Abstract

Background: Continuous prophylaxis for patients with hemophilia B requires frequent injections that are burdensome and that may lead to suboptimal adherence and outcomes. Hence, therapies requiring less-frequent injections are needed. In the absence of head-to-head comparisons, this study compared the first extended-half-life-recombinant factor IX (rFIX) product—recombinant factor IX Fc fusion protein (rFIXFc)—with conventional rFIX products based on annualized bleed rates (ABRs) and factor consumption reported in studies of continuous prophylaxis.

Methods: This study compared ABRs and weekly factor consumption rates in clinical studies of continuous prophylaxis treatment with rFIXFc and conventional rFIX products (identified by systematic literature review) in previously-treated adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe hemophilia B. Meta-analysis was used to pool ABRs reported for conventional rFIX products for comparison. Comparisons of weekly factor consumption were based on the mean, reported or estimated from the mean dose per injection.

Results: Five conventional rFIX studies (injections 1 to >3 times/week) met the criteria for comparison with once-weekly rFIXFc reported by the B-LONG study. The pooled mean ABR for conventional rFIX was slightly higher than but comparable to rFIXFc (difference=0.71; p = 0.210). Weekly factor consumption was significantly lower with rFIXFc than in conventional rFIX studies (difference in means = 42.8–74.5 IU/kg/week [93–161%], p < 0.001).

Conclusion: Comparisons of clinical study results suggest weekly injections with rFIXFc result in similar bleeding rates and significantly lower weekly factor consumption compared with more-frequently-injected conventional rFIX products. The real-world effectiveness of rFIXFc may be higher based on results from a model of the impact of simulated differences in adherence.

Introduction

The standard of care for patients with severe hemophilia B (endogenous factor IX [FIX] < 0.01 IU/mL) is continuous FIX replacement therapy (i.e. continuous prophylaxis) in addition to episodic or on-demand treatment for acute bleeding eventsCitation1. For many patients, continuous prophylaxis may lead to substantially reduced bleeding rates with concomitant improvements in health outcomes, such as reduced pain, prevention of hemarthrosis and arthropathy, and improved mobility, compared with on-demand treatment aloneCitation2–5.

The National Hemophilia Foundation’s Medical Scientific Advisory Council (MASAC) recommends that continuous prophylaxis regimens with FIX products should keep trough FIX levels above 1% between doses, which can be achieved with 40–100 FIX units/kg 2–3 times per weekCitation6. Unfortunately, sub-optimal adherence to such regimens is common and may take a variety of forms (e.g. dose-skipping, under-dosing)Citation7–11. The consequence of poor adherence may be increased bleeding rates and poor lasting outcomes like chronic painCitation12–14. Patient-reported barriers to adherence include the significant time it takes to inject, venous access problems, and trouble planning for injections among othersCitation15,Citation16. Some patient populations may be particularly prone to sub-optimal adherence (e.g. adolescents who become self-injectors and young adults leaving their parents’ homes) because they may have trouble managing prophylaxis on their ownCitation17.

FIX products, specifically recombinant FIX (rFIX) products, with longer half-lives that extend FIX activity in plasma, may be a more convenient and effective treatment option for patients who can benefit from prophylaxis treatment. Specifically, by requiring fewer injections, extended half-life FIX products may reduce the burden of frequent injections and offer patients greater flexibility (e.g. via less frequent required venipuncture and fewer scheduled days with injections), potentially leading to improved adherence.

There is a need to understand these new treatments in the context of efficacy, injection burden, and weekly factor consumption. Unfortunately, no head-to-head comparisons of the efficacy of conventional vs extended half-life FIX are currently available. Similarly, no studies in which there is a common arm through which to do a standard indirect comparison to compare conventional vs extended half-life FIX are available either. Given the need of clinicians and other key decision-makers in the treatment of hemophilia for comparative evidence, this study applied statistical methods to conduct a non-head-to-head comparison of efficacy and weekly factor consumption of the first extended half-life FIX product—rFIX Fc fusion protein (rFIXFc) (ALPROLIX; Biogen, Cambridge, MA)—with conventional rFIX products based on published results of clinical studies of continuous prophylaxis treatment of adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe hemophilia B.

Materials and methods

We compared the efficacy (as measured by mean annualized bleed rate [ABR]) and weekly factor consumption of rFIXFc as reported in the pivotal phase III clinical trial in adolescents and adults (B-LONG study, Powell et al.Citation18,Citation19) with those reported in studies of conventional rFIX products identified by a systematic literature review.

Search strategy

Eligibility criteria for conventional rFIX comparison studies were based on comparability of study designs and patient populations with those of the Powell et al.Citation18 rFIXFc study. Specifically, we included clinical trials or post-marketing surveillance studies that evaluated continuous prophylactic treatment of previously-treated subjects with moderate-to-severe hemophilia B with an rFIX product approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency. Based on the characteristics of Powell et al.Citation18 subjects, we required eligible comparison studies to have a majority of subjects between ages 12–71 years, with moderate-to-severe hemophilia B (endogenous FIX level ≤0.02 IU/mL). Where data were reported, we also required eligible studies to include subjects with a similar number of bleeds in the 12 months prior to the study as the Powell et al.Citation18 subjects (weekly prophylaxis arm). We excluded studies that did not report the mean ABR (or data from which mean ABR could be estimated) for subjects receiving continuous prophylaxis.

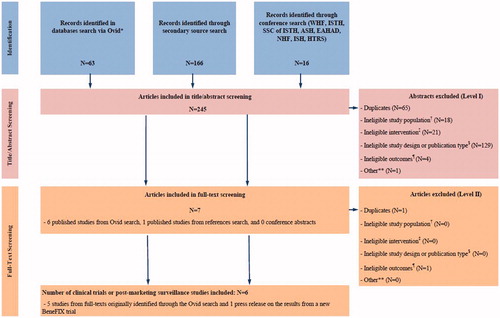

We searched relevant databases and recent hemophilia conference abstracts with no date or language restrictions. See for a complete list of search terms and databases. Results of the search strategy are depicted as a PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, diagram in Citation20.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram for systematic literature review of clinical studies of continuous prophylactic use of recombinant products among patients with moderate-to-severe hemophilia B. PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; WHF: World Hemophilia Federation; ISTH: International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis; SSC of ISTH: Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; ASH: American Society of Hematology; EAHAD: European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders; NHF: National Hemophilia Foundation; ISH: International Society of Hematology; HTRS: Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society. *Databases searched: EMBASE, MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Medline Daily, and EBM Reviews (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Methodology Register, and Health Technology Assessment). †Study population consisted of previously-treated subjects, the majority of whom were aged 12–71 years with moderate-to-severe hemophilia (endogenous factor level ≤0.02 IU/mL). Where reported, number of bleeds in 12 months prior to the study was required to be similar to that of Powell et al.Citation18 subjects (weekly prophylaxis arm). ‡Eligible interventions consisted of continuous prophylaxis use of approved recombinant products. $Study designs or publication types considered included clinical trials of any duration (including cross-over trials if data were presented at cross-over) and post-marketing surveillance studies that reported eligible interventions and outcomes for eligible study population. ¶Eligible study outcomes consisted of mean ABR or an outcome that facilitated estimation of mean ABR (e.g. monthly bleed rate). ** Studies that were not about hemophilia B, did not yet have results, or for which the ABR among prophylaxis patients could not be determined.

Table 1. Search terms.Table Footnotea

Screening and data extraction

The following data were extracted from all conventional rFIX comparison studies screened and found eligible for inclusion in our study: study design, endogenous FIX IU/mL of subjects included in the study, treatment interventions (including doses and frequency of administration), mean and median weekly factor consumption, and the ABR (mean and standard deviation [SD]) of subjects receiving continuous prophylactic treatment.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of efficacy were based on the simple differences in mean ABRs reported for rFIXFc and individual studies of conventional rFIX products. Our primary results are based on comparisons using the weekly prophylaxis arm (Arm 1) of the Powell et al.Citation18 rFIXFc study given its comparability in design to the fixed interval treatment regimens of most comparison studies identified. In Supplement 1, we report the results of sensitivity analyses involving ABR comparisons with the individualized prophylaxis arm (Arm 2) of the Powell et al.Citation18 study. Specifically, our sensitivity analyses report comparisons based on the mean ABR from Powell et al.Citation18 Arm 2, both alone and pooled together with the mean ABR from Arm 1, via meta-analysis.

The significance of the differences in mean ABRs between studies of conventional rFIX and of rFIXFc was assessed using Student’s t-tests. For conventional rFIX studies that did not report the mean ABR, the mean ABR was estimated from the reported number of subjects on prophylaxis, the number of bleeds among these subjects during the study, and the mean length of follow-up. For conventional rFIX studies that did not report the SD of the ABR, the SD was estimated by assuming the distribution of ABRs in the study was Poisson, and then multiplying the Poisson SD by an adjustment factor intended to account for possible over-dispersion of actual ABRs. The adjustment factor was based on included conventional rFIX studies that reported the SDs of ABRs.

In addition to comparisons with individual studies of conventional rFIX products, we also undertook comparisons based on the estimated mean ABR for the group of included conventional rFIX comparison studies pooled via meta-analysis of individual conventional rFIX studies. A z-test was used to assess statistical significance of the difference between the pooled mean ABR for studies of conventional rFIX and the mean ABR for rFIXFc. Given the small number of published conventional rFIX studies and limited data on subject characteristics reported in the studies, adjusted comparisons were not feasible. Heterogeneity across individual studies of conventional rFIX products included in the meta-analysis was assessed via the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chanceCitation21. We used a random effects model for the primary results given the expected variability of treatment effect across studies. Results based on the fixed effects model are reported as a sensitivity analysis in .

We also compared mean weekly factor consumption rates (IU/kg/week) during prophylaxis with rFIXFc and conventional rFIX products identified in the systematic review. For studies in which mean weekly factor consumption was not available, we estimated it from the reported mean dose per injection and prescribed number of injections per week. The statistical significance of differences in mean weekly factor consumption was assessed using Student’s t-tests. Unreported SDs of weekly factor consumption were estimated from the ratio of the SD to the mean in B-LONG.

Finally, as a sensitivity analysis, we developed a mathematical model to simulate the impact of potential differences in adherence on ABRs. The methods and results of this analysis are detailed in Supplement 2.

Results

Study design and patient characteristics for Powell et al.Citation18 study of rFIXFc

summarize key characteristics of the study design and of subjects who received continuous prophylaxis for the Powell et al.Citation18 rFIXFc study. The study included subjects aged ≥12 years with moderate-to-severe hemophilia B who were receiving prophylaxis, or had a history of ≥8 bleeds in the year prior to enrollment, with at least 100 FIX exposure days prior to the study. The vast majority of subjects (79.4%) had endogenous FIX levels ≤0.01 IU/mL.

Table 5. Comparisons of prophylaxis ABRs.

Table 2. Study characteristics.

Table 3. Baseline characteristics of subjects receiving continuous prophylactic treatment.

Among the 63 subjects in the once weekly prophylaxis treatment arm, the median age (range) was 28 (12–71) years. These subjects had an estimated median of 10.5 (0–70) bleeds in the year prior to the study, and more than half (53.2%) were on prophylaxis. These subjects underwent prophylactic treatment with rFIXFc for an average of 48.4 weeks.

Study design and patient characteristics for conventional rFIX comparison studies

The search criteria yielded 245 studies of which six studies, the Powell et al.Citation18 study of rFIXFc and five studies of conventional rFIX products, were included in our analysis (239 studies were excluded in total; no studies were excluded due to the requirement that patients have bleeding rates in the 12 months prior to the study similar to the Powell et al.Citation18 subjects). See for further details. Among the five studies of conventional rFIX, four studies of BeneFIX (Pfizer; New York, NY) were identified: Roth et al.Citation22, Lambert et al.Citation23, Valentino et al.Citation24, and Kavakli et al.Citation25 One study of RIXUBIS (Baxter; Deerfield, IL) by Windyga et al.Citation26 was identified.

summarize key characteristics of study design and of subjects who received continuous prophylaxis in the eligible conventional rFIX comparison studies. Overall study duration ranged from 26–104 weeks (). Subjects’ ages ranged from 4–61 years (). Four of the five studies included subjects with moderate-to-severe hemophilia B only (). Most studies did not report the breakdown of subjects by <0.01 IU/mL vs 0.01–0.02 IU/mL endogenous FIX activity levels at baseline (). Approximately half (51.8%) of subjects in the Windyga et al.Citation26 study had an endogenous FIX level <0.01 IU/mL. While the Roth et al.Citation22 study included some subjects with moderate disease severity (i.e. endogenous FIX activity ≤0.05 IU/mL), the vast majority (82.1%) of subjects had an endogenous FIX level <0.01 IU/mL ().

Two of the five conventional rFIX comparison studies did not report information on the pre-study treatment regimens of subjects who received continuous prophylaxis during the study. All subjects in the Valentino et al.Citation24 and Kavakli et al.Citation25 studies were receiving only on-demand treatment prior to the study and had a minimum of 12 bleeds in the year prior to the study. Most subjects (55%) in the Windyga et al.Citation26 study reported being on both on-demand only and prophylaxis treatment regimens in the 150 exposure days prior to the study, and had an average of nearly 17 bleeds in the year prior to the study ().

Prophylactic injection frequencies during the Roth et al.Citation22 and Lambert et al.Citation23 studies of BeneFIX ranged from 1 to >3 times per week, with dose and frequency of prophylactic injections determined by the study investigators. The Valentino et al.Citation24 study of BeneFIX examined two prophylaxis regimens—100 IU/kg once weekly and 50 IU/kg twice weekly. The additional BeneFIX study reported by Kavakli et al.Citation25 examined a prophylactic regimen of 100 IU/kg once weekly. The Windyga et al.Citation26 study of RIXUBIS examined a prophylaxis regimen of 50 IU/kg twice weekly ().

ABRs during prophylaxis

Mean ABRs for prophylaxis treatment with rFIXFc and conventional rFIX products are presented in . The mean (SD) ABR in the Powell et al.Citation18 study of rFIXFc was 3.07 (2.87). The mean ABR for the Roth et al.Citation22 study, and the SDs of ABRs for the Roth et al.Citation22, Lambert et al.Citation23, and Valentino et al.Citation24 studies were not reported in the publications and were estimated. The estimated SDs were adjusted for possible over-dispersion, as described above using an adjustment factor of 2.13. Mean ABRs ranged from 2.60 (Valentino et al.Citation24 study, twice weekly prophylaxis) to an estimated 5.49 (Roth et al.Citation22 study).

The I2 statistic from the meta-analysis of mean ABRs from the conventional rFIX comparison studies was 46.9% (p = 0.094). The pooled mean ABR estimate from the random effects meta-analysis of conventional rFIX comparison studies was 3.78.

Comparisons of ABRs

Results of the comparisons of ABRs (including the sensitivity analysis) are presented in . The mean ABR from the once weekly prophylaxis arm of the Powell et al.Citation18 rFIXFc study was statistically indistinguishable from all individual conventional rFIX comparison studies (differences in mean ABRs ranged from −2.42 to 0.47).

Table 4. Prophylaxis ABRs reported in included studies.

The mean ABR associated with rFIXFc once weekly was also statistically indistinguishable from the pooled mean ABR estimate for conventional rFIX products based on the meta-analysis of conventional rFIX comparison studies (difference in mean ABR=−0.71, p = 0.210). Results from sensitivity analyses involving the individualized prophylaxis arm (Arm 2) of the Powell et al.Citation18 rFIXFc study were qualitatively similar. See Supplement 1 for further details.

Weekly factor consumption during prophylaxis

Mean (SD) weekly rFIXFc consumption during once weekly prophylaxis in the Powell et al.Citation18 study was 46.3 IU/kg (11.3 IU/kg)Citation19. The mean and SD of weekly conventional rFIX consumption during prophylaxis was not directly reported for any of the conventional rFIX comparison studies. Sufficient data with which to estimate mean weekly conventional rFIX consumption were available for four out of five comparison studies. The SDs of weekly factor consumption were not reported in the Roth et al.Citation22, Lambert et al.Citation23, and Windyga et al.Citation26 studies, and were estimated as described above. Estimates of mean weekly conventional rFIX consumption used in our comparisons ranged from 89.1 IU/kg (Windyga et al.Citation26) to 120.8 IU/kg (Lambert et al.Citation23).

Comparisons of weekly factor consumption

Results of the comparisons of mean weekly factor consumption during prophylaxis are described in . Compared with mean rFIXFc consumption in the Powell et al.Citation18 study, estimated mean conventional rFIX consumption during prophylaxis was significantly higher in the Roth et al.Citation22, Lambert et al.Citation23, and Kavakli et al.Citation25 BeneFIX studies (difference=54.5 IU/kg/week [118%], 74.5 IU/kg/week [161%], 49.3 IU/kg/week [107%], respectively, p < 0.001) and the Windyga et al.Citation26 RIXUBIS study (difference=42.8 IU/kg/week [93%], p < 0.001).

Table 6. Comparisons of weekly factor consumption.

Sensitivity analysis modeling the impact of variations in adherence

The results are reported in Supplement 2.

Discussion

Our comparisons of published clinical trial results suggest that rFIXFc, a new product with an extended half-life that enables factor levels to be maintained for longer, requires less weekly factor consumption and fewer prescribed injections to achieve similar ABRs compared with conventional rFIX products. Weekly factor consumption during prophylaxis in the five studies of conventional rFIX products was about twice as high or more compared with rFIXFc consumption in the Powell et al.Citation18 study. In addition, the mean ABR based on a meta-analysis of the five studies of conventional rFIX products was statistically indistinguishable from the mean ABR of rFIXFc in the Powell et al.Citation18 study. These results demonstrate the comparative efficacy and safety of rFIXFc in a clinical trial setting, but it is important to understand how the results may change in a real world setting.

The comparisons of efficacy presented in this study are conditional on the relatively high adherence levels observed in a clinical trial. Adherence levels are lower in the real world compared with the clinical trial setting and may be expected to differ between existing products and novel products with less demanding dosing regimens (e.g. due to less frequent or less time-consuming dosing)Citation15,Citation27. Full details of this analysis are presented in Supplement 2. In brief, we used a mathematical model of the impact of adherence on the ABR to simulate the impact of improved adherence with extended half-life vs conventional rFIX products. The results indicate that improved (but still sub-optimal) real-world adherence with rFIXFc compared with conventional rFIX products may be associated with statistically significant reductions in mean ABRs. Improved real-world adherence could take the form of patients more frequently meeting the recommended number of injections per week and injecting on scheduled days. Insofar as extended half-life rFIX products facilitate such improvements by helping meet patients’ individual needs, the main results of this study may understate the real-world effectiveness of rFIXFc compared with conventional rFIX products. Future research will determine the true relationship between adherence and extended half-life FIX products and, more generally, the impact of extended half-life FIX products on hemostatic efficacy and weekly factor consumption outside of the clinical trial setting. Another important next step will be to contextualize the efficacy and weekly factor consumption of rFIXFc and conventional rFIX products, with an understanding of their costs to patients through a cost-benefit analysis.

This study has a number of limitations. First, as with all studies based on literature reviews, the results of our study may be affected by publication bias. While our systematic review was designed to limit the extent of such bias, some bias may, nevertheless, be present. Second, our analysis was limited by the fact that we only had summary measures for ABR as opposed to patient-level data. In particular, our statistical comparisons of ABR were based on t- and z-tests of mean ABR. The lack of patient-level data prevented us from fully confirming that the parametric assumptions of our statistical tests are consistent with the data; however, a sensitivity analysis confirmed that our results are not sensitive to the particular distributional assumptions inherent in the t- and z-tests. Third, while our search criteria were designed to capture conventional rFIX studies comparable to the Powell et al.Citation18 rFIXFc study and our comparison method used a random effects meta-analysis to account for between-study variance, meta-regressions and other methods of adjustment for differences between studies in design or patient characteristics were infeasible due to the small number of available comparison studies evaluated. Consequently, our comparisons should be interpreted with caution due to the presence of potential confounders (e.g. differences across comparison studies in subjects’ ages, time on study, number of target joints, and previous use of prophylaxis), which may cause this study to either over- or under-estimate ABR and weekly factor consumption with rFIXFc compared with conventional rFIX products. For instance, we were unable to adjust for differences across studies in subjects’ disease severity. Subjects with endogenous FIX activity level ≤0.05 IU/mL contributed to the pooled conventional rFIX mean ABR as well as a greater proportion of patients with activity level between 0.01–0.02 IU/mL than in the study by Powell et al.Citation18, suggesting that the true difference in mean ABRs for subjects of the same severity may be larger than our results suggest. Fourth, standard errors of mean ABRs for some studies were based on SDs of ABRs that had to be estimated due to missing data. The potential for bias arising from the imputation of these standard errors was mitigated by adjusting estimated SDs for possible over-dispersion. Fifth, the amounts of weekly factor consumption for some conventional rFIX comparator studies were estimated from the number of prescribed weekly injections. To the extent that subjects in these studies injected less frequently than prescribed, our results may over-state the extent by which weekly factor consumption with rFIXFc in the Powell et al.Citation18 study was lower than that in the conventional rFIX comparator studies. Finally, in the Roth et al.Citation22 study, the mean ABR is estimated from reported data in the study. If the true mean ABR for the study was lower than our estimate, it would not change our results that there was no statistically significant difference between the mean ABR for Roth et al.Citation22 and for Powell et al.Citation18 or between the calculated mean ABR for rFIX and the reported mean ABR for rFIXFc. In addition, the SD of weekly factor consumption in the Roth et al.Citation22, Lambert et al.Citation23, and Windyga et al.Citation26 studies were estimated based on the ratio of mean to SD in Powell et al.Citation18. In the event that these estimates of the SDs understate the true SDs, our results may overstate the significance of the difference in weekly factor consumption when comparing these studies and the Powell et al.Citation18 study.

Conclusions

Based on comparisons of clinical study results, our study results indicate that weekly injections with rFIXFc are associated with similar bleeding rates (or potentially lower bleeding rates, based on modeling of the effects of simulated differences in real-world adherence), and significantly lower weekly factor consumption compared with more frequently-injected conventional rFIX products. These results offer key decision-makers important new information on prophylaxis with rFIXFc vs conventional rFIX products in the treatment of moderate-to-severe hemophilia B in the absence of head-to-head comparisons. Future research utilizing data based on real-world treatment and costs is needed to understand the ABR and weekly factor consumption rates of extended half-life vs conventional rFIX products in the real world.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Financial support for this study was provided by Biogen and by Sobi.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

AI’s institution has received funds for research contracts with Biogen, Baxter, Novo Nordisk, and service agreements with Bayer, Baxter, Biogen, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer, including the research project reported in the current manuscript. No funds have been paid directly to AI. SK is an employee of and holds equity interest in Biogen. KJM and SL are employees of Sobi, a collaborator with Biogen in the development and commercialization of rFIXFc. KJM and SL are also shareholders of Sobi shares. NM is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has received research grants from Biogen, including one for the current study, and SY and PK were employees of Analysis Group, Inc. at the time of the study.

Supplemental_material.docx

Download MS Word (256.9 KB)References

- World Federation of Hemophilia. Types of Prophylaxis; 2014. Montréal, Québec. http://www.wfh.org/en/abd/prophylaxis/types-of-prophylaxis. Accessed August 2016

- Zappa S, McDaniel M, Marandola J, et al. Treatment trends for haemophilia A and haemophilia B in the United States: results from the 2010 practice patterns survey. Haemoph Off World Fed Hemoph 2012;18:e140-53

- Fischer K, van der Bom JG, Molho P, et al. Prophylactic versus on-demand treatment strategies for severe haemophilia: a comparison of costs and long-term outcome. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2002;8:745-52

- Fischer K, van der Bom JG, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, et al. The effects of postponing prophylactic treatment on long-term outcome in patients with severe hemophilia. Blood 2002;99:2337-41

- Zanon E, Iorio A, Rocino A, et al. Intracranial haemorrhage in the Italian population of haemophilia patients with and without inhibitors. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2012;18:39-45

- National Hemophilia Foundation. Medical and Scientific Advisory Council (MASAC) recommendation concerning prophylaxis (regular administration of clotting factor concentrate to prevent bleeding). MASAC Documents #179 and #241; 2007. New York, USA. Available from: http://www.hemophilia.org/nhFweb/MainPgs/MainnhF.aspx?menuid=57&contentid =1007. Accessed March 10, 2014

- Geraghty S, Dunkley T, Harrington C, et al. Practice patterns in haemophilia A therapy – global progress towards optimal care. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2006;12:75-81

- De Moerloose P, Urbancik W, Van Den Berg HM, et al. A survey of adherence to haemophilia therapy in six European countries: results and recommendations. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2008;14:931-8

- du Treil S, Rice J, Leissinger CA. Quantifying adherence to treatment and its relationship to quality of life in a well-characterized haemophilia population. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2007;13:493-501

- Schrijvers LH, Uitslager N, Schuurmans MJ, et al. Barriers and motivators of adherence to prophylactic treatment in haemophilia: a systematic review. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2013;19:355-61

- Duncan N, Kronenberger W, Roberson C, et al. VERITAS-Pro: a new measure of adherence to prophylactic regimens in haemophilia. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2010;16:247-55

- Collins PW, Blanchette VS, Fischer K, et al. Break-through bleeding in relation to predicted factor VIII levels in patients receiving prophylactic treatment for severe hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost 2009;7:413-20

- McLaughlin JM, Witkop ML, Lambing A, et al. Better adherence to prescribed treatment regimen is related to less chronic pain among adolescents and young adults with moderate or severe haemophilia. Haemophilia 2014;20:506-12. doi: 10.1111/hae.12360. Epub 2014 Feb 11

- Krishnan S, Vietri J, Furlan R, et al. Adherence to prophylaxis is associated with better outcomes in moderate and severe haemophilia: results of a patient survey. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2015;21:64-70

- Hacker MR, Geraghty S, Manco-Johnson M. Barriers to compliance with prophylaxis therapy in haemophilia. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2001;7:392-6

- Schrijvers LH, Kars MC, Beijlevelt-van der Zande M, et al. Unravelling adherence to prophylaxis in haemophilia: a patients’ perspective. Haemophilia 2015;21:612-21. doi: 10.1111/hae.12660. Epub 2015 Apr 9.

- Duncan N, Shapiro A, Ye X, et al. Treatment patterns, health-related quality of life and adherence to prophylaxis among haemophilia A patients in the United States. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2012;18:760-5

- Powell JS, Pasi KJ, Ragni MV, et al. Phase 3 study of recombinant factor IX Fc fusion protein in hemophilia B. New Engl J Med 2013;369:2313-23

- Biogen Hemophilia Inc. Data on file. Cambridge, MA: Biogen. 2013.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006-12

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60

- Roth DA, Kessler CM, Pasi KJ, et al. Human recombinant factor IX: safety and efficacy studies in hemophilia B patients previously treated with plasma-derived factor IX concentrates. Blood 2001;98:3600-6

- Lambert T, Recht M, Valentino LA, et al. Reformulated BeneFix: efficacy and safety in previously treated patients with moderately severe to severe haemophilia B. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2007;13:233-43

- Valentino LA, Rusen L, Elezovic I, et al. Multicentre, randomized, open-label study of on-demand treatment with two prophylaxis regimens of recombinant coagulation factor IX in haemophilia B subjects. Haemophilia 2014;20:398-406. doi: 10.1111/hae.12344. Epub 2014 Jan 13

- Kavakli K, Smith L, Kuliczkowski K, et al. Once-weekly prophylactic treatment vs. on-demand treatment with nonacog alfa in patients with moderately severe to severe haemophilia B. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2016;22:381-8

- Windyga J, Lissitchkov T, Stasyshyn O, et al. Pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety of BAX326, a novel recombinant factor IX: a prospective, controlled, multicentre phase I/III study in previously treated patients with severe (FIX level <1%) or moderately severe (FIX level </=2%) haemophilia B. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2014;20:15-24

- Saini SD, Schoenfeld P, Kaulback K, et al. Effect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseases. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:e22-33

- Mickisch GH, Schwander B, Escudier B, et al. Indirect treatment comparison of bevacizumab + interferon-alpha-2a vs tyrosine kinase inhibitors in first-line metastatic renal cell carcinoma therapy. CEOR 2011;3:19-27

- Valentino LA, Mamonov V, Hellmann A, et al. A randomized comparison of two prophylaxis regimens and a paired comparison of on-demand and prophylaxis treatments in hemophilia A management. J Thromb Haemost 2012;10:359-67

- Ho S, Gue D, McIntosh K, et al. An objective method for assessing adherence to prophylaxis in adults with severe haemophilia. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph 2014;20:39-43