Abstract

Objective: Inter-regional comparison of health-reform outcomes in south-eastern Europe (SEE).

Methods: Macro-indicators were obtained from the WHO Health for All Database. Inter-regional comparison among post-Semashko, former Yugoslavia, and prior-1989-free-market SEE economies was conducted.

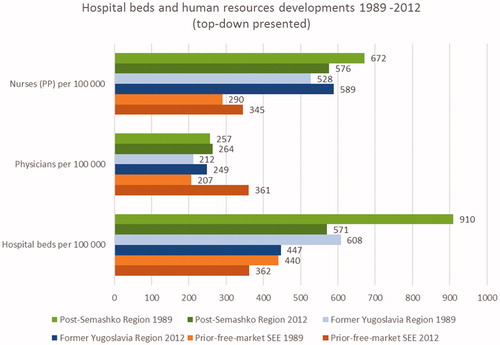

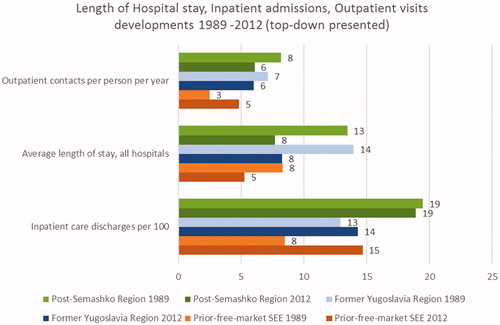

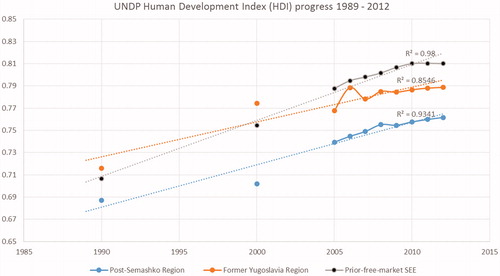

Results: United Nations Development Program Human Development Index growth was strongest among prior-free-market SEE, followed by former Yugoslavia and post-Semashko. Policy cuts to hospital beds and nursing-staff capacities were highest in post-Semashko. Physician density increased the most in prior-free-market SEE. Length of hospital stay was reduced in most countries; frequency of outpatient visits and inpatient discharges doubled in prior-free-market SEE. Fertility rates fell for one third in Post-Semashko and prior-free-market SEE. Crude death rates slightly decreased in prior-free-market-SEE and post-Semashko, while growing in the former Yugoslavia region. Life expectancy increased by 4 years on average in all regions; prior-free-market SEE achieving the highest longevity. Childhood and maternal mortality rates decreased throughout SEE, while post-Semashko countries recorded the most progress.

Conclusions: Significant differences in healthcare resources and outcomes were observed among three historical health-policy legacies in south-eastern Europe. These different routes towards common goals created a golden opportunity for these economies to learn from each other.

Introduction

During the Cold War era, the south-eastern European (SEE) region was divided between three major patterns of healthcare organization and financing. Greece, Turkey, and Cyprus—with their free market economies—mostly applied Western models of healthcare management and funding, while the other countries in the region were split alongside the Iron Curtain. The largest group, which included Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, and Hungary, followed the Semashko model inherited from the Soviet UnionCitation1. Yugoslavia and Albania, although being socialist countries, stayed mostly outside the Soviet geopolitical borders of influence. Before its dissolution following the civil wars of the 1990s, Yugoslavia had a municipally funded, decentralized healthcare systemCitation2. It was a supply oriented, curative system reliant on a massive hospital sector, thus resembling the Soviet systemCitation3, and, contrary to the Semashko model, was based on compulsory health insurance contributions. Its funding scheme was actually much closer to a Bismarck-type social health-insurance system. All the countries that were created from ex-Yugoslavia, including Bosnia, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia, share this heritage.

Eleven of the 14 SEE countries have undergone complex social transition from a former socialist era towards market-based economies. Healthcare reforms since 1991 have been very extensiveCitation4 and supported by local governments and serious investments from different international stakeholders, such as global financial institutions. Capacity-building investments provided by international consultancies as well as structural changes in healthcare organization, funding, and related legislative framework rapidly evolved, although the pace of these reforms has been uneven across the countries in the regionCitation5. The key expectations of these reforms were to adopt health-system models focusing on primary and preventive care instead of traditional, hospital-based models. The expectations also referred to shortened hospital stays and waiting lists for surgical patients, and improved accessibility to innovative medical technologies. The overall goals were improved population health and societal wellbeing.

There is an abundance of published evidence on the pace and nature of the transitional healthcare reforms among EU 2004 accession membersCitation6 and within the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) regionCitation7; however, there is a scarcity of knowledge on the inter-country differences between the healthcare reforms and their core outcomes achieved in the SEE region. Nine of the 14 SEE countries were thoroughly processed by the Health Systems in Transition report series issued by the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Local research published in English and/or local languages remains scattered around policy interests of single societies. So far there have been no systematic attempts to compare the evolution of national health systems and outcomes achieved among these countries in a methodologically sound manner and accounting for historical perspective. This paper aims to perform an inter-country and inter-regional comparison of different outcomes in population health and healthcare reforms in the SEE regionCitation8. The purpose of the analysis is to assess success rates of the different SEE countries in their converging strategies to improve healthcare.

Contributions like this one might be intriguing for the broader international audience, particularly within the European region. This should be the case because of the serious lack of published literature on SEE health reforms in major as well as local languages. Countries involved in the study could learn from the examples of their neighbors with regard to different pathways leading to the similar goals of increased health system efficiencyCitation9. The paper could also be relevant for other emerging global regions, such as Latin AmericaCitation10 or Central Asia, where a similar chain of historical events and impact of globalization led to the inevitable transformation of the national health systemsCitation11,Citation12.

Methods

In this study we compare the post-Semashko countries (Albania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Moldova, Romania) to the countries born from former Yugoslavia (Bosnia, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Slovenia) and to the free market SEE economies prior to 1989 (Cyprus, Greece, Turkey) based on three groups of micro-indicators, namely selected demographic indicators, mortality indicators, and health-capacity indicators. To achieve this, we use the indicators available from the WHO European Health for All Database HFA-DB for the period 1989–2012. Given the data available in the dataset, the selected demographic indicators were: live births per 1,000 population, crude death rate per 1,000 population, and total fertility rate. Selected mortality-based indicators were life expectancy at birth, estimated life expectancy (world health report), estimated infant mortality per 1,000 live births, maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, estimated maternal mortality per 100,000 live births (WHO/UNICEFF/UNFPA estimates), and abortions per 1,000 live births. Selected health system capacity indicators were (number of) hospitals per 100,000, primary healthcare units per 100,000, hospital beds per 100,000, private inpatient hospital beds as a percentage or proportion of all beds, physicians per 100,000, and nurses per 100,000. Health-resource utilization indicators selected were inpatient care discharges per 100, average length of stay, all hospitals, and outpatient contacts per person per year.

We choose these indicators based on expectations from healthcare reforms in post-Semashko and former Yugoslavia countries. As we mentioned previously, the aim of healthcare reforms was to encourage preventive care instead of hospital-based care and to provide more services in primary healthcare with the overall goal of improving population health. Given these parameters we expect that outpatient contacts per person, on average, increased in post-Semashko and former Yugoslavia countries during the period of 1989–2012. Also, we expect that average length of stay in hospitals and hospital beds per persons in those two groups of countries will, on average, decrease. We also expect that demographic indicators such as life expectancy at birth and median age will grow, while fertility rate will continue falling in line with long-term historical trends of population aging around the regionCitation13. Although some of these indicators are not acutely sensitive to policy shifts in the short-term, we believe that such a selection is sufficient to show the broad changes taking place in this region.

We analyzed data using top-down retrospective database analysis on a cross-sectional series of data on national health resources and indicators reported by the national authorities from 1989–2012. The results are presented in and . English-language published evidence in peer-reviewed Medline and Google Scholar-indexed journals was used to explain trends observed. Besides the independent academic publications, official reports of international organizations such as the World Bank, WHO European Observatory on Health Policies and Systems, OECD, and others who financed and conducted research in health policy and public-health issues on the SEE region were used also.

Figure 1. South-Eastern European (SEE) region. Hospital and medical staff capacities developments—inter-regional comparison of average indicator values within the country groups 1989 vs 2012 (or most approximate years available).

Figure 2. South-Eastern European (SEE) region. Frequency of inpatient discharges, outpatient visits and duration of hospital admissions—inter-regional comparison of average indicator values within the country groups 1989 vs 2012 (or most approximate years available).

Figure 3. South-Eastern European (SEE) region. UNDP Human Development Index (HDI)—inter-regional comparison of average indicator values within the country groups 1989 vs 2012 (or most approximate years available).

Table 1. South-Eastern European (SEE) region—demographic indicators and HDI across countries and regions—values reported to WHO by the national authorities in 1989/2012 or closest years available.

Table 2. South-Eastern European (SEE) region—mortality and morbidity based indicators across countries and regions—values reported to WHO by the national authorities in 1989/2012 or closest years available.

Table 3. South-Eastern European (SEE) region—healthcare resources and their utilization across countries and regions—values reported to WHO by the national authorities in 1989/2012 or closest years available.

Statistical methods used relied on arithmetic mean, standard deviation, median, and 3 years moving average trend extrapolation (for HDI indicator) as basic descriptive statistical measures of variability. Linear trend estimation was done using least squares method—R-squared value was used to point out long-term trend differences in linear extrapolated charts (to point out goodness of fit). Since we dealt with exclusive nationally representative data, no sampling technique was required. Commercial software such as Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS version 19 were used for the purpose for the study.

Data

WHO European Health for All Database HFA-DB provides insight to the health statistics, including basic demographics, health status, health determinants, and risk factors, and healthcare resources, utilization, and expenditure in the 53 countries in the WHO European Region. These data were compiled together based on a variety of sources such as WHO/Europe’s programs, partner organizations, UN agencies EUROSTAT, and the OECD.

Inter-country comparative and time series analysis was conducted. Post-Semashko countries were compared to the countries born from former Yugoslavia and free market SEE economies prior to 1989, lacking essential transition from planned to free market economies (Cyprus, Greece, Turkey)Citation14.

Results

Life expectancy increased by ∼4 years on average in all countries, with prior-free-market SEE achieving highest longevity. Fertility rates fell for up to one third in post- Semashko countries and prior-free-market SEE countries, as well as live births in all countries. Although crude death rates slightly decreased in prior-free-market SEE countries and post-Semashko countries, surprisingly they grew in the Former Yugoslavia region. Decreases in early childhood and maternal mortality rates were a huge success throughout the region, with post-Semashko systems recording the best progress. In absolute terms, the lowest values belonged to the Former Yugoslavia region.

Demographic trends noticed in the individual countries help us observe the long-term events taking place in the entire region. Albania and Turkey showed a substantial decrease in birth rates. Regardless of this, Turkish birth rates still remained substantially above those recorded elsewhere throughout the region (see ). Fertility rates decreased alongside birth rates in all three groups of countries, although most prominently in post-Semashko countries. A promising sign is the substantial decrease in abortion rates and improved survival of neonates and infants (several fold) in Serbia, Macedonia, Slovenia, and Cyprus in particular (see ).

Policy cuts to hospital beds and nursing staff capacities were led by post-Semashko countries, while the number of physicians increased most substantially among prior-free-market SEE countries (see ). The length of hospital stay was reduced up to 40% in all countries, while the frequency of outpatient visits and inpatient discharges doubled in prior-free-market SEE countries (see ). Overall, the UNDP Human Development Index (HDI) growth was strongest among the prior-free-market SEE countries, followed by the former Yugoslavia and post-Semashko countries (see ).

Most countries have substantially decreased their density of hospitalsCitation15 and primary care facilities, and available hospital beds, with the partial exception of TurkeyCitation16. An under-developed primary care sector with obvious signs of weak capacities is visible in the Post-Semashko countries and the Former Yugoslavia region. The only substantial exceptions from this rule are the cases of Hungary and Bulgaria. Bulgaria also shows a 5-fold growth in only an 8-year time span in the percentage of private inpatient hospital beds. Strong private health sectors existed in prior-free SEE markets even in 1989, and continued to gain market share most remarkably in CyprusCitation17, followed by Greece and Turkey (see ). The frequency of inpatient discharges and outpatient visits decreased substantially as well, as the average duration of hospital admissions in the majority of Former Yugoslavia and post-Semashko countriesCitation18. Interestingly, capacity building in surgical medical specialties gave fruit in terms of almost doubling the frequency of surgical treatments across all countries.

Discussion

Back in 1989, the 14 countries of the SEE region had very different starting points. At that time, rapid transformation towards civil democracies began in former socialist centrally planned markets. Nevertheless, the pace and nature of such advances turned out to be quite unevenCitation19.

To date, most of the SEE region experienced substantial gains in longevity of 4 or more years on average during the past two and a half decades. This success, most prominent in Greece and Cyprus, should be attributed not only to the improved health system responsiveness, but also to the prevailing lifestylesCitation20,Citation21. Former Yugoslavian republics were standing better than Semashko countries in terms of life expectancy at birth as well as WHO estimated life expectancy and after similar gains across all three groups of countries remained well ahead. The fluctuations in adult age mortality were clearly connected with the macroeconomic crisis during the societal transitionCitation22. A causal inter-relationship between political circumstances and human longevity was previously documented in a pan-European study encompassing a century long time horizonCitation23.

An essential demographic phenomenon evolving alongside the SEE transition is the population agingCitation24. Its pace across nation groups could be indirectly assessed from the falling total fertility rates and live birth rates recorded in the past 24 years. Rapid aging is an obvious trend in most countries arising from former Yugoslavia and Post-Semashko nationsCitation25,Citation26. Significant exceptions are Albania and Kosovo, whose second demographic transition ended only recentlyCitation27. Turkey is a distinguished example of the most populous country of the region still on the brink of a 2.1 population replacement fertility level. It has recorded 17 live births per 1,000 population in 2012, which tops the list of all SEE countries. Although it is highly likely that Turkey shall inevitably enter an aging pattern like the majority of Northern hemisphere industrialized nations, it is still not currently the caseCitation28,Citation29. Noted profound demographic changes in all three SEE regions will likely have a backward impact on the overall economy and ultimately on the affordability of medical care for the citizensCitation30.

Improvement in maternal and neonatal outcomes judged according to macro data was most prominent in former Semashko countries, although this fact sometimes was not supported with micro level insights. This was the case in Serbia adopting the perspective of delivering mothers and Albania, where the quality of such care was regarded substandard and more approximate to CIS countries in many areasCitation31,Citation32. Neonatal mortality rates, both real and estimated, decreased substantially throughout the region. Yugoslavia’s republics, Cyprus, and Greece were initially standing better than the Semashko systems and Turkey back in 1989. Undisputed progress, ranging in 2012/1989 ratio terms at least from three to five times, happened mostly due to investments in intensive neonatal care units, capacity build-up, and innovative medical technologies, allowing for improved survival in premature birthsCitation33. Although abortion rates were mostly falling in all three regions they remain the lowest within prior-free SEE followed by former Yugoslavia. The cause of concern should still be the pretty high abortion rates in the Semashko countries, far exceeding the ones in most of the EU. This phenomenon may be interpreted as a consequence of the Russian mortality crisis during the 1990s and was addressed with different success rates as witnessed in examples of Romania and MoldovaCitation34–36.

The prevailing trend in all three regions is downsizing of hospital capacities inherited from the 1980s. As expected, Semashko systems showed a heavily developed network of stationary medical facilities back in 1989, ranging from 2–8 hospitals per 100,000 inhabitants. This same figure in Yugoslav republics was 1–3, while Prior-free SEE with the extreme exception of small sized Cyprus, ranged approximately from 1.5–4 hospitals per 100,000 inhabitantsCitation37. Contemporary hospital density remains relatively high only in Bulgaria (4.7) and Cyprus (10.3), while the vast majority of other countries in all regions converged towards the 1–3 range. The only country recording the opposite trend of building up its hospital network was Turkey (1.6 to 1.9), which is fully justified by the under-development of its network. Turkish positive economic growth for a number of years was used to intensify efforts on provision of equitable access to medical care to the poor and under-served, particularly in rural areasCitation38.

Density of primary healthcare units per 100,000 inhabitants was mostly above 15, with few exceptions back in 1989. Since then countries adopted highly individual policesCitation39. A significant increase of primary care capacities was witnessed in the majority of Semashko systems. The Albanian 20% decrease should be attributed to historical unrest in 1997, when almost one third of national capacities were highly damagedCitation40. Among former Yugoslav republics, Bosnia’s capacities decreased due to civil war in 1991–1995, while other countries noted no significant build up, with bright examples of Croatia and Macedonia. Prior-free SEE recorded no change in Greece and almost doubled network capacities in Turkey.

Hospital beds availability in Semashko countries initially were almost double the ones in Yugoslavia and Prior-free SEE markets. Financial constraints during the 1990s as well as health policy recommendations during the EU accession process influenced serious cuts in disposable hospital bedsCitation41. Two decades after, these numbers are at least one third lower in the post-Semashko region, and at least 15–20% lower in the former Yugoslavia region. Developments across Prior-free SEE were highly heterogeneous, with Greece almost unchanged, Cyprus cutting down its hospital beds to almost one half of historical figures, and, once again, Turkey being the only country in all of the SEE region to expand its capacities by ∼20%. It should be emphasized that Turkish hospital beds density was initially by far the lowest, with only 210 beds per 100,000 population.

The privately owned primary care sector had an almost zero presence in Yugoslavia’s market and more than a symbolic one in Semashko economies. Opposed to these, it was very strong in prior-free SEE markets in 1989, followed by bold national developments in all three countries. This should be explained by commitments of national authoritiesCitation42. On the other side, the first two regions were very unsuccessful in developing national private healthcare sectors. The example of Bulgaria with its 5-fold percentage of private inpatient hospital beds should be attributed to the successes of Bulgarian healthcare reforms since the end of the 1990sCitation43,Citation44.

Physicians numbers per 1,000 inhabitants were of course led by Semashko economies in 1980s. Although these were actually higher then respective figures in most OECD economies for several reasons, these numbers actually go up in all SEE countries except Albania and Moldova. Regardless of high entrance quotes in medical universities and still quite affordable education in the Balkans, these physicians tend to be concentrated in large urban centers due to the availability of job openings and better living standardCitation45. Rural areas remain under-served and experience a serious lack of physicians, while simultaneously there are excess unemployed healthcare professionals in the cities unwilling to move to smaller towns and villagesCitation46. This problem was partially resolved with a variety of governmental policies to stimulate employment and raise physician income, including transfer from salary to capitation based paymentsCitation47. Consequences of this process are evident in bold increases of physician density in Bulgaria, Moldova, Romania, Croatia, Macedonia, Cyprus, Turkey, and Greece, topping the list in absolute terms.

Nursing staff shortages were one of the key obstacles to the quality of outpatient and hospital inpatient care in the Balkans before transition, and it remains the case in many emerging global markets todayCitation48. Literature sources frequently cite an unsatisfactory level of medical care across the region. This might arguably be attributed to a lesser extent to the lack of clinical skills or knowledge of staff and to the simple shortage of manpower to run large facilities with high work load. This is particularly evident in care-demanding clinical branches, such as surgery, and the high rate of hospital acquired wound infections. The insufficient human and capital investment in tertiary hospital care is most obvious in a few high-tech disciplines, such as orthopedics, transplantation surgery, radiation oncology, and interventional radiologyCitation49,Citation50.

The aforementioned weaknesses of SEE national health systems can be witnessed from resource use data. Frequency of inpatient care discharges per 100 inhabitants generally speaking became slightly lower in Semashko countries through the 1990s and 2000s, with the exception of Bulgaria. The Bulgarian case might be explained by consequences of changed financing and management practice within their national health systemCitation51. In contrast, the Yugoslavia region recorded mild growth in hospital admission frequency. Prior-free SEE economies all experienced a substantial increase, with Greece and Turkey as prominent examples. Such practices follow their national policies and might be attributed to the improved access to medical care in the rural areas and among the poor citizensCitation52. Without any significant differentials, all three regions succeeded to shorten duration of hospital stay from almost 2 weeks in 1989 up to 3–7 days per country on average. This can be explained by the fact that many novel medical technologies came to local markets, in the meantime essentially allowing former hospital admissions to be one-day outpatient interventions. This is the case, with 1-day surgery as well as outpatient care becoming the standard way to deal with mental illnesses such as addiction or mood disordersCitation53.

Outpatient physician visits per person per year became generally less common as we are approaching the end of transition in the SEE region. An at least one third decrease in its frequency was reported in the majority of SEE countries, with Hungary and Slovenia virtually unchanged, and the notable exception of Turkey. Turkish outpatient physician visits increased by more than 6-times, which is in line with the overall pace of upward health system transformation in this country.

A promising development in this direction is the growing frequency of inpatient surgical operations, which doubled in Bulgaria and increased by at least 20% in other Semashko countries. Prior-free SEE recorded comparable growth, while data for the former Yugoslavia region are mostly lacking. Turkish authorities once again reported a record-breaking 6-fold increase in only a 15-year time span.

UNDP Human Development Index (HDI) might be regarded as a particularly helpful composite indicator, combining in itself elements of income available, education, and life expectancy. Our observation of HDI trends in these three regions clearly exposes most rapid development of Prior-free SEE economies followed by some Semashko systems. Yugoslavian republics lack official data for most of the 1990s, but their growth of HDI recorded since 2000 was mostly moderate, with the exception of Slovenia. The biggest individual winners of transition in terms of HDI gains were countries which initially had the lowest starting point, such as Turkey and Albania. An exception from this rule is Moldova, which almost remained at its 1990 level. Other Semashko countries exposed an excellent performance in terms of HDI, with Hungary in the lead. This may be attributed to a variety of reasons, including the advanced legislative framework, allowing for evidence-based resource allocation in Hungary prior to most other countries of the regionCitation54. Besides, Hungary performed exceptionally well in increasing overall societal welfare and external investment, which clearly reflected in the healthcare arena.

The transition itself has caused some of the existing social inequalities to worsen furtherCitation55,Citation56. Gaps in access to healthcare among income groups have mostly expanded, and these societies became more stratified. Consequences of these changes for the overall population meant temporarily decreasing longevity and worsened neonatal and maternal health in large parts of Eastern Europe. These inefficiencies of the national health systems were actually curable by adequate policy. Up to date South-Eastern Europe remains a complex myriad of locally diverse healthcare settings. The Balkan pattern of deepening rifts among income groups shaping access to medical careCitation57 is unlike the one described in Western Europe, where such divisions were targeted by successful policies.

On a few occasions it was visible that health system capacities as well as population health developments were not going in the same direction in Turkey and other countries of the region. Causes for such observations should be found in the fact that Turkey back in 1989 was a very young society with its health system significantly lagging behind the ones of Yugoslavia and many Semashko countriesCitation58. The trend of substantial cuts in hospital and primary care facilities capacities, most prominent among the Post-Semashko countries, should be regarded as a long-term gainCitation59. Frequently cited weaknesses of these traditions were excessive availability of poorly managed professional staff and disposable hospital beds, which tended to be under-occupied compared to high-income OECD economies. Regardless of many successes, long-term sustainability of Balkan health reforms, particularly in terms of financing and provision of medical care, will remain a serious challengeCitation60.

Study limitations

Ground evidence for this research was the European Health for All database (HFA-DB) as a data source issued by the WHO Regional Office for Europe. These data were compiled together based on a variety of sources such as WHO/Europe’s programs, partner organizations, UN agencies EUROSTAT, and the OECD. Nevertheless, there has been some criticism raised among academia on the reliability of nationally reported data and estimates, particularly the ones related to workforce parameters in the SEE region. The more ambitious upgraded research effort on the region, providing a bottom-up perspective such as panel surveys of patients and healthcare professionals, might provide deeper insight into the aforementioned issues. The inclusion of scientific papers published in leading local language journals would contribute to the overall picture, but these were out of the scope of this study. Kosovo was excluded from the study due to the fact that it was absent within the official release of HFA-DB during the observed time span. More ambitious statistical analysis on time trends and inter-country differences might be deployed in future studies. Nevertheless, the authors regarded ground descriptive data provided in this paper sufficient to emphasize the key findings.

Conclusion

During two and a half decades of long health reform processes, some transitional SEE countries performed better than others. In terms of gained outcomes in longevity, neonatal and maternal health all three groups of countries showed substantial advances according to macro-level data. Formerly massive hospital centered systems of the Post-Semashko countries and former Yugoslavia republics are clearly reshaped towards more preventive and efficient primary care. Among the prior-free-market SEE countries, which lack experience of profound socioeconomic transition, improvements have also been made, although Turkey exposes deficiencies in neonatal and maternal medical care. From a historical perspective, it seems that these three different healthcare legacies ultimately advanced towards improved longevity, better survival in early childhood, and decreased utilization of hospital services. This might best be explained by long-term positive trends in all regions in terms of overall wellbeing, as expressed by the Human Development Index extrapolation. Different pathways towards common goals create an opportunity for these economies to learn from each other. National policy-makers across the SEE region share a common heritage in healthcare financing and management. This circumstance might enable them to best exploit historical occasions and implement knowledge acquired by surrounding economies coping with similar challenges.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by The Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia through Grant [OI 175014]. Publication of results was not contingent to the Ministry’s censorship or approval.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

There are no relationships to be declared. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

- Semashko NA. Health protection in the USSR. 1st ed. London: Victor Gollancz, 1934

- Saric M, Rodwin VG. The once and future health system in the former Yugoslavia: myths and realities. J Public Health Policy 1993;14:220-37

- Jakovljevic M, Ogura S. Health economics at the crossroads of centuries - from the past to the future. Front Public Health 2016;4:115

- Burazeri G, Brand H, Laaser U. Public health research needs and challenges in transitional countries of South Eastern Europe. Ital J Public Health 2009;6:48-51

- Jakovljevic MB. Resource allocation strategies in Southeastern European health policy. Eur J Health Econ 2013;14:153-9

- Rechel B, McKee M. Health reform in central and eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Lancet 2009;374:1186-95

- Bonilla‐Chacin ME, Murrugarra E, Temourov M. Health care during transition and health systems reform: evidence from the poorest CIS countries. Soc Policy Admin 2005;39:381-408

- Manning N. Diversity and change in pre-accession Central and Eastern Europe since 1989. J Eur Soc Policy 2004;14:211-32

- Tunca H, Yesilyurt F. Hospital efficiency in Turkey: metafrontier analysis. Eur Sci J 2016;12:165-172

- Franco-Giraldo Á. Global health: a Latin American vision. Rev Panam Salud Públic 2016;39:128-36

- Jakovljevic M, Groot W, Souliotis K. Editorial: Health care financing and affordability in the emerging global markets. Front Public Health 2016;4:2

- Labonté R, Schrecker T, Packer C, et al. (Eds) Globalization and health: pathways, evidence and policy. Howick Place, London: Routledge, 2009

- Jakovljevic MB, Vukovic M, Fontanesi J. Life expectancy and health expenditure evolution in Eastern Europe-DiD and DEA analysis. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2016;16:537-46

- Rancic N, Jakovljevic M. Long term health spending alongside population aging in N-11 emerging nations. E Eur Bus Econ J 2016;2:2-26

- Healy J, McKee M. Improving performance within the hospital. Buckingham, Philadelphia: European Observatory on Health Care Systems Series; Open University Press. p 222

- Celik Y, Celik SS, Bulut HD, et al. Inappropriate use of hospital beds: a case study of university hospitals in Turkey. W Hosp Health Serv Offic J Int Hosp Fed 2000;37:6-13

- Petrou P. PHIS Hospital Pharma Report Cyprus 2009. In: 2010, Pharmaceutical Health Information System; Commissioned by the European Commission, Executive Agency for Health and Consumers and the Austrian Federal Ministry of Health ; WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies; http://whocc.goeg.at/Publications/CountryReports; Accessed 30 June 2016 ; Gesundheit Österreich GmbH (GÖG Austrian Public Health Institute) Stubenring 6, 1010 Vienna, Austria

- Mihailovic N, Kocic S, Jakovljevic M. Review of diagnosis-related group-based financing of hospital care. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol 2016;3:1-8

- Jakovljevic M, Getzen TE. Growth of global health spending share in low and middle income countries. Front Pharmacol 2016;7:21

- Gjonça A, Bobak M. Albanian paradox, another example of protective effect of Mediterranean lifestyle? Lancet 1997;350:1815-7

- Christopher P. Traditional Cretan diet and longevity: evidence from the seven countries study. J Nutr Food Sci 2012

- Philipov D, Dorbritz J. Demographic consequences of economic transition in countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Population Studies 39. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, 2003

- Mackenbach JP. Political conditions and life expectancy in Europe, 1900–2008. Soc Sci Med 2013;82:134-46

- Jakovljevic M. The aging of Europe. The unexplored potential. Farmeconomia. Health economics and therapeutic pathways 2015;16:89-92

- Ogura S, Jakovljevic M. Health financing constrained by population aging - an opportunity to learn from Japanese experience. Ser J Exp Clin Res 2014;15:175-81

- Hoff A. Population ageing in Central and Eastern Europe: societal and policy implications. Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2011

- Janiszewska A. Demographic changes in Albania in the light of the theory of the second demographic transition. J Educ Psychol Soc Sci 2013;2:30-6

- Angin Z, Shorter FC. Negotiating reproduction and gender during the fertility decline in Turkey. Soc Sci Med 1998;47:555-64

- Shorter FC, Macura M. Trends in fertility and mortality in Turkey 1935–1975. Washington DC: National Academy Press, 1982

- Jakovljevic M, Laaser U. Population aging from 1950 to 2010 in seventeen transitional countries in the wider region of South Eastern Europe. SEEJPH 2015: published online February 21, 2015, doi:10.12908/SEEJPH-2014-42

- Arsenijevic J, Pavlova M, Groot W. Shortcomings of maternity care in Serbia. Birth 2014;41:14-25

- Tamburlini G, Siupsinskas G, Bacci A. Maternal and neonatal care quality assessment working group. Quality of maternal and neonatal care in Albania, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan: a systematic, standard-based, participatory assessment. PloS one 2011;6:e28763

- Jakovljevic M, Varjacic M, Jankovic SM. Cost‐effectiveness of ritodrine and fenoterol for treatment of preterm labor in a low–middle‐income country: a case study. Value Health 2008;11:149-53

- Tulchinsky TH, Varavikova EA. Addressing the epidemiologic transition in the former Soviet Union: strategies for health system and public health reform in Russia. Am J Public Health 1996; 86:313-20

- Gaetan EK. Curative politics and institutional legacies: the impact of foreign assistance on child welfare and healthcare reform in Romania, 1990–2004, a cutionary tale. Dissertation. University of Maryland; 2005

- Richardson E, Roberts B, Sava V, et al. Health insurance coverage and health care access in Moldova. Health Policy Plan 2012;27:204-12

- Merkouris A, Andreadou A, Athini E, et al. Assessment of patient satisfaction in public hospitals in Cyprus: a descriptive study. Health Sci J 2013;7:28-40

- Ali Jadoo SA, Aljunid SM, Sulku SN, et al. Turkish health system reform from the people’s perspective: a cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:30

- Jakovljevic M, Kanjevac TV, Lazarevic M, et al. Long term dental work force build-up and DMFT-12 improvement in the European region. Front Physiol 2016;7:48

- Hotchkiss DR, Hutchinson PL, Malaj A, et al. Out-of-pocket payments and utilization of health care services in Albania: Evidence from three districts. Health Policy 2005;75:18-39

- Jakovljevic M, Jovanovic M, Lazic Z, et al. Current efforts and proposals to reduce healthcare costs in Serbia. Ser J Exp Clin Res 2011;12:161-3

- Nikolic IA, Maikisch H. Health, Nutrition, and Population Family (HNP) of the World Bank’s Human Development Network. Public-private partnerships and collaboration in the health sector: an overview with case studies from recent European experience. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTECAREGTOPHEANUT/Resources/HNPDiscussionSeriesPPPPaper.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2015

- Atanasova E, Pavlova M, Velickovski R, et al. What have 10 years of health insurance reforms brought about in Bulgaria? Re-appraising the Health Insurance Act of 1998. Health Policy. 2011;102:263-9

- Pavlova M, Groot W, van Merode F. Appraising the financial reform in Bulgarian public health care sector: the health insurance act of 1998. Health Policy 2000;53:185-99

- Brankovic J. Positioning of private higher education institutions in the western Balkans: emulation, differentiation and legitimacy building. In: Brankovic J, Kovačević M, Maassen P, et al, editors. The re-institutionalization of higher education in the western Balkans. The interplay between European ideas, domestic policies, and institutional practices. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2014. p 121-44

- Adhami A, Çela D, Rrumbullaku L, et al. Distribution of primary health care physicians in urban and rural areas of Albania during the period. AMJ 2012;3:50-5

- Schneider P. Provider payment reforms: Lessons from Europe and the US for South Eastern Europe. Enhancing efficiency and equity: challenges and reform opportunities facing health and pension systems in the western Balkans, 44. Health, Nutrition, and Population Family (HNP) of the World Bank’s Human Development Network, 2008. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/HEALTHNUTRITIONANDPOPULATION/Resources/2816271095698140167/BredenkampEnhancingEfficiency&Equity.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2015

- Oulton JA. The global nursing shortage: an overview of issues and actions. Policy Politics Nurs Prac 2006;7:34-9

- Jakovljevic M, Zugic A, Rankovic A, et al. Radiation therapy remains the key cost driver of oncology inpatient treatment. J Med Econ 2015;18:29-36

- Jakovljević M, Ranković A, Rančić N, et al. Radiology services costs and utilization patterns estimates in southeastern Europe – a retrospective analysis from Serbia. Value Health Region Iss 2013;2:218-25

- Pavlova M, Groot W, Van Merode G. Willingness and ability of Bulgarian consumers to pay for improved public health care services. Appl Econ 2004;36:1117-30

- Yardim MS, Cilingiroglu N, Yardim N. Catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment in Turkey. Health Policy 2010;94:26-33

- Jakovljevic M, Jovanovic M, Rancic N, et al. LAT software induced savings on medical costs of alcohol addicts’ care – Results from a matched-pairs case-control study. PLoS One 2014;9:e111931

- Moise AD. Health politics in Hungary and Romania. Dissertation. Central European University, 2014

- Ivančev O, Jovičić M, Milojević T. Income inequality and social policy in Serbia. The wiiw Balkan Observatory. wiiw.ac.at/income-inequality-and-social-policy-in-serbia-dlp-3207.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2015

- Radevic S, Kocic S, Jakovljevic M. Self-assessed health and socioeconomic inequalities in Serbia: data from 2013 National Health Survey. Front Pharmacol 2016;7:140

- Jakovljevic M, Vukovic M, Chen CC, et al. Do health reforms impact cost consciousness of health care professionals? Results from a nation-wide survey in the Balkans. Balkan Med J 2016;33:8-17

- Baris E, Mollahaliloglu S, Aydin S. Healthcare in Turkey: from laggard to leader. BMJ 2011;342:c7456

- Vladescu C, Radulescu S, Cace S. The Romanian healthcare system: between Bismark and Semashko. In G. Shakarishvili, editor. Decentralization in healthcare: Analyses and experiences in Central and Eastern Europe in the 1990s. Budapest, Hungary: Local Government and Public Service Reform Initiative of the Open Society Institute; 2005. p 435-86

- Bredenkamp C, Gragnolati M. Sustainability of healthcare financing in the western Balkans: an overview of progress and challenges. In Policy Research Working Paper 4374. World Bank Publications. http://econ.worldbank.org. Accessed January 5, 2015