ABSTRACT

Gender roles have become a symbol of cultural division between Western Europe and its growing immigrant population. To what extent immigrants and their children from more gender-conservative backgrounds will adopt more egalitarian attitudes has thus become a key question. However, different host countries offer distinct contexts of reception regarding the institutional support for gender equality, and the diverse compositions of immigrant populations across Europe pose challenges to simultaneously control the influences of cultural origins and settlement contexts. We overcome these challenges by comparing immigrant youth living in five different European countries, originating from countries with comparable levels of gender inequality, as assessed by three distinct global gender inequality indices. Analysing CILS4EU and CILS-NOR data, we found that the extent of gender inequality in parental countries of origin exerts a lasting impact on gender attitudes among immigrant-origin youth. Additionally, our findings showed that religion, particularly among Muslims, plays a role in preservation of conservative attitudes. Nevertheless, immigrant origin youth to a large extent adapt their perspectives to the context of reception, and even the most conservative groups of immigrant adolescents living in Scandinavia have more gender-egalitarian beliefs than immigrants – and to some extent natives – in continental Europe.

Introduction

Over the last half-century, Western Europe have taken considerable steps towards achieving greater equity between men and women, and public attitudes towards gender roles have become increasingly egalitarian (Davis and Greenstein Citation2009; Bolzendahl and Myers Citation2004). During the same period, these countries have also become major destinations for immigration, attracting individuals from countries with far more unequal institutional arrangements between men and women, where more conservative attitudes towards gender roles prevail (Norris, and Inglehart Citation2012). A major concern regarding the integration of immigrants and their children is the extent to which they will adopt the prevailing egalitarian views of their host countries, or if they will stick with the more traditional gender roles of their countries of origin. This is particularly evident in Scandinavia, where gender equality has been a key policy goal for decades, and where welfare models rely on high levels of female employment (Kavli Citation2015). Attitudes to gender roles and women’s societal roles have become one of the most contested topics in debates about immigration and integration. This is particularly the case when considering Muslims, who are often perceived as more culturally conservative compared to other religious groups (Ponce Citation2017). As the proportion of immigrants and their descendants is anticipated to rise, commentators frequently caution that immigration, especially from Muslim-majority countries, might threaten to reverse hard-earned progress in achieving greater gender equality (Farris Citation2017; Yilmaz Citation2015). To what extent immigrants will adapt their attitudes to the prevailing institutional and normative context of their receiving societies is, thus a key question for the future of in today’s multi-ethnic Europe.

The academic literature provides two contrasting perspectives on immigrants’ attitudes towards gender roles. Some argue that gender norms are deeply rooted and relatively stable over time and across generations and that immigrants therefore will most likely hold on to the cultural views prevailing in their countries of origin (Kretschmer Citation2018). Other scholars argue that immigrants, influenced by the institutional context and prevailing attitudes among their peers, tend to adopt attitudes that increasingly align with those of the native population in their host countries over time (Breidahl and Larsen Citation2016). Empirical studies examining immigrants’ attitudes towards gender roles often focus on Muslim immigrants, who typically originate from countries with high gender inequality and exhibit gender-related practices that on average tend to be more conservative than both natives and non-Muslim immigrants (Norris, and Inglehart Citation2012; Pessin and Arpino Citation2018). However, the lasting effects of how the norms and institutional context in both sending and receiving countries shape gender norms among immigrants and their descendants has proven to be difficult to disentangle. One reason is that different European immigration-receiving countries differ widely with respect to their actual levels of gender inequality, often associated with distinct welfare state models (Esping-Andersen Citation1990). Whereas the traditionally social democratic Scandinavian countries stand out with exceptionally high levels of gender equality, countries with more liberal welfare models such as the UK and Ireland, as well as continental welfare states including Germany, Austria and the Netherlands, tend to maintain a more traditional and unequal gendered division of labour (Arts and Gelissen Citation2002; Esping-Andersen Citation2009; Hemerijck Citation2012; Korpi, Ferrarini, and Englund Citation2013). Adapting to European norms and institutions regarding gender thus means very different things depending on the country of settlement. Even larger variations in institutions and norms concerning gender are observable among different immigrant sending countries, and different immigrant groups arrive in host countries with markedly different cultural background in relation to gender roles (Inglehart, Norris, and Welzel Citation2003). Furthermore, it is important to consider that immigrant populations across Europe differ considerably in their composition, following different historical patterns of immigration. Thus, when comparing immigrants in different countries, it is difficult to know if differences should be attributed to disparities in the context of reception or to cultural differences among different origin groups.

One option is to focus on groups that are found across many different countries of settlement, but this often results in small sample sizes, missing data or relying on immigrants from a single origin country. Consequently, due to these challenges, empirical research has come up with rather conflicting findings. Studies that compare various immigrant groups living in the same country often conclude that cultural background plays a significant role, as attitudes tend to differ among different immigrant groups (Fernández and Fogli Citation2009; Blau Citation2015). Conversely, research comparing immigrants in different host countries, often conclude that institutional context of reception matters most since immigrants’ attitudes tend to vary depending on where they have settled (Breidahl and Larsen Citation2016; Kitterød and Nadim Citation2020). Some studies have tried to disentangle the effect of sending country and host country using large-scale surveys covering several European countries, such as the European Social Survey (ESS). For example, Röder and Mühlau (Citation2014) discovered that immigrants originating in countries with highly inegalitarian gender relations tend to support gender equality less than the majority in the host countries. They also found that acculturation plays a significant role, both within the first generation and across subsequent generations. Similarly, Pessin and Arpino (Citation2018) observed that adult immigrants tend to hold gender attitudes more closely aligned with gender culture of their country of origin, while attitudes among second-generation immigrants and child migrants are more positively associated with the gender ideology of the destination country. However, these studies are limited by the fact that the ESS have relatively small immigrant samples, which tend to suffer from low response rates and selective attrition, largely excluding immigrants with low education and limited skills in the host country language (Beullens et al. Citation2018).

In this study, we try to overcome these methodological difficulties in several ways. First, we use pooled data from the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in 4 EU countries (CILS4EU) and the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Norway (CILS-NOR) which both were conducted within school settings and provide large samples of immigrant and non-immigrant adolescents with relatively high response rates. Covering five European countries with very different norms and policies regarding gender roles – Norway, Sweden, the UK, Germany and the Netherlands – these data provide ample opportunity to compare adolescents living in countries with very different gender regimes. Second, to disentangle the effects of institutional context in origin countries, we use data from three different international rankings of gender inequality (the UN Gender Inequality Index, which covers 162 countries; OECD’s Social Institutions and Gender Index, covering 180 countries; and World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report, which covers 156 countries) (Barnat, MacFeely, and Peltola Citation2019). By doing so, we compare immigrant origin youth, not from the same countries, but from countries with a similar level of gender inequality. We focus on adolescents, who are in a formative stage in terms of attitude formation, and by comparing those who have migrated themselves with those who are born in the country of settlement to immigrant parents, to assess the impact of exposure to the European context. Moreover, we explore the role of educational resources and religion as mediating factors.

The overall research question is: To what extent are attitudes towards gender roles among immigrant-origin youth shaped by the institutional context of their parental countries of origin and the countries of settlement where they grow up? Additionally, we explore how these attitudes may be mediated by factors such as generational status, educational resources and religion.

The article proceeds as follows: After this introduction we discuss theoretical perspectives on the development, stability and transformation of attitudes regarding gender roles among immigrants and their descendants. We also consider the role of other mediating factors such as educational resources and religious beliefs. Subsequently, we present the study design, followed by description of the data material and methods used. The empirical findings are then presented before we discuss the overall interpretations and implications. In short, we conclude that immigrant origin youth in Europe to a considerable extent adapt their gender attitudes to the prevalent norm in their countries of settlement. At the same time, however, levels of gender inequality in countries of origin also have a lasting impact on attitudes to gender equality among the children of immigrants. Moreover, we find that while education plays a role by being associated with more liberal values, religious beliefs – and among Muslims in particular – contribute significantly to the preservation of conservative attitudes towards gender roles among immigrants and their descendants.

Theoretical perspectives on stability and change in immigrants’ gender attitudes

The theoretical literature from several academic fields points towards rather different conclusions as to what extent attitudes towards gender among immigrants are shaped by the institutional context of their countries of origin or their countries of residence, as well as the role of educational resources and religion in the formation and transmission of gender beliefs.

Institutional context in sending and receiving countries

Institutional theory tells us that social attitudes among individuals in a society are closely related to institutional arrangements at the macro level (Ferrarini Citation2006; Korpi, Ferrarini, and Englund Citation2013; Kangas and Rostgaard Citation2007; Pfau-Effinger Citation2017). In broad terms, institutions may be defined as symbolic blueprints guiding relationships between different roles – inscribed in formal laws, regulations and codes of conduct, or as informal conventions and norms – which reflect and reproduce social structures and power relations in society (Portes Citation2010; Kenny Citation2007). Attitudes to gender roles in a population thus tend to be closely associated with the wider system of economic, social, cultural, and political structures that sustain distinctive gender roles. The European comparative welfare state literature commonly distinguishes between three different types of welfare regimes, associated with three different types of gender systems; a liberal, market-based regime, found in the UK, Ireland and North America; a familial and conservative regime, typically found in continental Europe, such as Germany, the Netherlands and France; and a universalist social democratic regime, found in Scandinavia (Esping-Andersen Citation1990). In the conservative regime, there is a strong impetus to maintain the traditional male breadwinner model. Family benefits discourage women from joining the labour force and kindergartens and childcare services are underdeveloped since the state only intervenes once the traditional family is uncapable of providing care. In the social democratic welfare regime, on the contrary, family benefits encourage female employment, and the extensive provision of childcare services is part of an explicit policy designed to relieve the family unit and create a dual-breadwinner model and full employment (Sainsbury Citation1994, Citation2001; Pfau-Effinger Citation2005). Survey data show that public attitudes towards gender issues are largely consistent with these welfare regimes. The most liberal attitudes to gender roles are found in the Scandinavian countries, and the most conservative attitudes are found in Continental (and Southern) Europe, with the UK somewhere in the middle (Guo and Gilbert Citation2012).

However, institutional theory offers two very different accounts of the relationship between institutional arrangements and individual attitudes. The cultural perspective sees society's institutions as a function of deep-rooted norms and values (Blau, Kahn, and Papps Citation2011). People’s work-family orientations are perceived to be embedded in cultural norms and values regarding motherhood, child-caring and gender roles, and differences in arrangements such as parental leave and kindergartens may be explained by differences in public norms and values (Budig, Misra, and Boeckmann Citation2012; Pfau-Effinger Citation2006). In contrast, institutional perspectives relying on interest-based explanations focus on how people tend to adapt their behaviour and preferences to the institutional opportunity structure. For example, Breidahl and Larsen (Citation2016) and Knudsen and Wærness (Citation2007) argue that individual orientations regarding gender roles and work-family arrangements are dependent on how welfare state institutions allow women to reconcile the conflict between family responsibilities and labour market participation. High female labour market participation and strong norms of gender equality in the Scandinavian countries are thus a result of how the Nordic welfare states both freed women from domestic care responsibilities and offered employment opportunities through the expansion of welfare state institutions like kindergartens and nursing homes (Esping-Andersen Citation1990, Citation2009; Korpi, Ferrarini, and Englund Citation2013). For immigrants and their children, institutional theory thus provides two rather different predictions regarding the relative importance of institutional context in origin and destination countries. Whereas the cultural perspective suggests that attitudes will remain relatively stable after migration, interest-based explanations would suggest that immigrants and their children will be much quicker to adapt their preferences to the opportunity structures of their countries of settlement.

Similarly, opposing predictions can be drawn from the literature on the formation and change in attitudes from social psychology. When studying the influence of origin country norms and institutions on the children of immigrants, the transmission of values is likely to happen indirectly, through socialisation in the family. Such transmission is key to the persistence hypothesis, which argue that attitudes are primarily formed through socialisation processes early in life, and that they are relatively resistant to later influences (Miller and Sears Citation1986; Sears and Funk Citation1999). Attitudes among immigrants and their children should thus continue to conform to the attitudes prevalent in their countries of origin, long after migration to more gender equal societies. Several studies of the so-called second generation argue that the foundations of gender attitudes are modelled on the gendered division of labour within one’s own family, with parents serving as role models and communicating their values and preferences to their children (McHale, Crouter, and Whiteman Citation2003, Maliepaard and Alba Citation2016). The intergenerational transmission of gender attitudes has been shown to be surprisingly resilient during the transition to adulthood, and once formed, the argument goes, these attitudes will remain stable and in turn be passed on to the next generation (Davis and Greenstein Citation2009, Platt and Polavieja Citation2016).

In contrast, the revisionist hypothesis argues that social pressures continue to influence people’s attitudes throughout the life course. For example, Huckfeldt and Sprague (Citation1995) argue that although primary socialisation is important for attitude formation, individuals are also influenced from neighbourhoods, schools, and their broader environment. This implies that prevailing norms in the host society over time may influence attitudes among immigrants and their children, if they are sufficiently exposed. From an ecological perspective, development of ideas about gender is situated within a set of microsystems and macrosystems, beginning with childhood socialisation in a familial culture that reflects the internalised gender dispositions and larger structural and cultural contexts experienced by parents (Bronfenbrenner Citation1986). Adolescents are particularly interesting to study because they are exposed both to their parents and their values through primary socialisation, as well as to secondary socialisation agents like peers, education system, media, etc., which becomes increasingly important as children come of age (Crouter et al. Citation2007; Davis Citation2007). In the case of immigrant youth, these different socialisation agents are likely to transmit competing values and norms (e.g. Kretschmer Citation2018; Idema and Phalet Citation2007; Maliepaard and Alba Citation2016). A number of previous studies have therefore suggested that origin country influences over time lose their significance on attitudes among the second generation in Europe (see, e.g. Röder and Mühlau Citation2014; Pessin and Arpino Citation2018).

Following predictions drawn from the cultural perspective in institutional theory, as well as the persistence hypothesis from social psychology, we expect that gender attitudes among immigrant youth remain strongly influenced by the norms and institutions in their countries of origin, as they are transmitted by their parents and ethnic communities through primary socialisation. However, following the interest-based perspective in institutional theory, or the revisionist hypothesis from social psychology, we expect that their attitudes adapt to the institutional context and prevailing attitudes in their host countries through secondary socialisation. We may thus formulate two competing, although not mutually exclusive, hypotheses:

H1: Children of immigrants from countries with high levels of gender inequality have more conservative attitudes towards gender roles, not just compared to their native origin peers, but also compared to children of immigrants from less gender unequal countries of origin.

H2: Children of immigrants who are settled in social democratic welfare states such as Norway or Sweden have more liberal attitudes towards gender roles than children of immigrants settled in liberal welfare states such as the UK, who in turn have more liberal attitudes than children of immigrants settled in conservative welfare states such as Germany or the Netherlands.

Generational status and educational resources

Changes in attitudes are necessarily gradual, and different theories can shed light onto how attitudes towards gender roles are shaped by how immigrants and their children are positioned within the broader social structure.

Theories of immigrant assimilation give rise to somewhat conflicting expectations regarding how migration and exposure to the host society influence the attitudes of immigrants and their children over time. Both classical and more recent versions of assimilation theory predicts that immigrants – and in particular their children – will become more similar to their host societies’ majority populations as they integrate into the different arenas of social life, both as a result of exposure and as a result of changing interest-structure (Gordon Citation1964; Alba and Nee Citation2009). Other perspectives, such as segmented assimilation theory, on the other hand, suggest that not all immigrant groups manage to integrate and that some children of immigrants may be compelled to reject the values and identities of the majority and stick with those of their parents, or even form ‘reactive’ identities and values opposed to those of the majority (e.g. Portes and Zhou Citation1993; Portes, Fernandez-Kelly, and Haller Citation2005). Because these processes unfold over time and across generations, the litmus test of whether exposure to the host society time will lead immigrants and the majority to blend, or if ethnic differences will become more entrenched over time, is whether the so-called second generation, who are born in the country of settlement, is more similar to natives than those who have immigrated.

Although (neo-)classical and segmented assimilation theory differ in their predictions regarding the role of exposure over time, both stress that the integration process is closely related to class resources, and that children of highly educated immigrants more easily will adapt to the cultural mainstream in their countries of settlement compared to children of low educated immigrants. Educational and class resources may not just be a function of the parents’ level of education or other resources, but may be expressed through the students own achievements in school in terms of school grades – a key resource that can determine their further opportunities in the educational system and beyond. Such as pattern is consistent with both interest-based and exposure-based explanations since education is associated with both increased exposure to ideas about gender equality as well as an interest-structure with more to gain from gender equality. According to interest-based explanations, people’s attitudes towards gender equality depend on whether they are likely to benefit from it, so that women, for example – and in particular highly educated women – are more likely to support gender equality because they have more to gain from it (Bolzendahl and Myers Citation2004). Exposure-based explanations, on the other hand, focus on how people’s attitudes are shaped ideas and situations which they encounter in their daily lives, and argues that highly educated people will be more in favour of gender equality not simply because they have more to gain from it but because they have been exposed to ideas about gender equality through their educations (Ibid.). Although highlighting different mechanisms at play, both perspectives imply that attitudes towards gender roles among immigrants and their children will be shaped by generational status, class and gender.

Educational resources also play an important role in Inglehart’s (Citation2018) existential security thesis, which claims that high standard of living, and thus high levels of existential security, make people more likely to adopt liberal attitudes. This means that poor countries with weak institutions tend to be characterised by high levels of gender inequality, and that immigrants from highly gender unequal countries also tend to have fewer educational resources. Differences in the level of such educational and class resources may thus be important for explaining the link between institutional context in the parental countries of origin and attitudes to gender roles among immigrants and their children – meaning that the gender conservatism of immigrants and their children originating in gender conservative countries is associated with low levels of educational and class resources rather than an effect of cultural transmission.

Based on these theoretical arguments, we may put forth another three hypotheses about the role of exposure and educational resources:

H3: Children who are born in the country of settlement to immigrant parents have more liberal attitudes towards gender roles than those who have immigrated as children themselves.

H4: Immigrant origin youth who have parents with higher levels of education and who have better school grades have more liberal attitudes towards gender roles than those who have parents with lower levels of education and who have lower grades in school.

H5: Once we introduce parental education and school achievements, the effect of gender inequality in the parental country of origin is substantially reduced.

The role of religion

Most world religions are concerned with regulating the reproductive sphere, usually by linking notions of gender, and female sexuality in particular, to symbolic distinctions between sacred and profane and to ritual norms of purity and impurity, which in turn are used to legitimise unequal relationships between men and women (Diehl, Koenig, and Ruckdeschel Citation2009; Brinkerhoff and MacKie Citation1985). Studies have found that Muslim immigrants in Europe have more conservative gender beliefs compared to both natives and non-Muslim immigrants (Diehl, Koenig, and Ruckdeschel Citation2009; Lewis and Kashyap Citation2013). One explanation for this observed conservatism among Muslims is linked to specific Islamic doctrine and practices which encourage non-egalitarian gender practices (Inglehart, Norris, and Welzel Citation2003; Diehl, Koenig, and Ruckdeschel Citation2009; Kalmijn and Kraaykamp Citation2018). Another explanation is that Muslims are more gender conservative because they on average are more religious than native Christians (see Friberg and Sterri Citation2021 for data from Norway), and because highly religious people tend to have more conservative gender role attitudes, regardless of religious denomination (Simsek, Fleischmann, and van Tubergen Citation2019; Diehl, Koenig, and Ruckdeschel Citation2009; Röder Citation2014; Ng Citation2022). Religion has been found to have a strong intergenerational persistence and is strongly transmitted within immigrant families (Jacob and Kalter Citation2013; Jacob Citation2020), and religion and religiosity can therefore be an alternative explanation for the link between institutional context in the parental countries of origin and attitudes among children of immigrants. By distinguishing between religious affiliation and religious salience, and by examining what happens to the effect of gender inequality in the parental country of origin once we introduce religion and religiosity, we may thus formulate another three hypotheses:

H6: Children of immigrants who identify as Muslims have more conservative attitudes to gender roles than children of immigrants who identify with other religions.

H7: Children of immigrants who report that religion is very important in their lives have more conservative attitudes to gender roles than children of immigrants who report that religion is not very important in their lives.

H8: Once we introduce religion and religiosity to the analyses, the effect of gender inequality in the parental country of origin is substantially reduced.

Finally, we expect immigrant origin girls – who have more to gain from gender-liberalation, and likely have been more exposed to discriminatory practices – to have more liberal attitudes towards gender roles (Idema and Phalet Citation2007).

H9: Among children of immigrants, girls have more liberal attitudes to gender roles than boys.

Data, methods, and measures

Data

The data for our analyses was pooled from the CILS4EU and the CILS-NOR studies, covering five European countries. The large sample size provides us representative data, suitable for exploring the various types of welfare states and the diverse levels of institutional gender equality. Both studies were inspired by the US CILS survey (see Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001), but unlike the original, they also include youth from non-immigrant backgrounds, to enable cross-group comparisons. The CILS4EU study first collected in-school questionnaire data from almost 20,000 adolescents in 2010/2011, aged 14–15 years at the time, in England, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden (N ≈ 5000 per country). Subsequently, two follow-up surveys – one in 2012 and one in 2013 – were conducted while the students were still in school (CILS4EU Citation2016). The much smaller CILS-NOR survey was conducted in 2016, when the students were approximately 16 years old. The questionnaires used in both studies were partially overlapping, allowing us to compare the students’ responses to various items. In the CILS-NOR study and the Swedish part of the CILS4EU, questionnaire data was linked with administrative register data. In the present study, we have pooled data from the CILS-NOR study with the second wave of the CILS4EU data, which was collected in 2012, because at that time the students were of similar ages (around 16 years). Nevertheless, it is notable that there was a four-year gap between the studies, which merits some caution when comparing Norway to the other four countries. presents the distribution of immigrants within the sample from each country, along with the five largest groups categorised by their country of origin.

Table 1. Distribution of immigrant backgrounds in each host country.

Methods

Comparing immigrants in different European countries poses a challenge because European countries are home to diverse immigrant groups originating from countries with substantial variations in terms of their economic, cultural, and institutional contexts. When we compare immigrants as a broad category in different countries, it is not clear whether differences should be attributed to disparities in the context of reception or to differences in the distribution of various immigrant groups across countries. The diversity in the distribution of countries of origin within our samples might illustrate this challenge. While some origin groups, such as those from Turkey or Iraq, are among the top five in two or three countries, no origin groups are among the top five across four or five countries. And many of the largest groups within each country of settlement are only found in one country, such as Surinam in the Netherlands, Russia in Germany, India, Bangladesh, and Jamaica in the UK, or Lebanon in Sweden. As a result, it is difficult to fully control for the effect of origin country when trying to compare attitudes among children of immigrants across different countries of settlement.

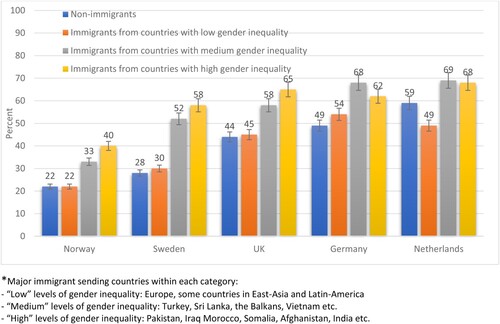

In the current analyses, we try to solve this problem by not comparing immigrants from the same origin countries, but by comparing immigrants from sending countries with similar levels of gender inequality. The idea is that if we can identify sending countries that are relatively similar in terms of gender inequality, and we can control for the effect of origin country, despite cross-country variations in origin country groups. We approached this in two steps. First, in a descriptive analysis showing the absolute distribution of students’ preference for traditional gender roles across the five countries of settlement. This analysis included both natives and immigrant youth originating in countries with different levels of gender inequality (). Next, we employed a stepwise logistic regression with the preference for traditional gender roles as a dependent variable. This allowed us to observe how the effects of parental origins and country of settlement change when new factors are considered. In the first step, we used country of residence and level of gender inequality in the parental country of origin as independent variables, while adjusting for gender and immigrant generation. In Model 2, we added two independent variables, the parental education and the students’ own grades in the host country language. Consequently, we added religious affiliation in Model 3 and religious salience in Model 4. Out of a total of 23,465 immigrant and non-immigrant respondents from the 5 countries, only 10,808 (46.1%) with an immigrant-related background were included in the regression analyses.

Figure 1. Share who report that they prefer traditional gender roles on at least one out of four items, according to immigration status, country of residence, and level of gender inequality in parental country of origin.

Measures

The dependent variable, preference for traditional gender roles was assessed using a questionnaire battery where the respondents were posed the following question for each item: ‘In a family, who should do the following: [Take care of children/ Cook/ Earn money/ Clean the house]’, with three response options: ‘Mostly the man’, ‘Mostly the woman’ or ‘Both about the same’.Footnote1 We then constructed a dummy variable that identified individuals a preference for traditional gender roles on at least one of the four items (meaning that women should care, cook, and clean, while men should earn). In the total sample, 42% were coded as preferring traditional gender roles.

As independent variables, we first use dummy variables indicating each country of settlement, with Sweden and Norway representing the Scandinavian welfare model, While Germany and the Netherlands represents the conservative or continental welfare model. The UK, representative of the liberal model, was the reference point. To measure the level of gender inequality in parental origin country, we relied on three different global composite indices and their respective country rankings, namely World Economic Forum’s The Global Gender Gap Index (GGI); the UN’s Gender Inequality Index (GII); and the OECD’s Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI). Although these measures differ in their methodology, they all aim to assess the extent to which women and men have equal rights and opportunities across different sectors of society (Barnat, MacFeely, and Peltola Citation2019). Practically every origin country in our samples is covered by at least one of these indices, and most of them are covered by all three (the GGI covers 156 countries, the GII covers 162 countries and SIGI covers 180 countries). We then constructed a variable that accounts for the level of gender inequality in parental origin country, by compiling an average country ranking based on all three gender inequality indices. Initially, we ranked all countries on a scale from 1 to 10 for each of the three global gender inequality indices. Subsequently, we calculated the mean score ranging from 1 to 10 based on the average ranking of their mother’s and father’s countries of birth. Following this, we categorised the sample into three subgroups (1–3 = Low; 4–7 = Medium; 8–10 = High). Among the main sending countries categorised as having relatively low levels of gender inequality, we find most European countries, and some countries in East-Asia and Latin-America. In the ‘medium’ category we find major sending countries like Turkey, Sri Lanka, the Balkans, and Vietnam, while countries categorised as having ‘high’ levels of gender inequality include countries like Pakistan, Iraq, Morocco, Somalia, Afghanistan, and India.

We distinguished the immigrant generations into three categories: first generation as those who are foreign-born and who have immigrated themselves; second generation, as native born with two immigrant parents; and mixed origin as individuals with one foreign-born and one native-born parent.

The variable, parents’ highest level of education, was constructed and categorised as primary, secondary and university educations, based on the highest educational level achieved by the parent with the most education. The variable, school grades in host country language, was generated to indicate whether the student’s grade fell within the upper 50% of the national average, with the lower 50% serving as the reference category. Religious affiliation was categorised into subgroups: ‘Christianity’, ‘Islam’, or ‘Other religion’ (included Hinduism, Buddhism, or Judaism), with ‘No religion’ serving as the reference category. Religious salience was measured by asking participants: ‘How important is religion to you?’. The responses were categorised into four levels, with ‘not at all important’ as the reference point for ‘not very important’, ‘fairly important’, and ‘very important’ responses .

Table 2. Variables used in regression. Immigrant origin respondents only.

Results

Descriptive analyses

shows the percentage of respondents who reported a preference for traditional gender roles on at least one out of four indices. It compares native-origin youth with immigrant youth originating from countries with low, medium, and high levels of gender inequality across each of the five European countries of settlement. Three distinct patterns are noticeable in this figure. First, it illustrates that native or non-immigrant-origin youth in the five different countries under study exhibit significantly varied attitudes towards gender roles. These differences align with our expectations based on the distinct welfare state models and institutional contexts.

Among native-origin youth in Norway and Sweden, representative of the Scandinavian model, the vast majority preferred an equal sharing of responsibilities between men and women regarding childcare, cooking, cleaning, and earning money. Only a minority among native adolescents in these countries (22% and 28%) reported a preference for a traditional gendered division of labour on at least one out of four items. In contrast, around half or more among native origin youth in Germany and Netherlands report a preference for traditional gender roles on at least one item (49% and 59% respectively). Second, there are substantial differences depending on immigration origin. In all five countries of settlement, immigrant youth originating from countries with high levels of gender inequality have substantially more conservative attitudes to gender roles than those from countries with lower levels of gender inequality. Whereas minority youth from countries with low levels of gender inequality report similar attitudes as native youth (the exception being in the Netherlands, where immigrants from countries with low gender inequality are in fact more liberal than natives), immigrant minorities originating in countries with medium or high levels of gender inequality tend to report significantly more conservative attitudes than natives. The third, and perhaps most striking pattern, is that the differences between immigrant origin youth from similar countries of origin to a large extent follows differences between natives in their respective contexts of settlement. Whether originating from countries with high, medium, or low levels of gender inequality, those who are settled in Scandinavia hold far more egalitarian attitudes than their counterparts who reside in the UK, who in turn hold more egalitarian attitudes than those living in Germany or the Netherlands.

Multivariate analyses

To explore the relationship between the parental country of origin and the context of settlement further, and to test the role of generational status, parental education, grades, religion and religiosity, and gender, we perform a four-step logistic regression analyses, with preferring traditional gender roles as the dependent variable (see ). In these analyses, we only include adolescents with an immigrant background, and exclude all respondents with native-born parents.

Table 3. Stepwise logistic regression. Preference for traditional gender roles as dependent variable.

Model 1 confirms that both country of residence and the level of gender inequality in the parental country of origin have a significant effect upon the likelihood for expressing a preference for traditional gender roles. Compared to those living in the UK, immigrant origin youth living in Germany and the Netherlands exhibit a 63% and 34% higher likelihood, respectively, of preferring traditional gender roles on at least one item. Living in Sweden, and even more so in Norway, on the other hand, significantly decreases the likelihood of reporting a preference for traditional gender roles, by as much as 96% and 45% respectively. At the same time, we find a strong significant relationship between the level of gender inequality in the country of origin and the attitudes towards gender roles among the children of immigrants. Adolescents with immigrant parents born in countries with medium and high levels of gender inequality are 46% and 64% more likely to prefer traditional gender roles compared to immigrant adolescents originating in countries with relatively low levels of gender inequality. We also find a significant effect of exposure, measured in terms of generational status. Compared to adolescents who have immigrated themselves, native-born children of two immigrant parents are 17% less likely to prefer traditional gender roles. Adolescents of mixed origin are as much as 61% less likely to prefer traditional gender roles.

Introducing the parents’ level of education and the students’ grades in the host country language in Model 2, we find that those who have parents with secondary education as their highest completed education are 20% less likely to prefer traditional gender roles compared to those with parents whose highest level of education is primary education, whereas those with at least one university-level educated parent are 33% less likely to prefer traditional gender roles. The students’ own grades in the host country language also have a significant effect, as those with grades in the upper 50% of student distribution are 32% less likely to prefer traditional gender roles compared to those with grades in the lower 50% of the distribution. Introducing the parents’ educational level and the students’ grades in the host country language does not change the effect of cultural origins in terms of the level of gender inequality in the parental country of origin, indicating that the origin country effect is not a result of immigrants from gender conservative countries having limited educational resources.Footnote2

Model 3 and 4 introduces religious affiliation and religious salience, which both, as expected, has a large impact on attitudes to gender roles. While self-declared Christians and those belonging to other religions have a 40% and 48% higher likelihood of preferring traditional gender roles, respectively, compared to non-affiliated youth, Muslim youth’s likelihood of preferring traditional gender roles is 106% higher. However, religious salience also has a strong effect on attitudes to gender roles, regardless of what religion one belongs to. Compared to those who report that religion is ‘not at all important’, those who say that religion is ‘fairly important’ are 41% more likely to prefer traditional gender roles, while those who say that religion is ‘very important’ are 89% more likely to prefer traditional gender roles. Importantly, the effect of being Muslim is reduced from a 106% to a 52% increase in likelihood of preferring traditional gender roles once we introduce religious salience, indicating that Muslim adolescents’ higher level of gender conservatism is partially explained by their much higher average level of religiosity. Finally, when controlling for gender, we find that girls, as expected, in all five models are more than 90% less likely to prefer traditional gender roles than boys.

Discussion

Gender roles have become a core symbol of the supposed cultural divide between Western Europe and its growing immigrant population, and Muslims in particular are often described as a challenge to progressive European values of gender equality (Van Klingeren and Spierings Citation2020). Many immigrant-sending countries indeed have higher levels of gender inequality, and to what extent immigrants and their children over time will adapt their attitudes to the context of reception or remain shaped by the context of origin or is therefore of considerable interest. Existing research has presented two rather contrasting views regarding how attitudes will adapt over time. Whereas some find that conservative attitudes to gender remain resistant to change and continue to be transmitted from the immigrant generation to their children (Diehl, Koenig, and Ruckdeschel Citation2009; Kretschmer Citation2018), others find that their views over time tend to conform to the host country context (Breidahl and Larsen Citation2016; Kitterød and Nadim Citation2020). What is often missing in these debates is the rather large differences between the various European societies to which immigrants must adapt. These differences would ideally provide researchers with the opportunity to test the relative significance of cultural origins and receiving context, but this opportunity has been thwarted by the different composition of immigrant populations across Europe, making it almost impossible to simultaneously control for the effects of both origins and destinations. In this article, we try to overcome this problem by comparing immigrant origin youth, not from the same countries but from countries with similar levels of gender inequality, living in different host countries, using school surveys with large immigrant samples from five different European countries, combined with information from three different global indexes measuring gender inequality in sending countries across the world. The results provide support for both cultural persistence and adaptation.

Our first hypothesis was based on the cultural perspective in institutional theory, as well as the persistence hypothesis from social psychology, and stated that children of immigrants from countries with high levels of gender inequality have more conservative attitudes towards gender roles, not just compared to their native peers, but also compared to children of immigrants from more gender equal backgrounds. This hypothesis finds strong support in our analyses, indicating that cultural origins, shaped by the level of gender inequality in the parental country of origin, continues to play a major role in the formation of attitudes to gender roles among immigrant origin youth.

But this is only half the story. Our second hypothesis, drawn from interest-based perspectives in institutional theory and the revisionist hypothesis from social psychology, stated that children of immigrants who are settled in social democratic welfare states such as Norway or Sweden have more egalitarian attitudes towards gender roles than children of immigrants settled in liberal welfare states such as the UK, who in turn have more egalitarian attitudes than children of immigrants settled in continental welfare states such as Germany or the Netherlands. This hypothesis also finds strong support in our analyses. In fact, the most conservative immigrant groups living in Scandinavia on average have quite similar attitudes to gender roles as natives in Germany and the Netherlands. This host country effect remains robust after controlling for all the other variables in our models, and thus seems to be unrelated to variations in educational resources or religion.

Perhaps surprisingly, we find significant differences also between the Scandinavian countries, as immigrant origin youth in Norway have more egalitarian gender beliefs than their counterparts in Sweden. It should be noted that caution is warranted when interpreting these results, as the sample design was not entirely uniform across Norway and the other countries. It is likely, however, that our result reflects real differences in the societal context of integration, and one plausible explanation is the much higher level of ethnic segregation in Sweden than in Norway (see Rogne et al. 2020), which we expect to reduce acculturation pressure.

Based on assimilation theory and the expectation that exposure to the host country context over time leads to more egalitarian attitudes, our third hypothesis stated that children who are born in the country of settlement to immigrant parents have more egalitarian attitudes than those who have immigrated as children. This hypothesis is also supported by the evidence. The effect of generational status is smaller than that of both cultural origins and context of settlement, but this is unsurprising given that we only measure synthetic generations within a same-age youth sample. However, the effect is robust across all models, suggesting that exposure has an impact, regardless of changes in educational resources, language skills or religiosity. Not surprisingly, we also find that mixed-origin youth have substantially more egalitarian attitudes.

Our fourth hypothesis focused on the role of educational resources and stated that immigrant origin youth who have parents with higher levels of education and who have better school grades have more egalitarian attitudes towards gender roles than those who have parents with lower levels of education and who have lower grades in school. This hypothesis – which is drawn from both assimilation theory and the existential security thesis – is also supported by our findings, suggesting that increasing educational attainments leads to more egalitarian norms. Our fifth hypothesis, however – which stated that once we introduce parental education and school achievements, the effect of gender inequality in the parental country of origin is substantially reduced – is not supported by the evidence. This hypothesis was based on the notion that the observed origin country effect is due to immigrants from gender conservative countries having fewer educational resources. This does not appear to be the case, suggesting that the origin-country effect has more to do with cultural transmission than (lack of) education.

This is confirmed when we introduce religion to the analyses. As we expected from hypothesis 6, the analyses show that immigrant origin youth who identify as Muslim have more conservative attitudes to gender roles not just compared to non-affiliated youth, but also compared to those who identify as Christians or with other religions. This conservatism can partly be attributed to their Muslim faith, and partly be attributed to their substantially higher levels of religiosity, as expected from hypothesis seven. Importantly, once we introduce religion and religiosity to the analyses, the effect of gender inequality in the parental country of origin is substantially reduced, as predicted by hypothesis eight. This suggests that religiosity in general – and Muslim religiosity in particular – is a key factor in the transmission of conservative gender norms within immigrant families and communities, although this may also be a result of 'reactive identities' (see Portes and Rumbaut 2001) among muslim youth who feel alienated from their majority surroundings. Finally, the analyses show that girls, as expected, have more liberal attitudes to gender roles than boys, but this appears to be unrelated to the other factors in the analyses.

Current debates on diversity and multiculturalism in Europe tend to be divided between those who downplay the significance of cultural differences between immigrants and natives on the one hand, and those who argue that these differences are both significant and unchangeable. All in all, our results indicate that neither perspective holds true. By identifying a robust effect of the level of gender inequality in the parental country of origin on the attitudes of immigrant origin youth, we show that cultural origins – shaped by the institutional context of sending countries – continues to play a major role in shaping attitudes in subsequent generations. Moreover, we show that religion is an important mediating factor in the transmission of these attitudes. However, between-country differences in average attitudes to gender roles among both native and immigrant origin youth, especially between Scandinavia and continental Germany and the Netherlands, are even larger than those between natives and immigrants. This suggests a considerable degree of adaptation to the institutional and cultural context of their host societies. Our analyses cannot identify the mechanisms through which these adaptations take place. In Scandinavia, the state provides free childcare and rewards two-income families, and progressive attitudes towards gender roles are common in the general populations, whereas in continental Europe, institutional arrangements are more geared towards a traditional male breadwinner model and attitudes in the general population are far more conservative. We cannot discern the exact mechanisms through which this adaptation takes place, as people may adapt their ideals to the opportunity structures and institutional contexts where they live, or their beliefs may have been shaped by normative pressures from their surroundings. Future research should focus on exploring the mechanisms through which these adaptations take place, as well as how these adaptations interact with the cultural transmission of gender attitudes stemming from the origin country which appear to be strongly mediated through religion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 On every item, a substantial minority of the total sample reported to prefer traditional gender roles. For cooking, earning and cleaning, the share was between 30% and 40% in Germany, UK and the Netherlands, and between 15% and 25% in Norway and Sweden. For taking care of children, the number was slightly lower, plus/minus 15% in UK, Germany and the Netherlands, and plus/minus 10 percent in Norway and Sweden. On each item, most respondents chose ‘both about the same’ while the share who reported to prefer ‘untraditional’ gender roles (mostly the man to either cook, clean and take care of the children, or mostly the woman to earn money) was negligible in all five countries.

2 Note that the effect of Germany is somewhat reduced, suggesting that part of the particular gender conservatism among immigrant youth in German is related to lower education levels and weaker school performance in the German immigrant population.

References

- Adrian Farner Rogne, Eva K. Andersson, Bo Malmberg, and Torkild Hovde Lyngstad. 2020. “Neighbourhood Concentration and Representation of Non-European Migrants: New Results from Norway.” European Journal of Population 36: 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-019-09522-3.

- Alba, R. D., and V. Nee. 2009. Remaking the American Mainstream. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Arts, W., and J. Gelissen. 2002. “Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism or More? A State-of-the-art Report.” Journal of European Social Policy 12 (2): 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952872002012002114.

- Barnat, N., S. MacFeely, and A. Peltola. 2019. “Comparing Global Gender Inequality Indices: How Well Do They Measure the Economic Dimension?” Journal of Sustainability Research 1 (e190016): 1–33. https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20190016.

- Beullens, K., G. Loosveldt, C. Vandenplas, and I. Stoop. 2018. “Response Rates in the European Social Survey: Increasing, Decreasing, or a Matter of Fieldwork Efforts?” Survey Methods: Insights from the Field. https://surveyinsights.org/?p=9673.

- Blau, F. D. 2015. “Impact of Internal Migration on Political Participation in Turkey.” IZA Journal of Migration 4 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40176-014-0025-4.

- Blau, F. D., L. M. Kahn, and K. L. Papps. 2011. “Gender, Source Country Characteristics, and Labor Market Assimilation among Immigrants.” Review of Economics and Statistics 93 (1): 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00064.

- Bolzendahl, Catherine, and Daniel Myers. 2004. “Feminist Attitudes and Support for Gender Equality: Opinion Change in Women and Men, 1974–1998.” Social Forces 83 (2): 759–789. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2005.0005.

- Breidahl, K. N., and C. A. Larsen. 2016. “The Myth of Unadaptable Gender Roles: Attitudes Towards Women’s Paid Work among Immigrants Across 30 European Countries.” Journal of European Social Policy 26 (5): 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928716664292.

- Brinkerhoff, M. B., and M. MacKie. 1985. “Religion and Gender: A Comparison of Canadian and American Student Attitudes.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 47: 415–429.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1986. “Recent Advances in Research on the Ecology of Human Development.” In Development as Action in Context: Problem Behavior and Normal Youth Development, edited by R. K. Silbereisen, K. Eyferth and G. Rudinger, 287–309. Springer.

- Budig, M. J., J. Misra, and I. Boeckmann. 2012. “The Motherhood Penalty in Cross-National Perspective: The Importance of Work–Family Policies and Cultural Attitudes.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 19 (2): 163–193. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxs006.

- CILS4EU. 2016. Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Four European Countries. Technical Report. Wave 1–2010/2011, v1.2.0. Mannheim: Mannheim University.

- Crouter, A. C., S. D. Whiteman, S. M. McHale, and D. W. Osgood. 2007. “Development of Gender Attitude Traditionality Across Middle Childhood and Adolescence.” Child Development 78 (3): 911–926.

- Davis, S. N. 2007. “Gender Ideology Construction from Adolescence to Young Adulthood.” Social Science Research 36 (3): 1021–1041.

- Davis, S. N., and T. N. Greenstein. 2009. “Gender Ideology: Components, Predictors, and Consequences.” Annual Review of Sociology 35:87–105. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115920.

- Diehl, C., M. Koenig, and K. Ruckdeschel. 2009. “Religiosity and Gender Equality: Comparing Natives and Muslim Migrants in Germany.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (2): 278–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870802298454.

- Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. 2009. Incomplete Revolution: Adapting Welfare States to Women’s New Roles. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Farris, Sara, R. 2017. In the Name of Women’s Rights: The Rise of Femonationalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Fernández, R., and A. Fogli. 2009. “Culture: An Empirical Investigation of Beliefs, Work, and Fertility.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 1 (1): 146–177. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.1.1.146.

- Ferrarini, T. 2006. Families, States and Labour Markets: Institutions, Causes and Consequences of Family Policy in Post-war Welfare States. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Friberg, J. H., and E. B. Sterri. 2021. “Decline, Revival, Change? Religious Adaptations among Muslim and non-Muslim Immigrant Origin Youth in Norway.” International Migration Review 55 (3): 718–745. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918320986767.

- Gordon, M. M. 1964. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Guo, J., and N. Gilbert. 2012. “Public Attitudes and Gender Policy Regimes: Coherence and Stability in Hard Times.” Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 39:163.

- Hemerijck, A. 2012. Changing Welfare States. Oxford: OUP.

- Huckfeldt, R. R., and J. Sprague. 1995. Citizens, Politics and Social Communication: Information and Influence in an Election Campaign. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Idema, H., and K. Phalet. 2007. “Transmission of Gender-Role Values in Turkish-German Migrant Families: The Role of Gender, Intergenerational and Intercultural Relations.” Zeitschrift für Familienforschung 19 (1): 71–105.

- Inglehart, R. F. 2018. “Modernization, Existential Security, and Cultural Change: Reshaping Human Motivations and Society.” In Advances in Culture and Psychology. Vol. 7, edited by Michele J. Gelfand, Chi-yue ChiuChiu, and Ying-yi Hong. New York: Oxford Academic.

- Inglehart, R., P. Norris, and C. Welzel. 2003. “Gender Equality and Democracy.” In Human Values and Social Change, edited by Ronald Inglehart, 91–115. Leiden: Brill.

- Jacob, K. 2020. “Intergenerational Transmission in Religiosity in Immigrant and Native Families: The Role of Transmission Opportunities and Perceived Transmission Benefits.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (9): 1921–1940. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1515009.

- Jacob, K., and F. Kalter. 2013. “Intergenerational Change in Religious Salience among Immigrant Families in Four European Countries.” International Migration 51 (3): 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12108.

- Kalmijn, M., and G. Kraaykamp. 2018. “Determinants of Cultural Assimilation in the Second Generation. A Longitudinal Analysis of Values about Marriage and Sexuality among Moroccan and Turkish Migrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (5): 697–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1363644.

- Kangas, O., and T. Rostgaard. 2007. “Preferences or Institutions? Work—Family Life Opportunities in Seven European Countries.” Journal of European Social Policy 17 (3): 240–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928707078367.

- Kavli, Hanne. 2015. “Adapting to the Dual Earner Family Norm? The Case of Immigrants and Immigrant Descendants in Norway.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (5): 835–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.975190.

- Kenny, M. 2007. “Gender, Institutions and Power: A Critical Review.” Politics 27 (2): 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2007.00284.x.

- Kitterød, R. H., and M. Nadim. 2020. “Embracing Gender Equality: Gender-Role Attitudes among Second-Generation Immigrants in Norway.” Demographic Research 42:411–440. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2020.42.14.

- Knudsen, K., and K. Wærness. 2007. “National Context and Spouses’ Housework in 34 Countries.” European Sociological Review 24:97–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcm037.

- Korpi, W., T. Ferrarini, and S. Englund. 2013. “Women’s Opportunities under Different Family Policy Constellations: Gender, Class, and Inequality Tradeoffs in Western Countries Re-examined.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 20 (1): 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxs028.

- Kretschmer, David. 2018. “Explaining Differences in Gender Role Attitudes among Migrant and Native Adolescents in Germany: Intergenerational Transmission, Religiosity, and Integration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (13): 2197–2218. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1388159.

- Lewis, V. A., and R. Kashyap. 2013. “Are Muslims a Distinctive Minority? An Empirical Analysis of Religiosity, Social Attitudes, and Islam.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52 (3): 617–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12044.

- Maliepaard, M., and R. Alba. 2016. “Cultural Integration in the Muslim Second Generation in the Netherlands: The Case of Gender Ideology.” International Migration Review 50 (1): 70–94.

- McHale, S. M., A. C. Crouter, and S. D. Whiteman. 2003. “The Family Contexts of Gender Development in Childhood and Adolescence.” Social Development 12 (1): 125–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00225.

- Miller, S. D., and D. O. Sears. 1986. “Stability and Change in Social Tolerance: A Test of the Persistence Hypothesis.” American Journal of Political Science 30 (1): 214–236. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111302.

- Ng, Ka U. 2022. “Are Muslim Immigrants Assimilating? Cultural Assimilation Trajectories in Immigrants’ Attitudes toward Gender Roles in Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (15): 3641–3667. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2031927.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2012. “Muslim Integration into Western Cultures: Between Origins and Destinations.” Political Studies 60 (2): 228–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00951.x.

- Pessin, L., and B. Arpino. 2018. “Navigating between Two Cultures: Immigrants’ Gender Attitudes toward Working Women.” Demogr Res. 2018 Jan-Jun;38:967-1016. Epub 2018 Mar 15. PMID: 29606913; PMCID: PMC5875938 https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2018.38.35.

- Pfau-Effinger, B. 2005. “Culture and Welfare State Policies: Reflections on a Complex Interrelation.” Journal of Social Policy 34 (1): 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279404008232.

- Pfau-Effinger, B. 2006. “Cultures of Childhood and the Relationship of Care and Employment in European Welfare States.” In Children, Changing Families and Welfare States, edited by Jane Lewis, 137–153. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Pfau-Effinger, B. 2017. Development of Culture, Welfare States and Women’s Employment in Europe. Milton Park: Routledge.

- Platt, L., and J. Polavieja. 2016. “Saying and Doing Gender: Intergenerational Transmission of Attitudes Towards the Sexual Division of Labour.” European Sociological Review 32 (6): 820–834. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcw037.

- Ponce, Aaron. 2017. “Gender and Anti-Immigrant Attitudes in Europe.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 3. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023117729970.

- Portes, A. 2010. Economic Sociology: A Systematic Inquiry. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Portes, A., P. Fernandez-Kelly, and W. Haller. 2005. “Segmented Assimilation on the Ground: The New Second Generation in Early Adulthood.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28 (6): 1000–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870500224117.

- Portes, A., and R. G. Rumbaut. 2001. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Portes, A., and M. Zhou. 1993. “The new Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and its Variants.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530 (1): 74–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716293530001006.

- Röder, A. 2014. “Explaining Religious Differences in Immigrants' Gender Role Attitudes: The Changing Impact of Origin Country and Individual Religiosity.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (14): 2615–2635.

- Röder, A., and P. Mühlau. 2014. “Are They Acculturating? Europe's Immigrants and Gender Egalitarianism.” Social Forces 92 (3): 899–928.

- Sainsbury, D., ed. 1994. Gendering Welfare States. Thousand Oakes: Sage.

- Sainsbury, D. 2001. “Gender and the Making of Welfare States: Norway and Sweden.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 8 (1): 113–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/8.1.113.

- Sears, D. O., and C. L. Funk. 1999. “Evidence of the Long-Term Persistence of Adults’ Political Predispositions.” The Journal of Politics 61 (1): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/2647773.

- Simsek, M., F. Fleischmann, and F. van Tubergen. 2019. “Similar or Divergent Paths? Religious Development of Christian and Muslim Adolescents in Western Europe.” Social Science Research 79:160–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.09.004.

- Van Klingeren, M., and N. Spierings. 2020. “Acculturation, Decoupling, or Both? Migration’s Impact on the Linkage between Religiosity and Gender Equality Attitudes.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (15): 3079–3100. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1733947.

- Yilmaz, F. 2015. “From Immigrant Worker to Muslim Immigrant: Challenges for Feminism.” European Journal of Women's Studies 22 (1): 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506814532803.