Abstract

Aims: Guidelines recommend prophylaxis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for chemotherapy-induced (febrile) neutropenia (CIN/FN) based on regimen myelotoxicity and patient-related risk factors. The aim was to conduct a cost-efficiency analysis for the US of the direct acquisition and administration costs of the recently approved biosimilar filgrastim-sndz (Zarxio EP2006) with reference to filgrastim (Neupogen), pegfilgrastim (Neulasta), and a pegfilgrastim injection device (Neulasta Onpro; hereafter pegfilgrastim-injector) for CIN/FN prophylaxis.

Methods: A cost-efficiency analysis of the prophylaxis of one patient during one chemotherapy cycle under 1–14 days’ time horizon was conducted using the unit dose average selling price (ASP) and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for subcutaneous prophylactic injection under four scenarios: cost of medication only (COSTMED), patient self-administration (SELFADMIN), healthcare provider (HCP) initiating administration followed by self-administration (HCPSTART), and HCP providing full administration (HCPALL). Two case studies were created to illustrate real-world clinical implications. The analyses were replicated using wholesale acquisition cost (WAC).

Results: Using ASP + CPT, cost savings achieved with filgrastim-sndz relative to reference filgrastim ranged from $65 (1 day) to $916 (14 days) across all scenarios. Relative to pegfilgrastim, savings with filgrastim-sndz ranged from $834 (14 days) up to $3,666 (1 day) under the COSTMED, SELFADMIN, and HPOSTART scenarios; and from $284 (14 days) up to $3,666 (1 day) under the HPOALL scenario. Similar to the cost-savings compared to pegfilgrastim, filgrastim-sndz achieved savings relative to pegfilgrastim-injector: from $834 (14 days) to $3,666 (1 day) under the COSTMED scenario, from $859 (14 days) to $3,692 (1 day) under SELFADMIN, from $817 (14 days) to $3,649 (1 day) under HPOSTART, and from $267 (14 days) to $3,649 (1 day) under HPOALL. Cost savings of filgrastim-sndz using WAC + CPT were even greater under all scenarios.

Conclusions: Prophylaxis with filgrastim-sndz, a biosimilar filgrastim, was associated consistently with significant cost-savings over prophylaxis with reference filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, and pegfilgrastim-injector, and this across various administration scenarios.

Introduction

Depending on the myelotoxicity of a given regimen, cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy may be at significant risk of developing chemotherapy-induced (febrile) neutropenia (CIN/FN), a potentially life-threatening complicationCitation1–5. Febrile neutropenia can often lead to ambulatory and emergency room visits and, in severe cases, hospitalizationCitation5. Consequently, the chemotherapy regimen may be switched to a less myelotoxic one or subsequent cycles of chemotherapy may be reduced in dose, delayed, or discontinued, which reduces the relative dose intensity (RDI) of the chemotherapy treatmentCitation6. In turn, this may interfere with tumor response to treatment and impair clinical outcomesCitation6,Citation7. The impact of (febrile) neutropenia on quality-of-life is significant because of anxiety, depression, symptom burden, and impairment in functional status and activityCitation8,Citation9.

Recombinant granulocyte-colony stimulating factors (GCSF) such as filgrastim (Neupogen, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) and its pegylated formulation pegfilgrastim (Neulasta, Amgen) are biological growth factors that promote the production of neutrophils in the bone marrowCitation10. The product label advises that filgrastim be administered daily for a maximum of 14 days, starting no sooner than 24 h following the end of myelosuppressive chemotherapyCitation11. Pegfilgrastim includes a single subcutaneous injection per chemotherapy cycle, also administered no sooner than 24 h after chemotherapyCitation12. International best practice guidelines for CIN/FN prophylaxis recommend GCSF initiation with filgrastim or pegfilgrastim no sooner than 24 h, but also no later than 3Citation13 or 4 daysCitation14 following the completion of a chemotherapy infusion. Recently, an on-body injector device (Neulasta Onpro, Amgen) was approved, which is applied the day of chemotherapy to administer pegfilgrastim ∼27 h laterCitation12. Following the patent expirations for reference filgrastim, the biosimilar agent filgrastim-sndz was approved in Europe in 2008 and in the US in 2015. It has since been marketed in Europe as Zarzio and in the US as Zarxio.

A meta-analysis of 17 randomized controlled trials showed convincingly that, as a class, GCSFs reduce the risk of febrile neutropenia, infection-related mortality, and all-cause mortality; and improve the RDI of the chemotherapy regimens compared to placebo or untreated controlsCitation3. In contrast, there has been debate as to the potential superiority of pegfilgrastim over reference filgrastim, as pegfilgrastim was approved on the basis of two non-inferiority trials comparing it to the reference filgrastimCitation15,Citation16. A pooled analysis of these two pivotal trials suggested potential superiorityCitation17; however, each of the individual trials was adequately powered to begin with. Three meta-analyses attempted to document the relative superiority of pegfilgrastim over filgrastimCitation18–20. However, they are methodologically compromised by the limited number of studies includedCitation21, the inordinate weight of one study suggesting superiority when other adequately powered studies indicate no differential efficacy between both agents, and selectivity in the end-points included. One publication reported on analyses of four serially introduced regimens of CIN/FN prophylaxis in four sequential non-randomized cohorts of breast cancer patients: ciproflaxin, daily filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, and pegfilgrastim in combination with ciproflaxin. Pegfilgrastim with or without ciproflaxin was found to be more effective; even though a filgrastim regimen was not compared to pegfilgrastim contemporaneously and under randomized conditions (and neither was any other combination of the four treatments)Citation22. As Klastersky and AwadaCitation21 point out, pegfilgrastim “is definitely not inferior to classical” filgrastim, but “whether it might be more superior and more cost-effective cannot be derived from the presently available data, but it seems unlikely that major differences do exist” (p. 21).

This is important from the vantage point of comparative economic evaluations of GCSFs, especially now that a biosimilar version of filgrastim is available in the US, and biosimilars are reimbursed under Medicare Part B, are allowed as a formulary enhancement in Part D prescription drug plans, and are allowed under the Medicaid Drug Treatment Program. Assuming that filgrastim (including the approved biosimilars) and pegfilgrastim can be considered similar in efficacy based on randomized controlled trials and related pivotal approval studies, the choice of agent may be driven by the economic efficiencies achieved (specifically the reductions in the cost of prophylaxis) rather than the clinical benefits of superior efficacy.

Aapro et al.Citation23 performed a comparative cost-efficiency analysis of filgrastim, filgrastim-sndz, and pegfilgrastim for the five largest countries (G5) in the European Union (Germany, France, the UK, Italy, and Spain [EU]). Evaluating only the cost of medication for one cycle of chemotherapy, they estimated the cost-efficiency achieved through prophylaxis with filgrastim-sndz instead of filgrastim in regimens from 1–14 days; and prophylaxis with 1–14 day regimens of filgrastim or filgrastim-sndz instead of single-administration pegfilgrastim. While pegfilgrastim was found to turn cost-saving at 12 days of prophylaxis with filgrastim, at no point over the 14-day period did pegfilgrastim yield a savings benefit over filgrastim-sndz.

With the entry of filgrastim-sndz onto the US market, we aimed to replicate and extend the Aapro et al.Citation23 European analysis with cost-efficiency analyses specific to the US. Instead of comparing only to pegfilgrastim injections, we also included a pegfilgrastim-injector. In addition to a base-case scenario that evaluates only the cost of medication, we introduce three additional scenarios that vary in the role of the patient and provider in the administration of filgrastim-sndz, reference filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, and the application of pegfilgrastim-injector. We complement primary cost-efficiency analyses based on the Average Selling Price (ASP), with secondary analyses based on the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC). To translate the implications of these analyses to the clinic, we illustrate the economic results with two hypothetical case studies in the oncological (solid tumor) and hematological setting. The intent of our analyses was to assess the affordability of GCSF prophylaxis with filgrastim-sndz vs prophylaxis with reference filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, and pegfilgrastim-injector because of the cost-efficiencies enabled by prophylaxis with filgrastim-sndzCitation24.

Methods

Scenarios

We defined four cost scenarios, as shown in , including a base-case medication cost scenario and three clinical scenarios that, given demographic, geographic, and financial factors influencing access to and utilization of cancer services, are representative of cancer care in the US. The base-case COSTMED scenario considers only the cost of medication and, in the case of the pegfilgrastim-injector, the body injector device. The SELFADMIN scenario assumes that patients self-administer their GCSF injections, whether daily filgrastim or single-dose pegfilgrastim, initiating prophylaxis within the recommended time window following the end of chemotherapy. However, in this scenario, for patients receiving prophylaxis with pegfilgrastim-injector, the application of the device is assumed to be done by staff in clinics and infusion centers at the healthcare provider organization (HPO) in a session on the day of completion of the chemotherapy cycle. In the HPOSTART scenario, prophylaxis is initiated in a single session at the HPO, whether the first injection of filgrastim-sndz or reference filgrastim, the only injection of pegfilgrastim, or the application of the pegfilgrastim-injector device. Lastly, the HPOALL scenario assumes that all GCSF administrations are done at the HPO: injection of pegfilgrastim or application of the pegfilgrastim-injector device in a single session, and filgrastim injections in daily sessions up to the number of days of prophylaxis prescribed (possible range: 1–14 days).

Table 1. Scenarios and associated cost inputs.

Cost model

Following Aapro et al.Citation23, our cost-efficiency analyses focused on the direct costs a buyer or payer would incur when purchasing or covering prophylaxis with any of the four agents (filgrastim-sndz, reference filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, pegfilgrastim-injector) in one patient during one chemotherapy cycle. Indirect costs were not included. Thus, our model included the cost to the buyer or payer of the acquisition and, depending on the scenario, the administration of filgrastim-sndz 300 μg or reference filgrastim 300 μg from 1–14 days, and pegfilgrastim 6 mg as a single-injection or as a single-administration through the pegfilgrastim-injector on-body injector. Filgrastim is also available in 480 μg for patients weighing 65 kg or more or as per institutional preferences; however, the 300 μg dose was the unit of reference in the Aapro et al.Citation23 cost-efficiency analysis and in a US cost-effectiveness studyCitation25.

Assumptions

The following assumptions governed the analyses.

All estimates are expressed in 2016 US dollars (USD) rounded to the nearest integer.

The intention of this analysis was to evaluate the cost-efficiency of prophylaxis with daily (self-) administered subcutaneous injections of filgrastim-sndz for up to 14 days relative to a similar regimen of reference filgrastim, single-injection pegfilgrastim, and pegfilgrastim-injector administered through a single-use on-body injector.

Prophylaxis options were considered to be similar to each other in efficacy, considering the evidence from the pivotal pegfilgrastim vs filgrastim non-inferiority trials. Hence, we estimated the absolute cost of the various prophylaxis regimens and scenarios. We did not adjust cost estimates for differential efficacy, as none was assumed. We excluded expenses related to the management of (febrile) neutropenia, clinician fees, administrative fees, evaluation-and-management fees, and (actual or opportunity) costs of associated reductions, delays, or cancellations of chemotherapy administrations. Our analyses focused on cost-efficiency, not on cost-effectiveness or cost-utility.

Prophylaxis was assumed to be initiated per major European and US guideline recommendationsCitation13,Citation14.

Medication costs were for medications provided through infusion centers or through hospital outpatient services, not through specialty pharmacies. In the primary analysis, the cost estimate of medication was the average selling price (ASP) for the third quarter (October–December) of 2016 (3Q16), as it was derived from the first quarter of 2017 (1Q17) Medicare Part B drug payment limit data published by the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)Citation26. Using the CMS methodologyCitation27, and considering the 6-month time lag before payment limits are calculated, 3Q16 ASP was computed retroactively as the CMS 1Q17 payment limit minus 6%; except for biosimilars, where, per CMS methodology, the ASP is calculated as the payment limit of the biosimilar minus 6% of the ASP of the reference product. The secondary analysis (included as Supplemental Materials) used the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) for the same periodCitation28.

Medication administration costs were defined as the reimbursement received for the applicable 2016 Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codesCitation29. The reimbursement amount is considered to be the true cost.

Reflecting standard clinical practice to teach patients about their medications, patient education costs were assumed to be covered by the cost of medication administration.

Excluded were visit costs, patient co-pays, costs associated with patient self-administration, and other patient costs (travel, lodging, meals and incidentals, time, etc.; and indirect, opportunity, or intangible costs). Discounts and other adjustments in the purchasing or reimbursement process were deemed confidential, variable from provider to providers, and undisclosed. They were not considered in the analyses, nor were any other parameters of the time value of money.

Excluded also were cost drivers that were common to and fixed across all four regimens, as these would not be differentiators of cost outcomes.

No evaluation-and-management (E&M) costs were included because (1) injections/applications may be part of a larger clinic visit and, hence, the applicable E&M-related HCPCS/CPT codes and associated reimbursements would vary, and this independently of prophylaxis; and (2) if E&M could be standardized, it would cease to be a potential cost differentiator.

Cost inputs

presents the ASP medication costs as well as the applicable administration costs for the CPT code 96372 (therapeutic, prophylactic, or diagnostic injection; subcutaneous or intramuscular). The administration costs were $42.31 for reference filgrastim, filgrastim-sndz, and pegfilgrastim as hospital outpatient injections, but $25.44 for a pegfilgrastim-injector, as the device is applied in physician clinics and, therefore, falls under the Physician Fee Schedule; for a difference of $16.87. Note that pegfilgrastim and pegfilgrastim-injector are priced the same. WAC medication costs are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 2. Medication and administration costs (ASP).

Cost-efficiency analyses

For each scenario, and following Aapro et al.Citation23, we calculated the total cost (defined as the required medications plus, as applicable, administration costs) of prophylaxis with each option (filgrastim-sndz, reference filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, pegfilgrastim-injector) per that scenario’s specifications. Total cost of filgrastim-sndz and reference filgrastim prophylaxis were estimated cumulatively from one to 14 daily injections compared to the constant and time-independent cost of pegfilgrastim and pegfilgrastim-injector. From this, we determined the cumulative savings or loss of prophylaxis with filgrastim-sndz over reference filgrastim; and the cost differentials between single-administration pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector prophylaxis vs 1–14 injections with filgrastim-sndz or reference filgrastim. We included the full range from 1–14 days for analytical completeness.

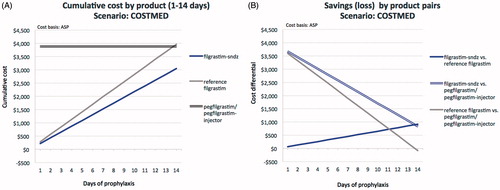

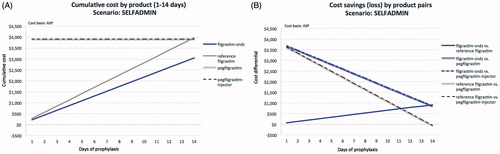

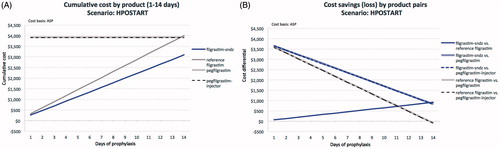

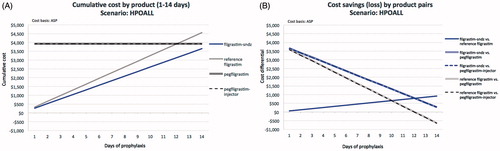

We also generated two graphics for each scenarioCitation23. The first (panel “a” in each figure) plots the cost evolution from 1–14 days of prophylaxis with reference filgrastim or filgrastim-sndz against the constant cost of pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector prophylaxis for the same period. The day at which reference filgrastim or filgrastim-sndz lines intersect with the pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector lines is the point where savings with the standard filgrastim agents cease, and prophylaxis with the pegfilgrastim options become cost-saving. The second graphic (panel “b”) shows the evolution over 14 days in relative savings achieved from filgrastim-sndz vs reference filgrastim prophylaxis. It also displays the evolution in cost-savings when using reference filgrastim or filgrastim-sndz vs pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector. The day at which the line for either daily agent intersects with the zero dollar ($0) line on the y-axis is the point at which using pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector translates into cost-savings. Note that the pegfilgrastim and pegfilgrastim-injector lines virtually overlap because the only cost differential between both is the difference of $16.87 in their respective administration costs.

Case studies

To translate the cost-efficiency results to the clinic, we developed two hypothetical case studies, one in the oncology and one in the hematology setting. Both case studies assume that all GCSF administrations are done by and at the HPO (i.e. HPOALL scenario).

The first case concerns a 43-year-old Caucasian female, newly diagnosed with stage II breast cancer, that is negative for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) and beginning treatment with TAC (docetaxel, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide) for six cycles. The patient has an otherwise unremarkable medical history and no comorbidities. Primary prophylaxis is initiated in cycle 1 due to the high chemotherapy-related risk for neutropenia (>20%), and continued through all six cycles. The local protocol for GCSF support for TAC is either single-injection pegfilgrastim or 11 days of either reference filgrastim or filgrastim-sndz.

The second case involves a 57-year-old African-American male, newly-diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and undergoing treatment with R-CHOP-21 (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, rituximab) for six cycles. The patient has a past history of hypercholesterolemia and hypertension. The patient did not have growth factor added to his treatment regimen, as R-CHOP-21 is at an intermediate neutropenia risk level (10–20%), and the patient lacked other risk factors such as prior history of CIN, anemia, or being 65 years or older. The patient presented to the emergency department with fever and chills 5 days after his second cycle of R-CHOP-21. He had a temperature of 41 °C, heart rate of 120 beats per min, and blood pressure of 80/63. The patient was admitted to the medical oncology service and started on antibiotics, and was an inpatient for 7 days until the fever subsided. Cultures were negative throughout the course of treatment. The patient had pegfilgrastim added to his chemotherapy regimen for the remaining four chemotherapy cycles; however, the insurance company asked to switch the patient to filgrastim-sndz 300 μg, and authorized 7 days of prophylaxis.

Results

Cost-efficiency analyses

and present the results for the primary ASP analyses for, respectively, the COSTMED, SELFADMIN, HPOSTART, and HPOALL scenarios. Each Table details the cumulative variable cost of treatment with filgrastim-sndz or reference filgrastim against the fixed cost of pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector without (COSTMED) and with (other scenarios) the corresponding administration costs, the cumulative cost-savings of using filgrastim-sndz over reference filgrastim, and the cost differential of pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector prophylaxis relative to reference filgrastim or filgrastim-sndz treatment over up to 14 days.

Figure 1. Comparative cost analysis by product over 14 days (A) and associated savings (loss) by product pairs (B) for the COSTMED scenario.

Figure 2. Comparative cost analysis by product over 14 days (A) and associated savings (loss) by product pairs (B) for the SELFADMIN scenario.

Figure 3. Comparative cost analysis by product over 14 days (A) and associated savings (loss) by product pairs (B) for the HPOSTART scenario.

Figure 4. Comparative cost analysis by product over 14 days (A) and associated savings (loss) by product pairs (B) for the HPOALL scenario.

Table 3. Comparative cost analysis of prophylaxis options for the COSTMED scenario.

Table 4. Comparative cost analysis of prophylaxis options for the SELFADMIN scenario.

Table 5. Comparative cost analysis of prophylaxis options for the HPOSTART scenario.

Table 6. Comparative cost analysis of prophylaxis options for the HPOALL scenario.

In the COSTMED scenario (; ), the cumulative cost of prophylaxis with reference filgrastim evolves from its unit cost of $283 (1 day) to $3,966 (14 days), compared to $218 to $3,051 for filgrastim-sndz, for cost-savings with filgrastim-sndz ranging from $65 for a 1-day to $916 for a 14-day regimen. When comparing reference filgrastim to pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector, both single-dose prophylaxis options only turn cost-saving by $82 at 14 days of reference filgrastim treatment. At no point over a treatment regimen of up to 14 daily filgrastim-sndz injections do pegfilgrastim and pegfilgrastim-injector yield a savings benefit. Filgrastim-sndz retains marginal savings of $834 at 14 days, but may save $3,666 if only 1 day of filgrastim-sndz prophylaxis is administered.

In the SELFADMIN scenario (; ), and similar to the COSTMED scenario, the cumulative cost of prophylaxis with reference filgrastim ranges from $283 (1 day) to $3,966 (14 days), compared to $218 to $3,051 for filgrastim-sndz, yielding cost-savings with filgrastim-sndz from $65 for a 1-day to $916 for a 14-day regimen. Both pegfilgrastim and pegfilgrastim-injector turn cost-saving only at 14 days of reference filgrastim prophylaxis by $82 and $57, respectively. Here too, at no point over a treatment regimen of up to 14 daily filgrastim-sndz injections do pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector yield a savings benefit. Filgrastim-sndz retains marginal savings of $834 over pegfilgrastim and $859 over pegfilgrastim-injector at 14 days, but may save $3,666 and $3,692, respectively, if only 1 day of filgrastim-sndz prophylaxis is prescribed.

In the HPOSTART scenario (; ), the cumulative cost of prophylaxis with reference filgrastim progresses from $326 (1 day) to $4,009 (14 days), compared to $260 to $3,093 for filgrastim-sndz, yielding cost-savings with filgrastim-sndz from $65 for a 1-day to $916 for a 14-day regimen. Both pegfilgrastim and pegfilgrastim-injector turn cost-saving by, respectively, $82 and $99 at 14 days of reference filgrastim prophylaxis. Again, at no point over a prophylaxis regimen of up to 14 daily filgrastim-sndz injections do pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector yield a savings benefit. Filgrastim-sndz retains marginal savings of $834 over pegfilgrastim and $817 over pegfilgrastim-injector at 14 days, but may save $3,666 and $3,649, respectively, if only 1 day of filgrastim-sndz prophylaxis is given.

Lastly, in the HPOALL scenario (; ), the cumulative cost of reference filgrastim prophylaxis increases from $326 (1 day) to $4,559 (14 days), compared to $260 to $3,643 for filgrastim-sndz, yielding cost-savings with filgrastim-sndz from $65 for a 1-day to $916 for a 14-day regimen. Both pegfilgrastim ($306 to $632) and pegfilgrastim-injector ($323 to $649) are cost-saving from 13 days of reference filgrastim prophylaxis. At no point over up to 14 daily filgrastim-sndz injections do pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector yield a savings benefit. Filgrastim-sndz retains marginal savings of $284 over pegfilgrastim and $267 over pegfilgrastim-injector at 14 days, but may save $3,666 and $3,649, respectively, if only 1 day of filgrastim-sndz prophylaxis is prescribed.

Results of the above ASP-based analyses, but using the WAC instead, are included in the Supplementary Materials as Tables S1–S6 and Figures S1–S4.

Case studies

In the case of the patient with HER2-negative breast cancer treated with six cycles of TAC and receiving GCSF support for all cycles with either pegfilgrastim or 11 days of filgrastim-sndz or reference filgrastim, the costs of prophylaxis as prescribed range from $2,862 for filgrastim-sndz to $3,582 for pegfilgrastim (). Prophylaxis with filgrastim-sndz yields savings over reference filgrastim of $719 per cycle and $4,316 over six cycles; savings over pegfilgrastim of $1,064 per cycle and $6,385 over six cycles; and savings over pegfilgrastim-injector of $1,047 per cycle and $6,284 over six cycles.

Table 7. Case studies using the HPOALL scenario.

In the case of the patient with DLBCL receiving GCSF support for the remaining four cycles of his R-CHOP-21 regimen following hospitalization for febrile neutropenia, and whose insurance company authorized 7 days of standard filgrastim while denying single-administration pegfilgrastim per cycle, the total prophylaxis costs per cycle were $1,821 for filgrastim-sndz vs $2,279 for reference filgrastim, for savings of $458 per cycle and $1,831 over four cycles (). The insurer denial of pegfilgrastim and the use of filgrastim-sndz instead resulted in savings of $2,105 per cycle and $8,420 over four cycles. The corresponding savings over pegfilgrastim-injector prophylaxis were $2,088 and $8,353.

Discussion

The economic analyses for the US reported here shows consistently that filgrastim-sndz is the least expensive and, therefore, economically the most cost-efficient method of prophylaxis for cancer patients at risk for developing (febrile) neutropenia due to the myelotoxicity of their chemotherapy regimen. Filgrastim-sndz yields cost-savings of $65 per injection over reference filgrastim, whether one only considers the cost of drug or also the cost of administration, whether patients self-administer filgrastim, whether prophylaxis is initiated at the HPO, or whether all injections are given at the HPO. Filgrastim-sndz also yields significant cost-savings relative to single-administration pegfilgrastim and pegfilgrastim-injector, although these are a function of the number of filgrastim-sndz administrations. The cost of prophylaxis with filgrastim-sndz stays significantly below that of prophylaxis with pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector, regardless of administration scenario and the number of days of filgrastim prophylaxis prescribed. Thus, in the 5–7 day filgrastim regimens that seem to have become common practice across many tumor typesCitation30,Citation31, substituting filgrastim-sndz for reference filgrastim yields cost-savings between $327–$458 per chemotherapy cycle, while using filgrastim-sndz instead of pegfilgrastim generates savings between $2,105–$2,795 per cycle (the corresponding figures for pegfilgrastim-injector are $2,088 and $2,821). Considering the therapeutic similarity of filgrastim and pegfilgrastim, filgrastim-sndz offers the most economical option in the prophylaxis of (febrile) neutropenia in cancer patients undergoing myelotoxic chemotherapy.

As in EuropeCitation23, the cost-savings that can be achieved with filgrastim-sndz in the US are significant, which is critical considering the concerns about rising drug costs and the debates about strategies to reduce spending on pharmaceuticals. The market adoption signals from Europe are encouraging. According to QuintilesIMS, biosimilars accounted for about a quarter of sales of all biologics with expired EU patents in 2013, with significant country-to-country variation pointing at sustained growth opportunities for biosimilar productsCitation32–34. Biosimilar filgrastim has reached market shares upward of 60% across European countries. It constitutes a large proportion of the US$490 million spent on biosimilars in the EU G5 in 2015Citation32,Citation35.

These are potentially encouraging trends for biosimilar filgrastim in the US. Adopting filgrastim-sndz, for instance, will translate into considerable cost-savings without compromising the effectiveness and safety of prophylaxis. The US indeed has one of the highest generic adoption rates among high-income countries, and this is likely to extend into biosimilars. In 2014, 88% of the 4.3 billion prescriptions in the US were filled with generics, resulting in $254 billion in savings, and accounting for only 28% of total drug spending that yearCitation36. Consider in this regard the Oncology Care Model currently being evaluated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid ServicesCitation37. In this episode-based payment model, providers are paid on the basis of performance and financial accountabilityCitation38, thus incentivizing quality and cost to deliver value. Thus, with filgrastim-sndz and reference filgrastim therapeutically similar, the same quality of prophylaxis can be assured with filgrastim-sndz, and the lower cost achieves both efficiency and value.

In addition to the direct cost-savings that can be achieved with prophylaxis with filgrastim-sndz, there is another equation that is likely to be impacted favorably. As pegfilgrastim is non-inferior to reference filgrastim, and filgrastim-sndz was shown to yield similar efficacy and safety outcomes as filgrastim, it follows that filgrastim-sndz can be considered to be as efficacious as all three originator alternatives. Further, the real-world effectiveness of filgrastim-sndz was demonstrated in the MONITOR-GCSF studyCitation31. Hence, the pharmacotherapeutic benefit of filgrastim-sndz should be considered similar to that of originator alternatives. In the context of value-based formulary decision-making, whether at the payer or at the provider level, the cost per benefits achieved should be lower. Thus, using filgrastim-sndz instead of daily reference filgrastim or single-administration pegfilgrastim or pegfilgrastim-injector meets the triple evidence criteria of effectiveness, cost of treatment, and clinical benefits, resulting in a lower cost/benefit ratio.

The need to balance savings and outcomes is underscored by the anecdotal evidence from cancer clinics of some US payers denying GCSF support with pegfilgrastim and authorizing up to 7 days of filgrastim instead. Per our analyses, prophylaxis for 7 days with reference filgrastim in lieu of pegfilgrastim would yield savings of $1,647 per cycle in the HPOALL scenario and $1,901 per cycle in the remaining scenarios. Moreover, using filgrastim-sndz instead of reference filgrastim would generate an additional $458 in savings in all scenarios evaluated.

Cost-savings from prophylaxis with filgrastim-sndz bring two additional, budget-neutral benefits to payers and buyers. The savings can be applied to provide more patients with access to GCSF support with filgrastim-sndz. Similarly, the savings can provide expanded access to high-cost curative cancer treatments on a budget-neutral basis, as Sun et al.Citation39 showed for rituximab and trastuzumab in a EU G5 simulation for a panel of 10,000 patients converted from reference filgrastim to filgrastim-sndz.

We considered various durations of filgrastim prophylaxis. The standard recommendation is to treat for up to 14 days or through the absolute neutrophil nadir induced by chemotherapy until the count has reached 10,000/mm3. On the other hand, prophylaxis patterns observed in routine clinical practice cluster around 4–7 days of filgrastim supportCitation30,Citation31. Further, the European MONITOR-GCSF study found that the conventional algorithm of providing growth factor support to patients treated with myelotoxic regimens with >20% febrile neutropenia risk or to high-risk patients receiving regimens with 10–20% risk may not be adhered to in routine clinical practiceCitation31,Citation40. In fact, 26% of patients were over-prophylacted relative to the EORTCCitation13 guidelines, 57% were correctly-prophylacted, and 17% under-prophylacted. Over-prophylaxis was consistently associated with and predictive of better outcomesCitation40,Citation41. It is evident that a quarter century of clinical experience with filgrastim has led to a maturity in treatment patterns that may be inconsistent with the initial evidence from randomized controlled trials and with practice guidelines based on this evidence. While shorter courses of filgrastim prophylaxis may generate cost-savings, they have been linked to an increase in the risk of hospitalization, which may offset or exceed any savings achieved. Conversely, each additional day of filgrastim prophylaxis reduced the risk of hospitalization by 8–23%, depending on tumor typeCitation30.

We assumed similar efficacy and safety of filgrastim-sndz, reference filgrastim, and pegfilgrastim, and this on the basis of evidence of the non-inferiority trials of filgrastim and pegfilgrastimCitation15,Citation16, the equivalence of filgrastim-sndz and reference filgrastim as evidenced in the European registration studiesCitation42–44, and triangulating filgrastim-sndz to pegfilgrastim. The assumption of similarity of reference filgrastim and pegfilgrastim has been challenged based on non-controlled post-approval studies and meta-analyses sponsored by the manufacturer. Understandable from a strategic point of view, if marketing authorization can be obtained on the basis of the non-inferiority trials of pegfilgrastim to filgrastim, this approach might be preferable over the risk of a superiority trial failing or an equivalence trial falling outside the pre-specified margin. For the same reasons, manufacturers are disinclined to sponsor head-to-head trials post-approval. Notwithstanding, they will look for (the appearance of) superiority from non-controlled retrospective or prospective studies or from meta-analyses when the only direct RCT evidence is from the pivotal non-inferiority trials. Our position taken in the analyses reported herein is that RCT-level evidence is the only evidence permitting inferences of causality. In the absence of RCT-level superiority data, all that is established is that pegfilgrastim is non-inferior to filgrastim; and by triangulation to filgrastim-sndz.

Our analyses build upon, but also extend the Aapro et al.Citation23 findings to the more heterogeneous payer market in the US. In addition to the cost-of-drug analyses (COSTMED) for the US, we added scenarios that varied the role of patient and provider to enhance the applicability of our analyses to clinical practice. Although the incremental cost implications are minimal, we included the pegfilgrastim-injector, which was approved in 2015. We illustrate our analyses with two hypothetical case studies to increase the relevance of our analyses to the clinical setting and enhance the accessibility of our analyses to practicing clinicians.

Even though the data look similar, there are differences between the COSTMED and SELFADMIN scenarios. Under COSTMED, pegfilgrastim and pegfilgrastim-injector are analyzed as one, because these two options are priced the same. Under SELF-ADMIN, the pegfilgrastim-injector cannot be self-administered and must be applied by a clinician, hence the cost differential. Relatedly, in the ASP analyses pegfilgrastim and pegfilgrastim-injector show cost-savings over reference filgrastim, but not filgrastim-sndz, in the COSTMED, SELFADMIN, and HPOSTART scenarios relative to 14 doses of reference filgrastim, and in the HPOALL scenario relative to 13 doses of reference filgrastim. These savings for the pegylated formulations do not appear in the WAC analyses. This is due to asymmetry in the WAC over ASP ratios of the agents of interest. The reference filgrastim WAC price is 1.1447 over the ASP price, while the pegfilgrastim WAC price is 1.3273 over ASP prices. Note also that, in daily clinical practice, reference filgrastim is infrequently prescribed for such durations.

The Supplemental Materials feature a replication of our primary analyses, which used the ASP as a cost base, with analyses using the WAC. The WAC-based cost inputs were considerably higher than those based on the ASP, resulting in differences in price of 23.4% for filgrastim-sndz, 13.5% for reference filgrastim, and 28.1% for pegfilgrastim and the pegfilgrastim-injector. This yielded significantly greater savings than those seen in the ASP analyses.

While our analyses provide robust estimates of savings that can be achieved from conversion to filgrastim-sndz, several questions remain to be answered and should be the subject of future research. A case could be made that the convenience of a single administration, whether economic in terms of (direct) patient and provider costs or clinical in terms of reduced patient discomfort compared to multiple injections or infusions, should be incorporated in economic evaluations. It remains unknown how many daily filgrastim injections are necessary to minimize the risk of adverse outcomes—whether these outcomes are severe or febrile neutropenia episodes, hospitalizations, or chemotherapy disturbances—and the associated costs. We used publicly available cost inputs, which may not reflect all the incentives that manufacturers may extend to buyers and the contracts that group purchasing organizations may be able to secure on behalf of their members. The impact of bid-based or value-based contracting in securing volume contracts and pitching biosimilar vs originator products in formulary decisions remains to be studied as well. As our study was a cost-efficiency study based on established similarity in efficacy and safety, the analyses did not consider these variables. Hence, the cost of CIN and FN episodes and CIN/FN-related hospitalizations or chemotherapy disturbances was not included, as these would be constant across treatment options. The focus being on the cost of medication and administration, our analyses did not include indirect and other treatment-related costs. Data on discounts and rebates are confidential and could not be integrated into the model; hence, we had to rely on front-end estimates such as the ASP for our primary and the WAC for our secondary analyses.

Conclusion

In these cost-efficiency analyses, (febrile) neutropenia prophylaxis in cancer patients undergoing myelotoxic chemotherapy with filgrastim-sndz, a biosimilar filgrastim, was associated consistently with significant cost-savings over prophylaxis with reference filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, and pegfilgrastim-injector, and this across various administration scenarios. With filgrastim and pegfilgrastim being pharmacotherapeutically similar, the analyses show that, from a cost-efficiency perspective, there is no compelling rationale for prophylaxis with reference filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, or pegfilgrastim-injector compared to filgrastim-sndz.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was sponsored by Sandoz, Inc.

Declaration of financial/other interests

AM serves on a Speakers Bureau and Steering Committee for Sandoz, Inc. He was subcontracted by Matrix45 for work on this project. KC, MB, and SB are employees of Sandoz, Inc., the study sponsor. IA and KM are employees of Matrix45, which was contracted by Sandoz, Inc. to conduct the simulations. By company policy, employees are prohibited from owning equity in client organizations (except through mutual funds or other independently administered collective investment instruments) or contracting independently with client organizations. Matrix45 provides similar services to those described in this article to other biopharmaceutical companies on a non-exclusivity basis. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

This study was presented as a poster at the Annual Meeting of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, June 22–24, 2017 in Washington, DC.

Supplemental Materials

Download MS Word (507 KB)References

- Lalami Y, Paesmans M, Aoun M, et al. A prospective randomized evaluation of G-CSF or G-CSF plus oral antibiotics in chemotherapy-treated patients at high risk of developing febrile neutropenia. Support Care Canc 2004;12:725-7-30

- Lyman GH, Lyman CH, Agboola O. Risk models for predicting chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. Oncologist 2005;10:427-37

- Kuderer N, Dale D, Crawford J, et al. Impact of primary prophylaxis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor or febrile neutropenia and mortality in adult cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3158-67

- Paessens B, von Schilling C, Berger K, et al. Health resource consumption and costs attributable to chemotherapy-induced toxicity in German routine hospital care in lymphoproliferative disorder and NSCLC patients. Ann Oncol 2011;22:2310-19

- Weycker D, Barron R, Kartashov A, et al. Incidence, treatment, and consequences of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in the inpatient and outpatient settings. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2014;20:190-8

- Lyman GH, Dale DC, Culakova E, et al. The impact of the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on chemotherapy dose intensity and cancer survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Oncol 2013;24:2475-84

- Wildiers H, Reiser M. Relative dose intensity of chemotherapy and its impact on outcomes in patients with early breast cancer or aggressive lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2011;77:221-40

- Calhoun E, Chang CH, Welshman E, et al. The impact of chemotherapy delays on quality of life in patients with cancer. J Support Oncol 2004;2;64-5

- Wingard JR, Elmongy M. Strategies for minimizing complications of neutropenia: Prophylactic myeloid growth factors or antibiotics. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2009;72:144-54

- Raposo CG, Marin AP, Barón MG. Colony-stimulating factors: clinical evidence for treatment and prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia. Clin Translat Oncol 2006;8:729-34

- NEUPOGEN® (filgrastim) Prescribing Information. Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA; June 2016. http://pi.amgen.com/∼/media/amgen/repositorysites/pi-amgen-com/neupogen/neupogen_pi_hcp_english.ashx. [Last accessed 11 July 2017]

- NEULASTA® (pegfilgrastim) Prescribing Information. Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA; December 2016. http://pi.amgen.com/∼/media/amgen/repositorysites/pi-amgen-com/neulasta/neulasta_pi_hcp_english.ashx. [Last accessed 11 July 2017]

- Aapro MS, Bohlius J, Cameron DA. et al. 2010 update of EORTC guidelines for the use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to reduce the incidence of chemotherapy-induced febrile neu- tropenia in adult patients with lymphoproliferative disorders and solid tumours. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:8-32

- National Comprehensive Center Network. 2016 NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Myeloid growth factors version 2.2016. 2016;1–47. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloid_growth.pdf. [Last accessed 11 July 2017]

- Holmes FA, O’Shaughnessy JA, Vukelja S, et al. Blinded, randomized, multicenter study to evaluate single administration pegfilgrastim once per cycle versus daily filgrastim as an adjunct to chemotherapy in patients with high-risk stage II or stage III/IV breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:727-31

- Green MD, Koebl H, Baselga J, et al. A randomized double-blind multicenter phase III study of fixed-dose single-administration pegfilgrastim versus daily filgrastim in patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2003;14:29-35

- Siena S, Piccart MJ, Holmes FA, et al. A combined analysis of two pivotal randomized trials of single dose pegfilgrastim per chemotherapy cycle and daily filgrastim in patients with stage II-IV breast cancer. Oncol Rep 2003;19:715-24

- Pinto L, Liu Z, Doan Q, et al. Comparison of pegfilgrastim with filgrastim on febrile neutropenia, grade IV neutropenia and bone pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;2283-95

- Cooper KL, Madan J, Whyte S, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factors for febrile neutropenia prophylaxis following chemotherapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2011;11:404

- Wang L, Baser O, Kutikova L, et al. The impact of primary prophylaxis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factors on febrile neutropenia during chemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Canc 2015;23:3131-40

- Klastersky J, Awada A. Prevention of febrile neutropenia in chemotherapy-treated cancer patients: pegylated versus standard myeloid colony stimulating factors. Do we have a choice? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2011;78:17-23

- von Minckwitz G, Kümmel S, du Bois A, et al. Pegfilgrastim ± ciproflaxin for primary prophylaxis with TAX (docetaxel/doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide) chemotherapy for breast cancer. Results from the GEPATRIO study. Ann Oncol 2008;19:292-8

- Aapro M, Cornes P, Abraham I. Comparative cost-efficiency across the European G5 countries of various regimens of filgrastim, biosimilar filgrastim, and pegfilgrastim to reduce the incidence of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2012;18:171-9

- Trueman P, Drummond M, Hutton J. Developing guidance for budget impact analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2001;19:609-21

- Lyman GH, Lalla A, Barron RL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pegfilgrastim versus filgrastim primary prophylaxis in women with early-stage breast cancer receiving chemotherapy in the United States. Clin Ther 2009;31:1092-104

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Part B Drug Average Sales Price. 2017 ASP Drug Pricing Files: January 2017 ASP Pricing File. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Part-B-Drugs/McrPartBDrugAvgSalesPrice/2017ASPFiles.html. [Last accessed 11 July 2017]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicare Learning Network. January 2017 Update of the Ambulatory Surgical Center (ASC) Payment System; 2016, MM9923. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/Downloads/MM9923.pdf. [Last accessed 11 July 2017]

- AnalySource Online® (Selected from FDB MedKnowledge data included with permission and copyrighted by First Databank, Inc.). https://classic.analysource.com. [Last accessed 11 July 2017]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2016 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/PFS-Federal-Regulation-Notices-Items/CMS-1654-F.html. [Last accessed 11 July 2017]

- Weycker D, Hackett J, Edelsberg J, et al. Are shorter courses of filgrastim prophylaxis associated with increased risk of hospitalization? Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:402-7

- Gascón P, Aapro M, Ludwig H, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes in the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced (febrile) neutropenia with biosimilar filgrastim (the MONITOR-GCSF study). Support Care Canc 2016;24:911-25

- QuintilesIMS. Biosimilars in Europe. http://www.quintiles.com/microsites/biosimilars-knowledge-connect/biosimilars-by-region/europe. [Last accessed 26 March 2017]

- EuropaBio Guide on Biosimilars in Europe; September 2014. http://www.europabio.org/healthcare-biotech/publications/guide-biosimilars-europe. [Last accessed 11 July 2017]

- IMS Health Thought Leadership, November 2013. The global use of medicines: outlook through 2017. Report by the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. http://www.imshealth.com/en/thought-leadership/quintilesims-institute/reports/global-use-of-medicines-outlook-through-2017. [Last accessed 11 July 2017]

- GaBI Online; August 8, 2014. Use of biosimilars in Europe differs across countries. http://www.gabionline.net/Reports/Use-of-biosimilars-in-Europe-differs-across-countries. [Last accessed 11 July 2017]

- Generic Pharmaceutical Association. Generic drug savings in the US: Seventh Annual Edition; 2015. http://www.gphaonline.org/media/wysiwyg/PDF/GPhA_Savings_Report_2015.pdf. [Last accessed 11 July 2017]

- Kline RM, Bazell C, Smith E, et al. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: using an episode-based payment model to improve oncology care. J Oncol Pract 2015;11:114-16

- Abraham I, McBride A, MacDonald K. Arguing (about) the value of cancer care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016;14:1487-9

- Sun D, Andayani TM, Altyar A, et al. Potential cost savings from chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia with biosimilar filgrastim and expanded access to targeted antineoplastic treatment across the European Union G5 countries: a simulation study. Clin Ther 2015;37:842-57

- Bokemeyer C, Gascón P, Aapro M, et al. Over- and under-prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced (febrile) neutropenia relative to evidence-based guidelines is associated with differences in outcomes: findings from the MONITOR-GCSF study. Support Care Canc 2017;25:1819-28

- Aapro M, Ludwig H, Bokemeyer C, et al. Predictive modeling of the outcomes of chemotherapy-induced (febrile) neutropenia prophylaxis with biosimilar filgrastim (MONITOR-GCSF study). Ann Oncol 2016;27:2039-45

- Gascón P, Fuhr U, Sörgel F, et al. Development of a new G-CSF product based on biosimilarity assessment. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1419-29

- Tharmarajah S, Mohamed A, Bagalagel A, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of Zarzio® (EP2006), a biosimilar recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Biosimilars 2014;4:1-9

- Abraham I, Tharmarajah S, MacDonald K. Clinical safety of biosimilar recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factors. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2013;12:235-46