?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In recent years, overseas labour migration has become a lifeline for many households in Nepal. Using survey data from 465 randomly selected households and 227 overseas labour migrants, this paper examines the factors influencing overseas labour migration and migration intensity in farming households by employing a generalised two-part fractional regression model, and migrants’ destination choice by using the probit model. We find that a higher proportion of educated members in the household, along with household’s credit access, indebtedness, and contacts with manpower agencies significantly increase the likelihood of overseas labour migration and migration intensity in the households, whereas the presence of employed members in the household, larger farms, irrigation access, and higher asset index significantly lower such likelihood. We find a lower likelihood of migration to Malaysia and the Middle East countries among individuals with employed household members and a higher asset index, while those connected to manpower agencies are more likely to choose these countries as destinations. Our findings emphasise the significance of creating and providing decent economic opportunities, including strengthening the agriculture sector, to address the existing surge in overseas labour migration from farming households in Nepal.

1. Introduction

International labour migration, often viewed as a path to a better future for migrants and their families (Limbu Citation2022), is an important livelihood means for individuals in lower-and middle-income countries (LMIC) (Mak, Zimmerman, and Roberts Citation2021). Out of the 281 million international migrants in 2020 (i.e. approximately 3.6% of the global population), about one-third (90 million) were from LMIC (UNDESA Citation2020) and 60% (169 million) were labour migrants (IOM Citation2024). International labour migration is rapidly becoming a predominant livelihood strategy for numerous households in Nepal (MOLESS Citation2022), an agrarian country in South Asia, which rose to LMIC status from a ‘low-income’ status in July 2020 (Bhattarai and Subedi Citation2021).

While the earliest migration to and from Nepal is believed to have occurred around 500 BC via informal trans-Himalayan trade with India, Tibet, and China, the formal international labour migration from Nepal is associated with the recruitment of Nepali men into the British army after the Anglo Nepalese War (1814–1816) (Sijapati and Limbu Citation2012). The international labour migration from Nepal primarily comprises seasonal (and informal) movement to India and regulated (or formal) migration to countries beyond India (aka overseas labour migration). In recent decades, overseas labour migration has witnessed an unprecedented surge, especially to countries such as Malaysia and those in the Gulf Cooperation Council (i.e. Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) (Adhikari et al. Citation2023; IOM Citation2019; MOLESS Citation2020; Sijapati and Limbu Citation2012). More recently, the United Kingdom (UK), Europe – Poland, Albania, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Germany, Romania, Cyprus and Malta; West Asia – Cyprus, Jordan, and Turkey; and other countries such as the Maldives, China, Japan have also emerged as prominent destinations for Nepali migrant workers (MOLESS Citation2022; Neubauer Citation2024).

Labour migration from Nepal is driven by several push (e.g. poverty, lack of domestic employment opportunities, conflict, and social, environmental, and political issues) and pull (e.g. higher demand and wages for skilled and low-skilled migrant workers in destination countries) factors (MOLESS Citation2022). It has been further spurred by the development of various foreign employment-related legal, policy, and institutional frameworks, as well as the globalisation and liberalisation of economic policies after the 1990s (MOLESS Citation2022; Shivakoti Citation2022; Sijapati and Limbu Citation2012). Available data indicate that since 2000/01, over six million labour permits have been issued to Nepali migrants, with over 85% of them destined to Malaysia and the Gulf countries (DOFE Citation2022; MOLESS Citation2020, Citation2022). This large-scale migration has resulted in a significant inflow of remittances to Nepal (with a projection to reach USD 11 billion in 2023), accounting for 27% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), positioning Nepal as the top country in South Asia and fifth globally in terms of remittance’s share to GDP (Ratha et al. Citation2023). Additionally, it has induced restructuring in household, village, and national economies, including changes in land use, agrarian relations, and livelihood outcomes (Adhikari Citation2021). Overseas labour migration has resulted in consequences beyond economic gains; therefore, understanding the factors driving this phenomenon in farming households is of significant importance to domestic policy to regulate migration and address multiple issues associated with it.

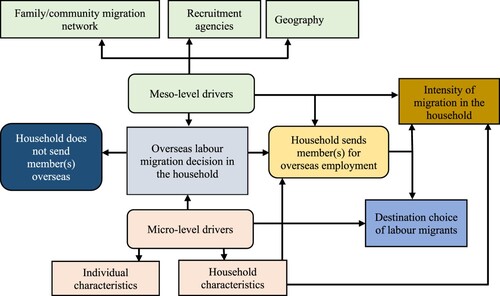

From a theoretical perspective, various theories with diverse perspectives and features or levels of analysis have emerged in the literature to explain migration (de Haas Citation2021; Massey et al. Citation1993). Among these, the New Economics of Labour Migration (NELM) views migration as a household decision and a strategy adopted by households to diversify their income sources (Massey et al. Citation1993; Taylor Citation1999). In general, Nepalese households have strong family ties and notable influence in migration decisions (Maharjan, Bauer, and Knerr Citation2013; Monteiro Citation2022), while substantial remittances are sent back by Nepali migrants to support household welfare (Mishra, Kondratjeva, and Shively Citation2022; MOLESS Citation2022), which highlights the significance of examining migration decisions from a household standpoint. Therefore, we analyse migration decisions primarily from the NELM or household perspective, while also considering migrants’ individual characteristics to examine their destination choice decisions. Specifically, this study examines the household-level drivers that influence households to (a) participate in overseas labour migration, (b) decide the number of member(s) to send overseas – migration intensity, and (c) household and individual factors that influence migrants’ destination choices (). Additionally, recent advances in migration literature, particularly the ‘aspiration-ability framework’ (Carling and Schewel Citation2018) and the ‘aspirations-capability framework’ (de Haas Citation2021), view migration as a function of aspirations and capabilities to migrate within context-specific obstacles and opportunities. We also discuss our findings in light of these perspectives on migration.

We examine overseas labour migration decision in the households using several household-level variables with evident effects on migration decision in previous studies, such as households’ human capital characteristics (household head’s age, education of household members, farming experience) (Adams Citation1993; Kafle, Benfica, and Winters Citation2020; Rozelle, Taylor, and de Brauw Citation1999), physical capital characteristics (farm size, tropical livestock unit (TLU), asset or wealth index, access to credit, indebtedness) (Bezu and Holden Citation2014; Bhandari Citation2004; Bylander and Hamilton Citation2015; Kafle, Benfica, and Winters Citation2020; Regmi, Paudel, and Bhattarai Citation2019), demographic characteristics (ethnicity, household size, dependency ratio) (Bhandari Citation2004; Gurung Citation2012; Kafle, Benfica, and Winters Citation2020; Lokshin, Bontch-Osmolovski, and Glinskaya Citation2010; Williams et al. Citation2020a), geographical characteristics (Bhandari Citation2004; Gurung Citation2012; Lokshin, Bontch-Osmolovski, and Glinskaya Citation2010), and migration networks or institutions or intermediaries (Regmi, Paudel, and Bhattarai Citation2019; Mora and Taylor Citation2006; Regmi, Paudel, and Bhattarai Citation2019; Shivakoti Citation2022; Williams et al. Citation2020b; Winters, De Janvry, and Sadoulet Citation2001). Given the evident effect of these household-level variables on the migration intensity decision of the households (Pradhan and Narayanan Citation2019), we use them to examine migration intensity within migrant households. Additionally, following previous studies (Davis, Stecklov, and Winters Citation2002; Mora and Taylor Citation2006; Regmi, Paudel, and Bhattarai Citation2019; Williams et al. Citation2020a), we use both migrants’ individual and household characteristics for examining their destination choice.

Despite the growing number of studies on migration determinants in Nepal, previous studies (Bhandari Citation2004; Bohra-Mishra and Massey Citation2011; Lokshin, Bontch-Osmolovski, and Glinskaya Citation2010; Regmi, Paudel, and Bhattarai Citation2019; Williams et al. Citation2020a) have not adequately taken into account the existing diverse agro-ecological and rural-urban settings, and other important socio-economic variables, such as household’s access to credit, irrigation and migration networks, including employment and non-farm business involvement status of household members that can significantly influence household migration decisions. Once households decide to participate in overseas labour migration, factors influencing their decision on the number of member(s) to send overseas relative to economically active members in the household (i.e. migration intensity) is largely unexplored in the literature. Limited evidence also exists on the factors that influence migrants’ destination choice in Nepal, but understanding this aspect is becoming increasingly important given the evolving labour market destinations and their diverse requirements and returns for labour migrants.

Besides focusing on the determinants and intensity of overseas labour migration, and destination choice of Nepali labour migrants in a single study, we complement the literature in multiple ways. First, we specifically consider overseas labour migrants and their households in this study and expand upon previous studies by incorporating additional socio-economic variables, such as household’s indebtedness, access to credit and irrigation, and employment and non-farm business involvement status in our analysis, and examining their effect on labour migration decisions. Second, we take into account the effect of the migration network using different measures, such as the number of relatives abroad, number of neighbours abroad, and number of manpower agencies with whom households had connections prior to the emigration of household member(s). Third, as caste is a crucial factor in explaining the access to several resources and power dynamics in Nepalese society (Rahut et al. Citation2022), we consider caste or ethnicity of households as one of the important variables and examine its effects categorising it into three groups: Brahmin-Chhetri, Janajati, and Dalit inline of historical caste hierarchy and social structure in Nepal (Gurung Citation2019). Fourth, we also include agro-ecological (hill vs terai) and urban-rural variations in our study to examine the effect of geography on migration decisions. Finally, we apply a novel and robust empirical technique, i.e. generalised two-part fractional regression model to examine determinants of overseas labour migration and migration intensity mainly from the household perspective, and probit model to examine determinants of migrants’ destination choice from both individual and household perspectives. The findings of this study hold important policy implications for addressing overseas labour migration and associated issues in Nepal.

The paper is organised into four sections, including this one. The following section presents the research methods, with a description of the study area, sampling design and data collection, including the empirical framework for examining overseas labour migration and migration intensity decisions, and destination choice of overseas labour migrants. Section 3 discusses the results and finally, we conclude with policy implications of the study and avenues for future work in Section 4.

2. Methodology

2.1. Description of the study area and sampling design

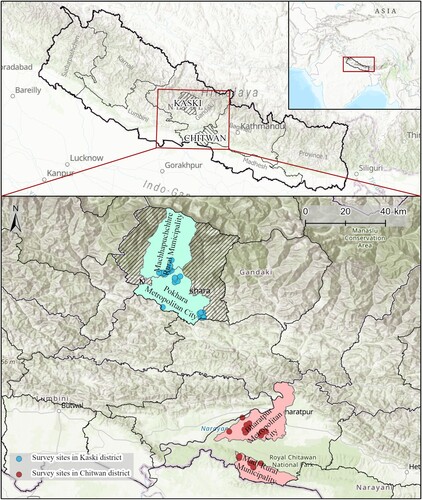

This study was conducted in Chitwan, representing the Terai region, and in Kaski district, representing the Hill region, within the Bagmati and Gandaki Provinces of Nepal, respectively. Given Nepal’s rapid transition from an agricultural country to a remittance-based economy, a study on migration becomes more relevant if it is conducted in regions with notable agricultural production and migration rates. Hence, we purposively selected these districts because both Chitwan and Kaski are renowned for agricultural productivity and have higher cereal crops, vegetables, and livestock production compared to other districts in Bagmati and Gandaki Province, respectively (MOALD Citation2022). In terms of labour migration, during the past decade (from 2012/13 to 2021/22), Chitwan recorded the highest number of overseas labour migrants (totalling 94,497 with 76,091 males and 18,406 females) in Bagmati Province, while Kaski ranked fifth in Gandaki Province with a total 72,926 overseas migrant workers (59,381 males and 13,545 females) (MOLE Citation2018; MOLESS Citation2020, Citation2022).

In Nepal, administratively, districts are divided into urban municipalities (metropolitan city/sub-metropolitan city/municipality) and rural municipalities and then into wards (smallest administrative unit), and further into toles (i.e. distinct clusters of households, typically located at crossroads and surrounded by agricultural fields). We considered rural and urban settings, including agricultural production and migration flows in the selected districts to select sample households. Additionally, inputs from the local stakeholders (i.e. metropolitan/municipality/ward representatives, Agricultural Knowledge Centre/Research Station representatives, and local communities/entrepreneurs) were considered to select one metropolitan and one rural municipality from each district, and two wards from each metropolitan and rural municipality. Thus, we selected ward no. 13 and 20 in Bharatpur Metropolitan City and ward no. 1 and 6 in Madi Rural Municipality in Chitwan district, and ward no. 16 and 32 in Pokhara Metropolitan City and ward no. 2 and 4 in Machhapuchchhre Rural Municipality in Kaski district (). Following that, we identified four to nine toles with high migration rates from each chosen ward and prepared a list of entire households in each tole. Next, we categorised the households into two strata: overseas labour migrant households and non-migrant households. Next, we selected sample households from each stratum using a stratified random sampling technique. Thus, we collected primary data from 465 households (266 non-migrant households and 199 overseas labour migrant households), comprising 230 households in Chitwan district (148 non-migrant households and 82 overseas labour migrant households) and 235 households in Kaski district (118 non-migrant households and 117 overseas labour migrant households) for this study.

In this study, we define overseas labour migrant households as households with at least one member living overseas for employment for at least six months prior to the survey, and non-migrant households as households having no history of overseas labour migration. A cut-off of at least six months of overseas stay was considered to avoid the inclusion of short-term or transient migrant households in the sample. Being away for six months has been used as the cut-off point for the selection of migrants/migrant households in other studies too (Batista, Seither, and Vicente Citation2019; Fan Citation2021). For brevity, we use ‘migrant household/s’ to refer to ‘overseas labour migrant household/s’ and ‘migrant/s’ to refer to ‘overseas labour migrant/s’ from this point onward.

2.2. Questionnaire design, pre-testing, and survey

We developed a questionnaire that included a common set of questions for both migrant and non-migrant households, supplemented with specific questions for migrants in migrant households. The common questions were related to the household’s demographic and socio-economic status, including household’s migration and migration network status; whereas additional questions were aimed to collect information on the individual characteristics of migrants and their migration histories, overseas employment status, earnings, and remittance transfers. After pre-testing, the final survey was conducted from October 2019 to January 2020, and household heads were interviewed. In their absence, the spouse of a migrant or another adult member of the household was interviewed (219 households).

The questionnaire was also designed to collect and use retrospective information on the employment and non-farm business status of household members, household’s livestock and other asset ownership, indebtedness, family/community migration networks, and connection with migration intermediaries for both labour migrant and non-migrant households. The use of these retrospective data is expected to adequately capture the pre-migration status of households and avoid reverse causality bias. Since Nepal’s Department of Foreign Employment (DOFE) issues labour permits for two years for major labour destinations, we considered 2015 (three years before the survey) as the reference year for collecting retrospective data. Based on retrospective information on 9 durable goods (i.e. television, laptop-desktop, mobiles-telephone, motorbike, sewing machine, refrigerator, LPG gas, rice cooker, clothes iron) collected in numeric form and 8 housing quality characteristics (i.e. a number of rooms, house with a cemented roof, house with cemented floor, house with indoor toilet, access to electricity, access to cable-television, access to internet, house with indoor water supply), all collected in dichotomous form except for the number of rooms, we also constructed an asset index using principal component analysis to use in the empirical analysis. Additionally, we generated variables such as the proportion of household members with higher education by taking the ratio of the number of adults with more than 10 years of schooling to household size and dependency ratio by taking the ratio of the number of persons aged under 15 years and those aged over 64 years to the number of persons aged 15–64 years for empirical analysis. We converted the total livestock holding of the household into Tropical Livestock Unit (TLU) following Otte and Chilonda (Citation2002).

2.3. Empirical framework for examining households overseas labour migration and migration intensity decisions

Household-level migration decisions involve a two-step linked process. Given the costs as well as opportunities and challenges associated with the migration of family member(s), the household at first must decide whether to participate in overseas labour migration. Once this decision is made, participating households must decide the number of household members to send overseas for employment. Our sample size consisted of 465 households (266 non-migrant households and 199 migrant households). Among the migrant households, 87%, 12% and 1% had one, two, and three members overseas for employment, respectively. We computed migration intensity as the ratio of the number of migrants to the number of economically active members in the household. As a result, migration intensity is a fractional variable observed only for a non-randomly selected sub-population, and the exclusion of non-migrant households while estimating migration intensity may induce selectivity bias.

Heckman (Citation1979) introduced a sample selection model to address sample selection bias, but it assumes a linear relationship between the explanatory variables and the dependent variable. Consequently, it may produce predictions outside the meaningful [0, 1] interval (Faria, Rebelo, and Gouveia Citation2020). To overcome this problem, Papke and Wooldridge (Citation1996) introduced fractional response models which ensure predictions within the unit interval by estimating the conditional mean only (Schwiebert Citation2018). However, the (non-linear) estimation of the conditional mean, through fractional logit or fractional probit models, applies well only when few observations are in the boundary levels (Faria, Rebelo, and Gouveia Citation2020). In many cases, a fractional dependent variable may contain many values at one or both boundaries and the values at the zero boundary may be governed by a different process than the values between the boundaries (Wulff Citation2019). For instance, in this study, covariates that affect a household’s decision to participate in overseas labour migration may differ from those affecting the migration intensity in that household. To address this, Ramalho and da Silva (Citation2009) proposed a two-part fractional model (TP-FRM) which allows for the specification of a binary model for the participation decision, for instance, no migration versus overseas labour migration, and a fractional regression model for the magnitude decision, such as intensity of migration in the household. The TP-FRM model allows for different effects of covariates on each decision (Wulff Citation2019). Since TP-FRM assumes independence of these processes (Schwiebert and Wagner Citation2015), if unobserved factors affecting the participation decision are correlated with factors affecting migration intensity, the estimates from two-part model will be biased (Wooldridge Citation2010). To address this issue, Schwiebert and Wagner (Citation2015) proposed the generalised two-part fractional regression model (GTP-FRM) which allows for the dependence of these processes and also nests the two-part model as a special case (Wulff Citation2019).

Following Schwiebert and Wagner (Citation2015) and (Wulff Citation2019), we use the conditional mixed-process framework and the cmp command developed by Roodman (Citation2011) to fit and apply the GTP-FRM in STATA 17 to examine the factors influencing overseas labour migration and migration intensity among households. The econometric approach we followed is presented below. The first part of our econometric approach consists of determining whether an observation or household i, (i = 1, … … .., n) has a zero outcome (no migration) or not (overseas labour migration), that is, specifying what determines households participation in overseas labour migration.

(1)

(1) where

is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the observation has a non-zero outcome (or migrant household) and 0 otherwise (or non-migrant household);

is a vector of explanatory variables affecting households’ migration decision,

is a vector of unknown parameters and

is the error term. To model the participation decision in (1), we use a probit model,

(2)

(2) where

is the standard normal cumulative distribution function. The second process determines the decision on magnitude or actual outcome (i.e. intensity of migration), conditional on having a non-zero outcome, where we assume a fractional dependent variable (migration intensity), y, with values in the unit interval. We specify the conditional mean of the migration intensity decision as follows:

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4) where

is a vector of explanatory variables affecting the magnitude (or migration intensity),

is a coefficient vector concerning

, and

denotes the bivariate standard normal distribution with

representing the correlation between the participation and magnitude decisions. EquationEquation (4)

(4)

(4) is the fractional probit specification, used to model non-zero values of y. Unlike TP-FRM which assumes that

does not depend on the first process (i.e. on

and its determinants, leading to biased estimates if the second process depends on the first process), the GTP-FRM accounts for dependency through

in the model. It allows both x and z affect the magnitude decision – x affecting the decision directly and z indirectly through s (Schwiebert and Wagner Citation2015). If the two processes are independent (ρ = 0), then the GTP-FRM reduces to the simpler TP-FRM, otherwise (ρ > 0) TP-FRM would be mis-specified (Schwiebert and Wagner Citation2015; Wulff Citation2019).

Additionally, the GTP-FRM needs an exclusion restriction to be identified (Schwiebert and Wagner Citation2015; Wulff Citation2019); that is existence of a variable affecting the households’ decision to participate in migration without directly affecting the migration intensity decision. As elders or household heads in Nepal mainly make key household decisions, we expect the age of the household head to influence migration participation decisions. However, we do not expect it to have an effect on migration intensity, as that is mainly determined by the presence of younger or adult members in the household and the household’s financial capability to support migration, among other things. In addition, previous studies (Davis, Stecklov, and Winters Citation2002; Kafle, Benfica, and Winters Citation2020) have also shown a significant positive effect of household head’s age on migration decisions. Therefore, we consider the household head’s age as an exclusion restriction which exists in z but does not appear in x in the model. Furthermore, as migration intensity already incorporates information about household size, we exclude the household size variable from x. As the explanatory variables characterising the first process are also assumed to influence the second process, our set of variables for the second process includes the same variables as the first process, except for the age of the household head and household size.

In GTP-FRM, the model coefficients should not be interpreted directly, rather we should rely on marginal effects (Wulff Citation2019). As shown by Schwiebert and Wagner (Citation2015), the predicted values of the FRM given values of the covariates are given by

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

We can compute the expected value of conditional on

>0, i.e. the term

. The marginal effect is given by:

(7)

(7)

2.4. An empirical framework for examining destination choice of overseas labour migrants

In our dataset, 227 labour migrants from 199 migrant households migrated to 21 different countries, with 72.2% mainly to the Middle East countries such as Qatar (22%), Saudi Arabia (20.2%), United Arab Emirates (20.7%), Kuwait (3.5%), Bahrain (3.5%), Oman (2.2%) and Iraq (0.4%). Similarly, Malaysia, one of the East Asian countries, was another major destination for 7% of labour migrants in our sample. Due to Malaysia and the Gulf countries being the most popular destinations for Nepali labour migrants, we categorised them, along with Iraq, as ‘Malaysia and the Middle East’ (MME) countries, which comprised 181 migrants (79.8%), while the rest of the countries were grouped as ‘other destinations’, which accounted for 46 migrants (20.3%). The countries included in ‘other destinations’ and the percentage of migrants from the study sample migrating to these destinations include Singapore (0.4%); Japan (6.6%), the Republic of Korea (4%), Macao (1%), Hong Kong (0.4%); China (0.4); Portugal (2.2%), Malta (1.8%), Poland (0.4%), The United Kingdom (UK) (0.4%); Romania (0.4%); Canada (0.9%), and the Maldives (1.3%).

To examine the factors influencing the destination choice of labour migrants, we use a probit model, in which, the probability (Pr) of a labour migrant choosing a destination country can be explained by:

(8)

(8)

where dependent variable equals 1 if a migrant i from household j has migrated to MME countries, 0 otherwise (or 0 if a migrant i from household j has migrated to other destinations),

is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution,

represents the vectors of parameters to be estimated, and

represents explanatory variables – both individual and household characteristics of migrants.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Descriptive statistics

presents the description and summary statistics of the characteristics of migrant households compared with non-migrant households used to examine overseas labour migration and migration intensity in the households. In comparison to migrant households, non-migrant households had an older household head with more farming experience, including a significantly higher proportion of more educated household members, greater involvement in domestic employment and non-farm businesses, larger farm sizes, and a higher asset index. Additionally, non-migrant households comprised a significantly higher proportion of households from the Brahmin-Chhetri community. In contrast, migrant households had significantly larger family sizes, indebtedness, and larger migration networks such as more relatives and neighbours abroad and connections with recruitment agencies (RA) or manpower agencies. They also constituted a significant proportion of households from Janajati and Dalit ethnic and caste groups. While migrant households comprised of significant proportion of households from the hill areas, both migrant and non-migrant sample households were uniformly located across the rural and semi-urban areas of the study districts.

Table 1. Summary statistics of explanatory variables used for examining overseas labour migration and migration intensity.

depicts the characteristics of migrants and their households used to examine the destination choice of migrants. Overall, the mean of education of migrants was 10.06 years, with those migrating to other destinations having significantly higher education than those migrating to MME countries. Migrants to MME countries were mainly engaged in farming, while those going to other destinations were mostly engaged in studies before emigration. Migrants to other destinations had a significantly higher mean age for the household head, employed household members, larger household size, and higher asset index, while those going to MME countries had significantly higher involvement of household members in non-farm business activities and a higher dependency ratio. Additionally, MME countries were the major destination for a significant proportion of Dalit migrants than other destinations.

Table 2. Summary statistics of explanatory variables used for examining destination choice of overseas labour migrants.

3.2. Factors influencing overseas labour migration

shows the coefficient estimates and marginal effects for both parts of the model: the first part, which examines the probability of a household being an overseas labour migrant household, and the second part, which examines the factors influencing migration intensity within migrant households. The correlation between overseas labour migration and migration intensity decisions of the households is positive and significant at the 1% significance level (/atanrho = 0.367***, SE = 0.082), justifying the use of GTP-FRM to examine households’ overseas labour migration and migration intensity decisions.

Table 3. GTM-FRM results: factors influencing overseas labour migration and migration intensity.

We discuss the results based on the average marginal effect obtained from the probit model (). The results revealed a significant positive effect of several variables on overseas labour migration decisions. Specifically, the age of the household head had a significant positive effect on overseas labour migration, with a 1.1% increase in the likelihood of participation in overseas labour migration for each additional year of age of the household head. This is possibly due to older heads having more children at prime migration age (Adams Citation1993). Earlier studies, such as Winters, De Janvry, and Sadoulet (Citation2001) and Davis, Stecklov, and Winters (Citation2002), found a positive but diminishing effect of household head’s age on migration in rural Mexico; while Tegegne and Penker (Citation2016) found a significant positive effect on migration in Ethiopia. Similarly, Kafle, Benfica, and Winters (Citation2020) also found a significant positive effect of household head’s age on migration in Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Ethiopia and Uganda.

The presence of educated members in the household had a significant positive effect on overseas labour migration, with a 28% increase in the likelihood of participation for households with a higher proportion of educated members. More educated individuals are more likely to migrate overseas expecting greater opportunities and benefits (Schewel and Fransen Citation2018). Additionally, de Haas (Citation2021) argues that education, among other factors, not only enhances individuals’ skills, knowledge, and awareness but also shapes their perception of the good life, often fuelling their aspirations to migrate internally or internationally, partly irrespective of the ‘objective’ material conditions at home. Similarly, higher levels of education are often linked with enhancing the capability for migration or instilling the belief and self-confidence in finding employment, adapting to new environments or securing a visa (de Haas Citation2021), as well as establishing social networks that facilitate migration (Carling Citation2002). Given limited domestic employment prospects and awareness of potential opportunities overseas, more educated individuals in households with a higher proportion of educated members might have expectations of greater opportunities and benefits, as well as aspirations to lead the life they desire, making them more likely to migrate overseas. In line with our study findings, Schewel and Fransen (Citation2018) also revealed a greater aspiration to migrate among individuals with access to formal education in Ethiopia. Other studies, for instance, Yan, Bauer, and Huo (Citation2014) in rural China, Bezu and Holden (Citation2014) in Ethiopia, and Root and De Jong (Citation1991) in the Philippines also found positive effects of the education of household members on migration.

When examining the relationship between ethnicity and migration, compared to Brahmin and Chhetri communities, belonging to the ethnic Janajati group increased the likelihood of households’ participation in overseas migration by 10.4%. Janajatis are considered lower in the caste hierarchy and with less access to rights, public services, and opportunities than high-caste Brahmins and Chhetris (Bennet, Dahal, and Govindasamy Citation2008; Williams et al. Citation2020a). The lack of employment and deprivation of equal access to opportunities at home might have influenced Janajati households to seek employment overseas. Rajan, Keshri, and Deshingkar (Citation2023) and Roy et al. (Citation2021) also found a higher prevalence of temporary labour migration among the disadvantaged social groups in India. Additionally, the longstanding tradition of Hill Janajati youths joining the British Army for employment (Adhikari Citation2021) could be another reason for the higher likelihood of overseas labour migration from this group. However, despite Dalits being the most disadvantaged ethno-caste group (Williams et al. Citation2020a); we did not find a statistically significant association between Dalit community and overseas labour migration. Nearly 42% of the Dalit population is living below the national poverty line compared to 25.2% of the total population (International Dalit Solidarity Network Citation2018). While international labour migration is a powerful poverty reduction tool, high migration costs are more likely to prevent the poor from migrating (Hagen-Zanker, Postel, and Vidal Citation2017). Extreme poverty and marginalisation might have constrained the ability of Dalit individuals to bear such migration costs and participate in overseas labour migration.

Likewise, household size had a statistically significant and positive effect on overseas migration. For each additional member in the households, the likelihood of households’ participation in overseas labour migration was increased by 5.4%. Households with larger family sizes have the opportunity to leverage surplus labour to improve household welfare. Given limited domestic employment opportunities and various challenges in agriculture (Thapa Magar et al. Citation2021), farming households with larger families might have used overseas labour migration as a strategy to optimise surplus labour, diversify income streams and mitigate risks associated with agricultural production and income. This finding aligns with the NELM theory and previous studies conducted in Nepal (Bhandari Citation2004; Lokshin, Bontch-Osmolovski, and Glinskaya Citation2010), Sub-Saharan Africa (Kafle, Benfica, and Winters Citation2020), Mexico (Winters, De Janvry, and Sadoulet Citation2001), and China (Xiong et al. Citation2020; Yan, Bauer, and Huo Citation2014) which showed a positive relationship between household size and migration.

Contrary to the NELM theory, which views migration as a substitute for inaccessible credit markets (Massey et al. Citation1993; Wouterse and Taylor Citation2008), we found significant positive relationships between household credit access, household indebtedness, and overseas migration. Households’ access to credit and indebtedness increased the likelihhod of overseas migration in households by 15.4% and 9.1%, respectively. With the expansion of banks and other financial service providers (e.g. saving and credit cooperatives), household’s access to financial services has improved in recent years in Nepal (NRB Citation2021; Shakya et al. Citation2016). Such improved access to credit might have enabled households to finance their members’ migration using loans and settle their debts using remittances. Studies conducted by Bylander and Hamilton (Citation2015) in Cambodia, Kafle, Benfica, and Winters (Citation2020) in Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Ethiopia, and Shonchoy (Citation2015) in Bangladesh also revealed a complementary effect of household access to credit on migration. Similarly, past studies from Nepal (Sherpa Citation2010; Sijapati et al. Citation2017) revealed the high use of credit by migrant households to finance migration.

Family and community migration networks, along with migration intermediaries by providing essential information and assistance play a crucial role for overseas employment (Massey et al. Citation1993; Mora and Taylor Citation2006; Sha and Khor Citation2024; Shivakoti Citation2022). Additionally, migrant networks and feedback mechanisms often increase aspirations and capabilities to migrate, particularly among relatively poor, low-skilled migrant groups, by reducing the economic, social, and psychological costs associated with migration (de Haas Citation2010). We also found a significant positive effect of households’ contacts with relatives abroad, neighbours abroad, and recruitment or manpower agencies on overseas labour migration, with households’ larger connections with manpower agencies increasing the likelihood of overseas migration by 23.8%, while having more relatives abroad and neighbours abroad increased such likelihood by 2.2% and 1.2%, respectively. Previous studies have found a significant positive effect of family and community migration networks on Mexico-US migration (Davis and Winters Citation2001; Mora and Taylor Citation2006; Winters, De Janvry, and Sadoulet Citation2001) and migration from Nepal (Williams et al. Citation2020b). Other studies found a significant positive effect of migration intermediaries in facilitating migration from Nepal (Sha and Khor Citation2024; Shivakoti Citation2022) and South Asia (Srivastava and Pandey Citation2017).

Additionally, households located in the hills or semi-urban areas also exhibited a higher likelihood of overseas labour migration. For households located in hill areas, the likelihood of migration increased by 19.4%, while in semi-urban areas, it increased by 8.9%. In Nepal, the Hill region is relatively less accessible, with limited economic opportunities and higher poverty than the Terai region (Goli et al. Citation2019). Declining rural livelihoods, along with growing disparities between rural and urban areas and among regions, may influence migration patterns (Srivastava and Pandey Citation2017). Thus, households in the hills might have opted for overseas labour migration anticipating better opportunities and quality of life for their members. Previous studies (Bhandari Citation2004; Jaquet, Kohler, and Schwilch Citation2019) also highlighted increased migration from households located in the hills or rural settings. On the other hand, households located near the market centres have greater access to information and services related to foreign employment, including access to migration intermediaries (Gurung Citation2012), and that might have played a role in increasing the likelihood of overseas labour migration among households located in semi-urban areas.

We also found a significant negative effect of several variables on the likelihood of overseas labour migration. Specifically, household members' engagement in domestic employment, larger farm size, access to irrigation, a higher asset index, and more farming-experienced household head decreased the likelihood of overseas labour migration by 28.4%, 7.3%, 7.3%, 7.1%, and 1.8%, respectively. Our findings further corroborate the notion that overseas labour migration from Nepal is driven mainly by a lack of domestic employment opportunities (MOLESS Citation2020), poverty or relative deprivation (Bhandari Citation2004; MOLESS Citation2022), and inadequate agricultural income (Maharjan, Bauer, and Knerr Citation2013). Access to irrigation can serve as an alternative to short-term migration as a risk mitigation strategy, enabling individuals to specialise in agricultural activities and achieve improved incomes (Zaveri, Wrenn, and Fisher-Vanden Citation2020). Previous studies in India revealed a significant negative effect of households’ access to irrigation on migration (Sedova and Kalkuhl Citation2020; Zaveri, Wrenn, and Fisher-Vanden Citation2020). Other studies revealed a lower likelihood of migration in households with the participation of their members in non-agricultural employment in Mexico (Fishman and Li Citation2022) and income-generating activities in Tajikistan (Ghimire, Harou, and Balasubramanya Citation2023). Additionally, Kafle, Benfica, and Winters (Citation2020) found relative deprivation of wealth increasing migration in Sub-Saharan Africa, while Bhandari (Citation2004) in Nepal and Ghimire, Harou, and Balasubramanya (Citation2023) in Tajikistan found a lower likelihood of outmigration in households with greater wealth or larger agricultural holdings or asset index.

3.3. Factors influencing migration intensity

We found statistically significant effects of several household characteristics on migration intensity (). Specifically, a higher proportion of educated household members, a higher dependency ratio, access to credit, indebtedness, larger connections with manpower agencies, and household’s location situated in the hills increased the likelihood of migration intensity by 6.0%, 11.4%, 5.1%, 3.3%, 3.5%, and 6.1%, respectively. Limited domestic employment opportunities, even for educated individuals, along with increased awareness and aspirations for better opportunities and quality of life, might have played a role in intensifying overseas labour migration in households with a higher proportion of more educated members. Similarly, the presence of a larger number of dependents in the household might have compelled adult members to undertake overseas labour migration to generate income and fulfil the needs of their dependent family members. Pradhan and Narayanan (Citation2019) also reported a significant positive effect of dependency ratio on migration intensity in India. On the other hand, indebtedness and access to credit might have prompted households to borrow money to finance the migration of suitable family members, thereby intensifying migration in these households. Similarly, as described earlier, the scarcity of economic prospects in the hills and households’ access to overseas labour migration-related information and services through the manpower agencies/agents might have been vital in intensifying overseas labour migration in households located in the hills as well as those with greater linkages to manpower agencies.

Despite the small magnitude (0.2%), we found a significant negative effect of the household head’s farming experience on migration intensity. Similarly, the presence of domestically employed household members, possession of larger farms, access to irrigation, and a higher asset index within the household also had a significant negative effect on migration intensity, and decreased the probability of migration intensity by 7.5%, 3.3%, 2.4%, and 1.6%, respectively. These findings further underscore the significance of local income and employment opportunities, access to irrigation, and household assets in reducing migration intensity among farming households.

3.4. Factors influencing destination choice of overseas labour migrants

presents probit model results with marginal effects of the factors influencing destination choice of labour migrants in MME countries. Education had a significant negative effect on the selection of MME countries as a migration destination among migrants. Each additional year of education reduced the likelihood of selecting MME countries as destinations by 4.2%. Nepali migrant workers are mainly employed in unskilled or low-skilled labour occupations in MME countries, where higher educational qualifications are often deemed less relevant for such occupations (GIZ & ILO Citation2015; Regmi, Paudel, and Bhattarai Citation2019; Seddon, Adhikari, and Gurung Citation2002). Hence, MME countries might have been the least preferred destination for more educated, and conversely, the most preferred destination for less educated individuals. Similarly, being a student before emigration decreased the likelihood of selecting MME countries by 14.1%, possibly because of the lack of recognition of migrants’ education in unskilled or low-skilled occupations in those destinations or the expectation of finding better opportunities in other destinations.

Table 4. Probit model results for destination choice (MME countries) of overseas labour migrants (reference group: other destinations).

Furthermore, although the GTP-FRM results in the previous section revealed a higher likelihood of participation of Janajati households in overseas labour migration, as compared to Brahmin-Chhetri communities, probit model results suggest a lower likelihood of Janajati migrants selecting MME countries as the destination. Belonging to Janajati ethnic group decreased the likelihood of choosing MME countries as a destination by 8.3%. In our study, Janajati households/migrants predominantly (about 75% of total Janajati households/migrants) included Gurungs and Magars from the hills. Given the historical migration of Gurungs and Magars to the UK for service in British Gurkha regiments and to Singapore for employment in the Singapore Police (Piya and Joshi Citation2016; Williams et al. Citation2020a), it’s plausible that such longstanding practice and legacy might have influenced their destination choices to these countries or countries other than MME countries for employment. Williams et al. (Citation2020a) also found a positive correlation between Janajati ethnic group in Nepal and the selection of wealthy Western and Asian countries as their destination.

Similarly, the economic status of households significantly affected destination selection among Nepali labour migrants, as evidenced by a 2.5% lower likelihood of selecting MME countries among those with a higher asset index. Nepali migrant workers in MME countries frequently face various challenges, including contract violations, low or unpaid wages, unsafe working conditions, poor housing, and associated services (Paoletti et al. Citation2014; Simkhada et al. Citation2017). As a result, migrants with strong economic status might have been unwilling to migrate to these destinations. Existing studies also suggest a growing trend of migration among Nepali migrants with higher economic status and education to developed countries such as the UK, North America, European countries, Australia, Japan, and the Republic of Korea (Adhikari et al. Citation2023; MOLESS Citation2022).

In contrast, migrants from households engaged in non-farming activities and with more connections to manpower agencies were 21.4% and 6.4% more likely to choose MME countries as their destination. In Nepal, individuals often engage in self-employment or non-farm businesses due to a lack of suitable employment opportunities, despite the limited financial returns from those engagements. If potential earnings from overseas employment surpass their self-employment or non-farm business income at home, it is expected that they will opt for overseas employment. On the other hand, the surge in overseas labour migration has resulted in the rapid growth of manpower agencies in Nepal, facilitating increased access to overseas employment opportunities for potential migrants (Shivakoti Citation2022). Therefore, migrants who have a greater connection with such agencies, which specialise in facilitating labour migration, particularly to MME countries are likely to choose MME countries as their destination. This finding is also corroborated by Williams et al. (Citation2020b) who also highlighted an influencing role of migration brokers or manpower agencies in common labour destinations like MME countries and the significance of social capital or networks for migration to destinations where brokers are not available.

4. Conclusion and policy implications

Overseas labour migration is a major livelihood strategy for Nepalese households, resulting in a significant labour outflow, remittance inflow, and wider socio-economic repercussions in the country. Therefore, what influences overseas labour migration and migration intensity in the households, and migrants’ destination choice are important questions with strong policy relevance to address the migration conundrum in Nepal. Our paper contributes to these questions by applying robust econometric techniques on data collected from socio-economically diverse households from the Terai (Chitwan district) and Hill (Kaski district) regions of Nepal.

Our empirical findings not only unveil the household-level factors influencing overseas labour migration and migration intensity, including the effect of individual factors on the destination choice of migrants but also provide evidence to corroborate the relevance of ‘aspirations-abilities/capabilities frameworks’ in understanding migration decision-making. Specifically, the results indicate that various factors that may shape individuals’ migration aspirations and capabilities – such as the presence of a higher proportion of educated members in the household, household’s access to credit, and migration networks – significantly and positively affect both overseas labour migration and migration intensity within households. In contrast, the findings reveal a significant negative effect of the household head’s farming experience, domestic employment of household members, possession of larger farms, access to irrigation, and higher wealth status on both overseas labour migration and migration intensity in farming households. This implies that when households have adequate employment opportunities, including skills and access to resources and services for increased agricultural production, they are less inclined to participate in overseas labour migration. Hence, the focus needs to be paid towards the creation and provision of economic opportunities, including the enhancement of access to agricultural resources and services, if the government aims to retain as well as curtail the existing or future outflow of the workforce from farming households. Conversely, strategies that facilitate the expansion of migration intermediaries and financial inclusion can be crucial for enhancing people’s access to overseas employment opportunities.

Similarly, our findings reveal a strong positive influence of households/migrants’ connections with manpower agencies in the selection of MME countries as their destination, while migrants’ education and higher wealth status negatively affected this preference. This finding suggests the significance of both human and physical capital (or educational and economic empowerment) in broadening migration choices and opportunities for prospective migrants. While migration is a multifaceted phenomenon with various forms, our study examines only overseas labour migration primarily from the household perspective, with a focus on push factors. Future studies may consider other forms and dimensions of migration and the use of diverse perspectives and factors (e.g. economic, social, political, environmental) to offer comprehensive and policy-relevant findings.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Human Ethics Research Committee of the University of Western Australia (RA/4/20/5652). All ethics protocols were maintained during the fieldwork and an informed consent form was provided to the survey participants before interviews. Earlier version of this paper was presented at the Agricultural and Resource Economics (ARE) seminar and the Australasian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society, Western Australian Branch (WA AARES) conference held at UWA in 2021. We are grateful for the constructive comments and suggestions from participants of those seminars and the conference. We also thank Dr. Krishna Prasad Paudel for his constructive feedback and suggestions on an earlier draft. Thanks are also due to field assistants for their support during the fieldwork, and to the farmers and individuals who participated in the survey and provided their valuable time and information.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, R. H. 1993. “The Economic and Demographic Determinants of International Migration in Rural Egypt.” The Journal of Development Studies 30 (1): 146–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220389308422308

- Adhikari, J. 2021. “Restructuring of Nepal’s Economy, Agrarian Change, and Livelihood Outcomes: The Role of Migration and Remittances.” In South Asia Migration Report 2020, edited by S. I. Rajan, 230–260. New York: Routledge.

- Adhikari, J., M. K. Rai, C. Baral, and M. Subedi. 2023. “Labour Migration from Nepal: Trends and Explanations.” In Migration in South Asia, edited by S. I. Rajan, 67–82. Switzerland AG: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34194-6.

- Batista, C., J. Seither, and P. C. Vicente. 2019. “Do Migrant Social Networks Shape Political Attitudes and Behavior at Home?” World Development 117: 328–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.01.019.

- Bennet, L., D. R. Dahal, and P. Govindasamy. 2008. Caste, Ethnic and Regional Identity in Nepal: Further Analysis of the 2006 Demographic and Health Surveys.

- Bezu, S., and S. Holden. 2014. “Are Rural Youth in Ethiopia Abandoning Agriculture?” World Development 64: 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.013.

- Bhandari, P. 2004. “Relative Deprivation and Migration in an Agricultural Setting of Nepal.” Population and Environment 25 (5): 475–499. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:POEN.0000036931.73465.79.

- Bhattarai, G., and B. Subedi. 2021. “Impact of COVID-19 on FDIs, Remittances and Foreign Aids: A Case Study of Nepal.” Millennial Asia 12 (2): 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0976399620974202.

- Bohra-Mishra, P., and D. S. Massey. 2011. “Individual Decisions to Migrate During Civil Conflict.” Demography 48 (2): 401–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0016-5.

- Bylander, M., and E. R. Hamilton. 2015. “Loans and Leaving: Migration and the Expansion of Microcredit in Cambodia.” Population Research and Policy Review 34 (5): 687–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-015-9367-8

- Carling, J. 2002. “Migration in the Age of Involuntary Immobility: Theoretical Reflections and Cape Verdean Experiences.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 28 (1): 5–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830120103912.

- Carling, J., and K. Schewel. 2018. “Revisiting Aspiration and Ability in International Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 945–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2017.1384146.

- Davis, B., G. U. Y. Stecklov, and P. Winters. 2002. “Domestic and International Migration from Rural Mexico: Disaggregating the Effects of Network Structure and Composition.” Population Studies 56 (3): 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720215936.

- Davis, B., and P. Winters. 2001. “Gender, Networks and Mexico-US Migration.” Journal of Development Studies 38 (2): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331322251.

- de Haas, H. 2010. “The Internal Dynamics of Migration Processes: A Theoretical Inquiry.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (10): 1587–1617. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2010.489361.

- de Haas, H. 2021. “A Theory of Migration: The Aspirations-Capabilities Framework.” Comparative Migration Studies 9 (1): 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4.

- DOFE. 2022. Countrywise Labour Approval for FY 2021/22. Kathmandu, Nepal: Government of Nepal, Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security, Department of Foreign Employment.

- Fan, C. C. 2021. “Householding and Split Households: Examples and Stories of Asian Migrants to Cities.” Cities 113: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103147.

- Faria, S., J. Rebelo, and S. Gouveia. 2020. “Firms’ Export Performance: A Fractional Econometric Approach.” Journal of Business Economics and Management 21 (2): 521–542. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2020.11934.

- Fishman, R., and S. Li. 2022. “Agriculture, Irrigation and Drought Induced International Migration: Evidence from Mexico.” Global Environmental Change 75: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102548.

- Ghimire, T., A. P. Harou, and S. Balasubramanya. 2023. “Migration, Gender Labor Division and Food Insecurity in Tajikistan.” Food Policy 116: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2023.102438.

- GIZ & ILO. 2015. Labour Market Trends Analysis and Labour Migration from South Asia to Gulf Cooperation Council Countries, India and Malaysia. Kathmandu: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH and International Labour Organization (ILO).

- Goli, S., N. K. Maurya, R. Moradhvaj, and P. Bhandari. 2019. “Regional Differentials in Multidimensional Poverty in Nepal: Rethinking Dimensions and Method of Computation.” SAGE Open 9 (1), https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019837458.

- Gurung, Y. B. 2012. “Migration from Rural Nepal: A Social Exclusion Framework.” HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies 31 (1): 37–51.

- Gurung, O. 2019. “Social Inclusion/Exclusion: Policy Discourse in Nepal.” In Including the Excluded in South Asia, 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9759-3_4

- Hagen-Zanker, J., H. Postel, and E. M. Vidal. 2017. Poverty, Migration and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. London: Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

- Heckman, J. J. 1979. “Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error.” Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 47: 153–161. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912352.

- International Dalit Solidarity Network. 2018. Brief Paper for the ICERD Committee Members. Accessed 21 April 2024.

- IOM. 2019. Migration in Nepal: A Country Profile 2019. Kathmandu, Nepal: International Organization for Migration.

- IOM. 2024. World Migration Report 2024. Geneva: International Organization for Migration (IOM).

- Jaquet, S., T. Kohler, and G. Schwilch. 2019. “Labour Migration in the Middle Hills of Nepal: Consequences on Land Management Strategies [Article].” Sustainability (Switzerland) 11 (5): Article 1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051349.

- Kafle, K., R. Benfica, and P. Winters. 2020. “Does Relative Deprivation Induce Migration? Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 102 (3): 999–1019. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajae.12007.

- Limbu, A. 2022. “‘A Life Path Different from One of Labour in the Gulf’: Ongoing Mobility among Nepali Labour Migrants in Qatar and Their Families.” Global Networks 23 (2): 362–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12396.

- Lokshin, M., M. Bontch-Osmolovski, and E. Glinskaya. 2010. “Work-related Migration and Poverty Reduction in Nepal.” Review of Development Economics 14 (2): 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2010.00555.x.

- Maharjan, A., S. Bauer, and B. Knerr. 2013. “International Migration, Remittances and Subsistence Farming: Evidence from Nepal.” International Migration 51 (s1): e249–e263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2012.00767.x.

- Mak, J., C. Zimmerman, and B. Roberts. 2021. “Coping with Migration-Related Stressors: A Qualitative Study of Nepali Male Labour Migrants.” BMC Public Health 21 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11192-y.

- Massey, D., J. Arango, G. Hugo, A. Kouaouci, A. Pellegrino, and J. Taylor. 1993. “Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal.” Population and Development Review 19 (3): 431–466. https://doi.org/10.2307/2938462

- Mishra, K., O. Kondratjeva, and G. E. Shively. 2022. “Do Remittances Reshape Household Expenditures? Evidence from Nepal.” World Development 157: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.105926.

- MOALD. 2022. Statistical Information on Nepalese Agriculture (2020/21). Singhdurbar, Kathmandu, Nepal: Government of Nepal, Ministry of Agriculture & Livestock Development, Planning & Development Cooperation Coordination Division, Statistics and Analysis Section.

- MOLE. 2018. Labour Migration for Employment, A Status Report for Nepal: 2015/16-2016/17. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal, Ministry of Labour and Employment.

- MOLESS. 2020. Nepal Labour Migration Report 2020. Kathmandu: Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security, Government of Nepal.

- MOLESS. 2022. Nepal Labour Migration Report 2022. Singhadarbar, Kathmandu: Government of Nepal, Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security.

- Monteiro, S. 2022. “Extended Family Migration Decisions: Evidence from Nepal.” SN Social Sciences 2 (11): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00506-5.

- Mora, J., and J. E. Taylor. 2006. “Determinants of Migration, Destination, and Sector Choice: Disentangling Individual, Household, and Community Effects.” In International Migration, Remittances, and the Brain Drain, edited by C. Ozden, and M. Schiff, 21–51. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Neubauer, J. 2024. “Envisioning Futures at New Destinations: Geographical Imaginaries and Migration Aspirations of Nepali Migrants Moving to Malta.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (12): 3049–3068. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2024.2305281.

- NRB. 2021. Financial Access in Nepal: Exploring the Feature of Deposit Accounts of A, B, C Class BFIs. Kathmandu: Nepal Rastra Bank.

- Otte, M. J., and P. Chilonda. 2002. Cattle and Small Ruminant Production Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Paoletti, S., E. Taylor-Nicholson, B. Sijapati, and B. Farbenblum. 2014. “Migrant Workers’ Access to Justice at Home: Nepal.” In Migrant Workers’ Access to Justice Series, 14–22. New York: Open Society Foundations.

- Papke, L. E., and J. M. Wooldridge. 1996. “Econometric Methods for Fractional Response Variables with an Application to 401(k) Plan Participation Rates.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 11 (6): 619–632. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1255(199611)11:6<619::AID-JAE418>3.0.CO;2-1.

- Piya, L., and N. P. Joshi. 2016. “Migration and Remittance in Nepal: A Review of the Push-Pull Factors and Socioeconomic Issues.” Journal of Contemporary India Studies: Space and Society 6: 41–53.

- Pradhan, K. C., and K. Narayanan. 2019. “Intensity of Labour Migration and its Determinants: Insights from Indian Semi-Arid Villages.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science 3 (3): 955–994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-019-00133-8

- Rahut, D. B., J. P. Aryal, P. Chhay, and T. Sonobe. 2022. “Ethnicity/Caste-Based Social Differentiation and the Consumption of Clean Cooking Energy in Nepal: An Exploration Using Panel Data.” Energy Economics 112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106080.

- Rajan, S. I., K. Keshri, and P. Deshingkar. 2023. “Understanding Temporary Labour Migration Through the Lens of Caste: India Case Study.” In Migration in South Asia: IMISCOE Regional Reader, edited by S. I. Rajan, 97–110. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- Ramalho, J. J. S., and J. V. da Silva. 2009. “A Two-Part Fractional Regression Model for the Financial Leverage Decisions of Micro, Small, Medium and Large Firms.” Quantitative Finance 9 (5): 621–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697680802448777.

- Ratha, D., V. Chandra, E. J. Kim, S. Plaza, and W. Shaw. 2023. Migration and Development Brief 39: Leveraging Diaspora Finances for Private Capital Mobilization. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Regmi, M., K. P. Paudel, and K. Bhattarai. 2019. “Migration Decisions and Destination Choices.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 25 (2): 197–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2019.1643195.

- Roodman, D. 2011. “Fitting Fully Observed Recursive Mixed-Process Models with Cmp.” The Stata Journal 11 (2): 159–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1101100202

- Root, B. D., and G. F. De Jong. 1991. “Family Migration in a Developing Country.” Population Studies 45 (2): 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000145406

- Roy, A. K., R. B. Bhagat, K. C. Das, S. Sarode, and R. S. Reshmi. 2021. A Report on Causes and Consequences of Out-Migration from Middle Ganga Plain. Mumbai: Department of Migration and Urban Studies, International Institute for Population Sciences.

- Rozelle, S., J. E. Taylor, and A. de Brauw. 1999. “Migration, Remittances, and Agricultural Productivity in China.” American Economic Review 89 (2): 287–291. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.2.287.

- Schewel, K., and S. Fransen. 2018. “Formal Education and Migration Aspirations in Ethiopia.” Population And Development Review 44 (3): 555–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12159.

- Schwiebert, J. 2018. A Sample Selection Model for Fractional Response Variables. Working Paper Series in Economics, No. 382, Leuphana Universität Lüneburg, Institut für Volkswirtschaftslehre, Lüneburg.

- Schwiebert, J., and J. Wagner. 2015. A Generalized Two-Part Model for Fractional Response Variables with Excess Zeros. Beiträge zur Jahrestagung des Vereins für Socialpolitik 2015: Ökonomische Entwicklung - Theorie und Politik- Session: Microeconometrics, No. B04-V2, ZBW - Deutsche Zentralbibliothek für Wirtschaftswissenschaften, Leibniz-Informationszentrum Wirtschaft.

- Seddon, D., J. Adhikari, and G. Gurung. 2002. “Foreign Labor Migration and the Remittance Economy of Nepal.” Critical Asian Studies 34 (1): 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/146727102760166581.

- Sedova, B., and M. Kalkuhl. 2020. “Who are the Climate Migrants and Where Do They Go? Evidence from Rural India.” World Development 129: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104848.

- Sha, H., and Y. Khor. 2024. “Cross-Border Mobility, Inequality and Migration Intermediaries: Labour Migration from Nepal to Malaysia.” International Migration 62 (2): 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.13232.

- Shakya, S., S. Bhaju, S. Shrestha, R. Tuladhar, and S. Tuladhar. 2016. Making Access Possible, Nepal: Detailed Country Report.

- Sherpa, D. 2010. Labour Migration and Remittances in Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal: ICIMOD.

- Shivakoti, R. 2022. “Temporary Labour Migration in South Asia: Nepal and its Fragmented Labour Migration Sector.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2022.2028354.

- Shonchoy, A. S. 2015. “Seasonal Migration and Microcredit During Agricultural Lean Seasons: Evidence from Northwest Bangladesh.” The Developing Economies 53 (1): 1–26.

- Sijapati, B., A. S. Lama, J. Baniya, J. Rinck, K. Jha, and A. Gurung. 2017. Labour Migration and the Remittance Economy: The Socio-Political Impact. Kathmandu, Nepal: Centre for the Study of Labour and Mobility (CESLAM), Social Science Baha.

- Sijapati, B., and A. Limbu. 2012. Governing Labour Migration in Nepal: An Analysis of Existing Policies and Institutional Mechanisms. Centre for the Study of Labour and Mobility (CESLAM), Social Science Baha, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- Simkhada, P. P., P. R. Regmi, E. van Teijlingen, and N. Aryal. 2017. “Identifying the Gaps in Nepalese Migrant Workers’ Health and Well-Being: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Travel Medicine 24 (4): Article tax021. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/tax021.

- Srivastava, R., and A. K. Pandey. 2017. Internal and International Migration in South Asia: Drivers, Interlinkage and Policy Issues. New Delhi: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

- Taylor, E. J. 1999. “The new Economics of Labour Migration and the Role of Remittances in the Migration Process.” International Migration 37 (1): 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00066

- Tegegne, A. D., and M. Penker. 2016. “Determinants of Rural out-Migration in Ethiopia: Who Stays and Who Goes?” Demographic Research 35 (34): 1011–1043. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2016.35.34.

- Thapa Magar, D. B., S. Pun, R. Pandit, and M. F. Rola-Rubzen. 2021. “Pathways for Building Resilience to COVID-19 Pandemic and Revitalizing the Nepalese Agriculture Sector.” Agricultural Systems 187: 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.103022.

- UNDESA. 2020. International Migration 2020 Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/452). New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

- Williams, N. E., P. Bhandari, L. Young-DeMarco, J. Swindle, C. Hughes, L. Chan, A. Thornton, and C. Sun. 2020a. “Ethno-caste Influences on Migration Rates and Destinations.” World Development 130: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104912.

- Williams, N. E., C. Hughes, P. Bhandari, A. Thornton, L. Young-DeMarco, C. Sun, and J. Swindle. 2020b. “When Does Social Capital Matter for Migration? A Study of Networks, Brokers, and Migrants in Nepal.” International Migration Review 54 (4): 964–991. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918319882634.

- Winters, P., A. De Janvry, and E. Sadoulet. 2001. “Family and Community Networks in Mexico-US Migration.” Journal of Human Resources, 159–184.

- Wooldridge, J. M. 2010. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Wouterse, F., and J. E. Taylor. 2008. “Migration and Income Diversification:: Evidence from Burkina Faso.” World Development 36 (4): 625–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.03.009.

- Wulff, J. N. 2019. “Generalized two-Part Fractional Regression with cmp.” The Stata Journal 19 (2): 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X19854017

- Xiong, S., Y. Wu, S. Wu, F. Chen, and J. Yan. 2020. “Determinants of Migration Decision-Making for Rural Households: A Case Study in Chongqing, China.” Natural Hazards 104 (2): 1623–1639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-04236-w.

- Yan, X., S. Bauer, and X. Huo. 2014. “Farm Size, Land Reallocation, and Labour Migration in Rural China.” Population, Space and Place 20 (4): 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1831.

- Zaveri, E. D., D. H. Wrenn, and K. Fisher-Vanden. 2020. “The Impact of Water Access on Short-Term Migration in Rural India.” Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 64 (2): 505–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8489.12364.