Abstract

Aims: To assess healthcare resource use and costs among irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with diarrhea (IBS-D) patients with and without evidence of inadequate symptom control on current prescription therapies and estimate incremental all-cause costs associated with inadequate symptom control.

Methods: IBS-D patients aged ≥18 years with ≥1 medical claim for IBS (ICD-9-CM 564.1x) and either ≥2 claims for diarrhea (ICD-9-CM 787.91, 564.5x), ≥1 claim for diarrhea plus ≥1 claim for abdominal pain (ICD-9-CM 789.0x), or ≥1 claim for diarrhea plus ≥1 pharmacy claim for a symptom-related prescription within 1 year of an IBS diagnosis were identified from the Truven Health MarketScan database. Inadequate symptom control, resource use, and costs were assessed up to 1 year following the index date. Inadequate symptom control included any of the following: (1) switch or (2) addition of new symptom-related therapy; (3) IBS-D-related inpatient or emergency room (ER) admission; (4) IBS-D-related medical procedure; (5) diagnosis of condition indicating treatment failure; or (6) use of a more aggressive prescription. Generalized linear models assessed incremental costs of inadequate symptom control.

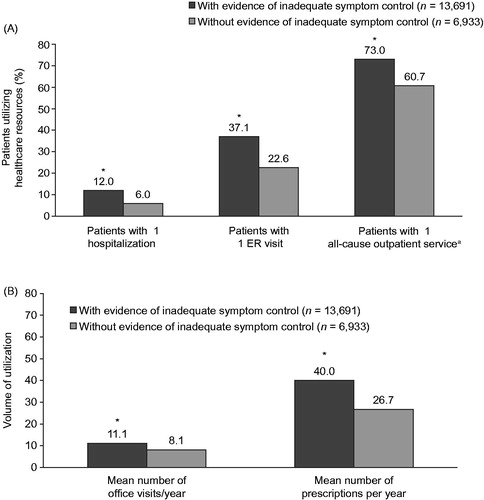

Results: Of 20,624 IBS-D patients (mean age = 48.5 years; 77.8% female), 66.4% had evidence of inadequate symptom control. Compared to those without inadequate symptom control, patients with evidence of inadequate symptom control had significantly more hospitalizations (12.0% vs 6.0%), ER visits (37.1% vs 22.6%), use of outpatient services (73.0% vs 60.7%), physician office visits (mean 11.0 vs 8.1), and prescription fills (mean 40.0 vs 26.7) annually (all p < .01). Incremental costs associated with inadequate symptom control were $3,065 (2013 US dollars), and were driven by medical service costs ($2,391; 78%).

Limitations: Study included US commercially insured patients only and inferred IBS-D status and inadequate symptom control from claims.

Conclusions: Inadequate symptom control associated with available IBS-D therapies represents a significant economic burden for both payers and IBS-D patients.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common, functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered bowel habitsCitation1. The global prevalence of IBS is ∼11%Citation2, with prevalence in the US estimated to be 10–15%Citation3. IBS is categorized clinically based on the predominant stool pattern: diarrhea (IBS-D), constipation (IBS-C), or mixed bowel patterns of constipation and diarrheaCitation4. IBS-D accounts for approximately one-third of IBS cases in the USCitation3.

IBS imposes a significant economic burden on patients and payers, similar to that seen for other chronic diseases such as hypertension and congestive heart failureCitation5. Among patients with IBS-D in the US, annual direct and indirect healthcare costs have been estimated to be $2,268 and $2,486 higher, respectively, per patient compared with controlsCitation6,Citation7. IBS-D is also associated with a significant negative impact on health-related quality-of-life and work productivityCitation7.

The management of IBS-D typically includes lifestyle/diet modifications as well as over-the-counter or prescription pharmacologic therapies. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved pharmacologic options for IBS-D include alosetron (approved only for women with severe IBS-D), as well as rifaximin and eluxadoline, which were both approved in May 2016 for adults with IBS-D. Prior to its approval, rifaximin was also utilized off-label in clinical practice to treat patients with IBS-D. Other interventions not FDA-approved for IBS-D but commonly used in clinical practice include antidiarrheal agents (e.g. loperamide) to treat associated diarrhea, and antispasmodics, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to treat associated abdominal painCitation8,Citation9. However, there is limited evidence that existing treatments effectively control the multiple chronic symptoms of IBS-DCitation10. Both the American College of Gastroenterology and the American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) provide only weak or moderate recommendations for the use of any of the aforementioned IBS-D treatments, with the exception of eluxadoline as it was not available at the time the treatment guidelines were developedCitation8,Citation10.

The inability of treatments to effectively treat and manage the symptoms of chronic disorders has been shown to result in a significant economic burden. In patients with IBS-C, research has shown that patients who experience inadequate symptom control incur higher healthcare resource use and direct costsCitation11. Specifically, among Medicaid patients with IBS-C or chronic constipation, ∼50% of patients demonstrated signs of treatment failure within a 12-month period, and this treatment failure was associated with $3,106 higher adjusted medical service costsCitation11. Among patients with IBS-D, a recent survey conducted by the AGA found that many patients switch therapies due to inadequate symptom controlCitation12.

As the symptom profile and management strategies differ for each IBS sub-typeCitation13, inadequate symptom control associated with currently available IBS-D therapies and the corresponding economic burden may provide insight into existing unmet needs and opportunities for improved patient management. The objective of this study was to examine healthcare resource use and costs among patients with IBS-D, with and without evidence of inadequate symptom control initiating a prescription medication for IBS-D, and estimate the incremental all-cause healthcare costs associated with inadequate symptom control on current IBS-D therapies.

Patients and methods

Data source

Medical, pharmacy, and eligibility claims data were extracted from the Truven Health MarketScan research database during the identification period from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2013. The database consists of inpatient and outpatient medical and surgical claims and outpatient pharmacy claims from active employees, early retirees, Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act continuees, and dependents insured by employer-sponsored plans, and includes annual data on over 50 million covered lives, reflecting a nationally representative sample of the US insured population. All data used in this study were de-identified and accessed through protocols compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 regulations. Patient confidentiality was preserved, and the anonymity of all patient data was safeguarded throughout the study. No waiver of informed consent was required from an institutional review board.

Study population and design

This study was a retrospective administrative claims database analysis of IBS-D patients in a US commercially insured population. Given the lack of an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code for IBS-D, inclusion and exclusion criteria used to identify IBS-D patients were adapted from those used in prior administrative claims research in IBS-CCitation11 and further refined in consultation with gastroenterologists on the most appropriate criteria for patient identification. Patients were classified as having IBS-D if they had ≥1 medical claim with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code in any position for IBS (ICD-9-CM 564.1x) and any of the following: (1) ≥ 2 medical claims for diarrhea (ICD-9-CM 787.91, 564.5x); (2) ≥ 1 medical claim for diarrhea and ≥1 medical claim for abdominal pain (ICD-9-CM 789.0x); or (3) ≥ 1 medical claim for diarrhea and ≥1 pharmacy claim for an IBS-D symptom-related (i.e. IBS, diarrhea, abdominal pain) prescription, including alosetron, EnteraGam, probiotics, antidiarrheals, bulk-forming agents, and anticholinergics/antispasmodics, or IBS-related claims for TCAs, SSRIs, or rifaximin. The use of eluxadoline was not captured in this analysis as it was approved after the study was conducted. Patients were also required to have had ≥1 symptom-related prescription claim within 1 year of an IBS diagnosis.

Patients aged ≥18 as of the first IBS-D symptom-related prescription or symptom-related diagnosis with continuous medical and pharmacy benefit eligibility for at least 6 months before and at least 12 months after the treatment index date were selected for analysis. The index date was defined as the date of the first IBS-D symptom-related treatment claim initiated within 1 year of an IBS diagnosis. The baseline period was defined as the 6-month period prior to the index date; the study period was defined as the 12-month period following the index date during which inadequate symptom control was assessed.

To avoid potential confounding by other GI conditions or conditions that may affect GI function, patients were excluded from the study if they had any of the following in the 6 months prior to the index date: (1) ≥ 1 medical claim for constipation, chronic gastritis, chronic pancreatitis, chronic duodenitis, or uterine fibroids; (2) ≥ 1 medical claim for constipation and ≥1 pharmacy claim for a constipation-related prescription (linaclotide, lubiprostone, stimulant laxatives, osmotic laxatives, or stool softeners); or (3) ≥ 1 medical claim for GI malignancy, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, vascular insufficiency of intestine, intestinal malabsorption, diverticulitis, diabetic neuropathy, HIV, radiation- or chemotherapy-induced colitis, microscopic colitis (lymphocytic or collagenous colitis), carcinoid syndrome, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, laxative abuse, diarrhea that is clearly drug induced, lactose intolerance, short-bowel syndrome, dumping syndrome, intestinal bypass surgery, gastric bypass/gastrectomy, collagen vascular diseases, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, cystic fibrosis, or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

Inadequate symptom control

Inadequate symptom control was defined by the presence of specific indicators while “on treatment”. The requirement of “on treatment” was defined as the period during which a patient had a supply of an IBS-D symptom-related prescription(s), plus 30 additional days thereafter to capture indicators of inadequate symptom control during the use of the originally prescribed medicationCitation11. IBS-D symptom-related prescription fills are connected using 30-day fill gap rules. Indicators of inadequate symptom control included: (1) a switch from one IBS-D symptom-related treatment to another; (2) augmentation with the addition of another IBS-D symptom-related treatment to a patient’s treatment regimen; (3) an IBS-D-related inpatient or emergency room (ER) admission while on index treatment; (4) a diagnosis of a condition indicating treatment failure while on index treatment (constipation, GI malignancy, Crohn’s disease, vascular insufficiency of intestine, celiac disease, diabetic neuropathy, uterine fibroids, microscopic colitis (lymphocytic or collagenous colitis), uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, gastric bypass/gastrectomy, collagen vascular diseases, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, ulcerative colitis, intestinal malabsorption, diverticulitis, chronic pancreatitis, chronic gastritis, chronic duodenitis, drug-induced diarrhea, lactose intolerance, short-bowel syndrome, dumping syndrome, intestinal bypass surgery, or SIBO); (5) surgery or medical procedure indicating treatment failure while on index treatment (e.g. colonoscopy, abdominal computerized tomography scan, upper endoscopy, GI motility testing, or gastric or intestinal resection); or (6) use of a more aggressive prescription while on index treatment (e.g. lomotil, tincture of opium, narcotics, or pancreatic enzymes). These criteria for inadequate symptom control were adapted from those used in a previous similar study of IBS-CCitation11 and further developed and refined in consultation with a gastroenterologist.

Study measures

Outcome measures included total annual all-cause healthcare resource utilization and total annual all-cause healthcare costs. All-cause healthcare resource utilization was defined as all medical and pharmacy claims for healthcare services associated with any condition. Medical-related claims included inpatient admissions, ER visits, physician office visits, and other outpatient services including diagnostic tests and laboratory or radiology services. Pharmacy-related claims included prescription drug use for any condition. Total all-cause healthcare costs were defined as the sum of health plan-paid and patient-paid direct healthcare costs incurred from medical and pharmacy claims associated with any condition.

Patient comorbidities were captured using the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI), a claims-based measure of overall disease burden based on the occurrence of ≥1 of more than 31 co-morbid conditions identified using the ICD-9-CM coding manualCitation14. In addition to the ECI comorbidities, 14 general and 11 GI-related comorbidities identified based on clinically relevant literature and expert clinical opinion as being common co-morbid conditions or co-morbid consequences of IBS-D () were also assessedCitation15–17.

Table 1. Demographic and health characteristicsTable Footnotea of IBS-D patients with and without evidence of inadequate symptom control (n = 20,624).

Statistical analyses

Patients with or without evidence of inadequate symptom control were stratified into two mutually exclusive cohorts. The frequency of the six indicators of inadequate symptom control was reported for those patients with evidence of inadequate symptom control. Descriptive analyses evaluated the frequency and significance of characteristics between IBS-D patients with and without evidence of inadequate symptom control, while multivariable analyses were used to assess the all-cause incremental costs associated with inadequate symptom control. For continuous variables (e.g. age), mean, standard deviation, and median were reported; frequency and percentage were reported for categorical variables (e.g. gender). Significant differences between two categorically measured covariates between the two cohorts were assessed using the Chi-square test. Differences between the two IBS-D patient cohorts and continuously measured covariates were assessed using a t-test for normal data or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for skewed data.

Generalized linear models were used to assess the incremental all-cause costs associated with inadequate symptom control after adjusting for demographics, ECI score, and 14 general and 11 GI-related comorbidities not included in the ECI score identified as potential confounders based on descriptive statistics in this study and prior researchCitation11,Citation18. The incremental costs of inadequate symptom control on the predicted all-cause medical and pharmacy costs among IBS-D patients were assessed via the method of recycled predictions. Non-parametric bootstrap estimation and t-tests were used to assess the differences in predicted costs. Differences were considered significant at the α < 0.05. Data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patient demographics and health characteristics

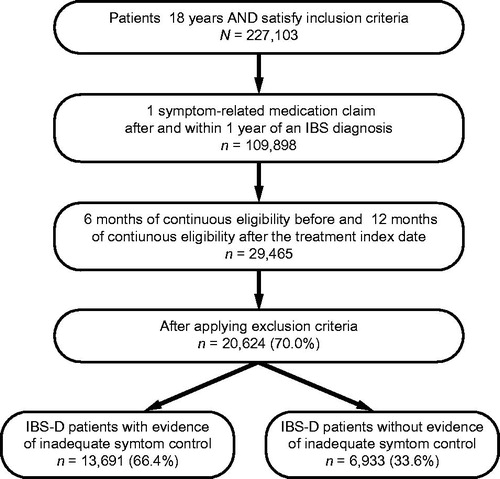

A total of 20,624 patients with IBS-D met the identification criteria and were included in the study. Of these, 13,691 (66.4%) had evidence of inadequate symptom control during the 12-month study period (). Among IBS-D patients with evidence of inadequate symptom control, mean age (±SD) was 49.1 (±16.8) years and 79.5% were female; among those without evidence of inadequate symptom control, mean age was 48.1 (±17.5) years and 74.6% were female (). Patients with evidence of inadequate symptom control had a significantly higher mean ECI score (2.1 vs 1.5, p < .01), as well as a significantly higher percentage of all general and GI-related comorbidities of interest compared with those without evidence of inadequate symptom control (all p < .01) ().

Indicators of inadequate symptom control

Switching from one symptom-related treatment to another was the most frequent indicator of inadequate symptom control, occurring in 76.0% of patients with evidence of inadequate symptom control during the 12-month study period (). Other common indicators of inadequate symptom control included surgery/medical procedures indicating treatment failure while on treatment and a diagnosis of a condition indicating treatment failure while on treatment, occurring in 31.6% and 26.7% of patients, respectively ().

Table 2. Identification of inadequate symptom control.

Treatment patterns

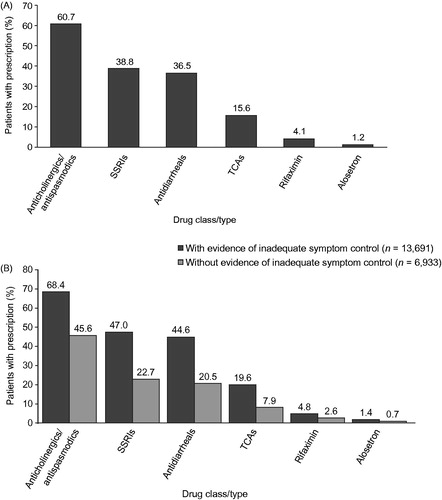

Overall, the most commonly used treatments among all patients with IBS-D were anticholinergics/antispasmodics (60.7%) (). The most common symptom-related treatments identified among patients with and without evidence of inadequate symptom control were anticholinergics/antispasmodics (68.4% and 45.6%), followed by SSRIs (47.0% and 22.7%) and antidiarrheals (44.6% and 20.5%) (). Rifaximin use for IBS-D was identified for <5% of patients, while alosetron was used by <2% of patients in the overall study population.

Figure 2. Prescription use among IBS-D patients (some patients simultaneously had prescriptions of multiple classes): (A) Overall prescription use for all patients in the study; (B) Prescription use among IBS-D patients with and without evidence of inadequate symptom control (n = 20,624). IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

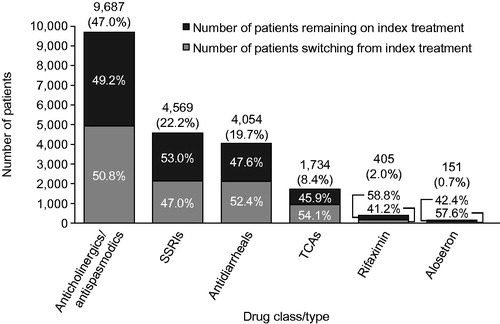

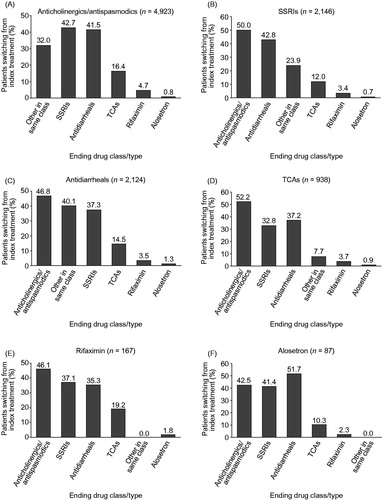

Slightly over half of all IBS-D patients switched from their index treatment (50.4%) (), with approximately half of patients switching from any of the index treatments (41.2–57.6%) (). Patients switching from an index treatment of anticholinergics/antispasmodics mainly switched to SSRIs (42.7%) or antidiarrheals (41.5%), while patients switching from an index treatment of SSRIs or antidiarrheals primarily switched to anticholinergics/antispasmodics (50.0% and 46.8%) (). Overall, 3.5% of patients received add-on drug therapy, with the most common combination being addition of an anticholinergic/antispasmodic to antidiarrheal therapy (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 3. Treatment-switching patterns among IBS-D patients (n = 20,624). IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Figure 4. Percentage of patients switching from an index treatment of: (A) anticholinergics/antispasmodics; (B) SSRIs; (C) antidiarrheals; (D) TCAs; (E) rifaximin; and (F) alosetron to a drug in another class. Patients may have switched to multiple drug classes. SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Total annual healthcare resource utilization and costs

During the 12-month study period, IBS-D patients with evidence of inadequate symptom control utilized significantly more healthcare resources than those without evidence of inadequate symptom control. This included a higher percentage of hospitalizations (12.0% vs 6.0%), ER visits (37.1% vs 22.6%), and outpatient services (73.0% vs 60.7%, all p < .01) (). Patients with evidence of inadequate symptom control also had a significantly higher mean number of physician office visits (11.0 vs 8.1) and prescription fills per year (40.0 vs 26.7, both p < .01) (), as well as a greater mean number of monthly (30-day) prescription fills annually (28.2 vs 19.2, p < .01).

Figure 5. Healthcare resource utilization among IBS-D patients with and without evidence of inadequate symptom control: (A) Percentage of patients utilizing healthcare resources based on hospitalizations, ER visits, and outpatient services; (B) Volume of utilization based on physician office visits and prescriptions per year. *p < .01. aOutpatient services include diagnostic imaging or diagnostic ultrasound services. ER, emergency room; IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea.

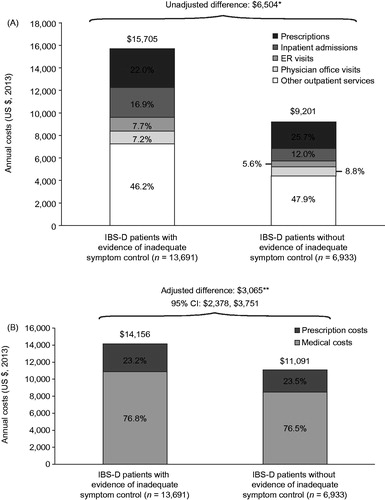

IBS-D patients with evidence of inadequate symptom control incurred $6,504 more in unadjusted mean annual all-cause costs compared with patients without evidence of inadequate symptom control (p < .01), an incremental difference of $5,412 (83%) from medical costs and $1,092 (17%) from prescription costs (). Other outpatient services, including laboratory and diagnostic tests, were the primary driver of costs for both cohorts (46.2% for IBS-D patients with evidence of inadequate symptom control and 47.9% for IBS-D patients without evidence of inadequate symptom control). After adjustment for demographic and health characteristics, inadequate IBS-D symptom control was associated with incremental total annual all-cause healthcare costs of $3,065 (p < .01), of which $2,391 (78%) were from medical costs and $674 (22%) were from prescription costs ().

Figure 6. Total annual all-cause medical and prescription costs: (A) Unadjusted and (B) adjusted costs among IBS-D patients with and without evidence of inadequate symptom control. *p < .01; **p < .01, difference was adjusted for demographics, ECI score, and general and GI-related comorbidities not included in the ECI score. CI, confidence interval; ECI, Elixhauser comorbidity index; ER, emergency room; GI, gastrointestinal; IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea.

Discussion

In this US commercially insured population, approximately two-thirds of patients with IBS-D had evidence of inadequate symptom control within 1 year of initiating a prescription treatment for IBS-D, irrespective of the treatment used. Inadequate IBS-D symptom control was associated with a substantial economic burden, even after controlling for demographic characteristics and comorbidities. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine IBS-D symptom control among patients who received a symptom-related prescription medication and to estimate the healthcare resource use and costs of inadequate symptom control associated with currently available prescription therapies for IBS-D.

These results highlight the high rate of inadequate symptom control with many commonly used treatments for IBS-D, with 66.4% of IBS-D patients having at least one observable indicator of inadequate symptom control while on their initial prescription therapy during the 12-month study period. This is perhaps unsurprising, given the symptom-specific nature of many treatments, and suggests a substantial unmet need for therapies that effectively treat and manage the multiple symptoms of IBS-DCitation8,Citation10. These findings also emphasize the need for more effective treatment early on with initial therapies, which could reduce the healthcare resource use and costs associated with inadequate symptom control.

The majority of patients in this population were prescribed anticholinergics/antispasmodics or SSRIs, potentially suggesting a focus on treating the abdominal pain associated with IBS-D. The use of antidiarrheal agents was lower than might be expected, potentially reflecting patient access to these therapies as over-the-counter medications rather than as prescription treatments. The use of rifaximin for IBS was also low (2%), although it is important to note that this study was conducted before rifaximin was approved for the treatment of IBS-D, and its use for IBS-D in this study was inferred based on associated claims for IBS.

Along with greater resource use, IBS-D patients with inadequate symptom control incurred significantly greater costs. Even after adjusting for demographic and health characteristics, the increased cost associated with inadequate symptom control in IBS-D remained significant, amounting to over $3,000 per IBS-D patient per year. Increased costs were primarily driven by costs associated with more frequent use of medical services, which accounted for 78% of the total all-cause costs. It is possible that inadequate symptom control could exacerbate IBS-D-related comorbidities and complications, which could account for a substantial portion of the costs. Additionally, patients with unresolved GI symptoms may exhibit increased healthcare-seeking behavior and may receive increased medical attention for general co-morbid conditions as well as for IBS-D.

Overall, patients with evidence of inadequate symptom control (i.e. those not being treated effectively) during the defined study period used more medical resources and incurred higher costs because their condition was not adequately managed. In addition to highlighting the significant unmet need for effective therapeutic options, these findings also suggest higher overall healthcare costs may be incurred if a patient is required to fail other therapies prior to receiving a subsequent treatment (i.e. formulary step edits). Appropriately diagnosing and treating IBS-D patients more effectively earlier in the course of managing their condition could, therefore, potentially reduce healthcare resource use and costs.

Limitations

As with any retrospective claims database analysis, the results of this study should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. First, definitive diagnoses are not available in claims data, and, while ICD-10-CM includes a diagnosis code for IBS-D, no specific ICD-9-CM diagnosis code exists in the current claims data for IBS-D. The lack of a diagnosis code and the inconsistent use of ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for IBS and diarrhea as standalone conditions impedes the accurate identification of patients with IBS-D in current administrative claims database analyses. Accordingly, classification of patients as potential IBS-D cases was informed by expert clinical opinion and prior claims analyses in IBS-CCitation11, and identification criteria were constructed based on available diagnostic codes and pharmacy prescriptions, which may have led to potential classification bias affecting the cost estimates. However, misclassification of patients within a study would be expected to bias results in such a way that the groups appear more similar than if misclassification were minimal. To the extent that ICD-9-CM codes must be used to examine resource use and costs among IBS-D patients, further research should be undertaken to validate the identification of these patients in claims until a specific diagnosis code for IBS-D is available in claims databases.

Identification of inadequate symptom control was also implied from the claims data based on pre-specified criteria. As such, the incidence may have been under-estimated, since only events for which claims had been filed were captured. Furthermore, the overall rate of inadequate symptom control observed in this study may be an under-estimation, as observable indictors of inadequate symptom control were required to occur during the course of treatment in order to be attributable to the index treatment, representing a conservative means of defining inadequate symptom control. Indicators of inadequate symptom control occurring after treatment discontinuation were not captured.

Conversely, the incidence may have been over-estimated due to the assumption that all events captured, such as diagnoses of other conditions, surgery/medical procedures, or changing treatment regimen, were attributable to inadequate IBS-D symptom control and not to any other cause. In particular, diagnoses of other GI diseases, such as microscopic colitis or Crohn’s disease, occurring following treatment for IBS-D, may have been due to an initial misdiagnosis of IBS-D, reflecting the challenges associated with the appropriate diagnosis of patients with this condition rather than inadequate symptom control.

Although the analyses controlled for demographic characteristics and comorbidities, residual confounding of unmeasured variables cannot be ruled out. In addition, the generalizability of the results is limited by the fact that this study included only patients who were commercially insured in the US.

Conclusions

Inadequate symptom control is highly prevalent among patients being treated for IBS-D and is associated with a substantial economic burden. There exists a significant unmet need for more effective therapeutic options to treat and manage the multiple symptoms of IBS-D. Treating IBS-D patients effectively early in the management of their condition could potentially reduce healthcare resource use and costs associated with continued healthcare-seeking behavior among those treated inadequately with initial therapies.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funding for this manuscript was provided by Allergan plc. The authors received no compensation related to the development of the manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

JLB and DAA are employees of Allergan plc and own stock/stock options. KM is an employee of Axtria Inc. AJA was an employee of Axtria Inc. at the time this study was conducted. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

Data included in this manuscript were presented in poster form at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Nexus Meeting, Orlando, FL, October 26–29, 2015.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Steven J. Shiff, MD, for providing clinical consultation on patient identification criteria and disease comorbidities. They would also like to thank Karen B. Chien, PhD, of Complete HealthVizion, Inc., Chicago, IL, for editorial assistance in the writing and revision of the draft manuscript on the basis of detailed discussion and feedback from all the authors, funded by Allergan plc.

References

- Cash BD, Chey WD. Irritable bowel syndrome - an evidence-based approach to diagnosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;19:1235-45

- Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:712-21

- Saito YA, Schoenfeld P, Locke GRI. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1910-15

- Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480-91

- Hulisz D. The burden of illness of irritable bowel syndrome: current challenges and hope for the future. J Manag Care Pharm 2004;10:299-309

- Buono JL, Mathur K, Averitt A, et al. Economic burden of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: retrospective analyses of a US commercially insured population. Poster P1964 presented at the American College of Gastroenterology Annual Scientific Meeting, Honolulu, HI, October 16–21, 2015

- Buono JL, Carson RT, Flores NM. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and indirect costs among patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Poster K03 presented at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Nexus Meeting, Orlando, FL, October 26–29, 2015

- Chang L, Lembo A, Sultan S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014;147:1149-72

- Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP. Irritable bowel syndrome: modern concepts and management options. Am J Med 2015;128:817-27

- Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, et al. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109(Suppl1):S2-S26

- Guerin A, Carson RT, Lewis B, et al. The economic burden of treatment failure amongst patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation or chronic constipation: a retrospective analysis of a Medicaid population. J Med Econ 2014;17:577-86

- Frank A. IBS in America: Survey Highlights Physical, Social and Emotional Impact. Bethesda, MD, USA: American Gastroenterological Association; 2015

- Hughes PA, Harrington AM, Castro J, et al. Sensory neuro-immune interactions differ between irritable bowel syndrome subtypes. Gut 2013;62:1456-65

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8-27

- Leong SA, Barghout V, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic consequences of irritable bowel syndrome: a US employer perspective. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:929-35

- Mitra D, Davis KL, Baran RW. All-cause health care charges among managed care patients with constipation and comorbid irritable bowel syndrome. Postgrad Med 2011;123:122-32

- Patel RP, Petitta A, Fogel R, et al. The economic impact of irritable bowel syndrome in a managed care setting. J Clin Gastroenterol 2002;35:14-20

- Doshi JA, Cai Q, Buono JL, et al. Economic burden of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: a retrospective analysis of health care costs in a commercially insured population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014;20:382-90