Abstract

Aims: To compare economic and clinical outcomes between patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRY) or laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) with use of powered vs manual endoscopic surgical staplers.

Materials and methods: Patients (aged ≥21 years) who underwent LRY or LSG during a hospital admission (January 1, 2012–September 30, 2015) were identified from the Premier Perspective Hospital Database. Use of powered vs manual staplers was identified from hospital administrative billing records. Multivariable analyses were used to compare the following outcomes between the powered and manual stapler groups, adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics and hospital-level clustering: hospital length of stay (LOS), total hospital costs, medical/surgical supply costs, room and board costs, operating room costs, operating room time, discharge status, bleeding/transfusion during the hospital admission, and 30, 60, and 90-day all-cause readmissions.

Results: The powered and manual stapler groups comprised 9,851 patients (mean age = 44.6 years; 79.3% female) and 21,558 patients (mean age = 45.0 years; 78.0% female), respectively. In the multivariable analyses, adjusted mean hospital LOS was 2.1 days for both the powered and manual stapler groups (p = .981). Adjusted mean total hospital costs ($12,415 vs $13,547, p = .003), adjusted mean supply costs ($4,629 vs $5,217, p = .011), and adjusted mean operating room costs ($4,126 vs $4,413, p = .009) were significantly lower in the powered vs manual stapler group. The adjusted rate of bleeding and/or transfusion during the hospital admission (2.46% vs 3.22%, p = .025) was significantly lower in the powered vs manual stapler group. The adjusted rates of 30, 60, and 90-day all-cause readmissions were similar between the groups (all p > .05). Sub-analysis by manufacturer showed similar results.

Limitations: This observational study cannot establish causal linkages.

Conclusions: In this analysis of patients who underwent LRY or LSG, the use of powered staplers was associated with better economic outcomes, and a lower rate of bleeding/transfusion vs manual staplers in the real-world setting.

Introduction

According to the data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 37.7% of adults in the US were obese (body mass index [BMI]: ≥30 kg/m2) and 7.7% had severe obesity (BMI: ≥40 kg/m2) in the 2013 to 2014 timeframeCitation1. The association between severe obesity and adverse health risks, including type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, and cancer, among others, has been well documentedCitation2. In the US, the medical costs associated with obesity have been estimated at $209.7 billion annually in 2008 dollars, with the majority of the costs attributed to treating cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetesCitation3–5.

Bariatric surgery is considered an effective procedure for stimulating significant weight loss and improving obesity-related comorbidities among severely obese personsCitation2,Citation6,Citation7. According to an analysis based on the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database, the number of bariatric surgeries performed in the US from 2008–2012 was estimated at 598,576Citation8. Bariatric surgery techniques have evolved over the last decade, and nearly all surgeries are currently performed using the minimally invasive laparoscopic approach, which is associated with shorter hospital stays and lower complication rates than the open approachCitation8–10. Of the laparoscopic bariatric surgeries that are currently performed, the two most common are laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRY), which together accounted for 97.7% of bariatric procedures performed at academic medical centers in 2014Citation11. LSG is a relatively newer procedure than LRY, and its use has grown rapidly over the past several years, from less than one quarter of bariatric procedures at academic medical centers in the 4th quarter of 2011, to over 60% in the second quarter of 2014Citation11.

Endoscopic surgical stapling devices (henceforth, staplers) were introduced to facilitate tissue approximation and transection during endoscopic surgeryCitation12. Staplers simplify the procedure and require less skill of the surgeon, but have been associated with complications, including leakage from staple lines, bleeding, and fistula formationCitation13–15. The first powered stapler (i.e. those for which the staples and the knife blade are driven not by manual force but instead by a power source) was approved for launch by the US FDA in 2010 for Covidien (now Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) under the brand name “iDrive™ powered stapling system”Citation16. Subsequently, Ethicon (Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, NJ) received approval to launch their ECHELON FLEX™ Powered ENDOPATH Stapler in the US in 2011Citation12. Both manufacturers have since introduced subsequent versions of their powered endoscopic stapling devices, namely the ‘iDrive™ Ultra powered stapling system’ from Covidien/Medtronic, and the ‘ECHELON FLEX™ Powered Plus Stapler’ with the ‘ECHELON FLEX™ GST System’ from Ethicon/Johnson & Johnson.

These powered staplers were developed to increase stability and enable more precise stapling relative to non-powered (manual) staplers. It is currently unclear, however, the extent to which such potential differences between the operation and performance of powered vs manual staplers translate into any differences in economic and clinical outcomes in the real-world setting. Thus, we conducted a large, retrospective, observational study in which we compared economic and clinical outcomes of US patients who underwent LRY or LSG with use of powered vs manual staplers.

Methods

Data and patient selection

This study’s data source was the Premier Perspective Hospital Database, which comprises administrative and hospital billing information for all hospital discharges occurring within more than 600 hospitals throughout the US. The database contains discharge-level information on all International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnoses and procedures recorded during each admission, a date-stamped log and cost of all billed items by cost-accounting department, administrative records on length of stay and discharge status, and selected information on patient, provider, hospital, and insurance characteristics. Although the database excludes federally funded hospitals (e.g. Veterans Affairs), the hospitals included therein are nationally representative based on bed size, geographic region, location (urban/rural), and teaching status.

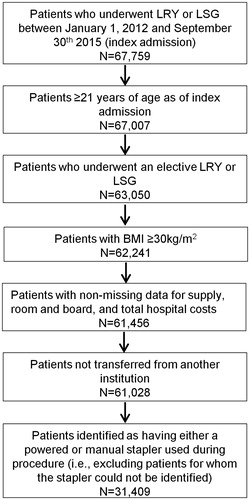

shows the study’s patient selection process. Patients selected for study underwent elective LRY or LSG, as evidenced by ICD-9-CM procedure coding (See Supplemental Appendix 1 for a listing of all codes used in the study) during a hospital admission between January 1, 2012 and September 30, 2015. The first hospital admission for LRY or LSG during this period was defined as the index admission, and patients were required to be at least 21 years of age at the time of the index admission. Patients were also required to have an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code indicative of BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Patients were excluded from the study if they had missing data on hospital supply, room and board, or total hospital costs, if they were transferred from another institution, or if they had other bariatric procedures during the index admission.

Figure 1. Selection of patient population. BMI: body mass index; LRY: laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; LSG: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Use of either powered or manual staplers during the index admission was identified from hospital administrative records by searching for various combinations of device names (e.g. iDrive™ powered stapling system), model numbers (e.g. PCE45A), and/or descriptors of devices being “powered”. Staplers were also further classified by manufacturer (Medtronic powered, Medtronic manual; Ethicon powered; Ethicon manual) to support sensitivity analyses, as described below. Only patients for whom a stapler used during the index admission could be identified as either powered or manual were retained for study; patients with evidence of both powered and manual staplers were excluded from the study, due to the inability to assign them to one of the two study groups.

Measurement of patient and hospital/provider characteristics

Patient demographics and hospital/provider characteristics measured during the index admission included age, sex, marital status, race, payer type, urban vs rural hospital, hospital teaching status, hospital geographic region, hospital bed size, operating physician specialty, year of surgery/index admission, annual hospital surgical volume for LRY and LSG, and an indicator for whether hospital costs are derived from a cost-to-charge ratio vs procedural costing. Patient clinical characteristics measured during the index admission included BMI, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)Citation17, the day on which the LRY or LSG surgery was performed after hospital admission, and several individual comorbidities (alcohol abuse, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, congestive heart failure, depression, diabetes, hypertension, hypothyroidism, liver disease, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, pulmonary circulation disorders, renal failure, rheumatoid arthritis, valvular disease). Comorbidities and the CCI were measured through the presence of ICD-9-CM codes, excluding those for which there was an indication that the comorbidity was not present on admission.

Measurement of economic and clinical outcomes

Economic and clinical outcomes evaluated during the index admission included hospital length of stay (LOS), total hospital costs, medical/surgical supply costs, room and board costs, operating room costs, operating room time (information on operating room time was available for most [93.6%] of the patients, and this outcome was analyzed only among patients with such information available), discharge to a home or home health organization vs other setting (e.g. skilled nursing facility), the composite complication of bleeding and/or transfusion based on ICD-9-CM codes and hospital billing records for transfusion supplies, and all-cause readmissions within 30, 60, and 90 days post-discharge. All costs were inflation adjusted to 2015 US dollars using the Medical Care component of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index. Within the study protocol, the bleeding and/or transfusion and all-cause readmission outcomes were designated as exploratory, while other outcomes were designated as primary. The exploratory outcomes were designated as such due to uncertainty regarding the validity of clinical coding (in the case of bleeding and/or transfusion) and because readmissions to the hospital within the Premier Perspective Hospital Database are captured only when the patient returns to the hospital in which the index admission took place, thereby introducing the potential for incomplete outcome data capture.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted for the overall population and were repeated separating the overall population into surgery type sub-groups (LRY or LSG). Bivariate analyses, stratified by the powered vs manual stapler groups, were utilized to describe patient and hospital/provider characteristics and unadjusted outcomes.

Multivariable regression models were used to compare outcomes between the powered vs manual stapler group, adjusting for all of the above-mentioned patient and hospital/provider characteristics. All models used link functions and error distributions which were tailored to the empirical distribution of the outcome variable based on the Modified Park testCitation18,Citation19, specifically: log link and negative binomial or Poisson error distribution for length of stay; log link and gamma error distribution for costs; log link and Poisson error distribution for operating room time; and logit link and binomial error distribution for the remaining dichotomous outcomes (discharge to a home or home health organization vs other setting, the composite complication of bleeding and/or transfusion, and all-cause readmissions within 30, 60, and 90 days post-discharge). To account for the hospital-level clustered nature of the data, Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) models were initially tested using an exchangeable working correlation structure—chosen based on a qualitative understanding of the potential nature of clustering within hospitals. For the model of room and board costs in the overall sample and all models of operating room time, an independent working correlation structure was substituted, because the models initially failed to converge. When neither an exchangeable nor independent working correlation structure resulted in model convergence, which was the case for all models of all-cause readmissions, Mixed Models were used in order to account for hospital-level clustering.

Adjusted outcomes were generated for each of the comparator groups using the least squares means approach based on observed margins. In the GEE models, inference was based on empirical (robust) standard error estimates. A two-sided critical value of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3.

Sub-group and sensitivity analyses

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted to address potential issues of confounding or effect modification. First, in order to test whether the powered vs manual findings were driven by manufacturer-level phenomena, a sensitivity analysis was conducted in which the multivariable models were repeated comparing patients undergoing bariatric surgery with use of an Ethicon-manufactured powered stapler (which account for the majority of powered staplers) to those with use of a Medtronic-manufactured manual stapler. This analysis was also of interest, owing to the fact that these two categories of staplers formed the majority in the powered and manual platforms.

Next, the concomitant use of a buttress during the surgery was explored. According to the 2012 International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement, the use of staple line reinforcement, such as a buttress or over-sewing the staple line, is thought to reduce bleeding along the staple lineCitation20–23. However, staple line reinforcement has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of leaks in observational studiesCitation21–23. Although the Premier Perspective Hospital Database does not contain information to support identification of over-sewing the staple line, buttress materials can be identified from hospital administrative records by searching for billing records of buttress materials. Thus, to address buttress as a potential confounding factor, a sensitivity analysis was conducted, using the overall population, in which unadjusted outcome data were compared between the sub-set of the powered and manual stapler groups, which had evidence of buttress, to examine whether these outcome data differed meaningfully from the primary analysis. A separate sensitivity analysis was conducted in which buttress was included as a covariate in the multivariable models—a variable which was not included in the primary analysis due to the likely low sensitivity of search algorithms to identify buttress materials (i.e. the absence of identified buttress materials does not necessarily indicate that it was not actually used).

Finally, circular staplers may be used to create the gastrojejunostomy anastomosis as an alternative to the staplers of interest under study, which introduces potential for use of another device in an important step of the LRY. There are presently mixed data on whether circular staplers increase the risk of complications in in LRYCitation24,Citation25; however, if this technique correlates with use of powered vs manual staplers, it is possible that it could be a confounding factor for a number of the study outcomes—particularly costs arising from use of a second device. Thus, another sensitivity analysis was performed in which circular stapler use was included as a covariate in the multivariable models for the sub-group of patients undergoing LRY. This variable was not included in the primary analyses for the same reason noted for buttress above; bivariate analysis in the sub-group of LRY patients who had evidence of circular stapler use was not undertaken due to a small number of patients for whom there was such evidence.

Results

Patient and hospital/provider characteristics

Patient demographics, patient clinical characteristics, and hospital/provider characteristics are shown in in , respectively. Of the overall study population (n = 31,409), 9,851 patients (mean age = 44.6 years; 79.3% female) were in the powered stapler group, and 21,558 patients (mean age = 45.0 years; 78.0% female) were in the manual stapler group. Among patients in the overall study population’s powered stapler group, 91.8% underwent bariatric surgery with use of an Ethicon-manufactured powered stapler, while 8.2% underwent bariatric surgery with use of a Medtronic-manufactured powered stapler. Among patients in the overall study population’s manual stapler group, 44.6% underwent bariatric surgery with use of an Ethicon-manufactured manual stapler, while 57.6% underwent bariatric surgery with use of a Medtronic-manufactured manual stapler; a small proportion of patients had evidence of both manufacturers’ brands of manual staplers being used. These proportions were relatively similar in the LRY and LSG sub-groups.

Table 1. Patient demographics.

Table 2. Patient clinical characteristics.

Table 3. Hospital/provider characteristics.

The majority of patients in the overall study population were between the ages of 35 and 54 years (powered = 55.9%; manual = 55.6%), white (powered = 68.2%; manual = 60.9%), and had commercial insurance coverage (powered = 58.6%; manual = 61.1%). Most were admitted for laparoscopic bariatric surgery at large (bed size = 300 to >500: powered = 67.3%; manual = 71.0%), teaching (powered = 62.2%; manual = 52.1%), urban hospitals (powered = 93.4%; manual = 87.2%). The hospitals to which the patients were admitted were primarily located in the South and Northeast regions of the US, reflecting the regional distribution of the hospitals contained in the Premier Perspective Hospital Database.

Of the overall study population, 54.5% of patients in the powered stapler group and 51.7% of patients in the manual stapler group had a BMI between 40.0–49.9 kg/m2. Most patients had CCI scores of 2 and below (powered = 90.3%; manual = 89.9%). The most prevalent of the examined comorbidities were hypertension (powered = 57.2%; manual = 60.1%), diabetes (powered = 30.2%; manual = 33.5%), and depression (powered = 27.0%; manual = 25.5%).

Of the sub-group of patients who underwent LRY, 4,057 patients (mean age = 44.9 years; 81.0% female) were in the powered stapler group, and 9,613 patients (mean age = 45.8 years; 77.7% female) were in the manual stapler group. Of the sub-group of patients who underwent LSG, 5,794 patients (mean age = 44.5 years; 78.1% female) were in the powered stapler group, and 11,945 patients (mean age = 44.4 years; 78.3% female) were in the manual stapler group.

Unadjusted outcomes

Unadjusted outcomes are shown in . Statistical hypothesis testing was not performed for the unadjusted outcomes. Mean hospital LOS was 2.0 days for both the powered and manual stapler groups in the overall population (standard deviation = 1.5 for the powered stapler group and 1.8 for the manual stapler group). Among patients in the powered stapler group, mean total hospital costs, supply costs, and room and board costs were $11,478, $4,758, and $1,870, respectively; mean operating room time was 136.6 min, and operating room costs were $3,532. Among patients in the manual stapler group, mean total hospital costs, supply costs, and room and board costs were $13,388, $5,257, and $2,025, respectively; mean operating room time was 160.5 min, and operating room costs were $4,425.

Table 4. Unadjusted outcomes.Table Footnotea

Most patients in the powered (99.6%) or manual (98.6%) stapler groups were discharged to home or a home health organization. Among patients in the powered stapler group, 2.4% had a diagnosis or hospital billing record indicative of bleeding or a transfusion during the index admission. Among patients in the manual stapler group, 3.6% had a diagnosis or hospital billing record indicative of bleeding or a transfusion during the index admission. In the powered stapler group, 2.0% had records indicative of bleeding, and 1.6% of patients had records indicative of transfusion (1.1% had both). In the manual stapler group, 2.1% had records indicative of bleeding and 2.7% of patients had records indicative of transfusion (1.1% had both). Thirty-, 60-, and 90-day all-cause readmission rates among patients in the powered stapler group were 4.4%, 5.0%, and 5.5%, respectively. Thirty-, 60-, and 90-day all-cause readmission rates among patients in the manual stapler group were 4.7%, 5.5%, and 6.0%, respectively.

Multivariable regression-adjusted outcomes

Multivariable regression-adjusted outcomes are shown in . Among patients in the overall study population, after adjusting for differences in patient and hospital/provider characteristics, adjusted mean hospital LOS was 2.05 days (p = .981) for both the powered and the manual stapler groups. Adjusted mean total hospital costs ($12,415 vs $13,547, p = .003) and supply costs ($4,629 vs $5,217, p = .011) were statistically significantly lower in the powered vs manual stapler group. Adjusted mean operating room time, on which information was available for 92.7% of the powered staple group and 94.0% of the manual stapler group, was numerically lower in the powered vs manual stapler group, but this difference did not reach the statistical significance level (135.0 vs 151.4 min, p = .066); however, adjusted mean operating room costs were statistically significantly lower in the powered vs manual stapler group ($4,126 vs $4,413, p = .009). The adjusted proportions of patients discharged to home or a home health organization were similar (99.93% vs 99.91%, p = .575) between the powered and manual stapler groups. The adjusted proportion of patients with bleeding and/or transfusion during the index admission was statistically significantly lower in the powered vs manual stapler group (2.46% vs 3.22%, p = .025). Adjusted 30-day (4.20% vs 4.08%, p = .749), 60-day (4.68% vs 4.86%, p = .679), and 90-day (5.27% vs 5.55%, p = .569) hospital readmission rates did not differ between the powered and manual stapler groups.

Table 5. Multivariable-adjusted outcomes.Table Footnotea

Among patients who underwent LRY, after adjusting for differences in patient and hospital/provider characteristics, adjusted mean operating room costs were statistically significantly lower in the powered vs manual stapler group ($4,484 vs $4,959, p = .002). All other outcomes evaluated did not differ between the powered and manual stapler groups.

Among patients who underwent LSG, after adjusting for differences in patient and hospital/provider characteristics, adjusted mean hospital LOS did not differ between the powered and manual stapler groups (1.87 vs 1.88 days, p = .987). Adjusted mean total hospital costs ($10,708 vs $12,124, p < .001) and supply costs ($3,875 vs $4,736, p = .001) were statistically significantly lower in the powered vs manual stapler group. Adjusted mean operating room time was numerically lower in the powered vs manual stapler group, but did not reach the significance level (121.6 vs 130.5 min, p = .092); however, operating room costs were statistically significantly lower in the powered vs manual stapler group ($3,631 vs $3,871, p = .015). The proportions of patients discharged to home or home health organization were similar (100.00% vs 99.99%, p = .712) between the study groups. The proportion of patients with bleeding and/or transfusion was statistically significantly lower in the powered vs manual stapler group (1.34% vs 2.31%, p = .013). Thirty- (2.97% vs 3.13%, p = .692), 60- (3.44% vs 3.68%, p = .579), and 90-day (3.71% vs 4.11%, p = .398) hospital readmission did not differ between the powered and manual stapler groups.

Sensitivity analyses

Multivariable-regression adjusted outcomes for the sensitivity analyses comparing the Ethicon-manufactured power staplers to Medtronic-manufactured manual staplers are shown in . The results were largely consistent with the primary analyses, although the magnitude of the adjusted mean cost differences generally increased relative to the primary analyses. For example, in the primary analyses involving the overall study population, adjusted mean total hospital costs were $1,132 lower for the powered vs manual stapler group; this cost difference grew to be $1,777 lower for the Ethicon-manufactured powered vs Medtronic-manufactured manual stapler group. A few other differences were also evident, including: the loss of statistical significance on differences for operating room cost for all analyses; the loss of statistical significance on differences for bleeding/transfusion in the sub-group of patients undergoing LSG (to p = .0577); the introduction of statistical significance on differences for room and board costs for the overall study population and the sub-group of patients undergoing LSG; the introduction of statistical significance on differences for operating room time for the overall study population and the sub-group of patients undergoing LRY; and the introduction of statistical significance on differences for bleeding/transfusion and supply costs in the sub-group of patients undergoing LRY.

Table 6. Multivariable-adjusted outcomes for sensitivity analysis comparing Ethicon-manufactured powered staplers to Medtronic-manufactured manual staplers.Table Footnotea

In the powered staple group, 22.9% (overall) and 14.0% (LRY sub-group) of patients had evidence of staple line buttress use and circular stapler use, respectively; in the manual stapler group, these proportions were 14.8% and 10.3%. The sensitivity analyses examining the potential role of staple line reinforcement through buttress in the overall study population and the use of circular staplers in the sub-group of patients who underwent LRY yielded results that were highly consistent with the primary analyses in terms of both magnitude and statistical significance. The detailed results of these sensitivity analyses are shown in Supplemental Appendices 2–4.

Discussion

To our knowledge, based on a review of the literature, the present study is the first to compare economic and clinical outcomes between patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery with powered vs manual staplers. We found that, among the overall population of patients who underwent either LRY or LSG, total hospital costs, supply costs, and operating room costs were lower for the powered stapler group vs the manual stapler group. Furthermore, we found that the rate of bleeding and/or transfusions during the index hospitalization was lower for the powered stapler group vs the manual stapler group. The relative incremental clinical and economic benefits of powered staplers were more prominent among patients who had undergone LSG than among patients who had undergone LRY; although they were generally directionally consistent across the two surgical sub-groups.

Owing to the unique nature of the present study’s findings, there are currently no studies to which the findings regarding the primary objective of comparing powered vs manual endocutters can be compared. However, other prior studies examining selected outcomes that were examined in the present study have reported relatively similar overall findings. For example, in three prior longitudinal cohort studies of patients undergoing bariatric surgeries (separately representing 19,651, 28,616, and 57,918 patients) including LRYGB, LSG, and other types of bariatric surgeries, the average hospital length of stay was reported to be 2.5 daysCitation26, which is relatively similar to the 2.0 days reported in the present study. The half-day difference between the prior studies and the present study may be driven by the fact that there has been a secular trend of decreasing hospital lengths of stay over timeCitation27 and that the present study’s time period spanned 2012–2015, whereas the aforementioned studies’ time periods spanned 2004–May 31, 2013, 2007–2010, and 2007–2009. The present study’s rate of bleeding (overall, 3.2%) is also similar to what was reported in a prior meta-analysis, which reported bleeding rates between 1.2–3.5%Citation22. Furthermore, the present study’s readmission rate at 30 days (4.4%) is similar to that of prior studies (3.5–5%Citation26). Finally, in one prior single-center study examining patients undergoing LRYGB at the Stanford University Medical Center between May 2008 and November 2013, the mean operating room time ranged from 202–235 min, which is relatively similar to the present study’s mean operating room time of ∼183 min in the sub-group of patients undergoing LRYGBCitation28.

Despite the present lack of data that are directly comparable to those of the present study, the underlying hypothesis for why differences may be expected between powered and manual staplers is somewhat intuitive and may help to contextualize the present study’s findings.

Part of the benefit of the powered device (which in the present study was represented mostly by Ethicon staplers) may be derived from the combination of increased stability, along with superior control of tissue movement with advanced reloads that are available on these devices that potentially cause less damage to tissue, and help with formation of a more integrated staple-line. In benchtop testing on porcine stomach tissue, Ethicon’s powered staplers were found to reduce movement at the distal tip by 88% compared to manually-fired devices, thus potentially causing less trauma to adjacent tissue during thick transectionsCitation29. Specifically, surgeons (n = 19) fired each instrument/reload once (PSE60A/ECR60G, 030449/030459, and EGIAUSTND/EGIA60AMT); median reduction of distal tip motion was 88%, with a range of reduction of 71–95%Citation29. In pre-clinical analyses, fewer staple malformations were reported with the Ethicon’s powered stapling device compared to its non-powered version when fired on porcine small bowel specimensCitation30. Clinical studies in the US, Europe, and Asia have also demonstrated the utility of these device and reload combinationsCitation31,Citation32.

The other, more surgeon-related benefit may be derived from the speed and the procedural economy of effort which powered staplers allow in effectively executing 6–8 firings in a bariatric procedure. This may be offering the surgeon, who is required to make several decisions in each steps of the procedure, the psychological freedom to focus on the patient and to plan ahead for the next steps. Surgeons agree that improved endoscopic linear stapling device stability is a critical component of surgery and is likely to result in more frequent positive surgical outcomesCitation33. This could potentially reduce surgery stress based on the interesting theoretical framework of the biopsychosocial model (BPSM) of challenge and threatCitation34 that has been applied to explain differences in stress reaction to surgical device useCitation35. The framework is predicated upon the surgeon’s evaluation of the demands of a procedure compared against the possession or availability of necessary resources to cope effectively with such demandsCitation34. When resources are perceived to be sufficient, a “challenge” state occurs, resulting in a surgeon experiencing more favorable cognitive, affective, physiological, and behavioral outcomes. In contrast, if a surgeon perceives that she/he does not possess the resources required to meet the demands of the situation, a “threat” state emerges. It has also been shown that poor surgical performance may arise when surgeons evaluate a stressful event as a “threat” instead of a “challenge”Citation36. Differences in bleeding complication/transfusion rates could potentially be driven by this combination of device- and surgeon-driven factors that favor the use of powered endoscopic staplers.

Although we were unable to precisely pinpoint the drivers of the lower total hospital costs in the powered stapler group, the largest cost sub-category differences between the powered and manual stapler groups were observed in supply costs and operating room costs. Future analyses should attempt to understand what changes in supply requirements drive the observed lower supply costs. We observed a directionally lower, although not reaching statistical significance, operating room time for the powered stapler group, which may in part explain the lower operating room costs for the powered stapler group.

Limitations

This study was subject to limitations. First, large administrative databases containing real-world healthcare data are, in general, currently limited with respect to detailed information on medical devices. Although the development and dissemination of Unique Device Identifiers (UDI) into such databases will substantially improve the ability to study medical devices in a real-world setting, the present-day reality is that devices used within the hospital setting must primarily be identified through search of non-standardized text fields which describe the device in an electronic medical record or hospital billing system. Such search strategies may theoretically have relatively high positive predictive value for the identification of target devices; however, they may lack sensitivity to identify all instances of the use of a given device or technology. Second, as is the case with any coded healthcare database, there is a potential for measurement error or misclassification arising from codes being recorded incorrectly or incorrect recording of a given device’s usage. Third, although we used multivariable regression models to control for multiple potential confounders, as well as hospital-level clustering, laparoscopic bariatric surgical procedures are complex, and their outcomes are driven by factors which we could not measure well, including but not limited to surgeon experience, surgeon technique when utilizing a stapler, patient tissue quality and thickness, and its interplay with staple height selection, prior surgeries, and the utilization of other devices that might facilitate the procedure (e.g. advanced energy dissectors); thus, our findings cannot be interpreted as causal. When considering the measured covariates, however, magnitudes of differences between the powered and manual stapler cohorts were generally small, despite some statistically significant differences driven by the large study sample sizes. Finally, the Premier Perspective Hospital Database is a non-probability sample which may not necessarily reflect the mix of institutional and surgeon experience of all hospitals in the US or populations residing in other countries.

Conclusions

In this large-scale analysis of patients who underwent LRY or LSG, the use of powered staplers was associated with better economic outcomes and a lower rate of bleeding complication/transfusion compared to manual staplers in the real-world setting.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study and development of this manuscript was supported by Johnson & Johnson (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ).

Declaration of financial/other interests

SR and EF are employees of Ethicon, a Johnson & Johnson company. AY, SY, IK, and SJ are employees of Johnson & Johnson. CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental_Material.docx

Download MS Word (19.9 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Jay Lin and Melissa Lingohr-Smith from Novosys Health for editorial support and review of this manuscript.

References

- Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, et al. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 2016;315:2284-91

- Buchwald H, Consensus Conference Panel. Consensus statement: Bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: health implications for patients, health professionals, and third-party payers. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2005;1:371-81.

- Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C. The medical care costs of obesity: an instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ 2012;31:219-30

- Apovian CM. The clinical and economic consequences of obesity. Am J Manag Care 2013;19 (Suppl11):S219-S28

- Spieker EA, Pyzocha N. Economic impact of obesity. Prim Care 2016;43:83-95

- Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient-2013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Endocr Pract 2013;19:337-372

- Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care 2016;39:861-77

- Khan S, Rock K, Baskara A, et al. Trends in bariatric surgery from 2008 to 2012. Am J Surg 2016;211:1041-6

- Nguyen NT, Masoomi H, Magno CP, et al. Trends in use of bariatric surgery, 2003–2008. J Am Coll Surg 2011;213:261-6

- Hinojosa MW, Varela JE, Parikh D, et al. National trends in use and outcome of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2009;5:150-5

- Esteban Varela J, Nguyen NT. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy leads the U.S. utilization of bariatric surgery at academic medical centers. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015;11:987-90

- PR Newswire. Ethicon Endo-Surgery introduces first powered endocutter with enhanced system-wide compression and stability, allowing surgeons greater control in laparoscopic surgery. Chicago, IL: Cision. September 27, 2011. http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/ethicon-endo-surgery-introduces-first-powered-endocutter-with-enhanced-system-wide-compression-and-stability-allowing-surgeons-greater-control-in-laparoscopic-surgery-130591488.html Accessed November 15, 2016

- Bariatric Times. Health D. Complications arising from staple lines and anastomotes in bariatric surgery: why they happen and how to avoid them. November 17, 2009. http://bariatrictimes.com/complications-arising-from-staple-lines-and-anastomotes-in-bariatric-surgery-why-they-happen-and-how-to-avoid-them/ Accessed November 15, 2016

- Han SH, Gracia C, Mehran A, et al. Improved outcomes using a systematic and evidence-based approach to the laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in a single academic institution. Am Surg 2007;73:955-8

- Carrasquilla C, English WJ, Esposito P, et al. Total stapled, total intra-abdominal (TSTI) laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: one leak in 1000 cases. Obes Surg 2004;14:613-7

- Business Wire. Covidien Receives FDA 510(k) Clearance for the iDrive™ Powered Stapling System. San Francisco, CA: Business Wire December 2, 2010. http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20101202005177/en/CovidienMedtronic-Receives-FDA-510-Clearance-iDrive%E2%84%A2-Powered. Accessed November 15, 2016

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases, J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613-9

- Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ 2001;20:461-94

- Park RE. Estimation with heteroscedastic error terms. Econometrica 1996;34:888

- Rosenthal RJ; International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel, Diaz AA, et al. International sleeve gastrectomy expert panel consensus statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2012;8:8-19

- Berger ER, Clements RH, Morton JM, et al. The impact of different surgical techniques on outcomes in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies: the first report from the metabolic and bariatric surgery accreditation and quality improvement program (MBSAQIP). Ann Surg 2016;264:464-73

- Shikora SA, Mahoney CB. Clinical benefit of gastric staple line reinforcement (SLR) in gastrointestinal surgery: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2015;25:1133-41

- Stroh C, Köckerling F, Volker L, et al. Results of more than 11,800 sleeve gastrectomies: data analysis of the German bariatric surgery registry. Ann Surg 2016;263:949-55

- Schneider R, Gass JM, Kern B, et al. Linear compared to circular stapler anastomosis in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass leads to comparable weight loss with fewer complications: a matched pair study. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2016;401:307-13

- Stroh CE, Nesterov G, Weiner R, et al. Circular versus linear versus hand-sewn gastrojejunostomy in Roux-en-Y-gastric bypass influence on weight loss and amelioration of comorbidities: data analysis from a quality assurance study of the surgical treatment of obesity in Germany. Front Surg 2014;1:23

- Coleman KJ, Huang YC, Hendee F, et al. Three-year weight outcomes from a bariatric surgery registry in a large integrated healthcare system. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2014;10:396-403

- Weiss AJ (Truven Health Analytics), Elixhauser A (AHRQ). Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #180. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; October 2014. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180 Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2016

- Sanford JA, Kadry B, Brodsky JB, et al. Bariatric surgery operating room time–size matters. Obes Surg 2015;25:1078-85

- Data on file. PRC048941: AMP Claims testing completion report. Ethicon. Somerville, NJ 2012

- Kimura M, Terashita Y. Superior staple formation with powered stapling devices. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2016;12:668-72

- Licht PB, Ribaric G, Crabtree T, et al. Prospective clinical study to evaluate clinical performance of a powered surgical stapler in video-assisted thoracoscopic lung resections. Surg Technol Int 2015;27:67-75

- Qiu B, Yan W, Chen K, et al. A multi-center evaluation of a powered surgical stapler in videoassisted thoracoscopic lung resection procedures in China. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:1007-13

- Miller D, Gonzalez Rivas D, Meyer KL, et al. The impact of endoscopic linear stapling device stability in thoracic surgery: A Delphi panel approach. JHEOR 2015;3:73-82

- Blascovich J, Seery MD, Mugridge CA, et al. Predicting athletic performance from cardiovascular indexes of challenge and threat. J Exp Soc Psychology 2004;40:683-8

- Roy S, Hammond J, Panish J, et al. Time savings and surgery task load reduction in open intraperitoneal onlay mesh fixation procedure. Sci W J 2015;2015:340246

- McGrath JS, Moore L, Wilson MR, et al. ‘Challenge’ and ‘threat’ states in surgery: implications for surgical performance and training. BJU Int 2011;108:795-6