Abstract

Objective: This analysis aimed to evaluate trends in volumes and costs of primary elective incisional ventral hernia repairs (IVHRs) and investigated potential cost implications of moving procedures from inpatient to outpatient settings.

Methods: A time series study was conducted using the Premier Hospital Perspective® Database (Premier database) for elective IVHR identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision, Clinical Modification codes. IVHR procedure volumes and costs were determined for inpatient, outpatient, minimally invasive surgery (MIS), and open procedures from January 2008–June 2015. Initial visit costs were inflation-adjusted to 2015 US dollars. Median costs were used to analyze variation by site of care and payer. Quantile regression on median costs was conducted in covariate-adjusted models. Cost impact of potential outpatient migration was estimated from a Medicare perspective.

Results: During the study period, the trend for outpatient procedures in obese and non-obese populations increased. Inpatient and outpatient MIS procedures experienced a steady growth in adoption over their open counterparts. Overall median costs increased over time, and inpatient costs were often double outpatient costs. An economic model demonstrated that a 5% shift of inpatient procedures to outpatient MIS procedures can have a cost surplus of ∼ US $1.8 million for provider or a cost-saving impact of US $1.7 million from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services perspective.

Limitations: The study was limited by information in the Premier database. No data were available for IVHR cases performed in free-standing ambulatory surgery centers or federal healthcare facilities.

Conclusion: Volumes and costs of outpatient IVHRs and MIS procedures increased from January 2008–June 2015. Median costs were significantly higher for inpatients than outpatients, and the difference was particularly evident for obese patients. A substantial cost difference between inpatient and outpatient MIS cases indicated a financial benefit for shifting from inpatient to outpatient MIS.

Background

Abdominal wall hernia repair, one of the most common procedures performed by general surgeonsCitation1,Citation2, is used for several common hernia types, including epigastric, incisional, inguinal, and umbilicalCitation3,Citation4. Incisional ventral hernias occur as a common complication following laparotomyCitation5–7, a procedure performed more than 2 million times annually in the USCitation8. As a result, ∼ 400,000 incisional ventral hernia repairs (IVHRs) are performed each year in the USCitation9. IVHRs can be completed at an inpatient or outpatient site of care (SOC). As for the surgical technique, IVHRs are performed either by the “open” or minimally invasive surgery (MIS) approachCitation10. The operative approach depends on patient factors such as perioperative health, previous operative history, as well as the size and location of the hernia defect. The surgeon’s expertise and preferences are also important factors in determining whether the procedure is performed using open or MIS techniquesCitation3,Citation11. Meta analyses comparing MIS and open IVHR have found similar recurrence rates for both proceduresCitation12–16, higher incidence of wound infections in the open repair groupCitation12–14,Citation16, and shorter length of stay with MISCitation13–16. These studies have concluded that both open and MIS approaches are effective in treating IVHRCitation12–16; however, with more post-operative wound infections after open hernia repairCitation11–14,Citation16, inpatients may incur longer hospital stays and increased cost of care.

The SOC (inpatient vs outpatient facility) and surgical approach (open vs MIS) used for IVHR can affect outcomes, length of stay, and cost, while policy and financial incentives may play a critical role in clinical practice. According to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the national average reimbursement in fiscal year (FY) 2016 for MIS IVHR at outpatient settings increased more than 25% over the previous year, affecting the profitability of certain proceduresCitation17,Citation18. The reimbursement increase for outpatient MIS IVHR may incentivize providers to treat more patients as outpatient MIS cases without compromising the favorable outcomes associated with MIS IVHR.

Epidemiological studies exploring the trends and costs for IVHRs are limited, and their respective data outdatedCitation1,Citation8,Citation19,Citation20; the most recent study we identified included data through 2006Citation7. Few studies included SOC and surgical approaches in their trend and cost analysesCitation8,Citation19,Citation20. However, procedure volume, costs, and, most importantly, reimbursement rate substantially vary by SOC and surgical approaches. Without differentiating by SOC and surgical approaches, the landscape of procedure volume and costs is obscured, and the impact of reimbursement change cannot be estimated.

In light of the CMS reimbursement policy, this study (1) investigated the change in procedure volume, (2) compared costs, (3) examined the use of open or MIS procedures for elective IVHRs over time in both inpatient and outpatient settings, and (4) assessed the potential cost implications of moving procedures from an inpatient to an outpatient setting (outpatient migration).

Methods

Design overview

The study analyzed the Premier Hospital Perspective® Database (Premier database) for elective IVHR from January 2008 through June 2015, the most current dataset available at the time. Elective IVHR cases were identified by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codesCitation21. Examining data from January 2008–June 2015, the study included the following analyses: IVHR procedure volume trend analysis, evaluating the changes in utilization of SOC (inpatient and outpatient) and surgical approach (MIS and open procedures); time series analysis, investigating the change in costs related to SOC and surgical approach over time; and economic impact analysis, estimating the potential cost impact of outpatient migration. Additionally, since obesity is a public health concern and a known risk factor for IVHR, volume trend and cost sub-group analyses were conducted for obese and non-obese patients.

Identification of patients

The study included patients ≥18 years of age who underwent elective IVHR (ICD-9-CM codes 53.51, 53.61, 53.62Citation21) from January 2008–June 2015 in the Premier databaseCitation22. The Premier database contained cost, billing, and procedure data for more than 700 hospitals, including hospital-affiliated acute care facilities and ambulatory surgery centers (ASC) and clinics located throughout the US. The Premier database accounted for 20% of inpatient discharges and 530 million outpatient visits, with 50 million being collected per year since 2011Citation23. Cases with IVHR listed as a secondary procedure were excluded from the study. The SOC of IVHR was defined based on the outpatient/inpatient indicator in Premier (Supplementary Table S1). Patients were classified as inpatients if admitted to hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, or long-term care. Patients were classified as outpatients if they had outpatient, same day, or ambulatory surgery in which the patient is discharged within 23 hours of the procedure.

Determination of procedure volumes

Among the study population, MIS cases were identified by ICD-9-CM code 53.62 and national Current Procedural Terminology 4th Edition (CPT-4) codes 49654, 49655, 49656, and 49657. With regard to the surgical approach, robotic-assisted IVHR, which was defined with ICD-9-CM codes 17.41, 17.42, 17.43, 17.44, 17.45, and 17.49, and a search of billing text for “ROBOT”, “DA VINCI”, or “ENDOWRIST”, but without “ARTH ROBOT” were added to the MIS group. In a similar manner, the patients with ICD-9-CM codes 53.51, or 53.61, or CPT-4 codes 49560, 49561, 49565, or 49566 were defined as open cases. Patients with MIS and/or conversion code ICD-9-CM V64.41 were excluded from open cases.

Determination of costs

From the identified IVHR procedures, cost data were captured through the actual cost variables recorded in the Premier database. Cost included fixed (overhead) and variable (direct) cost data during initial hospitalization. The majority of hospitals within the Premier database (≈75%) reported actual cost data per their own accounting systems, whereas the remainder provided cost based on each hospital’s specific cost-to-charge ratioCitation24–26. Costs of re-admission or re-visits were not included in this analysis because the Premier database can only link same-hospital visits, which is not an accurate reflection of the true re-admission/re-visit situation, especially for outpatient cases. All costs of the initial visit were adjusted for inflation using the historical Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) from December 2015Citation27,Citation28 and reported in 2015 US dollars, according to the direct medical cost inflation adjustment method published from the Centers for Disease Control and PreventionCitation28.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as SOC characteristics of inpatient and outpatient cases. Patient socio-demographics included age, race, marital status, and insurance type (Medicare, Medicaid, commercial, or other). Patient clinical characteristics included Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)Citation29 and obesity status. SOCs were classified as either inpatient or outpatient facilities. Region (Northeast, South, Midwest, or West), bed size (<200, 200–399, 400–600, or >600), area (urban vs rural), and teaching status were examined as hospital characteristics. Continuous variables and categorical variables were compared using t-tests and Chi-square tests.

Trend analyses were performed to examine the changes in proportion of the IVHRs by SOC (inpatient vs outpatient) and surgical approach (open vs MIS) in the study period. Time series analyses were performed to assess costs of initial visit by SOC and surgical approach. Quantile regression on first quartile, median, and third quartile costs was conducted in covariate-adjusted models. Patient socio-demographic and clinical, physician, and hospital characteristics listed above, and calendar year were used in covariate-adjusted models. Further sub-group analyses for volume trend and costs were performed by obesity level (obese: BMI ≥30; non-obese: BMI <30). Costs of the respective procedures were also examined for each payer. Wilcoxon non-parametric tests were used to evaluate the differences in median cost and CMS reimbursement rate between inpatients and outpatients. All the analyses were done in SAS version 9.4 (SAS institute, Cary, NC).

Budget impact analysis

The budget impact of the potential outpatient migration was estimated from both a CMS perspective and a hospital provider perspective. CMS reimbursement rates for inpatient and outpatient IVHR were applied. Median costs for inpatient open and MIS IVHR were compared with the established 2016 Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) reimbursement rates (353, 354, 355) (Supplementary Table S2)Citation30. Based on the parameters of the DRG, both inpatient open procedures and MIS procedures are reimbursed at the same rateCitation31. Median costs for outpatient open and outpatient MIS procedures during the study period were compared with the FY 2016 CMS reimbursement rates. Given the substantial cost increase during the entire study period, the median costs in the most recent year (July 2014–June 2015) were included in this analysis. Sub-group analysis for obese patients was also conducted. Budget impact (i.e. costs vs reimbursement) for providers and payers was calculated assuming a 5% outpatient migration and 1% outpatient migration among obese patients in FY 2016.

Results

Patients

A total of 106,552 elective IVHR cases were identified for the period January 2008–June 2015. Among these cases (Supplementary Table S3), the majority of the patients were white (77%) and female (62%). IVHRs were performed more in non-obese patients than in patients with an obesity ICD-9 diagnosis (BMI ≥30) (77% vs 23%). Nearly half the population (47%) were between the ages of 45–64 years. More than 80% of the total patient population had either Medicare (39%) or commercial insurance (44%). Most patients (85%) sought care at a facility located in an urban area. Patients with a CCI score of zero typically had an outpatient procedure (65%).

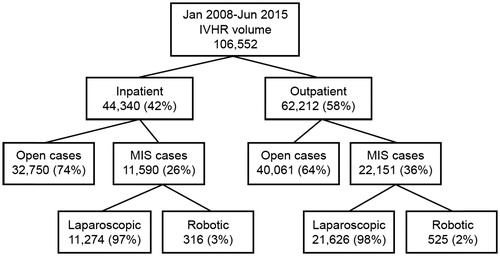

Of the 106,552 elective IVHR cases performed from January 2008–June 2015, 58% were conducted at an outpatient SOC (Supplementary Table S3, ). More open procedures than MIS procedures were performed at both SOCs (open: inpatient: 74%, outpatient: 64%; MIS: inpatient: 26%, outpatient: 36%). Patient characteristics by SOC for the most recent year included in this analysis (July 2014–June 2015) are presented in . Similar to the entire population, the majority of the patients were white (80%) and female (61%). In this cohort, 41% had commercial insurance and 26% had Medicare. Patients with no comorbidities according to CCI typically had an outpatient procedure (63%), and 84% sought care at a facility in an urban area, which is similar to the entire dataset.

Figure 1. Elective IVHR cases identified from the premier database, January 2008–June 2015. IVHR: incisional ventral hernia repair; MIS: minimally invasive surgery.

Table 1. Patient characteristics of inpatient and outpatient incisional ventral hernia repairs, July 2014–June 2015.

Procedure volume trend

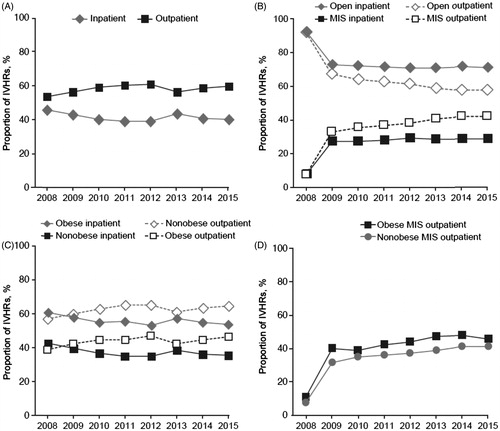

During the course of the analysis, the proportion of outpatient procedures increased slightly from 54% to 60%, while inpatient procedures decreased from 46% to 40% (). The proportion of total procedures conducted as MIS procedures at inpatient and outpatient care settings increased from 8% to 29% and 8% to 42%, respectively (). Specifically, inpatient open procedures decreased substantially from 2008–2009 and leveled off from 2010 and thereafter. Meanwhile, inpatient MIS procedures increased from 2008–2009, which also flattened after 2010. In contrast, the proportion of open outpatient procedures continued to decrease from January 2008–June 2015.

Figure 2. Outpatient migration, January 2008–June 2015: (a) Proportion of IVHR by SOC; (b) Proportion of open or MIS IVHR by SOC; (c) Proportion of IVHRs in non-obese and obese patients by SOC; (d) Proportion of outpatient MIS IVHRs among non-obese and obese patients. IVHR: incisional ventral hernia repair; MIS: minimally invasive surgery; SOC: site of care.

In 2015, a majority of the non-obese population (65%) underwent an outpatient IVHR, whereas 54% of the obese population had their IVHR completed in an inpatient facility (). Compared with non-obese outpatient cases, the proportion of MIS was higher (p < .0001) and the slope of increase was steeper among obese outpatient visits ().

Costs: overall inpatient vs outpatient

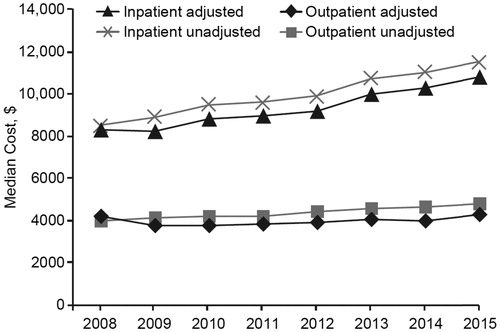

The unadjusted median cost for inpatient IVHR was higher than the cost for outpatient IVHR (US $8517 vs US $4009 in 2008; US $11,532 vs US $4816 in 2015) (). Similar results were observed after adjustment for inflation (US $8354 vs US $4185 in 2008; US $10,845 vs US $4259 in 2015). Although the costs for both inpatient and outpatient procedures rose over the years, inpatient costs experienced a larger increase. Of note, the inflation-adjusted median cost for an inpatient procedure (US $10,845 from January 2015–June 2015) exceeded the respective $9108 CMS reimbursementCitation30. Reimbursement of outpatient procedures varied by surgical approach, so a comparison of cost and reimbursement in overall outpatient populations was not performed.

Figure 3. Unadjusted and adjusted* median cost in inpatients and outpatients, January 2008–June 2015. Costs are presented in US dollars. * Adjusted for age, gender, race, marital status, obesity status, payer mix, surgical approach, Charlson comorbidity score, and facility characteristics (size, region, area, affiliations).

Costs: MIS vs open

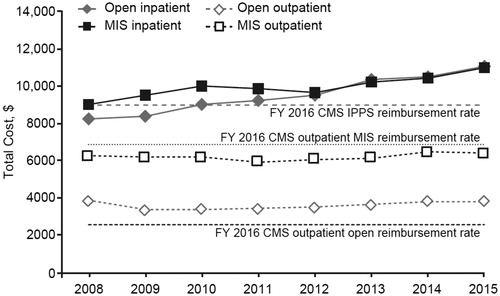

From January 2008–June 2015, adjusted median costs of both open and MIS procedures in the inpatient setting increased (open: US $8229 to US $11,032; MIS: US $9050 to US $10,997) (). Among outpatient visits, adjusted median costs for MIS and open were relatively stable. In the first half of 2015, the adjusted median cost for MIS in the outpatient setting was $6422 (25th percentile, 75th percentile: US $5065, $8586), which was lower than the $6861 CMS reimbursement for laparoscopic IVHR in FY 2016Citation17 (Wilcoxon test p < .0001); the adjusted median cost for open IVHR was $3,847 (25th percentile, 75th percentile: US $3,038, $5,264), which was higher than the CMS reimbursement of $2,613 for open IVHR in FY 2016Citation17 (Wilcoxon test, p < .0001).

Figure 4. Adjusted median cost* of IVHRs by surgical approach and SOC, January 2008–June 2015. Costs are presented in US dollars. * Adjusted for age, gender, race, marital status, obesity status, payer mix, surgical approach, Charlson comorbidity score, and facility characteristics (size, region, area, affiliations). CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; FY, fiscal year; IPPS, inpatient prospective payment systems; IVHR, incisional ventral hernia repair; MIS, minimally invasive surgery; SOC, site of care.

Costs: obesity

The adjusted median costs for obese patients were higher than for non-obese patients in both inpatients and outpatients. Further, the difference in adjusted median cost for inpatient and outpatient IVHR was higher in obese patients than in non-obese patients (Δ (inpatient vs outpatient): obese US $5,900; non-obese US $5,096) ().

Table 2. Unadjusted and adjusted difference between inpatient and outpatient median cost of IVHR in overall and obese patients, January 2008–June 2015.

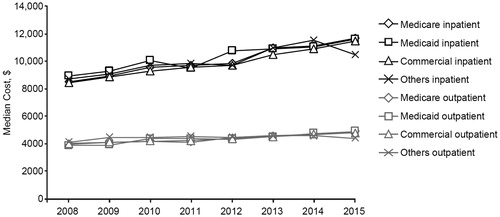

Costs: difference by payer

Per the adjusted cost model of all payers (), median costs for an inpatient IVHR ranged from US $9,690–$10,128, while the median adjusted outpatient costs for all payers were more than 50% lower (range: US $4,453–$4,639). Although median costs greatly differed by SOC, no substantial difference was observed among payers ().

Figure 5. Unadjusted median cost of IVHR for all payers by SOC, January 2008–June 2015. Costs are presented in US dollars. IVHR: incisional ventral hernia repair; SOC: site of care.

Table 3. Unadjusted and adjusted median cost in inpatients and outpatients by payers, January 2008–June 2015.

Budget impact analysis

A budget impact model was developed to explore the effect of changing the SOC or surgical approach, given the current IHVR cost and reimbursement environment. For inpatient procedures, the weighted average reimbursement rate (FY 2016) provided by CMS for an IVHR case is US $9,108Citation30. For outpatient open and MIS, the reimbursement rate (FY 2016) is US $2,613 and US $6,861, respectively. From a provider perspective, considering the current cost and reimbursement rates for inpatient IVHR and the increased median cost in the most recent year (US $11,030 per case), there is a potential loss of US $1,922 per procedure in reimbursement. For outpatient IVHR, an open case has a median Medicare cost of $3,820 and a CMS reimbursement of US $2,613, resulting in a net loss of US $1,207 per procedure; a MIS case with a median Medicare cost of US $6,392, and a respective CMS reimbursement rate of $6,861 results in a positive profit margin of US $469 for each outpatient MIS procedure. Considering the aforementioned per case loss and profit scenarios, the migration of one inpatient case to an outpatient MIS procedure yields an estimated US $2,391 budget surplus for the hospital provider. Assuming a 5% inpatient case migration to outpatient MIS procedures, the budget surplus could reach US $1.8 million for providers ().

Table 4. Budget impact analysis for outpatient migration from provider and payer perspectives, July 2014–June 2015.

Examining the current reimbursement structure from a payer perspective, one inpatient IVHR case converted to an outpatient MIS procedure could result in US $2,247 cost savings per case. Thus, 5% migration of current inpatient IVHR procedures (773 cases) to outpatient MIS IVHR would likely yield a CMS budget surplus of more than US $1.7 million ().

Similarly, given the current cost and DRG structure, inpatient IVHR procedures in obese patients would result in a contribution of US $2,093 per case from a provider perspective. From the CMS perspective, assuming 1% of the current inpatient IVHR procedures in obese patients (51 cases) were converted to outpatient MIS, US $165,596 could be saved (). Likewise, further cost savings could be captured if the outpatient migration increased to 2% or 5%.

Discussion

Data on SOC, surgical approaches, and associated costs for ventral hernia repairs, a common, high-volume procedure in general surgery, were surprisingly scarceCitation8,Citation32. Our study utilized the most recent data available (through June 2015) from a nationwide database to examine the current landscape of IVHRs by SOC and surgical approach. The study demonstrated an increased trend of outpatient IVHR procedures, along with a substantial increase of outpatient MIS. With the cost data from the nationwide database and CMS reimbursement rates reported by SOC and by surgical approach, the study quantified the economic implications of the CMS reimbursement increase of outpatient IVHR for providers and payers.

During the past decade, the adoption of MIS has shaped surgical practice, influenced SOC of surgery, and improved the post-operative outcomes of patients. One of the purported benefits of MIS is that it may enable more outpatient surgery, but this assumption is poorly documented for ventral hernia repairs. Our findings demonstrate that this is in fact the case: the introduction of MIS was associated with a substantial decrease of open IVHR in outpatients and a decrease of inpatient IVHR as a whole. The uptake of MIS potentially stems from a multitude of factors: (1) improved patient outcomes through lower rates of infectionCitation11–14,Citation16 and shorter hospital staysCitation2,Citation7,Citation13–16; (2) increased awareness and training among general surgeons; and (3) advances in equipment and instrumentation. The feasibility and benefits of MIS have been more accepted, such that it has become more integrated into a modern surgical armamentarium.

The study also detected increased median costs for inpatients and a substantial cost gap between SOC, which did not vary much by payer. The considerable cost difference between inpatient and outpatient procedures presents a financial incentive for providers to perform more outpatient IVHRs. Accordingly, CMS announced a reimbursement increase for outpatient IVHRs, particularly outpatient MIS procedures in 2016Citation30. CMS’s payment incentive may further accelerate outpatient migration. This study suggests that better triage of incisional hernia patient flow and wiser use of valuable and limited healthcare resources could potentially save the health system hundreds of millions of dollars.

It has been reported previously that utilization of an MIS approach in abdominal wall hernias increased 40% from 2009–2012Citation10. Thus, a migration of 5% of cases to an outpatient MIS procedure (), the premise of our budget impact model, is a conservative estimate that appears to be well within the MIS adoption trend. Further, our budget impact analysis calculations were based on the Medicare population, which may not be the most suitable group for outpatient MIS IVHR, due to the patient’s perioperative health (i.e. age of the population, potential for pre-existing comorbidities, etc.). Hence, a 5% shift among this population may be feasible, while a greater outpatient migration among other demographics is quite possible. As one of the most common procedures in the US, with more than US $1 billion charged every year for incisional hernia managementCitation20, even small shifts in SOC may have a sizable budget impact. Our study demonstrates that, with the current increased reimbursement for outpatient MIS IVHR, a conservative 5% shift of Medicare patients to outpatient SOC could save CMS more than US $1 million. Such cost savings may appeal to private payers, since the possibility of outpatient migration could be higher among primary insurers, given that their insured may be younger and/or healthier than the Medicare population and, therefore, offer more opportunity for outpatient migration and potentially higher cost savings. However, payers may need to be aware that reimbursement policies requiring all IVHRs be performed as outpatient MIS should be discouraged. Patients should be evaluated for meeting a certain patient risk profile, and only those suitable candidates should undergo an outpatient MIS approach. Performing this approach in unsuitable patients could lead to higher overall costs if complications, recurrence, and/or conversion occurs.

Given the prevalence of obesity among the general population, and obesity being an established risk factor for incisional ventral herniasCitation33–37, we further investigated the median costs and financial implications of outpatient migration among the obese population. The obese population demonstrated a shift to more outpatient procedures, indicating that hospitals and clinicians gained confidence in managing these difficult cases on an outpatient basis. This suggests that an additional 1% of the current inpatient procedures in obese patients that could be shifted to an outpatient facility is a rather conservative estimate, given the current adoption rate.

Because MIS conducted at an outpatient SOC may save costs, providers and payers should further investigate potential interventions and technologies that could facilitate additional outpatient SOC migration without compromising quality of care, in particular for obese patients. Advanced approaches and enabling technologies can improve access, maneuverability, visualization, and enhance surgeon confidence in tackling difficult cases via an MIS techniqueCitation2. However, additional research is needed to confirm the economic impact of these advanced technologies for hernia repairs.

Not all patients may be suitable candidates for outpatient MIS IVHRs, such as complex patients with large hernia size or severe comorbidity; however, shifting clinically appropriate IVHR patients to an outpatient setting could have potential benefits beyond cost savings. For example, hospital resources, such as operative time and inpatient beds, could be reserved for more complex inpatient IVHR procedures or other more critically ill patients. Additionally, conducting more outpatient IVHRs may improve access to timely repairs while reducing the post-operative morbidity associated with inpatient procedures. The economic and clinical benefits could steer more IVHRs to be performed as outpatient MIS procedures. Further sub-population analyses could identify the most appropriate outpatient MIS IVHR candidates, and in-depth investigations of the budget impact could identify more opportunities for cost savings.

The use of an administrative database imposed several limitations that could have affected the procedural volume assessments and cost estimations provided in this analysis. The Premier database represented 20% of patient discharges, and the outpatient data included only a hospital’s outpatient department. Although any available data from hospital-affiliated ASC were included as outpatient data, specific volume and cost information for other ASC settings were limited. Therefore, the total IVHR procedure volume reported herein may be lower than the actual number of total cases, and the median costs may differ as a different reimbursement policy is applied to ASC IVHR cases. Also, the impact on physicians is beyond the scope of this study. The physician perspective may not be accurately represented in the Premier database, as many operate at free-standing clinics, and Premier is a hospital administrative database that does not track independent physician and facility charges. In addition, the Premier database does not include federal healthcare facilities, such as Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals. Given the very different population and costs, these findings may not be generalized to the VA system. Further, within the confines of the Premier database, the data could not be stratified to examine the impact that critical risk factors such as wound class and hernia width have on outcomes and associated costs. For the obese population, only patients with an ICD-9 diagnosis for obesity were captured. Additional obese patients may be contained within the non-obese population, and as such the procedure volume and costs for the obese sub-group may be lower than reported herein. Finally, 25% of providers’ cost, as collected by Premier, was based on Medicare cost-to-charge ratios, not actual costs accrued by the hospital. Costs pertaining to procedural details, e.g. surgical consumables used (type of mesh, type of fixation), cannot be discerned in an administrative database like Premier; therefore, the study may over-estimate the overall cost due to excessive consumption of expensive consumables. However, these inaccurate costing occurrences are intrinsic to administrative databases, and would have impacted both inpatients and outpatients alike, hence, they should not largely bias our estimate of the cost difference between inpatient and outpatient IVHRs.

In summary, given the conservative approach applied in the study and the limitations of the Premier database, we expect the quantified economic impact of outpatient migration was under-estimated when considering the entire US population.

Conclusions

This study revealed the rising trends of primary elective outpatient IVHRs and MIS procedures from January 2008–June 2015, which were more evident among the obese population. In this Premier sample, median costs were significantly higher for inpatients than outpatients, particularly for obese patients. A budget impact analysis demonstrated that, in the current reimbursement environment, shifting inpatient cases to outpatient MIS surgery provides a financial gain for both providers and payers. The overall economic impact of performing MIS IVHR on the appropriate patients could steer more IVHRs to be performed as outpatient MIS procedures.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Intuitive Surgical, Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA) supported this analysis and provided funding for medical writing and editorial support in the development of this manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

CS and EL are employees of Intuitive Surgical, Inc. LS does not have a financial relationship with Intuitive Surgical, Inc. DM serves as a consultant to Intuitive Surgical, Inc, but that relationship is not relevant to this study. No other disclosures were reported. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Tina Rideout, MS, MBA (Ashfield Healthcare Communications, Middletown, CT) provided writing and editorial support, and Dena McWain (Ashfield Healthcare Communications) copyedited and styled the manuscript per journal requirements.

References

- Beadles CA, Meagher AD, Charles AG. Trends in emergent hernia repair in the United States. JAMA Surg 2015;150:194-200

- Gonzalez AM, Romero RJ, Seetharamaiah R, et al. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with primary closure versus no primary closure of the defect: potential benefits of the robotic technology. Int J Med Robot 2015;11:120-5

- American College of Surgeons. Ventral hernia repair. Chicago, US: American College of Surgeons, 2014. https://www.facs.org/∼/media/files/education/patient%20ed/ventral_hernia.ashx. Accessed July 29, 2016

- Livingston EH. What is an abdominal wall hernia? JAMA 2016;316:1610

- Kingsnorth A, Banerjea A, Bhargava A. Incisional hernia repair – laparoscopic or open surgery? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2009;91:631-6

- Le Huu Nho R, Mege D, Ouaissi M, et al. Incidence and prevention of ventral incisional hernia. J Visc Surg 2012;149:e3-14

- Park AE, Roth JS, Kavic SM. Abdominal wall hernia. Curr Probl Surg 2006;43:326-75

- Poulose BK, Shelton J, Phillips S, et al. Epidemiology and cost of ventral hernia repair: making the case for hernia research. Hernia 2012;16:179-83

- Sauerland S, Walgenbach M, Habermalz B, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgical techniques for ventral or incisional hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:CD007781

- Savitch SL, Shah PC. Closing the gap between the laparoscopic and open approaches to abdominal wall hernia repair: a trend and outcomes analysis of the ACS-NSQIP database. Surg Endosc 2016;30:3267-78

- Vorst AL, Kaoutzanis C, Carbonell AM, et al. Evolution and advances in laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair. World J Gastrointest Surg 2015;7:293-305

- Al Chalabi H, Larkin J, Mehigan B, et al. A systematic review of laparoscopic versus open abdominal incisional hernia repair, with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg 2015;20:65-74

- Castro PM, Rabelato JT, Monteiro GG, et al. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy in the repair of ventral hernias: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arq Gastroenterol 2014;51:205-11

- Forbes SS, Eskicioglu C, McLeod RS, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing open and laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair with mesh. Br J Surg 2009;96:851-8

- Sajid MS, Bokhari SA, Mallick AS, et al. Laparoscopic versus open repair of incisional/ventral hernia: a meta-analysis. Am J Surg 2009;197:64-72

- Zhang Y, Zhou H, Chai Y, et al. Laparoscopic versus open incisional and ventral hernia repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg 2014;38:2233-40

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Addendum B January 2016. HCPCS codes, APC groups, and OPPS payment rates [Internet]. Baltimore, US: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2016. https://www.cms.gov/apps/ama/license.asp?file=/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/Hospitaloutpatientpps/Downloads/2016-Jan-Addendum-B-File.zip. Accessed July 29, 2016

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Addendum B January 2015. HCPCS codes, APC groups, and OPPS payment rates [Internet]. Baltimore, US: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2015. https://www.cms.gov/apps/ama/license.asp?file=/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/Hospitaloutpatientpps/downloads/2015-Jan-Addendum-B-File.zip. Accessed July 29, 2016

- Ecker BL, Kuo LE, Simmons KD, et al. Laparoscopic versus open ventral hernia repair: longitudinal outcomes and cost analysis using statewide claims data. Surg Endosc 2016;30:906-15

- Funk LM, Perry KA, Narula VK, et al. Current national practice patterns for inpatient management of ventral abdominal wall hernia in the United States. Surg Endosc 2013;27:4104-12

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Version 32 Full and Abbreviated Code Titles – Effective October 1, 2014. ICD-9-CM Diagnosis and Procedure Codes [Internet]. Baltimore, US: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services https://www.cms.gov/medicare/coding/ICD9providerdiagnosticcodes/codes.html. Accessed July 29, 2016

- Premier Inc. Premier Research Services creates insights through data. Charlotte, US: Premier, Inc., https://www.premierinc.com/transforming-healthcare/healthcare-performance-improvement/premier-research-services/. Accessed August 10, 2016

- Premier Inc. PRS Real World Evidence and Data FAQ. Charlotte, US: Premier, Inc. https://www.premierinc.com/transforming-healthcare/healthcare-performance-improvement/premier-research-services/. Accessed August 10, 2016

- Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, et al. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA 2010;303:2359-67

- Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Lahti M, et al. Antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA 2010;303:2035-42

- Wright JD, Ananth CV, Lewin SN, et al. Robotically assisted vs laparoscopic hysterectomy among women with benign gynecologic disease. JAMA 2013;309:689-98

- Crawford MCJ, Akin B. CPI detailed report. Washington, D.C., US: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Division of Consumer Prices and Price Indexes, 2015. http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpid1512.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2016

- Scott RD. The direct medical costs of healthcare-associated infections in U.S. hospitals and the benefits of prevention. Atlanta, US: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009 https://www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/hai/Scott_CostPaper.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2016

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-83

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital inpatient prospective payment systems for acute care hospitals and the long term care hospital prospective payment system changes and FY2016 rates final rule, 80 Fed. Reg. 49325-49843. Medicare Program [Internet]. Baltimore, US: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2015. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-08-17/pdf/2015-19049.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2016

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Inpatient PPS PC Pricer. Baltimore, US: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/pcpricer/inpatient.html. Accessed August 11, 2016

- Lee J, Mabardy A, Kermani R, et al. Laparoscopic vs open ventral hernia repair in the era of obesity. JAMA Surg 2013;148:723-6

- Anthony T, Bergen PC, Kim LT, et al. Factors affecting recurrence following incisional herniorrhaphy. World J Surg 2000;24:95-100, discussion 1

- Lau B, Kim H, Haigh PI, et al. Obesity increases the odds of acquiring and incarcerating noninguinal abdominal wall hernias. Am Surg 2012;78:1118-21

- Llaguna OH, Avgerinos DV, Lugo JZ, et al. Incidence and risk factors for the development of incisional hernia following elective laparoscopic versus open colon resections. Am J Surg 2010;200:265-9

- Schreinemacher MH, Vijgen GH, Dagnelie PC, et al. Incisional hernias in temporary stoma wounds: a cohort study. Arch Surg 2011;146:94-9

- Sugerman HJ, Kellum JM Jr, Reines HD, et al. Greater risk of incisional hernia with morbidly obese than steroid-dependent patients and low recurrence with prefascial polypropylene mesh. Am J Surg 1996;171:80-4