Abstract

Background: Overactive bladder (OAB) is a common condition that has a significant impact on patients’ health-related quality-of-life and is associated with a substantial economic burden to healthcare systems. OnabotulinumtoxinA has a well-established efficacy and safety profile as a treatment for OAB; however, the economic impact of using onabotulinumtoxinA has not been well described.

Methods: An economic model was developed to assess the budget impact associated with OAB treatment in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK, using onabotulinumtoxinA alongside best supportive care (BSC)—comprising incontinence pads and/or anticholinergic use and/or clean intermittent catheterisation (CIC)—vs BSC alone. The model time horizon spanned 5 years, and included direct costs associated with treatment, BSC, and adverse events.

Results: Per 100,000 patients in each country, the use of onabotulinumtoxinA resulted in estimated cost savings of €97,200 (Italy), €71,580 (Spain), and €19,710 (UK), and cost increases of €23,840 in France and €284,760 in Germany, largely due to day-case and inpatient administration, respectively. Projecting these results to the population of individuals aged 18 years and above gave national budget saving estimates of €9,924,790, €27,458,290, and €48,270,760, for the UK, Spain, and Italy, respectively, compared to cost increases of €12,160,020 and €196,086,530 for France and Germany, respectively. Anticholinergic treatment and incontinence pads were the largest contributors to overall spending on OAB management when onabotulinumtoxinA use was not increased, and remained so in four of five scenarios where onabotulinumtoxinA use was increased. This decreased resource use was equivalent to cost offsets ranging from €106,110 to €176,600 per 100,000 population.

Conclusions: In three of five countries investigated, the use of onabotulinumtoxinA, in addition to BSC, was shown to result in healthcare budget cost savings over 5 years. Scenario analyses showed increased costs in Germany and France were largely attributable to the treatment setting rather than onabotulinumtoxinA acquisition costs.

Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a sub-set of lower urinary tract storage symptoms. It is characterized by urgency with or without incontinence, generally in the presence of frequency and nocturia, with the most severe cases presenting as urinary urge incontinence (UI)Citation1.

In addition to presenting a considerable burden to patients and healthcare systems, the economic burden of OAB, both in terms of direct costs—associated with management of the condition, surgical interventions, treatment of adverse effects and depression, and fractures arising from falls—and indirect costs—arising from reduced productivity and absence from work—are substantialCitation2. The direct cost of management of OAB with UI is estimated to range from €269–€702 per patient per year across five EU countries (Spain, Sweden, Germany, Italy, and the UK)Citation2.

A stepped care approach to the treatment of OAB is widely recommended within treatment guidelines, with conservative interventions at the first stage, including promotion of behavioural modifications, such as changes to fluid intake pattern, pelvic floor exercises, and bladder retraining, alongside the use of incontinence padsCitation1. However, this approach has shown limited efficacy in most patients, and many progress to pharmacological measures to manage their conditionCitation3,Citation4. Furthermore, long-term usage of incontinence pads is associated with potential complications such as urinary tract infections (UTI) and skin breakdownCitation5,Citation6.

Anticholinergic therapy is a first-line intervention in patients progressing to pharmacological management of OABCitation7, but is not always effective and is often poorly toleratedCitation3,Citation8. This leads to poor adherence in treated patients with as high as 70–90% of patients discontinuing their medication within the first year of treatmentCitation9–13.

BOTOX1 (onabotulinumtoxinA), a purified neurotoxin complex, is indicated for the management of overactive bladder with symptoms of urinary incontinence, urgency, and frequency, in adult patients who are not adequately managed with anticholinergicsCitation14,Citation15. Upon failure of anticholinergic therapy, many guidelines recommend the use of onabotulinumtoxinACitation7,Citation16,Citation17. Individuals in phase III trialsCitation18,Citation19 requested re-treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA from 12 weeks after initial administration onwards (median interval between re-treatment was ∼24 weeks); however, due to delay in receiving care the interval between re-treatment request and actually receiving onabotulinumtoxinA treatment may be longer in clinical practice, based on expert clinical opinion.

In the absence of onabotulinumtoxinA, patients may use best supportive care (BSC), including incontinence pads and, for some individuals, continuation of pharmacological therapies. They may also be candidates for invasive therapies to manage OAB, including sacral nerve stimulation (SNS)—a reversible treatment involving an implant to stimulate the sacral nerves which control the bladder and the muscles related to urinary function. Patients who fail SNS may progress to bladder augmentation surgery, which may be performed to decrease pressure within the bladder, increase the size of the bladder, or improve its ability to expand.

We developed an economic model to assess the budget impact associated with treatment of idiopathic OAB within the EU5 countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK), using onabotulinumtoxinA alongside BSC—comprising the use of incontinence pads and/or anticholinergic use and/or CIC—vs BSC alone, based on clinical benefits reported in phase III studiesCitation18,Citation19.

Methods

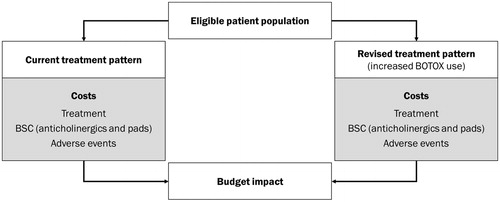

A deterministic model with a 5-year time horizon was developed from the perspective of third party healthcare budget holders and providers. This model estimated the budget impact associated with managing OAB patients with onabotulinumtoxinA + BSC, compared to BSC alone.

Structure and costs

The model included direct costs associated with treatment, BSC and adverse events (). Adverse event costs included those required for patients or a third party performing CIC to empty the bladder, management of UTI, and haematuria. We assumed that resource use (and associated costs) incurred through events occurring in 1 year of the model did not overlap with subsequent years (i.e. they were wholly contained within the model year that they were incurred).

All costs are shown in 2014 Euros. UK costs were converted to Euros at a rate of 1:1.25719 based on mid-market rates from July 2014Citation20.

Patient mortality was not modelled and, therefore, did not have an impact on the size of the patient population or the costs incurred through managing this population.

Model parameters

Eligible patient population

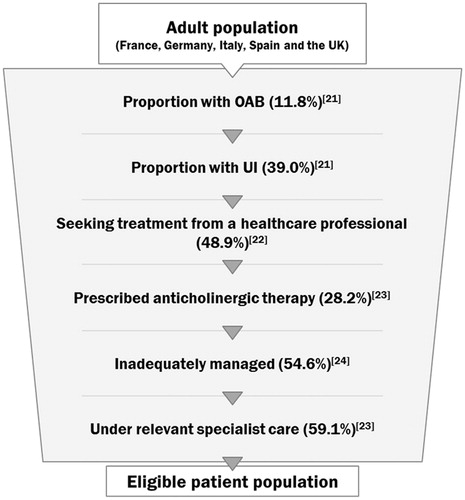

Our analysis considered a population of 100,000 patients in each country. The number of patients deemed eligible for treatment and, therefore, included in the model was the number of adult patients (aged 18 years and over) with OAB and UI under specialist care and inadequately managed with anticholinergic treatmentCitation21–24; it was assumed the eligible patient population consisted of those who have already failed anticholinergic therapy (). Across the five countries included, the same population algorithm was applied, yielding an eligible population of 205 patients per 100,000 individuals in each country—this population was assumed to remain constant over the model time horizon. In the base year, the number of these patients managed with onabotulinumtoxinA was 10 per country, rising to peak numbers of 61 per country in the fifth year of the model time horizon. Incontinence pad usage was based on the proportion of patients that may require pads in addition to their primary treatment and the number of pads they may need per day were based on clinician-verified assumptions and national clinical guidelinesCitation25. Anticholinergic therapy use was based on the proportion of patients who are assumed to be on anticholinergic therapy in addition to their primary treatment based on clinician-verified assumptions, and the proportion of time these patients may stay on these medications annually based on data from the phase III trials for onabotulinumtoxinACitation18,Citation19.

The model estimated the incidence of UTI, CIC, and haematuria, per patient receiving each treatment option, based on data from the phase III trials for onabotulinumtoxinACitation18,Citation19, other published studiesCitation26,Citation27, clinician-verified assumptions and NICE clinical guidelinesCitation25. Per-episode costs were estimated based on published costsCitation28 and assumed usage of medication/procedures to manage UTI and other adverse events, and the number of catheters required to carry out CIC.

The total management costs associated with patients managed using BSC alone and onabotulinumtoxinA + BSC are shown in .

Table 1. OnabotulinumtoxinA uptake over model time horizon.

Table 2. Model parameters.

Table 3. Total annual management cost per patient.

Sensitivity analyses

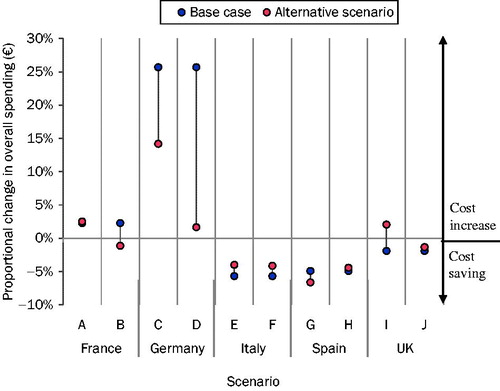

Scenario analyses (described in ) were run to test the model under hypothetical clinically-relevant situations, designed to investigate parameters or assumptions with the most uncertainty. Germany is the only country in which procedures are predominantly carried out in the inpatient setting; therefore, scenarios surrounded increasing the proportion of procedures carried out in the outpatient setting. Similarly, in France, a large proportion of onabotulinumtoxinA patients are managed in the day-case setting, associated with a 3-fold higher tariff, thus a similar sensitivity analysis was conducted for France as well. These scenarios were designed to investigate the impact of aligning practice in Germany and France with other European countries. In France, we also tested augmenting the average cost of anticholinergic therapy to increase usage of a commonly-prescribed option—Vesicare2 (solifenacin succinate). In Italy, clinical opinion identified procedural and incontinence pad costs as likely to vary across different regions and institutions. Thus, sensitivity analyses on these costs were conducted. In Spain, the usage of incontinence pads was identified as a potential area in which cost may increase, and similar to France a scenario in which the two most commonly-used anticholinergic therapy options made up all anticholinergic therapy usage. In the UK, a scenario was tested in which only four rather than six incontinence pads were used per day by patients managed with BSC alone, reflecting a situation in which reimbursement of pads by UK National Health Service (NHS) is capped at four units per day. Along with Spain, the UK is the only other country to reimburse mirabegron at the time of publication, thus we also modelled a scenario in which Betmiga3 (mirabegron) was used in the UK. Lastly, threshold analyses were run to identify the degree to which shifting procedures into the outpatient setting was required to yield cost savings.

Table 4. Scenario analyses.

Results

Base case analysis

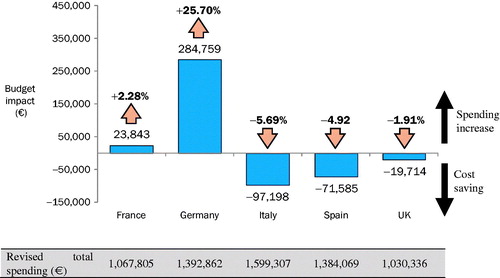

In the base case, increasing the proportion of patients managed with onabotulinumtoxinA (instead of those managed with BSC alone) gradually over the first 5 years resulted in cost savings in three of the five countries, ranging from €19,714 in the UK to €97,198 in Italy (; ); these represented decreases in overall spending, ranging from 1.9–5.7%. In France and Germany, overall spending grew by €23,843 and €284,759, respectively, representing increases of 2.3% and 25.7%.

Table 5. Overall spending and budget impact by country over 5 years per 100,000 individuals.

In all five countries analyzed, incontinence pads and anticholinergic treatment usage represented the largest contributors to overall spending in the current treatment pattern (). OnabotulinumtoxinA acquisition costs represented a considerably smaller proportion of the overall costs (between 0.8–1.7% of overall spending). In the revised treatment pattern, the proportion of spending attributable to onabotulinumtoxinA acquisition remained a minor contributor across all five countries (ranging from 3.4% in Italy to 7.3% in in Germany). Procedure costs, however, while remaining a minor contributor in most of the countries, became the second largest contributor under the revised treatment pattern in Germany, at 29.5%, due to costs of administering onabotulinumtoxinA in the inpatient setting. In fact, procedure costs outweighed acquisition costs by a ratio of 4:1 in Germany, far higher than any other country (the next highest ratio was 1.9:1 in France, the only other country associated with cost increases over 5 years). Savings associated with resource use decreases ranged from €106,110 to €176,600 in Germany and Italy, respectively (). Results per 100,000 patients were extrapolated to give national level estimates within the population aged 18 years and above in each country, based on European demographic dataCitation54. These estimates are shown in .

Table 6. 5-year change in spending per 100,000 patients by cost category.

Table 7. Resource use avoided with increasing use of onabotulinumtoxinA per 100,000 patients over 5 years.

Table 8. Extrapolated country-level 5-year budget impact and resource use estimates for total populations in each country.

Sensitivity analyses

Scenario analyses are shown in ; all scenarios analysed in countries showing cost savings in the base case continued to yield cost savings except one—reducing the number of pads per patient to four in patients managed with BSC in the UK setting, to reflect a hypothetical reimbursement shortfall (scenario I). Testing upper and lower bounds of the day-case tariff in Italy (scenarios D and E), to investigate uncertainty surrounding clinical opinion, had a minimal impact on the model results, with cost savings reported in both scenarios.

In France and Germany, altering assumptions surrounding the treatment setting in which onabotulinumtoxinA is administered had a profound effect on the results of the model. In France, moving all patients managed in the day case setting to the outpatient setting (scenario B) altered the direction of results to yield a cost saving. In Germany, switching 50% of all patients for whom onabotulinumtoxinA is administered in the inpatient setting to the outpatient setting (Scenario C) had a profound effect on cost, by halving the size of proportional cost increases. When all patients managed with onabotulinumtoxinA received their treatment in the outpatient rather than the inpatient setting (scenario D), the overall budget impact was nearly cost neutral. Similar analyses showed that, in France, a threshold of 68% of procedures managed in the outpatient setting yields cost savings.

Discussion

The model estimates that the use of onabotulinumtoxinA in addition to BSC to manage OAB, compared to BSC alone, may result in healthcare budget cost savings over the course of 5 years. These cost savings were replicated to varying degrees across three of the five countries covered by our analysis; the majority of scenarios investigated within sensitivity analyses remained cost saving. These costs savings were achieved despite increases in acquisition costs and the occurrence of certain adverse events, namely UTI and CIC. The largest driver of cost reduction was attributed to significant reductions in resource use—in the form of incontinence pad usage and anticholinergic treatment—associated with the management of OAB with UI over the model’s 5-year time horizon. These resources make up a significant proportion of overall spending on OAB management. Reductions in their usage have a profound impact on the management costs of OAB patients, to the extent that the acquisition costs of onabotulinumtoxinA are uniformly offset across all five countries. The avoided cost of these resources ranged from €106,110–€176,600 per 100,000 individuals in the general population.

France and Germany yielded results that differed significantly from the other countries—namely, cost increases resulting from the increased use of onabotulinumtoxinA. While costs related to onabotulinumtoxinA treatment were the largest contributor to spending in the revised treatment pattern, the vast majority of these costs were attributable to the treatment setting. Scenario analyses confirmed that setting costs were a key driver of overall costs in the model—amending these assumptions alone turned a significant cost increase into a neutral budget impact in Germany, and cost savings in France. These analyses confirm that the budget impact is largely due to the fact that current policies in France and Germany require administration of onabotulinumtoxinA in the day-case and inpatient settings, respectively. Since the well characterized local safety profile of onabotulinumtoxinA—confirmed in phase III trialsCitation18,Citation19—has shown that patients can be safely managed in the outpatient setting, such policies may not be necessary.

Our results align with those of other economic- and resource-use focussed studies within this therapy area. A burden-of-illness analysis across five European countries conducted by Reeves et al.Citation2 noted that the largest contributor to management costs of patients with OAB was incontinence pads, constituting 63% of the annual cost per patient on average. Similarly, Papanicolaou et al.Citation55 conducted a retrospective observational study of medical resource use in patients treated for UI across three EU countries, and noted that the highest contributor to overall management costs was incontinence pad usage and, in addition to the public healthcare sector cost of these items, patients were found to make considerable out-of-pocket contributions for their care. Clearly, incontinence pads (and wider resource use to manage breakthrough symptoms) represent a large cost burden, not only to the healthcare system, but also to patients themselves. Our model reiterates the burden of these direct costs; however, patient-incurred costs, along with other indirect costs, fall outside the scope of this analysis, and warrant further investigation.

Our model does not compare directly to surgical approaches—such as SNS or percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS). While there is the potential for patients to receive these, a number of factors made indirect comparison and, thus, inclusion in the current analysis inappropriate or unfeasible within the scope of this analysis. Of primary concern is that the treatment pathway and the methods by which they are reimbursed are complex and not comparable to that of patients managed with onabotulinumtoxinA.

This analysis takes a more focussed, and ultimately conservative, approach by only estimating the costs associated with onabotulinumtoxinA in addition to BSC, compared to BSC alone—whereas in reality some patients would likely be managed with onabotulinumtoxinA as an alternative to cycling through oral anticholinergics or receiving invasive therapies such as implantable SNS devices or even surgery. While outside the scope of our model, the use of onabotulinumtoxinA and its potential to alleviate some of the patient burden of OAB could also reduce the number of patients requiring more invasive treatment options, such as bladder augmentation surgery or SNS, and the spending associated with these interventions. Thus, with a longer time horizon, further cost-offsetting and further reduction in patient burden associated with resorting to these treatment options is likely; indeed, onabotulinumtoxinA has been shown in clinical trials to reduce the burden of refractory OAB and increase the health-related quality-of-life for these patientsCitation56. Including these treatments downstream may lead to further cost savings, as suggested by a separate UK-focussed cost comparison study conducted within our groupCitation57, which estimated that using onabotulinumtoxinA rather than SNS to manage patients with OAB would lead to cost savings of £234,500 over the reported 7-year battery life of the SNS device—or £11,740 per patient. Given these potential savings, further investigation into these treatment options may be warranted.

Scenario analyses largely remained cost saving, although one notable exception arose from the use of exceptionally high costs of anticholinergic therapy. It should be noted that these scenarios are not based on current care pathways across Europe, but rather investigate hypothetical changes to these pathways which could offer cost and clinical benefit to hospitals and patients, and serve to highlight the need for appropriate reimbursement tariffs to cover onabotulinumtoxinA administration procedures—increased management costs were entirely due to the higher procedure tariffs rather than the cost of onabotulinumtoxinA itself.

Our analysis is not without inherent limitations. We have included the cost of several key adverse events in the model (UTI, CIC and haematuria), based on published phase III trial dataCitation18,Citation19. The cost and resources required to manage these events is also modelled. However, it is possible that additional follow-up healthcare professional visits may occur outside of those required to administer treatment and those required to manage adverse events. We could find no robust data with which to model additional follow-up visits for either BSC or onabotulinumtoxinA, and, thus, the cost of these is not captured within our analysis for either BSC or onabotulinumtoxinA.

Our model focuses on budget impact to healthcare payers and, as such, does not consider factors such as patient treatment satisfaction, patients’ quality-of-life (QoL), or indirect costs. In the wider setting, further cost offsets may be achieved through improved patient outcomes, which could result in indirect and direct cost benefits—for example, increased patient working capability and a reduced risk of depression (and subsequent anti-depressive treatment costs)Citation58. Through these benefits, onabotulinumtoxinA may offer a solution to the problem of inadequate management of OAB with anticholinergic treatment from a patient perspective, increasing patients’ QoL and improving their daily functioning.

Conclusion

Pharmacotherapy treatments for OAB with UI are often ineffective, poorly tolerated, and/or associated with adverse effects or surgical risks. There is an unmet need in patients failing anticholinergic therapy, and onabotulinumtoxinA is a safe and efficacious treatment licensed for the treatment of OAB with UI in patients who are inadequately managed by ≥1 anticholinergic. The introduction of onabotulinumtoxinA to manage OAB with UI is associated with cost savings within three of the five countries analysed. Resource use reductions, which are a significant financial burden to healthcare payers, were demonstrated in all five models. Potential cost savings are substantial, and should be considered alongside the additional clinical and patient benefits associated with onabotulinumtoxinA management that are not captured in the results of this model. In France and Germany, where cost savings were not observed by the model, scenario analyses revealed that changes to local policies regarding the setting in which onabotulinumtoxinA is administered can easily offset most or all of the budget impact of this novel treatment.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The study was sponsored by Allergan Holdings Limited, Marlow, UK. Writing and editorial assistance was provided to the authors by Dr Ruth Zeidman of Covance Inc., London, and funded by Allergan Holdings Limited, Marlow, UK.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

LR and EB are employed by Covance Inc., London. JA, MEV, GP, and ZH are employed by Allergan Holdings Limited, Marlow, UK. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Holger Weidenauer and Clara Loveman for contribution to and support on the project, during which they were employees of Allergan Holdings Limited, Marlow, UK.

Notes

Notes

1 BOTOX is a registered trade name of Allergan Incorporated (Irvine, CA).

2 Vesicare is a registered name of Astellas Pharma Limited (Japan).

3 Betmiga is a registered name of Astellas Pharma Europe BV (The Netherlands).

References

- Abrams P, Andersson KE, Birder L, et al. Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse and faecal incontinence. In: Abrams PCL, Khoury S, Wein A, et al., eds. Incontinence. Plymouth: Health publication, 2009. pp. 1767-820

- Reeves P, Irwin D, Kelleher C, et al. The current and future burden and cost of overactive bladder in five European countries. Eur Urol 2006;50:1050-7

- Thuroff JW, Abrams P, Andersson KE, et al. EU guidelines on urinary incontinence. EAU 2010;59:387-400

- Chapple CR, Khullar B, Gabriel Z, et al. The effects of antimuscarinic treatments in overactive bladder: an update of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2008;54:543-62

- Stohrer M, Castro-Diaz D, Chartier-Kastler E, et al. Guidelines on neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. The Netherlands: EAU, 2008

- Gill BC, Rackley RR, Vasavada SP, et al. Neurogenic bladder. New York, NY: Medscape, 2009. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/453539-overview. Accessed January 25, 2016

- Lucas MG, Bosch RJL, Burkhard FC, et al. EAU guidelines on surgical treatment of urinary incontinence. Eur Urol 2012;62:1118-29

- Oefelein MG. Safety and tolerability profiles of anticholinergic agents used for the treatment of overactive bladder. Drug Saf 2011;34:733-54

- D’Souza AO, Smith MJ, Miller L, et al. Persistence, adherence, and switch rates among extended-release and immediate-release overactive bladder medications in a regional managed care plan. J Manag Care Pharm 2008;14:291-301

- Juzba M, White TJ, Chang EY, et al. Prevalence and cost analysis of overactive bladder in a managed care organization. J Manag Care Pharm 2001;7:365

- Desgagné A, LeLorier J. Incontinence drug utilization patterns in Quebec, Canada. Value Health 1999;2:452-8

- Yu YF, Nichol MB, Yu AP, et al. Persistence and adherence of medications for chronic overactive bladder/urinary incontinence in the California Medicaid program. Value Health 2005;8:495-505

- Shaya FT, Blume S, Gu A, et al. Persistence with overactive bladder pharmacotherapy in a Medicaid population. Am J Manag Care 2005;11(4 Suppl):S121-S9

- Botulinum Toxin Type A (BOTOX). Summary of product characteristics. Marlow, UK: Allergan Holdings Limited

- Botulinum Toxin Type A (BOTOX). Summary of product characteristics. Westport, County Mayo, Ireland: Allergan Pharmaceuticals Ireland

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol 2012;188:2455-63

- National Collaborating Center for Women’s and Children’s Health commissioned by National Institute for Health Excellence. CG171. Urinary incontinence in women: the management of urinary incontinence in women. London, UK: RCOG Press at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2013

- Chapple C, Sievert KD, MacDiarmid S, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA 100 U significantly improves all idiopathic overactive bladder symptoms and quality of life in patients with overactive bladder and urinary incontinence: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Urol 2013;64:249-56

- Nitti VW, Dmochowski R, Herschorn S, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of patients with overactive bladder and urinary incontinence: results of a phase III, randomized, placebo controlled trial. J Urology 2013;189:2186-93

- XE currency converter. XE. http://www.xe.com/currencyconverter/. Accessed January 2016

- Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol 2006;50:1306-15

- Irwin DE, Milsom I, Kopp Z, et al. Symptom bother and health care-seeking behavior among individuals with overactive bladder. Eur Urol 2008;53:1029-39

- Odeyemi IA, Dakin HA, O’Donnell RA, et al. Epidemiology, prescribing patterns and resource use associated with overactive bladder in UK primary care. Int J Clin Pract 2006;60:949-58

- Chancellor MB, Migliaccio-Walle K, Bramley TJ, et al. Long-term patterns of use and treatment failure with anticholinergic agents for overactive bladder. Clin Ther 2013;35: 1744-51

- Clinical Guidance 40: the management of urinary incontinence in women [CG4]. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2006

- van Kerrebroeck PE, van Voskuilen AC, Heesakkers JP, et al. Results of sacral neuromodulation therapy for urinary voiding dysfunction: outcomes of a prospective, worldwide clinical study. J Urol 2007;178:2029-34

- Herbison GP, Arnold EP. Sacral neuromodulation with implanted devices for urinary storage and voiding dysfunction in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2:CD004202

- Wefer B, Ehlken B, Bremer J, et al. Treatment outcomes and resource use of patients with neurogenic detrusor overactivity receiving botulinum toxin A (BOTOX®) therapy in Germany. World J Urol 2010;28:385-90

- Public price (without VAT). Data on file. Allergan Limited, 2015

- Treatment indication Tracker W4. Data on file.Marlow, UK: Allergan Holdings Limited, 2014

- Weighted average GHM 11C051 (2012). Data on File. Marlow, UK: Allergan Holdings Limited, 2014

- Clinician-verified procedure cost data: Germany. Data on file. Marlow, UK: Allergan Holdings Limited, 2015

- Italia. Decreto Ministriale 18.12.2012 (GU n.23 del 28-1-2013 - Suppl. Ordinario n.8). Remunerazione prestazioni di assistenza ospedaliera per acuti, assistenza ospedaliera di riabilitazione lungodegenza post acuzie e di assistenza specialistica ambulatoriale

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Cálculos urinarios Clasificación Internacional de las Enfermedades, CIE9MC V13.01

- Payment by results in the NHS: Tariff for 2013-14. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/payment-by-results-pbr-operational-guidance-and-tariffs. Accessed January 2016

- Référentiel de coûts MCO. ScanSanté, 2012. http://www.scansante.fr/r%C3%A9f%C3%A9rentiel-de-co%C3%BBts-mco-2012. Accessed January 2016

- Clinician-verified procedure cost data: Italy and Spain. Data on file. Marlow, UK: Allergan Holdings Limited, 2015

- Arlandis S, Castro D, Errando C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sacral neuromodulation compared to botulinum neurotoxin a or continued medical management in refractory overactive bladder. Value Health 2011;14:219-29

- Dode X, Ruffion A, Denys P, et al. Évaluation coût conséquence d’une nouvelle approche thérapeutique par la toxine botulinique pour la prise en charge des patients neurologiques présentant une hyperactivité du detrusor. Journal de Pharmacie Clinique 2009;28:157-65

- Allergan Study 191622-095-520-096 Interim 2. Data on file. Marlow, UK: Allergan Holdings Limited, 2013

- Incontinence pad unit cost data: EU. Data on file. Marlow, UK: Allergan Holdings Limited, 2014

- Keine Angst vor Warteschlangen. Test.de, Germany. https://www.test.de/Inkontinenzeinlagen-Keine-Angst-vor-Warteschlangen-1294945-0/. Accessed January 2016

- Clinical guidance 148: urinary incontinence in neurological disease: management of lower urinary tract dysfunction in neurological disease. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2011

- Bot Plus 2.0 database. Madrid, Spain: Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos, http://www.portalfarma.com/profesionales/medicamentos/preciosmenores/Paginas/espacgenprecios.aspx. Accessed July 2013

- Kim HKS, Pathan S, Habashy D, et al. 8 year experience of OnabotulinumtoxinA (BTXA) injections for the treatment of non-neurogenic overactive bladder: are repeat injections worthwhile? BJU International 2013;111(S1 Suppl):13-119

- Fosfomycine trometamol, single dose. France: BDM IT. http://www.codage.ext.cnamts.fr/codif/bdm_it/index_presentation.php?p_site=AMELI. Accessed January 2016

- IMS combined BPI (retail) and HPA (Hospital) audits. Data on file, 2011

- Pharmastar. http://www.pharmastar.it/. Accessed July 2013

- British National Formulary 64. London UK: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press, 2012

- Italian Medicines Agency. http://www.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/it/content/tabelle-farmaci-di-classe-e-h-al-15102014. Accessed October 2014

- Clinician-verified unit costs: catheter without lubricant. Data on File. Marlow, UK: Allergan Holdings Limited, 2015

- LHU Tender results. Data on File. Marlow, UK: Allergan Holdings Limited., 2013

- Clinical guidance 171: the management of urinary incontinence in women. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013

- Population on 1st January by sex and single year age. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database. Accessed January 25, 2016

- Papanicolaou S, Pons ME, Hampel C, et al. Medical resource utilisation and cost of care for women seeking treatment for urinary incontinence in an outpatient setting: examples from three countries participating in the PURE study. Maturitas 2005;52S:S35-S47

- Fowler CJ, Auerbach S, Ginsberg D, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA improves health-related quality of life in patients with urinary incontinence due to idiopathic overactive bladder: a 36-week, doublé-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, dose-ranging trial. Eur Urol 2012;62:148-57

- Loveman C, Marsh RM, Morton RM, et al. Cost comparison of sacral nerve stimulation and onabotulinumtoxinA to manage urinary incontinence in patients with overactive bladder. Poster presented at 2014 British Association of Urological Surgeons Annual General Meeting, 23-26 June 2014, Liverpool, UK

- Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, et al. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well‐being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int 2008;101:1388-95