Abstract

Aims: Although several therapeutic options are available for chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura (cITP), little is known about the treatment of cITP in Brazil.

Materials and methods: A multi-center, retrospective chart review, observational study was designed to describe the treatment patterns, clinical burden, resources use, and associated costs for adult patients diagnosed with cITP and treated in public and private institutions in Brazil. Patient charts were screened in reverse chronological order based on their last visit post January 1, 2012. (All costs were calculated using 1.00 USD = 3.9571 BRL, from February 2016.)

Results: Of 340 patient charts screened, 50 patients were eligible for inclusion in the study. Single-drug therapy (prednisone, dexamethasone, or dapsone) was the most commonly used treatment, followed by combination therapies (azathioprine + prednisone, azathioprine + prednisone + danazol, and prednisone + dapsone). Splenectomy was performed in 22% of patients after at least first-line treatment. Platelet count and number of bleeding episodes at diagnosis were 31,561.1/mm3 (SD = ±26,396.1) and 40 episodes, respectively; in first-line, 92,631.1/mm3 (SD = ±79,955.3) and 19 episodes, respectively; in second-line, 96,950.0/mm3 (SD = ±76,476.4) and 17 episodes, respectively. Private system patients had a higher median cost compared to public system patients (USD 17.49/month, range = 0–2,020.77 vs USD 9.51/month, range = 0–192.64, respectively).

Limitations: This study does not allow conclusions for causal explanations due to the cohort study design, and treatment patterns represent only the practices of physicians who have agreed to participate in the study.

Conclusions: The data indicate that available therapeutic strategies for second- and third-line therapies appear to be limited.

Introduction

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP, also known as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura) is a rare autoimmune disease characterized by episodes of thrombocytopenia and hemorrhagic manifestationsCitation1–4. This disorder can lead to excessive bruising and bleeding, resulting from unusually low levels of platelets. Although major bleeding episodes are rare in ITP, they represent a great risk and can be fatal, especially in elderly patients, who have increased bleeding episodes and severityCitation5,Citation6.

According to the International Working Group (IWG) consensus, diagnosis of ITP is made by the presence of isolated thrombocytopenia (<100,000 platelets/mm3) with the absence of constitutional symptomsCitation2. Furthermore, IWG defined severity and response criteria, and remarks that the severity correlates with the degree of thrombocytopenia. “Acute ITP” classification was replaced by “ITP newly diagnosed cases”, in which the patient did not exceed a period of 3 months from diagnosis. Patients with the disease for >12 months are defined as “chronic ITP” (cITP). In addition, the consensus included a new classification for patients diagnosed in a period from 3–12 months (“persistent ITP”)Citation7.

Several diagnostic and management guidelines are available for cITP. The main goals of cITP treatment are to ensure a safe platelet count (above 20,000–30,000/mm3) and prevent bleeding complicationsCitation7,Citation8. To achieve these goals, currently available therapeutic options include corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), anti-D immunoglobulin, splenectomy, and thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor agonists.

According to ASH 2010 consensus and Brazilian guidelines, second- and third-line therapies for cITP remain undefinedCitation9–11. However, according to the more recently published evidence-based practice ASH guideline (2011), second-line therapy options are limited to TPO receptor agonists, splenectomy, and rituximabCitation12. In Brazil, patients with cITP have not yet been systematically monitored and evaluated. Consequently, Brazilian data on current clinical practices and outcomes of ITP are scarce or even absent. We conducted a retrospective chart review study designed to describe treatment patterns, clinical burden, resource use, and associated costs in adult cITP patients treated in five referral institutions in Brazil.

Methods

Study design

This multi-center, retrospective chart review, observational cohort study was conducted in five Brazilian institutions (three public and two private institutions). The primary objective of the study was to describe the patterns of care and the use of resources of chronic ITP in the selected institutions. Patient’s charts were screened in reverse chronological order, based on their last visit post January 1, 2012. This sampling approach will allow for a focus on resource use that is related to the introduction of new TPO agonists in Brazil. For treatment patterns, the entire ITP disease period from diagnosis was considered. For resource use and cost analysis, a 1 year period for cITP care was defined. Prospective follow-up of patients was not performed.

This study was conducted according to good clinical practice, Declaration of Helsinki and Brazilian regulation, with the study protocol approved by each of the five Institutional Ethics Committees (IECs). Informed consent was obtained from patients as required by each IEC’s opinion. All collected data was fully anonymized in order to ensure patient confidentiality and privacy.

Study population

The study population consisted of adult patients aged >18 years with a documented diagnosis of ITP. To align with the introduction of TPO receptor agonists in Brazil, patients were included in the study if their last visit was from January 2012 to data extraction date. For inclusion in the study, patients had to have had at least one ITP-related visit in the study institution during the study period and to have been followed for at least 1 year after diagnosis.

Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of hematologic malignancy and/or immune disease in addition to ITP (e.g. lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus, or other autoimmune disease that can cause secondary ITP or anti-phospholipid syndrome, among others) or viral infections of hepatitis C and/or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); with diagnosis of ITP during pregnancy; unreliable data according to the physician; or with previous or current participation in other clinical trials.

Costs

Estimation of costs used the bottom-up method based on individual chart data. Because of the chronic nature of ITP, the use of resources was evaluated and, subsequently, so was the disease cost resulting during a defined period of the last 1 year after cITP diagnosis. Only treatment burden was evaluated in this study. Additionally, indirect costs were not considered for this analysis.

Due to differences in healthcare perspectives in Brazil, public and private costs were evaluated separately. Costs of procedures from the private system were calculated according to the values published in the Brazilian Hierarchical Classification of Medical Procedures, 5th EditionCitation13. Costs of procedures from the public system were calculated according to values defined on the Management System of Procedures, Drugs and Orthotics, Prosthetics and Special Materials (OPM), Table of the National Public Healthcare System (SUS), SIGTAPCitation14. Medication costs for the private system were extracted from CMEDCitation15; for the public system, medication costs were extracted from the price database of the Ministry of HealthCitation16. All the costs were converted to 2016 US dollars (US$1.00 ∼ 3.9571 BRL in February 2016, Brazilian Central Bank exchange ratio).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were limited to descriptive characteristics with no formal hypothesis testing. The planned sample size for the study was 60 patients; however, the final data set included information from 50 patients, due to the lack of eligible ITP patients treated in the included institutions. Considering a proportion of 20% of patients performing splenectomy during ITP second-line treatment, an ∼11% error margin half-width of 95% CI was obtained for a sample size of 50 patients. In this study, we considered treatment line numbers according to treatment order, e.g. 1st treatment line refers to first treatment used.

All assessments were conducted using the full analysis set (FAS) population. Descriptive statistics included mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum, maximum, median, and range for continuous variables and cross tabulation contingency, with absolute frequencies and percentages with 95% CIs for categorical variables.

Use of therapies for ITP, including duration of exposure and number of different therapies per individual, was calculated throughout the follow-up period. Frequency of drug therapies use for ITP treatment was summarized by therapy. Most frequently reported treatments in each line were also summarized. Data were analyzed descriptively using observations available. Missing data imputation was not conducted in this study.

Results

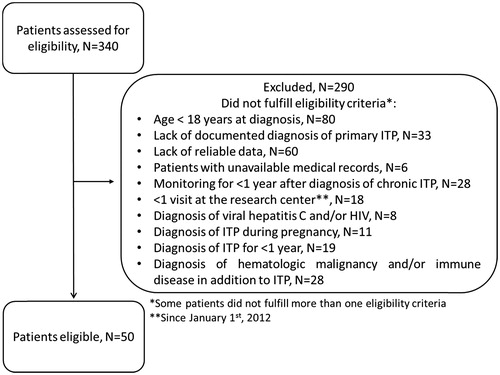

From December 2014 to August 2015, a total of 340 patient charts were screened for inclusion in the study; and 50 patients meet all inclusion criteria and were included (). Forty-two percent of patients (n = 21) came from private institutions. Most common for study exclusion were age <18 at diagnosis (n = 80); lack of reliable data (n = 60); and lack of documented diagnosis of primary ITP (n = 33).

Most patients were women (35; 70%) and white (25; 50%). Overall mean age of patients at diagnosis was 44 ± 16.3 years. Mean time from diagnosis to study inclusion was 5.5 ± 3.4 years. Clinical and demographic data of the patients are shown in .

Table 1. Demographic and clinical data of study patients.

Among the total sample, 27 patients (54%) had at least one bleeding episode at diagnosis; of those, eight patients (38%) were public and 19 patients (65.5%) were private. Overall, types of bleeding at diagnosis were spontaneous bleeding, bleeding related to trauma, mucocutaneous bleeding, urinary bleeding, vaginal bleeding, metrorrhagia, and spleen bleeding.

Bleeding into the skin was the most frequent type of bleeding (36%), followed by mucosal (16%), gastrointestinal (4%), and trauma (4%). At diagnosis, 46% of the patients presented a platelets count less than 20,000/mL; 32% presented counts from 20,001/mL to 50,000/mL; and 22% presented counts from 50,001/mL to 100,000/mL. Additionally, five patients (10%) presented constitutional symptoms at diagnosis, such as weight loss.

Treatment patterns

Of the 50 patients analyzed, 45 (90%) received pharmacological therapy as first-line treatment, and five patients (10%) did not receive treatment and were followed according to a “watch and wait” strategy. Sixty-six percent of patients received second-, 46% third-, and 30% fourth-line therapies. Median duration of first-line treatment was 2.4 (minimum = 0.1, maximum = 26.1) months, and 1.7 (minimum = 0.1, maximum = 18) and 3.6 (minimum = 0.1, maximum = 46.1) months for second and third-lines, respectively (). Additionally, median number of treatment lines, regardless of health perspective, were 3.0 (minimum = 1, maximum = 15). Likewise, the median number of treatment lines according to private or public health perspective were 2.5 (minimum = 1, maximum = 9); and 3.0 (minimum = 1, maximum = 15) ± 3.1 lines, respectively.

Table 2. Treatment drugs/regimens from first to fifth treatment line.

Single drug therapy was the most commonly used treatment until fourth-line. Corticosteroid treatment with prednisone and dexamethasone was the most common therapy in the first-line setting. Drugs most frequently used in second-line therapy were prednisone, dapsone, and dexamethasone. For third-line therapy, prednisone, dapsone, and combination therapies were the most used. Regardless of the therapy, prednisone was the most frequently used drug, followed by dexamethasone and dapsone (). Rates of prednisone use were 71.1%, 45.4%, 34.8%, and 26.7% in the first-, second-, third-, and fourth-lines of treatment, respectively.

Furthermore, combination therapy was also reported, and the most used combination therapies, regardless of the therapy line, were azathioprine + prednisone; azathioprine + prednisone + danazol; and prednisone + dapsone.

At total, splenectomy was performed in 11 (22%) patients, of which eigh patients (72.7%) presented a complete response (platelet count above 100,000/mm3 after splenectomy). All splenectomies were performed only after first-line and, in 72.7% of the cases, until fifth-line of treatment (). After fifth-line, two patients were submitted to splenectomy in sixth-line and one patient in twelfth-line (data not shown). Only one patient (9.1%) had complications related to splenectomy and was hospitalized. The most commonly administered treatments before surgery were corticosteroid (36.4%) and immunoglobulin (36.4%). No death was reported due to splenectomy.

Rituximab was used as monotherapy in third-line therapy (n = 1) and in association with prednisone in eighth-line therapy (n = 1) (data not shown). The use of TPO drug class was not observed in any patient, regardless of therapy line.

Lack of benefit leading to end of treatment was observed in 33.3% of patients in first line therapy, 21.2% in second line therapy, 34.8% in third line therapy, and 13.3% in fourth line therapy. Tolerability or an adverse event were responsible for the end of treatment in 6.7%, 12.1%, 0%, and 6.7% for first-, second-, third-, and fourth-line treatments. Other reasons for end of treatment included costs and other administrative reasons (three patients) or patient decision to withdraw the treatment (four patients).

Clinical burden and safety

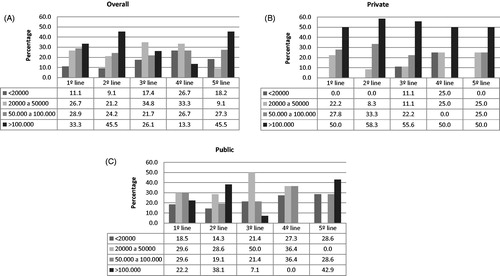

Levels of platelets at the end of treatment are described separately by treatment lines and health perspective in . Additionally, at least 25% of the patients had presented bleeding episodes in each treatment line, regardless of treatment and healthcare perspective (). The most frequent reported adverse events associated with the first line treatment were mood alteration (8.9%), hypertension or hypertensive peak (4.4%), or other adverse events (13.3%). Cushing syndrome, mood alteration, and gastrointestinal disorders were the most often reported events for second-line therapy. Most common adverse events reported in prednisone use were Cushing syndrome (5.2%), mood alteration (5.2%), hypertension or hypertensive peak (3.9%), and gastrointestinal disorders (3.9%). Only one patient was hospitalized during the study period. No deaths were observed in the follow-up.

Figure 2. Proportion of patients achieving platelets levels of less than 20,000, 20,000–50,000, 50,000–100,000, and more than 100,000 over the end of treatment lines, regardless of overall (A), public (B), and private (C) institutions.

Table 3. Platelets levels and bleeding episodes per line treatment.

Resource use

All patients from public institutions had regular follow-ups (at least one visit in the last 12 months), while 85.7% of patients from private institutions were followed regularly. Overall, follow-up was performed in intervals of 1–3 months (46.8%), 3–6 months (23.4%), or 6–12 months (29.8%). Overall mean number of visits to hematologists during the last year of follow-up was 3.9 ± 2.5, and 0.2 ± 0.7 for non-hematologists. shows the number of visits according to health perspective. In this study only one patient was hospitalized, due to complications after splenectomy.

Table 4. Resource use in diagnosis and in the observed period.

Complete blood count was the most frequent laboratorial exam performed during the last follow-up year, with a total mean of 4.3 ± 3.4 per patient, with higher frequency among public perspective (mean = 5.4 ± 4.0) when compared to private perspective (mean = 2.8 ± 1.5). Glucose test, urea, creatinine, and hepatic function panel (Alanine transaminase (ALT), Aspartate transaminase (AST), Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT)) were also performed with a mean range of 0.9–1.2 exams in the study period. Other exams, such as potassium, lactate dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin, were also performed, but less frequently (mean <1 exam in the last year) ().

Table 5. Number of laboratory evaluations performed in 1-year evaluation.

Costs

In the 1-year follow-up time to evaluate chronic ITP, mean costs for laboratory testing were US$13.83 for patients treated in the public healthcare system and US$56.56 for patients treated in the private healthcare system. Additionally, mean costs of medical visits were US$11.88 and US$14.97 in the public and private systems, respectively. For treatment costs (drugs and splenectomy), the study collected patient data throughout the whole course of treatment. In the public perspective, the median treatment cost was US$9.51/month, range = $0–192.64, per patient, while, in the private perspective, the median treatment cost was US$17.49/month, range = $0–2,020.77 per patient.

Considering both public and private institutions, single-agent prednisone was the most commonly adopted treatment in patients with ITP (n = 77, data not shown), followed by dapsone (n = 15) and dexamethasone (n = 13). The most expensive treatments were performed more often in the public institutions and were immunoglobulin G IV (n = 5; median = US$1,250.92; range = $168.21–4,336.51; per treatment); azathioprine + prednisone + danazol + cyclophosphamide (n = 2; median = US$1,133.15; range = $905.49–1360.81; per treatment); and prednisone + rituximab (n = 1; US$1,111.73 per treatment). In the private perspective, the most expensive treatment was rituximab (n = 1; US$6,485.88 per treatment), performed only in one patient. When evaluating patients stratified by splenectomy status, patients submitted to splenectomy (n = 10) presented higher median treatment costs (US$887.53, range = $248.32–4,650.34 per treatment) than patients who were not (n = 31) (US$76.66, range = $1.05–651.46 per treatment) (data not shown). Dapsone treatment costs were very low for both public and private institutions (), once its pricing is extracted from a price table from governmental production in both CMEDCitation15 and Ministry of HealthCitation16 databases.

Table 6. Median treatment cost and length of treatment by healthcare perspective.

Discussion

In recent decades, there have been many changes and advances in the management and available guidelines for the treatment of ITP. Additionally, patterns of care and strategies may vary from healthcare perspectives, available resources, and clinical epidemiology of the patients. This cohort study describes the ITP management from five institutions using data coming from hospital charts. In treatment patterns, single-drug therapy was the most commonly used treatment, followed by combination therapies. Splenectomy was performed in 22% of patients after at least first-line treatment. In terms of resource uses and cost of illness, laboratorial exams and treatment related to ITP (drugs and splenectomy) showed to have a significant impact in the burden of the disease. The majority of the patients in this study had platelets levels inferior to 50,000 mm3 at diagnosis. Although IWG consensus defined the ITP diagnosis as presence of isolated thrombocytopenia (<100,000 platelets/mm3) with the absence of constitutional symptomsCitation2, 10% of the patients presented constitutional symptoms at diagnosis.

In order to describe treatment patterns, this multi-center, retrospective chart review, observational cohort study was conducted in five Brazilian institutions. This study gives unique information regarding treatment patterns and resource use in ITP treatment in Brazil, once real-world data in Latin America and Brazil are scarce. Real world data from this study are very important for decision-making agenciesCitation17, due to its high external validity. Likewise, this result may contribute to the development of new strategies and handling guidelines for ITP management, and it can be very useful in the decision-making process of incorporating interventions, which can minimize the burden of this disease in Brazil.

On the other hand, this study presents some limitations. The results do not allow conclusions for causal explanations due to the cohort study design. Also, one important limitation of retrospective studies is that the data are often incomplete. Individual or entire series of records can be missing, either because dates were misplaced or data were not recorded. Additionally, treatment patterns and resource use represent only the practices of physicians who have agreed to participate in the study, and may vary from non-responding physician, i.e. those who refused study participation or failed to complete the study requirements on time and were excluded from the study. Still, this study has a small sample size, so results may not be over-generalized. Despite these limitations, this study provides novel information regarding ITP current treatment patterns and costs from five referral institutions in Brazil.

According to both Brazilian and ASH guidelines of ITP treatment, first-line therapy options are corticosteroids, IVIg, and Anti-D (recommended only in ASH, but not in Brazilian guideline), of which the last two are reserved for patients with contraindication to corticosteroids. However, prolonged and chronic use of corticosteroids are not recommended due to adverse events, such as weight gain, cataracts, hyperglycemia, osteoporosis, and increased risk of infectionsCitation18,Citation19. Our study reports corticosteroids as the most frequent in first-line treatment, corresponding to 95.6% of first-line treatments (), similarly to data described in the literatureCitation20; dapsone was used in 4.4% of first-line patients, although not included as a first-line option.

Dapsone was the second most reported prescribed single-drug in this study, also it was used in association with prednisone, adhering to the ASH 2010 consensus review on ITP treatmentCitation9, but not the ASH 2011 evidence-based practice guideline—that suggests only corticosteroids, IVIg, Anti-D, thrombopoietin receptor agonists, and splenectomyCitation12. On the other hand, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, and danazol remain as ITP treatment strategy in the Brazilian guideline and ASH 2010 consensus reviewCitation9,Citation11, although not frequently reported in our study.

IVIg can be used as an alternative to corticosteroids and has also been used as a rescue medicine, especially in cases of critical bleeding or when platelet count needs to be quickly increased. IVIg is a quick and effective therapy in ITP, but its effects cease rapidly. Furthermore, IVIg was used by 10% of patients of this study, and anti-D immunoglobulin was not used at all. Anti-D immunoglobulin has comparable efficacy rates to IVIg, but, in 2010, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning highlighting the risk of intravascular hemolysis, acute renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) caused by this drug. As a result, IVIg use has significantly decreased, and is no longer available in some countries, such as the United KingdomCitation21. Nevertheless, ASH guidelines still recommend this agent as an alternative therapyCitation11,Citation12,Citation22. In this study, IVIg therapy was administered in five different patients, and accounted for a considerable amount of ITP-related therapy costs, US$1,671.85 ± 1,702.26 per treatment. In fact, IVIg therapy was one of the most expensive therapies used.

In contrast, rituximab was not administered frequently, regardless of institution perspective and treatment line in this study. Likewise, the use of TPO receptor agonist drugs, romiplostim and eltrombopag, was not observed in this study, although it was recommended for some ITP patientsCitation22–24. A national-based study conducted in France suggested that ITP management have improved after availability of TPO drugs and rituximab. Additionally, the authors demonstrated that those drugs are not commonly prescribed during onset of the disease or earlier lines of treatment, while patients may benefit with the introduction of those treatments at earlier phasesCitation25. Although the introduction of TPO agonists occurred approximately in 2012 in Brazil, up to early 2016, romiplostim and eltrombopag were not incorporated into Brazilian guidelines for the treatment of ITPCitation7. The absence of TPO agonist drugs to the treatment patterns or therapeutic strategy, regardless of healthcare perspective, may be associated to the recommendations presented in the Brazilian guidelines.

According to the Brazilian guidelines, splenectomy is recommended after chronic use of corticosteroids and human immunoglobulinCitation11. In this study, 22% of ITP patients underwent splenectomy. This proportion diverge from other European published studies (12%Citation26, 14%Citation27, 15.4%Citation28, 23%Citation29, 24%Citation20,Citation30, 50%Citation31, 52%Citation32, 60%Citation33, and 63%Citation34). Moreover, surgery was not observed at earlier lines for ITP treatment. Relapse was observed in 27.3% of patients who underwent splenectomy.

Splenectomy remained the standard ITP treatment until immunoglobulins and TPO receptor agonists were introduced into the marketCitation35. Reported rates of splenectomy in patients with chronic ITP vary from 12–63%—of these, ∼ 70% achieve a sustained response after a normal platelet values procedure and only 15% are refractory to splenectomy (0–51%) at a mean time of 33 monthsCitation18,Citation19,Citation25,Citation36,Citation37. Surgical removal of the spleen quickly eliminates the main source of platelet destruction and improves platelet count. However, splenectomy is associated with complications such as infections, bleeding, thrombosis, and prolonged hospitalizationCitation18.

Adult patients with chronic ITP significantly burden the healthcare system due to hospitalizations, treatments, adverse events, transfusions, and use of rescue therapyCitation35. Additionally, splenectomy may be directly associated with the disease burden, due to the different outcomes of morbidity and mortality related to surgical methods.

Considering that ITP is a chronic disease, the study evaluated its costs and resource uses during a 1-year follow-up period, once bottom up approach is based on disease prevalence. Due to the limited follow-up period, the transfusion procedure was not reported for any patient, and only one hospitalization was observed in the aforementioned 1-year period. We observed a higher median treatment cost in the private healthcare system (US$17.49/month per patient, range = $0–2,020.77) compared to the public perspective (US$9.51/month per patient, range = $0–192.64). A broad variation of the costs was observed, mainly due to the heterogeneity of the patients and follow-up period. Additionally, the average treatment cost of patients undergoing splenectomy was higher compared to the other patients, and it was associated as a burden in ITP treatment.

Further real life studies are needed in broader populations to determine more precisely the patterns of treatment in Brazil. In terms of resource utilization, an analysis of the patient profiles related to the higher costs of illness is essential to understand how the burden of chronic ITP can be minimized in the Brazilian healthcare system.

Conclusion

Overall, this data described treatment patterns, resource use, and costs related to ITP in private and public institutions in Brazil. Also, therapeutic strategies of second- and third-line therapies still remain scarce in the real world clinical practice. The data indicate that available therapeutic strategies for second- and third-line therapies appear to be limited.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored and monitored by Amgen Brazil. Amgen did not influence patient selection or scientific conduction of the study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

EM and GSJ are employees of Kantar Health. RFDS is currently employed by Amgen Inc. The remaining authors received research funding from <grant sponsor > Amgen<\grant sponsor>. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support of Rodrigo Santucci Alves da Silva, Christiane Bueno, Luiz Fernando Andrade Feijó, Sandra Loggeto, Estela Federal, Mayara Piani, Carolina Santinho and all site staff involved in the study.

References

- George JN, Woolf SH, Raskob GE. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a practice guideline developed by explicit methods for the American Society of Hematology. Blood 1996;88:3-40

- Neunert C, Lim W, Crowther M, et al. The American Society of Hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2011;117:4190-207

- British Society for Haematology, BSH. Guidelines fo the investigation and management of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in adults, children and in pregnancy. Br J Hematol 2003;120:574-596

- Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood 2009;113:2386-93

- Fogarty PF. Chronic immune thrombocytopenia in adults: epidemiology and clinical presentation. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2009;23:1213-21

- Daou S, Federici L, Zimmer J, et al. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in elderly patients: a study of 47 cases from a single reference center. Eur J Intern Med 2008;19:447-51

- Cooper N, Terrinoni I, Newland A. The efficacy and safety of romiplostim in adult patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia. Ther Adv Hematol 2012;3:291-8

- Despotovic JM, Neunert CE. Is anti-D immunoglobulin still a frontline treatment option for immune thrombocytopenia? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2013;2013:283-5

- Provan D, Stasi R, Newland AC, et al. International consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2010;115:168-86

- George JN. Sequence of treatments for adults with primary immune thrombocytopenia. Am J Hematol 2012;87(Suppl1):S12-S15

- Ministério da Saúde. Púrpura Trombocitopênica Idiopática. Portaria SAS/MS n° 1.316, de 22 de novembro de 2013. In: Ministério da Saúde, editor. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas. Ministério da Saúde. Brasília; 2013

- Neunert C, Lim W, Crowther M, et al. The American Society of Hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2011;117:4190-207

- Associação Médica Brasileira. Classificação Brasileira Hierarquizada de Procedimentos Médicos. Associação Médica Brasileira. São Paulo; 2014

- DATASUS. Sistema de Gerenciamento da Tabela de Procedimentos, Medicamentos e OPM do SUS. Ministério da Saúde. Brasília; 2016

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Preços Máximos de Medicamentos por Princípio Ativo. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Brasília; 2015

- Ministério da Saúde. Banco de Preços em Saúde. Ministério da Saúde. Brasília; 2015

- Stephens JM, Handke B, Doshi JA. International survey of methods used in health technology assessment (HTA): does practice meet the principles proposed for good research? Compar Effect Res 2012;2:29-44

- Kuter DJ, Bussel JB, Lyons RM, et al. Efficacy of romiplostim in patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;371:395-403

- Kuter DJ, Rummel M, Boccia R, et al. Romiplostim or standard of care in patients with immune thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1889-99

- Bauer M, Baumann A, Berger K, et al. A retrospective observational single-centre study on the burden of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). Onkologie 2012;35:342-8

- NICE. Eltrombopag for the treatment of chronic immune (idiopathic) thrombocytopenic purpura. NICE. London; 2010

- Kojouri K, Vesely SK, Terrell DR, et al. Splenectomy for adult patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a systematic review to assess long-term platelet count responses, prediction of response, and surgical complications. Blood 2004;104:2623-34

- NICE. Romiplostim for the treatment of chronic immune (idiopathic) thrombocytopenic purpura. NICE. London; 2011

- Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, et al. Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:959-69

- Moulis G, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc JL, et al. Exposure to non-corticosteroid treatments in adult primary immune thrombocytopenia before the chronic phase in the era of thrombopoietin receptor agonists in France. A nationwide population-based study. Autoimmun Rev 2015;14:168-73

- Neylon AJ, Saunders PW, Howard MR, et al. Clinically significant newly presenting autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura in adults: a prospective study of a population-based cohort of 245 patients. Br J Haematol 2003;122:966-74

- Khellaf M, Le Moine JG, Poitrinal P, et al. Costs of managing severe immune thrombocytopenia in adults: a retrospective analysis. Ann Hematol 2011;90:441-6

- Kaya E, Erkurt MA, Aydogdu I, et al. Retrospective analysis of patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura from Eastern Anatolia. Med Princ Pract 2007;16:100-6

- Pamuk GE, Pamuk ON, Baslar Z, et al. Overview of 321 patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Retrospective analysis of the clinical features and response to therapy. Ann Hematol 2002;81:436-40

- Sailer T, Lechner K, Panzer S, et al. The course of severe autoimmune thrombocytopenia in patients not undergoing splenectomy. Haematologica 2006;91:1041-5

- Cortelazzo S, Finazzi G, Buelli M, et al. High risk of severe bleeding in aged patients with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 1991;77:31-3

- Stasi R, Stipa E, Masi M, et al. Long-term observation of 208 adults with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Med 1995;98:436-42

- Portielje JE, Westendorp RG, Kluin-Nelemans HC, et al. Morbidity and mortality in adults with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 2001;97:2549-54

- Schiavotto C, Rodeghiero F. Twenty years experience with treatment of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in a single department: results in 490 cases. Haematologica 1993;78:22-8

- Deuson R, Danese M, Mathias SD, et al. The burden of immune thrombocytopenia in adults: evaluation of the thrombopoietin receptor agonist romiplostim. J Med Econ 2012;15:956-76

- Cheng G, Saleh MN, Marcher C, et al. Eltrombopag for management of chronic immune thrombocytopenia (RAISE): a 6-month, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet 2011;377:393-402

- Bussel JB, Provan D, Shamsi T, et al. Effect of eltrombopag on platelet counts and bleeding during treatment of chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2009;373:641-8