Abstract

Background: In 2011 the first payment-by-results (PbR) scheme in Catalonia was signed between the Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO), the Catalan Health Service, and AstraZeneca (AZ) for the introduction of gefitinib in the treatment of advanced EGFR-mutation positive non-small-cell lung cancer. The PbR scheme includes two evaluation points: at week 8, responses, stabilization and progression were evaluated, and at week 16 stabilization was confirmed. AZ was to reimburse the total treatment cost of patients that failed treatment, defined as progression at weeks 8 or 16.

Objective: To estimate the financial consequences of this PbR reimbursement model and determine the perception of the stakeholders involved in the agreement.

Methods: Differential drug costs between two scenarios, with and without the PbR, were calculated. A qualitative investigation of the organizational elements was performed by interviewing the parties involved in the agreement.

Results: Forty-one patients were included from June 2011 to October 2013 and assessed at two evaluation points. Clinical results were comparable to those observed in the pivotal studies of gefitinib. The difference in the cost of gefitinib using the PbR compared to the traditional purchasing scenario was 6.17% less at 8 weeks, 11.18% at 16 weeks and 4.15% less for the overall treatment. The PbR resulted in total savings of around €36,000 (€880 per patient). From an operational and organizational perspective, the availability of adequate data systems to measure outcomes and monitor accountability and the involvement of healthcare professionals were acknowledged as crucial.

Conclusions: Tangible and intangible benefits were identified with respect to the interests of the parties involved. This has led to the incorporation of innovation for patients under acceptable conditions.

Introduction

The incorporation of new treatments into the services provided by a healthcare system must achieve three goals in a balanced manner, namely patient access to effective innovative solutions, economic sustainability of the system, and reward for the innovator’s investmentCitation1. Therapeutic innovations are often associated with uncertainties that make it difficult to determine their value in clinical practice and, consequently, the priceCitation2,Citation3.

When there is uncertainty, incentive-based schemes, generally called risk-sharing agreements (RSA) or payment-by-results schemes (PbRs), which dynamically link the price of an innovation to the conditions of use and/or the results obtained in clinical practice, could be alternatives to traditional fixed payment schemesCitation2–6.

In Spain, the decision to include new treatments in the Basic Services Portfolio of the national health system and the price reimbursement decision and terms of access are national responsibilities. However, the decentralized regional healthcare systems in the autonomous communities of Spain are responsible for their own management and financing and for developing measures to ensure equality and efficient access.

The Catalan Health Service (CatSalut) is the institution responsible for ensuring public access and rights to national health system services for a population of 7.5 million people living in the region of Catalonia. The Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO) is a publ ic entity that coordinates and provides cancer care to 40% of the adult population of Catalonia through a multicenter organization that includes four reference centers and a coordinated network of 20 medium-complexity county hospitals.

The ICO is developing a drug management policy led by a Pharmacy Commission based on clinical evidence, clinical practice guidelines drawn up with active involvement of healthcare professionals, and an explicit strategy with respect to the pharmaceutical industry. This strategy aims to establish co-responsibility for results and partnership, and it is internally regulated through the Code of Relationships with the Pharmaceutical and Technology Industry approved by the governing bodies of the institution.

In 2011, the first PbR in Catalonia was signed between the ICO, CatSalut, and the pharmaceutical company, AstraZeneca, for the introduction of gefitinib in the treatment of adult patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with activating EGFR-TK mutations. Based on this initial experience, CatSalut has decided to support this model and, currently, the ICO has signed 10 PbRs with six pharmaceutical companies.

Gefitinib is a molecule for the treatment of NSCLC in a biomarker-preselected population with a low expected prevalence of use and short-term measurement of efficacy, as in standard clinical practice. In pivotal studies, gefitinib was associated with a response rate of >70% and a statistically significantly reduced risk of progression of 52% (HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.64)Citation7–9.

In our setting, the decision to establish a PbR for gefitinib arose from potential uncertainties identified by the Pharmacy Commission, and subsequent operational development of the agreement was based on existing clinical practice guidelinesCitation10. Uncertainties surrounding gefitinib are linked to the effectiveness of the compound in the Spanish population, as the pivotal studies were conducted in Asian patients. Moreover, the PbR was set up as a pilot scheme to provide valid conclusions about the usefulness and feasibility of developing such models. The use of gefitinib in advanced EGFR + NSCLC presents some features that could be helpful for the introduction of PbRs, such as a well defined clinical situation, relatively few patients, and foreseeable, easily monitored results.

The PbR agreement specified the eligibility criteria for treatment with gefitinib: newly diagnosed or already diagnosed EGFR-mutation positive NSCLC patients. Confirmed EGFR-mutation negative patients were not eligible.

The PbR we adopted is a scheme based on clinical findings in which payment for treatment is linked to a consensually agreed outcome. Treatment is initially paid for in full by the healthcare provider, but for those patients who have not achieved the specified outcome at the time of the assessment, the pharmaceutical company reimburses the healthcare provider with the entire cost of the treatment administered up to the evaluation point.

The main objective of this paper is to present the financial consequences of the application of this PbR. The secondary objective was to clarify the perceptions of stakeholders regarding the utility, feasibility and basic requirements for the introduction of PbRs from the perspective of the healthcare system.

Methods

The agreement formalizing the PbR was signed by CatSalut, the ICO and by extension its network of hospitals, and AstraZeneca. The diagnostic, eligibility and response criteria included in the PbR were those determined by the ICO clinical practice guidelinesCitation10 and by ICO specialists, in line with standard clinical practice. Likewise, a commission formed by the three stakeholders periodically assessed the results.

Analysis of the results of application of PbR

The evaluation period ran from June 2011 (inclusion of first patient) to October 2013. Information was recorded prospectively up to week 16 of treatment. Additionally, all patients still in treatment after week 16 were followed until treatment concluded. Data was monitored and results were evaluated using the ICO electronic prescribing system, which uses decision-making algorithms based on the clinical practice guidelines and outcome records.

Assessment of the financial consequences of PbR included both the reimbursements issued by AstraZeneca during the period evaluated and billing data until the completion of treatment.

There was no specific comparison group and the results could not be compared with previous conditions of use, since the drug was a new inclusion to the ICO drug guidelines. Therefore, the analysis was based on comparing the effects of the introduction of the PbR with those derived from a hypothetical scenario of usual purchasing without the PbR.

The results were quantified throughout the prospective follow-up of the patient cohort during the study period. Response to treatment with gefitinib was established according to the RECIST 1.1 criteriaCitation11 in two evaluation periods, corresponding to standard clinical practice. At week 8, partial and complete responses, stabilizations and progressions were assessed. Stable patients at week 8 were evaluated at week 16. For patients with treatment failure at week 8 or 16, considered as progression, or death attributable to the disease, or the suspension of gefitinib due to toxicity before week 16, AstraZeneca reimbursed the cost of treatment, which was terminated. The follow-up commission assessed the reimbursement individually.

For the purposes of the PbR, follow-up and data recording ended at week 16. After this, patients continued to be monitored according to standard clinical practice until the end of treatment, without financial consequences.

Financial consequences of the PbR

The analysis compares the real-world PbR scenario with a hypothetical traditional purchasing scenario.

All resources that could potentially be affected by the PbR were identified and the differences between the scenarios compared. The analysis quantifies and assesses the direct drug cost differences between the two alternatives; treatments reimbursed by the pharmaceutical company were included as avoided costs. Billing data and the number of units dispensed to enrolled patients were used to evaluate the final real cost of the treatments.

Related resources not strictly attributable to the PbR were not included in the calculations because they were resources that were used to improve the internal management of the center (on which the PbR has acted as a catalyst) or because they should be shared across different risk-sharing agreements given economies of scale for all the parties involved.

Three time periods were compared: up to week 8, between week 8 and week 16 in patients who were stable at week 8, and up to the end of treatment in patients that had not withdrawn from treatment prior to week 16. This showed the initial impact of the PbR in the follow-up period and the total net impact of treatment with gefitinib in the study group.

The analysis assumed that the drug use and the results derived (effectiveness) would be the same in both scenarios and that the price of the doses administered under the traditional purchasing scenario would be the official market priceCitation12. No comparative analysis of the potential effects of the PbR on the correct use of medication and health outcomes was performed due to the lack of quantifiable parameters.

Analysis of the strategic elements required for the development of the PbR

The process was also analyzed in order to identify possible areas for improvement in the implementation and follow-up of the contract and requirements for ensuring the transfer of PbR models from a specific (single hospital) to a generalized setting.

The qualitative assessment was conducted by a self-administered questionnaire completed by individuals involved in the contractual operations and by reviewing the agreement in terms of existing recommendationsCitation13.

The questionnaire was drawn up to collect relevant organizational and instrumental variables or elements, each of which was quantified by the participants on a Likert-type scale with a score of 1 to 5, where 1 indicates that the participant considers the item as unnecessary, 2 as of little importance, 3 as important but not essential, 4 as important and necessary, and 5 as essential in the operational development of a PbR. This questionnaire was administered to the eight professionals from the ICO (4), Catsalut (2) and AstraZeneca (2) involved in the development of the PbR.

Results

Forty-one patients treated with gefitinib between June 2011 and October 2013 were included. describes the characteristics of the study population. Mean age was 63.8 years (range 49–84 years), 69.3% (28 patients) were female, and 31.8% (13 patients) male. Only one (2.44%) patient was an active smoker, 29 were never smokers and 11 former smokers. All 41 patients had EGFR-positive tumors: 20 (48%) had the L858R mutation and 19 (46%) had an exon 19 deletion.

Table 1. Characteristics of the population included in the PbR.

Assessment of responses at weeks 8 and 16

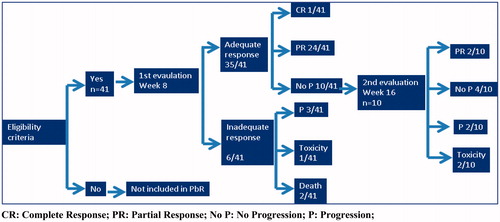

shows the results obtained in the period of application of the PbR. At week 8, an adequate response was obtained in 35/41 (85.37%) patients, of whom 24 (58.54%) had partial response, 1 (2.44%) complete response and 10 (24.39%) stable disease. Six patients (14.63%) failed treatment because of: disease progression (3 subjects [7.32%]); death (2 subjects [4.88%]); and withdrawal of treatment due to toxicity (1 subject [2.44%]).

At week 16, of the 10 patients with stable disease at week 8, 4 remained stable, 2 progressed to partial response, 2 had disease progression, and 2 others were withdrawn from treatment due to toxicity.

In summary, at week 16, 10 out of the 41 patients were regarded as treatment failures, as defined by the PbR (5 disease progression, 2 deaths and 3 withdrawals due to toxicity), whereas 31 had objective response or stable disease and continued therapy according to clinical practice until the end of treatment, without financial consequences.

Analysis of direct costs and resources in both scenarios

shows the effects of the PbR on the different potential uses of resources between the scenarios. The only differential costs identified were those corresponding to drug costs and administrative costs associated with the drawing-up, negotiating and follow-up of the agreement by all signatories. Although the use of gefitinib would be the same in both scenarios, the drug costs would differ due to reimbursement via the PbR. However, although administrative and follow-up costs were identified, they were not assessed or included in the analysis, since this agreement was conceived as a pilot scheme. Therefore, it is difficult to determine accurately the impact of these models when applied under normal conditions.

Table 2. Effects on resources in the scenarios compared.

Drug costs using the PbR compared to the traditional purchasing scenario were 6.17% lower at 8 weeks, 11.18% at 16 weeks and 4.15% lower for the overall treatment, taking into account the total number of doses administered to the cohort ().

Table 3. Direct costs of implementing the PbR.

The PbR resulted in total overall savings of around €36,000, which corresponds to approximately €880 per patient.

Areas in the agreement requiring improvement and perceived relevance of operational elements

The agreement, signed to give legal consistency to the PbR, was the first of its kind in Catalonia and might be improved. shows the elements of the signed contract.

Table 4. Content of the PbR agreement.

Some of the administrative and supervision terms of the agreement are simple. However, elements that might make the PbR universally applicable, such as conditions of use of the drug and the outcome measures, are appropriate, as the timeframe was short (between week 8 and 16) and outcomes were assessed according to standard clinical practice, in line with international recommendations.

The clinical conditions specified in the agreement are those indicated in the ICO Clinical Practice Guidelines drawn up by healthcare professionals. Consequently, the technical conditions for the application of the PbR were feasible, appropriate, and conformed to standard clinical practice.

The results from the questionnaire administered to the eight professionals from the three sectors involved in the PbR are shown in . From an operational and organizational perspective, the availability of adequate information technology to measure outcomes and monitor accountability were acknowledged as essential or critical to the development of dynamic payment models. The availability of diagnostic resources capable of complying with the legal framework and the agreements made was also considered essential. The responses of the various professionals were similar, regardless of the body to which they belonged.

Table 5. Elements essential for the development of a PbR: results of the questionnaire administered to involved professionals.

In organizational terms, four different aspects had the greatest importance, the first of which was leadership. This was understood as a managerial role embodied in a defined strategy for the center, in which PbRs are a consistent feature, forming the framework of the relationship with the pharmaceutical industry. Second was the involvement of professionals in defining the PbR in order to guarantee adherence; third, funding; and fourth, a suitably sized, appropriately prepared pharmacy department.

Discussion

The financial impact results (€36,000 overall saving or 4.15% reduction in billing) may seem limited. However, when deciding to use a PbR, the payer was not only concerned about the cost, but also about the initial uncertainties regarding the effectiveness of the product in the Spanish setting. The PbR allowed this uncertainty to be controlled and shared among the participants, ensuring that benefits would be close to those considered optimal by the payer or, at least, close to the payer’s willingness to pay.

Although the data were not included in the outcomes evaluation, the results obtained at week 16 in real-world clinical practice were in line with those obtained in the clinical development of the product and in the IFUM study (overall risk ratio: 70%; progression-free survival: 9.7 months)Citation7–9,Citation14.

As mentioned above, the ICO has an existing model for the management of innovation, set up by treating physicians. In generic terms, in Spanish hospitals, some aspects that are difficult to quantify may result from imposing a PbR agreement on a specific model of use, in specific patients, and with a specific outcomes evaluation. Questions remain as to what might happen in a standard clinical setting with regard to the number and type of patients included, possible variability of use, and whether the impact in terms of results and costs would be similar.

For example, in our case, if just 10% more patients initially expected to have unfavorable responses had been included, or if 10% of correctly selected patients with unfavorable responses at week 8 and 16 had continued treatment until the next evaluation, the costs generated would have been similar to those avoided by the PbR, and associated with questionable usage.

In short, the potential impact of the PbR in limiting the conditions of use of the therapy might have a much greater economic relevance than the reimbursement itself. Therefore, it is reasonable to suppose that if all agents (manufacturer, payer and healthcare professionals) act together, they could create an incentive for the optimally efficient application of treatment.

CatSalut and the ICO identify tangible and intangible benefits with respect to the interests of the various stakeholders. This has led to the incorporation of innovation for patients under acceptable conditions. In our case, the professionals involved were able to visualize the model properly because the PbR stipulated that access to gefitinib must be offered in a manner considered correct by all. Both the institution and the professionals acknowledged that the benefits of the experience included not only the potential gains in cost-effectiveness but also the additional factors derived from a more appropriate use of the product.

From the perspective of AstraZeneca, the PbR allowed the product to be introduced in a specific market under appropriate and agreed conditions of use. Under other conditions, this might have been delayed or hindered.

As the PbR was linked to only one service provider, there was a risk that the negotiations and conditions would be fragmented, which could have meant a major effort for the pharmaceutical company to gain market access. However, the involvement of the health authority demonstrates their openness to adopt a generalized perspective, resulting in a unique negotiating process for Catalonia, which could lead to the inclusion of other hospitals in such schemes.

We have not found any publications assessing the impact of PbR models on Spain as a whole, so we were unable to compare our results with any similar evaluations in our setting. Internationally, the only references we found evaluating impact of these models were Italian studiesCitation15,Citation16. The first article reports that PbRs used in Italy from 2007 to 2015, which included 26 drugs, generated the repayment of €121 million of the €3.696 billion (3.3%) spent by the public healthcare system. In the specific case of gefitinib in Italy, for the same indication and using the same type of PbR as in Catalonia, the repayment to the national health system was 4.8% of the total expenditure on this drug. These results are very similar to ours.

The low overall impact identified in the implementation of these schemes in Italy was due to other factors that should be considered, such as the different PbR models and the specific administrative inefficiencies of the system. These factors might account for up to 32% of the returns that should have been generated in 2012. Inefficiencies included data recording problems, administrative errors and legal disputes with the pharmaceutical companies. The authors propose that economic inefficiencies could be reduced by switching from “Pay for Results” models to the “Success Fee” model, based primarily on the concept that the pharmaceutical industry first provides the product for free, and the national health system only pays for the treatment after the agreed outcome has been achieved. This would save the national health system the initial outlay and administrative costs associated with processing the reimbursements.

The second article we citeCitation16 reports data from the AIFA on the impact of “Managed Entry Agreements” (MEA) in Italy in the year 2012. The basic quantitative data is the same as that used in the first articleCitation15, and includes an estimate of the costs invested in the development and follow-up of the MEAs (€8.7 million) derived from centralized data management. This article also includes a comparison between Italy, and England and Wales in the management of innovation, identifying different trends in both settings. Italy tends to develop outcome-based agreements, and England and Wales tend to prefer discounts and economic agreements. According to the authors, this is because the PbRs are very expensive to run, and thus are potentially inefficient. However, they do not provide data on the costs of management of these schemes in England and Wales, although they do include results from surveys estimating time spent on administrationCitation17,Citation18.

From our point of view, it is logical to outline the most efficient model of funding possible, but administrative and management costs derived from the agreements are difficult to extrapolate among different environments.

In our case, the setting in which the agreement was developed was selected because it already had organizational conditions that did not require any specific investment. The only additional costs were generated by the need to follow up the PbR agreement (two meetings in 2 years), and the administrative costs of the financial reimbursements. The professional costs reflected the 8 hours dedicated by ICO personnel (two physicians, 4 hours per meeting), less than €300 in total. The hospital considered the administrative costs as negligible, since they were grouped in three reimbursement procedures. It is obviously difficult to extrapolate these results to the overall healthcare system, to the implementation of PbR in different settings or to the configuration of centralized registry systems.

Two Italian studiesCitation19,Citation20 emphasized the importance of generating data to provide an incentive for these types of agreements. The generation of data is a direct though scarcely tangible benefit for the payer and, potentially, for the pharmaceutical industry itself.

Our PbR has generated a contractual model which has the limitations of an initial, pilot experience. However, the model was, in general, appropriate to the needs of the parties involved. The involvement of the healthcare authority and the use of clinical guidelines drawn up by healthcare professionals should be highlighted.

The essential instrumental elements needed for payers to develop a useful PbR included the rapid and efficient availability of data on economic and health outcomes, adequate access to diagnostic techniques, and a legal framework for the agreement in line with local legislation. The organizational elements considered essential were a defined management framework, coherent leadership in the development of the model, and the appropriate involvement of healthcare professionals in the definition of the clinical elements of the PbR.

One element included in other settings is the involvement of patients in these types of agreementCitation1. This aspect was taken into consideration by the ICO but was ruled out, since the use of the drug and the outcome evaluation model specified in the PbR were essentially the same as in standard clinical practiceCitation10 and, therefore, there were no consequences for the patients.

The PbR encountered some problems, even though the drug met criteria that were useful for developing the agreement. Appropriate organizational circuits had to be designed to access diagnoses when required, information technology and follow-up systems required some improvements, and a mechanism that enabled continuous monitoring of the PbR had to be established. However, all parties acknowledged that these organizational improvements were required for a results-oriented scenario and would have been necessary even without the PbR, which nonetheless clearly incentivized their introduction.

This pilot study suggests that PbR schemes should move beyond the framework of pilot tests and evolve within the national health system towards systematic implementation, taking into account all the elements that might potentially affect their introduction.

By agreeing to the PbR, the pharmaceutical company was able to generate experience and internal knowledge of the definition, implementation and monitoring of new ways of providing access to the innovation, potentially extending its application to other diseases, geographical areas or agents within the healthcare system.

This study has some limitations derived from its application in a real-world environment, making it impossible to control other factors that might affect the costs and outcomes of the use of gefitinib in the ICO. While the effects analyzed were a direct consequence of the PbR and, therefore, are directly attributable to it, it is difficult to predict the consequences of the alternative scenario.

The alternatives compared in the analysis were the real-world application of the PbR and a hypothetical traditional purchasing scenario. These are not the only possible scenarios, as other types of purchase agreements could have been adopted, such as discounts or financial RSAs.

However, in our case, the PbR was unlikely to modify clinical practice, since the criteria for use specified in the agreement were derived from the ICO clinical guidelines for NSCLC, and the ICO uses a prescription system which includes decision-making algorithms that align clinical practice to treatment guidelines. According to audits, the degree of adherence to the clinical practice guidelines in the ICO is over 95%.

The PbR has allowed the ICO and CatSalut to enhance their results-oriented drug management policy with the participation of healthcare professionals. The focus on co-responsibility for results has strengthened their changing relationship with the pharmaceutical industry, as demonstrated by the subsequent signing by the ICO of 10 additional PbRs to date.

The PbR has also introduced a standardized working dynamic to Catalonia that links the existing evaluation and harmonization mechanisms with the general purchasing model of the system, establishing general criteria to define which drugs may be candidates for PbR, their conditions of use, and a systematic policy for their application. This pilot study has led to the implementation of 18 PbRs in Catalonia and has established a standardized decision-making process with respect to the payment model, according to specific CatSalut guidelines for PbR schemesCitation21.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This manuscript was prepared via an unrestricted grant from AstraZeneca, Spain.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

S.S., L.A.C. and R.C. have disclosed that they are employees of AstraZeneca. L.S. has disclosed that he received an unrestricted grant from AstraZeneca, Spain, to prepare this manuscript. A.C, M.G, R.C, R.M, C.C, A.G, and J.R.G have disclosed that they have not significant relationships with or financial interests in any comercial companies to this study or article.

JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgement

Carles Forne of Oblikue Consulting for their support to the review of statistical data and to ICO pharmacy service by providing the necessary information for this article.

References

- Espin J, Oliva J, Rodríguez Barrios JM. Esquemas de mejora de acceso al mercado de nuevas tecnologías: los acuerdos de riesgo compartido. Gac Sanit 2010;24:491-7

- Carlson J, Sullivan S, Garrison L, et al. Linking payment of health outcomes: a taxonomy and examination of performance based reimbursement schemes between healthcare payers and manufacturers. Health Policy 2010;96:179-90

- Newman PJ, Chambers JD, Simon F, et al. Risk sharing arrangements that link payment for drugs to health outcomes are proving hard to implement. Health Affairs 2011;30:2329-37

- Adamski J, Godman B, Ofierska-Sujkowska G, et al. Risk sharing arrangements for pharmaceuticals: potential considerations and recommendations for European payers. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:153

- Pugatch M, Healy P, Chu R. Sharing the burden: could risk sharing change the way we pay for healthcare? Available at: http://www.stockholm-network.org/downloads/publications/Sharing_the_Burden.pdf [Last accessed 15 May 2015]

- Towse A. Value based pricing, research and development, and patient access schemes. Will the United Kingdom get it right or wrong? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010;70:360-6

- Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin – paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2009;361:947-57

- Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:121-8

- Maemodo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2380-8

- Institut Catalá d´Oncología. ICO Praxis para el tratamiento médico y con irradiación del cáncer de pulmón célula no pequeña. Barcelona: Generalitat de Cataluña, Departament de Salut, 2011. Available at: http://ico.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/ico/professionals/documents/arxius/icoprax__cpcnp_cast_def.pdf [Last accessed 7 September 2014]

- Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Canc 2009;45:228-47

- General Council of the Association of Official Pharmacists. General Council of the Association of Official Pharmacists Database: Bot PLUS 2.0. Available at: https://botplusweb.portalfarma.com/ [Last acessed 21 June 2016]

- Garrison LP, Towse A, Briggs A, et al. Performance-based risk-sharing arrangements – good practices for design, implementation, and evaluation: report of the ISPOR Good Practices for Performance-Based Risk-Sharing Arrangements Task Force. Value Health 2013;16:703-19

- Douilard J-Y, Ostoros G, Cobo M, et al. First-line gefitinib in Caucasian EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC patients: a phase-IV, open-label, single-arm study. Br J Canc 2014;110:55-62

- Navarria A, Drago V, Gozzo L et al. Do the current performance-based schemes in Italy really work? “Success Fee”: a novel measure for cost-containment of drug expenditure. Value Health 2015;18:131-6

- van de Vooren K, Curto A, Freemantle N, Garattini L. Market access agreements for anti-cancer drugs. J R Soc Med 2015;108:166-170

- British Oncology Pharmacy. A report into the uptake of patient access schemes (PAS) in the NHS. Available at: http://www.bopawebsite.org/contentimages/publications/Report_into_Uptake_of_Patient_Access_Schemes_8_11_09.pdf [Last accessed 27 October 2014]

- Haynes S, Timm B, Hamerslag L, Wong Grand Costello S. The administrative burden of patient access schemes in the changing UK healthcare system: a follow up study. Available at: http://www.costellomedical.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Madrid_Poster_PHP1521.pdf [Last acessed 22 April 2015]

- Garattini L, Casadei G. Risk sharing agreements: what lessons from Italy? Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2011;27:169-72

- Garattini L, Curto A, van de Vooren. Italian risk-sharing agreements on drugs: are they worthwhile. Eur J Health Econ 2015;16:1-3

- Segú Tolsa JL, Puig-Junoy J, Espinosa Tomé C, coordinadores. Guía para la Definición de Criterios de Aplicación de Esquemas de Pago basados en Resultados (EPR) en el Ámbito Farmacoterapéutico (Acuerdos de Riesgo Compartido). Versión 1.0. Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Salut, Servei Catalá de la Salut (CatSalut), 2014