Abstract

Aim: To assess the cost-effectiveness of first-line pemetrexed/platinum and other commonly administered regimens in a representative US elderly population with advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Materials and methods: This study utilized the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer registry linked to Medicare claims records. The study population included all SEER-Medicare patients diagnosed in 2008–2009 with advanced non-squamous NSCLC (stages IIIB–IV) as their only primary cancer and who started chemotherapy within 90 days of diagnosis. The study evaluated the four most commonly observed first-line regimens: paclitaxel/carboplatin, platinum monotherapy, pemetrexed/platinum, and paclitaxel/carboplatin/bevacizumab. Overall survival and total healthcare cost comparisons as well as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated for pemetrexed/platinum vs each of the other three. Unstratified analyses and analyses stratified by initial disease stage were conducted.

Results: The final study population consisted of 2,461 patients. Greater administrative censorship of pemetrexed recipients at the end of the study period disproportionately reduced the observed mean survival for pemetrexed/platinum recipients. The disease stage-stratified ICER analysis found that the pemetrexed/platinum incurred total Medicare costs of $536,424 and $283,560 per observed additional year of life relative to platinum monotherapy and paclitaxel/carboplatin, respectively. The pemetrexed/platinum vs triplet comparator analysis indicated that pemetrexed/platinum was associated with considerably lower total Medicare costs, with no appreciable survival difference.

Limitations: Limitations included differential censorship of the study regimen recipients and differential administration of radiotherapy.

Conclusions: Pemetrexed/platinum yielded either improved survival at increased cost or similar survival at reduced cost relative to comparator regimens in the treatment of advanced non-squamous NSCLC. Limitations in the study methodology suggest that the observed pemetrexed survival benefit was likely conservative.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer among both men and women in the US, and it is the leading cause of cancer death in both gendersCitation1. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for ∼84% of all lung cancer cases in the USCitation1. In patients with advanced (Stage IIIB/IV) NSCLC, a platinum-based doublet (including cisplatin or carboplatin in combination with pemetrexed, paclitaxel, docetaxel, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, irinotecan, etoposide, or vinblastine) is considered effective first-line chemotherapy for metastatic NSCLCCitation2.

Past clinical trials have documented the emergence of specific doublet and triplet regimens that promise improved clinical outcomes for non-squamous NSCLC patients. In 2006, a phase III trial reported that adding bevacizumab to paclitaxel plus carboplatin had a significant survival benefit in patients with recurrent or advanced non-squamous NSCLC. Although the study population was selected to be of low hemorrhagic risk, the safety results included a significant excess of grade 3–5 bleeding events, neutropenia, and other toxicities among the bevacizumab recipientsCitation3.

Subsequently, a pre-specified sub-set analysis of a phase III clinical trial comparing pemetrexed plus cisplatin to gemcitabine plus cisplatin reported statistically superior overall survival (OS) for pemetrexed/cisplatin in patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLCCitation4,Citation5. In this large sub-set of patients as well as in the overall NSCLC population, pemetrexed/cisplatin was associated with significantly lower rates of Grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities compared to gemcitabine/cisplatin and also led to significantly lower use of medical resources including transfusions and erythropoietic or granulocyte colony-stimulating factorsCitation5,Citation6.

To date, real-world comparative data that include first-line NSCLC treatment options currently in common use are lacking, especially for the population aged 65 and older. That population constitutes almost 70% of lung cancer diagnosesCitation7. Treatment of elderly adults is complicated by their elevated frequency of comorbidities and concurrent medications. The paucity of information concerning their treatment results led the Institute of MedicineCitation8 to call for expanded cancer research in this age group.

Several recently published real-world studies of advanced NSCLC have utilized the US National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer registry linked to Medicare claims recordsCitation9–12. Three of these included some comparison of the survival time and healthcare utilization associated with various chemotherapy regimensCitation9,Citation10,Citation12. Two suggested that, when treating advanced NSCLC, patients 65–74 years old respond better in terms of overall survival than do older patientsCitation10,Citation11. Another two recent studies drew their data from patients’ regular clinical visitsCitation13,Citation14. The studies were sufficiently current to analyze pemetrexed results after that agent’s first-line approval for non-squamous NSCLC.

Several factors are worth considering when comparing treatment outcomes. Although overall survival is often viewed as the most important attribute when assessing a treatment regimen, the American Society for Clinical Oncology has long recognized improvement in cost-effectiveness as an additional factor in developing guidelines for drug useCitation15,Citation16.

In order to provide such information, we undertook the present study using Medicare claims records to assess the cost-effectiveness of the newest first-line treatment, pemetrexed/platinum, vs other commonly administered regimens in a representative US elderly population with advanced non-squamous NSCLC.

Methods

The primary goal of this study was to assess the cost-effectiveness of the four most common first-line chemotherapy regimens in a cohort of non-squamous NSCLC Medicare patients (age ≥65 years). In the process of attaining this goal, the study met a number of secondary goals, including: (a) determining the regimens frequently used to treat this cohort of patients; (b) describing the demographic/clinical characteristics of patients by study regimen; (c) determining overall survival by study regimen; and (d) analyzing the allocation of total treatment costs—with costs broken down by service category—that were associated with each study regimen.

Data source

The data source for this study is the SEER-Medicare dataset. This linked database provides a unique resource for studying cancer outcomes in the elderly because it includes clinical data describing cancer status at diagnosis along with a complete administrative record of health services and costs for SEER registrants who are Medicare beneficiaries. The 17 SEER collection areas cover an estimated 28% of the US population.

At the time the study was initiated, SEER-Medicare had completed its 2012 biannual update. That update included incident cancer cases in 2008–2009, with incident and prevalent cases linked to Medicare data through 2010. These newly-added records were the basis for the present study.

The SEER-Medicare update was critical for this study because the FDA approved pemetrexed/cisplatin for first-line advanced non-squamous NSCLC treatment in September 2008Citation17. Before that, pemetrexed’s FDA approval covered treatment of advanced NSCLC only as single-agent second-line therapy of lung cancer and mesothelioma.

The SEER-Medicare linked database is subject to a number of limitations. First, there are no claims data for Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in a managed care plan (“Medicare Advantage”). Our study, therefore, included only beneficiaries enrolled in the traditional Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) program. In 2009, 77% of the Medicare population participated in the FFS program.

Both utilization and costs for physician-administered drugs are recorded in the Part B claims, which were included in this study. Part B-covered drugs include the oral equivalents of injectable and intravenous chemotherapies and anti-emetics as well as these agents’ parenteral formulations. Medicare covers self-administered oral drug therapies through Part D, which was initiated in 2006. Prescriptions for oral chemotherapy agents and oral drugs for managing comorbidities and toxicities appear in the Part D records, but their costs are not available and could not be investigated by this study.

The SEER-Medicare records lack direct performance status data. To compensate for this gap, we assessed the study population on the basis of the NCI Combined Comorbidity Index, an adaptation of the Charlson Index that includes lung cancer-specific survival weighting for the Charlson-identified non-cancer comorbidities observed in claims recordsCitation18. The NCI Combined Comorbidity Index is a better mortality predictor than Charlson in elderly patientsCitation18 and has been favored by a previous group conducting comparative effectiveness studies of NSCLC chemotherapy in SEER-Medicare dataCitation19,Citation20.

Population

The initial study population included all SEER-Medicare listed patients diagnosed in 2008 or 2009 with advanced non-squamous NSCLC (stages IIIB–IV) as their first and only primary cancer diagnosis. The final study population included only those patients initially treated within 90 days with the study-selected treatment regimens. The most commonly used first-line chemotherapy regimens among advanced NSCLC patients were determined from a treatment pattern analysis. That analysis supported the selection of a study population that received pemetrexed/platinum, either of two generic platinum-containing regimens (paclitaxel/carboplatin or platinum monotherapy), or the triplet regimen paclitaxel/carboplatin/bevacizumab.

Survival analysis

Treatment effect, quantified as mean time to death after initiation of first-line therapy, was estimated using the area under the Kaplan-Meier curve. Patients who survived until the end of the observation period (December 31, 2010) were administratively censored at the post-index month that they had reached on this date. Thus, the Kaplan-Meier curve itself was truncated conservatively at the last observed death within the treatment cohort in each stratum, the anticipation being that sufficiently long follow-up would be available in the dataset to adequately describe the full survival curve. To check on possible bias introduced by restrictions, an exploratory analysis utilized an exponential trend line that extended the tails of the Kaplan-Meier curves forward from the last observed death.

Care costs

We considered total Medicare payments as representative of overall costs. In addition, we broke down total Medicare payments by service category so as to describe cost drivers.

Administrative censoring at the end of the observation period creates a potential bias because the extended costs of longer survivors and recently diagnosed patients could not be determined. To adjust for censoring, we invoked the Kaplan-Meier Survival Adjustment (KMSA) method described by Lin et al.Citation21. This method weights the average costs incurred during each month since the start of treatment by the probability that patients will survive until the start of that same month.

Stratification by disease stage

Stage of disease, IIIB (regional metastasis) or stage IV (distant metastasis), is known to be a significant prognostic factor for lung cancer patientsCitation4. To mitigate the potential impacts of imbalances in the distributions of patients treated with the various regimens across these strata, an approach was taken to determine the average treatment effect (ATE) for cost and survival. The mean difference between pemetrexed/platinum and each of the comparators was determined within each stratum. The strata were then combined with weights proportional to the size of strata, that is, the total number of patients in the stratum treated with either pemetrexed/platinum or comparator.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER)

To evaluate cost-effectiveness, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was employed. Pemetrexed/platinum was used as the basis for the ICER comparisons because it was the most recently approved of the commonly used regimens found in the study population. The ICER represents the difference in mean total Medicare costs recorded with pemetrexed/platinum and one of the comparator regimens divided by the mean survival difference in life-years between the two regimens. The ICER analysis was performed in both the unstratified and stage-stratified study population. To assess possible effects of stratification, the ATEs for cost and survival were used in calculation of the stage-stratified ICER.

In both the unstratified and stage-stratified populations, we determined 95% confidence intervals for each ICER through the use of 10,000 bootstrapped re-samplesCitation22. In the case of the stage-stratified re-samples, ICERs for each individual re-sample were derived from the survival and cost ATEs. An analysis of the re-sample distribution across ICER quadrants gave a more detailed account of the probability of each regimen’s cost-effectiveness relative to pemetrexed/platinum.

Bootstrapping was necessary because ICER results are non-parametric. Traditional confidence intervals can be skewed by patients with incremental survival (ICER denominator) just below and just above zero. Furthermore, traditional confidence intervals for the ICER may fail to adequately determine the quadrant of the cost-effectiveness plane in which the comparison lies. Recording the distribution of re-sample means across the cost-effectiveness quadrants provides an estimate of the true likelihood that the comparison lies in each quadrant. The 95% CI for the ICER is equivalent to the range of ICERs falling within the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles of the re-sample distribution for the slopes of the rays from the origin to the re-sample ICER estimate. This central wedge was determined as ±47.5% of the re-sample population relative to the actual observed study cohortCitation22.

Results

Description of the study population

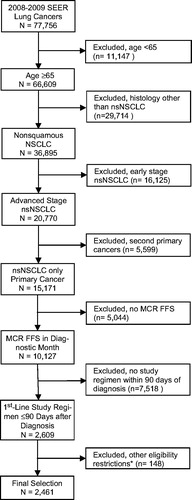

The effect of the population selection criteria is shown in . The 2008–2009 SEER registry data contained 77,756 lung cancer cases with linkage to Medicare claims records. (This population includes disabled Medicare beneficiaries aged less than 65 years.)

Figure 1. Selection of study population. *These exclusions included use of other, non-study cancer treatments as part of initial therapy (n = 82) and lack of continuous Medicare FFS eligibility from 3 months prior to diagnosis to the date of treatment initiation (n = 71). There were a total of 148 unique patients in this final category, including three with double exclusions. NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; nsNSCLC, non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer; MCR, Medicare; FFS, fee-for-service.

Of the 10,127 selected non-squamous NSCLC patients, 59% received no chemotherapy as part of initial treatment. About 94% of the treated patients received one of five agents as part of first-line therapy. We chose to study the four most frequently used first-line chemotherapy regimens in the Medicare-SEER data containing these five agents: carboplatin, other platinum (almost entirely cisplatin), paclitaxel, pemetrexed, and bevacizumab (Supplementary Table 1 and Table 1). Each of the platinum agents perform a role similar to the others in treating advanced NSCLCCitation2. Given the relatively infrequent use of platinum compounds aside from carboplatin, we created combined platinum recipient cohorts when it allowed the study to attain greater statistical power. Two of the defined study cohorts received generic regimens (platinum monotherapy and paclitaxel/carboplatin), and two received an additional proprietary compound (pemetrexed/platinum and paclitaxel/carboplatin/bevacizumab). A total of 3,096 patients received one of these regimens as first-line therapy (81% of those receiving a study agent), including the 2,609 (84%) patients who initiated these regimens within 90 days of diagnosis (). After applying our final population criteria, we were left with a total study cohort of 2,461.

In the final study population, there remained 261 patients (10.6%) who received oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) at some point after treatment initiation. During the study period, erlotinib was indicated for second-line NSCLC or maintenance therapy, and there were no TKIs approved for the first-line setting. The population receiving TKIs included 48 (12.6%) patients in the first-line pemetrexed/platinum cohort, 77 (11.3%) in the first-line platinum monotherapy cohort, 99 (9.3%) in the first-line carboplatin/paclitaxel cohort, and 37 (11.2%) in the first-line carboplatin/paclitaxel/bevacizumab cohort.

compares the demographic and disease characteristics for the recipients of the different study regimens. Pemetrexed/platinum recipients tended to be older, more urban, and have more advanced disease relative to the other treatment cohorts. Those starting therapy with the triplet regimen (paclitaxel/carboplatin/bevacizumab) tended to have fewer comorbidities. When comparing health costs (), the study found that the pemetrexed recipients incurred higher mean Medicare expenditures prior to diagnosis. In contrast, the patients on triplet therapy recorded lower Medicare expenditures before diagnosis than the other treatment cohorts.

Table 1. Study population characteristics.

After diagnosis of advanced NSCLC, the pemetrexed/platinum regimen was associated with the second highest observed Medicare treatment and care expenditures, both overall and on a monthly basis (). Recipients of the triplet comparator regimen incurred the highest costs. For each of the treatment groups, the main factors determining the size of total Medicare outlays were chemotherapy and other Part B-covered drugs (chemotherapy alone constituted 19–44% of total Medicare A–B payments), acute care hospitalization (17–29% of total Medicare A–B payments) and outpatient physician services (12–20% of total Medicare A–B payments).

Table 2. Mean monthly Medicare outlays per patient during follow-up (unadjusted).

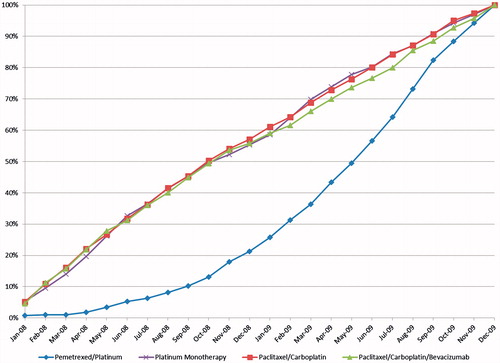

Use of pemetrexed/platinum as a first-line regimen sharply increased in 2009 compared to 2008, with 78% of pemetrexed cases occurring in 2009 compared to 43–45% for the other three regimens. The concentration of pemetrexed initiations at the end of the eligibility period is even more evident when examining the monthly proportions initiating chemotherapy (). The median month of treatment initiation was June 2009 for pemetrexed/platinum, compared to October 2008 for the other three comparison regimens. (As noted previously, the FDA in September 2008 granted full approval to pemetrexed for initial treatment of non-squamous NSCLC in combination with cisplatin.) Relative to the other treatment cohorts, this differential initiation time resulted in a shorter available follow-up period for the pemetrexed recipients () and greater administrative censorship (). A more accurate cost comparison requires that the observed results be adjusted for these differences.

Table 3. Survival and censor-adjusted total Medicare costs for study cohorts, unstratified and stratified by NSCLC stage.

Survival and censor-adjusted cost results in the unstratified population

The unstratified analysis found that the pemetrexed/platinum recipients had a statistically significant mean survival advantage over those receiving paclitaxel/carboplatin (+1.32 months, p = .003) and a trend toward increased mean survival compared to recipients of platinum monotherapy (+0.71 months, p = .06) (). The difference between pemetrexed/platinum and the triplet comparator was not significant (p = .4). However, the mean survival time in each of the four treatment cohorts was under-estimated because a sizable portion of the patients had not yet died by the end of follow-up (2010), and they, therefore, were censored in the analyses. This issue affected the pemetrexed/platinum study population in particular. One-third of the pemetrexed/platinum recipients were censored, compared to ∼20% of the other study populations. That difference was even more marked in the stage IV population, which contained 69–80% of the treatment populations (32% censorship for stage IV pemetrexed/platinum recipients vs 14–20% in the other stage IV treatment cohorts).

also shows the unstratified censor-adjusted Medicare payments in the follow-up period—i.e. from the first treatment with the specified chemotherapy regimen until death or study censoring. The censorship adjustment disproportionately increased the costs associated with pemetrexed/platinum, but this regimen was still associated with the second highest total Medicare treatment and care expenditures.

The unstratified ICER results indicated that the pemetrexed/platinum regimen recipients generally experienced longer survival, but at increased total cost to Medicare compared to the generic platinum-containing recipients (). The pemetrexed/platinum ICERs were $270,684 per added year of life when compared to platinum monotherapy and $160,800 per added year of life when compared to paclitaxel/carboplatin. The calculated pemetrexed/platinum ICER relative to the triplet comparator regimen was −$151,704 per added year of life.

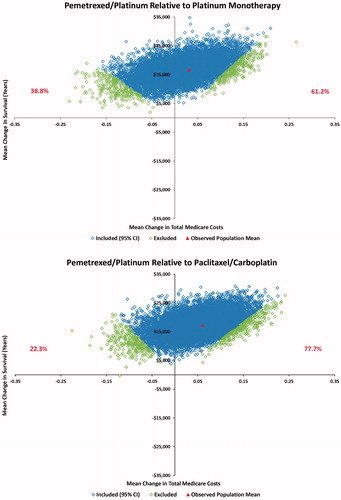

Examination of the 10,000 bootstrapped re-samples (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1) created the 95% confidence intervals for the ICERs. The pemetrexed regimen was associated with added cost and added survival in 67.0% of the re-sample comparisons with platinum monotherapy and 86.4% of the comparison with paclitaxel/carboplatin. The comparisons with the triplet regimen were more complex, with 57.4% of the re-sample comparisons associating pemetrexed/platinum with greater survival and lower cost compared to the triplet comparator and 36.2% of the re-sample comparisons associating pemetrexed/platinum with decreased survival and lower cost.

Disease stage-stratified results

The advanced NSCLC study population was broken down into those originally diagnosed with either stage IIIB or stage IV disease. Average treatment effects related to pemetrexed/platinum were calculated for both mean survival and mean Medicare expenditure ().

The stage IV cost comparisons showed that the two generic platinum-containing regimens have statistically significant economic advantages over pemetrexed/platinum (). Pemetrexed/platinum, meanwhile, had significantly better survival results in stage IV patients. The pemetrexed/platinum vs triplet comparator analysis indicated that pemetrexed/platinum was associated with considerably lower total Medicare costs in the stage IV population, with similar survival.

The disease stage-stratified ICER analysis found that the pemetrexed regimen cost $536,424 and $283,560 per additional year of life relative to platinum monotherapy and paclitaxel/carboplatin, respectively (). These values are greater than those for the simple unstratified results.

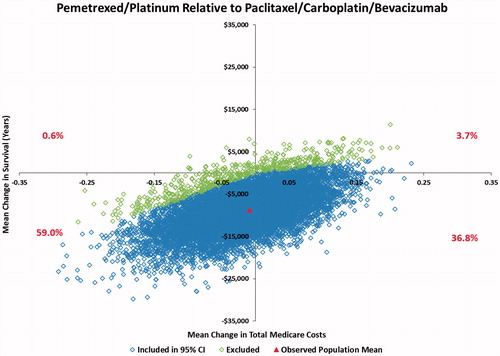

Pemetrexed/platinum was associated with added cost and increased survival in 61.2% of the re-sample comparisons with platinum monotherapy and 77.7% of the comparisons with paclitaxel/carboplatin (). The ICER comparison with the triplet regimen reversed the unstratified bootstrap results, with only 36.8% of the re-sample comparisons associating pemetrexed/platinum with greater survival and lower cost compared to the triplet regimen and 59.0% of the re-samples associating pemetrexed/platinum with decreased survival and lower cost.

Figure 3. Stage-stratified bootstrap ICER analysis* showing the proportion of re-samples with each survival/cost result. (a) Pemetrexed/platinum relative to platinum monotherapy; (b) Pemetrexed/platinum relative to carboplatin/paclitaxel; (c) Pemetrexed/platinum relative to paclitaxel/carboplatin/bevacizumab. *Slope from origin to each point = Incremental Cost-effectiveness Ratio (ICER). The dots represent means of the individual re-samples. These re-sample means were weighted according to the size of the population receiving each study treatment (average treatment effect).

Exploratory extended survival estimates

To estimate the possible bias introduced by truncating the Kaplan Meier survival estimate at the last observed death in each study cohort, we undertook an exploratory analysis utilizing an exponential trend line to extend the tails of the Kaplan-Meier curves forward from the last death (Supplementary Figure 2). In the total, unstratified population the projected mean survival extension was 3.7 months for pemetrexed/platinum. The projected survival extension amounted to 1.9 months for each of the other three unstratified treatment groups. This estimation method suggests that further observation would likely increase the incremental mean survival benefit of the pemetrexed/platinum regimen in the unstratified population by 1.8 months.

Discussion

This study revealed both survival and cost differences between common treatment regimens for advanced NSCLC in the elderly population aged ≥65 years, including the less responsive older group ≥75 years. Compared to generic platinum-containing single agent or doublet therapies, pemetrexed/platinum was associated with longer survival and higher monthly cost. Whether these results are cost-effective depends on the accepted threshold for the cost of life extensions, a threshold that is subject to considerable debateCitation23.

Compared to the bevacizumab triplet, pemetrexed/platinum was associated with lower monthly costs, whereas no trend to a survival advantage emerged, even in the bootstrap analyses. Differences in survival between these two patient cohorts should be considered alongside the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. Pemetrexed/platinum patients were older with more advanced disease, while patients receiving the triplet regimen tended to have fewer comorbidities. These patient differences may have had an impact on the length of survival time in the respective cohorts.

A major strength of this study is that it followed a population representative of all US elderly with non-squamous NSCLC. As a result, we report here the most comprehensive representation of costs and survival of any pemetrexed NSCLC study to date.

A comparable study utilized electronic medical records from a private multi-state oncology networkCitation14. This community-based study observed ∼50% shorter mean overall survival than did the present study for the three regimens common to both studies (pemetrexed/platinum, paclitaxel/carboplatin, and paclitaxel/carboplatin/bevacizumab). Conversely, survival differences between pemetrexed/platinum and the comparator regimens were longer than in the present study. The care costs reported in this previous study also were considerably lower than those in the present one.

Instructive differences in methodology underlie the differences in results between the two US studies. The community-based study had data available for performance status, but under-estimated total treatment costs due to lack of information on the major non-clinic cost contributors found in our study (). Such costs involve inpatient treatments, hospitalizations, or specialty care. It also observed patients for only 1 year, while in the present study, patients were observed for up to 3 years. The shorter duration of observation in the community-based study under-estimates both survival and costs.

The clinic patients in the community-based study were matched between regimens, but the results were not stratified by disease stage. As shown in , creating an average treatment effect from the stratified population reduces the observed survival difference between regimens relative to simply analyzing the unstratified treated populations. Other methodological differences between the two studies include an older, exclusively elderly population in the present study. In addition, the present study included a platinum monotherapy comparator regimen. Platinum monotherapy was observed in more than one-quarter of the patients in our study cohort.

The differences in these two studies also highlight the limitations of our study. The most important limitation in the present study is the differential censorship of the study regimen recipients (), which reduced the observed survival for pemetrexed/platinum to a greater extent than for the comparator regimens. The differential truncation of the longest survivors also caused a downward shift in the survival confidence intervals observed through bootstrapped re-sampling.

To estimate the extent of this bias, we undertook an exploratory analysis utilizing an exponential trend line to extend the tails of the Kaplan-Meier curves forward from the last observed death. Although the specific results of that analysis are a rough estimate, they illustrate the conservative nature of our analysis of observed survival. Of course, the observed care costs will also increase with longer follow-up time. Future studies with more recent data and more complete follow-up will be needed to better address the impact on the ICER of the differential follow-up observed in our study. This is particularly true for the stage IIIB comparisons, which were affected by the small number of stage IIIB patients receiving pemetrexed/platinum and the triplet comparator regimen.

Another study limitation was the differential administration of radiotherapy. We found that radiotherapy was disproportionately administered to the platinum monotherapy and paclitaxel/carboplatin treatment cohorts (42.9% and 47.1%, respectively, vs 26.3% for pemetrexed/platinum and 17.6% for paclitaxel/carboplatin/bevacizumab). Differences in disease status at diagnosis plus more subtle variations in patient characteristics likely underlie the disparity in radiotherapy administration. They may represent additional factors affecting the survival and cost variations observed in this study.

Subtle patient differences, such as the reduced comorbidity level in the triplet therapy cohort, may also more generally effect the survival and cost variations observed in the present study. Other, unknown confounders also might have contributed to the observed effectiveness and cost differences in this study.

The use of propensity score matching might have increased the reliability of the results of this study. However, three real-world evidence studies have now found a consistent survival advantage to treating with pemetrexed/platinum rather than a common comparator. Pemetrexed/platinum was associated with a longer median survival vs paclitaxel/carboplatin in the present Medicare-SEER cohort (+3 months) and the US multi-state community-based cohort (+2.6 months)Citation14. In addition, a European observational study reported that pemetrexed/platinum had a median survival advantage of +2.5 months relative to taxane/platinumCitation13. The consistency of the median survival estimates across studies, despite their various methodological differences and limitations, suggests that the pemetrexed/platinum survival advantage is real. Beyond that advantage, differences in cost-effectiveness between NSCLC therapies will be driven largely by cost differences.

Conclusion

Pemetrexed/platinum yielded either improved survival at increased cost or similar survival at reduced cost relative to comparators in the treatment of advanced non-squamous NSCLC. These findings were most evident in the sub-population diagnosed with stage IV disease. Limitations in the study methodology suggest that the observed pemetrexed survival benefit was likely conservative. Research that adds additional years of data could help refine the results by providing further information on the cost and survival evolution of patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC. Such an extended study would in particular include greater numbers of post-approval pemetrexed recipients observed over longer periods and matched by month/year of therapy.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company through a contract with JEN Associates.

Declaration of financial and other interests

DB, WJ, SW, and KW are employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. DMG, JK, and DEG are employees of JEN Associates and have no other financial relationships to declare. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental_material.docx

Download MS Word (513.9 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Jeanne Claypoole and Kay Schaney of inVentiv Health for editorial support on behalf of Eli Lilly and Company.

References

- Siegal R, Jemal A. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society, 2014

- Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Loo BW, et al. NCCN clinical practices in oncology: non-small cell lung cancer (Version 6.2015). Ft. Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2015

- Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. H. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2542-50

- Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3543-51

- Scagliotti G1, Brodowicz T, Shepherd FA, et al. Treatment-by-histology interaction analyses in three phase III trials show superiority of pemetrexed in nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:64-70

- Novello S, Pimentel FL, Douillard JY, et al. Safety and resource utilization by non-small cell lung cancer histology: results from the randomized phase III study of pemetrexed plus cisplatin versus gemcitabine plus cisplatin in chemonaïve patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1602-8

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER). SEER stat fact sheets: lung and bronchus cancer. 2014. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html. Accessed February 2, 2015

- Levit LA, Balogh EP, Nass SJ, Ganz PA, eds. Institute of Medicine (IOM). Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. 2013. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2013/Delivering-High-Quality-Cancer-Care-Charting-a-New-Course-for-a-System-in-Crisis.aspx. Accessed March 13, 2015

- Davis KL, Goyal RK, Able SL, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and costs in a US Medicare population with metastatic squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2015;87:176-85

- Langer C, Ravelo A, Hazard SJ, et al. Comparison of survival and hospitalization rates between Medicare patients with advanced NSCLC treated with bevacizumab-carboplatin-paclitaxel and carboplatin-paclitaxel: a retrospective cohort study. Lung Cancer 2014;86:350-7

- Lamont EB, Schilsky RL, He Y, et al. Generalizability of trial results to elderly Medicare patients with advanced solid tumors (Alliance 70802). J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107:336

- Owonikoko TK, Ragin C, Chen Z, et al. Real-world effectiveness of systemic agents approved for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a SEER–Medicare analysis. Oncologist 2013;18:600-10

- Moro-Sibilot D, Smit E, de Castro Carpeño J, et al. Outcomes and resource use of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients treated with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy across Europe: FRAME prospective observational study. Lung Cancer 2015;88:215-22

- Shah M, Winfree KB, Peterson P, et al. Cost effectiveness of first-line pemetrexed plus platinum compared with other regimens in the treatment of patients with nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer in the US outpatient setting. Lung Cancer 2013;82:121-7

- American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). Outcomes of cancer treatment for technology assessment and cancer treatment guidelines. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:671-9

- Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3868-74

- National Cancer Institute. FDA Approval for Pemetrexed Disodium. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2013. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/druginfo/fda-pemetrexed-disodium. Accessed December 19, 2014

- Klabunde CN, Legler JM, Warren JL, et al. A refined comorbidity measurement algorithm for claims-based studies of breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancer patients. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:584-90

- Zhu J, Sharma DB, Gray SW, et al. Carboplatin and paclitaxel with vs without bevacizumab in older patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA 2012;307:1593-601

- Zhu J, Sharma DB, Chen AB, et al. Comparative effectiveness of three platinum-doublet chemotherapy regimens in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer 2013;119:2048-60

- Lin DY, Feuer EJ, Etzioni R, et al. Estimating medical costs from incomplete follow-up data. Biometrics 1997;53:419-34

- Obenchain RL. Resampling and multiplicity in cost-effectiveness inference. J Biopharm Stat 1999;9:563-82

- Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Weinstein M. Updating cost-effectiveness–the curious resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold. N Engl J Med 2014;371:796-7