Abstract

Objectives: Published reports have shown the prevalence and incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is increasing in Japan. The objective of this study is to examine change in GERD incidence, and to understand current patient demographics, medical costs, treatment status, and the suitability of current treatment based on analysis of an insurance claims database.

Methods: An insurance claims database with data on ∼1.9 million company employees from January 2005 to May 2015 was used. Prevalence, demographics, and medical costs were analyzed by cross-sectional analysis, and incidence and treatment status were analyzed by longitudinal analysis among newly-diagnosed GERD patients.

Results: GERD prevalence in 2014 was 3.3% among 20–59 year-olds, accounting for 40,134 people in the database, and GERD incidence increased from 0.63% in 2009 to 0.98% in 2014. In 2014, mean medical cost per patient per month for GERD patients aged 20–59 was JPY 31,900 (USD 266 as of January 2016), which was ∼2.4-times the mean national healthcare cost. The most frequently prescribed drugs for newly-diagnosed GERD patients were proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Although PPIs were prescribed more often in patients with more doctor visit months, over 20% of patients that made frequent doctor visits (19 or more visits during a 24 calendar months period) were prescribed PPIs during only 1 calendar month or not at all.

Limitations: The database included only reimbursable claims data and, therefore, did not cover over-the-counter drugs. The database also consisted of employee-based claims data, so included little data on people aged 60 years and older.

Conclusions: Given the increasing incidence of GERD in Japan there is a need for up-to-date information on GERD incidence. This study suggests that some GERD patients may not be receiving appropriate treatment according to Japanese guidelines, which is needed to improve symptom control.

Introduction

According to the Montreal definition, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus causing troublesome symptoms and/or complicationsCitation1. GERD symptoms impair health-related quality-of-life (HR-QoL)Citation2,Citation3. When considering the economic impact of GERD, it is important to take into account indirect costs that include loss of work productivity, along with the direct costs of medical careCitation4. In addition, GERD is a major risk factor for Barrett’s esophagusCitation5,Citation6 and esophageal adenocarcinomaCitation7, and the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is increasing in the Western worldCitation8.

A review paper has shown the reported prevalence of GERD with esophageal syndrome in Japan to be 6.6–24.3%Citation9. This is a range of results obtained from six studies performed between 2001–2006 that shared the same diagnostic criteria for GERD of heartburn at least 2 times/week. Reports have also shown that the prevalence and incidence of GERD is increasing in JapanCitation9–11. Worldwide, GERD prevalence is highest in the US and Europe (28.8% and 23.7%, respectively), followed by Western Asia (12.5–27.6%), Central Asia (7.6–19.4%), and East Asia (2.5–9.4%)Citation12. Various reasons have been suggested for these regional differences, and a number of lifestyle factors, dietary habits, and BMI in particular have been reported to affect GERD prevalenceCitation13–16. The prevalence and incidence of GERD are expected to continue increasing in Japan given the increasing westernization of dietary habits.

After changes have been made to lifestyle, the main method of treating GERD is with medications such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), potassium-competitive acid blockers (PCABs), histamine H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), and antacids. Clinical practice guidelines for GERD published by the Japanese Society of Gastroenterology recommend PPIs as the first-line class of drugs for initial treatment of GERD based on their therapeutic effect and cost-efficiencyCitation17. When symptoms persist, maintenance PPI therapy becomes necessary and surgery may be performedCitation17. Similar to Japanese guidelines, US guidelines recommend maintenance therapy with PPIs for alleviation of GERD symptoms and treatment of erosive esophagitisCitation18.

At present, there is insufficient knowledge of the current status of GERD treatment in Japan and little research has been conducted into the medical costs of GERD. Some reports have examined the cost-effectiveness of different treatment methodsCitation19 and indirect economic losses from GERDCitation20, but no study has yet compared GERD with other diseases in terms of their medical costs. As the prevalence and incidence of GERD increases in Japan, an up-to-date analysis of treatment status and medical cost based on a large-scale database will help quantify the impact.

This study analyzed a health insurance claims database to obtain current information on Japanese patients with GERD. Change of incidence with time was examined, prevalence, demographics, medical costs, and treatment status were analyzed, and the suitability of treatment currently provided to Japanese patients with GERD was evaluated.

Methods

Data source

A health insurance claims database provided by Japan Medical Data Center was used. The database contains standardized health insurance eligibility and claims data provided by employee-based health insurance societies and contains data on ∼1.9 million people. The database is comprised of company employees and their families, and, therefore, contains little data (only ∼7% of all database subjects) on persons aged 60 years or older. Diagnostic names used in the database follow the International Classification of Diseases tenth revision (ICD-10) coding scheme published by the World Health Organization (WHO), and drug names follow the ATC classification system published by WHO. The PCAB, vonoprazan is not yet mentioned in Japanese guidelines and is not often identified as being in a drug class separate from PPIs, as it was only launched in Japan in February 2015. Due to the small amount of prescribing data on vonoprazan present in the database, for our analysis these data were merged with the PPI prescribing data.

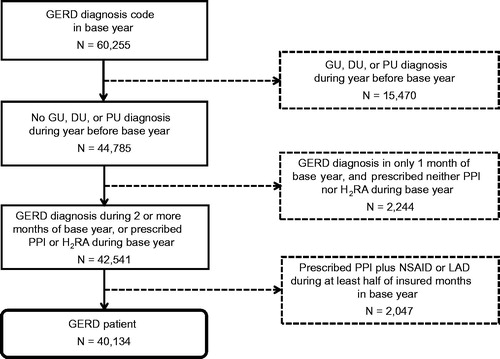

Data from between January 2005 and May 2015 were analyzed and patients with GERD were extracted using the following algorithm ();

Figure 1. Algorithm for identification of gastroesophageal reflux disease patients. The population, 1,396,262 people insured during all calendar months of 2013 and at least 1 calendar month of 2014, was analyzed. N = number of patients taking 2014 as the base year. GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; GU, gastric ulcer; DU, duodenal ulcer; PU, peptic ulcer (site unspecified); PPI, proton pump inhibitor; H2RA, histamine H2 receptor antagonist; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; LDA, low-dose aspirin.

Identify people covered by insurance during all calendar months of the year prior to the analyzed year (defined as the base year) and with at least one claim during the base year with a definitive GERD diagnosis coded as K21.0 or K21.9 according to ICD-10Citation21.

Exclude people with at least one claim during the year prior to the base year with a definitive diagnosis of gastric ulcer (coded as K25), duodenal ulcer (coded as K26), or peptic ulcer, site unspecified (coded as K27) according to ICD-10Citation21.

Exclude people with claims with a definitive GERD diagnosis in only 1 calendar month during the base year who were not prescribed a PPI or H2RA.

Exclude people prescribed both a PPI and either a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or low-dose aspirin (LDA: 100–300 mg/day of aspirin, or 81–324 mg/day of aspirin dialuminate) in more than half the insured calendar months of the base year.

People prescribed an NSAID or LDA in more than half of the insured calendar months of the base year were excluded on the assumption that they were given an inaccurate diagnosis of GERD.

Newly-diagnosed GERD patients were defined as people with no definitive GERD diagnosis during the year prior to the base year.

The authors declare that this study was performed using anonymized and personally unidentifiable data, and, therefore, the Declaration of Helsinki and Japan’s Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects do not apply.

Analysis

A cross-sectional analysis was conducted to analyze GERD prevalence, GERD patient demographics, use of prescribed drugs, and medical costs split into inpatient, outpatient, and prescribed drug costs for patients with GERD. To compare the medical costs of GERD with other common diseases, we analyzed medical costs for type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. The data during 2014 as base year were employed to calculate the most recent prevalence rate. The prevalence rate was calculated in people insured during all calendar months of 2013 and at least 1 calendar month of 2014, and was determined by dividing the number of patients with GERD by the number of people in the database. Longitudinal analysis was also conducted to analyze incidence, treatment costs, and treatment status in newly-diagnosed GERD patients observed for a period of at least 2 years following initial diagnosis. The incidence rate was calculated among people insured during all calendar months of the year prior to the base year and at least 1 calendar month of the base year, and was determined by dividing the number of newly-diagnosed GERD patients by the number of people excluding patients (defined as population at risk) that had already developed GERD by the previous year in the database. Although we analyzed data from 2005–2015, the sample volume was insufficient in 2005–2008, and data were available for only part of the year in 2015. Consequently, we based our study on data from 2009–2014, because we could obtain an adequate sample volume in this period. Treatment status was examined by frequency of doctor visits, shown as number of visit months, which means the number of calendar months during the 24 calendar months after index month when a doctor visit occurred. For example, patients with 7 visit months made a doctor visit during any 7 of the 24 calendar months that followed the month of diagnosis, and patients with 0 visit months made no doctor visits during the 24 calendar months that followed the month of diagnosis. Also, we estimated severity of GERD symptoms based on the frequency of doctor visits; so we considered the patients with 19 or more visit months during 24 calendar months to be severe GERD patients, then analyzed their treatment status with PPI.

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

GERD patient demographics, prevalence, and incidence

The database included 1,396,262 people insured during all calendar months of 2013 and at least 1 calendar month of 2014. Among them, 60,255 received a definitive GERD diagnosis in 2014, of whom 40,134 were defined as GERD patients according to the algorithm ().

The number of days’ supply per patient of each drug were 68.5 days for PPI, 26.3 days for H2RA, 30.8 days for antacid, and 85.0 days for other drugs in 2014. Among the PPIs, the most frequently prescribed drugs were lansoprazole, rabeprazole, esomeprazole, and omeprazole, in descending order of days’ supply.

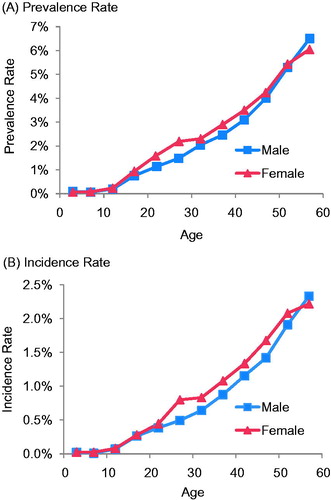

Analysis showed that, in 2014, there was a GERD prevalence rate of 3.3% in people aged 20–59 years. Prevalence rates by age and sex are shown in . Prevalence rates increased notably with age, and the profile of this increase was similar in males and females.

Figure 2. (A) Prevalence rate and (B) Incidence rate of gastroesophageal reflux disease by age and sex.

As shown in , the profiles of GERD incidence rates by age and sex were similar to prevalence rates in the same year. GERD incidence rates between 2009–2014 in the total population are shown in . Incidence rates trended upwards from 0.63% (90% CI =0.61–0.65%) in 2009 to 0.98% (90% CI =0.97–1.00%) in 2014, and this trend remained after adjusting for age and sex.

Table 1. Incidence rates of gastroesophageal reflux disease from 2009–2014.

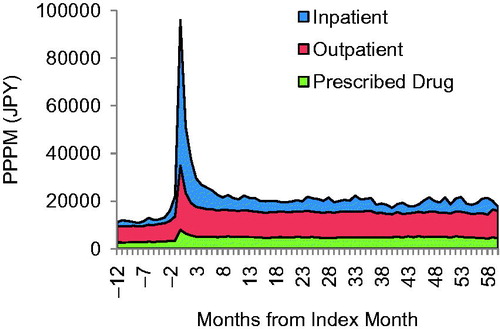

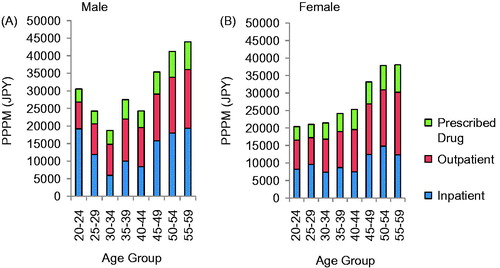

Medical costs of GERD

In 2014, the mean medical cost per patient per month (PPPM) for GERD in patients aged 20–59 years was Japanese Yen (JPY) 31,900 (90% CI = JPY 31,200–32,700) (USD 266 as of January 2016), which is split among inpatient (JPY 12,700), outpatient (JPY 13,200), and prescribed drug costs (JPY 6000). Medical costs PPPM by age group are shown in . Analysis showed medical costs were higher in patients aged 45 years or older than in patients aged 44 years or younger in both males and females, and medical costs increased with age in females. Medical cost PPPM was higher in males than in females at all ages, other than in 30–34 and 40–44 age groups. As a comparison, after adjusting age and sex distribution to those of GERD patients, the mean medical costs of type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension were JPY 48,300 (90% CI = JPY 47,000–49,700), JPY 23,500 (90% CI = JPY 23,300–23,800), and JPY 37,500 (90% CI = JPY 36,900–38,100), respectively.

Figure 3. Medical costs per patient per month for (A) males and (B) females. PPPM, per patient per month; JPY, Japanese yen.

The medical cost of newly-diagnosed GERD patients was highest in the calendar month of diagnosis (designated as the index month) for all cost categories (drug, outpatient, and inpatient), and drug and outpatient costs remained constant from the third month onwards ().

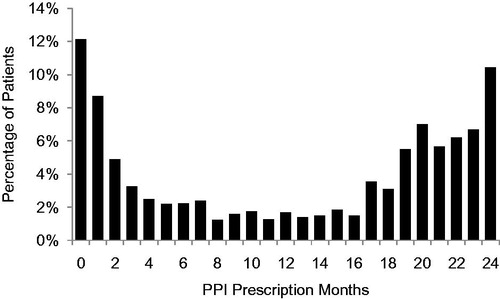

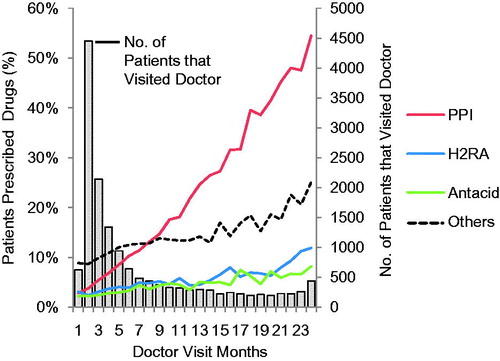

Treatment status of newly diagnosed GERD patients

The most frequently prescribed class of drugs among newly-diagnosed GERD patients was PPIs. shows the percentage of newly-diagnosed GERD patients prescribed drugs by drug class, grouped according to the number of visit months during the 24 calendar months. The most common number of visit months among newly-diagnosed GERD patients was 2, and the number of newly-diagnosed GERD patients decreased with an increasing number of visit months. The percentage of patients prescribed PPIs increased with higher visit months, and PPIs were the most commonly prescribed drug class in newly-diagnosed GERD patients with 7 or more visit months. The percentage of newly-diagnosed GERD patients prescribed other classes of drugs increased only slightly with increasing visit months.

Figure 5. Percentage of patients prescribed each drug class grouped by number of doctor visit months during 24 months after index month. PPI, proton pump inhibitor; H2RA, histamine H2 receptor antagonist; PPPM, per patient per month.

Newly-diagnosed GERD patients with 19 or more visit months were extracted from the database and the number of months during which PPIs were prescribed was analyzed (). Many of these patients were prescribed PPIs in 19 or more calendar months, while over 20% of them were prescribed PPIs during 1 or no calendar months, and 12% were prescribed no PPIs. The mean medical cost of patients prescribed PPIs during 1 or no calendar months was JPY 49,800 (90% CI = JPY 42,200–57,400), and the mean medical cost of patients with the same visit months as PPI prescription months was JPY 71,100 (90% CI = JPY 55,300–86,900). The most frequently prescribed class of drugs in the former group was H2RAs, which were only prescribed to 22% of those patients. No substantial difference in comorbidities was detected between these two patients groups.

Discussion

In 2014, the prevalence of GERD in people aged 20–59 years was 3.3%. This is half or less than half the prevalence observed in previous reports, which ranged from 6.6–24.3%Citation9. This prevalence is also smaller than the 4% prevalence observed in a 2002 study of Japanese workers, of whom only a small percentage were 60 years or older and just 1.1% were 70 years or olderCitation22. It was found that prevalence and incidence rate increased with age in this study (); therefore, the reason for the lower prevalence rate in this study than that in the previous report is probably because of the difference in age structure: having little older age data in this study. The incidence rates obtained in this study increased each year between 2009–2014, which is also the same tendency observed in previous studies. Possible reasons for the increasing prevalence of GERD include a decrease in the Helicobacter pylori infection rateCitation23,Citation24, an increase in gastric acid secretion due to westernization of dietary habitsCitation25, and an increase in obesityCitation26,Citation27.

The mean medical cost PPPM for GERD patients aged 20–59 was JPY 31,900, which was ∼2.4-times the mean national healthcare cost PPPM for Japanese people aged 20–59 in 2013 (JPY 13,500)Citation28. Medical costs for patients with GERD were within the range of those for other common diseases (from JPY 23,500 to JPY 48,300 for type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension).

GERD is reported to lead to impairment of HR-QoLCitation2,Citation3 and reduced work productivityCitation4, and implementing the recommended treatment may lessen this impact. PPIs are currently recommended in clinical practice guidelines as the first-line class of drugs for initial treatment of GERD. This recommendation is based on PPIs being more effective at improving GERD symptoms and resolving damage to the esophageal mucosa compared with H2RAs and digestive tract prokinetic agents, and because PPIs offer excellent cost-effectivenessCitation17. This study showed that, while the number of months during which PPIs were prescribed increased with the number of visit months in newly-diagnosed GERD patients, the percentage of patients prescribed PPIs was similar to that prescribed H2RAs and antacids in patients with 1 or 2 visit months (). Furthermore, among patients with 19 or more visit months out of 24 calendar months, 12% were prescribed no PPI and 8% were prescribed PPIs during just 1 calendar month (). The possibility that patients received fewer PPI prescriptions due to comorbidities was considered, but analysis showed no substantial difference in comorbidities between patients that were prescribed PPIs during few or no months and those prescribed PPIs during most months. Patients treated with PPIs have been reported to have more comorbidities than those without PPIs in previous studiesCitation29,Citation30, which is different from this study, probably due to different attributes of the population, such as age, lifestyle factors, etc. Based on these results, treatment for patients with GERD does not seem to be implemented in accordance with Japanese guidelines on clinical practice. Another potential reason that a patient would receive fewer PPI prescriptions is if they exhibited an inadequate response to PPI therapy, but this would not explain why a substantial percentage of patients were never prescribed a PPI. It may be possible that there were some patients who received a GERD definitive diagnosis and then bought a H2RA or antacid as over-the-counter (OTC) drugs; however, it could not be clear because the database includes only costs covered by insurance and, therefore, does not include OTC drug costs in this study.

This study has several limitations. The health insurance society database used is comprised of data on company employees and their families, and, therefore, contains little data on people aged 60 years or older, and no data on persons aged 75 years or older. Prevalence was, therefore, calculated among people aged 20–59 years. Demographic changes in the population each year may also affect the results. In this study, results related to incidence were confirmed by adjusting for population age and sex. While the database includes people from throughout Japan, the data may be biased in terms of living location and economic status. Furthermore, data is not kept on people if they transfer to a different health insurance provider due to change of employment or for other reasons. The database also includes only costs covered by insurance and, therefore, does not include non-reimbursable costs such as OTC drugs. Consequently, drug costs may be under-estimated. Also, onset of GERD is not available in the database in this study; so that it might be possible that even the patients defined as newly-diagnosed GERD patients had taken OTC drugs for GERD symptom before the first diagnosis. While this study should provide reliable information on the prescription status of PPIs in Japan because there are no OTC PPIs in Japan, care must be taken when making comparisons between PPIs and other drug classes such as H2RAs that are available OTC. Moreover, this study lacks some information, such as BMI and lifestyle factors, which is reported to relate to incidence of GERD.

Conclusions

Analysis of a Japanese health insurance claims database showed that the incidence of GERD tended to increase over time. The medical costs for GERD were ∼2.4-times the mean national healthcare costs and within the range of those for other common diseases. However, our data suggests that GERD patients are not still received PPI treatment appropriately.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

HM has received financial support for research from Astellas Pharma Incorporated, Eisai Company Limited, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Daiichi Sankyo Company Limited, Sumitomo Dainippon Phama Company Limited, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, and Chugai Pharmaceutical Company Limited, and got honorarium as a speaker from AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo Company Limited, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Company Limited, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. KI and TT are employees of Milliman, which has received consultancy fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. SH is an employee of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Acknowledgments

The analysis of the study and draft of the manuscript was prepared by academic and industry authors with professional editorial assistance, funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. The authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and data analyses, and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol.

References

- Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, et al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1900-20

- Velanovich V. Quality of life and severity of symptoms in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a clinical review. Eur J Surg 2000;166:516-25

- Prasad M, Rentz AM, Revicki DA. The impact of treatment for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life: a literature review. Pharmacoeconomics 2003;21:769-90

- Joish VN, Donaldson G, Stockdale W, et al. The economic impact of GERD and PUD: examination of direct and indirect costs using a large integrated employer claims database. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:535-44

- Xiong LS, Cui Y, Wang JP, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Barrett's esophagus in patients undergoing endoscopy for upper gastrointestinal symptoms. J Dig Dis 2010;11:83-7

- Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Storskrubb T, et al. Erosive esophagitis is a risk factor for Barrett's esophagus: a community-based endoscopic follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1946-52

- Lagergren J, Bergström R, Lindgren A, et al. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 1999;340:825-31

- Pera M. Trends in incidence and prevalence of specialized intestinal metaplasia, barrett's esophagus, and adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction. World J Surg 2003;27:999-1008

- Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol 2009;44:518-34

- Miwa H, Oshima T, Tomita T, et al. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease: the recent trend in Japan. Clin J Gastroenterol 2008;1:133-38

- Manabe N, Haruma K, Kamada T, et al. Changes of upper gastrointestinal symptoms and endoscopic findings in Japan over 25 years. Intern Med 2011;50:1357-63

- Ronkainen J, Agréus L. Epidemiology of reflux symptoms and GORD. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2013;27:325-37

- Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, et al. Lifestyle related risk factors in the aetiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Gut 2004;53:1730-35

- Nocon M, Labenz J, Willich SN. Lifestyle factors and symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux - a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23:169-74

- Murphy DW, Castell DO. Chocolate and heartburn: evidence of increased esophageal acid exposure after chocolate ingestion. Am J Gastroenterol 1988;83:633-36

- El-Serag HB, Satia JA, Rabeneck L. Dietary intake and the risk of gastrooesophageal reflux disease: a cross sectional study in volunteers. Gut 2005;54:11-17

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) clinical practice guidelines 2015 Revision 2 [In Japanese]. Tokyo, Japan: The Japanese Society of Gastroenterology, 2015

- Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:308-23

- Habu Y, Maeda K, Kusuda T, et al. “Proton-pump inhibitor-first” strategy versus “step-up” strategy for the acute treatment of reflux esophagitis: a cost-effectiveness analysis in Japan. J Gastroenterol 2005;40:1029-35

- Suzuki H, Matsuzaki J, Masaoka T, et al. Greater loss of productivity among Japanese workers with gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms that persist vs resolve on medical therapy. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:764-71

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [Japan]. Statistical classification of diseases and cause of death [In Japanese]. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2003. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/sippei/. Accessed January 22, 2016

- Moki F, Kusano M, Mizuide M, et al. Association between reflux oesophagitis and features of the metabolic syndrome in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;26:1069-75

- Yagi S, Okada H, Takenaka R, et al. Influence of Helicobacter pylori eradication on reflux esophagitis in Japanese patients. Dis Esophagus 2009;22:361-7

- Nakajima S, Nishiyama Y, Yamaoka M, et al. Changes in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastrointestinal diseases in the past 17 years. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25(1 Suppl):S99-S110

- Kinoshita Y, Kawanami C, Kishi K, et al. Helicobacter pylori independent chronological change in gastric acid secretion in the Japanese. Gut 1997;4:452-8

- Sakaguchi M, Oka H, Hashimoto T, et al. Obesity as a risk factor for GERD in Japan. J Gastroenterol 2008;43:57-62

- Adachi K, Mishiro T, Tanaka S, et al. Gender differences in the time-course changes of reflux esophagitis in Japanese patients. Intern Med 2015;54:869-73

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [Japan]. Medical cost of the general population in Japan in 2013 [In Japanese]. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2015. http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/GL08020103.do?_toGL08020103_&listID =000001138601. Accessed January 25, 2016

- Katz PO, Zavala S. Proton Pump Inhibitors in the Management of GERD. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14 (1 Suppl):S62-S6

- Hvid-Jensen F, Nielsen RB, Pedersen L, et al. Lifestyle factors among proton pump inhibitor users and nonusers: a cross-sectional study in a population-based setting. Clin Epidemiol 2013;5:493-9