Abstract

Aims: To estimate the cost-effectiveness of a new strategy that uses an amino acid formula in the elimination diet of infants with suspected cow’s milk allergy (CMA).

Materials and methods: This pharmacoeconomic study was developed from the perspective of the Brazilian Public Healthcare System. The new strategy proposes using an amino acid formula in the diagnostic elimination diet of infants (≤24 months) with suspected CMA. The rationale is that infants who do not respond to the amino acid formula do not suffer from CMA. Patients with a positive oral challenge test receive a therapeutic elimination diet based on Brazilian Food Allergy Guidelines. This approach was compared to the current recommendations of the Brazilian Food Allergy Guidelines. A decision model was constructed using TreeAge Pro 2012 software. Model inputs were based on a literature review and the opinions of a panel of experts. A univariate sensitivity analysis of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios was performed.

Results: The mean cost per patient of the new amino acid formula strategy was R$3,341.57, while the cost of the current Brazilian guidelines strategy was R$3,641.08. The mean number of symptom-free days per patient, which was used as an indicator of effectiveness, was 900.6 and 875.7 days, respectively. The new strategy is, therefore, dominant. In the sensitivity analysis, the dominance was maintained with parameter variation.

Limitations: In the absence of information in the literature, some premises were defined by a panel of specialists.

Conclusions: The new strategy, which uses an amino acid formula in the elimination diagnostic diet followed by an oral food challenge, is a dominant pharmacoeconomic approach that has a lower cost and results in an increased number of symptom-free days.

Introduction

Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) has a significant economic impact on public and private healthcare resources. However, only a few recent articles have evaluated the management of CMA from an economic perspectiveCitation1–7. The clinical presentation of CMA is variable, and none of its clinical manifestations are pathognomonic. Therefore, CMA symptoms may mimic those of other disorders, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, infant colic, chronic diarrhea, constipation, metabolic disease, and intestinal infectionsCitation8–13. A cow’s milk elimination diet that is followed by clinical improvement and a positive oral food challenge test is the best strategy for diagnosing CMACitation8–13. Several guidelines define the type of substitute formula that should be used in infants suspected of having CMACitation8–14. Similar to those guidelines, the Brazilian Food Allergy GuidelineCitation9 recommends that the first option that should be used as a diagnostic elimination diet for non-breastfed infants is an extensively hydrolyzed formula or soy protein formula in infants older than 6 months who have IgE-mediated CMACitation9.

Extensively hydrolyzed formulas are hypoallergenic. These and soy formulas are not entirely allergen-free, therefore full recovery is not achieved in all patientsCitation15–17. As a result, formulas may need to be switched, which extends the symptomatic period and diagnostic process. However, amino acid formulas are allergen-free and are tolerated by all infants with CMACitation8,Citation9,Citation12,Citation18,Citation19. Therefore, amino acid formulas promote clinical improvement in all allergic patients, which allows a CMA diagnosis to be excluded earlier in patients who fail to respond to the therapyCitation12,Citation18. Nevertheless, because of the higher cost of these formulas, they are typically reserved for more severe cases or for patients who cannot tolerate extensively hydrolyzed and/or soy formulasCitation10,Citation13,Citation19.

The present pharmacoeconomic study was conducted based on the following premises: (1) in general, CMA guidelines recommend first using extensively hydrolyzed formulas (efficacy ≅90%) before substituting with amino acid formulas (efficacy ≅ 100%) in severe cases and in patients who do not respond to extensively hydrolyzed formulasCitation8–14; and (2) a lack of response to an amino acid formula makes a diagnosis of CMA unlikelyCitation12,Citation18. Thus, the aim of this study was to estimate the cost-effectiveness of implementing a new strategy in which an amino acid formula is used instead of extensively hydrolyzed or soy formulas as the diagnostic elimination diet in infants with suspected CMA. This approach was compared to the recommendations of the Brazilian Food Allergy GuidelinesCitation9.

Methods

Study design

This pharmacoeconomic study was developed from the perspective of the Brazilian Public Healthcare System (“Sistema Único de Saude - SUS”) to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of a new strategy in which an amino acid formula is used as the diagnostic elimination diet followed by an oral food challenge for diagnostic confirmation. Patients with a positive challenge were switched to an extensively hydrolyzed or soy formula, on which they completed 6 months of a therapeutic elimination diet based on the Brazilian Food Allergy GuidelinesCitation9. For therapeutic elimination diets, amino acid formulas are currently recommended only for patients who are intolerant to extensively hydrolyzed formulas. New challenges are performed every 6 months to determine whether cow’s milk tolerance has been achieved. The proposed strategy uses an amino acid formula as the diagnostic elimination diet followed by an oral food challenge for diagnosis. The results of using this strategy were compared to the results of following the recommendations of the Brazilian Food Allergy GuidelinesCitation9. Model inputs were based on a literature review and the opinions of a panel of experts. Only direct costs were considered. A univariate sensitivity analysis of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios was performed.

Decision model

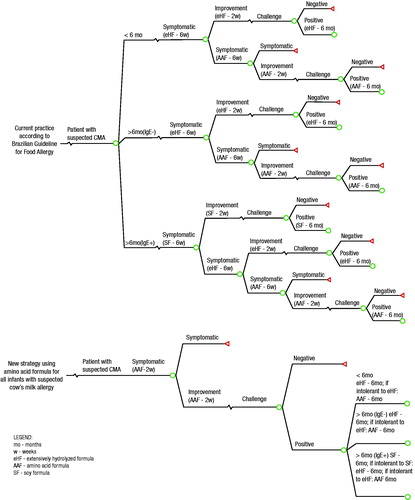

A decision model was constructed using TreeAge Pro 2012 software (TreeAge Software, Inc., Williamstown, MA), a modeling tool that is accepted by the scientific community and regulatory agencies as a standard modeling platform that supports cost-effectiveness analyses. Two decision trees were constructed: one for the current practice, which follows the Brazilian Food Allergy GuidelinesCitation9, and another for the new strategy, which uses the amino acid formula as the diagnostic elimination diet followed by an oral food challenge (). The Brazilian Food Allergy Guidelines is the main reference for the supply of formulas by the Brazilian public healthcare system. This guidelineCitation9 recommends 8 weeks of a diagnostic elimination diet with an extensively hydrolyzed formula or soy formula prior to the oral food challenge.

Figure 1. Decision tree showing the strategy used to manage infants suspected of having a cow’s milk allergy according to the Brazilian Food Allergy Guidelines and the new strategy, which used an amino acid formula in the diagnostic elimination diet.

Because amino acid formulas can relieve symptoms in as little as 2 weeksCitation16, a 4-week period on a diagnostic elimination diet with the amino acid formula was estimated to be effective for most patientsCitation20. This assumption was consistent with the ESPGHAN GI Committee’s practical guidelines, which were published in 2012Citation12.

The flow of care that is adopted for infants with suspected CMA in the pharmacoeconomic models is described in Supplementary Material 1. In current practice, according to the Brazilian guidelines, an oral food challenge is performed in patients who experience symptomatic relief after 8 weeks on an elimination dietCitation9. In the event of a negative challenge test (i.e. no symptom recurrence over 14 days), the patient is dropped out of the model. In the event of a positive test (i.e. recurrence of symptoms at any time), a diagnosis of CMA is confirmed. The therapeutic elimination diet is reintroduced with the same formula that was previously tolerated (either soy formula, extensively hydrolyzed formula or amino acid formula). The oral food challenge is then repeated every 6 months up to 36 months of age to determine whether tolerance to milk has been achieved. If one of these challenges produces a negative result, the patient is dropped out of the model.

The new strategy for obtaining diagnoses using an amino acid formula differs from the Brazilian guidelines only in its duration and the type of formula that is used in the diagnostic elimination diet. In this new strategy, the formula used in the diagnostic elimination diet consisted of an amino acid formula for 4 weeks instead of 8 weeks, the latter of which is recommended by the Brazilian guidelines. After using the amino acid formula as the diagnostic elimination diet for 4 weeks, the challenge and the therapeutic elimination diet (for those patients with a confirmed diagnosis) were applied according to the Brazilian guidelinesCitation9.

Model inputs were obtained from evidence published in the medical literature. In the absence of published data, the opinions of a panel of experts in pediatrics, allergy, gastroenterology, and nutrition were included. Only non-breastfed infants were included, because hypoallergenic formulas are not required when breastfeeding is available.

The prevalence of suspected CMA was 6.7%Citation21. Twenty-three per cent of the children were breastfed and, therefore, excludedCitation21. The decision tree simulation included a population that was followed up until they reached 3 years of age in consideration for the elevated percentage of patients who are tolerant to cow’s milk protein (87%) at that ageCitation21. The clinical and epidemiological features used in this pharmacoeconomic study are described in .

Table 1. Clinical and epidemiological data used to construct the decision model.

Given the multiple possible differential diagnoses and the lack of pathognomonic symptomsCitation8–13, only one-third of the suspected cases result in a confirmed diagnosis of CMACitation18,Citation21. The remaining two-thirds of the patients may experience the following: (1) improvement while on the elimination diet but no confirmation of a diagnosis of CMA during the oral food challenge test; or (2) no response during the diagnostic elimination diet. Given that the literature is unclear about the proportions of these two outcomes that should be expected, a value of 50% was adopted by the panel of experts based on studies conducted in BrazilCitation32 and in the NetherlandsCitation18.

A period of symptoms was calculated to input the costs, including drug treatment and medical consultations. In this estimate, we assumed that a 14-day period would cover the relief of symptoms in patients with a successful response to the elimination dietCitation12,Citation16,Citation20 in both decision trees. The duration of symptoms was also important for calculating the symptom-free time, which was considered the more important outcome.

Based on the opinions of the panel of experts, the frequency of medical consultations was established at two consultations per month for symptomatic patients and one per month for non-symptomatic patients.

Only direct costs were considered (i.e. drugs, hospitalizations, medical consultations, laboratory tests, and formulas). Values were based on a national epidemiological study that covered all five regions of BrazilCitation22 and on other published data. These data were complemented by the opinions of the panel of experts. Full payment by the public healthcare system was considered ().

Table 2. Unit resource costs (Currency: Brazilian real, 1 R$= 2.3 US dollars).

The prices of the hypoallergenic formulas () corresponded to government purchases (public tenders) made in 2012 and 2013. The cost in Brazilian Reals (R$) for each can of soy, extensively hydrolyzed, and amino acid formula was R$18.50, R$85.18, and R$166.57, respectively (1.00 USD = R$2.30)Citation34. The weekly consumption that was assumed for patients who were 0–6 months of age (1.6 cans/week = 640 g) and 6–24 months of age (2.1 cans/week = 840 g) were based on energy requirements and the estimated daily intake of breast milkCitation35.

Drug prices were collected from the Ministry of Health cost bankCitation34, from which we obtained the mean published prices. All other financial values were obtained from the Brazilian management system for drugs and procedures (SIGTAP – Sistema de Gerenciamento da Tabela de Procedimentos, Medicamentos e OPM do Sistema Único de Saúde)Citation33. To calculate drug dosages, body weight was defined as 6 kg for infants younger than 6 months old and 8.8 kg for older infants.

Outcome

The resulting incremental cost/effectiveness ratio was demonstrated as the cost per clinical symptom-free period of time. In light of the Brazilian directives for economical evaluations, a discount rate of 5% was applied to the costs and outcomes because the timeframe was greater than 1 year. Monetary indices are reported in local currency (Brazilian Real, 2014).

The total Brazilian population of infants (24 months old and younger) in 2014 was 4,586,658 according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and StatisticsCitation36. The prevalence of suspected CMA was 6.7%. Of these patients, 23.0% were excluded because they were exclusively breastfed. Therefore, the number of infants with suspected CMA was expected to be 236,626 infants per year.

Sensitivity analysis

A univariate sensitivity analysis was conducted to clarify the inherent uncertainty in the model parameters. The single clinical and cost variables associated with the new diagnostic strategy (using the amino acid formula) were remodeled based on minimum and maximum estimated values. Variables were moved up and down within a range of 25%, with the exception of clinical and formula efficacy, which had a range of 10%.

Results

shows the detailed clinical and economic results of using both strategies in infants with suspected CMA. The new strategy of using an amino acid formula in the diagnostic elimination diet had a lower cost than the clinical management plan that followed the Brazilian Food Allergy Guidelines. The analysis of the duration of the symptomatic period also revealed advantages. Therefore, the new strategy of using an amino acid formula in the diagnostic elimination diet followed by an oral challenge test was dominant (i.e. it had lower costs and higher effectiveness).

Table 3. Cost-effectiveness according to the mean of the cohort used in the model.

The new strategy was associated with a shorter symptomatic period (24.9 days) and lower costs (R$299.51 per patient). Given the expectation that, each year, 236,626 Brazilian infants with suspected CMA will need to be managed until they are 3 years old, the financial savings would reach R$70,871,853 if all of the infants with suspected CMA received medical assistance in the public health system. Additionally, the number of symptom-free days would increase from 207,213,388 to 213,105,375 days. Other potential savings, such as workday savings, improved quality-of-life, and other variables, were not analyzed in the model. In both models, the substitute formula (soy, extensive hydrolyzed or amino acid) represented ∼95% of the total cost, while laboratory tests, visitations, and oral challenge tests accounted for ∼5% of the total costs. Drugs represented less than 0.5% of the total costs (Supplementary Material 2).

The sensitivity analysis (one-way univariate) demonstrated that costs were most sensitive to the following changes: (1) the probability of improvement in subjects fed an amino acid formula in whom CMA was not confirmed, (2) the probability of improvement in subjects fed an extensively hydrolyzed formula with confirmed CMA, and (3) the cost of extensively hydrolyzed formulas. Therefore, the efficacy of both formulas and the cost of the hydrolyzed formula were the parameters that most substantially impacted final costs. Nevertheless, the sensitivity analysis showed that the new strategy was cost-saving, even when the parameters varied, and that it provided a strong benefit to patients. The graphic representation of the sensitive analysis is presented in Supplementary Material 3.

Discussion

Our study developed a pharmacoeconomic model to assess the cost-effectiveness of a new strategy for treating infants with suspected CMA. This strategy employs an amino acid formula in the diagnostic elimination diet. The model was based on the published literature as well as the opinions of a panel of experts. This new strategy would result in lower direct costs and provide more symptom-free days than the strategy recommended by the Brazilian Food Allergy GuidelinesCitation9. The new strategy is, therefore, dominant, based on a pharmacoeconomic point of view. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first pharmacoeconomic study to analyze the use of an amino acid formula in the diagnostic elimination diet.

The main premise of our model is that an improvement in symptoms after 4 weeks on a diagnostic elimination diet supports a clinical suspicion of CMA. By assuming, in our model, that all patients with CMA would improve after 4 weeks of treatment with an amino acid formula, we strongly approached the results presented by Dupont et al.Citation37. In their studies, they evaluated the roles of thickened (TAAF) or regular amino acid (RAAF) formulas in patients with CMA who did not respond to extensively hydrolyzed formula. They reported that, after 1 month, there was a complete resolution of the major CMA symptom in 61.9% and 51.5% of infants in the TAAF and RAAF groups, respectivelyCitation37. After 3 months, the dominant allergic symptom had disappeared in 76.2% of the infants in the TAAF group and 51.5% of the infants in the RAAF groupCitation38. However, after 1 month of treatment, 96% of the patients displayed a partial improvement, and these patients were maintained on amino acid formula until the end of the study period (3 months of treatment)Citation37. These findings confirm the premise put forward in our model, i.e. that using amino acid formula leads to clinical improvement in almost all patients with suspected CMA.

Few studies have been published on the pharmacoeconomic aspects of managing CMA, and they have tended to explore different scenarios according to the specific characteristics of the health systems of the countries in which the studies were conductedCitation1–7. In most of them, as in our study, the model was constructed based on information obtained from the literature and/or the opinions of a panel of experts. Two studies from the UK are potential exceptionsCitation3,Citation4. These studiesCitation3,Citation4 extracted information from a data bank into which information was input by general practitioners (“The Health Improvement Network”, THIN).

The first studyCitation3 that used the THIN database revealed that 60% of all infants were treated with soy formula, 18% were treated with extensively hydrolyzed formula, and 3% were treated with an amino acid formula. This ratio of clinical management strategies is not consistent with the current guidelines for the treatment of CMA. Another characteristic of these studies was the lack of obtaining a diagnostic confirmation using an oral food challenge test. The inclusion of the challenge test for diagnosing a cow’s milk allergy in the pharmacoeconomic model of our study followed the recommendations described in several guidelinesCitation8–13. If the correct diagnosis is not established using the challenge test, the costs associated with special formulas increase considerably because all infants suspected of having cow’s milk allergies are fed a special formula until they are at least 1 year old.

The second studyCitation4 that used the THIN database assessed the cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolyzed formula in comparison to using an amino acid formula as the first-line treatment for CMA from the perspective of the National Health Service in the UK. In this study, the incremental cost of starting treatment with an amino acid formula instead of an extensively hydrolyzed formula accounted for an additional cost requirement of four medical consultations and a 147% increase in the cost of the formula itselfCitation4. The authors also highlighted the fact that few patients underwent an oral food challengeCitation4. This limitation has been discussed in the literatureCitation39. When evaluating these results, the fact that infants with CMA were not randomized to receive both types of formula must be considered. Therefore, it is possible to speculate that the amino acid formula was prescribed to the patients with more severe clinical manifestations, despite similarities in admission data between patients. Another interesting aspect that may have influenced the results of the economic evaluation that was performed in the UK studyCitation4 was that the patients who received an amino acid formula and did not exhibit a clinical recovery remained in the model until the end of the observation period. In addition, the cost of H2 receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors was added in these models, which potentially increased costs. A lack of response to an amino acid formula and a complete cow’s milk elimination diet should exclude a diagnosis of CMACitation12,Citation18,Citation39. Thus, other causes that might explainthe observed clinical manifestations must be investigated.

Recent publications have assessed the pharmacoeconomic impact and potential effect of adding Lactobacillus rhamnosus GGCitation40 to formulas containing extensively hydrolyzed casein to support the development of immunologic tolerance in patients in the healthcare systems of ItalyCitation5, SpainCitation6, and the USCitation7. However, according to the authors, a randomized and controlled study must be performed in children who receive a probiotic-containing formula before the conclusions of these articles can be confirmedCitation5–7.

In addition to the initial prescription of the amino acid formula in our pharmacoeconomic model, we considered the oral food challenge to be very important. Patients who did not exhibit clinical improvement were excluded from the model because a diagnosis of CMA could be eliminated in these patients. Of note, for any elimination diet to be successful—either for diagnosing or treating CMA—it is important for cow’s milk proteins to be completely eliminated from the diet, including complementary food items.

It must be emphasized that, if the oral food challenge was not performed after 4 weeks on the diagnostic elimination diet to confirm the diagnosis, an important proportion of the patients would have been maintained in the model, which would have increased the costs resulting from the need to maintain these patients on special formulas and to perform additional medical consultations. Additionally, these patients would not be assessed to determine the additional causes of their clinical manifestations. Thus, when considering such pharmacoeconomic analyses, the costs associated with special formulas, medical assistance, and diagnostic tests and the lack of diagnostic confirmation via oral food challenge must be considered. Therefore, when managing infants with suspected CMA, it is essential to perform an oral food challenge test.

Our and other studiesCitation1–7 that have explored CMA pharmacoeconomics have some limitations. The proposed strategy of using AAF to diagnose CMA is novel, and we found no appropriate previous studies with which to compare results. Furthermore, some of the premises in this study were established by a panel of experts because there were no data available in the literature. The univariate sensitivity analysis showed that this new strategy is a superior pharmacoeconomic approach that has a lower cost and results in a higher number of symptom-free days than the clinical management plan that is currently suggested by the Brazilian Food Allergy Guidelines. Additionally, our analysis did not include an evaluation of the impact of diet on the quality-of-life or improvement in the general well-being of the infants with CMA or their parents. Changes in patient behavior and social costs, such as a caregiver’s absenteeism from work or expenses related to trips to the hospital and clinics, were not included because these factors were beyond the scope of this investigation. Consequently, this study potentially under-estimated the burden that CMA imposes on society as a whole.

The possibility of experiencing a reaction to extensively hydrolyzed protein formulas may be higher in non-IgE mediated reactions, which may reach a prevalence of 29%Citation15,Citation16, than in IgE-mediated reactions, which affect from 2–10% of patientsCitation16,Citation17. In our pharmacoeconomic model, we used 10% as the value for these reactions because this value was mentioned in important guidelinesCitation10,Citation12. Future studies might be able to assess the potentially pharmacoeconomic differences that are associated with each type of CMA.

For parents of an individual child, it may not make any sense to switch from the amino acid formula to another option, which risks the recurrence of CMA symptoms. In addition, the child may refuse the extensively hydrolyzed protein or soy-based formula because of its flavor, or the parents may report the onset of fictitious symptoms. However, there are no published reports on the frequency of such behaviors to justify their inclusion in our assumptions. Therefore, in our pharmacoeconomic model, the public healthcare perspective prevailed, and the chosen approach was to transition all patients with confirmed CMA to less costly formulas, leaving the amino acid formula for only the patients who displayed a recurrence of clinical manifestations when using other alternatives.

The most significant difference in the sensitivity analysis was associated with a variable that was recommended by the panel of experts. However, despite these limitations, the univariate sensitivity analysis robustly indicated that the strategy of using an amino acid formula was superior to the strategy proposed as the recommended practice in the Brazilian guidelines under all circumstances. Therefore, a global expenditure evaluation should be performed to evaluate the economic impact of CMA instead of only the unitary price of special formulasCitation41.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrated that a diagnostic strategy that uses an amino acid formula followed by an oral challenge test offers cost savings and reduces the duration of the symptomatic period once CMA is diagnosed, or allows CMA to be excluded earlier. Given this difference, an effective treatment can be established over a shorter period of time, which reduces expenses and shortens the duration of symptoms. The earlier exclusion of a CMA diagnosis in a sub-group of infants also allows the investigation of other diseases to take place. These findings collectively support the use of amino acid formulas in the diagnostic elimination diet followed by an oral food challenge test for CMA as a dominant strategy from both clinical and pharmacoeconomic points of view.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Support Advanced Medical Nutrition, a Danone group company.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MBM, JVS, MCV, ALC, and APMC are consultants and speakers for Support Advanced Medical Nutrition. OC and AN are employees of Evidências, which is a company that is specialized in Pharmacoeconomics that was contracted by Support Advanced Medical Nutrition to develop this pharmacoeconomic model. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental material

Download MS Word (95.9 KB)References

- Guest JF, Valovirta E. Modelling the resource implications and budget impact of new reimbursement guidelines for the management of cow milk allergy in Finland. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:1167-77

- Sladkevicius E, Guest JF. Budget impact of managing cow milk allergy in the Netherlands. J Med Econ 2010;13:273-83

- Sladkevicius E, Nagy E, Lack G, et al. Resource implications and budget impact of managing cow milk allergy in the UK. J Med Econ 2010;13:119-28

- Taylor RR, Sladkevicius E, Panca M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolysed formula compared to an amino acid formula as first-line treatment for cow milk allergy in the UK. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2012;23:240-9

- Guest JF, Panca M, Ovcinnikova O, et al. Relative cost-effectiveness of an extensively hydrolysed casein formula containing the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in managing infants with cow’s milk allergy in Italy. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2015;7;325-36

- Guest JF, Weidlich D, Mascuñan Díaz I, et al. Relative cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolysed casein formula containing the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in managing infants with cow’s milk allergy in Spain. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2015;7:583-91

- Ovcinnikova O, Panca M, Guest JF. Cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolysed casein formula plus the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG compared to an extensively hydrolysed formula alone or an amino acid formula as first-line dietary management for cow’s milk allergy in the US. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2015;7:145-52

- Vandenplas Y, Brueton M, Dupont C, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants. Arch Dis Child 2007;92:902-8

- Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria, Sociedade Brasileira de Alergia e Imunopatologia. Consenso Brasileiro Sobre Alergia Alimentar. Rev Bras Alerg Imunopatol 2008;31:64-89

- Fiocchi A, Brozek J, Schünemann H, et al. World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow’s Milk Allergy (DRACMA) guidelines. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2010;21(Suppl. 21):1-125

- NIAID-Sponsored Panel, Boyce JA, Assa’ad AW, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126(6 Suppl):S1-S58

- Koletzko S, Niggemann B, Arato A, et al. Diagnostic approach and management of cow’s-milk protein allergy in infants and children: ESPGHAN GI Committee practical guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;55:221-9

- Venter C, Brown T, Shah N, et al. Diagnosis and management of non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy in infancy – a UK primary care practical guide. Clin Transl Allergy 2013;3:23

- Kemp AS, Hill DJ, Allen KJ, et al. Guidelines for the use of infant formulas to treat cows milk protein allergy: an Australian consensus panel opinion. Med J Aust 2008;188:109-12

- Latcham F, Merino F, Lang A, et al. A consistent pattern of minor immunodeficiency and subtle enteropathy in children with multiple food allergy. J Pediatr 2003;143:39-47

- Hill DJ, Murch SH, Rafferty K, et al. The efficacy of amino acid-based formulas in relieving the symptoms of cow’s milk allergy: a systematic review. Clin Exp Allergy 2007;37:808-22

- du Toit G, Meyer R, Shah N, et al. Identifying and managing cow’s milk protein allergy. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2010;95:134-44

- Petrus NC, Schoemaker AF, van Hoek MW, et al. Remaining symptoms in half the children treated for milk allergy. Eur J Pediatr 2015;174:759-65

- Caffarelli C, Baldi F, Bendandi B, et al. Cow’s milk protein allergy in children: a practical guide. Ital J Pediatr 2010;36:5

- Lozinsky AC, Meyer R, De Koker C, et al. Time to symptom improvement using elimination diets in non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2015;26:403-8

- Høst A, Halken S, Jacobsen HP, et al. Clinical course of cow’s milk protein allergy/intolerance and atopic diseases in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2002;13(Suppl 15):23-8

- Vieira MC, Morais MB, Spolidoro JV, et al. A survey on clinical presentation and nutritional status of infants with suspected cow’ milk allergy. BMC Pediatr 2010;10:25

- Isolauri E, Sutas Y, Makinen-Kiljunen S, et al. Efficacy and safety of hydrolyzed cow milk and amino acid-derived formulas in infants with cow milk allergy. J Pediatr 1995;127:550-7

- Sampson HA, James JM, Bernhisel-Broadbent J. Safety of an amino acid-derived infant formula in children allergic to cow milk. Pediatrics 1992;90:463-5

- Caffarelli C, Plebani A, Poise C, et al. Determination of allergenicity to three cow’s milk hydrolysates and an amino acid-derived formula in children with cow’s milk allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 2002;32:74-9

- Ragno V, Giampietro PG, Bruno G, et al. Allergenicity of milk protein hydrolysate formulae in children with cow’s milk allergy. Eur J Pediatr 1993;152:760-2

- Isolauri E, Sutas Y, Salo MK, et al. Elimination diet in cow’s milk allergy: risk for impaired growth in young children. J Pediatr 1998;132:1004-9

- Giampietro PG, Kjellman NIM, Oldaeus G, et al. Hypoallergenicity of an extensively hydrolyzed whey formula. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2001;12:83-6

- Klemola T, Vanto T, Juntunen-Backman K, et al. Allergy to soy formula and to extensively hydrolyzed whey formula in infants with cow’s milk allergy: a prospective, randomized study with a follow-up to the age of 2 years. J Pediatr 2002;140:219-24

- Bhatia J, Greer F, Committee on Nutrition. Use of soy protein-based formulas in infant feeding. Pediatrics 2008;121:1062-8

- Zeiger RS, Sampson HA, Bock SA, et al. Soy allergy in infants and children with IgE-associated cow’s milk allergy. J Pediatr 1999;134:614-22

- Lins M, Horowitz MR, Silva GA, et al. Oral food challenge test to confirm the diagnosis of cow’s milk allergy. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2010;864:285-9

- SIGTAP. Management system for drugs and procedures [Internet]. SIFTAP-SUS. http://sigtap.datasus.gov.br/tabela-unificada/app/sec/inicio.jsp. Accessed December 10, 2014

- Health cost bank (BPS) [Internet]. Ministry of Health (Brazil). http://aplicacao.saude.gov.br/bps/login.jsf. Accessed December 10, 2014

- Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria, Departamento de Nutrologia. Manual de orientação para a alimentação do lactente, do pré-escolar, do escolar, do adolescente e na escola. 3rd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria; 2012. p. 95-6

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [Internet]. Projeção da população do Brasil por sexo e idade: 2000–2060. http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/projecao_da_populacao/2013/default_tab.shtm. Accessed December 10, 2014

- Dupont C, Kalach N, Soulaines P, et al. A thickened amino-acid formula in infants with cow’s milk allergy failing to respond to protein hydrolysate formulas: a randomized double-blind trial. Paediatr Drugs 2014;16:513-22

- Dupont C, Kalach N, Soulaines P, et al. Safety of a new amino acid formula in infants allergic to cow’s milk and intolerant to hydrolysates. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015;61:456-63

- Petrus NC, Hulshof L, Rutjes NW, et al. Response to: cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolysed formula compared to an amino acid formula as first-line treatment for cow milk allergy in the UK. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2012;23:686

- Canani RB, Nocerino R, Terrin G, et al. Formula selection for management of children with cow’s milk allergy influences the rate of acquisition of tolerance: A prospective multicenter study. J Pediatr 2013;132:771-7

- Terracciano L, Schünemann H, Brozek J, et al. How DRACMA changes clinical decision for the individual patient in CMA therapy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;12:316-22