Abstract

Objective: To evaluate healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and costs among patients who initiated repository corticotropin injection (RCI; H.P. Acthar Gel) treatment for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Methods: Patients aged ≥18 years with ≥2 diagnoses for either RA or SLE between July 1, 2006 and April 30, 2015 were identified in the HealthCore Integrated Research Database. Index RCI date was the earliest date of a medical or pharmacy claim for RCI after diagnosis. Baseline characteristics, pre- and post-initiation HRU and costs were assessed using descriptive statistics.

Results: This study identified 180 RA patients (mean age = 60 years, 56% female) and 29 SLE patients (mean age = 45 years, 90% female) who initiated RCI. First RCI use averaged 7.1 and 22.6 months after the initial RA and SLE diagnosis, respectively. After RCI initiation, RA patients incurred significantly lower per-patient-per-month (PPPM) all-cause medical costs ($1,881 vs $682, p < .01) vs the pre-initiation period, driven by lower PPPM hospitalizations costs ($1,579 vs $503, p < .01). Overall PPPM healthcare costs were higher ($2,751 vs $5,487, p < .01) due to higher PPPM prescription costs ($869 vs $4,805, p < .01). Similarly, SLE patients had decreased PPPM hospitalization costs ($3,192 vs $799, p = .04) and increased PPPM prescription costs ($905 vs $7,443, p < .01) after initiating RCI; the difference in overall PPPM healthcare costs was not statistically significant likely, due to small sample size.

Conclusion: This study, across a heterogeneous population of variable disease duration, described clinical and healthcare utilization and costs of RA and SLE patients initiating RCI in a real-world setting. We observed that patients receiving RCI had lower utilization and costs for medical services in both disease populations, which partially offset the increased prescription costs by 30% and 37%. Future research is needed to explore factors associated with RCI initiation and its impact on long-term outcomes.

Introduction

Alternative therapeutic optionsCitation1, such as Repository Corticotropin Injection (RCI; H.P. Acthar Gel)Citation2–4, FDA approved for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)Citation5 may be used in patients who are inadequately controlled and/or unable to tolerate previously prescribed conventional treatmentsCitation5. RA and SLE are multi-system inflammatory autoimmune diseases that require immunosuppressive therapies. Available treatments for SLECitation6,Citation7 and RACitation8–10 have been associated with sub-optimal performance, and patients often seek additional therapeutic approaches.

RA, a common category of inflammatory rheumatic disease, is associated with deformities and joint destructionCitation11,Citation12. An estimated 1.3 million adults in the US are affected by RACitation13, with overall prevalence estimated at ∼0.5–1.0% in the general populationCitation11. RA imposes substantial costs, not only to affected patients and the families, but to the entire society. Patients with RA experience reduced quality-of-life, loss of work productivity, and substantial healthcare resource utilization (HRU)Citation14. Current RA treatments are aimed at symptom relief or to slow down or stop the course of disease progressionCitation15. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used to ease symptoms whereas corticosteroids, disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and biologics are used to decelerate disease activityCitation15. RCI is indicated as adjunctive therapy for short-term administration to provide respite during acute episodes or exacerbations of RACitation2–4.

A prototypical and chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease, SLE is associated with a spectrum of clinical presentations and periods of remission punctuated by unpredictable exacerbations, commonly referred to as flaresCitation1,Citation16–19. In the US, the incidence of SLE is estimated at ∼5 per 100,000 persons (0.005%), with prevalence around 100 per 100,000 persons (0.01%)Citation20–22. SLE flares are defined as amplified disease activity for defined durations in one or more organ systems involving new or worse clinical signs and symptoms. Among the devastating effects of SLE are functional impairment, poor quality-of-life, reduced productivity, unemployment, and increased mortalityCitation17,Citation18. These exacerbations contribute to progressive and irreversible organ damage over time in SLE patientsCitation17–19. In the absence of a cure, the goal of available SLE treatments focuses on managing symptoms, reducing disease activity, and appropriate management of disease flares. RCI has regulatory approval for the treatment of exacerbation or as maintenance therapy in selected cases of SLECitation3. RCI has been shown in an open-label trial to reduce disease activity significantly in patients with inadequately controlled SLE or who were unable to tolerate traditional treatmentsCitation1,Citation23.

Data from a recently available study suggested that RCI treatment may result in decreased use of prednisone, DMARDS, and biologic agentsCitation24. Furthermore, results from another recently published study indicated that RCI use among patients with the inflammatory conditions dermatomyositis or polymyositis had lower per-patient per month (PPPM) non-medication medical resource utilization compared with IVIg and rituximab treatments in the hospital settingCitation25.

To our knowledge, the study reported in this manuscript was the first study with the objective of describing the demographic and clinical characteristics of RA and SLE patients who commenced RCI therapy, and evaluating their healthcare resource utilization and costs before and after treatment initiation.

Methods

Cohorts and study design

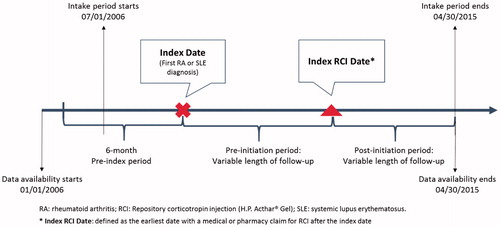

This retrospective observational study queried data from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database (HIRD) to identify two separate cohorts of patients—RA and SLE—who received RCI treatment between January 1, 2006 and April 30, 2015 (the study period). The HIRD is one of the largest actively curated commercial health plan databases in the US—it provided access to data on 36.8 million eligible members for this study. This monthly updated repository contains medical and pharmacy claims data for 14 large geographically dispersed health plans along with related information, including electronic laboratory data. The earliest date of diagnosis was defined as the index date, while the index RCI date was the earliest date of a medical or pharmacy claim for RCI after diagnosis (). The management of study data conformed to all applicable Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) rules. All data were de-identified throughout the study to preserve patient anonymity and confidentiality. This observational study was conducted under the research exception provisions of the Privacy Rule, 45 CFR 164.514(e), and was exempt from Investigational Review Board (IRB) informed consent requirements.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Each patient in the two study groups had ≥2 diagnoses for the target condition (RA or SLE) during the intake period, from July 1, 2007 to April 30, 2015 in order to allow for at least 6 months of continuous pre-index health plan enrollment, which was required to ensure that only incident patients (with recent RCI use) were included in the analysis. Patients were ≥18 years old at the index date and were required to have at least one claim for RCI therapy after the index date. Patients with evidence of RCI use during the 6-month pre-index period were excluded.

Observation periods

The index date and index RCI date divided the longitudinal follow-up into three continuous observation periods: 6-month pre-index, pre-initiation, and post-initiation period. The observation period was from 2006–2015; however, patients may have variable follow-up during the observation period. Patients were followed-up until the end of their continuous health plan enrollment or the end of the study period (April 30, 2015).

Key outcomes

All-cause and disease-related HRU, including hospitalization, emergency department (ED) visit, outpatient encounter, skilled nursing facility visit, and pharmacy prescription, were evaluated during the pre- and post-initiation periods. For hospitalizations and ED visits we reported the number of patients per 1,000 patient years, whereas for outpatient encounters and prescription fills, we reported the number of events per patient year. Disease-related HRU and costs included HRU and costs associated with diagnosis codes and medications for RA (for the RA cohort); and diagnosis codes and medications for SLE (for the SLE cohort). The corresponding all-cause and disease-related healthcare costs were captured which included both health plan paid and patient paid costs. SLE exacerbation at the time of the RCI initiation was identified using a complex claims-based algorithm based on SLE-related HRU and medication use (Appendix A).

Statistical methods

To adjust for variable length of follow-up during the pre- and post-initiation period, comorbid conditions, medication use, and healthcare utilization were reported as rates (number of patients per 1,000 patient years, or number of events per patient year), while costs were adjusted on a per-patient-per-month (PPPM) basis. Outcomes of interest in the pre- and post-initiation period were compared using statistical testing described as follows: The proportion of patients with the event of interest was compared using logistic regression offset by follow-up time. After studying the proportion of patients with the events of interest and using one predictor variable offset by follow-up time, it was determined that logistic regression would be appropriate for this analysis. The number of visits was evaluated with Generalized Linear Model (GLM) with negative binomial or Poisson distribution with log link function offset by follow-up time. Costs were assessed using GLM with gamma distribution and log link function weighted by follow-up time. Alpha was set at 0.05 for statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Study patients

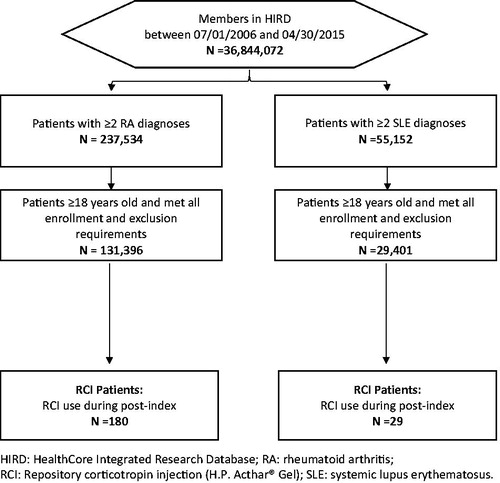

Among 131,396 RA patients and 29,401 SLE patients identified from HIRD, 180 (0.1%) and 29 (0.1%) patients initiated RCI, respectively ().

Demographic and clinical characteristics of RCI initiators ()

RA cohort

RCI patients were 60.5 (SD = 15.7) years old on average at the time of RA diagnosis, and 56.1% were female. Most RCI patients were enrolled in a preferred provider organization (PPO, 90.0%), as shown in . Others were enrolled in a health maintenance organization (HMO, 6.1%) or consumer-driven health plan (CDHP, 3.9%), and 66.1% of patients were on Medicare Advantage coverage. Most RCI patients resided in the Southern region of the US (75.0%), followed by West (12.8%), Midwest (7.2%), and Northeast (5.0%). Average Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index (DCI) scoreCitation26 was 1.1 (SD = 1.4). Among the comorbid conditions examined, hypertension (348 per 1,000 patient years), SLE (169), depression (141), anemia (132), and diabetes mellitus (132) were most prevalent in this patient population.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of RCI patients in the RA and SLE population.

Table 2. All-cause and disease-related healthcare utilization during pre- and post-initiation period.

Table 3. All-cause and disease-related healthcare cost PPPM during pre- and post-initiation period.

SLE cohort

RCI patients were 45.1 (SD = 12.9) years old on average at the time of SLE diagnosis and 89.7% were female (). The majority were enrolled in a PPO (65.5%), others were enrolled in a HMO (17.2%) or CDHP (17.2%). There were 6.9% of RCI patients with Medicare Advantage coverage. Most RCI patients resided in the Southern region of the US (41.4%), followed by West (34.5%), Midwest (20.7%), and Northeast (3.4%). Average DCI score was 2.6 (SD = 1.6). Among the comorbid conditions examined, hypertension (293 per 1,000 patient years), anemia (201), depression (201), anxiety (183), and RA (165) were most prevalent in this patient population.

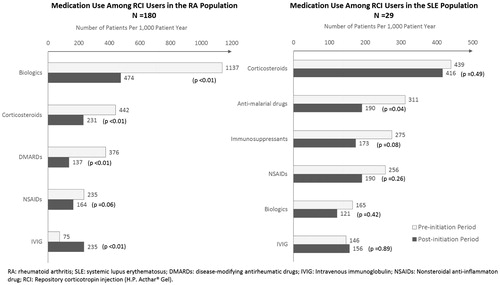

Medication use during pre- and post-initiation period ()

RA cohort

Prior to RCI initiation, biologics were the most commonly used medication class (1,137 patients per 1,000 patient year), followed by corticosteroids (442), non-biologic DMARDs (376), NSAIDs (235), and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG, 75). After RCI initiation, patients used significantly fewer biologics (1,137 vs 474 patients per 1,000 patient-years, 58.3% reduction, p < .01), corticosteroids (442 vs 231, 47.7% reduction, p < .01), and non-biologic DMARDs (376 vs 137, 63.6% reduction, p < .01), while they used more IVIG (75 vs 235, 213% increase, p < .01) compared with the pre-initiation period.

SLE cohort

Prior to RCI initiation, corticosteroids were the most commonly used medication class (439 patients per 1,000 patient year), followed by anti-malarial drugs (311), immunosuppressants (275), NSAIDs (256), biologics (165), and IVIG (146). After RCI initiation, patients used significantly fewer anti-malarial drugs (311 vs 190 patients per 1,000 patient-years, 38.9% reduction, p = .04) compared with the pre-initiation period. In addition, trends of fewer use of corticosteroids (439 vs 416), immunosuppressants (275 vs 173), NSAIDs (256 vs 190), and biologics (165 vs 121) were observed. However, due to the small sample size, these results were not determined to be statistically significant.

All-cause and disease-related healthcare utilization during pre- and post-initiation ()

RA cohort

On average, patients initiated RCI 7.1 (SD = 14.9) months after being diagnosed with RA. Following the initiation, RCI patients were followed for an average of 17.0 (SD = 19.8) months, during which RCI was filled 4.8 (SD = 4.6) times. After RCI initiation, there were significant reductions in HRU across all types of medical services for both all-cause and RA-related measures compared to the pre-initiation period: 40–69% reductions in hospitalization (all-cause: 42 vs 25 patients per 1,000 patient-years, p < .01; RA-related: 13 vs 4, p < .01); 52–88% reductions in ED visit (all-cause: 48 vs 23 patients per 1,000 patient-years, p = .04; RA-related: 8 vs 1, p < .01); and 16–50% reductions in outpatient service (all-cause: 56 vs 47 encounters per patient-year, p < .01; RA-related: 10 vs 5, p < .01). The study also found a 46.6% reduction in the rate of all-cause prescription fills (73 vs 39 fills per patient-year, p = .26) and a 70.6% reduction in the rate of RA-related prescription fills (17 vs 5 fills per patient-year, p = .06) during the post-initiation period, as compared to the pre-initiation period, although these results were not statistically significant.

SLE cohort

On average, SLE patients initiated RCI 22.6 (SD = 21.8) months after being diagnosed. Twenty-eight (96.6%) patients had a flare at the time of initiation; of these patients, 26 (89.7%) had a moderate-to-severe flare around the time of their RCI index date (data not presented in tables). Following the initiation, RCI patients were followed for an average of 23.9 (SD = 20.9) months, during which RCI was filled 3.7 (SD = 5.4) times. After RCI initiation, patients utilized significantly fewer outpatient services (44 vs 40 encounters per patient year, p < .01) and fewer prescription fills (44 vs 39 fills per patient year, p < .01) compared with the pre-initiation period. The study found a 20.2% reduction in the rate of all-cause hospitalizations (238 vs 190 patients per 1,000 patient year, p = .40) and a 12.6% reduction in the rate of all-cause emergency department visits (238 vs 208 patients per 1,000 patient year, p = .59) during the post-initiation period, as compared to the pre-initiation period, although these results were not statistically significant.

All-cause and disease-related healthcare cost during pre- and post-initiation ()

RA cohort

After RCI initiation, patients incurred significantly lower PPPM all-cause ($1,881 vs $682, p < .01) and RA-related ($658 vs $93, p < .01) medical costs compared with the pre-initiation period, mainly driven by lower PPPM costs for hospitalization (all-cause: $1,579 vs $503, p < .01; RA-related: $614 vs $86, p < .01). However, overall PPPM costs were significantly higher (all-cause: $2,751 vs $5,487, p < .01; RA-related: $931 vs $4,472, p < .01) during the post-initiation period, as compared to the pre-initiation period, largely due to higher PPPM costs for prescriptions (all-cause: $869 vs $4,805, p < .01; RA-related: $273 vs $4,379, p < .01).

SLE cohort

After RCI initiation, patients incurred significantly lower PPPM SLE-related medical costs ($3,011 vs $893, p = .02) compared with the pre-initiation period, mainly driven by lower PPPM costs for SLE-related hospitalization ($2,444 vs $434, p = .02). However, overall SLE-related PPPM costs were significantly higher ($3,077 vs $7,522, p = .04) during the post-initiation period as compared to the pre-initiation period, largely due to higher PPPM costs for SLE-related prescriptions ($66 vs $6,629, p < .01). All-cause healthcare costs followed a similar trend that patients incurred significantly lower PPPM costs for all-cause hospitalization ($3,192 vs $799, p = .04), but significantly higher PPPM costs for prescription ($905 vs $7,443, p < .01) during the post-initiation period compared with the pre-initiation period.

Discussion

In this analysis of a large US health plan database of 36.8 million members, Repository Corticotropin Injection was initiated in a small sub-set of patients with RA (0.1%) and SLE (0.1%) over a 9-year period. After the initiation of RCI, there were significant reductions in HRU, compared with the pre-initiation period. For the RA cohort, hospitalization was reduced by 40–69%, ED visits were reduced by 52–88%, and outpatient visits were reduced by 16–50%. Biologic, non-biologic DMARD, and corticosteroid use were reduced by 58%, 48%, and 64%, respectively. Similar trends were observed in the SLE cohort, although the sample size was too small to evaluate many of the endpoints. Still, there were significant SLE-specific medical cost reductions of 70% ($3,011 vs $893, p = .02) compared with the pre-initiation period, mainly driven by lower PPPM costs for SLE-related hospitalization ($2,444 vs $434, p = .02). Overall PPPM costs were significantly higher for both RA and SLE during the post-initiation period as compared to the pre-initiation period (RA-related: $931 vs $4,472, p < .01; SLE-related: $3,077 vs $7,522, p = .04). This higher cost is primarily driven by higher PPPM costs for prescriptions (RA-related: $273 vs $4,379, p < .01; SLE-related: $66 vs $6,629, p < .01). Consequently, the reduced medical resource use partially offset the drug costs.

Despite the size of the overall RA and SLE cohorts, the population treated with RCI represented only a small proportion (0.1%) of the cohort with similar severity of disease. This low level of utilization has been reported in the literature. Fiechtner and MontroyCitation1, reporting on an open-label study of RCI treatment among moderate or severe SLE patients, who had an average of 3.5 previous SLE treatments prior to RCI, noted that, despite the product’s regulatory approval to treat SLE in 1952, many physicians were unaware of this treatment option, and treatment outcomes data were still limited. It is notable that, although the patients in the Fiechtner and MontroyCitation1 study had moderately-to-severely active SLE, following treatment with RCI, the primary endpoint, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) improvement, was reached at all observation times (p < .05), and statistically significant improvements were observed for most other parameters by the end of the study. In addition, RCI was evaluated in a prospective, randomized, double-blind trialCitation23. Patients with persistently active SLE were given either RCI with background therapy, or background therapy only. The study results might indicate a role by RCI in improvements in disease activity in a select SLE patient population with steroid-dependent persistent disease. These findings suggest that, although RCI is recommended later in the treatment cycle, often after other treatments such as corticosteroids have failed, that patients have experienced significant improvements after initiating treatment with this medication.

Overall, HRU decreased for study patients after they received RCI treatment. There was a significant reduction in the use of other RA (biologics, corticosteroids, and non-biologic DMARDS) and SLE (anti-malarials, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, NSAIDs and biologics) medications among patients with both diseases, with the notable exception of IVIG, which increased significantly among RA patients in the post-index period. In the RA population, there was a significant reduction in utilization of all-cause hospitalization, ED, and outpatient services after RCI initiation compared with the pre-initiation period. This trend also persisted for RA-related HRU. In the SLE population, the number of all-cause outpatient encounters was significantly lower, and there was a decrease in the number of prescription fills for non-RCI agents. In both the RA and SLE analyses, a trend of lower HRU and, thus, lower PPPM medical costs after the initiation of RCI compared to the pre-initiation period was observed, suggesting overall better disease control.

In the post-initiation period, the total PPPM costs were higher than the pre-initiation period driven by significantly higher PPPM pharmacy costs. Improvements across the medical cost categories partially offset the higher pharmacy costs.

This study described patient demographics, baseline clinical characteristics, and healthcare utilization and costs which laid the basis for future studies to identify factors associated with RCI initiation. That most SLE patients experienced a flare prior to RCI demonstrated a proper use situation, which can be rare. The use of RCI is infrequent, but its use appeared to provide benefits following the exhaustion off all traditional treatments. Such findings prompt the need for future studies to evaluate the longer-term (>24 month of follow-up) HRU and cost impacts of RCI treatment among patients with RA or SLE. This current study used the RCI patients as their own comparison, a method with the advantage of minimizing selection bias. Future research may compare a parallel group of non-RCI patients to explore differences in patient outcomes. Since RCI is generally reserved for difficult to treat patients, future studies must carefully address the significant selection bias.

Limitations

The findings of this study must be interpreted in light of a number of limitations, in particular the sample sizes, owing to small numbers of patients treated with RCI, even in a large national health plan database, which may be insufficient to detect significant differences. RCI has been approved by the FDA for 19 indications, and patients with comorbidities other than RA or SLE are not excluded from the study cohorts, which increases the potential for confounding. The use of administrative claims data derived from commercially insured health plan members limits the generalizability of these results across different patient populations. In claims data, medical care coding errors or omission and commission could have occurred. Our study database did not capture additional unpaid medical, counseling or supportive care, cash payments, alternate insurance enrollments, or participation in clinical trials by study subjects—which could have introduced interventions not accounted for in this study. In addition, claims data only yield limited patient information, often devoid of essential patient demographics and lifestyle behaviors, such as smoking status and dietary practices among others, that impact disease progression and influence medication adherence.

Conclusion

RCI was initiated by sub-sets of RA and SLE patients in a large commercial claims database. Although total costs in both the RA and the SLE cohorts were higher because of higher pharmacy costs, reductions in medical costs partially offset the higher pharmacy costs. The reduced HRU and costs could be indicative of improved disease control. This points to the need for additional and longer-term studies to assess the impact of RCI among patients with RA or SLE.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MP and GJW are employees of Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, which provided research funding to HealthCore (BW, GD, and TG). BP served as a consultant to Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals at the time of the study. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

B. Bernard Tulsi, MSc, provided writing and other editorial support for this project. We would also like to recognize Winnie Nelson, PharmD, MS, MBA, Senior Director HEOR for critical review of the manuscript.

References

- Fiechtner JJ, Montroy T. Treatment of moderately to severely active systemic lupus erythematosus with adrenocorticotropic hormone: a single-site, open-label trial. Lupus 2014;23:905-12

- Prescribing information of H.P. Acthar Gel. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022432s000lbl.pdf. [Last accessed 30 July 2015]

- H.P. Acthar® Gel (repository corticotropin injection) [prescribing information]. Mallinckrodt ARD, Inc. https://www.actharrheumatology.com/systemic-lupus-erythematosus/overview. [Last accessed 12 May 2016]

- Questcor Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Prescribing Information: Acthar. http://acthar.com/pdf/Acthar-PI.pdf. [Last accessed 27 March 2015]

- Lateef A, Petri M. Unmet medical needs in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2012;14(Suppl 4):S4

- Doria A, Gatto M, Iaccarino L, et al. Value and goals of treat-to-target in systemic lupus erythematosus: knowledge and foresight. Lupus 2015;24:507-15

- Doria A, Gatto M, Zen M, et al. Optimizing outcome in SLE: treating-to-target and definition of treatment goals. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:770-7

- Emery P. Optimizing outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to anti-TNF treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51(Suppl 5):v22-30

- Pavelka K, Kavanaugh AF, Rubbert-Roth A, et al. Optimizing outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate responses to disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51(Suppl 5):v12-21

- Rubbert-Roth A. Assessing the safety of biologic agents in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51(Suppl 5):v38-47

- CDC. Rheumatoid arthritis. http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/rheumatoid.htm. [Last accessed 27 February 2015]

- Salaffi F, Carotti M, Gasparini S, et al. The health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with a selected sample of healthy people. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:25

- Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:15-25

- Greenapple R. Trends in biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis: results from a survey of payers and providers. Am Health Drug Benefits 2012;5:83-92

- Arthritis Foundation. Rheumatoid arthritis treatment. http://www.arthritis.org/about-arthritis/types/rheumatoid-arthritis/treatment.php. [Last accessed 14 July 2015]

- Guidelines for referral and management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:1785-96

- Garris C, Jhingran P, Bass D, et al. Healthcare utilization and cost of systemic lupus erythematosus in a US managed care health plan. J Med Econ 2013;16:667-77

- Garris C, Shah M, Farrelly E. The prevalence and burden of systemic lupus erythematosus in a medicare population: retrospective analysis of medicare claims. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2015;13:9

- Ruperto N, Hanrahan LM, Alarcon GS, et al. International consensus for a definition of disease flare in lupus. Lupus 2011;20:453-62

- Balluz L, Philen R, Ortega L, et al. Investigation of systemic lupus erythematosus in Nogales, Arizona. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:1029-36

- Naleway AL, Davis ME, Greenlee RT, et al. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus in rural Wisconsin. Lupus 2005;14:862-6

- Uramoto KM, Michet CJ Jr, Thumboo J, et al. Trends in the incidence and mortality of systemic lupus erythematosus, 1950–1992. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:46-50

- Furie R, Mitrane M, Zhao E, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of repository corticotropin injection in patients with persistently active SLE: results of a phase 4, randomised, controlled pilot study. Lupus Sci Med 2016;3:e000180

- Myung G, Nelson WW, McMahon MA. Effects of repository corticotropin injection on medication use in patients with rheumatologic conditions: a claims data study. J Pharm Technol 2017;33:151-155

- Knight T, Bond TC, Popelar B, et al. Medical resource utilization in dermatomyositis/polymyositis patients treated with repository corticotropin injection, intravenous immunoglobulin, and/or rituximab. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2017;9:271-9

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613-19

- Kan H, Guerin A, Kaminsky MS, et al. A longitudinal analysis of costs associated with change in disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Med Econ 2013;16:793-800

Appendix A

This study used an algorithm to define SLE flares during the pre-index period. Flare episodes were identified based on flare severity and defined as followsCitation17,Citation27:

Mild flares

Initiation of hydroxychloroquine or another antimalarial; OR

Initiation of an oral corticosteroid with a prednisone equivalent dose of ≤7.5 mg/day; OR

Initiation of non-immunosuppressive therapy (NSAIDS, androgens).

Moderate flares

Initiation of an oral corticosteroid with a prednisone equivalent dose of >7.5 mg/day, but ≤40 mg/day; OR

Initiation of immunosuppressive therapy with the exception of cyclophosphamide; OR

Claim for an ER visit with a primary diagnosis of SLE with no inpatient admission within 1 day; OR

Claim for an ER or office visit with a primary or secondary diagnosis for a specified SLE-related condition (Appendix B).

Severe flares

Initiation of an oral corticosteroid with prednisone equivalent dose of >40 mg/day; OR

Initiation of cyclophosphamide; OR

Admission for an inpatient hospital stay with a primary diagnosis of SLE or a specified SLE-related condition (Appendix B).

Duration of each flare episode was limited to 30 days. If a flare episode of higher severity occurred during those 30 days, the length of the flare episode was limited to the time between the start of the original flare episode and the start of the flare episode of higher severity.

Appendix B.

Select list of SLE-related clinical conditions

Acute confusional state/psychosis

Aortitis

Arterial/Venous thrombosis

Aseptic meningitis

Cardiac tamponade

Cranial neuropathy

Intestinal pseudo-obstruction

Kidney Disease: End Stage Renal

Optic neuritis

Pulmonary hemorrhage

Stroke/TIA

Acute pancreatitis

Chorioretinitis

Demyelinating syndrome/Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy

Episcleritis/scleritis

Hemolytic anemia

Hepatitis (non-viral)

Ischemic necrosis of bone

Kidney Disease: Nephritis

Kidney Disease: Nephrotic syndrome

Kidney Disease: Other renal impairment

Lupus enteritidis/colitis

Mononeuropathy/polyneuropathy

Myelopathy

Myocarditis

Pericarditis

Pleurisy/pleural effusion

Pseudotumor cerebri

Seizure

Uveitis

Vasculitis (excluding aortitis)

Arthritis/Arthralgia

Dry eye/tear film insufficiency

Rash

Leukopenia

Neutropenia

Lymphocytopenia

Lymph node enlargement

Myalgia/myositis

Urticarial