?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

There is ample evidence that foreigners suffer from discrimination when trying to integrate. Extreme situations, however, can alter the population’s attitude towards foreigners. One example of such an extreme situation is the position of Ukrainians in Poland since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. It drastically changed the composition and share of the foreign-born population in Poland. In this paper, we examined the attitude towards people with Ukrainian-sounding and other foreign-sounding names in Poland, and whether it has changed. We used an experimental approach, within which we contacted amateur football coaches asking to join a trial training session using typical native- and Belarussian-, German-, and Ukrainian-sounding names. Half of the clubs received an additional signal showing support for Ukraine. Furthermore, a limited subset of participants completed post-experiment surveys. The survey gave us an opportunity to understand why the respondents discriminate. The results show that people with foreign-sounding names receive fewer responses. Surprisingly, people with Ukrainian names are the exception. They received more responses than natives. Signaling support for Ukraine had a positive but not statistically significant effect on the response rate.

Introduction

In February 2022, Russia attacked Ukraine and started a war which had far-reaching repercussions. For example, the conflict has had extensive negative economic effects and resulted in a staggering number of human casualties (Liadze et al. Citation2022; McKee and Murphy Citation2022). Millions of Ukrainians had to flee (Kumar et al. Citation2022) and many hoped to return to their home country as soon as possible, migrating to countries close to Ukraine. Bordering Ukraine and being open to Ukrainian refugees, Poland became a preferred destination for many fleeing Ukrainians.

The ongoing armed conflict just outside the Polish border resulted in a large and unprecedented influx of foreigners into Poland. Before the start of the war, the share of the foreign-born population in Poland was around 2.2% (year 2020), the second lowest for all OECD countries and the fourth lowest in the EU (eurostat Citation2023; OECD Citation2023). However, in 2022 the number of foreign-born people dramatically increased. Around 1.5 million Ukrainians sought refugee status in Poland (UNHCR Citation2023), tripling the foreign-born population’s share from 2% to around 6% within a year.

Like other countries, discrimination towards the foreign-born population is an ongoing problem in Poland. Research finds that foreigners in Poland are less likely to get a response when contacting a landlord (Antfolk, Szala, and Öblom Citation2019), when looking for a job (Wysienska-Di Carlo and Karpinski Citation2014), or when trying to integrate through sports (Gomez-Gonzalez, Nesseler, and Dietl Citation2021). Most studies on Poland focus on the time before the start of the war. This sudden change in the composition of Polish society, however, could have a significant influence on the extent of discrimination (Gang, Rivera-Batiz, and Yun Citation2002).

In this paper, we conducted a randomized control trial in which people with typical Polish- or foreign-sounding names want to join an amateur football club. The design is similar to other correspondence tests in, e.g. the labor market or housing (Ahmed and Hammarstedt Citation2008; Auspurg, Hinz, and Schmid Citation2017; Banerjee et al. Citation2009; Bertrand and Mullainathan Citation2004). We used typical foreign-sounding names for the three largest foreign groups in Poland: Belarussians, Germans, and Ukrainians (Gomez-Gonzalez, Nesseler, and Dietl Citation2021). With this approach, we have one measurement showing how open parts of the Polish society are towards foreigners. Joining an amateur sports club is an approximation of social integration and helps newcomers establish a social circle (Nesseler, Gomez-Gonzalez, and Dietl Citation2019). Comparing the response rates, we found that people with a Polish-sounding name are more often invited to a training session than foreigners. However, people with Ukrainian-sounding names are the exception, receiving more invitations than people with Polish-sounding names. In addition, we included a treatment group that showed support for Ukraine with the words ‘Peace for Ukraine’ (in Polish) at the bottom of the application email. Surprisingly, we found that this signal increases the positive response rate.

The results from this study are especially interesting as they show that the level of discrimination in Poland has changed since the start of the war and decreased towards certain groups. A major problem with regard to discrimination is that it is difficult to reduce and widespread. Research shows, when analyzing multiple studies, that the extent of discrimination can be persistent over decades (Heath and Di Stasio Citation2019; Quillian and Midtbøen Citation2021). Additionally, while some studies find that measurements such as an information intervention can reduce discrimination (Boring and Philippe Citation2021), even well-intended interventions sometimes do not lead to the intended results (Dur, Gomez-Gonzalez, and Nesseler Citation2022). Our findings show that discrimination has changed. Finally, a perceived or actual increase in the foreign-born population is often associated with an increase in xenophobia (Jolly and DiGiusto Citation2014; Semyonov et al. Citation2004). The results from this experiment, however, show more nuanced results. The perceived and real share of the foreign-born population increased in Poland, but the degree of discrimination decreased compared to previous studies.

This research addresses the impact of attitudes towards people with foreign-sounding names in amateur soccer in Poland. Specifically, it explores the discrimination that people with foreign-sounding names face in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Historically characterized as a predominantly monoethnic nation, Poland experienced a significant surge in its foreign-born population following a substantial influx of Ukrainians in 2022. The primary aim of this study is to quantitatively assess the extent of discrimination that individuals with foreign-sounding names face when trying to join an amateur football team. We examine the following questions: what is the level of discrimination against people with a foreign-sounding name in Poland? Do different major national groups experience different levels of discrimination? Does signaling support for Ukraine influence the response rate?

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: In the next section, we give a brief historical perspective on Poland. Subsequently, we discuss related literature and formulate hypotheses. We then describe the method and data and examine the results. We set the results into context in the discussion and finish with the conclusion.

Brief historical perspective on Poland

Intersocietal relations have had a strong impact on Polish history. Particularly crucial were the long-lasting conflicts with Russia and Germany, symbolized in a glaring way by the partitions of Poland (Lukowski Citation1999) and subsequent policies of russification and germanization of the Polish society (Lukowski and Zawadzki Citation2001), and ultimately by the Nazi and Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939 and subsequent occupations (Williamson Citation2012). They were marked by atrocities such as the holocaust or the Katyn massacre of Polish officers (Sterio Citation2011). After World War II, Poland became the satellite state of the Soviet Union (Brzezinski Citation1967). However, belonging to the same geopolitical bloc did not lead to the disappearance of anti-Soviet sentiments (Skobelski Citation2015), with a dominant feeling of Soviet oppression. This political situation left a strong mark on the Polish mentality. In the case of Germany, the historical hostility has been exacerbated by the reconciliation already during the Cold War (Gardner Feldman Citation1999) and even more so after the democratization of Poland and its accession to the European Union. Thus, difficult historical relations with Russia/Soviet Union and Germany led to reserved attitudes towards both nations, although over time, sympathy towards Germans generally has been rising in Poland (Lepiarz Citation2022).

Atrocities and their historical scrutiny also influenced Polish–Ukrainian relations. Many parts of Ukraine were within Polish borders during the Second Republic of Poland (1918-1945). Although Polish-Ukrainian relations are regarded as predominantly peaceful (Copsey Citation2008), there were also occasional violent conflicts. A particularly controversial issue in Polish–Ukrainian relations is the massacres of Poles in Volhynia and in Eastern Galicia pursued in 1943 and 1944 (Komoński Citation2013). Their perception in both societies has a significant impact on Polish-Ukrainian relations. In Ukraine, Stepan Bandera and the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists that he co-founded and that is responsible for the massacre, have been considered fighters for liberation, with monuments erected in Bandera’s memory. Reconciliation between both nations regarding these events had been initiated already in the mid-1990s. However, symbols of the nationalist organizations OUN and UPA were still used during the Euromaidan protests of 2013–2014, and Ukrainian nationalism gained momentum in the face of the Russian annexation of Crimea and the subsequent war in Eastern Ukraine (Yurchuk Citation2017).

Another crucial factor is the ethnic structure of Poland. As a result of historical processes, Poland is a very monoethnic country. According to data for 2019, Poland was the second to last among all OECD countries concerning the percentage of the foreign-born population (OECD Citation2023). After its partition in 1795, Polish lands belonged to Russia, Prussia, and Austria, leading to a high level of multiethnicity after it regained its independence in 1918. The census of 1931 revealed the following main ethnic groups in Poland: Poles 68.9%, Ukrainians 13.9%, Jews 8.6%, Belarusians 3.1%, Germans 2.3% (Barwiński Citation2015). Following the developments of World War II, the change of borders and postwar migrations, both voluntary and forced, Poland became explicitly monoethnic. This situation did not change in the communist period. According to the 2011 census, 96.9% of the people living in Poland declared themselves Poles (other groups concerned both ethnic and national minorities) (Główny Urząd Statystyczny Citation2015), placing Poland among the most monoethnic countries in the world.

Unusual for other European nations, contemporary Polish society was somewhat closed to foreigners. During the European migration crisis of 2015, Poland was one of the least welcoming countries when the topic of refugees became an important part of the public debate (Narkowicz Citation2018). Additionally, the terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015 might have negatively influenced Poland’s society attitude towards refugees. Six months after the attack, the percentage of positive attitudes towards refugees in Poland dropped 30% (Głowiak Citation2021). Thus, in January 2016, only 4% of the respondents stated that Poland should accept refugees from countries in conflict and allow them to settle, 37% supported acceptance until refugees would be able to return to their countries, and 53% were against allowing refugees into Poland (CBOS Citation2016). A reserved attitude toward immigrants and refugees was also visible during the Belarus-EU border crisis 2021–2022 when thousands of migrants stormed the Polish, Lithuanian, and Latvian borders after arriving in Minsk on commercial flights. The Polish government decided to build a border fence to stop the migrant influx, a decision that 57% of Poles supported and only 19.3% disapproved (Money.pl Citation2021).

The composition of the population in Poland began to change in the 2010s. As a result of mainly economic migration, the share of the foreign-born population increased 26% from 2010 to 2020, with the largest share coming from Ukraine – around 34% (OCED iLibrary Citation2024). The labor market has absorbed Ukrainian migrants, with Poland recording record-low unemployment level in recent years (Wrona Citation2019). However, the focal point was the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. Enormous waves of Ukrainian refugees stormed the Polish border, primarily women and children as men were banned from leaving Ukraine (Cheytayeva Citation2022). Since the invasion, more than 11 million refugees have crossed the Polish–Ukrainian border (Statista Citation2023a). During the first year after the invasion, Polish authorities registered more than 1.5 million incoming Ukrainian refugees (UNHCR Citation2023).

The Russian invasion caused an unprecedented reaction in the Polish society. Many Poles offered Ukrainians rooms or apartments. Similarly, public institutions, for example universities, accommodated Ukrainian refugees in dormitories (Szlachetka Citation2022). The Polish state showed a supportive reaction, opening its borders to refugees and providing them with healthcare and education benefits. According to the Atlantic Council, this reaction ‘in many ways set the standard for Europe’s humanitarian response to the Russian attack on Ukraine’(Francis Citation2023). Interestingly, the reaction in Poland differed from previous behavior, for example, during the 2015 migration crisis. There was no general acceptance regarding immigrants and granting them refugee status. According to Maciejewska-Mieszkowska (Citation2022), the main reason for a more open attitude towards Ukrainian refugees after the Russian invasion was the perception of a more realistic security threat and a positive perception of refugees from Ukraine as people in need of support, culturally close, and not posing a threat.

The presence of Ukrainians in Poland became visible in all areas of life. For example, one year after the invasion, almost 190.000 Ukrainian children attended Polish kindergartens and schools (Matłacz Citation2023). Although many of the Ukrainian refugees that crossed Polish borders either returned to Ukraine or traveled to other countries, Poland has experienced a considerable increase in the size of its foreign-born population compared to the early 2010s.

Literature review and hypothesis

Multiple authors have observed discrimination in the area of sport (e.g. Kilvington and Price Citation2017; Moustakas and Kalina Citation2023; Nesseler et al. Citation2023). Discrimination in sport has been studied, e.g. in reference to LGBTQ+ (Denison, Bevan, and Jeanes Citation2021), gender (Joseph and Anderson Citation2016), or race (Price and Wolfers Citation2010). Several researchers have examined discrimination focusing on professional players, for example, in the premier league in the UK (Gallo, Grund, and James Reade Citation2013), in the NBA in the US (Johnson and Minuci Citation2020), or the Serie A in Italy (Caselli, Falco, and Mattera Citation2023). The results shows that discrimination is omnipresent but the level of discrimination is not similar, depending on sport, type of discrimination, and who suffers. Many studies focusing on one European country have examined discrimination in football. This has led main international and national football organizations and EU institutions to acknowledge the problem (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Citation2010). The real and pervasive nature of discrimination in sport was demonstrated in the 2024 statement by FIFA President Gianni Infantino, who addressed the 2024 UEFA Congress and said:

We say that football unites the world, but our world is divided, our world is aggressive, and in the last few weeks and months, we have witnessed, unfortunately, a lot of racist incidents. This is not acceptable anymore. We have to stop this, and we have to do whatever we can to stop this. Racism is a crime. Racism is something terrible. (FIFA Citation2024)

Discrimination in sport has also been studied with a focus on Poland. This research examined, e.g. gender discrimination (Organista Citation2020), content on football in Polish TV (van Lienden and van Sterkenburg Citation2022), or football fans (Kossakowski, Antonowicz, and Jakubowska Citation2020). Particular attention was dedicated to racism in football (Kobierecki, Kossakowski, and Nosal Citation2022) and to right-wing political views expressed by Polish football fans (Woźniak, Kossakowski, and Nosal Citation2020). Existing research generally reveals some level of discrimination in Polish sport, especially when focusing on football fans (Włoch Citation2014).

Using the same methodological approach, research finds that people with foreign-sounding names are discriminated against in amateur soccer (e.g. Gomez-Gonzalez, Nesseler, and Dietl Citation2021; Nesseler, Gomez-Gonzalez, and Dietl Citation2019). In Gomez-Gonzalez, Nesseler, and Dietl (Citation2021), the researchers examined discrimination in 22 European countries. While some countries had a not statistically significant level of discrimination, in all countries, however, people with a native-sounding name received more responses. Thus, our first hypothesis is as follows:

H1: People with a foreign-sounding name receive fewer positive responses.

Poland has undergone intense changes in the last years. Migration significantly altered Poland’s population, especially the 1.35 million Ukrainians who arrived already before the war in Ukraine (Lis, Citation2020). The 2022 Russian invasion brought millions of refugees to Poland, prompting a notable humanitarian response, and setting a European standard (Francis Citation2023; Statista Citation2023a). This influx, seen in education and society, reshaped Poland’s ethnic landscape compared to the early 2010s (Matłacz Citation2023). Previous work (Gomez-Gonzalez, Nesseler, and Dietl Citation2021) shows that Ukrainians suffer from discrimination in Poland. Additionally, positive economic conditions – a record-low unemployment level – do not necessarily translate into less severe xenophobia (Margalit Citation2019). However, many people in the Polish population seemed to have shifted their attitudes towards Ukrainians (Szlachetka Citation2022). Keeping in mind both the previous attitude and the recent changes, we construct the following hypothesis:

H2: People with Ukrainian-sounding names receive more positive responses than other foreign groups.

Finally, based on our own preliminary study, we observed that Poles do not find it easy to distinguish East European-sounding names from each other. We, therefore, assume that Ukrainian-sounding names, with which potential respondents might sympathize as representatives of a wartime victim, might confuse Russian- and Belarusian-sounding names, widely associated with the aggressor. This effect, however, might be reduced when signaling support for Ukraine. Research is ambiguous regarding signals in a political context. In political studies, signaling has been examined from different perspectives. In international relations, Schultz (Citation1998) investigated the influence of signals from the government and opposition on the escalation of international crisis. McManus and Yarhi-Milo (Citation2017), however, studied how major powers signal support for their protégés. In the studies of domestic politics, Lohmann (Citation1993) developed a signaling model of mass political action and investigated the influence of such signals on a political leader. Studies on signaling led to relevant conclusions. For example, Sen (Citation2017) observed evaluations of US Supreme Court candidates by Americans that in the absence of clear political cues, respondents rely on other political signals such as race to anticipate political leanings of particular candidates. These conclusions serve as the basis for the final hypothesis; If the name of the fictional player does not provide sufficient information, an additional signal, like the expression of support for Ukraine, might be helpful for respondents. This led to the formulation of the following hypothesis:

H3: Signaling support for Ukraine in its war with Russia increases the positive response rate.

The theoretical contribution of this work lies in extending the understanding of discrimination in the context of amateur soccer. The study builds on existing literature that has identified discrimination in various domains, emphasizing the unique context of recent socio-political changes in Poland. Additionally, the research contributes to the nuanced exploration of signaling effects in a political context, acknowledging potential complexities in public support for a cause, such as the Ukrainian-Russian conflict.

Method and data

Experimental setup

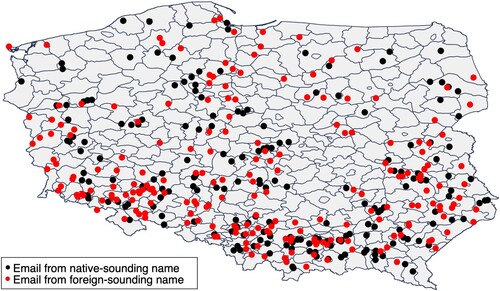

The research has been conducted through a randomized control trial. We gathered data for all available amateur football teams in Poland (N = 1289). This information includes the coach’s contact email, the club’s location, and the club’s homepage. Whenever possible, we contacted the coach. In some instances, the actual email belonged to the assistant coach or a club representative. We included only men’s teams because we did not find enough women’s team for an empirical analysis with enough power. If a club had more than one team, we randomly selected one team for our analysis. shows where the clubs are located.

We generated email accounts for typical Polish- and foreign-sounding names. The emails had the first name and the last name of the applicant with the ending felabpol.com (e.g. [email protected]). Gomez-Gonzalez, Nesseler, and Dietl (Citation2021) performed a similar field experiment in 22 European countries (including Poland). To be able to compare our results with their work, we used the same names. For Poland, they used five typical Polish-sounding names and two names for each of Poland’s three largest foreign groups (Belarussians, Germans, and Ukrainians). The complete list of the names is included in the Appendix (Table A1).

Polish people can recognize that the names are foreign, although it is not always easy for them to tell the origin of the name. We asked 80 students how they would categorize Ukrainian- and Belarussian- sounding names. The results are available in the Appendix (Table A2). About half of the students correctly classified Ukrainian-sounding names. Around 40% of the students categorized Ukrainian-sounding names as either Belarussian or Russian. Additionally, students were unable to distinguish whether a Belarussian-sounding name was Russian or Belarussian (and, to a lesser extent, Ukrainian). Thus, it is important to remember that respondents in the experiment might evaluate the names differently. Especially, the results regarding Belarussian-sounding names must be interpreted carefully as respondents might interpret them as Russian-, Belarussian-, or Ukrainian-sounding. It is important because, according to public opinion polls from February 2023, Ukrainians belong to the nations that Poles are most sympathetic to (51% sympathy, 17% antipathy). In turn, Belarusians (19% sympathy, 51% antipathy) and Russians (6% sympathy, 82% antipathy) belong to the most unliked nations and ethnic groups (Infor Citation2023). These results differ slightly from earlier polls before the Russian invasion of Ukraine when the figures were as follows: Ukrainians (41% sympathy, 25% antipathy), Belarusians (35% sympathy, 29% antipathy), and Russians (29% sympathy, 38% antipathy) (CBOS Citation2022).

We used block randomization by region to ensure that groups or names were not overrepresented (Gerber and Green Citation2008). This explains why we sent out similar but not exactly the same number of emails per group. In addition, we randomly assigned coaches to receive an email from either the treatment or the control group. In the control group, coaches received an email that looked very similar to the original design of this type of test correspondence asking coaches to join a trial training session (Nesseler, Gomez-Gonzalez, and Dietl Citation2019). We did not specify education, residence, or other attributes apart from the name of the applicant. The text of the email for the control group was as follows:

The email’s exact text (in Polish) for both treatment and control group is included in the Appendix. Each respondent received only one email to avoid that respondents potentially change their behavior after receiving an unusual number of trial training request emails (Sedgwick and Greenwood Citation2015).

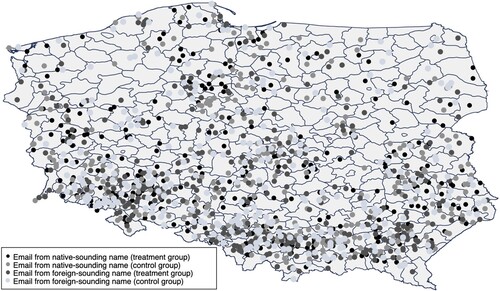

We randomly distributed the recipients into the control and treatment group. 641 recipients received an email without a signal at the end of the email, and 648 recipients received an email with such a signal. shows the geographic distribution of these groups. We used block randomization by name group (i.e. Polish, Belarussian, German, and Ukrainian) for emails to be sent out either on Monday, Tuesday, or Wednesday. The email provider we used has a daily limit of 500 emails and we wanted to ensure this limit was not exceeded. We performed the field experiment from February to March 2023. We sent emails out between Monday (13.02) and Thursday (16.02). If the email address was incorrect, we tried to find a new one and contacted these recipients on Thursday. 37 emails were categorized for other days, but because the recipient was incorrect, we sent them out on Thursday. During the first two weeks after the start of the experiment, we checked the email accounts daily. Most of the respondents arrived one or two days after we contacted a club. We did not receive any more emails after three weeks. We followed the accounts for six weeks until we sent the last email. After we received a response, we debriefed the respondents and informed them that they had participated in an experiment.

Figure 2. Geographic distribution of clubs in experiment, separated into treatment and control group.

Following a predetermined categorization scheme, we categorized each response into negative, positive, positive with further inquiries, or discriminatory (cf., Dur, Gomez-Gonzalez, and Nesseler Citation2022; Gomez-Gonzalez, Nesseler, and Dietl Citation2021). Typical positive responses are an invitation to join a trial practice. A positive response with further inquiries includes further questions. For example: ‘Where have you played before?’, ‘How old are you?’, ‘Can you call me?’, ‘Can you give me your phone number?’. A negative response states that coming for a trial practice is impossible. A discriminatory response would only ask for nationality, for example, ‘Where are you from?’. gives an overview of the experimental settings and the results. Finally, we combined discriminatory and negative responses (approximately 1% of all responses).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.*

One of the limitations, not considered at the preliminary stage of the study, was the details of the emails sent to the football teams’ representatives. To maintain the consistency of the research, we used similar content for all the emails besides the name and signal. While analyzing and coding the responses, we discovered that many clubs had more than one football team, usually referring to different age groups, with teams often being coached by different coaches. Therefore, some of the positive answers with further inquiry stemmed from the genuine need for more information so that the fictional player was directed to the appropriate coach or provided appropriate training sessions times, for example, the respondents requested the age of the (fictional) player so that they could provide the email address of the appropriate coach or the time of the training session for the particular age group. Thus, some of the responses coded as ‘further inquiries’ could well have meant ‘yes’.

Ethical considerations

Before starting the experiment, we got ethical approval from the advisory board of the University of Lodz and registered the experiment at the AEA RCT registry (AEARCTR-0010916). The setup of the experiment had two ethical issues. First, the initial data included personal information, i.e. the email of the recipient. We needed this information at the beginning as we had to match the response with the respondent in the dataset. We deleted this information from the final dataset. Additionally, data regarding this research is publicly available on harvardDataverse and does not include individually identifiable information. This dataset does not include information from the post-experiment survey.

Second, respondents were not informed about this experiment before we started and had no opportunity to give their consent. Alternatives to this kind of experiment, for example, interviews or surveys with coaches, might not necessarily have revealed their real behavior but, for example, a social desirability bias. Thus, we decided not to inform the respondent before the experiment. In agreement with the advisory board, we debriefed the respondents if they responded to our email. We informed the respondents that they participated in an experiment, the purpose of the experiment, who they could contact to know more about the experiment and who would have access to the data. The complete debriefing text is available in the Appendix. The text was constructed in agreement with the advisory board.

Results

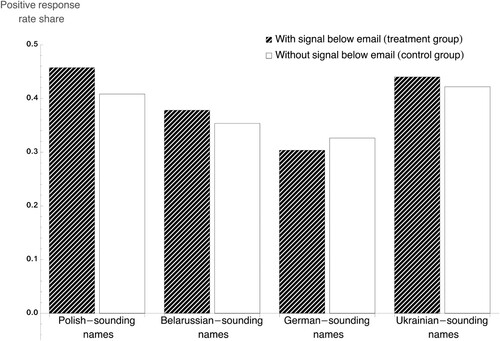

After receiving an email for a trial training request, 41% of the respondents answered. 23% gave a positive response, 17% a positive response with further inquiries, and 1% a negative response. The share of emails in the control group (without a signal) that received a positive response or a positive response with further inquiries is 39%. This is slightly higher, 41%, for emails in the treatment group (i.e. with a signal). Following previous research in this area (e.g. Dur, Gomez-Gonzalez, and Nesseler Citation2022; Gomez-Gonzalez, Nesseler, and Dietl Citation2021; Nesseler, Gomez-Gonzalez, and Dietl Citation2019), we first examined the data combining positive response and positive response with further inquiries into one group. Afterwards, we focused on the different positive responses.

If we focus on our results without the signal, we find that Gomez-Gonzalez, Nesseler, and Dietl (Citation2021) had a lower but not statistically significant response rate for natives compared to our results (0.408 vs. 0.401; average treatment effect (ATE) 0.007; Mann–Whitney U, z = −0.21, p = 0.84, N = 988).Footnote1 The response rate for foreign-sounding names is statistically significantly higher compared to Gomez-Gonzalez et al., (0.370 vs. 0.296; ATE 0.074; Mann–Whitney U, z = −2.274, p = 0.023, n = 965). This is due to Belarussian- and Ukrainian-sounding names. The response rate for both groups increased. Compared to Gomez-Gonzalez et al., the response rate for German-sounding names decreased. Additionally, the total response rate increased as well (0.390 vs. 0.348; ATE 0.042; Mann–Whitney U, z = −1.800, p = 0.072, n = 1.953).

shows the share of the positive response rate (combining positive response and positive responses with further inquiries) for each group (i.e. names that sound Polish, Belarussian, German, and Ukrainian) and whether they were in the treatment or control group. These results show that, except for German-sounding names, each group had a higher response rate share in the treatment group. Thus, having a signal that shows support for Ukraine increased the chances to receive a positive response.

Figure 3. Share of positive responses to applications with Polish-, Belarussian-, German-, and Ukrainian sounding names for treatment and control group.

In the next step, we examined the results with a regression analysis. The dependent variable is binary (Responsei), 1 represents a positive response, 0 a negative response. The subscript I denotes one respondent. We first ran a basic regression (Model 1 in ):

Table 2. OLS regression results – positive and negative responses.

In this regression, β1 is an estimate that measures if the response rate differs if the email was sent from a native- or a foreign-sounding name. We split up foreign-sounding names (β2, β3 and β4 provide estimations). We included control variables for the league a club plays in, the region in which a club is located, and the day a respondent received the request. ϵi is the error term. To examine the influence of the treatment, we included a control variable for the treatment (Model 2 in ) and interacted this variable with the name of the sender (Model 3 in ).

Additionally, we focus on a model that distinguishes only between foreign- and native-sounding names (Model 4 in ), and include the same treatment (Model 5 in ), and interaction (Model 6 in ):

The dependent variable was binary using an Ordinary Least Squares analysis in all tables. This approach is appropriate and the results are straightforward to interpret. A probit model is also well suited to examine the results and the results from this approach are available in the Appendix (Table A3 and A4 – including marginal effects in the tables). The estimations are very similar.

Model 4 shows that applicants with a foreign-sounding name received statistically significant (at the 5% level) fewer responses. Models 1 and 2 show that applications from German-sounding names received the fewest responses – around 11 percentage points less than Polish-sounding names.

When including the treatment, i.e. an email with a signal, we found that applicants with a native-sounding name still get more responses (Model 6). However, this difference is no longer statistically significant. Having a signal increased the response rate in general. Models 3 and 6 show that using a signal had no statistically significant effect.

Additional analyses

The previous analyses were all preregistered. However, after the experiment, we also wanted to examine whether the kind of positive response differs between the various groups. As we clarified in the Method and data section, a positive response and a positive response with additional inquiries can be very different. Thus, we wanted to examine whether, for example, applicants with a foreign-sounding name might have received equally often positive responses but were more often requested to provide more details. To examine this relationship, we focused exclusively on positive responses: the dependent variable is 1 if the response is positive and 0 if a response is positive but with additional inquiries ().

Table 3. OLS regression results – focusing on positive responses.

Surprisingly, native-sounding names received a positive response with additional inquiries more often (statistically significant at the 5% level in Model 4, 5, and 6). Belarussian- and Ukrainian-sounding names were more likely to receive a positive response (without further inquiries) compared to respondents with a native-sounding names (Models 1, 2, and 3). Models 3 shows that especially Belarussian- and German-sounding names received a response asking for further inquiries when using a signal.

Post-experiment survey

Four weeks after the end of the randomized control trial, we contacted 400 coaches and asked them to complete a survey, including 200 coaches that responded to our fake applicant and 200 who did not respond (see Figure 1(a) in the appendix). For each group, we contacted 100 respondents that received a request signed with a foreign-sounding name and 100 that received a request signed with a native-sounding name. We did not contact all coaches as we did not want to increase the workload of all the respondents. Thus, we randomly selected the 400 coaches from the sample. In the survey, we asked coaches about their age and gender, their experience at their club, the number of Polish players in their team, if they would be open to foreign players, their experience with foreign players, and if they think that foreign players would influence team morale.

We received 33 responses in total – 14 responses from coaches that responded positively to a native-sounding name, 1 from a coach that did not respond positively to a native-sounding name, 9 responses from coaches that responded positively to a foreign-sounding name, and 6 responses from coaches that did not respond positively to a foreign-sounding name. Seven responses come from coaches that did not respond to the fake applications in the randomized control trial (RCT). Due to this low response rate (8.3% of all coaches we contacted) we do not want to overestimate the results from the survey. Most coaches were between 35 and 44 (42%; n = 14) or younger (30%; n = 10). All responses were from men’s team coaches, with two women and 31 men among them. The responses came mostly from experienced coaches, i.e. coaches who had worked for more than five years (81%; n = 27). 33% (n = 11) of the teams had no foreign players, 18% (n = 6) had one foreign player, 18% (n = 6) had two foreign players, and 30% (n = 10) had more than three foreign players. All coaches stated that they would not mind having foreign players in their team. This is especially interesting as 18% (n = 6) of the survey respondents did not respond when receiving a request from a foreign player.

In the comment section of the question regarding being open to having foreign players in the team, positive attitudes towards foreign players dominated, although there were also negative remarks. We should be cautious in interpreting these results. Many respondents may not openly state that they discriminate. They may be modifying their response to what they expect would signal positive behavior, i.e. we should be wary of social desirability bias. One of the coaches noted that he did not mind foreign players but some of the Polish players occasionally did, leading to internal divisions among the team members. Another coach mentioned negative experiences with foreign players who joined the team and then after a short period ‘vanished’. Additionally, one coach argued that he had good experiences with foreign players but claimed that it would be good if they spoke Polish, an observation also mentioned by another coach in a comment regarding the morale of the team. When asked if foreign players influenced team morale, only one coach answered yes, commenting that Polish players might be jealous. The final question was open and referred to the experience of working with foreign players. Among the 25 answers, four coaches reported having no experience. Others answered neutrally, e.g. describing the nationalities of foreign players, the length of experience with foreign players, or reported positive opinions about foreign players. Only one respondent claimed that the experience with foreign players is generally good, but there were also individuals (i.e. foreign players) who ‘kept complaining’.

Discussion

In this paper, we examined the attitude in Poland towards people with Belarussian-, German-, Ukrainian-, and Polish-sounding names. Furthermore, we examined whether the attitude changed and whether a signal – showing support for Ukraine – had an effect on this attitude. The results showed that people with foreign-sounding names received fewer responses. However, people with Ukrainian-sounding names received as many responses as Polish-sounding names. It is important to note that many Poles cannot distinguish between Belarussian- and Ukrainian-sounding names. Thus, these results should not be overemphasized.

We found that, on average, foreign-sounding names received fewer responses compared to native-sounding names – this supports our first hypothesis. This result is unsurprising as it confirms previous research using correspondence tests (e.g. Ahmed and Hammarstedt Citation2008; Antfolk, Szala, and Öblom Citation2019; Bertrand and Mullainathan Citation2004; Dur, Gomez-Gonzalez, and Nesseler Citation2022). Football in Poland has traditionally not been free from discrimination and racism (Burski and Woźniak Citation2021). In general, sport creates a sense of nationality-based ‘ourness’ and essentializes the idea of a nation (Bairner Citation2009). Particularly the period of transformation after the collapse of communism in Poland was marked by an intensification of racist behavior among football fans. In this sense, Poland did not differ much from other Central and Eastern European countries (Kobierecki, Kossakowski, and Nosal Citation2022). Discrimination has been more typical among football fans than among teams. For example, the anti-racist programs pursued in Poland focus on racism among fans − often in cooperation with football club officials (Wachter et al. Citation2009). As one of the participants in the post experiment survey commented, sport, as a rule, should be free from racism.

Our findings show a lower degree of discrimination compared to previous results (Gomez-Gonzalez, Nesseler, and Dietl Citation2021). These outcomes might be attributed to the rapidly changing ethnic structure of the Polish society. Poles might have changed their attitude, becoming used to foreigners and accepting their presence in everyday life. Especially if Ukrainians are considered, currently the largest group of foreign nationals living in Poland. With a record low unemployment rate and widespread sympathy with the nation under attack, also taking into consideration long-lasting antipathy towards Russians stemming from the history of Polish-Russian relations, there seems to be little space for anti-Ukrainian sentiments. Interestingly, Ukrainian-sounding names do not receive significantly fewer responses compared to native-sounding names. These results, however, have to be interpreted carefully as we expect that Polish people are not completely able to distinguish between Ukrainian- and Belarussian-sounding names. We have learned from the surveys and additional comments that were sent to the authors after the experiment, many of the teams already had Ukrainian players in their squad. Thus, coaches might be more accustomed to them.

The response rate is significantly lower for German- and Belarussian-sounding names. This supports our second hypothesis. Despite the general increase in the response rate to the emails signed by foreign-sounding names compared to previous studies, we observed a decrease in reference to German-sounding names even with the signal of support for Ukraine. Although such signaling increased the chances for a positive response for all other groups. Thus, we fail to support hypothesis 3 for all foreign groups. In the case of German-sounding names, the argument about the difficulty in determining the origin of the name is not valid. Still, several developments in Polish politics could serve as an explanation for the drop in positive responses. Poland’s largest political party Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS) has been using anti-German sentiments to consolidate its support over the last few years (Skóra Citation2022). From a societal perspective, this standpoint was further strengthened after the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the initially ambivalent German position and reluctance to provide Ukraine with military assistance (Francis Citation2023).

Apparently, the problem of Polish perception of the German response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine was not unnoticed by the German diplomatic representation in Poland. On the website of the German Embassy in Poland, we can read the quote from Ambassador Thomas Bagger referring to the ‘invasive Russian war against Ukraine’ which shows the importance of solidarity, community and Polish-German partnership (Ambasada Niemiec w Warszawie Citation2023), while outside the Embassy there were pictures showing anti-Russian manifestations in Germany. Even though as of 25 January 2023, Germany ranked third globally in the amount of aid provided to Ukraine after the Russian invasion (Statista Citation2023b), its initial resistance from delivering weapons together with the pre-war German-Russian cooperation marked by undertakings such as the Nord Stream 2 could have led to more reserved attitudes toward Germans among some Poles. Thus, the signal of support for Ukraine, in this case, could also increase the acceptance of foreign players.

Finally, we found that Poles were more often asked additional inquiries when contacting a club. One interpretation is that not asking for additional inquiries is a first step towards openness. Respondents either invite players directly or not at all. However, this result has to be interpreted very carefully. Many of the additional inquiries were ultimately technical in nature. Fictional players with foreign-sounding names were asked about the possibility of commuting to training sessions and matches (many of the teams in the study are in rural areas, sometimes with underdeveloped public transport) and even more often about their age. As indicated in the methodological section, the study design did not consider that sports clubs might have different sections in various sports and in various age groups. Therefore, directing a player to an appropriate coach required additional inquiries.

Conclusions

We performed a randomized control trial with amateur football coaches in Poland. We contacted coaches asking for the possibility come for a trial practice with either a typical foreign- or native-sounding name. We found that people with foreign-sounding names get fewer responses, but the type of foreign group has an important influence. Signaling support for Ukraine had a positive but not statistically significant effect on the response rate.

Our study is limited to amateur football, referring only to one aspect of social life. Future research could focus on other sports or social arenas, e.g. choirs, dance classes, etc. Additionally, this setting does not include women. This is a major shortcoming, as many refugees are women. The names for Ukrainians, as Table A2 clearly shows, are not necessarily clear for Polish people. This is a shortcoming as respondents might have confused with another group. Also, we focused on the short-term impact of Ukrainian refugees in Poland. We found encouraging results with respect to the support of Ukrainians. This might be different when focusing on long-term development. Finally, our focus is on Poland. Several other European countries also dealt with a large inflow of Ukrainian refugees. The situation in other countries could provide an informative comparison.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study is publicly available in HarvardDataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WLA2R7

. The data are fully anonymized.Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The data for the Gomez-Gonzalez, Nesseler, and Dietl (Citation2021) paper are publicly available: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/FOXODW

References

- Ahmed, A. M., and M. Hammarstedt. 2008. “Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market: A Field Experiment on the Internet.” Journal of Urban Economics 64 (2): 362–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2008.02.004

- Ambasada Niemiec w Warszawie. 2023. [online]. Accessed 21 Apr 2023. https://polen.diplo.de/pl-pl/01-vertretungen/01-1-die-botschaft.

- Antfolk, J., A. Szala, and A. Öblom. 2019. “Discrimination Based on Gender and Ethnicity in English and Polish Housing Markets.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 29 (3): 222–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2396

- Auspurg, K., T. Hinz, and L. Schmid. 2017. “Contexts and Conditions of Ethnic Discrimination: Evidence from a Field Experiment in a German Housing Market.” Journal of Housing Economics 35: 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2017.01.003

- Bairner, A. 2009. “National Sports and National Landscapes: In Defence of Primordialism.” National Identities 11 (3): 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/14608940903081101

- Banerjee, A., M. Bertrand, S. Datta, and S. Mullainathan. 2009. “Labor Market Discrimination in Delhi: Evidence from a Field Experiment.” Journal of Comparative Economics 37 (1): 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2008.09.002

- Barwiński, M. 2015. “Spisy powszechne w Polsce w latach 1921-2011-określanie czy kreowanie struktury narodowościowej?” Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Geographica Socio-Oeconomica 21 (3): 53–72. https://doi.org/10.18778/1508-1117.21.03

- Bertrand, M., and S. Mullainathan. 2004. “Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination.” American Economic Review 94 (4): 991–1013. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828042002561

- Boring, A., and A. Philippe. 2021. “Reducing Discrimination in the Field: Evidence from an Awareness Raising Intervention Targeting Gender Biases in Student Evaluations of Teaching.” Journal of Public Economics 193: 104323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104323

- Brzezinski, Zbigniew K. 1967. The Soviet Bloc: Unity and Conflict, 9–12. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Burski, J., and W. Woźniak. 2021. “The Sociopolitical Roots of Antisemitism among Football Fandom: The Real Absence and Imagined Presence of Jews in Polish Football.” In Football and Discrimination, edited by P. Brunssen and S. Schüler-Springorum, 47–64. London: Routledge.

- Caselli, M., P. Falco, and G. Mattera. 2023. “When the Stadium Goes Silent: How Crowds Affect the Performance of Discriminated Groups.” Journal of Labor Economics 41 (2): 431–451. https://doi.org/10.1086/719967

- CBOS. 2016. “Stosunek Polaków do przyjmowania uchodźców.”

- CBOS. 2022. “Komunikat z badan: Stosunek do innych narodów” [online].

- Cheytayeva, I. 2022. How men try to get around the ban to leave Ukraine. Deutsche Welle, 19 Jul.

- Copsey, N. 2008. “Remembrance of Things Past: The Lingering Impact of History on Contemporary Polish–Ukrainian Relations.” Europe-Asia Studies 60 (4): 531–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130801999847

- Denison, E., N. Bevan, and R. Jeanes. 2021. “Reviewing Evidence of LGBTQ+ Discrimination and Exclusion in Sport.” Sport Management Review 24 (3): 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2020.09.003

- Dur, R., C. Gomez-Gonzalez, and C. Nesseler. 2022. “How to Reduce Discrimination? Evidence from a Field Experiment in Amateur Soccer.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (1): 175–191.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. 2010. Racism, Ethnic Discrimination and Exclusion of Migrants and Minorities in Sport: A Comparative Overview of the Situation in the European Union. Luxembourg: Publications office of the European Union, 58. https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/1207-Report-racism-sport_EN.pdf.

- eurostat. 2023. Migration and migrant population statistics [online].

- FIFA. 2024. Gianni Infantino Calls on European Member Associations to Work with FIFA in ‘United Way’ to Stop Racism, February 8, 2024, accessed February 17, 2024. https://www.fifa.com/about-fifa/president/news/gianni-infantino-calls-on-european-member-associations-to-work-with-fifa-to-stop-racism.

- Francis, D. 2023. “Poland is Leading Europe’s Response to the Russian Invasion of Ukraine” [online]. Accessed 18 Apr 2023. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/poland-is-leading-europes-response-to-the-russian-invasion-of-ukraine/.

- Gallo, E., T. Grund, and J. James Reade. 2013. “Punishing the Foreigner: Implicit Discrimination in the Premier League Based on Oppositional Identity.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 75 (1): 136–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2012.00725.x

- Gang, I. N., F. Rivera-Batiz, and M.-S. Yun. 2002. “Economic Strain, Ethnic Concentration and Attitudes Towards Foreigners in the European Union.” Ethnic Concentration and Attitudes Towards Foreigners in the European Union (September 2002).

- Gardner Feldman, L. 1999. “The Principle and Practice of ‘Reconciliation’ in German Foreign Policy: Relations with France, Israel, Poland and the Czech Republic.” International Affairs 75 (2): 333–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.00075

- Gerber, A. S., and D. P. Green. 2008. Field Experiments and Natural Experiments. The Oxford Handbook of Political Science.

- Głowiak, K. 2021. “Stosunek Polaków do przyjmowania uchodźców przed iw warunkach europejskiego kryzysu migracyjnego.” Historia i Polityka 42 (35): 147–162. https://doi.org/10.12775/HiP.2021.009

- Gomez-Gonzalez, C., C. Nesseler, and H. M. Dietl. 2021. “Mapping Discrimination in Europe Through a Field Experiment in Amateur Sport.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00773-2

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. 2015. Struktura narodowo-etniczna, językowa i wyznaniowa ludności Polski: Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011 [National-Ethnic, Linguistic and Religious Stucture of the Population of Poland: Census of Population and Accommodation]. Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny.

- Heath, A. F., and V. Di Stasio. 2019. “Racial Discrimination in Britain, 1969–2017: A Meta-Analysis of Field Experiments on Racial Discrimination in the British Labour Market.” The British Journal of Sociology 70 (5): 1774–1798. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12676

- Infor. 2023. “Które narody Polacy lubią bardziej, a które mniej w 2023 roku? Co wynika z badan?” [online].

- Johnson, C., and E. Minuci. 2020. “Wage Discrimination in the NBA: Evidence Using Free Agent Signings.” Southern Economic Journal 87 (2): 517–539. https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12461

- Jolly, S. K., and G. M. DiGiusto. 2014. “Xenophobia and Immigrant Contact: French Public Attitudes Toward Immigration.” The Social Science Journal 51 (3): 464–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2013.09.018

- Joseph, L. J., and E. Anderson. 2016. “The Influence of Gender Segregation and Teamsport Experience on Occupational Discrimination in Sport-based Employment.” Journal of Gender Studies 25 (5): 586–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2015.1070712

- Kilvington, D., and J. Price. 2017. “Introduction: Offering a Critical and Collective Understanding of Sport and Discrimination.” In Sport and Discrimination, edited by D. Kilvington and J. Price, 13–24. London: Routledge.

- Kobierecki, M. M., R. Kossakowski, and P. Nosal. 2022. “Opportunistic Nationalism and Racism: Race, Nation, and Online Mobilization in the Context of the Polish Independence March 2020.” Soccer & Society 23 (8): 865–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2022.2109803

- Komoński, E. 2013. “Anthropology of Fear. Ukrainian Massacres of the Polish Population in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, 1943–1944.” Studia z Dziejów Rosji i Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej 48 (1): 120–127.

- Kossakowski, R., D. Antonowicz, and H. Jakubowska. 2020. “The Reproduction of Hegemonic Masculinity in Football Fandom: An Analysis of the Performance of Polish Ultras.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Masculinity and Sport, edited by R. Magrath, J. Cleland, and E. Anderson, 517–536. Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19799-5_29

- Kumar, B. N., R. James, S. Hargreaves, K. Bozorgmehr, D. Mosca, S.-M. Hosseinalipour, K. N. AlDeen, C. Tatsi, R. Mussa, and A. Veizis. 2022. “Meeting the Health Needs of Displaced People Fleeing Ukraine: Drawing on Existing Technical Guidance and Evidence.” The Lancet Regional Health-Europe 100403.

- Lepiarz, J. 2022. “Barometr 2022: asymetria sympatii między Polakami a Niemcami” [online]. Deutsche Welle. Accessed 20 Apr 2023. https://www.dw.com/pl/barometr-2022-asymetria-sympatii-mi%C4%99dzy-polakami-a-niemcami/a-62301822.

- Liadze, I., C. Macchiarelli, P. Mortimer-Lee, and P. S. Juanino. 2022. “The Economic Costs of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict.” NIESR Policy Paper 32: 874–886.

- Lis, M. 2020, 4 June. GUS podał szacowaną liczbę cudzoziemców w Polsce. Przekroczyła dwa miliony. Business Insider.

- Lohmann, S. 1993. “A Signaling Model of Informative and Manipulative Political Action.” American Political Science Review 87 (2): 319–333. https://doi.org/10.2307/2939043

- Lukowski, Jerzy. 1999. The Partitions of Poland 1772, 1793, 1795. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lukowski, Jerzy, and Hubert Zawadzki. 2001. A Concise History of Poland, 166. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Maciejewska-Mieszkowska, Katarzyna. 2022. “Stosunek Polaków do uchodźców w kontekście wojny w Ukrainie.” Środkowoeuropejskie Studia Polityczne 4: 137–153. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssp.2022.4.7

- Margalit, Y. 2019. “Economic Insecurity and the Causes of Populism, Reconsidered.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33 (4): 152–170. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.152

- Matłacz, A. 2023. “W polskich szkołach i przedszkolach uczy się 187,9 tys. dzieci z Ukrainy” [online]. Accessed 18 Apr 2023. https://www.prawo.pl/oswiata/ukrainskie-dzieci-w-polskich-szkolach,520015.html.

- McKee, M., and A. Murphy. 2022. “Russia Invades Ukraine Again: How Can the Health Community Respond?” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 376.

- McManus, R. W., and K. Yarhi-Milo. 2017. “The Logic of ‘Offstage’ Signaling: Domestic Politics, Regime Type, and Major Power-Protégé Relations.” International Organization 71 (4): 701–733. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818317000297

- Money.pl. 2021. “Kryzys na granicy.” Polacy popierają budowę muru, 20 Nov.

- Moustakas, L., and L. Kalina. 2023. “Fighting Discrimination Through Sport? Evaluating Sport-Based Workshops in Irish Schools.” Education Sciences 13 (5): 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050516

- Narkowicz, K. 2018. “‘Refugees Not Welcome Here’: State, Church and Civil Society Responses to the Refugee Crisis in Poland.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 31 (4): 357–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-018-9287-9

- Nesseler, C., C. Gomez-Gonzalez, and H. Dietl. 2019. “What’s in a Name? Measuring Access to Social Activities with a Field Experiment.” Palgrave Communications 5 (1): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0372-0

- Nesseler, C., C. Gomez-Gonzalez, P. Parshakov, and H. Dietl. 2023. “Examining Discrimination Against Jews in Italy with Three Natural Field Experiments.” Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 106: 102045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2023.102045

- OECD. “Foreign-born Population”, accessed 20.11.2023. https://data.oecd.org/migration/foreign-born-population.htm.

- OECD. “iLibrary”, accessed 20.02.2024. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/77e8b1e1-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/77e8b1e1-en.

- Organista, N. 2020. “‘The Top is Always Reserved for Men’: Gendering of Leadership Positions in Polish Sports Federations.” Polish Sociological Review 212 (4): 497–516.

- Price, J., and J. Wolfers. 2010. “Racial Discrimination among NBA Referees.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 125 (4): 1859–1887. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2010.125.4.1859

- Quillian, L., and A. H. Midtbøen. 2021. “Comparative Perspectives on Racial Discrimination in Hiring: The Rise of Field Experiments.” Annual Review of Sociology 47 (1): 391–415. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-090420-035144

- Schultz, K. A. 1998. “Domestic Opposition and Signaling in International Crises.” American Political Science Review 92 (4): 829–844. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586306

- Sedgwick, P., and N. Greenwood. 2015. “Understanding the Hawthorne Effect.” Bmj 351: 1–2.

- Semyonov, M., R. Raijman, A. Y. Tov, and P. Schmidt. 2004. “Population Size, Perceived Threat, and Exclusion: A Multiple-Indicators Analysis of Attitudes Toward Foreigners in Germany.” Social Science Research 33 (4): 681–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2003.11.003

- Sen, M. 2017. “How Political Signals Affect Public Support for Judicial Nominations: Evidence from a Conjoint Experiment.” Political Research Quarterly 70 (2): 374–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912917695229

- Skobelski, R. 2015. “Zagraniczne echa wyborów do Sejmu PRL z 20 stycznia 1957 roku.” Studia z Dziejów Rosji i Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej 50 (2).

- Skóra, M. 2022. “How the Polish-German Relationship Turned Sour.” IPS, 10 Jan.

- Statista. 2023a. “Number of People Who Crossed the Polish Border from the War-stricken Ukraine from February 2022 to April 2023, by Date of Report” [online]. Accessed 18 Apr 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1293564/ukrainian-refugees-in-poland/.

- Statista. 2023b. “Total Bilateral Aid Commitments to Ukraine between January 24, 2022 and January 15, 2023, by Type and Country or Organization” [online]. Accessed 20 Apr 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1303432/total-bilateral-aid-to-ukraine/.

- Sterio, M. 2011. “Katyn Forest Massacre: Of Genocide, State Lies, and Secrecy.” Case W. Res. J. Int’l L. 44: 615.

- Szlachetka, M. 2022. “Uniwersytet Łódzki oddaje Ukraińcom pokoje w akademikach. Pierwsza rodzina już jest” [online]. wyborcza.pl. Accessed 18 Apr 2023. https://lodz.wyborcza.pl/lodz/7,35136,28160181,pomoc-dla-uchodzcow-z-ukrainy-uniwersytet-lodzki-oddaje-pokoje.html?disableRedirects=true.

- UNHCR. 2023. “Ukraine Refugee Situation” [online]. Accessed 18 Apr 2023. https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine.

- van Lienden, A., and J. van Sterkenburg. 2022. “Prejudice in the People’s Game: A Content Analysis of Race/Ethnicity in Polish Televised Football.” Communication & Sport 10 (2): 313–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479520939486

- Wachter, K., S. Franke, J. Purski, and C. Kassimeris. 2009. “Football Against Racism in Europe.” Anti-Racism in European Football: Fair Play for All, 35–66.

- Williamson, David G. 2012. Poland Betrayed The Nazi-Soviet Invasions of 1939. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books.

- Włoch, Renata. 2014. Przejawy dyskryminacji (rasizm, antysemityzm, ksenofobia i homofobia) w polskim sporcie ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem środowiska kibiców sportowych. Warszawa: Ministerstwo Sportu i Turystyki.

- Woźniak, W., R. Kossakowski, and P. Nosal. 2020. “A Squad with no Left Wingers: The Roots and Structure of Right-Wing and Nationalist Attitudes among Polish Football Fans.” Problems of Post-Communism 67 (6): 511–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2019.1673177

- Wrona, M. 2019. “Ukraińcy na polsim rynku pracy: Raport Europejskiej Sieci Migracyjnej”.

- Wysienska-Di Carlo, K., and Z. Karpinski. 2014. “Discrimination Facing Immigrant Job Applicants in Poland-results of a Field Experiment.” In: XVIII ISA World Congress of Sociology.

- Yurchuk, Y. 2017. “Reclaiming the Past, Confronting the Past: OUN–UPA Memory Politics and Nation Building in Ukraine (1991–2016).” In War and Memory in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, edited by J. Fedor, M. Kangaspuro, J. Lassila, and T. Zhurzhenko, 107–137. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66523-8_4

Appendix

Table A1. Names in experiment − positive response rates in brackets (in %), with comparison of results from Gomez-Gonzalez, Nesseler, and Dietl (Citation2021).

Table A2. Names in experiment – focus on Belarussian- and Ukrainian-sounding names (N = 80). Table A3. Probit results with marginal effects. Table A4. Probit results with marginal effects – focusing on positive responses.