Abstract

Background: Sarcoidosis is a multi-system inflammatory disorder characterized by the presence of non-caseating granulomas in involved organs. Patients with sarcoidosis have a reduced quality-of-life and are at an increased risk for several comorbidities. Little is known about the direct and indirect cost of sarcoidosis following the initial diagnosis.

Aims: To provide an estimate of the healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and costs borne by commercial payers for sarcoidosis patients in the US.

Methods: Patients with a first diagnosis of sarcoidosis between January 1, 1998 and March 31, 2015 (“index date”) were selected from a de-identified privately-insured administrative claims database. Sarcoidosis patients were required to have continuous health plan enrollment 12 months prior to and following their index dates. Propensity-score (1:1) matching of sarcoidosis patients with non-sarcoidosis controls was carried out based on a logistic regression of baseline characteristics. Burden of HCRU and work loss (disability days and medically-related absenteeism) were compared between the matched groups over the 12-month period following the index date (“outcome period”).

Results: A total of 7,119 sarcoidosis patients who met the selection criteria were matched with a control. Overall, commercial payers incurred $19,714 in mean total annual healthcare costs per sarcoidosis patient. The principle cost drivers were outpatient visits ($9,050 2015 USD, 46%) and inpatient admissions ($6,398, 32%). Relative to controls, sarcoidosis patients had $5,190 (36%) higher total healthcare costs ($19,714 vs $14,524; p < 0.001). Sarcoidosis patients also had significantly more work loss days (15.9 vs 11.3; p < 0.001) and work loss costs ($3,288 vs $2,527; p < 0.001) than matched controls. Sarcoidosis imposes an estimated total direct medical cost of $1.3–$8.7 billion to commercial payers, and an indirect cost of $0.2–$1.5 billion to commercial payers in work loss.

Conclusions: Sarcoidosis imposes a significant economic burden to payers in the first year following diagnosis.

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a multi-system inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology. The disease is characterized by the presence of non-caseating granulomas in involved organsCitation1,Citation2. More than 90% of sarcoidosis patients have disease localized to the lungs; less commonly affected organs include the skin, lymph nodes, the eye, and the liverCitation3. Symptoms of sarcoidosis depend on the organ involved, but tend to be mild, and may include cough, fever, fatigue, joint aches and pain, or arthritisCitation4. In more advanced cases, sarcoidosis can cause significant pulmonary morbidity and occasionally be fatalCitation5.

The incidence of sarcoidosis in the US has been estimated at 17.4 cases per 100,000 persons, although up to 42% of cases are clinically undetectedCitation6. Sarcoidosis tends to occur in young adults (median age of onset is ∼40 years) and is thought to be related to both gender and raceCitation7. Although the exact cause of sarcoidosis is unknown, it is thought that, among genetically susceptible individuals, sarcoidosis is exacerbated by environmental, occupational, and infectious agentsCitation8. Because the aetiology of sarcoidosis is unknown, and sarcoidosis can be difficult to distinguish from other diseases, diagnosis of sarcoidosis can take several months and typically involves imaging tests and tissue biopsies to rule out other diseasesCitation9.

Patients diagnosed with sarcoidosis are at an increased risk for a number of comorbidities. Studies have found that sarcoidosis is associated with depression, interstitial lung disease, skin disorders, uveitis, bone and joint involvement, and cardiac complicationsCitation3,Citation10–13.

Little is known, however, about the burden of sarcoidosis, both in terms of healthcare resource utilization and in terms of the overall costs borne to payers, either in the short- or long-term following diagnosis. The objective of this study was to provide an estimate of the healthcare resource use and costs of sarcoidosis in the US. This study also assessed incremental indirect work loss burden attributable to sarcoidosis. Findings from this study were then extrapolated to achieve an estimate of the direct and indirect economic burden of sarcoidosis in the US.

Patients and methods

Overview

To assess the healthcare resource use and costs associated with sarcoidosis, this study used de-identified administrative claims records from a database for privately-insured populations. Resource use was estimated for sarcoidosis patients and a control group without sarcoidosis. The incremental healthcare resource use and associated costs were assessed using a matched case-control study design to account for differences in patient demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as prior healthcare resource use and costs between the sarcoidosis cases and non-sarcoidosis controls.

Data sources

This study used de-identified administrative claims from OptumHealth Care Solutions, Inc., a database containing healthcare utilization records of over 19.1 million beneficiaries (including employees, spouses, dependents, and retirees) with commercial insurance from over 84 large self-insured US-based companies. The database contains information regarding patient age, gender, enrollment history, medical diagnoses, procedures performed, dates and place of service, and payment amounts for the time period spanning January 1, 1998 to March 31, 2015. Prescription drug claims (including fill dates, national drug codes, and payment amounts) are available for all beneficiaries. Information regarding wages and work loss due to disability are available for a sub-set of employees.

Sample selection

Patients from the administrative claims database were divided into two mutually exclusive groups: patients with at least one diagnosis of sarcoidosis and patients without a diagnosis of sarcoidosis (“controls”), with sarcoidosis diagnosis identified by ICD-9 CM diagnosis code 135.xx during the study period (January 1, 1998–March 31, 2015). Given the large size of the overall control group (over 14 million patients), a 10% sample selected using a random number generator was used as a statistically valid control sample.

The earliest sarcoidosis diagnosis during the study period was designated as the “index date” for patients in the sarcoidosis group. By definition, patients in the control group did not have a sarcoidosis diagnosis at any time before or after the index date; therefore, a random medical claim occurring during the study period was selected and assigned as the index date for these patients. Patients were required to be aged 18–64 on the index date and have continuous insurance coverage throughout the 12 months prior to the index date (“baseline period”) and the 12 months following the index date (“outcome period”), to ensure that all relevant drug and medical claims were captured. Patients aged 65 years and older were excluded from the study, as their Medicare eligibility may have limited the ability to observe all relevant drug and medical claims.

Propensity score matching

To account for the underlying differences between the two groups and provide an unbiased estimation of the incremental resource use and cost of disease, sarcoidosis patients were matched one-to-one to potential non-sarcoidosis controls, based on several factors assessed during the baseline period. Each patient in the sarcoidosis groups was matched to a patient in the control group with the same Charlson Comorbidity IndexCitation14 (a composite measure of the patient’s health status) and propensity score (± 1/8 standard deviation) using a “greedy” matching methodologyCitation15. This approach, which is commonly used in matched healthcare utilization studiesCitation16–20, selects a patient among the eligible controls for each subsequent sarcoidosis patient, based on the nearest propensity score. Propensity scores were calculated for patients using a multivariate logistic regression with the following covariates measured at baseline: age, gender, region, year of index date (to account for differences in utilization and treatment patterns over time), number of medical visits (emergency department, inpatient, outpatient, other), number of prescriptions filled, total medical costs, and total prescription drug costs. To facilitate comparisons of work loss, matched pairs were also required to have the same availability of work loss data. The observed baseline characteristics of the two groups were evaluated post-match to assess whether there was any enduring imbalances, as assessed by standardized differences.

Study measures

Total and incremental all-cause healthcare resource utilization and cost in the 12-month outcome period were compared for sarcoidosis patients and non-sarcoidosis controls. Costs borne by commercial payers were calculated using the insurer paid amount field contained on medical and pharmacy claims. Resource utilization and cost were categorized by place of service to identify sources of differential utilization. Place of service categories included the following: inpatient, outpatient/physician office, emergency department (ED), and other (e.g. skilled nursing facilities, home health). In addition, utilization of selected medical specialists known to care for sarcoidosis patients (e.g. pulmonologist, ophthalmologist, cardiologist, rheumatologist, nephrologist) was assessed.

Total and incremental work loss and work loss costs due to disability and medically-related absenteeism during the outcome period were estimated for the sub-set of privately-insured patients with disability and wage information available. Days of short- and long-term disability leave were obtained directly from the database; medically-related absenteeism days were estimated using medical claims occurring during the workweek. Each hospitalization day or ED visit accounted for a full day of missed work; all other visits accounted for half a day of absenteeismCitation20. Medically-related absenteeism costs were imputed by multiplying the number of days of missed work by the daily benefits received (disability) or wage (absenteeism). Direct and indirect costs were inflated to 2015 USD (the last year of the data availability) using the medical cost component and the all items cost component of the Consumer Price Index, respectively.

Select sarcoidosis-related clinical characteristics that were present during the 12-month outcome period, as identified by using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes, were reported. The prevalence of comorbidities common among patients with sarcoidosis (e.g. primary hypertension, chronic pulmonary disease, interstitial lung disease, uveitis) were summarized and compared across groups.

Statistical analyses

Standardized differences were used for comparing baseline covariates in the pre-match groups, as well as to assess if there were any enduring differences in the post-match groups. Following guidance of prior researchCitation20,Citation21, statistical significance of outcome covariates in the post-match groups was assessed using the McNemar test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Extrapolation to a national burden estimate

The per-patient costs during the outcome period were used to estimate the total and incremental direct medical cost burden sarcoidosis patients impose on commercial payers in the US. The national estimate is based on the US population of adults with commercial insurance between the ages of 18–64, inclusively. The calculation relies on the following components: prevalence of sarcoidosis in the US, derived from recent literature; the number of persons between the ages of 18–64 in the US that are covered by commercial insurance, based on data from the US Census Bureau and the National Health Insurance SurveyCitation22,Citation23, and the total and incremental healthcare cost for sarcoidosis, based on the results of the annual cost analysis in the matched groups, described above. The total and incremental indirect medical cost burden of sarcoidosis in the US was estimated using a similar extrapolation method; the calculation relied on an additional component: the employment rate among the US civilian non-institutional population of persons between the ages of 18–64 years, based on data from the Bureau of Labor StatisticsCitation24.

Results

Sample selection

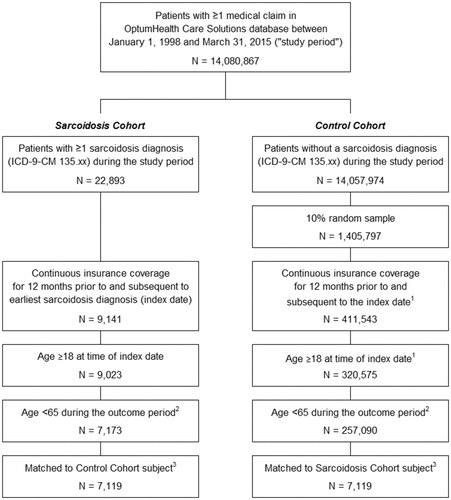

In the OptumHealth Care Solutions database, there were 22,893 patients with at least one diagnosis of sarcoidosis during the study period, and 1,405,797 patients without sarcoidosis retained in the 10% random sampling (). After applying all of the sample selection criteria, 7,173 sarcoidosis patients and 257,090 potential non-sarcoidosis control patients were included in the study. Propensity-score matching resulted in a final matched sample of 7,119 sarcoidosis patients and 7,119 non-sarcoidosis control patients.

Figure 1. Selection of sarcoidosis patients and non-sarcoidosis controls. (1) The index date for the Control Cohort was defined as a randomly selected medical claim occurring during the study period. (2) The outcome period is defined as the 12-month period beginning on the index date. (3) A greedy matching algorithm was used to match each sarcoidosis patient with a control patient, based on propensity score and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), a composite measure of the patient’s health status. Propensity scores were estimated using a multivariate logistic regression with the following covariates (measured during the 12-month period preceding the index date): age, gender, region, index year (categorical variable), number of medical visits (inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, other), number of prescriptions filled, medical costs, and prescription drug costs. Matched pairs were required to have the same CCI score and availability of work loss data.

Baseline characteristics

Prior to matching, sarcoidosis patients were substantially different from the non-sarcoidosis controls on every measure examined during the 12-month baseline period (). Compared with non-sarcoidosis controls, sarcoidosis patients were older (49.4 vs 43.4 years), more often female (58.6% vs 51.4%), and more likely to be from Southeastern and Midwestern parts of the US. Sarcoidosis patients had higher rates of chronic comorbidities, including chronic pulmonary disease (18.8% vs 6.3%), rheumatic disease (6.0% vs 1.0%), and congestive heart failure (3.4% vs 0.9%), compared with controls during the baseline period. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was 3-times higher for sarcoidosis patients compared with controls (0.9 vs 0.3).

Table 1. Patient characteristics, resource utilization, and healthcare costs during the 12 months prior to the index date.

Compared with the potential controls prior to matching, sarcoidosis patients had more inpatient admissions (+175%), ED visits (+80%), and outpatient/physician office visits (+70%) in the baseline period. These differences resulted in baseline medical care costs among sarcoidosis patients that were 2.4-times those of the potential control patients ($12,360 vs. $5,123).

After matching sarcoidosis patients with comparable controls, the 7,119 pairs of sarcoidosis and control patients had similar baseline demographics and comorbidities (). The matched sarcoidosis and control groups had similar healthcare utilization during the baseline period (18.6 vs 17.7 medical visits, 21.1 vs 21.3 prescriptions filled). The magnitude of the differences in the baseline total healthcare costs was also largely diminished due to matching ($13,840 vs $13,692). The absolute value of the standardized difference for the healthcare utilization and costs were less than 10%, signifying no meaningful imbalance between the matched groups.

Sarcoidosis-related comorbidities in the outcome period

Despite having similar clinical characteristics during the baseline period after matching, the sarcoidosis patients had significantly higher rates of comorbidities during the 12-month outcome period compared with matched controls (p < 0.001) (). Compared with controls, sarcoidosis patients had higher prevalence of essential (primary) hypertension (35.3%), interstitial lung disease (20.8% vs 2.5%), and uveitis (5.1% vs 0.4%) (p < 0.001 for all comparisons).

Table 2: Healthcare resource utilization and costs during the 12 months following the index date among matched sarcoidosis patients and controls.

Direct healthcare resource use and costs during the outcome period

Sarcoidosis patients had, on average, 4.2 more medical visits than matched controls during the 12-month outcome period (+22%), and each additional medical visit was associated with $1,236 in additional costs (). Sarcoidosis patients had significant increases in visits across all places of service compared with matched non-sarcoidosis controls: 37% more inpatient admissions (0.4 vs 0.3), 15% more ED visits (0.7 vs 0.6), and 22% more outpatient/physician office visits (18.8 vs 15.3). Sarcoidosis patients were significantly more likely to have visits with medical specialists, including pulmonologists (38.3% vs 5.1%), rheumatologists (13.4% vs 3.2%), and ophthalmologists (29.3% vs 15.2%). In addition, sarcoidosis patients filled, on average, 3.1 more prescriptions than matched non-sarcoidosis controls during the outcome period (25.5 vs 22.4 fills).

Commercial payers incurred $19,714 in total annual healthcare costs per sarcoidosis patient during the 12-month outcome period, $5,190 (36%) in excess of matched controls (). Sarcoidosis patients had 41% higher medical costs ($16,992 vs $12,055) and $253 more in prescription drug costs compared with matched controls. Over 50% of the incremental costs were due to outpatient/physician office visits ($9,050 for sarcoidosis patients vs $6,296 for control patients, differential of $2,754). Nearly 40% of the cost differential was due to inpatient admissions; each additional inpatient admission was associated with $18,980 in additional costs.

All aforementioned comparisons of healthcare resource use and costs in the outcome level were significant at the 0.001 level.

Disability and medically-related absenteeism during the outcome period

Work loss information was available for 1,922 of the 7,119 matched pairs (). On average, sarcoidosis patients had 4.6 days more of work loss than matched controls (15.9 vs 11.3 days): 2.9 more disability days (7.5 vs 4.6 days) and 1.8 more days of medically-related absenteeism (8.4 vs 6.7) (p ≤ 0.001). Sarcoidosis patients had $3,288 in annual work loss costs, 761 (30%) more than the non-sarcoidosis patients ($2,527) (p < 0.001).

Table 3. Work loss and work loss costs during the 12 months following the index date among matched sarcoidosis patients and controlsTable Footnotea,Table Footnoteb.

Estimated direct and indirect burden of sarcoidosis in the US

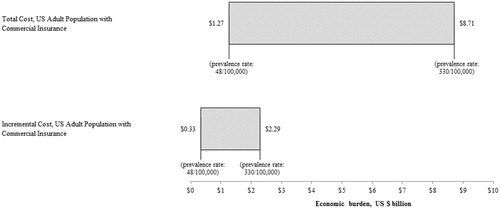

Based on estimates of prevalence ranging from 48–330 sarcoidosis cases per 100,000 persons in the USCitation25,Citation26, results suggest that sarcoidosis imposes a total direct medical cost burden of ∼ $1.3–$8.7 billion to commercial payers, or ∼ $0.3–$2.3 billion in excess costs over matched controls (). Results of this analysis also suggest that sarcoidosis patients impose an indirect cost burden of ∼ $0.2–$1.5 billion to commercial payers in work loss costs, or ∼ $0.1–$0.4 billion in excess work loss costs over matched controls.

Figure 2. Total and incremental economic burden of sarcoidosis among adults with commercial insurance in the US. (1) Total and incremental economic burden was estimated for the US population of adults with commercial insurance between the ages of 18–64), inclusively. Estimates of burden are presented in 2015 USD. (2) Calculations rely on the following assumptions: (a) Prevalence rates range from 48–330 sarcoidosis cases/100,000 personsCitation25; (b) US population of persons between the ages of 18–64 is 199.0 million (US Census Bureau 2014); (c) 67.3% of persons between the ages of 18–64 in the US are covered by commercial insurance (National Center for Health Statistics 2015); (d) Total healthcare cost for sarcoidosis is $19,714, and incremental healthcare cost is $5,190, based on the results of the annual cost analysis in the matched cohort.

Discussion

Of the 14 million privately-insured beneficiaries with a medical claim available in the administrative claims database between January 1, 1998 and March 31, 2015, 22,893 (∼0.16%) were diagnosed with sarcoidosis. The sarcoidosis patients identified for the analysis were ∼50 years of age, predominantly female, and had several chronic comorbidities. Prior to matching, sarcoidosis patients were statistically significantly older, had higher rates of comorbidities, and had more healthcare resource use and costs than the non-sarcoidosis control group. However, these differences were largely eliminated after matching; matched pairs had much more similar patient characteristics at baseline, which allowed for more precise estimation of incremental resource use and costs following the initial sarcoidosis diagnosis. During the 12-month follow-up period, sarcoidosis patients had statistically significantly higher healthcare resource use and costs (both medical and prescription drug), compared with matched control patients. Furthermore, this study found that, compared with non-sarcoidosis matched controls, sarcoidosis patients missed more days of work due to medically-related absenteeism and disability, imposing a larger economic burden on employers.

While this study found substantial resource use and costs among sarcoidosis patients, it likely understates the actual burden of sarcoidosis in the US. The study focuses on healthcare resource utilization and costs in the 12 months following sarcoidosis diagnosis—the healthcare resource use and costs may change (and likely increase) due to changes in disease severity beyond the outcome period evaluated in this study (e.g. long-term care, steroid resistant disease). Further, the matching process disproportionately removed sarcoidosis patients with relatively high healthcare resource use and control patients with relatively low healthcare resource use, as these “outliers” could not be matched. While the study shows significant average costs associated with sarcoidosis, additional analyses are warranted to assess the variation in costs within sarcoidosis patients and identify the predictors of high severity disease, as well as the predictors of high cost sarcoidosis patients.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the excess healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with newly-diagnosed sarcoidosis by employing robust methods to account for underlying differences between patients with and without sarcoidosis. Findings from this study are consistent with, although systematically lower than, estimates reported in Baughman et al.Citation27, a recent retrospective claims database analysis of incident and prevalent sarcoidosis in the US between 2010 and 2013. The Baughman et al.Citation27 study reports substantial costs associated with sarcoidosis, with average annual sarcoidosis-related medical costs of $32,032, 69% of which was accrued in an inpatient (acute care) setting. This higher cost estimate relative to our database study is consistent with a number of methodological differences, including differences in the study design and selected study population (i.e. newly diagnosed vs prevalent cases).

This study had limitations, inherent to the data used in the analysis. First, this study relied on the accuracy of diagnosis codes to identify patients with or without sarcoidosis and to evaluate their comorbidity profiles at baseline, as well as resource use and costs in the outcome period. Miscoding in the database could affect the results, but there is no reason to believe that coding inaccuracies in the data may have affected the sarcoidosis and non-sarcoidosis control groups differently. Similarly, it is unknown the extent to which diagnostic accuracy may have improved throughout the study period, and it’s possible that some patients with undiagnosed sarcoidosis may be in the control group (which would lead to downward bias in our results). In addition, while prior studies have shown potential differences in sarcoidosis disease patterns by race; however, race and ethnicity are not available in the data. Future research could explore differentiation by race to explore the extent to which prior findings bear out in cost patterns. This study was limited to work time lost due to disability or medical treatment measures directly or indirectly observable in the data, and did not incorporate potential additional work time lost due to missed work for other reasons, such as sick time at home or reduced on-the-job productivity (i.e. “presenteeism”). Further, because work loss information could only be estimated for a sub-set of primary beneficiaries, the calculation by definition is limited to the employed population only. With respect to propensity score matching, costs in the baseline period were used in the propensity score and, consequently, pairs had similar baseline period costs. This was done to attribute differences in costs in the outcome period to the sarcoidosis diagnosis; however, to the extent that some sarcoidosis-related costs precede this initial diagnosis, the approach used in and results of this study will understate the true cost differences. Finally, the study was based on a population of commercially-insured beneficiaries in the US, and may not be generalizable to other populations.

Conclusions

This study used rigorous methodologies to estimate incremental and overall burden of newly-diagnosed sarcoidosis using administrative claims data, controlling for a broad set of underlying differences between sarcoidosis and control patients. As a result, the findings of this study help shed light on the substantial economic burden of sarcoidosis by quantifying the incremental healthcare resource use and costs associated with treating these patients, as well as the increase in rates of disability and medically-related absenteeism, which burdens both patients and employers.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Hampton, NJ.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

WWN, MP, and GJW are employees of Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, which provided research funding to Analysis Group, Inc. (employer of JBR, AW, AL, AC, AW). Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

An abstract containing results from this analysis was presented at the 2nd International Conference on Respiratory and Pulmonary Medicine on October 17–19, 2016 in Skokie, IL.

Acknowledgments

No assistance in the preparation of this article is to be declared.

References

- Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoid Vascul Diffuse Lung Dis Offic J WASOG 1999;16:149-73

- Baughman RP, Drent M, Kavuru M, et al. Infliximab therapy in patients with chronic sarcoidosis and pulmonary involvement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:795-802

- Baughman RP, Lower EE, Gibson K. Pulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis. Presse Med 2012;41:e289-302

- Judson MA, Thompson BW, Rabin DL, et al. The diagnostic pathway to sarcoidosis. Chest 2003;123:406-12

- Shorr AF, Helman DL, Davies DB, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in advanced sarcoidosis: epidemiology and clinical characteristics. Eur Resp J 2005;25:783-8

- Reich JM, Johnson RE. Incidence of clinically identified sarcoidosis in a northwest United States population. Sarcoid Vascul Diffuse Lung Dis Offic J WASOG 1996;13:173-7

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit care Med 2001;164:1885-9

- Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, et al. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis: environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:1324-30

- American Lung Association. Lung health & diseases: Diagnosing and treating sarcoidosis. American Lung Association 2017. http://www.lung.org/lung-health-and-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/sarcoidosis/diagnosing-and-treating-sarcoidosis.html. Accessed February 5, 2017

- Chen ES, Moller DR. Sarcoidosis—scientific progress and clinical challenges. Nature Rev Rheumatol 2011;7:457-67

- Vardhanabhuti V, Venkatanarasimha N, Bhatnagar G, et al. Extra-pulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis. Clin Radiol 2012;67:263-76

- Papadia M, Herbort CP, Mochizuki M. Diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis. Ocular Immunol Inflam 2010;18:432-41

- Holmes J, Lazarus A. Sarcoidosis: extrathoracic manifestations. Disease-a-month: DM 2009;55:675-92

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130-9

- Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46:399-424

- Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:480-8

- Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, et al. The comparative safety of opioids for nonmalignant pain in older adults. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1979-86

- Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, et al. The comparative safety of analgesics in older adults with arthritis. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1968-76

- Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, et al. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA 2010;303:2359-67

- Bradford Rice J, White A, Lopez A, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and work loss in dermatomyositis and polymyositis patients in a privately-insured US population. J Med Econ 2016;19:649-54

- Bradford Rice J, Cummings AK, Birnbaum HG, et al. Burden of diabetic foot ulcers for medicare and private insurers. Diabetes Care 2014;37:651-8

- US Census Bureau, Population Division. Annual estimates of the resident population by single year of age and sex for the United States: 1 April 2010 to 1 July 2014, released June 2015. http://factfinder2.census.gov/. Accessed May 24, 2016

- Ward BW, Clarke TC, Freema G, et al. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the 2014 National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics 2016. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_11042016.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2017

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Employement Situation—October 2016. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2016. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_11042016.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2017

- Birnbaum ADFD, Mirsaeidi M, Wehrli S. Sarcoidosis in the national veteran population: Association of ocular inflammation and mortality. Opthalmology 2015;122:934-8

- Erdal BS CB, Yildiz VO, Julian MW, et al. Unexpectedly high prevalence of sarcoidosis in a representative U.S. Metropolitan population. Respir Med 2012;106:893-9

- Baughman RP, Field S, Costabel U, et al. Sarcoidosis in America. Analysis based on health care use. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13:1244-52