Abstract

Objective: Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid; ASA) is commonly used for secondary prevention of cardiovascular (CV) events, but may be associated with gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events, which can reduce adherence. Use of ASA co-therapy with proton pump inhibitors in patients at risk may be suboptimal. PA32540 (Yosprala™) is a coordinated-delivery tablet combining EC-ASA 325 mg and immediate-release omeprazole 40 mg. The objective of this flexible budget impact model was to project the financial consequences of introducing PA32540 325 mg/40 mg to prevent recurrent CV events, while reducing ASA-associated GI events in US adults.

Methods: A Markov Model was employed to estimate health state transitions associated with ASA 75–325 mg, ASA 75–325 mg + generic delayed-release omeprazole 40 mg, PA32540, or clopidogrel 75 mg to prevent recurrent CV events. Health states included ulcers, GI bleeding, CV events, and death. Model inputs included demographics, treatment dosages, treatment costs, adverse GI and CV events, and premature death. Data from peer-reviewed literature and censuses enabled appropriate allocation of CV and GI disease prevalence and mortality. The PA32540 non-adherence rate was conservatively set at 20%. PA32540 market share was set to 50%.

Results: The model projected annual savings of $81.0 million to $190.9 million within 1–5 years after PA32540 introduction to the plan, which included 134,558 members at risk for recurrent CV events. These values translate into savings of $602 (year 5) to $1,419 (year 1) per patient per year, and $81 (year 5) to $191 (year 1) per member per year. These values were robust to variations in parameters under a deterministic sensitivity analysis.

Conclusion: PA32540 use to prevent recurrent CV events was associated with cost reductions in each year examined with the model. From a health plan perspective, PA32540 is likely to have a net overall effect, resulting in significant cost savings.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), including ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, is the leading cause of death worldwideCitation1. Nonetheless, age-adjusted mortality rates from CVD are decreasing, suggesting improved survival in individuals who experience a cardiovascular eventCitation1,Citation2. Among these individuals, secondary events continue to be a challenging problem. In the US, within 6 years after a recognized myocardial infarction, 18% of men and 35% of women will have another heart attack, 7% of men and 6% of women will experience sudden death, and 8% of men and 11% of women will have a strokeCitation3.

Clinical guidelines recommend aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid; ASA) therapy for the prevention of secondary CVD and strokeCitation4–6. Despite the proven benefits of ASA therapy in the secondary prevention of CVD, ASA utilization and adherence remains suboptimalCitation7,Citation8. Poor adherence with low-dose ASA therapy ranged from ∼10% to over 50%, and patient-initiated discontinuation of therapy occurred in up to 30% of patientsCitation9. The causes of ASA discontinuation are often multifactorial; however, side-effects, including gastrointestinal (GI) events, are among the most significant contributorsCitation10–12. Moreover, many studies have shown that discontinuation of ASA therapy following a secondary CV event or stroke may result in significant morbidity and mortalityCitation13–16.

The frequency of ASA discontinuation creates a challenging paradox. Those at risk of a CV event are often directed to take ASA; however, adherence to ASA therapy puts patients at risk of GI side-effects, which increase the risk of discontinuation. Discontinuation of ASA increases the risk of CV events compared to those who continue ASA therapy.

Although historical strategies for reducing the risk of GI complications include the use of lower ASA doses, buffered ASA, and/or enteric-coated (EC)-ASA formulations, these strategies do not appear to reduce the risk of GI bleeding complicationsCitation17–22. Consequently, for patients at risk of upper gastroduodenal adverse events (AEs), gastroprotection should be prescribedCitation17.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the preferred agents for the therapy and prophylaxis of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)- and ASA-associated GI injuryCitation17. Continuous PPI use with ASA therapy is associated with a lower risk of GI ulcers or bleeding compared with intermittent or no PPI use among adults with a high risk of GI eventsCitation23,Citation24.

However, prescribing and adherence to ASA co-therapy with PPIs in patients at risk may be suboptimalCitation25,Citation26. In one study, more than 50% of patients at increased risk for GI events with ASA were not sufficiently treated with concomitant PPI therapyCitation25. Among patients who did receive a concomitant PPI prescription, less than half were adherent in using the PPI, and almost one third did not take their PPI at allCitation26. These data indicate that strategies that provide GI protection while facilitating adherence, such as those that combine ASA and a PPI into a single pill, are needed.

PA32540 (Yosprala™) is a coordinated-delivery tablet combining 325 mg EC-ASA and 40 mg immediate-release omeprazole that has recently been approved by the US Food and Drug AdministrationCitation27. An additional formulation of Yosprala™ (PA8140) contains 81 mg EC-ASA and 40 mg immediate-release omeprazole. In clinical studies, PA32540 significantly reduced the incidence of gastric and/or duodenal ulcers, upper GI symptoms, and discontinuation due to pre-specified upper GI AEs compared to EC-ASA 325 mg aloneCitation28. In this analysis, we projected the financial consequences of introducing PA32540 to prevent recurrent CVD events while reducing ASA-associated GI events in US adults using a flexible budget impact model.

Methods

Model design

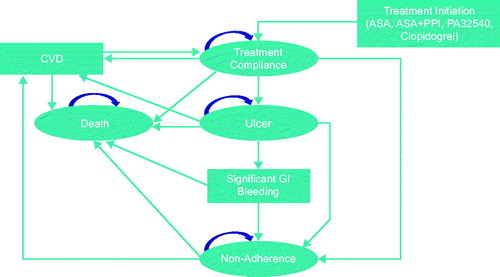

We developed an adjustable Markov Model in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA) to estimate health state transitions associated with ASA 75–325 mg, ASA 75–325 mg + generic delayed-release omeprazole 40 mg in separate formulations, PA32540 at the 325 mg/40 mg dose, or clopidogrel 75 mg to prevent recurrent CVD events.

Model inputs

Relative efficacy, safety, rates of adherence, and discontinuation rates were derived from the relevant peer-reviewed clinical literature, including the results of Phase 3 studies evaluating the impact of PA32540Citation28, and census data. Peer-reviewed literature and census data also enabled appropriate allocation of the cost of treatments (other than PA32540), CVD prevalence, and GI and CVD mortality rates. Health states included ulcers, GI bleeding, CVD events, and death. Model inputs included demographics, treatment dosages, the costs of treatments, adverse GI and CVD events, and premature death. The primary study outcome was the relative annual difference in the cost of care between populations that do and do not use PA32540. End-points included total costs to a 1,000,000-member plan per year, cost per member per year, and cost per patient per year. Total costs included drug costs, the cost of their major side-effects (i.e. the costs of ulcers, GI bleeding, secondary CVD, and their management), and the cost of death.

As described in , patients entered the model with the initiation of either ASA 75–325 mg, ASA 75–325 mg + generic delayed-release omeprazole 40 mg, PA32540, or clopidogrel 75 mg after a CVD event. All patients included in the model initiated one of these treatments. The model accounted for treatment compliance, the potential for a recurrent fatal or non-fatal CVD event, and the potential for developing an ulcer with or without significant GI bleeding. Significant GI bleeding could result in death or non-adherence. The model was developed from a US payer perspective across a 5-year time horizon.

Clinical inputs

Estimates of rates of CVD recurrence, adherence, ulcers, and significant bleeding are summarized in Citation29–34 and Citation11,Citation14,Citation28,Citation35–43. Estimates on the impact of PA32540 were derived from the results of PA32540 Phase 3 studies. PA32540 was evaluated in two identical, 6-month, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, multi-center controlled Phase 3 studies investigating the incidence of gastric ulcers in patients with established CVD or cerebrovascular disease who had been using ASA 325 mg/day for ≥3 months and were at risk for developing ASA-associated ulcers. In both studies, PA32540 was compared with EC-ASA 325 mgCitation28. The design and results of these studies have been published elsewhereCitation28.

Table 1. Population estimates and CVD prevalence estimates in individuals aged 40–79 years.

Table 2. Clinical event probabilities.

The primary efficacy end-point of these studies was the cumulative proportion of subjects who developed endoscopically-determined gastric ulceration (defined as a mucosal break of ≥3 mm in diameter with depth) during the 6 months of treatment. Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) included CVD death, acute coronary syndrome (including non-fatal or fatal myocardial infarction), ischemic stroke, heart failure, and unplanned coronary artery bypass graft or percutaneous coronary intervention. The combined study population included 1049 subjects.

Rates of endoscopic gastric ulcers were significantly lower with PA32540 than with EC-ASA (3.2% vs 8.6%; p < .001). Overall incidences of MACEs were similar between groups (PA32540, 1.7%; EC-ASA, 2.5%). Discontinuation rates due to pre-specified upper GI AEs were 1.5% with PA32540 and 8.2% with EC-ASA (p < .001).

Adherence and cost estimates

The PA32540 non-adherence rate was conservatively set at 20% (vs 1.5% observed in the Phase 3 studies), while the PA32540 market share was set to 50% () of plan members at risk for recurrent CVD events. Inflation and discount rates were set to 3.0%.

Table 3. Estimated patient share per treatment option.

Cost inputs and assumptions are summarized in Citation43,Citation44. For ASA 75–325 mg, ASA 75–325 mg + generic delayed-release omeprazole 40 mg, or clopidogrel 75 mg, costs were obtained from publicly available pricing databases. The price of PA32540 was assumed to be a wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) of $150 per 30 days. Costs related to ulcers, GI bleeding, other side-effects, CVD events, and death were estimated from the literature ()Citation43,Citation45–48. All monetary values used in this analysis were adjusted for inflation and reported in 2015 US dollars.

Table 4. Dosing, cost input, and assumptions.

Table 5. Treatment-associated cost inputs and assumptions.

Sensitivity analysis

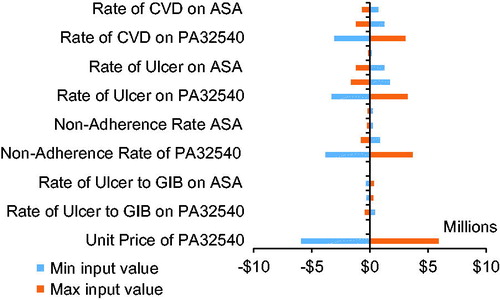

Two-way sensitivity analyses were performed by varying the rates of recurrent CVD events, ulcers, GI bleeding from ulcers, and non-adherence by 5% in either direction and by varying the unit price of PA32540 by 10% in either direction.

Results

It was estimated that, in a plan including 1,000,000 patients, 134,558 adult patients were at risk for secondary CVD events. Among adults aged 40–79 years, 44,221 males and 45,101 females were at risk for secondary CVD events.

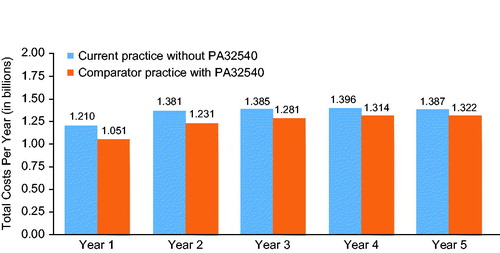

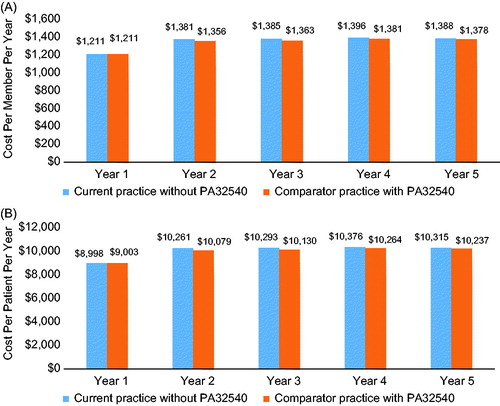

The model projected annual savings of $81.0 million to $190.9 million within 1–5 years after PA32540 introduction to the plan (). At year 1, total costs were $1.02 billion after the introduction of PA32540 and $1.21 billion with current practice without PA32540. By year 5, total costs were $1.31 billion with PA32540 and $1.39 billion without PA32540. These values translate into savings of $81 (year 5) to $191 (year 1) per plan member per year () and $602 (year 5) to $1,419 (year 1) per patient per year (). Savings were similar for men and women. Annual savings ranged from $26.5 billion (year 5) to $62.7 billion (year 1) for men and $27.0 billion to $64.0 billion for women.

Figure 2. Total costs per year with and without PA32540. Costs shown here are to a plan with 1,000,000 members.

Figure 3. Budget impact of PA32540: annual cost per member per year (A) and annual cost per patient per year (B).

These values were robust and resistant to variations in rates of CVD, ulcers, bleeding, and the cost of PA32540 under a deterministic sensitivity analysis ().

Discussion and conclusions

Despite the significant benefits of ASA therapy in the prevention of secondary CVD events, adherence to ASA is sub-optimal. Rates of non-adherence to ASA therapy have ranged from 8–28%Citation12. Adherence rates decline in the presence of GI symptoms.

While PPIs reduce the rates of GI AEs with ASA and have been shown to be cost-effective in patients using ASA for secondary CVD preventionCitation43,Citation49,Citation50, these agents are not routinely prescribed when ASA is initiated in patients at riskCitation51. When PPIs are prescribed, evidence suggests that less than half of patients are adherent to daily PPI useCitation26. PA32540 may improve adherence by reducing the complexity of the regimen and by reducing the GI AEs observed with ASA alone.

Results from two randomized, double-blind, 6-month Phase 3 studies have confirmed the efficacy and safety of PA32540 in patients with established CVD or cerebrovascular disease who had used ASA 325 mg/day for the previous 3 monthsCitation28,Citation52. A pooled analysis of these trials confirmed that PA32540, compared to EC-ASA alone, significantly reduced the incidence of endoscopically determined gastric ulcers (3.2% vs 8.6%; p < .001), the combined incidence of gastric and duodenal ulcers (3.4% vs 11.6%; p < .001), and per a post-hoc analysis, the incidence of new or worsening erosive esophagitis (2.1% vs 15.8%; p < .001). In addition, significantly fewer subjects assigned to PA32540 discontinued the study due to pre-specified upper GI AEs compared to EC-ASA alone. At month 6, 8.2% of subjects assigned to EC-ASA alone discontinued the study due to pre-specified upper GI AEs, compared to 1.5% of subjects assigned to PA32540 (p < .001). Overall rates of secondary major adverse CV events were 2.5% with EC-ASA and 1.7% with PA32540 (p = NS).

Our budget impact model suggests that the use of PA32540 may be cost-effective. Our analysis demonstrated that substantial cost savings of up to $1,419 per patient per year could be achieved with the use of PA32540 in patients at risk for ASA-related upper GI adverse events, for a total of up to $190.9 million for a plan with 1,000,000 members within 1–5 years after the introduction of PA32540. Per member savings of up to $191 per year could also be attained with PA32540. Moreover, as the risk of AEs such as GI bleeding may not appreciably differ with different dosesCitation21, these results could be extrapolated to patients using either the 81-mg or the 325-mg EC-ASA dose.

As with any predictive modeling study, this analysis has several limitations. First, the reliability of the estimates of clinical event rates incorporated in the model depends on the relevance and reliability of the existing data. PA32540 has not been evaluated in a real-world setting, and the outcomes observed in the Phase 3 clinical trial program with PA32540 may not be generalizable to the overall population.

In summary, this model demonstrated that the use of PA32540 to prevent recurrent CVD events was associated with cost reductions in each year examined. From a health plan perspective, PA32540 is likely to have a net overall effect that is budget saving.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funded by Aralez Pharmaceuticals R&D Inc.

Declaration of financial or other interests

YH and WZ are WG Group employees. JGF, DS, and JPT are Aralez employees and stock shareholders. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

These findings have been presented at the AMCP Nexus Conference in National Harbor, Maryland, on October 3–6, 2016.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nicole Cooper of MedVal Scientific Information Services, LLC, for medical writing and editorial assistance, which was funded by Aralez Pharmaceuticals R&D Inc. This manuscript was prepared according to the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals’ ‘Good Publication Practice for Communicating Company-Sponsored Medical Research: The GPP3 Guidelines’.

Additional information

Funding

References

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1459-544

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;133:e38-360

- Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2006;113:e85-e151

- Smith SC Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 2011;124:2458-73

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;134:e123-e155

- Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011;42:227-76

- Stafford RS, Monti V, Ma J. Underutilization of aspirin persists in US ambulatory care for the secondary and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. PLoS Med 2005;2:e353

- Mainous AG, Tanner RJ, Shorr RI, et al. Use of aspirin for primary and secondary cardiovascular disease prevention in the United States, 2011–2012. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e000989

- Herlitz J, Toth PP, Naesdal J. Low-dose aspirin therapy for cardiovascular prevention: quantification and consequences of poor compliance or discontinuation. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2010;10:125-41

- Moberg C, Naesdal J, Svedberg LE, et al. Impact of gastrointestinal problems on adherence to low-dose acetylsalicylic acid: a quantitative study in patients with cardiovascular risk. Patient 2011;4:103-13

- Pratt S, Thompson VJ, Elkin EP, et al. The impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms on nonadherence to, and discontinuation of, low-dose acetylsalicylic acid in patients with cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2010;10:281-8

- Duffy D, Kelly E, Trang A, et al. Aspirin for cardioprotection and strategies to improve patient adherence. Postgrad Med 2014;126:18-28

- Ho PM, Spertus JA, Masoudi FA, et al. Impact of medication therapy discontinuation on mortality after myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1842-7

- Biondi-Zoccai GGL, Lotrionte M, Agostoni P, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the hazards of discontinuing or not adhering to aspirin among 50,279 patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2006;27:2667-74

- Garcia Rodriguez LA, Cea Soriano L, Hill C, et al. Increased risk of stroke after discontinuation of acetylsalicylic acid: a UK primary care study. Neurology 2011;76:740-6

- Derogar M, Sandblom G, Lundell L, et al. Discontinuation of low-dose aspirin therapy after peptic ulcer bleeding increases risk of death and acute cardiovascular events. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:38-42

- Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS, et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation 2008;118:1894-909

- de Abajo FJ, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation associated with low-dose aspirin as plain and enteric-coated formulations. BMC Clin Pharmacol 2001;1:1

- Garcia Rodriguez LA, Hernandez-Diaz S, de Abajo FJ. Association between aspirin and upper gastrointestinal complications: systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001;52:563-71

- Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Jurgelon JM, et al. Risk of aspirin-associated major upper-gastrointestinal bleeding with enteric-coated or buffered product. Lancet 1996;348:1413-16

- Derry S, Loke YK. Risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage with long term use of aspirin: meta-analysis. BMJ 2000;321:1183-7

- Valkhoff VE, Sturkenboom MC, Hill C, et al. Low-dose acetylsalicylic acid use and the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials and observational studies. Can J Gastroenterol 2013;27:159-67

- Hedberg J, Sundstrom J, Thuresson M, et al. Low-dose acetylsalicylic acid and gastrointestinal ulcers or bleeding—a cohort study of the effects of proton pump inhibitor use patterns. J Intern Med 2013;274:371-80

- Martin-Merino E, Johansson S, Bueno H, et al. Discontinuation of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid therapy in UK primary care: incidence and predictors in patients with cardiovascular disease. Pragmat Obs Res 2012;3:1-9

- de Jong HJ, Korevaar JC, van Dijk L, et al. Suboptimal prescribing of proton-pump inhibitors in low-dose aspirin users: a cohort study in primary care. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003044

- Sorstadius E, Herlitz J, Naucler E, et al. Prescription rates and adherence to the proton pump inhibitor therapy among patients who require low-dose acetylsalicylic acid for cardiovascular prevention [abstract]. Value Health 2010;13:A372

- Miner PB Jr, Fort JG, Zhang Y. Intragastric acidity and omeprazole exposure during dosing with either PA32540 (enteric-coated aspirin 325 mg + immediate-release omeprazole 40 mg) or enteric-coated aspirin 325 mg + enteric-coated omeprazole 40 mg - a randomised, phase 1, crossover study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:62-71

- Whellan DJ, Goldstein JL, Cryer BL, et al. PA32540 (a coordinated-delivery tablet of enteric-coated aspirin 325 mg and immediate-release omeprazole 40 mg) versus enteric-coated aspirin 325 mg alone in subjects at risk for aspirin-associated gastric ulcers: results of two 6-month, phase 3 studies. Am Heart J 2014;168:495-502

- Blackwell DL, Lucas JW, Clarke TC. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: national health interview survey, 2012. Vital Health Stat 2014;10:1-161

- US Census Bureau (Population Division). Table 9. Projections of the population by sex and age for the United States: 2015 to 2060 [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Census Bureau (Population Division). 2014; http://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/summarytables.html. Accessed August 3, 2016

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015;131:e29-322

- Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, et al. Deaths: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2016;64:1-119

- Abougergi MS, Travis AC, Saltzman JR. The in-hospital mortality rate for upper GI hemorrhage has decreased over 2 decades in the United States: a nationwide analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:882-8

- Ruigomez A, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Hasselgren G, et al. Overall mortality among patients surviving an episode of peptic ulcer bleeding. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:130-3

- Carlton R, Clark R, Regan TS. Burden of secondary cardiovascular disease in commercial and Medicare patients: a managed care perspective. J Managed Care Pharm 2013;19:153-4

- Nichols GA, Bell TJ, Pedula KL, et al. Medical care costs among patients with established cardiovascular disease. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:e86-e93

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet 1996;348:1329-39

- Herlitz J, Sorstadius E, Naucler E, et al. Prescription rates and adherence to proton pump inhibitor therapy among patients who require low-dose acetylsalicylic acid for cardiovascular prevention [abstract]. Eur Heart J 2010;31:675-6

- Ng FH, Wong SY, Kng CPL, et al. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding during anti-platelet therapy. Hong Kong Med Diary 2008;13:27-9

- Yeomans ND, Lanas AI, Talley NJ, et al. Prevalence and incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers during treatment with vascular protective doses of aspirin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;22:795-801

- Khuroo MS, Yattoo GN, Javid G, et al. A comparison of omeprazole and placebo for bleeding peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1054-8

- Wilcox CM, Spenney JG. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in medical patients: who, what, and how much? Am J Gastroenterol 1988;83:1199-211

- Saini SD, Fendrick AM, Scheiman JM. Cost-effectiveness analysis: cardiovascular benefits of proton pump inhibitor co-therapy in patients using aspirin for secondary prevention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:243-51

- Gaspoz JM, Coxson PG, Goldman PA, et al. Cost effectiveness of aspirin, clopidogrel, or both for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1800-6

- Bi WP, Man HB, Man MQ. Efficacy and safety of herbal medicines in treating gastric ulcer: a review. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:17020-8

- Fashner J, Gitu AC. Diagnosis and treatment of peptic ulcer disease and H. pylori infection. Am Fam Physician 2015;91:236-42

- Bonafede MM, Johnson BH, Richhariya A, et al. Medical costs associated with cardiovascular events among high-risk patients with hyperlipidemia. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2015;7:337-45

- Stranges E, Russo CA, Friedman B. Procedures with the most rapidly increasing hospital costs, 2004–2007: Statistical Brief #82 [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2009. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb82.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016

- Takabayashi N, Murata K, Tanaka S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of proton pump inhibitor co-therapy in patients taking aspirin for secondary prevention of ischemic stroke. Pharmacoeconomics 2015;33:1091-100

- de Groot NL, van Haalen HG, Spiegel BM, et al. Gastroprotection in low-dose aspirin users for primary and secondary prevention of ACS: results of a cost-effectiveness analysis including compliance. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2013;27:341-57

- Elnachef N, Scheiman JM, Fendrick AM, et al. Changing perceptions and practices regarding aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and cyclooxygenase-2 selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs among US primary care providers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:1249-58

- Goldstein JL, Cryer BL, Lanas A, et al. PA32540 (enteric-coated aspirin 325 mg + immediate-release omeprazole 40 mg) is associated with significantly fewer gastric ulcers and significantly less endoscopic erosive esophagitis than enteric-coated aspirin (EC-ASA) alone: results of two phase 3 studies. Poster session [P608] presented at 77th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology; Las Vegas, NV; October 22, 2012