 19 (2): 272–287. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-018-0168-5.

- Cherti, M., and M. Collyer. 2015. “Immigration and Pensée d'Etat: Moroccan Migration Policy Changes as Transformation of ‘Geopolitical Culture’.” The Journal of North African Studies 20 (4): 590–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2015.1065043.

- Chung, E. A., D. Draudt, and Y. Tian. 2024. “The Developmental Migration State.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (3): 637–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2269781.

- Cole, P. 2000. Philosophies of Exclusion: Liberal Political Theory and Immigration. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Czaika, M., ed. 2018. High-Skilled Migration. Drivers and Policies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Czaika, M., H. Bohnet, and F. Zardo. 2021. “The Evolution of the European Migration Policy-Mix.” QuantMig Project Deliverable D5.5.

- Czaika, M., and H. de Haas. 2013. “The Effectiveness of Immigration Policies.” Population and Development Review 39 (3): 487–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00613.x.

- Dahinden, J., C. Fischer, and J. Menet. 2021. “Knowledge Production, Reflexivity, and the use of Categories in Migration Studies: Tackling Challenges in the Field.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (4): 535–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1752926.

- de Haas, H., K. Natter, and S. Vezzoli. 2015. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Migration Policy Change.” Comparative Migration Studies 3 (15).

- de Haas, H., K. Natter, and S. Vezzoli. 2018. “Growing Restrictiveness or Changing Selection? The Nature and Evolution of Migration Policies.” International Migration Review 52 (2): 324–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918318781584.

- Fargues, P. 2013. “International Migration and the Nation State in Arab Countries.” Middle East Law and Governance 5: 5–35. https://doi.org/10.1163/18763375-00501001.

- Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. 2020. “Recentering the South in Studies of Migration.” Migration and Society 3: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3167/arms.2020.030102.

- Filomeno, F. A., and T. J. Vicino. 2020. “The Evolution of Authoritarianism and Restrictionism in Brazilian Immigration Policy: Jair Bolsonaro in Historical Perspective.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 40: 598–612.

- FitzGerald, D. S., and D. Cook-Martín. 2014. Culling the Masses: The Democratic Origins of Racist Immigration Policy in the Americas. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Freeman, G. P. 1995. “Modes of Immigration Politics in Liberal Democratic States.” International Migration Review 29 (4): 881–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791839502900401.

- Freier, Luisa F. 2013. “Open Doors (for Almost all): Visa Policies and Ethnic Selectivity in Ecuador.” London School of Economics (LSE) Working Paper 188.

- Garcés-Mascareñas, B. 2012. Labour Migration in Malaysia and Spain: Markets, Citizenship and Rights. Amsterdam, NL: Amsterdam University Press.

- Gazzotti, L., M. Mouthaan, and K. Natter. 2023. “Embracing complexity in ‘Southern’ migration governance.” Territory, Politics and Governance 11 (4): 625–637.

- Geddes, A. 2000. “Lobbying for Migrant Inclusion in the European Union: New Opportunities for Transnational Advocacy?” Journal of European Public Policy 7 (4): 632–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760050165406.

- Gisselquist, R. M., and F. Tarp. 2019. “Migration Governance and Policy in the Global South: Introduction and Overview.” International Migration 57 (4): 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12623.

- Guild, E., K. Groenendijk, and S. Carrera. 2009. Illiberal Liberal States: Immigration, Citizenship and Integration in the EU. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hampshire, J. 2013. “Immigration and the Liberal State.” In The Politics of Immigration, edited by J. Hampshire, 1–15. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hollifield, J. F. 1992. Immigrants, Markets, and States: The Political Economy of Postwar Europe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hollifield, J. F. 2004. “The Emerging Migration State.” International Migration Review 38 (3): 885–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00223.x.

- Hollifield, J. F. (2022). Migration and the Liberal Paradox in Europe, edited by J. F. Hollifield & N. Foley (Eds.), Understanding Global Migration. Redwood City, CA: Standford University Press.

- Hollifield, J. F., and N. Foley. 2022. Understanding Global Migration. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Hollifield, J. F., P. L. Martin, P. M. Orrenius, and F. Héran, eds. 2022. Controlling Immigration. A Comparative Perspective (Fourth Edition ed.). Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Huysmans, J. 2009. The Politics of Insecurity. Fear, Migration and Asylum in the EU. New York, NY: Routledge.

- IOM. 2018. Migration Governance Snapshot: the Republic of Kazakhstan.

- Joppke, C. 1998. “Why Liberal States Accept Unwanted Immigration.” World Politics 50 (2): 266–293. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004388710000811X.

- Keck, M. E., and K. Sikkink. 1998. Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Kinne, B. J. 2005. “Decision Making in Autocratic Regimes: A Poliheuristic Perspective.” International Studies Perspectives 6 (1): 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-3577.2005.00197.x.

- Klotz, A. 2024. “Imperial Migration States.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (3): 578–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2269772.

- Kubal, A. 2019. Immigration and Refugee Law in Russia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Laruelle, M. 2008. Kazakhstan: The New Country of Immigration for Central Asian Workers. Washington, DC: Central Asia-Caucasus Institute.

- Maple, N. 2018. What’s Behind Zambia’s Growing Welcome to Refugees. News Deeply. https://deeply.thenewhumanitarian.org/refugees/community/2018/06/12/whats-behind-zambias-growing-welcome-to-refugees.

- Marshall, M. G., T. R. Gurr, and K. Jaggers. 2016. POLITY™ IV PROJECT. Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2015. Dataset Users’ Manual.

- Meyers, E. 2000. “Theories of International Immigration Policy - A Comparative Analysis.” International Migration Review 34 (4): 1245–1282.

- Michel, J., M. K. Miller, and M. E. Peters. 2023. “How Authoritarian Governments Decide Who Emigrates: Evidence from East Germany.” International Organization 77: 527–563. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818323000127.

- Miller, D. 2016. Strangers in Our Midst. The Political Philosophy of Immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Miller, M. K., and M. E. Peters. 2020. “Restraining the Huddled Masses: Migration Policy and Autocratic Survival.” British Journal of Political Science 50 (2): 403–433. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000680.

- Milner, J. H. S. 2009. Refugees, the State and the Politics of Asylum in Africa. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Mirilovic, N. 2010. “The Politics of Immigration: Dictatorship, Development and Defense.” Comparative Politics 42 (3): 273–292. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041510X12911363509675.

- Natter, K. 2014. “The Formation of Morocco’s Policy Towards Irregular Migration (2000–2007): Political Rationale and Policy Processes.” International Migration 52 (5): 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12114.

- Natter, K. 2018. “Rethinking Immigration Policy Theory Beyond ‘Western Liberal Democracies’.” Comparative Migration Studies 6 (4): 1–21.

- Natter, K. 2021. “Crafting a ‘Liberal Monarchy’: Regime Consolidation and Immigration Policy Reform in Morocco.” The Journal of North African Studies 26 (5): 850–874. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2020.1800206.

- Natter, K. 2023. The Politics of Immigration Beyond Liberal States. Morocco and Tunisia in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Natter, K., and H. Thiollet. 2022. “Theorising Migration Politics: Do Political Regimes Matter?” Third World Quarterly. 43 (7): 1515–1530. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2022.2069093.

- Nawyn, S. J. 2016. “Migration in the Global South: Exploring New Theoretical Territory.” International Journal of Sociology 46 (2): 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2016.1163991.

- Norman, K. P. 2016. “Between Europe and Africa: Morocco as a Country of Immigration.” The Journal of the Middle East and Africa 7 (4): 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520844.2016.1237258.

- Norman, K. P. 2020a. “Migration Diplomacy and Policy Liberalization in Morocco and Turkey.” International Migration Review 54 (4): 1158–1183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918319895271.

- Norman, K. P. 2020b. Reluctant Reception: Refugees, Migration and Governance in the Middle East and North Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Paoletti, E. 2011. “Migration and Foreign Policy: The Case of Libya.” The Journal of North African Studies 16 (2): 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2011.532588.

- Pracha, V. 2010. Agenda for Labour Migration Policy in Thailand: Towards Long-Term Competitiveness.

- Purcell, S. K. 1973. “Decision-Making in an Authoritarian Regime: Theoretical Implications from a Mexican Case Study.” World Politics 26 (1): 28–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009916.

- Ruhs, M. 2013. The Price of Rights - Regulating International Labor Migration. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ruhs, M., and P. L. Martin. 2008. “Numbers vs. Rights: Trade-Offs and Guest Worker Programs.” International Migration Review 42 (1): 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00120.x.

- Russell, S. S. 1989. “Politics and Ideology in Migration Policy Formulation: The Case of Kuwait.” International Migration Review 23 (1): 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791838902300102.

- Sadiq, K., and G. Tsourapas. 2024. “Labor Coercion and Commodification: From the British Empire to Postcolonial Migration States.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (3): 617–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2269778.

- Sassen, S. 1996a. “Beyond Sovereignty: Immigration Policy-Making Today.” Social Justice 23 (3): 9–20.

- Sassen, S. 1996b. Losing Control? Sovereignty in the Age of Globalization. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Scipioni, M., and G. Urso. 2017. Migration Policy Indexes.

- Shin, A. J. 2017. “Tyrants and Migrants: Authoritarian Immigration Policy.” Comparative Political Studies 50 (1): 14–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015621076.

- Skleparis, D. 2016. “(In)Securitization and Illiberal Practices on the Fringe of the EU.” European Security 25 (1): 92–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2015.1080160.

- Slingenberg, L. forthcoming. Een uitzonderlijke toestand. Over legaliteit in het migratierecht. Amsterdam, NL: Boom Juridische Uitgevers.

- Solano, G., and T. Huddleston. 2021. “Beyond Immigration: Moving from Western to Global Indexes of Migration Policy.” Global Policy 12 (3): 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12930.

- Song, S. 2019. Immigration and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stel, N. 2021. “Uncertainty, Exhaustion, and Abandonment Beyond South/North Divides: Governing Forced Migration Through Strategic Ambiguity.” Political Geography 88: 102391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102391.

- Stock, I., A. Üstübici, and S. U. Schultz. 2019. “Externalization at Work: Responses to Migration Policies from the Global South.” Comparative Migration Studies 7 (48). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0157-z.

- Thielemann, E., and N. Zaun. 2018. “Escaping Populism – Safeguarding Minority Rights: Non-Majoritarian Dynamics in European Policy-Making.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (4): 906–922. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12689.

- Thiollet, H. 2015. “Migration et (contre)révolution dans le Golfe: Politiques migratoires et politiques de l’emploi en Arabie saoudite.” Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 31 (3): 121–143. https://doi.org/10.4000/remi.7400.

- Thiollet, H. 2022. “Migrants and Monarchs: Regime Survival, State Transformation and Migration Politics in Saudi Arabia.” Third World Quarterly 43 (7): 1645–1665.

- Thiollet, H. 2024. “Immigration Rentier States.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (3): 657–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2269783.

- Timmer, A. S., and J. G. Williams. 1998. “Immigration Policy Prior to the 1930s: Labor Markets, Policy Interactions, and Globalization Backlash.” Population and Development Review 24 (4): 739–771. https://doi.org/10.2307/2808023.

- Torpey, J. 1997. “Coming and Going: On the State Monopolization of the Legitimate “Means of Movement”.” Sociological Theory 16 (3): 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2751.00055.

- Triadafilopoulos, T., and Z. Taylor. 2024. “The Domestic Politics of Selective Permeability: Disaggregating the Canadian Migration State.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (3): 702–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2269785.

- Tsourapas, G. 2017. “Migration Diplomacy in the Global South: Cooperation, Coercion and Issue Linkage in Gaddafi’s Libya.” Third World Quarterly 38 (10): 2367–2385. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1350102.

- Tsourapas, G. 2019. The Politics of Migration in Modern Egypt - Strategies for Regime Survival in Autocracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tsourapas, G. 2022. “The Illiberal Paradox and the Politics of Migration in the Middle East.” In Understanding Global Migration, edited by J. F. Hollifield, and N. Foley, 81–99. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

- UNDESA. 2019. International Migration 2019.

- UNHCR. 2021. Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2020.

- Urinboyev, R. 2021. Migration and Hybrid Political Regimes. Navigating the Legal Landscape in Russia. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Vigneswaran, D. 2020. “Migrant Protection Regimes: Beyond Advocacy and Towards Exit in Thailand.” Review of International Studies 46 (5): 652–671. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210520000339.

- Watera, W., C. Seremba, I. Otim, D. Ojok, B. Mukhone, and A. Hoffmann. 2017. Uganda's Refugee Management Approach Within the EAC Policy Framework.

- Weitz, R. 2014. “Kazakhstan Adopts New Policy Toward Foreign Migrants.” Eurasia Daily Monitor 11 (10). https://jamestown.org/program/kazakhstan-adopts-new-policy-toward-foreign-migrants/#.V2_o3O1b9CU.

- WJP. 2018. Rule of Law Index 2017–2018.

- Zolberg, A. R. 2007. “The Exit Revolution.” In Citizenship and Those Who Leave: The Politics of Emigration and Expatriation, edited by N. L. Green, and F. Weil, 33–60. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.