Abstract

Objectives: To examine treatment patterns, treatment effectiveness, and treatment costs for 1 year after patients with rheumatoid arthritis switched from a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, or infliximab), either cycling to another TNFi (“TNFi cyclers”) or switching to a new mechanism of action (abatacept, tocilizumab, or tofacitinib) (“new MOA switchers”).

Methods: This retrospective cohort study used administrative claims data for a national insurer. Treatment persistence (without switching again, restarting, or discontinuing), treatment effectiveness (defined below), and costs were assessed for the 12-month post-switch period. Patients were “effectively treated” if they satisfied all six criteria for a treatment effectiveness algorithm (high adherence, no dose increase, no new conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, no subsequent switch in therapy, no new/increased oral glucocorticoids, and <2 glucocorticoid injections). Multivariable logistic models were used to adjust for baseline factors.

Results: The database included 581 new MOA switchers and 935 TNFi cyclers. New MOA switchers were 39% more likely than TNFi cyclers to persist after the switch (odds ratio [OR] = 1.39; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.12–1.74; p = .003) and 36% less likely to switch therapy again (OR = 0.64; 95% CI = 0.51–0.81; p < .001). New MOA switchers were 43% more likely than TNFi cyclers to be effectively treated (OR = 1.43; 95% CI = 1.11–1.85; p = .006). New MOA switchers had 16% lower drug costs than TNFi cyclers (cost ratio = 0.84; 95% CI = 0.79–0.88; p < .001) and 11% lower total costs of rheumatoid arthritis-related medical care (cost ratio = 0.89; 95% CI = 0.84–0.94; p < .001).

Limitations: Claims payments may not reflect rebates or other cost offsets. Medical and pharmacy claims do not include clinical end-points or reasons that lead to new MOA switching vs TNFi cycling.

Conclusions: These results support switching to a new MOA after a patient fails treatment with a TNFi, which is consistent with recent guidelines for the pharmacologic management of established rheumatoid arthritis.

Introduction

When a patient with rheumatoid arthritis fails treatment with a first tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) because of inadequate response after 3 months or more, or because of lack of tolerability, switching to another therapy may be necessary to achieve treatment goalsCitation1–3. Historically, the most common switches have been to cycle between multiple TNFi agents (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab)Citation4–9. Several disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) with alternative mechanisms of action (MOA), such as abatacept, rituximab, tocilizumab, and tofacitinib, provide additional options for switching. Other new MOA DMARDs, such as sarilumabCitation10,Citation11, sirukumabCitation12, and baricitinibCitation13–15, are in late stages of development for rheumatoid arthritisCitation16,Citation17. With increasing treatment options available, studies are needed to better understand the outcomes and costs of either cycling to another TNFi or switching to a new MOA DMARDCitation18.

Registry studies, retrospective cohort data analyses, and a prospective observational study reported that, after failing TNFi therapy for rheumatoid arthritis, switching to a new MOA DMARD (rituximab) is more effective than cycling to another TNFiCitation5,Citation7,Citation19–22. A retrospective chart review of eight community-based rheumatology practices in the US reported that treatment response rates were better among new MOA switchers than TNFi cyclersCitation23. More recently, a registry database analysis reported that TNFi cyclers and patients who switched from a TNFi to a new MOA DMARD (abatacept) had similar effectiveness after the switchCitation24. A small, single-center study also reported no significant difference in efficacy between a new MOA DMARD (tocilizumab) and a TNFi (etanercept) after failure of another TNFi (infliximab)Citation25. However, a systematic review and Bayesian analysis of published studies reported that switching to abatacept, tocilizumab, or rituximab each was associated with a greater response rate compared with TNFi cyclingCitation26.

A retrospective claims database analysis can examine outcomes across all available therapies across a large patient population in a real-world setting, including patients who might not be eligible for a prospective study. A key limitation of claims data is that they typically do not include clinical outcomes. To address this gap, a claims-based treatment effectiveness algorithm has been developed for a Veterans Health Administration rheumatoid arthritis patient population for which both claims data and longitudinal registry data for disease activity are availableCitation27. When the claims data were compared with Disease Activity Scores with 28-joint counts (DAS-28) from the same population, this algorithm had acceptable positive predictive value (76%), negative predictive value (90%), sensitivity (72%), and specificity (91%) for treatment effectiveness of biologic therapy in rheumatoid arthritisCitation27. The algorithm estimates treatment effectiveness based on criteria that combine several measures of adherence, dosing, concomitant therapies, and switching to another therapy.

The objective of this real-world study was to examine and compare treatment patterns, treatment effectiveness (based on this claims-based algorithm), treatment costs, and costs per effectively treated patient for 1 year after patients with rheumatoid arthritis switched from a prior TNFi, either to another TNFi or to a new MOA DMARD.

Patients and methods

Study design

This retrospective study used administrative claims data from July 2011 to September 2015 for patients included in the Optum Research database. This database is geographically diverse across the US and contains healthcare claims from 1993 to the present. In 2015, data relating to >18.6 million individuals with both medical and pharmacy benefit coverage were available. Demographics of individuals in the database are representative of the US general population. All records were de-identified for this study and no identifiable protected health information was extracted or accessed, pursuant to the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Patients

The study included patients who received a TNFi (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, or infliximab), either as new or ongoing treatment, between January 1, 2012, and September 30, 2014 (the patient identification period), to reflect current practice at the time the analysis was conducted. The date of the patient’s first TNFi claim in this period was considered the patient’s index date. Patients needed to be continuously enrolled in the health plan for at least 6 months before (pre-index period) and at least 12 months after (post-index period) the index date.

All patients were aged 18 years or greater on the index date and had a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (ICD-9: 714.0x) in the primary or secondary position on a medical claim any time pre-index or within 30 days post-index. Patients were excluded from the study if they had other autoimmune conditions for which these therapies are used (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or juvenile idiopathic arthritis) in any position on a medical claim pre-index or post-index.

To limit the analysis to TNFi cyclers and new MOA switchers, patients needed to have at least one pharmacy claim in the 12-month post-index period either for a different TNFi or for a new MOA DMARD, which included non-TNFi biologics (abatacept or tocilizumab) or a synthetic targeted DMARD (tofacitinib). The date of the first switch claim was considered the switch date. To assess outcomes of switching therapy, patients needed to be continuously enrolled for at least 12 months after the switch date (the post-switch period). The analysis did not include patients who switched in the post-index period to anakinra (because too few patients switched to anakinra) or to rituximab (because adherence and treatment effectiveness could not be assessed using the claims-based effectiveness algorithm).

Treatment persistence

During the 12-month post-switch period, each patient was categorized as having one of four mutually exclusive treatment patterns based on pharmacy claims in the following hierarchy: (1) switched again to a third TNFi or new MOA DMARD; (2) restarted the second therapy after a treatment gap of at least 60 days, without first switching again; (3) discontinued the second therapy for at least 60 days, without switching again or restarting the second therapy during the 12-month post-switch period; or (4) persisted with the second therapy, without switching again, restarting, or discontinuing (based on a ≥60-day gap). A 60-day treatment gap is commonly used to measure biologic treatment persistence in rheumatoid arthritisCitation28–30.

Treatment effectiveness

The claims-based treatment effectiveness algorithmCitation27 was applied to medical and pharmacy claims data for 12 months after the switch date to estimate treatment effectiveness for the switch medication. Patients who satisfied all six of the algorithm criteria () for the 12 months after the switch date were considered to be effectively treated.

Table 1. Criteria of the claims-based algorithm for treatment effectiveness during the 12-month post-switch period.

Costs

Costs were analyzed for two categories: (1) any TNFi or new MOA DMARD used in the post-switch period; and (2) any rheumatoid arthritis-related medical care costs, including drug costs. Costs of TNFi and new MOA DMARDs used the total amount paid by the health plan and patient, combined, for pharmacy claims (subcutaneous DMARDs) and infusions (intravenous DMARDs). Rheumatoid arthritis-related medical care costs used the total amount paid by the health plan and patient, combined, for inpatient, outpatient, emergency room, and laboratory claims with a rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis in any position, as well as total amount paid by the health plan and patient, combined, for conventional synthetic DMARDs (hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate, and sulfasalazine). TNFi and new MOA DMARD costs were inflated to December 2015 costs by using price evolution data from Analysource (DMD America, Inc.; Syracuse, NY). Rheumatoid arthritis-related medical care costs were inflated to December 2015 costs with the medical component of the Consumer Price Index.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC). Treatment patterns and treatment effectiveness were evaluated for the 12-month post-switch period in two cohorts: TNFi cyclers who switched to a different TNFi on the switch date, and new MOA switchers who switched from a TNFi to a new MOA DMARD on the switch date. Proportions of patients for each outcome were compared between cohorts (new MOA switchers vs TNFi cyclers) with Chi-square tests. Cost per effectively treated patient was calculated from the average 12-month post-switch cost, divided by the proportion of effectively treated patients (as classified by achievement of all six algorithm criteria).

Multivariable logistic models were used to calculate odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values for switching again, treatment persistence, and treatment effectiveness in the 12-month post-switch period. The following independent variables were selected from the claims database because they were thought to be clinically relevant: treatment cohort, age, sex, insurance plan type, index year, geographic region, Quan Charlson comorbidity score pre-index, hydroxychloroquine pre-index, leflunomide pre-index, methotrexate pre-index, sulfasalazine pre-index, count of unique rheumatoid arthritis medications pre-index, total healthcare expenditures pre-index, rheumatoid arthritis-related expenditures pre-index, and office visit count pre-index. Multivariable generalized linear models for post-switch costs used the same covariates. Model fit was assessed for each model with C-statistic and R-square.

Results

Study population

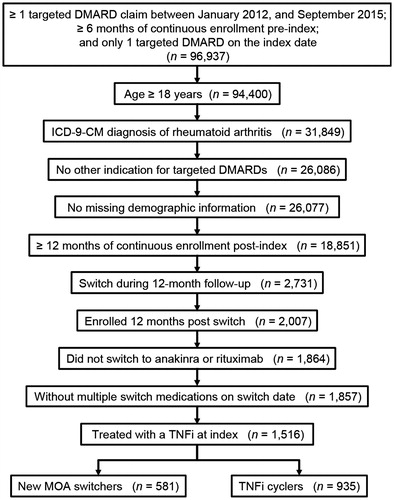

A total of 1,516 patients met all study criteria, including 581 new MOA switchers and 935 TNFi cyclers (). Patient demographics at the initial switch are summarized in . Approximately 80% of patients in both groups were female and new MOA switchers were older than TNFi cyclers (mean, 53.6 vs 51.9 years; p = .005).

Figure 1. Sample size attrition. DMARD: disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; MOA: mechanism of action; TNFi: tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Table 2. Patient characteristics at the first switch.

Treatment persistence

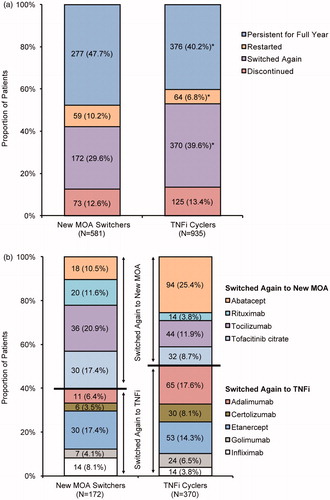

In the analysis of overall treatment patterns during the 12-month post-switch period (), new MOA switchers were more likely than TNFi cyclers to persist on the second medication (47.7% vs 40.2%; p = .004), more likely to restart therapy after a ≥60-day treatment gap (10.2% vs 6.8%; p = .022), and less likely to switch to a third medication (29.6% vs 39.6%; p < .001). Rates of discontinuing therapy in the 12-month post-switch period were similar between new MOA switchers and TNFi cyclers (12.6% vs 13.4%; p = .651). In the multivariable analysis (), new MOA switchers were 39% more likely than TNFi cyclers to persist on treatment during the 12-month post-switch period (OR = 1.39; 95% CI = 1.12–1.74; p = .003).

Figure 2. Treatment patterns after the initial switch. (a) Overall treatment patterns (all patients). (b) New treatment after switching again (patients who switched again). MOA: mechanism of action; TNFi: tumor necrosis factor inhibitor. *p < .05 vs new MOA switchers by Chi-square test.

Table 3. Multivariable analyses of predictors for treatment persistence, switching again, and treatment effectiveness in the 12-month post-switch period.

In the multivariable regression analysis (), new MOA switchers were 36% less likely than TNFi cyclers to switch therapy again in the 12-month post-switch period (OR = 0.64; 95% CI = 0.51–0.81; p < .001). Switches to a third medication are summarized by individual DMARD for each group in .

Treatment effectiveness

New MOA switchers were more likely than TNFi cyclers to be effectively treated (25.5% vs 20.4%; p = .022) (). Individual treatment effectiveness algorithm criteria that were achieved by significantly more new MOA switchers compared with TNFi cyclers were high adherence (42.3% vs 35.5%; p = .008), no dose increase (97.9% vs 89.2%; p < .001), and no switch to another TNFi or new MOA DMARD (70.4% vs 60.4%; p < .001). Rates for other criteria (no new conventional synthetic DMARD, no new or increased oral glucocorticoids, and <2 glucocorticoid injections) were not significantly different between new MOA switchers and TNFi cyclers. In the multivariable analysis (), new MOA switchers were 43% more likely than TNFi cyclers to be effectively treated (OR = 1.43; 95% CI = 1.11–1.85; p = .006).

Table 4. Achievement of treatment effectiveness algorithm criteria in the 12-month post-switch period.

Costs

The mean cost for the first switch claim, prior to adjustment for inflation, was $1,976 for new MOA switchers and $2,969 for TNFi cyclers (). Mean treatment costs for rheumatoid arthritis in the 12-month post-switch period were significantly lower for new MOA switchers compared with TNFi cyclers, including those for any TNFi or new MOA DMARD that was used in the post-switch period ($29,001 vs $34,917; p < .001) and the total cost of rheumatoid arthritis-related medical care ($37,804 vs $42,116; p < .001) (). Costs of the individual components of rheumatoid arthritis-related medical care are provided in . When costs for the first 12 months post-switch were combined with the overall treatment effectiveness rate (), the costs per effectively treated patient were lower for new MOA switchers than TNFi cyclers, including those for any TNFi or new MOA DMARD post-switch ($113,849 vs $170,929) and the total cost of rheumatoid arthritis-related medical care ($148,408 vs $206,168). In the multivariable analysis (), new MOA switchers had 16% lower costs than TNFi switchers for TNFi and new MOA DMARD therapy (cost ratio = 0.84; 95% CI = 0.79–0.88; p < .001) and 11% lower total costs for rheumatoid arthritis treatment (cost ratio = 0.89; 95% CI = 0.84–0.94; p < .001).

Table 5. Mean cost of first claim for switch medication.Table Footnote*

Table 6. Costs in the 12-month post-switch period.Table Footnote*

Table 7. Component costs for rheumatoid arthritis-related medical care in the 12-month post-switch period, inflated to December 2015 costs with the medical component of the consumer price index.

Table 8. Multivariable analyses of predictors for costs in the 12-month post-switch period.

Discussion

In this analysis of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who received a TNFi between January 2012 and September 2014, and then switched to another therapy, a majority were TNFi cyclers who switched to another TNFi. Previous reports also consistently showed that patients are more likely to cycle to another TNFi therapy than they are to switch to a new MOA DMARDCitation4–9. However, the outcomes after switching in this study, including treatment persistence, treatment effectiveness, and rheumatoid arthritis-related medical care, supported switching to new MOA over TNFi cycling.

New MOA switchers were significantly more likely than TNFi cyclers to persist on therapy throughout the 12-month post-switch period. A large registry study of 1,004 patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the US reported that 16% of patients who switched from a TNFi to rituximab and 29% of patients who cycled TNFi therapy subsequently switched to another therapy during follow-up, but the report did not include a statistical comparison of these valuesCitation7. Similar results were reported previously in single-center observational registry studies. A study of 201 patients with rheumatoid arthritis at a center in Italy determined that new MOA switchers were 2.3-fold more likely than TNFi cyclers to persist on therapy, and the significant difference between groups was maintained when the analyses were stratified by the reason for failure of the previous TNFi (adverse event or non-toxic causes)Citation9. A registry study of 169 patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Japan reported that patients had greater persistence after switching from etanercept to tocilizumab compared with TNFi cycling from etanercept to adalimumab/infliximab; persistence was also greater for switching from adalimumab/infliximab to tocilizumab or etanercept compared with cycling between adalimumab and infliximabCitation31. Another registry study in Japan reported that 52-week persistence rates were not significantly different among switchers to the non-TNFi biologics abatacept and tocilizumab or cyclers to the TNFi etanercept, but that study included only 89 patients, and persistence rates for other TNFi or new MOA DMARDs were not evaluatedCitation32.

The results of this study confirmed those from three studies in other patient populations. In this study, new MOA switchers were significantly less likely than TNFi cyclers to switch again to another TNFi or new MOA DMARD during follow-up (30% vs 40%, respectively). In a claims-based analysis of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and either commercial or Medicare Supplemental insurance, 28% of new MOA switchers and 37% of TNFi cyclers switched to a third medication after their initial switchCitation6. In another US claims database analysis of patients with either commercial or Medicare Supplemental insurance, the rates for switching to a third biologic within 1 year of the second biologic ranged from 23.4–31.2%Citation33. A recent claims-based analysis of commercially insured patients with rheumatoid arthritis reported that 30% of new MOA switchers and 35% of TNFi cyclers switched again after their initial switchCitation34.

When the claims-based algorithm for treatment effectivenessCitation27 was applied to this database, new MOA switchers were more likely than TNFi cyclers to achieve all six of the criteria for treatment effectiveness, as well as the individual criteria for high adherence, no dose increase, and no switch to another TNFi or new MOA DMARD. TNFi cycling was not superior to new MOA switching for any criterion of the treatment effectiveness algorithm.

The rates of effectively treated patients in this study were consistent with those reported previously in other studies that used the algorithm to assess treatment effectiveness for TNFi or new MOA DMARDsCitation27,Citation34–41. The algorithm was initially developed and validated with abatacept, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and rituximab in a Veterans Health Administration populationCitation27, and a subsequent analysis demonstrated the predictive value of the algorithm for initial biologic therapy with etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab in commercially insured populationsCitation35. This study extended the algorithm to apply it to patients who received newer medications, including certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab, and tofacitinib. Dose-escalation criteria not in the original validation needed to be applied to the newer medications; other algorithm criteria were not changed for these medications. This approach was similar to that used in several other studies that applied the algorithm to newer medicationsCitation34, Citation36–41.

Costs in the first year after the switch were significantly lower for new MOA switchers than TNFi cyclers, including the costs for all TNFi or new MOA DMARDs as well as the costs for all rheumatoid arthritis-related medical care in the 12-month post-switch period. Thus, new MOA switching was associated with both lower costs and greater response rates according to the treatment effectiveness algorithm. The resulting cost per effectively treated patient in the first year was more than $50,000 lower among new MOA switchers compared with TNFi cyclers for both of the cost categories.

To assess the outcomes of switching therapy, this analysis was restricted to patients who switched within 12 months post-index and then had at least 12 more months of claims data post-switch. More than 85% of patients who satisfied other study eligibility criteria were removed from the analysis because they did not switch within 12 months post-index. The sample size and generalizability of results in future studies might be increased by including patients who switch therapy more than 12 months post-index; however, some of these patients will need to be excluded from the study because they do not have more than 12 months of additional claims data post-switch. Conversely, the study examined outcomes of switching, regardless of the duration of TNFi therapy before the switch. Thus, the index claim in this study was not necessarily the first TNFi claim the patient ever received.

Retrospective claims-based analyses have several advantages, including the ability to assess real-world medication use in a variety of patient populations, which enhances the generalizability of the results and the ability to include larger patient populations. Claims-based analyses can provide information about actual payments, but those claims payments may not reflect rebates or other cost offsets. Mean paid amounts for the first claim of the switch medication were included in this report to make the results more relatable to other populations. Claims-based analyses are also subject to limitations that may not apply to prospective comparative effectiveness research. These databases do not have specific clinical outcomes such as DAS-28 to directly assess clinical response, so a treatment effectiveness algorithm or surrogate needs to be used to estimate treatment effectiveness. The claims-based treatment effectiveness algorithm that was used in this study was derived and validated in a database that included both claims data and clinical outcomes, and was shown to have high predictive value compared with clinical outcomesCitation27.

Medical and pharmacy claims also do not include a reason for switching therapy, which may include not only clinical outcomes (e.g. lack or loss of treatment effectiveness, intolerance), but also other factors (e.g. cost, preference for a different route of administration). These patient-specific factors may lead prescribers to select new MOA switching or TNFi cycling for specific reasons that may or may not be measurable in these data, which may explain the observed differences between the cohorts in this study at baseline. To address this, multivariable analyses of treatment persistence, switching again, and treatment effectiveness after the switch were adjusted for other clinical and economic factors at baseline. In each multivariable analysis, the new MOA switchers had significantly better outcomes than the TNFi cyclers. A few of the other independent variables were significant predictors in the multivariable analyses. For example, patients with greater comorbidity scores and higher total healthcare expenditures pre-index had significantly lower odds of treatment persistence or treatment effectiveness after the initial switch. These findings suggested that sicker patients had worse outcomes than healthier patients, as expected.

New MOA switchers may have had other characteristics not reported in the claims that predisposed them to better persistence and treatment effectiveness compared with TNFi cyclers. Patients were pooled into one of two categories in this study—TNFi cyclers or new MOA switchers—and data were not analyzed for individual DMARDs. Previous studies have shown that outcomes of switching therapy may vary among individual TNFiCitation19,Citation31,Citation42 and among individual new MOA DMARDsCitation33. Additional comparisons are warranted to examine treatment patterns, treatment effectiveness, and treatment costs among individual DMARDs after a switch in therapy. The total duration of prior TNFi use and reasons for discontinuation of the prior TNFi were not available in this claims database. Other research has shown that the reason for discontinuation of the prior TNFi, such as primary lack of efficacy, secondary loss of efficacy over time, or adverse events, may influence whether a patient responds to TNFi cycling vs new MOA switchingCitation43–45.

Nonetheless, these results were consistent with those from studies that reported reduced disease activity among patients who switched to a new MOA DMARD compared with TNFi cyclersCitation5,Citation7,Citation19–22,Citation26,Citation45. To our knowledge, only one prospective, randomized, interventional study has compared the efficacy of new MOA switching and TNFi cycling in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. That study reported that new MOA switchers had superior efficacy compared with TNFi cyclersCitation46. Thus, the results of our retrospective claims-based analyses were consistent with those of prospective observational and interventional studies that included assessments of disease activity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who switched from a TNFi to another therapy determined that new MOA switchers were significantly more likely than TNFi cyclers to persist on treatment after the switch and satisfy the criteria of a claims-based algorithm for treatment effectiveness, and they had significantly lower costs for rheumatoid arthritis-related medical care. These results support switching to a new MOA DMARD after a patient fails treatment with a TNFi, which is consistent with treatment guidelines for the pharmacologic management of established rheumatoid arthritisCitation3. Patient-specific factors, including those that were not available in this claims database analysis, also need to be considered in the decision to cycle to another TNFi or switch to a new MOA DMARD for an individual patient.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Employees of the study sponsors (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi) participated in the design and analysis of the study and the preparation of this article.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

BC and LKB are employees of Optum, which received funding from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi to conduct the research. CIC is an employee and stockholder of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. PM is an employee and stockholder of Sanofi. JRC is a paid consultant to Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Jonathan Latham of PharmaScribe, LLC, received funding from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals to assist the authors with the preparation and submission of the manuscript. The authors thank George J. Joseph, PhD, MS, for contributions to the study conception and design.

References

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:762-84

- Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:625-39

- Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1-26

- Bonafede M, Fox KM, Watson C, et al. Treatment patterns in the first year after initiating tumor necrosis factor blockers in real-world settings. Adv Ther 2012;29:664-74

- Soliman MM, Hyrich KL, Lunt M, et al. Rituximab or a second anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for rheumatoid arthritis patients who have failed their first anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy? Comparative analysis from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1108-15

- Harnett J, Wiederkehr D, Gerber R, et al. Real-world evaluation of TNF-inhibitor utilization in rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Econ 2016;19:91-102

- Harrold LR, Reed GW, Magner R, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of rituximab versus subsequent anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with prior exposure to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies in the United States Corrona registry. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:256

- Baser O, Ganguli A, Roy S, et al. Impact of switching from an initial tumor necrosis factor inhibitor on health care resource utilization and costs among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther 2015;37:1454-65

- Favalli EG, Biggioggero M, Marchesoni A, et al. Survival on treatment with second-line biologic therapy: a cohort study comparing cycling and swap strategies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:1664-8

- Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Kivitz AJ, et al. Sarilumab plus methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a phase III study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:1424-37

- Fleischmann R, Castelar-Pinheiro G, Brzezicki J, et al. Efficacy and safety of sarilumab in combination with csdmards in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis who were inadequate responders or intolerant of anti-TNF-i therapy: Results from a phase 3 Study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67(Suppl 10):Abstract 970

- Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Sheng S, et al. Sirukumab, a human anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibody: a randomised, 2-part (proof-of-concept and dose-finding), phase II study in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1616-25

- Keystone EC, Taylor PC, Drescher E, et al. Safety and efficacy of baricitinib at 24 weeks in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have had an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:333-40

- Tanaka Y, Emoto K, Cai Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib in Japanese patients with active rheumatoid arthritis receiving background methotrexate therapy: a 12-week, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled study. J Rheumatol 2016;43:504-11

- Genovese MC, Kremer J, Zamani O, et al. Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1243-52

- Reichert JM. Antibodies to watch in 2016. mAbs 2016;8:197-204

- Yamaoka K. Janus kinase inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2016;32:29-33

- Malottki K, Barton P, Tsourapas A, et al. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, rituximab and abatacept for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis after the failure of a tumour necrosis factor inhibitor: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2011;15:1-278

- Chatzidionysiou K, van Vollenhoven RF. Rituximab versus anti-TNF in patients who previously failed one TNF inhibitor in an observational cohort. Scand J Rheumatol 2013;42:190-5

- Kekow J, Mueller-Ladner U, Schulze-Koops H. Rituximab is more effective than second anti-TNF therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients and previous TNFalpha blocker failure. Biologics 2012;6:191-9

- Finckh A, Ciurea A, Brulhart L, et al. B cell depletion may be more effective than switching to an alternative anti-tumor necrosis factor agent in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to anti-tumor necrosis factor agents. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:1417-23

- Gomez-Reino JJ, Maneiro JR, Ruiz J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of switching to alternative tumour necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists versus switching to rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who failed previous TNF antagonists: the MIRAR Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1861-4

- Bergman MJ, Elkin EP, Ogale S, et al. Response to biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs after discontinuation of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Ther 2014;1:21-30

- Harrold LR, Reed GW, Kremer JM, et al. The comparative effectiveness of abatacept versus anti-tumour necrosis factor switching for rheumatoid arthritis patients previously treated with an anti-tumour necrosis factor. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:430-6

- Wakabayashi H, Hasegawa M, Nishioka Y, et al. Which subgroup of rheumatoid arthritis patients benefits from switching to tocilizumab versus etanercept after previous infliximab failure? A retrospective study. Mod Rheumatol 2012;22:116-21

- Kim HL, Lee MY, Park SY, et al. Comparative effectiveness of cycling of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors versus switching to non-TNF biologics in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to TNF-alpha inhibitor using a Bayesian approach. Arch Pharm Res 2014;37:662-70

- Curtis JR, Baddley JW, Yang S, et al. Derivation and preliminary validation of an administrative claims-based algorithm for the effectiveness of medications for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R155

- Mahlich J, Sruamsiri R. Persistence with biologic agents for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in Japan. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:1509-19

- Neubauer S, Cifaldi M, Mittendorf T, et al. Biologic TNF inhibiting agents for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: persistence and dosing patterns in Germany. Health Econ Rev 2014;4:32

- Wu E, Chen L, Birnbaum H, et al. Retrospective claims data analysis of dosage adjustment patterns of TNF antagonists among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2229-40

- Kobayakawa T, Kojima T, Takahashi N, et al. Drug retention rates of second biologic agents after switching from tumor necrosis factor inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis in Japanese patients on low-dose methotrexate or without methotrexate. Mod Rheumatol 2015;25:251-6

- Hirabara S, Takahashi N, Fukaya N, et al. Clinical efficacy of abatacept, tocilizumab, and etanercept in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:1247-54

- Johnston SS, McMorrow D, Farr AM, et al. Comparison of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy persistence between biologics among rheumatoid arthritis patients switching from another biologic. Rheumatol Ther 2015;2:59-71

- Bonafede M, Curtis JR, McMorrow D, et al. Treatment effectiveness and treatment patterns among rheumatoid arthritis patients after switching from a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor to another medication. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2016;8:707-15

- Curtis JR, Chastek B, Becker L, et al. Further evaluation of a claims-based algorithm to determine the effectiveness of biologics for rheumatoid arthritis using commercial claims data. Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15:404

- Curtis JR, Schabert VF, Harrison DJ, et al. Estimating effectiveness and cost of biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: application of a validated algorithm to commercial insurance claims. Clin Ther 2014;36:996-1004

- Curtis JR, Schabert VF, Yeaw J, et al. Use of a validated algorithm to estimate the annual cost of effective biologic treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Econ 2014;17:555-66

- Oladapo A, Barner JC, Lawson KA, et al. Medication effectiveness with the use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors among Texas Medicaid patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014;20:657-67

- Bonafede M, Johnson BH, Princic N, et al. Cost per patient-year in response using a claims-based algorithm for the 2 years following biologic initiation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Econ 2015;18:376-89

- Curtis JR, Chastek B, Becker L, et al. Cost and effectiveness of biologics for rheumatoid arthritis in a commercially insured population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2015;21:318-29

- Yun H, Xie F, Delzell E, et al. The comparative effectiveness of biologics among older adults and disabled rheumatoid arthritis patients in the Medicare population. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015;80:1447-57

- Frazier-Mironer A, Dougados M, Mariette X, et al. Retention rates of adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab as first and second-line biotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in daily practice. Joint Bone Spine 2014;81:352-9

- Virkki LM, Valleala H, Takakubo Y, et al. Outcomes of switching anti-TNF drugs in rheumatoid arthritis—a study based on observational data from the Finnish Register of Biological Treatment (ROB-FIN). Clin Rheumatol 2011;30:1447-54

- Remy A, Avouac J, Gossec L, et al. Clinical relevance of switching to a second tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor after discontinuation of a first tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011;29:96-103

- Emery P, Gottenberg JE, Rubbert-Roth A, et al. Rituximab versus an alternative TNF inhibitor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who failed to respond to a single previous TNF inhibitor: SWITCH-RA, a global, observational, comparative effectiveness study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:979-84

- Gottenberg JE, Brocq O, Perdriger A, et al. Non-TNF-targeted biologic vs a second anti-TNF drug to treat rheumatoid arthritis in patients with insufficient response to a first anti-TNF drug: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;316:1172-80