ABSTRACT

The study presented in this paper examined intersectional discrimination against individuals with multiple minority identities in the housing market, specifically those identifying as Arab Muslims. By sending inquiries from three fictitious applicants – a Swedish Christian, an Arab Christian, and an Arab Muslim – to 1,200 landlords in Sweden, we analyzed differences in landlord responses. Results showed the Swedish Christian received the most positive replies, followed by the Arab Christian, with the Arab Muslim receiving the fewest. The study underscores the compounded discrimination faced by those with multiple minority identities and challenges the conflation of ethnic and religious identities in prior research.

Introduction

The United Nations identifies access to adequate housing as a fundamental human right. Despite this, compelling global research – primarily driven by rigorous field experiments – has consistently revealed that ethnic and racial minorities face considerable discrimination in the rental housing market (Auspurg, Schneck, and Hinz Citation2019; Bertrand and Duflo Citation2017; Flage Citation2018; Quillian, Lee, and Honoré Citation2020; Riach and Rich Citation2002). Initially, field experiments were exclusively audit tests, during which testers would directly engage with landlords in person or over the phone to inquire about rental availability (Riach and Rich Citation2002). Most of these studies were focused on investigating discrimination against Black people within the United States. However, following the studies conducted by Carpusor and Loges (Citation2006) in the United States and Ahmed and Hammarstedt (Citation2008) in Sweden, there was a shift in the methodology and, to some extent, the research focus. The dominant approach for conducting field experiments on discrimination in the rental housing market became online correspondence tests involving written applications. This shift occurred because correspondence tests offer researchers a higher degree of experimental control than audit tests (Ahmed and Hammarstedt Citation2008; Riach and Rich Citation2002). Furthermore, research into discrimination against Arab Muslim individuals saw a significant surge, particularly within European countries (Auspurg, Schneck, and Hinz Citation2019; Flage Citation2018).

The standard way for testing discrimination against Arab Muslim individuals in these experiments involves using Arabic-Muslim-sounding names alongside non-Arabic-Muslim-sounding names for apartment seekers and then observing any differences in responses from the landlords. An unsettled question in this line of research is, however, whether people with Arabic-Muslim-sounding names are discriminated against because they are perceived to be Arabs, or because they are perceived to be Muslims, or because they are perceived to be both (Adida, Laitin, and Valfort Citation2010; Ahmed and Hammarstedt Citation2008; Bartkoski et al. Citation2018). This difficult question is essential to answer from a theoretical, empirical, legal, and policy perspective since ‘Arab’ and ‘Muslim’ denote separate ethnic and religious components of a person’s identity. For example, we need to identify the attributes that make minorities targets of intolerance in order to develop effective anti-discrimination interventions.

In Sweden, which is the context of our study, Arab Muslim individuals constitute a significant minority group. The population of Sweden is slightly over ten million people (Statistics Sweden Citation2024a), and approximately 20 percent of this population is foreign-born (Statistics Sweden Citation2024b). Precise data on ethnicity and religion are difficult to obtain since such information is not recorded in Sweden. However, reasonable estimates can be derived based on various sources. Among the foreign-born population, individuals from the Arab world constitute the largest ethnic group after native Swedish people. For instance, people born in Iraq and Syria only number about 350,000 (Statistics Sweden Citation2024b). Christianity is the predominant religion in Sweden, with more than 50 percent of the population affiliated with the Church of Sweden (Swedish Institute Citation2024). Islam is the second largest religion, with estimates suggesting that around ten percent of the population is Muslim (Living History Forum Citation2024). Consequently, Swedish Christians are the majority ethnic and religious group, while Arabs represent a minority ethnic group and Muslims a minority religious group. There is, of course, a significant overlap between the Arab and Muslim populations.

Intersectionality, a framework acknowledging the overlap of multiple identity facets (Crenshaw Citation1989; Citation1991), plays a significant role in the negative experiences of Arab Muslim individuals (Brown Citation2019; Lauwers Citation2019; Rana Citation2007). Given historical and contemporary discrimination, these individuals face significant hurdles due to the intersection of ethnic and religious biases, often compounded by other identity aspects like gender or socioeconomic status (Love Citation2017; Morey, Yaqin, and Forte Citation2021; Morgan and Poynting Citation2016; Turpin-Petrosino Citation2022). Unfortunately, current legal structures and housing policies often overlook these intersectional forms of discrimination, providing insufficient protection. A thorough examination of these dynamics is imperative for academic knowledge and informing policymakers, housing providers, and advocates about the distinct barriers this community faces. Better understanding can lead to more effective interventions, policy changes, and educational programs, ultimately fostering a more equitable housing market. Despite the importance of this issue, current research lacks a comprehensive examination of the multiple facets of discrimination faced by Arab Muslim individuals in the rental housing market. Therefore, our research aspired to bridge this critical knowledge gap, offering insights into multifaceted discrimination against Arab Muslim people and potentially catalyzing a new wave of scholarly inquiries specifically centered around intersectionality in the rental housing market.

We conducted a field experiment in the Swedish rental housing market to examine intersectional discrimination against Arab Muslim people. We dispatched applications to actual landlords with vacant apartments, purporting to come from three fictional clergymen. Each landlord received an application from a Swedish priest, an Arab priest, or an Arab imam. Ethnicity was suggested using Swedish- and Arabic-sounding names, while the applicants’ occupations and workplaces indicated their religious affiliations. We then examined the likelihood of receiving a positive response from a landlord in a general sense, as well as the likelihood of receiving an immediate invitation to view an apartment. This design enabled us to compare the outcomes of the Arab versus Swedish applicant (while keeping the religion constant), and the outcomes of the Muslim versus Christian applicant (while keeping ethnicity constant).

The intersectionality theory posits that discrimination is not just a result of a single aspect of one’s identity but an amalgamation of multiple intersecting identities such as race, gender, socioeconomic status, and religion (Crenshaw Citation1989; Citation1991). This suggests a cumulative disadvantage and more considerable discrimination, as the combined effects of these identities forge a unique, intricate bias that exceeds the sum of its components. Each additional marginalized identity can potentially intensify the discrimination experienced. Therefore, intersectionality theory not only anticipates the existence of discrimination but also predicts a broader, more complex, and deeply entrenched framework of discrimination. By Allport’s (Citation1954) concept of ingroup formation and based on the ethnic and religious composition of the Swedish population discussed earlier, we assumed that Swedish Christian individuals would form the innermost group within Swedish society among the three intersectional identities defined in our experiment. We further assumed that the social distance to Arab Muslim individuals would be greater than that to Arab Christian individuals, given the shared faith between Swedish Christians and Arab Christians.

From an economic theoretical standpoint, a person’s intersectional identity can be linked with multiple dimensions of taste-based discrimination (Becker Citation1957). Take, for instance, an individual identifying as an Arab Muslim. This person may not just face discrimination on a single front but rather on several fronts, including ethnicity, religion, and potentially gender. Negative biases or animosity linked to each of these identities may coalesce, leading to an amplified discriminatory effect. This can manifest in a housing context, where these biases may influence landlords when making rental decisions. Besides this layered taste-based discrimination, a person with intersecting identities might also face heightened statistical discrimination (Arrow Citation2015; Phelps Citation1972). This type of discrimination occurs when decisions about or predictions for an individual are based on stereotypes and statistical information about the group to which they belong rather than their individual characteristics. In the housing market, landlords may form assumptions about Arab Muslim applicants driven by stereotypes and average statistical traits associated with each aspect of their identity. The mixture of these identities brings added complexity and potential bias, leading to increased uncertainties and, consequently, a heightened degree of statistical discrimination. Fundamentally, from an economic standpoint, individuals possessing intersecting identities are potentially subjected to intensified taste-based and statistical discrimination. These two forms of discrimination can compound, establishing substantial barriers to equal treatment and opportunities in sectors such as housing. Empirically distinguishing between these two economic theories of discrimination is a delicate matter, as both forms may coexist and reinforce each other. Nonetheless, some empirical attempts have been made. For example, Ahmed, Andersson, and Hammarstedt (Citation2010) varied the amount of information provided about the applicant to reduce or increase uncertainty about the applicant’s qualities as a tenant. They found that although increasing the information (thereby decreasing uncertainty) about the tenant improved landlord response probabilities for all applicants, the ethnic gap between applicants persisted. This gap was not eliminated when uncertainty about tenant qualities (and thereby the risk of statistical discrimination) was removed, suggesting that the discrimination observed was taste-based.

We hypothesized that the Swedish Christian applicant would fare better than the Arab Christian applicant, and that the Arab Christian applicant would, in turn, fare better than the Arab Muslim applicant. Our results indeed corroborate this assumption, demonstrating substantial intersectional discrimination against Arab Muslim individuals in the Swedish rental housing market. To put it succinctly, our data implies that an Arab Christian applicant must apply to twice as many apartments and an Arab Muslim applicant must apply to four times as many apartments than a Swedish Christian applicant in order to receive a comparable number of invitations to view apartments from landlords in the Swedish rental housing market.

The concept of intersectionality, central to our study, requires a precise articulation beyond its mention as a framework for understanding the overlap of multiple identities. Intersectionality, as originally coined by Crenshaw (Citation1989; Citation1991), delves into the complex and often nonlinear ways in which different axes of identity – such as ethnicity and religion – interact and amplify discrimination beyond the mere sum of their parts. Our experimental design, comparing responses to individuals with varying degrees of minority status across these dimensions, aimed to shed light on the nuanced discrimination landscape in the Swedish housing market. However, we acknowledge that intersectionality entails more than identifying additive effects; it seeks to understand the unique experiences that emerge at the confluence of multiple discriminated identities. While our study contrasts the experiences of individuals with no minority status, minority status on one dimension, and minority status on two dimensions, we recognize the limitation in fully capturing the interactive effects as intersectional theory prescribes. This is due to the absence of certain conditions in our study, such as the specific case of a Swedish imam, which would not have been realistic and credible to include in the Swedish context. This omission was informed by practical constraints and the focus on the most prevalent forms of discrimination within the context of our research. The implications of these design decisions on our study’s ability to conclusively determine intersectional effects – be they additive or interactive – are critical to the interpretation of our findings.

In addressing the multifaceted nature of discrimination within the housing market, our study is situated within a broader context of prevailing stereotypes and prejudices against Arab (Ahmadi et al. Citation2020; Wolgast, Björklund, and Bäckström Citation2018) and Muslim (Bevelander and Otterbeck Citation2013; Larsson and Stjernholm Citation2016) individuals in Sweden. The societal backdrop against which this discrimination unfolds is marked by nuanced and deeply ingrained biases (Agerström and Rooth Citation2009; Ahmed Citation2010), ranging from misconceptions and erroneous representations (Bevelander and Otterbeck Citation2013; Steiner Citation2015) to broader geopolitical narratives that have seeped into local contexts (Larsson Citation2005; Sander Citation2006). Previous field experiments in Sweden and across Europe have documented discrimination based on ethnicity and/or religion (Auspurg, Schneck, and Hinz Citation2019; Lippens, Vermeiren, and Baert Citation2023), yet the intersection of these identities – particularly for Arab Muslims – remains underexplored.

Research by Olseryd, Wallin, and Repo (Citation2021) demonstrates that stereotypes and prejudices against Muslims in Sweden are both pervasive and varied. These negative perceptions often portray Muslims as inherently different, culturally incompatible, and economically burdensome. Such stereotypes are reinforced through political and media discourses, which contribute to an ‘us versus them’ mentality. Olseryd, Wallin, and Repo (Citation2021) reveal that these prejudices are not confined to extremist fringes but are widespread across different segments of society, influencing daily interactions and social attitudes. Hate crimes and violations against Muslims encompass threats, harassment, defamation, incitement, violence, and microaggressions. In housing, these pervasive stereotypes can significantly impact landlords’ decisions. The prejudices against Muslims, as detailed by Olseryd, Wallin, and Repo (Citation2021), suggest that landlords may harbor unfounded fears about the economic reliability and social compatibility of Muslim tenants. These biases can lead to discriminatory practices, where landlords, consciously or unconsciously, prefer non-Muslim tenants over Muslim ones. Such discrimination not only exacerbates housing difficulties for Muslims but also reinforces their social and economic exclusion. These dynamics are crucial for forming the current hypotheses, which posit that stereotypes and prejudices against Muslims contribute to systematic barriers in the housing market, affecting their ability to secure rental properties on equal terms with others.

In this study, we explored discrimination against religious Arab and Swedish individuals – specifically imams and priests – in the housing market through a field experiment. By employing a large sample and utilizing correspondence tests, our research offers significant insights into discriminatory practices within housing transactions, broadening our understanding of discrimination in this crucial sector. By employing correspondence tests, this study builds upon existing methodologies to detect discrimination and deepens our understanding by examining the combined (intersectional) effects for Arab Muslim individuals. It sheds light on how specific stereotypes and prejudices against these groups manifest in the rental housing market, contributing to a nuanced understanding of discrimination. The selection of our targets – individuals identified as Swedish Christians, Arab Christians, and Arab Muslims – was informed by the intent to dissect the layered experiences of discrimination that uniquely impact Arab Muslims at the intersection of ethnic and religious identity. By contextualizing our investigation within the specificities of the Swedish socio-cultural landscape, this study aimed to enrich the existing body of knowledge, offering insights into the nuanced ways intersectional discrimination operates and informing more targeted anti-discrimination interventions.

Method

We conducted our correspondence test field experiment in March 2022 among 1,200 real landlords who had advertised vacant apartments in the Swedish rental housing market. We located the vacant apartments on a major online marketplace for private rental apartments in Sweden. We applied to one- to four-room apartments in Sweden’s three largest counties: Skåne län, Västra Götalands län, and Stockholms län. The sample size was determined with 95 percent power and α = .05 using a power analysis based on previous studies on ethnic discrimination in the rental housing market in Sweden (Ahmed, Andersson, and Hammarstedt Citation2010; Carlsson and Eriksson Citation2014). In Ahmed, Andersson, and Hammarstedt (Citation2010), the probability of receiving an apartment viewing invitation was 25 percent for male applicants with Swedish-sounding names and 16 percent for those with Arabic-Muslim-sounding names. Carlsson and Eriksson (Citation2014) reported corresponding probabilities of 26 and 14 percent, respectively. Based on data from the former study, sample size calculations performed using G*Power (Faul et al. Citation2007; Citation2009) suggested a required sample size of 433 for each condition. Calculations based on the latter study indicated a need for 238 observations per condition. Consequently, we aimed for an anticipated sample size of 400 for each condition. The experiment was preregistered at AsPredicted (https://aspredicted.org/e4ia2.pdf).

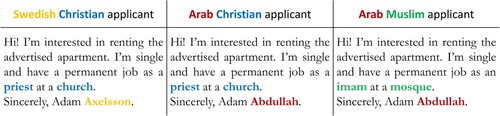

Our experiment was designed such that the fictitious applicant was either a priest employed at a church, or an imam employed at a mosque. Therefore, we had three applicants: a priest with a Swedish-sounding male name, a priest with an Arabic-sounding male name, and an imam with an Arabic-sounding male name. We assigned all applicants the first name ‘Adam,’ a name prevalent among followers of all Abrahamic religions. The Swedish Christian applicant was given the surname ‘Axelsson,’ a typical Swedish surname. Both the Arab applicants were assigned the surname ‘Abdullah,’ a common name among Arab Christians and Muslims. Both surnames started with the same letter, consisted of the same number of letters, and had the same number of syllables. As a result, each landlord with a vacant apartment was randomly assigned to receive an application from either a Swedish Christian, an Arab Christian, or an Arab Muslim applicant. The applicant’s ethnicity was implied through their Swedish- or Arabic-sounding names, while their religious affiliation was suggested by their professional role as either a priest or an imam. illustrates the experimental conditions and the structure of the letter of interest (application) sent to the landlords. The original Swedish versions are provided in in the Appendix.

Figure 1. Experimental conditions and framing.

Note: English translation of the original letter of interest (application) in Swedish that was sent to the landlords from each type of fictitious applicant. The original Swedish formulations are available in in the Appendix. Ethnicity was signaled through Swedish-sounding (yellow) and Arabic-sounding (red) surnames, and religious affiliation was signaled through occupation – a priest at a church (blue) and an imam at a mosque (green).

Landlord responses were typically received either immediately or within one to two days. Therefore, we allowed a week to pass after the final application was submitted in the experiment, ensuring landlords had ample time to respond before we ceased recording their responses. The average response rate from landlords was 55 percent, and these responses constituted our outcome variables. We defined two outcome variables: ‘positive landlord response’ and ‘apartment viewing invitation.’ A ‘positive landlord response’ was assigned a value of 1 whenever the landlord reacted favorably to the fictitious applicant’s interest in an apartment. This favorable reaction was indicated by inviting further communication, requesting more information about the applicant, or inviting the applicant to view the apartment – in essence, if the landlord did not immediately reject the application. This variable was set to 0 if the landlord declined the application or did not respond. The average positive response rate was 34 percent. The ‘apartment viewing invitation,’ a more stringent measure of a positive landlord response, was assigned a value of 1 when a landlord invited the fictitious applicant for an apartment viewing without asking for additional information, and 0 otherwise. The average apartment viewing invitation rate was 13 percent.

Our primary explanatory variables were the applicants’ intersectional identities: ethnicity, indicated through names, and religious affiliation, indicated through occupation and workplace (i.e. the experimental conditions, randomized across landlords). These identities were coded as three separate dummy variables: Swedish Christian, Arab Christian, and Arab Muslim. Out of 1,200 landlords, 33 percent received an inquiry from the Swedish Christian applicant, 36 percent from the Arab Christian applicant, and 31 percent from the Arab Muslim applicant.

We also recorded several control variables. First, we noted five apartment characteristics: the number of rooms (average of 2), square footage (average of 48 square meters), whether the contract was temporary (28 percent), whether the apartment was shared (16 percent), and the rent in Swedish kronor (average of 9,753).

Second, we noted two landlord characteristics: whether the landlord was identifiable as a woman (47 percent) or a man (53 percent) and whether the landlord was an individual (92 percent) or a company (8 percent). We acknowledge the assumption of this experiment that relevant landlord characteristics are evenly distributed across the randomized conditions. While we were able to code for and control landlord gender and whether the landlord operated as an individual or a company, there indeed are additional landlord attributes that could impact outcomes that were beyond our capacity to measure from the advertisements. Hence, we included controls for landlord gender and company status based on available information in advertisements and existing research suggesting that individuals might exhibit more selective behavior in tenant selection compared to companies and that gender dynamics could influence response rates (Ahmed and Hammarstedt Citation2008).

Lastly, we coded dummy variables for county and time (application day) fixed effects. Among the 1,200 landlords, 17 percent were in Skåne län, 25 percent in Västra Götalands län, and 58 percent in Stockholms län. Applications were distributed over 18 days. Randomization assured the neutrality of temporal factors in our analysis. The Appendix contains further details: defines all variables in the data, summarizes the statistics for our data, verifies successful randomization, and and provide correlation matrices.

Our analysis proceeded in two distinct stages. Initially, we employed contingency tables to perform χ2 tests on various subsamples. This approach aimed to identify differences in the proportion of applications that resulted in a positive landlord response (or an apartment viewing invitation) between the Swedish Christian, Arab Christian, and Arab Muslim applicants. In the second stage, we shifted our focus to control for potential confounds not accounted for in the initial χ2 tests. We conducted regression analyses using linear probability models. Within these models, the Swedish Christian served as the reference. This decision enabled us to estimate the marginal change in probabilities of receiving a positive landlord response (or an apartment viewing invitation) for the Arab Christian and Arab Muslim applicants, respectively, compared to the Swedish Christian applicant. Specifically, our regression models did not employ contrast coding; we directly utilized the binary variables indicating Arab Christian and Arab Muslim applicants to measure their comparative likelihoods of receiving positive landlord responses against the Swedish Christian (baseline) applicant. This approach facilitated a clear and interpretable assessment of the differential impact of applicant background on landlord responses, addressing the nuanced dynamics of discrimination in the housing market. All analyses were performed using Stata 17.

Ethics approval from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority was not required in accordance with §§3–4 of the Ethical Review Act in Sweden (Swedish Code of Statutes Citation2003:460), as no personal identifiable information was collected during the experiment. The data and Stata do-file supporting this paper’s findings are available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10027620).

Results

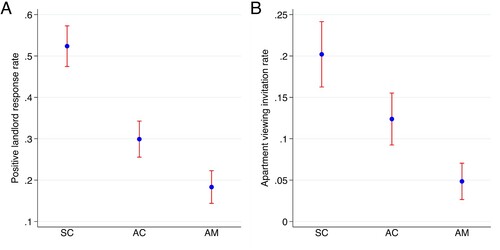

We followed our preregistered plan for hypothesis tests and analysis. Panel A in presents positive landlord response rates. The Swedish Christian applicant received a positive response from the landlords 52 percent of the time (210/401); the Arab Christian applicant received a positive response 30 percent of the time (128/428). This is a statistically significant difference, χ2 = (1, N = 829) = 43.26, p < .001. The Arab Muslim applicant received a positive response from the landlords 18 percent of the time (68/371). The positive landlord response rate difference between the Arab Christian and the Arab Muslim applicant was also statistically significant, χ2 = (1, N = 799) = 14.39, p < .001.

Figure 2. Mean landlord response rate by applicant type.

Note: SC = Swedish Christian, AC = Arab Christian, and AM = Arab Muslim. Vertical red lines are 95 percent confidence intervals. NSC = 401, NAC = 428, and NAM = 371. Blue dots represent the probability of receiving a positive response (i.e. a nonrejection) from a landlord (Panel A) and the probability of receiving an immediate invitation from a landlord to view a vacant apartment (Panel B).

Panel B of presents the apartment viewing invitation rates. The probability of receiving an immediate invitation to view an apartment was 20 percent (81/401) for the Swedish Christian applicant. The corresponding probabilities for the Arab Christian and the Arab Muslim applicants were 12 percent (53/428) and 5 percent (18/371), respectively. The difference between the Swedish Christian and the Arab Christian applicant and between the Arab Christian and the Arab Muslim applicant are both statistically significant, χ2 = (1, N = 829) = 9.33, p = .002, and χ2 = (1, N = 799) = 13.92, p < .001, respectively.

In other words, the Arab Christian applicant needed to apply for 1.7 times more vacant apartments than the Swedish Christian applicant to receive a comparable number of positive responses from the landlords. The Arab Muslim applicant needed to apply for 1.7 times more vacant apartments than the Arab Christian applicant to receive an equal number of positive responses. The Arab Muslim applicant needed to apply for almost three times more vacant apartments than the Swedish Christian applicant to receive the same number of positive responses. Similarly, our results showed that the Arab Muslim applicant needed to apply for 2.4 times as many vacant apartments as the Arab Christian applicant and four times as many vacant apartments as the Swedish Christian applicant to receive a comparable number of apartment viewing invitations.

Next, we proceeded with some regression analysis to control for potential confounds. and present the marginal effects of applicant type on the probability of receiving a positive employer response () and an apartment viewing invitation (), estimated using linear probability models. Model 1 in each table gives the marginal effects for the Arab Christian and Arab Muslim applicants, respectively, compared to the Swedish Christian applicant (the reference category), on the outcome variables, without controlling for any additional variables. These models replicate our results above. We gradually then add controls for apartment characteristics (Model 2), landlord characteristics (Model 3), and county and application day fixed effects (Model 4) to evaluate the robustness of our findings.

Table 1. Probability of receiving a positive landlord response.

Table 2. Probability of receiving an apartment viewing invitation.

Both tables show robust, substantial, and statistically significant effects for the Arab Christian and Arab Muslim applicants compared to the Swedish Christian applicant. Our results in show that the Arab Christian and the Arab Muslim applicants were 23 and 34 percentage points less likely than the Swedish Christian applicant, respectively, to receive a positive landlord response. Hence, the Arab Muslim applicant was 11 percentage points less likely than the Arab Christian applicant to receive a positive employer response. All differences are large in magnitude and highly significant.

Similarly, shows that the probability of receiving an apartment viewing invitation was 7 and 16 percentage points lower for the Arab Christian and Arab Muslim applicants, respectively, than for the Swedish Christian applicant. Hence, the Arab Muslim applicant had a 9 percentage point lower probability than the Arab Christian applicant of receiving an apartment viewing invitation. Again, all differences are large in magnitude and highly significant.

In the Appendix, we present additional analyses and robustness checks. First, we evaluated whether using probit models instead of the linear probability models reported in would change our estimations, results, or conclusions, given that our dependent variables are binary. – in the Appendix demonstrate that our results hold across different estimation methods. The estimates became slightly conservative with probit use, but not meaningfully so. Second, deviating from our pre-registered analysis plan, we also analyzed the interaction effects between the explanatory variables (experimental manipulation) and the available apartment and landlord characteristics. The results of these analyses for both outcome variables are in – in the Appendix. When we used positive landlord response as the dependent variable, only interactions with the temporary nature of the apartment contract proved weakly significant. Our findings suggest that if the contract was temporary, discrimination against Arab Christian and Arab Muslim applicants was smaller. All other interaction effects were statistically nonsignificant.

Furthermore, all interaction effects were nonsignificant when we used apartment viewing invitation as the dependent variable. Lastly, and in the Appendix offer an analysis with ‘landlord response’ (regardless of its positivity or negativity) as an outcome variable. Hence, landlord response is an even more inclusive dependent variable than positive landlord response, as it accounts for any reaction from the landlord. Our results revealed considerable differences in the probability of receiving a response from the landlord between the Swedish Christian and both Arab Christian and Arab Muslim applicants. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the likelihood of receiving a landlord response between the Arab Christian and Arab Muslim applicants. This suggests that discrimination against Arab applicants begins at the decision of whether a landlord responds to our applicants, and the disparity between Arab Christian and Arab Muslim applicants lies in the content of the landlord’s response.

Discussion

Our study conclusively establishes the existence of intersectional discrimination against Arab Muslim individuals within the Swedish rental housing market, illuminating the complex facets of bias experienced by this community. It sought to fill existing knowledge gaps about the intersection of ethnicity and religion-based discrimination, employing a correspondence test field experiment to distinguish and analyze the individual and combined effects of these identities. The outcomes manifestly demonstrate pervasive intersectional discrimination. Compared to the Arab Christian and Arab Muslim applicants, the Swedish Christian applicant received a significantly higher rate of positive responses from landlords. Further, the probability of an immediate invitation to view an apartment was a lot higher for the Swedish Christian applicant.

Our findings align with the intersectionality theoretical framework, which posits that discrimination results from the collective effects of multiple, intersecting identities – such as race, religion, gender, and socioeconomic status – rather than a singular identity trait (Collins and Bilge Citation2020; Davis and Lutz Citation2023). Thus, the study reinforces the notion that intersecting identities often exacerbate discrimination, creating additional barriers to equal treatment and opportunities across various sectors, including housing (Ghekiere, Martiniello, and Verhaeghe Citation2023; Wolifson, Maalsen, and Rogers Citation2023). From an economic perspective, the discrimination experienced by Arab Muslim individuals can be linked to taste-based and statistical discrimination. Taste-based discrimination refers to negative biases or animosity associated with specific identities (Becker Citation1957), while statistical discrimination occurs when decisions or predictions are guided by stereotypes rather than individual characteristics (Arrow Citation2015; Phelps Citation1972). In the rental housing market in Sweden, landlords might reject Arab Muslim applicants due to personal biases against Arabs, Muslims, or both (Yinger Citation1986). They may also rely on stereotypes related to ethnicity and religion, resulting in greater uncertainty and increased discrimination (Horr, Hunkler, and Kroneberg Citation2018).

Our research supports the hypothesis that Swedish Christian applicants experience a relative advantage in the Swedish rental housing market compared to Arab Christian and Arab Muslim applicants. The existence of discrimination against Arab Christian applicants suggests a substantial influence of ethnicity, while the intensified discrimination against Arab Muslim applicants indicates that religion further exacerbates this bias. Since men do worse in the rental housing market than women (Ahmed and Hammarstedt Citation2008), Arab Muslim men are likely to face at least three layers of discrimination in the rental housing market.

The implications of our study extend well beyond academia, offering valuable insights for policymakers, housing providers, and advocates. By illuminating the unique challenges faced by Arab Muslim individuals, our study enhances understanding of intersectional discrimination. It can trigger policy changes, interventions, and education programs to cultivate a more equitable housing market. Additionally, our findings underscore the urgency to confront intersectional discrimination in legal and policy frameworks, ensuring more comprehensive protection for marginalized communities.

Our research enhances the existing literature on rental housing market discrimination (Auspurg, Schneck, and Hinz Citation2019; Flage Citation2018), highlighting the intersectional discrimination that Arab Muslim individuals encounter in the housing sector. However, intersectional discrimination and housing inequality are not confined to Sweden. Future research in diverse global contexts can broaden our understanding of the barriers Arab Muslim individuals and other minorities face, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of discrimination in rental housing markets. While quantifying discrimination remains crucial, focusing solely on its existence limits our understanding of the complex variables involved. Deeper explorations into the nuanced interplay of intersecting identities can reveal the processes driving discrimination. Beyond merely documenting discrimination, examining intersectionality can help frame more effective interventions and policies, informing stakeholders about the unique challenges encountered by Arab Muslim individuals and enabling the development of comprehensive solutions. Therefore, future studies should adopt a multidimensional approach, using intersectionality theory to investigate the multi-layered discrimination faced by Arab Muslim individuals and other minorities.

It is important to acknowledge the nuanced distinction between religion and religiosity within the context of our study. The decision to use fictitious applicants identified as priests and imams was intended to isolate the effects of religious identity in the Swedish housing market. However, this design choice inadvertently foregrounds the dimension of religiosity – raising an important question about whether the degree of religious commitment, as signified by these vocational roles, might influence discrimination differently across religious groups. Indeed, the European discourse surrounding assimilation highlights varying experiences for individuals who are nominally affiliated with Islam but do not actively practice the religion or visibly adhere to its precepts, as compared to those who are perceived as more devout or religiously engaged. This distinction brings to light the possibility that the observed discrimination against the Arab Muslim applicant might not solely pivot on religious identity but could also be influenced by perceived levels of religiosity. While our experimental design does not allow us to measure the impact of varying levels of religiosity directly, it underscores the importance of considering religiosity as a potential variable in future research.

On a related note, our study employs names and occupations as proxies for ethnicity and religion. This methodological choice merits further consideration, especially regarding the occupations of priest and imam. These occupations, while effectively signaling religious affiliation, represent specific roles within their respective religious communities and might not encapsulate the breadth of experiences and stereotypes these groups face. This specificity could lead to unique stereotypes or prejudices that do not uniformly apply across the broader religious community. It is critical to acknowledge that such roles may evoke distinct forms of statistical and taste-based discrimination, which have been foundational in understanding patterns of discrimination in various contexts. Statistical discrimination, based on assumptions about group behaviors, and taste-based discrimination, stemming from personal prejudices, likely interact in complex ways to shape the discrimination observed in our study. Therefore, using religious leaders as markers introduces a layer of complexity in interpreting our findings, potentially influencing the generalizability of our results to the broader Arab Muslim and Christian populations. Future research should explore a broader range of occupational and identity markers to more fully understand the dynamics of discrimination in the housing market and beyond, ensuring a comprehensive examination of the varied forms of discrimination that members of these communities may face.

Furthermore, while our study delineates the differential responses based on ethnicity and religion, it also highlights the inherent limitations of not fully capturing the interactive effects of these identities, as posited by intersectionality theory. Specifically, excluding certain experimental conditions, such as a Swedish imam, restricts our ability to dissect the multifaceted nature of intersectional discrimination to its fullest extent. Acknowledging this, we advocate for future research endeavors to adopt a complete factorial design that orthogonally crosses ethnic and religious markers. Such an approach would address the gaps identified in our study and enrich our understanding of how intertwined identity facets impact individuals’ opportunities in the housing market.

In conclusion, this study provides a nuanced understanding of the intersectional discrimination faced by Arab Muslims in the Swedish rental housing market, highlighting the compounded effects of ethnic and religious identities on their housing opportunities. Our findings indicate a significant disparity in landlord responses to Arab Muslims compared to their Swedish Christian and Arab Christian counterparts, illustrating the complex interplay of prejudice and discrimination at the intersection of ethnicity and religion. By employing a rigorous field experiment design, we have quantitatively demonstrated how each additional marginalized identity independently contributes to and amplifies the overall experience of discrimination. This research contributes to the broader discourse on discrimination by confirming the critical role of intersectionality in understanding and addressing inequalities in housing and beyond. The insights gained from this study enrich our theoretical understanding of discrimination and serve as a vital resource for developing more inclusive and effective housing policies.

Authors’ contribution

Ali Ahmed conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, and made revisions. Umba Nsabimana handled the preparation of materials, execution of the experiment, and data collection. Both authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study in accordance with §§3-4 of the Ethical Review Act (Lag om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor) in Sweden (Swedish Code of Statutes Citation2003:460) since no personally identifiable information of any human being was collected in the field experiment.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

While preparing this article, the authors used ChatGPT powered by GPT-4 to enhance grammar, clarity, and prose. After using this technology, the authors reviewed and revised the content as necessary. The authors assume full responsibility for the article’s content.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to an editor and two reviewers of the journal for their insightful comments and detailed suggestions, which were integral in refining earlier drafts of this paper. They would also like to thank the seminar participants at Linköping University, The Ratio Institute, and the CEPDISC’22 Conference on Discrimination for their valuable input.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data and Stata do-file that support the findings of this study are available at Zenodo ( https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10027620

).Additional information

Funding

References

- Adida, C. L., D. D. Laitin, and M. A. Valfort. 2010. “Identifying Barriers to Muslim Integration in France.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (52): 22384–22390. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1015550107.

- Agerström, J., and D. O. Rooth. 2009. “Implicit Prejudice and Ethnic Minorities: Arab-Muslims in Sweden.” International Journal of Manpower 30 (1/2): 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720910948384.

- Ahmadi, F., M. Darvishpour, N. Ahmadi, and I. Palm. 2020. “Diversity Barometer: Attitude Changes in Sweden.” Nordic Social Work Research 10 (1): 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2018.1527242.

- Ahmed, A. M. 2010. “Muslim Discrimination: Evidence from two Lost-Letter Experiments.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 40 (4): 888–898. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00602.x.

- Ahmed, A., L. Andersson, and M. Hammarstedt. 2010. “Can Discrimination in the Housing Market be Reduced by Increasing the Information About the Applicants?” Land Economics 86 (1): 79–90. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.86.1.79.

- Ahmed, A., and M. Hammarstedt. 2008. “Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market: A Field Experiment on the Internet.” Journal of Urban Economics 64 (2): 362–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2008.02.004.

- Allport, G. W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Arrow, K. J. 2015. “The Theory of Discrimination.” In Discrimination in Labor Markets, edited by O. A. Ashenfelter and A. Rees, 1–33. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400867066-003.

- Auspurg, K., A. Schneck, and T. Hinz. 2019. “Closed Doors Everywhere? A Meta-Analysis of Field Experiments on Ethnic Discrimination in Rental Housing Markets.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (1): 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1489223.

- Bartkoski, T., E. Lynch, C. Witt, and C. Rudolph. 2018. “A Meta-Analysis of Hiring Discrimination Against Muslims and Arabs.” Personnel Assessment and Decisions 4 (2): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.25035/pad.2018.02.001.

- Becker, G. S. 1957. The Economics of Discrimination. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Bertrand, M., and E. Duflo. 2017. “Field Experiments on Discrimination.” In Handbook of Field Experiments, Volume 1, edited by E. Duflo and A. Banerjee, 309–393. North-Holland. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.hefe.2016.08.004.

- Bevelander, P., and J. Otterbeck. 2013. “Islamophobia in Sweden: Politics, Representations, Attitudes and Experiences.” In Islamophobia in the West, edited by M. Helbling, 70–82. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203841730.

- Brown, M. D. 2019. “Conceptualising Racism and Islamophobia.” In Comparative Perspectives on Racism, edited by J. ter Wal, and M. Verkuyten, 73–90. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Carlsson, M., and S. Eriksson. 2014. “Discrimination in the Rental Market for Apartments.” Journal of Housing Economics 23:41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2013.11.004.

- Carpusor, A. G., and W. E. Loges. 2006. “Rental Discrimination and Ethnicity in Names1.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 36 (4): 934–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00050.x.

- Collins, P. H., and S. Bilge. 2020. Intersectionality. Cambridge: Polity.

- Crenshaw, K. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989 (1): 139–167.

- Crenshaw, K. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

- Davis, K., and H. Lutz, eds. 2023. The Routledge International Handbook of Intersectionality Studies. Routledge.

- Faul, F., E. Erdfelder, A. Buchner, and A. G. Lang. 2009. “Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses.” Behavior Research Methods 41 (4): 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149.

- Faul, F., E. Erdfelder, A. G. Lang, and A. Buchner. 2007. “G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences.” Behavior Research Methods 39 (2): 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

- Flage, A. 2018. “Ethnic and Gender Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis of Correspondence Tests, 2006–2017.” Journal of Housing Economics 41:251–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2018.07.003

- Ghekiere, A., B. Martiniello, and P. P. Verhaeghe. 2023. “Identifying Rental Discrimination on the Flemish Housing Market: An Intersectional Approach.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 46 (12): 2654–2676. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2177120.

- Horr, A., C. Hunkler, and C. Kroneberg. 2018. “Ethnic Discrimination in the German Housing Market: A Field Experiment on the Underlying Mechanisms.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 47 (2): 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2018-1009.

- Larsson, G. 2005. “The Impact of Global Conflicts on Local Contexts: Muslims in Sweden After 9/11 – the Rise of Islamophobia, or New Possibilities?” Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 16 (1): 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/0959641052000313228.

- Larsson, G., and S. Stjernholm. 2016. “Islamophobia in Sweden: Muslim Advocacy and Hate-Crime Statistics.” In Fear of Muslims? Boundaries of Religious Freedom: Regulating Religion in Diverse Societies, edited by D. Pratt and R. Woodlock, 153–166. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29698-2_10.

- Lauwers, A. S. 2019. “Is Islamophobia (Always) Racism?” Critical Philosophy of Race 7 (2): 306–332. https://doi.org/10.5325/critphilrace.7.2.0306.

- Lippens, L., S. Vermeiren, and S. Baert. 2023. “The State of Hiring Discrimination: A Meta-Analysis of (Almost) all Recent Correspondence Experiments.” European Economic Review 151:104315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2022.104315.

- Living History Forum. 2024. “Islam och muslimer i Sverige.” https://www.levandehistoria.se/for-skola/kompetensutveckling-for-dig-som-arbetar-med-utbildning/att-forebygga-och-motverka-islamofobi-i-skolan/stark-era-kunskaper/islam-och-muslimer-i-sverige.

- Love, E. 2017. Islamophobia and Racism in America. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Morey, P., A. Yaqin, and A. Forte, eds. 2021. Contesting Islamophobia: Anti-Muslim Prejudice in Media, Culture and Politics. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Morgan, G., and S. Poynting, eds. 2016. Global Islamophobia: Muslims and Moral Panic in the West. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Olseryd, J., L. Wallin, and A. Repo. 2021. Islamofobiska hatbrott. Stockholm: The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention.

- Phelps, E. S. 1972. The Statistical Theory of Racism and Sexism.” American Economic Review 62 (4): 659–661. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1806107.

- Quillian, L., J. J. Lee, and B. Honoré. 2020. “Racial Discrimination in the U.S. Housing and Mortgage Lending Markets: A Quantitative Review of Trends, 1976–2016.” Race and Social Problems 12 (1): 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-019-09276-x.

- Rana, J. 2007. “The Story of Islamophobia.” Souls 9 (2): 148–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999940701382607.

- Riach, P. A., and J. Rich. 2002. “Field Experiments of Discrimination in the Market Place.” The Economic Journal 112 (483): F480–F518. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00080.

- Sander, Å. 2006. “Experiences of Swedish Muslims After the Terror Attacks in the USA on 11 September 2001.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 32 (5): 809–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830600704214.

- Statistics Sweden. 2024a. “Befolkningsstatistik.” https://www.scb.se/be0101.

- Statistics Sweden. 2024b. “Utrikes födda i Sverige.” https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/utrikes-fodda-i-sverige/.

- Steiner, K. 2015. “Images of Muslims and Islam in Swedish Christian and Secular News Discourse.” Media, War & Conflict 8 (1): 20–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635214531107.

- Swedish Code of Statutes. 2003:460. “Ethical Review Act (Lag om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor).” https://lagen.nu/2003:460.

- Swedish Institute. 2024. “Religion in Sweden.” https://sweden.se/life/society/religion-in-sweden.

- Turpin-Petrosino, C., ed. 2022. Islamophobia and Acts of Violence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Wolgast, S., F. Björklund, and M. Bäckström. 2018. “Applicant Ethnicity Affects Which Questions are Asked in a job Interview.” Journal of Personnel Psychology 17 (2): 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000197.

- Wolifson, P., S. Maalsen, and D. Rogers. 2023. “Intersectionalizing Housing Discrimination Under Rentier Capitalism in an Asset-Based Society.” Housing, Theory and Society 40 (3): 335–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2022.2163283.

- Yinger, J. 1986. “Measuring Racial Discrimination with Fair Housing Audits: Caught in the act.” American Economic Review 881–893. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1816458

Appendix

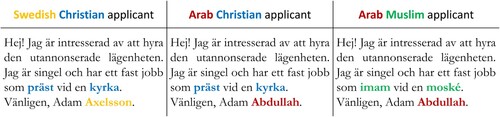

In this appendix, we report additional information and analysis for our article. First, presents the original formulations of the Swedish inquiries sent to landlords under each experimental condition. Second, provides definitions of all variables in our data. Third, offers a summary of statistics. Fourth, conducts a randomization check, demonstrating that our experiment was overall successfully randomized. Fifth, – contain correlation matrices. illustrates that the two measures of apartment size – number of rooms and square meters – were highly correlated. Consequently, we used square meters in all our analyses to denote apartment size.

Sixth, we explored whether utilizing probit models instead of the linear probability models reported in of the article would alter our estimations. – indicate that our results and conclusions remain robust under this alternative estimation method. Seventh, – investigate potential interaction effects between our experimental manipulation and various apartment and landlord characteristics. These analyses yielded no distinctive or significant findings.

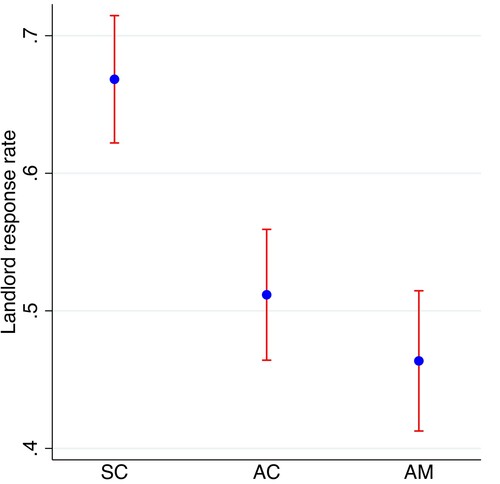

Eighth, this material documents an analysis of landlord responses (regardless of whether they were positive or negative) as an outcome variable in and . This analysis revealed, once again, an overwhelming advantage for the Swedish Christian applicant. No difference in the probability of receiving a landlord response was found between the Arab Christian and Arab Muslim applicants.

Lastly, presents Model 4 (the complete model) for all three outcome variables, documenting the estimated effects for the numerous apartment and landlord controls not shown in , , and .

Figure A1. Original letter of interest (application) in Swedish.

Note: Ethnicity was signaled through Swedish-sounding (yellow) and Arabic-sounding (red) surnames, and religious affiliation was signaled through occupation – a priest at a church (blue) and an imam at a mosque (green).

Table A1. Description of variables in the data.

Table A2. Summary of statistics, all variables in the data.

Table A3. Randomization check, mean comparisons of variables across experimental conditions.

Table A4. Correlation matrix, dependent variables.

Table A5. Correlation matrix, apartment characteristics.

Table A6. Probability of receiving a positive landlord response, estimated using probit models.

Table A7. Probability of receiving an apartment viewing invitation, estimated using probit models.

Table A8. Positive landlord response: interactions between explanatory variables and apartment and landlord characteristics.

Table A9. Apartment viewing invitation: interactions between explanatory variables and apartment and landlord characteristics.

Figure A2. Mean landlord response rate by applicant type.

Note: SC = Swedish Christian, AC = Arab Christian, and AM = Arab Muslim. Vertical red lines are 95 percent confidence intervals. NSC = 401, NAC = 428, and NAM = 371. Blue dots represent the probability of receiving a response from a landlord (regardless of whether it was positive or negative).

Table A10. Probability of receiving a landlord response.

Table A11. Apartment and landlord effects on outcomes in the complete model (Model 4)