Abstract

Background: Cost-related non-adherence (CRN) to medical care is a persistent challenge in healthcare in the US. Gender is a key determinant of many healthcare behaviors and outcomes. Understanding variation in CRN by gender may provide opportunities to reduce disparities and improve outcomes.

Aims: This study aims to examine the differential rates in CRN by gender across a spectrum of socio-economic factors among the adult population in the US.

Method: Data from the 2015 National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) were used for this study. CRN is identified if a respondent indicated not filling a prescription for medicine because of the cost and/or skipping a medical test, treatment, or follow-up recommended by a doctor because of the cost in the past 12 months. The differential rates in CRN by gender were assessed across socio-economic strata. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the difference in CRN rates by gender, controlling for potential confounders.

Results: A total of 26,287 adults were included in the analyses. Overall, the weighted CRN rate in the adult population is 19.8% for men and 26.2% for women. There was a clear pattern of differential rates in CRN across socio-economic strata by gender. Overall, men were less likely to report CRN (AOR = 0.74; 95% CI = 0.69–0.79), controlling for other risk factors.

Conclusions: More research is needed to understand the behavioral aspects of gender difference in CRN. Patient-centered healthcare needs to take gender difference into account when addressing cost-related non-adherence behavior.

Introduction

The cost barrier to healthcare is a persistent challenge in the USCitation1–3. Even with health insurance coverage, millions of Americans are still constantly struggling between meeting the basic needs of daily life and the financial cost of maintaining adherence to medical careCitation4,Citation5. Often, when individuals are in financial distress, they forgo necessary medical care to avoid costs. Hence, measuring cost-related non-adherence (CRN) to medical care provides a meaningful, broad gauge of access barriers beyond insurance coverage. Gender is a key determinant of many healthcare behaviors and outcomes. Understanding variation in CRN by gender may provide opportunities to reduce disparities and improve outcomes.

There is robust discussion in the literature regarding sex differences in the use of healthcare resources across the life span, and the role of gender in driving such differences in medical resource utilization when socio-economic contexts are incorporated in medical careCitation6–8. Research has found that expenditures for healthcare are similar for male and female subjects after differences in reproductive biology and higher age-specific mortality rates among men have been accounted forCitation9. However, little is known about if men and women respond differently when faced with economic constraints, in terms of non-adherence to medical care. This is important, because delay or avoidance of treatment may result in foregone opportunities for care, elevated downstream economic costs, and worse health outcomesCitation10–12. More importantly, the differential rates in CRN by gender may even drive the disparities higher and make health outcomes worse. There is some literature suggesting such a difference by gender in a narrowly defined medication use (i.e. non-adherence to medication only) among the elderly Medicare population and cancer survivorsCitation13–15, yet no empirical evidence is available on non-adherence in medical care more comprehensively defined (i.e. non-adherence to medication and other medical tests, treatments, and follow-up recommended by a doctor) and in the general population.

There is very limited understanding of the gender differences in cost-related non-adherence to medical care, as literature on non-adherence in general do not distinguish cost-related non-adherence from those due to side-effects, cultural factors, or personal belief about the effectiveness of treatments, and the literature on cost-related non-adherence often focuses on a specific sub-population such as cancer patients or elderly, and an examination of the general adult population by gender in this regard has not been previously carried out. While a difference in CRN due to sex would be limited to biological differences such as genitalia and sex-linked chromosomes, gender differences also include psychological, behavioral, and social factors. Since CRN is a behavior shaped by many forces, gender provides a more complex explanation of variation than sex aloneCitation16. Furthermore, gender inequality in access to healthcare is strongly influenced by health policy. For example, the Affordable Care Act specifically requires the coverage of “essential health benefits”, including reproductive health. An increased focus on gender disparities could help improve population health and, in the absence of existing protections, the gender inequality could further increase.

We therefore propose to evaluate if gender influences cost-related non-adherence to medical care, using a national sample of the US adult population. We hypothesize a gender difference in CRN across the strata of patients’ age, household income, care burden for financially dependent children, and status as permanently sick, disabled, or unable to work, respectively. We aim to examine such a difference across the age spectrum of the entire adult population in the US.

Methods

Data and cost-related non-adherence to medical care

Data from the 2015 National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) were used for this study. NFCS is a survey of more than 25,000 US adults commissioned by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) Investor Education Foundation in consultation with the US Department of the Treasury and President Bush’s Advisory Council on Financial Literacy, with the overarching research objectives to benchmark key indicators of financial capability and evaluate how these indicators vary with underlying demographic, behavioral, attitudinal, and financial literacy characteristics. The sample consisted of 27,564 adults (18+) across the US, with ∼500 respondents per state, plus the District of Columbia. Respondents were drawn using non-probability quota sampling from established online panels consisting of millions of individuals who were recruited to join, and who were offered incentives in exchange for participating in online surveys. Specifically, the panels used for this survey were provided by SSI (Survey Sampling International), EMI Online Research Solutions, & Research Now. These panels use industry-standard techniques to verify the identities of their panel members and to ensure that their demographic characteristics are valid and up-to-date. While it is possible that more than one person in one household could have been drawn into the sample of 500 respondents in each state, the likelihood of such an event is very small, and, hence, should not present a significant threat to the validity of this study of individuals. The national weight is provided by NFCS to be nationally representative per Census distributions, based on data from the American Community SurveyCitation17. We used such weight from NFCS to obtain the weighted CRN rates for men and women, respectively.

NFCS has a set of questions on: (a) “In the last 12 months, was there any time when you did not fill a prescription for medicine because of the cost?”, and (b) “In the last 12 months, was there any time when you skipped a medical test, treatment, or follow-up recommended by a doctor because of the cost?”. CRN is identified if a respondent indicated “yes” to either of these two questions. This question is specific to the individual’s service use and not more broadly for other healthcare that the respondent may be responsible for (e.g. a child’s healthcare).

Socio-economic strata

NFCS specifically asked the respondent to identify their gender. The main interest of this study is to explore the socio-economic contexts of CRN beyond the notion of biological sex: that is, the behavioral aspects CRN differences between men and women in each of the socio-economic strata. NFCS categorized age into six strata: 18–24; 25–34; 35–44; 45–54; 55–64; and 65+. NFCS also includes information on household income: “What is your [household’s] approximate annual income, including wages, tips, investment income, public assistance, income from retirement plans, etc.?” NFCS includes information on individual respondents’ educational attainment: “What was the highest level of education that you completed?” There were possible answers: Did not complete high school; High school graduate—regular high school diploma; High school graduate—GED or alternative credential; Some college, no degree; Associate’s degree; Bachelor’s degree; and Post-graduate degree; Prefer not to say. All respondents reported educational attainment in the NFCS. We derived indicator variables for income and educational attainment directly from the survey, and all respondents reported household income and educational attainment in the survey question.

Other covariates

We included a number of covariates in our multivariable regression analysis, including race, marital status, health insurance status, and financial capabilities to manage monthly expenses, to control for potential confounding. NFCS has a binary variable indicating if the respondent is a white or non-white. NFCS categorizes marital status into five categories: Married; Single; Separated; Divorced; Widowed/widower; all respondents reported a marital status. We included the marital status as a co-variate in the multivariable regression analysis, because a burgeoning literature suggests that marriage may have a wide range of effects on healthCitation18, although the specific effect of marriage on non-adherence behaviors has not been systematically examined. We also hypothesized that the number of financially dependent children might influence CRN, due to the disproportionate care burden borne by women, and hence needs to be adjusted for as well: that is, gender-based differences such as a possible motivation to reduce one’s own medical consumption to meet the needs of financially dependent children. BFCS has a question on “How many children do you have who are financially dependent on you [or your spouse/partner]?” The possible answers are 1; 2; 3; 4 or more; No financially dependent children; and Do not have any children.

NFCS has a question on respondent’s health insurance coverage: “Are you covered by health insurance?” The respondents can choose from: Yes; No; Don’t know; and Prefer not to say. NFCS also asks about the respondent’s ability to cover monthly expenses: “In a typical month, how difficult is it for you to cover your expenses and pay all your bills?” The possible answers are very difficult; somewhat difficult; not at all difficult; don’t know; and prefer not to say. We included this variable in the multivariable regression analysis because financial capability in managing monthly bills reflects closely financial distress and, hence, should be adjusted for in order to ascertain the gender effect beyond economic means: Those who responded with “don’t know” or “prefer not to say” for these two questions were dropped from the subsequent analyses. Finally, we created an indicator variable for those who reported “permanently sick, disabled, or unable to work” when they were asked about “which of the following best describes your current employment or work status?” We think this is an important indicator variable, because it separates those who were severely sick or disabled from those who are relatively healthy, and can reveal if the gender difference is robust across health status.

A total of 27,564 adults were included in the 2015 NFCS. Three-hundred and ninety (1.4%) respondents indicated “Don’t know” or “Prefer not to say” in response to the question of health insurance, and an additional 497 (1.8%) respondents, who indicated “Don’t know” or “Prefer not to say” to the question of difficulty in covering expenses and paying monthly, were also dropped in the subsequent analyses. For the remaining 26,677 respondents, 260 (1%) respondents indicated “Don’t know” or “Prefer not to say” to the question to not filling a prescription for medicine because of the cost, and 304 respondents to the question of skipping a medical test, treatment, or follow-up recommended by a doctor because of the cost were also dropped from the subsequent analyses, resulting in a final sample of 26,287 adults, as some respondents elected not to answer either question.

Statistical analysis

We hypothesized a gender difference in CRN across the strata of socio-demographic variables, and hence calculated the mean and 95% Confidence Interval of the mean of CRN rates in each stratum for men and women, respectively. We also measured CRN rates across the age strata by gender and a nationally weighted CRN rate, using the full sample weight in the NFCS for men and women, respectively. Since age, household income, and number of financially dependent children measure different constructs of socio-economic status, and our objective is not to identify the strongest factors influencing CRN but rather if men and women differ in CRN across those strata, we think it is proper to perform those bi-variable comparisons. To address potential confounding and overlapped effect by those variables, we further conducted a multivariable regression analysis of CRN using gender as the predictor, controlling for age, household income, educational attainment, race, marital status, number of financially dependent children, health insurance coverage, ability to cover monthly expenses, and permanent sick/disabled/unable to work, using a logit model. The main variable of interest of this study is the gender difference in CRN. All other variables are used to address the potential confounding of the gender effect. To further ascertain the gender difference in CRN, we performed stratified analysis for those who reported permanently sick/disabled/unable to work, and those who did not, respectively, using the same set of aforementioned covariates in the logistic regression models. Statistical significance level was set at 0.05. All analyses were performed using Stata 14 software (Stata, College Station, TX, 2015).

Results

shows the CRN socio-economic distribution of the respondents by men and women, respectively. Overall, 8% of men were in a household with annual income >$150k vs 5% of women, while 17% of men had post-graduate degrees vs 12% of women. Thirty percent of men were single, compared to 27% of women, while 8% of men reported it was “very difficult” to pay monthly bills, in contrast to 12% of women. Among men, 472 (4%) reported that they were permanently sick/disabled/unable to work, while 703 (5%) women reported such a status.

Table 1. CRN across socioeconomic stratum by gender.

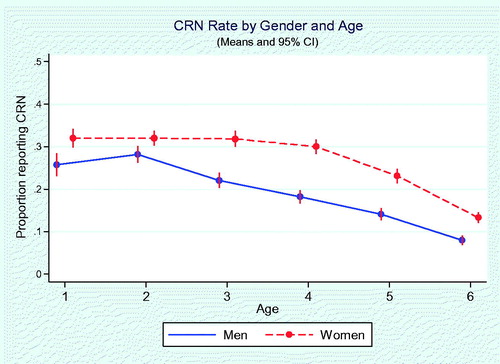

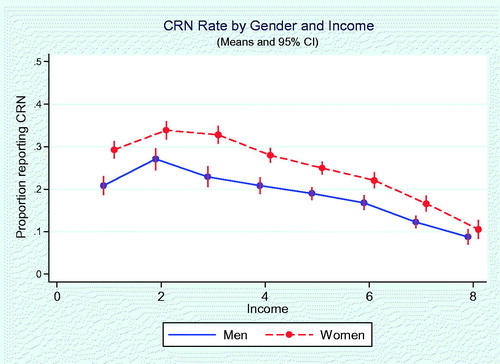

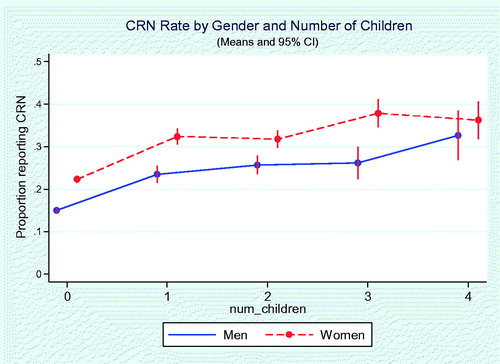

There was a clear pattern of gender difference in the CRN rates across the strata of age (), household income (), and number of financially dependent children (). Women had higher CRN rates across those strata. Higher income was in general associated with lower CRN rates; however, those in the lowest income brackets (annual household income <$15,000) reported lower CRN rates, equivalent to that reported by respondents in the income bracket of at least $35,000 but less than $50,000. The unadjusted CRN prevalence rates for men and women were 18.5% and 26.5%, respectively. By weighting, national CRN prevalence rates were 19.8 for men and 26.2% for women (data not shown).

Figure 1. Cost-related medication non-adherence by gender and age. Age groups: 1, 18–24; 2, 25–34; 3, 35–44; 4, 45–54; 5, 55–64; 6, 65+. Error bars represent 95% CIs. CRN rates (the proportion of those who report CRN) were indicated vertically.

Figure 2. Cost-related medication non-adherence by gender and household income. Household income: 1, Less than $15,000; 2, At least $15,000, but less than $25,000; 3, At least $25,000, but less than $35,000; 4, At least $35,000, but less than $50,000; 5, At least $50,000, but less than $75,000; 6, At least $75,000, but less than $100,000; 7, At least $100,000, but less than $150,000; 8, $150,000 or more. Error bars represent 95% CIs. CRN rates (the proportion of those who report CRN) were indicated vertically.

Figure 3. Cost-related medication non-adherence by gender and number of financially dependent children. Number of children was defined as the number of financially dependent children, with 0 as no child or no financially dependent child. Error bars represent 95% CIs. CRN rates (the proportion of those who report CRN) were indicated vertically.

shows the results from the multivariable logistic regression analysis, including adjusted odds ratios with respect to the indicated reference groups. Overall, the younger the adults were, the more likely they reported CRN, with those aged >65 least likely to report CRN. Those with household income <$15 k reported lower CRN. Higher educational attainment was not associated with lower CRN rates. Compared to those who were married, the multivariable logit model showed that those who were single were less likely to report CRN (AOR = 0.79; 95% CI = 0.72–0.87). Having one or more financially dependent children significantly increased the likelihood of CRN. Overall, men were less likely to report CRN (AOR = 0.74; 95% CI = 0.69–0.79), after controlling for age, race, educational attainment, household income, marital status, number of financially dependent children, health insurance coverage, and difficulty in paying monthly bills. The area under ROC curve (C statistic) was 0.75, indicating the overall performance of the model in discriminating the CRN is reasonableCitation19.

Table 2. Associations between socio-demographic variables and cost-related non-adherence to medical care.

In stratified analyses, men were less likely to report CRN (AOR = 0.75; 95% CI = 0.57–0.99) among those who reported permanently sick/unable to work/disabled; similarly, men were less likely to report CRN (AOR = 0.74; 95% CI = 0.69–0.79) among those who did not report that they were permanent sick/unable to work/disabled (data not shown).

Discussion

Clearly, there is a gender difference in CRN across socio-economic strata as women reported higher CRN rates, even controlling for age; household income; status as permanently sick, disabled, or unable to work; number of financially dependent children; and difficulty in managing monthly bills. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 mandates essential health benefits, including maternity care and coverage without cost sharing for preventive services such as contraceptives, as well as prohibits charging women more than men for the same plan, measures designed to address gaps and inequities in women’s health insuranceCitation20. However, this data, collected in 2015, demonstrates that the gender gap in the cost barrier to healthcare persists. To the best of knowledge, this is the first study that examines the differential rates in CRN by gender across the entire spectrum of adulthood in the US, comprehensively defined. The results suggest that gender is a strong force in driving the behaviors in non-adherence to medical care due to costs. CRN behaviors have been less frequently examined in the international setting, and this study suggests that there may be opportunity to address gender disparity in healthcare by examining such a dimension in cost-related behaviors in non-adherence.

It is also noteworthy that financial barriers to healthcare lead to worse outcomes. For example, studies have found that women experienced more financial barriers than men among patients with acute myocardial infarction, and such financial barriers were associated with worse mental functional status, greater depressive symptomatology, lower quality-of-life, and higher perceived stress, although the causal path of such an association was less clearCitation21,Citation22. Our study provides further evidence that such a gender gap in financial barriers is broad and consistent across age, income, number of financially dependent children, and disability status. This places tremendous value on the protection women need against financial distress, and grave consequences if such protection diminishes.

This study also demonstrated that, across the spectrum of the number of financially dependent children, women had higher CRN rates. Such disproportionate care burden borne by women, while potentially inherent in motivating cost-cutting in medical care by women, needs to be adjusted for to further understand the gender difference in CRN behaviors. Lower- middle-income women are not eligible for Medicaid assistance, because they are not poor enough. Despite of the provision by ACA, 19 states elected not to expand MedicaidCitation23. It is important that policymakers be acutely aware of the negative impact to women’s health and social welfare by failing to provide adequate financial protection for them. Future research and health/social policy should target these populations to improve the overall wellbeing of women.

This study also has broad implication for health and social policy. For example, it suggests that the gender gap in financial barrier is across the entire spectrum of life cycle, despite the Medicare program, which provides low-cost medical care to the elderly including a Part D prescription drug program. Since women live longer, but with more morbidities than men in old age, this is particularly concerning, as health and financial distresses converge when they are at the most difficult point of their lives. As baby boomers continue to age and, given that a disproportionate percentage of the elderly are women, the gender gap in financial barriers to medical care may only become more pronounced. More research is much needed to understand this access barrier in the later stage of life.

This study also shows that, for the entire adult population, those who are at the end of the lowest income category (household income <15 k) and the elderly (≥ 65 years old) had lower CRN rates compared to others in the same socio-economic strata. This is encouraging in that Medicaid and Medicare, which help the very poor and the elderly to pay for their medical care, may have worked in addressing CRN. This is also in line with the finding that those without health insurance (i.e. neither public insurance nor private health insurance) are much more likely to report CRN. Insurance coverage plays a critical role in combating the expensive drug costs, and in the light of potential repeal of the ACA, policymakers need to have acute awareness of consequences if millions of Americans lose their insurance coverage.

This study also has important implications for clinical practice. For example, research has found that a lack of communication about drug costs has been an important barrier to reducing CRNCitation24. It is unclear if a gender gap exists in patient–physician communication. Given the heterogeneity in healthcare needs between women and men, and among different life stages for women, it is imperative to understand that a gender-conscious approach can be developed to improve provider–patient communication and, thereby, reduce CRN.

There is a series of discussions in the literature on gender differences in seeking healthcare, stemming from differential social roles, psychological distress, and why rational people are not effective in making health a priority in their everyday livesCitation6–8. However, there is no systematic discussion yet on the gender difference in non-adherence behavior. It is possible that women are more sensitive to out-of-pocket payments of medical care, and, hence, is more likely to be non-adherent, as women have lower wage income than men, all other things being equal, the relative costs of medical care are higher than men. Future research should also address if women may have different perception of medication effectiveness. The literature has argued that the social role of women may be more stressful than that of menCitation7,Citation8, and hence the morbidity is a more acceptable norm among women. In this light, it may be possible that, as women reported a higher degree of morbidity, they may also exhibit a higher degree of tolerance to non-adherence. Thus, it may also be more effective to consider a gender-conscious intervention strategy to reduce CRN based on the above insights.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, patients can be engaged with one or more CRN behaviors, such as not filling a prescription for medicine, skipping a medical test, treatment, or follow-up recommended by a doctor because of the cost simultaneously or sequentially in the given year. Unfortunately, NFCS does not give an indication of the frequency of such CRN behaviors. Future research should be directed to the frequency and intensity of CRN behaviors to ascertain those who have multiple CRN behaviors for targeted intervention. It is also possible that, since the CRN variable in this study is based on the respondent’s perception that the needed filling a prescription for medicine, a medical test, treatment, or follow-up recommended by a doctor can be foregone due to costs, the respondent may believe some of the recommended medication or procedures may not be effective or even not necessary. The judgment of medical necessity is beyond the scope of this study. Future research should be directed to ascertaining the areas that CRN may mostly affect patients’ health negatively.

Second, we are not able to derive a detailed causal path of the gender gap as a financial barrier, since data on specific disease burden such as chronic conditions was not available in NFCS. It is likely that CRN rates will vary across those chronic conditions when comparing men vs women. However, we adjusted for those who self-reported that they were permanently sick, disabled, or unable to work, and the results are robust, indicating that the gender difference in CRN is a social phenomenon beyond biological health, as the decision to adhere or not to adhere is determined not only by medical needs, but also by economic means, as well as other social factors such as overall responsibilities in the household and social expectations. In addition, the breakdown of the income variable and the categorical age variable acted as proxies for Medicaid insurance coverage for those poor and Medicare insurance coverage for those who were 65 years or older, and the results are indicative that the Medicaid and Medicare programs were protective for those who are very poor and those who are elderly, resulting relatively lower CRN rates across the socio-economic strata. We also included an indicator variable of difficulty in managing monthly bills, as, while both income and health insurance coverage are enabling factors for medical services use, it ultimately comes down to the bottom line of paying the monthly bills. In addition, the disease burden may affect women differently from men at different life stages and at different socio-economic strataCitation9, and such a life course approach based on the differential needs of women’s health in different life stages is well beyond the scope of this study. However, more research is needed to further investigate the complex role of gender in non-adherence.

Third, the gender difference in healthcare-seeking behavior may also be a factor as it’s possible that perceived cost or benefit of seeking healthcare differs between men and women, leading to differences in the number and type of healthcare interactions, and should be explored by future research.

Fourth, this is a cross-sectional study, and hence the investigation in how changes in socio-economic status influences non-adherence in women vs men is not possible. More research in this front will illuminate the dynamics of gender’s role in non-adherence.

Fifth, NFCS uses an online survey mechanism, and, hence, those who are on a lower rung of the income ladder and do not have internet access could be under-represented. However, the weights provided by NFCS allow the respondents to be representative of Census distributions according to the American Community Survey when generating national estimatesCitation17. In addition, the large sample allows for comparison of the gender difference across socio-economic strata. Nevertheless, more research is needed to refine the results, especially small area variations such as medical needs, economic means, and willingness to pay, that vary by geographic region.

Sixth, we did not carry out various interaction analyses across gender, age, race, health, marital status, and burden of financially dependent children. Such interactions are important for understanding complex human behaviors, while many sources of distress converge, and our multivariable regression analysis shows that those who are with lower-middle income and multiple financially dependent children are at the highest risk of CRN. However, a detailed examination of such interactions is beyond the scope of this study, and future research in this front can yield more insight in targeting those high-risk sub-populations. Moreover, the purpose of covariates in the multivariable regression analysis is to address the potential confounding of gender effect due to other factors. The fact that we found that many of those covariates are statistically significant in the regression results indicate that these are independent risk factors for CRN, and the gender effect is robust. Nevertheless, caution is warranted to interpret those covariates, as multicollinearity may exist, and hence their gross and net effect size may differ when assessed with and without other covariates.

Seventh, while racial difference is not the focus of this study, we controlled for white vs non-white in the multivariable regression analysis. It is noteworthy that non-white women have slightly higher rates of CRN than white women in the unadjusted data, and such a difference is not statistically significant in the adjusted results. Future research should to directed to more detailed examination of CRN rates for minority groups such as Asian Americans, and Asian Pacific Islanders.

Lastly, while we have shown the gender difference in CRN by controlling a broad set of covariates including the permanent disabilities and number of financial dependent children, we are not able to control for the household role by gender. Given the rising number of women as the head of the household, it’s even more pressing to advance the study of gender difference in CRN, as households with women as the head may have very different financial profiles, and hence high cost barriers to healthcare.

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated a clear pattern of gender differences in non-adherence across socio-economic strata. Such a gender difference is beyond the impact of advancing age, household income, or care burden for financially dependent children. Given that existing protections for women’s health in the ACA are in peril, it is important to note the current state and the potential consequences of removing such protections. This study contributes to the knowledge base of the importance of gender dynamics in cost-related non-adherence behavior, and calls for a more gender-conscious approach to assess the socio-economic impact on interventions to address unmet medical needs. The gap between the knowledge and needed policy action seems to be large, and further research is much needed to understand those factors and to reduce the gender disparity in cost-related non-adherence to medical care, especially for those who are low-income and economically vulnerable.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of financial/other interests

None of the authors have any potential financial conflict of interest. JXZ and JMC have an ownership interest in Chicago MedInfo Group, LLC. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgement

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of our manuscript and detailed comments.

References

- Sommers BD. Health care reform’s unfinished work—Remaining barriers to coverage and access. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2395-7

- Wilensky GR. Improving and refining the Affordable Care Act. JAMA 2015;314:339-40

- Dorner SC, Jacobs DB, Sommers BD. Adequacy of outpatient specialty care access in marketplace plans under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA 2015;314:1749-50

- Madden JM, Graves AJ, Zhang F, et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence and spending on basic needs following implementation of Medicare Part D. JAMA 2008;299:1922-8

- Naci H, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Medication affordability gains following Medicare Part D are eroding among elderly with multiple chronic conditions. Health Aff 2014;33:1435-43

- Macintyre S, Hunt K, Sweeting H. Gender differences in health: are things really as simple as they seem? Soc Sci Med 1996;42:617-24

- Rieker PP, Bird CE. Rethinking gender differences in health: why we need to integrate social and biological perspectives. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2005;60:40-7

- Nathanson CA. Illness and the feminine role: a theoretical review. Soc Sci Med 1975;9:57-62

- Mustard CA, Kaufert P, Kozyrskyj A, et al. Sex differences in the use of health care services. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1678-83

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M. Medication costs, adherence, and health outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff 2003;22:220-9

- Heisler M, Langa KM, Eby EL, et al. The health effects of restriction on prescription medication use because of cost. Med Care 2004;42:626-34

- Iuga AO, McGuire MJ. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manag Healthcare Policy 2014;7:35-44

- Soumerai SB, Pierre-Jacques M, Zhang F, et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence among elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries: a national survey 1 year before the medicare drug benefit. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1829-35

- Zhang JX, Meltzer DO. Risk factors for cost-related medication non-adherence among older patients with cancer. Integr Cancer Sci Ther 2015;2:300-4

- Lee M, Khan MM. Gender differences in cost-related medication non-adherence among cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2016;10:384-93.

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th Edition. Washington, DC: APA; 2013. p 16

- FINRA Investor Education Foundation. About the National Financial Capability Study. Washington, DC, 2016. http://www.usfinancialcapability.org/about.php. Accessed September 4, 2016

- Office of the Assistant Sectary of Planning (ASPE), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The effects of marriage on health: a synthesis of recent research evidence. Research Brief. Washington, D.C. 2007. https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/effects-marriage-health-synthesis-recent-research-evidence-research-brief. Accessed September 5, 2016

- Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr. Evaluating discrimination of risk prediction models: the C statistic. JAMA 2015;314:1063-4

- Salganicoff A, Ranji U, Beamesderfer A, et al. Women and health care in the early years of the ACA: key findings from the 2013 Kaiser Women’ Health Survey. http://kff.org/womens-health-policy/report/women-and-health-care-in-the-early-years-of-the-aca-key-findings-from-the-2013-kaiser-womens-health-survey. Accessed November 21, 2016

- Beckman AL, Bucholz EM, Zhang W, et al. Sex differences in financial barriers and the relationship to recovery after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e003923

- Rahimi AR, Spertus JA, Reid KJ, et al. Financial barriers to health care and outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2007;297:1063-72

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. The coverage gap: Uninsured poor adults in States that do not expand Medicaid. http://kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/. Accessed March 27, 2017

- Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Tseng CW, et al. Barriers to patient–physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:856-60