ABSTRACT

Refugee women face significant challenges when seeking employment in Western host countries. To advance gender-sensitive perspectives within migration and refugee research, this study examines differences in employment outcomes between refugee women and men. Specifically, this study provides a nuanced picture of six indicators of employment outcomes, including pay, fixed-term versus permanent employment contract, overqualification, career prospects, an at-home feeling in the workplace and the ability to talk to colleagues about personal problems. The study also shows that individuals’ occupational status plays a role in gender disparities. Our findings, based on a recent survey of refugees working in Austria, reveal several gender gaps, with an especially significant gap regarding fixed-term employment contracts. Refugee women, who are more likely to be disadvantaged in employment outcomes, benefit disproportionately from working in high-skill jobs. The findings underscore the complex nature of gendered patterns in labour market integration of refugees and imply specific policies addressing gender inequality in this setting.

Introduction

With ongoing political conflicts, natural disasters and famines worldwide causing people to leave their homes and seek asylum in foreign countries, the question of how refugees can lead a good life and find decent employment in host countries continues to be a pressing concern for policymakers and researchers alike. However, the specific employment circumstances of refugee women are rarely considered, even though among the 2.2 million working-age refugees granted protection status in Europe over the past decade,Footnote1 one in three was a woman (Eurostat Citation2024a). Research indicates that refugee women are less likely to be employed than men (Brell, Dustmann, and Preston Citation2020; Fasani, Frattini, and Minale Citation2022). They face particular challenges in the labour market because they are at the intersection of multiple axes of disadvantage, including gender, ethnicity, religion and legal status (Liebig and Tronstad Citation2018; Senthanar et al. Citation2021a; Tomlinson Citation2010).

However, while prior research has primarily examined the barriers that refugee women face in finding employment in Western countries, there is a dearth of scholarly research on those who have succeeded. The few existing studies point to distinct gender gaps. For instance, refugee women in the United States have been found to earn hourly wages that are less than one-third of those of men (Tran and Lara-García Citation2020). Moreover, refugee women tend to be overrepresented in elementary occupations and less likely than men to work in skilled or high-skill jobs in Germany (Brücker, Kosyakova, and Schuß Citation2020), the Netherlands (De Vroome and van Tubergen Citation2010), United Kingdom (Cheung and Phillimore Citation2017) and Austria (Leitner and Landesmann Citation2020). Nonetheless, prior research is inconclusive, as Kone, Ruiz, and Vargas-Silva (Citation2019) found refugee women in the United Kingdom to outperform men on wages by 6 percent, and Tran and Lara-García (Citation2020) found that refugee women in the United States are 2.5 times more likely than men to be in a professional occupation and three times less likely in a blue-collar occupation.

Although comparisons across studies are difficult because they vary in terms of the host countries’ institutional contexts, refugee entry cohorts and study time frames, the overall picture indicates that there is a gendered pattern in refugees’ employment outcomes that is worth exploring in more detail. Furthermore, previous studies have focused on wage levels and occupational status, but we know little about other outcomes such as career prospects, social belonging and support from colleagues at the workplace. Such aspects appear to be particularly important for refugees, whose lives are characterised by vocational and social losses and overall precarity (Cheung and Phillimore Citation2017; Jackson and Bauder Citation2014).

Hence, this study examines a broader range of employment outcomes of refugee women and men with the aim of identifying potential gender inequality. Based on frameworks established in the literatures on job quality (Holman Citation2013; Muñoz de Bustillo et al. Citation2011) and refugee integration (Ager and Strang Citation2008), and building upon previous research on refugees’ employment outcomes, we consider the following six indicators: pay, fixed-term versus permanent contract, overqualification, career prospects, a sense of feeling at home in the workplace and being able to talk to colleagues about personal problems.

Furthermore, this study places special emphasis on refugees’ occupational status. Informed by labour segmentation theory (Doeringer and Piore Citation1971; Piore Citation1979) and feminist scholarship highlighting that the manifestation and consequences of gender-related differences vary depending on context (Bloch Citation2008; Grimshaw et al. Citation2017), we examine how potential gender inequality among refugees plays out across varying occupational status groups. Thus, the following two research questions guided this study: Are there differences in employment outcomes between refugee women and men? And, if so, how are such differences structured by occupational status?

To address these questions, we draw on recent survey data from Austria, focusing on refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq, which represent main countries of origin (Eurostat Citation2024a). Austria provides an interesting context for researching refugees’ employment outcomes as in the last decade, it has granted protection to over 90,000 refugees, including more than 30,000 women (Eurostat Citation2024a). Given its relatively small population of around 9 million, Austria is among the top receiving countries in Europe (Eurostat Citation2024a).

While we find marked gender gaps in pay and fixed-term employment that disadvantage women, and gaps in overeducation that disadvantage men, only the differences in fixed-term employment remain statistically significant after controlling for a number of factors related to refugees’ sociodemographic and family characteristics, their human and social capital as well as workplace features. Occupational status plays a role in gender gaps regarding fixed-term employment, overqualification and social workplace aspects. Our study contributes to a nuanced understanding of refugees’ employment outcomes and gender-sensitive perspectives in migration and refugee research by expanding scholarly attention from economic outcomes to developmental and social workplace aspects and demonstrating that occupational status matters in gender gaps. Therewith we go beyond previous research, which either did not consider the specificities of refugee women in paid employment or concentrated on employment rates. Furthermore, our findings provide a basis for policy recommendations aimed at reducing gender inequality among refugees.

Theoretical background

Employment outcomes

To identify indicators of potential gender disparities in refugees’ employment outcomes, we draw upon established frameworks proposed in the literature on job quality, which has highlighted the importance of considering multiple aspects when examining employment conditions (Holman Citation2013; Muñoz de Bustillo et al. Citation2011). Furthermore, to take account of the particular circumstances of refugees, our choice of indicators is guided by the comprehensive framework on refugee integration proposed by Ager and Strang (Citation2008). Originally referring to the societal level, this framework emphasises aspects such as refugees’ stability, safety, social connectedness and belonging, which are also relevant in workplace contexts (Ortlieb and Knappert Citation2023). Furthermore, we build upon prior studies addressing multiple dimensions of refugees’ employment outcomes, in particular Delaporte and Piracha (Citation2018), Lamba (Citation2003) as well as Ortlieb and Weiss (Citation2020).

Based on this research, we consider the following six indicators. First, pay, since this is the commonly used measure of economic inequality, and work income is paramount for refugees’ financial independency and living standard. Second, whether a person is employed on a fixed-term or permanent basis as this is another ‘hard’ aspect of employment contracts, related to both economic and social safety and stability. Third, individuals’ perceived overqualification, indicating the extent to which they are able to find commensurate employment and leverage on their educational attainment and work experience. This is relevant not only for higher-qualified individuals but also for those with little or no formal education (as is more common in some of the refugees’ countries of origin compared to Austria) but extensive work experience, who can also perceive overqualification. Fourth, we consider individuals’ perceived career prospects since opportunities for long-term development are associated with feelings of safety and hope, which are vital for refugees’ psychological well-being and resilience (Tomlinson Citation2010; Wehrle, Kira, and Klehe Citation2019). As is common in career research, by the term ‘career’, we refer not only to the successful professional trajectories of highly qualified individuals but to any ‘sequence of positions in social, temporal and geographical spaces’ (Mayrhofer et al. Citation2023, 2). Positive career prospects also can mean that a worker is given additional tasks or sees the current job as a stepping stone. Perceived overqualification and career prospects are also relevant because of their important role in the self-identity and self-value of refugees, who typically experience severe identity crises and social status loss due to their flight (Eggenhofer-Rehart et al. Citation2018; Hunt Citation2008; Jackson and Bauder Citation2014; Smyth and Kum Citation2010). This is not only a problem for highly skilled individuals, but for all refugees, as they realise that their skills are generally not useful or recognised in the host country. Fifth, we consider an individual’s sense of feeling at home in the workplace as a crucial social aspect of employment, because refugees have lost their homes, and social belonging is important for their well-being (Tomlinson Citation2010). Sixth, being able to talk to colleagues about personal problems is another important social aspect as this indicates social connectedness and support (Ager and Strang Citation2008).

While a few previous studies have examined the first three of these indicators, career prospects and the social aspects at the workplace remain unexplored. There is also no conclusive theoretical explanation for potential differences in these employment outcomes between refugee women and men. Therefore, we draw on established, broader theories regarding gender inequality in the labour market, which we introduce in the next section and subsequently apply to our reasoning regarding the role of occupational status in gender disparities.

Gender gaps in employment outcomes

The multidisciplinary literature on labour market inequality offers several theoretical arguments to explain disparities between refugee women and men in employment outcomes. Human capital theory posits that women, anticipating family-related career interruptions, may refrain from investment in their skills and forego the otherwise better employment outcomes (Becker Citation1985). Although critics note the theory’s neglect of institutional and societal constraints of women’s choices (e.g. Rubery and Grimshaw Citation2015), addressing knowledge and skills seems crucial when explaining differences in employment outcomes.

Refugees’ relevant human capital comprises education and work experience from both the country of origin and host country as well as local language skills. Many lack formal certificates or those that they have are not recognised in the host country (Lee et al. Citation2020). Moreover, employers tend to favour local qualifications and work experience (Diedrich and Styhre Citation2013; Eggenhofer-Rehart et al. Citation2018), disadvantaging refugee women who struggle to secure initial jobs and gain local experience, sometimes exacerbated by lower participation in language classes due to caregiving responsibilities (Brücker, Kosyakova, and Vallizadeh Citation2020).

The notion of social capital (Granovetter Citation1974) is another prominent approach to explaining gender differentials, asserting that interpersonal networks help securing employment and advancing in organisations. Prior studies have indicated that refugees’ connections with locals generally lead to better employment opportunities compared to contacts within their own ethnic community (De Vroome and van Tubergen Citation2010; Ortlieb and Weiss Citation2020), whereby refugee women tend to have less frequent regular contact with locals than men (Schmidt, Jacobsen, and Krieger Citation2020).

Furthermore, reasoning around societal gender norms states that such norms often steer women towards social and care occupations, characterised by lower pay and limited opportunity for career advancement, while men opt for higher-rewarding technical fields (Senthanar et al. Citation2021b). Moreover, traditional gender roles confine refugee women, especially those with kinship responsibilities, to household duties, resulting in poorer employment outcomes (Bakker, Dagevos, and Engbersen Citation2017; Salikutluk and Menke Citation2021). However, whereas some scholars argue that refugees tend to adhere to more traditional notions of gender roles than those prominent in Western host countries (e.g. Albrecht, Hofbauer Pérez, and Stitteneder Citation2021), others point out that selection processes result in individual gender attitudes corresponding more closely to European host countries than to countries of origin (Kostenko Citation2019) and that the refugee experience itself modifies gender roles and (self-) views (Habash and Omata Citation2023).

Finally, discrimination by employers based on attributes such as gender, ethnicity, race, religion or refugee status is a prominent approach in explaining employment disparities (Deitch et al. Citation2003). Despite legal prohibitions, discrimination against refugees persists in recruitment, performance appraisals and other workplace practices (Bloch Citation2008; Cheung et al. Citation2022), with several qualitative studies highlighting experienced discrimination of refugee women (Colic-Peisker and Tilbury Citation2006; Fozdar and Torezani Citation2008; Knappert, Kornau, and Figengül Citation2018; Tomlinson Citation2010). Job agencies and caseworkers may also perpetuate stereotypes, for example concerning refugee men as hardworking and robust (Bullinger, Schneider, and Gond Citation2023) and women as ‘naturally’ good cooks (Koyama Citation2015), or through directing refugee women into low-skill jobs in elderly care (Otmani Citation2023).

In summary, previous research has shown how various interconnected factors can lead to disparities in employment outcomes between refugee women and men, frequently resulting in disadvantages for women. Building on this research, which focused on employment probability and pay gaps as indicators of inequality, we anticipate similar gender discrepancies, disadvantaging women, across all six indicators that we examine in this study.

The moderating role of occupational status

The theoretical reasoning concerning gender gaps, referring to refugees’ human and social capital, societal gender norms and discrimination by employers, can also be applied to our second research question addressing the role of occupational status in these disparities. The literature on labour market segmentation, in the tradition of Doeringer and Piore (Citation1971) and Piore (Citation1979), as well as research on gender and ethnic segregation (Bloch Citation2008; Brynin and Güveli Citation2012; Grimshaw et al. Citation2017) suggest that refugees, especially refugee women, are relegated to low-skill jobs and labour market segments characterised by low pay and poor working conditions. Moreover, minority groups tend to be confined to inferior job positions characterised by robust and impenetrable barriers. Similar to the Glass Ceiling that hinders women from advancing to higher-status positions, Lee et al. (Citation2020) introduced the metaphor of a Canvas Ceiling to denote the ‘systemic, multilevel barrier to refugee workforce integration and professional advancement’ (206). The authors argue that refugees must overcome additional hurdles to secure employment commensurate with their skills and offering opportunities for career development.

Building on these arguments, we maintain that breaking through the Canvas Ceiling and the Glass Ceiling is particularly impactful for refugee women. If they have managed to secure skilled or high-skill jobs, their gender may have a weaker impact on employment outcomes. Given that refugee women may require more human and social capital than men to reach such positions, as well as appropriate gender norms and the ability to overcome possible discrimination, this surplus of resources may positively affect their employment outcomes. In skilled or high-skill jobs, refugee women may also receive greater recognition for their skills and contributions to the organisation, which could enhance their sense of belonging and career prospects. Thus, while we assume that there are disparities between refugee women and men in employment outcomes that disadvantage refugee women, higher occupational status may attenuate gender gaps. Specifically, gender may have a lesser influence on employment outcomes in skilled or high-skill jobs compared to elementary jobs. Put differently, while refugees in skilled or high-skill jobs generally achieve better employment outcomes compared to those in low-skill jobs, this is even more true for refugee women than for men.

The Austrian context

Austria has a rich history of hosting refugees. From 2012 to 2021, the country received nearly 300,000 asylum applications, including approximately 83,500 (27.9%) from women, with individuals predominantly originating from Syria, Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq (BMI Citation2024). Integrating refugees into the labour market has a high political priority, aimed at easing the strain on the welfare system (Expertenrat für Integration Citation2023). Law on labour market access has been changed several times over the last decade, as part of an increasingly restrictive immigration and asylum policy as well as in response to the needs of employers. Basically, asylum seekers are not allowed to engage in paid work. Immediately after being admitted to the asylum procedure, they are permitted to carry out minor communal tasks in their accommodations, municipalities or other state institutions for a little financial recognition. Three months after admission to the asylum procedure, they may also engage in other activities, such as in private households, tourism or agriculture, or as self-employed (which is challenging due to numerous restrictions that apply to all self-employed individuals in Austria). At times, asylum seekers aged under 25 were allowed to pursue paid vocational training in occupations facing shortages. In principle, but very rarely in practice, asylum seekers may engage in employment if granted a specific work permit following a labour market examination by the public employment service.

Upon obtaining a positive status (asylum, subsidiary protection or humanitarian grounds), refugees have unrestricted access to the labour market in Austria. The majority registers with the public employment service, where they take part in skills assessments and counselling sessions and where they also can apply for social welfare (to which they are entitled like natives). Furthermore, there are mandatory language, values and orientation courses as well as various programmes fostering labour market integration. Some initiatives specifically target women. For instance, ‘Competence Checks for Refugee Women’, a seven-week programme comprising skills assessment, counselling and job search assistance, gained international recognition with the United Nations Public Service Award in 2019. Another important programme is the mandatory integration year for unemployed refugees (positive status holders), providing training, counselling and internships. Ortlieb et al. (Citation2020) found that participating women are more likely than non-participants to find employment, but this is not the case for men. This finding may reflect the specific Canvas Ceiling for refugee women, as the integration year compensates for generally more severe labour market obstacles.

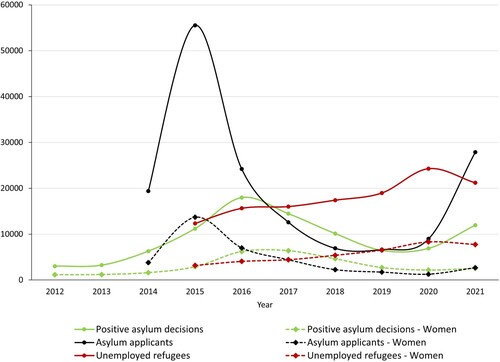

offers further context, presenting official statistics on asylum applications, positive decisions (indicating recognised refugees) and unemployed refugees. The sharp increase in asylum applications from both women and men in 2015 is evident, along with the subsequent trends of positive decisions and rise in unemployed refugees. While annual data on employed refugee women and men are not available for our study period, evidence from Jestl et al. (Citation2022), as well as Jestl and Tverdostup (Citation2023) indicates that refugee women are less likely than men to be in paid employment and their job search takes longer. These findings are consistent with studies from other European countries as well as Australia, Canada and the United States (e.g. Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2017; Brell, Dustmann, and Preston Citation2020; Fasani, Frattini, and Minale Citation2022; Schultz-Nielsen Citation2017). Qualitative studies additionally show that Austrian employers’ expectations regarding formal qualifications and local language skills pose particular barriers for refugees (Eggenhofer-Rehart et al. Citation2018; Verwiebe et al. Citation2019), and refugee women require a special set of individual, institutional and social resources to overcome the immense hurdles (Schiestl, Kittel, and Bollerhoff Citation2021).

Figure 1. Asylum applicants, positive asylum decisions and unemployed refugees in Austria, 2012–2021.

Notes: Asylum applicants and positive asylum decisions: displayed are annual totals of individuals aged 18–64; decisions include first instance and final decisions (data source: Eurostat Citation2024a, Citation2024b); unemployed refugees: annual averages of positive status holders registered with the public employment service (data source: Parlamentsdirektion Österreich Citation2023); missing values due to data limitations.

Method

Data and participants

This study is based on survey data from the FIMAS panel project, which has been collecting socioeconomic data on refugees in Austria since 2016 (Baumgartner, Palinkas, and Bilger Citation2023). The survey uses a stratified random sample of register data from the national public employment service, which includes all individuals who have been granted asylum or subsidiary protection and have received social welfare benefits, job-search assistance and/or training. The sample stratification criteria are gender, citizenship and province of residence. The target group are people aged 15–64 from Syria, Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq. Participants were invited by email or via text messages and received vouchers for 7 euro or 10 euro for their first-time or recurrent participation, respectively. Participation was voluntary upon informed consent. The survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Graz (Austria).

The data were collected between February and April 2022 using an online self-completion questionnaire (99%) and telephone interviews by trained native speakers (1%) in Arabic, Farsi or German. The response rate was 9.4 percent. To address sampling bias and non-response bias, we use weight factors based on gender, citizenship and age. The sample includes 2716 respondents who arrived in Austria between 2011 and 2021. This study focuses on refugees in paid employment of at least 8 h per week, which applies to 1379 respondents, including 477 women (34.6%). The average age is 33.4 years (standard deviation: 8.8 years). Fifty-five percent have Syrian citizenship, 21.5 percent Afghan, 15.5 percent Iranian and 7.9 percent Iraqi. The Appendix provides additional sample characteristics.

Our data have several strengths. Although surveying refugees is challenging in terms of access, ethics and language (Kühne, Jacobsen, and Kroh Citation2019), the sample is comparatively large, especially with regard to women. Furthermore, the data are relatively recent, cover the most important countries of origin of refugees in Austria over the last decade and include detailed information about employment outcomes and occupations.

Measures

The questionnaire is based on established surveys, in particular the German IAB-BAMF-SOEP, the European Working Conditions Survey and the World Values Survey.

Dependent variables

The six employment outcomes were measured as follows. (1) Pay – respondents indicated their gross wages in the previous month and their weekly working hours; we calculated the hourly wages (in euro); (2) fixed-term contract – this variable was coded 1 if a respondent held a fixed-term employment contract and coded 0 for a permanent contract; (3) overqualification – respondents indicated to what extent their educational attainments and prior work experience matched their jobs; this variable was coded 1 if education and experience exceeded the job’s requirements and 0 otherwise; (4) career prospects – respondents rated the statement ‘My job offers good prospects for career advancement’ on a 5-point scale from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘fully agree’); (5) feeling at home – respondents rated the statement ‘I feel “at home” in this organisation’ on a 5-point scale from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘fully agree’); (6) talking about problems – respondents rated the statement ‘I can also talk to my colleagues about personal problems’ on a 5-point scale from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘fully agree’).

Explanatory variables

We focus on two variables. (1) Gender – coded 1 for self-identified woman and 0 for self-identified man; (2) occupational status – responses to open-ended questions were coded into occupational groups according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations scheme (ISCO-08) and occupational groups were collapsed into three categories: elementary jobs (ISCO = 9; e.g. cleaners, manufacturing labourers, transport and logistics labourers); skilled jobs (ISCO = 4–8; e.g. plant and machine operators, cooks and waiters, sales workers, clerks); and high-skill jobs (ISCO = 1–3; e.g. technicians and associated professionals, health professionals, teachers, software developers, managers).

Controls

We included the following variables that proved relevant in previous studies (e.g. Andersson Joona and Gupta Citation2022; Bakker, Dagevos, and Engbersen Citation2017; Brell, Dustmann, and Preston Citation2020; Delaporte and Piracha Citation2018; Minor and Cameo Citation2018; Tran and Lara-García Citation2020). All of the categorical variables were (dummy-) coded as ‘yes’ = 1 and ‘no’ = 0. (1) Sociodemographics: citizenship (Syria, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq); age (in years); length of stay in Austria (in years); place of residence (Vienna [capital], large city, small city, village); being Muslim (yes/no); psychological distress (Kessler index, ranging from 10 = low to 50 = high); (2) human capital: foreign educational attainment (low [no + ISCED = 0–2], intermediate [ISCED = 3–4], high [ISCED = 5–8]); education in Austria (yes/no); foreign work experience (yes/no); German fluency (yes if a respondent rated their command of spoken German as ‘good’ or ‘very good’, otherwise no); (3) family: partner in household (yes/no); children under 18 in household (yes/no); children under 6 in household (yes/no); (4) workplace: industrial sector (11 categories); size of employer (small [1–20 employees], medium [21–200 employees], large [more than 200 employees]); part-time work (yes if up to 20 hours per week, otherwise no); methods used to find the current job (public employment service, contacts with locals, contacts with co-ethnics [multiple responses were allowed]); (5) social capital: network with locals (no, 1–3 people, more than 3 people); network with co-ethnics (no, 1–3 people, more than 3 people).

Analytical strategy

To examine differences in employment outcomes between refugee women and men and the moderating role of occupational status, we first conducted descriptive and bivariate statistical analyses and then estimated multivariate regression models. We used varying model estimation techniques depending on the scale level of the dependent variables: (1) Heckman maximum likelihood estimation for pay ([log] hourly wages); (2) probit models for the probability of having a fixed-term contract and being overqualified; and (3) ordered probit models for career prospects, feeling at home in the workplace and being able to talk to colleagues about personal problems.

Following previous research (e.g. De Vroome and van Tubergen Citation2010; Giri Citation2018), we used the method proposed by Heckman (Citation1979) to check whether selection into employment is correlated with the employment outcomes. For the exclusion restriction (i.e. variables that determine selection into employment but are not included in the outcome equations), we used family-related variables (partner and/or children in the household). Likelihood ratio tests indicated that selection bias was an issue only for refugees’ pay (rho = 0.855; p < 0.001) and not for the other five dependent variables. Thus, we applied the Heckman correction only to the pay model.

To examine the robustness of our findings, we estimated separate regression models for each gender because some factors may affect employment outcomes in different ways for women and men. The results were largely the same as those from the combined models (see the online Appendix). Furthermore, we conducted analyses applying the Heckman correction for all variables and ordinary least square regression for the pay variable. Since the results were very similar in both cases, we assume that the chosen models are the most appropriate for our analysis.

Findings

Bivariate analyses

provides a gender breakdown of the descriptive statistics for refugees’ employment outcomes and occupational status. A table showing descriptives for the full set of study variables is included in the online Appendix.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

There are marked differences in employment outcomes between refugee women and refugee men. Women earn on average 4.76 euro per hour less than men. The share of those holding fixed-term contracts is almost 10 percentage points higher for women than for men. Conversely, the proportion of those who consider themselves overqualified is 4.5 percentage points lower for women than for men. These gender-related differences are statistically significant (p < 0.001). Furthermore, women tend to evaluate their career prospects and their sense of feeling at home in the workplace slightly higher than men but tend to evaluate their opportunities to talk to colleagues about personal problems slightly lower. These results are, however, not statistically significant (p ≥ 0.1).

The distribution across occupational status groups likewise shows a gendered pattern. Almost one in four women (23.4%) works in a high-skill job compared to only about one in six men (16.1%). Correspondingly, the shares of those in elementary and skilled jobs are smaller for women than for men. Thus, while refugee women tend to work more often than men in high-skill jobs and report less overqualification, they experience worse employment outcomes in terms of lower pay and more fixed-term employment.

Multivariate analyses

The following presentation concentrates on gender as explanatory variable and occupational status as moderator. The online Appendix provides results for the full models, including controls.

Pay

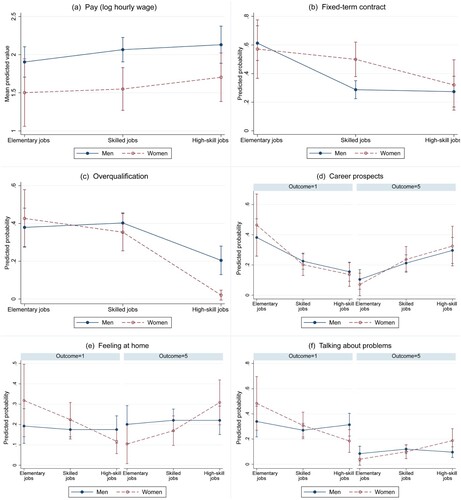

Column (1) in displays regression results on pay. The coefficient for gender shows a statistical tendency (coeff. = −0.402; p = 0.057). This result confirms the gender pay gap to the disadvantage of refugee women that we observed in the bivariate analysis, although it can be partly attributed to other factors related to sociodemographic and family characteristics, human and social capital as well as workplace features. As to the moderating role of occupational status, while panel (a) of suggests a slightly larger gender pay gap for those working in skilled jobs, the coefficients are not statistically significant (interaction term for skilled job: coeff. = −0.114; p = 0.564; for high-skill job: coeff. = −0.024; p = 0.909).

Figure 2. Predictive margins of gender and occupational status on refugees’ employment outcomes (based on the models presented in ).

Notes: Plotted are mean predicted values conditional on gender and occupational status (panel (a)) and predictive margins for levels of the interaction of gender and occupational status (panels (b) through (f)), along with 95% confidence intervals. In panels (d), (e) and (f), the plots ‘Outcome = 1’ refer to the lowest value of the outcome variable, that is, respondents who strongly disagree with the statements ‘My job offers good prospects for career advancement’ in panel (d), ‘I feel “at home” in this organisation’ in panel (e) and ‘I can also talk to my colleagues about personal problems’ in panel (f), whereas the plots ‘Outcome = 5’ refer to the highest value of the outcome variable, that is, respondents who fully agree with the respective statement.

Table 2. Regression results of refugees’ employment outcomes (Heckman maximum likelihood estimation; probit models; ordered probit models).

Fixed-term employment

The gender gap in fixed-term employment persists after controlling for other factors, as presented in column (2) of . The average marginal effect (AME) for gender indicates that refugee women are 14.3 percentage points more likely than men to have a fixed-term contract (p = 0.012). Occupational status moderates the relationship between gender and fixed-term employment, as also panel (b) of suggests. The gender gap in fixed-term employment is minimal among those employed in elementary or high-skill jobs, but it is statistically significant among those in skilled jobs, putting women at a disadvantage (interaction term for skilled job: AME = 0.212; p = 0.003).

Overqualification

In contrast to our bivariate finding that suggested a difference in overqualification, the marginal effect for gender is not statistically significant in the multivariate analysis (AME = −0.064; p = 0.155; column (3) of ). However, occupational status, specifically in terms of high-skill jobs compared to elementary and skilled jobs, has a moderating influence in that it exacerbates the relationship between gender and overqualification that disadvantages men, as evidenced by panel (c) of (interaction term for high-skill job: AME = −0.184; p < 0.001).

Career prospects

Another picture emerges for career prospects. As column (4) of shows, after controlling for other factors, the coefficient for gender is not statistically significant (coeff. = −0.243; p = 0.482). Whereas occupational status is positively related to reported career prospects (skilled job: coeff. = 0.527; p = 0.011; high-skill job: coeff. = 0.829; p = 0.001), it has no statistically significant moderating impact on the relationship between gender and career prospects (interaction term for skilled job: coeff. = 0.336; p = 0.361; high-skill job: coeff. = 0.338; p = 0.409), as also the very similar graphs in panel (d) of suggest.

Feeling at home; talking about problems

The results for the two outcome variables representing social workplace aspects, which are shown in columns (5) and (6) of , again indicate no statistically significant gender differences after controlling for other factors (feeling at home: coeff. = −0.482; p = 0.172; talking about problems: coeff. = −0.413; p = 0.246). However, occupational status has a moderating impact. Compared to elementary and skilled jobs, where women are disadvantaged, working in a high-skill job reverses the (statistically non-significant) gender gaps in both social aspects to the disadvantage of men (interaction terms for high-skill job for feeling at home: coeff. = 0.799; p = 0.044; talking about problems: coeff. = 0.874; p = 0.031). This indicates that women benefit disproportionately from working in high-skill jobs in terms of social aspects. As also illustrated in panels (e) and (f) of , the gender gaps that disadvantage women in elementary jobs are smaller for those in skilled jobs and reversed for those in high-skill jobs.

Discussion

This study revealed several differences between refugee women and refugee men in employment outcomes, providing a more nuanced perspective than previous research, especially regarding ‘softer’ aspects. Furthermore, it highlights how occupational status influences gender gaps in refugees’ employment outcomes.

Firstly, we found that refugee women receive lower pay than men. Gender pay gaps to the disadvantage of women are a well-known global phenomenon, and our findings are consistent with those by Tran and Lara-García (Citation2020) as well as Minor and Cameo (Citation2018) for the United States plus Bevelander and Pendakur (Citation2014) for Canada and Sweden. Given that Austria has one of the highest gender pay gaps in Europe, standing at 18.4 percent in 2022 (Eurostat Citation2024c), it also does not come as a surprise that we found a significant gender pay gap for refugees in Austria.Footnote2 The fact that, at 30.8 percent (equivalent to 4.76 euro per hour), the pay gap for refugees is substantially larger than that for the non-refugee population in Austria reflects the particular challenges faced by refugee women in the Austrian labour market, as also shown by the qualitative study of Schiestl, Kittel, and Bollerhoff (Citation2021). The gender pay gap is similarly large across all three occupational status groups when we control for other influencing factors, suggesting that employers do not discriminate against women in this regard.

Secondly, the gender disparity in fixed-term employment, which persists after accounting for the control variables, is the most pronounced among the employment outcomes considered in this study. Almost every second woman, 45.7 percent, works on a fixed-term basis, compared to 35.8 percent of men. This result stands in stark contrast to the Austrian population as a whole, where the gender gap is much smaller and also reversed, with 8.3 percent of women and 8.8 percent of men holding fixed-term contracts during the first quarter of 2022 (Statistik Austria Citation2022). Refugees’ occupational status is also important here as the disadvantage for women is more pronounced in skilled jobs compared to elementary or high-skill jobs.

As with pay, these findings suggest that refugees, and in particular refugee women, face additional barriers to employment, so that they may be more likely to accept temporary positions as a means of entering the job market and gaining work experience. Employers may prefer hiring refugees, especially refugee women, on a temporary basis to minimise perceived risks (Lundborg and Skedinger Citation2016). Other job positions may be temporary because of funding constraints or a (supposedly) transient need, such as in state-funded refugee integration projects involving child-care workers and learning supervisors who share the same ethnic background as the refugee population they are working with. However, our data do not permit conclusions about the reasons behind fixed-term contracts, also in terms of refugees’ voluntariness, or about how satisfied the respondents are with them. Likewise, while a glance at data from previous years of our survey suggests that refugee women were less likely than men to transition from fixed-term to permanent employment, particularly those in skilled and high-skill jobs,Footnote3 the small sample size limits insights into trajectories over time. Thus, given that permanent employment is crucial because fixed-term contracts can contribute to refugees’ sense of precarity (Jackson and Bauder Citation2014) and may be more of a trap than a stepping-stone into stable, high-quality employment (Lumley-Sapanski Citation2021), future research is needed that explores the reasons behind fixed-term employment and refugees’ trajectories in a larger time span to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of this important finding.

Thirdly, contrary to the gender disparities observed in pay and fixed-term employment to the detriment of women, we found that men face a disadvantage regarding overqualification. While the effect of gender is not statistically significant when accounting for the control variables, the gender gap indeed is significantly larger in high-skill jobs. Reasons for this finding could include that women, when searching for high-skill jobs, may be particularly focused on ensuring that job requirements match their qualifications. The finding by Jestl and Tverdostup (Citation2023) that refugee women in Austria took longer to find an entry job than men supports this argument. Additionally, men may have found a high-skill job but been assigned work tasks below their level of skills and work experience, or their (subjectively assessed) higher level of skills and work experience compared to women may have contributed to higher perceived overqualification. However, such possible differences are not reflected in career prospects, which are perceived equally by women and men as well as across all occupational status groups.

Fourthly, regarding the social aspects of feeling at home in the workplace and being able to talk to colleagues about personal problems, the finding that gaps to the disadvantage of women in elementary jobs reverse into a disadvantage for men in high-skill jobs is interesting. One reason could be that the social environment at the workplace welcomes and integrates higher-qualified women to a greater extent, for example out of solidarity with potentially disadvantaged women, or because they have special expertise that leads to increased cooperation and consequently social integration. Another reason could be that refugee women only manage to land high-skill jobs if they have strong social skills and networks, along with appropriate gender norms, which also help them in socialising with their colleagues.

To summarise, while we have identified gender gaps in terms of pay and particularly fixed-term employment, there is no evidence for differences in the four other indicators of employment outcomes after controlling for other factors. Occupational status structures gender gaps in such a way that, in terms of fixed-term employment, overqualification and social aspects in the workplace, they shift disproportionally in favour of refugee women in high-skill jobs. However, these findings also underscore a distinct inequality across the occupational status groups in that those in elementary jobs are not only facing worse working conditions in terms of pay, fixed-term employment, overqualification and career prospects than their counterparts in skilled and especially high-skill jobs, but also in terms of the social aspects – and this is even stronger for refugee women as compared to men.

We see the following limitations to our research, which also suggest directions for future research. Specifically, selectivity into employment may be an issue since refugees, and particularly refugee women, face strong individual and structural barriers to being active in the labour market and securing paid employment (Jestl and Tverdostup Citation2023; Schiestl, Kittel, and Bollerhoff Citation2021). However, our robustness checks, where we conducted regression analyses with and without Heckman correction, as well as separately for women and men, showed that selection bias was only an issue for the pay model. Therefore, we estimated this model using Heckman maximum likelihood estimation. Although we consider our results to be valid and reliable in this regard, potential selectivity can never be entirely ruled out. Hence, further research aiming to replicate our findings is necessary. Moreover, the nuanced picture of refugees’ employment outcomes, using six indicators, comes with a certain complexity. In order to keep the complexity manageable, we have not addressed the relationships between the indicators, such as between fixed-term employment and pay (Minor and Cameo Citation2018) or trade-offs among the outcomes (Ortlieb and Weiss Citation2020). Thus, future research should examine such relationships in more detail.

Our study has several policy implications. Firstly, whereas refugees are often portrayed in public opinion and policy debates as helpless victims, shady criminals or a burden on society (Pandir Citation2020; Rheindorf and Wodak Citation2018), and refugee women as passive and unemancipated appendages to their husbands (Ghorashi Citation2021), our study adds a more nuanced picture of working refugees that proffers a reframing of the debate. The finding that many refugees, including women, work in skilled and high-skill jobs and thus make important contributions to the country’s economy and welfare system could counteract prevailing xenophobia and enable more effective tailoring of support programmes that focus on refugees’ capacity and agency rather than deficits. Secondly, as our study revealed marked gender gaps regarding pay, fixed-term employment and overqualification, measures are needed to reduce these inequalities. For instance, integration counsellors should raise awareness among refugee women about potential pay discrimination and empower them to request greater transparency from their employers regarding their pay systems (Rubery and Grimshaw Citation2015), including the criteria for pay increases. To alleviate the insecurity stemming from fixed-term employment contracts, state programmes could offer transitional employment opportunities to those who do not secure employment immediately after the termination of their contracts. To mitigate the issue of overqualification among refugee men, improved systems for recognising their professional skills and providing higher-level language courses when language barriers hinder refugees from utilising their skills in the workplace will be beneficial. Job agency officers involved in job placement should be cautious to ensure that placement efforts do not compromise critical issues like fair pay, permanent employment contracts and adequate opportunity to utilise one’s skills.

Lastly, our finding that refugee women benefit disproportionately from working in high-skill jobs suggests that efforts in searching for such jobs pay off. Thus, instead of aiming to quickly place refugees in the job market and focusing on low-skill jobs (Otmani Citation2023), integration programmes should provide refugee women with access to high-level training and development while motivating them to apply for high-skill jobs. This is all the more important from a sustainability perspective, as previous research has shown that the search for the first job in the new country has long-term consequences for refugees’ employment trajectories (Hernes et al. Citation2022; Jestl and Tverdostup Citation2023).

Conclusion

Going beyond previous research on the labour market integration of refugees, this study has revealed gender disparities in a variety of employment outcomes between refugee women and men. Occupational status is a crucial factor, as especially women benefit from high-skill jobs. Nevertheless, critical concerns arise from the prevalence of fixed-term employment contracts and the particularly poor employment outcomes of refugee women working in elementary jobs, who are already underprivileged in several respects. Future research and policies should therefore prioritise addressing these critical issues in order to curb gender inequalities among refugees.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (123.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. They gratefully acknowledge funding by the Austrian Federal Chancellery, the State of Vorarlberg, the Public Employment Service Austria and the City of Graz for data collection, as well as financial support by the University of Graz for Open Access publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Individuals aged 18–64 years who received a positive decision on their asylum applications (first instance or final decisions) between 2012 and 2021 in European Union 27 Member States (2020) plus UK, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland and UK (2012–2019).

2 Caution is necessary in making such comparisons because other gender pay gap statistics account for different influencing variables and samples. Our study only considered individuals employed for at least 8 hours per week and regardless of firm size, whereas official statistics published in Eurostat (Citation2024c) include all workers in firms with 10 or more employees.

3 Data were gathered between March and May 2019 (2403 respondents), and between October and December 2020 (3650 respondents). We consider a sample of 60 respondents who were in temporary employment in 2019, and 97 respondents who were also in temporary employment in 2020 to examine the transitions of refugees from fixed-term employment contracts to permanent, fixed-term or no employment between 2019 and 2022.

References

- Ager, A., and A. Strang. 2008. “Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Refugee Studies 21 (2): 166–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen016.

- Albrecht, C., M. Hofbauer Pérez, and T. Stitteneder. 2021. “The Integration Challenges of Female Refugees and Migrants: Where Do We Stand?” CESifo Forum 22 (2): 39–46.

- Andersson Joona, P., and N. Datta Gupta. 2022. “Labour Market Integration of FRY Refugees in Sweden vs. Denmark.” International Migration 61 (2): 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.13007.

- Bakker, L., J. Dagevos, and G. Engbersen. 2017. “Explaining the Refugee Gap: A Longitudinal Study on Labour Market Participation of Refugees in the Netherlands.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (11): 1775–1791. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1251835.

- Baumgartner, P., M. Palinkas, and V. Bilger. 2023. Arbeitsmarktintegration geflüchteter Frauen in Österreich. Ergebnisse der fünften Welle des FIMAS-Surveys: FIMAS + Frauen. Vienna: ICMPD.

- Becker, G. S. 1985. “Human Capital, Effort, and the Sexual Division of Labor.” Journal of Labor Economics 3 (1/Part 2): S33–S58. https://doi.org/10.1086/298075

- Bevelander, P., and R. Pendakur. 2014. “The Labour Market Integration of Refugee and Family Reunion Immigrants: A Comparison of Outcomes in Canada and Sweden.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (5): 689–709. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.849569.

- Bloch, A. 2008. “Refugees in the UK Labour Market: The Conflict between Economic Integration and Policy-led Labour Market Restriction.” Journal of Social Policy 37 (1): 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004727940700147X.

- BMI. 2024. Jahresstatistiken Asylwesen. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.bmi.gv.at/301/Statistiken.

- Bratsberg, B., O. Raaum, and K. Røed. 2017. “Immigrant Labor Market Integration across Admission Classes.” In Nordic Economic Policy Review: Labour Market Integration in the Nordic Countries, edited by B. Bratsberg, O. Raaum, K. Røed, and O. Åslund, 17–54. Copenhagen: Nordisk Ministerråd.

- Brell, C., C. Dustmann, and I. Preston. 2020. “The Labor Market Integration of Refugee Migrants in High-income Countries.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 34 (1): 94–121. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.34.1.94.

- Brücker, H., Y. Kosyakova, and E. Schuß. 2020. Fünf Jahre seit der Fluchtmigration 2015: Integration in Arbeitsmarkt und Bildungssystem macht weitere Fortschritte. IAB-Kurzbericht No. 4/2020, Nürnberg.

- Brücker, H., Y. Kosyakova, and E. Vallizadeh. 2020. “Has There Been a “Refugee Crisis”? New Insights on the Recent Refugee Arrivals in Germany and Their Integration Prospects” Soziale Welt 71 (1-2): 24–53. https://doi.org/10.5771/0038-6073-2020-1-2-24.

- Brynin, M., and A. Güveli. 2012. “Understanding the Ethnic Pay Gap in Britain.” Work, Employment and Society 26 (4): 574–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017012445095.

- Bullinger, B., A. Schneider, and J.-P. Gond. 2023. “Destigmatization through Visualization: Striving to Redefine Refugee Workers’ Worth.” Organization Studies 44 (5): 739–763. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406221116597.

- Cheung, H. K., L. E. Baranik, D. Burrows, and L. Ashburn-Nardo. 2022. “Hiring Discrimination against Refugees: Examining the Mediating Role of Symbolic and Realistic Threat.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 138:103765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2022.103765.

- Cheung, S. Y., and J. Phillimore. 2017. “Gender and Refugee Integration: A Quantitative Analysis of Integration and Social Policy Outcomes.” Journal of Social Policy 46 (2): 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279416000775.

- Colic-Peisker, V., and F. Tilbury. 2006. “Employment Niches for Recent Refugees: Segmented Labour Market in Twenty-first Century Australia.” Journal of Refugee Studies 19 (2): 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fej016.

- Deitch, E. A., A. Barsky, R. M. Butz, S. Chan, A. P. Brief, and J. C. Bradley. 2003. “Subtle yet Significant: The Existence and Impact of Everyday Racial Discrimination in the Workplace.” Human Relations 56 (11): 1299–1324. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267035611002.

- Delaporte, I., and M. Piracha. 2018. “Integration of Humanitarian Migrants into the Host Country Labour Market: Evidence from Australia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (15): 2480–2505. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1429901.

- De Vroome, T., and F. van Tubergen. 2010. “The Employment Experience of Refugees in the Netherlands.” International Migration Review 44 (2): 376–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2010.00810.x

- Diedrich, A., and A. Styhre. 2013. “Constructing the Employable Immigrant: The Uses of Validation Practices in Sweden.” Ephemera 13 (4): 759–783.

- Doeringer, P. B., and M. J. Piore. 1971. Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis. Lexington, MA: Heath.

- Eggenhofer-Rehart, P. M., M. Latzke, K. Pernkopf, D. Zellhofer, W. Mayrhofer, and J. Steyrer. 2018. “Refugees’ Career Capital Welcome? Afghan and Syrian Refugee Job Seekers in Austria.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.01.004.

- Eurostat. 2024a. First Instance Decisions and Final Decisions in Appeal or Review on Applications by Citizenship, Age and Sex. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/MIGR_ASYDCFSTA__custom_5036762/default/table?lang=en.

- Eurostat. 2024b. Asylum Applicants by Type, Citizenship, Age and Sex - Annual Aggregated Data. Available at: ttps://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/migr_asyappctza/default/bar?lang=en. Accessed April 8, 2024.

- Eurostat. 2024c. Gender Pay Gap in Unadjusted Form. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/SDG_05_20/default/table?lang=en.

- Expertenrat für Integration. 2023. Integrationsbericht 2022. Vienna.

- Fasani, F., T. Frattini, and L. Minale. 2022. “(The Struggle for) Refugee Integration into the Labour Market: Evidence from Europe.” Journal of Economic Geography 22 (2): 351–393. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbab011.

- Fozdar, F., and S. Torezani. 2008. “Discrimination and Well-Being: Perceptions of Refugees in Western Australia.” International Migration Review 42 (1): 30–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00113.x.

- Ghorashi, H. 2021. “Normalising Power and Engaged Narrative Methodology: Refugee Women, the Forgotten Category in the Public Discourse.” Feminist Review 129 (1): 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/01417789211041089

- Giri, A. 2018. “From Refuge to Riches? An Analysis of Refugees’ Wage Assimilation in the United States.” International Migration Review 52 (1): 125–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918318776318.

- Granovetter, M. 1974. Getting a Job: A Study of Contacts and Careers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Grimshaw, D., C. Fagan, G. Hebson, and I. Tavora. 2017. “A New Labour Market Segmentation Approach for Analysing Inequalities: Introduction and Overview.” In Making Work More Equal: A New Labour Market Segmentation Approach, edited by D. Grimshaw, C. Fagan, G. Hebson, and I. Tavora, 1–32. Manchester: Manchester University Press. https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526125972.00007.

- Habash, D., and N. Omata. 2023. “The ‘Private’ Sphere of Integration? Reconfiguring Gender Roles within Syrian Refugee Families in the UK.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 24 (3): 969–988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-022-00982-x.

- Heckman, J. 1979. “Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error.” Econometrica 47 (1): 153–161. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912352.

- Hernes, V., J. Arendt, P. Andersson Joona, and K. Tronstad. 2022. “Rapid or Long-term Employment? A Scandinavian Comparative Study of Refugee Integration Policies and Employment Outcomes.” Journal of European Public Policy 29 (2): 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1824011.

- Holman, D. 2013. “Job Types and Job Quality in Europe.” Human Relations 66 (4): 475–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712456407.

- Hunt, L. 2008. “Women Asylum Seekers and Refugees: Opportunities, Constraints and the Role of Agency.” Social Policy and Society 7 (3): 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746408004260.

- Jackson, S., and H. Bauder. 2014. “Neither Temporary, nor Permanent: The Precarious Employment Experiences of Refugee Claimants in Canada.” Journal of Refugee Studies 27 (3): 360–381. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fet048.

- Jestl, S., M. Landesmann, S. Leitner, and B. Wanek-Zajic. 2022. “Trajectories of Employment Gaps of Refugees and other Migrants: Evidence from Austria.” Population Research and Policy Review 41 (2): 609–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-021-09666-3.

- Jestl, S., and M. Tverdostup. 2023. The Labour Market Entry and Integration of Refugees and other Migrants in Austria. Wiiw Working Paper No. 231.

- Knappert, L., A. Kornau, and M. Figengül. 2018. “Refugees’ Exclusion at Work and the Intersection with Gender: Insights from the Turkish-Syrian Border.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 62–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.11.002.

- Kone, Z., I. Ruiz, and C. Vargas-Silva. 2019. Refugees and the UK Labour Market. Oxford: Compass Report.

- Kostenko, V. V. 2019. “Gender Attitudes of Muslim Migrants Compared to Europeans and Public in Sending Societies: A Multilevel Approach.” In Muslim Minorities and the Refugee Crisis in Europe, edited by K. Górak-Sosnowska, M. Pachocka and J. Misiuna, 37–50. Warsaw: SGH Publishing House.

- Koyama, J. P. 2015. “Constructing Gender: Refugee Women Working in the United States.” Journal of Refugee Studies 28 (2): 258–275. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feu026.

- Kühne, S., J. Jacobsen, and M. Kroh. 2019. “Sampling in Times of High Immigration: The Survey Process of the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees.” Survey Methods: Insights from the Field. https://doi.org/10.13094/SMIF-2019-00005. https://surveyinsights.org/?p=11416.

- Lamba, N. K. 2003. “The Employment Experiences of Canadian Refugees: Measuring the Impact of Human and Social Capital on Quality of Employment.” Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie 40 (1): 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-618X.2003.tb00235.x.

- Lee, E. S., B. Szkudlarek, D. C. Nguyen, and L. Nardon. 2020. “Unveiling the Canvas Ceiling: A Multidisciplinary Literature Review of Refugee Employment and Workforce Integration.” International Journal of Management Reviews 22 (2): 193–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12222.

- Leitner, S. M., and M. Landesmann. 2020. Refugees’ Integration into the Austrian Labour Market: Dynamics of Occupational Mobility and Job-Skills Mismatch. Wiiw Working Paper No. 188.

- Liebig, T., and K. R. Tronstad. 2018. “Triple Disadvantage? A First Overview of the Integration of Refugee Woman.” OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers. Paris: OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/1815199X.

- Lumley-Sapanski, A. 2021. “The Survival Job Trap: Explaining Refugee Employment Outcomes in Chicago and the Contributing Factors.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (2): 2093–2123. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez092.

- Lundborg, P., and P. Skedinger. 2016. “Employer Attitudes towards Refugee Immigrants: Findings from a Swedish Survey.” International Labour Review 155 (2): 315–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12026.

- Mayrhofer, W., J. Briscoe, M. Dickmann, D. T. Hall, and E. Parry. 2023. “Careers: What They Are and How to Look at Them.” In Understanding Careers around the Globe, edited by J. Briscoe, M. Dickmann, D. Hall, W. Mayrhofer, and E. Parry, 2–8. Cheltenham: Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781035308415.00006.

- Minor, O. M., and M. Cameo. 2018. “A Comparison of Wages by Gender and Region of Origin for Newly Arrived Refugees in the USA.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 19 (3): 813–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-018-0581-1.

- Muñoz de Bustillo, R., E. Fernández-Macías, F. Esteve, and J.-I. Antón. 2011. “E Pluribus Unum? A Critical Survey of Job Quality Indicators.” Socio-Economic Review 9 (3): 447–475. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwr005.

- Ortlieb, T., P. Eggenhofer-Rehart, S. Leitner, R. Hosner, and M. Landesmann. 2020. “Do Austrian Programmes Facilitate Labour Market Integration of Refugees?” International Migration. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12784.

- Ortlieb, R., and L. Knappert. 2023. “Labor Market Integration of Refugees: An Institutional Country-comparative Perspective.” Journal of International Management 29 (2): 101016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2023.101016.

- Ortlieb, R., and S. Weiss. 2020. “Job Quality of Refugees in Austria: Trade-Offs Between Multiple Workplace Characteristics.” German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift für Personalforschung 34 (4): 418–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002220914224.

- Otmani, I. 2023. “Towards a ‘Low Ambition Equilibrium’: Managing Refugee Aspirations during the Integration Process in Switzerland.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50:854–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2235902.

- Pandir, M. 2020. “Media Portrayals of Refugees and their Effects on Social Conflict and Social Cohesion.” Journal of International Affairs 25 (1): 99–120.

- Parlamentsdirektion Österreich. 2023. Belastungen des Budgets durch die Auswirkungen der Migrationswelle 2022. Vienna.

- Piore, M. J. 1979. Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor and Industrial Societies. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Rheindorf, M., and R. Wodak. 2018. “Borders, Fences, and Limits – Protecting Austria from Refugees: Metadiscursive Negotiation of Meaning in the Current Refugee Crisis.” Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 16 (1–2): 15–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1302032.

- Rubery, J., and D. Grimshaw. 2015. “The 40-Year Pursuit of Equal Pay: A Case of Constantly Moving Goalposts.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 39 (2): 319–343. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/beu053.

- Salikutluk, Z., and K. Menke. 2021. “Gendered Integration? How Recently Arrived Male and Female Refugees Fare on the German Labour Market.” Journal of Family Research 33 (2): 284–321. https://doi.org/10.20377/jfr-474.

- Schiestl, D. W., B. Kittel, and M. Ibáñez Bollerhoff. 2021. “Conquering the Labour Market: The Socioeconomic Enablement of Refugee Women in Austria.” Comparative Migration Studies 9:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-021-00267-9.

- Schmidt, K., J. Jacobsen, and M. Krieger. 2020. “Social Integration of Refugees is Improving.” DIW Weekly Report 10 (34): 355–363. https://doi.org/10.18723/diw_dwr:2020-34-3.

- Schultz-Nielsen, M. L. 2017. “Labour Market Integration of Refugees in Denmark.” In Nordic Economic Policy Review: Labour Market Integration in the Nordic Countries, edited by B. Bratsberg, O. Raaum, K. Røed, and O. Åslund, 55–90. Copenhagen: Nordisk Ministerråd.

- Senthanar, S., E. MacEachen, S. Premji, and P. Bigelow. 2021a. “Employment Integration Experiences of Syrian Refugee Women Arriving through Canada’s Varied Refugee Protection Programmes.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (3): 575–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1733945.

- Senthanar, S., E. MacEachen, S. Premji, and P. Bigelow. 2021b. “Entrepreneurial Experiences of Syrian Refugee Women in Canada: A Feminist Grounded Qualitative Study.” Small Business Economics 57:835–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00385-1.

- Smyth, G., and H. Kum. 2010. “'When They don't Use it They will Lose it': Professionals, Deprofessionalization and Reprofessionalization: the Case of Refugee Teachers in Scotland” Journal of Refugee Studies 23 (4): 503–522. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feq041.

- Statistik Austria. 2022. Arbeitsmarktstatistik. Mikrozensus-Arbeitskräfteerhebung. Vienna.

- Tomlinson, F. 2010. “Marking Difference and Negotiating Belonging: Refugee Women, Volunteering and Employment.” Gender, Work & Organization 17 (3): 278–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00399.x.

- Tran, V. C., and F. Lara-García. 2020. “A New Beginning: Early Refugee Integration in the United States.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 6 (3): 117–149. https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2020.6.3.06.

- Verwiebe, R., B. Kittel, F. Dellinger, C. Liebhart, D. Schiestl, R. Haindorfer, and B. Liedl. 2019. “Finding your Way into Employment against All Odds? Successful Job Search of Refugees in Austria.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (9): 1401–1418. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1552826.

- Wehrle, K., M. Kira, and U. C. Klehe. 2019. “Putting Career Construction into Context: Career Adaptability among Refugees.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 111:107–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.08.007.