ABSTRACT

This article investigates the effect of structural and individual factors on migration aspirations in a secondary migration context. Through an online survey experiment conducted with Syrian migrants (N = 551) living in Turkey, we unpack factors explaining aspirations to stay and move onward from the current country of residence. The findings indicate that open borders alone do not compel migrants to move onward. Instead, employment opportunities in their current residence play a crucial role in shaping aspirations to stay put. Moreover, individuals inclined to take risks are more likely to migrate, even when strict border controls are in place. By highlighting the question of what motivates migrants to stay as well as to move onward, this research emphasizes individual differences in forming migration aspirations and contributes to migration aspirations literature in the secondary migration context.

Introduction

On 14 June 2023, eight years after so-called 2015 ‘refugee crisis’, a fishing trawler carrying 750 migrants from Italy to Greece sank in the Mediterranean Sea. Only 104 survived, making it one of the deadliest incidents of its kind in recent times. In the aftermath, Greek border guards were accused of intentional involvement in the trawler’s sinking, leading to significant criticism and controversy. The incident was much more than a tragic border spectacle: it has multiple layers, and offers insights into how migration policymaking affects migrant journeys that are full of risks.

Despite being one of the deadliest incidents, the June 14th incident is not unique or unusual in the Mediterranean. The EU’s migration and border policies have turned the Mediterranean route into a space of violence, death, drowning of refugee boats, and pushbacks (İşleyen and Qadim Citation2023; Tazzioli Citation2016). Meanwhile, funding schemes in the context of migration governance construct host countries – usually the ones neighboring conflict-torn regions – as spaces of opportunities to avoid migrants moving onward to developed Western countries (Müller-Funk, Üstübici, and Belloni Citation2023). Albeit limited, and insufficient, it is assumed that providing opportunities such as employment to migrants would make them integrate in the host countries and eventually increase their aspiration to stay put. In a way, migration policies oscillate between increasing border controls along migration routes, and providing migrants with opportunities in order to keep them where they are (Kipp and Koch Citation2018). Yet, some migrants who are more prone to take risks still embark on dangerous journeys, usually as a way of showing resistance towards border controls (Kiriscioglu and Ustubici Citation2023; Maâ Citation2023; Schapendonk, Bolay, and Dahinden Citation2021).

In this context, the following open question can be posed: To what extent are migration aspirations subject to exogenous shocks, such as border closures, or opportunities such as employment, in the context of secondary migration? While tackling this important empirical puzzle, our conceptual framework also aims to explore whether migrants’ risk-taking attitudes influence their aspiration to embark on dangerous journeys.

This research contributes to the migration literature by focusing on secondary migration aspirations, where individuals had to flee their home country for another and consider further migration from the first host country. To answer what motivates migration aspirations in such constrained mobility contexts, we test the effect of structural and individual level factors with a between-group online survey experiment conducted with Syrian migrants in Turkey.Footnote1 We include border closures, employment opportunities, and subjective risk-taking attitudes as factors affecting migration aspirations. Survey experiments have so far been used to investigate migration decision-making outside the context of forced migration (Ewers and Shockley Citation2018; McKenzie and Yang Citation2012; Petzold Citation2017). Hence, using survey experiments to study migration aspirations in a forced displacement context is a novel approach. Recently, only a few experimental studies have investigated migration aspirations using the framework of push and pull factors between destination and origin countries (Bah and Batista Citation2018; Detlefsen, Heidland, and Schneiderheinze Citation2022; Hager Citation2021). We contribute to this research line by employing an experimental setting that enables us to manipulate the structural factors shaping onward migration aspirations in forced migration contexts. Plus, our approach allows us to gain insights into the variations in individual personality traits.

Existing research explores factors shaping migration aspirations mainly at the structural and individual levels, within the context of either the home or destination country. Structural-level-focused studies examine the impact of border externalization policies on migration management (Cobarrubias et al. Citation2023; Geiger and Pécoud Citation2010), while individual-focused research investigates perceptions of individuals, life cycles, and personal attributes (Alpes, Citation2014; Boccagni Citation2017; Kuschminder, de Bresser, and Siegel Citation2015; Syed Zwick Citation2022). A few studies examine migration aspirations at a combination of individual and structural levels (Helbling and Morgenstern Citation2023). Moreover, the majority of research on migration aspirations, with a few exceptions (Hager Citation2021; Kiriscioglu and Ustubici Citation2023; Müller Funk Citation2019), has concentrated on either the home or destination country, largely overlooking aspirations to stay in the current host country. This research aims to address this gap, generating insights into the onward migration decision-making patterns in forced displacement contexts.

Our findings indicate that implementing open border policies does not in itself compel migrants to move onwards. Instead, migrants consider employment opportunities in their current place of residence, even when borders are open for passage (i.e. to such welfare states as the EU countries). However, migrants’ aspirations are not only shaped by these policies. Migrants are neither victims, nor passive pawns without agency (De Haas Citation2021). Thus, our study also provides a room for human agency by analyzing differences in individual characteristics in forming migration aspirations. Our findings show that individuals with a higher inclination for risk-taking are more likely to move onward, even when confronted with strict border controls. Incorporating risk-taking attitudes as individual characteristics brings a novel approach to migration literature, showing that not every migrant can be deterred by strict border controls.

Turkey is a suitable case to explore secondary migration aspirations. Besides being a host country for around 3.1 million registered Syrian migrants, Turkey poses geographical significance as one of the European Union’s external borders.Footnote2 After the EU-Turkey Statement in 2016, Turkey has been constructed as a space to deter migrants from entering the EU’s borders and equipped with, albeit inadequate, policy interventions which aim to foster migrants’ aspirations to stay put by providing opportunities for local integration (Üstübici, Kirişçioğlu, and Elçi Citation2021). Based on a convenient sample of Syrians living in Turkey (N = 551), we asked the participants to assess four experimental vignettes about a hypothetical person and a control group. We crossed two vignettes involving border closures and employment opportunities to evaluate the conditions that would shift migration aspirations.

The article is organized as follows. We first discuss the existing literature on migration aspirations, particularly explaining the relevance of border closures and externalization policies, employment opportunities, and risk-taking attitudes in migration journeys by presenting our hypotheses. Plus, we briefly present the social, political and legal contexts that Syrians are subjected to in Turkey that inspired the design of the survey experiment. Second, we explain our data and experiment design. The third section lays out the results using regression models. Finally, we discuss the policy implications of the interaction between border externalization policies and employment opportunities, and the role of risk-taking attitudes in migration aspirations literature.

Theoretical framework

We define migration aspirations as the perspectives of migrants on their future mobility. The aspirations – abilities framework combines structural and individual factors to understand how aspirations and abilities are formed (Carling Citation2002, Citation2014; Carling and Collins Citation2018; Carling and Schewel Citation2018). To unpack how aspirations are formed, the framework analyzes communal social, economic, and political contexts at the macro level, and individual characteristics at the micro level, in determining who wants to migrate and who wants to stay. On the individual level, the framework focuses on the characteristics that affect how people cope with restrictive migration policies. Against this complex theoretical model, this paper selects two aspects at the structural level (border externalization policies and employment opportunities), and focuses on risk-taking attitudes at the individual level.

Structural factors

Border closures and externalization policies

The externalization of migration management has become a significant concern for various countries, including the U.S., Australia, the member states of the European Union, and, more recently, countries in the Global South (Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2019). Externalization is a broader term and refers to the activities undertaken by states, directly or indirectly, outside their territorial boundaries to control borders (Cobarrubias et al. Citation2023).Footnote3 Notably, the states in the Global North have developed strategies to prevent the entry of undesirable migrants at their borders (Hyndman and Mountz Citation2008). Scholars have explored how this unwanted migration influences the processes of border externalization in receiving states (Stock, Üstübici, and Schultz Citation2019; Tsourapas Citation2019), focusing on the practices of state actors (Côté-Boucher et al. Citation2014; El Qadim Citation2017) at the discursive and practice levels (İşleyen, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Karadağ, Citation2019). While the literature has debated the effectiveness of these border externalization practices, the impact of such policies on migrants’ perceptions has received less attention (Hager Citation2021). This study aims to contribute to this particular research trajectory.

Common sense would say that open borders would increase migration. While open borders may initially increase migration from less developed to developed regions of the world, evidence shows that they also bolster circulation and return (de Haas, Vezzoli, and Villares-Varela Citation2019; Flahaux and Vezzoli Citation2017; Vezzoli Citation2021). Second, closed borders are assumed to be stopping migrants without documents. Some scholars show that border enforcement policies decrease the number of migrants crossing the borders (Alden Citation2017; Sorensen and Carrion-Flores Citation2007). Despite the decreasing numbers, border closures fail to deter migrants from taking risks (Dávila, Pagán, and Soydemir Citation2002; Gathmann Citation2008; Massey, Pren, and Durand Citation2016). Rather than stopping migrants, closed borders direct them to pursue alternative, more dangerous channels (Vezzoli Citation2021). In a way, border externalization policies create a self-perpetuating cycle, forcing migrants to take risks at borders rather than deterring them (Massey et al. Citation2016).

Due to challenging living conditions, some Syrians residing in Turkey are inclined to consider onward migration, particularly towards Europe. Being deprived a full-fledged refugee status without a prospect of local integration (Baban, Ilcan, and Rygiel, Citation2017), experiencing economic vulnerability compared to natives (Elçi, Kirisçioglu, and Üstübici Citation2021), and facing limited access to protection (Karadağ and Üstübici Citation2021) pose significant challenges for Syrians living in Turkey. Recent strict visa policies and closed borders limit their options for legal migration channels (Welfens and Bekyol Citation2021), and direct them to take high risks in undocumented migration (Kiriscioglu and Ustubici Citation2023).

When Syrian migrants first arrived in Turkey, many moved on to seek asylum in EU countries. In 2015, around 1.3 million migrants fled Turkey. The EU and its member states responded to this influx by closing their borders under the discourse of ‘the refugee crisis’.Footnote4 In response, the EU-Turkey Joint Action Plan (November 2015) and the EU-Turkey Statement (March 2016) were implemented, representing the EU’s efforts to externalize its migration and border policies (İşleyen, Citation2018a; Üstübici Citation2019). Additionally, Turkey was promised financial support by the EU, under the Facility for Refugees in Turkey (FRIT), to be spent on the protection and integration of displaced communities, especially Syrians. The design of these policy interventions reflects the rationale of the current international asylum regime, perceiving the secondary mobility as politically undesirable. Although the legal basis and effectiveness of these migration and border policies are widely debated (Aydın Düzgit, Keyman, and Biehl Öztuzcu Citation2019; Danış Citation2021; Pries and Zülfikar Savci Citation2023; Schiefer, Düvell, and Sağıroğlu Citation2023; Tekin Citation2022; Ulusoy and Battjes Citation2017), to our knowledge, there is no study measuring the effectiveness of these policies and the validity of their assumptions in the context of Turkey using survey experiments.

Evidence suggests that aspirations to move onward from Turkey persist (Kuschminder et al. Citation2019; Üstübici and Elçi Citation2022), despite the strict border controls initiated with the EU-Turkey Statement of March 2016. According to the latest statistics from the Presidency of Migration Management (PMM) (Citation2023), the number of migrants apprehended at the borders increased after the so-called refugee crisis in 2015. Despite the EU’s efforts to externalize its migration and border policies with the EU-Turkey Statement, border crossings continued. The number of apprehended individuals tripled between 2015 and 2019, from 146,485 to 454,662. Although the number of apprehended individuals declined during the pandemic to 122,302, in 2022 it reached a second peak of 285,027. The majority of apprehended migrants are Afghans and Syrians but also include Palestinians and Iraqis. Frontex (European Border and Coast Guard Agency) (Citation2023) data also show a similar trend for the Eastern Mediterranean route for undocumented border crossings. The total number of people who have lost their lives in the Mediterranean Sea since 2014 has reached almost 25,000 (Sunderland Citation2022). In short, people who face dire living conditions may feel compelled to continue their journey despite the risks (Kiriscioglu and Ustubici Citation2023). Hence, we expect that:

Hypothesis 1: Decreasing (increasing) risks at the borders and welcoming (exclusionary) policies in wealthier countries motivate aspirations to move onward from (stay in) the current country of residence.

Employment opportunities

The second line of research focuses on the role of employment opportunities in migration aspirations. Although the effect of employment opportunities on migration aspirations is commonly measured from the origin-host country perspective, i.e. employment opportunities in host countries (Becerra et al. Citation2010; Chindarkar Citation2014; Groenewold, de Bruijn, and Bilsborrow Citation2012; Roth and Hartnett Citation2018), the role of employment opportunities in the secondary migration context is less studied (Sahin Mencutek and Nashwan Citation2021).

Previous research shows that economic concerns motivate onward migration towards countries with better employment opportunities (Collyer Citation2006; Collyer, Düvell, and de Haas Citation2012; Dimitriadis Citation2021; Esteves, Fonseca, and Malheiros Citation2018; Hager Citation2021; Kuschminder Citation2018; Van Hear Citation2006). In the secondary migration context, satisfaction with employment opportunities fosters aspiration to stay in the current place rather than move onwards. Some other research, however, shows that regular income and remittance capabilities can provide migrants with the opportunity to make savings for onward migration (Donini, Monsutti, and Scalettaris Citation2016), especially in countries where migrants do not have alternative channels to smuggling. Shortly, financial security is a strong determinant in forming migration aspirations. The direction of migration aspirations, based on employment opportunities, is still contextual: while for some, financial means may enhance capabilities to move onwards, for others, it may imply improving one’s livelihood, hence fostering aspirations to stay put (Mata-Codesal Citation2018).

Formal employment opportunities for Syrian migrants in Turkey are limited due to policies that restrict their integration into the labor market. For instance, the Regulation on Work Permits of Foreigners Under Temporary Protection launched in January 2016, based on the EU-Turkey Joint Action Plan, allowed Syrians to access work permit procedures through their employers, although implementation has been somewhat restricted. Of almost 2 million working-age Syrians, only 91,500 individuals were granted work permits in Turkey.Footnote5 As a result, most working-age Syrians have ended up in insecure or underemployed positions in the informal sector (Bélanger and Saracoglu Citation2020; Düvell, Schiefer, Sağıroğlu, and Mann Citation2021). The lack of or limited employment opportunities in Turkey poses a significant challenge for migrants who aspire to stay in Turkey but feel obliged to move onwards. In this regard, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2: Legal (precarious) employment opportunities foster (hinder) aspirations to stay in the current country of residence.

Individual factors

Risk-taking attitudes

Even when border crossing is ‘a matter of life and death’ (Walters Citation2011, 138), some migrants aspire to migrate despite the risks involved (Kaytaz Citation2016; Strasser and Tibet Citation2019; Topak Citation2014). Research shows that incorporating risk-taking attitudes into migration aspirations research could explain why individuals aspire to move onwards, stay, or return (Kiriscioglu and Ustubici Citation2023; Williams and Baláž Citation2014). If individual differences in risk-taking attitudes significantly shape migration aspirations, then structural conditions, such as border externalization policies, would not impact all individuals equally. Border externalization policies are predominantly based on the assumption that being aware of risks on the route would deter migrants. But this assumption that migrants lack knowledge fails to account for individual differences in risk-taking propensity, which can vary widely among migrants. Therefore, the effectiveness of these policies in deterring migration cannot be assumed to be universal and must be understood within the context of differences in individuals’ characteristics.

Migrants who venture the risks of borders are neither incognizant of the risks involved in their journey nor ‘irrational’ decision-makers (Hernández-Carretero and Carling Citation2012; Pagogna and Sakdapolrak Citation2023). Conversely, migrants are often well-informed about the dangers en route (Belloni Citation2016). With this information, migrants anticipate the risks at each step of their migration journeys and form their aspirations accordingly (Kiriscioglu and Ustubici Citation2023). These findings challenge the notion that migrants are passive victims entirely reliant on external constraints (De Haas Citation2021). Instead, migrants exhibit agency, and their attitudes toward risk-taking are highly individualized. In this regard, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3: High (Low) tendency to take risks decreases (increases) the effects of structural barriers on the aspiration to move onwards (stay put).

Methods and data collection

We conducted an online survey from 18 November to 31 December 2020, utilizing Facebook and Instagram advertisements to recruit participants through the social media accounts of MireKoc research center at Koc University (N = 551).Footnote6 These ads invited individuals to participate in a survey regarding their migration experiences in Turkey. To ensure privacy and anonymity, we collected data using the Qualtrics survey tool and randomly assigned respondents to different experimental groups. The survey and its advertisements were presented in Arabic and were geographically limited to Turkey. Furthermore, we targeted Syrian individuals through online advertisements, inviting them to participate. All participants were provided with an informed consent form before initiating the survey. Only those who granted their consent were given access to the survey questions. Respondents who only partially completed the survey, those who later indicate not having Syrian nationality, and those who failed attention checks were excluded from the analysis. On average, participants took 31 minutes (standard deviation = 42) to complete the survey.

We chose not to offer incentives to recruit participants for several reasons. Firstly, while incentives are commonly used to increase response rates in online surveys, our pilot surveys did not indicate any difficulties in obtaining responses that would necessitate the use of incentives. Secondly, research suggests that incentives can introduce measurement errors, as respondents may rush through the survey to obtain the incentive quickly (Elliott and Valliant Citation2017). Additionally, offering incentives may raise ethical concerns, particularly in the context of our study in Turkey, where Syrians often live in precarious conditions and rely on aid for their livelihoods. Providing a survey with a prize could be perceived as misleading and may create a sense of dependency on aid among respondents.

The convenience sampling technique employed in our study had certain constraints due to our reliance on Facebook and Instagram advertisements for participant recruitment. As a result, our sample may exhibit bias towards individuals who are more educated, literate, and financially affluent, potentially overlooking illiterate, elderly, and economically disadvantaged Syrian refugees. To avoid additional bias, we strictly relied on social media ads and did not share the link to the survey in other platforms. Furthermore, since the survey was conducted online, possession of a smartphone or computer and access to Facebook and Instagram accounts were prerequisites for participation. Consequently, our sample is limited to Syrian refugees who have access to these devices and online platforms.

Despite the inherent challenges associated with sampling, recent research suggests that online platforms can be valuable tools for surveying hard-to-reach populations, including immigrants and refugees (Elçi et al. Citation2021; Ersanilli and van der Gaag Citation2020; Pötzschke and Weiß Citation2021). Additionally, without comprehensive knowledge of the total population of Syrian refugees in Turkey, it is difficult to ascertain whether an in-person survey conducted in a specific neighborhood densely populated by migrants would be more accurate and representative than an online survey. It is important to note that during the COVID-19 pandemic, online surveys provided researchers with a safer means of collecting data. Furthermore, compared to face-to-face and phone surveys, gathering data through social media advertisements proves more cost-effective, time-efficient, user-friendly, and secure.

Experiment design

We employed a between-group experimental design to examine the impacts of border closures and employment conditions. Participants were randomly assigned to one of five different groups (see ). Next, they were introduced to the following statement: ‘Now, you are going to read a story about Ahmad and his family. Please read the story and then answer the question’. Those in the treatment groups were exposed to one of the four distinct experimental vignettes (T1, T2, T3, or T4), each depicting a hypothetical individual, while participants in the control group were presented only with a baseline scenario. summarizes the experimental design, illustrating the various combinations of border closures and employment opportunities manipulated to create favorable and unfavorable conditions for migration recommendations.

Table 1. Experimental vignettes.

When designing the vignettes, we constructed a hypothetical person to uphold ethical considerations. This approach was chosen to avoid disseminating misinformation within refugee communities and networks, as direct questions and factual scenarios could potentially lead to speculation about the situation at the borders. Our primary concern was to prioritize the safety and well-being of the participants. Hence, opting for a hypothetical person was deemed the best option. In addition, we aimed to decrease variation in the stimulus, which would be high if, for example, we primed participants to think about their current situation.

Our objective was to examine the impact of border closures and employment opportunities on migration aspirations. To achieve this, we presented Ahmad’s situation to all groups. We sought to determine whether the border and employment conditions differed from the control group. We chose Ahmad as a familiar figure among the Syrian refugee population in Turkey, as they often work in precarious jobs. Additionally, we focused on a single male migrant rather than a migrant with a family, as the presence of a family can complicate migration decision-making (Dubow and Kuschminder Citation2021; Kiriscioglu and Ustubici Citation2023). In other words, by constructing a control group where no particular policy intervention is mentioned, we aimed to understand the respondents’ migration aspirations when the conditions of border and employment were not explicit. Then, we aimed to test whether the changing conditions of borders and employment opportunities make any difference in the direction of migration aspiration. Methodologically, we sought a baseline group to detect variations from the control group and significant differences across treatments, as experimental interventions affect aspirations (Gaines, Kuklinski, and Quirk Citation2007; McDermott Citation2002).

We checked the randomization and distribution of respondents in the experimental groups according to their demographic characteristics, whether they receive the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN) aidFootnote7, and their level of wealth. The Wald test after the multinomial logistic regression received an insignificant result (X2(20) = 25.64, p = 0.178), which means randomization is successful (see for the distribution of demographic and ESSN variables). Hence, we do not need to use control variables.

Table 2. Distribution of respondents per experiment group.

Variables

Following the presentation of the vignettes, we asked the following question as our dependent variable: ‘If you were Ahmad, would you be willing to stay in Turkey, or move on to another country, or return to Syria?’ Descriptive analysis of the responses reveals that 53.53% of respondents recommended staying in Turkey, 44.29% suggested moving to another country, and only 2.08% selected the option to return. While the return option was included in the question for theoretical reasons (Carling Citation2019), we did not specifically prime for it in the experimental design. As a result, we generated three dependent variables. First, our main dependent variable is binary, excluding return responses from the analysis. Second, as a robustness check, we generated another binary dependent variable in which we coded both move and return as 1 and 0 otherwise. Third, we generated a categorical dependent variable. We coded move responses as 1, stay responses as 2, and return responses as 3 to conduct a multinomial logistic regression. The results do not show a striking difference between dependent variables. To assess our assumptions, we conducted a logistic regression analysis using our main dependent variable and dropping the return responses (See Online Appendix for robustness checks and other information about variables in the randomization checks).

We considered subjective risk-taking attitude as a moderating factor for the effects of border closures and employment opportunities. Risk-taking attitudes are fundamental drivers of human decision-making processes, influencing individuals’ perceptions of risk, their willingness to take risks, and their overall behavioral responses to uncertain situations. In the context of our study, we argue that individuals’ advice in a hypothetical migration scenario reflects their risk-taking attitudes, as these attitudes shape how individuals assess and respond to constraints. By examining the relationship between risk-taking attitudes and advice-giving behavior, we aim to elucidate the underlying mechanisms forming individuals’ aspirations. This analysis contributes to a deeper understanding of the factors that influence migration aspirations in real-world scenarios.

We operationalized subjective risk-taking attitudes using a general question that captured individuals’ overall tendency towards risk-taking: ‘How do you see yourself in general? Are you generally a person who is fully prepared to take risks, or do you try to avoid taking risks in your life?’ Respondents provided their responses using a Likert scale ranging from ‘not willing to take risks’ (1) to ‘extremely willing to take risks’ (5). The average score was 2.63, with a standard deviation of 1.16, reflecting the participants’ self-perceived inclination towards risk-taking behavior. We opted for a self-reported assessment of risk for two primary reasons. Firstly, risk-taking attitudes are known to be influenced by individuals’ personal life experiences (Barnett and Breakwell Citation2001), making self-perceptions theoretically relevant for measuring risk-taking. Secondly, subjective measurement of risk attitudes is considered a valuable overall measure, as it is presumed to capture a stable risk preference capable of predicting risk-taking behavior across different domains (Charness, Gneezy, and Imas Citation2013).

Self-reported measurements of risk are often criticized for overlooking domain-specific differences in risk-taking attitudes. For example, an individual might be more inclined to take risks in financial matters but less so in health-related issues. To address this concern, Weber, Blais, and Betz (Citation2002) developed the DOSPERT scale, which aims to capture variations in risk-taking preferences across different domains. However, due to the length of our survey and to avoid cognitive fatigue among participants, we opted for a simpler elicitation question. Therefore, we utilized a single, simplified self-reported measurement, which is also easier for participants to comprehend (Charness et al. Citation2013).

Results and discussion: the interplay between border closures and employment opportunities, and the mediating effect of risk-taking attitudes

In this section, we use evidence from the survey experiment to answer the following two questions: To what extent are migration aspirations subject to exogenous shocks, such as increasing or decreasing risks at the borders? And to what extent are they shaped by opportunities such as employment? We conducted two different logistic regressions to test the effects of treatments, including moderation with subjective risk-taking attitudes.

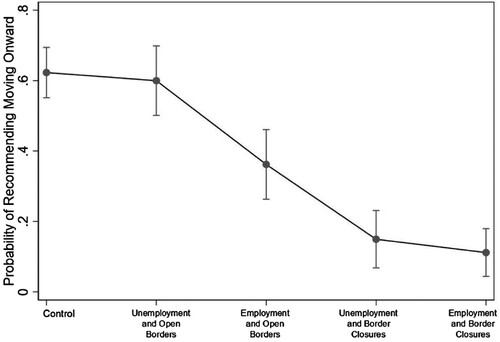

illustrates that all treatments significantly differ from the control group except for the first treatment. All other three treatments significantly motivate aspiration to stay in the current country of residence. (see ).Footnote8 Moreover, the margins plot illustrates that respondents in the unemployed and open borders vignette are more likely to move on to a third country than stay in Turkey compared to other treatment groups. In particular, a significant difference between ‘Unemployment and open borders’ and ‘Employment and open borders’ indicates that employment is crucial to staying, even when borders are open.

Table 3. Logistic regression results.

Policymakers assume that border externalization policies deter migrants from moving onward. This assumption on the effectiveness of deterrent migration policies overemphasizes the significance of border closures. Moreover, the emphasis on border closures overlooks the effect of opportunities provided for migrants. At first sight, our results indicate that migrants recommend staying in the country of residence when borders are closed, and countries do not implement welcoming policies for migrants (see ). However, what is surprising in our findings is that opening the borders does not increase the probability of recommending moving onward. Contrary to the expectations of policymakers, open border policies and welcoming policies of the destination countries are not the main drivers for migrants to recommend moving onward. In this regard, based on the interrelation between border closures and employment opportunities, we explain why the assumption that border enforcement policies deter migrants is wrong.

First, our experimental design confirms that border controls should not be considered separate from employment opportunities provided to migrants. As shows, employment opportunities significantly increase migrants’ probability of staying in the current country, regardless of the conditions of the borders. In other words, when migrants are provided with employment opportunities, staying in the current country is seen as a better option than moving onwards to Europe, even when the dangers on the route are minimal. In this regard, we reject Hypothesis 1, indicating that decreasing dangers at the borders and welcoming refugee policies in European countries motivate aspirations to move from the current country of residence. This finding has two implications regarding migration aspirations based on opportunities and obstacles. First, obstacles at borders per se do not determine migration aspirations. Plus, risks of border crossings per se cannot predict change in migration decision-making. Second, this finding provides counterevidence to policymakers’ assumption that all migrants will eventually aspire to move onwards when borders are open, and only stricter border policies can stop migration.

Second, even when borders are open, and countries are welcoming, opportunities can amplify the aspiration to stay in the current country. For instance, when comparing the first and second treatments, we observe that employment opportunities strongly decrease the probability of recommending moving onward (see ). While the probability of moving onward is more than 60% in the first treatment [unemployment, open border], it decreases to 37% with an employment opportunity. If we imagine a single male working in odd jobs in Turkey, an employment opportunity including a secured work permit would significantly reinforce aspiration to stay. Thus, the findings support Hypothesis 2, indicating that employment opportunities motivate aspirations to stay in the current country of residence. We argue that relatively open border policies for migrants do not necessarily feed the aspiration to move. The employment opportunities generate a significant difference between aspirations to stay and move, and are more determinant in forming migration aspirations than border externalization policies.

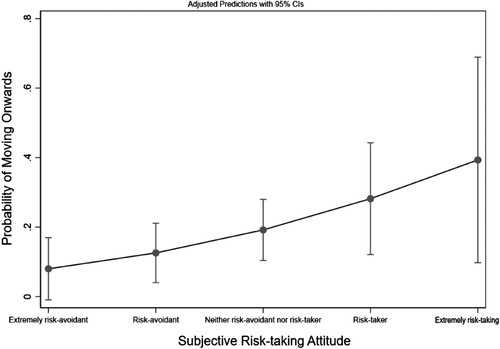

We conducted the second logistic regression by taking risk-taking attitudes as a moderator (see Model 2). shows the predicted probability of the move aspiration when there are no employment opportunities in the current place and when borders are closed, moderated by subjective risk-taking. We assume that these are the conditions under which only risk-taking migrants would recommend moving onward. Hence, the results show that recommending moving onward significantly increases depending on to what extent participants are risk-avoidant or risk-taking. As risk-taking attitudes increases, the probability of moving to another country increases from 8% to 40% when borders are closed, and our hypothetical person is unemployed. Thus, we can confirm Hypothesis 3, namely that as the tendency to take risks increases, the impact of border closures on the aspiration to move onward decreases.

Figure 2. Predicted probability of the ‘Move Aspiration’ of ‘Unemployment and Border Closures’ vignette moderated by subjective risk-taking.

The lack of employment opportunities prime plays a significant role in understanding the aspiration to move onward when the borders are risky to cross. Respondents provided with the unemployment and border closures prime are significantly more likely to recommend moving onward when they are more willing to take risks in general (see ). This finding implies that strict border policies may discourage some migrants from onward migration but do not deter every migrant on the move in the same manner. We can explain this variation by personal attitudes towards risk-taking. If we imagine an unemployed risk-taking migrant whose family is dependent on the money they send, border control policies would not be deterring. The lack of employment opportunities in the country of residence could be highly unacceptable for risk-taking migrants who aspire to move onward even when border crossing is dangerous. Hence, structural factors, opportunities, and/or border closures cannot be separated from individual characteristics in general, and risk-taking attitudes in particular, in migration decision-making.

Conclusion

This study examined factors influencing secondary migration aspirations in forced displacement contexts. Through an online survey experiment, our findings indicate that simply opening borders and implementing welcoming policies do not necessarily incentivize all migrants to consider moving onward. Instead, legal employment opportunities are perceived as preferable to migrating to EU countries, even when border conditions are relatively safe. Additionally, our results highlight the role of individual differences in risk-taking attitudes in determining whether migrants recommend moving or staying. Specifically, migrants with a higher inclination for risk-taking are less deterred by border closures and are more likely to consider moving onward.

Our findings carry significant implications for policy-making, ethical considerations, and analytical approaches. First, there is a growing demand for evidence-based migration policies, as many responses to undocumented migration tend to be reactive and driven by public discontent (Massey et al. Citation2016). Especially in the current European context, policymakers are increasingly inclined to implement externalization policies to deter people on the move (Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2019; Cobarrubias et al. Citation2023). De Haas (Citation2023) makes a similar critique, drawing on historical examples to demonstrate that border restrictions are counter-productive. He argues that such restrictions increase the costs associated with migration, thereby leading to a rise in irregular entry and stay. Additionally, he suggests that these restrictions disrupt circulation and diminish returns. In line with existing studies, our study emphasizes the need for more research that collects evidence on the effectiveness of different migration and development policy options. We aim to stimulate a discussion on how survey experiments, which capture the perspectives of migrants, can contribute to building this evidence base.

Secondly, our findings have political and ethical implications concerning the allocation of limited public resources for migration control. The relative effectiveness of employment opportunities in increasing aspirations to stay informs policymakers about where they can strategically invest their resources. We argue that investing in employment opportunities is a more ethical, humane, and sustainable approach than solely focusing on border controls or externalizing such controls to third countries. However, it is essential to exercise caution in implementing this policy recommendation, as further evidence is necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of various policies. Overall, our study highlights the importance of evidence-based policymaking, ethical considerations in resource allocation, and the potential of survey experiments to inform migration policy discussions.

Third, from an analytical perspective, our analysis raises the need for further research to explore why it is crucial to incorporate risk-taking attitudes into migration aspirations literature. As demonstrated in our research, when migrants’ risk-taking attitudes are taken into consideration, the generalizability of the effectiveness of border externalization policies for all migrants living under similar conditions becomes questionable. By revealing that the onward migration aspirations of Syrian migrants are significantly influenced by their subjective risk-taking attitudes, we challenge the assumption that border closures effectively deter every migrant. Hence, we suggest incorporating risk-taking attitudes into the analysis of micro-level factors that impact migration aspirations (Carling Citation2019). Further research in this area would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the complexities involved in migration aspirations and abilities taking into account variations at the individual level.

Our research has some limitations. First, the subjective risk attitude is a self-reported measurement, which can be influenced by individual biases or social desirability effects. Individuals may have difficulty accurately assessing their risk attitudes, especially if they lack experience in the specific domain being examined. Despite this shortcoming, research shows that subjective measurement of risk attitudes is still a valuable tool in predicting risk-taking behavior across different domains of research (Charness et al. Citation2013).

Another limitation is around the use of online surveys. Online surveys effectively reach difficult-to-reach populations (Ersanilli and van der Gaag, Citation2020), yet some population segments may not be adequately represented. For example, individuals without Internet or social media access may be less likely to participate in an online survey, which could lead to a biased sample. However, we lack publicly available demographic data on Syrian migrants living in Turkey. Hence, it is difficult to assess the potential impact of limitations on data representativeness (Elçi et al. Citation2021). Moreover, our experimental design presented the single-dimensional profile of a hypothetical migrant – a single male migrant working in odd jobs. We acknowledge that these scenarios do not reflect the heterogeneous profiles of Syrians in Turkey including dimensions such as being single versus with one’s family, gender, age, education or socio-economic background. However, the predominant image of border crossers is single male migrants. In this regard, we can justify our choice of the hypothetical profile of a migrant based on our research aims. We acknowledge these potential limitations and encourage further research with alternative methods of data collection that may account for different profiles among the population of interest.

Our study focused primarily on the individual-level factors influencing migration aspirations of Syrian migrants in Turkey. One important limitation is that we did not explore the role of meso-level factors such as social networks, which prior research suggests significantly impacts migration aspirations (Della Puppa and King Citation2019; McIlwaine Citation2012; Müller Funk Citation2019). Social networks can influence destination choices and adaptation to a new country (Müller Funk Citation2019). Future research can address this gap by examining how social networks, or more specifically, transnational social ties, shape the destination choices, migration aspirations, or, their perceptions about onward migration in forced migration contexts. By analyzing these connections, we can gain a more nuanced understanding of the decision-making process for migrants at different levels of analysis.

Finally, our data was collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, which also affected border controls. Thus, the pandemic might have added another layer impeding migration aspirations to move on. More research should be conducted in the post-COVID-19 period on this topic. We hope that the findings of this survey experiment, which was staged in Turkey, will have implications for similar contexts, where opportunities for migrants are scarce, out-migration is risky, and international cooperation on the ‘containment’ of refugee flows is high.

The data used in this research is part of a larger dataset collected for the ADMIGOV project, which received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 822625. Quantitative data is available upon request from the authors.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We are immensely grateful to all the participants who took the time to complete the questionnaire and share their experiences. The authors would like to thank Duygu Merve Uysal, participants of the Midwest Political Science Association 78th Annual Conference, participants of the IMISCOE 2023 ‘New Data and Measurements on Migration’ session, participants of the Politicologenetmaal 2023 methods workshop, our collaborators in the ADMIGOV project, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Turkey does not offer any long-term solutions for Syrian migrants, and the overwhelming majority of them have a temporary legal status. While official numbers indicate that over 200,000 Syrians received Turkish citizenship (see: https://www.diken.com.tr/soylu-vatandaslik-alan-suriyeli-sayisi-200-bin-950/), an overwhelming majority of Syrians have a dubious legal status. The Regulation on Temporary Protection grants access to public services such as healthcare and education, but it does not grant the right to work in the formal labor market. Despite the provision of basic services, many Syrians face obstacles on a daily basis due to informal employment, scarce livelihood opportunities, rising living costs, and widespread anti-immigration attitudes in society (Baban, Ilcan, and Rygiel Citation2017). To avoid confusion with the legal status of refugees, this paper will refer to Syrians with temporary protection as ‘migrants’.

2 The PMM website https://en.goc.gov.tr/temporary-protection27 Last accessed: 20 May 2023.

3 In our study, we employ the term ‘externalization’ as a comprehensive concept encompassing various practices, such as border closures, controlling smuggling networks, or border guards’ attitudes towards refugees. Although our research does not specifically delve into distinct forms of border externalization policies, it aligns with and contributes to the existing literature in this field. Acknowledging the differences between the concepts of border closures and externalization, we use both terms interchangeably.

4 See Pallister-Wilkins (Citation2019) for a critical view on the representation of migration journeys: https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/walking-not-flowing-the-migrant-caravan-and-the-geoinfrastructuring-of-unequal-mobility.

5 See Work Permits of Foreigners 2021, published by the Turkish Ministry of Labor https://www.csgb.gov.tr/media/90062/yabanciizin2021.pdf.

6 The survey experiment was part of a broader study, ADMIGOV, on migration aspirations among displaced communities in Turkey.

7 Initiated by the EU-Turkey Statement of March 2016, the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN) is a major cash transfer program funded by the EU to improve the living conditions of refugees in Turkey.

8 The first treatment priming for the lack of employment opportunities in the current country of residence and the lack of obstacles on borders does not significantly differ from the control group. In Turkey, being employed often means working in odd jobs, which places many migrants in unbearable and uncertain situations, blurring the line between unemployment and insecure employment. Therefore, the migrant experience described in the control group and in the first treatment may have been perceived similarly by the participants.

References

- Adamson, F. B., and G. Tsourapas. 2019. “The Migration State in the Global South: Nationalizing, Developmental, and Neoliberal Models of Migration Management.” International Migration Review 54 (3): 853–882. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918319879057.

- Alden, E. 2017. “Is Border Enforcement Effective? What we Know and What it Means.” Journal on Migration and Human Security 5 (2): 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/233150241700500213.

- Alpes, M. J. 2014. “Imagining a Future in ‘Bush’: Migration Aspirations at Times of Crisis in Anglophone Cameroon.” Identities 21 (3): 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2013.831350.

- Aydın Düzgit, S., F. Keyman, and K. S. Biehl Öztuzcu. 2019. Changing Parameters of Migration Cooperation: beyond the EU-Turkey Deal. Istanbul Policy Center (IPC). https://research.sabanciuniv.edu/id/eprint/40170/1/changing-parameters-of-migration-cooperation-beyond-the-eu-turkey-deal-0a0024-1.pdf.

- Baban, F., S. Ilcan, and K. Rygiel. 2017. “Syrian Refugees in Turkey: Pathways to Precarity, Differential Inclusion, and Negotiated Citizenship Rights.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (1): 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1192996.

- Bah, T. L., and C. Batista. 2018. Understanding Willingness to Migrate Illegally: Evidence from a Lab in the Field Experiment. Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Faculdade de Economia, NOVAFRICA. https://novafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/TijanBah_Understanding-willingness-to-migrate-illegally_Bah_Batista.pdf.

- Barnett, J., and G. M. Breakwell. 2001. “Risk Perception and Experience: Hazard Personality Profiles and Individual Differences.” Risk Analysis 21 (1): 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/0272-4332.211099.

- Becerra, D., M. Gurrola, C. Ayón, D. Androff, J. Krysik, K. Gerdes, L. Moya-Salas, and E. Segal. 2010. “Poverty and Other Factors Affecting Migration Intentions among Adolescents in Mexico.” Journal of Poverty 14 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875540903272801.

- Bélanger, D., and C. Saracoglu. 2020. “The Governance of Syrian Refugees in Turkey: The State-Capital Nexus and its Discontents.” Mediterranean Politics 25 (4): 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2018.1549785.

- Belloni, M. 2016. “Refugees as Gamblers: Eritreans Seeking to Migrate Through Italy.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 14 (1): 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2015.1060375.

- Boccagni, P. 2017. “Aspirations and the Subjective Future of Migration: Comparing Views and Desires of the ‘Time Ahead’ Through the Narratives of Immigrant Domestic Workers.” Comparative Migration Studies 5 (4): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-016-0047-6.

- Carling, J. 2002. “Migration in the Age of Involuntary Immobility: Theoretical Reflections and Cape Verdean Experiences.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 28 (1): 5–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830120103912.

- Carling, J. 2014. “The Role of Aspirations in Migration.” Paper presented at the Determinants of International Migration, International Migration Institute, Oxford. https://jorgencarling.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/carling-2014-the-role-of-aspirations-in-migration-2014-07.pdf.

- Carling, J. 2019. “Measuring Migration Aspirations and Related Concepts” (MIGNEX Deliverable 2.3.). MIGNEX Website. https://migration.prio.org/utility/DownloadFile.ashx?id=157&type=publicationfile.

- Carling, J., and F. Collins. 2018. “Aspiration, Desire and Drivers of Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 909–926. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384134.

- Carling, J., and K. Schewel. 2018. “Revisiting Aspiration and Ability in International Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 945–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384146.

- Charness, G., U. Gneezy, and A. Imas. 2013. “Experimental Methods: Eliciting Risk Preferences.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 87:43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2012.12.023.

- Chindarkar, N. 2014. “Is Subjective Well-Being of Concern to Potential Migrants from Latin America?” Social Indicators Research 115 (1): 159–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0213-7.

- Cobarrubias, S., P. Cuttitta, M. Casas-Cortés, M. Lemberg-Pedersen, N. El Qadim, B. İşleyen, S. Fine, C. Giusa, and C. Heller. 2023. “Interventions on the Concept of Externalisation in Migration and Border Studies.” Political Geography 105:102911. 10.1016j.polgeo.2023.102911.

- Collyer, M. 2006. States of Insecurity: Consequences of Saharan Transit Migration (Working Paper No.31). Centre on Migration, Policy and Society, Oxford. https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/WP-2006-031-Collyer_Saharan_Transit_Migration.pdf.

- Collyer, M., F. Düvell, and H. de Haas. 2012. “Critical Approaches to Transit Migration.” Population, Space and Place 18 (4): 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.630.

- Côté-Boucher, K., F. Infantino, M. B. Salter, K. Côté-Boucher, F. Infantino, and M. B. Salter. 2014. “Border Security as Practice: An Agenda for Research.” Security Dialogue 45 (3): 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010614533243.

- Danış, D. 2021. The Fifth Year of the EU-Turkey Statement in the Pendulum of Externalization-Instrumentalization. Retrieved from Association for Migration Research (GAR), Istanbul. https://gocarastirmalaridernegi.org/attachments/article/226/EU-Turkey%20Statement%20_DANIS.pdf.

- Dávila, A., J. A. Pagán, and G. Soydemir. 2002. “The Short-Term and Long-Term Deterrence Effects of INS Border and Interior Enforcement on Undocumented Immigration.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 49 (4): 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(02)00010-0.

- De Haas, H. 2021. “A Theory of Migration: The Aspirations-Capabilities Framework.” Comparative Migration Studies 9 (8): 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4.

- De Haas, H. 2023. How Migration Really Works: A Factful Guide to the Most Divisive Issue in Politics. London: Penguin.

- De Haas, H., S. Vezzoli, and M. Villares-Varela. 2019. Opening the Floodgates?: European Migration under Restrictive and Liberal Border Regimes 1950–2010 (MADE Project Paper No.6). International Migration Institute Network (IMI). https://www.migrationinstitute.org/publications/opening-the-floodgates-european-migration-under-restrictive-and-liberal-border-regimes-1950-2010.

- Della Puppa, F., and R. King. 2019. “The New ‘Twice Migrants’: Motivations, Experiences and Disillusionments of Italian-Bangladeshis Relocating to London.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (11): 1936–1952. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1438251.

- Detlefsen, L., T. Heidland, and C. Schneiderheinze. 2022. What Explains People’s Migration Aspirations? Experimental Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. SSRN Working Paper. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4238957.

- Dimitriadis, I. 2021. “Onward Migration Aspirations and Transnational Practices of Migrant Construction Workers Amidst Economic Crisis: Exploring New Opportunities and Facing Barriers.” International Migration 59 (6): 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12803.

- Donini, A., A. Monsutti, and G. Scalettaris. 2016. Afghans on the Move: Seeking Protection and Refuge in Europe (Global Migration Research Paper No.17). Graduate Institute Geneva. https://www.asyl.at/files/93/25-afghans_on_the_move.pdf.

- Dubow, T., and K. Kuschminder. 2021. “Family Strategies in Refugee Journeys to Europe.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (4): 4262–4278. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feab018.

- Düvell, F., D. Schiefer, A. Z. Sağıroğlu, and L. Mann. 2021. How Many Syrian Refugees in Turkey Want to Migrate to Europe and Can Actually Do So?: Results of a Survey Among 1,900 Syrians (DeZIM Research Notes 5). Retrieved from German Center for Integration and Migration Research (DeZIM). https://www.dezim-institut.de/fileadmin/Publikationen/Research_Notes/DeZIM_Research_Notes_05_210323_3_RZ_web.pdf.

- Elçi, E., E. Kirisçioglu, and A. Üstübici. 2021. “How Covid-19 Financially Hit Urban Refugees: Evidence from Mixed-Method Research with Citizens and Syrian Refugees in Turkey.” Disasters 45 (S1): S240–S263. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12498.

- Elliott, M. R., and R. Valliant. 2017. “Inference for Nonprobability Samples.” Statistical Science 32 (2): 249–264, 216. https://doi.org/10.1214/16-STS598.

- El Qadim, N. 2017. “The Symbolic Meaning of International Mobility: Eu–Morocco Negotiations on Visa Facilitation.” Migration Studies 6 (2): 279–305. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnx048.

- Ersanilli, E., and M. van der Gaag. 2020. Data Report: Online Surveys. Wave 1 (MOBILISE Working Papers version 5). SocArXiv: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/79gca/.

- Esteves, A. I. P., M. L. C. d. S. Fonseca, and J. d. S. M. Malheiros. 2018. “Labour Market Integration of Immigrants in Portugal in Times of Austerity: Resilience, in Situ Responses and Re-Emigration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (14): 2375–2391. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1346040.

- Ewers, M. C., and B. Shockley. 2018. “Attracting and Retaining Expatriates in Qatar During an Era of Uncertainty: Would you Stay or Would you Go?” Population, Space and Place 24 (5): e2134. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2134.

- Flahaux, M.-L., and S. Vezzoli. 2017. “Examining the Role of Border Closure and Post-Colonial Ties in Caribbean Migration.” Migration Studies 6 (2): 165–186. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnx034.

- Frontex (European Border and Coast Guard Agency). 2023. “Migratory Routes-Eastern Mediterrenean Route.” https://frontex.europa.eu/what-we-do/monitoring-and-risk-analysis/migratory-routes/eastern-mediterranean-route/.

- Gaines, B. J., J. H. Kuklinski, and P. J. Quirk. 2007. “The Logic of the Survey Experiment Reexamined.” Political Analysis 15 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpl008.

- Gathmann, C. 2008. “Effects of Enforcement on Illegal Markets: Evidence from Migrant Smuggling Along the Southwestern Border.” Journal of Public Economics 92 (10–11): 1926–1941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.04.006.

- Geiger, M., and A. Pécoud. 2010. “The Politics of International Migration Management.” In The Politics of International Migration Management. Migration, Minorities and Citizenship, edited by M. Geiger and A. Pécoud, 1–20. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Groenewold, G., B. de Bruijn, and R. Bilsborrow. 2012. “Psychosocial Factors of Migration: Adaptation and Application of the Health Belief Model.” International Migration 50 (6): 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2012.00781.x.

- Hager, A. 2021. “What Drives Migration to Europe? Survey Experimental Evidence from Lebanon.” International Migration Review 55 (3): 929–950. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918320988662.

- Helbling, M., and S. Morgenstern. 2023. “Migration Aspirations and the Perceptions of the Political, Economic and Social Environment in Africa.” International Migration 0 (0): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.13148.

- Hernández-Carretero, M., and J. Carling. 2012. “Beyond ‘Kamikaze Migrants’: Risk Taking in West African Boat Migration to Europe.” Human Organization 71 (4): 407–416. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.71.4.n52709742v2637t1.

- Hyndman, J., and A. Mountz. 2008. “Another Brick in the Wall? Neo-Refoulement and the Externalization of Asylum by Australia and Europe.” Government and Opposition 43 (2): 249–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2007.00251.x.

- İşleyen, B. 2018a. “Transit Mobility Governance in Turkey.” Political Geography 62:23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.09.017.

- İşleyen, B. 2018b. “Turkey’s Governance of Irregular Migration at European Union Borders: Emerging Geographies of Care and Control.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36 (5): 849–866. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818762132.

- İşleyen, B., and N. E. Qadim. 2023. “Border and Im/Mobility Entanglements in the Mediterranean: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 41 (1): 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/02637758231157264.

- Karadağ, S. 2019. “Extraterritoriality of European Borders to Turkey: An Implementation Perspective of Counteractive Strategies.” Comparative Migration Studies 7 (1): 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0113-y.

- Karadağ, S., and A. Üstübici. 2021. Protection during Pre-pandemic and COVID-19 Periods in Turkey (AdMiGov Deliverable 4.2). Istanbul. http://admigov.eu/upload/Deliverable_42_Protection_COVID19_Turkey_Karadag_Ustubici.pdf.

- Kaytaz, E. S. 2016. “Afghan Journeys to Turkey: Narratives of Immobility, Travel and Transformation.” Geopolitics 21 (2): 284–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2016.1151874.

- Kipp, D., and A. Koch. 2018. “Looking for External Solutions: Instruments, Actors, and Strategies for European Migration Cooperation with African Countries.” In Profiteers of Migration? Authoritarian States in Africa and European Migration Management, edited by Anne Koch, Annette Weber, and I. Werenfels, 9–21. Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik.

- Kiriscioglu, E., and A. Ustubici. 2023. “‘At Least, at the Border, I Am Killing Myself by My Own Will’: Migration Aspirations and Risk Perceptions among Syrian and Afghan Communities.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2023.2198485.

- Kuschminder, K. 2018. “Afghan Refugee Journeys: Onwards Migration Decision-Making in Greece and Turkey.” Journal of Refugee Studies 31 (4): 566–587. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fex043.

- Kuschminder, K., J. de Bresser, and M. Siegel. 2015. Irregular Migration Routes to Europe and Factors Influencing Migrants’ Destination Choices. Maastricht Graduate School of Governance, UNU-MERIT. https://migration.unu.edu/publications/reports/irregular-migration-routes-to-europe-and-factors-influencing-migrants-destination-choices.html.

- Kuschminder, K., T. Dubow, A. Icduygu, A. Ustubici, E. Kiriscioglu, G. Engbersen, and O. Mitrovic. 2019. Decision Making on the Balkans Route and the EU-Turkey Statement. MiReKoc website. https://mirekoc.ku.edu.tr/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2916_Volledige_Tekst_tcm28-413430.pdf.

- Maâ, A. 2023. “Autonomy of Migration in the Light of Deportation. Ethnographic and Theoretical Accounts of Entangled Appropriations of Voluntary Returns from Morocco.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 41 (1): 92–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/02637758221140885.

- Massey, D. S., K. A. Pren, and J. Durand. 2016. “Why Border Enforcement Backfired.” American Journal of Sociology 121 (5): 1557–1600. https://doi.org/10.1086/684200.

- Mata-Codesal, D. 2018. “Is it Simpler to Leave or to Stay put? Desired Immobility in a Mexican Village.” Population, Space and Place 24 (4): e2127. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2127.

- McDermott, R. 2002. “Experimental Methods in Political Science.” Annual Review of Political Science 5 (1): 31–61. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.5.091001.170657.

- McIlwaine, C. 2012. “Constructing Transnational Social Spaces among Latin American Migrants in Europe: Perspectives from the UK.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 5 (2): 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsr041.

- McKenzie, D., and D. Yang. 2012. “Experimental Approaches in Migration Studies.” In Handbook of Research Methods in Migration, edited by C. Vargas-Silva, 249–269. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Müller-Funk, L., A. Üstübici, and M. Belloni. 2023. “Daring to Aspire: Theorising Aspirations in Contexts of Displacement and Highly Constrained Mobility.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2208291.

- Müller Funk, L. 2019. Adapting to Staying, or Imagining Futures Elsewhere: Migration Decision-Making of Syrian Refugees in Turkey (International Migration Institute (IMI) No. 155). https://www.migrationinstitute.org/publications/adapting-to-staying-or-imagining-futures-elsewhere-migration-decision-making-of-syrian-refugees-in-turkey.

- Pagogna, R., and P. Sakdapolrak. 2023. “How Migration Information Campaigns Shape Local Perceptions and Discourses of Migration in Harar City, Ethiopia.” International Migration 61:142–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.13112.

- Pallister-Wilkins, P. 2019. "Walking, Not Flowing: The Migrant Caravan and the Geoinfrastructuring of Unequal Mobility." Society and Space, November 18, 2019. https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/walking-not-flowing-the-migrant-caravan-and-the-geoinfrastructuring-of-unequal-mobility.

- Petzold, K. 2017. “Mobility Experience and Mobility Decision-Making: An Experiment on Permanent Migration and Residential Multilocality.” Population, Space and Place 23 (8): e2065. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2065.

- Pötzschke, S., and B. Weiß. 2021. Realizing a Global Survey of Emigrants through Facebook and Instagram. OSF Preprints. https://osf.io/y36vr.

- Presidency of Migration Management (PMM). 2023. “Irregular Migration Statistics.” https://en.goc.gov.tr/irregular-migration.

- Pries, L., and B. S. Zülfikar Savci. 2023. “Between Humanitarian Assistance and Externalizing of EU Borders: The EU-Turkey Deal and Refugee Related Organizations in Turkey.” Journal on Migration and Human Security 11 (1): 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/23315024231156381.

- Roth, B. J., and C. S. Hartnett. 2018. “Creating Reasons to Stay? Unaccompanied Youth Migration, Community-Based Programs, and the Power of “Push” Factors in El Salvador.” Children and Youth Services Review 92:48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.01.026.

- Sahin Mencutek, Z., and A. J. Nashwan. 2021. “Perceptions About the Labor Market Integration of Refugees: Evidences from Syrian Refugees in Jordan.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 22 (2): 615–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00756-3.

- Schapendonk, J., M. Bolay, and J. Dahinden. 2021. “The Conceptual Limits of the ‘Migration Journey’. De-Exceptionalising Mobility in the Context of West African Trajectories.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (14): 3243–3259. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1804191.

- Schiefer, D., F. Düvell, and A. Z. Sağıroğlu. 2023. “Migration Aspirations in Forced Transnational Families: The Case of Syrians in Turkey.” Migration Studies 0 (0): 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnad020.

- Sorensen, T., and C. Carrion-Flores. 2007. The Effects of Border Enforcement on Migrants’ Border Crossing Choices: Diversion or Deterrence? Centre for Research & Analysis of Migration (CReAM): https://cream-migration.org/files/CarrionSorensen.pdf.

- Stock, I., A. Üstübici, and S. U. Schultz. 2019. “Externalization at Work: Responses to Migration Policies from the Global South.” Comparative Migration Studies 7 (48): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0157-z.

- Strasser, S., and E. E. Tibet. 2019. “The Border Event in the Everyday: Hope and Constraints in the Lives of Young Unaccompanied Asylum Seekers in Turkey.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (2): 354–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1584699.

- Sunderland, J. 2022. “Endless Tragedies in the Mediterranean Sea.” Human Rights Watch, September 13. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/09/13/endless-tragedies-mediterranean-sea.

- Syed Zwick, H. 2022. “Onward Migration Aspirations and Destination Preferences of Refugees and Migrants in Libya: The Role of Persecution and Protection Incidents.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (15): 3705–3724. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2031923.

- Tazzioli, M. 2016. “Border Displacements. Challenging the Politics of Rescue Between Mare Nostrum and Triton.” Migration Studies 4 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnv042.

- Tekin, BÇ. 2022. “Bordering Through Othering: On Strategic Ambiguity in the Making of the EU-Turkey Refugee Deal.” Political Geography 98:102735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102735.

- Topak, Ö. 2014. “The Biopolitical Border in Practice: Surveillance and Death at the Greece-Turkey Borderzones.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32 (5): 815–833. https://doi.org/10.1068/d13031p.

- Tsourapas, G. 2019. “The Syrian Refugee Crisis and Foreign Policy Decision-Making in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey.” Journal of Global Security Studies 4 (4): 464–481. https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogz016.

- Ulusoy, O., and H. Battjes. 2017. Situation of Readmitted Migrants and Refugees from Greece to Turkey under the EU-Turkey Statement (VU Amsterdam Migration Law Series No.15). Amsterdam Centre of Migration and Refugee Law. https://acmrl.org/situation-of-readmitted-migrants-and-refugees-from-greece-to-turkey-under-the-eu-turkey-statement/.

- Üstübici, A. 2019. “The Impact of Externalized Migration Governance on Turkey: Technocratic Migration Governance and the Production of Differentiated Legal Status.” Comparative Migration Studies 7 (46): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0159-x.

- Üstübici, A., and E. Elçi. 2022. “Aspirations among Young Refugees in Turkey: Social Class, Integration and Onward Migration in Forced Migration Contexts.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2022.2123433.

- Üstübici, A., E. Kirişçioğlu, and E. Elçi. 2021. Migration and Development: Measuring Migration Aspirations and the Impact of Refugee Assistance in Turkey (AdMiGov Deliverable 6). https://admigov.eu/upload/Deliverable_61_Ustubici_Kiriscioglu_Elci_2021_Aspirations_Turkey.pdf.

- Van Hear, N. 2006. ““I Went as Far as My Money Would Take Me”: Conflict, Forced Migration and Class.” In Forced Migration and Global Processes: A View from Forced Migration Studies, edited by F. Crepeau, D. Nakache, M. Collyer, N. Goetz, A. Hansen, R. Modi, A. Nadig, S. Spoljar-Vrzina, and M. Willigen, 125–158. Oxford: Lexington Books.

- Vezzoli, S. 2021. “How do Borders Influence Migration? Insights from Open and Closed Border Regimes in the Three Guianas.” Comparative Migration Studies 9 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-020-00213-1.

- Walters, W. 2011. “Foucault and Frontiers: Notes on the Birth of the Humanitarian Border.” In Governmentality, edited by U. Bröckling, S. Krasmann, and T. Lemke, 138–164. New York, NY: Routledge..

- Weber, E. U., A.-R. Blais, and N. E. Betz. 2002. “A Domain-Specific Risk-Attitude Scale: Measuring Risk Perceptions and Risk Behaviors.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 15 (4): 263–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.414.

- Welfens, N., and Y. Bekyol. 2021. “The Politics of Vulnerability in Refugee Admissions Under the EU-Turkey Statement.” Frontiers in Political Science 3 (16): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.622921.

- Williams, A. M., and V. Baláž. 2014. “Mobility, Risk Tolerance and Competence to Manage Risks.” Journal of Risk Research 17 (8): 1061–1088. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2013.841729.