Abstract

Background: The β3-adrenoceptor agonist, mirabegron, and antimuscarinic agents provide similar efficacy for the treatment of overactive bladder (OAB), but mirabegron appears to be associated with better persistence, perhaps due to an absence of anticholinergic side-effects. This study estimated the expected costs associated with the management of OAB in Canada from a societal perspective by utilizing real-world evidence.

Methods: An economic model with monthly cycles and a 1-year time horizon was developed to depict a treatment pathway for a hypothetical cohort of 100 patients with OAB. At model entry, patients receive mirabegron or an antimuscarinic. Patients who do not persist may switch treatment, undergo a minimally invasive procedure, or remain symptomatic (uncontrolled). The model includes direct costs (e.g. physician visits) and indirect costs (e.g. lost productivity). A one-way univariate sensitivity analysis assessed a ±20% variation in each of the key model inputs.

Results: At 1 year, a greater proportion of patients persisted on treatment with mirabegron compared with antimuscarinics (33% vs 15–23%), and a smaller proportion switched treatment (17% vs 20–22%). The number of healthcare visits (292 vs 299–304), pads used (74,098 vs 77,878–81,669), and work hours lost (4,497 vs 5,372–6,249) were all lower for mirabegron vs antimuscarinics. The estimated total annual cost of treatment per patient with mirabegron was $2,127.46 Canadian dollars (CAD) ($5.82 CAD/day) compared with $2,150.20–$2,496.69 CAD ($5.89–$6.84 CAD/day) for antimuscarinics. The one-way sensitivity analysis indicated the results are robust.

Conclusions: Improved persistence observed in routine clinical practice with mirabegron appears to translate into benefits of reduced healthcare resource use, and lower direct and indirect costs of treatment compared with antimuscarinics. Overall, these data suggest that mirabegron may offer clinical and economic benefits for the management of patients with OAB in Canada.

Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a chronic, age-related disorder with a clinically significant negative impact on health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) and patient daily activities, which results in substantial economic burden from both patient and societal perspectivesCitation1–5. It is characterized by the symptoms of urinary urgency, with or without urinary incontinence, usually with frequency or nocturiaCitation6. Among these symptoms, urgency urinary incontinence—which is present in approximately one-third of OAB cases—has the greatest negative impact on HRQoL and productivity, and is associated with significant healthcare utilizationCitation1,Citation2,Citation7. The overall prevalence of OAB was reported to be 11.8% in five countries including CanadaCitation8, and similar data (13.9–18.1%) have been reported in Canadian-specific analysesCitation9.

Oral antimuscarinic agents, e.g. solifenacin, tolterodine, and oxybutynin, and the β3-adrenoceptor agonist, mirabegron, represent the main therapeutic options for the management of OAB following lifestyle/behavioral modificationsCitation10–12. Whilst mirabegron is the only approved β3-adrenoceptor agonist, there are several antimuscarinic agents which may differ in their efficacy and tolerability profiles, due to differences in factors, including muscarinic receptor affinity, lipid solubility, and formulationCitation11. Antimuscarinics and mirabegron have comparable efficacy in reducing the frequency of micturition, incontinence, and urgency urinary incontinence episodes in OABCitation13; however, they have distinct tolerability profiles. Mirabegron use is not associated with bothersome anticholinergic side-effects, such as dry mouth and constipation; these side-effects are observed at a frequency comparable to placeboCitation14,Citation15.

Systematic literature reviews have reported that antimuscarinic agents are associated with low rates of persistenceCitation16,Citation17, and up to 83% of patients discontinue treatment within the first 30 days of treatmentCitation16,Citation17. Reasons cited for discontinuation include unmet treatment expectations and/or tolerabilityCitation18, and there are concerns about the balance between the efficacy and tolerability of these agentsCitation16. A recently reported study of clinical practice in OAB using retrospective claims from a Canadian Private Drug Plan database indicated that, early after introduction, mirabegron was associated with significantly greater persistence rates than five common antimuscarinic agentsCitation19. In this study, patients who were experienced in taking medication for OAB had a median of 299 days on mirabegron, compared with a range of 96–242 days for the antimuscarinics. For treatment-naïve patients, the median number of days was 196 vs 70–100 days, respectivelyCitation19. The reasons underlying the improved persistence rates were not investigated, but may be due to the lower incidence of bothersome anticholinergic adverse events or perception of treatment benefitCitation19.

OAB has a high economic burden to the patient and societyCitation20–22. Estimates of the economic burden of a disease often include three types of costs: direct, indirect, and/or intangible. Direct medical costs associated with OAB may include medical consultations, diagnostic testing, prescriptions, and incontinence pads, while indirect costs include items such as caregiver salaries or nursing home fees, absenteeism/presenteeism, and the costs of OAB-related consequences (e.g. falls or fractures, infections, and psychological manifestations). Intangible costs, which may include those associated with pain or suffering (e.g. HRQoL impact), are difficult to estimate and are often excluded from economic analysesCitation20. A population-based study reported an estimated annual direct cost of €379 million for an estimated 2.2 million individuals with OAB in Canada (based on 2005 cost data)Citation21. Additional estimated costs in Canada attributable to OAB were €385 million/year for nursing home costs and €65 million/year due to absenteeism (in those aged <65 years old)Citation21. An understanding of the total economic burden of OAB is likely to be beneficial in the allocation of healthcare resources.

The aim of this current analysis was to evaluate, from a societal perspective, the clinical and economic impact of initiating treatment with mirabegron compared with antimuscarinic agents in the treatment of adult patients with OAB in Canada. To achieve this, an economic model was developed that reflected treatment persistence and measured costs incurred by the Canadian healthcare system and those attributed to lost productivity.

Materials and methods

Model overview

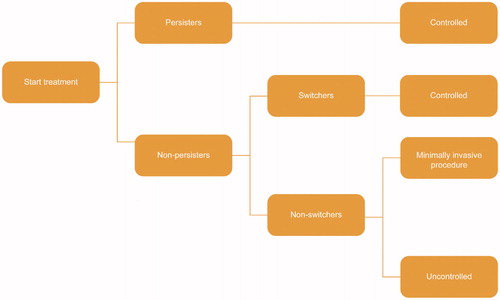

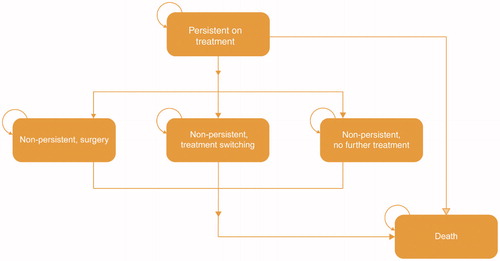

An economic model was developed in Microsoft Excel 2010, based on a simplified treatment pathway and a monthly cycle length, for a hypothetical cohort of 100 patients suitable for treatment with pharmacotherapy over a 1-year timeframe (). Costs evaluated include those incurred by the Canadian healthcare system and those resulting from lost productivity. The primary outcomes are the total annual costs for the whole cohort and total costs per patient per day.

Treatment pathway

At model entry, patients receive treatment with daily regimens of mirabegron 25/50 mg (branded), solifenacin 5/10 mg (branded/generic), fesoterodine 4/8 mg (branded), oxybutynin extended release (ER) 5 mg (generic), oxybutynin immediate release (IR) 10 mg (generic), tolterodine ER 4 mg (branded/generic) or tolterodine IR 2/4 mg (branded/generic). Patients enter the model in the ‘persistent on treatment’ health state. At the end of each cycle, patients can remain persistent (i.e. they have adequate symptom control), discontinue initial treatment and switch to a second-line oral therapy, undergo a minimally invasive procedure (onabotulinumtoxinA [onabotA] injection or sacral nerve stimulation [SNS]), cease treatment altogether, or die (). It is assumed that switching to a second-line treatment or a minimally invasive procedure both lead to symptom control until the end of the 1-year time horizon. In contrast, discontinuation of treatment is assumed to lead to uncontrolled symptoms and a probability of OAB-related co-morbidities (urinary tract infection [UTI] and depression).

Model inputs

Assumptions

Several assumptions are made in an attempt to replicate clinical practice in Canada (Supplementary Table 1).

Transition probabilities

The health state transition probabilities are applied in each model cycle (Supplementary Table 2). The transition probabilities are assumed to be constant over the 1-year time horizon.

Clinical inputs

Clinical inputs are detailed in . The probability of treatment switching (26.06%) was sourced from two recently published cost-effectiveness analyses of pharmacotherapy in OABCitation23,Citation24. Real-world treatment persistence data were derived from a non-interventional study of retrospective prescription claims data within a Canadian National Private Drug Plan database. The study included adults aged ≥18 years who received a prescription for an OAB drug between April–September 2013 and were followed for 1 yearCitation19. The model assumes 50% of those who undergo a minimally invasive procedure receive onabotA injection, and 50% receive sacral nerve stimulation (as there are currently no data to support this). These surgical strategies are recommended treatment options following treatment with oral pharmacotherapies in CanadaCitation25 and the USCitation10. The proportion of patients with incontinence (60%) was used for the estimation of pad useCitation26, which assumed 2.5 pads for patients persistent on treatment (i.e. initial or second-line pharmacotherapy) and 5.5 pads for patients non-persistent on treatment (i.e. no treatment or minimally invasive procedure)Citation27. The monthly probability of mortality in this study was calculated from the mortality rate of the general population in CanadaCitation28.

Table 1. Clinical inputs included in the model.

Costs and resource utilization

Direct costs include daily drug acquisition costs (acquisition costs sourced from the Ontario Drug Benefit FormularyCitation29; dosing details sourced from the British National FormularyCitation30); cost of healthcare visits (one general practitioner [GP] visit for treatment initiation/switch and 1.5 specialist visits for treatment switch)Citation24,Citation29; cost of incontinence padsCitation31; costs associated with the management of comorbidities (UTI and depression)Citation21,Citation32; and minimally invasive procedure costsCitation24,Citation32 (). Second-line treatment costs are applied as a weighted cost based on the market share of OAB treatments in CanadaCitation33.

Table 2. Cost inputs included in the model.

Indirect costs comprise productivity loss (number of work hours lost) only for patients who are employed, non-persistent on treatment, and have uncontrolled symptoms. It is assumed that 34.7% of the patients are employed for an average of 40 h/week and there is a 21% decrease in hours workedCitation34. An average hourly wage of $26.30 Canadian dollars (CAD) is based on adults aged ≥55 yearsCitation35. All cost inputs are based on 2015 prices and expressed in CAD. Where 2015 costs were not available, they were inflated to 2015 values using the Canadian consumer price indexCitation32.

Deterministic sensitivity analysis

A one-way univariate sensitivity analysis was performed to determine the robustness of the model results for a comparison of mirabegron vs solifenacin 5/10 mg. A standard ±20% variation in each of the key model inputs was assessed individually, whilst allowing no changes in the other parameters. The analysis assessed the incremental cost per patient/day. The results were presented in a tornado diagram.

Results

Clinical outcomes

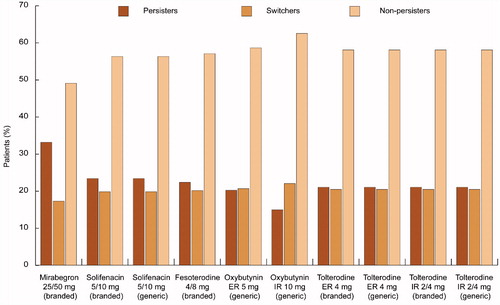

In this analysis, a greater proportion of patients persisted on treatment with mirabegron 25/50 mg compared with antimuscarinics (33% vs range, 15–23%, respectively) and a smaller proportion of patients switched treatment from mirabegron 25/50 mg (17% vs 20–22% with antimuscarinics) or discontinued treatment at 1 year ().

Figure 3. Patient disposition at 1 year for each treatment (100 patients).ER: Extended release; IR: Immediate release.

The number of healthcare visits over 1 year for the total cohort was lower for patients using mirabegron 25/50 mg (117 GP visits and 175 specialist visits, respectively) than for those using antimuscarinics (120–122 GP visits and 179–183 specialist visits) (). Total pad use at 1 year for the 100 patients was also lower with mirabegron compared with the antimuscarinics (74,098 vs 77,878–81,669, respectively) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 3. Healthcare resource use over 1 year (per 100 patients).

Economic outcomes

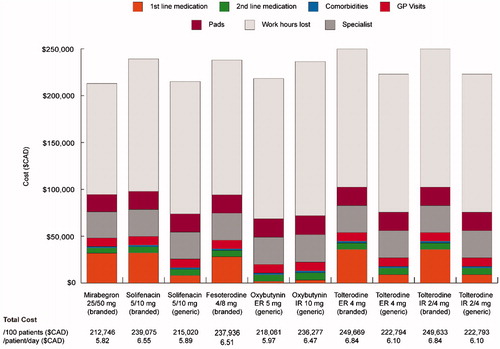

The estimated total drug costs were higher for mirabegron 25/50 mg ($37,424 CAD/year [$102.46 CAD/day]) compared with antimuscarinics, with the exception of branded preparations of solifenacin 5/10 mg ($38,709 CAD/year [daily cost saving $3.52 CAD]), tolterodine IR 2/4 mg ($42,747 CAD/year [daily cost saving $14.57 CAD]), and tolterodine ER 4 mg ($42,753 CAD/year [daily cost saving $14.59 CAD]) (). Mirabegron had the lowest costs for second-line treatment ($5,556 CAD) compared with all antimuscarinics ($6,636–$7,719). Costs related to comorbidities, GP and specialist visits, surgeries, and pad use were all lower for mirabegron compared with antimuscarinics (). In contrast, oxybutynin IR 10 mg had the highest costs for these five resource use types. The greatest difference in the specific resources was observed for pad use ($18,487 CAD for mirabegron vs $19,431–$20,376 CAD for antimuscarinics).

Table 4. Direct costs over 1 year (per 100 patients).

Based on the assumption that non-persistent patients who are uncontrolled have a decrease in work hours, the increased persistence with mirabegron translated into a lower number of total work hours lost (4,497 vs 5,372–6,249) and lower total cost of lost productivity at 1-year ($118,283 CAD vs $141,280–$164,341 CAD) compared with antimuscarinics (for proportion of patients assumed to be of working age and in employment).

The total cost of treatment for 100 patients with mirabegron was estimated to be $212,746 CAD/year, which equates to $5.82 CAD/patient/day. Comparative costs for treatment with antimuscarinics ranged from $215,020 CAD/year ($5.89 CAD/day) with solifenacin 5/10 mg (generic) to $249,669 CAD/year ($6.84 CAD/day) with tolterodine ER 4 mg (branded) (). The incremental cost per patient persistent on treatment for those receiving mirabegron vs antimuscarinics varied between –$233 CAD (solifenacin 5 mg [generic]) and −$3,050 CAD (tolterodine ER 4 mg [branded]). The incremental cost per patient switching treatment varied between $894 CAD (solifenacin 5/10 mg [generic]) and $11,702 CAD (tolterodine ER 4 mg [branded]).

Sensitivity analysis

The results were most sensitive to persistence at 1 year for mirabegron 25/50 mg and solifenacin 5/10 mg (generic) (). In contrast, varying the probability of a minimally invasive procedure or percentage of patients switching treatments had minimal impact on costs/resource use. Sensitivity analysis results are only presented for mirabegron vs solifenacin (generic), as the key drivers are the same in all comparisons.

Discussion

OAB results in significant burden, both in terms of the impact on patients’ daily activitiesCitation2,Citation7 and HRQoLCitation2–4, and also in terms of its economic burden from both a patient and a societal perspectiveCitation21,Citation36. Antimuscarinics reduce the frequency of micturition, urgency, and urgency urinary incontinence episodes in OAB, but treatment persistence with these therapies remains a challengeCitation37,Citation38, with unmet treatment expectations and side-effects most frequently cited as reasons for treatment discontinuationCitation18,Citation39–42. The rates of discontinuation with antimuscarinics appear to be higher than those of medications used for other common chronic conditions such as cardiovascular, oral antidiabetic, and oral osteoporosis therapiesCitation43.

Real-world evidence suggests that mirabegron provides better rates of persistence compared with antimuscarinics in routine clinical practice in CanadaCitation19. It is speculated that the difference in tolerability profiles combined with the demonstrated efficacy and HRQoL benefits of mirabegron are contributing factors to this improved persistenceCitation19,Citation44. The results of our analysis in patients with OAB suggest that this improvement in persistence translates into fewer patients switching treatment and a reduced demand for healthcare resources (e.g. pads and GP and specialist visits). Furthermore, the improved persistence with mirabegron leads to annual cost savings in the form of direct (e.g. pad use) and indirect costs (i.e. lost productivity) compared with antimuscarinics. Of note, results of sensitivity analyses indicate that 1-year persistence on treatment is the key driver of the results.

A recent real-world evidence study reported that patients with OAB treated with antimuscarinics had an increased risk of fall/fractures and depression/anxiety, and increased healthcare utilization (hospital admissions, visits, diagnostic tests, and prescriptions) compared with individuals without OABCitation22. Our current analysis showed that indirect costs (for all treatments)—comprising lost productivity—account for more than half of the total costs. These results highlight the importance of providing treatments that can support symptom control and persistence on treatment, which subsequently improve daily activities, HRQoL, and minimize lost productivity.

Our analysis supports other findings that suggest improved treatment persistence in OAB and other conditions such as hypertension and type-2 diabetes, is associated with improved outcomesCitation45,Citation46 and reduced resource use/costsCitation47,Citation48. Additionally, some studies have reported that mirabegron provides a cost-effective treatment option in the UK, Canada, and the US compared with commonly prescribed antimuscarinicsCitation23,Citation24,Citation49,Citation50. Another study reported that a sequence consisting of two low-cost generic agents plus a third-line branded agent was less effective with similar total costs (i.e. not necessarily more cost-effective) than a sequence of three branded drugs; the results were primarily driven by a difference in efficacy/tolerability balance, leading to improved symptom control and persistenceCitation27. Our analysis was not designed to elucidate the reasons for discontinuation of treatment in OAB, but further research is required to provide patients and physicians with the knowledge and tools to help effectively manage this condition.

When interpreting the findings of this study, it is important to consider the strengths and limitations of the model. It is notable that the model uses real-world persistence data based on retrospective claims analysis, but does not include any direct clinical data for estimates of efficacy, tolerability, or HRQoL. As such, all key patient perspectives are not fully captured. In particular, pads account for ∼10% of the total costs, but the model assumes that pads were reimbursed. This is not common practice in Canada, where patients pay out of pocket. Where costs for pads are reimbursed, savings will be made to personal, public, and private provider budgets. This and other assumptions applied to the model will likely have influenced the findings, and may not be valid in different countries and populations. The model could, however, be adapted for use with other country-specific data. The comparators included in the analysis were based on the availability of those that had real-world persistence data; this resulted in the exclusion of other antimuscarinics that are available in Canada (e.g. darifenacin and trospium chloride). Similarly, the time horizon of 1 year is aligned with the availability of real-world persistence data in Canada, but, as OAB is for many a chronic disease, the current model is unable to estimate the long-term impact of OAB. This analysis estimates the economic impact of treatment for OAB, but further research is required to generate additional real-word evidence to validate the current conclusions.

Conclusion

Findings from this analysis indicate that improved persistence observed with mirabegron is associated with reduced healthcare resource use and lower total costs for the treatment of patients with OAB in Canada compared with antimuscarinics. These findings suggest that mirabegron may offer clinical and economic benefits for the management of OAB, which are important considerations when selecting the optimal drug for patients requiring treatment. The model can be adapted for use with other sources of real-world data, and it will be of interest to establish whether the benefits observed in our study are also observed in other patient populations.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Astellas Pharma Europe Ltd. PAREXEL Access Consulting received consulting fees from Astellas to participate in this economic analysis.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

AW reports grants and personal fees from Astellas Pharma Inc, Duchesnay (Canada), Pfizer Corp, and SCA AB; JN, ZH, and BR are employees of Astellas Pharma Inc; CM and MB report consultancy fees from Astellas Pharma Inc; FF reports a grant from Astellas Pharma Inc. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental_Material.docx

Download MS Word (527.1 KB)Acknowledgments

Medical writing support, provided by Tyrone Daniel of Bioscript Medical, was funded by Astellas Pharma Inc.

References

- Tang DH, Colayco DC, Khalaf KM, et al. Impact of urinary incontinence on healthcare resource utilization, health-related quality of life and productivity in patients with overactive bladder. BJU Int 2014;113:484-91

- Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW, et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J Urol 2003;20:327-36

- Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, et al. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int 2008;101:1388-95

- Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Kopp ZS, et al. The impact of overactive bladder on mental health, work productivity and health-related quality of life in the UK and Sweden: results from EpiLUTS. BJU Int 2011;108:1459-71

- Coyne KS, Wein A, Nicholson S, et al. Economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence in the United States: a systematic review. J Manag Care Pharm 2014;20:130-40

- Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 2002;21:167-78

- Nicolson P, Kopp Z, Chapple CR, et al. It’s just the worry about not being able to control it! A qualitative study of living with overactive bladder. Br J Health Psychol 2008;13:343-59

- Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol 2006;50:1306-14

- Herschorn S, Gajewski J, Schulz J, et al. A population-based study of urinary symptoms and incontinence: the Canadian Urinary Bladder Survey. BJU Int 2008;101:52-8

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Faraday M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment. J Urol 2015;193:1572-80

- Lucas MG, Bedretdinova D, Berghmans LC, et al. Guidelines on urinary incontinence. European Association of Urology. http://uroweb.org/individual-guidelines/non-oncology-guidelines. Accessed August 22, 2016

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2016 Common Drug Review: Mirabegron. 2016. https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/cdr/complete/cdr_complete_SR0363_Myrbetriq_nov14_2014.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2016

- Maman K, Aballea S, Nazir J, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of medical treatments for the management of overactive bladder: a systematic literature review and mixed treatment comparison. Eur Urol 2014;65:755-65

- Herschorn S, Barkin J, Castro-Diaz D, et al. A phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, multicentre study to assess the efficacy and safety of the beta(3) adrenoceptor agonist, mirabegron, in patients with symptoms of overactive bladder. Urology 2013;82:313-20

- Nitti VW, Auerbach S, Martin N, et al. Results of a randomized phase III trial of mirabegron in patients with overactive bladder. J Urol 2013;189:1388-95

- Sexton CC, Notte SM, Maroulis C, et al. Persistence and adherence in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome with anticholinergic therapy: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Clin Pract 2011;65:567-85

- Veenboer PW, Bosch JL. Long-term adherence to antimuscarinic therapy in everyday practice: a systematic review. J Urol 2014;191:1003-8

- Benner JS, Nichol MB, Rovner ES, et al. Patient-reported reasons for discontinuing overactive bladder medication. BJU Int 2010;105:1276-82

- Wagg A, Franks B, Ramos B, et al. Persistence and adherence with the new beta-3 receptor agonist, mirabegron, versus antimuscarinics in overactive bladder: Early experience in Canada. Can Urol Assoc J 2015;9:343-50

- Sacco E, Tienforti D, D’Addessi A, et al. Social, economic, and health utility considerations in the treatment of overactive bladder. Open Access J Urol 2010;2:11-24

- Irwin DE, Mungapen L, Milsom I, et al. The economic impact of overactive bladder syndrome in six Western countries. BJU Int 2009;103:202-9

- Yehoshua A, Chancellor M, Vasavada S, et al. Health resource utilization and cost for patients with incontinent overactive bladder treated with anticholinergics. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2016;22:406-13

- Aballea S, Maman K, Thokagevistk K, et al. Cost effectiveness of mirabegron compared with tolterodine extended release for the treatment of adults with overactive bladder in the United Kingdom. Clin Drug Investig 2015;35:83-93

- Nazir J, Maman K, Neine ME, et al. Cost-effectiveness of mirabegron compared with antimuscarinic agents for the treatment of adults with overactive bladder in the United Kingdom. Value Health 2015;18:783-90

- Bettez M, Tule M, Carlson K, et al. 2012 update: guidelines for adult urinary incontinence collaborative consensus document for the canadian urological association. Can Urol Assoc J 2012;6:354-63

- Nitti VW, Khullar V, van Kerrebroeck P, et al. Mirabegron for the treatment of overactive bladder: a prespecified pooled efficacy analysis and pooled safety analysis of three randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III studies. Int J Clin Pract 2013;67:619-32

- Nazir J, Posnett J, Walker A, et al. Economic evaluation of pharmacological treatments for overactive bladder from the perspective of the UK National Health Service. J Med Econ 2015;18:390-7

- Statistics Canada. Age-standardized mortality rates by selected causes, by sex (Both sexes). 2015 [updated 10 May 2016]. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/health30a-eng.htm. Accessed August 22, 2016

- The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Schedule of benefits for physician services under the Health Insurance Act. 2015 [updated 10 May 2016]. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ohip/sob/physserv/sob_master11062015.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2016

- British National Formulary. 2016 [updated 10 May 2016]. https://www.bnf.org. Accessed August 22, 2016

- Healthwick Canada. Prevail moderate bladder control pads. [updated 10 May 2016]. http://www.healthwick.ca/prevail-bladder-control-pad-moderate. Accessed August 22, 2016

- Statistics Canada. Consumer Price Index. CANSIM tables. 2016 [updated 10 May 2016]. http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?id=3260020. Accessed August 22, 2016

- Astellas Pharma Canada Inc. Mirabegron. IMS country retail sales audit, September 2016. Canada Market Shares for HEOR. Data on file. 2016

- Arlandis-Guzman S, Errando-Smet C, Trocio J, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of antimuscarinics in the treatment of patients with overactive bladder in Spain: a decision-tree model. BMC Urol 2011;11:9

- Statistics Canada. Average hourly wages of employees by selected characteristics and occupation, unadjusted data, by province (monthly). 2016 [updated 10 May 2016]. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/labr69a-eng.htm. Accessed 22, August 2016

- Ganz ML, Smalarz AM, Krupski TL, et al. Economic costs of overactive bladder in the United States. Urology 2010;75:526-32, 32 e1–18

- Reynolds WS, Fowke J, Dmochowski R. The burden of overactive bladder on US public health. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep 2016;11:8-13

- Kim TH, Lee KS. Persistence and compliance with medication management in the treatment of overactive bladder. Investig Clin Urol 2016;57:84-93

- Krhut J, Gartner M, Petzel M, et al. Persistence with first line anticholinergic medication in treatment-naive overactive bladder patients. Scand J Urol 2014;48:79-83

- Schabert VF, Bavendam T, Goldberg EL, et al. Challenges for managing overactive bladder and guidance for patient support. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:S118-S22

- Dmochowski RR, Newman DK. Impact of overactive bladder on women in the United States: results of a national survey. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:65-76

- Campbell UB, Stang P, Barron R. Survey assessment of continuation of and satisfaction with pharmacological treatment for urinary incontinence. Value Health 2008;11:726-32

- Yeaw J, Benner JS, Walt JG, et al. Comparing adherence and persistence across 6 chronic medication classes. J Manag Care Pharm 2009;15:728-40

- Robinson D, Thiagamoorthy G, Cardozo L. A drug safety evaluation of mirabegron in the management of overactive bladder. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2016;15:689-96

- Andy UU, Arya LA, Smith AL, et al. Is self-reported adherence associated with clinical outcomes in women treated with anticholinergic medication for overactive bladder? Neurourol Urodyn 2016;35:738-42

- Buysman EK, Liu F, Hammer M, et al. Impact of medication adherence and persistence on clinical and economic outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with liraglutide: a retrospective cohort study. Adv Ther 2015;32:341-55

- Chen S, Swallow E, Li N, et al. Economic benefits associated with beta blocker persistence in the treatment of hypertension: a retrospective database analysis. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:615-22

- Ivanova JI, Hayes-Larson E, Sorg RA, et al. Healthcare resource use and costs of privately insured patients who switch, discontinue, or persist on anti-muscarinic therapy for overactive bladder. J Med Econ 2014;17:741-50

- Wielage RC, Perk S, Campbell NL, et al. Mirabegron for the treatment of overactive bladder: cost-effectiveness from US commercial health-plan and Medicare Advantage perspectives. J Med Econ 2016;19:1135-43

- Herschorn S, Vicente C, Nazir J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of mirabegron 50 mg compared to tolterodine ER 4 mg in the treatment of patients with overactive bladder in Canada. Value Health 2014;17:A469

- The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario Drug Benefit Formulary/Comparative Drug Index. 2016 [updated 10 May 2016]. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/formulary42/edition_42.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2016

![Figure 5. Tornado diagram of deterministic sensitivity analysis (mirabegron vs solifenacin 5/10 mg [generic]).](/cms/asset/9052da7e-01f0-47fe-a1ca-bd8776dfc8c3/ijme_a_1294595_f0005_c.jpg)