Abstract

Objective: To compare the pharmacoeconomic guidelines in South Africa (SA) with other middle- and high-income countries.

Methods: A comparative review of key features of the pharmacoeconomic guidelines in SA was undertaken using the Comparative Table of Pharmacoeconomic Guidelines developed by the International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, and published country-level pharmacoeconomics guidelines. A random sample of guidelines in high- and middle-income countries were analyzed if data on all key features were available. Key features of the pharmacoeconomic guidelines in SA were compared with those in other countries, and divergent features were identified and elaborated.

Results: Five upper middle-income countries (Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Malaysia, and Mexico), one lower middle-income country (Egypt), and six high-income countries (Germany, Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Taiwan, and the Netherlands) were analyzed. The pharmacoeconomic guidelines in SA differ in important areas when compared with other countries. In SA, the study perspective and costs are limited to private health-insurance companies, complex modelling is discouraged and models require pre-approval, equity issues are not explicitly stated, a budget impact analysis is not required, and pharmacoeconomic submissions are voluntary.

Conclusions: Future updates to the pharmacoeconomic guidelines in SA may include a societal perspective with limitations, incentivize complex and transparent models, and integrate equity issues. The pharmacoeconomic guidelines could be improved by addressing conflicting objectives with policies on National Health Insurance, incentivize private health insurance companies to disclose reimbursement data, and require the inclusion of a budget impact analysis in all pharmacoeconomic submissions. Further research is also needed on the impact of mandatory pharmacoeconomic submissions in middle-income countries.

Introduction

The National Department of Health (NDoH) developed the Pharmacoeconomic Guidelines in South Africa (PGSA) in a dual healthcare system split between the public and private provision of healthcare services. Government agencies operate under-resourced public healthcare facilities and service ∼80% of an estimated population of 53 millionCitation1. Healthcare services for the remaining population is funded by employee and employer health insurance contributions collected and used by numerous private health insurance companies for private healthcare services. Private health insurance companies (aka medical aids or medical schemes) are mainly responsible for funding medicines in the private healthcare sector.

Medicines in South Africa are regulated by the Medicines and Related Substances Act (Medicines Act) which includes related policies on, among others, generic substitution, parallel importation, issuing licenses to dispensing doctors, and perverse incentives in the sale of medicines (bonuses, sampling, discounts). The Medicines Act governs medicines use in both the public and private sectors; however, the regulations on a transparent pricing system for medicines apply only to the private sector and activities thereunder are co-ordinated by a Pricing Committee of the NDoH including the determination of a medicine’s “therapeutic value”Citation2 (p.15).

Access to medicines in the private sector is also determined by the Medical Schemes Act that governs 83 medical schemes including prescribed minimum benefits (PMB)—statutory benefits that define access to basic services including medicines. PMB cover any medical emergency, 270 Diagnosis Treatment Pairs (e.g. Diagnosis: Cancer of prostate gland (treatable), Treatment: Medical and surgical management, which includes chemotherapy and radiation therapy), and 25 Chronic conditionsCitation3,Citation4. For instance, Discovery Health Medical Scheme, the largest voluntary health insurance company in South Africa, funds either $13,850 or $27,7011 a year depending on the insurance plan for each patient registered on the oncology programCitation5. The annual benefit covers chemotherapy and radiotherapy; CT, MRI, or PET-CT scans and x-rays; laboratory tests; consultations; treatment and related administration expenses; and fees billed by accredited cancer care facilitiesCitation5. The Medical Scheme will fund 80% of treatment expenses beyond the annual benefit and the remaining portion is self-funded by the oncology patient. However, any cost deducted from the annual benefit is “… subject to consideration of evidence-based medicine, cost effectiveness and affordability” and “… services … deemed … unaffordable and/or not cost-effective and/or lacking clinical evidence to demonstrate efficacy are excluded from cover”Citation5 (p. 4).

Access to newer cancer treatments such as biologics that are clinically effective but very expensive is a longstanding fault-line in the reimbursement of medicines in the private healthcare sectorCitation6,Citation7. Health insurance companies and pharmaceutical companies seldom agree on what is cost-effective and affordable treatment, or converge on an accepted application of evidence-based medicine. To partly address this gap, the PGSA published on February 1, 2013 aim to “… establish whether a medicine represents fair value for money” through a formal and transparent economic evaluation focused on new and existing medicines in the private healthcare sector, and medicines submitted for review may be found to be “… unreasonably priced …”Citation8 (p. 10). The purpose of this comparative review is to present how the PGSA compare to those in other middle and high-income countries. To our knowledge, this is the first review that benchmarks the PGSA among other guidelines in middle and high-income countries.

Methods

The International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Comparative Table of Pharmacoeconomic Guidelines was used to compare the PGSA with middle and high-income countries by key featuresCitation9. The Table is a reliable summary of key features of national pharmacoeconomic guidelines which are reviewed annually by in-country professionals and ISPOR membersCitation10. Key features include title and year of the document, affiliation of authors, purpose of the document, standard reporting format, disclosure, target audience of funding/author’s interests, perspective, indication, target population, sub-group analysis, choice of comparator, time horizon, assumptions required, preferred analytical technique, cost to be included, source of costs, modeling, systematic review of evidence, preference for effectiveness over efficacy, preferred outcome measure, preferred method to derive utility, equity issues stated, discounting costs, discounting outcomes, sensitivity analysis—parameters and range, sensitivity analysis—methods, presenting results, incremental analysis, total costs vs effectiveness (cost/effectiveness ratio), portability of results (generalizability), financial impact analysis, and mandatory or recommended or voluntary pharmacoeconomic guidelinesCitation11.

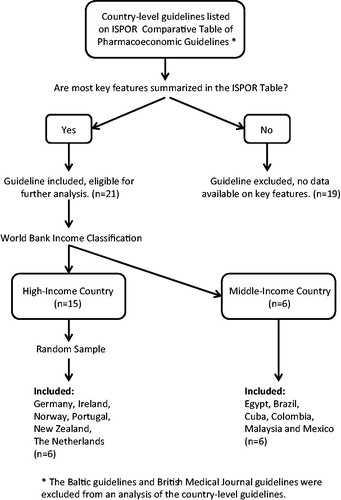

Country-level guidelines listed on the ISPOR Comparative Table were selected based on the availability of complete data on key features. All country-level guidelines were accessed from ISPOR online resources in English, Portuguese (Brazil), or Spanish (Mexico, Colombia, and Cuba)Citation11. Countries were grouped by categories on gross national income per capita developed by the World Bank. A random number generator in MS Excel was used to select six guidelines from high-income countries among the 15 eligible for further analysis. illustrates the inclusion/exclusion criteria applied to the ISPOR Comparative Table. MS Excel was used to summarize and compare key features of the PGSA with those of comparator guidelines and manual searches of guidelines were performed where data on key features was insufficiently nuanced. Key features of the PGSA congruent with the comparator guidelines were considered comparable to other guidelines and were not further explored; however, incongruent key features were identified and elaborated.

Results

The key features of the PGSA () are compared to pharmacoeconomic guidelines in five upper middle-income countries (Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Malaysia, and Mexico), one lower middle-income country (Egypt), and six high-income countries (Germany, Ireland, Norway, Portugal, New Zealand, and The Netherlands). A table of all the key features of the 12 comparator countries and the PGSA are available at http://carapinha.com/link/fulltable.

Table 1. Key features of the pharmacoeconomic guidelines in South Africa.

Study perspective and costs

The PGSA are limited to the “… pharmacoeconomic evaluation of new and existing medicines in the South Africa private healthcare sector …”Citation8 (p. 9) and recommend a third-party payer perspective, i.e. private health insurance companies. To adopt a broader perspective, the PGSA requires a strong case be put forward with a justification and rationale for including additional costs and how a broader perspective impacts the results of the analysis. In contrast, all high-income countries require a societal perspective—Portugal stipulates that the societal perspective should be disaggregated into a third-party payer perspective (covering public and private payers), Norway imposes some limitations on a societal perspective (e.g. treatment impact on productivity gains and costs are not compulsory), The Netherlands requires that an analysis including and excluding productivity costs be performed based on the friction-cost method, and Taiwan recommends that all costs and benefits outside the health insurance payment system be included. All middle-income countries require a societal perspective where Egypt, Colombia, and Mexico recommend the perspective cover the entire healthcare system and Cuba and Malaysia recommend a patient perspective.

The PGSA limit the inclusion of costs relevant to the third-party payer perspective, i.e. private health insurance companies and “… indirect costs should not be included in the submission”Citation8 (p. 32). Any resource use should be based on South African practice or adjusted to the South African setting if based on international practice. Most high-income countries (Portugal, Taiwan, The Netherlands, and Ireland) require that direct and indirect costs be separately listed, while Germany considers indirect costs where the health technology has a substantial impact on productivity and in Norway productivity gains and costs due to the treatment effect are not compulsory. Colombia permits only the inclusion of direct medical costs and excludes “… changes in productivity or costs or benefits in other sectors of society”Citation12 (p. 15). All other middle-income countries (Mexico, Brazil, Egypt, Cuba, and Malaysia) recommend the inclusion of direct and indirect medical costs if appropriate for the study perspectiveCitation12–17.

Modeling

The PGSA require that the economic submission be “… based on the natural course of the condition …”Citation8 (p. 30), and it discourages the use of complex models. If a model is used in a pharmacoeconomic evaluation, an application must be lodged with the Department of Health prior to its development with a justification for the use of the model, type of model, description of model design including schematic diagrams, main clinical outcome to be modeled, time horizon for the model, and how the model intends to handle uncertainty. The Department of Health may either approve or reject the use of the model. International models that have been adapted with local input variables may be accepted provided the application is clearly stated and justified.

All high-income countries permit the use of pharmacoeconomic modeling and emphasize that assumptions and data sources be clearly documented or that the internal and external validity of the model be carefully evaluated. For example, The Netherlands requires transparent and simple models that include the most important processes and Portugal recommends a standard model for presenting an economic evaluation, but that authors should not be limited to any particular techniqueCitation18,Citation19. Similarly, middle-income countries permit the use of pharmacoeconomic modeling. For instance, researchers in Brazil have the flexibility to develop a model consistent with the primary research question, Mexico and Egypt requires a description of how the model was validated (structure, data, and assumptions), and a mathematical decision model in Colombia must include a description and justification of the model structure, assumptions, and sources of information of the parametersCitation12–14,Citation16.

Equity issues stated

The PGSA do not explicitly discuss equity issues, unlike some middle and high-income countries where Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) across different population characteristics should be valued equallyCitation12,Citation16,Citation20. Taiwan requires that implicit and explicit equity assumptions in resource allocation decisions be clearly stated, for example the effect of an intervention must be valued equally across the population regardless of gender, age, or socioeconomic statusCitation21. Germany highlights that the methodological and equity issues be evaluated when transferring QALYs across therapeutic areas or different contexts, and Norway requires that the “distribution profile of the reimbursement decision”Citation22 (p. 14) be specified as it relates to allocating health effects and costs across different groups in society. The pharmacoeconomic guidelines in Portugal, Malaysia, and Mexico do not explicitly discuss equity issues.

Financial impact analysis

The PGSA does not detail the need for a financial impact analysis (aka budget impact analysis), unlike most middle-income countries (Brazil, Cuba, Malaysia, and Mexico) where it is required, and in Egypt and Colombia where it is recommended. All high-income countries require or recommend the inclusion of a budget impact analysis. For instance, in Germany a budget impact analysis is mandatory to determine whether the new health technology is “… affordable to German insurants”Citation23 (p. 42), and in Portugal an estimated impact of the new health technology on the public medicine budget must be included. In Brazil, pharmacoeconomic submissions require an estimation of the short- and medium-term impact of the new health technology to determine whether sufficient resources are available, and in Cuba the conclusions of the pharmacoeconomic evaluation should refer to the economic impact of the results, and in Malaysia the budget impact analysis must take the perspective of the healthcare provider or funder to address the “… issue of affordability and sustainability”Citation17 (p. 6).

Mandatory, recommended, or voluntary submissions

Most high-income countries (Germany, Norway, Portugal, and The Netherlands) require a mandatory health economic evaluation be performed consistent with international standards on pharmacoeconomics. For instance, in Germany a pharmacoeconomic evaluation supports the GKV-Spitzenverband (National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds) determine the maximum reimbursable price of medications (Germany PE guidelines), and in The Netherlands the results of a pharmacoeconomic evaluation are linked to reimbursement decisions and listing under the Pharmaceutical Reimbursement System (GVS)Citation18,Citation23. In contrast, no middle-income country proscribes mandatory pharmacoeconomic submissions except Mexico. All submissions are recommended in the sense that guidelines are not linked to regulatory or reimbursement decisions by public agencies, but rather serve as “… recommendations and not directives”Citation15 (p. 7) to guide the standardization of pharmacoeconomic methods. In Malaysia, pharmacoeconomic submissions remain voluntary, despite plans to introduce mandatory submissions 2 years after launch of the guidelines in March 2012. Similarly, the PGSA outline a voluntary process of pharmacoeconomic submissions until such time as the Director-General of the Department of Health decides otherwise. Among middle-income countries, only Mexico details a mandatory process of submitting new health technologies for listing on Cuadro Básico de Insumos del Sector Salud (CBISS – a list of basic inputs used in the healthcare sector).

Discussion

Study perspective and costs

South Africa is the only country that limits the scope of the pharmacoeconomic guidelines to the private healthcare sector and a third-party payer perspective (i.e. private health insurance companies). Private healthcare expenditure in South Africa is 4.6% of GDP and an estimated 16.8 billion USD ()—approximately half the private healthcare expenditure in Mexico and a seventh of Brazil’s expenditureCitation24. Comparatively larger private healthcare expenditure in both middle-income countries may have motivated pharmacoeconomic guidelines focused on the private sector; however, Brazil and Mexico recommend pharmacoeconomic evaluations from a societal perspective that cover the whole healthcare system. The private healthcare expenditure as a proportion of GDP in South Africa is the highest among middle and high-income countries, surpassed only by Brazil. Relative and absolute measures of private healthcare expenditure are important to consider in the design and implementation of pharmacoeconomic guidelines.

Table 2. Private health expenditure by country as a percentage of GDP and at market prices.

A narrow focus on the private sector and a third-party payer may limit the usefulness of pharmacoeconomic evaluations intended to contain medicine expenditure and regulate medicine reimbursement prices. For example, a cost utility analysis may suggest a medicine is reimbursable in the private sector, but it does not address whether patients in the public sector have access to the same medicine, that is questions on the equitable distribution of cost-effective health technologies in South African society (discussed further below). Moreover, “there is a broad consensus, both nationally and internationally, that on the grounds of welfare theory the societal perspective should form the basis for pharmacoeconomic evaluation”Citation18 (p. 3). A limited perspective narrowly focused on the private sector may have unintended consequences on medicine prices in the public sector in South Africa (and vice versa) and also have spillover effects for medicine prices in neighboring Sub-Saharan African countries. The consequences of the PGSA are subject to further research, and no evidence is yet available on the effects, given the voluntary nature of the guidelines.

On the other hand, a medicine that results in significant productivity gains and improved quality-of-life (e.g. biologics for rheumatoid arthritis and some cancers) will not be fully valued by private health insurance companies. It’s likely that under such circumstances a medicine will be found “… unreasonably priced”Citation8 (p. 7) when evaluated by the Department of Health. The PGSA do not offer criteria on how that determination is made. To this end, the PGSA should include a societal perspective and articulate with public decisions on resource allocation and efficiency in the healthcare sector. The exclusion of indirect costs under the third-party payer perspective will significantly limit the usefulness of pharmacoeconomic evaluations and lead to pharmaceutical policies that do not maximize the efficiency and societal benefit of new health technologies. To this end, “adopting a societal perspective that captures all relevant costs and consequences of the technologies in question, regardless on whom these costs and consequences fall, is considered the most comprehensive approach that can be taken”Citation20 (p. 19). However, the societal perspective may be limited comparable to the approach in other middle and high-income countries.

Modeling

No other country requires the submission of an application to develop a model prior to the development and submission of a pharmacoeconomic evaluation. The results of a pharmacoeconomic evaluation depend on the structure and assumptions of the proposed model, so a pre-approved model may help validate its appropriateness prior to a full submission. However, this approach is most likely linked to the PGSA “… discouraging the use of complex models where a simple model will adequately support the economic argument”Citation8 (p. 32).

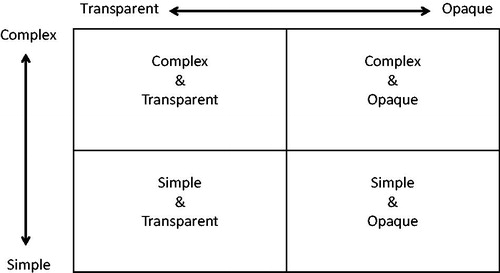

The PGSA appear to conflate complexity and transparency and may erroneously use these terms interchangeably. Complexity refers to how accurately a model represents a clinical practice setting and transparency enables the replication of research and study findings—an essential feature of the scientific process. Ideally, policy on pharmacoeconomic submissions should encourage models that accurately represent reality and are replicable, that is models that are complex and transparent (). Complex or simple models that are opaque should be discouraged, particularly those with inadequate documentation on data sources, identification and selection of variables, or ambiguous assumptions. However, the PGSA appear to favour simple over complex models, assuming that full transparency is maintained.

The PGSA disincentivize the use of complex models in the sense that pharmacoeconomic researchers may be encouraged to forgo critical details in developing a model. For example, cancer patients move through different phases in their journey, including a treatment phase, remission phase, relapse phase, among others, all of which are integral in the natural course of cancer. It’s uncertain how a model other than a Markov model will adequately represent the nature of cancer. Markov models also range from simple to complex; however, the PGSA prefer a simple Markov model. Rather than over-simplifying reality, researchers should be incentivized to develop models that accurately represent the reality of local practice conditions. Furthermore, it may be more efficient to fully evaluate a complex and transparent model by interrogating the structure, variables and assumptions than it is to evaluate an over-simplified model and the absence of unknown factors.

A preference for simple above complex models may be exacerbated by recent findings that half of the articles on health economics in South Africa are poor quality and statistically related to country of residence of the author, poorer in South Africa compared to international authorsCitation25. The results suggest that authors of pharmacoeconomic studies located in South Africa are insufficiently equipped or lack the research rigor to produce quality pharmacoeconomic studies. Further work is needed in building the capacity of analysts conducting pharmacoeconomic research and evaluators of pharmacoeconomic submissions.

Equity issues stated

The PGSA do not discuss equity issues unlike other guidelines that highlight QALYs should be equally valued across the population or that they should be judiciously transferred across therapeutic areas. Future versions of the PGSA would be improved with a discussion on these topics; however, the narrow focus of the Pricing Committee and the PGSA on the private healthcare sector may perpetuate inequities in South Africa’s dual healthcare system. In 2012, the Department of Health started phasing-in National Health Insurance to “… promote equity and efficiency to ensure that all South Africans have access to affordable, quality healthcare services …”Citation26. The objective is to establish a single risk pool to procure services for the whole population, irrespective of employment statusCitation27. To promote equity and social solidarity will require a societal perspective grounded in welfare economics that assesses value judgments on new health technologies in designing reimbursement policies. To this end, the narrow focus of the PGSA on only the private healthcare sector and a third-party payer perspective is in conflict with the broader equity objectives stated above, despite both policies on the NHI and the PGSA originating from the same policymaker, the Department of Health. For example, as discussed earlier, a cost-effectiveness analysis for a new medicine that recommends reimbursement in the private healthcare sector does not answer whether it is cost-effective in the public sector and reimbursable under the anticipated introduction of the NHI. As a result, the reimbursement of a new medicine may be an efficient allocation of resources in the private healthcare sector, but it does not address access to the new medicine for the South African society as a whole.

Financial impact analysis

Private health insurance companies in South Africa are not required by regulation to publish reimbursement data (aka claims data), aggregated or disaggregated without patient identifiers. Reimbursement data contain ICD-10 codes to identify a study population, and actual costs reimbursed for medicines, hospitalizations, diagnostic and laboratory tests, medical visits, and nursing care, among others. Private health insurance companies are either self-managed or managed by contracted private third-parties and data on reimbursed costs are integral in maintaining a sustainable and competitive business. These companies are unwilling to disclose reimbursement data, which voids the possibility of performing a financial impact analysis in South Africa. This may explain the absence of any details on a financial impact analysis in the PGSA, unlike other countries where it is either required or recommended.

Mandatory, recommended, or voluntary submissions

Despite the availability of pharmacoeconomic guidelines in all countries, middle-income countries only recommend or encourage voluntary submissions, unlike high-income countries where pharmacoeconomic submissions are mandatory. The availability of pharmacoeconomic guidelines enables the process of assessing a new health technology and its value to society. Identifying factors that are absent in middle-income countries but present in high-income countries may determine whether calling for mandatory submissions is a viable objective in South Africa or other middle-income countries. For example, the lack of adequately trained staff at the Department of Health in South Africa and the narrow focus of the Pricing Committee on the private sector may be factors that inhibit the implementation of mandatory pharmacoeconomic submissions. The lack of financial resources may also prevent the Department of Health from evaluating pharmacoeconomic submissions and providing timely assessment reports.

Although voluntary submissions are encouraged in South Africa, an uncertain appeals process may discourage submissions by pharmaceutical companies. The PGSA note that “… the findings of the assessment are not binding and no provision has been made for the appeals process in this version of the guidelines”Citation8 (p .13). Although the assessment is not binding, pharmaceutical companies may still be concerned with the implications of a decision, albeit voluntary at this stage. A transparent and detailed appeal process may facilitate the voluntary submission of pharmacoeconomic evaluations. Further research is needed to determine whether this factor, adequate training, financial resources, or others in middle-income countries facilitate the implementation of mandatory pharmacoeconomic submissions.

Conclusion

This comparative review set out to present how the PGSA compare with those in other middle- and high-income countries. The review identified key features of the PGSA comparable with other guidelines, and incomparable key features were identified and discussed. Overall, the PGSA are comparable to other countries, but differ in important areas: study perspective and allowable costs, approaches to modeling, mainstreaming equity, conducting budget impact analysis, and implementing mandatory submissions.

This analysis was limited to the consideration of pharmacoeconomic guidelines in countries with different healthcare systems, health financing mechanisms, and differing roles of the private healthcare sector. A description of the context of each country-level pharmacoeconomic guideline was beyond the scope of this analysis. Although contextual differences between countries may exist, the study perspective in pharmacoeconomic guidelines across all countries is consistent in its preference for a societal perspective.

The analysis included a random sample of six high-income countries to match the only six low- and middle-income countries available for analysis. The method design sought to balance the sample of countries across the World Bank income classification to compare with South Africa. A purposive sample with an inclusion criteria based on comparable healthcare structure with South Africa may have resulted in a limited sample and introduced unnecessary bias. A random sample of high-income countries was, therefore, used to reduce undesirable features of purposive samples—arbitrariness, bias, and subjectivity. Furthermore, if there were any emerging economies comparable to South Africa and with large private sectors, they would have been included because guidelines in all low- and middle-income countries were analysed, and the size of their private sectors compared in . Further research is needed to confirm these results. Establishing “… whether a medicine represents fair value for money” may not be immediately achievable in South Africa. To this end, future work on the PGSA may focus on: (i) adopting a societal perspective with limitations, (ii) incentivizing complex and transparent models, (iii) integrating equity issues, (iv) addressing conflicting policy objectives between the PGSA and the NHI, (v) incentivizing health insurance companies to disclose reimbursement data, and (vi) require the inclusion of a budget impact analysis in all pharmacoeconomic submissions. Finally, further research is needed on factors that facilitate the implementation of mandatory pharmacoeconomic submissions.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The author declares receiving no funding to prepare this article.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The author works at Carapinha & Company, a specialist market access firm focused on emerging pharmaceutical markets. The author is an Editorial Board member of the Journal of Medical Economics. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Notes

1 United States Dollars (USD), at an exchange of 14.44 USD to ZAR on 26 July 2016. That is, R200,000 and R400,000 oncology benefits per year.

References

- Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates. Statistical release P0302 [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 3] Available from: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022013.pdf

- Department of Health, South Africa. Regulations relating to a transparent pricing system for medicines and scheduled substances. Government Notice R1102 in Government Gazette 28214 26304. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2005

- Council for Medical Schemes. Annual Report 2014/2015 [Internet]. [cited 2016 Jul 26] Available from: http://www.medicalschemes.com/files/Annual%20Reports/AR2014_2015.pdf

- Council for Medical Schemes. Prescribed Minimum Benefits Definition [Internet]. [cited 2016 Jul 26] Available from: http://www.medicalschemes.com/medical%5Fschemes%5Fpmb/index.htm

- Discovery Health Medical Scheme. Oncology Programme. 2016. [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 4] Available from: https://www.discovery.co.za/discovery_coza/web/linked_content/pdfs/health/benefit_information/oncology_programme.pdf

- Carapinha JL. Policy Guidelines for Risk-Sharing Agreements in South Africa. South Afr. Fam. Pract. 2008;50(5):43–46

- Carapinha JL. Setting the Stage for Risk-Sharing Agreements: International Experiences and Outcomes-based Reimbursement. South Afr. Fam. Pract. 2008;50(4):62–65

- Department of Health. Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Submissions. [Internet]. South Afr. Med. Price Regist. [cited 2016 Feb 1] Available from: http://mpr.gov.za/PublishedDocuments.aspx.

- International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. Comparative Table of Pharmacoeconomic Guidelines Around The World [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 1] Available from: http://www.ispor.org/PEguidelines/COMP3.asp

- Eldessouki R, Dix Smith M. Health Care System Information Sharing: A Step Toward Better Health Globally. Value Health Reg. Issues. 2012;1(1):118–120

- International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. Pharmacoeconomic Guidelines Around The World [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 1] Available from: http://www.ispor.org/PEguidelines/index.asp

- Instituto de Evaluacion Tecnologica en Salud. Manual para la elaboracion de evaluaciones economicas en salud. Colombia. [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 6] Available from: http://www.iets.org.co/Manuales/Manuales/Manual%20evaluacio%CC%81n%20econo%CC%81mica%20web%2030%20sep.pdf

- Consejo de Salubridad General, Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica. Guía para la conducción de estudios de evaluación económica para la actualización del Cuadro Básico de Insumos del Sector Salud en México. Distrito Federal; Mexico; 2008

- Ministerio da Saude. Estudoes de Avaliacao Economica de Tecnologias em Saude. Brasil. [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 6] Available from: http://www.ispor.org/peguidelines/source/Economic-Evaluation-Guidelines-in-Brazil-Final-Version-2009.pdf

- Ministerio de Salud Publica. Guia Metodologica para la Evaluacion Economica en Salud. Cuba. 2003

- Minister of Health and Population. Guidelines for Reporting Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations. Egypt. 2013

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. Pharmacoeconomic Guideline for Malaysia. Putrajaya; 2012

- College voor zorgverzekeringen. Guidelines for pharmacoeconomic research, updated version. The Netherlands. [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 4] Available from: http://www.ispor.org/peguidelines/source/HTAGuidelinesNLupdated2006.pdf

- Infarmed. Guidelines for Economic Drug Evaluation Studies. Portugal. [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 4] Available from: http://www.ispor.org/peguidelines/source/PE%20guidelines%20in%20English_Portugal.pdf

- Health Information and Quality Authority. Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies in Ireland. [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 5] Available from: http://www.ispor.org/peguidelines/source/Ireland_Economic_Guidelines_2010.pdf

- Taiwan Society for Pharmacoeconomic and Outcomes Research. Guidelines of Methodological Standards for Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations [Internet]. Available from: http://www.taspor.org.tw/

- Norwegian Medicines Agency. Guidelines on how to conduct pharmacoeconomic analyses. Norway. [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 4] Available from: http://www.ispor.org/peguidelines/source/Norwegian_guidelines2012.pdf

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. General Methods for the Assessment of the Relation of Benefits to Costs. Germany [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 5] Available from: http://www.ispor.org/peguidelines/source/Germany_AssessmentoftheRelationofBenefitstoCosts_En.pdf

- World Bank. GDP at market prices (current US$) [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 9] Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD

- Gavaza P, Rascati KL, Oladapo AO, Khoza S. The state of health economic research in South Africa: a systematic review. PharmacoEconomics. 2012;30(10):925–940.

- SAInfo. Health care in South Africa [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 3] Available from: http://www.southafrica.info/about/health/health.htm#.VrI-T-aOLm5

- Matsoso MP, Fryatt R. National Health Insurance: The first 18 months. S. Afr. Med. J. [Internet]. [cited 2016 Feb 16] [about 4 screens] Available from: http://hmpg.co.za/index.php/samj/article/view/3413