ABSTRACT

What does it mean to come together as a group of migrant women, to paint the face of a murdered woman, on the wall of a building in a town that was only temporarily her home? And, who does it have meaning for? In this paper, I interrogate this act as a participant in Las RestaurAmoras, the feminist collective responsible for painting murals of victims of feminicide in Quintana Roo, Mexico, in 2021. I argue that the physical and emotional conditions involved in painting the murals caused members of Las RestaurAmoras to forge a deeper connection with each other and the deceased women they painted. This emphasised sameness and belonging between migrant women, both living and deceased. As finished artefacts, I suggest that, as memorialisation, the murals challenge harmful discourse and practice that invisibilises migrant women’s lives and the violence they experience. The murals are a reminder and a demand that femicidal violence must be dealt with urgently. I argue that connection among (migrant) women and emphasising the importance of the lives of (migrant) victims of feminicide are key elements in protection for women in places with high rates of gender-based violence and impunity, in this case, Quintana Roo.

Introduction

What does it mean to come together as a group of migrant women, to paint the face of a murdered woman, on the wall of a building in a town that was only temporarily her home? And, who does it have meaning for? In this paper, I address these questions through an analysis of seven murals featuring nine victims of feminicide,Footnote1 painted by feminist collective Las RestaurAmoras in Quintana Roo, Mexico, between March and September 2021. Neither the murals nor the original research were carried out explicitly with migration in mind. However, migration is of fundamental importance when considering the context of high rates of gender-based violence, feminicide and impunity in Quintana Roo and the ways that migration can increase vulnerability. Quintana Roo, especially the Riviera Maya, experiences some of the highest rates of internal migration, and to a lesser but still significant extent, external migration, in Mexico (Castellanos Citation2010; Fernández Rodríguez et al. Citation2020; Torres and Momsen Citation2005). Indeed, Las RestaurAmoras was formed in March 2021 when Salvadoran refugee Victoria Salazar was killed by police in the Riviera Maya as a result of excessive force during her arrest. After that, we (six women, the majority migrants or with lived experience of migration) painted eight more murals, with five of those being for migrant women.Footnote2

I conceptualise the murals first as creative process, and second as finished artefacts in public space. I begin by arguing that the physical and emotional conditions involved in painting the murals caused members of Las RestaurAmoras to forge a deeper connection with each other, with collaborators outside of the collective, and with the deceased women they painted. This emphasised sameness and belonging between migrant women – both living and deceased – rather than difference and transience. I suggest that this generates a notion of a ‘common body’ (Gago and Malo Citation2020) among women, which strengthened Las RestaurAmoras’ commitment to feminist activism against gender-based violence and supports the development of feminist networks of protection.

Next, I argue that the murals disrupt the dominant cultural and political narrative of gender-based violence in Quintana Roo through public memorialisation. Aligning myself with arguments made by anti-feminicide scholars and others about the systemic nature of gender-based violence, feminicide and impunity and its intricate relationship with the state, my conviction is that the murals as visual discourse expose and reconceptualise invisibilised violence in Quintana Roo. This is because they draw attention to both the existence of and, at the same time, the subsequent absence of, murdered migrant women. Where top-down discourse and practice tries to invisibilise and therefore obscure migrant women’s lives and the violence they experience, the murals draw attention to it and the urgent need for resolution of femicidal violence.

I also suggest that the context of migration and transience in Quintana Roo increases women’s vulnerability to gender-based violence and feminicide because of the lack of structural and interpersonal protection that migrant status often incurs there. As such, the strong connections with other women that developed through painting the murals are deeply politically significant, and also frankly necessary for women to survive and flourish. Moreover, the murals as memorialisation counter violent discourse and practice that invisibilises migrant women as victims/survivors of femicidal violence, something which puts them at risk.

I develop my analysis from my position as a core member of Las RestaurAmoras. At the time I carried out the ethnographic research that informs this paper, Las RestaurAmoras was a collective comprising six women based in Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo. It was part of the larger feminist civil society organisation Siempre Unidas in Playa del Carmen. The name is a play on the word restauradora, a woman employed to restore art. By changing the ‘d’ to ‘m’, the word amor (love) is included, thus expressing the idea of reparative artwork created with love. To support the data gathered through participant observation, in July 2021 I also carried out in-depth semi-structured interviews with the other five members of Las RestaurAmoras. All of the participants identify as women and are Mexican, although only Laura is from the state of Quintana Roo.

I am a white, English academic who has spent the past seven years living and working between England and Mexico. Even though I was in my third year of paid employment in academic research when I began my involvement with Las RestaurAmoras, I did not join the group as a researcher, but rather as an artist, activist and friend of two of the artists.

Exposing and challenging normalised gender-based violence in Mexico and beyond

Gender-based violence is the main cause of death for women aged between 19 and 44 in the world, and it manifests in a range of ways (True Citation2012). Feminicide is the most extreme expression of violence against women. At the root of all gender-based violence are structures of global political economic processes that influence and exacerbate women’s susceptibility to violence (True Citation2010). Furthermore, constructions of femininities subordinate women and often legitimise violence against women through the gendered roles assigned to them (Elias and Rai Citation2015). Multiple forms of everyday gendered violence across ‘public' and ’private' spheres are created and perpetuated by state and non-state institutions, policies and ideologies that are further imbricated by other social identities, such as race and sexuality (Elias and Rai Citation2015; 2019; Enloe Citation2014; Pain and Staeheli Citation2014; Tickner Citation1992; True Citation2012; True and Tanyag Citation2018). In other words, gender-based violence is systemic and is normalised through discourse and practice.

I start this paper by introducing these ideas because they highlight the mundaneness or ‘permanent condition’ (Kinna and Whiteley Citation2020, 6) of gender-based violence, which is so intricately interwoven in the everyday that its many forms can become hidden in plain sight. Even examples of violence that we may consider spectacular violence, such as feminicide, are often normalised, minimalised, or met with indifference in this context.

Gender-based violence and the impunity around it is exacerbated by the neoliberal global economic, political and cultural system, which creates a culture of extreme inequality, commodification and personal blame. In places where global inequalities are more evident because of the proximity between the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’, insecurity increases. Anti-feminicide scholarship in Mexico has shown this to be the case in Ciudad Juárez, which is ‘probably the most infamous single city of femicide in Latin America, and possibly in the entire world’ (Corradi et al. Citation2016, 984), and the empirical and geographical centre of theorising on feminicide in Mexico (Lagarde Citation2005, Citation2006; Monárrez Fragoso Citation2000, Citation2004; Monárrez Fragoso et al. Citation2018; Wright Citation2011; Segato Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2014). For example, Wright (Citation2011) has argued that a ‘gendered necropolitics’ is evident in Ciudad Juárez, where violence related to the international drugs trade carried out by both state and non-state actors is justified as rational, business-like and valid in the masculinised public realm and at the same time, victims of feminicide are regularly blamed for their own deaths because they occupy this public space. Segato (Citation2013, Citation2014) also posits that contemporary violence is ‘written on women’s bodies’ in Latin America, especially in Ciudad Juárez, caused by ‘apocalyptic capitalism’ and the corruption and collusion between state and criminal non-state actors which creates and perpetuates feminicide and conditions of extreme impunity.

In these contexts of profound inequalities and insecurity, not all women face the same risks with regard to gender-based violence. Women’s intersectional characteristics including race and ethnicity, age, dis/ability, sexual orientation, socioeconomic condition and migrant status all impact women’s exposure to violence, and the resources they can access to escape it. Migration is an important determinant of women’s experience of gender-based violence (McIlwaine Citation2024). Migration can present new challenges, where gendered socioeconomic conditions increase vulnerability to bodily harm through violence, coercion and exploitation at all stages in the migration journey, including settlement (Freedman Citation2016). Furthermore, poverty, isolation from support networks, and lack of familiarity with a new place can limit women’s access to resources that could support them to leave situations of violence (Oliveira et al., Citation2018; Phillimore et al., Citation2022).

In the case of feminicide, it is also essential to consider the role of victims’ families when a loved one is murdered. In locations with high rates of impunity, families play an integral role in securing justice and resolution of cases. Across Mexico, and in other parts of Latin America, it is often victims’ family members – especially mothers – who search tirelessly for justice for murdered or missing women and girls and risk their own lives in the process (Castañeda Salgado Citation2016; Driver Citation2015; Las Tres Muertes de Marisela Escobedo Citation2020; Monárrez Fragoso et al. 2018; Segato Citation2013; Vargas Martinez and Araiza Diaz Citation2020). Segovia and Jasso (Citation2020) argue that activism led by mothers is an essential element in the truth and justice agenda as part of wider efforts to challenge impunity. Much of the activism that family members undertake centres on keeping both their loved ones and their loved ones’ cases visible, driven by an emotional and political desire for justice (Cerva Cerna Citation2020; Lamas Citation2021; Monárrez Fragoso et al. 2018; Orozco Citation2017; Wright Citation2011). There are many practical barriers to working to secure this justice when the victim is a migrant who was murdered in a place where she was living without her family. Family members may experience barriers regarding money, time and language (including in cases of internal migration, when victims come from Indigenous communities), and are unlikely to have contacts or community support in the place where their loved one was killed. If family members cannot perform the labour of keeping their loved one’s case visible and under investigation, the chances of receiving resolution and justice are significantly reduced.

The theories of everyday and spectacular violence that I have introduced here provide important grounding from which to analyse gender-based violence and feminicide in Quintana Roo, where there is limited research on the cultural politics of gender-based violence. There are important similarities in terms of political, economic and cultural characteristics between Ciudad Juárez and parts of Quintana Roo, especially with regard to the stark economic inequality and corruption that confronts residents daily, and the pull of economic opportunities that attract migrants to work in undervalued and precarious positions. Importantly, gender-based violence linked to these structural conditions is increasing rapidly in Quintana Roo.

The gender-based violence alert (AVGM)Footnote3 has been activated in three municipalities in Quintana Roo since 2017. All three of these municipalities are located in the Riviera Maya, municipalities which have been purposefully and rapidly developed to serve (mostly international, particularly US) tourists (Torres and Momsen Citation2005); these include Benito Juárez (Cancun), Solidaridad (Playa del Carmen) and Cozumel (Cozumel). In the first half of 2021, the second-highest number of feminicides in the country was recorded in the state of Quintana Roo (OSEGE, 2021). In the first half of 2020, cases of trafficking of women into the sex industry – the most exploitative industry for women in the world (Jeffreys Citation2009) – rose by 265% in Quintana Roo, making it the state with the highest number of cases of trafficking in Mexico (PorEsto Citation2020). It also occupies the highest ranking for cases of rape and HIV in Mexico (OSEGE, 2021).

The particular risks of gender-based violence that women in Quintana Roo face are intricately linked to migration and the tourism trade – including the illicit economies of people and drug trafficking associated with tourism – especially in the Riviera Maya. There are high rates of migration and immigration to Quintana Roo, driven largely by the employment opportunities presented by the booming tourist industry (Castellanos Citation2010; Cuevas Citation2021; Fernández Rodríguez et al. Citation2020). That the population of the state increased by forty per cent in just ten years between 2010 and 2020 speaks to the intensity of this migration (DataMexico Citation2021). However, the violence created through exploitative socioeconomic conditions leaves many migrant women in situations of precarity and insecurity caused by poverty, economic inequality, and racist and gendered profiling that means some bodies are seen as more valuable than others.

The highest rates of internal migration to the Riviera Maya tend to be from rural locations, including poorer states like Chiapas and Tabasco, and Indigenous communities in Yucatan and elsewhere in Quintana Roo (Castellanos Citation2010; Fernández Rodríguez et al. Citation2020). Much migration is driven by the pull of better earning opportunities, but the Riviera Maya is one of the most expensive places to live in Mexico, and salaries do not necessarily reflect this (Fernández Rodríguez et al. Citation2020). This is particularly true for migrant labourers who are most likely to work in the most low-paid and insecure jobs in the most exploitative industries – for women this means working ‘behind the scenes’ cleaning, cooking and caring in hotels or private homes, and for Indigenous women can also mean making and selling traditional crafts on the city centre streets (Castellanos Citation2010; DataMexico Citation2021; Fernández Rodríguez et al. Citation2020). This creates significant challenges for women with regard to safety. On the one hand, on a pragmatic level, less money and more precarity limit women’s opportunities to be able to escape violent situations with intimate partners or families. It also forces women to live in insecure accommodation and neighbourhoods, often far from their workplaces, with risky and lengthy commutes (Castellanos Citation2010; Elias and Rai Citation2019).

Furthermore, the gendered and ‘ethnic division of labour’ (Fernández Rodríguez et al. Citation2020, 75; see also Castellanos Citation2010) which is evident in the Riviera Maya contributes to and reinforces gendered and racist stereotypes in the tourism industry which commodifies the bodies of women (Orozco Citation2019) and characterises some women as more valuable than others (Castellanos Citation2010; Elias and Rai Citation2015; Enloe Citation2014; Pain and Staeheli Citation2014). These stereotypes and divisions are so normalised that they are often taken for granted (Enloe Citation2014). Women within this international tourist industry are either made invisible through low-status jobs, or made highly visible through processes of exoticisation; in both cases, they are exposed to predatory behaviours and practices by men and masculinised systems and structures.

Critical artistic interventions and public space

In the face of such ubiquitous, normalised violence, what can art do? According to political theorists Danchev and Lisle (Citation2009, 775–776) ‘art matters, ethically and politically; affectively and intellectually’ primarily because ‘it make[s] us feel, or feel differently, it also makes us think, and think again’. Art historian Griselda Pollock (Citation2013, 22) agrees; art addresses questions of ‘seeing, not-seeing, fearing what we see, failing to see’. As such, it forces people to consider and reconsider what they otherwise may not question. This is one of the most important functions of critical art when the artistic intervention as finished artefact is considered.

Memorial murals in particular have far-reaching cultural and political impact because they provide a visual counter narrative to official accounts of violent events. Murals are ‘not merely inanimate objects in space, but a dynamic element in the political process’ (Rolston Citation2003, 3). Murals painted in public places by community members to commemorate violence are fundamentally about offering a counter narrative to official or top-down accounts of the same incidents and, usually, emphasising the absence of truth and justice in these events (Heidenry Citation2014; Karl Citation2014; Rolston Citation2003; Rolston and Ospina Citation2017). Memorialisation murals purposefully take mourning to public space because they are intended to implicate the state in committing violence, including both original acts of violence and in the subsequent violence of victim-blaming and impunity, and as such to imbue the state with responsibility not only for committing violence, but also as responsible for ensuring redress and resolve. Therefore they enter into a conflictive dialogue with the state and express the ideological position of those who paint or who support the painting of them. Because of their relative permanence in public space, they are ‘expressions of memory that continuously speak and engage viewers’ (Heidenry Citation2014, 126) and therefore they become part of the social, cultural and political fabric of a community. As well as commemorating violence, these murals are intended to rehumanise and celebrate the lives of victims of violence, re-establishing them as individuals whose lives and the circumstances around their death matter (Karl Citation2014; Meikle Citation2020).

Theorists who study anti-feminicide artistic interventions in Ciudad Juárez make similar arguments regarding dialogue with the state and the relationships with memorialisation and public space (Castañeda Salgado Citation2016; Driver Citation2015; Orozco Citation2017, Citation2019). Castañeda Salgado (Citation2016, 1055) suggests that artists are part of the range of actors who visualise feminicide and its ‘relationship with the global patriarchal, capitalist trend.’ ‘Ephemeral’ art (Driver Citation2015) has contributed to the ‘funeralization’ of Ciudad Juárez (Orozco Citation2017). To be specific, this means that the murals, graffiti, flyers of missing girls and women, pink wooden crosses and black painted crosses located throughout the city are a visual reminder that the city should be in a constant state of mourning until the gender-based violence, feminicide and impunity there are properly addressed (Castañeda Salgado Citation2016; Driver Citation2015; Orozco Citation2017, Citation2019).

Three main arguments are made about the role of this art. First, these visual objects change people’s physical experience of public space in Juárez. By disrupting the landscape with reminders of feminicide in Juárez, Driver (Citation2015) and Orozco (Citation2017) suggest that a statement is made about the gendered power struggles inherent in public space, and the authorities’ insistence on blaming women for their own deaths when they dare to step out of the apparently safe confines of the so-called private sphere. Second, in Juárez the producers of art are victims’ families, as well as feminist artists and activists. This returns control of the stories of feminicide and victims of feminicide to people who are able to represent them from a position of empathy, crucial in the context of smear campaigns and victim blaming led by authorities. Coronado (Citation2020a, 66; Citation2020b, 181), founder of anti-feminicide art project No Estamos Todas,Footnote4 argues that when feminist artists and activists take control of the visual representation of victims of feminicide, they do so from a place of ‘love and respect’, creating art which humanises and honours victims, ‘using empathy as a tool to create connections’ and rejecting misogynistic and violent discourse.

Finally, this feminist reclaiming of public space through art and objects shapes collective memory in a way which honours victims and ensures they are not forgotten (Gasca Macías Citation2019, 116). In fact, Driver (Citation2015, 21) calls those who make these objects in Juárez a ‘community of rememberers’. By keeping objects and images present in public space, artists are drawing attention to the absence of missing and murdered women. As well as ensuring that feminicide victims are viewed as individuals, as women and not as statistics (Coronado Citation2020b), in the collective memory, through their art this community of rememberers also draws attention to the absence of justice for these women and the criminality of the state (Orozco Citation2017). By analysing how feminist activists represent feminicide visually in public space, we can better understand how space is gendered and politicised, and how the local and everyday is linked to global political economic power structures (Castañeda Salgado Citation2016; Driver Citation2015; Orozco Citation2017, Citation2019).

There is important critical value in the collective nature of the process of creating socially engaged, collaborative art. Socially engaged art is seen as a sort of antidote to the harm done in capitalistic societies because it places more value on the process of creation rather than the end product (Bishop Citation2006). Bourriaud (Citation2002, 15. Italics in original), one of the strongest proponents of socially engaged collaborative art, makes an important point in arguing that collaborative public art ‘tightens the space of relations’ between people in a society increasingly designed to alienate and reduce compassionate interaction. Corcoran (Citation2020, 91, 85) elaborates on Bourriard’s claims in the context of collaborative art produced within social movements in suggesting that art activism:

punctures narratives formulated around the ‘other’ and exposes the violence of actions taken against them … conveying this information visually and emotionally collapses the distance states seek to put between them and the victims of their violence, and instead addresses audiences intuitively.

The counter-arguments of those who have cautioned against taking the socially engaged nature of collaborative art at face value are important (Bishop Citation2006; Bogerts Citation2017; Gogarty Citation2017). This is because both the process of creation and the finished project can end up playing into dominant discourses and systems of power, rather than critically engaging with them. Indeed, this type of practice can become institutionalised and actually increase the gap between the ‘artist’ and collaborators who are only nominally co-producers (Petersen and Neilsen Citation2021). However, as I argue, in the case of Las RestaurAmoras, the connections generated between all of those who were involved in creating the anti-feminicide murals did seem to ‘tighten the space of relations’ (Bourriaud Citation2002, 15) in several sometimes unexpected ways.

Methodology and positionality

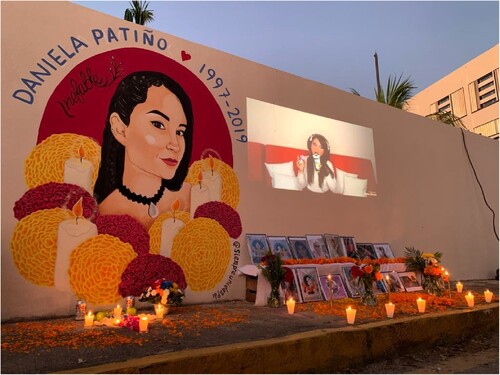

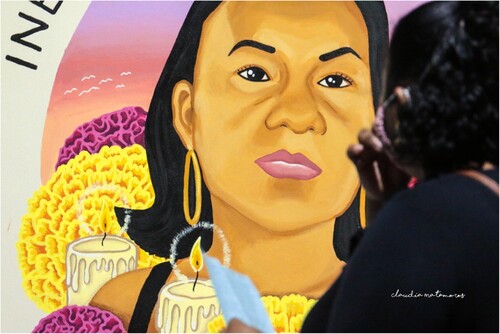

The murals analysed in this study were painted in Quintana Roo between March and September 2021. The process of painting them generally followed the same structure on all occasions. Each began with contact between core members of Siempre Unidas and the family of a victim of feminicide. Who initiated contact varied; in older cases, contact was already established and had been maintained over years, in newer cases, the opportunity to paint a mural was sometimes the catalyst to develop relationships between families and Siempre Unidas. The family would provide photographs of the victim and describe what the deceased woman liked or what was important to them, which could then be included as visual elements of the mural. For example, this might be their favourite flowers, their hobbies or interests, or their pets. Laura and I would take turns to create the sketch of the mural, which we would then project onto a wall in a public space, and paint together with the other members of Las RestaurAmoras and Siempre Unidas. Permission was always gained to paint on these walls, which were generally found through other members of the local informal feminist network. Murals took anywhere between approximately 15 and 50 hours to paint, depending on the size and condition of the wall, and how many people helped to paint. Members of the local informal feminist network and family and friends of the victim also participated in painting. Once the mural was finished, Las RestaurAmoras would organise an unveiling (see ), where friends and family members would share their memories about the victim and their case, and a member of Siempre Unidas would contextualise the case in the wider socio-political and cultural context. Candles would be lit and flowers laid; sometimes other members of the network sang and played music. Unfortunately, there is not enough space in this paper to elaborate in a meaningful way on the individual stories of all of the victims whose portraits we painted. However, where possible I include links to their cases for more information. I also include images of some of the murals painted while this investigation was carried out; all of these were taken by documentary photographer Nallely Matamoros and are reproduced here with her permission.

Figure 1. The unveiling of the mural of Daniela Patiño, whose family and friends in Colombia joined via video link.

The primary method employed in this investigation is participant observation as part of feminist auto-ethnographic practice. If done responsibly, ethnography can have important and practical repercussions for social justice, in spaces of activism and advocacy (Backe Citation2020) and in spaces where knowledge is produced and legitimised (Manning Citation2018; Reyes Cruz Citation2008; Uddin Citation2011). In July 2021, I also carried out in-depth semi-structured interviews with the other five members of Las RestaurAmoras.Footnote5 I used this method to strengthen the data I collected through participant observation and to provide an opportunity for the other women in Las RestaurAmoras to tell their own stories (Ahmed Citation2017; Letherby Citation2015; Oakley Citation2015).

Feminist scholars agree on the importance of the researcher positioning themself within their research and critically reflecting on their ‘epistemological assumptions, their situatedness with respect to the research’ and how these elements may affect power dynamics between the researcher and researched (Thambinathan and Kinsella Citation2021, 3; also Haraway Citation1988; Held Citation2019; Stanley and Wise Citation1993). McIlwaine and Ryburn (Citation2024) point out that the roles of the researchers, artists and participants involved in arts-based work on migration and violence, and the relationships between them, are complex, and require careful reflection and consideration. My own ‘feminist story’ (Ahmed Citation2017) influenced my decision to study this topic and my consequent experience in the field and afterwards, while interpreting and writing up the findings. I recognise that my intersectional characteristics are in many ways protective factors in relation to gender-based violence, especially as a white British woman in Mexico. I reflected on these characteristics in my field notes in July 2021 after Laura called out the simple phrase that is part of the everyday vocabulary of many women, as she got into a car with the rest of the collective, while I got onto my bike to cycle home after another day of mural painting: ‘text us when you get home!’ The threat of danger bubbles under this phrase. And of course, we had just been painting the beautiful, smiling face of Erika Sánchez,Footnote6 a woman younger than me who one day had not made it home. Yet I was never worried that I would not make it home after painting a mural. Both my intersectional characteristics, and my involvement with Siempre Unidas, have provided me with a deep sense of security and comfort in Mexico as insider and outsider (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007; Stack Citation1993). Throughout my time in Las RestaurAmoras I was a feminist activist and artist, but I was also an ethnographical observer from an English institution, and the ‘outsiderness’ of being an English person in Mexico was always present. At the same time, some of the structural and interpersonal vulnerabilities I discuss in this paper have touched me personally, and have been important in developing the approach I take in my activism and research.

‘To give up this fight is like turning my back on myself’:Footnote7 mural painting as strengthening grassroots feminist networks of protection

I start my discussion by examining the impact of the process of painting anti-feminicide murals on the members of Las RestaurAmoras. I argue that being immersed both in painting the murals and participating in the collective provoked moments and actions through which Las RestaurAmoras fomented and solidified their political and personal identities as women, artists and feminists. Painting brought the artists closer together with each other and with the other women involved in the painting of each mural, including family and friends of the victims, and even in some ways, the victims themselves. This tightened the space (Bourriaud Citation2002) between distinct women, emphasising shared experiences and life stories. An integral part of this process was their migrant status. Strengthening connections – real and symbolic – between the women involved in creating the murals is particularly important for their safety in a context where many women migrate to the Riviera Maya alone and must build up networks of friendship, support and protection, in the face of increasing gender-based violence and impunity.

The feminist adage that the personal is political, and especially Ahmed’s (Citation2017, 2) active interpretation of this incorporated into the concept of living a feminist life, resonates with the experience of Las RestaurAmoras. Those involved each told me that since becoming aware of the meaning of feminism and began participating in feminist activism, their political beliefs permeated every aspect of their lives. As Laura explained:

I practise feminism in my life in general every day from when I wake up to when I sleep, and at work too … these days it’s not even like you can say you don’t want to fight, there is so much around you, so many things happening, that it’s impossible to decide to not do anything or not speak out … it’s a way of life.

re-enacting those narratives weighed heavily on our bodies. Memories were reawakened, and our ‘whole body felt’ various complex, contradictory, and intertwined emotions, feelings, and sensations.

The physical conditions of painting the murals were difficult (see ). While this led to challenges for the collective, they also served to intensify the emotional experience and affective bonds that developed during the process of painting. This carried with it a certain therapeutic element that others have pointed out as running through collective arts-based responses to gender-based violence (McIlwaine Citation2024) on the one hand, as well as a desire to enact ‘care-full’ (Sheringham, Taylor and Duffy-Syedi Citation2024) practices towards other members of the collective, the victims and their loved ones, through our painting. I describe the physical conditions in an excerpt from my field notes:

We experience a range of intense physical, emotional and affective reactions throughout the process of creating the murals. Each mural takes at least fifteen hours to paint, with the majority taking significantly longer. The heat, mosquitoes, and size or quality of the wall make the task of painting more difficult. We end each day tired, sometimes sunburned, dehydrated. The six of us are present at every mural, and we invite other members of the wider feminist collective to participate. Some come to paint, some to document the process, some to bring food and water. We are always accompanied by family and friends of the victim, who paint with us, share stories of their loved one and sometimes the circumstances under which they were killed, who also prepare us homemade food and bring us chilled water, spending their own resources on us. These conditions and the presence of the wider network of other activists and the friends and family members of victims create the physical context in which the mural painting takes place. (Field notes, Playa del Carmen, August 2021)

Figure 2. Las RestaurAmoras paint their largest and most physically challenging mural, of feminicide victim Steysi Burgos.

As we painted the murals, the stories that family members and friends of the victims told us of how the cases of their loved ones had unfolded underscored the absolute necessity for women to have a strong support network in the face of gender-based violence and impunity. The sister of one victim told us of her frustration and helplessness as police failed to arrest the man who confessed to killing her sister;Footnote8 the sister of another explained through tears, that she had been the one who had to search for and eventually find her sister’s body (see and ).Footnote9 It is difficult to rely on the support of the authorities. For migrant women who arrive in Quintana Roo alone, vulnerability can increase exponentially in distinct ways. As Lupe explained in our interview, without the legal support and lobbying of Siempre Unidas, the feminicide of her friend – also a migrant to Playa del Carmen – would most likely have remained ignored, just like the majority of the cases of the victims we painted.Footnote10

Figure 4. A woman pauses as she reads a letter addressed to her deceased sister, captured in this mural, in which she expresses not only her grief but also her anger at the lack of resolution to this case of feminicide.

Feminist theorists in Latin America emphasise the central role that murdered women play in driving feminist activism, with Gago (Citation2018) and Félix de Souza (Citation2019) even positing that murdered women have a certain agency in this context. Gago (Citation2018: 660) argues that murdered women have the capacity to generate empathy and rage – and consequently, action. She states that the roots of the contemporary feminist movement in Mexico are in the question that the Ciudad Juárez feminicides provoked in Mexican women: ‘what was also killed in us each time one of those women workers was killed?’

Relatedly, Orozco (Citation2019) has argued that the possessions of missing and murdered women placed in public space in Ciudad Juárez as a form of protest also have an element of agency, since they call attention to the absence of their owners and the absence of justice in their cases. Underpinning all of these claims of the agency is the conviction that victims of feminicide provoke such a deep affective response in many women, that it drives their feminist activism. This sense of connection with deceased women was evident for Las RestaurAmoras. As I argue elsewhere (Lines Citation2022), as we paint, our personal narratives become interwoven with those of the women we portray. Laura explained this eloquently highlighting the impact of the physical and emotional context of painting the murals:

It’s true, we get tired when we paint … but nothing about this work compares to the death of a mother, a daughter, a friend … in the case of Natty, she could have been my mother. So if I cried, yeah I cried for Natty, but really I cried because I felt that me too, that my mother was dead. I feel like now there is no going back, right, because to give up this fight is like turning my back on myself.

‘The murals stay there, in the everyday … what we do is like an alarm’:Footnote11 feminist memorialisation as counter narrative

Everyday experience in distinct spaces is affected by violent ‘structures of power that constrain, govern, and discipline everyday life, as well as the gendered forms of agency that serve to reshape the everyday’ (Elias and Rai Citation2019; 202. See also Orozco Citation2019; True Citation2012). Art troubles these spaces and the violence that maintains them (Bogerts Citation2017; Castro Sánchez Citation2018; Orozco Citation2017, Citation2019; Pain and Staeheli Citation2014). As Gideon (Citation2024) points out, arts-based counter memorialisation practices can simultaneously emphasise the role of the state in committing violence against their populations, and commemorate victims in a way that emphasises the voice of their family members left behind.

Memorialisation murals in particular are well established as a visual language that conveys critical political messages. Las RestaurAmoras challenge the gendered and exclusionary nature of public space by making visible the absence of murdered women and of justice for them and intervening in collective memory. This is particularly powerful because of the migrant identities of most of the women involved in the murals and how this is intimately linked to the tourist industry and associated illicit economies in Quintana Roo. A combination of transience and of concerted efforts to invisibilise and obscure affects women who migrate to work in positions ‘behind the scenes’ in hotels, restaurants, and private homes, or women who are trafficked against their will to labour in illicit economies, or women who become involved either directly or by association with drug sales and organised crime. We have painted murals remembering migrant women who lived all of these experiences. In contrast to efforts from the authorities to actively hide these women and the everyday and spectacular violence that was part of their lives, the Las RestaurAmoras murals reaffirm that these women existed and their lives mattered, and that there is an urgent need to address the femicidal violence which led to their deaths. In this way, the murals alter discourse and practice that harms women, presenting an alternative way of remembering victims of feminicide which supports protective mechanisms for women. The analysis which follows demonstrates that the murals are indeed ‘a dynamic element in the political process’ (Rolston Citation2003, 3) of reimagining gender-based violence, feminicide and impunity in Quintana Roo, and that they became part of the fabric of the communities that they were painted in (Heidenry Citation2014; Rolston and Ospina Citation2017).

The murals’ role as memorials becomes particularly clear during each unveiling, when friends, family and activists gather to pay tribute to the victim, mourn, share stories about who she was, and place flowers and candles at the foot of each painting. In some cases, family and friends cannot be physically present when a mural is unveiled because they and the victim are from different towns or countries. In the case of Daniela,Footnote12 for example, a young woman conned and trafficked into the sex industry, her family and best friend joined by video call from Colombia. When discussing the murals’ function in creating and sustaining collective memory, Jeni observes that feminicide is ‘an open secret’, something that people know about but try to ignore. But permanent, visual reminders of its existence make this denial more difficult.

Keeping individual victims of feminicide present in collective memory has important political implications. Instead of being mere statistics, or being blamed for their own deaths, the murals rehumanise the victims. This is achieved on a visual or aesthetic level by using a photograph chosen by the family from which to design the portrait: families chose photographs that captured the personality of their loved one, and almost without fail, show them smiling or laughing. Furthermore, the inclusion of representations of their hobbies, interests, favourite flowers or pets helps capture the essence of who the victim was before their life was taken. By rehumanising the victims in public space, ‘the political value of those who were stripped from it’ is ‘reaffirm[ed]’ (Monárrez Fragoso et al. 2018: 922). This rehumanisation in public space draws attention to attempts by the state to maintain ‘power and domination over bodies’ by obscuring the violence that victims of feminicide endured (Karl Citation2014, 729). The murals therefore act as both ‘discourses and acts of rehumanization’ which ‘mean that the [victims] are being given back their erased and stolen identities through political rituals’ (Karl Citation2014, 730).

The murals also function in making visible both the absence of murdered women and the absence of justice, truth, care and attention from the authorities in dealing with their cases (Castañeda Salgado Citation2016; Driver Citation2015; Lagarde Citation2006; Orozco Citation2017, Citation2019; Segato Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2014; Wright Citation2011). Making these absences visible has implications for the victims’ families, especially those who do not live in Quintana Roo. For the members of Las RestaurAmoras, the most important audience for the murals is each victim’s family. The primary intention of the murals, as Dayana and Jeni clarified in our interviews, is to show solidarity and support towards the families. Dayana told me that, for her, the murals are powerful because ‘the fact that people name you again … you come back to life … you keep [the deceased woman] alive’. As the following extract from my field notes shows, the murals provoke a very real sense of the victim's presence for loved ones.

We’re having lunch together one Thursday between murals. Not for the first time, our conversation turns to Don Saul, who has truly become part of the movement. Jeni laughs as she recounts how he helped them move their tents into the state congress building when feminist collectives occupied it in 2020 … Don Saul is tireless in his quest for justice for his daughter Erika. He was with us through the whole process of painting her mural, joining in with painting the sunflowers, Erika ́s favourite flowers. Lupe smiles. ‘Do you remember what he said about the mural while we were painting though?’ We turn to look at her. ‘He said it was like seeing her reborn. He said nothing had moved him like seeing that.’ (Field notes from Playa del Carmen, May 2021)

Migrant women in areas of intense tourism, like Quintana Roo, are objectified and devalued as a result of the racist commodification of certain gendered, classed and racialised bodies (Castellanos Citation2010; Enloe Citation2014; Segato Citation2013; Wright Citation2011). This motivates Las RestaurAmoras to make present and visible the gendered violence that women experience in the Riviera Maya, on the one hand, and to honour the memory of the women we paint in a way that humanises and respects them. In their capacity as artefacts of counter memory, the murals express feminist discontent with dominant narratives and practice about gender-based violence, feminicide and impunity, especially for women who are made even more vulnerable because of their migrant status. This positions both the murals, and, importantly, the women they represent, as firmly part of the cultural political fabric in Quintana Roo, in a way that emphasises their dignity and vitality and as such, demands justice for them and protection for other women like them.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have argued that both the creative process and the finished Las RestaurAmoras feminicide murals hold political significance for the artist-activists who paint them and for families and friends of the victims, and that they reverberate at a wider cultural political level in their capacity as memorialisation artefacts. Quintana Roo is characterised, nationally and internationally, as a major site of international tourism. The tourism industry and the illicit economies that are part of it is exploitative, and the global political economic systems and structures that maintain it create conditions where some bodies are more valued than others, and where violence is inherent but invisibilised. Women from rural and/or poor areas in Mexico who migrate to Quintana Roo to improve their economic opportunities are exposed to the risk of femicidal violence through poverty, precariousness and racist and gendered stereotyping. In this context, it is important to create spaces of empathy, anger and action, which counter discourses and practices that dehumanise and devalue some groups, and increase their exposure to violence.

I suggest that the process of mural painting has great value in research and activism, as well as providing a powerful final artefact in public space that can visibilise the issue of feminicide among migrant women in an empathetic and powerful way. The process of painting brings together feminist activists and the families and friends of feminicide victims in ways that can tighten the space of relations between members of collectives and other migrant women. As finished products, murals can emphasise the humanity of victims of feminicide in wider collective memory, which contrasts with dominant discourses that are profoundly harmful to marginalised migrant women. In a context of increasing gender-based violence, feminicide and impunity, and given the vulnerabilities to violence associated with migration for many women, the Las RestaurAmoras murals help strengthen much needed protective networks among women and provide an important feminist counter-narrative in contemporary Quintana Roo.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to the editors, Cathy McIlwaine and Megan Ryburn, for inviting me to be part of this special issue, and to them and the anonymous external reviewer for their careful revision of earlier versions of this paper and their valuable feedback. As always, I am eternally grateful to the other members of Las RestaurAmoras for the opportunity to accompany each other throughout this project, and to the families and friends of the victims whose murals we have painted with love, care and anger, for allowing us to be part of their stories. The research which informed this paper was carried out as part of my Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) 1 + 3 scholarship, ESRC award number ES/P000746/1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Some theorists use the term femicide/femicidio and others feminicide/feminicidio. Throughout this paper I use feminicide to align with the majority of Latina scholarship, except where the scholars I reference use the term femicide in their work.

2 I am unlikely to be referred to by others as a migrant or to refer to myself as such, despite not being native to Mexico. My race, nationality, first language, employment status, place of work, and the freedom I have had in choosing to live elsewhere, mean I am more likely to be considered an ex-pat or a tourist. I discuss this in more depth in the methodology and positionality section.

3 The alerta de violencia de género contra las mujeres (AVGM) is a mechanism designed to protect women and girls from violence and ultimately eradicate femicidal violence, through the employment of emergency measures. Activating this alert means the federal and state governments recognise the high rates of gender-based violence taking place in particular municipalities. However, AVGMs are heavily criticised by feminist activists who see them as simulation from authorities as opposed to effective action to guarantee women’s security (see Rodríguez Pedraza Citation2018). By October 2021, AVGMs had been activated in 632 municipalities in 22 states. https://www.gob.mx/inmujeres/acciones-y-programas/alerta-de-violencia-de-genero-contra-las-mujeres-80739

5 They are Alejandra, Dayana, Jeni, Laura and Lupe. All names are pseudonyms.

7 Interview with Laura

11 Interview with Alejandra

References

- Ahmed, S. 2017. Living a Feminist Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Backe, E. L. 2020. “Capacitating Care: Activist Anthropology in Ethnographies of Gender-Based Violence.” Feminist Anthropology 1 (2): 192–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/fea2.12022.

- Bishop, C. 2006. “The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents.” Artforum. [Online]. Accessed 9 February 2022. https://www.artforum.com/print/200602/the-social-turn-collaboration-and-its-discontents-10274.

- Bogerts, L. 2017. “Mind the Trap: Street Art, Visual Literacy, and Visual Resistance.” Street Art & Urban Creativity Scientific Journal 3 (2): 6–10.

- Bourriaud, N. 2002. Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les presses du reel.

- Castañeda Salgado, M. P. 2016. “Feminicide in Mexico: An Approach Through Academic, Activist and Artistic Work.” Current Sociology 64 (7): 1054–1070. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116637894.

- Castellanos, M. B. 2010. Return to Servitude: Maya Migration and the Tourist Trade in Cancun. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Castro Sánchez, A. M. 2018. “El lugar del arte en las acciones políticas Feministas.” Configurações 22: 11–30.

- Cerva Cerna, D. 2020. “La protesta feminista en México. La misoginia en el discurso institucional y en las redes sociodigitales.” Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales 240: 177–205.

- Corcoran, A. 2020. “Challenging State-Led Political Violence with Art Activism. Focus on Borders.” In Cultures of Violence : Visual Arts and Political Violence, edited by R. in Kinna, and G. Whiteley, 79–99. London: Routledge.

- Coronado, G. 2020a. “Memorias de dolor y construcción de exposiciones: hablar de feminicidio.” Cadernos de Sociomuseologia 60 (16): 63–79. https://doi.org/10.36572/csm.2020.vol.60.04.

- Coronado, G. 2020b. “No Estamos Todas: Ilustrando Memorias.” Iberoamérica Social 16: 173–201.

- Corradi, C., et al. 2016. “Theories of Femicide and Their Significance for Social Research.” Current Sociology 64 (7): 975–995. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392115622256.

- Cuevas, S. 2021. “Quintana Roo, la entidad con más inmigrantes mexicanos, y Guerrero con más emigrantes.” El Financiero. [Online]. Accessed 1 September 2021. https://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/nacional/quintana-roo-la-entidad-con-mas- inmigrantes-mexicanos-y-guerrero-con-mas-emigrantes/.

- Danchev, A., and D. Lisle. 2009. “Introduction: Art, Politics, Purpose.” Review of International Studies 35: 775–779. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210509990179.

- DataMexico. 2021. Quintana Roo. [Online]. Accessed 1 April 2022. https://datamexico.org/es/profile/geo/quintana-roo-qr.

- Driver, A. 2015. More or Less Dead: Feminicide, Haunting, and the Ethics of Representation in Mexico. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

- Elias, J., and S. M. Rai. 2015. “The Everyday Gendered Political Economy of Violence.” Politics & Gender 11 (2): 424–429. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X15000148.

- Elias, J., and S. M. Rai. 2019. “Feminist Everyday Political Economy: Space, Time, and Violence.” Review of International Studies 45 (2): 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210518000323.

- Enloe, C. 2014. Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Félix de Souza, N. M. 2019. “When the Body Speaks (to) the Political: Feminist Activism in Latin America and the Quest for Alternative Democratic Futures.” Contexto Internacional 41 (1): 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-8529.2019410100005.

- Fernández Rodríguez, A. G., et al. 2020. “Migración interna y dinámicas laborales en la industria turística de la Riviera Maya, Quintana Roo, México.” Abra 40 (60): 77–98.

- Freedman, J. 2016. “Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Against Refugee Women: A Hidden Aspect of the Refugee “Crisis”.” Reproductive Health Matters 24 (47): 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhm.2016.05.003.

- Gago, V. 2018. “#WeStrike: Notes Toward a Political Theory of the Feminist Strike.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 117 (3).

- Gago, V., and M. Malo. 2020. “Introduction: The New Feminist Internationale.” South Atlantic Quarterly 119 (3): 620–632. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-8601458.

- Gideon, Jasmine. 2024. “Crafting Arts-Based Stories of Exile, Resistance and Trauma Among Chileans in the UK.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (13): 3319–3337. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2024.2345994.

- Gogarty, L. A. 2017. “‘Usefulness’ in Contemporary Art and Politics.” Third Text 31 (1): 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2017.1364920.

- Hammersley, M., and P. Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography Principles in Practice. Third edition. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Haraway, D. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” In The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader: Intellectual and Political Controversies, edited by S. G. Harding, 81–102. London: Routledge.

- Heidenry, R. 2014. “The Murals of El Salvador: Reconstruction, Historical Memory and Whitewashing.” Public Art Dialogue 4 (1): 122–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/21502552.2014.878486.

- Held, M. B. E. 2019. “Decolonizing Research Paradigms in the Context of Settler Colonialism: An Unsettling, Mutual, and Collaborative Effort.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918821574.

- Jeffreys, S. 2009. The Industrial Vagina: The Political Economy of the Global sex Trade. New York: Routledge.

- Karl, S. 2014. “Rehumanizing the Disappeared: Spaces of Memory in Mexico and the Liminality of Transitional Justice.” American Quarterly 66 (3): 727–748. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2014.0050.

- Kinna, R., and G. Whiteley. 2020. “Introduction.” In Cultures of Violence: Visual Arts and Political Violence, edited by R. Kinna, and G. Whiteley, 1–15. Milton: Routledge.

- Lagarde, M. 2005. ¿A qué le llamamos feminicidio? Ciudad de México.

- Lagarde, M. 2006. El derecho humano de las mujeres a una vida libre de violencia.

- Lamas, M. 2021. Dolor y Política. México: Océano.

- Las Tres Muertes de Marisela Escobedo. 2020. Directed by Perez Osorio, C. México: Scopio, Netflix Studios.

- Letherby, G. 2015. “Gender-Sensitive Method/Ologies.” In Introducing Gender and Women’s Studies. 4 ed. edited by D. Richardson, and V. Robinson, 76–94. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lines, T. 2022. “Luchar por estas mujeres en relaidad es también luchar por mi”: lo político en el acto de pintar murales de víctimas de feminicidio.” In Género: Rabia, Ritmo, Ruido, Risa y Respons-habilidad, edited by M. Belausteguigoitia, 91–104. Mexico City: CIEG-UNAM.

- Lopes Heimer, Rosa dos Ventos. 2024. “Embodying Intimate Border Violence: Collaborative Art-Research as Multipliers of Latin American Migrant Women’s Affects.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (13): 3275–3299. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2024.2345991.

- Macías, K. 2019. “Feminicidio en México y el arte que combate al olvido.” Entretextos 31: 115–124.

- Manning, J. 2018. “Becoming a Decolonial Feminist Ethnographer: Addressing the Complexities of Positionality and Representation.” Journal of Management Learning 49 (3): 311–326.

- McIlwaine, Cathy. 2024. “Creative Translation Pathways for Exploring Gendered Violence Against Brazilian Migrant Women Through a Feminist Translocational Lens.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (13): 3252–3274. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2024.2345990.

- McIlwaine, Cathy, and Megan Ryburn. 2024. “Introduction: Towards Migration-violence Creative Pathways.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (13): 3229–3251. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2024.2345988.

- Meikle, T. 2020. “The Multivalency of Memorial Murals in Kingston, Jamaica: A Photo-Essay.” Interventions 22 (1): 106–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2019.1659163.

- Monárrez Fragoso, J. 2000. “La cultura del feminicidio en Ciudad Juárez, 1993-1999.” Frontera norte 12 (23): 87–117.

- Monárrez Fragoso, J. 2004. “Elementos de análisis del feminicidio sexual sistémico en Ciudad Juárez para su viabilidad jurídica.” México. [Online]. Accessed 1 August 2021. http://mujeresdeguatemala.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Elementos-del-feminicidio-sexual-sistémico.pdf.

- Monárrez Fragoso, J. E., et al. 2018. “Feminicide: Impunity for the Perpetrators and Injustice for the Victims.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Criminology and the Global South, edited by K. Carrington, 913–929. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mouffe, C. 2007. “Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces.” Art and Research 1(2). [Online]. Accessed 30 October 2021. http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v1n2/mouffe.html.

- Oakley, A. 2015. “Interviewing Women Again: Power, Time and the Gift.” Sociology 50 (1): 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038515580253.

- Observatorio de Seguridad y Género de Quintana Roo – OSEGE. 2021. Reporte sobre incidencia delictiva primer semester 2021.

- Oliveira, C., et al. 2018. “Assessing Reported Cases of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence, Causes and Preventive Strategies, in European Asylum Reception Facilities.” Globalization and Health 14 (1): 48–48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0365-6.

- Orozco, E. F. 2017. “Feminicide and the Funeralization of the City: On Thing Agency and Protest Politics in Ciudad Juárez.” Theory & Event 20 (2): 351–380.

- Orozco, E. F. 2019. “Mapping the Trail of Violence: The Memorialization of Public Space as a Counter-Geography of Violence in Ciudad Juárez.” Journal of Latin American Geography 18 (3): 132–157. https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2019.0053.

- Pain, R., and L. Staeheli. 2014. “Introduction: Intimacy-Geopolitics and Violence.” Area 46 (4): 344–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12138.

- Petersen, A. R., and S. D. Nielsen. 2021. “The Reconfiguration of Publics and Spaces Through Art: Strategies of Agitation and Amelioration.” Journal of Aesthetics and Culture 13 (1): 1898766.

- Phillimore, J., et al. 2022. ““We Are Forgotten”: Forced Migration, Sexual and Gender-Based Violence, and Coronavirus Disease-2019.” Violence Against Women 28 (9): 2204–2230. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012211030943.

- Pollock, G. 2013. Editor’s Introduction in G Pollock ed. Visual Politics of Psychoanalysis: Art and the Image in Post-Traumatic Cultures. London: I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited. Pp1-22.

- Pollock, G. 2018. “Action, Activism, and Art and/as Thought: A Dialogue with the Artworking of Sonia Khurana and Sutapa Biswas and the Political Theory of Hannah Arendt.” E-Flux 92. [Online]. Accessed 7 August 2021. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/92/204726/action-activism-and-art-and-as-thought-a-dialogue-with-the-artworking-of-sonia-khurana-and-sutapa-biswas-and-the-political-theory- of-hannah-arendt/.

- PorEsto. 2020. “Quintana Roo, entre los estados con más casos de abuso sexual.” Por Esto. [Online]. Accessed 13 May 2021. https://www.poresto.net/quintana- roo/2020/10/5/quintana-roo-entre-los-estados-con-mas-casos-de-abuso- sexual-216035.html.

- Reyes Cruz, M. 2008. “What If I Just Cite Graciela? Working Toward Decolonizing Knowledge Through a Critical Ethnography.” Qualitative Inquiry 14 (4): 651–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800408314346.

- Rodríguez Pedraza, Y. 2018. “La alerta de género en México: su falta de efectividad.” Prospectiva Jurídica 9 (18): 49–68.

- Rolston, B. 2003. “Changing the Political Landscape: Murals and Transition in Northern Ireland.” Irish Studies Review 11 (1): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0967088032000057861.

- Rolston, B., and S. Ospina. 2017. “Picturing Peace: Murals and Memory in Colombia.” Race & Class 58 (3): 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396816663387.

- Ryburn, Megan. 2024. “Animating Migration Journeys from Colombia to Chile: Expressing Embodied Experience Through Co-Produced Film.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (13): 3300–3318. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2024.2345993.

- Segato, R. 2012. Femigenocidio y feminicidio: una propuesta de tipificación. Herramienta 49. [Online]. Accessed 12 June 2021. https://herramienta.com.ar/?id=1687.

- Segato, R. 2013. La escritura en el cuerpo de las mujeres asesinadas en Ciudad Juárez: territorio, soberanía y crímenes de segundo estado. Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón.

- Segato, R. L. 2014. “Las nuevas formas de la guerra y el cuerpo de las mujeres.” Sociedade e Estado 29 (2): 341–371. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-69922014000200003.

- Segovia, C. R., and M. H. Jasso. 2020. “Las mujeres que buscan a personas desaparecidas en México se enfrentan a múltiples retos.” Open Democracy. [Online] Accessed 3 September 2021. https://www.opendemocracy.net/es/mujeres-personas-desaparecidas-méxico/.

- Sheringham, Olivia, Helen Taylor, and Duffy-Syedi Kate. 2024. “Care-Full Resistance to Slow Violence: Building Radical Hope Through Creative Encounters with Refugees During the Pandemic.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (13): 3359–3378. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2024.2345999.

- Stack, C. B. 1993. “Writing Ethnography: Feminist Critical Practice.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 13 (3): 77–89. https://doi.org/10.2307/3346744.

- Stanley, L., and S. Wise. 1993. Breaking Out Again: Feminist Ontology and Epistemology. Second Edition. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Thambinathan, V., and E. A. Kinsella. 2021. “Decolonizing Methodologies in Qualitative Research: Creating Spaces for Transformative Praxis.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211014766.

- Tickner, J. A. 1992. Gender in International Relations : Feminist Perspectives on Achieving Global Security. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Torres, R. M., and J. D. Momsen. 2005. “Gringolandia: The Construction of a New Tourist Space in Mexico.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95 (2): 314–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2005.00462.x.

- True, J. 2010. “The Political Economy of Violence Against Women: A Feminist International Relations Perspective.” Australian Feminist Law Journal 32 (1): 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13200968.2010.10854436.

- True, J. 2012. The Political Economy of Violence Against Women. Cary: Oxford University Press.

- True, J., and M. Tanyag. 2018. “Violence Against Women/Violence in the World: Toward a Feminist Conceptualization of Global Violence.” In Routledge Handbook of Gender and Security, edited by C. E. in Gentry, L. J. Shepherd, and L. Sjoberg, 15–26. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Uddin, N. 2011. “Decolonising Ethnography in the Field: An Anthropological Account.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 14 (6): 455–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2011.611382.

- Vanyoro, K. P., et al. 2019. “Migration Studies: From Dehumanising to Decolonising.” London School of Economics. [Online]. Accessed: 11 February 2022. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/highereducation/2019/07/19/migration-studies-from-dehumanising-to-decolonising/.

- Vargas Martínez, F. C., and A. Díaz. 2020. “Acción política frente a la violencia feminicida en México. Experiencias de una Investigación Activista Feminista.” Empiria: Revista de Metodología de Ciencias Sociales 50: 91–114.

- Wright, M. W. 2011. “Necropolitics, Narcopolitics, and Femicide: Gendered Violence on the Mexico-U.S. Border.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 36 (3): 707–731. https://doi.org/10.1086/657496.