Abstract

Aims: To compare healthcare costs and resource utilization in patients with overactive bladder (OAB) in the US who switch from mirabegron to onabotulinumtoxinA (onabotA) with those who persist on mirabegron.

Materials and methods: A retrospective observational claims analysis of the OptumHealth Administrative Claims database conducted between April 1, 2012 and September 30, 2015 used medical and pharmacy claims to identify patients with at least one OAB diagnosis who switched from mirabegron to onabotA (onabotA group) or persisted on mirabegron for at least 180 days (mirabegron persisters). Propensity score weighting was used to balance baseline characteristics that were associated with increased healthcare expenditures across treatment groups. Multivariate analyses assessed the impact of switching and persistence on all-cause and OAB-related healthcare costs and resource utilization in the year following each patient’s index date.

Results: In total, 449 patients were included in this study: 54 patients were included in the onabotA group, and 395 patients were included in the mirabegron persister group. Compared with the mirabegron persister patients, the onabotA patients observed significantly higher OAB-related total costs ($5,504 vs $1,772, p < .001), OAB-related medical costs ($5,033 vs $351, p < .001), sacral neuromodulation costs ($865 vs $60, p = .017), and outpatient costs ($17,385 vs $9,035, p = .009), and more OAB-related medical visits (6.0 vs 1.9, p < .001). OnabotA patients had lower OAB-related prescription costs ($470 vs $1,421, p < .001) and fewer OAB-related pharmacy claims (1.6 vs 5.0, p <.001). There were no significant differences in all-cause total medical or prescription costs.

Limitations: This study was a retrospective analysis using claims data that only included patients with commercial health coverage or Medicare supplemental coverage. Accuracy of the diagnosis codes and the generalizability of the results to other OAB populations are limited. The study was not designed to determine the impact of OAB treatments on the economic outcomes examined.

Conclusions: OAB patients who persisted on mirabegron treatment for at least 180 days had lower OAB-related healthcare costs and resource utilization compared with those who switched to onabotA.

Background

Overactive bladder (OAB) is defined by the International Continence Society as the presence of “urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency or nocturia, with or without urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), in the absence of urinary tract infection (UTI) or other obvious pathology”Citation1 (p. 7). In the US, 35.6% of adults aged ≥40 years are affected by OAB symptoms, at least “sometimes”Citation2. OAB prevalence increases with ageCitation2, and the proportion of Americans aged >65 years is predicted to rise from 13.7% in 2012 to 20.3% in 2030Citation3. Therefore, the number of individuals suffering from OAB in the US is expected to increase. Estimated total costs of OAB were $65.9 billion in 2007, and total national costs are projected to reach $82.6 billion in 2020Citation4.

The American Urology Association and Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine & Urogenital Reconstruction (AUA/SUFU) guidelines propose a step-wise algorithmic approach to OAB treatment. Behavioral therapy, including fluid management, bladder training, pelvic floor muscle exercises, and bladder control strategies (i.e. pre-emptive or prompted voiding), is first-line treatment for OAB. For patients whose treatment goals are not reached with behavioral therapy alone, second-line treatment includes pharmacological agents such as oral anti-muscarinics or oral β3-adrenoceptor agonists. Patients who experience inadequate symptom control and/or an unacceptable adverse drug event profile with one of these pharmacological agents are switched to another. Patients who are refractory to first- and second-line OAB treatments may be offered intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA (onabotA; 100 U), peripheral tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS), or sacral neuromodulation (SNM) as third-line treatmentsCitation5,Citation6.

Anti-muscarinics have been a mainstay second-line treatment for the symptoms of OAB since the introduction of oxybutynin more than 30 years agoCitation7,Citation8. However, retrospective analyses of medical claims data show discontinuation rates for anti-muscarinics range from 43–83% within the first 30 daysCitation7, Mirabegron is the first β3-adrenoceptor agonist approved for the treatment of OAB symptoms. As an alternative second-line OAB treatmentCitation6, mirabegron has similar efficacy to the anti-muscarinics, but a lower incidence of adverse drug eventsCitation6,Citation9. Compared with anti-muscarinics, patients persist on mirabegron therapy longer and are more compliantCitation10–12, and mirabegron has been associated with reduced healthcare resource utilizationCitation12.

Clinicians may offer third-line OAB treatments in any order; however, AUA/SUFU treatment guidelines recently upgraded onabotA treatment from an option to a standard third-line treatment in carefully selected patients with moderate-to-severe OAB symptomsCitation6. In women with refractory OAB (moderate-to-severe baseline levels of UUI, incontinence, frequency and urgency), onabotA 100IU resulted in significant improvements in measured voiding outcomes (UUI, incontinence, frequency, urgency, nocturia, pad use) and quality-of-life outcomes compared to placeboCitation6,Citation13–15. PTNS and SNM remain as recommendations for third-line treatment, based on low quality evidenceCitation6.

To the authors’ knowledge, there are no real-world studies evaluating the impact of switching from second-line to third-line OAB treatment on healthcare costs and resource utilization. As patients on mirabegron have improved persistence compared with anti-muscarinicsCitation10–12, and onabotA is the only standard third-line OAB treatmentCitation6, this study aimed to measure the impact of persistence with mirabegron usage or switching to onabotA on healthcare costs and resource utilization. The objective of the study was to compare healthcare costs and resource utilization in patients who switch from mirabegron to onabotA with those who persist on mirabegron. Persisting with mirabegron as second-line OAB treatment may reduce onabotA usage, as well as medical and adverse event costs.

Methods

Study design

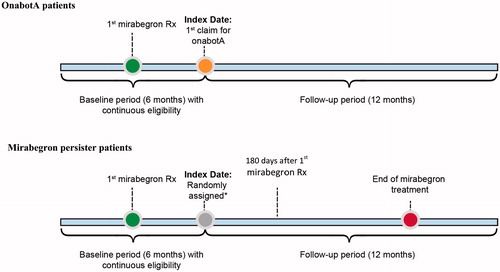

This retrospective, longitudinal analysis used healthcare claims data extracted from the OptumHealth Administrative Claims database between April 1, 2012 and September 30, 2015. The OptumHealth Administrative Claims database includes medical and pharmacy claims that capture participants’ inpatient and outpatient medical and pharmacy encounters for individuals with commercial or Medicare supplemental health insurance coverage. The OptumHealth administrative claims database covers over 120 million commercial lives in the US and is one of the largest and most complete claims databases in the US. The database provides longitudinal information on prescription drug and medical resource use starting January 1, 2010. Medical claims include diagnosis and procedure codes, as well as information on place of service that can be used to determine emergency visits or inpatient stays. Pharmacy records include details on prescription fills, such as drug code and days supply. The OptumHealth medical and pharmacy claims contain standardized prices that reflect allowed payments for all provider services on each claim, accounting for differences across health plans and provider contracts. Furthermore, patient demographic information is available, such as year of birth, sex, and geographic region. Importantly, enrollment files are also available to identify periods of continuous eligibility for each patient. The study compared healthcare costs and resource utilization in two groups of patients with at least one OAB diagnosis. The onabotA patients switched from mirabegron to onabotA and were defined as patients with at least one prescription for onabotA after receiving mirabegron; the index date was assigned as the first date of the onabotA claim. The mirabegron persister patients received a continuous supply of mirabegron for at least 180 days without greater than a 30-day gap in supplyCitation12. The index date for mirabegron persister patients was randomly assigned based on the distribution of time between the first mirabegron prescription and the date of the first onabotA claim for the onabotA patients. To allow for adequate opportunity to observe switching and multiple injections with onabotA, all patients were followed for 12 months immediately after their index date, which was directly preceded by a 6-month baseline period of continuous eligibility ().

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Individuals who were at least 18 years of age were eligible for this study. Inclusion criteria were: (1) at least one medical claim with an OAB diagnosis, as identified by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes listed in ; (2) at least one prescription claim for mirabegron after an OAB diagnosis; (3) at least 6 months of continuous insurance eligibility prior to and 12 months following the patient’s index date; and (4) either switched to onabotA or persisted on mirabegron treatment for 180 days. Exclusion criteria were: (1) pregnancy during the baseline period; (2) benign prostatic hyperplasia during the baseline period; (3) stress incontinence during the baseline period; or (4) urinary tract infection during the 14 days prior to or following the index date.

Table 1. Medical codes.

Healthcare costs and resource utilization

Medical and pharmacy claims were used to estimate all-cause and OAB-related healthcare costs and resource utilization associated with switching from mirabegron to onabotA or persisting on mirabegron in the year following each patient’s index date (). All-cause healthcare costs were defined as standardized costs, as calculated by OptumHealth, inflated to 2015 USD, associated with all medical and pharmacy claims. OAB-related healthcare costs were defined as standardized costs inflated to 2015 USD associated with medical claims with an OAB ICD-9-CM code, OAB-related medical visits for onabotA, OAB-related medical visits for PTNS and SNM, and pharmacy claims for mirabegron and anti-muscarinics. All-cause healthcare resource utilization was defined as the sum of all medical visits and pharmacy claims. OAB-related healthcare resource utilization was defined as the total count of medical visits with an OAB ICD-9-CM code, medical visits for onabotA, medical visits for PTNS and SNM, and pharmacy claims for mirabegron and anti-muscarinics. Inpatient stays, outpatient claims, and emergency room (ER) claims were identified using the point of service, or “POS”, field in the Optum database. Inpatient costs, outpatient costs, and ER costs were defined as the standardized costs inflated to 2015 USD associated with inpatient stays, outpatient claims, and ER claims.

Statistical analyses

Patient baseline characteristics included demographic variables, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) Enhanced ICD-9-CM Version, and Elixhauser Comorbidity Measure, indicators for each Charlson comorbidity, indicators for OAB-associated conditions, and measures of all-cause and OAB-related healthcare costs and resource utilization in the baseline period. Categorical variables were summarized as the number and percentage of patients in each category.

Continuous variables were summarized as means, medians, and standard deviations. Differences in the distributions of categorical variables were assessed using Chi-square tests; differences in the distributions of continuous variables were assessed using two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

A two-stage statistical model estimation process was used to assess the impact of switching and persistence on all-cause and OAB-related healthcare costs and resource utilization, while accounting for potential confounding from patient baseline characteristics.

In the first stage, propensity score weights were calculated from a logistic regression. The dependent variable was a binary indicator for whether a patient was in the onabotA group.

Covariates included patients’ age, gender, geographical region, insurance product type, common OAB-related comorbidities, and Elixhauser comorbidities. Predicted probabilities from the logistic regression were transformed into “average treatment effect on the treated” (ATT) weights.

Second-stage regressions (one for each endpoint) were estimated using all-cause and OAB-related healthcare costs and resource utilization as the dependent variables, a treatment group indicator as the independent variable, and propensity score weighting to balance baseline characteristics between the two patient groups. Generalized linear models (GLM) with log links were used to model continuous outcome variables. The distribution of the dependent variable in the GLM was determined using a Modified Park Test. If the dependent variable had more than 75% of the observations equal to zero, then a two-part model was used, where the first part estimated the probability of having a non-zero value using a probit regression, and the second part estimated the size of outcome using a GLM, conditional on having a non-zero value. Negative binomial regression models were used for discrete count outcome variables. For all regressions, results were transformed to average marginal effects on the original scale of the dependent variable (e.g, dollars) to ease interpretation.

All analyses were conducted using SAS Studio software (version 3.5, basic edition, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata software (version 14.2, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Because the data were de-identified, this study did not involve Human Subjects Research.

Results

Study population

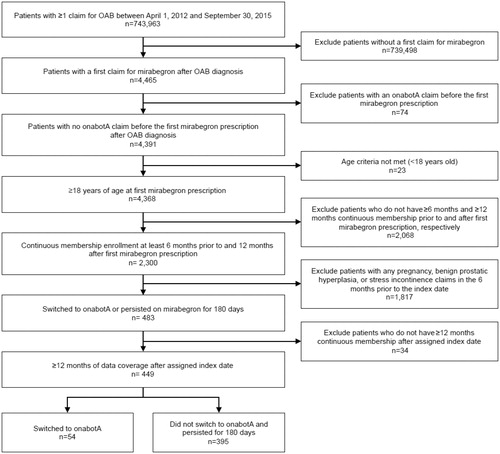

A total of 4,391 patients ≥18 years of age with at least one claim for mirabegron following an OAB diagnosis were eligible for inclusion in this study. Of these, 449 patients met all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria (). Fifty-four patients were grouped into the cohort that switched to onabotA (onabotA group), and 395 patients were grouped into the cohort that persisted with mirabegron (mirabegron persister group).

Patients’ unadjusted baseline characteristics are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Compared with the mirabegron persister patients, the onabotA patients were significantly younger (58.5 vs 64.3 years, p = .0099), contained fewer males (9.3% vs 22.5%, p = .0245), and had a higher number of OAB-related medical claims (3.2 vs 1.5, p < .0001), fewer mirabegron claims (2.0 vs 2.7, p = .0053), higher OAB-related medical costs ($984 vs $400, p < .0001), and lower OAB-related pharmacy costs ($670 vs $948, p = .0003).

Differences in the baseline characteristics between the patients in the two groups were controlled for using propensity score weights. Male patients were less likely (odds ratio [OR] = 0.302, p = .027) to switch to onabotA (Supplementary Figure S1).

After applying the propensity score weights, baseline characteristics, including age (onabotA, 58.5 vs mirabegron persisters, 58.5 years, standard difference [SD] = 0.003), all-cause total healthcare costs (onabotA, $14,356 vs mirabegron persisters, $12,640 [SD = 0.098]), all-cause medical costs (onabotA, $9,150 vs mirabegron persisters, $8,419 [SD = 0.047]), OABrelated total healthcare costs (onabotA, $1,655 vs mirabegron persisters, $1,657 [SD <0.001]), and OAB-related medical costs (onabotA, $984 vs mirabegron persisters, $742 [SD = 0.071]) were similar for patients in the onabotA and mirabegron persister groups ().

Table 2. Adjusted baseline characteristics.

Healthcare costs and resource utilization

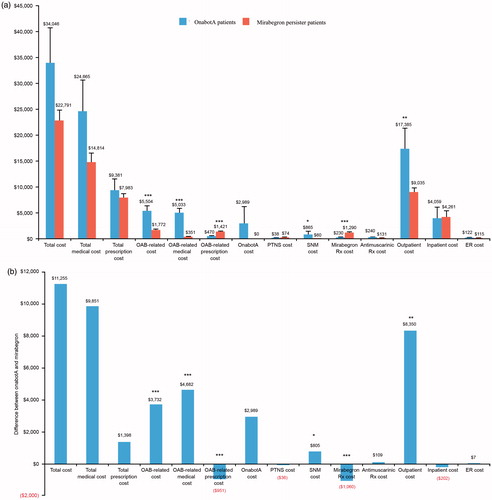

Compared with the mirabegron persister patients, at 12 months post-index, the onabotA patients had significantly higher OAB-related total costs ($5,504 vs $1,772, p < .001) and OAB-related medical costs ($5,033 vs $351, p < .001) and lower OAB-related prescription costs ($470 vs $1,421, p < .001). Additionally, the onabotA patients had significantly more OAB-related medical visits (6.0 vs 1.9, p < .001) and fewer OAB-related pharmacy claims (1.6 vs 5.0, p < .001). OnabotA patients had numerically but not statistically higher all-cause total costs ($34,046 vs $22,791; p = .061). There were no significant differences in all-cause total medical or prescription costs (; ).

Figure 3. (a) Comparison of and (b) difference in healthcare costs between patients switched to onabotA and those who persisted on mirabegron treatment. All healthcare costs are inflated to 2015 dollars. The first group includes patients who switched to onabotA after receiving mirabegron. The second group includes patients who persisted on mirabegron treatment and never switched to onabotA in the study period. The index date for patients in the onabotA group is the date of the patient’s first onabotA injection. The index date for patients in the second group is randomly assigned based on the distribution of the time between the first mirabegron prescription and the first onabotA injection for patients in the first group. Values are estimates and standard errors; *p = .017; **p = .009; ***p < .001. ER, emergency room; OAB, overactive bladder; OnabotA, onabotulinumtoxinA; PTNS, peripheral tibial nerve stimulation; Rx, prescription; SNM, sacral neuromodulation.

Table 3. Healthcare resource utilization.

Compared with the mirabegron persister patients, at 12 months post-index, the onabotA patients had significantly higher SNM costs ($865 vs $60, p = .017) and outpatient costs ($17,385 vs $9,035, p = .009). As expected, the onabotA patients had $2,989 in onabotA costs (vs $0 for the mirabegron persister patients) and lower mirabegron prescription costs ($230 vs $1,290, p < .001). There were no significant differences in anti-muscarinic, PTNS, inpatient, or ER costs (; ).

Discussion

This retrospective study compared all-cause and OAB-related healthcare costs and resource utilization in patients who switched to onabotA with those who persisted with mirabegron for at least 180 days. Findings showed that OAB patients who continued mirabegron treatment had lower total OAB-related costs, OAB-related medical costs, SNM costs, outpatient costs, and OAB-related medical visits compared with those who switched to onabotA. Patients who switched to onabotA had lower OAB-related prescription costs and OAB-related pharmacy claims. These data suggest that switching to onabotA after mirabegron use leads to increased OAB-related healthcare costs and resource utilization, an increase that may be offset, to some extent, by lower prescription costs and pharmacy claims in onabotA-treated patients.

To the authors’ knowledge, no previous studies have investigated the economic impact of switching from mirabegron as second-line OAB treatment to onabotA. AUA/SUFU guidelines include mirabegron as second-line treatment for OAB, stating that mirabegron has similar efficacy and lower rates of adverse drug effects than anti-muscarinicsCitation6. OnabotA is recommended as a standard third-line treatment in carefully selected patients with refractory OAB, usually defined as those who are intolerant of medical therapy or have failed medical therapyCitation14. Existing evidence supporting the effectiveness of mirabegron as an alternative second-line OAB treatment and findings from the current study suggest that patients who persist with mirabegron have lower OAB-related healthcare costs and resource utilization compared with those who switch to onabotA. A retrospective analysis of claims records demonstrated that median persistence was significantly longer for mirabegron (90 days) than tolterodine (30 days), and mirabegron was associated with a reduction in unique number of prescription medications, resource utilization, and overall costs compared with tolterodineCitation12. Taken together, these findings indicate that management of OAB with mirabegron, rather than standard anti-muscarinic therapies, could be considered before switching to third-line OAB treatments, such as onabotA. As clinical trials with mirabegron demonstrate that maximal response is achieved at 12 weeksCitation6,Citation16–19, physicians should recommend patients persist with mirabegron for at least 12 weeks.

Costs associated with onabotA treatment for OAB include the need to perform the procedure in an inpatient or outpatient setting under local anesthetic, the requirement for an urodynamic examination before the procedure, and the need for prophylactic antibiotics prior to the day of treatment and for 1–3 days post-treatment. Follow-up in clinical practice usually involves assessment of a post-void residue at 2 weeks, and regular patient/urologist communication about outcomesCitation20. Urinary retention, often requiring catheterization, and UTI are the most common adverse events associated with onabotA injectionsCitation14,Citation20, incurring additional costs. The therapeutic duration of an onabotA injection ranges from 6.3–10.6 months, and repeat injections may be needed at an inter-injection interval ranging from 12 weeks to 1.5 yearsCitation14. Some patients may continue to use anti-muscarinic therapy, while others may discontinue onabotA injections due to lack of efficacy or issues with tolerabilityCitation14.

Cost-effectiveness analyses indicate that onabotA is cost-effective compared with anti-muscarinics for refractory UUICitation21 or PTNS and SNS for OABCitation22 in the US, and onabotA plus best supportive care (BSC; defined as a combination of incontinence pads, alone or with catheterization, and/or antimuscarinic therapy) is a cost-effective therapy vs BSC for OAB in some countries in EuropeCitation23. Mirabegron was shown to be a cost-effective alternative to anti-muscarinics for OAB from US commercial health plan and Medicare Advantage perspectives, in part because mirabegron has a better persistence profile compared with anti-muscarinicsCitation24.

The current study has several limitations. First, it is associated with limitations inherent to any retrospective analysis using claims data, which include lack of clinical information, reasons for switching, and information on behavioral therapies, which might affect study outcomes. Second, the study only included patients with commercial health coverage or Medicare supplemental coverage. Although the study was able to identify a relatively large and racially diverse population of patients, the results may not be generalizable to patients with other types of insurance or without health insurance coverage. Third, there is the possibility that key outcomes, exposures, and control variables were influenced by errors in the administrative claims data. For example, claims data indicate receipt of a medication, but they do not identify if the patient used the medication as prescribed. Also, the identification of OAB and comorbidities will rely on diagnosis codes, which are subject to potential miscoding. Last, the results do not reflect the causal impact of mirabegron treatment on outcomes, to the extent that important confounding variables were not accounted for. However, the patients in the two groups were similar in terms of demographics and baseline healthcare costs, as propensity score weights were applied to control for baseline characteristics

Conclusions

This study found that OAB patients who persisted on mirabegron treatment for >180 days had similar all-cause total medical and prescription costs, but lower OAB-related healthcare costs and resource utilization relative to those who switched to onabotA.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funding for this study was provided by Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc.

Declaration of financial/other interests

D. B. Ng, D. Walker, and K. Gooch are employees of Astellas. R. Espinosa and S. J. Johnson received funding from Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc for this study. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the medical writing support of Jane Kondejewski, PhD, SNELL Medical Communication, Inc., which was funded by Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc.

References

- Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn 2010;29:4-20

- Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Vats V, et al. National community prevalence of overactive bladder in the United States stratified by sex and age. Urology 2011;77:1081-7

- Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. Washington (DC): US Census Bureau 2014:2-6

- Ganz ML, Smalarz AM, Krupski TL, et al. Economic costs of overactive bladder in the United States. Urology 2010;75:526-32

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol 2012;188(6Suppl):2455-63

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Faraday M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment. J Urol 2015;193:1572-80

- Kim TH, Lee KS. Persistence and compliance with medication management in the treatment of overactive bladder. ICUrology 2016;57:84-93

- Kenelley MJ. A comparative review of oxybutynin chloride formulation: pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy in overactive bladder. Rev Urol 2010;12:12-19

- Maman K, Aballea S, Nazir, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of medical treatments for the management of overactive bladder: a systematic literature review and mixed treatment comparison. Eur Urol 2014;65:755-65

- Pindoria N, Malde S, Nowers J, et al. Persistence with mirabegron therapy for overactive bladder: A real life experience. Neurourology and urodynamics 2017;36:404-8

- Wagg A, Franks B, Ramos B, et al. Persistence and adherence with the new beta-3 receptor agonist, mirabegron, versus antimuscarinics in overactive bladder: early experience in Canada. Can Urol Assoc J 2015;9:343-50

- Nitti VW, Rovner ES, Franks B, et al. Persistence with mirabegron versus tolterodine in patients with overactive bladder. Am J Pharm Benefits 2016;8:e25-e33

- Nitti VW, Dmochowski R, Herschorn S, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of patients with overactive bladder and urinary incontinence: results of a phase 3, randomized, placebo controlled trial. J Urol 2013;189:2186-93

- Cox L, Cameron AP. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of overactive bladder. Res Rep Urol 2014;6:79-89

- Ramos HL, Castellanos LT, Esparza IP, et al. Management of overactive bladder with onabotulinumtoxinA: systematic review and meta-analysis. Urology 2017;100:53-8

- Mirabegron prescribing information. Astellas Pharma, Inc. Revised June 2012

- Khullar V, Amarenco G, Angulo JC, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of mirabegron, a β3 adrenoceptor agonist, in patients with overactive bladder: results from a randomised European-Australian phase 3 trial. Eur Urol 2013;63:283-95

- Nitti VW, Auerbach S, Martin N, et al. Results of a randomized phase III trial of mirabegron in patients with overactive bladder. J Urol 2013;189:1388-95

- Herschorn S, Barkin J, Castro-Diaz D, et al. A phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, multicentre study to assess the efficacy and safety of the β3 adrenoceptor agonist, mirabegron, in patients with symptoms of overactive bladder. Urology 2013;82:313-20

- Karsenty G, Baverstock R, Carlson K, et al. Technical aspects of botulinum toxin type A injection in the bladder to treat urinary incontinence: reviewing the procedure. Int J Clin Pract 2014;68:731-42

- Wu JM, Siddiqui NY, Amundsen CL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of botulinum toxin A versus anticholinergic medications for idiopathic urge incontinence. J Urol 2009;181:2181-6

- Hepp Z, Yehoshua A, Gultyaev D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA versus PTNS and SNS for the treatment of overactive bladder from the US payer perspective. Value Health 2016;19:PUK11

- Ruff L, Bagshaw E, Aracil J, et al. Economic impact of onabotulinumtoxinA for overactive bladder with urinary incontinence in Europe. J Med Econ 2016;19:1107-15

- Wielage RC, Perk S, Campbell NL, et al. Mirabegron for the treatment of overactive bladder: cost-effectiveness from US commercial health-plan and Medicare Advantage perspectives. J Med Econ 2016;19:1135-43