ABSTRACT

The temporal tensions experienced by refugees in European host societies result from a sharp disruption between past and present, as well as from the unpredictability of the future. The prolonged violence experienced in countries of origin and the tactic of time used in bureaucratic forms of domination in countries of destination through complex and lengthy procedures contribute to the chaos and precarity of the refugee experience. Yet how this experience changes in the longer term has received limited attention in the literature. This article draws on one year of fieldwork using interviews, participatory photography, and film with families who have been reunited for one or more years in Manchester and Glasgow, UK, to understand the transformations that occur after the uncertainty of waiting during asylum and family reunion applications has been ‘resolved’. Following the key themes identified in our analysis, we look at challenges that continue or emerge, temporal possibilities that arise, and people’s strategies to balance both, as well as at how these experiences are manifested in and through the body. We found that following key indeterminate periods of waiting, temporal tensions coexist with the capacity to start thinking about the future, embodying a more active experience of time.

Introduction

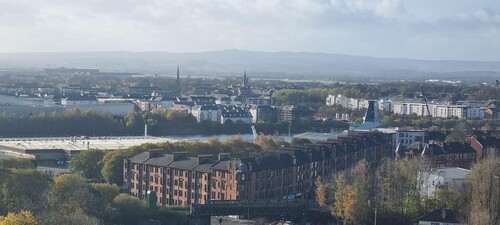

In Sudan, my balcony … Most airplanes pass by me to reach the airport of Khartoum. Here in Glasgow my balcony is faced to Glasgow airport, so that it is like my balcony in Sudan ().

While the relationship between time and displacement has been explored in the literature, research that looks at how the experience of time changes after the major temporal tensions embedded in the process of asylum and family reunion applications have been ‘resolved’, is only limited. Drawing on one year of fieldwork using interviews, participatory photography, and film in Manchester and Glasgow, UK, this article addresses this gap by focusing on the life period that follows the first year after family reunion – one that could on the surface be understood as characterised by stability and permanency. Following a conceptual discussion of time and a description of the methods used in the study, the next sections will present our findings by looking at the challenges that emerge with changes in the experience of time, temporal possibilities that unfold, and people’s strategies to balance both, before concluding.

We focus our analysis of challenges on bodily manifestations of those experiences, since pain, suffering and the body emerged as key themes in the narratives of challenges that we collected amongst refugee families. An emphasis on the role of the body in experiencing and communicating what Coker (Citation2004) named ‘disruption-as-illness’ reinforces the need for more social research in this area and its potential in assisting support providers, including healthcare, through better understandings of these narratives.

Waiting and temporal control

Distinguishing between human time (the experience of the passage of time) and clock or calendar time (scientifically measured durational time), scholars have shown how the latter is used to exercise power and is the prerequisite for the acquisition of rights (Anderson Citation2020; Cohen Citation2018; Stronks Citation2022). The experience of waiting in administrative processes can be seen as a form of ‘time theft’, where human time is appropriated and, consequently, rights are denied, in what Cohen (Citation2018) has defined as ‘temporal injustices.’ In the migration experience, ‘temporariness’ is thus used as a form of legal control, leading to a state of prolonged liminality rather than a linear progression towards ‘permanency’ amongst migrants (Anderson Citation2020; Stronks Citation2022).

The continuous experience of waiting amongst asylum seekers and refugees in European countries of destination is therefore linked to unequal power relations embedded in bureaucratic domination, a form of control that maintains their marginality and compliance. The slowness and uncertainty of both asylum and family reunion processes are, in countries like the UK, highly exaggerated, acting as a tool of governmentality that has severe material, emotional, and physical consequences for refugees (Fee Citation2022; Griffiths Citation2014). As Fee (Citation2002) contends, refugees are forced to perform an ‘endurance test’ by integrating a programme that, while in principle providing a pathway to their protection, is unreliable and expects them to wait in a compliant way, accept new forms of precarity, and renounce ownership of their time, ultimately representing them as less deserving.

This has been recently aggravated by the UK’s withdrawal from the EU and the consequent legal and operational vacuum in migration and asylum matters, as well as by the 2022 Nationality and Borders Act, which introduced a ‘two-tier’ system giving differential treatment to asylum seekers entering the UK by regular or irregular routes and reducing the rights of the latter, and the subsequent 2023 Illegal Migration Act, which makes the asylum claims of anyone crossing the channel through ‘irregular’ means declared ‘inadmissible’, with the government intending to detain and remove them (Refugee Council Citation2023). The construction of different categories of ‘foreigners’ or ‘others’ has a temporal language, as they are defined according to the length of permitted stay, temporary or permanent residence, specific time frames for renewing permits or seeking a change in status, and chronological age markers. The tactic of time used in time-limited legal statuses and in the rhythms of lengthy bureaucratic processes produces an impact on the lives of refugees in the UK (Allsopp, Chase, and Mitchell Citation2015). Time is therefore not a detached dimension of social life, but a constitutive element of people’s experience (Cwerner Citation2010; Gray Citation2011).

Similarly, family reunion processes in the UK are caught between the state’s exercise of control and bordering practice, and individual human rights. While several declarations and conventions at international level state the need to protect family units (such as the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 1951 Refugee Convention or the European Convention on Human Rights, which was integrated in the UK Human Rights Act of 1998), family reunion application processes and a successful outcome are hindered by a number of complex requirements at different stages. Moreover, certain conditions imposed are based on problematic conceptions, such as that of the ‘nuclear’ family or ‘proof’ of family relationships, which inform practices of inclusion and exclusion by making decisions about who is worthy of protection (Welfens and Bonjour Citation2021).

An inspection of the Home Office’s management of family reunion applications between January and September 2022 concluded that performance has deteriorated and waiting times for applicants have increased since 2019 (Neal Citation2023). One of the reasons highlighted for the delay was the redeployment of staff to work on the Homes for Ukraine scheme, a measure that the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI) criticised due to the detrimental effect on vulnerable individuals who were victims of earlier crises. Of the 7970 applications for family reunion submitted between 1 January 2022 and 30 September 2022, 7043 were still awaiting a decision on 30 September 2022, of which more than half (3629) had been submitted between January and May (Neal Citation2023).

After an initial disorientation and ambivalence that comes with family reunion, there is often the need to ‘make up for lost time’ (Suårez-Orozco, Todorova, and Louie Citation2002, 640) – what participants in this study refer to as a renewed sense of ‘hope’ and ‘a new beginning’. Old rhythms and new routines, imposed in part by the regulations described above, but also actively incorporated in the everyday as sites of resistance and possibility, are juxtaposed in the experience of refugees and their families. However, also this takes long to achieve, with families who have been reunited for one year or more maintaining that only now they are able to finally ‘start everything from zero again and build a nice life and future.’ Changes in the experience of time after the precarious waiting for refugee status and family reunification has been resolved will be the focus of the discussion in this article.

Time and the body

Time is experienced in the body. While the relationship between displacement and narratives of the body has been considerably explored in relation to memory (e.g. Becker, Beyene, and Ken Citation2000b; Salih Citation2017), the way time and the body interplay in the lived experience of refugees has not received the same attention in the literature. In this article, we will refer to narratives of bodily pain and suffering – the ‘illness talk’ explored by Coker (Citation2004) as a way for people to make sense of their suffering. These will contribute to understand how a complex experience of time continues to affect the lives of refugees, even after having successfully navigated the temporal hurdles of asylum and family reunion applications. Since such embodied narratives were more often used by participants when sharing the challenges faced by temporal disruptions, we will use an embodied approach mainly when discussing challenges over time, although some of the opportunities and coping strategies explored will also entail descriptions of ritual and bodily activity.

Drawing on the distinction between abstract time – a basic dimension of experience that gives us a sense of orientation – and concrete time – based on daily rhythms and activities that connect situational experiences – Sagbakken, Bregård, and Varvi (Citation2020) identify a series of effects that temporal disruptions produce on refugees’ bodies and wellbeing. The suffering associated with the loss of future direction and a sense of entrapment, disempowerment, unpredictability, and reduced self-worth result from the difficulty in tying the past to the present, and the present to the future, and to differences in the perception and use of time in societies of origin and destination (Kuhlemann Citation2023). Griffiths (Citation2014) advanced an exploration of the relationship between the control and domination that shape asylum application processes and people’s awareness of the need for their bodies to wait ‘quietly’ and ‘patiently’, with little overt political action or protest. Yet the feminisation of this temporal experience, when seen as passive and immobile, has been criticised in feminist literature on mobility, which has called attention to the politics of waiting as active practice (Conlon Citation2011) and to the feminisation of the asylum process as reinforcing inequalities (Hyndman and Wenona Citation2011). Others have challenged the understanding of waiting as passive, empty, and wasted time in the context of asylum seeking, arguing instead for an acknowledgement of its affective, active, and productive dimensions (Rotter Citation2016).

Whereas these processes and relationships have been analysed in relation to the experience of seeking asylum, an investigation of how this experience changes at a later stage of refugee life, once families have been reunited, is still lacking. In this article, we will draw on cases where waiting appears to be over, to distil the complexity that persists in the passage of time. We will do this by centring the analysis on bodily manifestations of what participants refer to as ‘suffering’, but also on how opportunities are found and used, and on the routinised strategies put into place to cope with changes in their temporal experience.

Methodology

This article draws on one year of fieldwork (July 2022–June 2023) in Manchester and Glasgow, involving nine individuals in Manchester and 12 in Glasgow who had been reunited with their family (spouses and/or children) for at least one year (). Whereas our focus here is on the temporal experiences of the 12 men and three women who arrived first to seek asylum (15 sponsors, all now with refugee status and reunited with family), we add some insights from six spouses (all women) who arrived later through family reunion. This allows us to shed some light on the perspective of those for whom the time of migration and that of family reunion occur simultaneously. Of the 15 sponsors, 12 were joined by a spouse and children, two men only by a spouse, and one woman only by her children.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants.

Five families (two in Manchester, and three in Glasgow) formed a core group of participants, who we spent time with, mainly in their homes and through walks in their surroundings, over the year. Other individual participants were interviewed once. Participants were recruited through our project partner – Together Now – who supports refugee family reunion across the UK and established the first contact with families they had supported in the last few years, advertising the study. Manchester and Glasgow were chosen as fieldsites due to Together Now having the greatest concentration of supported families in these locations, and because they cover the different statutory support systems for both England and Scotland. The final selection of participants resulted from people’s availability and interest in participating. A note of caution should be made here about their educated background, which is not necessarily representative of the refugee population but rather indicative of the fact that those with a better understanding of research were more likely willing to contribute. Likewise, their relatively short length of stay in the UK has to do with data availability, since family reunion cases supported by Together Now until 2019 were more difficult to reach due to the use of different recording and referral systems. Recruitment was open to all nationalities, so that the overrepresentation of the Sudanese group is random rather than purposeful.

Our methodological approach was ethnographic in nature. It included regular visits to Manchester and Glasgow throughout the year and several encounters with the core group of participants on different occasions. Although children were often present, they were not involved as participants in the study. We also adopted a participatory approach at different levels. First, the families we worked with more closely took part in a participatory photography activity at an early stage of the research, for which they were given cameras and asked to capture images of themes they considered important in their lives. A selection (ranging between 5 and 30 per individual) of the photographs taken was then discussed separately with each family, and a total of 24 photos were printed on large boards and formed part of the material to be publicly exhibited. Exhibitions have so far taken place at the university of East Anglia in March 2023, the Central Library of Manchester between October–December 2023, and online. This visual approach allowed participants to share experiences and emotions more freely and enabled insightful reflections on the experience of being active participants in the research, as well as a closer relationship between researchers and participants. Second, the project included the production of a documentary with four families (who demonstrated interest in being involved), for which the script was co-written by participants, the film director, and us as researchers. Finally, the research team included one of us with lived experience, which was key in maintaining representation of those with a refugee background and act as a resource in reviewing methods and engaging the community in the process. It also helped overcoming barriers when Arabic was spoken as a first language. For other languages, a community interpreter was recruited when needed.

Our methods also included semi-structured interviews with all participants and one final reflective workshop in each location, where emerging themes were collaboratively discussed, and participants were able to share reflections on their experience of participating in the project, including with a representative of Together Now.Footnote1

Issues around anonymity were thoroughly discussed with participants at different stages of the project. While in the oral material collected, the use of pseudonyms was easily agreed, it was especially important to ensure that everyone involved in the production of visual and audio-visual material understood the problems involved in their anonymisation, but that their desire to be seen or heard, when that was the case, was also respected. These discussions were complex, with some participants choosing the use of pseudonyms when authoring the photos intended for display in the public domain yet insisting on the use of images in which they appeared, and others deciding against the use of identifiable images but choosing to author their photos with their real names. For the purpose of this article, all participants have been anonymised. Images that are accompanied by their real names in the public and online exhibitions were not used here, and while the pseudonyms with which they author the photos we use in this article were respected, other parts of these narrative are under a different pseudonym when those images identify them physically. We were also cautious when using narratives that are reproduced in the film, especially in cases where people chose to be physically identifiable when narrating them. We therefore also gave these participants a different pseudonym in other parts of their narratives. All participants except two chose their own pseudonyms and have made decisions about information they wanted to omit, so that, for example, only images related to opportunities and strategies, rather than challenges and suffering, were shared. Some of these images are used in this article when discussing such possibilities and strategies, in order to present participants’ own views as visually expressed by them.

Due to these complex ethical decisions resulting in some participants having more than one pseudonym, and to the importance of not compromising their safety, we give an overview of their demographic characteristics as a group rather than individually (). Similarly, for most of the article, we do not distinguish between data collected in Glasgow or Manchester, as we did not observe significant differences in people’s experience of time through tensions, possibilities, or strategies.

Challenges over time: what changes one-year post-reunion?

The asynchronicity between what Anderson (Citation2020) named the ordinary temporalities that unfold in life, such as children growing older, and the requirements and complexities that extend immigration-related administrative processes into a prolonged state of liminality and waiting, have profound consequences for those who experience it.

Family reunion can have a positive effect in this deeply destabilising asynchronicity. Although this article is mainly concerned with the period that follows the first year post-reunion, it is important to mention the pre-reunion experience and that of reunion itself in order to understand changes. Here we are mostly interested in the journey of those whose waiting occurred in the UK. All sponsors described family reunion as the happiest moment in their lives and the start of a period when a sense of ease finally occurs. Most referred to it as a turning point when the present becomes more meaningful and some sense of control over the future is acquired through the capacity of being able to start making plans. Malika, a Sudanese woman who first fled to the UK without her children, describes the pre-reunion period as one associated with a pointless life and a sick body:

The first days here … it was hard. I was imagining that my children would come immediately after my arrival, but it didn’t happen. I went crazy … I didn’t have anything, not even a phone … When they weren’t here, I became sick … blood pressure … It was the first time I was far from them. I have a special relationship with them, so I felt that my life was pointless. I was in my room for weeks, not talking to anyone … I started to have high blood pressure … I stayed at hospital … The doctor told me it’s because I’m stressed.

For some, the physical and emotional hardships of the long journey to the UK were the first cause of bodily pain and ills that persist to this day. As Khaled, who left Sudan in 2018, recounts, ‘it was very difficult. I was weak … I was really tired, so I looked very weak. People would think that if I didn’t get help, I might die.’ Upon arrival, the experience of isolation had additional severe effects on the body. Yas, who had undergone cancer surgery in Iran, describes her body as ‘tired and weak’ and her mental health as ‘very, very bad’ for the first two years after arrival in the UK. She refers to a sense of loneliness and ‘estrangement’ (ghareeba, in Farsi) as particularly painful before her husband and son joined her two years after her arrival in 2019.

Notwithstanding the renewed meaning of life and the capacity to start thinking about the future that follow the indeterminate and tense periods of waiting before family reunion, the bodily effects of separation and of the stress and trauma experienced in the country of origin, during the journey, and upon arrival in the UK, continue long after family reunion has been completed. As Aminy, who left Afghanistan in 2020, explains,

Because of the stress and trauma that I was … I was sick, and this left side of my arm is always painful, still … During the night, when I’m sleeping, the left side is too heavy. [It started] last year, before my family came … The doctors say that it’s the stress because there’s no injury.

In addition to the enduring effects of the tensions experienced in countries of origin and upon arrival in the UK, new temporal challenges also emerge with the arrival of families following long periods of separation. Some participants assert facing difficulties in their relationships and refer to family members ‘changing personality’ during the years apart and ‘rejecting’ each other upon reunion. As others have found in different migratory contexts (e.g. Fresnoza-Flot Citation2014; Suårez-Orozco, Todorova, and Louie Citation2002), the emotional distance created by increased separation time can complicate the future development of these relationships.

Applying the concept of temporal structure as used by Aybec (Citation2015) in relation to transnational relationships and marriage migration can be useful to understand such tensions, especially when the timing, sequencing, spacing and duration of other events that emerge with family reunion contribute to destabilise people’s temporal experience. Additional responsibilities in relation to finances, for example, including the need to repay loans used in the family reunion application, as well as a lack of understanding of service provision by the newly arrived and the need for support in accessing it, inappropriate accommodation and children’s challenges at school contribute to increasing tension with reunion.

In cases of illness of newly arrived relatives, the new challenges – more directly associated with the body – destabilise temporal structure in particularly complex ways, as testified by Saman. His wife, who joined him one year and three months after his arrival from Iran, was in pain for nine months before she was diagnosed with a lumbar disc problem. Saman describes his experience of post-reunion as a period in which time continues to be on hold, as they faced the long waiting times of the National Health Service and he acquired further caring responsibilities, being unable to look for work or plan for the future. Yet rather than passive waiting time, this is a demanding period of activity and caring, the active and affective waiting that has been defined in theories of waiting (Bissell Citation2007; Rotter Citation2016).

Children’s experiences of illness with displacement are another motive for increased concern, depression and what some describe as a feeling of extreme ‘fatigue’ that follows reunion. As Malika explains,

It was difficult for [my daughter] at the beginning. She was depressed and then I became depressed with her … Their adaptation … I felt fatigue when one of [my children] told me ‘I want to go back’ or ‘I do not want to go to school’. I had fatigue because of them.

He keeps always silent. I told him, ‘why do you say this? That you’re a disabled person, that you’re not able to talk? You can speak.’ He said, ‘but dad, I cannot speak English. It’s easier to say this. To keep silent.’ He was crying a lot. I was a crying a lot.

Experiences concerning the illbeing of relatives arrived through family reunion and challenges of remaking relationships, such as the ones described above, had profound effects in the first year of post-reunion life. This was experienced as a busy period with a sense of accelerated time, an active form of waiting for the possibility of making plans again. One or more years after reunion, not only do some of these tensions persist but also new forms of what participants refer to as ‘suffering’ are encountered, resulting from other family-related temporal disruptions.

A distinction needs to be made here between the experience of sponsors and that of spouses arrived through family reunion, all of whom are women in our study, after a period of separation. For the latter, the absence of the female extended family – primarily mothers and sisters – was emphasised as a cause of ‘suffering’ in the present, confirming that the reunification model of most western countries of destination, based on the idea of the ‘nuclear’ family, generates another form of separation that may be equally damaging for the wellbeing of refugees. As Sara testified,

Missing my family is the most difficult part … I came to my husband, but my family is still there [in Sudan], you cannot go there or bring them here. It makes me feel very bad, I always miss them.

Part of the suffering associated with separation – which persists after the ‘nuclear’ family is reunited – is a sense of ‘guilt’ that permeates everyday life. ‘Survival guilt’ has been defined as a complex phenomenon experienced by people who survive traumatic events (Pethania, Murray, and Brown Citation2018), of which the journey towards safety endured by asylum seekers, refugees, and spouses arrived via family reunion is an example (Goveas and Coomarasamy Citation2018). Leaving other close relatives at risk, especially following the recent intensification of conflict or political instability in participants’ countries of origin like Sudan and Iran, generates a sense of guilt since, as Sara continues explaining, ‘I am safe, and they are not.’ It is the problem of asynchronous time defined by Cwerner (Citation2010) – the asynchrony that exists between the flow of events in the home country and the everyday reality in the host society – here aggravated by limitations to ‘resynchronisation’ due to issues around safety, fear, uncertainty, and disrupted communication.

Associated with this experience of asynchrony is a heightened sense of responsibility towards those at home. For Yas, having survived a chronic illness as well as the journey towards safety is a sign that she interprets as having been ‘chosen’ to help her family at home and alleviate them from their struggles. Although her son and husband have in the meantime joined her through family reunion, concerns with her parents and siblings increased as the political situation in Iran became more unstable, and the risk for them higher. Hence, the trauma caused by the violence and disruption experienced prior to asylum and upon arrival remains noticeable through bodily and social disorder following reunion, with participants continuing to refer to bodily and social suffering in interconnected ways (Becker, Beyene, and Ken Citation2000a). Sleep disturbance, for example, which has been addressed in the literature in relation to PTSD and recognised as a common bodily symptom of time disruptions (Warner Citation2007), was often mentioned by participants. Materialising an important manifestation of suffering resulting from this asynchrony, they described an ‘inability to sleep’ (‘I cannot sleep because of the shooting. How can I sleep when they cannot?’), ‘waking up screaming’ (‘The other day there was thunder and I woke up screaming, I don’t know … I had a dream that I was in the middle of the war’), and the ‘sensation of being there’ (‘Sometimes I feel I am there, while I am asleep … walking, talking … I feel I am there hearing the shootings. When a plane passes by, I freak out because of the sound’).

While this bodily experience of asynchrony is also present amongst asylum seekers and refugees prior to reunion, it is important to note that it does not disappear long after family reunification, and that there is not necessarily a ‘return to normal’ as the urgency embedded in the period of waiting for reunion could lead to be expected (Rousseau et al. Citation2004). Moreover, family reunion can also lead to a resurgence of frustrations relating to the host country, associated with a growing or sudden awareness of the limitations of the new reality (Rousseau et al. Citation2004) and with the state control that persists even after refugee status is acquired and family reunion processes are completed. Once it is possible to partially ‘relax’ or think about making plans, the reality of the ‘wasted time’ that continues to be involved in dealing with institutional or organisational settings – for example through frequent visits to the job centre as a condition for receiving funds amongst those who did not have jobs, the inadequacy of the English language courses offered, or the waiting for permanent council accommodation that some still experience years after arrival – becomes an evident source of discontent and anxiety (Rotter Citation2016).

Concerns with housing and a lack of understanding of the system were described particularly by those in temporary or private accommodation. Fear of returning to a situation of homelessness, experienced by many during the waiting period of their asylum applications, was mentioned as a particular source of stress. Another temporal tension imposed by dominating bureaucratic procedures is associated with the job centre – the government office that provides information and advice about jobs and is also involved in the administration of benefits. Yassin anecdotally reported the job centre’s request that his mother, who was 64 years old at the time, ‘goes [to the job centre] and comes back every two weeks.’ He explained, expressing a sense of ‘wasted time’: ‘My mum … It has been three years now or two and a half years now, she just goes and comes back for nothing, there is nothing to do.’ Similarly, the experience of attending English language courses through English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) classes is often described as not meeting initial hopes and expectations. Waiting lists and ‘one size fits all’ classes, where attendants of different levels of language proficiency are taught together, as well as the difficulty in conciliating the different demands and constraints from the various institutional settings they must deal with, are a continuous source of temporal tensions. Malika, who is on her own with her five children aged between 7 and 14, described these tensions as resulting from a lack of institutional coordination and support, and referred to their manifestation in the body through stress:

I told the doctor last week that I am very stressed because of the job centre … They threatened me. That is the worst thing when someone threatens you. Sometimes I am in college and they will call from school that something happened to my son and I need to go … There is no coordination, I cannot do all that at the same time, especially because I am a single mum, their father is not around … I am the father and the mother … It is hard.

New temporal possibilities

Despite the challenges discussed above, participants also make the most of a series of possibilities that start to emerge following the first year post-reunion. For some, it is a period characterised by a sense of ‘organisation’, when time can finally be used more productively. Suraq, who arrived in 2018 from Sudan, defines it as a period when he ‘became more organised in time and money.’ This change was experienced mainly by men, whilst most women, whether arrived first or through family reunion, continue to encounter more obstacles in what they define as the objective of ‘improving myself’.

Yassin describes his life in Sudan as a ‘massive mess’, characterised by a sense of chaos and disorganisation in temporal terms:

Life in Sudan was a massive mess … I was doing too many things at the same time, and in Sudan there are too many kinds of problems … For example, nobody can respect your time, if they tell you they will come at four, they will come at six … Too many things you have to do in the same day, yes … Just like that you will see military in the street, everything is cancelled, you'll go back home … So, it was a massive mess.

It was quite bad, you would always think what is the next step, what will happen, it was always like that. So, we are waiting for the interview … After three months we got our interview, we were very happy, then we began our journey to wait for the results … It was a very long waiting time [over one year]. You see, every time you say, maybe tomorrow you will hear something, and you are not allowed to work, you are not allowed to study …

I have my short-term plan, I have my long-term plan, and that is what I learned here, the short-term plan and the long-term plan. I never had that before. I am relaxed now because I know what I should do after three years.

The sense of security that comes with predictability, order, and stability (Chase Citation2013) has allowed Yassin, like others, to begin having a routine and making further plans. It has also allowed him to stop – to be ‘quieter’ and to enjoy ‘stay[ing] alone more than before.’ He considers having time for himself to be part of what he defines as a ‘UK lifestyle’, of which he takes advantage. The opportunity to replace the restless pacing of the past for a kind of mental distancing gives him the necessary space to develop individual and family projects. He was expecting a second child and was able to retrain in an area he is more passionate about, being now in the first year, post-foundation, of his second university degree. Suraq, too, was taking an administration course in college, a decision that was motivated by the temporal tension he experienced through continuous waiting at the start of his journey in the UK:

There are lots of administration problems in Glasgow that need to be addressed. The main issue is the lengthy processes, the waiting needed for all public services, especially the NHS and how long it takes to get an appointment.

Women have similar plans of ‘improving’ themselves through retraining or further education. Yet for many, this is a more distant future project. On the one hand, language barriers, often due to more limited social and professional networks than men (Löbel and Jacobsen Citation2021; Spehar Citation2021), were recognised as still needing overcoming. On the other hand, their responsibilities towards the children and more intense preoccupation with relatives who remain in situations of risk at home, create an extended experience of waiting when compared with men. We observed this amongst women who came both as sponsors and through family reunion. Yet the narratives of two women in the latter category illustrate, in particular ways, how their experience of time changed since their arrival in the UK.

One of them is Sara, who came through family reunion one year and four months before we met. She feels ‘that all this time was wasted’, indicating continued uncertainty, both in relation to the future of her family in the UK and to the future of her extended family who remains at risk, increased by the recent conflict intensification in Sudan. Her narrative is of ‘wasted’ rather than ‘appropriated’ time, an experience associated with waiting for the reunion application to succeed from the perspective of those who stay in the country of origin, and with some frustration upon arrival.

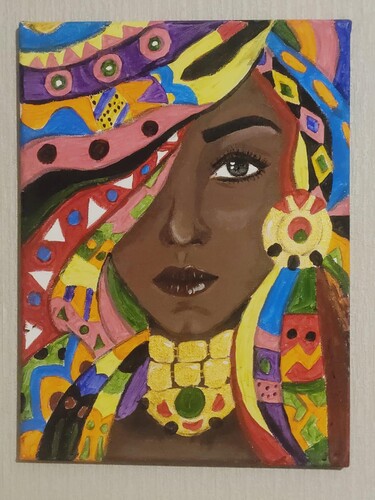

However, Sara also makes use of newly encountered temporal possibilities, such as the ‘quietening’ that she started to experience in her second year of living in the UK. The time embedded in what she describes as ‘quietening’ has allowed her to pursue a personal interest – painting () – which helped alleviate some emotional tension:

I was painting since I was in Sudan. When I got here, life became very busy with my daughter and not feeling settled yet. But recently I started to feel that I want to paint again … I felt a difference after I started painting. I didn't know that it had this big effect on me but once I started painting, I felt more positive. And you know, my daughter now goes to nursery, so I have more time for myself, I have more time to practice my hobbies.

Zainab, also arrived from Sudan through family reunion, uses time in a similar way, making the most of the current experience of slowness and waiting to practice cooking, which has a positive impact on her wellbeing: ‘Cooking is one of the things I really enjoy doing … Sometimes I like to take my time cooking so that at the end, whenever I produce something good, I feel happy.’ She chose to share the photo below (), as an example of traditional food that, like Sara’s African paintings, reminds her of home, hence demonstrating the power of time to revest sentiments of loss and sadness with meaning and purpose. In Zainab’s case, waiting is associated with the time it will take her to improve her English and materialise her project of starting a food business in the future.

Time to pursue these interests is recognised as also stemming from the transformations that occur in family dynamics, whereby the absence of the extended family, while lamented, minimises some of the obligations that did not allow for access to time as a resource to engage in meaningful activities (Kale Citation2024). As Sara explains, ‘in Sudan it wasn’t easy because life is so busy, you know, people come to visit you and you go and visit people … ’ It also results from the opportunity to have what Sara considers more ‘freedom of movement for me as a woman,’ also mentioned in the literature (e.g. Shishehgar et al. Citation2017), and expressed visually by Yas, who describes a sense of freedom and comfort when looking at the image of women paddleboarding that she took through participatory photography ():

Another consequence of separation from the extended family that participants – men in particular – recognise as an opportunity is the decrease in conflicts pertaining to children’s education, since the father's and mother's sides of the family are no longer involved in decisions in this respect (Rousseau et al. Citation2004). As Khaled explained,

After they arrived, I became more comfortable. I built a relationship with my children that makes me feel I am a good father. I became their friend, the source of their answers, or we try to search for answers together … The way I deal with them now is better, they are more comfortable around me. We play and talk, but before there was fear and respect … You know, I am their father, but there is no fear now.

Yas, who is finally working after three years of living in the UK, maintains that although the physical and emotional effects of trauma, and the pressure and sense of responsibility described above continue to affect her, she feels that she is ‘regaining it [a sense of self-worth] slowly, each thing at a time.’ ‘First, I got my college course, then driving license, then I bought my own car, and now I have a job. You find your place slowly.’ She associates this (long) process with the time it takes to regain a feeling of connection with society, since the job, education, and ‘social position’ she had in Iran were all lost (or at least the possibility of using them, as is the case of her university degree) upon arrival, when ‘one becomes nothing’.

The possibility of ‘becoming someone’ increases in cases where, as for the Burundian refugees living irregularly in Kenya studied by Turner (Citation2016), identity, place and nation are disjointed, and people make use of their displaced condition to achieve future emplacement. This was the case of Maryam and Saeed who, born in Iran with Afghan ancestry, experience life in the UK as the realisation of ‘something that [we] have been looking for so long’ – a sense of belonging that the Iranian government had deprived them from, due to not recognising their Iranian citizenship and denying them certain rights, such as that of studying in university: ‘We never felt that we belonged in Iran, we never felt that we belonged in Afghanistan, but now here we are reaching that feeling.’ As Maryam continued to explain,

I came to the country where I can have an identity of [my] own, with a physical document describing [myself] and where [I am] from, and where [my] daughter has the freedom [to] do whatever she wants and get an education in the future.

Strategies for overcoming time disruptions

When the effects of temporal tensions continue in the longer term, coping strategies are developed. Being close to nature is mentioned by many participants – both sponsors and those arrived through family reunion – as a strategy that quietens both body and mind. For Berhane, for example, sitting in the green parks of Manchester reminds him of his home village in Eritrea, whereas for Zainab it is the contrast between the green areas of Glasgow and the dry streets of Sudan, that gives her a sense of satisfaction when going for walks. Taha, too, mentions a self-established daily routine of walking by a lake on the way to work as an attempt to ‘forget’ and avoid ‘thinking too much’ – an idiom of distress that has been identified as demonstrating overlap with depression and anxiety in certain contexts (Mendenhall and Kim Citation2021). For Taha, who came from Sudan in 2018, walking in nature helps ‘all the ideas that are making a lot of noise in your mind become less intense:’

I come here [to the park] every day in the morning before I start my work, thirty minutes before. I just spend thirty minutes here, walk around, just relax, telling myself just good things, smile to myself, delete a lot of things … forget, forget, forget, forget … because I was thinking too much. Sometimes you don’t need to think so much, just calm down.

[The war] destroyed all my childhood memories, my neighbourhood memories from Iran, my family, my friends … even the smell of the streets and those people … It's all gone, it's all gone, you have to say goodbye forever. I lost my father last year and the thought that I can't be next to him is very heavy for me. It’s as if my memory is destroyed … I can never go back to them again.

For Tigrayan families in particular, the ritualistic practice of preparing coffee, also performed at home before coming to the UK, is a strategy, embedded in temporality, to ease their suffering. The preparation and sharing of Arabic coffee is a slow ritual that allows them to ‘kill time’ and, as other studies have shown, to release tension by replicating a normalising practice in an abnormal situation (Jones-Gailani Citation2017). Despite generating a sense of continuity between past and present, the practice is described by Alem and Selam as a way to ‘forget’, similar to Taha’s need to avoid remembering. Referring to the image he captured through participatory photography (), Alem says,

We are always thinking about the war … Sometimes we just want to forget, and we try to do something else. So that, I think, was one of the days we just wanted to prepare coffee and drink.

These strategies of patience and self-control thus continue to be used in similar ways to the silent waiting for the outcome of asylum of family reunion processes at an earlier stage of the journey. They are, likewise, an active form of waiting, filled with reflection and action that helps people cope with the suffering that continues to be experienced, and with making the most of the opportunities that also start to emerge (Rotter Citation2016). Such strategies can also be used to minimise the risk of public visibility and scrutiny that their bodies are subject to (Kale Citation2024), as Khaled’s emphasis on patience to deal with experiences of racism seems to indicate. They also demonstrate, however, that institutional domination and control continue to be used as tools of governmentality to maintain the marginality and compliance of refugee populations, for example through far-reaching and complex bureaucratic procedures of managing distribution assistance (Zetter Citation2007).

Conclusion

A sense of rupture and fragmentation embodies a broken and, consequently, painful self (Coker Citation2004). Important daily rhythms and predictability, which involve the opportunity to make plans, are disrupted amongst refugees (Sagbakken, Bregård, and Varvi Citation2020), causing what participants refer to as ‘suffering’. In the life period analysed in this article – one year or more post-family reunion – these disruptions, also caused until then by a long period of waiting for the outcome of asylum and family reunification processes, give way to a more active experience of time, characterised by increased confidence and the ability to plan for the future. Bureaucratic control concerning lengthy and inadequate service provision, as well as other stressors relating to traumatic memories, separation from extended family, sense of guilt, difficult relationships and heightened sense of responsibility continue to generate challenges that can cause suffering and bodily pain, yet strategies start to be put into place to cope with it.

In the narratives presented in this article, pain is also used as a tool with which people apprehend and express both trauma and their own marginality (Henry Citation2006). Some of the pain described by participants – also associated with a physical and mental state that they define as ‘fatigue’ – is not just an enduring effect of their experiences, but also a way to understand and mediate them, and to begin re-establishing order and control. In fact, reflection and action are present in this bodily experience of time, characterised by a heightened awareness of fears, desires and future possibilities, which makes waiting an intentional and agential, rather than passive, process (Rotter Citation2016).

Silent waiting, for example, can be used tactically to claim ownership of one’s time. After risky and uncertain journeys, as well as anxious waiting for families who remained at risk, some begin to embrace stillness rather than activity (Kohli and Kaukko Citation2018). Whereas most of the narratives analysed in this article are from sponsors (who experienced the consequences of the precarity involved in seeking asylum in the UK, a longer journey of displacement, and the temporal control and domination embedded in administrative processes), those arrived through family reunion also make use of newly encountered possibilities. A transformed temporal structure that includes a sense of ‘quietening’ and ‘slowness’ gives them the opportunity to develop individual interests and allows all – regardless of the time of arrival – to reproduce or create new rhythmic rituals (such as preparing coffee and walking in the park) as mechanisms to release tension. However, strategies involving what participants define as ‘patience’ and ‘self-control’, while active and reflective, are partly also a response to the institutional control that continues post-reunion, whereby refugees are required to comply and accept, maintaining their precarity and marginality.

Although some of the strategies that refugee families put in place to deal with their precarious conditions can be understood as a form of resilience, a note of caution is needed here. Following the participatory approach we adopted in this study, it is important to carefully consider concepts that may have different meanings for participants (Yotebieng, Syvertsen, and Awah Citation2019). First, the need to develop strategies that help endure suffering while remaining hopeful is linked, for some, to a strong sense of responsibility towards the family – both in the UK and in the home country – that may create more pressure. Second, most participant families emphasise the unceasing effects of the acute stress, trauma, and adversity they face rather than considering themselves an example of success in responding to these, hence indicating that their strategies are more connected with survival or alleviation than with the notions of wellbeing that resilience implies (Panter-Brick Citation2014).

To conclude, despite a continued sense of waiting and ‘temporariness’ (Stronks Citation2022), one or more years after two major temporal obstacles – asylum and family reunion applications – are successfully ‘resolved’, refugee families are better able to transform temporal tensions into an active and more positive experience of time, even if this transformation is still imbued in a state of liminality rather than stability or permanency.

Acknowledgements

Several people and organisations made this project possible. We wish to thank, first, Amy Lythgoe, Urška Ozimek and Iman Rafatmah from Together Now for the invaluable collaboration, and Amy, in particular, for having initiated the conversation that led to the creation of the project in the first place. Our community interpreters Iman Tajik, Maryam Pedramfar, Sisay Kahin and Soha Adelpour also played a key role in the research, not just with their interpretation work, but also through insightful conversations where they generously shared their knowledge and lived experience. Ayoola Jolayemi, who joined the project as film director, was a vital member of the team, for which we are thankful. We also wish to thank Gabby Cluness from Milk Café in Glasgow and Hannah Berry from Work for Change in Manchester, who helped us by providing the space for the final project workshops. CreativeUEA, The UEA University of Sanctuary, the Sainsbury Centre, and the Enterprise Centre at the University of East Anglia all played a key role in supporting the project’s photo exhibition and the film launch. We are also thankful to Manchester Central Library for having hosted the photo exhibition, and to Norwich Refugee Week, Cinema City Norwich, and Welcome to the UK, for having supported and hosted the documentary screenings. Most of all, we are indebted to the participant families for the generous time spent in sharing their lives with us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Although all participants were invited to the final workshops and the exhibitions, attendance in these was limited precisely due to the constraints of their temporal rhythms and to the way ‘life passes quickly,’ with some having started new jobs or studies, or expanded the family by the end of the research. More information about the project, including the online photo exhibition, can be found here: https://www.ueasanctuary.org/when-the-dust-settles-research-project/. Ethics approval to conduct this research has been granted by DEV Ethics Committee at the University of East Anglia (application number ETH2122-1571 and ETH2223-1730).

References

- Allsopp, J., E. Chase, and M. Mitchell. 2015. “The Tactics of Time and Status: Young People’s Experiences of Building Futures While Subject to Immigration Control in Britain.” Journal of Refugee Studies 28 (2): 163–182. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feu031.

- Anderson, B. 2020. “And About Time Too … : Migration, Documentation, and Temporalities.” In Paper Trails: Migrants, Documents, and Legal Insecurity, edited by S. B. Horton and J. Heyman, 53–73. Durham: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478012092-004.

- Aybec, C. M. 2015. “Time Matters: Temporal Aspects of Transnational Intimate Relationships and Marriage Migration Processes from Turkey to Germany.” Journal of Family Issues 36 (11): 1529–1549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14558298.

- Becker, G., Y. Beyene, and P. Ken. 2000a. “Health, Welfare Reform, and Narratives of Uncertainty Among Cambodian Refugees.” Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 24 (2):139–163. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005674428261.

- Becker, G., Y. Beyene, and P. Ken. 2000b. “Memory, Trauma, and Embodied Distress: The Management of Disruption in the Stories of Cambodians in Exile.” Ethos (Berkeley, Calif ) 28 (3): 320–345. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.2000.28.3.320

- Bissell, D. 2007. “Animating Suspension: Waiting for Mobilities.” Mobilities 2 (2): 277–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450100701381581.

- Chase, E. 2013. “Security and Subjective Wellbeing: The Experiences of Unaccompanied Young People Seeking Asylum in the UK.” Sociology of Health & Illness 35 (6): 858–872. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01541.x.

- Cohen, E. F. 2018. The Political Value of Time: Citizenship, Duration, and Democratic Justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108304283.

- Coker, E. M. 2004. “‘Traveling Pains’: Embodied Metaphors of Suffering Among Southern Sudanese Refugees in Cairo.” Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 28 (1):15–39. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MEDI.0000018096.95218.f4.

- Collyer, M. 2007. “In-Between Places: Trans-Saharan Transit Migrants in Morocco and the Fragmented Journey to Europe.” Antipode 39 (4): 668–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2007.00546.x.

- Conlon, D. 2011. “Waiting: Feminist Perspectives on the Spacings/Timings of Migrant (Im)mobility.” Gender, Place & Culture 18 (3): 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2011.566320

- Cwerner, S. B. 2010. “The Times of Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27 (1): 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830125283.

- Fee, M. 2022. “Lives Stalled: The Costs of Waiting for Refugee Resettlement.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (11): 2659–2677. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1876554.

- Fresnoza-Flot, A. 2014. “The Bumpy Landscape of Family Reunification: Experiences of First- and 1.5-generation Filipinos in France.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (7): 1152–1171. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.956711.

- Goveas, J., and S. Coomarasamy. 2018. “Why Am I Still Here? The Impact of Survivor Guilt on the Mental Health and Settlement Process of Refugee Youth.” In Today’s Youth and Mental Health: Hope, Power, and Resilience, edited by S. Pashang, N. Khanlou, and J. Clarke, 101–117. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64838-5_6

- Gray, B. 2011. “Becoming Non-Migrant: Lives Worth Waiting For.” Gender, Place & Culture 18 (3): 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2011.566403

- Griffiths, M. B. E. 2014. “Out of Time: The Temporal Uncertainties of Refused Asylum Seekers and Immigration Detainees.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (12): 1991–2009. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.907737.

- Henry, D. 2006. “Violence and the Body: Somatic Expressions of Trauma and Vulnerability During War.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 20 (3): 379–398. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.2006.20.3.379

- Hyndman, J., and G. Wenona. 2011. “Waiting for What? The Feminization of Asylum in Protracted Situations.” Gender, Place & Culture 18 (3): 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2011.566347

- Jones-Gailani, N. 2017. “Qahwa and Kleiche: Drinking Coffee in Oral History Interviews with Iraqi Women in Diaspora.” Global Food History 3 (1): 84–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/20549547.2017.1278347.

- Kale, A. 2024. “‘Enjoying Time Alone’: Exploring Solitude as a Positive Space for Refugee Wellbeing.” Journal of Refugee Studies 37 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fead054.

- Kohli, R. K. S., and M. Kaukko. 2018. “The Management of Time and Waiting by Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Girls in Finland.” Journal of Refugee Studies 31 (4): 488–506. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fex040.

- Kuhlemann, J. 2023. “Linking Refugees’ Time Perceptions and Their Time Use.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2219016.

- Löbel, L. M., and J. Jacobsen. 2021. “Waiting for Kin: A Longitudinal Study of Family Reunification and Refugee Mental Health in Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (13): 2916–2937. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1884538.

- Mendenhall, E., and A. W. Kim. 2021. “Rethinking Idioms of Distress and Resilience in Anthropology and Global Mental Health.” In Global Mental Health Ethics, edited by A. R. Dyer, B. A. Kohrt, and P. J. Candilis, 157–170. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66296-7_10.

- Neal, D. 2023. A Reinspection of Family Reunion Applications: September – October 2022. London: Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI). Accessed November 15, 2023. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1137651/A_reinspection_of_family_reunion_applications_September___October_2022.pdf.

- Panter-Brick, C. 2014. “Health, Risk, and Resilience: Interdisciplinary Concepts and Applications.” Annual Review of Anthropology 43 (1): 431–448. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102313-025944

- Parkin, D. 1999. “Mementoes as Transitional Objects in Human Displacement.” Journal of Material Culture 4 (3): 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/135918359900400.

- Pethania, Y., H. Murray, and D. Brown. 2018. “Living a Life That Should Not Be Lived: A Qualitative Analysis of the Experience of Survivor Guilt.” Journal of Traumatic Stress Disorders & Treatment 7 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4172/2324-8947.1000183.

- Refugee Council. 2023. “The Truth about Channel Crossings and the Impact of the Illegal Migration Act.” Accessed November 15, 2023. https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/The-truth-about-channel-crossings-and-the-impact-of-the-illegal-migration-act-Oct-2023.pdf.

- Rotter, R. 2016. “Waiting in the Asylum Determination Process: Just an Empty Interlude?” Time & Society 25 (1): 80–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X156136.

- Rousseau, C., M.-C. Rufagari, D. Bagilishya, and T. Measham. 2004. “Remaking Family Life: Strategies for Re-establishing Continuity among Congolese Refugees During the Family Reunification Process.” Social Science & Medicine 59 (5): 1095–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.011.

- Sagbakken, M., I. M. Bregård, and S. Varvi. 2020. “The Past, the Present, and the Future: A Qualitative Study Exploring How Refugees’ Experience of Time Influences Their Mental Health and Well-Being.” Frontiers in Sociology 5 (46): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.00046.

- Salih, R. 2017. “Bodies That Walk, Bodies That Talk, Bodies That Love: Palestinian Women Refugees, Affectivity, and the Politics of the Ordinary.” Antipode 49 (3): 742–760. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12299.

- Shishehgar, S., L. Gholizadeh, M. DiGiacomo, A. Green, and P. M. Davidson. 2017. “Health and Socio-Cultural Experiences of Refugee Women: An Integrative Review.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 19 (4):959–973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0379-1.

- Spehar, A. 2021. “Navigating Institutions for Integration: Perceived Institutional Barriers of Access to the Labour Market among Refugee Women in Sweden.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (4): 3907–3925. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa140.

- Stronks, M. 2022. Grasping Legal Time: Temporality and European Migration Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108886574.

- Suårez-Orozco, C., I. L. G. Todorova, and J. Louie. 2002. “Making up for Lost Time: The Experience of Separation and Reunification Among Immigrant Families.” Family Process 41 (4): 625–643. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.00625.x.

- Turner, S. 2016. “Staying out of Place: The Being and Becoming of Burundian Refugees in the Camp and the City.” Conflict and Society 2 (1): 37–51. https://doi.org/10.3167/arcs.2016.020106.

- Uyun, Q., and E. Witruk. 2017. “The Effectiveness of Sabr (Patience) and Salat (Prayer) in Reducing Psychopathological Symptoms after the 2010 Merapi Eruption in the Region of Yogyakarta, Indonesia.” In Trends and Issues in Interdisciplinary Behavior and Social Science, edited by F. L. Gaol, F. Hutagalung, C. F. Peng, Z. Isa, and A. R. Rushdan, 165–173. Leiden: CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315269184.

- Warner, F. R. 2007. “Social Support and Distress among Q’eqchi’ Refugee Women in Maya Tecún, Mexico.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 21 (2): 193–217. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.2007.21.2.193.

- Welfens, N., and S. Bonjour. 2021. “Families First? The Mobilization of Family Norms in Refugee Resettlement.” International Political Sociology 15 (2): 212–231. https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olaa022.

- Yotebieng, K. A., J. L. Syvertsen, and P. Awah. 2019. “‘Is Wellbeing Possible When You Are Out of Place?’: Ethnographic Insight into Resilience among Urban Refugees in Yaoundé, Cameroon.” Journal of Refugee Studies 32 (2): 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fey023.

- Zetter, R. 2007. “More Labels, Fewer Refugees: Remaking the Refugee Label in an Era of Globalization.” Journal of Refugee Studies 20 (2): 172–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fem011.