Abstract

Background: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is an orphan disease that primarily affects the elderly. The majority of symptomatic patients eligible for frontline treatment are unfit for fludarabine based chemoimmunotherapy. Historical treatment includes chlorambucil (Chl), bendamustine/rituximab (BR), and chlorambucil/rituximab/ChlR combination. Clinical guidelines now recommend the use of novel agents, such as ibrutinib (Ibr), in both frontline and relapse settings and other novel agents, such as idelalisib (with rituximab), in relapse settings. Despite compelling clinical results for novel agents, follow-up in clinical trials is relatively short and, thus, the comparative long-term benefits are still unknown.

Materials and methods: The authors developed a simulation model to generate treatment specific lifetime estimates of Overall Survival (OS) and Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) for treatment with BR, Chl, ChlR, and Ibr. Two potential clinical scenarios were modelled: with and without novel agents for treating CLL. The model was based on health states relating to first- and second-line progression-free survival (PFS), post-progression survival, and death.

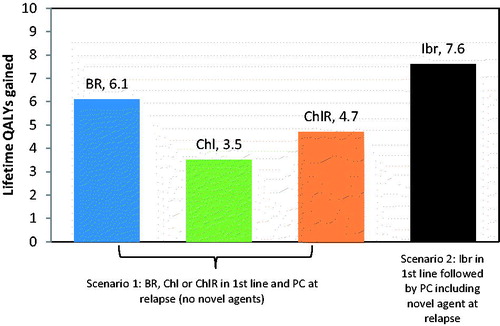

Results: Where novel agents were assumed unavailable, mean OS ranged from 5.4–8.5 years and QALYs from 3.5–6.1. Where novel agents were available, the mean OS increased to 10.0 years, with a corresponding increase in QALYs to 7.6. Frontline Ibr use followed by Physician’s Choice, including novel agents at relapse, resulted in projected increase in OS of between 18% (1.5 years) and 85% (4.6 years), corresponding to a 25–117% increase in QALYs, compared with currently available traditional therapies.

Limitations: The limitations of this analysis include immature OS data and the assumption of equivalent efficacy across all novel agents in terms of their impact on PFS and OS.

Conclusions: The use of novel agents is predicted to yield substantive gains in predicted lifetime OS and QALY improvements compared to traditional therapies in CLL patients who are ineligible for fludarabine-based chemoimmunotherapy.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is an incurable hematological malignancy that accounts for approximately one-third of adult leukemia diagnoses and is the most common leukemia in Western countries. It has an annual incidence of ∼4.2/100,000 adultsCitation1, and a prevalence of ∼4.3/10,000Citation2, meaning it is classified as a rare diseaseCitation3. It is primarily a disease of the elderly, having a median age at diagnosis of 72 yearsCitation1. Almost 70% of newly diagnosed patients are aged 65 years or overCitation4.

Diagnosis is often made after blood tests performed for unrelated reasons, and up to half of the patients are asymptomatic at initial diagnosisCitation5. Where symptoms are present, the burden on patients can be considerable. Symptoms can include fatigue, anemia, thrombocytopenia, night sweats, and feversCitation5. In patients whose disease is not controlled, recurrent infections due to CLL’s effect on the immune system are a major cause of morbidity and mortality, and infection-related hospitalizations are commonCitation6. These patients may require regular blood transfusions to treat cytopenias. While treatment eliminates or reduces cytopenias and symptomsCitation7, the adverse effects of treatment can add to the burden on patients and contribute towards reduced health-related quality-of-lifeCitation8.

Clinical guidelines do not recommend treatment for patients with asymptomatic CLLCitation1,Citation7,Citation9. The standard first-line treatment for physically fit patients (<70 years of age and no major comorbidity) is chemo-immunotherapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR); bendamustine + rituximab (BR) may also be used. For older/less fit patients, guideline-recommended treatments include ibrutinib; obinutuzumab, ofatumumab, or rituximab, in combination with chlorambucil; BR; FR; and single-agent chlorambucil or rituximab1.9. Idelalisib is also approved for first-line treatment in the presence of 17p deletion or TP53 mutation in patients who are not eligible for any other therapiesCitation10. There is no single standard of care for treatment at relapse; options include, but are not limited to, novel agents (including ibrutinib and idelalisib, in combination with rituximab), BR, reduced-dose FCR, high-dose steroids, and rituximabCitation9. Patients typically receive multiple lines of therapy over the course of their disease, each characterized by a progression-free period followed by relapse.

The choice of first line treatment is based primarily on fitness to undergo intensive chemo-immunotherapy (CIT; based on age and comorbidity status)1.9. In addition, patients with the del(17p) abnormality or TP53 mutation have poor response to CIT and are generally treated with other agents such as ibrutinib, idelalisib + rituximab, or venetoclaxCitation1,Citation11. Approximately half of CLL patients aged >65 years are estimated to have at least one major comorbidityCitation12,Citation13. In a 2015 analysis of a CLL population in Europe (including data from Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the UK), 34% of patients newly diagnosed with CLL were eligible for treatment. Of these, only 33% were eligible for intensive CIT. Sixty percent were unsuitable for CIT due to age or fitness, and 7% were unsuitable on the grounds of cytogenetic statusCitation14. Thus, the majority of previously untreated CLL patients are ineligible for CIT. The goal of therapy in this group is a balance between efficacy and toxicity, allowing control of the disease and prolongation of progression-free and overall survival without unacceptable detriment to quality-of-lifeCitation12. Various novel agents have been developed in response to this previously unmet need. Because of their more selective mode of action, novel agents generally have fewer systemic side-effects than cytotoxic chemotherapies. In this paper, we use the term “novel agents” to refer to any agents other than cytotoxic chemotherapy agents.

As follow-up in clinical trials of novel agents in first-line therapy of CLL is limited, the long-term benefit these novel agents provide to patients is unknown. We review the impact of CLL on HRQoL (as measured by preference-based utility scores) and use modeling techniques to explore the long-term impact of treatment with novel agents compared with chemotherapy-based regimens in terms of progression-free and overall survival and HRQoL.

Methods

Literature review

A systematic literature review was carried out to identify interventional and observational studies, health technology assessments, and economic evaluations that reported HRQoL data related to first-line treatment of CLL with any chemotherapeutic, biologic, or investigational pharmaceutical agents. The outcomes of interest reported here were value or change in value of scores from preference-based HRQoL measures, from which 0–1 utility scores can be derived, and also studies eliciting utility scores from patients with CLL or the general public. Searches were conducted on February 11, 2016 in MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, the NHS EED, EconLit, and DARE, with no temporal or language limits. Recently conducted systematic reviews and conference abstracts for the last 2 years of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), American Society of Hematology (ASH), European Society of Haematology (EHA), European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), and International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) conferences were also searched.

Analysis of EQ-5D data from the RESONATE-2 trial

In the RESONATE-2 trial, EQ-5D-5L data were collected from the ITT population at baseline, every 4 weeks until week 48, and every 8 weeks thereafter, or until progression or study closureCitation15. These data were used to inform a repeated measures mixed effect model (RRME) in order to estimate the effects of treatment, responder status, and grade III/IV adverse events (AEs) on changes in utility over time. The impact of the following variables was included in the RRME model: age, gender, Rai stage at randomization, del11q status at randomization, and grade III/IV AEs. Baseline utility score was included in all regression models.

Modeling of patient-relevant benefits with novel agents

Overview

An economic model was developed in Microsoft Excel to generate treatment-specific lifetime undiscounted estimates of progression-free survival (PFS), post-progression survival (PPS), Overall Survival (OS), and Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) for treatment with bendamustine + rituximab (BR), chlorambucil (Chl), chlorambucil + rituximab (ChlR), and the novel agent ibrutinib (Ibr). The population modeled was patients with untreated CLL and ineligible for full-dose CIT.

Two scenarios were generated, representing worlds without and with the use of selected novel agents for treating CLL. In scenario 1, novel agents are not used, either in first line or at relapse. Patients can receive any first-line therapy except a novel agent, and physician’s choice (PC) from a range of therapies as their next treatment (i.e. in the relapsed/refractory setting). In scenario 2, novel agents are used in first line and at relapse; patients were assumed to receive ibrutinib in first line, and subsequently to receive PC from a range of therapies, including 30% idelalisib + rituximab (IR).

The assumed composition of treatment in the analysis population is shown in . The composition of PC in scenario 1 included 35% BR, based on expert opinion and IMS Oncology analyser data from five countries (UK, Spain, France, Italy, and Germany) (unpublished, Janssen data); the other percentages were assumed to be evenly distributed across the other regimens. For the scenario with use of novel agents, assumptions of 35% BR and 30% IR were made, reflecting uptake of these agents in various markets; usage of R and FCR-Lite was consequently reduced by 15% each.

Table 1. Composition of physician’s choice in the RR setting in each scenario.

Model structure

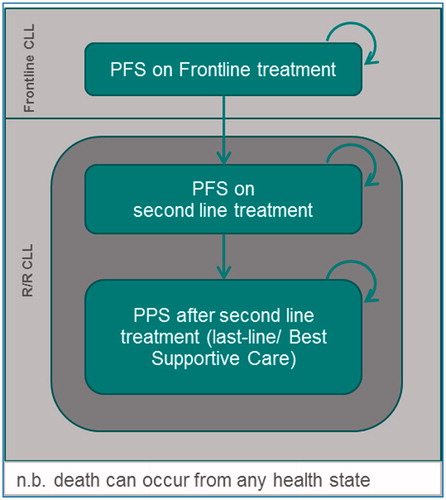

The model used the Markov health state transition approach and was based on health states relating to initial PFS, second-line PFS, PPS, and death (). A treatment sequence approach was used whereby OS was estimated by summing the mortality during frontline PFS, mortality during second-line PFS, and mortality during last-line/best supportive care.

Clinical efficacy parameters

PFS data on which first-line and relapsed/refractory therapy was based came from the RESONATECitation16 and RESONATE-2Citation15 trials, and mortality during first-line PFS and during second-line PFS and post-progression survival (PPS) was also based on information from these studies. In all cases, the trial data were used to inform the fitting of parametric functions which were used to extrapolate beyond data availability.

The primary data sources for comparative efficacy in frontline were obtained from a meta-analysisCitation17 where five RCTs met the pre-defined inclusion criteria; the key characteristics of the population were comparable to the treatment naïve patients in RESONATE-2. The hazard ratios (HRs) obtained from the network meta-analysis (NMA) were used to estimate comparison against other frontline treatments. Similarly, the relative efficacy of ibrutinib against other agents in the R/R setting was estimated using two indirect treatment comparisonsCitation18. One compared ibrutinib (in RESONATE) to PC (using data from Osterborg et al.Citation19 comparing PC to ofatumumab (O) in treatment of R/R CLL). The second compared ibrutinib to idelalisib + O (a proxy for idelalisib + rituxumab) using data from Jones et al.Citation20. HRs derived from the indirect treatment comparisons were applied to the ibrutinib curves from RESONATE to estimate outcomes for comparators.

Additional model parameters

Incidence rates of grade III/IV treatment related adverse events (TRAEs) were taken from published sources (). Where no information was reported in the underlying publication, a value of 0% was used in the economic model. Utility values for TRAEs (), post-progression, and subsequent lines of therapy () were taken either from a recent UK reimbursement submissionCitation21 or the literature.

Table 2. Parameter values related to grade III and IV adverse events.

Table 3. Additional utility parameters.

Results

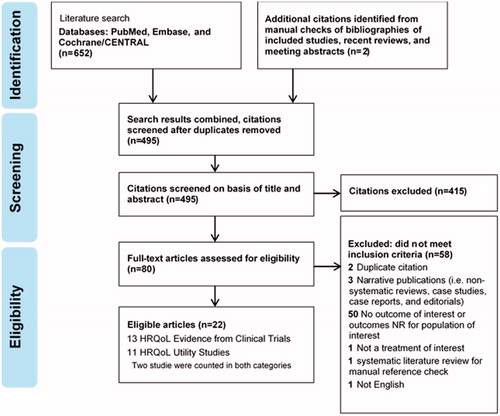

Literature review of HRQoL

Eleven publications () were identified that reported either preference-based utility values or overall index scores for the EQ-5D instrument in first-line therapy; some also identified values for other therapy lines. None of the clinical trial publications identified reported utility values. All the utility values identified were from observational studies of CLL patients, utility-elicitation studies with the general public, or health technology assessments or economic evaluations. Where the paper reported utilities from a secondary source (three of 11 publications), that source was included. summarizes the eight publications that report original utility data.

Table 4. Summary of identified studies reporting original utility information.

The studies measured or estimated utilities for a diverse range of scenarios, making comparisons difficult. Holtzer-Goor et al.Citation8 reported utility values for CLL patients in the Netherlands who were either on active treatment, not on treatment, or in a “watch and wait” period. They noted that the HRQoL impact of CLL in the “watch and wait” phase was limited, but found a considerable detriment to HRQoL (as measured by disease-specific instruments) when treatment began. This was the case for all treatments including chlorambucil, which is normally regarded as a more tolerable treatment. Overall, their sample of patients had utility close to that of the Dutch population norm, with a modest decline for patients on active treatment.

Both Kosmas et al.Citation22 and Beusterien et al.Citation23 also found little impact on utility for scenarios based on absence of CLL symptoms resulting from response to therapy. Kosmas et al.Citation22 used CLL-related health states developed using the literature and patient and clinician interviews, and evaluated preferences for these using the time trade-off method with 100 members of the public in the UK. Utility was estimated at 0.82 in a state of PFS without therapy, but fell markedly on-therapy (particularly intravenous therapy) and for health states describing successive progressions and therapy lines. They concluded that the values obtained underline the value of maintaining PFS for as long as possible in CLL, and highlight the extent to which HRQoL declines following first line progression. Beusterien et al.Citation23 found a similar pattern of reduction in utility for progressive disease and subsequent lines of treatment.

In a registry-based study of CLL patients in the US, Kay et al.Citation24 found a small but statistically significant decline in EQ-5D scores before each successive line of therapy compared with earlier therapies, and this was supported by the disease-specific and fatigue-specific instruments they reported.

Utilities derived from the COMPLEMENT-1 trial of ofatumumab + chlorambucil vs chlorambucil alone, as reported by Herring et al.Citation25 found little difference in average utility scores between response states.

Patient-relevant benefit with novel agents

EQ-5D analysis from the RESONATE-2 trial

Baseline utility was not significantly different between the two treatment arms. The overall baseline utility for CLL patients receiving frontline treatment was calculated as 0.78 (SE = 0.020) using the weighted average of the two arms. After accounting for the impact of all covariables of interest, a statistically significant increase in utility of 0.036 (SE = 0.016; p = .02) associated with Ibr treatment compared with baseline treatment (Chl). A statistically significant disutility of −0.051 (SE = 0.008, p < .0001) associated with grade III/IV adverse events from any treatment was also identified. There was no utility increment associated with response.

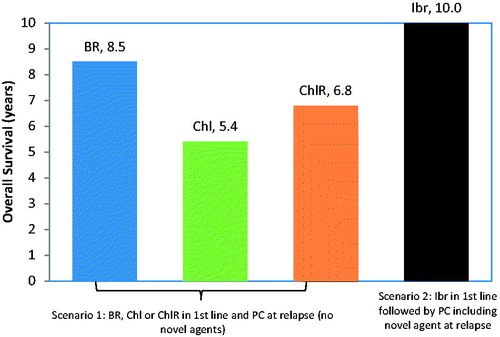

Modeling of long-term patient benefit

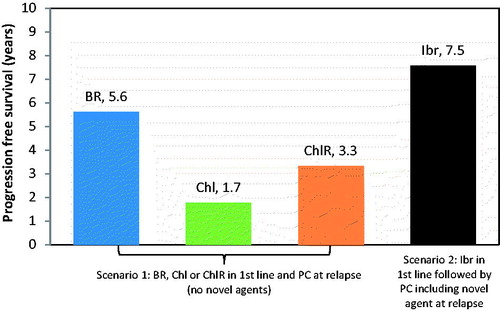

Results for a range of frontline treatment options including clinical scenarios with and without novel agents in front line and in relapse are presented in and . Mean OS where novel agents were not used ranged from 5.4–8.5 years and QALY from 3.5–6.1. Mean OS with novel agents (Ibr in first line followed by PC) was 10.0 years, corresponding to 7.6 QALYs. Ibr use in first line followed by PC including a novel agent at relapse resulted in a projected increase in OS of between 18% (1.5 years) and 85% (4.6 years) compared with traditional therapies.

Figure 3. Predicted overall survival estimates for each frontline therapy of interest (second line therapy, as in ).

Figure 4. Predicted QALY estimates for each frontline therapy of interest (second line therapy, as in ).

The corresponding length of time in the PFS health state, rather than alive (i.e. in either PFS or PPS) is presented in . Mean PFS ranged from 1.7–5.6 years. Ibr usage increased time in the progression-free state by between 34% (1.96 years) and 341% (5.8 years), compared to conventional therapies.

Discussion

Given the chronic nature of CLL, long-term data on the impact of treatment on HRQoL are important in order to understand the overall impact of treatment on patients’ wellbeingCitation26. One way to assess the overall benefit to patients from treatment is the QALY, which combines the concepts of survival and HRQoL (as expressed using generic preference-based measures such as EQ-5D). Overall, the available data from preference-based measures of HRQoL identified in our literature review suggest that patients who experience no or minimal CLL symptoms, either before they require active treatment or whilst they are in a state of response to initial treatment, have only a minor detriment to utility compared with population norms. Once patients experience disease progression and move to subsequent lines of therapy, the impact on their utility becomes more markedCitation22,Citation23. Thus, first-line treatments that offer prolonged progression-free survival and a minimal side-effect burden could be expected to delay the onset of the lower-utility states associated with successive disease progressions. Common reasons for initiating first line treatment of CLL include bone marrow failure manifested by development of, worsening of anemia and/or thrombocytopenia, disease burden, and disease symptomsCitation27. Thus, a rapid and long-lasting response to first line treatment is also important from a HRQoL perspective.

Novel agents have been developed as alternative treatments for the large proportion of patients who are not eligible for chemoimmunotherapy. Analysis of the EQ-5D data from the RESONATE-2 study of ibrutinib vs chlorambucil, presented in this paper, found that baseline utility for patients beginning first line treatment was 0.78, consistent with that reported in the COMPLEMENT-1 trial of ofatumumab + chlorambucil, and similar to that reported by Holtzer-Goor et al.Citation8.

The most common reasons for initiating front-line treatment included marrow failure, disease burden, and disease symptoms, all of which improved in patients treated with ibrutinibCitation27. Treatment with ibrutinib was associated with a statistically significant gain in utility, whereas chlorambucil treatment was associated with a decrease in utility. Response to treatment (regardless of agent) was not in itself associated with a change in utility. However, although it is required for economic modeling, EQ-5D-5L may not be sensitive enough to capture the full range of changes in HRQoL, especially in people with cancerCitation28. For example, fatigue is a common treatment-related AE in CLL. In RESONATE-2, treatment with ibrutinib was associated with a statistically significant improvement in fatigue from baseline, as measured by the FACIT-Fatigue instrument, whereas chlorambucil was associated with increased fatigue (p = .0004 for difference between treatments)Citation27,Citation29. However, the EQ-5D is not structured to capture the impact of fatigue on patients’ utility. The finding of a utility gain with ibrutinib is backed up by the fact that, in RESONATE-2, ibrutinib was associated with a greater improvement than chlorambucil in the EORTC QLQC-30 global score (p = .0002), a cancer-specific patient-reported measure of HRQoLCitation27.

Our modeling indicates that, in an elderly and unfit patient with CLL, with a relatively short life expectancy (46–64 months)Citation30, the use of novel agents such as ibrutinib appears to yield substantive predicted increases in lifetime patient-related benefits compared to traditional therapies. The main driver of patient-centered benefit, as measured by gain in QALYs, was time spent in progression-free survival with first line treatment. Entry to the progressed state and to further lines of therapy is generally associated with declining utilityCitation22,Citation23,Citation31. Thus, treatments that are associated with both prolonged PFS and on-treatment improvements in HRQoL are likely to confer the greatest benefits from the perspective of patients with CLL.

As with all studies that look to use statistical techniques to extrapolate clinical trial data over a long-term period, there are a number of limitations to the work presented in this paper. Primarily, the OS data arising from the RESONATE trial program is immature, and this meant that we were not able to directly extrapolate the observed information, but had to generate estimates of overall survival based on available data in each of the composite health states (Frontline PFS, second line PFS, post-progression). The validity, and accuracy, of these survival predictions will only become apparent over time, as real world data emerges against which they can be compared.

An assumption of equivalence of efficacy of all novel agents in terms of impact on PFS and OS was also made in order to view ibrutinib as indicative of all such therapies, for the purpose of interpreting our results. While this assumption might be challenged, it is important to note that the purpose of this study was to attempt to quantify the magnitude of patient-centered benefit of using novel agents generally. As such, while the absolute values generated by the simulation model may change if different efficacy were used, the general conclusion would not; use of novel agents offers substantive patient-centered benefits compared to standard therapies.

Partial validation of this assumption can be taken from a published microsimulation model that simulated the dynamics of the CLL patient population under given management strategies (CIT as standard of care before 2014 and novel agents for untreated patients with or without genetic mutation and relapsed CLL from 2014) in the US from 2011–2025Citation32. This study documented population level outputs, but it is possible to derive per-patient estimates from the reported information (2.85 incremental QALYs gained for novel agents vs CIT). This value is similar to those generated from our analysis and, thus, strengthens the conclusion that using novel agents leads to substantive patient-centered benefits.

Similarly, patient level EQ-5D data was available to the authors of this paper from one novel agent—ibrutinib—and so the assumption of equivalence of impact of ibrutinib on HRQoL with other novel agents was necessary. Given the exploratory nature of the work in this paper, this assumption again is unlikely to have had a substantive impact on the overarching conclusions of the work. The utility increment for ibrutinib had only a small impact on the results of the analysis, so we would not expect much variation to the results and conclusions if different utility increments had been assigned to other novel agents. It is worth noting that the results from the analysis of RESONATE-2 trial data are broadly in line with those reported in studies identified by the systematic literature review.

Overall, our modeling results suggest that novel agents such as ibrutinib are likely to provide patients with a substantive benefit when used in treatment-naïve patients who are not eligible for fludarabine-based therapy, compared with the use of currently available chemotherapy-based therapies such as bendamustine- and chlorambucil-based regimens.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The study was funded by Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MS and SM are employees of ICON. JW worked as a paid contractor for ICON. SB and SC are employees of Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

No assistance in the preparation of this article is to be declared.

References

- Eichhorst B, Robak T, Montserrat E, et al. e-update 2016, refers to Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2016;26(Suppl5):v78-84

- SEER. SEER. Prevalence database: “US Estimated 37-year L-D prevalence counts on 1/1/2012”. National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Data Modeling Branch, released April 2015, based on the November 2014 SEER data submission. 2012. http://surveillance.cancer.gov/prevalence/canques.html. [Last ccessed 8 February 2016]

- European Medicines Agency. Medicines for rare diseases. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/special_topics/general/general_content_000034.jsp. [Last accessed August 2016]

- Gribben JG. How I treat CLL up front. Blood 2010;115:187-97

- Mir MA. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Medscape Drugs and Diseases [Internet]; 2016. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/199313-overview

- Perkins JG, Flynn JM, Howard RS, et al. Frequency and type of serious infections in fludarabine-refractory B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma: implications for clinical trials in this patient population. Cancer 2002;94:2033-9

- Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute–Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood 2008;111:5446-56

- Holtzer-Goor KM, Schaafsma MR, Joosten P, et al. Quality of life of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in the Netherlands: results of a longitudinal multicentre study. Qual Life Res 2015;24:2895-906

- National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas, v3.2016; 2016. www.nccn.org

- Gilead Sciences Ltd. Zydelig (idelalisib): Summary of product characteristics; 2016. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/29201. [Last accessed 14 June 2017]

- Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 376:1164-74

- Shanafelt T. Treatment of older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: key questions and current answers. ASH Education Program Book 2013;2013:158-67

- Thurmes P, Call T, Slager S, et al. Comorbid conditions and survival in unselected, newly diagnosed patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymph 2008;49:49-56

- Jeyakumaran D, Kempel A, Cote S. An assessment of the number of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients eligible for front-line treatment but unsuitable for full-dose fludarabine across the European Union. Value Health 19:A574-A5

- Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2425-37

- Byrd JC, Brown JR, O’Brien S, et al. Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2014;371:213-23

- Xu Y, Fahrbach K, Dorman E, et al. A Bayesian network meta-analysis (NMA) of therapies for treatment-naïve chronic lymphocytic leukemia (TN-CLL) patients ineligible for full-dose fludarabine therapy. ISPOR 22nd Annual International Meeting 2017, Boston, MA, USA, May 20-24, 2017

- Sorensen S, Wildgust M, Sengupta N, et al. Indirect treatment comparisons of ibrutinib versus physician’s choice and idelalisib plus ofatumumab in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Ther 2017;39:178-89e5

- Österborg A, Udvardy M, Zaritskey A, et al. Ofatumumab (OFA) vs. physician’s choice (PC) of therapy in patients (pts) with bulky fludarabine refractory (BFR) chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL): results of the phase III study OMB114242. Blood 2014;124:4684

- Jones JJ, Wach M, Robak T, et al. Results of a phase 3 randomized, controlled study evaluating the efficacy and safety of idelalisib (IDELA) in combination with ofatumumab (OFA) for previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). ASCO Annual Meeting. Chicago, IL, USA. 29 May-2 June 2015

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). TA 343: Obinutuzumab in combination with chlorambucil for untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; 25 April 2017. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA343/Evidence

- Kosmas CE, Shingler SL, Samanta K, et al. Health state utilities for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: importance of prolonging progression-free survival. Leuk Lymph 2015;56:1320-6

- Beusterien KM, Davies J, Leach M, et al. Population preference values for treatment outcomes in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a cross-sectional utility study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:50

- Kay NE, Flowers CR, Weiss M, et al. Variation in health-related quality of life by line of therapy of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2015;120:3926

- Herring W, Pearson I, Purser M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ofatumumab plus chlorambucil in first line chronic lymphocytic leukemia in Canada. Value Health 2014;17:A633

- Zent CS. Improving quality of life in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymph 2012;53:1247-8

- Barr PM, Kipps T, Robak T, et al. Improvement in hematologic function, disease burden/symptoms with ibrutinib in older treatment-naïve (TN) patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in phase 3 RESONATE-2. Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Geriatrics Society (AGS); Long Beach, FL, USA. May 2016

- Garau M, Shah KK, Mason AR, et al. Using QALYs in cancer: a review of the methodological limitations. Pharmacoeconomics 2011;29:673-85

- Ghia P, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. Improvement in quality of life and well-being in older patients with treatment-naïve (TN) CLL: Results from the randomized phase 3 study of ibrutinib (IBR) versus chlorambucil (CLB) (RESONATE-2). European Haematology Association Annual Meeting, Copenhagen, Denmark, 10 June 2016

- Eichhorst B, Busch R, Stilgenbauer S, et al. First-line therapy with fludarabine compared with chlorambucil does not result in a major benefit for elderly patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2009;114:3382-91

- Hancock SWB, Hyde C. Fludarabine as first line therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Report 42. Birmingham, UK: Department of Public Health & Epidemiology, University of Birmingham; 2002

- Chen Q, Jain N, Ayer T, et al. Economic burden of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of oral targeted therapies in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:166-74

- Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1101-10

- Tolley K, Goad C, Yi Y, et al. Utility elicitation study in the UK general public for late-stage chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Eur J Health Econ 2013;14:749-59

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Appraisal consultation document: Obinutuzumab in combination with chlorambucil for untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. NICE; London, UK. 2014

- Shingler SL, Kosmas CE, Samanta K, et al. Health state utilities for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Value Health 2014;17:A92

- Woods B, Hawkins N, Dunlop W, et al. Bendamustine versus chlorambucil for the first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in England and Wales: a cost-utility analysis. Value Health 2012;15:759-70

- Knauf WU, Lissichkov T, Aldaoud A, et al. Phase III randomized study of bendamustine compared with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol Offic J Am Soc Clin Oncol 2009;27:4378-84

- Hillmen P, Robak T, Janssens A, et al. Chlorambucil plus ofatumumab versus chlorambucil alone in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (COMPLEMENT 1): a randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet 2015;385:1873-83

- Holzner B, Kemmler G, Sperner-Unterweger B, et al. Quality of life measurement in oncology-a matter of the assessment instrument? Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:2349-56