Abstract

Background: Global budget (GB) is considered one of the most important payment methods available. Since a new round of healthcare system reforms in 2009, the Chinese government has been paying attention to this prospective payment. However, it is unclear whether GB has influenced cost control and how it works in rural China.

Methods: YC county was chosen as the intervention group, with 33,175 inpatients before and 36,883 inpatients after the reform (2012 and 2014, respectively). ZJ county acted as the control group, with 23,668 and 29,555 inpatients, respectively. The inpatients’ information was collected from a local insurance agency. The difference-in-difference method (controlling for age, gender, living status, severity of the disease, whether the patient had surgery, the level of medical institutions, and the secular trends of the two groups) was applied to estimate the effects on total spending (TS), reimbursement expense (RE), out-of-pocket payment (OOP), readmission rate, and seven kinds of medical service items.

Results: At per practice level, the GB was associated with a ¥263.35 (p < .001) and ¥447.46 (p < .001) decrease in growth of TS and RE, respectively, while OOP increased by ¥188.06 (p < .001). At per capital level, the decrease in growth of TS and RE was ¥64.39 (p = .301) and ¥467.45 (p < .001), respectively, whereas the increase of OOP was more significant at ¥408.19 (p < .001). Savings were concentrated in unclassified items (¥197.68, p < .001), drug prescription (¥69.03, p < .001), surgery (¥40.18, p < .001), cure (¥4.95, p = .565), and diagnosis (¥3.61, p = .064). Meanwhile, the readmission rate increased by 11.4% (p < .001).

Conclusions: The GB has a prominent impact on curbing the growth of insurance fund expenditures, as well as drug and medical consumable costs. However, the patients’ out-of-pocket payment has risen. Doctors decomposed hospitalization to deal with supervision, which was harmful to patients. Any medical insurance payment reform should be undertaken prudently, and its likely outcomes should be weighed comprehensively.

Introduction

Troubled by the rapid and inexorable growth of health expenditures, many countries began to explore cost containment strategies in the late 1970sCitation1. Abel-Smith’sCitation2 major conclusion showed that the regulation of the supplier side, especially by using budgets to hospitals, is technically feasible to control healthcare costs. After years of exploration, the global budget (GB) has been recognized as a popular cost-control solution around the worldCitation3. The annual growth rate of healthcare expenditure in China was 12.5% from 1993–2012, much higher than the 9.9% economic growth rate of the same periodCitation4. This difference undoubtedly puts pressure on the patients and the health insurance fund. Although the proportion of out-of-pocket payment (OOP) was showing a downward trend, it still accounted for 34.34% of the annual growth rate of total spending (TS) in 2012. A high OOP ratio will lead to “catastrophic health expenditure”, which would prevent residents from seeking healthcare properlyCitation5–7. Since the Health Care Reform in 2009, the Chinese government has begun to explore payment reform, giving priority to prospective payment. The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security released “Opinions Regarding the Implementation of Total Expenditure Control of the Basic Medical Insurance” in 2012, which asked provinces to reform the payment of health insurance, and try to carry out GBCitation8.

There are three categories which aim to hold actual healthcare spending within global budget target: curtail premiums, limiting prices, or confining provider’s budgetsCitation9. In China, most GB types belong to the last categoryCitation10–12, which allocates the entire insurance fund pool to each medical institution, based on historical spending and activities. Allocating the total compensation funds to a single agency goes against “the law of large numbers”Citation13 of medical insurance, and may be detrimental to the patients’ treatment effect, because of excessive emphasis on the control of costs.

The primary aim of GB is to control expenditure, hence previous research focused on the effect of controlling costs, and their consistently drawn conclusion indicates that GB payment was successful in slowing down expenditure growthCitation14–16. However, the effective containment of cost increases does not equal better hospital performance. The greatest risk of global budget involves responsibility-shifting behaviors, which include undertreatment of admitted patients, reduction in the number of admissions, and admitting the cheapest casemix possibleCitation17. Some studies shifted attention to the effect on quantity and quality of medical services, and the supplier’s responsesCitation18. Most of the researches showed that the implementation of GB could not improve qualityCitation19; furthermore, the cost containment might trigger a trade-off effect: expenditure saving comes at the price of service qualityCitation20. In terms of quantity, researches came to varied results due to the particularity of the environment, differences in reimbursement mechanism, and the target of evaluation. For example, evidence of the reform in Massachusetts revealed that GB did reduce service utilizationCitation14, but had no significant effect on the use of drugsCitation21. However, evidence in Taiwan showed that GB increased treatment intensityCitation22, which included drug utilizationCitation23. Therefore, we cannot predict the effects of GB in rural China based on previous studies. Before starting analysis, the first thing we must clarify is that the priority of medical care is to offer high-quality service with reasonable prices. Any reform cannot violate this principle.

In China, rural residents total to 603.46 million, representing 43.90% of the entire population. Medical resources and skills in rural areas are lower than they are in the cityCitation24. Residents also face traffic and economic barriers when they seek medical servicesCitation25. Regardless of their area of residence, patients have the right to enjoy equal access to healthcare, based on their needs. Hence, the situation of rural medical services provision is pivotal to the whole healthcare system. Rural health expenditure is also suffering a rapid rise, increasing by 2.79-times from 2003–2012Citation26 (the Chinese government agreed to implement the new rural cooperative medical system (NCMS) in 2003, a medical insurance system servicing rural residents). Meanwhile, despite the continually increasing financing for NCMS, its spending level is growing faster, and the expenditure ratio increased from 84.33% in 2003 to 96.91% in 2012Citation27. The smooth operation of insurance funds faced pressures. Furthermore, the critical illness insurance program was integrated into NCMS in 2012Citation28, which brought challenges to fund utilization and management. These issues require the implementation of an effective cost control project. Additionally, the NCMS and public hospitals were managed by the local governments. They exert strong control on the formulation of the expenditure cap, the planning of the allocation mechanism, and the supervision of fund usage, as per the framework for a GBCitation29. Therefore, carrying out the GB in Chinese rural areas had already possessed sufficient provisions and feasibilities.

In China, after years of investigation, studies on GB remain relatively scarce, and they are concentrated on urban areasCitation30–32. Existing research on rural areas merely evaluate the effect of controlling costsCitation33,Citation34. However, other questions need to be answered. Does this cost containment approach work, and how does it function? How do medical institutions react to the new compensation method? What is the impact of the cost containment approach on the benefits of rural patients? Meanwhile, in December 2015, the Health and Family Planning Commission of Hubei Province advocated to further strengthen the management of the GB and to be allowed to assume the NCMS roles in regulation and guidance of medical behavior and expenses. Thus, it is urgently required to analyze the effects of the GB in areas where such an approach has been implemented.

Methods

Study setting and intervention assignment

Hubei Province, located in Central China, has a population of 58.52 million. Rural areas account for 43.15%. Its per capita GDP is ¥50,654 (the symbol ¥ represents Chinese Yuan), which ranked 13th among 32 provinces and municipalities in 2015. The rural residents’ participation rate in NCMS reached 98.7% in 2012, and some of its areas started exploring GB in the same year. Despite the extant differences during the implementation among different areas, the main distribution and supervisory principles remained similar.

In terms of expenditure cap determination, the total pool consists of government financial subsidies and the contribution of NCMS participants. In 2012, the financing standard was ¥290; the government subsidized ¥240, and the participant paid ¥50. Of the total pool, 75% was the in-patients fund, 20% represented the outpatient fund, and 5% was the reservation fund. The level and property of the hospital, as well as the medical expenses of the previous year (or the last 3 years) determined the allocated quota for every institution. In terms of allocation, breaking down the quota to the month and prepaying 90%, the remaining 10% is paid in the light of assessment. Savings can be rolled over to the next month’s budget, whereas costs beyond the budget should be assumed by the institution itself. Regarding supervision, the diagnosis compliance rate, cure rate, patient satisfaction, and definitive diagnosis rate within 3 days should be assessed to ensure the quality of medical services. The proportion of drug costs must be evaluated to control drug abuse. Interestingly, the number of hospitalizations should be examined to avoid problems of shifting the responsibility. For example, if the number of hospitalizations decreased by 10% compared with the previous year, the institution would face, as a fine, ∼ 1% of its allocation.

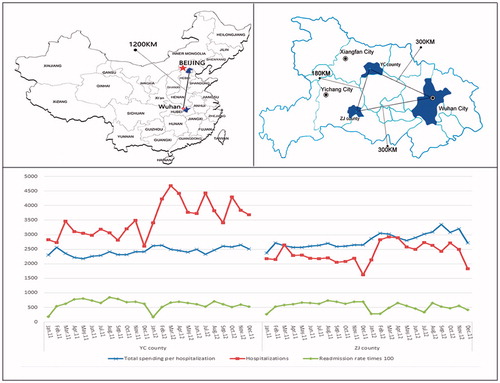

According to the statistical results of city and county level health and family planning work, there were only two counties which actually implemented GB reform in 2013Citation35. YC county (shortened name) acted as the pilot county for GB reform. In addition, YC is at a moderate level of all the counties in Hubei province in terms of economy and health resources, it has a high representativeness. Therefore, we chose YC county as the intervention group. Wuhan city is the capital of Hubei province and the assembling place of health resources which will affect the choice of seeking medical services for residents in surrounding counties. Therefore, we randomly selected five counties which had Wuhan at their center, with a more than 200km radius. We preliminarily compared the changing trend of main indicators of the five counties within 24 months to YC county. Finally, we chose ZJ county (shortened name) as a control group, which was the closest to YC county (). ZJ county acted as a control group for another three reasons: (1) their medical resources were similar to YC county, and no payment reforms were introduced in ZJ from 2012–2014 (); (2) ZJ reimbursement followed a per diem payment. Although the payment rate was determined prospectively, payment was made retrospectively based on outputs. After years of healthcare reform, identifying the total fee for service payment in rural areas is difficult; and (3) the counties belong to different cities, and counties near ZJ have not implemented the GB, allowing for the elimination of the spillover effects.

Table 1. Basic information of YC county and ZJ county (2014).

The growth rate of total expenses for hospitalization was ∼140% from 2009–2011. There was no balance in medical insurance fund. To cope with this problem and respond to the call of government medical insurance reform, YC county implemented the GB of its in-patient fund in January 2013. In-patient services are offered by township hospitals and county level hospitals. (The number of private hospitals is small, and the scale of their operations is larger than the township hospitals. Therefore, we classified them as county level hospitals, for both intervention and control groups.)

The equation for calculating the costs of control target of each medical institution was:

Data collected in September 2015 from the Bureau of NCMS covered every single in-patient from 2012–2014. Inpatient information included three categories: (1) demographic data, which included name, age, gender, living status; (2) cost data, which involved TS, RE, OOP payment, and spending on different clinical types; and (3) treatment data, which entailed name and code of disease, the date of admission and discharge, name and rank of hospitals, and whether or not surgery was involved.

Study design

We intended to reflect the transition of the behaviors of medical services provision through the changes of costs. We assigned the 2012 unit as the pre-intervention period and 2014 as the post-intervention period, because of the hysteresis effects. We considered the counterfactuals during estimation to validate our findings and reach a definitive conclusionCitation36, thus a difference-in-difference method was used to analyze the results. Additionally, the study was divided into three parts.

First, we verified the effects of the GB program on costs control in rural areas. In order to make the research more specific, the impacts on insurance fund and patient’ benefit were examined. We itemized the TS into RE and OOP. Then, we attempted to determine which part could explain the savings. Meanwhile, we demonstrated the hypothesis that medical institutions would transfer to their patients the revenue loss caused by constraint of medical insurance compensation.

Second, we compared the changing trend between the number of hospitalizations and the number of inpatients to determine the effects of GB on the volume of hospitalization. We also worked out the readmission data within 30 days and compared its changing trend. We combined the results above to check whether the supervisory methods truly eliminated the phenomenon of responsibility shifting. Readmission data were divided into two parts, according to whether the second hospitalized agency was similar to the first or not.

Third, to analyze the impacts of a GB on different types of services provided by institutions, hospitalization services were divided into seven categories according to their characteristics. The categories include drug prescription, examination, surgery, treatment, diagnosis, nursing, and unclassified items (blood, protein products, or other consumables), and the volume of each category was represented by expenses.

Variables

Outcomes included the changes of the cost and quantity of medical service provision brought about by the payment reform. Thus, the dependent variables included TS, RE, OOP, and seven kinds of service fees. An additional dependent variable was a dichotomous variable showing whether the patient was rehospitalized or not.

The demographic characteristics, which included age and gender, were controlled. Evidence showed that the physicians’ perceptions are affected by the patient’s socio-economic statusCitation37. Therefore, we controlled for living status by dividing the study population into poor and non-poor, by referring to the latest Chinese rural poverty standards, which equals ¥2,300 of the rural resident’s net income. This part of the population could participate in NCMS freely. Costs were used to reflect the severity of diseaseCitation38–40. Treatment costs were the direct manifestation of difficulty of curing, and our sorting result conformed to the proportion of high cost and high need populationCitation41,Citation42. Thus, we divided the patients into two grades according to their treatment costs (1, 0), where 1 referred to a patient whose treatment costs were higher than ¥1000, which meant that their disease was more severe. 0 represented the patients with less severe disease and treatment costs below ¥1000. A significant correlation exists between surgery and medical expensesCitation43, so we further selected a dichotomous variable showing if the patient had surgery. Given the existing differences in charging standard and reimbursement ratio between two levels of medical institutions, the hospital level was also brought into controlled variables.

For difference-in-difference estimation, independent variables also contained intervention status, wherein the intervention group was 1 and the control group was 0; years, where the pre-intervention period was 0 and the post-intervention period was 1; and the interaction between intervention and years. The interaction between the intervention and post-intervention periods revealed the results of effects estimation. Standard errors were clustered at the practice levelCitation44.

Statistical analyses

We considered each service practice and inpatient information as analysis units to facilitate the use of a difference-in-difference model using multivariate linear regressions, which controlled for individual traits as well as hospital level and time effects. The price index of rural healthcare was used to calibrate all spending figures in 2014 CNY termsCitation45.

We performed two sensitivity analyses to check the robustness of the results. The samples of Test A referred to the continuous hospitalized patients in 2 years. The samples of Test B referred to patients suffering from hypertension, which was the most common disease of two counties. STATA software (version 13) was used for all statistical analyses. Results are reported with two-tailed p-values.

Study results

For the intervention group, 46,830 inpatient practices were included in the 2012 unit and 60,959 in the 2014 unit, which can be attributed to 33,175 and 36,883 patients, respectively. The situation of the control group was 30,303 practices in 2012 and 38,268 in 2014, which covered 23,668 and 29,555 patients, respectively. Detailed characteristics are shown in .

Table 2. Characteristics of the study population.

Effects on expenditures

The results of taking each practice as a research unit indicated that, after the implementation of the GB reform, an average TS faced a ¥263.35 (p < .001) decrease relative to the control group. This figure amounted to a 19.51% saving. After comparing the results of RE and OOP, reductions of RE accounted for all the savings, whereas OOP increased by ¥188.06 (p < .001), which equated to 45.96%.

However, the estimation of taking every inpatient as a unit showed slender and insignificant reductions of ¥64.39 (p = .301). This finding could also be explained by the RE, which decreased by ¥467.45 (p < .001). OOP increased distinctively by ¥408.19 (p < .001), which amounted to 27.89% (). The estimation results of county-level hospitals showed similar and more obvious changes than integral-level, TS and RE decreased by ¥731.61 (p < .001) and ¥971.62 (p < 0.001), OOP increased by ¥246.51 (p < 0.001). However, there were unique effects on township hospitals. Their inpatient’ TS, RE, and OOP all presented escalating trends, which were ¥707.72 (p < .001), ¥214.75 (p < .001), and ¥496.51 (p < .001), respectively.

We also found that GB led to changes of delivery of different medical services categories (). Savings were concentrated in drug prescription at ¥69.03 (p < .001), surgery at ¥40.18 (p < .001), cure at ¥4.95 (p = .565), diagnosis at ¥3.61 (p = .064), and an unclassified item, which was the largest reductions in expenditure at ¥197.68 (p < .001). Meanwhile, the costs of nursing increased by ¥32.55 (p < .001) and costs of examination faced an insignificant rise of ¥10.72 (p = .105). On county-level, the changes were similar to integral-level except for examination, which decreased by ¥58.49 (p < .001). On village-level, except for nursing, diagnosis, and unclassified items which indicated insignificant reductions, expenditure of other items increased significantly. That is to say, savings of integral-level were generated through changes of county level hospitals.

Effects on volume

Hospitalization times of an inpatient from the control group changed from 1.28 to 1.29, with almost no fluctuations. This proportion of the intervention group increased from 1.41 to 1.65. Meanwhile, compared to the control group, the changes of hospitalization time on village-level and county-level institutions of intervention group were 1.12 and 0.98, respectively. The estimation result of referral rate showed no difference (p = .74). However, we found a significant increase of readmission rate within the same hospital, which was 11.4% (p < .001) relative to the control group (). On village-level, this rate was 6.7% (p < .001), on county-level, this rate was 13.8% (p < .001). These results indicated that, in order to flee from the blame of shifting the responsibility and meeting supervisory standards, hospitals separated the entire treating episode. This finding also explained why the remarkable decrease of per case cost was accompanied with an insignificant decrease of per capital cost.

Table 3. Results of difference-in-difference analysis on expenditures and readmission rate (Chinese Yuan, CNY).

Table 4. Results of difference-in-difference analysis on medical service categories (Chinese Yuan, CNY).

Robust checks

and present the results of robust checks (Test A and Test B). Although the analyses showed that TS per capita in Tests A and B increased slightly, these results differ from the main results; they do not have statistical significance. Furthermore, the results of RE and OOP supported our findings. The readmission rate of Test A was consistent with the main result. Moreover, hypertension belongs to chronic diseases; patients’ general knowledge and awareness is adequateCitation46; and the therapeutic effect can be observed easily, such as the drop blood pressure. Therefore, the readmission rate was low, and the GB had no effect on it. Regarding the service categories, results of nursing, examination, cure, and an unclassified item of two checks were similar to the main results. Patients in Test A were continuously hospitalized patients, which meant they had poor health status, thus leading to an increase in fees of drug prescription (p = .937), surgery, and diagnosis. Except for the fees on surgery (p < .978), the remaining estimation of Test B supported our main results.

Discussion

In the analysis of taking each practice as a unit, our findings were consistent with previous studies. The implementation of the GB was associated with a significant reduction in TS growth, which reflected the effect of GB on expenditure control. However, further analysis revealed that the savings of the RE solely contributed to the costs slowdown, whereas the patients’ OOP presented a rising trend. According to the latest figures of the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of the People’s Republic of China, the proportion of medical insurance compensation which accounted for medical institutions revenue has risen from 37% in 2009 to 55% in 2015Citation47. More than half of the hospital income came from reimbursement. This explains the reason why the GB was able to change the behavior of suppliers and curb the rising expenditures. Meanwhile, with the gradual increase of this proportion, the effects of medical insurance payment reform on medical services will be increasingly remarkable.

We must be aware that the direct subsidies of the Chinese government to hospitals only accounted for ∼10% of their income nowadays, thus leading to the survival and development of the majority of public hospitals as interest-oriented. Suppliers are inclined to prescribe more drugs and tests than normal clinical needs, because their bonuses are usually associated with these revenuesCitation48–52. Only in this way can hospitals generate profits to cover the doctor’s salary and support the hospital expansionCitation53. Actually, the prospective payment of insurance restricts the right of the supplier to use medical insurance funds at will. However, as the scope of compensation does not cover all the expenses of the patientCitation54, this part of OOP accounts for ∼35% of the supplier’s income. Thus, they will shift their focus on OOP, which is out of the jurisdiction of the prepaid system. To make up for the loss caused by control of the insurance fund, they may select items outside of the reimbursement list, leading to an increase of the patients’ cost. This fully explains why the reduction of total costs in growth accompanied the increase of patients’ OOP.

Results from taking every in-patient as a research unit were more persuasive. After merging information regarding multiple hospitalizations within the same institution, we determined that the growth of TS per capita lowered slightly. The reduction trend of reimbursement fee was similar when taking each practice as a research unit, but the increase of OOP was much more pronounced, which proved our hypothesis on payment transfer and meant that GB exacerbated the patient’s economic burden of diseases in rural areas. Furthermore, we found out that all the savings were contributed by cost control on county level hospitals. Given that the number and costs of inpatient were higher in county level hospitals, after setting the expenditure cap, they did not have any incentive to add beds or induce demand continually. Under this circumstance, township hospital with beds utilization rate as low as 35% would try to acquire more hospitalized patients in order to earn a higher amount of insurance compensation next year. This phenomenon would promote primary institutions to improve their service capacity to treat more patients. Meanwhile, we should be alert to the behaviors of inducing outpatients to hospitalization or over-treatment in township hospitals.

NCMS has now achieved universal coverage. Residents’ demand for medical services is enhanced with the promotion of compensation degree, rapid aging, environmental deterioration, and other socioeconomic transformationsCitation53. Therefore, we presume that the number of inpatients will increase. Local policy-makers drafted relevant rules to circumvent the responsibility—shifting risk, such as the regulation of the number of hospitalizations. However, the results showed that the number of hospitalizations in the intervention group increased heavily under the circumstance of the number of inpatients’ growth being lower than the control group. Moreover, the readmission rate increased within the same hospital, which indicated the existence of the problem of decomposing hospitalization. It is a disguised trick of shifting the responsibility used by suppliers to cope with the supervision. Cost-quality balance is the priority of any healthcare reform. To ensure that the GB program develops successfully long-term, a more effective and efficient monitoring system is needed. For example, the readmission rate within 30 days should be accessed, adopting a mixed payment method such as pay-for-performance or diagnosis-related groups within the GB program to guarantee that patients receive qualified and reasonable services.

Given that the suppliers’ bonus is usually tied with the benefits created by their own medical behaviors, under postpaid circumstances, a great space exists for supplier-induced demand. Drug revenues accounted for 41.4% of total hospital revenuesCitation26, which is one of the main causes of expensive medical treatment in China. Results from the categories of services showed that the GB significantly lowered the growth of fees related to drugs, surgeries, and unclassified items (mainly consumable cost). This finding suggests that the quota of insurance compensation regulated the suppliers’ behaviors, reduced the use of non-essential or expensive medical treatment items, drugs, and medical consumables. However, whether or not this part of the reduction will harm the patient’s interest could not be ascertained. This is one of the limitations of our research.

Besides insurance policy, many confounders affected medical service provision, such as the patients’ irrational medical appeal, the time effect, and the socioeconomic factors. Although the use of difference-in-difference analysis can maximally eliminate the impact of these confounders, some may still exist. However, they cannot significantly affect the measurement error of results and the conclusions.

In the analysis of service categories, the use of costs to reflect the changes in suppliers’ behavior may be unable to fully reflect the changes in the number of services. Moreover, except for the readmission rate, we had limited information about medical care quality, which restricted the research. We could only detect the phenomenon of prevaricating patients, and were unable to verify the problem of under-treatment. Further studies are needed to supplement and complete these findings.

Conclusion

The GB has a prominent impact on low efficiency and severely wasted insurance operational mode. It constrains the randomness of the doctor’s treatment behavior, and curbs the rapid growth of medical expenditure, especially drug costs and other medical consumables. However, a prospective payment of medical insurance fund triggers a series of negative repercussions. Suppliers shifted the losses caused by the inner expectation gap, which was due to the restraint of free insurance fund usage to the demand side, thus increasing the financial burden of medical care for rural residents. Meanwhile, the underhanded attempt to shift responsibility arising from the response to regulation would harm the interests of patients. Rural conditions differ from the circumstances in cities, especially in some under-developed areas where the affordability and access to medical services are relatively poor. Therefore, changes to the quantity, quality, cost, and other outcomes of medical services that may result from the reform should be weighed comprehensively when carrying out a new medical insurance payment system.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, 71673099) sponsored this study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

RH, YM, TY, YZ, ZL, and LZ are employed by Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. WT is employed by China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, China. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff of Health and Planning Commission of YC county and ZJ county for their support on the research. We also want to thank the associate editor and reviewers for their careful review and insightful comments, which have led to significant improvements of the manuscript.

References

- Van de Ven WPMM. Regulated competition in health care: With or without a global budget? Eur Econc Rev 1995;39:786-94

- Abel-Smith B. Cost containment and new priorities in the European community. Milbank Q 1992;70:393-416

- Wolfe PR, Moran DW. Global budgeting in the OECD countries. Health Care Financing Rev 1993;14:55

- Zhai T, Goss J, Li J, et al. Main drivers of recent health expenditure growth in China: a decomposition analysis. Lancet 2015;386:S46

- Sun X, Jackson S, Carmichael G, et al. Catastrophic medical payment and financial protection in rural China: evidence from the New Cooperative Medical Scheme in Shandong Province. Health Econ 2009;18:103-19

- Joglekar, R. Can insurance reduce catastrophic out-of-pocket health expenditure? Mumbai, India: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research; 2008

- Zhang L, Liu N. Health reform and out-of-pocket payments: lessons from China. Health Policy Plan 2014;29:217

- Opinions regarding the implementation of total expenditure control of the basic medical insurance. Beijing, China: Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security; 2012

- Long SH, Marquis MS. Toward a global budget for the U.S. health system: Implementation issues and information needs. Rand issue paper 1994:1-11

- Li GL, Zhu LL, Gong FL, et al. Analysis of medical expenditure in different medical institutions under total prepayment in Yinchuan. Chin Health Econ 2013;32:33-5

- Guo WB, Zhang L, Li YF, et al. Analysis of the effect of medical insurance scale payment. Chin Health Econ 2012;31:25-7

- Sun SX, Sun JJ, Wei JL, et al. Effect evaluation of global budget of medical insurance in Beijing. Chin Health Econ 2012;31:23-5

- Sheynin OB. Studies in the history of probability and statistics. XXI. On the early history of the law of large numbers. Biometrika 1968;55:459-67

- Song Z, Safran DG, Landon BE, et al. The ‘Alternative Quality Contract’, based on a global budget, lowered medical spending and improved quality. Health Affairs 2012;31:1885-94

- Yakoboski PJ, Ratner J, Gross DJ. The effectiveness of budget targets and caps in the German ambulatory care sector. Benefits Q 1994;10:31

- Redmon DP, Yakoboski PJ. The nominal and real effects of hospital global budgets in France. Inquiry 1995;32:174-83

- Aas IH. Incentives and financing methods. Health Policy 1995;34:205-20

- Chang RE, Hsieh CJ, Myrtle RC. The effect of outpatient dialysis global budget cap on healthcare utilization by end-stage renal disease patients. Social Sci Med 2011;73:153-9

- Giorgio LD, Filippini M, Masiero G. Implications of global budget payment system on nursing home costs. Health Policy 2014;115:237-48

- Chang L, Hung JH. The effects of the global budget system on cost containment and the quality of care: experience in Taiwan. Health Serv Manag Res 2008;21:106-16

- Afendulis CC, Fendrick AM, Song Z, et al. The Impact of Global Budgets on Pharmaceutical Spending and Utilization: Early Experience from the Alternative Quality Contract. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing 2014:51:1-7

- Kan K, Li SF, Tsai WD. The impact of global budgeting on treatment intensity and outcomes. Int J Health Econ Manag 2014;14:311-37

- Zhang JH, Chou SY, Deily ME, et al. Hospital ownership and drug utilization under a global budget: a quantile regression analysis. Int Health 2014;6:62

- Goins RT, Williams KA, Carter MW, et al. Perceived barriers to health care access among rural older adults: a qualitative study. J Rural Health 2005;21:206-13

- Auchincloss AH, Hadden W. The health effects of rural-urban residence and concentrated poverty. J Rural Health 2002;18:319-36

- China Health Statistical Yearbook. Beijing, China: National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2014

- Statistic bulletin of Chinese Health and Family Planning Development in 2012. Beijing, China: National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2013

- Opinions on implementing critical illness insurance program. Beijing, China: National Development and Reform Commission, National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China, Ministry of Finance of the People's Republic of China, et al; 2012

- Altman SH, Cohen AB. The need for a national global budget. Health Affairs 1993;12(Suppl1):194-203

- Leng JH, Gao GY, Chen ZS, et al. The impact of global budget on operational effect of basic medical insurance: A case study of Beijing Cancer Hospital. Chin J Health Policy 2014;7:35-9

- Gao YX, Xiao J, Zhong YQ, et al. Evaluation of payment reform on different hospital expenditures reimbursement under global budget in Nantong. Chin Health Econ 2014;33:48-50

- Yi H, Yan L, Yang X, et al. Global budget payment system helps to reduce outpatient medical expenditure of hypertension in China. Springerplus 2016;5:1877

- Xue QX, Su M, Zhou ZL. The effects of global budget of new rural cooperative medical system on inpatient expenditure. Chin Health Econ 2015;34:41-3

- Sheng HQ, Wang LY, Chen YQ, et al. Reform and exploration about total quota payment of the new rural cooperative medical system in Weifang. Chin Health Econ 2016;35:45-7

- Hubei Health and Family Planning Yearbook. Wuhan, China: Health and Family Planning Commission of Hubei Province; 2014

- Chen B, Fan VY. Strategic provider behavior under global budget payment with price adjustment in Taiwan. Health Econ 2015;24:1422-36

- Van RM, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Social Sci Med 2000;50:813-28

- Hux MJ, O’Brien BJ, Iskedjian M, et al. Relation between severity of Alzheimer’s disease and costs of caring. Can Med Assoc J 1998;159:457-65

- Serrabatlles J, Plaza V, Morejon E, et al. Costs of asthma according to the degree of severity. Eur Respir J 1999;12:1322-6

- Lee PP, Walt JG, Doyle JJ, et al. A multicenter, retrospective pilot study of resource use and costs associated with severity of disease in glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2006;124:12-19

- Stanton MWRMK. The high concentration of US health care expenditures. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006

- Feder JL. Predictive modeling and team care for high-need patients at HealthCare Partners. Health Affairs 2011;30:416-8

- Murphy GJ, Reeves BC, Rogers CA, et al. Increased mortality, postoperative morbidity, and cost after red blood cell transfusion in patients having cardiac surgery. Circulation 2007;116:2544-52

- Halbert White. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica J Econometric Soc 1980;48:817-38

- China Statistical Yearbook. Beijing, China: National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China; 2015

- Oliveria SA, Chen RS, McCarthy BD, et al. Hypertension knowledge, awareness, and attitudes in a hypertensive population. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:219-25

- Li SC. How health insurance control public hospitals? Shanghai, China: Yixuejie. http://chuansong.me/n/804833145045. Accessed September 2016

- Reynolds L, Mckee M. Serve the people or close the sale? Profit-driven overuse of injections and infusions in China’s market-based healthcare system. Int J Health Plan Manag 2011;26:449-70

- Yip WC, Hsiao W, Meng Q, et al. Realignment of incentives for health-care providers in China. Lancet 2010;375:1120

- Blumenthal D, Hsiao W. Privatization and its discontents—the evolving Chinese health care system. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1165-70

- Li Y, Jing X, Fang W, et al. Overprescribing in China, driven by financial incentives, results in very high use of antibiotics, injections, and corticosteroids. Health Affairs 2012;31:1075-82

- Liu X, Mills A. Evaluating payment mechanisms: how can we measure unnecessary care? Health Policy Plan 1999;14:409-13

- Yip W, Hsiao W. Harnessing the privatisation of China’s fragmented health-care delivery. Lancet 2014;384:805

- Long Q, Xu L, Bekedam H, et al. Changes in health expenditures in China in 2000s: has the health system reform improved affordability. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:40