Abstract

Background: A 3-month long treatment of paliperidone palmitate (PP3M) has been introduced as an option for treating schizophrenia. Its cost-effectiveness in Spain has not been established.

Aims: To compare the costs and effects of PP3M compared with once-monthly paliperidone (PP1M) from the payer perspective in Spain.

Methods: This study used the recently published trial by Savitz et al. as a core model over 1 year. Additional data were derived from the literature. Costs in 2016 Euros were obtained from official lists and utilities from Osborne et al. The authors conducted both cost-utility and cost-effectiveness analyses. For the former, the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained was calculated. For the latter, the outcomes were relapses and hospitalizations avoided. To assure the robustness of the analyses, a series of 1-way and probability sensitivity analyses were conducted.

Results: The expected cost was lower with PP3M (4,780€) compared with PP1M (5,244€). PP3M had the fewest relapses (0.080 vs 0.161), hospitalizations (0.034 v.s 0.065), and emergency room visits (0.045 v.s 0.096) and the most QALYs (0.677 v.s 0.625). In both cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses, PP3M dominated PP1M. Sensitivity analyses confirmed base case findings. For the primary analysis (cost-utility), PP3M dominated PP1M in 46.9% of 10,000 simulations and was cost-effective at a threshold of 30,000€/QALY gained.

Conclusions: PP3M dominated PP1M in all analyses and was, therefore, cost-effective for treating chronic relapsing schizophrenia in Spain. For patients who require long-acting therapy, PP3M appears to be a good alternative anti-psychotic treatment.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic, incurable disease that afflicts a sizable proportion of people around the world, but rates vary across regionsCitation1. In a comprehensive literature review involving 46 countries, Saha et al.Citation2 estimated a point prevalence of 4.6/1,000, with a range of 1.9 (10% quantile) to 10.0% (9% quantile). Worldwide, the estimated number of cases was 21.5 million in 2010Citation1. Using population statistics from 2010Citation3, there were 6,892 million people, making the global prevalence of schizophrenia 3/1,000 inhabitants. The average annual incidence is 15 per 100,000, with a range of 7.7–43.0 per 100,000Citation4,Citation5.

In Spain, the estimated prevalence of schizophrenia as reported in 2006 was 3.00/1,000 in males and 2.86/1,000 in femalesCitation6. However, a more recent publication in 2016 estimated rates of 5.88/1,000 in males and 2.20/1,000 in femalesCitation7. The estimated incidence reported in 2006 was eight cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year overall, 8.4 for males and 8.0 for femalesCitation6. The annual incidence reported in 2008 was 13.8 per 100,000 inhabitants, with a male:female ratio of 1.61Citation8.

It manifests with both positive and negative symptoms, as well as cognitive, mood, and motor symptoms, whose intensities vary between individuals and over the course of timeCitation5,Citation9. Positive symptoms are florid, such as delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized thinking. Negative symptoms present as deficits in cognitive, affective, and social functioning, as well as passive withdrawalCitation10.

Schizophrenia adversely affects patients, decreasing their quality-of-life and level of functioningCitation11,Citation12. As well, their lifespan is shortened; men live 15 years less and women live 12 years less than their counterparts who do not have schizophreniaCitation13. Suicide and other violence claims ∼40% of the lives lostCitation14,Citation15. The largest proportion of people with schizophrenia die from cardiovascular disease (33%), followed by cancer (15%), respiratory problems (13%), and infections (10%)Citation16. It appears that risk factors for these diseases are increased in schizophrenia. In a recent review of the literature, Azad et al.Citation14 concluded that rates of death due to cardiovascular disease were 90% higher than in the general population. Another risk factor, smoking, is highly prevalent in schizophrenia. Hughes et al.Citation17 reported that 88% smoked, while Smith et al. (2014)Citation77 found that 69.1% smoked, as compared with 30–33% among non-schizophrenics. Hartz et al.Citation18 reported that those with schizophrenia had 4.6-times more smoking, 4-times more heavy alcohol use, and 3.5-times more drug abuse than non-schizophrenics. Major problems arise not only from the lifestyle of persons with schizophrenia, but examinations of the care provided to those with cardiovascular disease indicated lower levels were provided. For example, cardiac catheterizations were only 41% compared with the general populationCitation19. Also, they are less likely to be diagnosed and treated than are those without psychiatric comorbidityCitation20.

This disease also creates a large burden on both society and healthcare systemsCitation1,Citation21,Citation22. Particularly affected are the families and caregivers, whose burden is substantialCitation23–25. The average patient requires 48 hours of care per monthCitation26, but patients with more severe symptoms may require 70 hours per weekCitation25. The average caregiver incurs 2,258€ in direct costs and 6,667€ in indirect costs, for a total of 8,925€per annumCitation23. Additionally, caregivers suffer from decreased health, professional, family, and social interactionsCitation23,Citation25. In Spain, direct medical costs for schizophrenia constitute 53% of the total, and informal care costs are the other 47%. Hospitalization comprises 73% of the direct costs (38.5% of the total, including indirect/informal costs); drugs are responsible for 24% of the direct costs (12.8% of total), and outpatient care the remainder (∼3%)Citation26.

An association has been established between resource consumption by individuals with schizophrenia and non-adherence or partial adherence to treatmentCitation27,Citation28. Using electronic monitoring on a group of 102 out-patients in Spain, Acosta et al.Citation29 reported that 42.3% of schizophrenia patients exhibited “non-compliant behaviors”. Those who were non-adherent displayed poor insight, conceptual disorganization, stereotyped thinking, and poor attention. Furthermore, they found that psychiatrists, patients, and relatives all over-estimated rates of adherence to prescribed medications. The reported sensitivity (identifying compliers) was 96%, 100%. and 98% for psychiatrists, patients, and relatives, respectively. However, specificity (identification of non-compliers) was only 22%, 5%, and 5%, respectively. Agreement with the MEMS results was only fair for psychiatrists (kappa = 0.24) and slight for patients (kappa = 0.082), and relatives (kappa = 0.069). Another Spanish group examined the relationship between non-adherence and hospitalizations, as well as their associated costsCitation30. They found that poor adherence to anti-psychotics was associated with increased hospitalizations, resource consumption, and direct healthcare costs.

In an effort to address the problem of partial or non-adherence, depot formulations were developed several decades ago. The first were the phenothiazines, then butyrophenones, which have varying administration intervalsCitation31. However, the frequent appearance of adverse events, especially movement disorders, prompted a shift away from the typicals to the atypicals, in all formsCitation32. The atypicals have fewer such effects, but can induce weight gain and metabolic problemsCitation33.

Among the atypical anti-psychotics, risperidone microspheres (Risperdal Consta) was the first to be approved for use in Spain, on February 26, 2003Citation34. It must be administered every 2 weeks. In the subsequent years, longer acting therapies (LATs) appeared, such as paliperidone palmitate (Xeplion, Invega Sustenna) in 2011Citation35, which could be administered monthly into either the gluteal or deltoid muscle.

The administration interval for paliperidone has been further increased to 3 months with the introduction of Trevicta (Invega Trinza in the US; Janssen Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium; PP3M)Citation36. These products have the same drug as their active ingredient, but vary in the interval of administration. Gopal et al.Citation37 have demonstrated that the 3-month formulation is equipotent to the 1-month formulation over 3 months when dosed at 3.5-times the 1-month dosage. However, the cost-effectiveness of this new 3-month formulation relative to the 1-month product is presently unknown. Therefore, the aim of this project was to determine their relative cost-effectiveness in persons with chronic schizophrenia in Spain.

Methods

In performing this research, we followed the recommendations for the economic evaluation of health technologies in SpainCitation38. The intended audience consisted of healthcare decision-makers in Spain and psychiatrists managing the pharmacotherapy of Spanish patients with chronic schizophrenia. The analyses took the perspective of the Spanish National Health System (NHS), as per the recommendations.

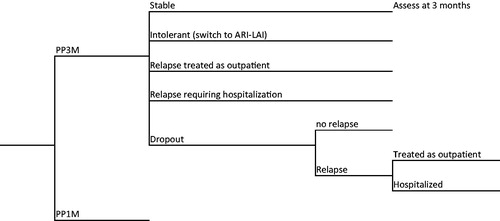

The primary focus was on PP3M, with PP1M as the comparison drug, as reported in a recent trialCitation39. These two drugs have the same active ingredient, but different durations of action (3 months vs 1 month). For analysis of the data, we used a decision tree model, which is depicted in . The analysis was conducted on an Excel spreadsheet, over an analytic time horizon of 1 year. The primary clinical inputs were derived from the trial by Savitz et al.Citation39. This was a double-blind, randomized trial that compared PP3M with PP1M head-to-head over 48 weeks after a 17-week PP1M stabilization phase.

In order to model the consequences and costs of treatments, additional information was obtained from a variety of sources. Local experts provided inputs on care management. Other information was derived from published literature. For PP3M and PP1M, success rates, switches, and relapses (including hospitalizations and non-hospitalized relapses), and dropout rates were those observed in the Savitz et al.Citation39 trial. To estimate the time to relapse in those who discontinued from the drugs, we used the placebo data from Kim et al.Citation40. Those authors calculated relapse rates for three forms of paliperidone (oral, PP1M, and PP3M) drug over time. We used those placebo data to model the course of schizophrenia in patients who discontinued. Since all patients had been stabilized on their respective drugs, it is reasonable to assume that these values are a good proxy for discontinuers, and would provide valid inputs for the model.

Patients who dropped out were considered not to consume resources until they relapsed. To determine relapse rates and times for those patients, we used the data for placebos from Kim et al.Citation40. If there was a lack of efficacy, patients would be titrated to the maximum dose. According to the clinical experts, all patients who experienced adverse events were switched to second line treatment, which was aripiprazole long-acting therapy (ARI-LAT) for both PP3M and PP1M, with clinical data derived from Kane et al.Citation41. In the event of intolerance to or lack of efficacy from the second line drug, patients would be switched to clozapine, as per NICE recommendationsCitation42. Clinical inputs are presented in , along with their values and sources for the data.

Table 1. Annual rates and regimens used in the analysis.

We considered only the direct costs from the perspective of the payer. Prices of these resources were obtained from official lists issued by various governmental agencies in Spain. These prices appear in , and are all expressed in 2016 euros. Estimates of resources costed in previous years were adjusted to 2016 values via the Consumer Price Index for SpainCitation43.

Table 2. Costs of resources used in the analysis.Table Footnote*

Utilities were derived from the paper by Osborne et al.Citation44, who measured preferences using the time trade-off approach. It is the only available paper that measured the utility, based on patient preference, of a 3-month formulation for schizophrenia. They estimated a utility of 0.27 for patients in full relapse; for patients in a stable state, the estimated utilities were 0.70 and 0.65 for PP3M and PP1M, respectivelyCitation44. We assumed that utilities for ARI-LAT were the same as for PP1M, based on the analysis by Tempest et al.Citation45, wherein the annual QALY scores were only 1.2% different (0.727 vs 0.717). To determine the utility for non-hospitalized relapses, we used the mid-point between stable disease and relapse, as has been done by Druais et al.Citation46. That yielded a ratio of stable:non-hospitalized relapse that was virtually the same (1.38 vs 1.35) as we had determined in previous researchCitation47.

The analytic outcomes were both cost-effectiveness (i.e. incremental cost per relapse or hospitalization avoided) and cost-utility (i.e. incremental cost per QALY gained). Clinical outcomes were rates of relapse, including those treated as outpatients, those requiring hospitalization, and overall relapses.

To examine the model robustness and stability of results, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses adjusting inputs using various rates published in other studies. Rates altered included those for relapse, dropout, and switches due to adverse events. Other inputs varied were length of hospital stay (increased to 35 days as reported by Mede Herrero and Saria SantameraCitation48), doses of drugs (111.56, as administered in real-world practice, as reported by Gaviria et al.Citation49), and utilities (i.e. using PP3M values for all drugs and using previously used values)Citation47. Scenario analyses included using the Public Selling Price for drugs instead of the Ex-Factory price, eliminating dropouts, using switch rates from BerwaertsCitation52, and using placebo-adjusted relapse rates. One-way (break-even) analyses were done on all probabilities and cost inputs. We also performed a probability sensitivity analysis, varying all inputs within their plausible ranges using standard distributions. We used 10,000 simulations to provide a stable estimate of results.

Results

Primary results are presented in . PP3M had the lower cost of the two drugs (4,780€ vs 5,244€) and the greatest number of QALYs (0.6765 vs 0.6249); therefore, it dominated PP1M in the cost-utility analysis. PP3M was also associated with a lower number of total relapses (0.081 vs 0.160), as well as patients requiring hospitalization (0.036 vs 0.064), and patients relapsing but treated as outpatients (0.045 vs 0.096). Therefore, it also dominated PP1M in all of the cost-effectiveness analyses.

Table 3. Outcomes from the pharmacoeconomic analysis.

In 1-way sensitivity analyses, results were generally resistant to changes in all of the rates tested, including rates of hospitalization. In scenario analyses, PP3M remained dominant over PP1M in all but one case (). In the worst case scenario (i.e. when PP3M was used in its maximum dose of 414.75 mg (as in the LanzilloCitation50 trial, and PP1M was at its minimum of 75 mg/dose), PP1M would cost less than PP3M. However, PP3M remained cost-effective, with an ICER of 16,752€/QALY, which falls well below the accepted threshold in Spain of 30,000€/QALY.

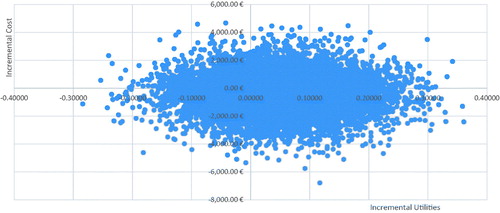

In probabilistic sensitivity analyses, PP3M was associated with more QALYs than PP1M in 72.8% of simulations, and had a lower cost in 64.3%. PP3M dominated PP1M in 46.9% of the 10,000 iterations, and was dominated in 9.8%. Overall, PP3M was cost-effective in 77.8% of the simulations. displays the results in a scatterplot.

Table 4. Results of scenario analyses.

In this analysis, the cost driver was the cost of the drugs, which comprised 76% and 71% of the total costs for PP3M and PP1M, respectively. Hospitalization accounted for 13% and 15%, respectively, while medical care was responsible for 11% and 14%, respectively.

With respect to adverse events, Savitz et al.Citation39 provided a thorough record of all events recorded during the trial (see Savitz et al., ). Overall, 68% of patients who received PP3M experienced side-effects, as compared with 66% of those on PP1M (p = .67). Serious adverse effects were reported in 5% of those on PP3M, compared with 7% for PP1m (p = .22). Pain at the injection site was noted in 2% with PP3M and 3% for PP1M (p = .77). Considering that PP3M is injected fewer times per year than is PP1M, it would have an advantage over PP1M.

Model validation

This model determined that PP3M was associated with 0.677 QALY, which closely reflects the value of 0.70 estimated by Osborne et al.Citation44. For PP1M, the model estimated 0.625 QALY, which was quite similar to the values of 0.611 and 0.667 determined by Druais et al.Citation46 and Furiak et al.Citation51, respectively. Also, the difference between PP3M and PP1M was 0.052 QALY, which corresponds with the value of 0.05 from Osborne et al.Citation44. Total relapses were 0.80 for PP3M, which is similar to the rate of 0.88 reported by Berwaerts et al.Citation52. For PP1M, the rate of 0.161 is essentially the same as the average of rates of 0.175 from Hough et al.Citation53 and 0.152 from Fu et al.Citation54.

Discussion

PP3M is the first formulation that provides effective treatment for schizophrenia over a 3-month period. This product was developed using the same Nanocrystal technology, as was used with PP1M, except that PP3M has a different particle size which causes the drug to be released over a longer period of timeCitation55–57. The half-life ranges from 84–139 days, depending on the dose and injection siteCitation58. Thus, after discontinuation from steady state, the drug can maintain a therapeutic blood level for ∼5–7 monthsCitation55.

This prolonged half-life serves to prevent missed doses, thereby reducing relapses. Clinically, Savitz et al.Citation39 demonstrated that PP3M did numerically decrease relapses compared with PP1M in a head-to-head trial. In the present research, we found a 50.2% reduction overall (including those due to dropouts and medication switches), but derived from different studies. Thus, the theoretical advantages are reflected in the clinical outcomes.

The 3-month treatment also provides benefits to both the healthcare system and the patient. Since drug administration is required only four times per year, nurses are freed to engage in other activities. Thus, it allows for a more efficient use of resources in an already overburdened system. For patients and their caregivers, less time is required to travel to clinics for drug administration. Also, less frequent administration reduces the pain associated with administration. There is less chance of relapsing while on the 3-month treatment, which results in an increased quality-of-life for patients as well as caregivers. In addition, there is less disruption of daily activities.

As of this writing, there have been three separate research projects involving the cost-effectiveness of PP3M, all of which appeared as postersCitation59–62. In the first, Benson et al.Citation61,Citation62 compared the 1-year costs of treating schizophrenia with either PP3M or placebo in the US in 2014. Clinical inputs were based on the randomized trial by Berwaerts et al.Citation52. Total costs were comparable in the open label phase, but increased for placebo in the double-blind phase, while it decreased for PP3M. Due to lower resource consumption, total overall costs were lower for PP3M, as were all clinical rates (i.e. relapses, hospitalizations, and emergency room visits). PP3M dominated placebo in that analysis. A limitation of their analysis was that drug costs were not included.

The present analysis used a different RCT to model than that used by Benson et al.Citation61. We used the head-to-head trial of Savitz et al.Citation39, which was also 1 year long. However, there was another difference in that patients who relapsed were censored in the Benson et al.Citation61 paper, and resources were not costed after that point. In our analysis, we costed all patients over a full year, including those switched to other drugs and those who dropped out. Most importantly, the calculations by Benson et al.Citation61 did not include drug costs, while the present analysis did, which explains the very large difference in reported costs.

In Belgium, De Moor et al.Citation60 utilized a Markov model with a 5-year time horizon to compare PP3M with PP1M. Clinical inputs were taken from two RCTs, which were Berwaerts et al.Citation52 and Hough et al.Citation53. The model was different in that second line therapy consisted of no active treatment, followed (when patients relapsed) by third line based on local prescribing patterns. They concluded that prescribing PP3M rather than PP1M would increase quality-of-life and save money. A similar model was used in France by Arteaga Duarte et al.Citation59, which produced similar results. Again, our model differed in structure and duration.

Limitations

The time horizon was 1 year, but the disease lasts indefinitely. It is possible that results could be different over a longer time period. Therefore, a lifetime model would be more appropriate for determining long-term outcomes. However, at present, there are no data available beyond 1 year for PP3M.

Another limitation is that the data were derived from clinical trials, in which patients are closely monitored and adherence to prescribed regimens is assured. The situation could be different in “real world” clinical practice, where a host of other factors come into play, such as concomitant diseases and drugs, and impaired body functions.

These results have been determined within the context of the Spanish healthcare system. Thus, they are dependent upon the approach to managing schizophrenia in that country and their method of financing care. Extrapolation to other countries would require adaptation.

We considered only the direct costs of care that would be paid by the Spanish NHS. With respect to lost productivity, Vázquez-Polo et al.Citation63 determined (1997 estimate) that 20.51% of all persons with schizophrenia were employed either full time or part time, while 76.51% received social assistance. In a more recent publication from Norway, Evensen et al.Citation64 estimated that the employment rate among working-age (i.e. 18–66) individuals with schizophrenia was 10.24%. That estimate also included people with all severities of the disease. Another recent paper from Israel that examined patients with multiple hospital admissions reported that a mere 5.8% of patients with schizophrenia were earning minimum wage or aboveCitation65. Thus, the difference in indirect costs between drugs is likely to be very small.

In addition, this analysis did not include the costs of treating adverse events. Reasons were that they comprise a very small amount of the total cost and are very similar between drugs, and due to the short time horizon. For example, a recent economic analysis from the UK examining both PP1M and ARI-LAT (as well as other LATs) included these costs. The total discounted costs of care per patient over 10 years ranged from £157,594–£163,359, while the total costs of treating adverse events for 10 years ranged from £153–£190. That is, the cost of managing AEs ranged from 0.10% (1/10 of 1%) to 0.12%, which is negligible and virtually equal between drugsCitation45. Similarly, when summarizing their costs between PP3M and PP1M, De Moor et al.Citation60 also concluded that “The largest cost component ws the relapse costs, while adverse events contributed only marginally”.

Conclusions

In the present analysis, PP3M was cost-effective, dominating PP1M in all cost-effectiveness analyses, as well as the cost-utility analysis. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the base case results. The major cost driver was the cost of the primary drugs (78% and 74%, respectively), which differs from previous analyses that found hospitalization to be the driver. As a conclusion, PP3M could represent a better treatment option for long term-treatment of chronic schizophrenia patients in the Spanish NHS. A limitation was that the model depended on data derived from randomized controlled trials. We still need observational studies to examine the situation under actual clinical conditions in practice.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was funded by grant sponsor Janssen Pharmaceuticals grant sponsor NV, Beerse, Belgium.

Declaration of financial/other interests

TE and BB received funding for the research and manuscript. IGL, BGMM, FT, and KVI are all employees of Janssen. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

References

- Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Degenhardt L, et al. The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: an analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS One 2015;10:e0116820

- Saha S, Chant D, Welham JJM. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med 2005;2:e141

- Population Reference Bureau. 2010 world population data sheet. http://www.prb.org/pdf10/10wpds_eng.pdf. Accessed May 21, 2017

- McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, et al. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev 2008;30:67-76

- Tandon R, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA. Schizophrenia, "just the facts" what we know in 2008. 2. Epidemiology and etiology. Schizophr Res 2008;102:1-18

- Ayuso-Mateos JL, Gutierrez-Recacha P, Haro JM, et al. Estimating the prevalence of schizophrenia in Spain using a disease model. Schizophr Res 2006;86:194-201

- Moreno-Küstner B, Mayoral F, Navas-Campaña D, et al. Prevalence of schizophrenia and related disorders in Malaga (Spain): results using multiple clinical databases. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2016;25:38-48

- Pelayo-Terán JM, Pérez-Iglesias R, Ramírez-Bonilla M. Epidemiological factors associated with treated incidence of first-episode non-affective psychosis in Cantabria: insights from the Clinical Programme on Early Phases of Psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry 2008;2:178-87

- Tandon R, Nasrallah HA, Keshavan MS. Schizophrenia, “just the facts” 4. Clinical features and conceptualization. Schizophr Res 2009;110:1-23

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987;13:261-76

- Haro JM, Altamura C, Corral R, et al. Understanding the impact of persistent symptoms in schizophrenia: Cross-sectional findings from the Pattern study. Schizophr Res 2015;169:234-40

- Haro JM, Novick D, Perrin E, et al. Symptomatic remission and patient quality of life in an observational study of schizophrenia: is there a relationship? Psychiatry Res 2014;220:163-9

- Crump CWM, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: a Swedish national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:324-33

- Azad MC, Shoesmith WD, Al Mamun M, et al. Cardiovascular diseases among patients with schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatry 2016;19:28-36

- Ringen PA, Engh JA, Birkenaes AB, et al. Increased mortality in schizophrenia due to cardiovascular disease - a non-systematic review of epidemiology, possible causes, and interventions. Front Psychiatry 2014;5:137

- Harris EC, Barraclough B. Excess mortality of mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1998;173:11-53

- Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK, Mitchell JE, et al. Prevalence of smoking among psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1986;143:993-7

- Hartz SM, Pato CN, Medeiros H. Comorbidity of severe psychotic disorders with measures of substance use. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:248-54

- Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA 2000;283:506-11

- Smith DJ, Langan J, McLean G, et al. Schizophrenia is associated with excess multiple physical-health comorbidities but low levels of recorded cardiovascular disease in primary care: cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii:e002808

- Nicholl D, Akhras KS, Diels J, et al. Burden of schizophrenia in recently diagnosed patients: healthcare utilisation and cost perspective. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:943-55

- Baca-Garcia E, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Basurte-Villamor I, et al. Patterns of mental health service utilization in a general hospital and outpatient mental health facilities: analysis of 365,262 psychiatric consultations. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2008;258:117-23

- Gupta S, Isherwood G, Jones K, et al. Productivity loss and resource utilization, and associated indirect and direct costs in individuals providing care for adults with schizophrenia in the EU5. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2015;7:593-602

- Awad AG, Voruganti LN. The burden of schizophrenia on caregivers: a review. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:149-62

- Aranda-Reneo I, Oliva-Moreno J, Vilaplana-Prieto C, et al. Informal care of patients with schizophrenia. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2013;16:99-108

- Oliva-Moreno J, López-Bastida J, Osuna-Guerrero R, et al. The costs of schizophrenia in Spain. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:182-8

- Novick D, Haro JM, Suarez D, et al. Predictors and clinical consequences of non-adherence with antipsychotic medication in the outpatient treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2010;176:109-13

- Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:886-91

- Acosta FJ, Bosch E, Sarmiento G, et al. Evaluation of noncompliance in schizophrenia patients using electronic monitoring (MEMS) and its relationship to sociodemographic, clinical and psychopathological variables. Schizophr Res 2009;107:213-17

- Dilla T, Ciudad A, Alvarez M. Systematic review of the economic aspects of nonadherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with schizophrenia. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013;7:275-84

- Adams CE, Fenton MK, Quraishi S, et al. Systematic meta-review of depot antipsychotic drugs for people with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2001;179:290-9

- Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013;382:951-62

- Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, et al. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:31-41

- Evaluate Group. 2003. Alkermes announces risperdal consta approved in Spain. http://www.evaluategroup.com/Universal/View.aspx?type=Story&id = 37484. Accessed March 17, 2016

- European Medicines Agency. 2011. Xeplion authorization details. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002105/human_med_001424.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d125. Accessed March 17, 2016

- Lamb YN, Keating GM. Paliperidone palmitate intramuscular 3-monthly formulation: a review in schizophrenia. Drugs 2016;76:1559-66

- Gopal S, Vermeulen A, Nandy P, et al. Practical guidance for dosing and switching from paliperidone palmitate 1 monthly to 3 monthly formulation in schizophrenia. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:2043-54

- López-Bastida J, Oliva J, Antoñanzas F, et al. Spanish recommendations on economic evaluation of health technologies. Eur J Health Econ 2010;11:513-20

- Savitz AJ, Xu H, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate 3-month formulation for patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, noninferiority study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2016;19

- Kim E, Berwaerts J, Turkoz I, et al. Time to schizophrenia relapse in relapse-prevention studies of antipsychotics developed for administration daily, once monthly, and every 3 months. Presented at the 15th International Congress on Schizophrenia Research, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, March 28–April 1, 2015

- Kane JM, Sanchez R, Perry PP, et al. Aripiprazole intramuscular depot as maintenance treatment in patients with schizophrenia: a 52-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:617-24

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The NICE guidelines on core interventions in the treatment and management of schizophrenia in adults in primary and secondary care. London: NICE; 2010

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Consumer Price Index. http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=MEI_PRICES. Accessed March 19, 2016

- Osborne RH, Dalton A, Hertel J, et al. Health-related quality of life advantage of long-acting injectable antipsychotic treatment for schizophrenia: a time trade-off study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:35

- Tempest M, Sapin C, Beillat M, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of aripiprazole once-monthly for the treatment of schizophrenia in the UK. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2015;18:185-200

- Druais S, Doutriaux A, Cognet M, et al. Cost effectiveness of paliperidone long-acting injectable versus other antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in France. Pharmacoeconomics 2016;34:363-91

- Einarson TR, Maia-Lopes S, Goswami P, et al. Economic analysis of paliperidone long-acting injectable for chronic schizophrenia in Portugal. J Med Econ 2016;19:913-21

- Mede Herrero A, Saria Santamera A. Hospital indicators by regional communities, 1980–2004. Longitudinal analysis of morbidity indicators and hospital staffing in mental health. Actas Esp Psichiatr 2009;37:82-93

- Gaviria AM, Franco JG, Aguado V. A non-interventional naturalistic study of the prescription patterns of antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia from the Spanish province of Tarragona. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139403

- Lanzillo R, Orefice G, Prinster A, et al. Predictive factors of neutralizing antibodies development in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients on interferon Beta-1b therapy. Neurol Sci 2011;32:287-92

- Furiak NM, Ascher-Svanum H, Klein RW, et al. Cost-effectiveness of olanzapine long-acting injection in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia in the United States: a micro-simulation economic decision model. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:713-30

- Berwaerts J, Liu Y, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of the 3-month formulation of paliperidone palmitate vs placebo for relapse prevention of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:830-9

- Hough D, Gopal S, Vijapurkar U. Paliperidone palmitate maintenance treatment in delaying the time-to-relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res 2010;116:107-17

- Fu DJ, Turkoz I, Simonson RB, et al. Paliperidone palmitate once-monthly reduces risk of relapse of psychotic, depressive, and manic symptoms and maintains functioning in a double-blind, randomized study of schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:253-62

- Ravenstijn P, Remmerie B, Savitz A, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of paliperidone palmitate 3-month formulation in patients with schizophrenia: A phase-1, single-dose, randomized, open-label study. J Clin Pharmacol 2016;56:330-9

- Leng D, Chen H, Li G, et al. Development and comparison of intramuscularly long-acting paliperidone palmitate nanosuspensions with different particle size. Int J Pharm 2014;472:380-5

- Park EJ, Amatya S, Kim MS, et al. Long-acting injectable formulations of antipsychotic drugs for the treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Pharm Res 2013;36:651-9

- US Food and Drug Administration. 1993. Drug approval package: Betaseron (Chiron Corp.). http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/pre96/103471s0000TOC.cfm. Accessed August 2, 2016

- Arteaga Duarte C, Guillon P, Fakra E, et al. Three-monthly long-acting formulation of paliperidone palmitate is a dominant treatment option, cost saving while adding QALYs, compared to the one-monthly formulation in the treatment of schizophrenia in France. Poster PRM115. Presented at the ISPOR 19th Annual European Congress, Vienna, Austria, October 29–November 2, 2016. Value Health 2016;19:A378

- De Moor R, Malfait B, Tedouri F, et al. Three-monthly long-acting formulation of paliperidone is a dominant treatment option, cost saving while adding QALYs, compared to the one-monthly formulation in the treatment of schizophrenia in Belgium. Poster PMH28. Presented at the ISPOR 19th Annual European Congress, Vienna, Austria, October 29–November 2, 2016 Value Health 2016;19:A526

- Benson C, Chirila C, Graham J, et al. Health resource use and cost analysis of schizophrenia patients participating in a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, relapse-prevention study of paliperidone palmitate 3-month formulation. Presented at the ISPOR 20th Annual International Meeting; May 16–20, 2015; Philadelphia, PA; 2015

- Benson C, Chirila C, Graham J, et al. PMH27 Health resource use and cost analysis of schizophrenia patients participating in a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, relapse-prevention study of paliperidone palmitate 3-month formulation. ISPOR 2015;18:A119

- Vázquez-Polo FJ, Negrín M, Cabasés JM, et al. An analysis of the costs of treating schizophrenia in Spain: a hierarchical Bayesian approach. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2005;8:153-65

- Evensen S, Wisløff T, Lystad JU, et al. Prevalence, employment rate, and cost of schizophrenia in a high-income welfare society: a population-based study using comprehensive health and welfare registers. Schizophr Bull 2016;42:476-83

- Davidson M, Kapara O, Goldberg S, et al. A nation-wide study on the percentage of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients who earn minimum wage or above. Schizophr Bull 2016;42:443-7

- European Medicines Agency. 2015. Xeplion® summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002105/WC500103317.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2016

- European Medicines Agency. 2016. Abilify Maintena® summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002755/WC500156111.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2016

- Haro JM, Salvador-Carulla L, Cabasos J, et al. Utilisation of mental health services and costs of patients with schizophrenia in three areas of Spain. BJP 1998;173:334-40

- Mede A, Sarria A. Hospital indicators by Regional Communities, 1980–2004 (Longitudinal analysis of morbidity indicators and hospital staffing in mental health). Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2009;37:82-93

- Peiró S, Gómez G, Navarro M, et al. Length of stay and antipsychotic treatment costs of patients with acute psychosis admitted to hospital in Spain. Description and associated factors. The Psychosp study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2004;39:507-13

- Salize HJ, McCabe R, Bullenkamp J, et al. Cost of treatment of schizophrenia in six European countries. Schizophr Res 2009;111:70-7

- Salvador-Carulla L, Haro JM, Cabasés J, et al. Service utilization and costs of first-onset schizophrenia in two widely differing health service areas in North-East Spain. PSICOST Group. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999;100:335-43

- Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmaceuticos. http://botplusweb.portalfarma.com/botplus.aspx. Accessed December 12, 2016

- Diario Oficial de Galicia. https://edog100.xunta.es/dogPublicador/loginPublicador.do;jsessionid=bdhQYSSGzGBpMn6HhNQ9xCy29ZP-qDjCFFyGpY5MsY1PBLMQXlrYW!34097549!-309920421?method=loginPublicadorI

- García-Ruiz AJ, Pérez-Costillas L, Montesinos AC, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of antipsychotics in reducing schizophrenia relapses. Health Econ Rev 2012;2:doi: 10.1186/2191-1991-1182-1188

- Quintero J, Oyagüez I, González B, et al. Cost-minimisation analysis of paliperidone palmitate long-acting treatment versus risperidone long-acting treatment for schizophrenia in Spain. Clin Drug Investig 2016;36:479-90

- Smith PH, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Smoking and mental illness in the U.S. population. Tob Control 2014;23:e147-53