Abstract

Background: To assess the cost-effectiveness of ceritinib vs alternatives in patients who discontinue treatment with crizotinib in anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive (ALK+) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) from a Canadian public healthcare perspective.

Methods: A partitioned survival model with three health states (stable, progressive, and death) was developed. Comparators were chosen based on reported utilization from a retrospective Canadian chart study; comparators were pemetrexed, best supportive care (BSC), and historical control (HC). HC comprised of all treatment alternatives reported. Progression-free survival and overall survival for ceritinib were estimated using data reported from single-arm clinical trials (ASCEND-1 [NCT01283516] and ASCEND-2 [NCT01685060]). Survival data for comparators were obtained from published clinical trials in a NSCLC population and from a Canadian retrospective chart study. Parametric models were used to extrapolate outcomes beyond the trial period. Drug acquisition, administration, resource use, and adverse event (AE) costs were obtained from databases. Utilities for health states and disutilities for AEs based on EQ-5D were derived from literature. Incremental costs per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained were estimated. Univariate and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed.

Results: Over 4 years, ceritinib was associated with 0.86 QALYs and total direct costs of $89,740 for the post-ALK population. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was $149,117 comparing ceritinib vs BSC, $80,100 vs pemetrexed, and $104,436 vs HC. Additional scenarios included comparison to docetaxel with an ICER of $149,780 and using utility scores reported from PROFILE 1007, with a reported ICER ranging from $67,311 vs pemetrexed to $119,926 vs BSC. Due to limitations in clinical efficacy input, extensive sensitivity analyses were carried out whereby results remained consistent with the base-case findings.

Conclusion: Based on the willingness-to-pay threshold for end-of-life cancer drugs, ceritinib may be considered as a cost-effective option compared with other alternatives in patients who have progressed or are intolerant to crizotinib in Canada.

Introduction

Lung cancer has one of the highest fatality outcomes, accounting for 27% of all cancer-related deaths in Canada; one in 12 males and one in 14 females are diagnosed with lung cancer in their lifetimeCitation1. The 5-year survival for lung cancer in Canada is 14% in males and 20% in femalesCitation2. Approximately 85% of all cases related to lung cancer are non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)Citation3; ∼2–7% of patients with NSCLC have rearrangements in anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene and are considered as ALK-positive (ALK+)Citation4,Citation5. Patients with ALK + NSCLC typically present at a more advanced clinical stage at diagnosis than non-ALK sub-typesCitation6,Citation7, and in the absence of ALK-targeted therapy, have very poor prognosis and survival outcomesCitation6,Citation8.

ALK-rearranged tumors depend on ALK for growth and survival and show marked sensitivity to ALK inhibitors such as crizotinib. In patients with ALK + NSCLC, the recommended first-line treatment is crizotinibCitation3. Crizotinib is indicated as a monotherapy for patients with ALK + locally advanced (not amenable to curative therapy) or metastatic NSCLCCitation9. In Canada, crizotinib is provincially funded for first and second-line monotherapy in patients with ALK + NSCLC who have received prior chemotherapyCitation10,Citation11. Despite initial responses to crizotinib, almost all patients acquire resistance and progress within the first year of treatmentCitation12.

Ceritinib is an oral, small-molecule, ATP-competitive, tyrosine kinase inhibitor of ALKCitation13. Ceritinib has been approved by Health Canada in March 2015 and is indicated as monotherapy in patients with ALK + locally advanced (not amenable to curative therapy) or metastatic NSCLC who have progressed on or who were intolerant to crizotinibCitation14. Ceritinib demonstrated substantial clinical activity in patients with NSCLC with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 18.4 months in ALK inhibitor-naïve patients (95% CI =11.3, not estimable [NE]), 6.9 months in patients previously treated with ALK inhibitor (95% CI =6.8–9.7) based on the results of ASCEND-1, a single-arm studyCitation15 (NCT01283516). In patients previously treated with an ALK inhibitor, the median overall survival (OS) was 16.7 months (95% CI =14.8–NE), the 12 months OS rate was 67.2% (95% CI =58.9–74.1)Citation16. The clinical efficacy of ceritinib was also assessed in a phase 2, single-arm trial (NCT01685060). Patients had received 1–3 lines of cytotoxic chemotherapy, and then were treated with crizotinib, and subsequently experienced disease progression. Patients treated with ceritinib had a median PFS of 5.7 months by investigator review (IR) (95% CI =5.4–7.6) and 7.2 months by Blinded Independent Review Committee (BIRC) (95% CI =5.4–9.0)Citation17. Median overall survival (OS) was 14.9 months (95% CI =13.5–NE)Citation17. Both studies required documentation of confirmed ALK + status by the Vysis ALK break apart Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) test and did not require any further ALK testing for study inclusion.

The aim of this study was to assess the cost-effectiveness of ceritinib vs alternatives in patients with ALK + NSCLC who have discontinued treatment with crizotinib from a Canadian healthcare perspective.

Patients and methods

A partitioned survival model was developed in Excel (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA) to compare ceritinib vs other alternatives in patients with ALK + NSCLC who were previously treated with crizotinib. Partitioned survival analysis captures the progressive nature of the disease and reflects the main outputs produced by clinical trials (i.e. PFS and OS).

Patient population and treatment interventions

The population assumed in the model corresponds to patients receiving treatment with ceritinib after prior use of crizotinib (ASCEND-1, n = 163 and ASCEND-2, n = 140)Citation15,Citation17. The model assumed that all patients started the treatment at age 53, the median age of patients in the ASCEND-1 trial. Body surface area (BSA) was used to estimate the doses needed for chemotherapy (mean BSA was 1.79/m2)Citation18.

Comparators were included based on the treatment pattern reported in a retrospective Canadian cohort study of patients with ALK + NSCLC previously treated with crizotinibCitation19. Treatment patterns, resource utilization, and outcomes were retrieved from six institutions across Canada (two in British Columbia, three in Ontario, and one in Quebec). A total of 97 were included, of whom, 49 patients were crizotinib failures, nine were crizotinib naïve, and 39 patients were receiving ongoing treatment with crizotinib. The most frequently reported treatment options were ceritinib, no treatment, and pemetrexed monotherapy in patients who failed crizotinib (n = 49)Citation20. For the purpose of the cost-effectiveness analysis, the most appropriate comparators were determined to be best supportive care (BSC), pemetrexed monotherapy, and an additional comparator accounting for all non-ceritinib treatments termed as historical control (HC) were included. Historical control included patients who received no further active treatment termed as BSC, pemetrexed monotherapy, and combinations of chemotherapy. Based on previously reported cost-effectiveness of crizotinib in CanadaCitation21, a comparison to docetaxel was included as a sensitivity analysis.

Model structure

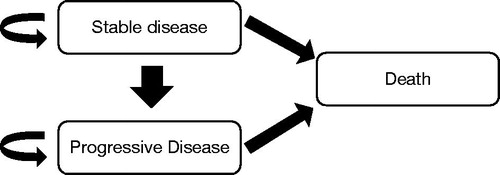

The model considered the following three mutually exclusive health states: stable disease (SD), progressive disease (PD) and death (D), depicting the natural history of the disease (). Patients were assumed to be in the SD state if they have not yet progressed or transitioned to the PD state or death. At the start of treatment, it was assumed that all patients had entered the SD state. The proportion of patients in the PD state at each cycle was calculated as the difference between the proportion of patients who died and the proportion of patients who would remain in the SD state. Patients in the PD state could either remain in the PD state or transition to death.

The decision model was developed with a lifetime time horizon, defined up until all patients died. However, noting the potential short survival of ALK + NSCLC patients, the time horizon was set at 4 years in the base case. A cycle with an average of 30.44 days was considered to be sufficient to capture the complexities of the disease. Cost and health outcomes were discounted at 5% per annumCitation21. The analysis was conducted from the perspective of a Canadian healthcare payer, as such only direct medical costs were considered. All costs are reported in 2014 Canadian dollars.

Efficacy data

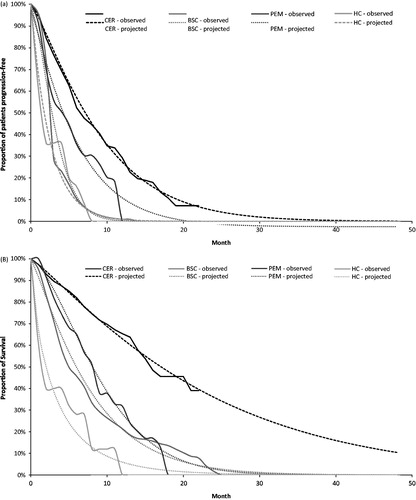

In the absence of a head-to-head randomized trial comparing ceritinib vs any other alternatives, transition probabilities for comparators were obtained from published clinical trials in ALK + NSCLC patients treated with crizotinib, the general NSCLC population, and from a Canadian retrospective cohort study of ALK + crizotinib-treated patients (). Parametric survival functions for PFS and OS were derived from a pooled patient population of ASCEND-1 and ASCEND-2 in patients previously treated with crizotinib. A total of 303 patients with ALK + NSCLC on ceritinib treatment and previously treated with crizotinib were included in the efficacy analysis (163 from ASCEND-1 and 140 from ASCEND-2). The median PFS of the pooled analysis was 6.7 months (95% CI =5.5–8.3) and the median OS was 15.6 months (95% CI =14.7–NE). The OS rate at 12 months was 65.4% (95% CI =60.0–71.3%). The pooled analysis was deemed appropriate as patients from ASCEND-1 and ASCEND-2 had similar baseline characteristics.

Table 1. Source of efficacy inputs.

For comparators, patient-level time-to-event data for PFS and OS were generated from published Kaplan–Meier (KM) curves using digitization softwareCitation22. Based on the extracted survival curves and the reported numbers of events and patients at risk at various time points, approximate individual patient data were generated using the approach described by Guyot et al.Citation23. It is assumed that the efficacy data inferred from the general NSCLC population and other reported studies of the ALK + population (PROFILE 1007) is applicable to patients with ALK + NSCLC who have failed treatment with crizotinib.

Proportional hazard models including Weibull, exponential, Gompertz, and accelerated failure time models including log-logistic and log-normal distributions were considered to extrapolate outcomes beyond the trial period. Functions were selected for inclusion in the economic model, based on the Akaike Information Criterion and Bayesian Information Criterion results, visual assessment of curve fit to the KM curves, and plausibility of the extrapolation.

Resource use and costs

Costs in stable state

The model included drug and drug administration costs (includes drug, drug administration, mean dose intensity, delivery for chemotherapy, and duration of treatment) and costs associated with resource utilization in the SD state (). The costs for chemotherapy and administration of intravenous (IV) drugs were derived from the dosing schedules reported in the regimen monographs from Cancer Care Ontario. Costs associated with IV administration included were based on duration of patient visit, nurse, pharmacy time, and physician monitoring as reported in Cancer Care Ontario regimen monographs. Costs associated with resource utilization (physician visits, laboratory, and radiologic tests) were retrieved from the Canadian cohort study. Costs in the BSC arm only included resource utilization costs and cost of pain management associated with palliative care.

Table 2. Summary of model inputs.

Costs in post-progression state

Post-progression resource use costs included physician visits, laboratory tests, and radiologic monitoring. No active treatment was considered in the post-progression state, except if patients received ceritinib. Costs associated with active treatment in post-progression state was inferred from the frequency of utilization in non-ceritinib treatment reported in the retrospective cohort study. As reported in ASCEND-1, 26.8% of patients received treatment post-discontinuation on ceritinib. However, due to limited details on dosing and dose schedule from clinical trial data, a weighted average was derived based on the frequency of active treatment utilization reported in the Canadian cohort studyCitation19. As such, active treatment in PD state included pemetrexed (17.6%), gemcitabine (8.8%), and the remaining was assumed to receive only BSC (73.6%). The costs of post-progression in the ceritinib arm were $3394 and were applied only once to patients who entered the PD state ().

Costs in death state

All patients who transitioned to the death state were assumed to incur a one-time cost of terminal care derived from a Canadian study and inflated to 2014 dollarsCitation24.

Costs of concomitant medications associated with active treatment

Costs of dexamethasone, NSAIDs, bisphosphonate, and morphine were included, based on recommended concomitant medications for chemotherapy. Additional costs associated with pemetrexed included the cost of folic acid at $0.23 per cycle.

Costs associated with adverse events

Incidence of grade 3 or 4 adverse events (AEs) (incidence ≥5%) for ceritinib was obtained from ASCEND-1Citation15 and for pemetrexed or docetaxel was obtained from Hanna et al.Citation25. A weighted average of pemetrexed, BSC, and platinum doubletCitation26 was used to derive the incidence of AEs associated with historical controls. Unit costs for AEs were obtained from the Ontario Case Costing initiative for 2011 costs and inflated to 2014 using Bank of Canada Consumer Price IndexCitation27. It was assumed that the costs associated with febrile neutropenia would be similar to neutropenia, as no recent Canadian costs were retrieved in the literature. Costs associated with alanine transaminase (ALT) elevation, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) elevation, blood alkaline phosphatase increased, and lipase increased were assumed to be $0, as these would be associated with dose interruption or reduction with the respective intervention.

Utilities

The model assumed that health utilities depend on health states and treatment received. Utilities were elicited from a quality-of-life study of advanced NSCLC patients in 25 hospitals across Europe, Canada, Australia, and Turkey. Utilities were reported by health states and by line of therapyCitation28. Quality-of-life was assessed using the EuroQoL questionnaire (EQ-5D) and the visual analog scale. To account for the effect of treatment response on utility, the utility for stable disease was adjusted for the overall response rate for each treatment arm. Utility associated with treatment response was estimated based on the utility for SD reported in Nafees et al.Citation31 multiplied by the ratio of treatment response state to SD state. The study by Nafees et al.Citation29 elicited utility values for different stages of NSCLC and different grade 3 and 4 AEs based on health states in a standard gamble interview of 100 individuals in the UK. Health states were generated by literature review and exploratory interviews with oncology experts and psychometric experts. Disutilities included were neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, hair loss, and rash.Citation29

Based on quality-of-life data reported in ASCEND-2, ceritinib was associated with continued maintenance of quality-of-life once patients discontinued on treatment with crizotinibCitation17. The model, therefore, considers an alternative scenario which included health utility scores derived from previous patients with ALK + NSCLC treated with crizotinib, as reported by Blackhall et al.Citation30.

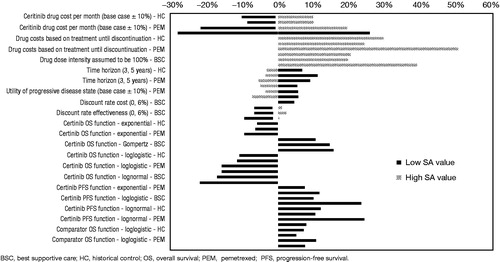

Sensitivity analysis

Model validation was carried out in 2-folds: (1) input data and coding were verified by experienced health economists; and (2) the model’s predictions for PFS and OS with ASCEND-1 and ASCEND-2 to ensure external validity. However, to test the robustness of the model, deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed. One-way sensitivity analyses were conducted by varying one parameter at a time. Time horizon was varied between 3–5 years and discount rates varied between 0–6%. Variation in parameters in a one-way sensitivity analysis is shown in . Variations in the results were also assessment based on different parametric functions. Probability of ceritinib to be cost-effective compared to comparator treatment was estimated based on the different willingness-to-pay thresholds through probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) using Monte-Carlo simulation with 1000 iterations conducted.

Results

Base case deterministic results

Results of the base case analysis are presented in . All costs, total life-years, and QALYs are reported per patient on a discounted basis. Over 4 years, ceritinib was associated with 0.86 QALYs and total direct costs of $89,740 in patients previously treated with crizotinib. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was $149,117 comparing ceritinib vs BSC, $80,100 vs pemetrexed, and $104,436 vs HC.

Table 3. Base case results.

Alternative scenarios

The following three alternative scenarios were considered:

Analysis comparing ceritinib vs docetaxel resulted in ICER of $149,780/QALY, driven mainly by the relative low cost of docetaxel.

Alternatively, observed KM were considered rather than parametric functions. Results had minimal deviation from the base case results, due to the short survival associated with ALK + NSCLC once patients progressed with ceritinib ().

Based on quality-of-life data reported in ASCEND-2, ceritinib was associated with continued maintenance of quality-of-life once patients discontinued on treatment with crizotinib.

Table 4. Alternative scenarios.

Applying the utility scores reported for crizotinib in the PROFILE 1007 study resulted in ICERs of $119,926/QALY vs BSC, $67,311/QALY vs pemetrexed, and $87,695 vs historical controls (). Utilities associated with crizotinib (0.82 [0.79–0.85]) were significantly higher than pemetrexed (0.77 [0.70–0.79]) or docetaxel (0.66 [0.58–0.74])Citation30.

Sensitivity analyses

All parameters were varied in a one-way sensitivity analysis. depicts the results of the one-way sensitivity analyses in parameters resulting in at least 5% change in the ICER. The results were most sensitive to the following: cost of ceritinib until treatment discontinuation, unit cost of ceritinib and dose intensity, unit cost of pemetrexed, time horizon, and parametric functions (log-normal distribution, log-logistic distribution, Gompertz).

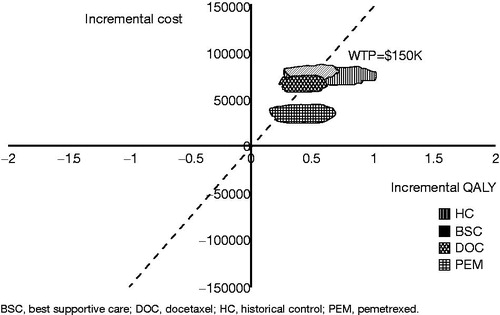

PSA results predicted that the probability of ceritinib to be the most cost-effective treatment compared to other alternatives with willingness-to-pay (WTP) of $150,000 (). For ceritinib vs BSC, average ICER per QALY gained was $152 689, and the probability of ceritinib being cost-effective was 46.3%. For ceritinib vs pemetrexed, average ICER per QALY gained was $77,557, and the probability of ceritinib being cost-effective was 99%. For ceritinib vs historical controls, average ICER per QALY gained was $112,019, and the probability of ceritinib being cost-effective was 94% at a WTP of $150,000.

Discussion

This analysis assessed the cost-effectiveness of ceritinib compared to alternatives in patients with ALK + NSCLC who have had one prior ALK therapy in Canada. The cost-effectiveness of ceritinib vs current alternatives suggests that ceritinib could be cost-effective based on a threshold ranging from $100K to $150K, driven mainly from the survival benefit gained from ceritinib compared to current alternatives. Alternate scenarios, taking into account the utilities from PROFILE 1007, further demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of ceritinib. Docetaxel was considered as an alternate scenario, as no utilization was reported in the retrospective Canadian chart studyCitation19. However, docetaxel was considered a comparator based on a previous pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review (pCODR) assessment in ALK + NSCLC patientsCitation11. Validation of the model was based on the visual fit of reconstructed (pemetrexed and BSC) and/or observed (ceritinib and HC) KM curves and projected estimates derived from parametric functions (). Results from the one-way sensitivity analysis generally supported these results, with most variation observed with assumptions for PFS or OS transitional probabilities and ceritinib drug cost were varied. The PSA results predicted ceritinib to be the most cost-effective treatment compared to other alternatives with a WTP of $150,000.

There are no guidelines in the assessment of cost-effectiveness of technologies based on efficacy results with a single-arm study, other published studies also applied efficacy data from other published sources and assumed a “naïve-indirect” comparisonCitation31,Citation32. pCODR considered the structure and efficacy assumptions in the model as acceptableCitation33. This analysis is subject to limitations, mainly obtaining efficacy data for comparators due to lack of head-to-head data with ceritinib. Efficacy data were not entirely representative of ceritinib population (second-line and third-line), as they were derived from the general NSCLC population or ALK + NSCLC population with different lines of therapy. Costs associated with the BSC arm could be under-estimated, as it has been previously reported that the average cost per patient-month ranged from $1645–$1792 in patients with metastatic NSCLC, after discontinuation of chemotherapyCitation34. This model assumes no further treatment in the progressive disease state for comparators, based on the number of systemic treatments patients received post-discontinuation of crizotinib in the Canadian cohort studyCitation19. In the Canadian cohort study, 10/49 patients received second line treatment post-crizotinib, of which 3/10 were single agent chemotherapy and 2/10 received erlotinib. The remaining received ceritinibCitation19. However, the costs of post-progression in the pemetrexed arm may be under-estimated, as it was reported that nearly 40% of the patients discontinuing treatment on pemetrexed received further anti-neoplastic treatmentCitation25. Assessment of the post-progression costs in the ceritinib arm had limited impact on the ICER (< 5% change in the ICER). Due to the limitation in the sample size for the historical arm, the analysis included patients who received systemic treatment and no further treatment. As such, time to event analysis could be over-estimated, as it was estimated from the time of discontinuation with crizotinib, rather than from the time of treatment initiation. Recommendations for future studies to address the main limitations of this study include re-analysis of the cost-effectiveness of ceritinib in patients who have had prior treatment with crizotinib based on the results of an ongoing randomized phase 3 trial of ceritinib compared to docetaxel or pemetrexed (ASCEND-5, NCT01828112).

In conclusion, results of the base case analysis suggest that ceritinib is cost-effective in ALK + NSCLC patients who have received prior treatment with crizotinib, assuming a threshold for oncology treatments of $150 000 in Canada. As recognized by the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review (pCODR), NSCLC is a disease with the leading cause of death in Canada, with no alternative treatmentCitation35. Ceritinib addresses the significant unmet need for a sub-group of NSCLC patients who harbor ALK gene rearrangements and provides a potential survival benefit, while aligning with patient values. While there are risks associated with recommending interventions with potentially immature data, introduction of new technologies is always possible and should be consideredCitation35 in cases where there are clear unmet needs, coupled with poor survival.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This analysis was sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

ZZ, ZC, FL, and XJ are employees of Analysis Group and received consulting fees from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. MR is a Research Fellow in Health Economics at the University of Toronto. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anuradha Bandaru of Novartis Healthcare Private Limited for providing medical editorial assistance with this manuscript.

References

- Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Toronto: OCCS, 2014

- Canadian Cancer Society. Lung Cancer Statistics, 2014. http://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/CW/cancer%20information/cancer%20101/Canadian%20cancer%20statistics/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2014-EN.pdf, accessed May 2015

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Version 6. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2015

- Vijayvergia N, Mehra R. Clinical challenges in targeting anaplastic lymphoma kinase in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2014;74:437-46

- National Cancer Institute, US. SEER Program. Non-small cell cancer of the lung and bronchus (invasive). Table 15.58.

- Yang P, Kulig K, Boland J, et al. Worse disease free survival in never smokers with ALK + lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:90-7

- Rodig S, Mino-Kenudson M, Dacic S, et al. Unique clinicopathologic features characterize ALK-rearranged lung adenocarcinoma in the western population. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:5216-23

- Shaw A, Yeap B, Mino-Kenudson M, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who harbour EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4247-53

- Pfizer Canada Inc. Xalkori (crizotinib) Product Monograph. Date of Revision: January 27, 2015

- Pan-Canadian Funding Summary: Crizotinib (Xalkori) for advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Canadian agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). https://www.cadth.ca/xalkori-advanced-nsclc-resubmission-details. Accessed February 2016

- Pan-Canadian Oncology Drug review for crizotinib. https://www.cadth.ca/xalkori-resubmission-first-line-advanced-nsclc-details. Accessed February 2016

- Forde PM, Rudin CM. Crizotinib in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2012;13:1195-201

- Marsilje TH, Pei W, Chen B, et al. Synthesis, structure-activity relationships, and in vivo efficacy of the novel potent and selective anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor 5-chloro-N2-(2-isopropoxy-5-methyl-4-(piperidin-4-yl)phenyl)-N4-(2-(isopropylsulf onyl)phenyl)pyrimidine-2,4-diamine (LDK378) currently in phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials. J Med Chem 2013;56:5675-90

- Ceritinib product monograph, July 2015

- Felip EKD, Kim DW, Mehra R, et al. Efficacy and safety of certinib in patients with advanced anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-rearranged (ALK+) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): an update of ASCEND-1. Poster presented at ESMO. 2014;Abstr # 1295P

- Ceritinib, European Public Assessment Report. 2015 http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/003819/WC500187506.pdf. Accessed October 2015

- Mok T, Spigel D, Felip E, et al. ASCEND-2: a single-arm, open-label, multicenter phase 2 study of ceritinib in adult patients (pts) with ALK-Rearranged (ALK+) Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) previously treated with chemotherapy and Crizotinib (CRZ). 2015, Abs # 8059

- Sacco JJ, Botten J, Macbeth F, et al. The average body surface area of adult cancer patients in the UK: a multicentre retrospective study. PLoS One 2010;5:e8933

- Kayaniyil S, Wilson J, Hurry M et al. Economic burden of patients with ALK + mutation non-small cell lung cancer after treatment with crizotinib: a Canadian retrospective observational study. Poster presented at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. November 2015

- Djalalov S, Beca J, Hoch JS, et al. Cost effectiveness of EML4-ALK fusion testing and first-line crizotinib treatment for patients with advanced ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1012-19

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. HTA guidelines for economic evaluation of health technologies: Canada. 3rd edn. 2006

- http://digitizer.sourceforge.net.

- Guyot P, Ades AE, Ouwens MJ, et al. Enhanced secondary analysis of survival data: reconstructing the data from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:9

- Hollander MJ. Costs of end-of life care: findings from the province of Saskatchewan. Healthc Q 2009;12:50-8

- Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1589-97

- Smit EF, Burgers SA, Biesma B, et al. Randomized phase II and pharmacogenetic study of pemetrexed compared with pemetrexed plus carboplatin in pretreated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2038-45

- Canadian CPI. http://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/indicators/capacity-and-inflation-pressures/inflation/historical-data/. Accessed March 2015

- Chouaid C, Mitchell PLR, Agulnik J,et al. Health-related quality of life in advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Patients. Value Health 2012:A1-A256

- Nafees B, Stafford M, Gavriel S, et al. Health state utilities for non small cell lung cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:84

- Blackhall F, Kim DW, Besse B, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and quality of life in PROFILE 1007: a randomized trial of crizotinib compared with chemotherapy in previously treated patients with ALK-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:1625-33

- Pan-Canadian Oncology Drug review for adcetris. 2013. https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pcodr/pcodr-adcetrishl-fn-egr.pdf Accessed November 2015

- Pan-Canadian Oncology Drug review for bosulif. 2015. https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pcodr/pcodr_bosutinib_bosulif_cml_fn_egr.pdf. Accessed November 2015

- Pan-Canadian Oncology Drug review for ceritinib. https://www.cadth.ca/zykadia-metastatic-non-small-cell-lung-cancer-details. Accessed November 2015

- Navaratnam S, Kliewer EV, Butler J, et al. Population-based patterns and cost of management of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer after completion of chemotherapy until death. Lung Cancer 2010;70:110-5

- Dillon A. Responsiveness, language, and alignment: reflections on some challenges for health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2015;31:223-225

- Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2005;353:123-32

- Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2385-94

- Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2095-103

- Mean dose intensity. Novartis Clinical Study Report for ASCEND-1. East Hanover, New Jersey. 2014

- Cancer Care Ontario, drug formulary. https://www.cancercare.on.ca/toolbox/drugformulary/. Accessed May 2015.

- DeltaPA®, IMSB databases. Accessed May 2015

- Ontario Schedule of Benefits for Physician services. 2014 http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/ohip/sob/sob_mn.html. Accessed May, 2015

- http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/ohip/sob/sob_mn.html. Accessed May 2015

- Ontario Case Costing Initiative, 2010/2011 costs. https://hsimi.on.ca/hdbportal/. Accessed May 2015