Abstract

Background: A new depot formulation of paliperidone has been developed that provides effective treatment for schizophrenia for 3 months (PP3M). It has been tested in phase-3 trials, but no data on its cost-effectiveness have been published.

Purpose: To determine the cost-effectiveness of PP3M compared with once-monthly paliperidone (PP1M), haloperidol long-acting therapy (HAL-LAT), risperidone microspheres (RIS-LAT), and oral olanzapine (oral-OLZ) for treating chronic schizophrenia in The Netherlands.

Methods: A previous 1-year decision tree was adapted, based on local inputs supplemented with data from published literature. The primary analysis used DRG costs in 2016 euros from the insurer perspective, as derived from official lists. A micro-costing analysis was also conducted. For the costing scenario, official list prices were used. Clinical outcomes included relapses (treated as outpatients, requiring hospitalization, total), and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Rates and utility scores were derived from the literature. Economic outcomes were the incremental cost/QALY-gained or relapse-avoided. Model robustness was examined in scenario, 1-way, and probability sensitivity analyses.

Results: The expected cost was lowest with PP3M (8,781€), followed by PP1M (10,325€), HAL-LAT (11,278€), RIS-LAT (11,307€), and oral-OLZ (13,556€). PP3M had the fewest total relapses/patient (0.36, 0.94, 1.39, 1.21, and 1.70, respectively), hospitalizations (0.11, 0.46, 0.40, 0.56, and 0.57, respectively), emergency room visits (0.25, 0.48. 0.99, 0.65, and 1.14, respectively) and the most QALYs (0.847, 0.735, 0.709, 0.719, and 0.656, respectively). In both cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses, PP3M dominated all other drugs. Sensitivity analyses confirmed base case findings. In the costing analysis, total costs were, on average, 31.9% higher than DRGs.

Conclusions: PP3M dominated all commonly used drugs. It is cost-effective for treating chronic schizophrenia in the Netherlands. Results were robust over a wide range of sensitivity analyses. For patients requiring a depot medication, such as those with adherence problems, PP3M appears to be a good alternative anti-psychotic treatment.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a debilitating chronic mental health problem afflicting individuals worldwide, with no prospects of a cure. The 2010 Global Burden of Disease StudyCitation1 estimated that 21.5 million people are affected worldwide (∼3.1 per 1,000 inhabitants). That number (projected using population estimates)Citation2 would have become 23.1 million in 2016. However, rates vary across regions and differ between the sexes and ethnic groupsCitation3,Citation4. This disease affects men more than women, with a relative risk of 1.42 (95% CI = 1.30–1.56)Citation3,Citation5. In a national survey from the Netherlands, the estimated lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia was 4/1,000 in males and 3/1,000 in femalesCitation6. Estimates of the point prevalence in that country vary widely, ranging from 0.6–6.7 per 1,000Citation7–9. However, there is much variation, even among neighborhoodsCitation10.

This disease impacts society strongly and negativelyCitation1. People with schizophrenia have a substantially decreased level of functioningCitation11. Their quality-of-life is decreased when compared to individuals not afflicted with the diseaseCitation12,Citation13. Schizophrenia is also associated with an increased risk of premature mortality. Tenback et al.Citation14 reported a 2.6-fold increase in risk of death in persons with schizophrenia as compared with those not having the disease. Notably, there was no association between mortality and age at onset of the disease or current prescription of anti-psychotics. In a meta-analysis of RCTs that included 17,416 patients, Kishi et al.Citation15 concluded that mortality was associated with the disease and not the treatment drugs.

Schizophrenia further impacts society by the substantial amount of resources consumed by the healthcare systemCitation1,Citation16, and by those incurred by caregiversCitation17,Citation18. In the Netherlands, van der Lee et al.Citation19 estimated an average overall cost for psychiatric care of 31,071€per patient over 3 years. Inpatient care comprised 60% of the total, as compared with 31% for outpatient care and 9% for drugs. Clearly, avoiding hospitalizations is of major benefit in managing these patients.

Non-adherence and partial adherence have long been identified as major contributors to hospitalizationCitation20,Citation21. De Hert et al.Citation22 conducted a thorough meta-analysis of 36 placebo-controlled studies that examined 4,657 patients. Those receiving placebo had a risk of relapse that was 5-times higher than those treated with anti-psychotics. Furthermore, they reported an odds ratio of 3.36 for relapse in patients who had been stabilized, but either discontinued their drugs or took them intermittently.

Unfortunately, non-adherence and partial adherence to medications are not uncommon. One study reported a prevalence of 42.3% “non-compliant behaviors”Citation23. High rates of problems with adherence were also reported by Emsley et al.Citation24 in a survey of 4,120 nurses, mostly (>70%) from Europe. They estimated that 54% of all patients with schizophrenia were non-adherent or partially non-adherent. In a similar research, Kulkarni and Reeve-ParkerCitation25 reported that Australian psychiatrists estimated that 51% of all patients were either non-adherent or partially adherent. Thus, the problem is widespread and problematic.

Noordraven et al.Citation26 identified two factors strongly associated with reduced adherence which were motivation to continue medications and patients’ insight. To overcome these problems, depot formulations, or long-acting therapy (LAT) were developed. The first atypical anti-psychotic to appear on the market was risperidone (Risperdal Consta; RIS-LAT), which requires biweekly administrationCitation27. The next LAT was paliperidone palmitate (Xeplion; Invega Sustenna) in 2011Citation28, which may be injected monthly. These products have generally proven themselves to be effective, but some challenges and opportunities remain. For example, there are still problems with adherence and drug continuation, as well as polypharmacyCitation29,Citation30.

A novel advance to the treatment algorithm has been the production of a 3-month formulation (PP3M; Trevicta)Citation31. This drug has been tested in clinical trials, which have recently been published. Berwaerts et al.Citation32 compared PP3M (n = 160) to placebo (n = 145) over a period of more than 1 year. PP3M significantly delayed time to relapse in persons with schizophrenia. In a large (n = 1,016) 48-week trial, Savitz et al.Citation33 found that PP3M was non-inferior to PP1M, both in efficacy and tolerability.

PP3M and PP1M are both long-acting formulations of paliperidone, the only difference being their durations of action. On the other hand, the cost-effectiveness of this new 3-month formulation is presently unknown. In addition to that, there is no model published that analyzes and compares the cost-effectiveness of anti-psychotic drugs in The Netherlands. Therefore, the aim of this project was to determine the relative cost-effectiveness of PP3M vs four widely used anti-psychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia in The Netherlands.

Methods

This research was performed generally according to the recommendations for the economic evaluation of health technologies in The NetherlandsCitation34. The exception was that the analyses took the insurer perspective, including all direct medical care costs. Indirect costs were not included because they are not relevant to the analytic viewpoint. Also, the great majority of these patients are not fully employed, so relatively little cost is involvedCitation35,Citation36. As validation for not using the societal approach, we point to the work by Evers and AmentCitation7, who estimated that such indirect costs comprised less than 8% of the total cost of care. Although they did not include caregiver costs, that burden would be expected to be similar across drugs. Also, we did not consider the costs of treating adverse events due to the findings of two recent pharmacoeconomic analysesCitation37,Citation38. De Moor et al.Citation37 concluded that adverse events “contributed only marginally” to the overall cost, while Arteaga Duarte et al.Citation38 reported that the overall difference in treatments costs for adverse events amounted to a mere 7€. Along with other anti-psychotics, two previous studies have examined the three other drugs (RIS-LAT, HAL-LAT, and oral-OLZ)Citation39,Citation40. Edwards et al.Citation39 reported that the cost of treating adverse events was very low, comprising 0.8% of the total cost for RIS-LAT, 0.5% for HAL-LAT, and 1.3% for oral-OLZ. Obradovic et al.Citation40 produced quite similar results: 0.3% for RIS-LAT, 1.0% for HAL-LAT, and 0.7% for oral-OLZ. Therefore, it was felt that none of these costs was worth considering.

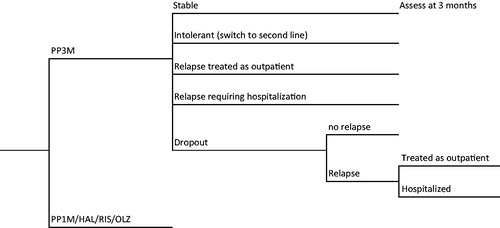

We adapted a previous decision tree model using an Excel spreadsheet, by adding a branch for PP3MCitation41. depicts the model structure. Local experts provided input into the standard practices involved in the management of the care of these patients. PP3M was the primary drug of interest; comparison drugs included PP1M, RIS-LAT, HAL-LAT, and oral olanzapine (oral-OLZ), which are the drugs that are commonly used in The Netherlands for patients with schizophrenia. We excluded two other LATs, olanzapine pamoate and aripiprazole, because neither drug is used extensively in The Netherlands, and real-life data are not available for themCitation42.

Figure 1. Decision tree used to model the economic analyses. Abbreviations. HAL, Haloperidol long acting injectable; RIS, risperidone long acting injectable; OLZ, olanzapine oral.

We assumed that all patients who discontinued due to adverse events or intolerance to a drug were immediately switched to second line treatment. In the case of lack of efficacy, patients could either have their doses of drug maximized or switched to alternate (second line) therapy. For PP3M, PP1M, RIS-LAT, and oral-OLZ, second line treatment was HAL-LAT; for HAL-LAT it was oral-OLZ. The rationale for using HAL-LAT as second line for PP3M, PP1M, and RIS-LAT is that these three drugs are all related (the first two consist of paliperidone, which is a metabolite of RIS)Citation28. Therefore, a different molecule is required, and an LAT is preferred in these patients. In the event of intolerance to or lack of efficacy from the second line drug, patients would be switched to clozapine, as per NICE recommendationsCitation43.

The clinical inputs for this analysis were derived from the published literature. To the extent possible, we used data from The Netherlands for the analysis. Rates (calculated at 1 year) were largely based on real world experience, with data observed in actual practice in The NetherlandsCitation42. In that study, 14.5 million prescriptions from The Netherlands were analyzed, representing 75% of the total market. Drugs assessed included PP1M, RIS-LAT, and HAL-LAT. To determine rates for PP3M, we applied results from the head-to-head trial between PP3M and PP1MCitation33, using the ratio between PP3M:PP1M and applying it to the rates calculated for PP1M. Finally, we estimated rates for oral-OLZ using the 1-year ratio between RIS-LAT and oral-OLZ from the study by Olivares et al.Citation44 and multiplied that ratio by the calculated rates for RIS-LAT. All of these rates are presented in .

Table 1. Clinical inputs and their sources.

To estimate the time to relapse in those who discontinued from each drug, we used results from patients who discontinued active treatment and were switched to placebo in the Kim et al.Citation45 study. That study presents the median number of days to relapse (50th percentile), as well as days for 25% of the patients to relapse (25th percentile). These numbers can then be used to determine the time for relapse in those who discontinue each drug. In the rare cases where data were not available (i.e. four cases), observed rates from Decuypere et al.Citation42 were pro-rated using ratios between drugs as reported in RCTs, using the approach described by Bucher et al.Citation46. That method adjusts rates from different studies by calculating a ratio of each drug against a common comparison drug. The ratio for each drug is then multiplied by a known standard rate. For PP3M, we projected rates from PP1M using the ratio of rates from the Savitz et al.Citation33 trial; for PP1M and oral-OLZ, RIS-LAT was used as the reference drug as there were many RCTs comparing these drugs. Clinical inputs and their sources are presented in .

To determine the length of stay of hospitalizations, we used data from Niaz and HaddadCitation47 and Spill et al.Citation48, who directly compared RIS-LAT with (mostly) oral anti-psychotics in mirror image studies. Patients receiving oral therapy stayed 61.7 days in hospital, while those on RIS-LAT stayed 31.6 days. We assumed that the other three long-acting treatments would have stays equal to that of RIS-LAT.

Two different approaches were taken for the costing of treatments. The primary analysis was based on the Dutch system of diagnosis related groups (DRGs). Under that system, clinics are reimbursed according to the number of minutes per year that healthcare providers spend with a patient. There are nine categories of reimbursement, the lowest of which (Category 230) pays €1,229.01 for 250–799 min, and the highest (Category 186) pays €67,531.381 for patients requiring >30,000 min per yearCitation49. Tariffs are presented in . In the second approach, we used standard microcosting methods for services rendered that would be paid by insurers. Prices of these resources were obtained from official lists issued by various governmental agencies in The Netherlands. These prices appear in , which are all expressed in 2016 euros. Estimates of resources costed in previous years were adjusted to 2016 values via the Consumer Price Index for The NetherlandsCitation50.

Table 2. List of DRG codes in The Netherlands used to reimburse treatments for schizophrenia and other major psychoses, time allotments and reimbursement amounts for each DRG category.

Table 3. Costs of resources used in the analysisTable Footnotea.

Utilities were derived from those used in previous researchCitation41, but adjusted using new information. Using a time-trade-off technique, Osborne et al.Citation51 determined patient preferences and associated utilities for receiving injectable drugs having different administration intervals. For stable disease, we subtracted scores between adjacent pairs of administration intervals, using those differences as disutilities. We assumed that PP3M would not incur a disutility. Disutility scores were 0.05 for monthly administration, a further 0.045 for biweekly, and another 0.005 for greater than biweekly. Utility for hospitalization was fixed at 0.490, and no disutilities were applied. To determine the utility for non-hospitalized relapses, we used the mid-point between stable disease and relapse, under the assumption that utilities representing quality-of-life are linear, as has been done by othersCitation52. Utilities are presented in .

Table 4. Utilities used in the research.

The primary analysis was cost-utility, with quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained as the outcome. Secondary analyses involved the determination of cost-effectiveness, with relapse as the clinical outcome. Three separate analyses were performed for different aspects of relapse, including relapses requiring hospitalization, relapses that could be managed as out-patients, and total relapses. The analytic time horizon of 1 year precluded discounting of either costs or outcomes. Economic outcomes were judged against the thresholds authorized by the Dutch health technology assessment agency ZorginstituutCitation53.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the model and its results. In scenario analyses, we varied inputs according to alternate possibilities, including the dose of PP3M, the dose of PP1M, maximizing dropouts, eliminating dropouts, and using alternate utility scores.

We also conducted 1-way sensitivity analyses on all clinical inputs and cost centers. Finally, a probability sensitivity analysis was conducted with 10,000 iterations, varying all inputs within their plausible ranges using standard distributions.

Results

Results of the economic analysis appear in . Expected costs were lower in the PP3M treatment arm in both the DRG or costing analyses. Furthermore, PP3M generated higher QALY values and lower relapse or hospitalization rates. Therefore, PP3M was the dominant treatment option (i.e. both least costly and more effective than comparison).

Table 5. Outcomes from the pharmacoeconomic analysis.

Costs were consistently higher under the costing version, with an average difference of 31.9%. The difference in costs was greatest for PP3M (43% higher) and lowest for haloperidol (22% higher).

For PP3M, the driver of the costs was the acquisition cost of the drug, comprising 48% of the total, with 39% for hospital/institutional care and 13% for medical care. For all of the other drugs assessed, hospitalization was the major driver, amounting to 63%, 69%, 85%, and 92% of the overall treatment for PP1M, HAL-LAT, RIS-LAT, and oral-OLZ, respectively. Drugs ranked second for PP1M, but cost the least for the remaining three drugs.

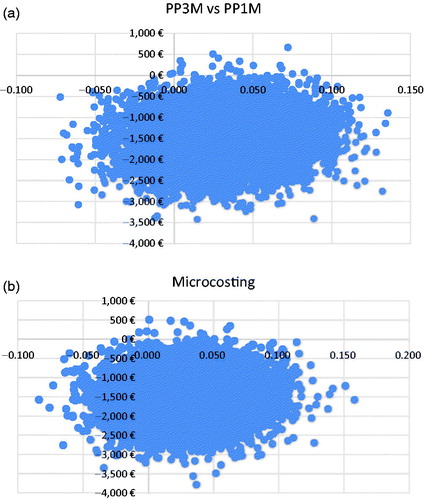

Scenario analyses and 1-way sensitivity analyses resulted in no changes to cost-effectiveness results. In probability sensitivity analyses of the DRG analyses, PP3M remained dominant over all comparison treatments. PP3M had a lower cost than PP1M in 99.8% of the simulations with DRGs; it was dominant in 85.0% and cost-effective in 85.8%. With microcosting, results were very similar. PP3M cost less in 99.9% of the 10,000 simulations; it was dominant in 84.6%, and cost-effective in >99.9%. Scatterplots of PP3M vs PP1M are presented in (DRG analysis) and b (Microcosting analysis). For the other drugs examines, PP3M similarly dominated in very high proportions of the simulations. Scatterplots are presented as in the Appendix.

Discussion

PP3M represents a major advance in the treatment of chronic schizophrenia. In its development, a different particle size was used, but applying the same Nanocrystal technology as was used for PP1M. As a result, the active drug is more slowly released, providing continuous therapeutic levels over at least 3 months, with a half-life of 84–139 daysCitation53–55. Also, if discontinued after having achieved steady state, therapeutic levels remain in the blood for 5–7 monthsCitation54.

These properties generate many clinical advantages. Having a therapeutic blood level over a long period of time provides fewer opportunities for omitting doses, which decreases the probability of relapsing. In a head-to-head trial, Savitz et al.Citation33 did find a lower rate of relapse in patients treated with PP3M. We also found that PP3M was associated with substantially fewer relapses than PP1M.

When comparing the costs from DRGs to those from microcosting, we found a simple average difference of 31.9%, with DRGs being lower. This difference corresponds with the results of Plehn et al.Citation57, who reported a difference of 32.8% for cardiac care. This is somewhat higher than the 23.8% found by Baumgart et al.Citation58 for ulcerative colitis and the 22.6% by Heerey et al.Citation59 in myocardial infarction and HIV cases. Thus, DRGs appear to have under-estimated costs in these papers. Schreyögg et al.Citation60 determined that (because of how they are calculated) DRGs are highly correlated with hospital length of stay, but not resource consumption or case complexity. For this, and other reasons, DRG values vary considerably across nations, and attempts are being made to standardize them for EuropeCitation61.

Four other research projects have reported on the pharmacoeconomics of PP3M, all as posters. Benson et al.Citation62,Citation63 used the RCT of Berwaerts et al.Citation32 to model costs and outcomes between PP3M and placebo over 1 year. All clinical and resource data were gathered during the conduct of that trial. Costs in 2014 USD and outcomes were reported for each phase of the trial. In the open label phase, overall costs were comparable between PP3M and placebo. In the subsequent double-blind phase, costs decreased for PP3M, but increased for placebo. Overall, PP3M dominated placebo due to consuming fewer resources, as a results of lower rates of hospitalization and relapses.

Arteaga Duarte et al.Citation38 used a 5-year Markov model in France to compare PP3M with PP1M. Data were obtained from the RCTs by Savitz et al.Citation33 and Berwaerts et al.Citation32. They found cost savings and increased QALYs with PP3M. De Moor et al.Citation37 also used a 5-year Markov model to examine PP3M and PP1M in Belgium. Data were extracted from the RCTs by Berwaerts et al.Citation32 and Hough et al.Citation64. Results were comparable to those from Arteaga Duarte et al.Citation38. Garcia-Ruiz et al.Citation65 presented an economic analysis comparing PP3M with PP1M based on the 1 year head-to-head randomized controlled trial by Savitz et al.Citation33. PP3M dominated PP1M in both cost-utility and cost-effectiveness analyses. Thus, results were consistent across analyses that used different inputs and different economic models.

Differences between our results and those of Benson et al.Citation62,Citation63 probably arose due to the structure of the models. Those authors modeled the trial by Berwaerts et al.Citation32, whereas we also used data from the Savitz et al.Citation33 trial. In the Benson et al.Citation62,Citation63 analysis, patients who relapsed were censored and resources were not costed after censoring. On the other hand, we costed resource use for all patients over a full year, including those switched to other drugs and those who dropped out. Finally, the Benson calculations did not include drug costs, while the present analysis did, which explains the very large difference in reports costs.

Model validation

We elected to use a decision tree model rather than a Markov for a number of reasons. First, results would likely be quite similar using either modelCitation66. Second, an existing decision tree was available, which required minor modifications to incorporate PP3M into the analysis. Third, the time frame of 1 year matched the duration of the two major trials of PP3MCitation32,Citation33, and was adequate for assessing outcomes of interest.

To validate the outputs of our primary cost-utility model, we compared results with other similar economic analyses with respect to costs and QALYs. Our average cost to manage the psychiatric care of patients for 1 year was 10,793€, which compares favorably with the estimate of van der Lee et al.Citation19 of 10,357€. lists the costs and QALYs from the present studies and validating rates from other independent studies. All rates were quite close, with the exception of oral-OLZ, which had a lower cost in the economic analysis of Druais et al.Citation52.

Table 6. Validation of the cost-utility model.

Limitations

In our analysis, we restricted the time horizon to 1 year, in parallel with the two available clinical trials. It is recognized that this disease persists throughout the life of the patient. However, no long-term data are presently available to extend the analysis with any confidence. Results could change over time.

Another limitation is that some (but not all) of the clinical data were obtained randomized controlled trials, which may not reflect what happens in actual practice. In trials, patients are highly selected and treated according to strict protocols. In “real life”, other influences affected the patients and the care delivered. We did, however, incorporate data from observational studies to account for some of that variance.

We considered only the direct costs of care that would be paid by the Dutch insurer. We did not include indirect costs of care such as decreased employment, and time spent by family or other caregivers.

As well, the analysis was done specifically for The Netherlands, which has a unique method of payment. Therefore, results may not apply to other countries or healthcare systems.

In estimating utilities, we used values obtained from the literature, which represent preferences of the global community, and were not specific to The Netherlands. It is possible that local tariffs could differ.

In addition, as previously mentioned, we excluded costs associated with treating adverse events. A further example was published by another group that examined several long-acting anti-psychotics, including PP1M and RIS-LAT. They found that the cost of treating adverse events ranged from £153–£190, comprising 0.10–0.12% of the total cost of treatment, which ranged from £157,594–£163,359 over 10 yearsCitation52. Considering these results and those mentioned above, it appears that omission of the cost of treating adverse events has little impact on overall results.

Conclusions

In the primary analysis using DRGs, PP3M was cost-effective, dominating all of the other drugs most commonly used for chronic schizophrenia in The Netherlands. Robustness of results was confirmed in both 1-way and probability sensitivity analyses. Findings were similar when we used microcosting.

Much of the clinical advantage for PP3M may be attributed to its very long half-life, which assures a therapeutic blood level for a long period of time. Having a 3-monthly dosing interval reduces resource utilization in an already strained healthcare system. Also, it lowers the probability of failing to adhere to prescribed regimens.

The drug was the cost driver for PP3M; for the rest, hospitalization consumed the major proportion of the costs. The increased drug cost was more than offset by the savings derived for avoiding hospitalization.

A limitation is that many of the data inputs for PP3M were derived from clinical trials, which tend to reflect ideal practice, as opposed to that in the “real world”. Although we did use such data for the other drugs, that information was not yet available for PP3M. Ideally, all results should be verified using observational studies to examine the situation under actual conditions in clinical practice.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was funded by Janssen.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

TE and BB received funding for the research and manuscript. FT, TD, and KVI are employees of Janssen. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

References

- Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Degenhardt L, et al. The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: an analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS One 2015;10:e0116820

- Geohive. http://www.geohive.com/. [Last accessed 16 January 2016]

- Aleman A, Kahn RS, Selten JP. Sex differences in the risk of schizophrenia: evidence from meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:565-71

- de Wit MA, Tuinebreijer WC, van Brussel GH, et al. Ethnic differences in risk of acute compulsory admission in Amsterdam, 1996–2005. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2012;47:111-18

- Maric N, Krabbendam L, Vollebergh W, et al. Sex differences in symptoms of psychosis in a non-selected, general population sample. Schizophr Res 2003;63:89-95

- Bijl RV, van Zessen G, Ravelli A, et al. The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS): objectives and design. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998;33:581-6

- Evers SM, Ament AJ. Costs of schizophrenia in The Netherlands. Schizophr Bull 1995;21:141-53

- Wiersma D, Sytema S, van Busschbach J, et al. Prevalence of long-term mental health care utilization in The Netherlands. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997;96:247-53

- Meesters PD, de Haan L, Comijs HC, et al. Schizophrenia spectrum disorders in later life: prevalence and distribution of age at onset and sex in a Dutch catchment area. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;20:18-28

- van Os J, Driessen G, Gunther N, et al. Neighbourhood variation in incidence of schizophrenia. Evidence for person-environment interaction. Br J Psychiatry 2000;176:243-8

- Haro JM, Altamura C, Corral R, et al. Understanding the impact of persistent symptoms in schizophrenia: Cross-sectional findings from the Pattern study. Schizophr Res 2015;169:234-40

- Lokkerbol J, Adema D, de Graaf R, et al. Non-fatal burden of disease due to mental disorders in the Netherlands. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:1591-9

- Haro JM, Novick D, Perrin E, et al. Symptomatic remission and patient quality of life in an observational study of schizophrenia: is there a relationship? Psychiatry Res 2014;220:163-9

- Tenback D, Pijl B, Smeets H, et al. All-cause mortality and medication risk factors in schizophrenia: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;32:31-5

- Kishi T, Oya K, Iwata N. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for the prevention of relapse in patients with recent-onset psychotic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Res 2016;246:750-5

- Chong HY, Teoh SL, Wu DB, et al. Global economic burden of schizophrenia: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:357-73

- Gupta S, Isherwood G, Jones K, et al. Productivity loss and resource utilization, and associated indirect and direct costs in individuals providing care for adults with schizophrenia in the EU5. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2015;7:593-602

- Csoboth C, Witt EA, Villa KF, et al. The humanistic and economic burden of providing care for a patient with schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2015;61:754-61

- van der Lee A, de Haan L, Beekman A. Schizophrenia in the Netherlands: continuity of care with better quality of care for less medical costs. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157150

- Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:886-91

- Novick D, Haro JM, Suarez D, et al. Predictors and clinical consequences of non-adherence with antipsychotic medication in the outpatient treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2010;176:109-13

- De Hert M, Sermon J, Geerts P, et al. The use of continuous treatment versus placebo or intermittent treatment strategies in stabilized patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with first- and second-generation antipsychotics. CNS Drugs 2015;29:637-58

- Acosta FJ, Bosch E, Sarmiento G, et al. Evaluation of noncompliance in schizophrenia patients using electronic monitoring (MEMS) and its relationship to sociodemographic, clinical and psychopathological variables. Schizophr Res 2009;107:213-17

- Emsley R, Alptekin K, Azorin JM, et al. Nurses’ perceptions of medication adherence in schizophrenia: results of the ADHES cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2015;5:339-50

- Kulkarni J, Reeve-Parker K. Psychiatrists’ awareness of partial- and non-adherence to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: results from the Australian ADHES survey. Australas Psychiatry 2015;23:258-64

- Noordraven EL, Wierdsma AI, Blanken P, et al. Depot-medication compliance for patients with psychotic disorders: the importance of illness insight and treatment motivation. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:269-74

- Kane JM, Sanchez R, Perry PP, et al. Aripiprazole intramuscular depot as maintenance treatment in patients with schizophrenia: a 52-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:617-24

- European Medicines Agency. Xeplion authorization details. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002105/human_med_001424.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d125. [Last accessed 17 March 2016]

- Gaviria AM, Franco JG, Aguado V, et al. A non-interventional naturalistic study of the prescription patterns of antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia from the Spanish province of Tarragona. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139403

- Whale R, Pereira M, Cuthbert S, et al. Effectiveness and predictors of continuation of paliperidone palmitate long-acting injection treatment: a 12-month naturalistic cohort study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2015;35:591-5

- Bernardo M, Bioque M. Three-month paliperidone palmitate - a new treatment option for schizophrenia. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2016;9:899-904

- Berwaerts J, Liu Y, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of the 3-month formulation of paliperidone palmitate vs placebo for relapse prevention of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:830-9

- Savitz AJ, Xu H, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate 3-month formulation for patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, noninferiority study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2016;19

- Ijzerman MJ. Guideline for economic evaluations in healthcare. Amsterdam: Zorginstituut Nederland; June 16, 2016. http://www.ispor.org/PEguidelines/source/Netherlands_Guideline_for_economic_evaluations_in_healthcare.pdf. [Last accessed 10 November 2016]

- Holthausen EA, Wiersma D, Cahn W, et al. Predictive value of cognition for different domains of outcome in recent-onset schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2007;149:71-80

- Bouwmans C, de Sonneville C, Mulder CL, et al. Employment and the associated impact on quality of life in people diagnosed with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2015;11:2125-42

- De Moor R, Malfait B, Tedouri F, et al. Three-monthly long-acting formulation of paliperidone is a dominant treatment option, cost saving while adding QALYs, compared to the one-monthly formulation in the treatment of schizophrenia in Belgium. Poster PMH28 Presented at the ISPOR 19th Annual European Congress, Vienna, Austria, October 29–November 2, 2016. Value Health 2016;19:A526

- Arteaga Duarte C, Guillon P, Fakra E, et al. Three-monthly long-acting formulation of paliperidone palmitate is a dominant treatment option, cost saving while adding QALYs, compared to the one-monthly formulation in the treatment of schizophrenia in France. Poster PRM115. Presented at the ISPOR 19th Annual European Congress, Vienna, Austria, October 29–November 2, 2016. Value Health 2016;19:A378

- Edwards NC, Rupnow MF, Pashos CL, et al. Cost-effectiveness model of long-acting risperidone in schizophrenia in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23:299-314

- Obradovic M, Mrhar A, Kos M. Cost-effectiveness of antipsychotics for outpatients with chronic schizophrenia. Int J Clin Pract 2007;61:1979-88

- Einarson TR, Maia-Lopes S, Goswami P, et al. Economic analysis of paliperidone long-acting injectable for chronic schizophrenia in Portugal. J Med Econ 2016;19:913-21

- Decuypere F, Sermon J, Geerts P, et al. Treatment continuation of four long-acting antipsychotic medications in the Netherlands and Belgium: A retrospective database study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179049

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The NICE guidelines on core interventions in the treatment and management of schizophrenia in adults in primary and secondary care. London: NICE; 2010

- Olivares J, Rodrigues-Morales A, Diels J, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with schizophrenia treated with risperidone long-acting injection or oral antipsychotics in Spain: Results from the electronic Schizophrenia Treatment Adherence Registry (e-STAR). Eur Psychiatry 2009;24:287-96

- Kim E, Berwaerts J, Turkoz I, et al. Time to schizophrenia relapse in relapse-prevention studies of antipsychotics developed for administration daily, once monthly, and every 3 months. Presented at the 15th International Congress on Schizophrenia Research, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, March 28–April 1, 2015

- Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, et al. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:683-91

- Niaz OS, Haddad PM. Thirty-five months experience of risperidone long-acting injection in a UK psychiatric service including a mirror-image analysis of in-patient care. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007;116:36-46

- Spill B, Konoppa S, Kissling W, et al. Long-term observation of patients successfully switched to risperidone long-acting injectable: A retrospective, naturalistic 18-month mirror-image study of hospitalization rates and therapy costs. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2010;14:53-62

- DBC tarivien 2016 – Universitair Centrum Psychiatrie. https://www.umcg.nl/SiteCollectionDocuments/UMCG/Afdelingen/Psychiatrie/DBC%20tarieven%202016%20-%20Universitair%20Centrum%20Psychiatrie%20%20(UCP).pdf. Accessed March 19, 2016

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Consumer Price Index http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?Dataset-Code=MEI_PRICES. [Last accessed 19 March 2016]

- Osborne RH, Dalton A, Hertel J, et al. Health-related quality of life advantage of long-acting injectable antipsychotic treatment for schizophrenia: a time trade-off study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:35

- Druais S, Doutriaux A, Cognet M, et al. Cost effectiveness of paliperidone long-acting injectable versus other antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in France. Pharmacoeconomics 2016;34:363-91

- Zorginstituut. https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/binaries/content/documents/zinl-www/documenten/publicaties/rapporten-en-standpunten/2015/1506-kosteneffectiviteit-in-de-praktijk/Kosteneffectiviteit+in+de+praktijk.pdf. [Last accessed 16 January 2017]

- Ravenstijn P, Remmerie B, Savitz A, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of paliperidone palmitate 3-month formulation in patients with schizophrenia: A phase-1, single-dose, randomized, open-label study. J Clin Pharmacol 2016;56:330-9

- Leng D, Chen H, Li G, et al. Development and comparison of intramuscularly long-acting paliperidone palmitate nanosuspensions with different particle size. Int J Pharm 2014;472:380-5

- Park EJ, Amatya S, Kim MS, et al. Long-acting injectable formulations of antipsychotic drugs for the treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Pharm Res 2013;36:651-9

- Plehn G, Oernek A, Vormbrock J, et al. [Comparison of costs and revenues in conservative and invasive treatment in cardiology: a contribution margin analysis]. Gesundheitswesen 2015;15. [Epub ahead of print] German

- Baumgart DC, le Claire M. The expenditures for academic inpatient care of inflammatory bowel disease patients are almost double compared with average academic gastroenterology and hepatology cases and not fully recovered by diagnosis-related group (DRG) proceeds. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147364

- Heerey A, McGowan B, Ryan M, et al. Microcosting versus DRGs in the provision of cost estimates for use in pharmacoeconomic evaluation. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2002;2:29-33

- Schreyögg J, Tiemann O, Busse R. Cost accounting to determine prices: how well do prices reflect costs in the German DRG-system? Health Care Manag Sci 2006;9:269-79

- Geissler A, Quentin W, Busse R. Heterogeneity of European DRG systems and potentials for a common EuroDRG system: comment on “Cholecystectomy and Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs): patient classification and hospital reimbursement in 11 European countries”. Int J Health Policy Manag 2015;4:319-20

- Benson C, Chirila C, Graham J, et al. Health resource use and cost analysis of schizophrenia patients participating in a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, relapse-prevention study of paliperidone palmitate 3-month formulation. Presented at the ISPOR 20th Annual International Meeting; Philadelphia, PA, May 16–20, 2015

- Benson C, Chirila C, Graham J, et al. Health resource use and cost analysis of schizophrenia patients participating in a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, relapse-prevention study of paliperidone palmitate 3-month formulation. Abstract PMH27. Value Health 205;18:A119

- Hough D, Gopal S, Vijapurkar U. Paliperidone palmitate maintenance treatment in delaying the time-to-relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res 2010;116:107-17

- García-Ruiz AJ, Pérez-Costillas L, Montesinos AC, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of antipsychotics in reducing schizophrenia relapses. Health Econ Rev 2012;2:8

- Einarson TR, Hemels ME. Validation of an economic model of paliperidone palmitate for chronic schizophrenia. J Med Econ 2013;16:1267-74

- European Medicines Agency. Trevicta authorization details. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/004066/human_med_001829.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac0580-01d124. [Last accessed 16 November 2016]

- Baser O, Xie L, Pesa J, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs of Veterans Health Administration patients with schizophrenia treated with paliperidone palmitate long-acting injection or oral atypical antipsychotics. J Med Econ 2015;18:357-65

- Taylor D, Olofinjana O. Long-acting paliperidone palmitate - interim results of an observational study of its effect on hospitalization. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2014;29:229-34

- Attard A, Olofinjana O, Cornelius V, et al. Paliperidone palmitate long-acting injection—prospective year-long follow-up of use in clinical practice. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014;130:46-51

- Zhang F, Si T, Chiou CF, et al. Efficacy, safety, and impact on hospitalizations of paliperidone palmitate in recent-onset schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2015;11:657-68

- Liu HL, Liu Y, Hao ZX, et al. Comparison of primary coronary percutaneous coronary intervention between diabetic men and women with acute myocardial infarction. Pakistan J Med Sci 2015;31:420-5

- Alphs L, Benson C, Cheshire-Kinney K, et al. Real-world outcomes of paliperidone palmitate compared to daily oral antipsychotic therapy in schizophrenia: a randomized, open-label, review board-blinded 15-month study. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:554-61

- Fu DJ, Turkoz I, Simonson RB, et al. Paliperidone palmitate once-monthly reduces risk of relapse of psychotic, depressive, and manic symptoms and maintains functioning in a double-blind, randomized study of schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:253-62

- McEvoy JP, Byerly M, Hamer RM, et al. Effectiveness of paliperidone palmitate vs haloperidol decanoate for maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;311:1978-87

- Bitter I, Katona L, Zámbori J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of depot and oral second generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a nationwide study in Hungary. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2013;23:1383-90

- Chan HW, Huang CY, Feng WJ, et al. Risperidone long-acting injection and 1-year rehospitalization rate of schizophrenia patients: A retrospective cohort study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2015;69:497-503

- Chang HC, Tang CH, Huang ST, et al. A cost-consequence analysis of long-acting injectable risperidone in schizophrenia: a one-year mirror-image study with national claim-based database in Taiwan. J Psychiatr Res 2012;46:751-6

- Chue P, Llorca P-M, Duchesne I, et al. Hospitalization rates in patients during long-term treatment with long-acting risperidone injection. J Appl Res 2005;5:266-74

- Deslandes PN, Thomas A, Faulconbridge GM, et al. Experience with risperidone long-acting injection: results of a naturalistic observation study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2007;11:207-11

- Huang SS, Lin CH, Loh E-W, et al. Antipsychotic formulation and one-year rehospitalization of schizophrenia patients: a population-based cohort study. Psychiatr Serv 2013;64:1259-62

- Koczerginski D, Arshoff L. Hospital resource use by patients with schizophrenia: reduction after conversion from oral treatment to risperidone long-acting injection. Healthc Q 2011;14:82-7

- Lammers L, Zehm B, Williams R. Risperidone long-acting injection in Schizophrenia Spectrum Illnesses compared to first generation depot antipsychotics in an outpatient setting in Canada. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:155

- Leal A, Rosillon D, Mehnert A, et al. Healthcare resource utilization during 1-year treatment with long-acting, injectable risperidone. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2004;13:811-16

- Llorca PM, Sacchetti E, Lloyd K, et al. Long-term remission in schizophrenia and related psychoses with long-acting risperidone: results obtained in an open-label study with an observation period of 18 months. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008;46:14-22

- Lloyd K, Latif MA, Simpson S, et al. Switching stable patients with schizophrenia from depot and oral antipsychotics to long-acting injectable risperidone: efficacy, quality of life and functional outcome. Hum Psychopharmacol 2010;25:243-52

- Mihaljevic-Peles A, Sagud M, Filipcic IS, et al. Remission and employment status in schizophrenia and other psychoses: one-year prospective study in Croatian patients treated with risperidone long acting injection. Psychiatr Danub 2016;28:263-72

- Olivares JM, Peuskens J, Pecenak J, et al. Clinical and resource-use outcomes of risperidone long-acting injection in recent and long-term diagnosed schizophrenia patients: results from a multinational electronic registry. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2197-206

- Ren XS, Crivera C, Sikirica M, et al. Evaluation of health services use following the initiation of risperidone long-acting therapy among schizophrenia patients in the veterans health administration J Clin Pharm Ther 2011;36:383-9

- Rossi A, Bagalà A, Del Curatolo V, et al. Risperidone long-acting trial investigators (R-LAI). Remission in schizophrenia: one-year Italian prospective study of risperidone long-acting injectable (RLAI) in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Hum Psychopharmacol 2009;24:574-83

- Taylor M, Currie A, Lloyd K, et al. Impact of risperidone long acting injection on resource utilization in psychiatric secondary care. J Psychopharmacol 2008;22:128-31

- Williams R, Chandrasena R, Beauclair L, et al. Risperidone long-acting injection in the treatment of schizophrenia: 24-month results from the electronic Schizophrenia Treatment Adherence Registry in Canada. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2014;10:417-25

- Yu HY, Hsiao CY, Chen KC, et al. A comparison of the effectiveness of risperidone, haloperidol and flupentixol long-acting injections in patients with schizophrenia—A nationwide study. Schizophr Res 2015;169:400-5

- European Medicines Agency. Risperdal Consta® summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Referrals_document/Risperdal_Consta_30/WC500008170.pdf. [Last accessed 2 March 2017]

- Conley RR, Kelly DL, Love RC, et al. Rehospitalization risk with second-generation and depot antipsychotics. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2003;15:23-31

- Shi L, Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, et al. Characteristics and use patterns of patients taking first-generation depot antipsychotics or oral antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2007;58:482-8

- Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries DE, et al. Medication adherence levels and differential use of mental-health services in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC Res Notes 2009;2:6

- Patel NC, Dorson PG, Edwards N, et al. One-year rehospitalization rates of patients discharged on atypical versus conventional antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv 2002;53:891-3

- Vanasse A, Blais L, Courteau J, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia treatment: a real-world observational study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2016;134:374-84

- Williams R, Kopala L, Malla A, et al. Medication decisions and clinical outcomes in the Canadian National Outcomes Measurement Study in Schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2006;430:12-21

- Yu AP, Atanasov P, Ben-Hamadi R, et al. Resource utilization and costs of schizophrenia patients treated with olanzapine versus quetiapine in a Medicaid population. Value Health 2009;12:708-15

- Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209-23

- Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, et al. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT). Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:82-91

- Dossenbach M, Arango-Dávila C, Silva Ibarra H, et al. Response and relapse in patients with schizophrenia treated with olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, or haloperidol: 12-month follow-up of the Intercontinental Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes (IC-SOHO) study. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:1021-30

- García-Cabeza I, Gómez JC, Sacristán JA, et al. Subjective response to antipsychotic treatment and compliance in schizophrenia. A naturalistic study comparing olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol (EFESO Study). BMC Psychiatry 2001;1:7

- Gibson PJ, Damler R, Jackson EA, et al. The impact of olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol on the cost of schizophrenia care in a medicaid population. Value Health 2004;7:22-35

- Gómez JC, Sacristán JA, Hernández J, et al. The safety of olanzapine compared with other antipsychotic drugs: results of an observational prospective study in patients with schizophrenia (EFESO study). Pharmacoepidemiologic study of olanzapine in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61:335-43

- Kasper S, Rosillon D, Duchesne I, et al. Risperidone olanzapine drug outcomes studies in schizophrenia (RODOS): efficacy and tolerability results of an international naturalistic study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;16:179-87

- Kilian R, Steinert T, Schepp W, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic maintenance therapy with quetiapine in comparison with risperidone and olanzapine in routine schizophrenia treatment: results of a prospective observational trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2012;262:589-98

- Kraemer S, Chartier F, Augendre-Ferrante B, et al. Effectiveness of two formulations of oral olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in a natural setting: results from a 1-year European observational study. Hum Psychopharmacol 2012;27:284-94

- Kumar V, Rao NP, Narasimha V, et al. Antipsychotic dose in maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a retrospective study. Psychiatry Res 2016;245:311-31

- Mladsi DM, Grogg AL, Irish WD, et al. Pharmacy cost evaluation of risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine for the treatment of schizophrenia in acute care inpatient settings. Curr Med Res Opin 2004;20:1883-93

- Rascati KL, Johnsrud MT, Crismon ML, et al. Olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a comparison of costs among Texas Medicaid recipients. Pharmacoeconomics 2003;21:683-97

- Sacristán JA, Gómez JC, Montejo AL, et al. Doses of olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol used in clinical practice: results of a prospective pharmacoepidemiologic study. EFESO Study Group. Estudio Farmacoepidemiologico en la Esquizofrenia con Olanzapina. Clin Ther 2000;22:583-99

- Snaterse M, Welch R. A retrospective, naturalistic review comparing clinical outcomes of in-hospital treatment with risperidone and olanzapine. Clin Drug Invest 2000;20:159-64

- Takahashi M, Nakahara N, Fujikoshi S, et al. Remission, response, and relapse rates in patients with acute schizophrenia treated with olanzapine monotherapy or other atypical antipsychotic monotherapy: 12-month prospective observational study. Pragmat Obs Res 2015;6:39-46

- Tiihonen J, Wahlbeck K, Lönnqvist J, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of patients in community care after first hospitalisation due to schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: observational follow-up study. BMJ 2006;333:224

- Buchanan RW, Breier A, Kirkpatrick B, et al. Positive and negative symptom response to clozapine in schizophrenic patients with and without the deficit syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:751-60

- Essock SM, Hargreaves WA, Dohm FA, et al. Clozapine eligibility among state hospital patients. Schizophr Bull 1996;22:15-25

- Kane JM, Marder SR, Schooler NR, et al. Clozapine and haloperidol in moderately refractory schizophrenia: a 6-month randomized and double-blind comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:965-72

- Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, et al. A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Clozapine in Refractory Schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 1997;337:809-15

- Bondolfi G, Dufour H, Patris M, et al. Risperidone versus clozapine in treatment-resistant chronic schizophrenia: a randomized double-blind study. The Risperidone Study Group. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:499-504

- Breier A, Hamilton SH. Comparative efficacy of olanzapine and haloperidol for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1999;45:403-11

- Henderson DC, Nasrallah RA, Goff DC. Switching from clozapine to olanzapine in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: safety, clinical efficacy, and predictors of response. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59:585-98

- Hong CJ, Chen JY, Chiu HJ, et al. A double-blind comparative study of clozapine versus chlorpromazine on Chinese patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997;12:123-30

- Josiassen RC, Joseph A, Kohegyi E, et al. Clozapine augmented with risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162

- Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988;45:789-96

- Klieser E, Lehmann E, Kinzler E, et al. Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of risperidone versus clozapine in patients with chronic schizophrenia J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995;15(1Suppl1):45S-51S

- Krakowski MI, Czobor P, Citrome L, et al. Atypical antipsychotic agents in the treatment of violent patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:622-9

- Kumra S, Kranzler H, Gerbino-Rosen G, et al. Clozapine and “high-dose” olanzapine in refractory early-onset schizophrenia: a 12-week randomized and double-blind comparison. Biol Psychiatry 2008;63:524-9

- McGurk SR, Carter C, Goldman R, et al. The effects of clozapine and risperidone on spatial working memory in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1013-16

- Moresco RM, Cavallaro R, Messa C, et al. Cerebral D2 and 5-HT2 receptor occupancy in schizophrenic patients treated with olanzapine or clozapine. J Psychopharmacol 2004;18:355-6

- Naber D, Riedel M, Klimke A, et al. Randomized double blind comparison of olanzapine vs. clozapine on subjective well-being and clinical outcome in patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;111:106-15

- Sacchetti E, Galluzzo A, Valsecchi P, et al. Ziprasidone vs clozapine in schizophrenia patients refractory to multiple antipsychotic treatments: the MOZART study. Schizophr Res 2009;113:112-21

- Tollefson GD, Birkett MA, Kiesler GM, et al. Double-blind comparison of olanzapine versus clozapine in schizophrenic patients clinically eligible for treatment with clozapine. Biol Psychiatry 2001;49:52-63

- Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, et al. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:255-62

- Wahlbeck K, Cheine M, Tuisku K, et al. Risperidone versus clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a randomized pilot study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2000;24:911-22

- European Medicine Agency. Committee for Proprietary Medical Products (CPMP) summary information on referral opinion following arbitration pursuant to Article 30 of Council Directive 2001/83/EC for Leponex and associated names. November 12, 2002. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Referrals_document/Leponex_30/WC500010966.pdf. [Last accessed November 19, 2016]

- Chen EY, Hui CL, Lam MM, et al. Maintenance treatment with quetiapine versus discontinuation after one year of treatment in patients with remitted first episode psychosis: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;341:c4024

- Crow TJ, MacMillan JF, Johnson AL, et al. A randomised controlled trial of prophylactic neuroleptic treatment. Br J Psychiatry 1986;148:120-7

- Hogarty GE, Goldberg SC. Drug and sociotherapy in the aftercare of schizophrenic patients. One-year relapse rates. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1973;28:54-64

- Hogarty GE, Ulrich RF. The limitations of antipsychotic medication on schizophrenia relapse and adjustment and the contributions of psychosocial treatment. J Psychiatr Res 1998;32:243-50

- Kane JM, Rifkin A, Quitkin F, et al. Fluphenazine vs placebo in patients with remitted, acute first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982;39:70-3

- McCreadie RG, Wiles D, Grant S, et al. The Scottish first episode schizophrenia study. VII. Two-year follow-up. Scottish Schizophrenia Research Group. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989;80:597-602

- McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, et al. Randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:790-9

- Eklund K, Forsman A. Minimal effective dose and relapse–double-blind trial: haloperidol decanoate vs. placebo. Clin Neuropharmacol 1991;14(Suppl2):S7-S12

- Sectorrapport GGZ. Amersfoort, The Netherlands: GGZ Nederland, December 2015. http://www.ggznederland.nl/uploads/assets/GGZ1508-01%20Sectorrapport-2013-1.pdf. [Last accessed 10 January 2017]

- ZIN Kostenhandleiding. Methodologie van kostenonderzoek en referentieprijzen voor economische evaluaties. Rotterdam: Erasmus University Institute for Medical Technology Assessment; 2014. https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/binaries/content/documents/zinl-www/documenten/publicaties/overige-publicaties/1602-richtlijn-voor-het-uitvoeren-van-economische-evaluaties-in-de-gezondheidszorg-bijlagen/1602-richtlijn-voor-het-uitvoeren-van-economische-evaluaties-in-de-gezondheidszorg-bijlagen/Richtlijn+voor+het+uitvoeren+van+economische+evaluaties+in+de+gezondheidszorg+(verdiepingsmodules).pdf. [Last accessed 19 November 2016]

- NZA Tariefbeschikking gespecialiseerde geestelijke gezondheidsorg. TB/CU-5079. Utrecht: Nederlandse Zorgautoriteit; 2016. https://www.nza.nl/1048076/1048144/TB_CU_5079_01__Gespecialiseerde_geestelijke_gezondheidszorg.pdf. [Last accessed 19 November 2016]

- SHL Tariffs: laboratory diagnostics. Etten-Leur, The Netherlands: SHL Group. https://www.shl-groep.nl/patient/tarieven/?tariefgroep=laboratoriumdiagnostiek. [Last accessed 18 November 2016]

- Dilla T, Ciudad A, Alvarez M. Systematic review of the economic aspects of nonadherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with schizophrenia. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013;7:275-84